The website of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) indicates that mental illness “is a medical condition, just like heart disease or diabetes.” The ubiquitous acceptance of this narrative has generated blockbuster profits for pharmaceutical companies, but has led entire populations of patients to become disempowered, self-loathing, and overmedicated. Patients have long been manipulated into accepting identities defined by ambiguous assessment criteria. Losing the ability to challenge their own treatment protocols, individuals remain imprisoned by false ideologies.

Trapped in a faulty treatment paradigm for decades, I began to critically examine how these labels had shaped my life.

As a child, at the start of ninth grade I found myself at the epicenter of rumors and bullying. I started to abandon all my efforts to fit in. I never told my teachers or my parents about the daily harassment. All the popular kids would hang out in the school lounge, which seemed unofficially always reserved for their group. I found myself attracted to friendships with individuals who were like-minded about not adhering to the stifling school rules. We’d frequently sneak off campus to walk to the mall or hide away in the woods. On a cold afternoon, a friend pulled out a pack of Newports and a lighter. I had no idea how to smoke a cigarette at 13 years old, but I was proud of my rebellious accomplishments, and apathetic about my academic ones. My window of opportunity to continue this behavior was closing, however. The class dean had set up a meeting with me. He wanted to discuss my academic performance.

I could already envision the tone set to this dreaded conversation as I saw my transcript lying neatly on the table in the dean’s office. I picked up the chair adjacent to him and moved it back about three spaces before placing it back down again. I wanted to give myself enough distance from this man who did not seem to have my best interests in mind. From the start, there were no niceties exchanged on his end as he quickly started reading out my grades to me. He began interrogating me as to why my grades were slipping. This appeared to be a full-fledged attack, and I started sobbing. Choking down tears, I mustered my reply, “I don’t know!” I stammered, “I just… I, I cannot handle the course load, I am not stupid, I just…….”

He found an opportunity to cut me off and interjected his own insights. “Rose, you seem really down, do you feel depressed?” he asked.

I turned my face away from him as I unsuccessfully wiped away free-flowing tears from my face.

“Well,” he continued, “It looks like I have struck a nerve.”

I felt horrified and my eyes started to dart toward the exit door. Despite my obvious state of despair, he pressed on with his agenda.

“I think you should meet with the school psychologist, Dr. O. How about I set up a meeting for you to talk with her next week?”

“NO!” I shouted back through my tears. “I am not seeing a psychologist. I am not talking to her, I refuse.”

I stood up and left his office, leaving a look of discontent on his face. Although he went against my wishes and still set up a meeting with Dr. O, I never showed up to the appointment. While I was suffering from mental anguish, I never experienced much desire or need to get help for this issue. I wanted to embrace all my emotions on my own, even the most painful ones.

I managed to get through my sophomore and junior years mostly unscathed, and even began to feel comfortable in my own skin. But toward the end of my junior year, I became painfully aware that my older friends would all be graduating and leaving for college that summer. There would be no one to have lunch with anymore. During my senior year, I would go to the dining hall during lunch hour and quickly make myself a sandwich at the salad bar, then eat half as I walked back to the main campus; the other half would get thrown into the trash along the way. I was painfully unaware that one event, on a particular evening, would soon dictate the course of my life for nearly the next two decades.

Nausea

I remember feelings of complete terror as my heart rate accelerated at unprecedented speeds. I looked down at the ground beneath me, which appeared to melt underneath my feet. The chain reaction of physiological effects within my body and mind were unstoppable. I was an outside observer to the whole process, and there was nothing I could do to stop the inevitable. I was having a panic attack.

I saw a psychiatrist who initially diagnosed me with panic disorder and prescribed Zoloft, which caused brain zaps, extreme nausea and cognitive impairment so severe that I could not respond to simple instructions (I detail these experiences in a previous story here). In a few months, I would subsequently be told that I had “Major Depressive Disorder,” a diagnosis that broke down my spirit even further. I cried my way through every session with my therapist, mostly after detailing my new pronounced states of depersonalization, physical pain, and complete hopelessness. When my one diagnosis had multiplied into two, I accepted my fate of being ill. I extrapolated these disorders further: I consciously identified myself as a damaged individual. This perceived state of being would haunt me over the next decade. I wanted to disappear. While the idea of dying started to feel like a wise and logical escape, these ideations also felt foreign and intrusive. I was horrified by the thoughts that my mind had now become capable of.

I continued to take my prescribed Klonopin for the next six months as my tolerance withdrawal to benzodiazepines became further pronounced. One evening, I decided to take a hot bath to try and calm down my physical pain. I couldn’t seem to sense how hot the water was, so I tested it with my foot under the running faucet. However, it was as if my internal barometer for temperature and pain had been switched off. The next morning, I sat silently in my senior-level philosophy class. My classmates appeared carefree and comfortable. I felt like my brain had been processed through a high-powered blender. I started to squirm at my desk as feelings of inner restlessness began to consume me. It was cumbersome to sit still, as I had developed a mild form of akathisia. I would identify small pockets of time during lectures where I could dash out of the classroom. I desperately needed to rid myself of the inevitable movement that I could no longer control.

Upon graduating, my philosophy teacher gifted me a copy of Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre. I lay in bed at night, sincerely hoping that I would not make it to see the morning. I was not scared to die; I was scared to keep living. After the commencement ceremony, students in the graduating class left on beach trips for senior week. Meanwhile, I could barely hang on to the next moment. Feeling dizzy and disoriented after taking my prescribed Klonopin dose, I made my way to a relatable passage in the text:

“And I too wanted to be. That is all I wanted; and this is the last word. At the bottom of all these attempts which seemed without bounds, I find the same desire again: to drive existence out of me, to rid the passing moments of their fat, to twist them, dry them, purify myself, harden myself, to give back at last the sharp, precise sound of a saxophone note. That could even make an apologue: there was a poor man who got in the wrong world.”

Tic-Talk

After dropping out from my initial semester of coursework in the fall, I was excited to return to college in the spring semester as an ambitious biochemistry major. I thought I had achieved some stability from what I now know to be iatrogenic injury from benzodiazepines. I threw myself into my coursework, putting a lot of pressure on myself to succeed and not stopping to consider whether my newly injured nervous system could handle this level of stress.

