Dear VA Secretary Robert Wilkie:

I am writing you this public letter to ask for your help. I’m working to decrease daily veteran suicides by 25% to 50%, from 20 a day to 10-to-15 per day. This goal is achievable. It accepts that we cannot stop every suicide but, if we can reduce the suicide numbers to this extent, we will at least be curbing the “epidemic” and demonstrating that we can develop suicide prevention programs that are effective.

Through my research and experiences, I’ve found that what the VA has been doing to fight this epidemic isn’t working and appears to be unintentionally exacerbating it. These problems are fixable.

I’ve been fortunate to have had experiences that allow me to look at the issue of veteran suicides from a unique perspective. During my tenure as the president of Student Veterans of America (SVA), which I founded in 2008, I spent a great deal of my energy addressing the mental health needs of veterans. This was motivated by the loss of student veterans to suicide.

In 2010, I graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in psychology. That year, I became a founding committee member of the National Action Alliance on Suicide Prevention. My first job after college was working for VA Central Office in the Office of Mental Health Services, now the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. At the VA, I was tasked with building a national mental health program for veterans on college and university campuses. After this, I served as a technology executive in New York City.

Previously, I served for twelve years in the United States Air Force and the Air National Guard. As an active-duty Airman, I was an aircraft electrician with the AC-130H Spectre Gunships, where I deployed once to Afghanistan and twice to Uzbekistan, beginning in 2001.

In addition to my military and professional experiences, for four years I was a patient treated by the VA’s mental health system, first at the Manhattan VA and then at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center. During this time, I was prescribed nine different medications, mostly psychiatric drugs, including as many as six at a time. In those four years of being prescribed multiple psychiatric drugs, I never had a session with a VA psychologist or counselor, even though I requested counseling on multiple occasions. I’ve since filed a complaint with the Office of Inspector General and am awaiting a response.

I also endured a painful year-long withdrawal from the antidepressant Zoloft. This was after I’d been on the drug for only a year. Antidepressant drug dependence was something I was not warned of before starting this treatment, nor was I adequately warned of the risks for violence or suicide. For nearly the entire time I was on this drug, I was a danger to myself and those around me.

Nearly all of the prescriptions I received were the result of a misdiagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). I was subsequently prescribed medications to treat the side effects of the stimulants I was prescribed for ADHD and the others that followed. This led to my being prescribed the Zoloft.

My withdrawal from Zoloft is detailed extensively in my article Ambushed by Antidepressant Withdrawal. My experiences with prescribing practices at the VA are described in Prescribing an Epidemic. It should be noted that I took no pleasure in writing these articles, as they describe in granular detail the worst years of my life. With that said, I feel compelled to continue writing.

Many other veterans also trusted the VA mental health system and have been left trapped on drug cocktails, just as I was. They too are losing years of their lives; that is, if they survive. I hope my stories might help them personally, and that they might inspire you to make changes within the Department.

Confirming a Hypothesis

Based on my own experiences, reflections, and two years of research, I developed a hypothesis:

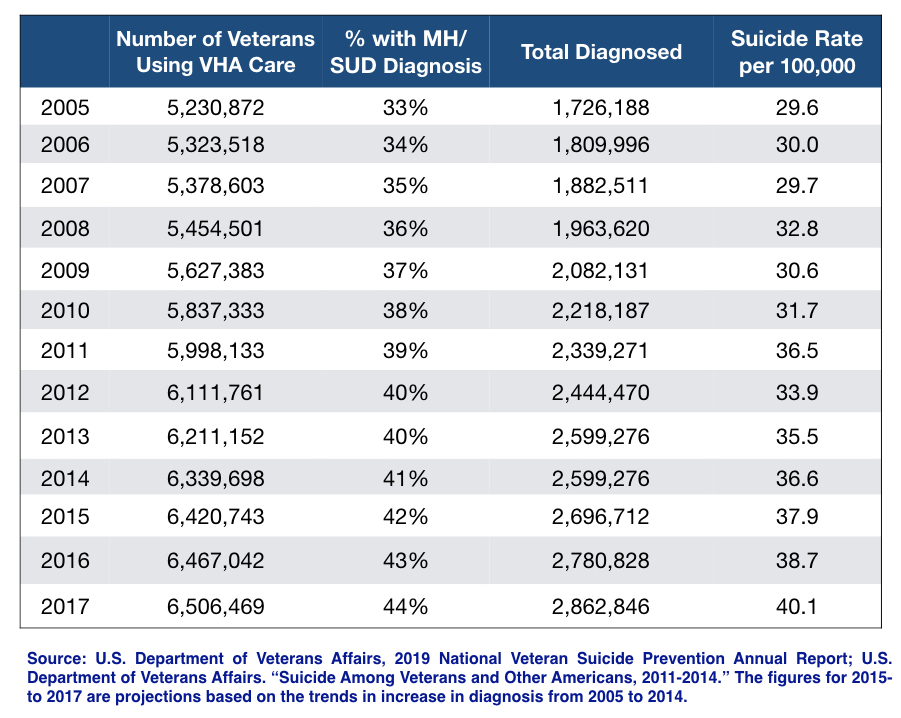

Veterans who use the VA for their care will have higher suicide rates because they have greater access to mental health care, specifically psychiatric care, than veterans who do not use the VA. Therefore, VA-using veterans will be disproportionately prescribed antidepressants, not because they are sicker, but because they are better screened and have better access to drug treatments, thereby increasing their risk for suicide.

