Laura Van Tosh has been a leader in psychiatric survivor circles for 40 years, working at local, state and national levels. She spoke to Mad in America from her home in Seattle.

*********

Robert Whitaker: Laura, you have been a “psychiatric survivor” activist since the 1980s, working in particular on political and legislative issues, at both the state and federal level. But let’s go back to the beginning—how did you first encounter the mental health system?

Laura Van Tosh: I was 17, and I was visiting my mother in Seattle. I went there for a summer vacation, and ended up kind of losing it while I was there, and ended up involuntarily committed.

Whitaker: You had been living with your father?

Van Tosh: I was living with my father in Houston at that time, although I was born and raised in Miami. My parents divorced when I was five, and after that, I would visit my father on Sunday. Then my mother decided to take off when she was in her late twenties, and she left my sister and me with our father, who really didn’t know what to do. My father remarried, and his second wife also didn’t know what to do with us. It was a bizarre situation and we had to find our own way to grow up.

When I was 17, my mother reappeared in the picture and said to my father, can you send them up for vacation? Even that was a scene—my father tried to bribe us not to go. He offered a car. But we went up to Seattle, and I basically freaked out.

There were a lot of cultural things going on. This was 1978, and when I came to Seattle, there was a huge Gay Pride weekend, and I had never been around people who were openly expressing themselves that way. My father was someone who was prejudiced and racist, and I grew up in a sheltered kind of way, and it wasn’t a very good experience. And then I was exposed to all this stuff in Seattle, and I was kind of on my own on this vacation. My mother worked the whole time. As I said, I kind of lost it and I ended up hospitalized.

Whitaker: Against your will?

Van Tosh: Yes. But my father had legal custody of me, and he found out that I was hospitalized, and he hired people to take me out in the middle of the night and put me on an airplane that flew me to Houston. I ended up restrained on the airplane because I tried to get off. When we got to Houston, I was hospitalized on an adolescent ward for over a year.

Whitaker: For over a year?

Van Tosh: It was the summer of my junior year. And I had been a straight A student. It was horrible. It was a psychiatric unit in a general hospital.

I wanted to graduate from my high school, and so during my senior year, my father ended up hiring a driver to pick me up every day and take me to my high school. He made an arrangement with the school—in order to graduate, I had to show up for at least an hour every day.

I took English. I couldn’t even read. I just sat there and drooled. I was on Thorazine. They were trying a whole lot of other medications on me at the time, but I ended up being able to get a pass in that class and graduating by showing up. The driver was a hippie who delivered flowers, and every day he brought me through a drive-thru joint where I got a hamburger. I ballooned out because I was on these meds and there was no exercise, and I was allergic to Thorazine. I had to cover my body up because of sun poisoning.

But my high school friends stuck with me. And there was no stigma. You’d think there would be a lot of ribbing and making fun of me, but they were never like that. They treated me with respect. I have many of them as friends on Facebook today.

Whitaker: What did they diagnosis you with then?

Van Tosh: It was manic depression at that time.

Whitaker: Did they put you on lithium?

Van Tosh: Yes, that’s when I started the lithium. I celebrated my 18th birthday in the hospital.

Robert Whitaker: How did you experience the drugs at that time?

Van Tosh: It was awful. I was on a lot of different medications. I was in restraints a lot in this hospital. I tried to run. I was in restraints for a week and in a seclusion room for a week. These are the days when they had no regulations.

Whitaker: After you were discharged, where did you go?

Van Tosh: I first went to Seattle, and after I was homeless for a while, I ended up going to Florida. I stayed with my aunt for a little while, and then a cousin. I ended up joining a Fellowship House, which is a Fountain House model. I got involved in their whole program. I learned quite a bit about—I guess you’d call it a kind of socialization. I was always outgoing as a kid, but you have to learn how to reintegrate after you are in a hospital for a long time.

Whitaker: Laura, can I stop you for a second? You got straight A’s before your first hospitalization. You had friends. Did you have any hint of problems when you were younger?

Van Tosh: My father took me to a psychiatrist when I was 13. That’s when it all started. His second wife thought my sister and I were having problems, and all I can remember is sitting in front of this guy with a beard and crying. I didn’t know what to say to him. I didn’t know how to communicate. I think I wanted to tell him that we were being psychologically tormented.

Whitaker: By the second wife?

Van Tosh: No, by my father. My father didn’t hit us a lot, but he psychologically made us nuts in my view.

Whitaker: So really, the difficulty in your life at that time was within your family situation—not with school or your friends.

Van Tosh: I would say it was that. I think in terms of biochemical issues, if you were to look at that, I think there was a triggering that went on, that flipped a switch. But I do wonder if it was more situational than it was biochemical.

Whitaker: How did you get involved in the peer movement?

Van Tosh: After Florida, I returned to Seattle and I ended up working at Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, which is run by its subscribers. It was, in essence, patient driven. This was general healthcare, and I got a job in a department that organized patients as part of its infrastructure.