I woke up early one morning in my dorm room, trying to gather my thoughts and get myself ready for my organic chemistry lecture. I washed my face, brushed my teeth, and frantically searched for my textbooks. I stopped suddenly and gasped for air as the left side of my head started to buzz, reminiscent of the brain zaps that had abated for several months now. I felt as though someone had turned the volume up from 3 to 100 in my head and my thoughts were too loud to bear. The left portion of my brain felt highly pressurized, and I was in a great deal of pain. The head pressure became so severe that I believed I was having a stroke. I began to quietly repeat out loud the thoughts that were repeating inside my head.

Despite my best efforts to suppress these vocalizations, my phonic tics would eventually erupt into full-blown klazomania (compulsive shouting). I realized that I needed a solid plan to make sure that no one would notice. When my symptoms escalated, I would go for a drive in my car and turn the radio on full blast. On the surface, I likely appeared to be singing along to the music, but I was desperately hanging on to reality as my brain was working completely against me. I was shouting my thoughts at full volume while trying to safely navigate traffic. I could not make sense of anything that was happening in those moments, and neither could any of my doctors. The only options I was ever presented with were more medication.

I maintained every effort to appear normal. I worked diligently to remain articulate during conversations with others. I committed to finishing my undergraduate degree, as well as applying to various graduate programs. Deep down, I was completely exhausted and overwhelmed, harboring intense feelings of both depersonalization and derealization. The heavy doses of trazodone and Klonopin caused a severe loss of inhibition and I felt a dangerous sense of apathy toward my well-being. I started drinking heavily to try and regain any sort of emotion. I was neither happy nor sad; I accepted my bleak existence in my heavily medicated state.

I would soon come to find that drinking only helped my symptoms temporarily. In my intoxicated state, I could sense a glass barrier between myself and the rest of the students. I felt vulnerable and isolated, an easy target for strangers who were eager to feign interest in my well-being. With multiple diagnoses and a stack of pills in my bedside drawer, I never developed any self-worth. The only identity I was presented with by each clinician was that of a sick individual.

I started staying up late at night in my dorm room, experiencing a sense of complete disconnection from myself and the world around me. I took a razor blade to my skin in a futile attempt to bring myself back into reality, rationalizing that if I saw my own blood, my brain might slowly form a connection back to my body. I had no such luck, and was left with the task of cleaning up my self-inflicted wound. I detailed all my actions to my psychologist, who judged me quite harshly. I decided not to mention any future incidents of self-injury to her. My psychiatrist increased my trazodone dose so high that my sleep began to resemble a medically induced coma. The medication had also started to dry out my throat; I would frequently need to spit out my water in the mornings, as the small amount of liquid would cause me to choke.

OCD & Me

I found myself slouched in an uncomfortable armchair across from a licensed therapist. His office was in an old and musty building adjacent to a private psychiatric hospital. I detailed all my symptoms to the best of my ability, and he confidently nodded his head as he scribbled away on his notepad. He handed me a short assessment titled “Y-BOCS” (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale). I started quickly filling up the little bubbles, taking note of how vague and repetitive each question was. I felt myself growing angry; this exercise was cutting into our therapy session. I felt a sense of distress as I handed the assessment back over to him, completely unprepared for what would come next. The therapist scored my answer sheet and nonchalantly announced that I had scored moderate-severe for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

I felt disappointment and anguish as I settled into this new label. My self-reflection was interrupted as the therapist started to lecture me about various methods of treatment, namely exposure response prevention (ERP). I decided to attend a three-day International OCD Federation conference that summer, to learn more about my condition. I met with leading professionals and learned about different avenues for treatment. I noticed that every professional portrayed my illness as a chronic condition. My heart sank. If this were indeed true, could I ever go on to lead a normal life?

I began to attend therapy at a local treatment center, one that was highly specialized for OCD. During group sessions, I looked around the room at all the other patients who shared my diagnosis. I wanted to identify someone who was getting better with the treatment protocol, but I could not. I made sure to ask the other group members questions about the medications they were taking; I still had hope that I could somehow get to the bottom of a “cure.” Many individuals told me they believed that the medication was helping them. Upon further questioning, I learned that they were all experiencing significant side effects. Overall, they did not feel that their baseline symptoms had improved much.

A psychologist led the group session every week, offering professional conjectures based on experiences shared by the patients. On a particular night, one young woman shared that she felt nervous every time her husband was out late with his friends. She felt consumed with worry that he might drink too much and get into a car accident. This seemed like a perfectly reasonable concern to me. However, the psychologist provided a detailed explanation of how her thought process was flawed due to her pathology. I began internally questioning why these seemingly normal attitudes and behaviors were indicative of illness. But I was still heavily indoctrinated into the concept that I was mentally ill.

I could feel integral layers of my existence evaporating during each therapy session. I was internally screaming into a void that felt boundless. My psychologist encouraged me to keep engaging in the exposure response prevention exercises during my free time. I told her that the exercises made me feel disassociated, terrified, and hopeless. Nevertheless, she insisted that this was the gold standard of treatment. I felt infantilized. She stated that if I did not continue this treatment, I could never expect to recover. The power dynamic was locked: I was the patient with intrusive thoughts, and she was the expert psychologist. Any input that I provided would always be deemed erroneous by her standards.

After much research, I found a top-rated intensive outpatient program for OCD in Houston, Texas. I felt naively confident that this program would work. The flight to Houston was a bit nerve-wracking, but I soon settled into my new environment upon arrival. The next morning, I made my way into the treatment clinic. The clinic was located inside of a large Mediterranean-style house, with a handful of bedrooms for patients who chose to reside on-site during treatment. After completing my check-in, I was greeted by an intimate group of patients and counselors. Every morning we were asked how willing we were to “lean in to our OCD” and provide a score from 1-10. Next, we would meet as a group in a small classroom. One of the staff psychologists would lead a group exercise, ranging from coping techniques to group discussions of various symptoms. From there, we were free to complete our exposure response prevention exercises on our own, or any other task that was deemed appropriate for our healing.