This isn’t to say this problem is exclusive to the VA and DoD. Instead, it suggests that the VA has adopted and streamlined the “evidence-based” best practices deployed in the private sector. Therefore, the VA might be viewed as a case study of mental healthcare in America. It also suggests that the best way of assessing this problem should be through the lens of a forensic question and analysis: Did adopting these “best practices” fuel the veteran suicide epidemic at the VA?

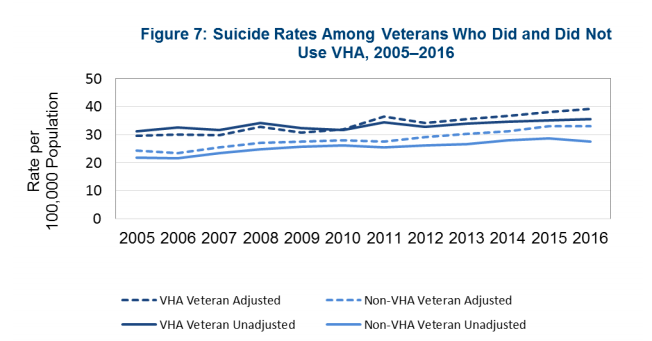

As I sought to prove my hypothesis, I first studied the VA’s 2018 National Suicide Data Report. In it, I found a chart that showed veterans who use the VA for their care have higher suicide rates than veterans who do not use the VA for their care. This began to confirm my hypothesis, but it ran counter to the report’s key takeaways and the VA’s public talking points, which state that veterans who recently accessed VA care are at a decreased risk for suicide.

This finding — that suicide rates are higher for veterans using VA care — was not featured in the report as warranting further investigation. Instead, the report stated:

“Veterans who use VHA have physical and mental health care needs and are actively seeking care because those conditions are causing disruption in their lives. Many of these conditions—such as mental health challenges, substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain—are associated with an increased risk for suicide.”

This paragraph explained that higher suicide rates at the VA were expected because these veterans are more broken.

The problem is that this is a theory the VA has been using to explain the higher suicide rates, and only a theory. This fact has been confirmed to me by individuals within this Department. While there is some research to support this theory, it does not fully explain the dramatically higher suicide rates for veterans at the VA.

In addition to this statement in the 2018 Suicide Data Report, another talking point says “that over two-thirds of veterans who died by suicide during the study period had not recently received care from the VA.” Unfortunately, this talking point merely says that in total there are more veteran suicides outside of the VA care than there are within. It is overly simplistic, as it ignores the fact that the number of veterans who get their medical care outside VA facilities is significantly more than than the number of VA-using veterans.

Additionally, the VA explains that the Department has made progress and, while suicide rates continue to increase at the VA, “rates for Veterans who did not receive care in the VHA increased faster than among VHA-using Veterans.” This outcome could be explained using the business term “market saturation.” Prescribing rates at the VA have gotten as high as they possibly can—they’ve prescribed drugs to as many veterans as they’ve been able to diagnose—whereas prescription rates of these drugs are still increasing for veterans outside of VA care.

These arguments effectively muted further public and Congressional inquiry.

Upon further study of the chart above, which compared suicide rates for VA-using veterans and non-VA using veterans, I found it difficult to differentiate the multiple lines in the chart from one another. The chart included “crude” suicide rates (the suicide rates for all veterans) and “age-adjusted” rates (which factors in older populations, who are known to have a higher suicide risk). It became clear that suicide rates for veterans who used the VA weren’t slightly higher but were significantly so.

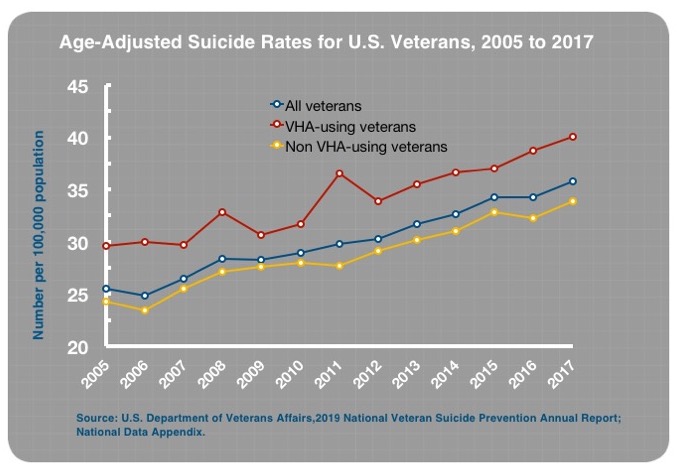

From there, I pulled the source data cited in the report’s appendix. When I compared the suicide rate data for the VA-using and non-VA-using veteran populations, I was stunned to find that suicide rates for VA-using veterans were 32% higher than for veterans not using the VA. This statistic was not found in the VA’s report, nor in any other publication. The story that the public, Congress, and many in VA leadership have been receiving is that the VA was doing better than everyone else in preventing veteran suicides. Yet, the VA’s own data showed the opposite.

Here is a clearer presentation of this data, updated through 2017.

When I first publicly reported the 32% higher suicide rate, I was questioned and attacked. The former director of the Veterans Benefits Agency (VBA), who was the fourth-most–senior-ranking VA official, posted: “These facts need to be reviewed for accuracy. The facts I have that are peer-reviewed are that a veteran under VA care is highly less likely to complete suicide than one who isn’t.”

A former senior leader of the VA’s office of public affairs (OPA) posted: “This appears to be inaccurate. Where did you get this information? Because if it is inaccurate, then you’re potentially endangering people by steering them away from VA treatment.”