I ended up finding out about the peer movement while I was working there. I went to a NAMI Meeting and heard people’s names—Joe Rogers, Judi Chamberlin, Dan Fisher, Howie the Harp (Howard Geld)—a variety of names from way back when, and ended up getting on a conference call with them every Saturday. Once a month on a Saturday, Judi Chamberlin brought everybody together from around the country.

This was the early 80s. At this time, it was all word of mouth. There were no computers. I ended up joining these phone calls at 8 o’clock in the morning, once a month, and laying there in bed with the phone like this, cradling the receiver and my pillow, and just listening to all these people talk about what they were doing. They were organizing marches, they were opening drop-in centers, and they were helping other people get out of the system.

There would be a roll call of every state in the country. There were states like South Dakota or North Dakota that didn’t have anybody on the call, but most states had somebody on the phone who would talk about what was going on. Minutes were taken and distributed by mail. It was phenomenal and so inspiring.

Whitaker: What was it like to meet these people and be part of that initial growth of the psychiatric survivor movement?

Van Tosh: I was finally listening to people who had experiences like I’d had. I felt a vindication around some of the issues like seclusion and restraint. I’d experienced those things. And they were ardently opposed to any practices like that, and they were survivors. I really felt that they were on a path that I wanted to be on in terms of making change.

There was also a lot of exchange, where people would say, we did this in Massachusetts, and then someone from Nevada would speak up and say, how can I get that accomplished where I am?

When we say peer support today, it’s kind of amorphous. Most people nod their heads, they know what that means. But I’m talking about people taking over the system and developing and designing new services that didn’t exist at that point that were run by survivors.

Whitaker: Did you feel like you’re a part of a nascent Civil Rights Movement?

Van Tosh: I started to. Later, when we came together physically at conferences, I really felt that way. That’s how I came to work in Philadelphia. I think it was Joseph Rogers, who said to me, “If you can get to this conference in St. Louis, Missouri, I’ll talk to you about a job,” and I did. It was a protection and advocacy conference.

Whitaker: What year was this?

Van Tosh: This was like 1985. I was in my mid-twenties then.

Whitaker: What was the name of the organization you worked for?

Van Tosh: It was called Project Share, and they operated a homeless program called Outreach Advocacy and Training Services for people who were mentally disabled and homeless. It was called Project OATS—OATS like Quaker Oats. It was funded by the federal government, the first peer-run program ever funded by the federal government in this country. And Project Share had other peer-run programs in this big office, like a newsroom, with people running in and out. It was crazy and so amazing.

Whitaker: It sounds like fun.

Van Tosh: We had a blast. My program was Project OATS—street outreach—and at that time, there was plenty of homelessness, and I hired a group of people who had been homeless, including myself, and we organized and did street outreach and blended in with city teams. We helped people get off the streets and into houses, and that was our charge. As a matter of fact, tomorrow, I’m on a webinar with other people to talk about non-coercive alternatives because of what we’re facing today.

Whitaker: During this time when you were working with homeless people, did you see the connection between homelessness and poor mental health or psychiatric distress?

Van Tosh: The experience can weigh on you in a way where you become distressed, when the original act is really just not being able to maybe afford your housing.

There were people I worked with who spoke to themselves and had conversations with themselves, and maybe had unusual ways of expression in terms of jumping up and dancing around or something like that. But for the most part, it was a mix of people that had economic emergencies. I’m sure other stressors play a substantial role.

Whitaker: How long did you do that?

Van Tosh: Five years.

Whitaker: Did you enjoy living in Philadelphia?

Van Tosh: I love this city, I loved it.

Whitaker: And you were stable, you weren’t having any problems.

Van Tosh: I was doing very well. I then began to get involved nationally because we organized national conferences. Many of us were asked to go to Washington D.C. and sit on committees and also testify. I ended up getting involved with Tipper Gore and other people regarding an Interagency Council on Homelessness. Then I ended up on a kind of National Advisory Council, and I invited other people with behavioral health care and homelessness backgrounds who were peers to be involved with me. I was bitten by the national bug at that point.

I was still at Project Share, and then when I came back from D.C. or national events, I did some consulting work too. We were given a great deal of freedom and we were given the opportunity to speak at public conferences to get other people doing what we were doing.

I enjoyed doing street outreach, believe me. I used organizing skills during that job in terms of bringing people together, and effecting change. And while I was at Project OATS, we had demonstrations, we got arrested, a whole lot of happened during that five-year period. But I found myself leaning more towards policy work. I just liked it and I’m a good writer, so having those skills and liking it mattered.

After that, I worked for the State of Maryland, at the School of Medicine and within the state mental health department to do policy work.

Whitaker: What sort of policy work did you try to enact?

Van Tosh: The university gave me a project to document the qualities and benefits of peers doing homelessness services, and the impact on the system. An early paper that I wrote was called Working for Change. They ended up asking me to work on other things. I wrote briefs. I attended meetings. I went to D.C. quite often.

Whitaker: As a representative at the University of Maryland.

Van Tosh: There was a center in the university called the Center for Mental Health Services Research. I was a bona-fide policy analyst for the center.