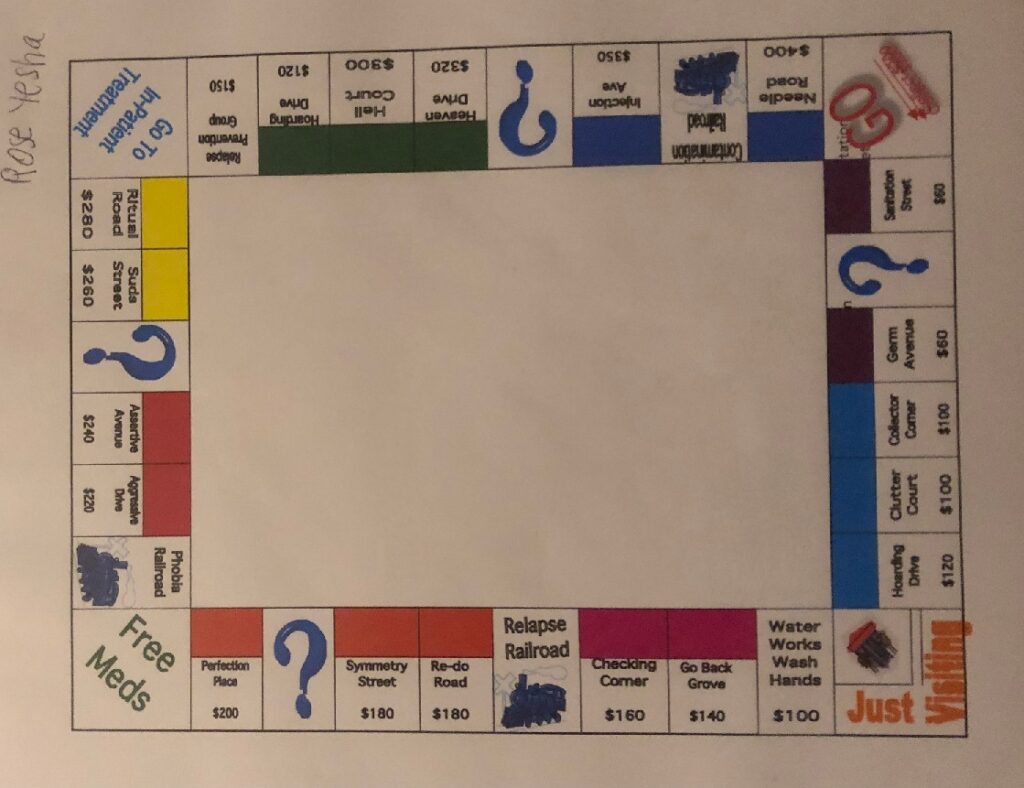

At night, I would flip through the seemingly endless material on my condition that I received each day. This material seemed very clinical and lacked any relatable perspectives on suffering. I stared at the monopoly board of symptoms on my binder, unsure of how I felt about my symptoms being reduced to a children’s game. This whole treatment modality felt bizarre, and I started feeling more hopeless. I took my prescribed Ambien every night to go to sleep. I questioned whether I should be taking it, but I did as I was instructed.

The next morning, I waited outside my hotel for my Uber driver to arrive. With past drivers, I would typically lie if they asked me questions about my destination—since the clinic did not have any obvious identifying markers in the neighborhood, I usually said I was going to a friend’s house. My driver pulled up and I anxiously took a seat in the back of the car. I hated being driven by strangers and it filled me with dread. Luckily, this driver seemed friendly, and he quickly engaged me in lighthearted conversation. He inquired where I was headed to and I started to gulp down my hesitation. I bravely responded to his question: “I am going to a treatment program for obsessive-compulsive disorder. I never had these symptoms before I started psychiatric medication.”

To my surprise, he did not seem fazed. His voice filled with sadness as he told me that he had taken Effexor in the past for depression. I caught his reflection in the rearview mirror as he became more emotional. His next sentence was haunting: “This medication almost cost me my life.”

The air grew silent, aside from my nervous breathing and the car horns blaring around us. I asked him how long it had taken him to regain a sense of normalcy. After breathing a heavy sigh, he answered, “I really don’t know. Rose, it seemed like an eternity… I felt horrible for at least several years. I also had these debilitating headaches that seemed to never end. I am so thankful that I don’t get them anymore.” He then patiently proceeded to give me suggestions on how to plan a slow taper and mentioned a few supplements that eased his symptoms. This brief encounter would serve as the most important experience that I had during my stay in Houston. As he made the last turn into the clinic, I felt a sense of sadness that our conversation was ending. I thanked him for sharing his story with me and made my way into my morning session. I learned more from a stranger in ten minutes than I did in three weeks at a top-rated OCD center.

I completed the usual morning exercises with the group, feeling foggy from the Ambien I had taken the night before. I was paired with a psychology intern, and mentioned to her that I was in severe pain. She looked puzzled, so I asked her if she knew what brain zaps were. I tried to explain the condition to her but she appeared largely disinterested. It was clear that no one believed me. Eventually my pain let up and I was paired with a different intern later in the day; I felt dismayed by the incessant shuffling between different practitioners. The intern asked me to write a letter for my exposure prevention response exercise, detailing what I thought would happen if my obsessive thoughts never went away. Tears poured down my face as I detailed my every worst fear, including never getting better and continuing to live my life in fear and isolation. She did not comfort me even once but did praise me for getting through the exercise.

I felt completely traumatized by the whole event, and I decided to quit the program prematurely. If medication and therapy were so effective, why did I only feel worse? After over a decade of receiving multiple diagnoses, I felt broken. I started to abandon my identity of a mentally ill patient, a label that I had first been presented with as a teenager.

