In the American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatrists Nathaniel Morris and Robert Kleinman from Stanford raise the issue of who is financially responsible for psychiatric treatment when someone is involuntarily detained. With the practice of ‘surprise medical billing,’ patients are charged for out-of-pocket medical costs that they did not anticipate. Ethical considerations around informed consent for treatment risks have also been raised in billing research participants for injuries caused during a research study.

Surprise medical billing includes billing for treatment in situations where someone cannot authorize medical care in emergencies, as informed consent for treatment cannot reasonably be obtained before it is given. These include stroke, heart attack, severe injury, or when someone is not fully conscious. While life-saving care may have been necessary, surprise medical bills from such treatment can have devastating consequences for patients and their families, including financial ruin.

As such billing practices have garnered more public attention, legislation in the US Congress is being made to limit such practices and protect healthcare consumers. However, the authors argue that billing patients for involuntary psychiatric care should be a major part of this discussion. Unlike in many of the previously mentioned situations where medical treatment is provided without informed consent, patients in involuntary detained may be forced to engage in psychiatric treatment against their will.

“All US states have statutes that authorize emergency and inpatient civil commitment, such as involuntary hospitalization on grounds of dangerousness to self or others due to a mental disorder, and a majority of states have provisions for outpatient civil commitment. These statutes are based on principles that under specific circumstances, individual and/or public benefits of managing someone’s mental health needs supersede that person’s rights to refuse psychiatric care,” Morris and Kleinman write.

Invoking the principles of autonomy, justice, and beneficence in medicine, the authors ask whether forced financial liability for involuntary psychiatric treatment infringes on other liberties beyond those outlined in such civil commitments. A recent report to the United Nations Human Rights Council proposes a rights-based approach to mental health care that sees forced treatment as problematic.

Invoking the principles of autonomy, justice, and beneficence in medicine, the authors ask whether forced financial liability for involuntary psychiatric treatment infringes on other liberties beyond those outlined in such civil commitments. A recent report to the United Nations Human Rights Council proposes a rights-based approach to mental health care that sees forced treatment as problematic.

Additionally, previous research has found coerced psychiatric hospitalization increases the risk of suicide, which poses the question of whether patients should be held financially responsible for care that is harmful to them.

