William Compton, a professor of psychology at Middle Tennessee State University, investigates the myths associated with Maslow’s famous self-actualization theory in his article recently published in The Journal of Humanistic Psychology. Maslow’s theory proposes that individuals move through a needs hierarchy towards self-actualization, and Compton addresses criticisms that have been associated with the model, including hidden-elitism, lack of empirical backing, and the perception of happiness in self-actualizing people.

“Let us think of life as a process of choices…. There may be a movement toward defense, toward safety, toward being afraid; but over on the other side, there is the growth choice,” Compton writes, quoting Maslow. “To make the growth choice instead of the fear choice a dozen time a day is to move a dozen times a day toward self-actualization. Self-actualization is an ongoing process . . . [it is] little accessions accumulated one by one.”

Compton’s list of myths emerges from “many discussions with students and colleagues, reading numerous research articles, and reviewing many psychology textbooks over the past 40 years.” He defines a “myth” as a false belief and worries that if these false beliefs about Maslow’s theory are not rectified they may lead to a faulty understanding of self-actualization. Thus, utilizing Maslow’s published books and essays, Compton delineates common myths and attempts to respond to them.

Myth #1: “There is no empirical support for self-actualization theory”

Compton begins by reviewing studies on self-actualization theory that meet methodological standards for peer-reviewed journals, finding a substantial number of articles, including empirical studies, experimental replications, meta-analyses, and student theses. Compton identifies two research questions in reviewing the evidence:

(1) Do people move through the needs of hierarchy as Maslow proposed? and (2) Do Maslow’s characteristics of highly self-actualizing people indicate higher levels of mental health and well-being?

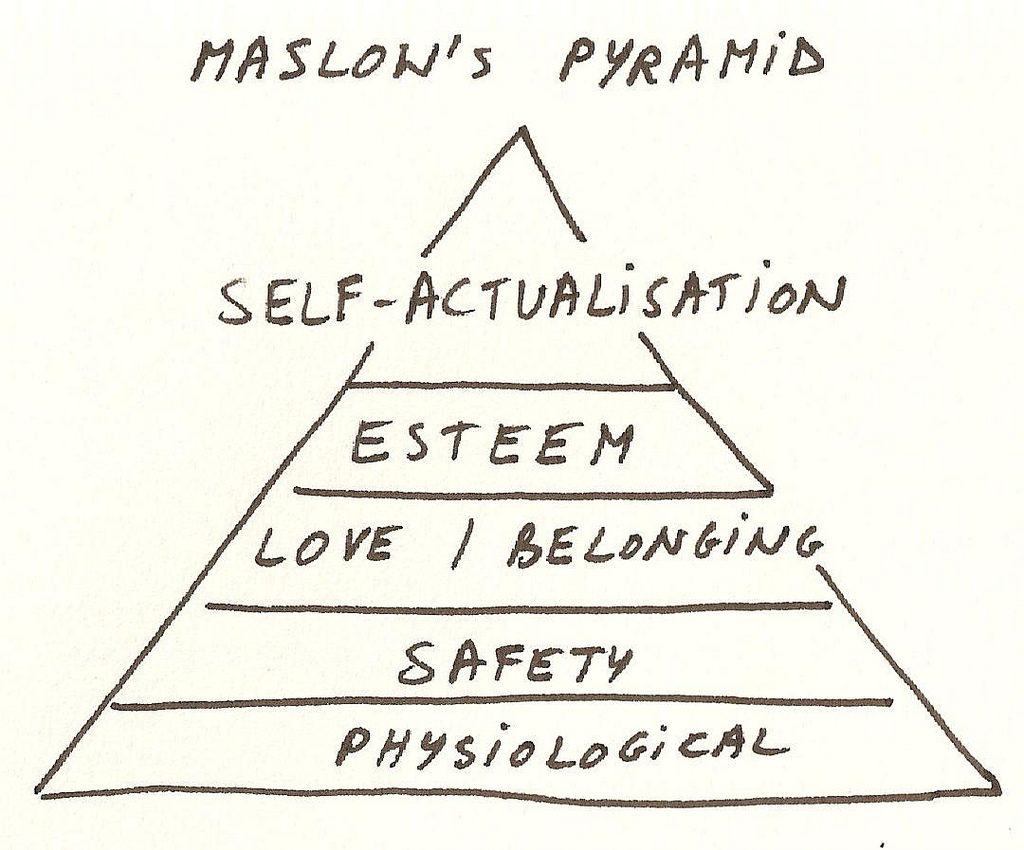

Compton found largely mixed reviews of whether Maslow’s theory was empirically supported, from being partially supported (i.e. important elements of the theory supported) to results indicating that it is too soon to make a conclusion. Researchers Wahba and Bridwell support Maslow’s claim that people motivated by lower needs in the hierarchy, including physiological, safety, belongingness, and self-esteem, operate under what he called D-needs (deficiency), while “highly self-actualizing people are motivated primarily by B-needs or Being needs, which rely on self-chosen internal goals and values for gratification.”

