In a recently published commentary in Psychiatric Times, Ronald Pies and Joseph Pierre renewed their “case for antipsychotics,” citing in particular two “placebo-controlled” studies that they said showed that the drugs improved the quality of life of people diagnosed with schizophrenia. But before Pies and his co-author delved into that literature, they made this assertion: Only clinicians, with an expertise in assessing the research literature, should be weighing in on the topic of the efficacy of psychiatric drugs. They wrote their commentary shortly after I had published on madinamerica “The Case Against Antipsychotics,” and it was clear they had me in their crosshairs.

They wrote:

“We do not believe that armchair analyses of the literature by non-clinicians will answer the risk/benefit question in a humane and judicious manner. On the contrary, we believe that the working with psychotic patients, and appreciating their often profound suffering, is an essential part of the equation. Critics of psychiatry who have never spent time with patients and families coping with the ravages of schizophrenia simply do not grasp the human tragedy of this illness. These critics also miss the deep-seated satisfaction that comes from seeing severely impaired patients achieve remission, and even recovery—in which antipsychotic medication usually plays an important role.

As clinicians with many years of experience in treating patients suffering with schizophrenia, our views on antipsychotic medication are shaped not only by our understanding of the scientific literature, but also by our personal care of many hundreds of patients, over several decades.”

Their message here could perhaps be summarized more succinctly in this way: Whitaker, butt out. Then, in a comment Pies posted beneath his own article, he went a step further in his criticism.

“I am tempted to say that if there were such a thing as ‘journalistic malpractice,’ these critics would be up before the Journalism Board for reprimand.”

Now I, in turn, am tempted to reply to Pies and Pierre that my reporting on this subject already went up before a journalism board for review. In 2010, the Investigative Reporters and Editors Association gave Anatomy of an Epidemic its book award for best investigative journalism of that year. But then I realized that this assertion of theirs needed a more careful response.

They are asserting that review of the “evidence base” for medications should be left up to the clinicians who prescribe the drugs. To a large extent, this is indeed how our society functions. It is the “thought leaders” of a medical specialty who create the narrative of science that governs societal thinking and clinical practices. They are the “experts” who review the medical literature and inform the public what science has revealed about an illness and the merits of drug treatments.

A journalist is expected to report the experts’ conclusions. Indeed, 18 years ago, when I first began writing about psychiatry in any depth, I never imagined that I would write a paper like “The Case Against Antipsychotics.” That does lie outside the usual journalistic task. However, I can easily trace the journalistic path that led me to this end. I would never have started down this road if academic psychiatrists—and the American Psychiatric Association—had fulfilled their public duty to be trustworthy reporters of their own research findings, and exhibited a desire to think critically about their own research. It was precisely because I began reporting about that failure, step by step, that I have ended up trespassing on their turf.

On Becoming a Medical Journalist

The role of a medical journalist can be confusing. I first began writing about medicine in 1989, when I went to work for the Albany Times Union as a science writer, and I immediately had the sense that my job had now changed.

Before that, I had worked as a general reporter for a small newspaper, the Plattsburgh Press Republican. In this position, you cover local politics and business, and you are expected to be skeptical of what you are told. You try to support your reporting with an examination of documents, and while you may rely on interviews to flesh out a story, you are aware that the people you quote have an agenda. They want to present themselves to the public in a favorable light.

But once I became the science writer at the Albany Times Union, I understood that my job was to take complicated science matters and make them both understandable and interesting to a lay public. I was covering the march of science, and the people I interviewed – doctors, physicists, etc. – stood on a societal pedestal. Perhaps they could use a little help in explaining their work to the public, but that was because they were used to thinking and speaking as scientists, which apparently was a rarified language that we mere mortals had difficulty understanding.

My job, it seemed, was to serve as a translator of scientific findings. I could make the difficult science “clear” to the public. I have to confess, I was quite happy to be charged with this task. I have always loved science and the scientific mind, and being a science writer was like being paid to immerse yourself in that world. I thought, this is the best job ever.

At the same time, I hadn’t completely put my journalistic skepticism aside. In the spring of 1991, I wrote a series on laparoscopic surgery, which was being introduced to great fanfare at the time. But rather than write about that advancement, I became interested in reporting on how the introduction of the surgery had been botched, as many surgeons, eager to offer the latest technique, did not get proper training in the new method. This, I documented, had led to a number of patient deaths during routine gall bladder surgeries. That was my baptism into thinking of medicine as both a scientific and a commercial pursuit, with the latter having the potential to corrupt the former.

Over the next seven years, I studied and worked in various non-newspaper environments that, I believe, helped me become more skilled in assessing the merits of a published study, and more aware of the problems with the commercialization of medicine. I spent a year as a Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT, and later took a job as Director of Publications at Harvard Medical School.

In that position, I edited a weekly newsletter that reported on research by faculty associated with Harvard Medical School. The newsletter was read by other faculty (and in other halls of science), and thus the stories needed to capture the complexity of their research. Equally important, this was at a time that the idea of “evidence-based” medicine was being introduced. The rationale for this practice was that physicians could be deluded about the merits of their therapies, and thus they needed to have their care guided by science. I took that lesson to heart.

Next, I co-founded a publishing company called Centerwatch that covered the “business” of clinical trials of new drugs. From the outset, CenterWatch was an industry-friendly publication. We wrote about the opportunity for physicians to earn extra income by conducting clinical trials, and we presented clinical trials as an opportunity for patients to gain early access to promising new therapies. Our readers were from pharmaceutical companies, academic medical centers, contract research organizations, and financial institutions that covered the clinical trials industry. In addition to publishing a weekly newsletter and a monthly report, we developed a website that helped pharmaceutical companies find physicians to conduct their clinical trials. Pharmaceutical companies also paid us to list their trials that were recruiting patients.

And then I began writing stories that bit the hand that fed us.

As I learned more about the clinical trials industry, I came to understand that it could best be described as a commercial enterprise, as opposed to a scientific one designed to actually assess the merits of new drugs. Trials were often biased by design; there was selective publication of data that helped promote the drug’s commercial success; and academic “thought leaders” lent their names to this marketing enterprise.

We sold the company in 1998, and that was when I went to the Boston Globe and proposed doing a series on the abuse of psychiatric patients in research settings. Yet, and this is important, at that time I still believed in the larger story of progress that psychiatry had been telling to the public. Researchers, I believed, had discovered that major illnesses like schizophrenia and depression were due to chemical imbalances in the brain, which the medications then put back into balance, like “insulin for diabetes.”

The series reflected both of these perspectives. One part of the series focused on the testing of atypical antipsychotics, and how, among other things, a number of the patients who volunteered in the trials had died, and yet those deaths had not been mentioned in the articles published in medical journals. We wrote about the money being paid to the academic psychiatrists to conduct the trials, and told of specific examples of how that financial influence had led several astray, so much so they ended up either in prison or censured by a medical review board.

Another part focused on studies in which antipsychotics had been abruptly withdrawn from schizophrenia patients, with researchers then tallying up how frequently they relapsed. We said this was unethical, since the drugs were understood to be “like insulin for diabetes.” Who would ever conduct a study that withdrew insulin from a diabetic, and then counted how frequently their symptoms returned?

As I have written before, that would have been the end of my reporting on psychiatry, except for the fact that, just as the series was being published, I came upon two research findings that belied that story of progress. And that made me wonder whether there was a larger story to be told.

On to Mad in America

The research findings were these. First, the World Health Organization had twice found that schizophrenia outcomes were much better in three “developing” countries than in the United States and other developed countries. Second, Harvard Medical School researchers had reported in 1994 that schizophrenia outcomes today were no better than they had been a century earlier. It was then that I asked myself a new question, one that could be said to have arisen from my schooling in “evidence based medicine” while I was director of publications at Harvard Medical School.

Was it possible that psychiatry, as an institution, was deluded about the merits of its therapies? The conventional history of psychiatry tells of how the introduction of Thorazine into asylum medicine kicked off a psychopharmacological revolution, a great leap forward in care. But if one dug into the “evidence,” both historical and scientific, did it support that conclusion?

