The alarm over suicides of military veterans has been regularly sounded over the past 15 years, prompting the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to declare that “preventing suicide among Veterans is the VA’s top clinical priority.” The VA’s 2019 report on suicide provides reason to sound the alarm again, for it tells of a suicide rate that has continued to climb, particularly for younger veterans who have served since 9/11.

Indeed, a close review of VA data provides reason to conclude that the rise in suicide is being driven, at least in part, by the VA’s suicide prevention efforts. Its screening protocols have ushered an ever greater number of veterans into psychiatric care, where treatment with antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs is regularly prescribed. Suicide rates have increased in lockstep with the increased exposure among veterans to such medications.

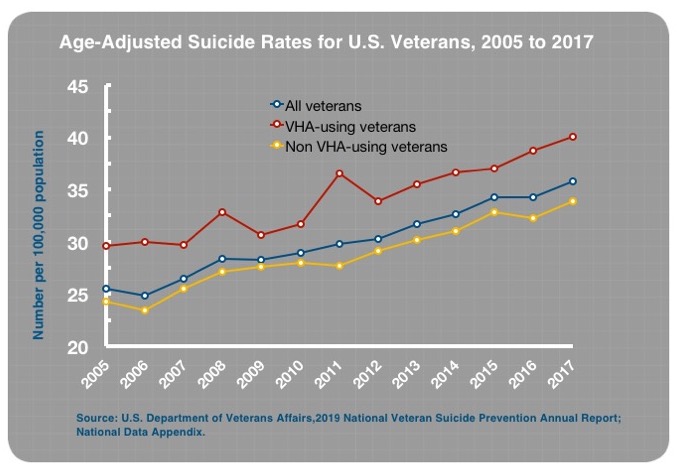

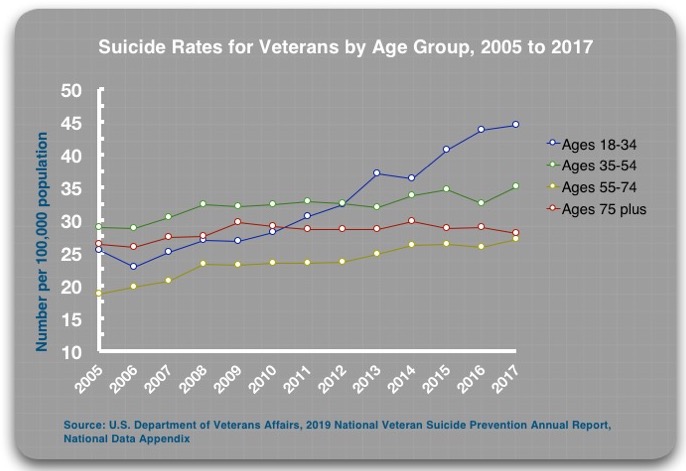

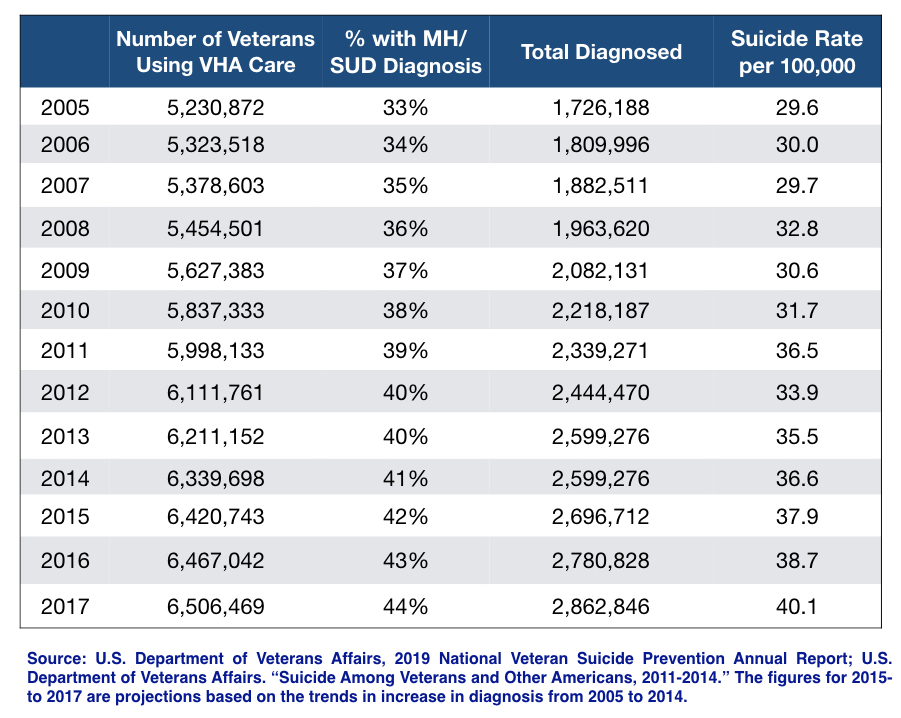

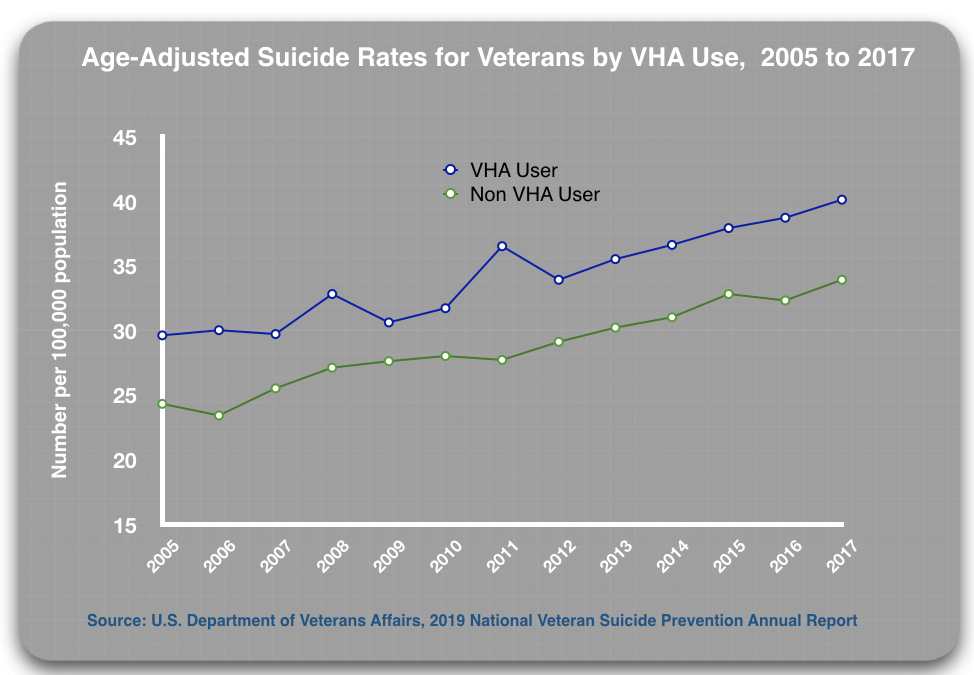

According to the 2019 report, the age-adjusted suicide rates for all veterans rose from 25.5 per 100,000 population in 2005 to 35.8 per 100,000 in 2015, a 40% increase.1 The rate for veterans using Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities rose from 29.6 per 100,000 in 2005 to 40.1 in 2017, a 35% increase.

