When I first started writing about asylums and mental health, I was a young teacher working in one of the last remaining residential treatment facilities in Massachusetts. I had no formal training in mental health — I had only my teaching certificate and a desperate need for a job — but I compensated by reading everything I could about treatment models and the evolution of mental healthcare. I also did specific research on the history of the program I was working in. Our school was but a small part of a larger behavioral health network that dated back to the early 1870’s. That network had historical ties to Northampton State Hospital to the north, often shuttling patients back and forth for treatment. Northampton was my introduction to Thomas Kirkbride and his asylums.

By the time I started my research into Kirkbrides, Danvers State Hospital was already well on its way to being demolished, but that didn’t stop me from driving the nearly two hours out to the North Shore of Massachusetts to see the remains of the Castle on the Hill. Nathaniel Bradlee’s hospital was and remains one of the best-known examples of Gothic asylum architecture and has become a fixture in modern pop culture.

Writing about Danvers was a rather daunting task. Despite having written about and lectured on the history of asylums for more than a decade I had never tackled the individual history of one particular institution. Though I knew that a great number of people held expansive collections of images and ephemera from Danvers, I wondered first how many would be willing to share their collections publicly, and then would others be willing to share their memories with me?

In writing about such a well-known asylum, I wanted, first and foremost, to strike a balance between the image of the snake pit that was most prevalent towards the end, and the years of history that preceded the breakdown of the state hospital system. When Danvers was first opened it was considered a model in the humanistic treatment of the insane, one to be studied by other hospitals. Most of the wards were open wards, meaning patients were rarely locked in, and the hospital’s main intent was to support patients in getting well and returning to their lives outside the hospital’s walls. Patients were provided private rooms with views of the manicured grounds, were well fed on fresh produce and meat that came from the hospital’s own farm and were given opportunities to work and contribute to the daily workings of the asylum.

Great emphasis was placed on occupational therapy, which in the late 19th and early 20th century consisted of both outdoor and indoor recreation. Baseball games, picnics, and organized exercise were common on the grounds while dances, moving picture shows, and concerts were held indoors. Both men and women worked with their hands weaving baskets, sewing, and making brooms and brushes. Though these tasks may seem rudimentary and demeaning today, they gave patients the opportunity to feel useful and connected in a place that might otherwise foster a great deal of isolation.

Danvers also emphasized connection with families and community. Early on, the hospital employed a social worker who was responsible for following patients after they returned to the community, ensuring that they had gainful employment as well as a place to live that was conducive to continued progress in their treatment. Patients and their families regarded a stay at Danvers as a positive, healing experience.