In Mad in America, I reported on a trail of history and science that contradicted the conventional wisdom. The book might be best described as a counter-narrative. It told of a medical profession that, for various reasons, had become committed in the 1960s to telling a story of how helpful the new antipsychotics were, and how that commitment grew stronger when DSM-III was published in 1980 and psychiatry adopted its “medical model” for diagnosing and treating mental disorders. After that, the American Psychiatric Association’s public pronouncements about the biology of mental disorders and the efficacy of psychiatric drugs turned into a full-bodied PR campaign, and academic psychiatry was—in the language of institutional corruption—”captured” by the pharmaceutical industry. Academic psychiatrists, starting in the 1980s, began working for pharmaceutical companies as speakers, advisors, and consultants, and once this “economy of influence” developed, these “thought leaders” told a story to the public that, again and again, pleased their financial benefactors.

There were many parts to that “counter-narrative,” but here are three such examples.

- I wrote that the simple dopamine hyperactivity theory of schizophrenia really hadn’t panned out, and that in the early 1990s, a leading psychiatrist in the United States had concluded that the hypothesis “was no longer credible.” This was at a time that the American Psychiatric Association was regularly informing the public that “we now know” that major mental illnesses like schizophrenia and depression are caused by chemical imbalances in the brain.

- I wrote that the drug-withdrawal studies cited by psychiatry as proving that antipsychotics provided a long-term benefit were flawed, as they compared drug-maintained patients to drug-withdrawn patients (rather than to a true placebo group), and it was well known that once schizophrenia patients had been on antipsychotics, they were at great risk of relapse if they abruptly stopped taking the medication.

- Based on documents that I obtained through a Freedom of Information request, I wrote that FDA reviewers of the risperidone and olanazapine trials had concluded that they were biased by design against haloperidol, and that the trials did not provide evidence that these new antipsychotics were safer and more effective than the old drugs. This was at a time that the atypicals were being touted by academic psychiatrists, in their pronouncements to the press, as “breakthrough medications.”

Now, in a sense, I was climbing out on a journalistic limb here. The history in Mad in America told of a profession that was deluded about the merits of its own therapies, and had practiced—as the book’s subtitle said—“bad science,” which in turn led to the “enduring mistreatment of the mentally ill.” This did not endear me to a number of people in the psychiatric establishment, but in the years after Mad in America was published, what did we subsequently learn?

- The chemical imbalance theory had in fact failed to pan out by this time. As Pies memorably wrote in a 2011 blog, “the chemical imbalance theory was always a kind of urban legend, never a theory seriously propounded by well-informed psychiatrists.”

- In 2002, shortly after Mad in America was published, psychiatrist Emmanuel Stip wrote that when it came to the question of whether antipsychotics were “effective” over the long-term, there was no “compelling evidence” on the matter. The relapse studies did not provide such evidence.

- In trials conducted by the NIMH and other governmental agencies, the atypical antipsychotics were not found to be superior to the first-generation antipsychotics, which led Lancet to pen this memorable editorial: “How is it that for nearly two decades we have, as some put it, been ‘beguiled’ into thinking they were superior?” Lancet wrote that in 2009, seven years after Mad in America was published.

In short, I had followed a journalistic path—asking questions and searching through documents—to tell a history in Mad in America that countered what psychiatry, as an institution, had been telling the public about chemical imbalances and telling itself about the “evidence base” for its medications. And here’s the point: If academic psychiatrists had been telling the public that the biological causes of major mental disorders remained unknown, and that the relapse studies did not provide good evidence that antipsychotics provide a long-term benefit, and that the atypical trials were biased by design against the old drugs, then I would not have had much of a book to write. It was psychiatry’s own failures, in its review of its science and its communications to the public, that invited a journalist to challenge its “ownership” of this story.

On to Anatomy of an Epidemic

In Mad in America, I had explored the thought that antipsychotics worsened long-term outcomes. This is obviously a question that any medical specialty ought to ask itself—how do its therapies affect patients over longer periods of time—and yet it was not a question that psychiatry, as an institution, had answered. It had relapse studies that it pointed to as evidence that antipsychotics needed to be taken on a continual basis, but I couldn’t find any instance where psychiatry had compiled an “evidence base” that these drugs—or any other class of psychotropics—provided a long-term benefit.

That was the hole in psychiatry’s evidence base that I sought to fill when I wrote Anatomy of an Epidemic. And in this book, I simply sought to put together a narrative of science, from psychiatry’s own research, that could best provide an answer to that question for the major classes of psychiatric medications. I was indeed stepping outside the usual journalist’s role in taking up this task, but I sought to do it only because of psychiatry’s failure to address this issue in any substantive manner.

As I had already learned from writing Mad in America, putting together such a narrative requires that you push past the abstracts and discussion sections in published articles to focus on the data. Anyone who has spent time reading psychiatry’s scientific literature will discover that, if the data is unfavorable to the drug, you often can’t rely on the abstract for an accurate summation of findings, and that the discussions can lead you astray. The abstracts may be spun to downplay the poor results, and the discussions may gloss over the poor results, or seek to explain them away. Often, the data itself—if the results are poor for medicated patients—may be presented in a confusing fashion. You have to learn how to deconstruct the study, based on the data that is presented, to best understand the results.

This type of spinning and obfuscation can be seen in many NIMH-funded stories. For instance, in the STAR*D study, which was touted as the largest antidepressant trial ever conducted, the investigators promoted the notion that two-thirds of the 4041 patients that entered the trial eventually remitted. If a patient’s first antidepressant didn’t work, try another, and eventually an antidepressant will be found that does work. However, nothing like that actually ever happened in the study. Only about 38% of the patients ever remitted (according to the criteria set forth in the protocol), and the graphic that presented the one-year outcomes defied being understood. It took years before an enterprising psychologist, Ed Pigott, figured out that graphic, which told of how only 108 of the 4041 patients had remitted, stayed well, and in the trial to its one-year end. Thus, the documented stay-well rate was 3%, which is a far cry from the 67% remission rate promoted to the public.

Similarly, in the TADS study, the investigators made it appear that just as many suicide attempts had occurred in the non-drug groups as in those exposed to Prozac, which was the conclusion suggested in the abstract. In fact, 17 of 18 of the youth that had attempted suicide had been on the medication. In the MTA study of ADHD treatments, you had to read very closely to see that medication use was a “marker of deterioration” at the end of three years, and that at the end of six years, the medicated children had worse outcomes.

In sum, as I said at the beginning of this post, I agree that writing a paper like the Case Against Antipsychotics is outside the usual domain of a journalist. Pies and Pierre are right about that part. But the only reason I came to write in this way about psychiatry is because psychiatry, as an institution, so obviously failed to fulfill its scientific duty to the public. This institutional failure was an important part of the journalistic story I sought to tell in Mad in America, Anatomy of an Epidemic and most recently in Psychiatry Under the Influence, a book I co-authored with Lisa Cosgrove. It’s not that I set out to trespass on psychiatry’s turf and write reviews of the “evidence base” for its drugs. Indeed, from a journalistic perspective, I am reporting on how the scientific literature contains a story, regarding the long-term efficacy of its drugs, that psychiatry is not willing to tell to the American public (or to itself.)

Deconstructing the Quality of Life Studies

With this context in mind, we can now turn to the claim by Pies and Pierre that there are two well-designed, placebo-controlled trials that showed that antipsychotics improve the quality of life of schizophrenia patients. This claim can provide a test case of what I have been writing about here: Do we see, in their reporting on the study, the critical thinking our society would like to see in those who tell of the “evidence base” for psychiatric drugs? Or do we see yet another example of how leaders in American psychiatry, in their communications to the public and to their peers, draw a conclusion that will support what they want to believe and support their clinical practices, even when such a conclusion is not supported by the data?

In short, we will want to see whether their interpretation of the study reveals a devotion to using clinical research to improve patient care, or using it to boost a belief in their profession.

S. Hamilton, et al. (1998). Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: quality of life and efficacy results of the North American double-blind trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 18: 41-49.

