“If every gratified craving from heroin to designer handbags is a symptom of ‘addiction,’ then the term explains everything and nothing.”

— Amanda Heller (Boston Globe, 11/02/08)

In his 2010 book, Unhinged: The Trouble with Psychiatry, Dr. Daniel Carlat1 (pp. 53–54) shares an interview with Robert Spitzer (chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-III taskforce), discussing the rationale used to arrive at what would become the guidelines for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder by all mental health professionals in the United States:

Carlat: How did you decide on five criteria as being your minimum threshold for depression?

Spitzer: It was just consensus. We would ask clinicians and researchers, “How many symptoms do you think patients ought to have before you would give them a diagnosis of depression?”

And we came up with the arbitrary number of five.

Carlat: But why did you choose five and not four? Or why didn’t you choose six?

Spitzer: Because four just seemed like not enough. And six seemed like too much.

For obvious reasons, much of what we think we know about the world comes to us by means of trust. Trust that wherever there exists a gap in our knowledge, and where we do not possess the relevant qualifications to engage with or even understand the relevant science dealing with that subject, there will always be an authority whose views we can trust as the received wisdom of that scientific discipline. This is simply a necessary fact about the world we navigate. With limited amounts of time, and the impossibility of receiving the necessary training required for engagement with every major scientific discipline in existence, we simply have to rely on the expertise of those more qualified than us to supply us with the knowledge we are incapable of producing ourselves.

The problem is that sometimes, as above, we discover how certain decisions that affect the lives of millions of individuals, decisions which also shape our understanding of the world and of a phenomenon like depression, are made on the basis of an arbitrary consensus that doesn’t strike us as particularly scientific. If a professional psychiatrist like Dr. Carlat could be unaware of the way the diagnostic criteria for depression were developed within his own profession, how likely is it that the general public would ever come to know about this either?

To make things worse, this kind of decision-making process is only revealed to us (and members of the discipline itself) two decades after the publication of the DSM-III. Millions of individuals have been diagnosed and treated for a mental illness that, upon closer inspection, was codified into the most influential medical text in all of mental health, on the basis of what seemed to be the appropriate number of symptoms.

And yet, 3 decades and 3 major revisions to the DSM later, the process of how mental disorders become codified is even less transparent than before. Spitzer himself was one of the first psychiatrists to sound the alarm when the DSM-5 was in the process of being drafted. To his shock, those involved in the creation of this new edition were under strict non-disclosure agreements preventing them from discussing anything related to the process of creating the latest DSM. A non-disclosure agreement that is legally binding to this day:

DSM-V participants have been required to sign a confidentiality agreement that prohibits them from divulging any confidential information about the DSM-V revision process. That process is broadly defined as “all work product, unpublished manuscripts and drafts and other prepublication materials, group discussions, internal correspondence, information about the development process and any other written or unwritten information in any form that emanates from or relates to my work with the APA Task Force or Workgroup.”

Remarkably, that agreement extends beyond the time of the publication of DSM-V. Even with the exception that allows the participant to discuss DSM matters if “necessary to fulfill the obligations” of his or her appointment, this agreement forces the participant into the awkward position of having to decide whether providing information about the DSM is part of his job. In those likely frequent situations in which providing information is not deemed part of the job, this hardly results in a transparent DSM-V. (Spitzer, Psychiatric Times)

This brief background on the general secrecy behind the decision-making process of how mental illnesses come to be formally recognized is important to keep in mind when we consider the latest condition to be accepted into the canon of mental health: Gaming Disorder.

Defining the Condition

According to the World Health Organization, Gaming Disorder is:

A pattern of gaming behavior (“digital-gaming” or “video-gaming”) characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences.

For gaming disorder to be diagnosed, the behaviour pattern must be of sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and would normally have been evident for at least 12 months.2

What makes this debate so interesting is that we can see, in real-time, the intellectual process by which a new type of illness becomes formally recognized by the relevant qualified authorities of the mental health profession. Unlike the often secretive DSM process, the International Classification of Diseases (the international standard for the identification of all diseases and health conditions) is a document with a far more open process that provides fascinating insight into how decisions about classifications are made, and why.

