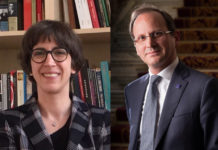

Rosie Phillips Davis was the 2019 president of the American Psychological Association (APA). Davis is the former Vice President for Student Affairs and a current Professor of Counseling Psychology at the University of Memphis. Her research and advocacy projects address the power of inclusion, multicultural vocational psychology, psychological ethics, and living well in a diverse society.

She previously served on APA’s Finance Committee and Board of Directors, the American Psychological Foundation Board, the Council of Representatives, and the Society of Counseling Psychology (Division 17). She has served on the editorial boards of multiple journals, including the Journal of Career Assessment, and has authored and edited numerous articles and book chapters on career counseling.

Davis is a decorated psychologist, with awards including the Janet E. Helms Award for Mentoring and Scholarship, the Arthur S. Holman Lifetime Achievement Award, the Distinguished Professional Contributions to Institutional Practice for APA Award, an APA Presidential Citation, and was named an Elder by the National Multicultural Conference and Summit.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity.

Gavin Crowell-Williamson: In previous interviews and your TED talk, you have discussed how your experiences growing up influenced who you are as a psychologist. Can you give me a general sense of what your childhood and upbringing were like?

Rosie Phillips Davis: I was born in the state of Mississippi to parents who were sharecroppers. I actually lived on a plantation until I was around four or five years old. Then when my father moved to Memphis, Tennessee, we followed. My father worked as a garbage man for the sanitation department in Memphis, and he also worked some part-time jobs, like cleaning for Baptist Hospital. My mother sometimes was at home, and at other times, she cleaned homes for white women at the time. Much later in her life, when I was an adult, she did work for the Memphis furniture factory.

When we grew up, there were 12 of us. I am my mom and dad’s first child. She had two girls, and he had two boys when they got married. So most of the time, there were about nine of us living in my household, and we were pretty poor.

Crowell-Williamson: You had spoken before about how public school influenced you. What made that educational experience so important for you?

Phillips Davis: I went to segregated schools. I had black teachers, and the teachers, as well as the schools, were so much a part of the community in which I grew up. When I was in high school, my calculus teacher lived down the street. Now, she lived in what seemed to me to be a big beautiful brick home, and ours was a little poor shotgun house, but, nevertheless, she lived down the street. I can remember walking to school and a teacher stopping to pick us up to give us a ride. They took a particular interest, and it did not seem that their interest ended at the school door.

When I was a junior and a senior in high school, the teachers even helped with me getting to the prom. They paid attention to lots of demands on us and had an expectation that we would do well. Now, that is not to say it was a perfect situation and that we did not have divisions even within that public school setting. The power and the impact of that school are evident by the number of people from my high school, for example, who still go to a reunion every year. My class still has class meetings, and we still raise money to give back to the high school. You hardly see that in a lot of places, but that is amazing to me.

When I became President of the American Psychological Association, I realized that the president of the American Psychiatric Association also went to public school in Memphis, Tennessee. While we can drive in Memphis and see a billboard of a rapper or somebody like that, and it will say, “I’m a product of the public school system,” I could not even get a news station to cover that Dr. Stewart and I are both products of the public school system. We don’t value it enough. We don’t make it clear enough that a child going through a public school system can grow up to make a difference without being a rap artist, though it’s not that I don’t think that’s a great thing too. It’s just that it’s probably easier to gain success as a psychologist or psychiatrist than a famous rap star.

Crowell-Williamson: We live in a culture that shapes our perceptions of what is normal on a daily basis, and we learn early to categorize people in poverty as “other.” Can you speak to how your upbringing and experiences shaped your approach to psychology?

Phillips Davis: Well, my growing up in the United States and growing up as a poor and African American taught me that our society creates power dynamics among groups of people. I felt like an “other.” I felt like a person who had to prove my smarts; prove that I am good enough. I had to live and still live in a racist society that devalues people based on looks, economic status, where we live. Now, I believe that it is just a human quality that we other.

Quite frankly, I’ve come to believe that it is a survival instinct to put ourselves into groups. All things in nature put themselves into groups, and they do it for survival. We allow people to create fear in their group about “the other,” and we become subject to powerful forces that don’t have our best interests at heart. So, yeah, I believe that I was taught that I was an “other,” and the messages around me reinforced this.

Crowell-Williamson: I would love to hear about your professional journey. For instance, did you always want to be a psychologist? What sort of clinical work and research have you done?

Phillips-Davis: I do not think I always wanted to be a psychologist. When I was a teenager, I had all kinds of interests. I was a reader. The thing that helped me more than anything is the fact that I loved to read, and I had a vivid imagination. I thought about being a spy. I loved dancing when I was really young, but we were too poor for me to conceive of dancing as something that anybody did and we didn’t have any dance lessons, so that was not an option.

I thought at one time about being a psychiatrist. I can remember it very clearly, I was about 15, and I saw some people with “mental illness” in a park. We had segregated parks in Memphis, and this was during a time when black people could be at the park. It was some kind of “mental institution” outing in the park. I had no notion of what any of this was, and they were acting very strange to me, and so I decided no, I do not want to do that. But I like helping people.

When I went to college, honestly, I talked to a professor and said that I loved history and that I want to be a history teacher. He said history teachers are a dime a dozen; you’ll never get a job. I told him that I like helping people, and he suggested that I major in sociology. Later, when I told him that I was bored by my first sociology class, he told me that it would get better in upper-level classes. I am fond of telling people that I graduated bored.

When I graduated, I tried to get a job in Memphis, but I had no luck. I moved back to Chicago and worked in corporate America. I found that I had no idea how to deal with the difficulties that people had that I had to manage as their 22-year-old manager (I would end up with people crying at my desk) and knew I needed to get some more training.

I went back to graduate school, not even knowing about a thing called Counseling Psychology. I just thought I’d go back and be a counselor, maybe be a guidance counselor or something. I was in a program at Ohio State that enabled me to take courses in something called the Student Personnel Administration Program. For some reason, I took most of my courses in counseling psychology.

When I was an undergraduate, I was very active. I was growing into being a black person, not a “Negro,” a black person. It was in the era of ‘say it loud, I’m Black, and I’m proud.’ I began to wear my hair natural. I met some Black Panther people, like Fred Hampton, who was in the Chicago area and on our campus. I knew him when the police shot him and Mark Clark. Now, I’m amazed to think that they were pretty much teenagers, no more than in their early 20s when they were gunned down. We looked up to them because Fred Hampton was a very kind man when he came to our campus, working with us.