The End of a Diagnostic Area: Breaking with Disorder

As an undergraduate psychology major, most of my coursework centered upon the concept that continued states of mental anguish were all diagnosable conditions of mental illness. “Depression is the common cold of psychiatry. Schizophrenia is the cancer,” one professor would continuously assert during lectures on psychopathology. After my personal experience in the mental health system, I feel vastly betrayed by this portrayal of human suffering. With each subsequent DSM publication, reductionist labels have now become applicable to every facet of daily existence. The definitions for “abnormal” behavior have navigated both patients and practitioners away from practical solutions. Instead, constructs of conventional mental health treatment have steered into a dangerous territory of exploitative labeling.

As a highly sensitive individual, it was difficult to effectively process my environment at an early age, and at times this caused me states of extreme distress and sadness. However, I also feel that I could have been able to handle these reactions with the proper outlets of support. The autonomy over my own identify was stolen from me within the fleeting moments of receiving my first diagnostic label. After my initial panic attack, I questioned my existence and felt disassociated from my identity. To qualify this type of thinking as a disorder is to fundamentally rid society of any deviation from what is considered “normal.” I do not believe that natural reactions to grief, trauma, and stress are indications of illness. Furthermore, psychosis could better be defined as a psychospiritual struggle that requires compassion rather than involuntary punishment. Eradicating an individual’s right to make decisions for their own recovery is inhumane. I am just one example of an individual who has been largely failed by the conventional mental health system. The systemic failure to provide a more sound and humanistic approach to suffering has led to deplorable outcomes in the previous decades for millions across the globe.

In 2020, I was extremely fortunate to see a physician who diagnosed me with an iatrogenic injury from benzodiazepines. I had endured virtually two decades with dozens of clinicians insisting that psychotropics played no role in my continued list of unexplained health conditions. This was the first time I had encountered a psychiatrist who did not provide me with a diagnostic code for mental illness, but instead, a clear explanation that I had been harmed by psychotropic drugs.

An onslaught of questions started to flood through my mind. Who would I have been if I had never been diagnosed? What if I had never taken psychiatric drugs? My mind started to unravel at all the possibilities and my identity felt at odds with this new discovery. How was I supposed to move forward with this knowledge? I scoured multiple support group forums in the layperson community to develop a medication taper plan. This continues to be a long and arduous process, but I feel determined to become unmedicated. I am still in the process of grieving for all the years I spent suffering, adhering to the false paradigm of disorder. Labels that perpetuated a construct of falsehoods that I would never be successful. Labels that led me to engage in self-destructive behaviors. These labels left me docile to a broken mental health system—a carceral system that viewed me interchangeably as a patient or an object, but never a person.

A prominent Scottish psychiatrist, R.D. Laing, revolutionized psychiatry with his views on mental illness. While Laing never denied the existence of mental illness, he held radical views that were in opposition to his contemporaries. Laing insisted that mental illness could be a transformative episode whereby the process of undergoing mental distress was compared to a shamanic journey. The patient, or “traveler,” could return from this journey with relevant insights, and may have become a wiser and more grounded individual as a result. I am in the process of releasing myself from all the shame, the guilt, and the fear that I have acquired throughout my experiences as a patient. I am confident with my decision to break with my diagnoses. While I believe that a diagnostic label may provide initial relief to the sufferer, there are undoubtedly severe consequences that may follow. The invisible flames of mental illness labels no longer dictate the course of my life. I have ultimately chosen to break with disorder.

Hi there, Rose.

Thank you so much for writing and posting this. As someone who was once on 22 daily medications, who is now on 1 (bc) this really hits home. I am a victim of overdiagnosis, overmedication, and being overinsured at one time.

Report comment

Hi there,

Thank you for reading my blog. I am so inspired that you were able to get off so many medications, well done! I am sorry to hear that you were a victim as well. It is a bitter reality when we are hurt by the very same people who were meant to help us.

Warmly,

Rose

Report comment

question for Rose,

Who supported you? Who were your supports?

Who emotionally supported you? Who physically supported you? Who mentally supported you? Who financially supported you? Who supported your needs?

Report comment

I’m very interested to see someone talking about OCD from an alternative lens! I would love to see more explorations on alternative ways of viewing what are labeled obsessive-compulsive doubts. I do find the way we categorize the cycle somewhat useful in understanding the significant distress my doubts cause me. I also find the way those experiences are discussed by professionals to be as unhelpful as you did.

I was lucky enough to talk to a therapist once who said he believed ERP could be “extreme.” But otherwise, I was told by another after a 5-10 minute jaunt flipping through the DSM OCD criteria that I definitely had it and that it’s a brain problem, so no wonder I was struggling. There is nothing to be done to change it besides taking meds, though she admitted that there “are no good treatments for OCD.” (She didn’t even mention ERP.) Obviously super hopeful and optimistic; just one more variation of the coercive call to view oneself as sick and to please just do what the professionals say.

Report comment

Honestly, the attitude is worse than the worst of the drugs! You come in and they tell you, “Well, your brain is broken, this has nothing to do with your decisions and/or experiences, and there’s nothing you can do about it except take drugs and hope they work for you.” Talk about discouraging!!!! And then to tell you that “there are no good treatments” to your permanent brain disease? If you wanted to induce suicidal thinking, that would be a good way to get there. Very disturbing to think that is how far our “mental health” system has sunk!

Report comment

Hi Steve.

I’ve personally, right off the bat, viewed psychiatrists as being the ones with malformed brains. The stuff they spout seems like utter madness to me.

“We’re treating the mind which is part of the brain. We know this because nobody has ever proven the location of the seat of human consciousness. ”

If the mind is purely organic then how does one explain my grandmother, near her death with advanced Alzheimer’s, becoming totally coherent and herself simply to say a final goodbye to me back in 2006?

If the brain is damaged then how come the mind can still operate at times?

Psychiatrists, practising a ‘science’ ( lol ) don’t have the answer to such things therefore those things are to be dismissed and ignored.

Columbo they are not…

Report comment

Hi Steve,

I totally agree with everything you have masterfully articulated here. It is so ridiculous that vulnerable patients are led to believe that they have a life-long brain disease. The orthodoxy of this approach is almost cult-like, with many forming entire identities around their disorders. Then organizations such as NAMI encouraging people to get mental health screenings, all the while being funded by big pharma. I can not take these popular mental health awareness months or suicide prevention days seriously. All I see is more advertisement opportunities for dangerous treatments!