Ever since Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, historians, sociologists, and philosophers of science have produced a voluminous literature detailing how scientific knowledge is produced and disseminated throughout culture. By providing a sketch of what this process looks like in the context of mental health, we will have a glimpse into how newly created (or “discovered,” depends on how you think about these things) disease entities gradually become entrenched into the public consciousness.

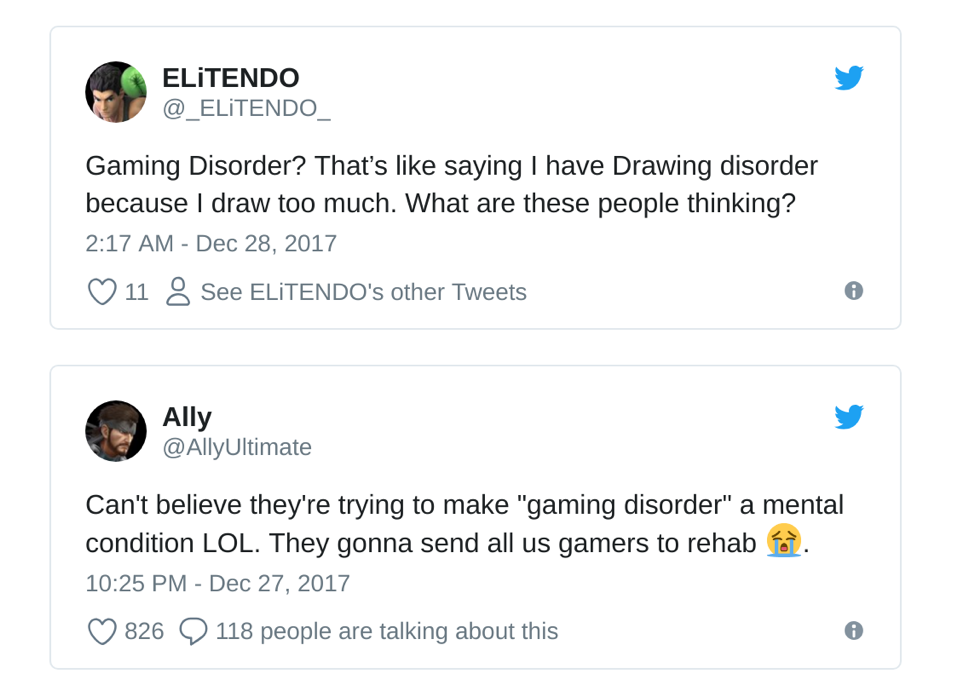

As defined, the idea of a Gaming Disorder is not remotely as absurd as the social media backlash portrays it to be:

But as the ICD makes clear:

Studies suggest that gaming disorder affects only a small proportion of people who engage in digital- or video-gaming activities.

The key to understanding who qualifies for the diagnosis and who doesn’t is the presence of significant impairment:

For gaming disorder to be diagnosed, the behaviour pattern must be of sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and would normally have been evident for at least 12 months.

Most gamers, even hardcore ones, do not suffer from significant impairment in these major life areas to such an extent as to meet the criteria for having a gaming disorder. The ICD makes clear that what it’s concerned with are specific types of consequences characteristic of gaming addiction:

People who partake in gaming should be alert to the amount of time they spend on gaming activities, particularly when it is to the exclusion of other daily activities, as well as to any changes in their physical or psychological health and social functioning that could be attributed to their pattern of gaming behaviour.

If most of us are comfortable with the idea that something like gambling addiction is a real phenomenon worthy of treatment, then it’s not a massive stretch to think video games can lead to similarly addictive behavior, especially considering the fact that many videog ames feature reward loops that possess many structural and psychological similarities with gambling.3

So, the idea of a gaming disorder is not absurd, and certainly not a cause for alarm as loud and vociferous as the social media one has played it up to be. There is, however, good cause for skepticism and caution about enshrining Gaming Disorder into the ever-expanding list of mental health conditions.

The Problem of “Significant Impairment”

The ICD’s criteria for Gaming Disorder makes it clear that you may only be diagnosed with the condition if your gaming habits cause “significant impairment” in major life areas. In fact, all psychiatric disorders include this criterion. In the United States, the DSM also requires that this criterion is met before making any diagnosis, though the term used in the DSM is something called “clinically significant distress.” The problem they both face is vagueness.