On that campus, I matured into being an activist. I did not consider myself militant. I was trying to help do the right thing. In 1968, my family was back in Tennessee when Dr. King was killed. At that time, I was in a room negotiating with some white students because we all decided to form a sorority. They had gone behind our backs — we didn’t know that sorority and fraternity structures were very segregated. Another friend of ours came and slammed the door open and told us they had killed Dr. King and asked what were we doing in there?

Later in my senior year, I was a co-chair of a black student organization called the Black Leadership Organization Consolidated. We came up with this activist program when black football players had gone on strike, and we had a meeting with the president of the institution and the football coach. The president at the time, Don Kleckner, was so good. He listened carefully to us and arranged a conversation with the Board of Trustees to talk about having black professors and black history courses and things like that. He was a very thoughtful leader who did not have us put in jail, and we did not end up with riots on the campus.

I did not even know what happened to Dr. Kleckner after that. I assumed they fired him, but either way, he was not there the next year. When I became an assistant vice president at the University of Memphis, it dawned on me that it may have been because of the way that President had dealt with us as human beings, respectfully. He gave us time, he listened, and he let us have a voice with the Board of Trustees. By the time I was an assistant vice president, I had realized what an amazing blessing that was. I went online trying to find him and found that he had died a year earlier, but I got a chance to say thank you to his children because he listened to us during a turbulent time in our country. I have been privileged in many ways, to fight for things I believed in, and had some people who supported me.

Crowell-Williamson: Can you discuss your rise to the American Psychological Association (APA) presidency and highlight what you hoped to accomplish as the president?

Phillips Davis: I became active in APA back in the 80s. When we were trying to get an accredited internship at the University of Florida, the consultant chided us for not being members of APA and said, ‘shame on us for not having joined.’ It was a lonely journey at first because APA was not different from many organizations at the time — it was hard to find a black person. In my particular specialty area, it was hard. Over time, people would ask me if I would do something, and I tend to say yes to things. Like I said yes to your interview. I think if you say yes, and do the work, then people ask you to do something else. Through Division 17, the Society for Counseling Psychology, I became active and ultimately became president of that organization. I was president in 1999. We went on to form the National Multicultural Conference & Summit, which still goes on to this day.

After being President, someone asked me to serve on the Council of Representatives, the governing body for the APA. I had no idea what it was, but went on and found out that it was the political governing body for APA. While I was on the board of directors, people in APA were having a fight about being a scientist or being a practitioner. I found the whole argument ridiculous, so I ran for president back in those days not to be president (I would come home and pray at night, ‘please don’t let me become president of this organization’) but to create a platform to say that we are all in this together. That psychology cannot exist without scientists and practitioners.

Luckily for me, I didn’t win, but then they wanted me to be a part of different committees, and I let my name be entered into nominations to run for service and things like the Board for Professional Affairs. I think once you get involved with things, just like you’re involved with Mad in America, there’s always something that needs the attention of people who are willing to volunteer their time and energy. So that’s the way it is: If you say yes, people will ask you to do the work, and then if you do the work, they’ll say let’s do some more work. Finally, I was done with that kind of service.

Once I was finished with my term on the board of directors, I realized I was gone so much that it was having an adverse effect on my team back at the University of Memphis. So I was really finishing up my work for APA because I needed to turn so much more attention to my job. But a staff member from APA called me and asked me to serve on the finance committee. I had turned down all requests, but I figured if a staff member sees something in me, they must see something they need. So I went on the finance committee.

When I was about to serve my second term, someone asked me, out of nowhere, to run for president of APA in 2017. I thought I was done doing service with APA. I had even changed my name to Davis and had stepped down as Vice President at the university. I thought I was getting ready to go into a life of teaching, not working in the summer, and traveling with my husband. That was my plan for my life.

I had turned down all prior requests to run for president, but this particular woman called and asked if she could nominate me to run. I finally said, “okay,” not thinking that I would actually run. Then all these nominations started to come over email, and I said to my husband, how would you feel about me running? And he felt like he just got his wife back from being vice president! So he and I just agreed that if I got 100 nominations, I would run. If I got less than that, I had a graceful way to say thank you, but no, thank you. I honestly thought I’d get between 40 and 60 nominations to run.

The Chair of the nominating Committee called me and said you have 119 nominations, and so I thought okay, there is some reason that people want me to do this. I agreed to run, and people started writing to me offering to help; one person had run campaigns for people in DC. I never even dreamed of having a campaign.

We had been through a hard time at APA with the Hoffman Report, and they all have to deal with everything people have been saying about torture, so when they said people wanted and needed me to run, I agreed to do it. I came to the whole focus on poverty, from nothing to do with running for APA but from previously listening to things going on in this country during the presidential election. Everything that came together, I think, just meant that I was the person for the job at the time.

Crowell-Williamson: When you accepted arguably the most prominent role in the APA, you were doing so at a time where there was distrust surrounding the organization, following the uncovering of APA’s collaboration with the Bush administration (see Hoffman Report) regarding the torture of prisoners…

Phillips Davis: APA was not collaborating. That’s a mistake.

We had two psychologists who were not APA members who designed the program, and they made money from it. It looked like maybe there were some folks who did training with parts of the defense department, but it was not APA. APA is 120,000 people, most of whom knew nothing about it, even the person who was the CEO of APA knew nothing about some of the training that was going on. It was not APA as an organization. That is a fallacy. However, APA was painted to look like that.

Crowell-Williamson: Well, there was a feeling of general distrust in the air around APA. As someone who has a deep investment in social justice, did you have any trepidation about taking this role during a time of unrest? Or did you view it more as an opportunity for reconciliation and growth and kind of restoration of the public image?

Philips Davis: It did not even come to my mind when I was accepting the nomination. Most of the psychologists I know, probably all that I know, came into psychology to do good. That is what I find is still the truth about psychologists, even when we get it wrong. I find that people are doing their best to do good in the world.

Here is what I do know: even those people that do not know enough about what happened at Guantanamo Bay were trying to make sure people did not get hurt. We were not involved in that airplane that crashed into a building, killing thousands. It is easier for us to forget the fear that went on in the country at that time. Even then, I think people were trying to do good, not trying to do bad.

Even though you have a person here and a person there who is skeptical of APA, like you mentioned, I find that a large majority of people do not have that sense that you’re talking about, and that people are here to really do great things. I’ve been talking about poverty, talking about immigration, talking about gun violence, all of those things, that APA has stepped up to do. People are doing those things. People are fighting for research. They are fighting for access to healthcare. They are fighting for mental health care.

