A new article in the Journal of Constructivist Psychology explores how experiences of psychological distress are intertwined with how power is experienced in their life. The author, Mary Boyle, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of East London, contends that power is a central part of the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) and that imbalances of power, which often cause psychological distress, are consistently overlooked by psychological literature.

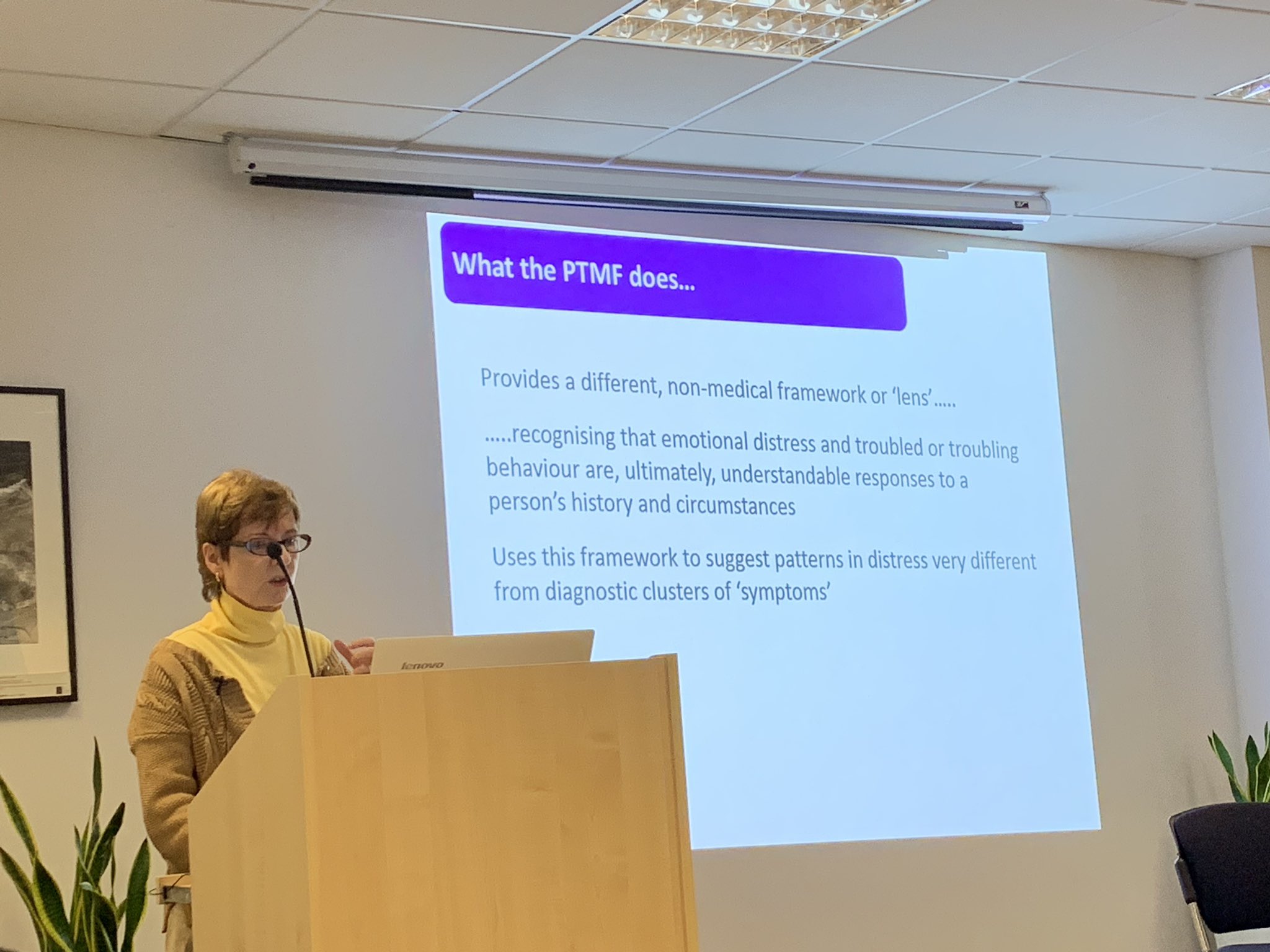

PTMF is an alternative framework for understanding psychological suffering that does not resort to traditional models of psychiatric diagnosis. It has been built by prominent psychologists and service users who observed that what we consider symptoms are mostly people’s responses to threat in the face of adversity.