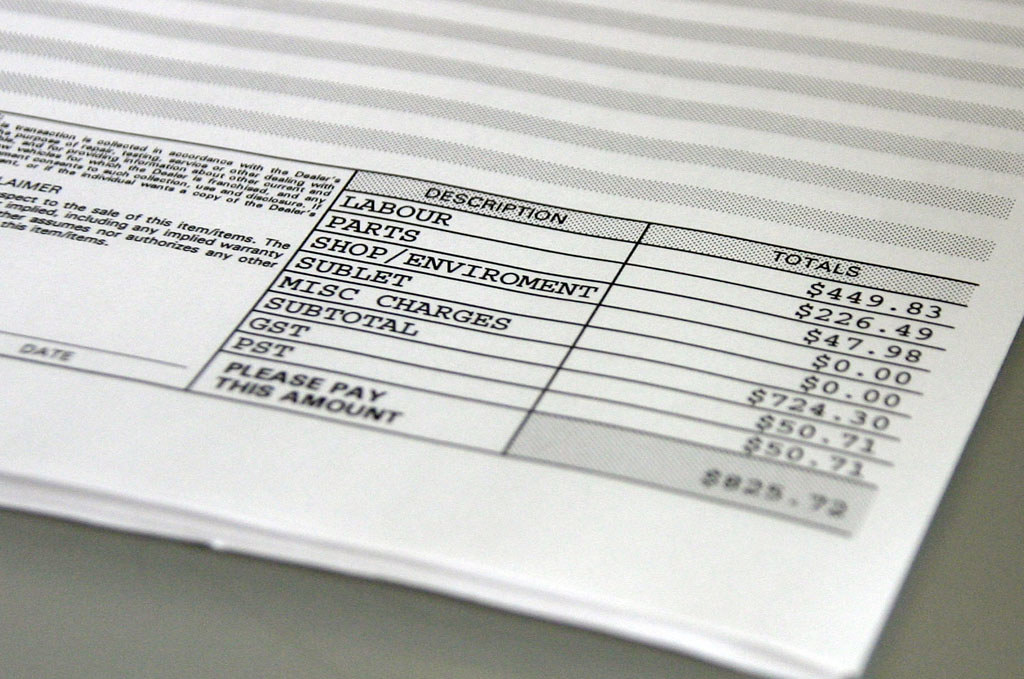

Involuntary psychiatric treatment is incredibly costly, with the authors citing the high cost of inpatient stays that averaged just over $7,000 for about a week of treatment. Additionally, it has been found that many hospitals charge about 2.5 times more for inpatient psychiatric care than it costs to deliver that care. While we know that involuntary hospitalizations make up just over half of inpatient hospitalizations, there is no published data on how often patients who received involuntary psychiatric treatment were charged for out-of-pocket expenses.

Inpatient care (voluntary or involuntary) is usually paid through various sources that include public programs (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid), private insurance, charity programs, and out-of-pocket spending. Over half of payers for inpatient treatment were public programs. However, the authors note this data did not specify how many of these stays were involuntary or whether they led to out-of-pocket expenses. This is particularly important to understand because additional expenses such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance can be charged to involuntarily committed patients.

Another point that the authors make in favor of addressing the issues of surprise medical billing for involuntary psychiatric treatment is the particular vulnerability such patients face. Because of psychiatric impairments that are severe enough to warrant involuntary commitment, some patients may not have the capacity for financial decision-making.

On top of this is the notorious opaqueness of health care billing that makes it challenging for patients to make determinations about financial responsibility for such treatment. Additionally, patients diagnosed with more ‘severe mental disorders’ are more at risk of experiencing poverty, and such surprise medical billing could make their financial situation much worse. The authors add:

“Because patients with severe mental disorders already are at increased risk of experiencing poverty, these bills may be especially burdensome for them to pay and can cause other long-term harms, such as discouraging patients from seeking care or worsening credit scores. Psychiatric patients’ vulnerability, combined with the coercive nature of involuntary care, could also foster outright exploitation.”

Assuming involuntary commitments for psychiatric care are here to stay for the foreseeable future, we are still left with the question of who will pay for these services. With the rising rate of involuntary psychiatric detentions in the US over the past decade, this issue of payment for such treatment becomes increasingly important to address. Debates on how much involuntarily detained patients should pay versus other entities involved (public programs, private insurance, health care facilities) are influenced by how much one sees the individual and collective benefits from receiving psychiatric care.

“Further complicating matters, certain aspects of care, such as presenting to an emergency department, might be voluntary, whereas other parts, such as emergency administration of medications or inpatient civil commitment, might be involuntary.”

Given the legal complications this issue of payment brings up, courts have gone in different directions. The authors note two cases: one that went to the Supreme Court of Iowa in 2000 and ruled that an involuntarily detained patient was liable for payment under an implied contract in law; in another case in New Jersey as an appeals court in 2018 ruled in favor of a patient because of a procedural error made by the hospital.

The authors propose some next steps to better inform those in the field and the public about the scope of the problem and how we might address it in a more just manner–though each comes with its own complications. They suggest that if state laws require involuntary treatment, then the state should pay uncovered costs for uninsured or underinsured patients. However, states may not set aside funding for such expenses, and it could encourage private payers to cover less for involuntary care. Another idea proposed would be to prevent hospitals from marking up charges, though this could mean that they would be less likely to offer psychiatric services.

In the case of Massachusetts’ 2006 health reforms, increasing health insurance coverage for young adults, behavioral health disorders demonstrated a decrease in inpatient admissions and emergency department visits. Such results are contrary to expectations that insurance expansion will lead to higher usage of intensive services and increases financial protection for such patients and hospitals providing such care. Though, given the lapses in mental health coverage by some private insurers for longer-term outpatient treatments that treat underlying issues, it is worrisome that psychiatric patients may incur more financial costs as payers focus on short-term crisis management treatments that end up costing more in the long run.