Crowell-Williamson: Transitioning a little bit into the deep poverty initiatives that you briefly mentioned. In September of 2017, the US Census Bureau recorded the highest level of extreme poverty since it began tracking the metric in the mid-1970s. So what do you think accounts for the continual worsening of this disparity? What do you believe can be done about it both from a societal perspective and APA’s perspective?

Phillips Davis: So a couple of things. First, going back to what caught my attention. In 2016, I was listening to NPR, and I heard a report about research by Chetty and Hendren. Chetty and Hendren found that if you are in the bottom economic quintile, your chances for reaching the top economic quintile in the United States was about 12.9% for those living in San Jose, California, but in Memphis, your chances are 3%. I am in Memphis, Tennessee, and I was in that economic bottom quintile, and said, “I’m a miracle, and my husband is a miracle.”

The next thing that caught my attention was a conversation about manufacturing in the United States and what is happening in counties in Ohio and Pennsylvania. For white men, in particular, they could rise to the middle class with those manufacturing jobs. However, with coal mining jobs going and with manufacturing jobs going, those individuals are now poorer than they have ever been. They talked about the use of opioids, and deaths from drug overdoses going up, church attendance going down.

In 1968, the white mortality rate was 30% higher than that of black individuals. Now, in some areas, the mortality rate for some whites is 30% lower than blacks. Why, in a country like the United States, are we allowing that? I have some notions about why that is, and part of that is the widening economic gap. In this country, we are catering more to the upper 1%, upper 5%, and we are designing policies that are detrimental to poor people. We are cutting safety net programs so that people can’t even get on their feet. We follow a narrative that it is the individual’s fault.

I am around poor people, and the poor people that I see are trying to work; problems accumulate that keep you from getting out of the hole. You fall down deeper and deeper. If, for example, your car breaks down, you cannot go to work, and then you do not have enough money to pay for your car. Alternatively, you get ill, and you cannot go to work. It is the way that our system is structured that causes poor people to remain poor people.

Privileged people start ahead of the game. It is an unearned privilege. Ann Richards, years ago, was making a joke I believe about Bush. She said he was born on third base and believed he hit a home run. That is a part of the way that I see it, that when you have privilege, you start further down the road, and wonder why those poor people who are way behind cannot reach you or keep up with you.

Crowell-Williamson: At this point, there have been decades of psychological research that finds an association between poverty and indicators of behavioral, mental, and physical health. So what do you think is novel about the way the deep poverty initiative addresses this phenomenon?

Phillips Davis: The reason that I wanted to focus on deep poverty is that it represents a small group, and it is more dire and harder for those individuals to get there. It was drastic enough that people could hear it and understand it. When I come to groups, and I say that poverty has a federal definition, for two adults and two children right now, that’s about $25,500, and they’ll say that’s horrible. Then when I say deep poverty is half that, two adults and two children living on $12,500 a year, they are aghast. I think people can see it, and hear it, and begin to understand it and know that it is ridiculous.

I think that we can begin to shape the narrative so that people understand rather than going on stereotypes. People can see images and realize that so many of those people living in poverty are women and children. When you can begin to see that it is a child who does not have something to eat, we know that we can do something about feeding children. I think that’s what happened. They were willing to say, okay, I can do something about it.

Crowell-Williamson: Recent research finds that people in poverty do not benefit as much from psychotherapy. One study suggests that poverty is “a major hindrance to the successful implementation of psychological care. From this perspective, reducing socioeconomic deprivation, promoting equality and social justice are important social policy goals that extend far beyond the confines of psychology and mental health care.” What are your thoughts on that?

Phillips Davis: I think that’s absolutely correct. I think we ought to declare poverty as a public health problem. It’s a big job that requires we have a big partnership, frankly.

The Women’s Foundation for Greater Memphis is a research-based organization. We founded it almost 25 years ago to help women reach economic self-sufficiency. One of the things that the research tells us is that to change poverty in this country, we need to take a neighborhood approach. This is exactly what they have done. They have taken a neighborhood in Memphis, one of the poorest zip codes in the city, and have involved the neighborhood. They have defined what needs to happen in the neighborhood, in partnerships with corporations, with government, with agencies that are not even here, like the Annie Casey Foundation, and they have worked with the partners in that community and have made a substantial change.

They made a goal in 2015 to reduce poverty by five percentage points in five years. They did research with the high school children and middle school children to say, what are the problems that are getting in the way? Then they took three of those problems and focused interventions around them. They have gotten children more involved. They created after school programs. They enrolled more children in kindergarten. If you are not reading on grade level by about the fourth grade, that is a predictor of ending up in jail, and so beginning to change those things very early on is huge.

They have already had an impact on the average income of the families that they serve. For a family that makes 8500 dollars a year, they have more than doubled that already. It takes all of these people working in this area, but it is an example that it is doable. It is doable, but it takes all of us. When we get people out of poverty, they can pay taxes. If we want a really fine country, we need to move everybody along.

Crowell-Williamson: Can you speak more about how environments and broader social structures can create stress, depression, anxiety, other difficulties, but also ameliorate them, and what the APA or other such organizations can do to address environments?

Phillips Davis: There are so many things. When you talk about what larger organizations or larger industries do to impact environments, well, we know that coal was a great industry. I mean, it still is, and yet the environmental impact, and the impact on the health of individuals, we know that it is there.

We know that immigration policies affect large numbers of people. We know that the way that we manufacture plastic, and the fact that we all use it is madness. There is an industry that has a horrible impact on the world that we live in. All fast food places use all that plastic, and so many poor people eat from those places and work at those places. So you can really begin to see it and see how challenging and multi-layered it is and what it will take for all of us to make the change.

So what APA can do is highlight it. We have an advocacy area, and we just got done with some sponsors in the House of Representatives for a resolution on Deep Poverty. It is important because Congress is beginning to say that it will pay attention to a problem in this society. That can be the beginning of saying that we will do something about it. So APA, just lobbying to get a resolution in Congress on deep poverty, says that we began to take a tiny step toward making Congress pay attention to something like deep poverty.

We have also had some conversations earlier in the year with the Gates Foundation because the Gates are very committed to work on poverty. Earlier in the year, back in March, when we created a national conversation on deep poverty, we brought the League of Cities and other people together to be able to have a conversation on deep poverty. It’s just bringing together our ability to assemble people and convene people and to have people in touch with each other. This is on a national level.