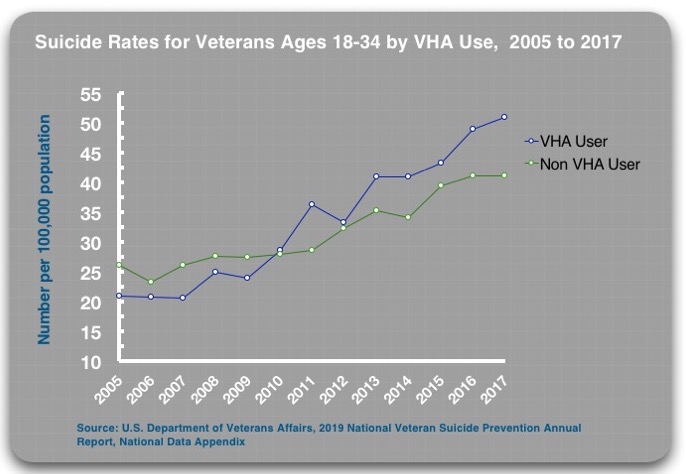

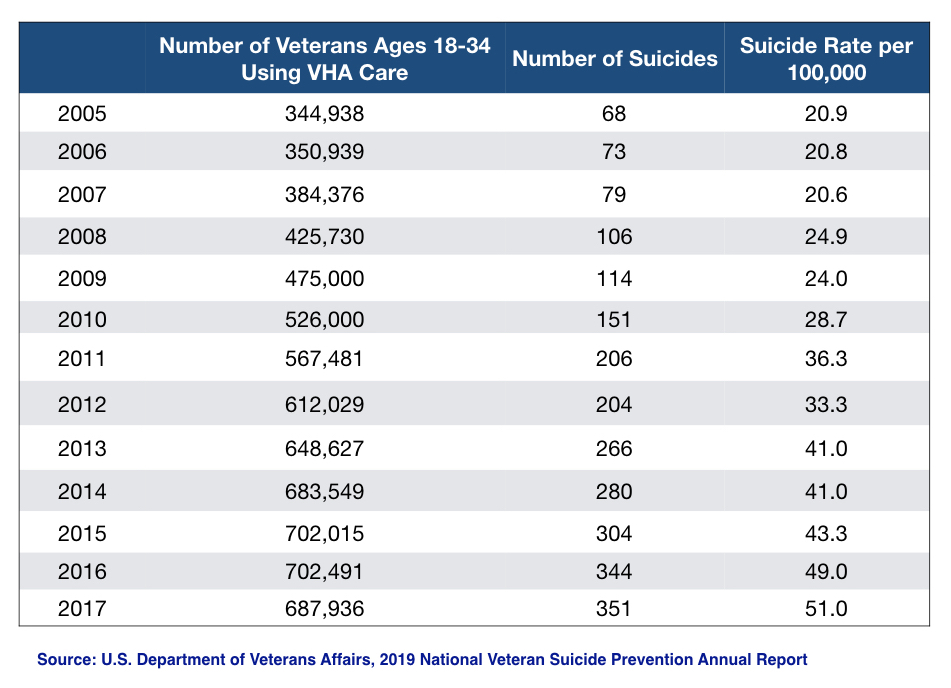

The increase in suicide was even more pronounced for veterans 18 to 34 years old. The suicide rate for this group increased from 25.3 per 100,000 in 2005 to 44 per 100,000 in 2017, a 74% increase. For this age group using VHA facilities, the suicide rate rose from 20.9 per 100,000 in 2005 to 51 per 100,000 in 2017, a 144% increase.

In a previous MIA Report, we made the case that “suicide prevention efforts,” which are based on the premise that suicide is a “public health” problem that can best be addressed by getting more people diagnosed and into treatment, have fueled a steady rise in suicide rates in the United States since 2000. An investigation into the rise in suicide among veterans can be seen as a “replication” study. In the VA’s data, is it possible to identify the same treatment-related forces at work?

There is, buried in the VA’s 2016 suicide report, data on the suicide rates for treated and untreated patients that make this a question of particular urgency.

Suicide in the Civilian Population

The initiation of suicide prevention efforts in the United States began in the late 1980s, shortly after Prozac—the first “selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor” antidepressant—came to market. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention was established then, and although it promoted a “public health” message, it was a non-profit that was funded, to a significant extent, by pharmaceutical companies, which understood that a “suicide prevention” campaign would boost sales of their drugs. Academic psychiatrists with financial ties to the makers of antidepressants led its scientific advisory board and served terms as directors of the foundation.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention promoted a very simple message to the American public. Suicide was said to be a “public health” problem that was “under-recognized.” Many people with mood disorders went “untreated” and this was the population at particularly high risk of suicide. People who were feeling depressed or suicidal were urged to seek help from mental health professionals. The Foundation pushed screening programs as a way to get more people into treatment. Its advisory board and presidents touted antidepressants as “anti-suicide” pills.

“Use of antidepressants to treat major depressive episode is the single most effective suicide prevention measure in Western Countries,” said Columbia University psychiatrist John Mann, who had long been a fixture on the Foundation’s scientific advisory board, and served for a time as its president.

The American Psychiatric Association, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and the pharmaceutical companies that sold antidepressants all helped promote this message to the public. In 1997, their efforts prompted both houses of Congress to declare suicide a “national problem.” Two years later, U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher issued a “Call to Action to Prevent Suicide,” and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services formed a task force, composed of individuals and organizations from the private and public sectors, to develop a “National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.” The task force published its recommendations in 2001, which doubled-down on the “public health” approach that had been promoted by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Government agencies at all levels—federal, state, and local—launched suicide prevention efforts. Crisis call centers were established; depression screening programs were initiated; checklists for assessing the risk of suicide in depressed patients were developed; and medical professionals were trained to recognize the “warning signs” of suicide. The goal was to get more people struggling with mood disorders into treatment, with antidepressants recommended as a first-line therapy.

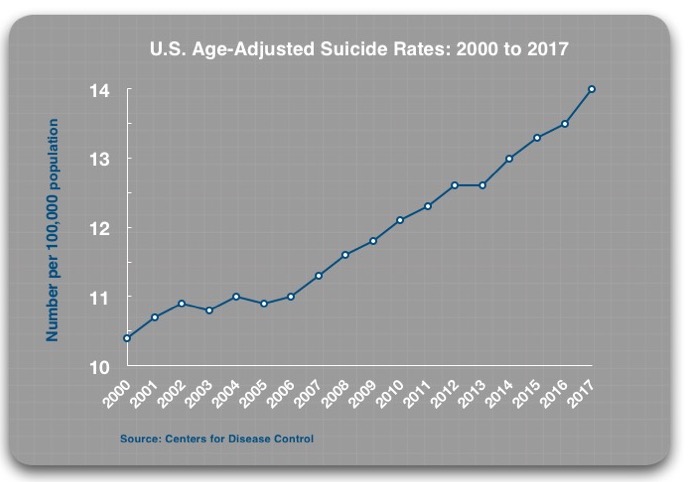

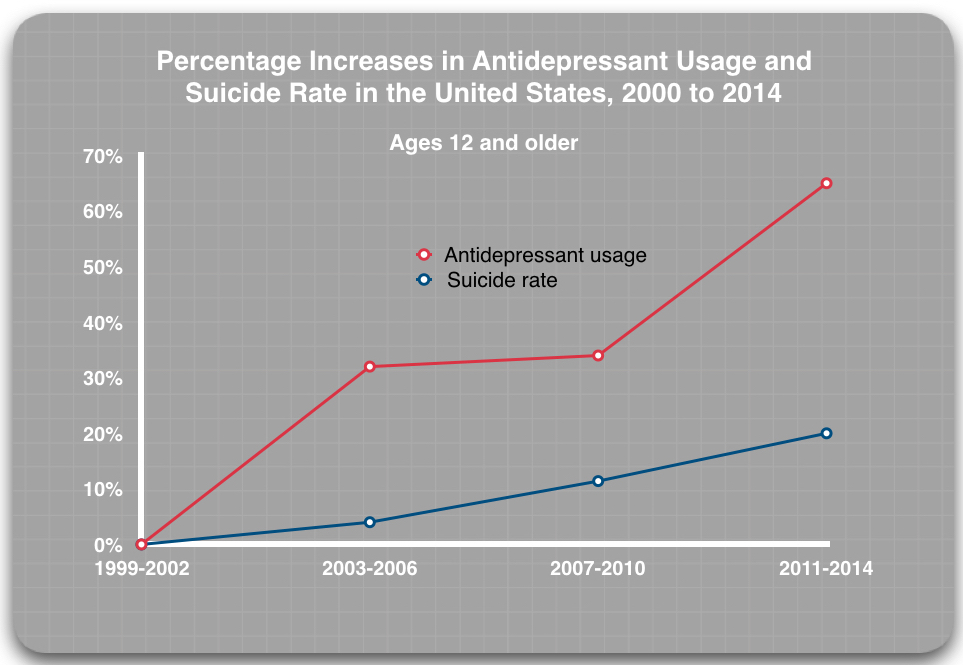

These efforts have been successful in that regard: the prescribing of antidepressants has increased steadily since 2000. Yet, since 2000, the age-adjusted suicide rate for the American population, rather than decrease, has risen steadily, from 10.4 per 100,000 to 14.0 per 100,000 in 2017.