At some point, the state asked me to write a report to create an Office of Consumer Affairs at the state level. That’s how I came to know people at the national association that represents state mental health departments. I went to their conferences, and that led to a position as the Consumer Affairs Liaison at the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD).

This was where I brought in a lot of peers to get involved in the national scene. I was involved in bringing more voices to the table, to the conferences, to the microphones. There were other people doing the same thing at this time, bringing peer voices to national attention.

Whitaker: This was something new, to have a peer voice at a high governmental level.

Van Tosh: It was daunting, but it was also inspiring. I remember feeling uplifted. I also remember feeling a great deal of frustration because you also know that you’re not doing enough, that much more needs to be done. Or else you start finding out that there are other rooms that we really need to be in, and we’re not there because we’re busy fighting with each other or whatever’s going on.

Whitaker: Laura, at that time you were trying to make changes at a political level. What did you want to see happen?

Van Tosh: I was searching for something . . . but I think I was really just interested in getting people to talk about the issues. People don’t talk about the issues enough. We hurry up and do something, but we don’t really debate them. For instance, we don’t have intellectual conversations about why do we have involuntary treatment? What do we need to do to make it stop? You know, there’s not enough time for that discussion to happen.

I think I’ve always been searching for kind of a macro table of a larger venue where people can do that, have that discussion, and come up with solutions. They let me start a project with that purpose called the Mental Health Policy Roundtable, and that still exists.

Whitaker: If you look back at your time at NASMHPD, do you think you were successful in changing things?

Van Tosh: I think I was, but I was alone. I was the lone staff. I felt a little bit stigmatized sometimes. I felt like a fish out of water often. I felt like I wasn’t always very happy. And then I had this relationship that broke up after 10 years and I ended up really having a big meltdown while I was working at NASMHPD. That was in 1996.

Whitaker: You were hospitalized?

Van Tosh: I got hospitalized in downtown Tampa. I was in big trouble. I was on a vacation.

Whitaker: You were involuntarily committed?

Van Tosh: Every single hospital I was in was involuntary.

Whitaker: Was this the first time you had been hospitalized since your first hospitalization?

Van Tosh: No. When I was 19, I was involuntarily committed in Seattle. I was homeless at the time, and I stopped taking my medication and I was living with a guy on an island and we were doing speed and different kinds of marijuana, and I ended up in a house fire. I almost died. I had to jump out of a window, and I ended up at the State Hospital.

That is where I was when I knew that I was going to work in the field. It was horrible. This was a place where you put people in restraints for a week. It was just very, very old and rusty and grotesque. The place was just ugly. And you know, not a place for people to get well. People sat on the floor. I sat on the floor often.

Whitaker: Sounds like a scene from a mental hospital in the 1930s. And people were heavily drugged?

Van Tosh: I guess for the most part, I don’t really know. I ended up finding my way out of there by sitting on the floor of the social worker’s office in front of her door with the door closed, waiting for her to show up to work every day, asking her to get me out. That’s what I did.