Boyle notes that power, or the lack of it, plays an essential role in our understandings of mental suffering. For example, psychological distress in children is often associated with early abuse and adversity, which are a direct result of their powerlessness. Similarly, other instances where people are rendered powerless, such as poverty, homelessness, and involuntary hospitalization, have also been linked to increased psychological distress, and even suicide.

Boyle writes that the context of a person’s life is central to their experience of distress, but that, traditionally, their lived experiences have been given a secondary place in psychological research. Most research attempts to identify internal factors, such as chemical imbalances or intrapsychic processes (e.g., faulty thinking patterns), as the cause of symptoms. This approach to psychology treats people as separate from their social world, reifies mental disorders as acontextual entities, and transforms experiences of social adversity into psychological problems such as low self-esteem.

On the other hand, the PTMF asserts that people are always already social beings, and considers the operations of power as essential in understanding people’s emotional and psychological experiences. This approach shuns simplistic notions of what causes a ‘mental disorder’ by noting that many causes work together to produce certain forms of distress.

PTMF also acknowledges that some factors occurring together might increase or decrease the chances of individual developing symptoms. For example, a recent study showed that immigrants might have higher incidences of psychosis, but chances of psychosis decrease for immigrants living with others from their area of origin.

Using Michel Foucault’s work, the author notes that power is not merely repressive, but that it uses language to produce certain norms in society to decide what is normal, good, ethical, desirable, and healthy. Thus, power is creative and productive, and it masks its own creations. In other words, ways of thinking and behaving that are constructed as “normal” by people and social processes, are presented as natural, thus ensuring that they are never challenged.

For example, a common assumption in psychology and psychology is that hearing voices is a naturally distressing experience. However, recent research has shown the presence of distress to be culturally determined, suggesting that distress may, in part, be due to cultural expectations of normality.

We are always part of the power relations within a society, and these operations often mask the causes of our distress. For example, critical scholars have argues that in a capitalist society, work stress is normalized as a part of modern living and less of considered as the cause of someone’s depression.

Boyle writes that forms of power in the PTMF include biological power, where some people possess the biological or embodied properties that a society values, for example, thinness, light-skin, certain talents, being able-bodied, etc. There is coercive power, which includes the ability to force one’s will on another through violence and intimidation. She also describes economic power, interpersonal power, and legal power. The most important mode of power that concerns psychological distress is ideological power, which Boyle describes as:

“Any capacity to influence language, meaning, and perspective. The power to create theories that are accepted as ‘true’; to create beliefs or stereotypes about particular groups, to interpret your own or others’ behavior or feelings, and have these meanings validated by others; it also involves the power to silence or undermine.”

In PTMF, there are three main ways power is related to psychological distress. The first is through cultural narratives of distress. Different cultures have different understandings of what constitutes a symptom, what distress means, and how to explain these phenomena. For example, research has shown that cultural narratives around hearing voices are different in India and Ghana. Thus the experience is also different, and people more often report a positive or neutral relationship with these voices.

The dominant cultural narrative about emotional distress in Western society is that of medicalization. People make sense of their experiences using these narratives and often understand others and themselves as having a ‘mental disorder’ with a biological cause. This consensus is achieved via language (‘mental disorder,’ “symptoms’) and is furthered by powerful institutions (hospitals, the American Psychiatric Association), and practices (diagnosing, hospitalization). Only certain types of research (statistical, genetic) that support these narratives are valued and receive funding.

Boyle writes that these medical narratives are supported by Western individualism. For example, resilience is often seen as a personal quality rather than an attribute of a good support system around a person. These cultural narratives influence how people form their identity (I am ‘depressed’), think of themselves (as a self-reliant individual), and understand suffering (caused by neurotransmitter imbalances).