More recently, Compton found that progression through the needs hierarchy is more readily apparent at the societal level. Research at this level describes, “when basic needs are met for many people in a society then it is more likely for members of that society to be motivated by self-actualizing needs or B-needs.”

Compton’s second research question, whether highly self-actualizing people exhibit “above-average” mental health, is examined by juxtaposing various measures of self-actualization with one another. Self-actualization was found to have “significant relationships in the expected directions with measures of Carl Rogers’s theory of the fully functioning person, Frankl’s constructs of meaning in life and self-transcendence, Kohlberg’s theory of moral judgment, Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, Adler’s theory of social interest, creativity, internal locus of control, the tendency to have peak experiences, higher sexual satisfaction along with lower prudishness, as well as less fear of death.” Overall, research has found that scales that measure self-actualization are significantly correlated with measures of personal growth and mental well-being.

Myth #2: “Lower needs must be fully met before moving to the next higher need”

Compton debunks this myth with words from Maslow’s (1987) own writings:

“So far, our theoretical discussion may have given the impression that these five sets of needs . . . are somehow in such terms as the following: If one need is satisfied, then another emerges. This statement might give the false impression that a need must be satisfied 100 percent before the next need emerges. In actual fact, most members of our society who are normal are partially satisfied in all their basic needs and partially unsatisfied in all their basic needs at the same time.”

Myth #3: “The cognitive and aesthetic needs should be included in the basic needs pyramid”

Maslow indicated that the need to know and to understand are instrumental in the basic needs hierarchy. However, Compton suggests that these needs are active throughout the hierarchy, based on Maslow’s suggestion that “the quality of the desires to know and to understand would change as a person moves through the basic needs hierarchy.”

Myth #4: “Highly self-actualizing people are focused on their own development and achievement: They are focused on ‘the self’”

Compton shares evidence that Maslow counters this assumption. For example, Maslow frequently describes highly self-actualizing people as egalitarian and having personality qualities that include “deeper and more profound interpersonal relations, tolerance for self and others, a democratic character structure, and a dedication to a vocation that they saw as being a service to others.”

Myth #5: “The self-actualization needs are the top of the needs hierarchy”

Later in his career, Maslow added an additional level to the pyramid that included needs that are, “transpersonal, transhuman, centered in the cosmos rather than in human needs and interests, going beyond humanness, identity, self-actualization, and the like…”

Maslow describes two types of self-actualizing people, the peakers and the nonpeakers, individuals who have peak experiences and those who do not. Peakers, he described, are more likely to perceive sacredness in all things, are more drawn to awe and mystery, yet were described as sadder that non-peakers, due to carrying a ‘cosmic-sadness.’”

Myth #6: “Maslow rejected scientific psychology”

Compton again references Maslow’s own words to reject this false belief:

“I believe mechanistic science (which in psychology takes the form of behaviorism) to be not incorrect but rather too narrow and limited to serve as a general or comprehensive philosophy [of science].”

Compton clarifies that Maslow was critical of the way science was conducted but was not against scientific endeavors in general. Rather, he thought scientists should be more transparent in the way they bring themselves to the process, encouraging more “intimate, even loving, attention to every aspect of the process…more receptivity, more willingness to suspend judgments, more patience, more empathy, and caring.” Compton claims that Maslow embraced science, describing it as “ultimately the organization of, the systematic pursuit of, and the enjoyment of wonder, awe, and mystery.”

Myth #7: “Self-actualization theory is elitist”

While Maslow has identified self-actualization in people of color, women, people with various socioeconomic statuses, and diverse cultures and religions, he did not attend to the potential sociocultural impact of racism, sexism, homophobia, poverty, or xenophobia on a person’s journey toward self-actualization. In Compton’s search to understand this issue, he names various writings by Maslow that support it and others that debunk it. Ultimately, Compton acknowledges the ethnocentrism in self-actualization theory, and that Maslow’s basic theory is grounded in a western perspective privileging a “self-focused, inner directed, autonomous, individual” approach to well-being.

Myth #8: “Maslow chose people he admired for his initial sample. Therefore, self-actualization theory is not value-free and is not scientific”

Compton backs Maslow by making no claim that the science behind self-actualization theory is value-free, but rather encourages explicit ownership of values that guide the scientific process such as the theory, research methodology, as well as the interpretation of results.