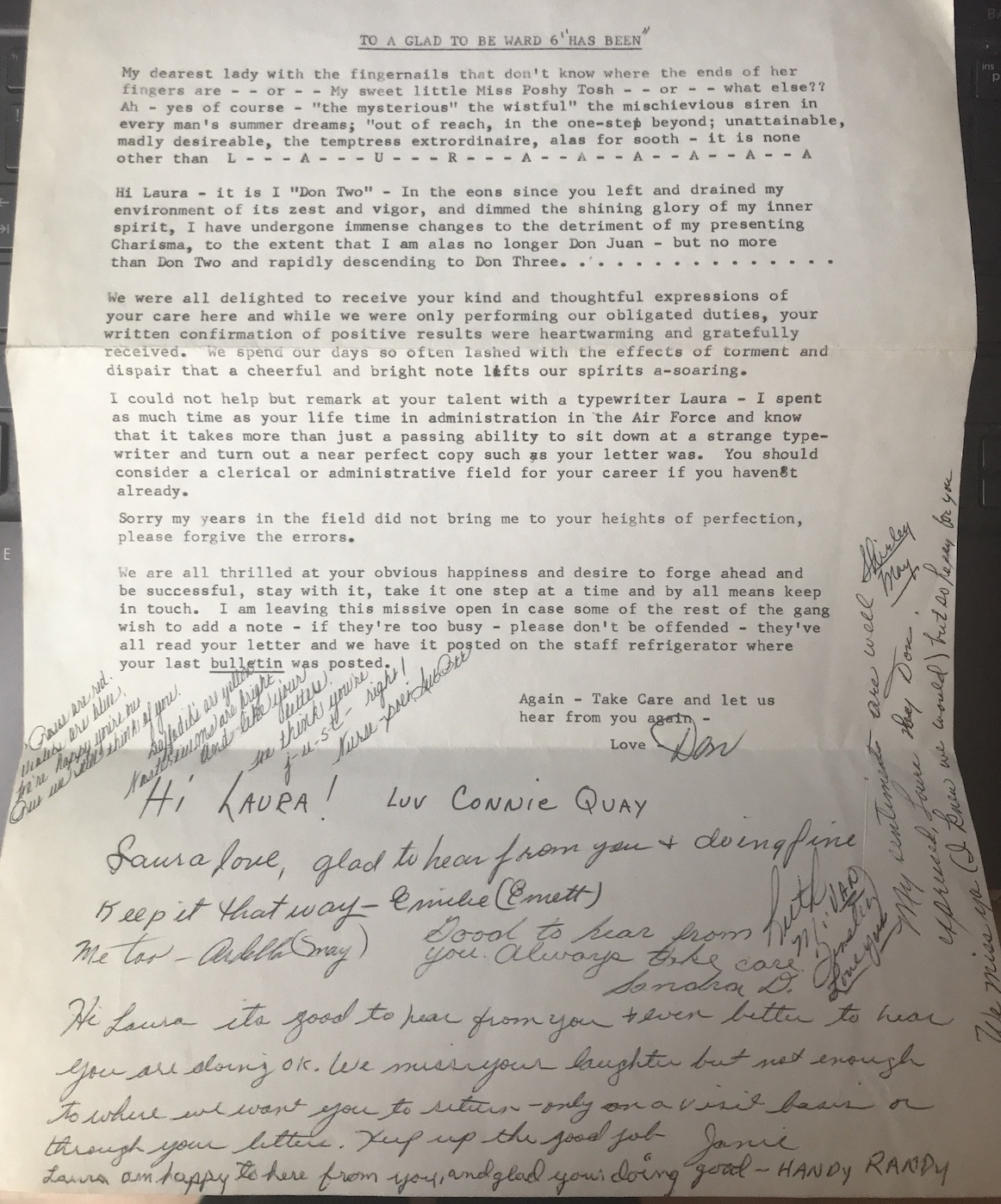

By the way, this is kind of a touching bittersweet issue. I used to write the people that worked there. I grew fond of them, I had names for them. They may have looked a certain way and I gave them a name of what they looked like.

And there was the night shift, this group of people, and they would all sit together and play cards and they’d let me come in and just sit there or they’d get something from their refrigerator. They’d get a little cookie out for me. They grew to be like my friends. I ended up sending them letters after I left. I still have a letter that they wrote back to me. It’s titled “To a Ward 6 Has Been” and then each of them wrote a note. They signed it by the names I had given them.

Whitaker: That’s a touching story.

Van Tosh: I worked at this same hospital 25 years later, and I put that note in my desk drawer the whole time that I worked there.

Whitaker: When you were hospitalized in ’96, were you hospitalized for a long time?

Van Tosh: That was a bad one. I was snagged by the police in the middle of the yellow line in traffic on a busy street.

I had rented out the President’s suite at a Hyatt Hotel. I brought just about all of my clothes. I used to dress up a lot at work. And I brought gorgeous clothes that I would never wear because this was Tampa, Florida, and I had brought winter clothes. So it was really a bad one. I was brought to an emergency location and restrained—it was called boarding. Boarding is where they don’t have a bed for you but they restrain you in a hallway.

Then I was brought to a 90-day lockdown facility somewhere. I have really no idea where I was the whole time. I was raped there twice by male patients. I was hit over the head by another patient who clubbed me. My glasses were destroyed.

NASMHPD ended up having a conference in Tampa while I was there, and so the NASMHPD CEO and staff visited me in the hospital and I couldn’t even speak. They gave me a lot of medication. I was trembling, I was an absolute wreck. I know I slept with one eye open.

There was no control. And then there were things like, after one of the people raped me, he ended up in a seclusion room and they have closed circuit TV and sound. They would turn the volume up so us patients could hear him wail.

When I had first arrived there, they kept me in the same seclusion room for four days before they let me out. When they opened the door, I was like a puddle of sweat because I had been banging the metal doors the whole time. It was torture.

Just the sickest, most disgusting place I’ve ever been. I’ve never been so afraid for my life really the whole time I was there. No STD tests. No counseling of any kind. They knew what was happening. They didn’t care.

It was a fucking circus. I haven’t used that word in a long time. But it was really, really frightening. I was a mess for quite a while. My mother came and got me out of there. Even after I got out they had to tranquilize me to get on the plane because I couldn’t stop hyperventilating. I had trouble breathing.

Whitaker: Did you go back to work for NASMHPD?

Van Tosh: I worked part time. National peer leader Dan Fisher played a role in my recovery back then, by the way, when I came back to work at NASMHPD.

I was court-ordered to go to outpatient treatment. We ended up going to lunch one day, and as I walked back to the program with him, Dan said, you know, you don’t really have to go in there. I felt I had to, but technically I didn’t, and I turned around and didn’t go back in. And I was fine. I went back to work the next day.

Whitaker: For the next eight years or so, you went back to work, doing consulting work. What brought you to Seattle in 2005?

Van Tosh: Really, being tired of Washington, D.C., thinking that I was ready to be close to my family, and because I was offered a unique opportunity by Andy Phillips.

He ended up closing some hospitals in Massachusetts. He’s a wonderful man. He called me and said, I’ve heard about the work that you’re doing in Maryland, helping people get out of state hospitals. Would you come work for me at Western State Hospital?