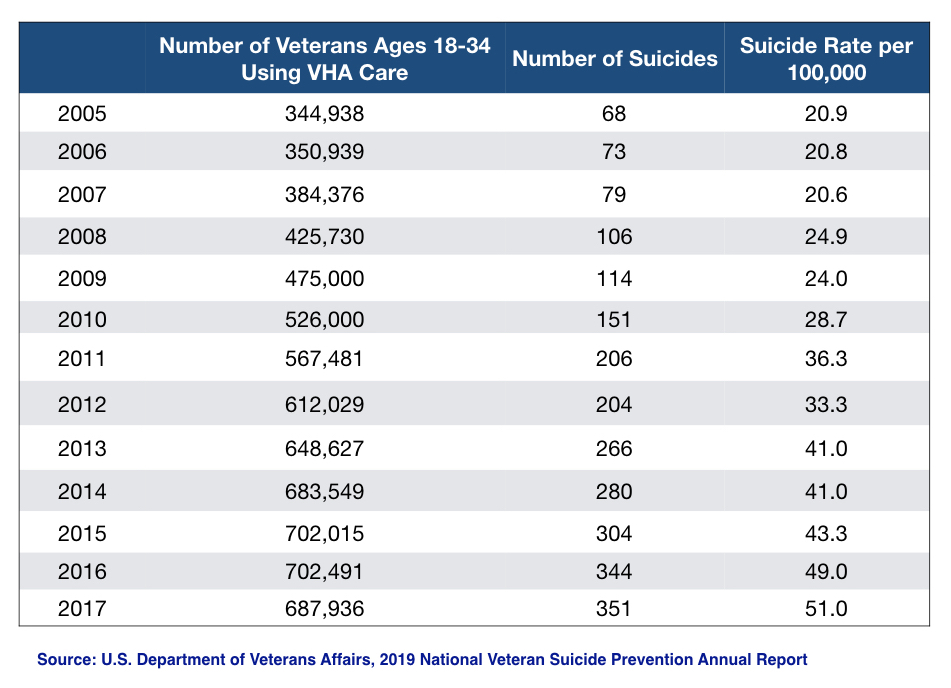

I received more of the same when I co-published a report with journalist Robert Whitaker, where we first reported a five-fold actual increase in suicides and a 144% increase in suicide rates for 18-to-34-year-old veterans who use the VA, compared with a 57% increase for veterans not using the VA for their care. These statistics were also developed from the report’s appendix data, this time from the VA’s latest 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. These statistics were not featured in the annual report either.

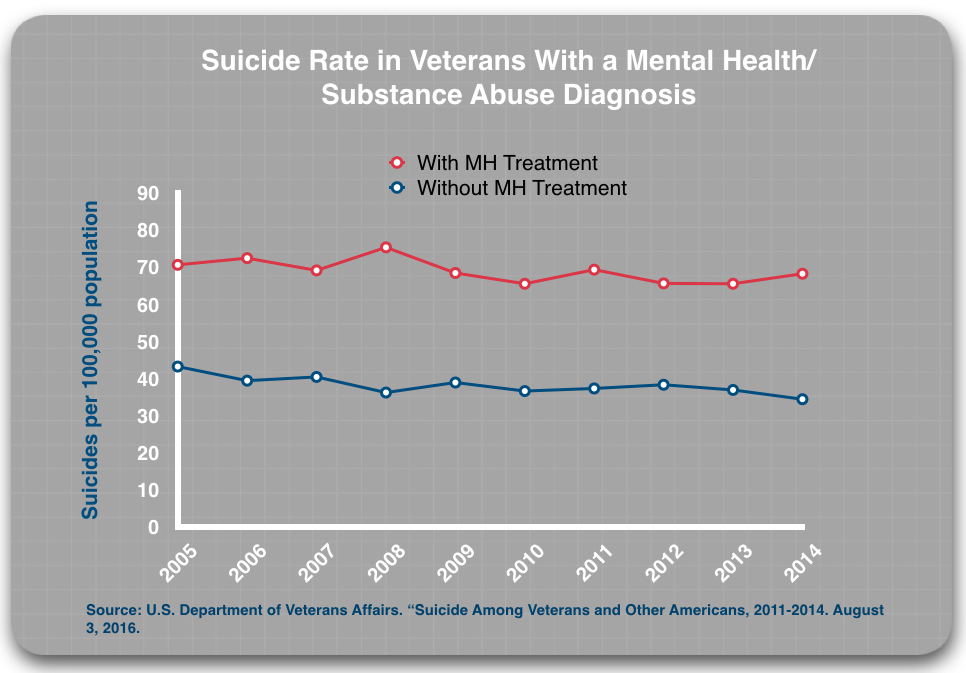

In the report Whitaker and I published, “Screening + Drug Treatment = Increase in Veteran Suicides”, we also showed that veterans diagnosed and treated at the VA had suicide rates double that of veterans at the VA who were also diagnosed, but went untreated.

When I shared these statistics with sitting members of the House and Senate, it was the first time they had heard them as well. From a sitting democratic member of Congress: “I knew it was bad, but I didn’t know it was that bad.”

The most concerning response, however, was an interaction I had with a VA Assistant Secretary. As we talked on our way out of an event in Washington, D.C. in December, I shared with him the 32% higher suicide rate and the 144% increase in suicides for 18-to-34-year-old veterans at the VA. He stopped in his tracks, stared me in the eyes and said:

“So you’re saying the VA is lying!”

I replied: “I’m not saying you are lying, or specific individuals in VA leadership are lying….”

He cut me off. “But you’re saying the VA is lying!”