The failure of this approach to suicide prevention, which emphasizes getting people into treatment, is not a uniquely American phenomenon. In the 1990s, the World Health Organization urged countries around the world to develop national mental health policies and to improve their mental health services, which included providing their citizens with better access to psychiatric medications. The belief was that this would lead to better mental health outcomes, which would become visible in the form of reduced suicide rates.

Researchers from the UK, Denmark and Australia have now conducted three studies of whether such efforts have affected suicide rates, and all came to the same conclusion: improved access to psychiatric services and psychiatric drugs was associated with an increase in national suicide rates.

In a similar vein, a large Danish study of suicides in Denmark from 1996 to 2009 came to the disturbing conclusion that the risk of suicide escalated dramatically upon entry into psychiatric care. They found that, in comparison to a matched control group who hadn’t had any involvement with psychiatric care during the previous year, the risk of suicide was:

- 5.8 times higher for people receiving psychiatric medication (but no other care)

- 8.2 times higher for people having outpatient contact with a mental health professional

- 27.9 times higher for people having contact with a psychiatric emergency room

- 44.3 times higher for people admitted to a psychiatric hospital

Although it could be expected that the suicide risk would increase for each step up the “treatment” ladder, what surprised the researchers was that it occurred even in those who were married, and in those with higher incomes or higher levels of education and no prior history of attempted suicide.

In an accompanying editorial, two Australian experts in suicide research wrote that the findings “raise the disturbing possibility that psychiatric care might, at least in part, cause suicide.”

The Impact of Antidepressants

Although the promoters of suicide prevention programs have touted antidepressants as a treatment that reduces the risk of suicide, evidence that the drugs might have the opposite effect arose in the first clinical trials of Prozac. A significant percentage of patients given Prozac suddenly developed suicidal thoughts, and after Prozac came to market, there were numerous case reports of patients prescribed the drug committing suicide. By the early 1990s, with Paxil and other SSRIs entering the marketplace, the FDA was forced to convene a public hearing on this concern.

The controversy has circulated within research circles—and in the public mind—ever since.

There is clear evidence that SSRIs and SNRI antidepressants can provoke suicidal impulses and acts in some users, and the reason is well known. SSRIs and other antidepressants can stir extreme restlessness, agitation, insomnia, severe anxiety, mania and psychotic episodes. The agitation and anxiety, which is clinically described as akathisia, may reach “unbearable” levels, and akathisia is known to be associated with suicide and acts of violence, including homicide.

At the same time, there are many people who tell of how SSRIs or some other antidepressant saved their lives, as their suicidal impulses waned after going on the drugs. Individual responses to antidepressants may vary greatly, and so the public health question is about the net effect of these drugs on suicide rates. On the whole, do they increase or decrease the risk of suicide in people so treated?

There are several types of studies that provide an “evidence base” for answering that question.

Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs)

RCTs are seen as the “gold standard” for assessing the merits of a drug treatment, at least over the short term, as the trials typically last only six weeks or so. Thus, the trials might be expected to identify whether SSRI and SNRI antidepressants trigger any increase in suicidal behavior when patients are first put on the medication.

The FDA, in its review of industry-funded RCTs of SSRIs and other antidepressants, concluded that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking for those under 25 years old; have a neutral effect on those 25 to 64 years old; and are protective against suicidal thinking for those over 64.

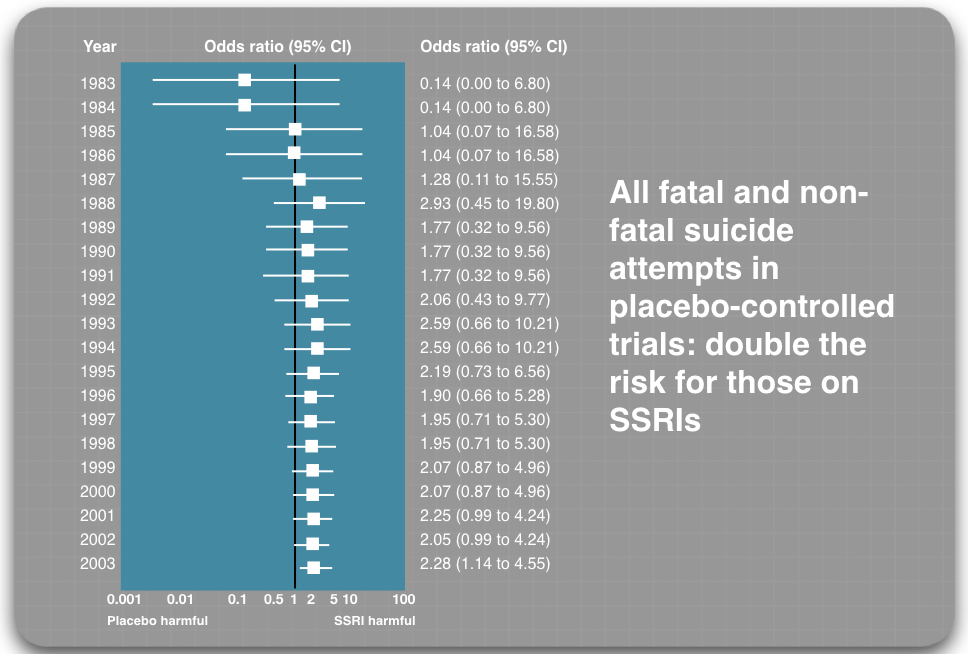

However, it is well known that the pharmaceutical companies sought to downplay—or hide—suicidal risks in the trial reports they sent to the FDA. In 2003, UK psychiatrist David Healy and a team of Canadian researchers conducted an exhaustive meta-analysis of all RCTs of SSRIs, which incorporated findings from trials that weren’t funded by pharmaceutical companies, and they found that suicide attempts were 2.28 times higher for those treated with an SSRI compared to placebo.

Two recent analyses of clinical trial data have led to similar findings. First, after reviewing 64,381 pages of clinical study reports filed with the European Medicines Agency, Peter Gøtzsche and colleagues concluded that antidepressants doubled the risk that patients would experience akathisia, a known risk factor for suicide.

Second, European researchers Michael Hengartner and Martin Plöderl conducted an exhaustive review of the trial data submitted to the FDA for all antidepressants approved from 1991 to 2013, a database that numbered more than 40,000 patients, and they determined that suicide attempts were 2.5 times higher for those taking antidepressants compared to placebo.

Observational Studies in Primary-Care Patients

During the past 25 years, there have been hundreds of studies of different types—observational studies, epidemiological studies, and so forth—that have sought to assess whether antidepressants are protective against suicide, or conversely increase suicide rates. Those studies have produced a welter of conflicting findings. However, the studies that are of most relevance to suicide prevention efforts are those that look at patients diagnosed with depression in a primary care setting, and then chart suicide rates for those who take an antidepressant and those who avoid doing so.

That initial choice serves as a fork-in-the road moment, the patients heading down either a medicated path or a non-medicated one. There are at least three studies that provide a comparison of suicide rates for these two paths following a diagnosis of depression in primary care.

- In a 1998 study of 35,436 people in the Puget Sound area of Washington, the risk of suicide was 43 per 100,000 person years for those treated with an antidepressant in primary care, compared to zero per 100,000 person years for those treated in primary care without antidepressants.

- In a 2003 analysis of UK patients treated in primary care for depression (or for other “affective disorder”), Healy and Chris Whitaker concluded that the suicide rate for those taking an SSRI was 3.4 times greater than for those who chose “non-treatment.”

- In a study of 238,963 UK patients who experienced a first episode of depression between 2000 and 2011, researchers reported that there was an increased risk of suicide for those treated with SSRI antidepressants during the first month of treatment, and again in the first month after quitting the drug.

This last study reveals why observational studies that simply assess medication use at the time of a suicide may present skewed results. The high-risk period that occurs when someone is withdrawing from an SSRI antidepressant is a risk that comes from going on the drug in the first place, yet, in most observational studies, the suicide is chalked up to the “off medication” column.

There are other classes of drugs that may contribute to an increased suicide risk, most notably benzodiazepines. Polypharmacy does so as well. The focus on antidepressants is because this class of drugs is regularly touted, in suicide prevention programs, as protective against suicide.

Suicide Prevention at the VA

The VA launched a focused suicide prevention effort in 2006, when it appointed a National Suicide Prevention Coordinator. The following year it established a toll-free Veterans Crisis line, and since then it has steadily increased the resources devoted to this effort. One such effort was its Make the Connection campaign, which spent nearly $20 million to market the VHA’s services to veterans.