“In 1980, Congress passed the Mental Health Systems Act, which included a bill of rights for mental health patients under 42 U.S. Code § 9501. This list served as a model for states across the country and included rights to individualized treatment plans, freedom from restraint outside of emergencies, confidentiality of records, visitors, and telephone access, but it left out any mention of the financial implications of involuntary psychiatric care for patients,” the authors note. “As Congress considers steps to curb surprise medical bills, this omission warrants another look.”

****

Morris, N. P., & Kleinman, R. A. (2020). Involuntary commitments: Billing patients for forced psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(12), 1115–1116. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030319 (Link)

Yet another excellent article. “Psychiatric patients’ vulnerability, combined with the coercive nature of involuntary care, could also foster outright exploitation.”

I definitely feel like this was true in my case. There’s nothing quite like having survived the trauma of childhood, albeit with lingering symptoms of Complex PTSD, such as hyperarousal, only to be retraumatized thirty years later, when those symptoms, in combination with those from a micro bleed in my cerebellum, were mistaken for hypomania, despite no previous history of mental illness, and my being, at age 50, well beyond the typical age of onset which is 18.

All of which resulted in an involuntary hospitalization. And upon surviving that, I was then sent a bill for thousands of dollars, $16,000 paid by my insurance, and $4,000 paid by me, during a year in which I was on furlough due to COVID-19. Adding financial and psychological injury, to the insult of having my civil rights suddenly stripped away, without due cause, let alone due process.

All it took was the retaliation of a coworker whom I had earlier reported for repeatedly drinking at work, who just so happened to answer the phone when the doctor called, and availed himself of the opportunity to get back at me. A phone call I was not made aware of myself, until a week after I was finally discharged.

The fact that the authors themselves recognize that making involuntary hospitalization less profitable, would likely decrease its frequency, suggests that outright exploitation is indeed already happening. As if my personal experience, as well as those of so many others, isn’t proof enough.

Given that doctors, including psychiatrists, are indeed fallible, as much as they’d like to convince themselves otherwise, I personally am opposed to their taking such an action, one which is traumatizing on so many levels, resulting in consequences that once done, cannot be undone. Just like the death penalty.

Given the number of innocent black men we have wrongly imprisoned, one wonders how many we have killed. In both instances there is no way to undo the damage once it has been done. So perhaps we might want to take that fact into consideration. What happens if and when doctors or judges do make a mistake. “Oops.” “My bad.” Doesn’t begin to cover it.

Another issue to consider is how many patients, such as myself, lose their jobs as a result of their involuntary hospitalization. In my case, once it was discovered that this particular employee had lied, he was fired, but do I really want to return to work for an employer who would allow such a thing to happen in the first place? An employer who would take the word of such an employee, over that of their Lead Server, and second most senior employee, having worked there for just under four years? Is it even safe for me to do so.

Fortunately, given my excellent reputation in the community otherwise, I was eventually able to obtain another position. Nine months later, however, because I work in the hard hit restaurant industry during a pandemic, in an area where the industry is also very seasonal. I also must contend with the stigma of mental illness, despite not being mentally ill in the first place, because of my willingness to speak out against and write about my very negative and traumatic, not to mention life changing, experience. My relationships with my entire family have been wiped out also, as a direct result of their failure to come to my aid. Fortunately, this has turned out be something of a blessing in disguise. It does however, rule out Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Easter.

Report comment

“Psychiatric patients’ vulnerability, combined with the coercive nature of involuntary care, could also foster outright exploitation.”

I would not say “could” here. I would say, “…will inevitably lead to outright exploitation.”

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Reading this the second time it seems that you may be laboring under the illusion that, while you are not “mentally ill,” other people are. Could you clarify?

Also (as an aside):

Given the number of innocent black men we have wrongly imprisoned, one wonders how many we have killed.

Who is “we”? Are you a prison administrator or politician?

Report comment

Arguably, IMO, there is such a thing as mental illness i.e, some sort of physical illness, damage, or genetic impairment within the brain that in turn, affects the functioning of the mind.