“I’ve tried not to use that term,” I said.

The reason I found his response concerning is that he, an Assistant Secretary, is part of the Secretary’s inner circle of leadership. He is in a public position when he talks about veteran suicides. Yet, even he was unaware of the actual numbers. He said he was going to look into it, as this conflicted with the information he had been given.

Recognizing the Problem

If members of Congress sitting on the House and Senate Veterans Affairs Committees and the Executive Branch are unaware of the actual suicide statistics at the VA, we cannot expect to solve the suicide epidemic occurring among veterans, both those who are using VA treatment and those who are not.

Some members of Congress are now actively looking into the suicide rates at the VA and the role of antidepressants in causing them. Others are afraid to do so. Many Democrats are reticent to investigate, as they are concerned that Republicans and the White House will privatize the VA if the department is rocked with yet another scandal, especially of this magnitude.

Republicans fear this information could harm the President in an election year and are choosing not to pursue treatment-caused suicide deaths at the VA. This was directly confirmed to me by a sitting Republican Congressman.

My Plea to You, Secretary Wilkie

Secretary Wilkie, until now, I believe, this epidemic has not been caused by inaction, for the simple reason that the VA leadership has not had the right information. Therefore, you and the other VA leaders could not take the necessary action. But now the VA leadership has the data. As a result, the VA leadership and the Executive and Legislative branches of the U.S. government can investigate and act.

Many have made the argument that the public disclosure of the fact that suicide rates are dramatically higher among VA-using veterans might deter veterans from seeking mental health care from the VA. While this might be true, it is a matter of informed consent. If there is reason to worry that treatment at the VA increases the risk of suicide, veterans—like all patients—have the right to be fully and properly informed of that risk.

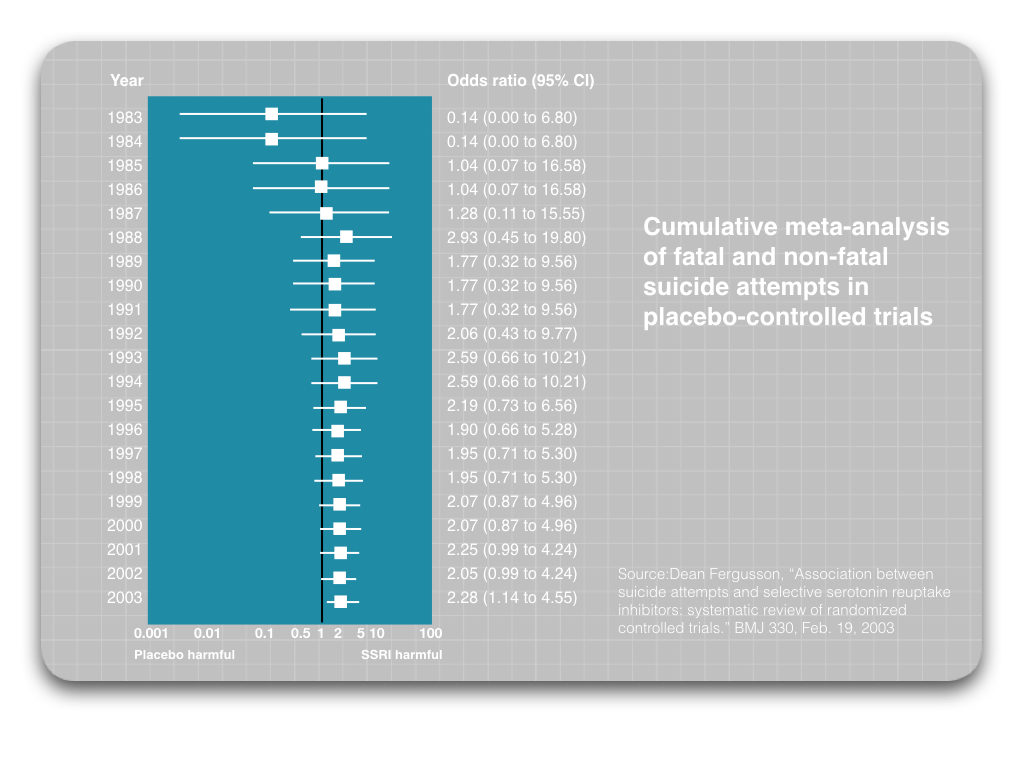

Exhaustive reviews of clinical trial data show that antidepressants double the suicide risk. Please examine this chart detailing the increased risk of suicide with these drugs:

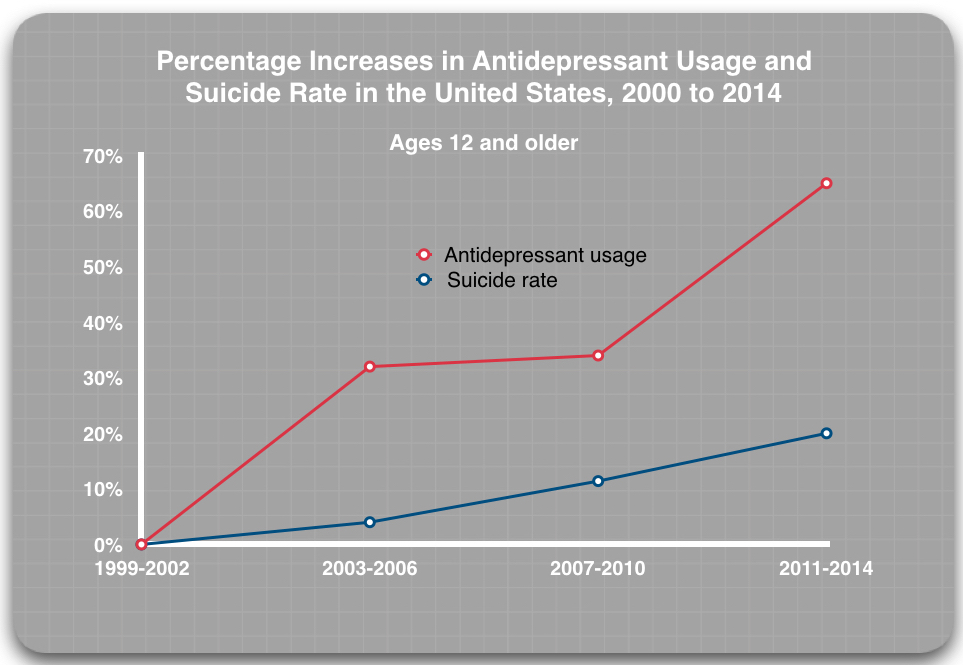

We also have VA data showing that antidepressants are regularly prescribed to veterans diagnosed with depression and PTSD, and for other difficulties as well. When we combine these data with an endless stream of personal testimony telling of how VA care unintentionally creates barriers to accessing non-drug therapies, we can see a story that fits together: Increases in the prescribing of drugs that double the suicide risk should be expected to increase the number of suicides.

This is what has occurred among the general public.

And, as the report I co-wrote showed, this is what has occurred at the VA.

Given these research findings and the VA’s statistics on suicides and antidepressant use, we can conclude that many veteran suicides over the past 15 years could have been prevented if the VA’s mental health care didn’t make such regular use of antidepressants. Going forward, I believe that any veteran suicide at the VA that occurs while a veteran is taking or withdrawing from antidepressants, and where the veteran was not properly warned of the risks of suicide and violence with the use of those drugs, should be attributed to their treatment.

In fact, I would think failing to provide such warnings to patients might leave the Department exposed to legal action from surviving families.

To stop these preventable tragedies from occurring, some steps can be taken that will not unduly strain VA resources. Specifically:

- Veterans being treated at the VA need to be given information on the risks associated with the use of antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs.

- They must be provided safe guidance on titration from antidepressants and should be prescribed stepped-down dosages when withdrawing from antidepressants so they can do so safely.

- They must be given better access to non-drug therapies.

- They must be given support for safely withdrawing from their medications.

Furthermore, there needs to be a public discussion of the VA suicide data, to include publishing of Behavior Health Autopsy Program (BHAP) reports, which detail VA suicides and shows higher suicide rates among those who access VA care. This disturbing reality needs to be known, and it shouldn’t be coming only from me.

Deprescribing Harm: Immediate Actions to Prevent Treatment-Caused Suicides

There are several immediate actions VA leadership can take to decrease treatment-caused suicides and to mitigate harm to veterans and their families.

- Veterans need to be given the information necessary for informed consent

Before being prescribed psychiatric drugs, veterans treated at the VA need to be properly educated as to the seriousness of the “Black Box Warning” associated with antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs and the risks for catastrophic harm from their use.

The VA currently views informed consent as a requirement that can be met by placing 10-to-20-page drug informational pamphlets, which are printed on tissue-thin paper in a font size that is difficult to read, in the box or paper bag that the new prescription is delivered in. The veteran, who is now by definition a psychiatric patient, is then believed to be capable and competent to understand a hard-to-read document that can mean the difference between life and death.

When veterans are prescribed medications, they believe their prescribers have their best interests in mind, and thus would not prescribe a treatment that could hurt them. While prescribers undoubtedly want their patients to do well, they themselves have not been well informed about the risks of antidepressant dependence, what safe deprescribing practices are, or the frequency of side effects with these drugs. Providers have also been misled to believe that successful withdrawal can be accomplished in a few weeks to a few months.

Many psychiatric drugs have known side effects that can make patients suicidal and violent. While the pamphlet for antidepressants includes a “Black Box Warning” that states antidepressants can increase the risk of “suicidal thinking and behavior,” even this warning doesn’t do enough to emphasize the risks associated with their use.

Shortly after I began treatment with Zoloft, I began experiencing severe arch, calf, and thigh pain, and some signs of foot neuropathy. My doctor conducted a variety of tests, and even after I replaced my shoes multiple times and was prescribed shoe inserts, nothing helped. It was not until I was completely off of Zoloft for more than six months that my foot and leg pain finally subsided. This pain disrupted my daily life, and this was only some of the physical pain I endured. The emotional pain included the anger, paranoia, and constant thoughts of death I had while on this drug.

Every veteran prescribed these drugs should be required to give informed consent in writing, and it should be required that the prescriber discuss such risks with the veteran.

Here is a suggestion for the language that should be used when informing patients of drug risks:

“This drug can make you kill yourself or kill people you love. It can make you violent, paranoid and prone to verbal outbursts. You must take this drug exactly as prescribed without ever missing a dose. Do not stop taking this drug unless you see your doctor first and together you create a formal plan for withdrawal.”

This conversation should also include informing the patient of risks of job loss or relationship failures due to lethargy or angry outbursts; increased risk for physical injuries such as muscle and ligament tears; increased risk for being diagnosed with fibromyalgia; and mention of all the other known side effects of these medications.

At the end of this conversation, the veteran should be required to sign a document stating that they understand all of the known side effects and risks of the respective pharmacological treatments and that they accept that many risks are unknown, since we are still learning about the long-term effects of antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs.

