I was browsing the gift shop of the Glore Psychiatric Museum in St. Joseph, MO. Freudian Sips read the print on a bright yellow coffee mug. I smiled, attempting to restore a sense of levity after processing the exhibits I’d just explored. Maybe I should buy one of the Glore Museum branded squishy foam brains, I thought. A few squeezes might help ease the images in my mind’s eye away from a permanent residence in my own medial temporal lobe. I kneeled and inspected another souvenir. Would the women in my yoga class find me odd if I wiped my brow with a State Lunatic Asylum towel?

Glore Psychiatric Museum documents the history and legacy of State Lunatic Asylum No. 2. The asylum was the second state-funded facility for people labeled mentally ill to be established in the state of Missouri. It opened for business on November 9, 1874 when it accepted 25 inhabitants from among residents of the Buchanan County Poor Farm and Fulton Missouri’s State Lunatic Asylum No. 1.

State Lunatic Asylum No. 2’s construction followed a style known as the Kirkbride Plan. Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride was a physician and a founding member of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane. In his treatise, The Construction of Hospitals for the Insane, he makes a case for the institutionalization of those considered insane:

“There is abundant reason why every State should make full provision, not only for the proper custody, but also for the most enlightened treatment of all the insane within its borders. Most other diseases may be managed at home. Even with the most indigent, when laboring under ordinary sickness, the aid of the benevolent may supply all their wants, and furnish everything requisite for their comfort and recovery at their own humble abodes. It is not so, however, with insanity; for while all cases need not leave home, the universal experience is, that a large majority of them can be treated most successfully among strangers, and very generally, only in institutions specially provided for this class of disease. It is among the most painful features of insanity, that for its best treatment, so many are compelled to leave their families; that every comfort and luxury which wealth or the tenderest affection can give, are so frequently of little avail at home; and that as regards a restoration or the means to be employed to effect it, those surrounded with every earthly blessing, are placed so nearly on a level with the humblest of their fellow beings.”

The “enlightened” treatment Kirkbride referred to involved housing mentally ill people in hospitals with staggered wings that allowed fresh air and sunlight to permeate the building. But as Kirkbride discloses later in the same publications, this benevolent view of institutionalization was not solely because of his belief in the potential for healing within asylums. He also thought “insane” individuals had great potential for violence:

“The dangers incident to insane persons being at large, are much greater than is commonly supposed. Not a week, scarcely a day, indeed, passes without the public press containing the details of some occurence [sic] resulting in loss of life, or serious injuries to individuals, or destruction of property, from a neglect of proper care and supervision on the part of their friends or the public authorities, of those who had become insane and irresponsible for their actions. Very many of the cases of suicide that are reported very clearly belong to this class, and of those a large proportion, there is good reason to believe, were curable if their cases had been understood and properly treated. It is worthy of note, too, that many of these acts, even those of peculiar atrocity, are often committed by individuals who, with all their obvious mental infirmity, had previously been regarded as perfectly harmless.”

When State Lunatic Asylum No. 2 was established, patients would be seen walking the grounds of the hospital, playing card games, relaxing on benches, and lounging in swings. This treatment of patients changed as time passed. By the 1930s, the asylum, now renamed State Hospital No. 2, had become more crowded. Three other facilities, State Lunatic Asylum No. 3 in the city of Nevada, State Hospital No. 4 in Farmington, and St. Louis County Lunatic Asylum had been built, but the perceived need to house a growing population of insane Missourians drove the occupancy of State Hospital No. 2 to almost 3000 patients.

A fire destroyed the original building on January 25, 1879. A new facility replaced the burnt structure by 1880. The new building was designed to hold about 1/3 more people than the original design, which had been planned to house 275 residents. Kirkbride’s well intended but distorted view of those considered insane wouldn’t forecast the treatments humans housed within the walls of the hospital would endure once personnel and resources became scarce during World War I and World War II. Well-intended early 20th century treatments for mental illness became increasingly inhumane and invasive.