Within the divisions of APA, we are working on just asking them to pay attention to poverty and to do work in that area. Some people have projects like working on the transition from prisons, and working with families, just doing whatever we can do. So from systemic things to individual kinds of interventions, that is the work people are doing.

I was talking to the Kentucky Psychological Association back in November, and one of the psychologists and his church come down every Sunday and feed the people who are poor under a bridge. What he discovered is that he could get a bucket of water and a mop, and go down and clean off the place for them to sit outside and eat. Now he has other people joining him and doing that. So from the very broad things like sticking with the Gates Foundation and getting the resolutions to Congress, to an individual psychologist helping poor homeless people have a clean place to eat at least one meal in a day, it’s going to take all of us.

Crowell-Williamson: I have heard the argument that the pathologization of the poor reinforces stigma while deterring advocacy and public policy. So do you think there’s any risk in sort of the medicalization or pathologization of the poor?

Phillips Davis: When we say, ‘the poor,’ I will say ‘people who are poor.’ Changing the language of poverty, because anybody can be poor and any of us can help people who are poor. There are problems with people who are poor — they suffer. But it is the system that contributes to their poverty.

I’ll give you an example that’s also from our life. I can tell you that probably 20 years ago, maybe more, my husband got a call from his daughter, who was 35. She was poor and had five children. She called him standing outside an emergency room at a hospital in Florida, crying because she’d been to the emergency room, and they were sending her home. She was in such pain. He made her go back in (he is a physician assistant), and he called them and insisted that they put her back in the hospital. They called him back later and said, “We’re sorry, Mr. Davis, she’s going to need a heart transplant.” She was dead in two weeks because she was poor.

So the pathology was not in her; the pathology was in the system. That is what I mean, I say, ‘people who are poor,’ not ‘poor people,’ and not group people into a label like that. Because what we need to understand is that it is our system — the system is pathological, not the people.

Crowell-Williamson: We know that mental health diagnoses often reveal a racial bias: studies have shown that black men and women are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than white men and women, even when they show same symptomology, and in a similar vein, young black males are more readily given diagnoses of ADHD or conduct disorder. So what do you think can be done about this? How big a problem is it in the world of psychology?

Phillips Davis: You know, I haven’t studied how big of a problem it is; I just know that it is. I know that it is, and it’s incumbent on people like me, and any of us who are educators, to really lift it up, just like you’re doing, and to teach people about it — not only the people who are psychologists but the people who are just in the world.

I’m reading an interesting book called How to be an Antiracist. It is an excellent book because the author does not really group people by race or economic class. When you talk about racism and anti-racism, he talks about you’re either racist or anti-racist, and he talks about policies, the policies that promote racism, or the policies that promote anti-racism. What we have to do is be people who promote anti-racism and anti-racist policies.

Psychology is no different than anything else in the United States — it was founded in racism too. So we have to teach anti-racist policies in psychology, and we have to be very deliberate about that.

We have a campaign in APA called Don’t Skip Class. It was aimed at helping educators and researchers to understand that you must look at class when you are researching or teaching. Psychologists aren’t different just because they became psychologists. One of the things I noticed is that psychologists do not see poor people unless they work at an agency that sees poor people. They’re trying to make a living too, so they won’t see people who can’t afford to pay them. So I had a session at the APA convention on how you can have a practice and see poor people. We have to learn and have to be taught and have to be challenged just like any other group of people. No matter your race, color, which class you’re in; but those people who become educated and aware, it is our job to then be committed to helping educate. Education can come from anybody. It’s not the degree that determines it; it is sometimes what we call cultural humility and willingness to serve.

I have to be committed to learning every day. I hope the people who listen to this will be committed to learning every day. To be open to being challenged every day. We have to be open to reading things and open to reading new books and learning from all kinds of people. So, anyway, yeah, it’s a problem. But, even just the knowledge that it is a problem can help. So when psychologists, counselors, hear your podcast, they will know that young black men are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and know that when the police stop them that they are more likely to go to jail.

I was fortunate to be in Minnesota at the beginning of the year at the Minnesota Psychological Association, where they had a session composed mostly of white individuals, and they were talking about the fear of black people. To have someone say that they were afraid, some black person will come and kill them for no reason at all. If we begin to know and understand that somebody has that as a fear, then we know that that fear is going to translate into being more likely to arrest some young black person or kill some young black person because the fear is there, which goes right back to the beginning when I suggested that the brain is the survival organ. All we want to do is survive, so we group in ways that allow us to survive. People with political advantage cater to the fear of our not surviving. It helps us to create ‘us vs. them’ and makes it easier to fight against them. Sometimes it is merely about our own political and material gain.

Crowell-Williamson: The DSM and the disease model puts psychiatric difficulties within the brain of the individual, and views the individual as in need of fixing. So I’m wondering, first of all, if you see that conception as problematic, especially given these biased diagnoses we were discussing, and second, does it make sense to conceive of mental health challenges as being internal to individuals, or does it make sense to think about fixing environments perhaps?

Phillips Davis: My guess is that you have to do both of those things. One of the things we aren’t good at in the psychological world and the physical health world is clearly understanding that the mind and the body are one thing.

The brain that tells you you’re hurt when you are cut is the same brain that tells you you’re hurt when you’re depressed. We do not understand that. I can have something that is internal to me. For example, we have so many trees in Memphis, and because of that, I have a sinus issue. Well, that’s the environment outside me, leading to what is happening inside of me. It’s also affecting my disposition. I’m going to be maybe not as happy as I would be and maybe be a little bit down. So I don’t know how to separate things into either this or that when it comes to mind, body, and environment. I don’t know how to separate that. I think our fallacy is underestimating how much these things interact, and we totally underestimate that the mind and body are one thing.

Crowell-Williamson: Just one final question. We are in an era where poverty has been pathologized, and it has been medicalized. Can you imagine what it would be like to grow up poor at a time like this? Can you discuss perhaps what sort of impact you think it has on kids today?

Phillips Davis: Kids grow up poor like this all the time, and some of them are doing great things. I think in the Bible, it says that ‘the poor we will have with us always,’ it is just everyone does not have to be poor their whole lives. It’s okay to be poor. It’s just that, please, allow people the opportunity to do something other than be poor. There’s no crime in being poor, that’s okay. That’s okay, and you can learn a lot of things being a poor kid. It’s just that you’re not to be condemned to it and sentenced to it your entire life.

“I think in the Bible, it says that ‘the poor we will have with us always,’ it is just everyone does not have to be poor their whole lives”.