Myth #9: “Highly self-actualizing people are happier than other people”

As “happiness” was not so popular a buzzword as it is today, Maslow did not concern himself with it for the most part, and it was not included in the characteristics of highly self-actualized people. Yet, Maslow did make comments that seem to imply people who are highly self-actualizing people are happier. His language, however, focused more on “fulfillment, realization of potentials, authenticity, and enhanced sense of meaning and purpose.”

Compton notes a number of the articles he reviewed are samples from college students, a population experiencing self-actualization disparately from the general public. He also acknowledges the limitations of Maslow’s western framework, warranting further discussion of the uses and misuses of self-actualization theory.

****

Compton, W. C. (2018) Self-actualization myths: What did Maslow really say? Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 00(0). doi: 10.1177/0022167818761929 (Link)

Great article. As a teenager I realised that Maslow defined many of my most accomplished heroes as losers. And so considered him to be deeply up his own pyramid.

Report comment

I understood the biggest myth about Maslow’s concept of self-actualization to be its universality; it is tied to western cultures with eastern cultures seeking more communal aspirations.

Report comment

There’s a lot to be said about self-falsification. A lot of people make their careers out of it. It’s called acting.

There may be a movement toward defense, toward safety, toward being afraid; but over on the other side, there is the growth choice,” Compton writes, quoting Maslow. “To make the growth choice instead of the fear choice a dozen time a day is to move a dozen times a day toward self-actualization.

All Alice had to do to grow was eat some cake.

Self-actualization is either a matter then of climbing this hierarchy, I would imagine, or moving to California, at least, it was, historically. Ditto, self-falsification.

The ascent strikes me as somewhat peculiar. too, from “need”, “having not”, deficiency, all the way up to having “being”, possession, luxuriating. This leads us to another question, what was Maslow’s relationship to the means of production?

I feel sure, in fact, that this pyramid must be situated somewhere pretty high up on the tower of Psycho-Babel.

Report comment

“There may be a movement toward defense, toward safety, toward being afraid; but over on the other side, there is the growth choice,” Compton writes, quoting Maslow. “To make the growth choice instead of the fear choice a dozen time a day is to move a dozen times a day toward self-actualization.”

Trying to make people be afraid, and taking away their rights, has been the goal of our mainstream media, and the psychological and psychiatric industries, for a long time. Those of us who weren’t interested in being afraid or brainwashed with fear by the boob tube after 9/11/2001, we are the ones who the “mental health professionals” attacked and tried to murder.

In other words, those who make the growth choice are the ones who are the threat to the “mental health professionals,” their globalist pedophile masters, and the current statist quo (pun intended).

Report comment

I don’t know that “growth” is the right word. “Change”, on the other hand, pretty much describes it. The opposite of inhibition being exhibition.

“Growth” for “grown” people is something like “healing” for “healthy” people. One sure way to ill health, in such a case, would be to acquire a “healer”.

Report comment

Yes, SE. And the “peak” people are the one’s most apt to get labeled crazy since they see things differently then others, are “too sensitive” and aren’t happy all the time. Sounds “Bipolar 2” to me.

Report comment

And the MIA community would wonder why two of my favorite psychological authors are LS Vygotsky and AR Luria.

Report comment

Like Darwin’s theories, Maslow’s theories have been misused.

When I was 20 years old I was first introduced to “therapy” by my employer. I tried to be polite and said nothing, but I really felt disdain over his engagement in therapy. My reaction was, “Oh my god, no one would waste time in an office like that unless they were too rich and way too self-absorbed.”

Sadly, three years later, I fell for therapy myself. I thought that going to the “poor people’s clinic” would be different. I didn’t want to be elitist, either.

Report comment

I would call these “ivory tower” perspectives. I believe being human and how we evolve in our process of life–including how we choose when to be social or not–is purely an individual matter. We all have our own unique and creative ways of doing life.

Some people harmonize with each other and some do not. Some can co-create together like gangbusters, while others are continuously clashing and nothing really gets accomplished, aside from chronic unresolvable conflict and constant frustration. Relationship to others is a continuum, I believe, and can be fluid or rigid, depending on many things in our lives, like what our beliefs are about relationships, and what we carry in our hearts. That would be outside any box, true to who we really are rather than being a measure of someone else’s standard.

Building boxes–aka “models”–in which people are supposed to fit will always lead to elitism, classism, inequality, prejudice, stigma, and marginalization. That is our current paradigm, over and over again, passed down from generation to generation, from revolution to revolution. No one model fits all, and I don’t believe it ever will. I would consider that to be the essence of “de-humanizing.”

Report comment