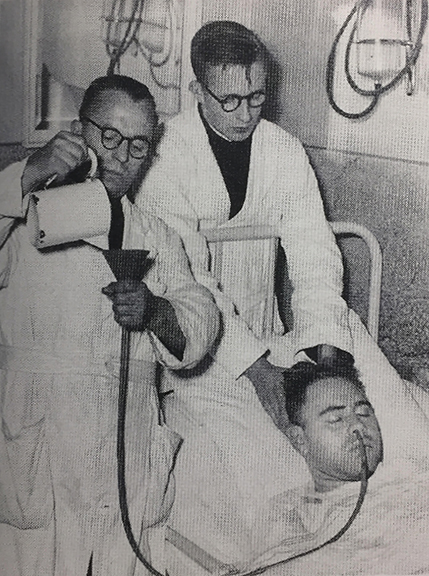

The first such treatment was Insulin Coma Therapy. During such a treatment, a patient was given several high doses of insulin to induce severe hyperglycemia. The treatment was invented by Austrian-American psychiatrist Manfred Sakel. Sakel believed insulin comas relieved psychosis by combating the adrenal system. He worked to popularize his theory in the early 1930s. Insulin therapy was finally abandoned by psychiatry in the 1950s.

Metrazol Convulsive Therapy was a strategy used to treat people diagnosed with schizophrenia. It was invented by Hungarian neurologist Dr. Ladislas Meduna in 1934. Dr. Meduna believed that epilepsy was incompatible with schizophrenia, so concluded that inducing seizures in schizophrenics might be therapeutic. The therapy was discontinued in 1941 after side effects such as broken bones led practitioners to decide the alleged benefits were not worth the risks involved in the treatment.

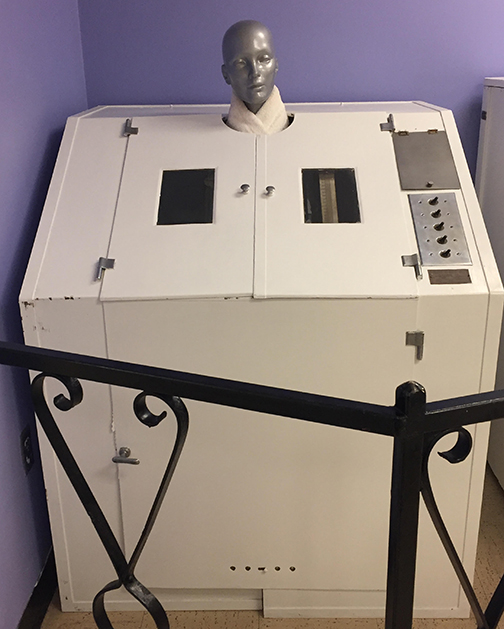

Among the other treatments showcased at the museum was Fever Therapy, a procedure during which a patient was placed in a cabinet designed to raise the body temperature above 105 degrees. The fevers were induced in attempts to cure patients of syphilis until physicians learned in the 1940s that the disease responded to penicillin.

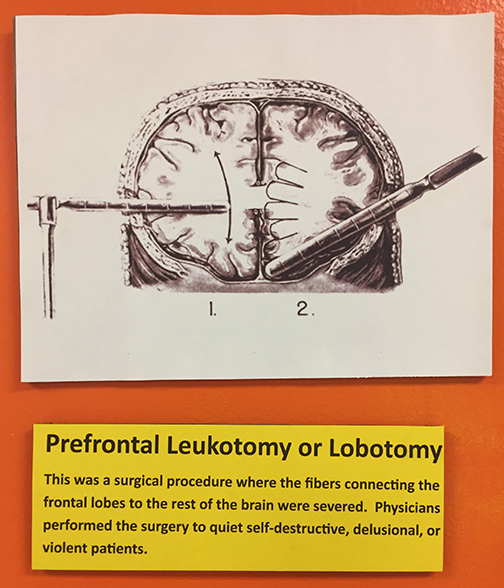

Lobotomies became popular in the same era. In 1936, neurologist Dr. Walter Freeman and neurosurgeon Dr. James Watts performed the first prefrontal lobotomy in the US in Topeka, KS. By 1942, the two had performed over 200 prefrontal lobotomies.