And ‘we’ as a society, because presumably, we have some say. Here in America at least. If we, as a society, either put to death or allow to be put to death (or involuntarily hospitalize or allow to be involuntarily hospitalized) someone who may in fact be innocent (or free of/not suffering from mental illness) on account of our own fallibility, do we not therefore become guilty ourselves, of causing the same harm to others as those we have accused of doing or possibly doing the same? Are we not in the least bit complicit, even if we do stand by and do nothing ourselves?

Report comment

Arguably, IMO, there is such a thing as mental illness i.e, some sort of physical illness, damage, or genetic impairment within the brain that in turn, affects the functioning of the mind.

This is a contradiction — what you are describing is brain damage, which is physical, not mental. The “mind” is an abstraction, and not subject to disease or any other physical characteristics. The conflation of the abstract and the physical is an increasingly common tactic for manipulating discourse, and we need to be able to spot it.

Report comment

Tripping old women on the sidewalk and taking their purses is wrong.

Discussion?

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I was wondering when someone would start exposing the ludicrous nature of charging people for their state sanctioned torture. When our private insurance rejected our daughters year of forced detainment at the state hospital as “medically unecessary” and refused to pick up the bill, my 20 year old, no longer a minor, was charged $150,000 for her care, upon discharge. I remember a state bureaucrat from the billing office of the hospital calling me to tell me that if my daughter didnt pay the bill, that a lien against all her future earnings and property would be placed on her for life by the state. After a social worker enrolled her in Obamacare, future hospitalizations would be at the tax payers expense. All told, private insurance and the taxpayer has easily paid over one million dollars for my daughters ‘treatment’ with nothing to show except that she is addicted to neuroleptics that keep her perpetually infantile and unable to fulfill her potential plus she has acquired a deep fear and mistrust of anyone who works for the carceral mental health system or in anyway makes profit from her suffering, including peer workers. Yesterday, I located a bill for in-patient services my daughter received at an acute, private psychiatric ‘hospital’s. The cost for being deeply traumatized there for less than one month? $190,000. Its scandalous

Report comment

That’s shocking!

Same thing happened to me, although a bit cheaper. I got a 4500 Dollar bill for a 10 day involuntary hospitalization. That was for a nervous breakdown as of a bullying situation at work and sleepless nights of stress and worry.

I never paid that bill, but left the country. (It was in Australia and my visa depended on my employer anyhow.)

Needless to say, the stay was traumatizing. Nobody talked to me, they did not believe me etc.

That’s 14 years ago, I am fine since.

Report comment

This is disgusting: it is like charging prisoners for upkeep, education and any help they get while they are in prison and expecting them to pay it back when they leave out of any earnings they get.

Why not have kidnappers who forcibly drug the people they kidnap demand money from there victims for upkeep too?

Perverse or what?

When does the rebellion begin?

Report comment

Great comment!

Report comment

I find it ironic that one of the things health care providers emphasize to the “patient” is to keep stress levels at a minimum to stay mentally healthy and then they load them down with hospital bills for involuntary commitments, traumatic hospitalizations, send them home on provisional discharges with threats of rehospitalization if they “screw up”, court procedures that are a sham, medications with side effects such as anxiety, stigma, to name a few. With no crimes committed, except to attempt to get off their toxins, they are treated as criminals on parole. I’m fed up with this corrupt system.

Report comment

Me too!

Report comment

It is no more corrupt than the system is serves, which it does swimmingly well.

Report comment

I believe Will Hall mentions in one of his articles the “involuntary treatment” he had at a particular hospital – which ended as soon as his insurance money ran out.

Report comment

I totally agree, “Billing Psychiatric Patients for Involuntary Treatment is Unethical.”

“the high cost of inpatient stays that averaged just over $7,000 for about a week of treatment.” I was involuntary treated twice. The first time was for two weeks, at a cost to my private insurance company of $30,000. I was held by this now FBI convicted criminal doctor, and his psycho psychiatric “snowing” partner in crime, for a non-existent “chronic airway obstruction,” which is NOT even a “mental illness.” Thus, it was, in fact, an illegal forced psychiatric treatment.

https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndil/pr/oak-brook-doctor-convicted-kickback-scheme-sacred-heart-hospital

“Psychiatric patients’ vulnerability, combined with the coercive nature of involuntary care, could also foster outright exploitation.”