Authors: This is a study that was conducted by Eli Lilly as part of the trials it conducted to get Zyprexa approved by the FDA. The study was authored by employees of Lilly Research Laboratories.

Methods: Investigators at 23 clinical centers recruited patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, ages 18 to 65, into the study. The patients were mostly a chronic group, with a mean age of around 36. After being enrolled, they were hospitalized and abruptly discontinued from their antipsychotic medications. They were kept off such medication for four to seven days, and any “placebo responders”—those who got better during this period—were washed out of the trial. Those who were suffering from an “acute exacerbation” of symptoms at the end of that washout phase were randomized into one of five treatment groups: placebo, three olanzapine groups at different dosages, and haloperidol at a daily dose of 15 mg. All patients at randomization were given a Quality of Life Score (QLS), which became their “baseline” measurement for assessing later changes in their quality of life.

All volunteers were hospitalized for the first two weeks, and then were discharged during weeks two to six if they “responded” to treatment (a 40% decrease in psychotic symptoms). At the end of six weeks, “responders” were entered into an extension study designed to last another 46 weeks, with their quality of life assessed at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52. The researchers hypothesized that those treated with olanzapine would show superior improvement in their QLS scores than the placebo patients, with this benefit persisting throughout the year-long study.

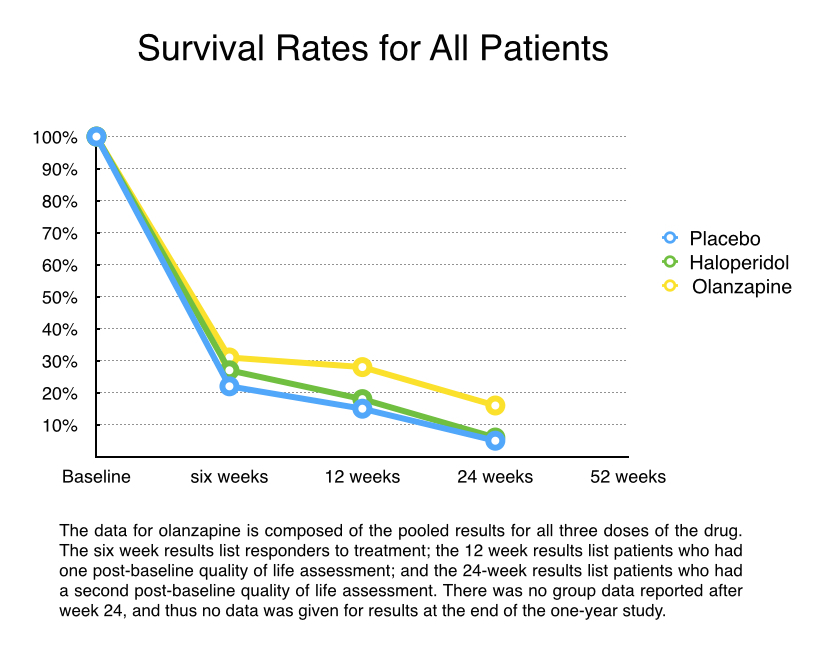

Results: There were 335 volunteers randomized into the five treatment groups (67 each). Only a minority of patients (28%) responded to treatment in the first six weeks and continued into the extension part of the trial. Of the 95 patients who entered the extension trial, only 76 survived another six weeks and thus had one post-baseline QLS store (at week 12 from start of study). There were only three patients in the placebo group, 4 in the haloperidol group, and 33 in the three olanzapine groups who stayed in the trial to week 24 and thus had a second QLS assessment. There were no further detailed reports of QLS scores because so few patients stayed in the trial past the 24-week mark.

To calculate QLS scores, the Eli Lilly investigators used a Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) score for those who survived until week 12 but then dropped out before week 24, and then added this LOCF data to the 24-week scores for the 40 patients who stayed in the trial to that point. The Lilly investigators reported these findings:

- The olanzapine patients who responded to the drug during the first six weeks had much better QLS scores at 24 weeks than they did at baseline.

- The olanzapine responders showed significantly more improvement in QLS scores at the end of 24 weeks than the placebo responders.

- There was no significant difference in improvement in QLS scores for the olanzapine and haloperidol responders.

Conclusion in published paper: “Improvement in quality of life was observed in olanzapine-treated responders.”

My interpretation

a) The study is unethical.

As psychiatry regularly informs the public, schizophrenia patients who abruptly stop taking their medication are at great risk of suffering a severe relapse, which puts the person at high risk of suicide. There is also worry that after such a relapse, a person may not regain the same level of stability following the resumption of medication. In this study, the abrupt discontinuation was expected to lead to an “acute exacerbation of symptoms.” Then one-fifth of those patients would be left untreated and go through weeks of withdrawal symptoms.

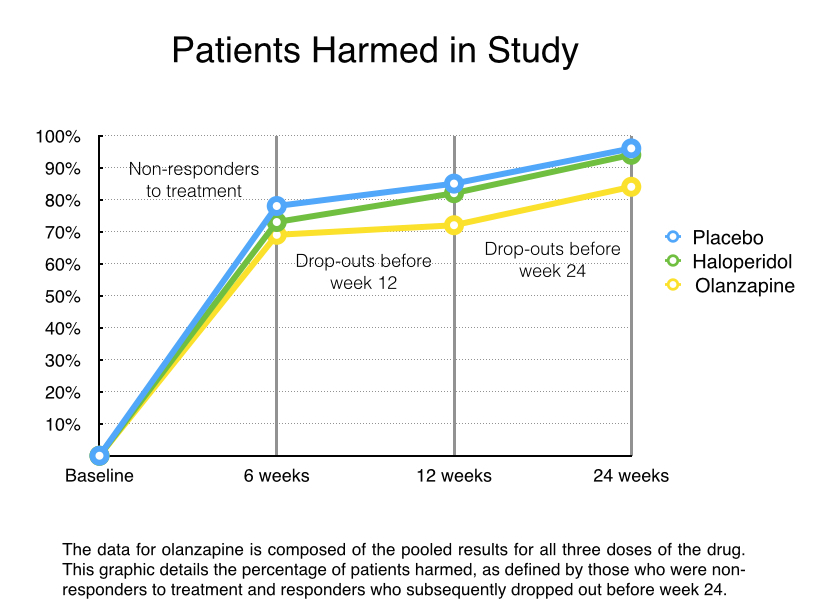

Thus, all 335 patients randomized into the study were exposed to harm (abrupt discontinuation of their drugs), and 67—the placebo group—were exposed to extended harm.

All told, 240 of the 335 patients (72%) failed to respond to “treatment,” and thus could be counted as harmed in the study. In addition, 55 of the responders then dropped out before week 24, and given that they were in clinical care at the start of the study, this drop-out result would seemingly tell of harm done. Thus, 295 of the 335 patients who entered the study (88%) either failed to respond to treatment or dropped out of care by week 24.

The investigators did not report on adverse events or suicides, and they provided no information of what happened to non-responders following week six. However, when I reported on the atypical trials for the Boston Globe, I discovered that 12 of the 2500 volunteers in the olanzapine trials had died by suicide. If that rate held true in this study, one or two of the 335 volunteers would have killed themselves, their deaths properly attributed to a study design that put all of the volunteers in harm’s way.

b) The study is biased by company authorship.

This was a study of olanzapine conducted by Eli Lilly: it designed the study, analyzed the results, and reported the results. It was a study designed to produce a marketing blurb, which is that its drug produced a Q of L benefit over haloperidol and placebo.

c) The study is a failed study.

The endpoint for this study was quality of life at the end of 52 weeks. However, there were so few volunteers who made it past week 24 that no results were reported after that date. Thus, the study failed to provide evidence that olanzapine provided a Q of L benefit that persisted, as had been hypothesized.

d) The study is biased by design against “placebo.”

The patients randomized to “placebo” were going through abrupt withdrawal from antipsychotics, and were then left untreated for withdrawal symptoms. Given what is known about the hazards of abrupt withdrawal, this “placebo” group could be expected to fare poorly.