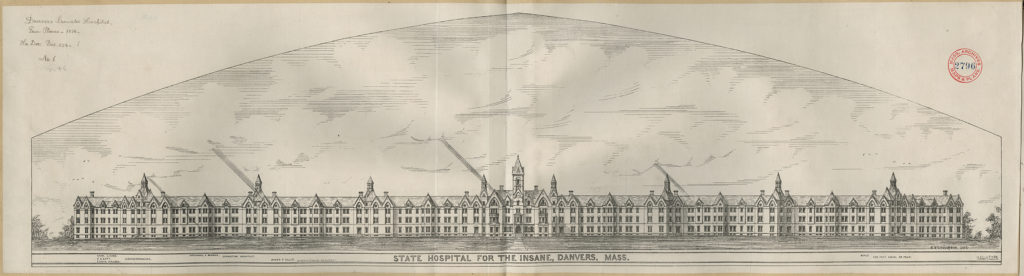

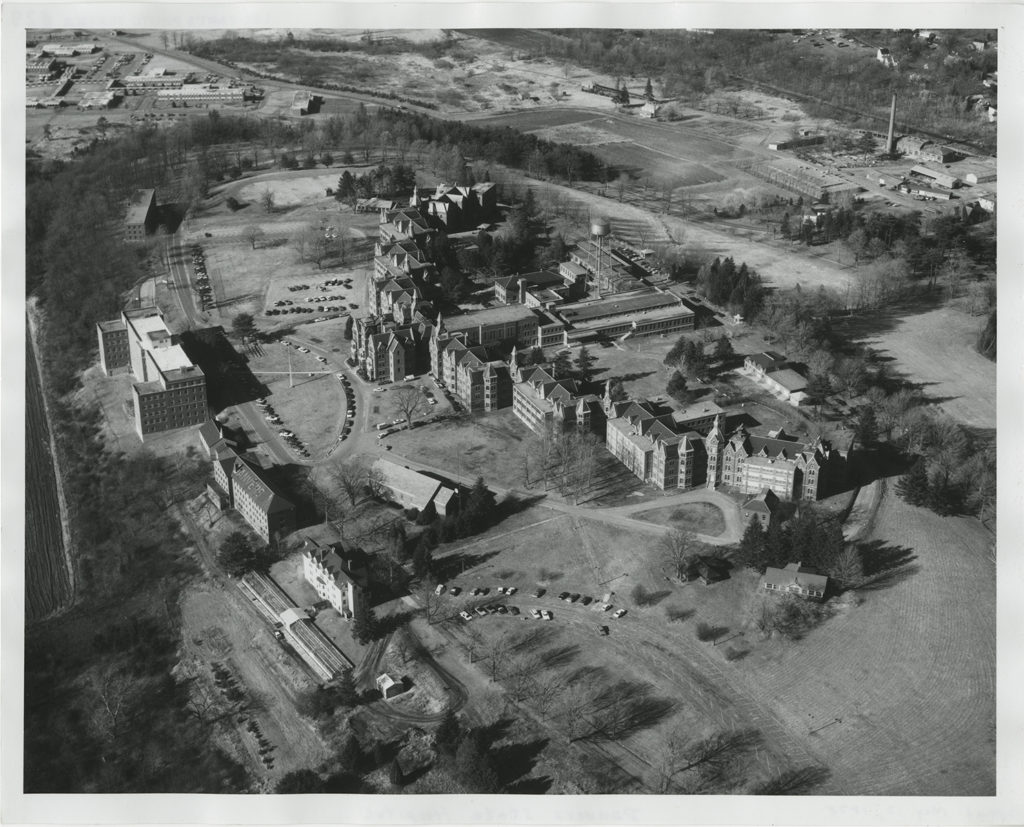

In collecting images for the book, I wanted to showcase first the physical beauty of Danvers State Insane Asylum, and thankfully there exists a rather large archive of early images including glass etchings and original architectural drawings. The sprawling Kirkbride measured in at 313,000 square feet and was nearly 2,000 feet in length. The interior was equally opulent with tin ceilings, decorative plaster walls, and chandeliers. Dahlias, the Victorian symbol for madness, were carved into the mantelpieces and adorned the exterior metal work. Interestingly, the asylum’s first annual report was quick to point out that all the interior walls were rounded at the corners so that patients wouldn’t bump into sharp edges.

Interior images of the hospital were much harder to find. There are a few in existence, mostly in private collections, the others held by the archives at the Peabody Library (not pictured in the book). They are images of nurses caring for patients who are comfortably situated on clean, bright hospital wards, a far cry from what Danvers would eventually become.

For nearly a century, Danvers was a model asylum that hosted visitors from all over the world, including townspeople, family members, and friends. The formal gardens alone attracted roughly 12,000 visitors annually and those visitors often brought gifts for the patients such as books, magazines, and flowers for the wards. Danvers played host to visiting doctors and specialists, set up community outreach clinics, and established a nursing school.

These were the halcyon days of the asylum. In spite of brief mentions of overcrowding in early annual reports, Danvers was able to treat patients in relative comfort and, in most cases, discharge them as recovered. The great shift in mental health treatment came with the invention of psychopharmaceuticals, the early “hypnotics.” Though drugs like chloral hydrate, morphine, and opium had been in use for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the advent of modern antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine) “revolutionized” the care of the “mentally ill.”

With the help of this new breed of drug, hospitals were able to admit and manage a greater number of patients. The population at Danvers peaked at nearly 3,000 in the late 1960’s and into the early 1970’s. Patients were regularly treated using not only psychotropic medications but also electroshock therapy, hydrotherapy, and psychosurgery (also known as the prefrontal lobotomy). Asylum populations began to shift dramatically and hospitals moved away from the centralized model, choosing instead to unitize, working with the various regions to provide as much community support as possible.