The mental health community at the VA, which includes psychiatrists, general practitioners, psychologists, social workers, and suicide prevention coordinators, should be required to take training that informs them of these risks. This training should be developed and delivered by veterans who have survived psychiatric drug harms. VA medical center “stand-downs” or an annual “mental health and drug-risk training” day for training should occur at every VA medical center and VA community-based outpatient clinic in the United States.

Until this training is conducted, new prescriptions for antidepressants should be halted and should only be resumed after all prescribers have been trained — although patients currently prescribed these medications should not be withdrawn from their medications unless they choose to. All prescribers should be required to sign certificates acknowledging that any harm experienced by their patients due to not having given informed consent may result in legal recourse.

2. Partner with a drug-compounding company so veterans can be safely withdrawn from antidepressants when they choose to do so

Deprescribing practices for antidepressants at the VA put patient’s lives at risk. Veterans who choose to withdraw from antidepressant treatment are told they can be safely withdrawn in a few weeks to a few months, but data show this is not the case. An article in the journal Addictive Behavior showed that more than half of patients described antidepressant withdrawal as severe. These withdrawal symptoms include suicidal thoughts, paranoia, violence, and physical pain. Additionally, from my own experience, it was during the withdrawal period that I was at the greatest risk of self-harming and causing harm to others.

Unfortunately, even when patients learn how to safely withdraw from this class of drugs—making 10% reductions over a year or more—the pills do not come in small enough dosages to continue safely titrating from the drug. As result, when patients get to the smallest dosage that they can reasonably eyeball and cut with a knife, they are ultimately forced to “cold turkey” from that dosage, or they have to try an incredibly difficult and unsafe method of diluting a liquid form of the drug with water or another liquid.

At the end of my full year of withdrawal from Zoloft, and after cutting the smallest dosage of these pills available into small granules, I learned that I could get the liquid form of the drug and dilute it to get the correct microdose I needed. Even when following the exact instructions I received from the VA pharmacist, the dose I ended up taking was incorrect. This made me sick for a week. I then decided that I could no longer accurately cut the pills any smaller, and because I did not trust the liquid-dilution method, I was forced to stop taking the drug before my body was ready. As a result, I was unbearably sick for several months, and my withdrawal symptoms increased dramatically as a result.

The VA should partner with a drug-compounding company to make fractional doses for patients who choose to get off antidepressants. A drug compounding firm in the Netherlands has created “Tapering Strips” that do this. Currently, I am unaware of any U.S. firms that compound antidepressants into microdoses, but the need for these microdoses is critical to safely withdraw from antidepressants. This action alone will save lives.

3. Provide veterans with bureaucracy-free access to counseling

At many VA medical centers, when a veteran requests access to a counselor, they must first complete a month-long group program or treatment planning course. If they do not feel comfortable with a group program, they are offered Telehealth therapy. Many veterans do not feel comfortable talking to a computer screen, as they want to speak with a person who can empathize with them in person. If the veteran declines these two options (group therapy or Telehealth), they can then be denied access to counseling.

I was personally impacted—and negatively so—by this policy. So too was Army veteran Daniel Somers, who was a patient at the Phoenix VA. After requesting counseling, he was told he needed to complete a group program, but when he was denied group treatment due to concerns related to his sharing information that could affect his security clearance, he was then denied access to a counselor. Not long after, Somers killed himself, leaving a letter implicating the VA in his death. For the past seven years, his parents have been fighting to get this policy changed, but as of this writing, it remains the same.

This problem can easily be solved. Any time a veteran requests a counselor they should be provided one. They do not need to be put through a series of hoops to jump through. If the patient and the counselor decide that group therapy or a treatment-planning course separate from their sessions would be helpful, that should be pursued, but access to care should not be denied based on bureaucratic rules like the ones in place today.

4. Fix harmful prescribing practices

Overprescribing: According to a recent GAO report, only 15% of veterans sampled from five VA medical centers were offered talk therapies in lieu of drug treatments. My patient experience reflects a similar scenario, as I went spans of four and eight months being prescribed multiple psychiatric medications without ever meeting with the prescribing psychiatrist. When I did meet with the psychiatrist, the average time of supportive therapy was only 15.7 minutes, again all the while not seeing a counselor. This was part of my experience during four years of treatment.

Reporting of adverse events: Veterans regularly have negative reactions to psychiatric medications, but psychiatrists, providers, and therapists are not trained to look for these side effects. Outbursts directed toward family members and employers can lead to relationship failures and job loss. Also, foot, leg, and hand pain, as well as neuropathy, are common in patients prescribed antidepressants, but questions searching for physiological pain are not posed to these patients.

Instead, veterans’ symptoms are treated separately from their medication monitoring, and the role of the drug is never considered. Many of these mysterious pains subside only after the patient is withdrawn from their medication. Yet the cause of the pain—the drug treatment—is never identified.

When negative reactions are recognized, they are rarely reported using the VA’s required internal protocols. Unless the patient insists upon a report being filed, this is rarely done. To my knowledge, the aggregate data from these patient reports are not used in any meaningful way by VA headquarters to deliberately reduce prescription rates of drugs that are determined to cause harm. This is something I am also personally familiar with. When I told my psychiatrist that I wanted to report an adverse drug event, confusion ensued. I was initially directed to report this to the FDA, even though the VA had prescribed me the drugs.

Polypharmacy: Today, many veterans treated at the VA are being prescribed multiple psychiatric drugs at a time, a term the medical community calls polypharmacy. According to a GAO study, among those diagnosed with depression who were treated in primary care and “specialty mental health care” settings, 35% were taking two classes of psychiatric drugs, and 15% three classes of drugs.

