In World Psychiatry, Dr. Jim van Os and Dr. Sinan Guloksuz write a critique of the “ultra-high risk” and “transition” paradigm that has been pushed to the forefront in the last two decades of schizophrenia research. Dr. Van Os and Guioksuz argue that the “risk,” and “transition” concept is overly simplified, having negative effects on both research and intervention strategies.

Drs. van Os & Guloksuz begin their analysis and critique by discussing how the “CHR/UHR” framework creates problems in research. They suggest that samples are non-representative because the participants are most-often help-seeking.

“In practice, studies that want to apply the UHR/CHR paradigm have to search for young individuals who are slightly-but-not-quite psychotic and have expressed a wish to receive help. Sampling strategies differ widely from study to study and are based on a mix of advertising, service filters and active searches, thus per definition resulting in selected, non-representative samples that cannot readily be compared across studies.”

Moreover, studies often vary widely in criteria, especially exclusion criteria. Some of this variability is seen in studies where participants who have had previous use of antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, episodes of mania, drug-induced psychotic states are excluded which makes the study samples almost too dissimilar to be comparable.

The authors make the claim that early intervention programs for psychosis have fallen into the “prevention paradox” because “CHR/UHR” experiences are so rare that the early intervention approaches may not have a significant impact.

“The cost of ‘finding’ rare UH/GHR subjects is considerable, but not included in cost-effectiveness analyses of UHR/CHR research. Given the apparent rarity of UHR/CHR states, it becomes a priori unlikely that early intervention along the UHR/CHR paradigm will have public health impact.”

The authors then go on to critique the conceptualization of “Clinical High Risk” for psychosis and instead point out that this population may be more accurately be described as presenting symptoms of a “common mental disorder with subtle psychosis admixture.”

Most persons identified as “CHR” have a diagnosis of anxiety, depression, or substance use and fall within the “attenuated symptoms” classification. vanOs and Guloksuz point out that we can also think of these individuals as persons who have a “common mental disorder or a substance use disorder who also present with low-grade psychotic symptoms” and that “psychosis can thus be regarded as a transdiagnostic dimension of psychopathology.”

In this reappraisal of the UHR state, the authors point out that the current paradigm of UHR “risk” and “transition” emphasizes psychotic symptoms and misses psychopathological symptoms and experiences that compound and drive the level of severity individuals classified as “UHR” experience.

The authors also critique the concept of “transition to psychosis” because it is based on a quantitative and not qualitative shift from “risk” to “transition.” As a result of this, a one-point change on tools such as the CAARMS can tip an individual into “transition” and a classification of being ‘fully psychotic.’

The authors bring attention to the issue of false positive ratings of “transition” writing, “. . . false positive ratings of transition are likely to occur given the natural fluctuation in the severity of the transdiagnostic psychosis dimension within and between individuals.”

Moreover, the authors claim that the concept of “transition” does not help in predicting clinical functional outcomes. Further, the transition rate represented in research is likely to be inflated.

Adding to their case, the authors highlight a study finding that “. . . young people presenting to the service meeting UHR criteria had essentially the same 10-year transition rate (17.3%) as young people presenting to the same service with non-psychotic disorders (14.6%).”

The authors do not argue against the benefits of early intervention but instead, that “early treatment to young individuals with anxiety/depression/substance use and a degree of psychosis admixture as a marker of relatively poor prognosis would be useful for these individuals.”

“It may be more productive to consider the full range of person-specific psychopathology in all young individuals with mental health problems and to not become disproportionally fixated on the transdiagnostic manifestation of psychosis.”

****

van Os, J., & Guloksuz, S. (2017). A critique of the “ultra‐high risk” and “transition” paradigm. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 200-206. (Link)

According to my medical records, today’s psychologists and psychiatrists believe thoughts, gut instincts, and dreams are all “psychosis.” Meaning all humans who think for themselves, have gut instincts, or dream are “psychotic.”

I don’t personally know anyone who doesn’t, at least at times, think, have gut instincts, or dream. Which means anyone and everyone can be claimed to be “psychotic” by today’s “mental health professional’s” definition of “psychotic.”

Perhaps, a less all encompassing definition of what “psychosis” is, is needed?

Report comment

Oh, but I’ll add one thing. The antidepressants and antipsychotics are both known to create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. So when “mental health professionals” have concern someone may become “psychotic” in the future, the last thing that should be given to such an individual is one of those two drug classes, as well as the following drug classes.

“The symptoms of an anticholinergic toxidrome include blurred vision, coma, decreased bowel sounds, delirium, dry skin, fever, flushing, hallucinations, ileus, memory loss, mydriasis (dilated pupils), myoclonus, psychosis, seizures, and urinary retention. Complications include hypertension, hyperthermia, and tachycardia. Substances that may cause this toxidrome include the four ‘anti’s of antihistamines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and antiparkinsonian drugs[3] as well as atropine, benztropine, datura, and scopolamine.”

Report comment

Add benzo withdrawal :

“abrupt withdrawal may produce confusion, toxic psychosis, convulsions, or a condition resembling delirium tremens. ”

http://benzo.org.uk/BNF.htm

Report comment

Yes, withdrawal from the neuroleptics can also result in a drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis. But the medical community has delusions this is “a return of the illness.” It seems most of the psychiatric drugs can cause “psychosis,” which means the DSM is a classification system of the iatrogenic illnesses that can be created with the psychiatric drugs, as opposed to being a classification system of real “genetic” illnesses. Which would explain the huge increases in the number of people claimed to be “mentally ill.”

Report comment

Okay, so someone who’s perfectly sane has no imagination, intuition or sense of humor. I guess that explains shrinks’ behavior. Epitomes of normalcy that they all are.