This design lies at the heart of psychiatry’s self-deception, and the gaping hole in its evidence base. Pies and Pierre write in their paper of focusing on “placebo-controlled studies,” as such studies are seen as the gold standard in clinical research. But psychiatry has very few true “placebo-controlled” studies in its research literature. What it has is an abundance of studies where patients abruptly withdrawn from their medications are dubbed a placebo group, which means they masquerade as a placebo group. This is psychiatry’s dirty little secret, and like all dirty little secrets, it is conveniently kept hidden from the public, and as this hiding goes on and on, psychiatry convinces itself it really has “placebo-controlled studies” that it can cite.

e) There is no evidence that olanzapine improved the quality of life for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The baseline QLS score in this study was taken when patients, having been abruptly withdrawn from their medications, were randomized into the treatment groups. Thus, the baseline score told of Quality of Life when the patients were suffering from a withdrawal-induced exacerbation of symptoms. This set an artificially poor baseline score.

Furthermore, to assess whether a drug improves quality of life for a group of patients, it would be necessary to collect QLS scores for all of the patients randomized into the study, and do so at all of the scheduled assessments (weeks 12, 24, 36 and 52). In this study, we know that 69% of the patients treated with olanzapine failed to “respond,” and thus this group could be expected to have a poor Q of L score. Another 15% of the olanzapine patients dropped out before week 24, and thus we might imagine that their quality of life was not so terrific at that point. In order to draw any conclusion about the effect of antipsychotics on quality of life in this study, even in relation to the artificially poor baseline score, you would need to report the scores for all patients.

In short, the results reported in this paper are for a small, select group of good responders to olanzapine (16% of the initial patients), and not for all of the patients treated with olanzapine.

f) The bottom-line results

From a scientific perspective, the design set up this comparison: in patients who had been ill on average about 9 to 10 years, the study compared outcomes for those who were abruptly withdrawn from their medications and then put back on an antipsychotic to those who were withdrawn and left untreated for that withdrawal. The study found that there was a higher response rate for those placed back on olanzapine, and also found that in a select group of olanzapine responders, their Q of L scores had improved notably in comparison to when they were going through abrupt withdrawal. At the same time, the study found that chronic patients withdrawn abruptly from their medications and left untreated fared poorly, as could be expected.

H. Nasrallah, et al. (2004).Health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 65:531-36.

This study suffers from all of the same defects as the olanzapine study, plus one. The study was funded by Janssen, the manufacturer of risperidone. Most of the authors of the study were Janssen employees, and the lead author was psychiatrist Henry Nasrallal, who disclosed he had financial ties—including serving on speakers’ bureaus—for Janssen and a number of other pharmaceutical companies. A 2014 “Dollars for Docs” report by ProPublica showed that Nasrallah had been paid by 14 pharmaceutical companies for some service or another from August 2013 to December 2014.

The volunteers recruited for the study—a slightly older, more chronic group than the patients in the olanzapine study—were abruptly withdrawn from their medications. It appears that “placebo responders” were then washed out from the study, although this is not clearly stated. The 369 patients were randomized to placebo, or to three groups given different dosages of injectable risperidone (along with an oral dose of risperidone for the first three weeks).

As was the case with the olanzapine study, the placebo group was composed of chronic patients exposed to the hazards of abrupt drug withdrawal, and left untreated for those symptoms.

The study authors do not provide any details about the fate of all 369 patients. There is no information on study dropouts. The authors simply report that at the end of 12 weeks, quality of life had deteriorated in the placebo group, and had improved remarkably in the three risperidone groups. Patients given a 25 mg. dose of injectable risperidone were reported to be enjoying a quality of life at the end of 12 weeks similar to the general U.S. population, with their mental health now just as good as the average Joe’s. The chronic patients, it seemed, had been restored in 12 weeks to near physical and mental “normalcy,” a result so remarkable it reminds one of stories from the Bible.

Pies and Pierre Report the Results

In their article, Pies and Pierre assert that only caring clinicians, such as themselves, are capable of evaluating the evidence base for their patients. Journalists who dare to do so should be seen as guilty of journalistic malpractice, and given that I have now offered my opinion on the merits of these two studies, I imagine they would want me reprimanded anew.

For their part, Pies and Pierre informed readers that in “both studies, patients treated with the antipsychotic showed significantly greater improvement in Q of L than those treated with placebo.” Moreover, they wrote, “Nasrallah et al found that long-acting risperidone (25 mg.) improved Q of L to levels not significantly different from normal.”

And thus the relevant question for society: Does their review of the evidence in this case instill confidence that they can be trusted as the keepers of the evidence base for psychiatry? Or do we see the very type of assessment that made me skeptical about this medical specialty in the first place?

Ah, credentialism…the last refuge of the scoundrel. These psychiatrists are so consumed by their inferiority complex — like Rodney Dangerfield, they get no respect from the other medical specialties — they leap at the chance to lord it over a journalist, even as the evidence against antipsychotics mounts. For all their preening, these guys are industry hacks, and their “scientific” bona fides are on the par with tobacco company science that used to tell us that nicotine was not harmful or addictive. For a a fascinating look at what is possible when psychiatrists stay out, Pies & co. should read Suzanna Cahalan’s Brain on Fire. This young woman made a complete recovery from madness because, for once, psychiatrists of all stripes (those representing the drugging establishment as well as the Freudian dogmatists) knew their place, did not muscle their way in (unlike in the Justina Pelletier case), and let the real doctors and real science do their work.

Report comment

GetItRight,

There’s a vested interest among all doctors to diagnose brain illness rather than a psychological situation – because this allows them to earn money as prescribers gives them control.

At the start in 1980, I thought Psychiatrists only talked to people and I asked for talking treatments. After a number of years of unsuccessful chemical treatment I was diagnosed very badly. But I then cut the drugs moved to psychology and recovered. So I was right to begin with.

I have thirty years of genuine recovery now.

Report comment

Fiachra, I love your story and wish it were everyone’s story. You must have had an uncommonly, extraordinarily capable and effective therapist. Lucky you. I myself believe that “mental illness” or whatever passes for mental illness — psychiatric symptoms is a better phrase — can have psychological as well as biological etiology. I just abhor psychiatric drugs and would look for natural healing therapies in addition to psycho-social support.

Report comment

Thanks GetItRight,

I did have a lot of very good social and thereuptic support.

Report comment

We see the very type of assessment that made you skeptical about this medical specialty in the first place.

I’d also love to know why Pies and Pierre think it’s appropriate for the current ‘bipolar’ treatment recommendations to recommend combining the antidepressants and / or antipsychotics. When all doctors are taught in medical school that combining these drugs classes can actually create symptoms which appear to the psychiatrists as the positive symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ via anticholinergic intoxication syndrome / anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

And the neuroleptics can also create symptoms that appear to the psychiatrists to be the negative symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ via what’s medically known as NIDS.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-Induced_Deficit_Syndrome

And since neither of these iatrogenic, neuroleptic induced syndromes, which mirror the positive and negative symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ are billable DSM disorders, out of sight out of mind, they are no doubt almost always misdiagnosed.

How do Pies and Pierre distinguish between these neuroleptic induced syndromes and the so called ‘real schizophrenia’? Because I know none of my psychiatrists were able to do this. Thankfully, after researching medicine for 10 years and pointing out to a doctor with a brain, that psychiatric drug induced anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning was neither ‘bipolar,’ nor ‘schizophrenia.’ I was finally able to get those misdiagnoses / defamation of my character off my medical records.

And I will mention that another historic ‘dirty little secret’ of the psychiatric / psychological industries is that those industries have been profiteering off of covering up child abuse and easily recognized iatrogenesis for ‘the two original educated professions’ for decades, according to an ethical pastor of mine. And this would, of course, give insight into why ‘the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).’

Report comment

I made this point below. We cannot even trust that these studies are comparing comparable groups, the reason being that schizophrenia as a diagnosis lacks validity.

Report comment

Ditto.