Like the federal government, the VA conceives of “suicide” as a “public health” problem, and thus its bottom-line goal is to increase the identification of mental health problems in the veteran community, and get those who are given a mental health diagnosis into treatment, which is expected to reduce the suicide risk.

About two-thirds of the 20 million veterans in the United States do not use Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities, and the VA, since it launched its toll-free crisis line in 2007, has regularly conducted mental health awareness campaigns to encourage veterans who are not users of VHA care to seek medical help for such problems. In 2018, it partnered with a pharmaceutical company, Johnson & Johnson, to promote a No Veteran Left Behind campaign, which featured Tom Hanks and urged “each and very American” to reach out to veterans in crisis and help get them “mental health services.” The communications plan, the VA stated, was “led by Johnson & Johnson.”

Within its own VHA facilities, the VA has introduced mandatory screening for all vets. Every vet entering the system is screened for depression, PTSD, and substance abuse, and all those who are diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder are assessed for “suicidal intent.” Such screening continues to be a regular feature of VHA care, as screening of some type is part of every patient appointment. Every vet is screened annually for depression, and all of those diagnosed with PTSD upon entry into VHA care are rescreened for this disorder for the next five years.

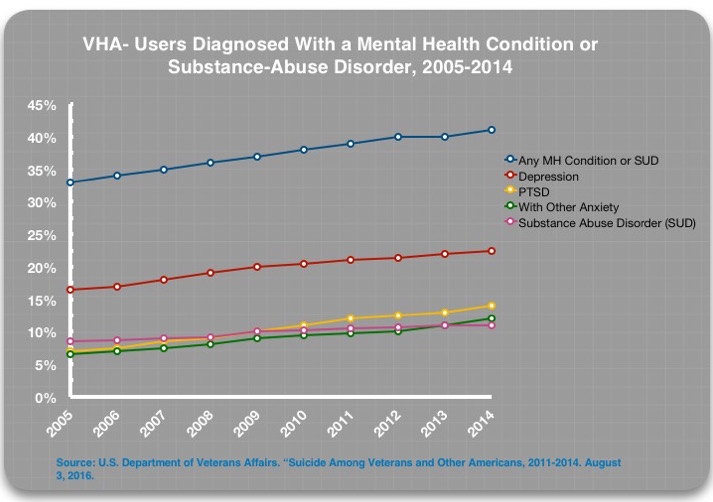

With this regular screening in place, the percentage of VHA patients with a mental health diagnosis has increased steadily. In 2014, 41% of VHA-using veterans had a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis (SUD), with depression the most common diagnosis.2 Although the VA’s most recent suicide reports haven’t detailed this diagnostic information, it can be safely assumed that this steady increase in diagnosis has continued, and that perhaps 44% of VHA-using veterans had a mental health/SUD diagnosis in 2017.

Treatment in the VA

The VA’s clinical care guidelines for treating depression and PTSD, which are the two most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders, recommend SSRI and SNRI antidepressants as first-line therapies. However, the guidelines also provide recommendations for CBT and other psychotherapies, and particularly in primary care settings, these treatments may be offered as stand-alone therapies.

Even so, the prescribing of antidepressants to those diagnosed with depression or PTSD is routine. According to a 2015 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), 94% of all VHA patients diagnosed with depression from 2009 to 2013 were prescribed an antidepressant. Studies of VHA patients diagnosed with PTSD have reported that about 80% are prescribed a psychiatric medication, with antidepressants the drug class of choice.

A 2019 GAO report that sampled prescribing practices at a small number of VHA facilities found that only 15% of diagnosed patients were offered psychotherapy in lieu of drug treatment. Forty-four percent were offered a combination of both, and the remaining 41% drug treatment only.3

Polypharmacy is also common in VA settings, particularly since half of those diagnosed are said to be co-morbid for two or more mental disorders. The 2019 GAO report found that among those diagnosed with depression who were treated in “primary care and specialty mental health care” settings, 35% percent were taking two classes of psychiatric drugs, and 15% three classes of drugs. The polypharmacy was even more pronounced for those diagnosed with PTSD: 36% were taking two classes of psychiatric drugs and 25% were taking three or more classes.4

Suicide Rates For VHA Patients

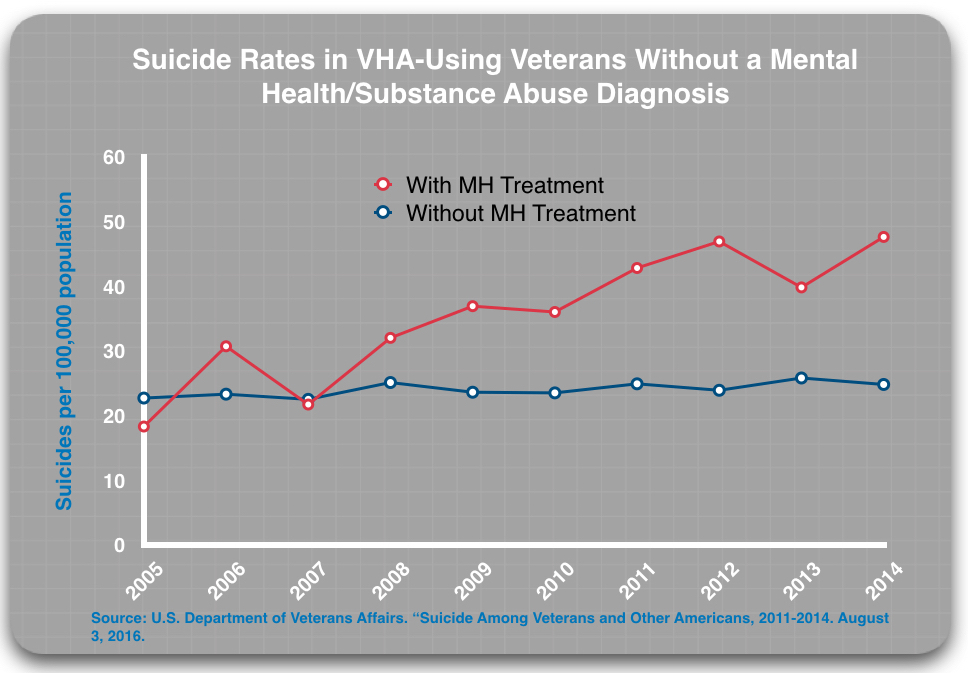

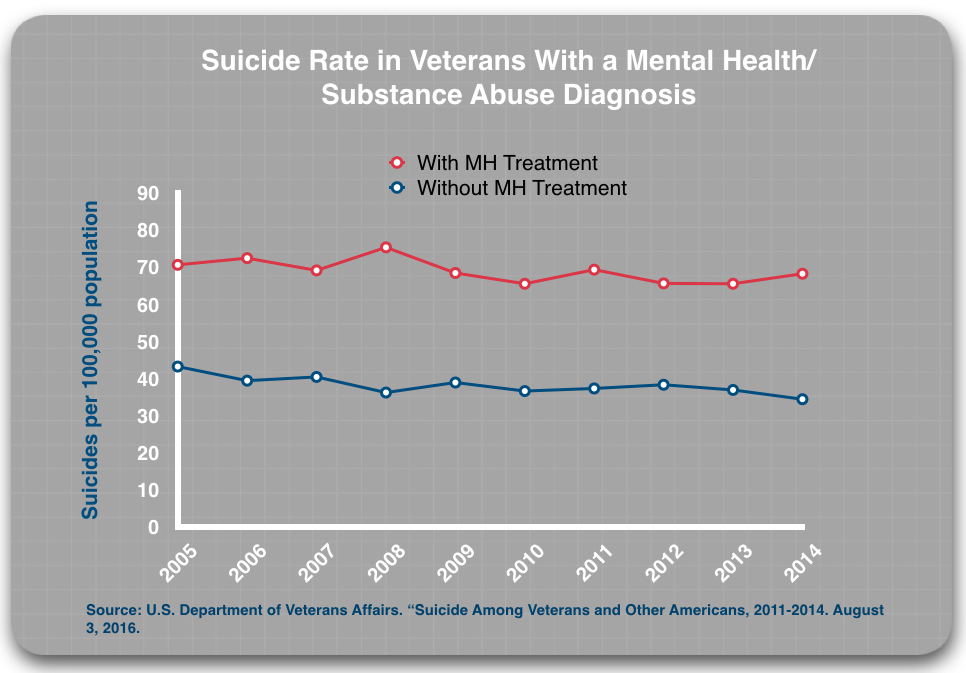

As noted above, the suicide rate among veterans has been steadily rising since 2005. The VA, in a 2016 report, divided the VHA-using patients into four subgroups:5

- Undiagnosed and untreated (for a mental health or substance abuse disorder)

- Undiagnosed and treated (with either a psychiatric drug or non-pharmacologic treatment)

- Diagnosed and untreated

- Diagnosed and treated

If antidepressants are effective in reducing suicide risk, it is easy to see how the suicide rate for the four groups should stack up.