-Rose

Report comment

Agree 100%. All these “awareness months” are is taxpayer-subsidized marketing opportunities!

Report comment

*Sponsored by Pfizer (written in teeny tiny letters just in case someone is able to read our legal obligation to disclose our conflict of interest)

Report comment

Hi Kalina,

Once I was first diagnosed, I pretty much reached the end of the internet in searching for answers. I talked to world-class professionals who were so called “experts”. I found that none of them had any good answers. To their credit, many of them were well intentioned, but the current research on OCD is severely lacking. Many of the experts agreed that medication did not really help, yet, most of the people I met in the support groups were taking several. I found ERP to be extreme from the start, and I had other friends who suffered intensely because of being coerced by their therapists to keep engaging in therapy that was hurting them. I feel very fortunate I was able to see my suffering from a different lens, and also finally validate that it was caused by iatrogenesis from benzodiazepines. Whatever the cause may be for obsessive thinking, intrusive thinking, compulsions, etc.- I just have not seen conventional mental health treatment help very many people. I also do not see the purpose in allowing people to believe that they will be chronically afflicted with this condition. Thank you for your comments and for reading my blog!

Warmly,

Rose

Report comment

You don’t have to break with disorder to be sane. Disorder is cool.

I remember when I first met Leonard Roy Frank. He told me that he wasn’t mentally ill.

I thought, hmm. I will have to remember that. “I’m not mentally ill.”

I tell myself again. “I’m not mentally ill.”

I hear a voice saying “I think he’s got it!” (Yeah, the rain in Spain, and that sort of thing…)

I’m not mentally ill. How about you?

They say practice makes perfect. We could fill a page with it even.

“I”m not mentally ill.”

Report comment

I totally see your point, Frank. I respect all experiences. I think mental health should be inclusive of everyone’s journey. This was the best course of action for myself. I don’t feel my sanity (or that of the next person) should ever be a question of subjective diagnostic criteria! 🙂 The way in which one chooses to define their mental distress is a personal preference.

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

Having endured multiple coercive psychiatric “interventions”, I think my best defense has become to lose the “mental illness” caricature, and to plead the case for my own personal “sanity”. (My public “insanity” can wait for the proper circumstance and audience with which to be appreciated.) However much the “mental health” authorities try to drug people into competence and responsibility, effective attitudes come from facing facts, and not persistent evasions, and continuing follies. Accepting any “mental illness” label as a bonafide “fact” is one of those traps that I’d prefer not to step into any more. Wisdom, not folly, I would expect to be the rewards of experience. Hopefully, once the same mistake is no longer habitually repeated, but fades into a dull and dismal obscurity, the light of my truth will become more apparent to all.

Report comment

They diagnosed me too with OCD after both a pencil and paper test from one psychiatrist and after being drugged from all these psychiatrists. What a Joke; a tragic painful joke! I bet that most, if not all OCD diagnoses are caused by the psychiatric drugs. However, do you know who was more obsessed than I was? My psychiatrist and therapist…They wanted details on even how I took a shower! When I was taking these psychiatric drugs, many times my brain felt raw and it felt like it was itching inside. I checked with other people in the waiting rooms of the clinic who said they had similar sensations. Luckily, these issues did go away when I stopped the drugs. Yet after probably about twenty years or so on these drugs and at times I would take maybe nine or more prescriptions (I was so drugged I can’t remember) I am much better now. I went through withdrawal and now I consider myself in the adaptation phase. Each day is a learning experience. Each day, I relearn the old me and relearn the new me; but I have at least ten or more years, that I msut sadly consider “lost years” with very few memories. Thank you.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your story, Rebel. It was not until I found the support groups that I realized how common intrusive thoughts were in psychiatric drug withdrawal. I had debated this idea with several psychologists and of course none of them believed that my condition had anything to do with the medication. I remember mentioning Dr. Peter Breggin to my last OCD “specialist” and he told me that he felt Dr. Breggin was controversial. That is when I knew I was in the wrong place and I quit OCD therapy for good. I am slowly healing, as you said, it is more of an adaptation at this point! It is hard to reckon with the lost years, but I am still grateful that there is a future ahead. Thanks for reading!

Warmly,

Rose

Report comment

Hi Rose.

Personally I knew the psychiatrists were talking utter rubbish as soon as they opened their mouth.

People keep saying to me “respect the experts” etc…

Of course I will…if experts ever show up. Personally I question anyone’s intelligence that spends years studying in college and doesn’t realise they are engaging in a ‘speciality’ that is complete nonsense.

The hubris of those people to assume what is going on in my mind and then restrict my life based on that.

If you don’t fit into their preconceived notions they’ll make bloody sure to hammer you into them. Such a science huh?

Report comment

Yes, it is astonishing to claim to have the ability to know the inner workings of one’s mind. I think we would all be safer running off to the nearest fortune teller. Many professionals would like to believe that they hold prophetic abilities, perhaps they should investigate if that belief is indicative of pathology? 😉

Report comment

More like “pathetic abilities!”

Report comment

I fully AGREE!

It is TOTALLY absurd for ANYONE to proclaim that they have KNOWLEDGE of the workings of ANYONE’S MIND. In my comments in Mad In America THIS above ALL ELSE has been my clarion call.

I have no business telling ANY other person that they HAVE a mental illness like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia as I simply DO NOT KNOW THAT REALITY about the interior of their mind, which is THEIR mind.

SO EQUALLY NO separate person from me has the right to say they KNOW that I do not have what I KNOW from inside the INTERIOR of MY MIND I DO HAVE, which is MY SCHIZOPHRENIA.

In a hypothetical setting someone may want to bully me by saying that the term schizophrenia was only invented in 1878 or whenever. But prior to this THE SAME DIS-EASE would have been called SOMETHING ELSE, maybe many different exotic names in different cultures, like “blufgyitag” or “qbabybabybaby” or “proudfgcproud” or whatever. Something equally cheerfully unpronouncible. Epilepsy used to be called FALLING DOWN SICKNESS before some posh doctor called it what every epileptic calls it today. So merely citing that the term for an illness got an upgrade does not prove it has not ALWAYS EXISTED.