In this view, the field of psychology is seen as having the cultural power to create theories and language around what is healthy or abnormal. This includes the use of diagnostic categories and narratives of ‘mental health.’ With the use of this knowledge, people’s experiences of distress are given new meanings.

Likewise, psychiatrists use the legitimacy of medicine (the medical model) to validate each other’s theories by publishing in expensive, inaccessible journals and using overly technical language. They are helped by institutions that regularly portray mental distress as biologically caused and fully treatable by medication. All alternative understandings are silenced or ridiculed as unscientific.

People internalize the cultural narratives about causes of distress through the processes of self-surveillance and self-policing, and our own feelings and behaviors are regulated according to prevailing norms. These constructed norms in Western societies are presented as self-evident scientific truths.

PTMF suggests that emotional and mental distress often arises from a disconnect with ideologies that support only certain styles of being, such as specific standards of what is attractive, or what constitutes proper child-rearing, gender-appropriate behavior, etc. Thus, people use these culturally available narratives to give meaning to their own experience, often to their detriment. Ian Hacking had previously noted this phenomenon called the looping effect.

Further, power in PTMF is also seen as attacking the core needs of people, such as the need for safety, being valued in society, having some control of one’s life, etc. Thus, certain operations of power create threatening contexts for vulnerable populations. Adverse social conditions of gross power imbalances, especially poverty, create numerous disadvantages leading to psychological problems.

PTMF notes that many of the ‘psychological disorders’ are often people’s survival responses to these threatening contexts; these responses include a hypervigilant startle response, self-starvation, drug abuse, overworking, etc.

These responses, which are usually attributed to dysfunctional biological or intrapsychic processes, are instead seen as having a purpose in an individual’s life. They could be useful to regulate emotions, protect the self, or define identity. For example, dissociation is a response to being utterly powerless in a situation from which there is no actual escape, such as physical or sexual abuse.

Power also influences whether a person experiencing mental distress can escape that situation; it is difficult to leave an abusive relationship when one is impoverished or too young – both positions of relative powerlessness.

Boyle concludes that this perspective on human suffering and psychological distress opens up possibilities of social action and change. This is especially important since the traditional understandings of mental distress, as similar to physiological illness, has been linked to greater dehumanization, stigmatization, and alienation of the patient.

****

Boyle, M. (2020). Power in the Power Threat Meaning Framework. Journal of Constructivist Psychology. Published online first: May 29, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2020.1773357

Excellent article! Some of these things seem so much like common sense that should be obvious to any thinking person. But as many of us know, the obvious so often needs to be made known to the mental health industry.

Report comment

As Tim McCarver once said, “It it were that common, more people would have it!”

Report comment

I notice the people that do genuinely recover tend to recover independently, of the Very Expensive UK Mental Health System. In other areas of Medical Achievement the NHS is considered to be maybe the best in the world.

Report comment

“the field of psychology is seen as having the cultural power to create theories and language around what is healthy or abnormal. This includes the use of diagnostic categories and narratives of ‘mental health.’ With the use of this knowledge, people’s experiences of distress are given new meanings.”

Theories and language are not good enough to become a “diagnostic” tool to affect those without power to wield same.

Of course “society” has a so called norm, where some end up lying in gutters, getting nothing. How it ever wound up to call those in gutters as “mentally ill”, in need of treatment is beyond me. It serves purely as income. This is not science lol, it is power. And the distress becomes tenfold. Psychiatry/psychology has worsened the outcome, and of course politicians can see this. No one has the guts to rise up against these false narratives of some pretentious “norm”. Society is in a constant state of reinventing itself, but always based on power. We have yet to rise above the instinct to slay those who are powerless.

Let’s not pretend that the vulnerable are being “helped”.