In 1946, Dr. Freeman completed the first transorbital lobotomy. The transorbital or “ice-pick” lobotomy didn’t require a neurosurgeon or an operating room. According to the exhibit at the Glore Museum, over 40,000 people were eventually lobotomized in the United States.

Some practitioners loved lobotomies because they made patients docile and manageable, but critics of the era pointed out the ethical implications of using such a strategy for patient management.

In 1948, mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener remarked, “Prefrontal lobotomy has recently been having a certain vogue, probably not unconnected with the fact that it makes the custodial care of many patients easier. Let me remark in passing that killing them makes their custodial care still easier.”

Electoconvulsive therapy, or ECT, arose as a treatment in 1938. It began to replace Metrazol and Insulin Shock treatments in the late 1930s.

My mind returned to the present era while viewing the ECT exhibit. The treatment is still used today, despite critics’ assertions that it causes brain damage.

The exhibits I discuss here are only a small slice of the history on offer at Glore Psychiatric Museum, but they prompted me to consider several questions. How far have we come in the US in terms of what we view as acceptable treatment for the many conditions collectively referred to as mental illness? How far has medicine come in uncovering the multitude of potential causes for the widely varied mental states experienced by so many of us?

Many self-proclaimed mental health advocates promote ending a perceived stigma surrounding treatment of mental illness. The same people usually promote the use of psychiatric medications to treat said illnesses.

The questions some of us pose to the advocates, such as whether antipsychotics are overused to reduce aggression in certain patients, are reminiscent of the questions surrounding earlier, more grossly invasive psychiatric treatments. More questions remain, such as whether other side effects, such as severe weight gain, are acceptable trade-offs for the relief psychiatric drugs may or may not offer.

I wonder if a Mental Health Awareness Month campaign in 1940 would have led to greater humanization of mentally ill people, or if it would have just paved the way for more lobotomies?

Some people who speak or write about mental illness deride any research efforts that seek to reveal physiological reasons for mental distress. They assert that most or all states described as manifestations of mental illness are due to trauma and stress, and can be alleviated by resolving issues associated with adverse life events.

Psychiatry’s troublesome history, as well as its current practice, have led other people to reject the validity of all psychiatric diagnoses and treatments. Former patients or psychiatry survivors sometimes choose to embrace the label of ‘mad’ as a way of affirming their distinct ways of thinking, feeling, and interacting with the world.

Few people look to psychiatry to cure the symptoms they present with. Most hope to establish relationships with providers who will find the right cocktail of drugs to help them simply get by for the foreseeable future. Pills that will lessen the frequency or severity of their suffering, but never alleviate it. That dynamic leads some to believe psychiatry isn’t the place to search for a cure for mental distress. Those who celebrate complete recovery from former psychological afflictions often laud lifestyle modifications offered by dietitians and exercise physiologists, or treatment protocols offered by endocrinologists and immunologists.

I think all these voices and perspectives are important. It is my hope that if we listen to each other, and learn about one another’s lived experiences, all while promoting and consuming heavy doses of research and science, humanity will be on the right course for finding ways to celebrate, co-exist with, or survive divergent or troublesome mental states. This is what humane and enlightened mean to me.

I was tempted to buy a Glore Psychiatric Museum branded hip flask, but thought it might be overkill for my herbal tea. I paid for a packet of Freudian Slip sticky notes and headed for the exit. Outside, the sun glinted off the razor wire that helps confine the men incarcerated by the Missouri Department of Corrections, which transformed the hospital building into a state prison in the 1990s.