Anyone would be a fortune teller if they keep CLAIMING that since the source of the illness of schizophrenia has not been located or understood this must lead to the sweeping conclusion that it does not have any credence as a real illness.

How DARE any such person invalidate ANYONE’s interior MIND EXPERIENCE, be that an experience of trauma or compulsion or social upheaval or phobia or anxiety or drug withdrawal or suicide or bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

What goes on in my mind…MY MIND…is for ME to decide!!!!!

IF everyone had that emblazoned on a tee shirt the world would be BLISSFUL.

I am saying inside MY MIND IS SCHIZOPHRENIA.

HAS this ILLNESS been appallingly and barbarically treated? Along with most other mental conditions? YES.

But so was PREGNANCY back in the year 1436. Just because lousy treatment once visited someone in their hour of desperate need does not mean one woman has to stop calling herself “pregnant” or “with child”. That said, in these bizarre linguistically bullying times we are all uterus havers, even long distance truckers. Language is being DICTATED just like it is in school bullying. The little kid in the corner of the playground gets a slap everytime they say they lost their marbles.

I honestly feel MIA comments should pull back from the business of telling OTHER PRIVATE INTERIOR MINDS what they profess to be going on in such said MINDS.

For THIS is where it is AT globally right now in all sorts of other campaigns that are getting STUCK in linguistics. When those othet campaigns bullyingly keep telling ANYONE…

“who you really are”…or

“what’s really wrong with you”…or

“what’s really going on in your mind”…

That is CONTROLLING BEHvIOUR.

Why are people controlling?

F

E

A

R

This lengthy comment is not at all about critiquing this marvellous and beautiful blog. I celebrate when people articulate ANY emotional experience and treatment preference. What I am against is that this is THE ONLY narrative on MIA comments. By definiton any group that has an “ONLY US” narrative is excluding a sense of “THEM”. And when that occurs it can be a short step away from playground politics.

I feel MIA should aspire to GREATNESS. But the thing about GREATNESS in any walk of life is in order to be deserving of it you have to constantly LET IT GO. By that I mean you have to loosen the metaphorical ecclesiastical fortress walls that prop up the “US” and “THEM” division. This ghastly division seems to have been what ROBERT WHITAKER met when he was just starting out and very much a “THEM” to psychiatrty’s “US”. He seemed to know there was a big problem in THAT sort of “US/THEM” groupthink. But psychiatry could not bear to LET GO of its GREATNESS enough to have humility enough to hear him. The honey pot temptation of GREATNESS is that it starts to enshrine an exculsive collective ego identity more than its original vision of helping people, as was seen in psychiatry. So the pain of LETTING GO of GREATNESS is LETTING GO of adherence to the ego identity that streams through belonging to any paricular group or cult. To aspire to GREATNESS means LETTING GO of belonging to ANY GROUP. All the renegade doctors and whistleblowers and journalists have this LETTING GO of GREATNESS quality, in order to stop the “US” and “THEM”.

And by doing so they truly do SHINE in BENEVOLENT GREATNESS.

Inclusivity is not about squashing different zoo animals into a Noah Ark. Inclusivity is about GIVING UP YOUR SENSE OF “US”.

For so long as you are wrapping that mink coat feeling cosy sense of “US” around you, you are leaving your bretheren shivering.

ANY campaign that will not LET GO of its GREATNESS becomes the opposite of GREAT in a matter of years. And it seems to me that professing to KNOW whether another person’s MIND has or DOES NOT have SCHIZOPHRENIA is a “professing” that has NO PLACE in what GREATNESS truly means.

Club groupthink has been in psychiatry because it is a default perspective in ANY human group that becomes fed up or upset. Even adovocasy groups.

Such club groupthink with its fortune telling of other peoples MINDS, becomes an “US” and “THEM” intimidation that has NO place in a FREE WORLD.

If I want to call myself PRINCE or POETRY or MAYONNAISELICK or BLUE CELLOPHANE SUFFERER or MOUSEARIELHAVER or SHOEDISORDERDISEASE or LADYRAMBLING or DOUBLEWHAMMYTRAMA or FBIUNITSEVEN or ORDINARY ME or THEREISNOTHINGWRONGWITHME or PARANOID SCHIZOPHRENIC or FOETUS or MUSIC…

IT H A R M S NOBODY.

The interior of my MIND being a “THEM” harms nobody.

So I heartily agree with all the sentiments. All across the globe it is SHEER bullying to seek to CONTROL the interior preferences of ANYONE’s MIND if they do not choose and want and welcome that influence.

What that means is THERE SHOULD BE NO LABEL POLICING. since some MINDS are fond of their familiar and harmless labels.

There SHOULD INSTEAD BE ANTI BULLYING POLICING.

And THAT MEANS that just because you choose to call yourself whatever you please, YOU MUST NEVER be BADLY TREATED BY ANYONE for it.

Report comment

Hi Rose.

Yup its astonishing the hubris and arrogance of those people yet what’s even more astonishing is that they have been given powers to police the minds of those deemed needing it by them.

Personally I’ve had a very colourful life before my ‘diagnosis, homelessness, prison hunger strikes and so on.

I’m the kind of chap who instantly rails against anyone that tries to enforce their will on me…yet the DSM even has a ‘mental illness’ to describe that.

As Steve says shrinks have ‘pathetic abilities’ but I find it shocking they can cower behind hospital security, cops, judges etc while sauntering through their erroneous interpretation of my mind jangling their proverbial keys, meds, restrictions and such as they shorten my lifespan and ruin my sex drive while they all drive back to their luxury homes in their Lexus’ to eat lobster and drink expensive wine with those the deign to be ‘normal’ people. Surely pathology would require complexity of some kind no? I see none myself. I see no indication of that. Have you ever read psychiatric philosophy? I was gobsmacked at how shallow it is

Report comment

shrinks have “intrusive thoughts”. Their brain and thinking was and remains about others. Tell me what kind of brain believes that others are ALWAYS the issue.