It took me a while to get that wrapped around my head because I had been there as a patient and I wasn’t sure if I could manage it. But I thought that it was a new beginning and that it was an opportunity.

Whitaker: What did you do at Western?

Van Tosh: I was the first ever Consumer Affairs Director. Nobody ever had a job like that before in a state hospital. And I was in upper management. My office, which I never sat in because I was busy doing my thing, was right next to Andy’s. I’m in touch with him now. He is a good friend.

Whitaker: Was your job there to protect the rights of people and help them get out?

Van Tosh: They had a patient advocacy department. I really didn’t want to be bothered with some of that, because it was just too much for me. My job was to help insert the peer voice into management. I was on the executive committee. I helped change policy there, especially issues around seclusion and restraints.

I did do a lot of patient-to-patient work, helping people navigate their treatment teams. I’d sit with people who were in restraints and ask, do we need to do this now? Can we let this person go? I organized educational events. My job was to have patient voices involved in making these changes.

I did that until 2009, and then I was offered a job at Oregon State Hospital.

Whitaker: So that’s when you met Bob Nikkel.

Van Tosh: Bob brought me there. It was a similar job to the one I had on the East Coast, peer bridging it was called. After that, I ended up working for the state mental health department and then at a regional behavioral health organization in Eastern Oregon.

That is when I came off lithium. I was on a kick of some kind that I needed to be med free. I was also having liver problems. My liver enzymes were out of whack in a big way. This was back in 2011/2012.

Whitaker: I remember when I met you around that time that you had come off lithium. You told me it was like reawakening back to your 17-year-old self.

Van Tosh: Yes. Simultaneous to all of this, I was experiencing a in a spiritual awakening. I went to a monastery in upstate New York and stayed there until they asked me to leave. I stayed way beyond a one-week retreat, and I did all these tasks—I was sweeping, I was cleaning, and I was cooking, but it was like, excuse me, but you don’t really belong here.

I ended up losing my job at the behavioral health organization too. They were wonderful people, but I was off medication during that time, and I was driving hundreds of miles every day to get to this job. It was just the most gorgeous drive you’ll ever take alongside the Columbia River for hours, and I was having this kind of ethereal thing going on. That was definitely some kind of psychosis.

I ended up homeless. I lived in a women’s shelter from 2012 to 2014, and I also ended up living on the streets in Salem. I was arrested a number of times while I was homeless.

Whitaker: Vagrancy and stuff?

Van Tosh: Sleeping on a park bench, yes.

Whitaker: What brought you out of that difficult time? How did you get out of that? Did you go back on lithium?

Van Tosh: I was involuntarily committed to a hospital and I would not recommend that. But I was on a psych ward in a general hospital, and they basically let me sleep. It was clearly nicer than a state hospital, and then I got out after 30 days, and they basically said, where do you want to go, and I ended up getting a train ticket and going back to Eugene. That’s where the women’s shelter was that I had stayed at before. That was decent enough, and I used to ride my bicycle and visit David (Oaks.) I helped him build a ramp at his home, after his accident. I had a shovel. . . . Habitat for Humanity actually built the ramp, and I was a helper. I did things while I was there in the community, and I kept in touch with David and Deborah, and I would go to their home and visit with them. They had a couple of gatherings I went to, I felt that I was an old caring friend.

Whitaker: You were indeed.

Van Tosh: Then I ended up leaving Eugene. I got in touch with my mother in January of 2015, and I moved back to Seattle. I was taking lithium at that time, but I was also taking other medications, Zyprexa, and I can’t remember everything else. I ended up developing some pretty strong side effects. But when I came to Seattle, the doctor I currently have ended up taking me off of those medications, and kept me only on the lithium.

I got approved for disability, and that’s what my ticket was . . . I now have an apartment I can afford. I live in a brand new building. I feel like I’ve been blessed. I’m in a community, a very diverse community called Central District.

Whitaker: Laura, you told me that you recently stopped taking lithium again, and are now just on a small dose of Rexulti.

Van Tosh: April 15th was my last dose of lithium. During the tapering, I started to feel like my head was clearing up. I literally felt like I had clouds in my head, or cotton in my head, and the cotton was being unwrapped.

I felt my vision was clear, clearer, I felt more articulate, I felt like I could grasp language that I have trouble sometimes grasping. Even just words. I wrote a letter to the editor at the Seattle Times by the way, and it got published. I’ve written four letters, and they all got published. Then they called me up and asked me to write an Op-Ed. I haven’t written one yet, but they said they liked my writing style.

Whitaker: Is this on disability or related to mental health?

Van Tosh: It’s mostly on policy related to behavioral health.

Whitaker: You have been off lithium for three months. How are you feeling now?

Van Tosh: Unfortunately, I got an x-ray of my heart for some reason before April, and it turns out that I have heart failure. My cardiologist thought there was a blockage, but there’s absolutely no blockage, but one of my chambers isn’t pumping enough blood to the bloodstream. I’m now on oxygen in response to severe obstructive asthma and hypoxia.