Everyone doesn’t have to be poor all the time? Very insightful … i’m wondering who she is referring to when saying “everyone”? Is there a “we” and a “them”?

Report comment

In the words of Desmond Tutu, neo_lib, it would appear that Ms Phillips – Davis has slowed the gravy train down long enough to get on

Report comment

If the intent of this interview was to write a biography of Ms Davis life, well, it was interesting.

If the intent was to discuss the causes and solutions to poverty, I’m afraid the substance was missing. Disappointing.

Report comment

I personally thought this was quite enlightening for anyone looking at the gap between what supporters of the DSM approach say and what is really true. I don’t expect an interview with the APA head to get into Marxist analysis, I expect it to report accurately what the APA head has to say. This can be VERY important in laying out a counterattack, as once a person is on record making specific statements, it is a lot easier to counter their position with factual research and descriptions of real events. I don’t see it as supporting the idea of “mental illness” just because MIA interviews someone who believes in it. But maybe that’s just me.

Report comment

Yeah, I get that. And you’re right, the title WAS quite misleading to me as well! I kept waiting for the “solutions to poverty” part to come up, but it never did. I just attributed it to the source. As the Buddhists say, misery is caused by the expectation that things will be different than they actually are. (or words to that effect).

Report comment

“This can be VERY important in laying out a counterattack, as once a person is on record making specific statements, it is a lot easier to counter their position with factual research and descriptions of real events.”

I agree, so let’s attempt to do this.

“Most of the psychologists I know, probably all that I know, came into psychology to do good.” I don’t doubt that’s true, however, is that what they’ve actually accomplished? I know that’s the opposite of what both the psychologists that were sicked upon me did. But that’s because both those psychologists had as a goal, covering up the abuse of my child for the ELCA religion, and covering up a “bad fix” on a broken bone, for a paranoid of malpractice suit PCP.

“We were not involved in that airplane that crashed into a building, killing thousands.” That’s untrue, according to my medical records, since a Lutheran psychologist believed my distress caused by 9.11.2001, in 2001, was “distress caused by a chemical imbalance” in my brain alone. An insane DSM based psychological/psychiatric belief system, which that psychologist didn’t finally confess to me she believed, until I picked up her medical records in 2005. And, let’s be realistic, most of the psychologists and “mental health’ workers did go off believing in the debunked psychiatric “chemical imbalance theory of mental health” long ago, at least in practice.

“I think we ought to declare poverty as a public health problem.” I’m quite certain it’d be wiser to declare the insane, systemic greed and thievery of the “professional” and “elite” classes to be a public health problem.

“the system is pathological, not the people.” Definition of pathological, “Morbid, diseased, … compulsive, obsessive, inveterate, habitual, persistent, hardened, confirmed.” I agree, the entire, scientific fraud based, DSM system is all these things, but confirmed. Quite to the contrary, the DSM has been debunked as scientific fraud.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

So I’m wondering why the head of the APA isn’t yet speaking out against the debunked psychiatric DSM “bible,” and is still advocating for the defamation, drugging, and torture of innocent people, via these debunked DSM “disorders?”

“Psychology is no different than anything else in the United States – it was founded in racism too. So we have to teach anti-racist policies in psychology, and we have to be very deliberate about that.” But systemically stigmatizing people with “invalid” diseases is no better than racism, which is what the psychological industry has been doing for about a century.

“Psychologists aren’t different just because they became psychologists. One of the things I noticed is that psychologists do not see poor people unless they work at an agency that sees poor people. They’re trying to make a living too, so they won’t see people who can’t afford to pay them.” But this also means the psychologists have been targeting the well insured middle and upper middle class people. Whose insurance would pay for your medically unnecessary, defamation and torture of innocent humans, with your make believe DSM “disorders” and neurotoxic psychiatric drugs.

“Education can come from anybody. It’s not the degree that determines it; it is sometimes what we call cultural humility and willingness to serve.” Unfortunately, the majority of psychologists and psychiatrists are seemingly not intelligent to understand this, nor do they take the time to listen to, or even bother to believe, their clients. Trust me, I have medical proof of this in my medical records.

“I have to be committed to learning every day.” We all should be learning every day.

“So, anyway, yeah, it’s a problem.” Yes, systemic racism within the psychological industries is a huge problem. But so is their systemic stigmatization/defamation of all people, of all colors, with their “invalid” DSM “disorders.” There’s not much difference between racism and stigmatization with “invalid” “disorders.” Both are about keeping or pushing others down.

And, as one who works with underprivileged, mostly black children, I am actively forewarning those who also work with these children about the systemic harms of the psychiatric drugs. Drugs which the psychologists are still systemically promoting, and forcing onto innocent others.

But since Phillips Davis would like to learn. Perhaps she should learn that the ADHD drugs and antidepressants can create the “bipolar” symptoms, and over a million American children – and no doubt, millions more adults – have already had the adverse effects of these drug classes misdiagnosed as “bipolar.”

https://www.alternet.org/2010/04/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america/

And, in much as these systemic misdiagnoses were pointed out to be massive societal malpractice, even according to the DSM-IV-TR:

“Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.”

Rather than the psychiatrists adding the ADHD drugs to this disclaimer in their DSM5, the psychiatrists totally took this disclaimer out of the DSM5. So the psychologists, and all the other “mental health” and social workers, could continue to commit even more malpractice, supposedly out of ignorance, for the psychiatrists.

And, just an FYI, the antipsychotics/neuroleptics, that are given to all those “bipolar” misdiagnosed children and people, can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. And the antipsychotics can also create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” like psychosis and hallucinations, via anticholinergic toxidrome, too.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But since the psychiatrists did not include these medically known syndrome/toxidrome in the DSM, the psychologists and all other “mental health” and social workers claim ignorance of the common adverse effects of the psychiatric drugs.

Thus the psychologists are systemically aiding and abetting in harming, and killing millions, on a massive societal scale every year. As a matter of fact, they are medically unnecessarily helping the psychiatrists to murder 8 million people a year, based upon the “invalid” DSM “mental illnesses,” according to the former head of NIMH.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mortality-and-mental-disorders.shtml

“So when psychologists, counselors, hear your podcast, they will know that young black men are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and know that when the police stop them that they are more likely to go to jail.” True, but the crimes of psychology and psychiatry are not merely racist crimes. And I am personally warning the black community of the psychiatric drug induced, iatrogenic etiology of “bipolar” and “schizophrenia.” But I don’t hear the head of the APA doing the same.