Report comment

I agree, BPDT, as does Dr. Thomas Insel, the former head of the NIMH. So why are we, as a society, still utilizing the DSM for “mental health” “diagnosing” and billing? The sad truth is, the DSM is a classification system of the iatrogenic illnesses created with the psychiatric drugs, and of course the medicalization of the human condition, so people can be railroaded into the psychiatric system.

Report comment

A professional who commented on Dr. Pies’ article stated that he could attest to the fact that quality of life declines precipitously during the time patients come off their medications. He contended that if those in a placebo group are suffering from withdrawal during the course of a study, that could skew results considerably and asked if any studies compared outcomes with medication naive groups or subgroups.

Dr. Pies answered that there are no such QOL studies that he is aware of. He said such issues could be dealt with by very slow tapering (usually 3-6 months). But he also claimed that “supersensitivity psychosis” because of withdrawal is speculative, and he dismissed the commentator’s observations by saying the concept of a withdrawal effect is only theoretical. Of course, in his article he claimed a superior ability to judge the effects of psychiatric medication because of his work with patients. So apparently anecdotal evidence is important, but only if it doesn’t contradict Dr. Pies.

Report comment

Marie,

It’s the story of the continuing mistreatment of the “mentally ill”.

In my opinion there’s nothing speculative about ‘supersensitivity syndrome’ – if I hadn’t learned how to carefully withdraw from drugs 30 years ago, I’d still be ‘Care in the Community’ in Ireland Today.

Report comment

“In my opinion there’s nothing speculative about ‘supersensitivity.”syndrome.”

Interestingly, mainstream psychiatry recognizes other withdrawal effects; for example, delirium due to alcohol withdrawal. They refuse to acknowledge the effect of withdrawal from psychiatric drugs because they peddle them.

Report comment

Hi GetItRight,

I think its well known that withdrawing anything that relieves “anxiety” will result in worse “anxiety” than was there to begin with.

Report comment

I’m ‘antidotal’ evidence people suffer from ‘drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis,’ even after, according to my medical records, being ‘properly’ weaned from the drugs for years, not months. So, I’m quite certain, Pies is wrong.

The reality is the psychiatric industry generally does not want to wean people off the drugs, and so they do not currently know how to do so properly, period.

And like Whitaker points out, one’s brain acquires too many dopamine receptors, to compensate for a dopamine antagonist / neuroleptic / antipsychotic, because brains are neuroplastic, and do try to compensate for the harm being done to them by the drugs.

But this compensation by the brain being attacked by neuroleptics, can result in a drug withdrawal induced manic psychosis, when one is weaned off the drugs, even over several years. And this withdrawal induced side effect can occur at a much later period of time than today’s psychiatric industry, which does not have any financial motives to study how to wean people off of drugs at all, and has no financial desire to research such, believes.

The reality is today’s psychiatric industry is only interested in research that proves their drugs are ‘wonder drugs.’ And has done next to no research into how to wean people from their drugs, so has next to no expertise into how to heal people from the harms of the psychiatric drugs.

I absolutely agree that when a medical specialty becomes so self-intersted and profit only motivated, it is the journalists’ duty to investigate such a corrupt industry. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for the work you’re doing, Robert Whitaker.

Report comment

If you’re pushing dope, it’s better if your stuff is addictive. That way the customer always comes back for more.

Report comment

.`..he claimed a superior ability to judge the effects of psychiatric medication because of his work with patients. So apparently anecdotal evidence is important, but only if it doesn’t contradict Dr. Pies. SPOT ON!

Another problem is that psychiatrists will DIAGNOSE the `schizophrenia’ etc but since they spend no more 10 minutes at a time with most of their patients, it could be said that that SEE them but they don’t actually KNOW them at all. I wonder how many times Dr Pies has sat with a patient over a period of hours per day for several weeks? I have, and they were some of the most wonderful, insightful and courageous, `severely impaired,’ `profound[ly] suffering’, `the ravages of schizophrenia’, people I have ever known. `Critics of psychiatry who have never spent time with patients and families coping with the simply do not grasp the human tragedy of this illness.—in which antipsychotic medication usually plays an important role’ in maintaining a dreadful QOL. I suggest most psychiatrists belong more to those who never spent time with these suffering people partly because they write them of as incurable, chronic uninteresting detritus to be drugged to a standstill and not bother anyone, particuar

ly them.

Report comment

Yes. Plus if they spent too much time with us they might realize that we are human beings. That would make it more difficult for them to torture and defame us.

Report comment

One thing about these two psychiatrists that’s certain – they have not honesty, nor humility, nor shame.

Thank you, Robert, for your dedication to the truth.

Report comment

Psychiatrists are biased. They don’t want to believe their beloved treatments do any harm. How about talking to those of us whose lives have been ruined by anti-psychotic drugs? We know firsthand the harm they cause.

Report comment

Spot on Robert! As a PhD student in nursing, it is common knowledge that all research studies are not without bias. These two psychiatrists only offer the research findings to reinforce their argument. That’s the game, isn’t it? It’s the same for evidence-based medicine or evidence-based practice: if the evidence is poor, then the outcomes will be poor!

Report comment

“But psychiatry has very few true “placebo-controlled” studies in its research literature. What it has is an abundance of studies where patients abruptly withdrawn from their medications are dubbed a placebo group, which means they masquerade as a placebo group.”

Wow! Wow.

Liz Sydney

Report comment

“Journalistic malpractice”, if there were such a thing, as far as I’m concerned, would be a matter of a journalist trying to pass fiction off as a news story, that is, blatantly lying. The half-truths and innuendos of people who are supposed to be medical professionals is another thing altogether. Typically, if the shots were intended for you, they miss entirely as these studies they come up with are practically irrelevant to the case you are making. What have we got here? Two basically short term drug company funded studies of chronic mental patients. This research has to have very little to do with how well people fare long term off or on psychiatric drugs, as it was only looking at the short term, and to the neglect of any patient never exposed to such drugs.

Canadian psychiatrist, and historian of psychiatry, Edward Shorter does something similar with other critics of conventional psychiatry. He dismisses some studies of a psycho-sociological nature as examples of 1970s agenda. He claims that some studies, and histories, too, are based on a lack of understanding of medicine. He would have historians trained in medicine. Not so much of a problem, except in so far as it is probably absolutely unnecessary when it comes to developing such an understanding, and also, as in his case, it could mean a conflict of interest. “Conflict of interest?,” you say. Yes, the lauded author of a history of psychiatry is also a professor of psychiatry. I don’t see how that couldn’t, in some sense, have a negative effect of his sense of objectivity.

http://dhayton.haverford.edu/blog/2013/07/18/a-conversation-with-edward-shorter/

Report comment

You should see his treatise on ECT. He and St David Healy join forces for one of the worst, most biased, pieces of pseudoscience you will ever see.

Report comment

Great work, as always, Bob. Being sneered at by these guys is the ultimate compliment.

I’d love it if you could comment further on the “Placebo washout” approach described so clearly in the first study. It appears that they systematically removed anyone who got better when coming off antipsychotics. This always seems like a pretty sleazy maneuver to me. If you have people whose quality of life IMPROVES when they STOP the “treatment,” wouldn’t that be very important data? I’d love to compare the “washout” folks at 52 weeks to the Zyprexa users at 52 weeks.

All that being said, the most important point is that the study is meaningless, as they couldn’t even record their primary measure due to an incredibly high dropout rate. Not to mention that they only compared the QOL of the RESPONDERS! Isn’t that like saying that “people who experience pain relief when taking aspirin have less pain than those who didn’t experience pain relief?”

And of course, the other huge deal is that they selected out only these two studies as their best evidence to support their point, rather than looking at the whole of the literature. Such “cherry picking” is systematically criticized (and rightly so) when committed by those who disagree with them. Why are they allowed to get away with it?

The real message here is: “Trust us and don’t ask too many questions like that guy over there.” Or “Don’t confuse yourself with facts.”

Thanks for another excellent blog.