Whitaker: Jeesus, Laura, I am so sorry to hear this.

Van Tosh: I’m now taking several medications for these conditions. The medication and oxygen has helped me because my walking is better.

I also now have remnants from a rash . . . there are pigmentation changes in my skin. I have spots on my arms and legs. My doctor told me that lithium was the cause of the rash.

Whitaker: Do you think the psychiatric drugs you took have contributed to these health problems?

Van Tosh: I used to read about how the “mentally ill” die 25 years early. I was always questioning that, but there are other causes such as poverty and diet, and everything related to that.

Whitaker: Laura, you’ve had this incredible life of activism from the early days of the psychiatric survivor movement. Do you think things are better for psychiatric patients today, or worse, or the same? Have we made progress?

Van Tosh: The activism has certainly died down in the behavioral health arena. Now there is the broad disability movement, and David Oaks, Ron Bassman, Tom Olin, Janine Bertram and other people are involved in that. I subscribe!

They’re keeping a little bit of a pilot light on but there’s no fire. I think that has a lot to do with the professionalization of our peer movement. The certified peer counselors are doing good work, and I want to be careful about what I say, but I don’t see what they are accomplishing systemically from a policy point of view.

That peer layer, which is provision of services, has merely been added to an already existing system. Peers didn’t come in and change the system. Do you understand what I’m saying?

Whitaker: I think your analysis is right on.

Van Tosh: By the same token, I’m involved in a coalition that will be launching soon. It’s a working group primarily located on the East Coast and we are finding our way to organize and amplify a message of the younger generation. Part of the agenda is to get us back to some of the original roots, around racism and inclusion and diversity and deinstitutionalization, even non-coercive crisis response. I’m so excited to even be in the room with them because they’re young, they’re righteously spirited and yes, angry, and they want to do something about it.

Whitaker: Your lifelong dedication to the psychiatric survivor movement and to creating systemic change is truly inspiring. Now last question. You were in policy work for many years. Is there one policy that you recommended that got enacted that you are particularly proud of?

Van Tosh: I would say the one thing that I was really, really proud of that I know I didn’t do alone, is the Olmstead decision. And that’s the Supreme Court ruling which obviously I didn’t recommend myself.

Whitaker: The 1999 Olmstead ruling stated that segregation of people with disabilities is a form of unlawful discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In what way did you participate in making that happen?

Van Tosh: It’s part of the chain of events that followed—whether you call it failed or successful—”deinstitutionalization.” I think it was a natural progression from deinstitutionalization. I wrote a lot about that during that time, explaining to people primarily at the national level how crucial this law would be, and this was before the ruling was enacted. And then after it was enacted, I did a lot of advocacy. I did that with the Bazelon Center as a guide, which was really the lead on this.

I think the other thing that’s really important in terms of the peer movement is that there were two plaintiffs, Elaine Wilson, who has since passed away, and Lois Curtis. And it was understanding their lives, understanding who they were, that was so important. They were two women with mental retardation (now called intellectual disabilities) that were stuck in a Georgia state psychiatric hospital and the case was built upon them. They tried to get out and couldn’t.

It was really an emotional connection to them, even though I’d never met them, and really putting forth how important it was that we have these two people that were standing up and saying, “No, we want to get out here, and we want to file this case.” I need to be very clear that there were people at high, high levels that were really moving this case forward. I was a junior level kind of person cheerleading the crux of the case’s implications for us all.

The other thing that I did do in terms of policy was that I organized a demonstration against forced treatment in the early ’90s in Maryland and actually have photographs of that. There’s a book being written right now about that. Do you know Phyllis Vine? The cover of the book is a photo of me talking into a megaphone at that demonstration. “Fighting for Recovery—An Activists’ History of Mental Health Reform” will be published later this year.

Beyond that, I would say, I educated people and created a way to teach people about why it is important that we were bringing people out of the hospital. It’s not that people get well, it’s that the best place to recover is in the community. This is why the Olmstead decision is important.

My goal has always been about that, it has always been about freedom of people, not just free from the shackles, but actually freedom to create your own life.

Whitaker: So well said. Thank you for speaking with me, Laura.

I was incarcerated by my third psychiatrist, a tall spotty man, who told me I would get out of solitary confinement if I agreed to go on a drug trial. I had no option but to say yes to that bastard and take the pills. The pills gave me dark circles which turns out to be a side effect that will certainly need explaining to future partners and so all because of shitty psychiatry I may never have a future paramour.

…

Is that what I am supposed to write? Will that do? If I sound all antipsychiatry will you all welcome me AS AN EQUAL?

If your definition of EQUAL has conditions such as that I must tow the line and agree with your opinions that are not my opinions, or that I must mime your conditions that more or less imply that I “HAVE TO” like your perspective, or “HAVE TO” adore whatever theorums or conjecture you adore…then it is NOT any EQUALITY that is worthy of the name.

An orthodox Jew knows this upon being invited into the bosom of the church of Catholicism.

Allow me…

to be the affably DIFFERENT.