More questions flowed through my mind.

Will there ever be places in the Western world where we can live peacefully among one another — mutually respectful, mutually respected, and unconfined? What kind of behaviors would such a utopia require from each of us, and would the realm of medicine need to play a role in achieving those behaviors?

Perhaps considering such a fantasy is simply insane.

Thanks, Twilah, what a sad and ugly history we have of being inhumane to our fellow humans…

I love this quote you gave: “Let me remark in passing that killing them makes their custodial care still easier.” I think it captures the essence of what so many REALLY want from those in their families who has ‘issues.’ It’s a sad history of abuse, victim blaming and being too busy to help those we claim to love…

Sam

Report comment

Sleep problems changed to BiPolar 1 – Really: Before I begin, my friend was diagnosed BiPolar 1. The Clinic She was going to is a State runned Clinic. She was on a sliding scale going by her Husbands income, which she paid $40.00 per visit for Medical services, suddenly in Jan/Feb 2016, the Clinic demanded a payment of half of her accumilated debt/bill ie $2000.00 and refused any further Med Services till a $2000.00 was made. She was forced to go to a different clinic, and was unable to get her regular psych drug perscriptions. We carefully researched safe methods for withdrawing her off the Medication, and Suceeded. She had No psych drugs for over a year with No adverse events, ZERO. In January 2017 She was incarcarated for a dui conviction and served 37 days. Becuase of her previous history with Psych drugs, the DOC automatically put her in the MHU at the prison. She was confined to her cell 24/7 until she agreed to take a cocktail of psych drugs. The Prison must have assumed she was still on her past meds, in fact she was clean. Eventually she gave in and started taking the drugs so she could get out of her cell. When she got out (37 days total) she stopped the drugs they gave her, at Home she took Busparone for a few days then stopped. This sent her into Psychosis from withdrawel, EMS refused to take her to the Hospital, we both called 911 so many times I lost count, her psychosis got worse and worse, finally after two weeks, she was locked in the bathroom. The State came and took her to the Hospital then to the local Mental Hospital. She was in bad shape. I found out later (OVERDOSED THE CUT OFF OR WAY DOWN SUDDENLY)She was given 60mg Haldol, 8mg Ativan and 25mg of Thorozene,PER DAY for 21 days, just before her release they cut her down to 15mg of Haldol and sent her home. This put her into withdrawel from Haldol and Ativan. At home 3days she took an overdose of one of her perscriptions – Verapamil, the Hospital kept her overnight then sent her and back on 15mg Haldol(10 at bedtime and 5 in the Morning) In only 2 days she cut her wrist, She had Akathesia so bad she “could not get comfortable” she had Redsless body Syndrome. She called 911, they gave her Ativan at the Hospital and stablized right away, back to Mental Hospital, they gave her Ativan and Seroquil since then She is stable. Instead of taking responsibility for overdosing Haldol and Ativan they are Accusing me( Volunteer PCA for 6 years) of not giving her, her Meds and thats why she tried to kill herself. This is Total BS.

Report comment

The State of Alaska really care’s, they care about pillfering as much money ad they can from unsuspecting tax paying residents, WOW

Report comment

Haldol is nasty crap! No one deserves to be put on this seizure-maker. Taking that stuff was sheer torture. Kept experiencing violent thoughts and psychosis–eyes rolling back in my head and horrible Parkinson’s symptoms. Doctor claimed Haldol never caused those things–it must be my schizoaffective illness. 😛

Report comment

In Europe there were institutions that had families of physicians and staff living-eating-playing with patients. It was not unknown to have a former patient become a professional . Frieda case of Dora is an example.

Rorschach -who developed the test had some interesting thoughts worth exploring and the test itself.Food for thought.

Thanks for exploring I don’t think I could have done it!

And thanks for bringing up incarceration.