—- Steve

Report comment

Steve said: “I’d love it if you could comment further on the “Placebo washout” approach described so clearly in the first study. It appears that they systematically removed anyone who got better when coming off antipsychotics. This always seems like a pretty sleazy maneuver to me. If you have people whose quality of life IMPROVES when they STOP the “treatment,” wouldn’t that be very important data? I’d love to compare the “washout” folks at 52 weeks to the Zyprexa users at 52 weeks. ”

Yes! This was my thought exactly.

Their management of and failure to report on the placebo washout group is nothing short of academic malpractice…and there seem to have been so many of them. Throughout the study, they have conveniently excluded anyone who didn’t respond in a way that could be used to promote their drugs, and no real follow-up or explanation has been given. If a study starts with, say, 400 people, all 400 should in some way be accounted for at the end…including deaths, refusals, etc.

A study should NOT begin after you have excluded a whole bunch of people you recruited and then decided you didn’t like, because their reactions didn’t fit your preferences. It is academic dishonesty.

…and then for Pies et al to revert to anecdotal “evidence” from their years of “caring” for their patients as being superior to any data from any study…well….

Another excellent piece. Thank you Robert

Report comment

Sure. The Zyprexa folks are going to be a lot heavier than the control group.

Report comment

Ron Pies doesn’t indulge in clear thinking. Have a look at some of his attacks on Phil Hickey as well, when Phil took him apart for his famous 2012 claim that `the chemical imbalance’ was an `urban myth’ that nobody important had ever really supported. Of course Phil and many others demolished that, but the most telling thing was that he set himself up AGAIN and was demolished again. This is a thought leader of psychiatry?

Report comment

I am only one guy. But my experience on antipsychotics has been the stuff of nightmares. Rebound psychosis from going off seroquel? Check. Suicidal ideation on zyprexa? Check. Apathy on haldol? Check.

This is infuriating.

Great work Mr Whitaker

Report comment

Oh ya I forgot. I became psychotic because my doc put me on Wellbutrin which induced sixty days of insomnia.

Report comment

I’m surprised you were not offered a benzodiazepine, to which you would now be hopelessly addicted, given that the withdrawal symptoms are worse than those for heroin, are persistent, and can’t necessarily be treated by resumption of the drugs.

Report comment

I was put on Wellbutrin, too, for smoking cessation, not depression. It didn’t work, so I was abruptly taken off of it by my PCP. Then doctors and psychiatrists misdiagnosed the common symptoms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, as “bipolar,” a blatant misdiagnosis, according to the DSM-IV-TR of the time.

It seems some of the dumbest and/or least ethical people within society are now working within the medical community. Oh, that reminds me of something that crossed my mind while I was suffering through my drug withdrawal induced manic psychosis. I remember thinking that all today’s doctors were ax murderers in a previous life. And they supposedly were given positions of importance in society by God today, to test them to see if they could be good people when given a blest life. Medical mistakes are the third leading cause of death, guess many are still no better than ax murderers. Now I understand why Jesus supposedly said, all the doctors are going to hell. And I still hope that’s untrue, I’ve found ethical doctors with brains, but there likely will be lots of today’s doctors landing in hell, if there is such a thing.

Report comment

You remain standing. Their artillery tables were incorrect. God alone knows where the barrage impacted.

Report comment

Congratulations; psychiatrists are exposing the bankruptcy of their position when they attack critics rather than respond to criticism! The APA did the same thing with criticism of the DSM by defining problems as “clinically significant.” Your analysis of the data is correct and their criticism is weak- an affirmation.

Best wishes, Steve

Report comment

Only clinicians, with an expertise in assessing the research literature, should be weighing in on the topic of the efficacy of psychiatric drugs.

I did the ultimate research on the topic of the efficacy of psychiatric drugs, I took the stuff and as Anatomy of an Epidemic points out they keep you sick. Zyprexa almost killed me.

Since my recovery I have been working in the addiction field “dual diagnosis” and the stories are almost always the same, when I was a child they said I had ADHD started those drugs that made me feel like crap zoned out speedy then when I got worse they piled on more pills and called me bipolar. Must have heard that from 300 people since I started taking the time to ask.

This new client I met is in for methamphetamine, he seemed like he was doing ok to me upbeat and all and he comes back from the doctor and tells me the doctor said he was bipolar and started him on Cymbalta and Gabapentin.

I gave him the story on psychiatry but like a typical addict he took the crap anyway but WTF how the hell is Cymbalta and Gabapentin going to help someone who enjoys flying around on meth ?? Gee thanks Doc , I have that sick tired drugged feeling all the time so now I really don’t want to do any meth .

Then when he goes home and doesn’t follow through on aftercare he gets to have all the withdrawal reactions no one even bothered to warn him about.

Cymbalta and Gabapentin will make that guy “better” give me a effing break.

Psychiatry more harm then good , I see it like every day.

Report comment

This is another good point: the foremost “experts” on antipsychotic drugs are those who actually have taken them, like myself and The Cat. Why are we not hearing from these people?

Report comment

…and me. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) is EVIL. It creates a living hell and is a nightmare to come off. Since coming off it 6 years ago I haven’t even been close to being psychotic.

Report comment

“..Only clinicians, with an expertise in assessing the research literature, should be weighing in on the topic of the efficacy of psychiatric drugs…”

NO:- Because they can’t be trusted to tell the truth. (At the time) The President of the British Association of PsychoPharmacologists came from the University that managed my Psychiatric Unit + My Former Psychiatrist was on the examining board of the Royal British College of Psychiatrists AND my Records were still Doctored at Source:- Requested Adverse Drug Reaction Warning was intentionally omitted + Extra pyramidal disability was intentionally omitted; + Longterm Recovery as a result of stopping strong medication and moving to The Talking Treatments was intentionally omitted.

Report comment

Olanzapine (Zyprexa) is EVIL. It creates a living hell and is a nightmare

Evil, hell and nightmare are the three most common words used online to describe that poison. That crap made me so sick, when on it it robs the ability to feel pleasure from anything and then coming off it the withdrawal induces all the symptoms of the severe mental illnesses. It was given to me for the minor problems of anxiety and insomnia then withdrawal left me with what they labeled schizoaffective disorder during the blame the victim not the drug part when the victims try and get off it and get sick.

The most insidious diabolical part of Zyprexa / Olanzapine is that outside observers will say the person on it looks “better”. THAT in my opinion is what really makes that drug truly evil. Emotions down to zombie levels, motivation erased without total sedation “better”.

I wish I could do a better job of describing the effects of that wicked drug, I call it a robbery, the official term is anhedonia but words just don’t adequately describe.

Zyprexa is evil on the level of Thalidomide. It should be banned.

Report comment

It gets a bit long in the tooth. What happens to you or me or Captain Spock on drugs is what happens to you or me or Captain Spock on drugs. We don’t become instant drug-induced experts on the drug. And we don’t become sudden overnight insight-sensations about what the drugs do to other people. Almost all subjective drug experiences are best not mentioned in polite conversation unless — UNLESS! — you have a very rare gift for drug discourse. Which most don’t.

So stick to the science in which your self-proclaimed “expertise” disappears, as rightly it should.

Otherwise I have some sympathy for the sentiment.

Report comment

I agree, BPDT, we’re dealing with a debate between “experts” by experience vs. “experts” educated by pharmaceutical industry biased mis-information, whose livelihood depends on pushing these drugs. And keep in mind, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

The neuroleptic / antipsychotic drugs are “torture” drugs, just like the UN came out saying in 2013, in the opinion of this person who was forced to take almost every single one of the ‘atypicals,’ prior to finally being withdrawn from them, which was a staggeringly bizarre experience in itself.

Report comment

the cat:

yes, the ADHD gateway to bipolar is common in my experience too; and also these young people start doing opioids (and eventually heroin too) after all the stimulant drugs

Report comment

I also see this frequently with foster youth. I never cease to be amazed that the obvious seems so obscure to those prescribing the drugs.