Indeed, it does. The second time I was forced treated was due to the fact, I eventually learned from health insurance companies, that that psycho psychiatrist had been erroneously and illegally listing me as her “out patient,” at a hospital I’d never been to, for years.

I was able to get the hospital that had given me an unwanted $5000 physical, resulting in a “medically clear” diagnosis – because I had been lying in a public park, looking at the clouds, trying to mentally come to grips with the staggering in scope medical betrayal I’d dealt with, after finding the medical proof that the antidepressants and antipsychotics can create psychosis, via anticholinergic toxidrome – to drop the charges. Since I had politely refused medical care, and NOT signed HIPPA forms. Yet I was inexplicably, in the middle of the night, shipped – a long distance – back to that very same psycho psychiatrist. Obviously, that hospital had illegally broken the HIPPA laws.

I didn’t have insurance at the time, so I don’t know what the state was charged for that psycho psychiatrist’s second, medically unneeded, and illegal, forced “treatment,” this time for a non-existent “UTI,” but this is also NOT a “mental illness.”

Definitely stealing from, bankrupting, and defaming – in every way possible – is the goal of the child abuse covering up psychiatric and psychological industries.

Report comment

When my daughter lost her boyfriend to an epileptic seizure during college, her school psychologist asked her a series of leading questions, almost luring her into admitting she “didn’t know if she wanted to live.” Thereupon, the psychologist called campus security and they dragged her away to the psych ward at a local hospital–already traumatized by grief–and forced her to endure 6 hours of invasive, dehumanizing assessments…until she was released by a psychiatrist who (amazingly) said nothing was wrong with her, and she should file a formal complaint against the psychologist. Before she was allowed to leave the ER, she was forced to pay $350 for the privilege of being tortured. It cleaned out her bank account. She spent the next two weeks at home with me, crying her heart out–without any other grief support, or so-called “therapy” whatsoever. All she needed for was someone to listen to her, and acknowledge her pain. Six years later, when she faced a genuine suicidal crisis, she never even saw a counselor. Because she knew that no one would actually help her. Instead, she just killed herself. Back when she was in college, even as her father, I was treated like some kind of monster for demanding to know who would pay for this incarceration against my daughter’s will. They acted like even mentioning money was reprehensible. I said, “If you’re going to hold her against her will, then you should pay for it. What the hell is wrong with you?” So, yeah, think of the harm that that little $350 charge caused six years later. She told me after that brief hospitalization that she felt betrayed and deceived by her supposed “helping” professional. I don’t think she ever trusted another mental health provider. In the end, there was no one to turn to. And as a therapist myself, I have had patients held against their will and forced to pay thousands of dollars, with literally nothing to show for it except trauma upon trauma. If “we” think they’re dangerous, then “we” should pay to protect us (and them) from themselves–just like prison. We don’t hand prisoners a surprise invoice for services upon their discharge, do we? And we wonder why people don’t “get help.” It’s way past time for those who still believe involuntary incarceration is necessary to suck it up and pay for it themselves, or stop it altogether. Our present system is unconscionable.

Report comment

Heartbreaking. Seriously what is it going to take for all of this to finally stop?!

Report comment

The idea that the MERE SUSPICION, that someone MIGHT commit harm to themselves or others, or that their observed behavior MIGHT POSSIBLY be due to the effects of mental illness (even in situations where a physical illness is just as, if not more, likely), is considered sufficient grounds for a medical professional to rescind the protections afforded them by the constitution of the United States, is totally and completely, 100%, absurd; in my perhaps not so humble opinion.

Report comment

But is the average person under the same suspicious focus?

There are lots of “normal” people in the society I live in that might quickly resort to violence, that roam around freely.

Report comment

Excellent point!