The private prisons and private detention centers all need voices.

What I long for is more of a solid network of folks working together to institute a new narrative and change but I still like your hope

Why not try?

Report comment

In the late 1700’s there was a doctor named Philippe Pinel who struck the shackles from the inmates of the insane asylums in Paris. He was helped and supported by another doctor named Jean Baptiste Pussin. Pussin employed former inmates in the asylum that he ran because he felt that they were kinder and more compassionate in their care of the inmates. This is probably the first example of peer workers. He himself was a former patient of the very asylum that he was head over. He and his staff were examples that contradict the lie that people are “mentally ill” for life!

We’ve been trying to overhaul and reform the system for a long time.

Report comment

Thank you for this much needed reminder of the history of psychiatry and the “mental health” system. I think it’s brilliant to ask what an “anti-stigma” campaign would have looked like in 1940. Couldn’t have actually happened in 1940, though, because psychiatry was thoroughly tied to the eugenics movement at that time. The whole point was that “mental patients” were seen as sub-human.

http://www.brown.uk.com/teaching/HEST5001/joseph.pdf

“The 1942 ‘euthanasia’ debate in the American

Journal of Psychiatry” by Jay Joseph.

Report comment

They still see “mental patients” as subhuman. You won’t catch them trying cruel, pointless experiments on unwilling people from any other part of society. They keep us alive–for now–because it’s financially expedient to sell their drugs. But it’s not a good life….

Report comment

Yes. In many respects, psychiatry is the same as it ever was. It’s worth remembering that the use of so-called “anti-psychotic” drugs was initially referred to by psychiatry as “chemical lobotomy.”

Report comment

Hello, uprising. One of the things the eugenicists didn’t catch was the positive medical aspects of the Schizophrenia Syndrome; e.g., resistance to viral infections, diabetes and cancer in addition to less likelihood of going into wound shock, and slower processes of aging. These were also found in first order relatives of such individuals.

Report comment

I’ve never been persuaded that anything like a “schizophrenia syndrome” actually exists outside of psychiatric dogma. What is your basis for taking that claim seriously? Isn’t the category of “schizophrenia” a vague catch-all for people who experience “psychosis,” which is itself a vague catch-all category of experience? How can we come to any scientific conclusions using vague abstractions like these?

Report comment

The psychosis I experienced was terrifying and disabling. It was a bad reaction to Anafranil which kept me awake for 3 whole weeks. That would drive anyone insane.

If I hadn’t panicked and gone to the psych ward–quite willingly–I would have slept a lot for a few days and recovered once the neurotoxin was out of my system. The second day I went off Anafranil cold turkey I was experiencing DT’s and exhaustion after sleeping twelve hours.

The doctor told Mom after 24 hours I should be better–and Anafranil didn’t affect people that way. I must have classic schizophrenia.

She panicked and told me. I panicked. The hospital refused to admit me (in those days you had to be dangerous) till Dr. Simpleton stood up for me. Or so I thought. Worst mistake ever!

Report comment

In their books, Hoffer and Osmond mentioned this, which I’ve seen to have some basis in reality. They thought it was due to the presence of excess adrenochrome and adrenolutin, two oxidized (and hallucinogenic) adrenaline derivatives, that influenced peculiarities of experience (yes-traumas can increase them). There could be a variety of sources inducing these chemicals’ production, hence there was no independent “schizophrenia”, as the so-called disease was only a collection of particular signs and symptoms, which could come from any number of sources.

Report comment

Yes, I am glad that you keep raising this issue for people to think about. The first gas chambers in Germany were not used by the Nazis but by German psychiatrists. They gassed the “mentally ill” by the thousands, referring to them as “useless eaters”. And of course, The German Volk did not want the genes of these sub humans infecting the body general of the German people, so they had to be murdered off at the permission of the German government. They were loaded up in trucks and bussed to six different cities in Germany, where the gas chambers were located. The families of these people were told that they died of natural causes.