Report comment

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Report comment

So in other words, the meth user was doing far better on meth than he or she is doing on psychiatric treatment? The only problem there is that buying meth from a meth dealer is not legal. Given that meth can be prescribed as Desoxyn, he/she could get a prescription and live a crime-free life, sustained by the best medicine for his “condition.” It’s worth considering, if Cymbalta and Gababentin have left any part of the individual’s mind functioning and havene’t destroyed the will to live. Those two drugs are the stuff of living nightmares. I’d sooner inject Desoxyn than allow one tablet of either to enter my body orally. Anyone who doubts the wisdom of this should visit surviving-antidepressants.com and read the histories of people whose enjoyment of life, whose ability to remain neutral as opposed to suffering and suffering deeply, has been destroyed by those two pills. The emotional pain is not depression and it’s not psychological angst. It’s a torment much deeper than thoughts and beliefs can access, and is relentless, it seems.

Report comment

Robert: Perhaps you should write a short commentary (reply) to that journal. It might save time however, if you write to the editor first and ask if he/she would consider a reply commentary. Also, it might be worthwhile to get a clinician to be a co-author.

By the way, the following two research studies that have shown the same changes in brain scans in patients who respond to placebos and patients who take an actual drug might also come handy if you do decide to write a commentary (to mention that drugs can work sometimes for individuals because of their placebo effects, etc.).

http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2443355 http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2443354

Report comment

I believe its now accepted that the “Atypicals” were not superior to the original drugs. They caused more health problems, shortened life expectancy and were a lot more expensive:-

In 2005 in the UK the “typical” neuroleptic Mellaril was taken off the market “on account” of its heart rythm effects.

Mellaril was replaced with “atypicals” like Seroquel. But the difference between the two drugs was that Seroquel was 50 times more expensive and a lot more dangerous in terms of heart rythm effects.

(Seroquel carried a black box warning in America and was banned in the American military because of its lethal effects)

Report comment

I think the “Atypical” promotion was a type of Professional and Official fraud that siphoned off a lot of money and killed a lot of vulnerable people.

Report comment

I agree, Fiachra.

Marcia Angel’s book:

https://www.amazon.com/Truth-About-Drug-Companies-Deceive/dp/0375760946

Is a great book pointing out the fraud of me-too drugs, including all the so-called “atypical antipsychotics.”

Report comment

Thanks Someone Else,

It’s a big Back Scratching/Money Laundering arrangement:-

“….Angell says, most of the R & D work is done by colleges and universities funded by the government. …”

Report comment

Wow Pies and Pierre just got owned. That is truly embarrassing to have the two studies they cited exposed like this, as industry-funded, dropout-full, withdrawal-biased, scams…

They just keep make it worse for themselves by opening their mouths / uncapping their pens.

Robert, well done with this careful analysis. It’s much easier for you because your professional status and your income don’t depend on the maintenance of myths favorable to corporations which funds the APA, psychiatrists training programs, universities, etc.

I still think you should not kowtow to Pies/Pierre’s use of “schizophrenia” as if there were such a singular disease entity, something Pies even admitted there probably is not in a footnote to his latest essay. The uncertainty of whether there is a valid coherent entity called schizophrenia adds another wrinkle into how to evaluate these studies. How can we even trust that comparable groups are being compared in these studies given that the diagnoses are invalid?

And lastly, let’s get one thing straight: these are tranquilizers, not medications treating a disease. Seroquel and Risperdal are tranquilizers not medications, simple as that. The ord medications only serves the myth that psychiatry wants to sell, i.e. that severe problems in functioning/living are brain diseases. I hope you will start to separate yourself from repeating that euphemism.

Report comment

“They just keep make it worse for themselves by opening their mouths / uncapping their pens.”

Not at all, because their article is being read by mostly psychiatrists and some other mental health professionals, who take everything they say on face value, a tiny percent of which would ever actually come here and read Whitaker’s.

Report comment

Robert, what would an ethical study on antipsychotics look like?

Report comment

After all Mr. Whitaker who are you to challenge Dr. Mengele?

Report comment

Was it Dr. Mengele who blinded Jewish children in Nazi concentration camps?

At any rate there was an MD (certified with a doctorate in medicine) and legally certified nurses who held down screaming children with brown eyes and put blue dye in. Hey, they were “helping” to normalize the children with nice, blue Aryan eyes! The fact that this only blinded them was an unfortunate side effect of the “medication.”

Being a doctor doesn’t absolve one of being a pathological liar and sociopath!

Report comment

Absolutely!

Report comment

Very readable and I appreciate the autobiographical details from local journalism to MIA.

Hope this doesn’t seem like an annoying diversion but

that commitment grew stronger when DSM-III was published in 1980 and psychiatry adopted its “medical model” for diagnosing and treating mental disorders.

Don’t you really mean the “biological” or “bio-medical” model? We were constantly talking about the medical model in the mid-70’s; it had, since Szasz started writing, traditionally referred to any belief in “mental illness” as an actual disease.

The other thing is: Can you provide a working definition of “evidence-based medicine”? It seems like you have two terms: “Evidence-based” (an adjective) and “evidence base” (noun). Is this a pun or play on words, or are we really talking about the same thing with both terms? I.e. “evidence-based” seems to mean “based on evidence.” “Evidence base” seems to refer to the amount and quality of evidence on hand. So you could have something “based on evidence” (depending on how one defines “evidence”) that’s not based on solidevidence, or consistent with other accumulated evidence. (Or maybe I’m just tired.)

Report comment

“Don’t you really mean the “biological” or “bio-medical” model? We were constantly talking about the medical model in the mid-70’s; it had, since Szasz started writing, traditionally referred to any belief in “mental illness” as an actual disease.”

I think you’ve got a really good point here, OldHead, and I don’t think it was adequately addressed by R. Whitaker’s response.

“I think what APA adopted in 1980 when it published DSM III was a “disease model” rather than a medical model, but I guess I was using the APA’s terminology in quotes.”

And what “model”, pray tell, would one oppose to a “disease model”? A “trauma model”?

I’m just wondering, where is the “oppression model”? There used to be a lot of talk about psychiatric oppression. Correct me if I’m wrong, but psychiatry hasn’t stopped being oppressive, has it?

Report comment

Disease model and medical model seem to be the same to me.

Another thing: “Model” of WHAT? When they say “model” it’s often followed by “of mental illness.” So we should consider that as well. ANY “model” of “mental illness” assumes the reality of “mental illness.”

Report comment

In other words, referring to the “medical model of mental illness” actually connotes acceptance of and employs the medical model by presupposing the existence of “mental illness.”

Report comment

I like both oppression model and trauma model, except (I know I’m starting to belabor this) what are they models “of”? What I’m getting at again is challenging the assumption that there is a “thing” that is now called “mental illness” but should really be called something else. This presumes a category or “thing” which has never actually been shown to exist in the first place.

Report comment

As a chemist by training, I have given this a lot of thought historically. By my understanding, a scientific model is an attempt to provide an explanatory mechanism for a phenomenon that is observed. Any good scientist knows that a model is only as good as its ability to predict the phenomenon in question and/or intervene to alter the outcome in predictable ways. Clearly, the “medical” or “disease” model has proven a total and abject failure in both ways.

The “oppression model” would be a means of explaining why people experience intense anxiety or depression or extreme states from the point of view that such experiences are likely a result of experiencing abuse or traumatizing experiences at the hands of another. We would also hope it might suggest ways of intervening to either prevent the oppressive conditions or to assist in analyzing how a person experiencing such conditions might act or be helped to act in order to alter the predicted outcome.

It doesn’t necessarily imply that the phenomenon in question is an aberration or in fact pass any judgement whatsoever about the phenomenon. It’s more like “when people are traumatized, they’re more likely to hear voices in their heads” or “people who hear voices in their heads are likely to have had a history of individual or social oppression.” The model certainly doesn’t require an acceptance of “mental illness” as a concept.

That’s my take on it, anyway. Good discussion!

—- Steve

Report comment

In re-reading this, I’m inclined to think that the Western approach to viewing “mental illness” or anything else having to do with human beings from a detached, analytical perspective is what creates a lot of the problem. People aren’t “problems” or “hypotheses.” Maybe being “scientific” takes the humanity out of the equation.