Report comment

Hi Rose

Thank you for writing the awful truth. You describe a Kafkaesque nightmare that thousands of people across the world like yourself live with everyday – a slow insidious destruction of joy and hope in living by powerful and malevolent forces represented by the mental health industry which are fully backed by the state and mainstream media.

In the last 150 years the meaning of human suffering has undergone a wholesale alteration that started slowly but increased in speed since the advent of the first neuroleptic in 1955; the person is now packaged up in bags of symptoms and branded with the label of any one or more of the 370 disorders in the DSM. The branding must not be questioned. The person learns not to trust any of their thoughts or sense perceptions as both are now deemed mere manifestations of their ‘illness’. As you write they are not treated as people but as patients or objects.

If you think about it, it should not really be surprising that psychologists treat their patients in this manner given that research in the ‘profession’ of psychology involves the torture of small animals. That’s how Skinner developed behaviorism and how Martin Seligman developed the theory of learned helplessness i.e. by administering electric shocks to dogs. Of all the clinicians I have met the psychologists were the most consistently devoid of humanity – even more so than the psychiatrists.

The little voice that started inside of you which was given power by your short talk with the taxi driver about an SSRI happened outside that system.

These voices are happening in air pockets – like this site ‘Mad in America’, peer support groups for coming off drugs, and movements like the ‘Drop the Disorder Movement’ in the UK which has attracted a small number of critical clinicians. Every few years you find an outlier like Dr Terry Lynch who wrote ‘Beyond Prozac’ nearly twenty years ago in 2004 or Dr David Healy the psychiatrist with expertise in pharmacology who exposed the fraudulent nature of the drug trials. However they tend to continue to operate as outliers and their stances have not gone unpunished by the mainstream medical profession. Dr Healy lost a fairly prestigious academic appointment in Toronto over a talk he gave on the dangers of SSRI’s.

Currently I believe the mainstream culture of drugs and diagnosis is stronger that it ever was – thousands of people owe their livelihoods to it as the mental health industry has mushroomed in tandem with the increase in people deemed to be in need being drugged/labelled so I do not think things will change. I don’t know when they will.

The greatest tragedy of course is the loss of a productive and happy life by those ensnared in the mental health industry. You write : “What if I had never been diagnosed? What if I had never taken psychiatric drugs? ” You write that you are still grieving all the years you spent suffering – years that you will never get back. That is the worst crime of all.

I don’t know how many more people will have to be damaged before our culture as a whole wakes up; currently it is seen as normal to drug five year old children for ‘behavioral issues’ so i have my doubts.

Report comment

Hi there,

Thank you for reading. Yes, it was absolutely a nightmare. I was grateful for my philosophy class in high school, as it seemed to give me an impetus to keep going at the time. I am a huge fan Dr. Healy and “Pharmageddon”. He has also given extremely world renowned lectures about PSSD, a condition virtually no one in the medical community ever discusses! I am so sad to learn about how such heros are often punished for exposing the truth and helping humanity in the most compassionate ways.

The drop the disorder movement was one of my biggest inspirations for dropping the language of my own pathology. Before I came across that community, I did not even know it was a possibility to question your own diagnosis. That is how incarcerated I became by the system. As you know, we all become prisoners of sort with very little power once we enter the mental health system.

I am so thankful for that encounter with my uber driver, I had virtually never really talked to anyone in real life who had side effects from psychiatric drugs like I did. We keep hearing how “rare” it is to be severely injured by medication, but judging at how many people we see in the support forums, we obviously know that is completely false. Our voices continue to be silenced, but I have hope that we will continue to take wins where we can. Many of those closest to me have had an “awakening” after seeing what I went through. On the flip side, many friends continue to believe in the false narratives of pathology and chemical imbalance. It is always a tug of war. We must continue to speak out! Thank you for reading.

Warmly,

Rose

Report comment

Oddly and most striking about all these so-called studies was that they came after WWII, partly in their alleged attempt to understand why “normal” people did what they did in the Holocaust. Obviously, they found no answers as they used psychology to hurt people and animals, too. Psychology is the “father” of psychiatry. Sadly, I have my BA in psychology. How strange in my memory that much of the nitty gritty details of how they conducted these experiments was glossed over and mentioned ever so briefly. However, while doing my degree, I did work in a lab which did “learning experiments” using little animals we caught in the wild. One of them bit me. What did they teach us? I think nothing except how to waste time and for some of the “experimenters” how to drink coffee. Thank you.

Report comment

Rose, this article could easily be about myself, give or take a few details of course. Thank you for having the courage to tell your story. The world needs to hear it. For the sake of those who have iatrogenic injury, for the prescribers and healthcare givers, and of course for the sake of altering our societal paradigm surrounding psychiatric drugs. I am in tears for our suffering and for the invaluable reminder that I am not alone. Seven years and I’m so much better, but I still have to revolve my life around my injury. Having to do this delicate dance is made all the more difficult by being misunderstood and unable to explain myself to others. I deeply admire your accomplishments all the more understanding first hand what it is like. I too am a writer, a hobbyist guitar player, and, when I felt better, a closeted singer. I’m also a documentary filmmaker and will be keeping this story on my radar for the future. Thank you again for sharing. My heart breaks that you had to have this experience, but selfishly it soothes my soul to know I am not alone.

Report comment

Hi JAB,

I am sorry that you suffered much of the same fate that so many of us have. I know what it is to revolve your life around your injury and the isolation that accompanies our invisible illness. The delicate dance is soul crushing and I now have years of being completely misunderstood by friends who are longer in my life. That’s so awesome that you play guitar! Music is a huge passion of mine and it has helped me a lot in my healing journey. We are never alone as long as we continue to find each other in community. Thank you so much for reading.