The polypharmacy was even more pronounced for those diagnosed with PTSD: 36% were taking two classes of psychiatric drugs and 25% were taking three or more classes.

In my case, I was first prescribed Adderall, as both my prescriber and I believed that I had ADHD. Not long after, I was prescribed Ambien because I could not sleep because of the Adderall. Gabapentin was prescribed off-label as a mood stabilizer to treat anxiety, another side effect also caused by Adderall. Finally, the antidepressant Zoloft was prescribed for the severe depression I was experiencing due to the combined effects of all these drugs and other prescribed medications.

The circular prescribing practices I experienced began with a stimulant, which led to a fairly rapid escalation of the number of psychiatric drugs I was prescribed. Many veterans may have an initial complaint of depression and be prescribed an antidepressant, but then they are given a new or additional diagnosis and they, too, quickly end up on three or more psychiatric drugs at once.

5. Stop being so quick to diagnose a veteran with a psychiatric disorder

VA physicians and psychiatrists need to remember that they are doctors, which means that when a veteran presents with a complaint, they need to conduct comprehensive physiological testing to rule out potential physical causes of psychiatric symptoms, such as nutritional deficiencies, hormone imbalances, organic illnesses, and chemical toxins (which service members—including me— are commonly exposed to as part of their duties). These are just a few of the physiological factors that can cause symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, sleep problems, and the like.

As stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) all of these physical factors should be eliminated before a psychiatric diagnosis is made and before psychiatric medications are prescribed. Yet, in VA settings today, this is not occurring.

Additionally, social factors—such as housing stability, employment, underemployment, and relationships—need to be addressed. These complaints are seen by many prescribers as having a secondary relationship to psychiatric symptoms, instead of rightly being understood as direct causal factors in many diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

Yet, both these physical and social factors are routinely ignored. Veterans are seen as presenting with various “psychiatric symptoms” and are then quickly diagnosed and prescribed drugs. This process increases their risk of suicide.

Before any psychiatric drug treatment, all physiological testing should be completed and screening for social factors should be performed. There should be interventions to ensure the veteran is not at risk of losing housing or struggling with relationships and is helped with finding full employment or gaining access to educational opportunities.

My Crusade

Part 1: Change

Secretary Wilkie, this open letter to you is part of a larger campaign I have been building to get the VA to effectively respond to this crisis.

In March 2018, I drafted what I titled the “Antidepressant Harms Analysis and Antidepressant Role in Veteran Suicide Resolution” for the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and the American Legion. On April 4, I introduced the resolution at our American Legion Post meeting in Ann Arbor. Four days later, I introduced the resolution to my VFW post. The statistics cited in the resolution shocked the post members, as most of the veterans within both of my posts are patients of the Ann Arbor VA and are very happy with the care they receive. But when I shared my story and explained where the numbers came from, both posts voted to escalate the resolution to the VFW Department of Michigan for a vote.

A month later, the first major vote was held at the state conference of the Department of Michigan. After hearing remarks from Lauren Bowen, who had lost her husband and their children’s dad to suicide after he was treated with psychiatric drugs at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, the convention passed the resolution unanimously, making the investigation of these drugs in causing veteran suicides part of the legislative agenda for the VFW of Michigan. A few weeks later the American Legion held its state conference. The resolution passed unanimously there as well.

On July 22, I gave the keynote address to the Veterans of Foreign Wars Memorial Service at the organization’s National Convention. Many of the Gold Star Mothers, some of whom had lost their children in combat and others to suicide, came up to me after my remarks. Initially, I was afraid that I had offended them, as I had spoken of veteran suicides and policy changes that needed to be addressed. Instead, many were in tears. While saddened at hearing my own harrowing personal story, they appreciated it, as many of them had seen the same story play out in their own families. Tragically, with worse outcomes than mine.

A few days later the resolution was passed on the floor of the convention, making the investigation of antidepressants into veteran suicides part of the VFW’s national legislative agenda.

In late August, at the American Legion’s national convention, concerns were raised in committee that the 32% higher suicide rates cited in the resolution might unintentionally deter veterans from seeking mental health treatment at the VA. A short debate ensued, but the discussion ultimately returned to informed consent and the committee concurred that veterans have a right to know if their treatment could cause them harm. The resolution was passed through committee, and a few days later the American Legion voted to make the Antidepressant Harms Analysis Resolution a key component of their legislative agenda.

These resolutions also detailed that service members and veterans:

- Have high prescription rates of psychiatric drugs: Veterans at the VA have disproportionately greater access to psychiatric care than non-VA using veterans; this concern was also confirmed by a DoD analysis of deployed service members, which found 70% to 80% prescription rates for those diagnosed with depression or post-traumatic stress.

- Are prescribed antidepressants that come with Black Box Warnings: Nearly all antidepressants come with a “Black Box Warning” stating that the drugs can “increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in young adults.”

- Lack informed consent: Service members and veterans are not being adequately educated that antidepressants can make them suicidal and violent.

- Lack information about antidepressant withdrawal risks: Service members and veterans are not warned about the severe withdrawal risks associated with antidepressants, and that once they are started on an antidepressant, they could become dependent on them for years, in some cases permanently.

The goal of my efforts is for Congress, the VA, and the DoD to investigate the suicides within their respective departments with a focus on conducting an “antidepressant harms analysis”. This forensic-style analysis is necessary to understand the total body count caused by these drugs and a full accounting of the physiological, emotional, and financial harms we have unknowingly inflicted on millions of active-duty service members, reservists, guard members, veterans, and their families.