Given that the VHA regularly screens for mental health disorders, the “undiagnosed” patients apparently do not show the symptoms of depression, PTSD or any other psychiatric disorder that, during the screening process, would generate a diagnosis. These patients should be at a low risk of suicide, and thus any treatment to patients in this “undiagnosed” category should—at least in theory—further reduce this risk since it is being prescribed as a balm for whatever ailment is bothering the patients. As such, the undiagnosed/treated patients could be expected to have a lower suicide rate than the undiagnosed/untreated group.

The “diagnosed” patients should be at a higher risk of suicide. Suicide prevention efforts focus on getting these patients into treatment, with antidepressants seen as a first-line therapy than can lower the risk of suicide. Thus, if suicide prevention efforts are helpful, the suicide rate for the diagnosed patients who are treated should be lower than for diagnosed patients who, for whatever reason, shun treatment. The 2019 GAO report found that 18% of diagnosed patients did not get treatment.

Here are the results.

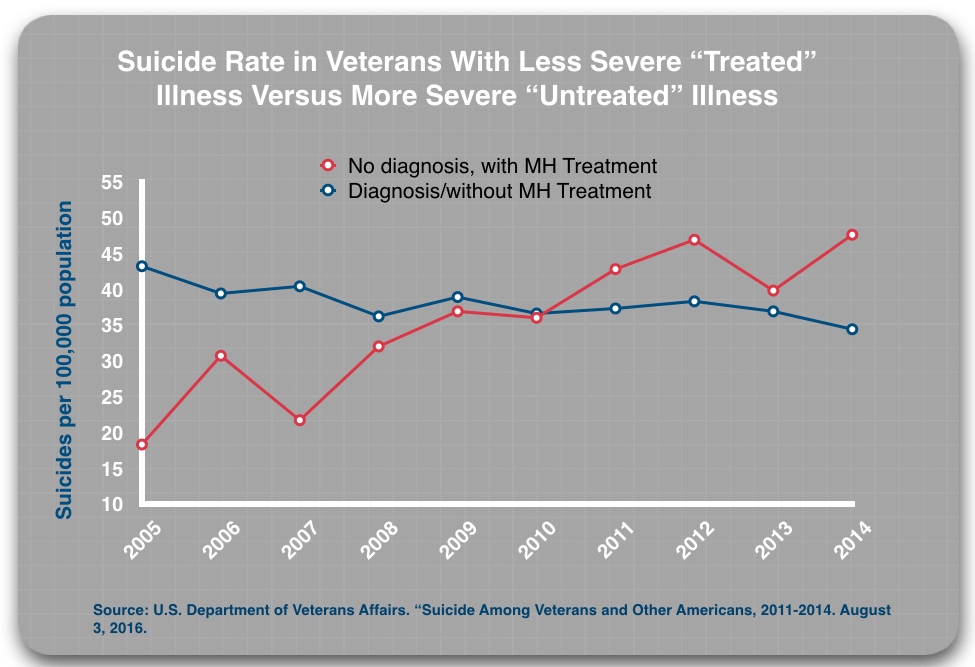

First, those without a diagnosis who got MH treatment were more likely to die by suicide than those without a diagnosis who did not access such treatment. In 2014, those who got treatment died at twice the rate of the “untreated” group.

Second, those with a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis who got mental health treatment were roughly twice as likely to die by suicide than those who had a diagnosis but did not access mental health treatment.

This difference in suicide rates for the treated and untreated groups is consistent over time, year after year. Moreover, these findings are based on the VA’s review of millions of patient records. The VA published them in a 2016 report that it touted as the “most comprehensive analysis of Veteran suicide in our nation’s history.”

There is a third comparison that can be made that leads to a particularly troubling finding. It could be expected that in any comparison between the less severely ill (the undiagnosed) and the more severely ill (the diagnosed), the less severely ill group would have a lower suicide rate, regardless of any treatment effect. Yet, from 2010 to 2014, those without a diagnosis who got MH treatment were more likely to die by suicide than those with a diagnosis who were “untreated.”

In sum, the data for the four subgroups tells of a suicide risk in 2014 that increased in this steplike fashion:

Undiagnosed/untreated: 24.8 per 100,000

Diagnosed/untreated: 34.4 per 100,000

Undiagnosed/treated : 47.6 per 100,000

Diagnosed/treated: 68.2 per 100,000

This is a finding that runs directly counter to the variable suicide rates that would be expected if “treatment” for a mental health condition were effective. However, it is a finding consistent with RCT data showing that antidepressants double the risk of suicide compared to placebo. In the comparison for “diagnosed” patients, that is precisely the increase seen in the treated group.

The Perils of Diagnosis

The suicide rates for those diagnosed with a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis have remained stable since 2005. Year after year they have hovered around 70 per 100,000 population. The reason that the suicide rates for VHA patients have been rising is that the VA’s suicide prevention efforts—the outreach campaigns and the mandatory screening—have led to a steady increase in the number of veterans diagnosed and treated for those disorders, and as the VA’s subgroup data shows, this moves patients into a category that has the highest suicide rate.

This gets to the mathematical heart of why the VA suicide prevention efforts have failed. The effort is based on the premise that screening will get patients into treatment that will lower their suicide risk, thus lowering the overall suicide rates. But the subgroup data shows that treatment is elevating the risk of suicide, which leads to this tragic equation: screening + drug treatment = increase in veteran suicides.

The rise in suicide among younger veterans reveals, with great clarity, the perils of screening that leads to treatment with psychiatric drugs.

The VA, as part of its suicide prevention strategy, has sought to bring younger veterans newly discharged from the military into VHA care so that an initial screening for depression, PTSD, and other psychiatric disorders can be done, and their suicide risk assessed. There were 1.2 million veterans who entered VHA care from 2002 to 2015, and 58% of those veterans were given a psychiatric diagnosis.

With this screening protocol and outreach in place, the number of 18-to-34-year-old veterans who received VHA care grew rapidly from 2005 to 2017, from 344,938 to 687,936. Given that 58% of veterans entering care during this period were given a psychiatric diagnosis, it is reasonable to conclude that a high percentage of this population were prescribed antidepressants and other psychiatric medications, which means they were ushered into the “diagnosed and treated” subgroup with the highest risk of suicide.

The suicide numbers tell the tragic result. The suicide rate for VHA-using veterans 18-to-34-years-old rose from 20.9 per 100,000 in 2005 to 51 per 100,000 in 2017, a 144% increase. Moreover, because the number of VHA patients in this age category grew as well, the total number of suicides by younger veterans in VHA care jumped from 68 in 2005 to 351 in 2017, a five-fold increase.

Veteran Suicides Outside VHA Care

The VHA is understood to provide care to veterans with greater social and medical difficulties than those veterans who receive care outside the VHA. Yet, in non-VHA settings there are similar pressures to screen for depression and prescribe antidepressants to those who are so diagnosed.

If such pressures are driving up suicide rates for VHA-using veterans, then it could be expected that they would do so in general medical settings as well. The VA’s 2019 report documents that this is so. The suicide rate for all non-VHA using veterans rose from 24.3 per 100,000 in 2005, to 33.9 per 100,000 in 2017, a 40% increase.

And just like in the case of young VHA-using veterans, the increase in the suicide rate among veterans ages 18 to 34 has been particularly pronounced in non-VHA settings, rising from 26.2 per 100,000 in 2005 to 41.1 per 100,000 in 2017, a 57% increase.

There is one other noteworthy element in this last comparison of suicide rates in the two settings. At the start of the VA’s suicide prevention efforts, the suicide rate was lower in VHA settings than in non-VHA settings for the 18-34 age group. Yet, since 2005, the increase in the suicide rate for young veterans in VHA facilities, where screening is imposed with a military rigor, has been much greater than in non-VHA settings. In 2017, the rate was 24% higher for VHA-using young veterans. This may be one more data point telling of the harm done from the VA’s suicide prevention efforts.