All mental illnesses, by the definition agreed upon within the profession, must cause at least some harm to an individual. If there is no harm, there is no illness. This is why, for instance, despite Donald Trump possessing all the symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder, he does not meet the full criteria for a diagnosis. Because despite his narcissism, his condition does not cause him any clinically significant distress. Dr. Allen Frances, a towering figure in psychiatry who himself chaired the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR, has publicly argued as much against his fellow mental health professionals who think we should diagnose Trump with NPD. He writes that those wanting to diagnose the president:

…ignore the further requirement that is crucial in defining all mental disorders — the behaviors also must cause clinically significant distress or impairment.

Trump is clearly a man singularly without distress and his behaviors consistently reap him fame, fortune, women, and now political power. He has been generously rewarded, not at all impaired by it.4

A mental illness does not count as a genuine illness unless it impairs or causes clinically significant distress to a person. Harm of some sort must exist for something to count as an illness. This value judgment is built-in to the very idea of illness. Without harm, there is nothing to diagnose. And because the idea of what is harmful is a value judgment which is often either unclear or subject to widespread disagreement within and between cultures, the entire process of diagnosing someone is never a wholly scientific one. At some point, the mental health professional must always make a decision that necessarily includes a value judgment about whether harm exists in this particular client’s life because of their symptoms. Most of the time, the answer is quite clear and uncontroversial.

For instance, if a client is unable to maintain steady employment due to a condition like insomnia, which in turn causes friction at home leading to an unsuccessful marriage, and in desperation the client seeks help from a mental health professional, then the presence of real harm because of the condition is rather clear.

Where theory and practice come into conflict are cases where the very idea of what constitutes a “harm” aren’t nearly so clear. In these cases, the DSM, and science in general, offer little to no guidance. As Gary Greenberg writes:

Psychiatrists have gotten better at agreeing on which scattered particulars they will gather under a single disease label, but they haven’t gotten any closer to determining whether those labels carve nature at its joints, or even how to answer that question. They have yet to figure out just exactly what a mental illness is, or how to decide if a particular kind of suffering qualifies.

The DSM instructs users to determine not only that a patient has the symptoms listed in the book (or, as psychiatrists like to put it, that they meet the criteria), but that the symptoms are “clinically significant.” But the book doesn’t define that term, and most psychiatrists have decided to stop fighting about it in favor of an I-know-it-when-I-see-it definition (or saying that the mere fact that someone makes an appointment is evidence of clinical significance).

Instead, they argue over which mental illnesses should be admitted to the DSM and which symptoms define them, as if reconfiguring the map will somehow answer the question of whether the territory is theirs to carve up.5 (p. 11)

In a different cultural climate, one where we’re not so concerned about strict boundary policing within academia and squabbling over what questions belong to which field and which are off-limits, we might all agree without much controversy that the reason psychiatrists have such a difficult time with defining “clinically significant distress” is because it’s ultimately a philosophical question. To answer that, you must first provide a comprehensive account of what “health” and “illness” mean. And to answer those, we need a comprehensive philosophical account of what behaviors really, ultimately, lead to human flourishing. And on the flip-side, what kinds of things are ultimately truly harmful for us.

I know many readers may think these questions aren’t that difficult. No doubt we can all immediately name things that are obviously good and obviously bad for us, and in doing so we’re tempted to believe that the question of well-being shouldn’t be too hard to resolve. This would be a mistake. Explaining why would require a detour into the history of ethical philosophy. For that, I can only point elsewhere and hope the reader can see that answers to this are too important and require too much nuance to be responsibly condensed into a digestible soundbite.

What the DSM and ICD do is ignore, or at least sidestep, the fundamental questions of what a good life looks like, and simply assume, out of practical necessity, the answers to these questions as settled. As Warren Kinghorn (2015) notes, in doing so, the DSM:

…functions in our culture as a kind of moral document that, by designating certain forms of experience and behavior as disorder, displays personal and cultural judgments about the shape of a life well lived.