Report comment

The powers that shouldn’t be, those who call themselves “the elite,” in a country where we are supposedly all “created as equal.” They have a habit of pretending power does not have a value, when that is obviously not true. They made this “mistake” in the field of micro-economics too, which is part of why the micro economic theories don’t work, at least for the masses. My favorite former economics professor wrote a book explaining this.

https://www.amazon.com/Bigness-Complex-Industry-Government-Economics/dp/0804749698

We do all need to admit that power does have value, and that the abuse of power is rampant in this world, especially within the “mental health” industry. But that’s because the “mental health” workers have unwisely been given the power to play judge, jury, and executioner to anyone they want, and for any reason they want. And since “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Of course, the “omnipotent moral busy bodies” of the “mental health” industry have completely corrupted their industry.

They’ve turned their industry into a primarily child abuse covering up, pedophile aiding, abetting, and empowering industry.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

So we all now live in a “pedophile empire.”

https://www.amazon.com/Pedophilia-Empire-Chapter-Introduction-Disorder-ebook/dp/B0773QHGPT

“This is especially important since the traditional understandings of mental distress, as similar to physiological illness, has been linked to greater dehumanization, stigmatization, and alienation of the patient.”

Yes, the current DSM paradigm’s intentional goals are “dehumanization, stigmatization, and alienation of the patient.” There is nothing “helpful” about being defamed with an “invalid” DSM disorder, then being neurotoxic poisoned. That is blatant and intentional harm of another human being.

I’m glad some psychologists are starting to speak some common sense, and absolutely I agree, the DSM brainwashed do need to be taught common sense, not to mention common decency. Systemically aiding, abetting, and empowering pedophiles – by neurotoxic poisoning millions of child abuse survivors – is not actually acceptable, legal, or “professional” behavior. But the DSM is, by design, a child abuse covering up “bible.”

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

I do hope the psychologists and psychiatrists will rethink their function in our society, garner insight into the fact that systemically aiding, abetting, and empowering pedophiles wasn’t actually a wise idea, and get out of the business of neurotoxic poisoning millions of innocent child abuse survivors.

Today, “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).”

And the eighty plus percent of your clients, who are survivors of child abuse, should be weaned off the psychiatric drugs, because the psychiatric drugs do NOT cure distress caused by trauma or abuse. The psych drugs can and do create the symptoms of the “serious DSM disorders” however.

The ADHD drugs and antidepressants can create the “bipolar” symptoms, as pointed out by Robert Whitaker. The antidepressants and antipsychotics can create psychosis and hallucinations, which are among the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. And the antipsychotics can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://www.alternet.org/2010/04/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

In other words, both “bipolar” and “schizophrenia” are iatrogenic illnesses that can be created with the psychiatric drugs. That might be relevant information for the psychologists to pass amongst yourselves, if your goal is actually to help your clients, rather than perpetuate your pedophile empowerment business into perpetuity.

And I do believe the psychologists have a moral obligation to be speaking out against our massive in scale, modern day psychiatric holocaust. Since mainstream psychiatrists and other mainstream doctors are murdering “8 million” people EVERY year, based upon the “invalid” DSM disorders, and with the neurotoxic psychiatric drugs.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mortality-and-mental-disorders.shtml

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

“8 million” innocent people killed EVERY year is more than died in the entirety of the Nazi psychiatric holocaust. It’s past time to end our modern day psychiatric holocaust.

Report comment

This whole article was a deep, sublime breath of fresh air for my grieving heart. Ayurdhi, if you have ever wanted to bring sanity and justice to someone’s life with your work, you have done it today for me with this article. Thank you!

I should add that this piece would be the perfect “intro” for anyone who has not heard of PTMF yet – a little sample of how much sense it makes, so to speak. Such a great article to have on MIA, I encourage anyone to send this around to friends to open up conversations

Report comment

I wanted to thank Ayurdhi for this piece. And thanks to professor Boyle.

I was not aware of PTMF, as framework. This is an article that brings

a sensible view to the chaotic and it could do so much good if allowed.

Very thankful that prof. Boyle has identified and tackled this very important

issue.

Report comment

More of the same. PTMF is relevant only to the unnecessarily mystified, and to professionals. The “power threat” we need to overcome is capitalism; understanding that provides a framework for the formerly mysterious to take on new meaning.

Report comment