The Puzzle Pieces Fit Together

The rising suicide rate among veterans since 2005, which is when the VA launched its focused suicide prevention efforts, simply serves as a starting point for an investigation: is there evidence that could explain why such efforts would drive suicide rates upwards?

In this case, there is evidence of many types that fit together into a coherent whole. Specifically:

- Efforts to improve mental health programs and increase access to psychiatric drugs in global settings have led to increased suicide rates.

- RCTs have found that antidepressants increase the risk of suicide.

- Observational studies of depressed patients treated in primary care have found that those who take antidepressants have a higher rate of suicide during follow-up periods

- The VA reports tell of an increasing number of veterans exposed to antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs.

- In the VA’s subgroup findings, treated patients in both the diagnosed and undiagnosed comparisons have much higher suicide rates than the untreated patients.

- In the VA’s subgroup findings, from 2010 forward, treated patients without a diagnosis had a higher suicide rate than untreated patients with a diagnosis.

As can be seen, there is in this review a collection of evidence that tells of psychiatric treatment that increases the risk of suicide, with the RCT data for antidepressants at the center of this “evidence base.” The VA’s suicide reports tell of an increasing number of veterans diagnosed and treated with antidepressants, which could be expected to produce a rising suicide rate, and that is precisely what has occurred since 2005, when the VA initiated its focused suicide prevention efforts.

The VA’s Explanations for the Rising Suicide Rates

The VA reports tell of how suicide rates have risen for all veterans, both for those who use VHA care and those who do not. The VA offers several explanations for this rise in suicide in both settings.

First, it notes that this rise has occurred against a backdrop of rising suicide rates in the general public, and thus is not limited to the VA. Second, the VA explains that the suicide rate is higher for VHA-using veterans because, as a group, they suffer from a broader range of ills than the non-VHA-using veterans, such as physical illness, combat injuries, fewer financial resources, and homelessness. Third, the reports cite research comparing the two medical systems that found that “engagement in VHA mental services was associated with decreased rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.”

All of that may be true. But none of these explanations address the basic question investigated in this MIA Report: Do suicide prevention efforts that focus on screening for depression and other mental health disorders, with those so diagnosed then regularly treated with antidepressants, increase suicide rates?

If so, they could be expected to increase the suicide rate in the general public, in veterans that use non-VHA medical facilities, and in VHA-using veterans. And that is precisely what has occurred since suicide prevention efforts have been introduced into general medical settings, and into VHA care.

Harm Done

There have been more than 70,000 suicides by veterans since 2006, when the VA launched its suicide prevention efforts. It is impossible to calculate the extent of the harm done that is evident in this review of the rising suicide rates in this community of 20 million veterans. However, it is easy to conclude that if suicide rates had remained stable at the rate they were in 2006, there would have been 10,000 to 15,000 fewer suicides among our veterans.

That is a number greater than the total of all combat deaths since 9/11.

All of this begs for further investigation by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

People cling to their devout faith in the medical model’s “success” despite such evidence against it, because they wish it was true. As with any religion, reason and logic are ineffective in persuading people to question it.

Report comment

What’s ironic, however, is those claiming others have insane beliefs, are actually the most deluded people of all. “The inmates are running the asylums,” as they used to say. It’s long past time to flush the DSM “bible,” and end the human sacrificing psychiatric religion, and end their modern day psychiatric holocaust.

https://www.naturalnews.com/049860_psych_drugs_medical_holocaust_Big_Pharma.html

Thank you, Robert and Derek, for logically pointing all this harm being done to our veterans with the antidepressants. It’s shameful and heartbreaking.

Report comment

“The inmates are running the asylums.” And their treatments kill larger numbers of people than the “mentally ill” killers these self-anointed messiahs claim to be saving the world from.

Report comment

We’d be better off if the inmates actually WERE running the asylum!

Report comment

If being killed by your own army is now called “friendly fire”, what are these deaths considered to be?

Report comment

I am a US Navy Submarine Force veteran of the Cold War and Vietnam Conflicts. In the 1970s, before the diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was developed, I was diagnosed with schizo-affective disorder by Veterans Affairs psychiatrists. After eight years of hostile and unsuccessful treatment with psychiatric drugs which severely damaged me both physically and emotionally to the point of ischemic strokes and suicidal ideation, I was extremely fortunate to recover completely within a few months. I had learned about Orthomolecular Therapy based on tissue mineral analysis of a hair sample and Creative Psychology through my own research and in 1982 was able to obtain a source of these treatments independent from the VA and at my own expense.

The cost of Orthomolecular Therapy and Creative Psychology is a fraction of that for biological psychiatry and the culture of life-long disability it creates.

My VA-assigned psychiatrist, who later rose to the presidency of the American Psychiatric Association, refused to acknowledge my use of Orthomolecular Therapy, the hair test results, or Creative Psychology and termed my recovery a “spontaneous remission”. Since 1982, I have lived a healthy, productive life, free of not only the need for psychiatric drugs, but all other prescription medicines as well.

I later learned that the lab I used, Analytical Research Labs, Phoenix AZ, recommended to me by friends in the nuclear field, was already a VA contractor. The VA was using tissue mineral analysis, not for therapeutic purposes, but forensic ones, to detect the presence of substances vets might have used in an attempt to self-medicate.

In 2007, concerned about the suicide rate of veterans diagnosed with PTSD, I began to attend a PTSD group at a VA CBOC Clinic. After only a few meetings where I shared my story with other veterans, I was taken aside by an unlicensed VA psychologist and VA psychiatrist, a graduate of a one-star foreign medical school. In a twenty minute interview they diagnosed me with paranoid schizophrenia, a rare and extremely disabling condition, and banned me from further participation in the PTSD group.

When this new diagnosis affected the renewal of my life insurance policy, I requested the medical records of my recovery in the 1980s. I discovered that all such mental health records in DVA VISN 1, in the 1978 to 1990 time period, had been spoliated. No records remain. I am convinced that thousands of veterans could have made recoveries similar to mine, with thousands of lives saved, had VA psychiatrists run studies on Orthomolecular Therapy and Creative Psychology instead of destroying all evidence of a veteran’s drug-free recovery and attempting to discredit him. I have recently been examined and tested by well-qualified civilian forensic psychiatrists and a QTC, Inc. C&P medical examiner, who find in me no evidence of any mental illness.

Report comment

You were lucky, Subvet416, to have found this out. Had the VA shrinks found out you were going orthomolecular, they’d have twisted themselves into pretzels trying to stop you from using this deluded form of treatment. I just keep taking my B3 and don’t let any mental health personnel find out what I’m doing. Surely I must be tortured by side effects I’m unaware of, despite taking megavitamin B3 for 45 years (plus assorted other nutrients).

Report comment

bcharris, to quote the tittle of Jimmy Doolittle’s autobiography, “I Could Never Be So Lucky Again” B3 is good, but try the flush-free version, nicotinamide. If anyone wants to quit smoking (nicotine addiction) Flush-free niacin, vitamin C and chelated zinc will quell those urges.

When doctors try to tell you there is no test for schizophrenia, inform them of this: Abram Hoffer, MD discovered back in the 1960s that those diagnosed and hospitalized for chronic schizophrenia will almost never flush when given a large dose of niacin.

Report comment

I have, but I prefer niacin. Because I have a history of excessive drinking and doping, I don’t mind flushing. Besides, taking 6g daily (2g t.i.d.), I only flush first thing in the AM or if I dally with midday doses. Anyway, now I only feel the flush, but I usually don’t turn red.

Besides, this gives me the opportunity to play evil pranks on those who like to ransack other people’s cars. A dozen 500mg. tablets in a bottle that says “take one at bedtime” stashed in the glove box makes a perfect gift for such individuals. Besides, this way the thief has enough tablets to give to friends.

Report comment

After a few days on SSRIs I experienced an extreme lowering of anxiety, to the point I felt no anxiety or fear at all. Other emotions were different or absent as well. For example, I felt very little empathy for anyone.

As far as I know, these two are actually common and documented “positive” effects of SSRIs.

I remember thinking about suicide. It was nothing special, just an everyday thought that I am sure everyone has from time to time. But this time thinking about it felt so easy, there was no fear at all, no worry about my family, no fear of death, no fear of possible pain.

I was so numb that probably anything could happen, I would be just a silent observer of my surroundings, not able to react emotionally to anything. This almost emotionless state was extremely weird, something I never experienced before and never thought was even possible. My thoughts and beliefs were my only guide but even these were changing, becoming much lighter and carefree than usually. But still being in a negative thought pattern at this time, I now see that instead of noticing that I lost my fear of living, I only noticed how I lost my fear of dying.