In defining normative parameters outside of which medical intervention and medical technology are ‘clinically indicated’, the DSM demarcates certain outer limits of the good life and, therefore, displays certain conceptions about how we ought to live, if one is influenced by prevailing cultural judgments.6 (p.66)

A Social Construction by Any Other Name

Since neither the DSM nor the ICD provide a standard as to what kinds of things count as “significant impairments,” it is always up to the clinician to make a determination based on their personal assessment of the situation. And it’s here where a scientific enterprise becomes much more of an art. Suppose a college student is trying to balance a full-time course load while working part-time on the side. The combined stress of balancing school, work, and somehow also maintaining a healthy social life becomes so stressful that this student begins to play games regularly as a coping mechanism. The amount of gaming hours played leads to the student missing several assignments and doing poorly on tests, and as a consequence their final GPA suffers, going from a 4.0 to a 3.0. Is this an addiction? Does this count as significant distress? There’s no principled way to answer this question. It’s up to the clinician.

What if a clinician decides that, while unfortunate, the consequences of the student’s gaming do not quite reach such a level as to be considered significant distress?

Suppose the clinician also sees another client with an identical life circumstance, but instead of the GPA lowering from a 4.0 to a 3.0, it goes down to a 2.5 GPA. This leads the student to lose their scholarship, eventually having to leave the university due to an inability to pay. Is that enough to meet the diagnostic criteria? Again. There is no standard.

In every case the clinician has to make a judgment call that is not at all a scientific one. It’s a judgment call that will be influenced by all sorts of external non-scientific factors such as personal beliefs, values, judgments, moods, personality, and a million other possible variables.

Most of the time this is fine. In ideal clinical settings, a clinician will work closely with a client, building a therapeutic relationship that allows a decision about the existence of significant impairment to be made through a mutual convergence of opinion. Most of the time we just know whether an activity we engage in frequently harms us in other areas of our lives, and there’s no need for philosophy to come in and challenge something so obvious.

The problem is what this kind of judgment call says about the scientific status of calling something an illness. Think back to the cases above of the two college students with identical gaming habits. What does it mean to say that one of them has a mental illness and the other doesn’t, when the only difference between the two is that one lost his scholarship while the other only slightly suffered a drop in GPA? Can the existence of a medical illness really boil down to something like losing a scholarship? Doesn’t this imply that the existence of an illness depends on an external social factor, such as the way that society responds to your situation?

Or phrased in a slightly different way, it seems like the social consequence of losing a scholarship is the crucial determining factor of whether you receive the medical diagnosis of Gaming Disorder. It is precisely this that sociologists and philosophers of science mean when they say something is socially constructed. Part of what we mean when we say something is socially constructed is that the existence of an entity, in this case a specific medical condition, partly or wholly depends on certain social attitudes, beliefs, or reactions towards that entity. In this particular case, a mental illness exists if and only if it causes certain types of distress that we get to define.

Coping and Addiction

“It is impossible to understand addiction without asking what relief the addict finds, or hopes to find, in the drug or the addictive behaviour.”

― Gabor Maté, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction

What is the distinction between someone with a gaming disorder and someone who plays excessive amounts of video games as a coping mechanism for life related problems?7 From an outside perspective, two clients may seem to be engaging in identical behavior, though the internal reasons that explain that behavior may be totally different. Many of us, myself included, play games as a means to deal with work and life related stress. The hours we put into games are often difficult to justify even to ourselves, let alone to others. These are hours spent at the expense of spending time with loved ones, building new social relationships, and often comes at the cost of neglecting work or general life-related responsibilities.

Because of life stressors, we engage in behaviors like excessive gaming that themselves create new problems in major life areas like relationships. It’s all too common to see something like:

Stress → Games → Damaged Relationships → Increased Stress → Doubling Down on Unhealthy Coping Behaviors

And yet, there do not exist any good screening tools to distinguish these cases from one another. That’s because there is still no widespread agreement as to whether or not these are two separate phenomena.

The problem is in fact much bigger than this. There is no widespread agreement about any of the major details on gaming disorder: How is it defined? How widespread is the problem? What kinds of treatment are useful? What exactly are the symptoms and cut-off points? We don’t know.