Report comment

It would be one thing if experiences such as mine, and those recounted here, and on Mad in America as a whole, on the r/antipsychiatry Subreddit, Power2u.org, Mindfreedom.org, and all across the psychiatric survivors movement, were atypical. However, it is readily and unarguably, IMO, apparent that this is not the case. As Edmund Burke wisely noted, “ The Only Thing Necessary for the Triumph of Evil is that Good Men Sit Back and Do Nothing.” I would say that pretty much accurately describes the entire medical, psychiatric, and psychological professions. Anyone of whom, is in a much better position than any one, or even all of us as a whole, who speak as we do in one voice, and have done, since Elizabeth Parsons Ware Packard first started the movement in 1868, followed by Rosenhan’s Experiment over 100 years later, that convincingly demonstrated that glaring inadequacies existed within the regime, especially in regard to cognitive bias. No different from that which plagues our judicial system, such that a white judge decides guilt or innocence, the moment the accused is brought in, based solely on age and on the color of their skin. Those ‘Good Men and Women,’ then, by any reckoning, have become complicit. For as we are all, no doubt, by now aware, “What You Allow, You Teach.”

Report comment

Hi Kristen — MIA is not an anti-psychiatry site, nor are some others which are often seen as such yet specify the opposite when asked, saying they want to “abolish” forced psychiatry but not psychiatry itself, which is ultimately a short-sighted approach.

The is real survivor-based AP organizing starting to take place however, and if you’d like us to fill you in we’ll be glad to do so — do you have a public email or something?

Report comment

[email protected]

Report comment

Neat. You can delete it now (or the moderator will if you ask) if you don’t want the whole world to have it — we do!

Report comment

OK, I see in retrospect that you might want to reexamine the entire concept of “mental illness.” Szasz.com would be a good place to start.

Report comment

Psychiatry is a pseudoscience, a drug racket, and a means of social control. It’s 21st Century Phrenology, with potent neuro-toxins. Psychiatry has done, and continues to do, FAR MORE HARM than good. The DSM is in fact a catalog of billing codes. Everything in it was either invented or created, nothing was invented. So-called “mental illnesses” are as “real” as presents from Santa Claus, but NOT more real.

Seen as a whole, psychiatry is a form of genocide…..

Genocide for profit….

Report comment

I have been hospitalized six times – four were “involuntary”, the other two were coerced (ie, “you can either check yourself in or else I will commit you”). The first five incarcerations occurred when I was much less “stable” and more vulnerable, and I ended up paying for those after threats of legal action on the part of the hospitals. The last time (maybe 6 years ago), was precipitated by the culmination of stressful events which I decided to alleviate with alcohol, an illegally obtained anti-anxiety pill and a call to a “mental health” hotline who kindly sent a very young social worker to my house to assess me. She was convinced I needed to go immediately to the hospital and called the police to assist with that. I refused, the police left, and she was very angry.

I went to bed, got dressed in the morning and went to work. She got dressed in the morning and got a court order for my arrest. The police showed up at my work, put me in handcuffs and I was incarcerated in a facility 100 miles away from my home for 7 days. Because I was stone cold sober, relatively compliant and on a ward that was primarily for drug addiction rather than the severely “mentally ill” (that unit was full), I was not forced to take any medication (although it was “Strongly Recommended”) nor was I physically restrained at any time (other than not being allowed to leave).

I had no change of clothes and refused to wear a gown (again, relatively compliant – thankfully it was “casual Friday” when I was taken) and I was denied access to my cell phone. There was a “patient” phone in the commons room but (show of hands) who has their contacts phone numbers memorized? On Day 5, the court appointed attorney was making his rounds and I managed to grab him. I wasn’t on his list “yet” and he confirmed that because I had Very Good Insurance®, it was possible they would try to keep me for the legally allowed duration. He promised to check into it but was only scheduled to see folks once a week and, again, I wasn’t on his list yet. I guess he managed to talk to someone, because I was released two days later without a court hearing.

About a month later, I received the bill. My insurance had covered most of the stay, but there was a $4500.00 outstanding balance not covered by insurance. Rather than trying to argue with their billing office, I wrote them a letter, outlining the circumstancing leading up to my “stay” and then bullet pointing all of the legal and ethical violations that occurred while I was there (there were many). I told them I would love to argue with them over this in court and looked forward to hearing from them. Other than a call from their billing office prior to them receiving the letter, I never heard from them again.

