Antidepressant withdrawal is common, and may be severe in about half of those who experience it. Indeed, in 2019, England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated their guidelines to acknowledge the potential for severe and long-lasting antidepressant withdrawal. However, it’s difficult to predict who will experience withdrawal.

Now, researchers have conducted a review of the existing data in order to try to answer this question: What factors increase the risk of withdrawal after stopping antidepressants?

Their answer: duration of use is a major factor, with people who have used the drugs for years at the greatest risk. Another important predictor is whether people have experienced withdrawal from the drugs before—either after forgetting a dose, or after trying to stop previously.

Their answer: duration of use is a major factor, with people who have used the drugs for years at the greatest risk. Another important predictor is whether people have experienced withdrawal from the drugs before—either after forgetting a dose, or after trying to stop previously.

Other predictors include the specific antidepressant used and the dose of the drug.

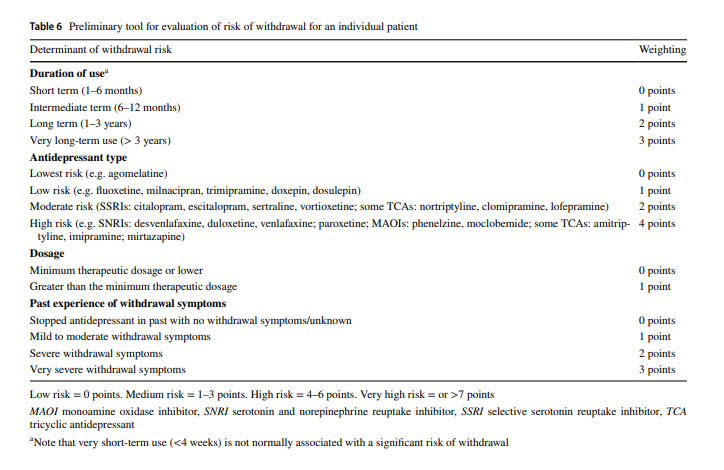

Using the predictors they identified, the researchers then created a table which can be used to identify patients at higher risk of withdrawal. Patients with a higher risk score may want to be the most careful when it comes to slowly tapering off the drug.

The researchers suggest that future work needs to be done to confirm and refine the predictive ability of these factors.

The researchers suggest that future work needs to be done to confirm and refine the predictive ability of these factors.

The article was a review of nine previous studies that had included data about withdrawal effects. One of the studies was conducted by the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM), which was able to obtain and analyze unpublished data from drug manufacturers. This is useful since published data is more likely to be favorable to industry.

The researchers write that “in its severe form, the SSRI withdrawal syndrome has been reported to be associated with ataxia leading to falls, electric shock sensations that impair walking and driving, and urgent consultations at emergency departments, in published case studies. The discontinuation period is also associated with a 60% relative increase in suicide attempts, compared with previous users of antidepressants.”

What causes withdrawal symptoms? According to the researchers, antidepressants perturb brain chemistry, and the brain adapts to these changes to maintain homeostasis. For instance, since SSRIs cause more serotonin to remain in the synaptic cleft, the brain compensates by producing less serotonin. When the drug is stopped, the brain changes persist until it can adapt to the new, drug-free state.

This biological adaptation is called dependence, which the researchers are careful to note is different from addiction. Addiction involves cravings, compulsive use, and other psychological effects that do not seem to be present with antidepressants.

“Adaptations to the presence of the drug predict withdrawal effects because these adaptations do not resolve instantaneously upon stopping the drugs but will persist for some period: the ‘mis-match’ between the level of drug action to which the body has been adapted to and the lesser amount of drug action it receives (upon dose reduction or cessation) gives rise to withdrawal effects,” the researchers write.

Interestingly, perhaps because of its longer half-life, they found fluoxetine (Prozac) to be less likely than other antidepressants to cause withdrawal symptoms, while paroxetine (Paxil, which has a short half-life) was associated with the highest risk. However, it is also possible that fluoxetine (with its longer half-life) may cause delayed withdrawal symptoms that were not picked up in short-term trials.

SNRIs and MAOIs were also associated with the highest risk, possibly because they affect different and more varied brain systems.

One factor that was not associated with level of risk: the psychiatric diagnosis. That is, it doesn’t seem to matter for what reason you were prescribed an antidepressant when predicting whether you may experience withdrawal.

Higher doses of antidepressant were associated to some extent with increased risk of withdrawal, but this was a less significant factor than the others. The researchers theorize that this “ceiling effect” may be due to the hyperbolic dose-response curve of the drugs. Even the lowest “clinical” dose of an antidepressant already occupies almost all serotonin receptors, meaning that increasing the dose doesn’t make much difference neurobiologically.

The article was published in the journal CNS Drugs. The researchers included Mark Horowitz, Adele Framer, Michael P. Hengartner, Anders Sørensen, and David Taylor.