Americans say that this could never happen here in America, but as you point out a euthanasia debate was carried out at the American Psychiatric Association’s yearly meeting in 1941 and the debate was continued in their Journal in 1942. We were sterilizing the “mentally ill” at this time by the thousands and German psychiatrists chided their government for letting the United States get ahead of them in this pursuit. I worry about the climate that is developing in our country over the past few months and where this might lead for those of us who are labeled as the “mentally ill”.

Report comment

Psychiatry is founded on violence and the judgment of others as “defective” in the eyes of society. “Modern” approaches are simply another way to force the “aberrant” back into line with society’s expectation. While individual psychiatrists may or may not be specifically committed to authoritarianism and invalidation, the entire field, starting with the diagnostic system, is still based on the primitive thinking that gave rise to “insulin coma therapy” and the like. While lobotomies are “out”, the barbaric ECT is still widely practiced, and of course, the drugs used on the brain are all based on stopping the brain from engaging in its normal functions in some way or another. So violence and invalidation continue to be the linchpins of the psychiatric worldview, even if individuals in the field are able to escape that viewpoint.

Report comment

Great point. Psychiatry will always be oppressive and dangerous because its foundational assumptions are flawed.

Report comment

If they were generous probably the days when they used opiates to treat mental illness were the kindest.

“In the Victorian era, the drug of choice was laudanum, a high-octane mix of ethanol and opium that packed just the chemical wallop it sounds it would. The drug was used as a painkiller, an antidepressant, and an antihysteric, and it often worked quite well” http://aycnp.org/opium_psychiatric_drugs_history.php

People all over are breaking the modern drug laws trying to self medicate themselves with opiates these days so I would imagine the time when they just gave you what people today often seek at great expense where possibly the times when the mentally ill were treated best. I don’t know I wasn’t there but I am sure psychiatry never needed much coercion or force to get patients to take their opiates.

Drug dependency itself is not that bad with many of them, its the maintaining the supply part in that turns it into hell.

Report comment

The fever therapy guys probably thought their treatment was quite humane, because the original version of it involved giving patients malaria, to induce the “therapeutic” high fever that was supposed to kill syphilitic spirochetes. The only drawback was that vivax malaria is a lifelong illness, which flares up every time one’s resistance to diseases is challenged by environmental extremes, such as getting soaked in the rain.

Report comment

Once the victim gets a “diagnosis” the sadists/demons get to torture the victim… and they get PAID to perform the torture service.

Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride and any other doctor at the time were genuine quacks as medicine still had not found the four blood types and had not discovered penicillin.

“The germ theory of disease had not yet been accepted in Vienna.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignaz_Semmelweis

Report comment

Even better evidence of quackery, the mortality rate was lower before medicine came to “help” in the year 1823. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignaz_Semmelweis#/media/File:Yearly_mortality_rates_1784-1849.png

Started washing hands in 1847, then seemed magicians with a new lower mortality rate, when they were causing the 20 years of disease in the first place.

I predict a similar chart would reflect the invention/ treatment of mental illness.

Report comment

Regarding a similar chart. I imagine NOT drugging the patient with poisons and waiting for “psychosis” to end naturally/ discussion of problem rationally/ physical problems discovered ( example. chronic lack of full sleep, B12 deficiency) and corrected.

Report comment

Semmelweis is a very sad story. He was apparently hospitalized after this happened because it drove him totally nuts that he had PROOF that hand washing worked and they just ignored it! So we have more proof that “mental illness” is CAUSED by the medical system!

Report comment

Dr. Semmelweiss was mocked and hated like Dr. Breggin is today. What? Change the status quo and inconvenience ourselves to save lives? I don’t think so.

Dipping your hands in soapy water is easier than switching drugging to talk therapy. Not only would you have to care about people you despise but your hourly income would drop from $800 an hour to a measly $200 minus the drug reps’ “little gifts.”