EQUALLY SO.

In my opinion.

Report comment

A lot of people are talked into the mental health system, so for them it is voluntary. But it is still being done by people who hold government issued medical licenses. So having no medical benefit, it falls clearly within Nuremburg precedent for Crimes Against Humanity.

I feel that there is not enough being done to immunize people against the arguments of the mental health system.

And this is especially cogent right now because in CA Governor Gavin Newsom and Senator Susan Eggman are getting legislation passed to make special courts to force the homeless into “mental health” treatment. Civil Rights groups are vociferously opposing this, but so far Ash Kalra is the only legislator who has voted against it.

Joshua

David Brooks and Jonathan Capehart denounce the notion that these spree shootings are caused by “Mental Illness”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_qFeFgmKf8

Report comment

Joshua,

Thanks for the excellent video link –

Report comment

Removed at request of poster.

Report comment

So very honored & uplifted we count each other as friends. EVERYONE please read LVT”s story of lifelong psychiatric survivor activism. Share widely!

Report comment

Got a link to that David?

Joshua

Report comment

Joshua, these comments here are about the interview with LVT. The link is: https://www.madinamerica.com/2022/07/laura-van-tosh-psychiatric-survivor-activist/

Report comment

Thank you, David!

Report comment

Robert, my angels like you.

Someone likes Elvis Presley. They told me…

“He likes Elvis Presely”

My angels do not spy on people. If you do not want them sending support and healing to you then tell them to go away.

Report comment

I was so moved and at the same time enlightened to hear Lara story. I don’t think we ever met because I was on the West Coast and didn’t drive, but I was aware of her work when I went to conferences and state and national policy meetings. Every day in bed was by word of mouth and person to person the same way pure support used to be. Lara‘s life story raises a question that deserves a lot of thought and interviewing. I have been an activist and writer all of my adult life and have been made to take psychiatric medication, and at some point I believe had to because my brain had been changed morphologically and chemically. Would I have accomplished what I did without medication? Is it worth it to now have tardive dyskinesia? Bonnie

Report comment

I was amazed to read that in the middle of the high-level advocacy work Laura was doing, she repeatedly fell into the hands of the psychopaths running various psychiatric prisons, but she kept on doing her life’s work! Good for you, Laura! I was lucky that once I got out of the psych institutions where I spent my whole childhood, I never went back. The closest I’ve come was maybe a year ago, when I started to cry in the emergency room, realizing that my days of good health were over. Some nurse literally ran up, and made plain that she thought I should be committed, because , I guess, crying in the emergency room is a sure sign of serious “mental illness”. Everyone knows that, right? Isn’t psychiatry wonderful, so helpful?

Report comment

“Whitaker: So really, the difficulty in your life at that time was within your family situation—not with school or your friends.

Van Tosh: I would say it was that. I think in terms of biochemical issues, if you were to look at that, I think there was a triggering that went on, that flipped a switch. But I do wonder if it was more situational than it was biochemical.”

Interesting that the question is based on an external attribution of cause (family versus school or friends), whilst the response questions the causality as being internal (biochemical) versus external (situational). I note that in order to ‘chemically kosh’ people, one needs to justify that with an internal attribution, lest the ‘treatment’ would not be seen as working.

The other thing I note is this;

“Then I was brought to a 90-day lockdown facility somewhere. I have really no idea where I was the whole time. I was raped there twice by male patients. I was hit over the head by another patient who clubbed me. My glasses were destroyed.”

I wonder if Ms Van Tosh would comment on our Minister for Mental Health’s comments regarding a report tabled in Parliament about the large numbers of women who were reporting being sexually assaulted in locked facilities. When asked about the report she responded by saying “You can’t listen to them, they’re mental patients”. (see Hansards)

Personally I see a problem with such an approach, and a possible reason people may be being swallowed by the ‘system’ never to be seen again until they attend their own funerals but ….. maybe I just don’t understand something they are discussing at the brothels [or is the euphemism ‘health spa’?] the taxpayer is paying for (see the recent use of taxpayer funds for $700 massages at Soapland by one of our Politicians. The laptop with the videos of these ‘meetings’ yet to be released from ‘legal challenges’. Perhaps nearer the election may be a good moment?)?

Still, thanks for all you have done Ms Van Tosh. After being introduced to mental health services, and THEN finding that I was homeless because I dared to complain about their ‘treatment’ of me (“we’ll fuking destroy you” I was told when attempting to have their misconduct reported to the relevant authorities [mandatory reporting to the corruption watchdog], a further offence compounding the other offences they had already committed by ‘procuring’ me unlawfully etc. The gaslighting to have me end my life by my own hand AFTER the more direct approach in the E.D. was rudely interrupted was positively vicious)

I think that the ‘flipping’ of cause and effect may be one of the best weapons they have in their war against their perceived enemies (that is, anyone who isn’t a mental health professional, commonly called patients. Or the rest of the world as we know them). And with police providing material assistance in the commission of offences [ie retrieving documented proof of their offending before lawyers get the opportunity to examine them]….. well, the reasons for their failures seem obvious, though not necessarily apparent to an unsuspecting public. Until they are snatched from their beds and transported against their will to a locked facility for interrogation whilst ‘medicated’ without their knowledge with date rape drugs.