Horowitz was interviewed by Mad in America in 2019, discussing a paper in Lancet Psychiatry, co-written with Taylor, that reviewed the evidence for very slow tapering for antidepressant discontinuation in order to avoid withdrawal effects. Horowitz also explained that he came to this realization after attempting to withdraw from antidepressants himself and discovering withdrawal symptoms firsthand.

Framer, also known by her online handle of Altostrata, founded the peer support website SurvivingAntidepressants.org after her own experience attempting to withdraw from paroxetine. She has also been interviewed by Mad in America.

Hengartner is the author of a recent book, Evidence-biased Antidepressant Prescription, Overmedicalisation, Flawed Research, and Conflicts of Interest, which explores the ways financial conflicts of interest have distorted and compromised the scientific literature when it comes to the efficacy and safety of antidepressants. He has also been interviewed by Mad in America.

Anders Sørenson is a Danish clinical psychologist who has also been interviewed by Mad in America about his work around antidepressant drug withdrawal.

Taylor, a frequent co-author of the others, is a renowned researcher on these topics who has been involved in the NICE guidelines and in the Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines as well.

****

Horowitz, M. A., Framer, A., Hengartner, M. P., Sørensen, A., & Taylor, D. (2022). Estimating risk of antidepressant withdrawal from a review of published data. CNS Drugs. Published online on December 14, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y [Full text]

I hope that one day someone does similar research to predict risk of antipsychotics withdrawal symptoms and their severity.

All the most important results published here on Mad In America site (like this) should really be collected in one place here, because currently they just disappear soon after publishing and are hard to find afterwards hindering the educating.

When combined evidence against current medical model would be in few easy to find places then it could be reused and spread without extra effort. There are dozens of important articles here, but only regular followers know about them.

Report comment

WHY don’t they have a study on the withdrawal symptoms of society, when it’s told the truth about ALL psychiatric drugs, and that they DO NOT treat a chemical imbalance!? Is this akin to being told Santa doesn’t exist, the Easter Bunny doesn’t spread around Easter eggs, or that a benevolent deity (or energy or concept) doesn’t need someone tortured to death in order to allow people into “Heaven!?” And that they would have a wonderful afterlife if that “example” of how to attain it had never been acted out!? Could it be reality or ideas of benevolence don’t need such publicity stunts!? Since I’m going on about “Jesus” again, I understand that in A Course in Miracles, he says he didn’t see himself as being murdered, he didn’t see himself as a victim, he didn’t see himself as being torn, and the rest of it, then says that one either crucifies themselves and it’s not going on on the outside, but to me that still negates the natural instincts one might have to GET OUT of a situation one can escape from, and then practice forgiveness AND experience miracles the natural way of enjoying life, here on the earth, not someplace you would have ended up regardless, without all of the drama. And if he is going to go on about the inside, then there’s dealing with that on the inside, not in “Heaven” and not by fulfilling a “task.” Dealing with having to escape a situation, and the incurring emotions like any refuge has to, is exactly that, THAT happens on the inside, and I think that’s a bit stronger than see me crucified while I deny it as it makes me into a commodity. You can do this as well. HOW MANY of us having to deal with the mental health system have had to simply give up on being part of this acknowledged machinery in “society,” that’s given rewards for being “constructive!?” Might there be a whole other world, that’s also part of nature!? Psychiatric drugs numb the brain, they interfere with natural brain processes, I happen to love my body, and my brain, and am fascinated by it’s responses, even when I was “psychotic” the whole labyrinth of symbolism and insight going on, from the place of no time, evocations of themes and insights regarding life so my reflexes could gain some legroom in expressing where they might have lead to had I not been “psychotic,” stuff I actually avoided rather than to be normal. Even when my body hurts, or my emotions are disturbing, it’s still fascinating. It’s amazing what’s going on. How can you grow finger nails, how can you breath, how does your hair grow, how do you see, feel, taste, love, hate…. all of it. How can my finger hurt when it touches upon a flame, how can I feel love when I hug another person? I don’t see incapacitating the brain from normal functions as part of experiencing a full life. Are there withdrawal symptoms from having incapacitated your brain, whether it’s with chemicals or ideology!?

HALF of people have difficulty getting off of a drug that they were likely lied to regarding how it works and what it really does. That’s what the article says, without even touching upon side effects and the real workings of the drug scientifically. In contrast to the “observation” of those already deciding sadness can be a disease, and that a disabled mind is more healthy when given a chemical imbalance that suppresses said expression of sadness. That while a person is told it’s treating exactly what it causes (a chemical imbalance). And a person is more “happy” with a society that can’t deal with the natural instinctive response called “sadness.” Is “happiness” really such a lie!? A bad fairy tale? The act of being inducted to a society that can’t deal with what’s called sadness which might point out that the indoctrinated “happiness” isn’t quite what it’s made out to be?

Could we START with not lying!? Could we start with not telling magical fairy tales that in the end aren’t magical but predatory towards people wanting to find an answer!?

Report comment