Part 2: Education

By helping other veterans, service members, and their families to tell their stories through the webzine Mad in America, and by telling my own story, I aim to help people make better-informed decisions regarding their treatment plans and to understand the dangers of antidepressant drug withdrawal. I believe it is important for the country to be made aware that many drugs that have been sold to the public and veterans as safe and effective are, for many veterans, not safe and effective. As a result, when combined with dangerous prescribing practices that have been codified into policy at the VA and DoD, we have been prescribing an epidemic.

My writing includes a five-part series. In the first, “Ambushed by Antidepressant Withdrawal,” I share the painful story of my yearlong withdrawal from Zoloft. In the second, “Screening + Drug Treatment = Increase in Veteran Suicides,” which I co-authored with journalist Robert Whitaker, we lay out the data story of treatment-caused suicides at the VA and how the suicides at the VA are only a sample of what is also happening outside of VA walls. In the third, “Prescribing an Epidemic,” I share my four years of treatment at the VA.

The open letter I am writing to you now is the fourth part. In this letter, I am setting forth my understanding of the source of this crisis and my thoughts on what we can do immediately to reduce the harm being done to veterans and the decrease the number of veteran suicides at the VA.

In the final part of this series, I’ll discuss the long-term restructuring of mental health at the VA that will be needed to ensure that our nation’s service members and veterans are given the treatment and opportunities they deserve for their service to this nation.

While an investigation and an antidepressant-harms analysis are urgently needed, we must first stop the bleeding. I beg for you to take the actions above, as they will save lives.

Sincerely,

Derek Blumke

Editor, Veterans & Military Families

Mad in America

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

For veterans is good to collect dry herbs and then sell them to church, it is how in my country. But this is only the first step..

Report comment

Herbs good way to make money … spice trade very lucrative short time ago … queen England likes her tea, not so happy with Chinese and Indians, make too much trouble. Curry good too … naughty people say she no good, money always good for health. Queen UK live very long time, is proof.

Report comment

Spice picking is also effective therapy

Report comment

Smoking grass (in moderation if need be) is also therapeutic. The spirit herb.

Report comment

“I am writing you this public letter to ask for your help. I’m working to decrease daily veteran suicides by 25% to 50%, from 20 a day to 10-to-15 per day.”

It’s a bit like reducing your daily intake of sugar.

Report comment

Well written, a tearjerker sincerely, thank you for speaking out, Derek. But I think you have a typo in this sentence:

“In this letter, I am setting forth my understanding of the source of this crisis and my thoughts on what we can do immediately to reduce the harm being done to veterans and the decrease the number of veteran suicides at the VA.”

Again, thank you for what you are doing.

Report comment

Derek Blumke:

Bravo to you!

THIS too is going on all over the place in the general population!

I recognize the special needs of veterans, but it parallels much of the experience of this Nation—drugs that are harmful, no emergent attention and inaccurate diagnosis to name a few. Prescribers can’t figure out what a drug effect is and call it something else, namely something wrong with YOU.

It might help to recognize that soldiers are much less congratulated and appreciated in the social context of which they come back home to these days. Social pressures can be a precipitating factor to suicide. It’s true for everyone.

Try art therapy for PTSD. I once read a good success rate on a project that focused on drawing faces.

Good luck. I’m glad you’re out there doing the work!

Report comment

“Less congratulated and more appreciated.” Bingo!

Report comment

I am a Vietnam Veteran who ran into the buzzsaw of the VA mental health system in the 1970’s. There was a lot of forced treatment, including, for me, a long stay in a Ct. State Hospital where I was tied down to a bed, face down and forcibly injected with drugs like Thorazine until I was nearly unconscious.

It was a nightmare, and getting off the drugs was an absolute nightmare because the VA, and my parents, saw me as defective and this was all prior to the diagnosis of ptsd…

well, the story is a long, long one so I will shorten it. I thank you for your work, for me, the hardest steps were the first ones as no one, absolutely no one, encouraged me to strike out for good health.

Talk therapy was a great help, especially at the Vet Center level.

Hugh Massengill, Eugene Oregon

Report comment

Derek,

Let me guess what your VA psychiatric diagnosis is. I’ll bet that it is the same as mine – paranoid schizophrenia. That means that anything you say can and is likely to be disregarded.

Just remember this:

“Half way down the trail to Hell in a shady meadow green

are the souls of all dead troopers camped near a good old time canteen

and that immortal resting place is known as Fiddler’s Green.”

Report comment

Yes the VA and whoever touts psychiatry is lying.

People think it’s a drastic word, “lying” and some people get as radical as to gently ‘allow’ us that perhaps “some shrinks fail”, that “perhaps some folks are not lying, but rather misinformed”.

Anytime we promote something as carrying weight, especially if it promotes these practices for others, we better be well informed and once we are truly informed, then if only presenting on side of information is lying.

End of story.

First off all, we need rid of the BS DSM. It is a book of lies. Then we need to get rid of the science lies.

No science in creating chemicals that disturb randomly. Those chemicals invade every single cell and neuron. Nothing will ever work the same.

We seriously cannot fix crazy. The real crazy are simply the people in power.

Report comment

This is a brilliant and courageous article! I so admire how bravely you are putting yourself out there and how skillfully you have pulled together so much relevant information! I will be amazed if you even hear back from Wilkie. He has ignored the letter I sent to him, even though I met him, he gave me his card, and he said to write to him.

Report comment

Paula,

It is telling. Challenge is scary for people who are selling something dishonest.

Report comment