Report comment

There is no “reality” to “mental illness”. I’m not that fond of trauma theory, of course. I just see professionals using “trauma” to explain why some folks don’t “recover”, or aren’t “resilient”, and other folks, they would claim are more “normal”, are. I believe “trauma theory” is pretty much that explanation. This is amusing, somewhat, as the predominant “treatment” given for “mental illness” labels is “trauma”, and so many people aren’t quick to abandon their trauma providers. Actually, “trauma” is a more of a psychodynamic (talk therapy) explanation of sorts because so much of this “trauma” is psychological “trauma”, and psychological “trauma” is literally not “trauma”. Sure, perhaps “injury” makes more sense than “disease”, however ‘healing psychological trauma’ is an illusionists trick, and must be right up the shaman’s alley. What am I saying? Bluntly, injury is physiological, or it isn’t injury.

Report comment

psychological “trauma” is literally not “trauma”.

Ugh.

Report comment

Wow, this is *literally* an entirely different reality than mine. Not that it’s only mine, I know others share in the knowledge of the power of psychological abuse, injury, and wounding–as well as the healing of it. And I can accept and respect that this is not your belief or position, Frank, from what you state above. I see that this is your truth.

But I am so struck at the diversity of beliefs and realities that exist on the planet, even just on this one website. Whether people agree or not on basic items such as this, can they/we still co-exist peacefully? That would be my question at this time. Can we respect diverse realities, rather than to challenge the reality of another. Is that really anyone’s business?

That’s exactly my issue with the “mh” world–they want to challenge insistently, relentlessly, any perspective that does not ring true for them. And to my mind, that’s an extremely limited perspective (e.g., DSM). Nothing to explore there, it’s pretty black & white, which I think is a completely unrealistic read on anyone. Everyone is complex, and how they embody that is their business.

But if you don’t believe in psychological injury, then perhaps you will not recognize when it is happening? That is where I go with that. At least in my reality, that would be the case. Not yours, of course, because there is no such thing. But I would wonder about my psychological safety in that case, is all I’m saying.

Report comment

It is like “growth” for most of us after the age of 25, and there are educationalists who go there, and say that such “growth” never ends, in other words, I hear what you’re saying, but I’m also noticing that most of the “giants” they would be referring to are strangely small, and hardly beyond human dimensions.

Report comment

“It is like ‘growth’ for most of us after the age of 25”

This I understand and for the most part I agree with it. Perspective and good defenses are part of maturing.

Still, in a systemically oppressive community, psychological trauma (as I would define and perceive it) can be a way of life, and we don’t even notice it. Marginalization and the discrimination that occurs from this is chronic systemic and social trauma, most often unrecognized. But the effects of it are more than evident, and it is felt profoundly. I’d like to shine a big ol’ light on that.

And where there is marginalization and discrimination, there are marginalizers and discriminators. I’d like to shine an even bigger light on that–what I’d call ‘the shadow’ of our society. The gaslighters, bullies, manipulative liars, etc.–the ones who pass it along freely, poisoning others’ minds for their own gain OR protection, without a second thought…

Report comment

The “disease model” of mental distress better describes the medical model because it is a more basic description of their position. The disease model describes mental distress as a disease whereas the medical model implies that it is a disease by describing it as a medical subject.

Report comment

Yeah but see what I mean? You’re replacing “mental illness” with “mental distress.” I used to do the same thing, except using “emotional distress.” Thing is, only a certain portion of those labeled “mentally ill” are experiencing distress. Some are causing others distress. And some are exhibiting behavior that others find disturbing and confusing but they are fine with themselves. All these plus even more disparate personal circumstances are lumped together as varieties of “mental illness.” It’s like putting broken glass, hypodermic needles and jellyfish into a scientific category because you can hurt yourself stepping on them at the beach.

Report comment

I absolutely love the way you put things oldhead! So relatable, so true!

Report comment

My biggest “distress” came in discovering that I was going to be committed to a state hospital, that is, detained and stripped of my liberty. Nobody had an adequate answer for that kind of “distress” whom I encountered. Nobody had an answer for that kind of “distress” that didn’t wind up increasing it. I spent time in a psychiatric prison, and I was very relieved, of “distress” and so forth, when I was eventually ‘discharged’ from it. Tight spots increase “distress”, but I could definitely do without that kind of “treatment”, should it’s tacit reason be for the relief of “distress” or what have you.

Report comment

I believe that the term “medical model” has evolved over time. Before 1980, the medical model referred to understanding “psychoses” (of Freudian Theory) as medical problems; afterwards, the medical model expanded to refer to all mental distress. The “disease model” and “medical model” refer to the same thing; is the “disease model” a better term?’

Report comment

No, again, unless you first define what you’re talking about models OF.

Anything “treated” by a shrink is a medical model approach.

Report comment

I am describing models of social welfare problems of “mental distress” (emotional distress or emotional suffering in reaction to distressful experiences) and “anti-social” reactions to the distress. I am referring to social welfare problems rather than medical problems. I believe there is enough census for definitions. Although, you are correct that there is nothing “there,” society regularly discusses abstract behavior patterns.

Report comment

“Society” is also an abstraction. 🙂

Report comment

I think you may be right, Steve. The psychiatric theology seems to describe a model of social welfare problems.

For example, child abuse is a social welfare issue. And covering up child abuse, so most people in society don’t hear about our society’s lack of protection for children, does seem to be the number one function of the psychiatric industry today.

This is why there are so many foster children drugged by psychiatrists. This is why “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).”

The psychiatrists offer society a quiet, albeit un-Constitutional, way to cover up embarrassing societal problems.

Report comment

A quote from Richard Nixon, “If a doctor does it, that means it’s medicine.”

Maybe we should keep doctors away from everything emotional.

Report comment

Thank you once again Robert Whitaker for speaking the truth about psychiatric drugs. My son went through a 2 week psychosis over two years ago with very minimal meds (benzos) for a few days just for sleep. Using an Open Dialogue informed approach, he came through the experience using a home respite with family with him and trying to connect 24/7. Since then, he has not experienced a recurrence. He continues to work through some issues, pain and existential challenges related to growing up with his therapist who is also a mindfulness teacher. I cannot say enough positive things about the power of simple meditation and living in the present. He and several of us have started meditating and found it very helpful with anxiety, worry and mood regulation.

All of this together has kept us moving forward individually and as a family with minimal use of meds. Long term meds are NOT necessary for recovery from all experiences of psychoses and other extreme experiences and overuse may actually interfere with the insights that may be gained with dialogue and mindfulness practices. I say this as a parent, a peer and as a clinician. Each of our expertise counts and we all have the right and the duty to examine the research and weigh in on the use and overuse of medications in psychiatry.

Report comment

Hi Truth in Psychiatry,

Whenever I read your wonderful story, I worry that psychiatrists like Pies will dismiss your input by saying that your son had a “brief psychotic disorder” and that people with brief psychotic disorder do recover quickly, and that psychiatrists see this happening frequently after standard ‘best practice’ in the hospital.

Indeed when my loved one was in the hospital and put on antipsychotics, we were told that being on antipsychotics would ‘hopefully just be for a couple of months’. The problem was that for our loved one, milder symptoms morphed into much more serious symptoms first after forced commitment, (what kind of logic is behind separating people from the people they know and trust at the time when they are experiencing troubling thoughts and confusion over reality!), and then again after drugs were introduced , withdrawn and changed. Of course the ‘narrative’ of psychiatry insist that all worsening symptoms are always due to ‘illness’ not ‘drugs’.

I wish so much we had been able to give our loved one the type of support that you gave your son –and wonder if our story would be more similar to your story if we had.

This is one of those many areas that psychiatry refuses to consider – does their “treatment’ (immediate use of antipsychotics, lack of ‘wrap around’ support from loved and trusted people etc.) change the trajectory of some people from having ‘a brief psychotic disorder’ (to use psychiatric terms) to something more severe and chronic. If psychiatrists believe in brief psychotic disorder (and they do) why on earth does their ‘best practice’ not, AT THE LEAST, include a ‘wait and see’ period of at least 6 months, before subjecting people to drugs which they know have such huge effects, when they themselves know many may recover quickly without them,