Report comment

I heard an almost exact replica of your description from a coworker who was taking Zoloft for migraine headaches, not “depression.” She was shocked with how “reasonable” the idea of suicide seemed to her, just a casual thought, like, “I could go to the store. I could kill myself.” I do think the “positive effect” of SSRIs is a lessening of empathic connection to others. For some people, this will feel like a relief. For others, it will make things seem reasonable that would have seemed outrageous before. Including suicide or murder in some cases.

Report comment

Exactly! Wasn’t it here on MIA, this post about a study published in Nature, about how “protective” it is, when SSRIs lower the empathy of those suffering from depression? For me, another problem I noticed was this extreme lowering of anxiety itself. OK, it can be great, you have no social anxiety anymore, you feel confident, you can do anything, it’s great. But besides of not being afraid of fun things, other people, living my life etc. I was also not afraid of death, pain, any consequences at all. ALL fear disappeared. I agree about murder as well, just did not mention it above, because it’s even more taboo. When I decided to stop with the drug, the first emotion that came back was actually aggression, before everything else. I noticed like I chemically somehow turned into a psychopath 🙂 From this experience, I now wonder, what if these drugs can directly, without any “psychosis” in between, chemically cause a personality disorder by changing the emotional profile (e.g. anxiety down, empathy down, aggression up) of a person and without this person being morally depraved? Still, most people who take SSRIs (anxious, not able to stand up for themselves etc.) would probably benefit from a very small degree of antisocial personality disorder 🙂

Report comment

My suicidal urges melted away after I had lowered my effexor more than 50%.

Report comment

psych-guilds…

manifest functions — ‘treatment of mental illness,’ especially ‘severe mental illness.’ (re)integrating the afflicted/’sick’ person into society, or perhaps providing ‘long term care,’ when appropriate.

latent functions — control. punishing outliers, misfits, the poor and working classes, non-whites, non-males. creation+control of a (growing) under-class. profit. infiltrating and subverting the major social institutions (education, family, religion, etc.).

this is mostly lifted from Szasz, of course. I think his last book is Psychiatry: the science of lies, or something to that affect. An industry built upon lies might be expected to flourish–with enough gov’t cash infusions, social support, etc.– in ‘sick’ (anomic, violent, disintegrating) societies. Societies that are not as ‘sick’ probably have less use for such an industry.

Report comment

I think it’s critically important to go back to emphasizing that the majority of mass shooters were on psych drugs, and that psych drugs, particularly SSRI’s, can make people crazy that way. I know, then you risk being called a scientologist, but I really feel it’s the only way to finally pop this balloon of insanity regarding what psychiatry really is, what they’re really doing, and of course regarding their drugs. Of course the relevance to this article is that the majority of mass shooters kill themselves afterward.

Also think about that…

In that situation, shouldn’t someone be surging with adrenaline, defecating and urinating themselves? Puking even. Yet somehow these shooters are chill as ice and then pop goes their head.

As if they were numbed and desensitized by something…

Report comment

The VA seems to use the same tactics as psychiatry to dodge questions and whitewash evidence of the harm they are doing. As we prepare to honor veterans on November 11, 2019 this is a chilling and timely report that pays tribute to their courage and the high price so many paid to serve. I hope the VA sees this report and wakes up to the dire facts and statistics that are clearly presented in this report. Thank you Robert and Derek for putting together this outstanding and thoroughly researched report.

Report comment

Screening + Drug Treatment = Increase in Veteran Suicides = Not a Good Advert.

I can identify with suicide attempts on drugs; and genuine recovery with routine non drug approaches.

Report comment

Bob and Derek, great work in pulling together these various sources of data.

(1) As you know, in my 2011 book, When Johnny and Jane Come Marching Home: How All of Us Can Help Veterans, https://www.amazon.com/When-Johnny-Jane-Come-Marching/dp/150403676X/ref=as_li_ss_il?crid=1QTVHBGHEWJI&keywords=when+johnny+and+jane+come+marching+home&qid=1554480516&s=gateway&sprefix=When+johnny+and,aps,220&sr=8-1-fkmrnull&linkCode=li1&tag=whejohandja0d-20&linkId=1dbd7dedc192a717801d8a2ccc9ed082&language=en_US I spent three entire chapters writing about this very thing…and much more. Chapter 3 includes detailed analysis of the problems with not only “PTSD” but other psychiatric labels being harmfully applied to servicemembers and veterans whose deeply human reactions to war trauma, military rape trauma, and so on were thereby pathologized and about the harmful use of psych drugs as a result of that pathologizing; Chapters 4 and 5, respectively, are about what the military has been doing and “why it’s not enough” and what the VA has been doing and “why it’s not enough.” In Chapters 4 and 5, I track the DOD’s and VA’s press releases, showing a pattern of their expressions of dismay about suicide rates, bewilderment about their causes (usually avoiding any mention of numbers of deployments, the moral anguish coming from lies they had been told about how the military was being used and what was really happening, trauma from participating in or witnessing acts of war, and military sexual assault), and claims that they were introducing new initiatives to try to prevent suicides…followed by similar press releases with “new approaches” and continuing avoidance of real causes the next time. A long time ago, I met with the two top people in the Army who were then in charge of what they called suicide prevention, and they said their two main initiatives were to emphasize that “Army strong” includes acknowledging when one needs help and trying to get people more “mental health care” sooner. They were clearly totally uninterested in the serious problems I pointed out (politely) about each.

(2) Many years ago, Col. (Ret.) David Sutherland and I wrote an article about the four main reasons veterans kill themselves, and two of the reasons were those you mention: the diagnosing of them as mentally ill and the use of psych drugs. (Sutherland, Col. (Ret.) David, and Caplan, Paula J. (2013). Unseen wounds. Philadelphia Inquirer. http://www.philly.com/philly/opinion/20130210_Unseen_wounds.html )

(3)The long-famous “22 veterans commit suicide every day” statistic was based on VA data from only 21 states, not including California and Texas, whose veteran populations are huge. It would be good to find out — if it is in fact possible to do so — whether the VA’s current claim of “20 a day” is based on all states reporting, as well as how they defined “suicide,” since sometimes causes of death are mistakenly applied as cover-ups.

(4)A great addition to your article would be description of what truly does help, and so I refer you and your readers to the Listen to a Veteran! Project, which has definitely been shown to reduce veterans’ isolation, which is of course a major cause of suicide. listentoaveteran.org This is a completely free service, in which a veteran from any era (combat or noncombat, woman or man) is paired with a nonveteran who is NOT a therapist and who truly JUST listens with their whole heart to whatever the veterans wants to say. Data from a Harvard Kennedy School study and subsequent data have shown these simple, private, unrecorded sessions to be stunningly helpful for the veterans and life-changing for the nonveteran listeners. I also refer you to the 28 nonpathologizing, non drug, low-risk or no-risk approaches to helping veterans and their loved ones that are presented in extremely brief (10 minutes or less) videos filmed at the conference I organized in 2011 at Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance. It was called “A Better Welcome Home,” and the videos can be seen at http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL51E99E866B9D735E Several Pentagon higher-ups have requested this information, and we urge not only veterans and their families but also anyone who is suffering to go to that site, find a few approaches that resonate for you, watch the videos, and try those approaches.

(5) Yesterday I posted the following to mark Veterans Day on my Facebook pages and on Twitter:

Easy, wonderful things anyone can do to mark Veterans Day (before, during, and/or after):

(1)LISTEN TO A VETERAN! Truly, just listen…with your whole heart. listentoaveteran.org

(2)Go to https://whenjohnnyandjanecomemarching.weebly.com/listen-to-a-veteran-psas.html and watch any or all of the 9 very short (10 to 45 seconds each) “Listen to a Veteran!” Public Service Announcements that won a Telly Award — and see whom you recognize and if you have a favorite one.

(3)Order and watch — or give as a gift to a veteran or veteran’s loved ones or a caring nonveteran — the 50-minute, awardwinning film, “Is Anybody Listening?” isanybodylistening.org is the film’s website, and you can order the film at https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B07ZMJBPM1/ref=share_ios_movie

Report comment

Did I miss an entire section devoted to the prescribing of meds to active duty soldiers to help them overcome the reality of the battlefield? If they drug-up while in the service, what is the expectation for the day when they are no longer on active duty?