Report comment

In 1800 about .004 percent of the UK Population were identified Lunatics.

In 1900 about .04 percent of the UK population were identified Lunatics.

In 2017 about 2.5 percent of the UK population are identified Lunatics.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_psychiatric_institutions

“..In Britain at the beginning of the 19th century, there were, perhaps, a few thousand “lunatics” housed in a variety of disparate institutions but by the beginning of the 20th century, that figure had grown to about 100,000…”

Report comment

Correct.

In 1880 in the United States, the prevalence of the insanity in the adult population (+20 years) was 0.34% (Census Office, 1888, p.23)

In 2016 in the same country, adult prevalence (+18 years) with any mental illness was 18.3% (SAMHSA, 2017, p. 2129), or 54 times more, and with serious mental illness, 4.2 %, or 12 times more (SAMHSA, 2017, p. 2135).

Psychiatry is a disaster on the way.

Census Office (1888). Defective, dependent and delinquent classes of the population of United States, as returned to the thenth census (June 1, 1880). Washington, Government Printing Office. Retrieved at: https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1880a_v21-02.pdf

SAMHSA (2017). Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. Rockville, Maryland 20857. Retrieved at

https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf

Report comment

If there was no “mental health treatment” whatsoever like in some very poor countries I think society would be far better off.

Report comment

“In 2015, there were an estimated 9.8 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States with SMI within the past year. This number represented 4.0% of all U.S. adults.” https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/serious-mental-illness-smi-among-us-adults.shtml

Report comment

4% in 2015 is 11.7 times greater than .34%.

4.2% in 2016 is 12.4% greater than .34%, and represents a 5% increase over the course of a single year.

If the .34% rate from 100 years ago had risen by 5% per year, we’d now be looking at 44%, leaving very few of the well to run the planet, since most of them would patrolling psychiatric prisons and injecting inmates with coma-producing doses of Haldol.

Report comment

Discover the truth about “schizophrenia”:

https://psychiatricsurvivors.wordpress.com/2016/06/19/schizophrenia-the-sacred-symbol-of-psychiatry/

Report comment

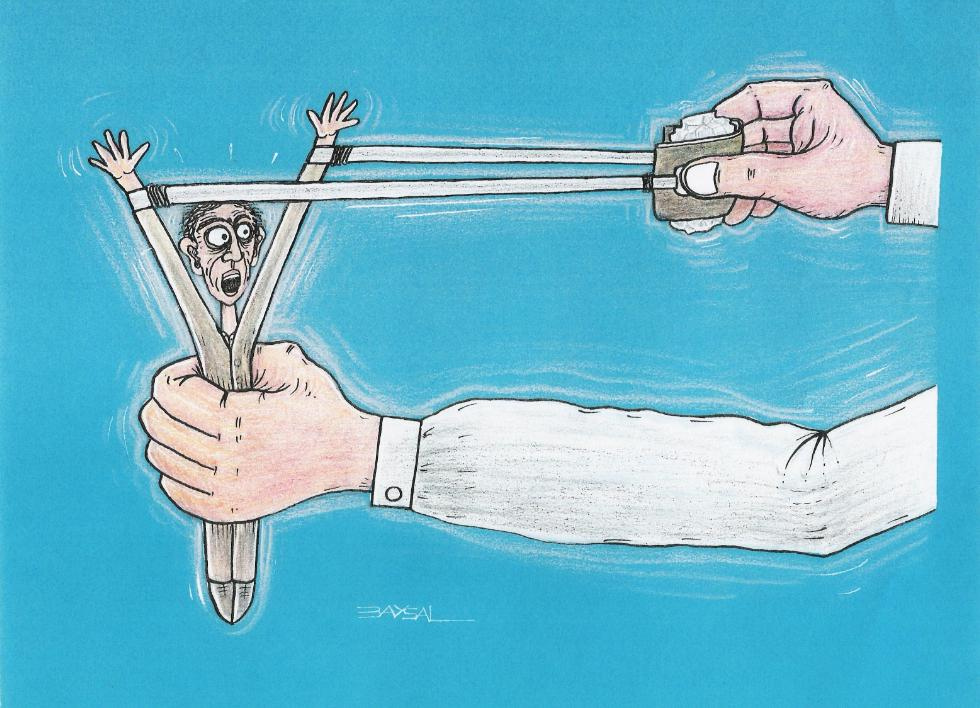

What a magical way to drum up business! Casting a “high risk” spell on certain individuals.

The field of psychiatry developed out of intolerance for human difference. Little wonder psychiatry should grow more intolerant with time.

Report comment

“slightly-but-not-quite psychotic”

Probably most of us after a few pints

Or a bad day at work

Report comment

Is this man Mentally Ill?

He makes a lot of sense to me.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eckhart_Tolle

“….One night in 1977, at the age of 29, after having suffered from long periods of depression, Tolle says he experienced an “inner transformation”.[5] That night he awakened from his sleep, suffering from feelings of depression that were “almost unbearable,” but then experienced a life-changing epiphany.[12] Recounting the experience, he says,…..”

“….He stopped studying for his doctorate, and for a period of about two years after this he spent much of his time sitting, “in a state of deep bliss,” on park benches in Russell Square, Central London, “watching the world go by.”…”

Report comment

How do we get more researchers to consider the TRUTH? That so-called “schizophrenia” is INVENTED, 100% subjective? It’s exactly as “real” as a present from Santa Claus, but NOT more real….????….

Real people have real problems. So why do the psychs insist on inventing imaginary diseases? So-called “schizophrenia” ONLY exists in the minds of those who believe in it. It’s *subjective* reality, NOT objective reality….

Report comment