And this is acknowledged as such even by those defending its inclusion into the ICD and DSM:

With regard to the prevalence of the Gaming Disorder, the authors of the debate paper are absolutely right: we have no idea about the exact magnitude of the problem, because studies were conducted in different populations, and with different disorder definitions and different assessment instruments and procedures. As a consequence, in general population studies, the prevalence of “gaming problems” ranges between a low of 0.5% and a high of 10% (e.g., Petry, Rehbein, Ko, & O’Brien, 2015). Moreover, very little is known about the long-term course of “gaming problems” and the probability of spontaneous recovery.

But what about the lack of international and interdisciplinary consensus about the definition of a Gaming Disorder? Indeed, there is no general consensus on the symptoms and cut-off points that are most suitable for the definition of the disorder; a point that is explicitly recognized by the authors of the DSM-5.8

The Invention of an Illness

If there is no widespread agreement about any of the major details,9 why do we include a condition like Gaming Disorder in a book alongside viruses like Ebola, Influenza, Dengue, Parkinson’s, HIV, Cancer, and countless other far more empirically validated conditions?

The answer is as boring as it is illustrative of how science works in the real world: technical trivialities coupled with societal concerns. Notice, for instance, how in a published paper defending the inclusion of Gaming Disorder into the ICD, a major reason offered supporting the decision is that the book doesn’t have a category specific to tentative disorders in need of further research:

Unfortunately, ICD-11 does not have a special category of tentative disorders and the decision has to be made to either not include a certain problem as a diagnostic category or to present it as a definitive disorder with a fixed set of criteria. This is unfortunate, but that seems to be the reality that WHO has to deal with in finding the most optimal solution.

This is the trivial technicality explanation. A new disease entity is formally recognized on the basis that the book where such diseases are categorized does not have a section for up-and-coming diseases that may or may not eventually make the cut. So it is deemed better to over-include than to adopt a conservative stance towards the inclusion of new diagnoses.

The social reason for its inclusion is financial. People who allegedly have the condition want treatment. But the only way for insurance to cover it is if it’s for a condition formally recognized in the ICD and DSM. We should therefore include it so that insurance companies will help clients pay for such treatment:

In many countries, treatment is only reimbursed when it concerns an officially recognized disorder, that is, treatment is only reimbursed for disorders mentioned in the ICD or DSM classification. Therefore, it is important that Gaming Disorder will be included in ICD-11 and that Internet Gaming Disorder has already been recognized as a tentative diagnosis in DSM-5.

And there it is. A mental disorder is born.

One Last Thing

If everything talked about until this point isn’t enough to make you pause, there is one last caveat to the ICD’s diagnostic criteria worth noting. I’ll let the reader draw their own conclusion about its possible implications in a clinical setting:

The pattern of gaming behaviour may be continuous or episodic and recurrent. The gaming behaviour and other features are normally evident over a period of at least 12 months in order for a diagnosis to be assigned, although the required duration may be shortened if all diagnostic requirements are met and symptoms are severe.

The diagnosis of gaming disorder is way up there with the diagnosis of Rock and Roll disorder.

The DSM has let in behavioral addictions. I don’t need to tell you how absurd that is, do I, but now, with sex addiction, the likes of Harvey Weinstein have something to consider as a legal defense. That’s what he was trying to say, wasn’t it, with his, “I have a sickness.”

Hoarding disorder, too. “If what you hoarded were gold nuggets, or fine art say, we’d have no problem with it, but all this unnecessary junk.” In the eye of the beholder, of course. Memories….

What next? “Freedom of choice disorder?”

Report comment

Freedom of choice would be the last thing they make into a disorder. It would break the spell.

Report comment

If you spend 10 hours a day gaming, it has become a bad habit to be broken. Not a disease to be cured.

Alcoholism is a disease! Admit it or I can’t sell you the cure.

A friend of mine was an alcoholic. Then he quit drinking. Some folks find AA helpful but others–like Vern–quit without it.

Report comment

Well, when Step 1 is Admit that you are Powerless (or some such, my mother was an AA-er, not I), that does not go over well with trauma survivors- who already feel too powerless. The whole higher power thing doesn’t work great for atheists, either. My mother, btw, did not use AA to get sober. She already was sober when she started going– for her, it was more a religion.

Report comment

Besides atheists not doing well with AA’s model, devout religious folks also tend to “fail” to “work it.” I never could “do” OA.

If you’re into Oprah’s or Joel Osteen’s moral therapeutic deism, AA might be right for you.