Spiked with benzos, then cause an ‘acute stress reaction’ [police are being used to ‘rough em up a bit’ before doing ‘assessments’ in my State. Pepper spray, beatings, run them down with a police car, head stomp, and little pieces of lead having been added to the list recently after a court decision. I have videos if anyone disbelieves me…… but “you can’t listen to them, they’re mental patients” right?] being a great lip loosener….. and not torture, in the strict definition of that act set out in Article 1 of the Convention, if you make the target an “Outpatient” before you call Police to have them detained for questioning. “Inherent in or incidental to lawful sanction” and the Mental Health Act makes anything you wish to call ‘treatment’ lawful, as you seem to be aware.

One doctor (who wrote a prescription for the date rape drugs I had been ‘spiked’ with post hoc to conceal that offence) writing “Potential for violence, but no actual history or clear intent”. Since when did his paranoid delusions become my ‘illness’?

Report comment

Thank you for this interview, which is so depressing.

This woman may have dedicated her life, but things have not changed, not improved and few know her. More people may be harmed by psychiatry now than ever before. Sounds her quality of life is poor, certainly not enviable.

Older women who protest psychiatry even on the pages of Mad in America are obscured by society. Not obscured by Mad in America but not prized by society. All the leaders of pyschiatry are white men in this country. The only female leaders of psychiatry recognized by even Mad in America are white women from other countries like England.

Thanks for the heads up. This interview reinforces that there was never any hope for me regaining my life. The terror of living my criminal psychiatry destroyed life with declining health and mental torture is nightmare that never ends and won’t end until I am dead. The terror.

Nothing is worth living life with the destruction of criminal psychiatry.

Losers stories aren’t told in the mainstream.

Buried alive. The United States is hell, not a great country, not for me.

Report comment

I am sorry to see this so late after you wrote it. I didn’t get to all of the comments, apologies. I hope you are thriving today. I have stored a quantity of positivity and that’s helped me to get by. I am also grateful for what I have. I am in community continuing to give back. That is a gift.

Report comment

The two most destructive aspects of psychiatry – psychiatric exile and psychiatric drugs – loomed over Ms. Van Tosh’s life and seem likely to end it early. Those were the punishments she faced for seeking any amount of rest from work, retribution against her abusive relatives, or opportunity for a drug-free existence. No one deserves that, and certainly not when they’re working as hard as Van Tosh did for so many years. I’m so glad she’s able to take it easy now, but it’s enraging to know she’ll pay the ultimate price for surviving 40+ years of psychiatry.

Report comment

I am thriving today. Yes, it has been 40 years but I see positive advances in the field. People like me are watching how younger people are taking their place at the decision making tables. I am watchful of the growth of the mental health movement and how peers are influencing policy. Those steps are being managed differently and the approach is not as militant as it once was but change seems to be occurring. A blending of peer groups include mature and very young leaders. The blend is healthy and needed.

Report comment

Hey, Laura, great to hear your voice and know you’re still around and doing your thing! Hope all is well with you!

Report comment

Someone comes up to you, after you’ve told them what actually happened to you when coming full front on with the megalith that is organized psychiatry and it’s ordering of reality, it is a gift to be told:

“You’re fortunate to be alive.”

– Andrew Phelps, PhD 2004 Alternatives Conference, Denver Colorado

Stay in it Laura, too many have conveniently forgotten the true depth and dimensions of what the culture is up against. Thank you too Robert Whitaker for bravely and eloquently reporting out the elephant in the room of a society that is literally being “driven crazy”.

And, where a true respect for intellectual diversity is both rare and oddly represents some kind of non descript jeopardy, yet to be recognized or realized.

Report comment

Laura, wishing you all the best–there was a time when we would meet at meetings in the DC area in the 90s and in Takoma Park when we both lived there and lost touch around 1996, thus I was unaware of some of your traumatic experiences after leaving DC. I am so glad to learn that you are a survivor and still making this a better world. Around 1996 my son became a voice hearer and started having interactions with the mental health system, some good and some bad. This motivated me to move to a location with less intensity, fearing my son was at risk of involuntary treatment at one of the state hospitals in Maryland or DC, so we relocated to Maine in 2002. He was able to get an associates degree, employment from time to time and eventually on disability and now has an apartment above us in a small town in Maine. I too wonder if there was something situational that happened when he was younger or in junior high or high school that triggered onset of his disconnect to a reality that others around him experience????? But he has a wonderful outlook on life and a generosity of spirit far greater than most people, although he has experienced disappointments when not achieving some of the goals he had expressed wanting to achieve. Laura, even though it was a short period that we knew each other many years ago, you and many others from the peer/consumer/survivor community made a huge difference in my life and I hope in how I interacted with my son and others when working in the mental health field.

Report comment

Diane,

I recall your name and thank you for writing. I am pleased you are well and that your son has found comfort.

Laura

Report comment