Can we expect drugged up active duty soldiers to transit to civilian life with/without meds? If they are getting meds while in, then get cut off when a civilian, how does that factor into this analysis?

Although an informative article, I believe the key piece of information – their treatment while on active duty – needs to be included and addressed herein.

Report comment

There are drugless techniques that can be used to keep troops in the field longer, but I’m not revealing anything to the Green Machine’s poohbahs if I can help it. The lifers would just use any such techniques to keep their troops forward for truly excessive time periods, so they’d go bananas anyway.

Report comment

The con game of naming drugs as “medicine” is evident in this report of Whitaker and Blumke.

Thank you for the work of accumulating all the evidence and putting it together.

Hopefully the science will not be overlooked by those paying the bills. Not getting what they are paying for.

Report comment

You make a very persuasive case that that suicide prevention efforts and treatment with antidepressants increase suicide rates. But you also state that antidepressants help some people and that VHA mental health services decrease rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

So is there a way to target antidepressant use mainly to those who will benefit? And is there a way to give mental health treatment only to those who will benefit and not to those who will be harmed? Or do you feel that antidepressant use and VHA treatment are so deleterious that these approaches should be abandoned, even if some people are helped?

Report comment

There is a way to target such drugs, but the tests enabling one to do so are ridiculed by Big Time Psychiatry, which despises quantifying symptoms, in lieu of blindly following the advice of Big Pharma salespeople pushing the latest psychiatric Wonder Drug (you wonder why it was prescribed for you when it doesn’t do anything constructive for your condition).

Report comment

Excellent report. I appreciate your thoroughness. Subvet416 above gave an interesting option to help folks- Orthomolecular Therapy and Creative Psychology. I have used TRE-Tension/Trauma Release Exercise developed by Dr. David Berceli. He developed it to use on populations that have been through a war or natural disasters as a way to release the trauma of a crisis event.

It is an amazing modality and easy to do no matter your ability.

I agree that psych drugs can cause you to become suicidal. I was on them for 13 years and the years I was on the most drugs are the years I was most suicidal and in the hospital. Once I reduced then stopped the meds I regained my sanity. Unfortunately, the meds had a detrimental effect on my body. I now have Temporal Lobe Seizures along with kidney problems.

The information you gave in this article is invaluable for those beginning their emotional journey.

Report comment

After typing Mad in America in the search bar of ‘DuckDuckGo’ tonight this UTube video came up first. Wow! I had not known the full extent of Robert Whitaker’s work around the world. If you have not seen this video it is definitely worth watching. A very engaging presentation and very compelling information!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DliuhZJR9A

Report comment

Very interesting Open Dialogue explanation within this UTube video for ‘psychosis’ – but no amount of analysis could have helped me deal with “my High Anxiety” on attempting to withdraw from “antipsychotics”.

But “CBT”/”Buddhism” did help me deal with this “antipsychotic drug” induced “Stress Disorder”.

So the Non Drug Approach can work successfully at both ends.

Report comment

Thanks for this. I have some questions.

What about gender specific stays and research? And I would like to know about the LBGQT folks as well. So much research is male only.

What about other disabled vets? What works and what doesn’t work for them and my guess is there are emotional issues with them as well.

After WWII the VA thought chicken farming was the solution for vets with visual issues. As a Social Worker, my mother worked with them and thought it was not the best idea.

The other question is why the difference in handling trauma generationally?

WWII vets mainly kept it to themselves and it only leaked out as they aged. Vietnam Vets had their own support and active groups- kind of forced to because no ticker tape parades for them.

What about race?

How do entertainment and media affect Vets and the VA?

How does the volunteer army affect all of this?

What about the families? In the not to distant past there was the beginning of some understanding of intergenerational trauma. This now seems to be a moot and forgotten point.

Glad this is out there. I heard about this through a friend who lost their child to suicide. The families of Vets who lost their vet to suicide was her great help.

This was one our local NAMI was sending folks to wakes of suicides. So much for that.

Report comment

NAMI sends folks to wakes of suicides?

Do you think they’re trying to cover for the role psych drugs play in so many?

Disgusting vultures! No shame at all. Anywhere to promote their cultish ideology.

Report comment

Yes at one time they did. Just happened to have an off the cuff conversation with the employee. I don’t think she had any idea. I knew the family that she was going to visit. I did not say anything because not only couldn’t believe as a professional who had worked in the system but knowing folks who had lost children and others appalling. Their help was mostly not help. But if one didn’t know or didn’t know any better or had no knowledge of past history it would seem oh how great.

This is my one great great frustration because the net of biopsychistry and big Pharma is so very very all encompassing so that so many are blinded or made

deaf and not their fault. It takes years to figure it out and even I was trapped. And then the Sciencetogy issues . No no it’s not that at all!! The history of survivors has been almost all but squashed.

Report comment

And for those reading the local ADDAMS Board was run by a politician. There had always been issues but with the overtaking of the board things became so much worse. The politician had no college degree but had supervised the safety forces of our local big city with no police experience . Nada. It was a ripe for deaths . Check out the stories of Tamar Rice and Taneesha Anderson.

Ineptitude and ignorance all the way around. And the Board was really good friends with NAMI. They allowed the group rooms for free. The city also was home to many hospital systems so my best bet is that research money and PR money just rolled in. No one saw the problem like I did and I think as one professional said I was figtuvely taken prisoner.

So few folks in my local don’t see the big picture. When the head of the ADDAMS Board retired he was lauded not only by the powers that be but by a local Irish Cultural society. The very folks who had so called skizophtenic relatives thought he had just done great.

I pass by where Tamir was shot. I can go down streets and show you the homes where suicides took place. Not just one or two but more.

I live next door where a woman said

I know what I will do I will call the police and she did. One of the most humiliating times of my life. And it was a circus. Everyone came out to see what was happening. The kids were texting their friends( their fault driving way too fast but teens other teens have done in the neighborhood I have seen it but no one does nor call police . Stupidly personified.) It was a suburban circus. I still live here though I did try to move away several times and things kept getting weird finally after a nice infestation after the fourth move I just came home to exist. Not live but exist.

Actually the local cops were better than others so go figure.

It just seems to be a huge mess and it doesn’t seem to get better.

I walk the dog and people wave but the memories are still there and maybe they are new but it doesn’t matter because I was destroyed that day and on several others. Family most have no clear idea. And silence is the rule. Today with another shooting, today with more outrageous news of the corruption on high in not only government but let’s say the Roman Catholic Church. They still are dealing in untruths.

The Congressional Rep from Ohio Jim Jordan was aware of sex abuse on the OSU wrestling team and did NOTHING yet is being a great voice in the impeachment trial so to speak. I took Sex Offender Training- Loss And Ross Associates on the same campus paid for by the State if Ohio – a mere few years before he coached there. Sex Abuse was known by then.

Even Corrie Ten Boom felt anger and hate with her former captor’s apology. She chose love over hate but a struggle right? So many of us don’t get an apology. Just the exquisite pain of seeing things go down the drain over and over again. Our house will not sell. Not enough money to walk away. I just would like the lady years to be in a peaceful quiet place near trees. One level small. I have been maxed out.

Thanks for reading if you got this far. The change seems at times like today totally impossible. I really wish I could be more helpful.

Report comment

Only my faith–which some call irrational–that all will be made right and those who do evil will not be allowed to continue forever keeps me going.

Forgiveness means determining to do your enemy good–if you can–and not seek personal revenge.

It does not mean:

Calling evil actions good.

Thinking your enemy is a great guy.

Feeling good about the damage done.

Report comment

One of the great traumas of my life involved asking for help from the VA and, for some reason, shipped off the to the local State Hospital, where absolute hell descended upon me.

Mental health isn’t about a disease, it is about trauma, about learned dysfunction, and the incompetent meanness of the mental health system nearly killed me.

Not an exaggeration.

I want to thank those in the psychiatric survivor movement, and to Bob Whitaker, for their continued work in supporting the lost and bewildered.

Hugh

Report comment

Hughmass, it is heartbreaking to hear what the VA and the state hospital put you through. Occasionally I hear of someone who got real help from the VA, but is far more often that I hear nightmarish stories like yours. You deserved so much better! I invite you and other veterans to go to listentoaveteran.org and see if you are interested in having a totally private, nonjudgmental, free listening session from our Listen to a Veteran! Program.

Report comment

I am incapable of imagining suicide in “Mental Health”, not being related to Psychiatric Drugs.

Report comment