I was fortunate to be in Minnesota at the beginning of the year at the Minnesota Psychological Association, where they had a session composed mostly of white individuals, and they were talking about the fear of black people. To have someone say that they were afraid, some black person will come and kill them for no reason at all. If we begin to know and understand that somebody has that as a fear…”

I don’t personally know of anyone but psychologists, as you admit, who have those fears. But, as I mentioned, I work to help underprivileged children, many of whom are black. Which I have noticed has helped teach the black children I work with that white people are nice, and want to help them, rather than promoting a “divide and conquer” theology.

“People with political advantage cater to the fear of our not surviving. It helps us to create ‘us vs. them’ and makes it easier to fight against them. Sometimes it is merely about our own political and material gain.”

Yes, the psychological and psychiatric industries are industries with “political advantage,” that do fear and disease monger, create an ‘us vs. them’ mentality, promote a divide and conquer strategy, to make it easier for the “elite” and “professional” classes to “fight against” the rest of the public. And I agree, the psychologists largely “merely” care “about our own political and material gain.”

“The DSM and the disease model puts psychiatric difficulties within the brain of the individual, and views the individual as in need of fixing. So I’m wondering, first of all, if you see that conception as problematic, especially given these biased diagnoses we were discussing, and second, does it make sense to conceive of mental health challenges as being internal to individuals, or does it make sense to think about fixing environments perhaps?”

“Phillips Davis: My guess is that you have to do both of those things. One of the things we aren’t good at in the psychological world and the physical health world is clearly understanding that the mind and the body are one thing … ”

I think Phillips Davis totally ignored the fact that the DSM diagnoses are “invalid,” which is a problematic belief system, or “lacking in insight” issue, for the head of the APA in 2020.

“We are in an era where poverty has been pathologized, and it has been medicalized. Can you imagine what it would be like to grow up poor at a time like this? Can you discuss perhaps what sort of impact you think it has on kids today?”

“Kids grow up poor like this all the time, and some of them are doing great things.” I think Phillips Davis again ignored the question, and is merely referring to her own success, as being the head of the APA. And she goes on to discuss her own “success” more.

“I think in the Bible, it says that ‘the poor we will have with us always,’ it is just everyone does not have to be poor their whole lives. It’s okay to be poor. It’s just that, please, allow people the opportunity to do something other than be poor. There’s no crime in being poor, that’s okay. That’s okay, and you can learn a lot of things being a poor kid. It’s just that you’re not to be condemned to it and sentenced to it your entire life.”

As one who recently had a psychologist attempt to steal all profits from my work, my work, my story, and my money, with a BS “art manager” contract, because my work was “too truthful” for a Lutheran psychologist. I agree it is wrong to attempt to condemn others to be poor, especially via attempted thievery, or psychological/psychiatric defamation and neurotoxic poisoning.

I have no doubt, now that the truth about the scientific fraud and the historic, and continuing, systemic child abuse covering up crimes of our psychological and psychiatric industries are starting to come to light.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

That white men would prefer to have a black woman, who apparently knows very little about what’s actually going on in her field, to be in charge of the American Psychological Association.

I hope Phillips Davis will wake up, and garner some insight into what is actually the historic and continuing, primary actual societal function of your industry, which is covering up child abuse and rape. Albeit, systemic racism is also a problem of our psychologists and psychiatrists. And I also hope she wakes up to the fact that her DSM “bible” is a book of “invalid” stigmatizations, and defaming people with those stigmatizations is no better than racism. But poisoning people with the neurotoxic psychiatry drugs, especially after first and foremost promising to “do no harm,” is more evil than racism. It’s attempted murder, and complete hypocrisy.

Pardon my frank, hopefully constructive, criticism. But this interview does help shed light on why the British psychologists are speaking out against the systemic harms that are being done by the psychiatric industry. Whereas the American psychologists, and the APA, are not.

Wake up American psychologists, and please get out of the child abuse covering up business, as well as, stop being racists. But your systemic child abuse covering up, which also functions to aid, abet, and empower the child molesters and child sex traffickers, is destroying our country, even according to the ethical within your industry, and world leaders.

https://www.amazon.com/Pedophilia-Empire-Chapter-Introduction-Disorder-ebook/dp/B0773QHGPT

https://community.healthimpactnews.com/topic/4576/america-1-in-child-sex-trafficking-and-pedophilia-cps-and-foster-care-are-the-pipelines

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/us/backpage-sex-trafficking.html

https://worldtruth.tv/putin-the-west-is-controlled-by-satanic-pedophiles/

Stop systemically covering up child abuse and rape, psychologists, please.

Report comment

“Most of the psychologists I know, probably all that I know, came into psychology to do good.”

Most of the bank robbers I know went into the industry to do good too, as long as you don’t start defining how they’re doing good and for whom it all seems fine.

I also noticed the “bad apple” reasoning behind the ‘colleagues’ who designed a torture program for Guantanamo. Not that their ideas will be picked up by others and used with evil intent. So what has been done to ensure this doesn’t happen? Nothing? This is of course how people are lead astray, like the Community Nurse who finds it easier to use known torture methods to obtain referrals knowing that the authorities will conceal his criminal conduct for him to maintain reputation. Thus normalising the conduct and well before you know it, it will be your door he is knocking on as a result of your ‘deviance’ from the psychiatric dogma.

Good comment Someone Else and whilst I know from experience these sychophants do not respond to questions from the people being oppressed by their ‘doing good’, at some point they will be on their knees begging for mercy which will come in the form of fire.

Report comment

Thank you, and I agree, boans. There may end up being a ‘lake of fire’ problem for the intentional ignoramuses and hypocrites.

Report comment

Well done Someone Else and boans, despite the fact that your necessary critiques merely scratched the surface of the contradictions, illogical fallacies and utter — in this article.

I spent the last few hours ripping it apart and look at the Gates Foundation.

There are no words for how dismal, misleading and troubling this article is.

Outside the few honest articles, the point of reading MIA is completely lost on me.

Report comment

Share your critique, please, judi. I agree, my quick critique merely scratches the surface. My hope was to attempt to start waking up the head of the APA. In the hope she might start doing some research, travel down the rabbit hole that we here have already done, so she can start to garner insight into what is actually going on in her field. And, of course, help her garner some insight into the systemic, iatrogenic harm being done by her, also primarily child abuse and rape covering up by DSM design, psychiatric partners in crime. Please share your critique, judi.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Report comment

How do you like the phrase and the news at the same time that *Long-Term Antipsychotic Use Linked With Lower Mortality Rates? Imagine dentists would say that long-term drilling of teeth reduces the risk of developing periodontal disease. Some may perceive such information literally. And for example, chemically treat acute psychosis not 3 but 60 days.