I did try to get the insurance company to not pay them, but being “certified” as crazy, they weren’t interested in speaking with me about it and I was too tired to pursue it further.

Report comment

Well done!!! Thanks for sharing that story – you sound like a very capable advocate!

Report comment

Maybe now…not so much for the initial incarcerations. For a long time I still believed that the psychiatric system had something to offer, that I was somehow flawed because it wasn’t working for me (the drugs didn’t work, the therapy didn’t work). It took an internal paradigm shift to lift the scales from my eyes. While I wasted a lot of years, I feel very lucky that the side effects and/or lack of efficacy of the drugs made me stop taking them – usually within a couple of months (sometimes less) of them being prescribed (and also added a label of “non-compliant” to my long list of labels).

Report comment

Advocacy skills are often learned through harsh necessity!

Report comment

szasz, of course, is correct; involuntary acts of psychiatry must be outlawed

as a side note, the for profit confinement centers are notorious for whole new levels of fraud and deception. the cchr has been involved in a number of cases in the US, one of which shuttered a number of for profit ‘facilities.’

until psychiatry — ‘voluntary’ and involuntary — can be abolished, educating the public is probably the best way to protect more people. educating people on the enormous costs of psychiatry and friends, along with the incredible amounts of suffering caused by the industry, would probably be a good step. 🙂

Report comment

And a step they’re gearing up to squelch, including social media bans on “false information.”

Report comment

I guess the only thing I would add is that we need to learn not to be shocked when details about the system’s viciousness are revealed. Such a reaction reflects a potentially dangerous naivete, as when predictable “emergencies” pop up we need to have the ability to calmly and methodically educate people about what to expect and how to respond.

When it is understood that the function of psychiatry is not to “help” people but control them everything else becomes more clear.

Report comment

I agree. Response #1: Don’t Panic! Calm yourself down, and then carry on. Just as if you suddenly found yourself man overboard because someone (that’d be me) forgot to rise the darn keel again. Only this time you’re surrounded by 2 foot waves. Response #2, then, I suppose, is always remember to don your life jacket, especially whenever (and before) you find yourself headed for rough water. Do you have a health proxy? One that you TRULY trust? Are you carrying a document that will effectively convince the hospital that this person is in fact your health proxy? What about any relevant medical records that might otherwise explain inexplicable behavior? (In my case the radiologist’s report and a website and password granting access to images related to the Cavernoma in my brain.) Given the “reality of the system’s viciousness,” as the commenter above wisely noted, it’s certainly best to be prepared.

Report comment

I made an appointment to see a social worker at a free clinic, for assistance to severe lingering legal and financial entanglements with my violent parents.

She told me she wanted me to go stay “somewhere safe” and we would talk again tomorrow. She gave me her number “just in case”. I thought I was going to a shelter.

When the psych ward doors shut behind me and my belongings were taken away, a psychiatrist came in to see me. The first thing he asked me was what insurance I have. Confused, I said I was coming from the free clinic.

This agitated him. He told me medical care isn’t free, they need my insurance information. I said I was covered under my parents’ insurance, one of the things I needed help severing ties with, and in the meantime I can pay out of pocket.

This enraged him. “Call your daddy, YOU NEED TO CALL YOUR DADDY”. I stood up and informed him I will be leaving. He told me I could not. This was when I learned that I had been involuntarily committed. Confused, I asked “what do you mean?”.

He became apoplectic. “You think this kind of thing is cheap? They are going to send you upstairs, it’s over a thousand dollars a night. You think you can dodge this? We will garnish your wages, we will garnish your student loans payments, CALL YOUR DADDY.”

I screamed for a nurse then invoked my entitlement to a printed copy of patient’s rights, the only piece of legal knowledge I had of the system at the time.

I called the social worker the next morning and she did not answer. Later I asked the head nurse to call for me. She could not reach her either. I asked the psychiatry intern to call the social worker. He informed me she had gone on vacation.

Based on this behavior, I was diagnosed with psychosis, paranoid delusions, and borderline personality disorder.

Report comment

Holy crap! How could anyone “heal” in such an environment???!!

Report comment