Report comment

My name is Lawrence, and I am addicted to writing blogs for Madinamerica.

Report comment

Can you admit that you are powerless over your addiction to blogging? Do you need the help of a Higher Power to help you gain control of your addiction?

Report comment

Again , it is who is in power who gets to define illness. If your loved one is using crack cocaine to excess, or alcohol to excess, and now computer/video games to excess you can hire a doctor to say they are ill. Does the person think they are ill? is part of the equation. What physical evidence of illness do you have? Does the person have an income? Does the person have their teeth? Too fat or too thin? too much sugar and salt in their diet…. whoops I went too far…

Report comment

It is psychological communism, no one cares, because apollonian ego don’t lose nothing which is beyond meat and blood, and the psyche of mentally ill, is non materialistic and meaningless, so they can’t see that humanity is being robbed, because THEY ARE NOT .

Psychological traits are not the money that dissapeard, so no one gives a f.

Those who are being destroyed are those beyond hegemony of mindless normalcy, so no one cares. And those who are, are propably dead or nearly dying OR VOICELESS. And that is why they are today heroes. Because the voice of the normal means nothing to humanity.

The more human traits psychiatry will change into fake illnesses , the more inhuman and demoralized would be those who would called themselves normal.

This is invisible PSYCHOPATIZATION of society.I do not think that the strongest will survive but I am sure that those who survive will do nothing for humanity, they will built technology and the economics. Like good proper working brainless machines – the system main need. And we should remeber that apollonian system need no humans, it just need their work and money.

Psychiatry violence/hate toward human psyche is double edged sword. The were able to convinced people that psyche is evil trash and that the most inhuman ego apollonian traits are the healthiest ones. So society won’t protest, because it is not HUMAN psyche which is being destroyed, it is that INHUMAN PSYCHE OF MENTALLY ILL – slaves. People without identity.

Normal people cant’see a human being in someone who has got diagnosis. And maybe that is because NORMAL are not humans anymore, and only psychological men are.

Look at the movies “X – man”, or “Divergent”about the girl who does not fit into any of the groups (she sees more and she is called INCAPABLE), especially these two movies. Listen to what they are talking about, (after reading Hillman). They are making movies about psyche hegemony and they don’t know it, because psyche knows better, and they, as simple anti psychological apollonians are not aware of the deeper meaning of what they are doing. Listen to the dialogues in Divergent or X man –THEY ARE TALKING ABOUT MENTALLY ILL —–BUT IN HUMAN LANGUAGE.

Apollonian ego can talk about human psyche using proper human language only in sci fi movies, because the scenarios are not written by psychiatrists, but by psyche herself, she found the way out, using apollonians imagination, without their knowledge and without their permission.

Report comment

Very nice, well-composed article that lays out the issues clearly and succinctly. Thank you.

Report comment

You have forgotten the essential. What is the category of people specifically targeted by this diagnosis? Diagnoses always target a certain category of deviants.

This diagnosis is aimed at children. These are children who will be ripped from their homes to be thrown into psychiatric asylums, based on this diagnosis! Many parents are eagerly awaiting this diagnosis. And to any disease its treatment! What will it be this time? Neuroleptics? Or psychostimulants? Soon money to test drugs for this new disease!

Report comment

Gaming disorder? This is ridiculous. This is one of many addictions that induce similar behavior, no matter what the substance or activity. Seeing if there might be certain physiological constants behind such activities could be useful, but having miscellaneous diagnoses for a single activity is worthless.

Report comment

We should all strive to become more like the honey bee. A fully evolved species. The main threat to the honey bee, on the other hand, is us humans.

Report comment

How about an addiction to cooking up new “diagnoses” for psych tomes?

Why 5 instead of 4 or 6? Well…if we used the number 6 we would have fewer diagnoses and therefore less business. But if we used the number 4 people might catch on to how bogus our “medical science” is and it would go the way of leeches and blood letting.

Report comment

Thanks for pointing out how and why the psychiatric industry creates illnesses, as opposed to treating real illnesses.

I agree this is an important point, “The social reason for its inclusion is financial. People who allegedly have the condition want treatment. But the only way for insurance to cover it is if it’s for a condition formally recognized in the ICD and DSM. We should therefore include it so that insurance companies will help clients pay for such treatment.”