Report comment

eventually one would have less teeth, and less brain?

Report comment

I thought this article would be about the link between “mental health” and disability related poverty which RW touched on in his Anatomy of an Epidemic. Mildly disappointed.

I’m happy for Ms. Davis btw.

Like many here I didn’t grow up poor. All those wonderful “treatments” sentenced us to lives of poverty. 3 years off my cocktail I can finally clean my room again after 20 years. Thanks for the systemic damage “mental health.”

I hope and pray I can earn enough with online gigs to save myself from homelessness soon. My parents are frail and elderly. They may have to sell the house soon.

I can’t drive due to neuroleptic seizures that prevented my drivers license when young. Never had a family of my own. Almost no friends. In horrible pain every day with symptoms like Crohns and Lyme Disease that seem to baffle doctors.

They get very mysterious and won’t venture guesses on the causes of the disorders they diagnose. My CNS, GI, and executive function are wrecked from long term druggings.

Very angry. I weep inconsolably almost every night holding my cat–mourning the life psychiatrists stole from me.

If you don’t want to wind up sick, lonely and poor stay far away from shrinks!!!

Report comment

Rachel, I hope you know how many of us here love and value you! Psychiatry stole my life as well and has left me dependent on others too. It’s hard, but we have to keep fighting back and being seen and heard. I’m writing this while my heart is skipping beats – such a scary feeling. Hang in there, sweetie!

Report comment

Hugs!

Report comment

Rachel,

Sometimes people go to these analysts hoping that they can ‘help’. We are often blamed for having gone, yet does the analyst not propose that he can ‘help’?

He can help alright, help people to get onto disability, because the person the ‘disordered parts’ that he sees, are a disability.

Since he blindly thinks that the parts he sees are the person, you become wholly disabled.

It is like going to a doc with a sick heart, or cancer and every part of the body is listed as disabled.

The mind is the vastest least understood, the very problems we go to analysts with, could be our greatest strengths, in some manner that no one has discovered.

We do not know anything, yet keep professing to know shit.

It is the frustration of having such a vile practice, which most know is a sham, even the shamsters don’t buy it, yet is allowed to wreck havoc.

It is the frustration of what happened, keeps happening, where we have no control to change it, that causes tears of grief.

The only reason shrinks are not bothered by this is that they are also born with or developed certain neural pathways, those of apathy to suffering, and dissociation.

I lived for so long being bothered and thinking that the opposite was mental health and resilience.

I studied this resilience for a LONG time and in a lot of cases, it can be called something quite different.

So yes, I would love to have that resilience, yet I did not get it.

This lack of resilience has made me fall and others rise.

We have yet to determine that this “lack of resilience” is in fact “mental illness”.

When we look at crazy chaotic history, the non resilient have not caused much damage, yet have served the advancement of society quite well.

One would think it’s time to hail the multitude of personas no matter their uniqueness.

Psychiatry is really no longer needed, it is a destructive force. If the UN and the WHO would actually enforce equality in healthcare, psychiatry could not possibly exist in it’s present paradigm.

They are simply allowed to exist because no one has an answer to the mess that was created.

So on one hand, we realize the mess, they realize it, but SOMEONE, some are NOT doing, just suggesting.

It is SO big, that they are looking at the height of the peak, and not at the bottom. It was at the bottom it started, but looking at the peak, it seems unsurmountable.

The dismantling has to start, in order for anything to change.

If we took away the DSM, no one gets a diagnosis, but the shrink can easily say that “Mrs Doe is not able to work at the moment due to personal problems”. We can even name it “problems in focus”, “feeling sad”,

These describing terms are reality.

We can honestly say that “it could be Mrs Doe’s view of the world, her outlook, her possible theoretical neural pathways”.

But it is NUTS to call these things anything like the “diagnosis”.

And even if every single chemical and process was EVER scientifically realized, or have a sort of half azzed reverse explanation in place, someone STILL has to say that WHAT he sees, is a “mental illness”.

And how logically this MI, prohibits anyone so labeled to human freedoms.

The pretense that those labeled MI, get medical care will always exist.

Because in fact, the ER or doctors WILL see those wretched cretins, BUT they will NEVER admit to not only looking at them in the funny manner, but whispering and not attending to quite with the same urgency. In fact, being labeled only ever gets you NOT validated.

This is fundamental damage.

The scope of it, makes people sad and grieve, and that grief is no fucking MI.

It is their garbage we look at.

Report comment

This was interesting for me. What it tells me most is, it doesn’t really matter where your heart is; most people just don’t have a clue. It seems studying Psychology really doesn’t help that much in that direction, either. I’m an electronics technician whose parents studied to be social workers. I wasn’t happy with what my college-educated parents had to offer me in terms of understanding life, so I went out and studied all sorts of subjects from all sorts of sources instead of going to college. I consider myself very lucky to have made any progress at all in the direction of getting a clue. I found a subject which could be considered a humanities subject that actually seems to help people consistently. And this is a very unusual thing, as subjects like psychology, economics, history and business management don’t seem to be designed to help anyone. They only end up helping when the people involved really want to help. Those guys will pick out the parts of their subject that seem most helpful, and come up with a helpful subject.

I also feel very fortunate to have studied science, technology and engineering. Because in those fields, if a technology doesn’t work, it is discarded. The humanities have never been run that way.

I don’t think we should put this beautiful black woman down for trying to make things work. Because most of us don’t have a clue, either. The only reason my life includes any hope or happiness is because I know it is possible to get a clue. Who knows, it could happen to you, too!

Report comment

It seems one should only feel sorry for “analysts of the mind”. Psychiatry does indeed practice analyses, and deems emotions and reaction as something to throw away, based on the theory that IF the emotion and reaction is causing ‘disfunction’, stress, or inability to function, it has then lost all logical benefit.

The problem being of course, that we have to identify what function looks like.

If it pertains to earning a living and no shit disturbing and getting a nights sleep, despite dogs whimpering out in the cold, and ability to not go into being bothered by the sound, then a lot of us will fail.

So really, it is so very easy to be an analyst, one wonders why ANYONE would need 8 years of school to be able to determine “function”.

The very best thing you can tell a non function person is to tell them that they are sick. All labels could say “you are sick in mind”

This kind of analyses leads to hope, feeling normal.