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

<3

Report comment

I was lucky enough to talk to a therapist once who said he believed ERP could be “extreme.” But otherwise, I was told by another after a 5-10 minute jaunt flipping through the DSM OCD criteria that I definitely had it and that it’s a brain problem, so no wonder I was struggling. There is nothing to be done to change it besides taking meds, though she admitted that there “are no good treatments for OCD.”

Regards, Pengeluaran Sydney Tercepat

Report comment

Thank you Rose for sharing your story.

I have been accused in the past of “Schizophrenia” and “Manic Depression”.

“Schizophrenia”

If you can get rid of the ridiculous wishful thinking disease model approach, and take a commonsense approach the so called problems of “schizophrenia” can usually be solved.

“Depression”

Genuine Depression is sometimes compared to an experience more distressing than fatal illness. I don’t believe I have ever suffered from anything like this.

“Elation”

I’m often happy to be happy.

Report comment

OCD

When a person comes off “medication” they often develop drug induced OCD. This is chemically induced but can still be accommodated for (with perseverance).

“Schizophrenia” Drug Withdrawal

While on psychiatric drugs – I had been disabled.

On Medication Withdrawal I experienced what Robert Whitaker has described as (drug withdrawal) “High Anxiety” . But I was able to get a picture of the anxiety problem, and successfully compensate for it.

.

Report comment

Hi Fiachra,

Thank you for your comment. I am so happy that you have gained your own insights into your history and have remained critical as to what the professionals wanted you to believe. I do believe I developed a drug induced OCD, as validated by my previous physician. It is a difficult reality, but the idea that I am ill or that this is a life-long condition now seems absolutely absurd. It sounds like you have maintained a high level of resilience after all that you have gone through. That is very inspiring! Thank you for reading.

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

Sadly, OCD is usually caused by the psych drugs either while taking them or during the withdrawal phase from them. I was diagnosed with OCD while taking the drugs. It went away when I stopped taking the drugs. However, there is confusion as to whether I even had OCD or whether it was just in the psychiatrist’s mind. This is all the DSM is in its many useless variations; the same with the ICD—just some made up words in the minds of psychiatrists who realize that the only way to make a living for them is to make up lies that will basically capture their audience as prisoners and hostages in a world where although the sun is shining, it is raining in their minds and vice-versa. It is all dangerous mind-game with drugs and therapies as the weapons. OCD is one of those weapons. Please don’t fall for it. Thank you.

Report comment

Rebel,

It’s really no surprise that the human brain struggles to regain homeostasis after exposure to potent neurotoxins. This can present itself as OCD or any of the other hundred constructed diagnoses in the psychiatric bible of the DSM. I am infuriated when I hear of individuals who suddenly have bipolar when in actuality is mania set off by an ADE to SSRI’s. The list goes on and on. I am not sure why so many still find this concept controversial. Perhaps it is because society desperately wants to believe psychiatric drugs are medication that are “safe and effective”. While they may prove to have short term benefit for some, it is that psychotropics are capable of grave harm. We must continue to share our stories and advocate for informed consent.

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

Thanks for a compelling blog Rose. I’m grateful you share your story as it validates how the system is so quick to label legitimate concerns, or temporary understandable thoughts and feelings as ‘disorders’ and thus inflicts more suffering, demoralization and loss.

It really speaks to how pathetic ‘mental health’ treatment is when a person can get more help and understanding from a brief encounter with an Uber driver than from disinterested professionals.

Report comment

Thank you, Rosalee. I always have strongly believed in the power of peer support and those with lives experience! It really is troubling when those meant to help can inflict so much harm when we are most vulnerable. Thank you for reading ❤️

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

It’s really all in the label.

It’s just a discrimination procedure and has ZERO to do with health.

If you look at me and decide I’m mentally ill or disordered, well what can I do about it? And how should I prove myself not to be?

Obviously I could never prove anything and why should I?

Complete weirdos in every which way so they want to exert power to say that it’s not them, but others.

Quackery

Report comment

Hi Sam Plover. I’ve never understood people who feel the need to label others. It only serves to help the psychiatrists delude themselves into believing that they are making sense of the world and ,unfortunately, fool people such as my family into believing they have an explanation that allows them to have comfort.

What it doesn’t do is help me. As you say its descrimination, stigmatization and all that positive stuff. Nobody has to take a word I say seriously anymore because I’ve been deemed ‘mad’ by ‘experts’.

The psychiatrists should remember that when one points a finger at someone there’s always three pointing back at yourself.

They can’t comprehend basic logic, horse sense yet they claim to be authorities on the mind. Its ridiculous IMO.

Report comment

Agreed, Jack. It is completely ridiculous. I am so glad that you can see through the lies and deception of it all. So many unfortunately cannot and remain trapped in the system.

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

Hi Rose.

If you want to be shown a label I don’t mind I was ‘judged’ to have a 171 IQ. Your average psychiatrist is reckoned to be 30 or 40 points lower than that.

I saw through their nonsense like looking through a pane of glass. The ones I’ve encountered are like inbred bumpkins to me tbh. I’m sure I exude that attitude when dealing with them.

Of course they’ve probably judged that grandiose too even though the battery of tests I was put through to determine my intelligence are on file.

After all, unlike real doctors whose oath is “Do no harm”, psychiatrists motto is ” Why investigate when you can ignore, dismiss and judge”.

No offense to any bumpkins out there. I’ve enjoyed many a horror film with youse in it. Also love the homemade alcohol…

Report comment

Exactly, Sam. Not to mention the lasting repercussions of mental illness labels. I’ve talked to women who will not pursue charges against their abusers because they’re worried how their diagnoses may render them an unreliable source of information. The system is so very broken. Thank you for your comment and for reading my blog!

Warmly,

Rose

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Thank you Rose for sharing your harrowing journey through this beautifully written and clear eyed narrative. So many important passages, but I found the Uber driver experience particularly compelling. I can’t help but think that most everyone regularly crosses path with someone in these ill-fitted shoes and never knows it.

Report comment

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for reading my story and your kind words. I believe we have many serendipitous moments in life that lead us to our truth. The wisdom in these chance encounters can not be emphasized enough 🙂

Cheers,

Rose

Report comment

Thanks

Report comment