Today, the DSM classifies child abuse as a “V Code,” and the “V Codes” are NOT DSM insurance billable disorders. Which means today’s DSM practitioners actually have NO right, whatsoever, to bill ANY insurance companies to EVER to help ANY child abuse victim EVER.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

But today’s “mental health professionals” do claim to be the EXPERTS on helping child abuse victims. Some now even claim child abuse and ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) are the primary cause of their serious DSM disorders.

https://psychcentral.com/news/2006/06/13/child-abuse-can-cause-schizophrenia/18.html

I don’t doubt Dr. John Read was honestly and legitimately trying to make sense of his medical findings that huge percentages of those labeled with the serious DSM disorders, were actually child abuse victims.

Today over 80% of those labeled as “depressed,” “anxious,” “bipolar,” and “schizophrenic,” are actually likely misdiagnosed child abuse victims. Over 90% of those labeled as “borderline,” are actually likely misdiagnosed child abuse victims.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

Likely because, NONE of today’s “mental health professionals” may EVER bill ANY insurance company, for actually helping ANY child abuse victim EVER, without first MISDIAGNOSING them with one of the billable DSM disorders.

And the ADHD drugs and antidepressants are now known, by many, but the “mental health professionals,” to create the “bipolar” symptoms.

https://www.alternet.org/story/146659/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america

And the “bipolar” and “schizophrenia” DSM recommended treatments are known to many, but NOT the DSM believing “mental health professionals,” to create both the negative and positive symptoms of “schizophrenia.” The negative symptoms are created via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome, and the positive symptoms are created via antidepressant and/or antipsychotic induced anticholinergic toxidrome. But these known psychiatric drug induced syndrome are NOT billable DSM disorders.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

The “social reason” for the helping of child abuse victims being EXCLUDED from the DSM, according to an ethical pastor of mine, is due to what he called the “dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” And the desire of today’s sickeningly paternalistic medical and religious industries to want to profiteer off of covering up all rape of woman and children, by the DSM deluded “mental health professionals.” And this is a multibillion dollar industry today.

Perhaps, given the huge percentages of their patients who likely had child abuse symptoms misdiagnosed with their invalid DSM disorders, since helping child abuse victims is NOT a billable DSM disorder. Despite the “mental health” industry’s desire to claim they are the world’s expert’s on child abuse. The “mental health professionals” should make actually helping child abuse victims a billable DSM disorder, prior to making video gaming disorder a billable disorder?

Or maybe we should all confess to the reality that the DSM is BS, a classification system of the iatrogenic illnesses that can be created with the psychiatric drugs, as opposed to real genetic diseases. And the DSM should be flushed down the toilet?

Report comment

we have nothing to worry about….

psychologists will soon be prescribing psych drugs..

then they will be in charge…they will do bio and psy..

then it can be anti-psychiatry and anti-psychology…

Report comment

The psychologists are already prescribing the psych drugs in some states, like Illinois, and four other states.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prescriptive_authority_for_psychologists_movement

It should already be anti-psychiatry and anti-psychology. The psychologists have been functioning as nothing more than feeders to the psychiatrists for decades anyway. And they all believe in the invalid DSM disorders.

Report comment

There are more rogue psychologists than shrinks though. This makes sense. Why waste time and effort on an MD when you can counsel with just an MSW or PhD?

Any therapist working at a community center has to go along with the bio-bio-bio model though.

Report comment

I had some people n my life who were drug addicts and for me, addiction is a thing that I am trying to stay away from as much as I can through my whole life. I know about free rehabs, you can read about them here if you are interested – https://addictionresource.com/drug-rehab/free-rehabs/ and I am sure that any person can overcome the addiction but still, I myself don’t want to be even close to that condition.

Report comment

I knew that gambling addiction is quite common these days but haven’t thought that the same thing is going on with just gaming. But in any way, that’s quite strange for me. I am gambling on https://sg.bet888win.org and no issues with addiction so far. I suppose it’s just a matter of your temper.

Report comment

It’s so ridiculous to see so many attempts to restrict games nowadays. So little evidence. And what’s funnier I heard politicians and “doctors” who are for banning also flash games like this https://snailbob.io/snail-bob-2.html

Report comment