The best thing that ever happened to those fringe people that felt apart from a lot of society is to give them a job that elated them. That job was called a “psychiatrist”, when all it ever was, was judgment and power to make it stick. It fell in line perfectly with gossiping neighbours and you know, the shit people talk about.

Listen to most people’s convos. It’s about others.

Report comment

I have nothing against Ms. Davis personally.

Most of us here only want one thing from “mental health.” To be left alone!

Their “services” lower self image, teach helplessness, prevent gainful employment and isolate from the community. Their treatments cause physical and mental disabilities.

It makes sense that the Mental Illness System is targeting POC. (Watch Breggin’s videos on the Violence Initiative.) Many minority communities are distrustful of Mental Centers.

An African American friend of mine commented on how many white women she works with pop psych pills all the time, talking about their “bipolar” and “chronic depression.” It looks like so many have these labels they can actually find work now–as long as their CNS and brains hold out.

“Mental health” creates poverty. Lots of us grew up middle or upper middle class and are forced to subsist on $775 a month thanks to psychiatry’s “help.”

Almost three years off my drugs and finally found a job. For the first time as an adult. (I went on psych drugs at 18. “Therapeutic” amounts at 20 after getting labeled.)

Can’t wait to go off my “benefits.” I HATED going on them. Never wanted to be a bum.

Psychiatry forced me to. They lied to me–saying my only hope for gainful employment was unquestioning obedience/”med” compliance. Basically shrinks forced me to violate my conscience by tricking me into going on mind altering drugs (against my principles) and mooch off the public.

I kept asking, “Hey, if these treatments ‘work’ how come we can’t get jobs and act like freaking grown ups?” These questions would throw the idiots leading day treatment sessions into fits of rage. (Not all case workers acted that way. The idiots were those who threw tantrums at my innocent questions.)

But “work” doesn’t mean independence, health, or productivity to shrinks. It’s all about docility and childish dependence.

The welfare workers make you feel like a piece of trash at those bureaucratic offices. Far more dehumanizing and humiliating than hand outs from locally run charities.

Report comment

Rachel,

There is a lot of anger in the MI treatment area, including the shrinks.

I think the anger is about the deep pit they dug, and direct their anger at the very “objects” that keep them in biz.

Although I still believe they went into the deal because of stuff they suppress.

I visited a MI site where one member mentioned that he had asked his shrink if he was familiar with the term “gaslighting”, to which the shrink seemed completely unaware and so the shrink asks his colleague and the colleague also denies ever having heard the word.

The poster was making a point, yet the MI members basically told him that “gaslighting” was a conspiracy thinking word.

Until someone came along and posted an article where a shrink used the term, which ended the discussion.

Um yes, they know the term well, they used to do it in school I bet.

They also know the term “baiting”.

Report comment

The “deep pit”? Do you mean being found out eventually?

Their big mistake was targeting too many people. If they had been content with just a modest number of “lunatics” in their asylums without walls they would have gotten away with it indefinitely.

But by drugging over 20% of the population for decades, it’s impossible to ignore the long term results of the pills they hand out like office mints. Ruining the lives of 2-5% of the populace wasn’t good enough for them.

Now the cat is clawing it’s way out of the bag.

Report comment

Something I wonder about the movie Gaslight.

(Spoiler Alert) It seemed to me that the gas light brightening and dimming was not done by Charles Boyer as a deliberate ploy to drive his wife insane. It was an unintended consequence of his overall plot to drive her mad. If that’s the case it’s interesting to me that all one needs to do is set the cycle in motion and it gathers speed of its own accord.

For example, the removal of the documents proving I was ‘spiked’ with benzos, and the use of my claim that I had been spiked as being a delusion I was suffering from (It’s a common delusion among ‘mental patients’ that they are being drugged without their knowledge, in fact THE most common delusion). The truth becomes a weapon as a result of the fraud by the hospital Operations Manager. Clever when you think about it. Exquisitly poisonous was how I described it to the Chief Psychiatrist. Of course he was in with the gaslighters so probably didn’t appreciate exactly how poisonous such conduct can be. These people have a tendency to justify their vile conduct in their own delusional way.

The good news is it is fairly easy to recognise someone who is being gaslighted, and then move in on the perpetrator who is usually a psychopath who thinks they are much cleverer than they are. (What’s up Doc? And you went in to medicine to save lives huh? Oh well, someone with the stomach for it gotta do it I guess. And you got the short straw so to speak)

Report comment

Whenever I see “APA”, I always have to wonder whether they mean “Psycological/Psychology” or “Psychiatric/Psychiatry”….I think BOTH professional organizations revel in the confusion, because NEITHER seems at all willing to address the confusion, much less do something about it. I can see some validity in psychology, but NONE in psychiatry. Psychiatry is a pseudoscience, a drug racket, and a means of social control. It’s 21st Century Phrenology with potent neuro-toxins. Psychiatry has done, and continues to do, far more harm than good. And sadly, psychology is not far behind as a divisive and destructive force in society. The DSM is a catalog of billing codes, and sadly, the AP(psychology)A is almost as dependent on it as psychiatrists are. Therefore, although I’m sure Rosie Philips Davis considers herself a good person, who does good for society and helps people, I don’t see her that way. By blindly accepting the EVIL of psychiatry and the DSM, she perpetuates that evil. I just kinda shake my head sadly, and roll my eyes at her and her ilk. But at least she doesn’t pretend to be a person of non-color….so that’s something good, I guess….

Report comment

You actually make a good point here. But I am concerned about how many people are clueless about all this, even people in these professions. They have no right to be clueless, but I can see how it could happen.

While this lady could be seen as an accomplice to those who kill with pills, ECT and other “treatments,” I would prefer to keep the focus on those directly responsible for those deaths. I figure if we can keep the pressure on, people who speak in public about such things will eventually get the point that supporting these people is untenable.

Report comment

Ms. Davis is innocent and means well.

This piece reads like it belongs in another publication. But this is not meant to be an anti-psychiatry site after all.

I wouldn’t call this piece “critical” either. But helping people in poverty is a good thing. I agree with that.

I just don’t like how psychiatry does it. Way worse than ineffective. And kindly people (psychologists, therapists, peer support workers, case managers) who team up with psychiatrists burn out quickly if they are trying to make a difference.

It’s like trying to bale out a leaky boat while the quacks keep drilling more holes in the bottom. The epitome of futility.

Report comment

I love the leaky boat analogy Rachel777. Just when you think your getting ahead, they call for a bigger drill bit. Oh well, the Captain goes down with the Ship (glad that typo didn’t slip past me lol)

Report comment