Report comment

Actually, the earliest psychiatric medicos did a better job before these alleged treatments came into vogue, if they were practitioners used the Quakers’ Moral Treatment instead of the various torments inflicted by guys like Benjamin Rush. There were probably two major reasons germ theory didn’t catch on in Teutonic Europe. One was that Pasteur, its prime originator, was a chemist and not an MD, and secondly, he was French.

Report comment

Right the Quakers and such, but before mankind had cities(24 hour light), we did not have mental illness.

Report comment

Very few of the Amish are in the mental system.

Report comment

We have two Kirkbrides in our area. In Athens, OH, Ohio University took over the local mental hospital and repurposed it for their own use. A few years back, my wife and I attended the Ohioan Book Festival in Columbus where we purchased the book on this Kirkbride from the author and OU professor.

In Weston, West Virginia, the former Weston State Hospital was purchased by a private entity. It is now used for tours, and Holloween events and has reverted to its original name-the Transallegheny Lunatic Asylum-this pre Civil War structure is on the National Register of Historical places. A certain flap occurred over the name change when a group of concerned anti-stigma mental health professionals complained about the name change.

Report comment

Oh, I bet they objected – but they weren’t afraid of stigma to the “mentally ill,” they were afraid of well-earned stigma for their own warped professional history!

Report comment

I was a “client” there serving a 30 day to life sentence in 1989. My sense of this flap was “what’s in a name.” It’s not as if the professionals contacted us for our in put regarding the matter. I similar flap occurred around the release of the film “Dream Team,” which all things considered, was a better take on mental patients than most.

Report comment

“No longer are you possessed by demons, able to be cured by trepanning holes into your skull. No, now you have a brain disorder, another invisible force inside you acting on you to cause you to feel and behave in ways that are separate from who you are as a person, and we call this method of recording unobservable phenomenonfaith-based science. We cant see it, but we just know it has to be there somewhere, because well, what the fuck else could it be? Unfortunately, the unseen, undetectable, psychiatric brain disorder is incurable. Thats right. You were better off when they were blaming the demons and boring holes in your cranium. Even back then, there is evidence that people survived the treatments and tried them again and again.”

This is so awesome read more here http://web.archive.org/web/20120607010903/http://bipolarbabbling.wordpress.com/

Shame this is only on the web archive now.

Report comment

Boohoo! Did you know Tasha Tracey is a pseudonym?

Shame on her. She needs to be out and proud. Donning a t-shirt that says “Kick me! I’m bipolar!” with a bulls eye target in back. Then she can organize all the “stigma reduction” parades. Leading the way with stirring slogans. “Please don’t hate me because I’m genetic garbage.” “I can’t help it I’m dangerous.” “Not my fault I’m a hopeless mess.” So empowering! 😀

Report comment

Your anti-stigma slogan shirts will be FLYING OFF THE SHELVES!!!

Report comment

Interesting post. We need more Gore, I mean Glore, Psychiatric Museums.

One thing I take issue with:

“I think all these voices and perspectives are important.”

I don’t. I think those voices and perspectives that support physically healthy ways of treating people, and don’t violate their law given age of consent rights, are much more important than those which would harm, confine, and ultimately kill the people in their charge. I think the issue is covered, acknowledged or not, under hate crime.

I’ve got a slogan that would work well on some item from the gift shop. “Clozapine is the new lobotomy.” It used to be said that the only thing that kept some people out of the hospital was a lobotomy. Now they say the same thing about Clozapine. Putting it out there might make people realize that they were dealing with real people, or not. Anyway, they’d be getting a bit of the understated truth. Clozapine IS the new lobotomy.

Report comment

Good point Frank Blankenship. I think I should have said, “We should be aware of all of these perspectives.” Because I agree we must oppose the voices that support harm, confinement, and murder as you so accurately point out.

Report comment