Eventually reports began to surface of abuse and neglect within the hospital’s walls. Suspicious deaths, patient escapes, and violent assaults were all recorded (though not in as great a number as some might expect). By the late 1980’s the hospital’s main operations were moved from the Kirkbride to the more modern Bonner Building across the way. By the time the remaining hospital buildings were closed down for good in 1992, the buildings had begun to decay and by and large the public was happy that the state hospital was no more. The doors to Bradlee’s architectural masterpiece were locked and the Castle on the Hill was abandoned. The remaining and lasting impression of Danvers State Hospital was that it was a snake pit where the mentally ill went to languish and often die.

Soon after its closure, Danvers State Hospital would become the haunted house on the hill where kids dared one another to sneak in. It fell victim to vandals and arsonists, graffiti artists and scrappers. For many, it was an eyesore that couldn’t be demolished soon enough. For others, it was one of the few remaining bastions of an era of hope and enlightenment. Prior to the creation of the state hospital system, those deemed mentally ill were cared for at home, isolated from their community and feared by those around them. As families began to work outside the home and were not able to care for the mentally ill any longer, the responsibility fell to the states to find reasonable accommodations. The first institutions to care for the mentally ill were poorhouses and prisons. As wave after wave of immigrants reached the shores of the United States, the poorhouses overflowed and the number of insane poor skyrocketed. Many who caused problems in the poorhouses were transferred to jails or prisons but that was still nothing more than a temporary solution.

The first public asylum in the United States was built in Worcester in 1833 after noted social reformer Dorothea Dix discovered the mad chained in unheated prison cells alongside alcoholics and murderers. She was appalled by the conditions in which these individuals were kept and lobbied the state of Massachusetts for more humane treatment of the mentally ill. The American asylum system was born. In spite of its eventual decline, the system of care for the mentally ill in the United States began with the best of intentions: to care for the weakest among us in a thoughtful and humane way. Eventually, changes in legislation, the advent of the modern healthcare system, and a shift in human rights would bring the entire system to its knees in favor of community treatment.

As a photographer and historian, Danvers captured something in me that I often have a difficult time explaining. The architecture — and the knowledge that it played a part in the overall treatment model — sets the Kirkbride asylum apart from any other historical structure. As a writer and educator, I find that Danvers is an ideal vehicle for keeping conversation flowing about the treatment of mental illness as the specter of the asylum touches such a varied group of individuals, from former staff and patients to urban explorers and ghost hunters. Danvers lives on in a very real way, and not just because the façade still stands. It bears a lasting legacy that I hope is captured in the book.

First, having lived in Virginia, not Massachusetts, I have to question the following…

“The first public asylum in the United States was built in Worcester in 1833 after noted social reformer Dorothea Dix discovered the mad chained in unheated prison cells alongside alcoholics and murderers.”

In colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, there was, before any of the other public asylums arose, the first public asylum.

Eastern State Hospital has the honor of being the first public facility in the United States constructed solely for the care and treatment of the mentally ill. In the summer of 1770, Colonial legislators met in Williamsburg, the capital of the Virginia colony, and passed a bill authorizing the construction of a hospital for this purpose. The building was erected on an eight-acre site near the College of William and Mary, and the first patients were admitted on October 12, 1773.

http://www.esh.dbhds.virginia.gov/History.html

In 1841, the name of the public hospital was changed from The Public Hospital For Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds to Eastern Lunatic Asylum, carrying with it the connotations of a sanctuary for the mentally ill.

http://www.asylumprojects.org/index.php/Eastern_State_Hospital

I suppose we could be mincing words in a debate over the difference between “hospital” and “asylum”, a term perhaps more amenable to “moral management”, but that is that.

Auschwitz lives on as a museum, too. Unfortunately, America has been less friendly with its human refuse disposal bins. Yes, I know it wasn’t ALL so dismal, but sometimes the dim interior light becomes a weak mimic of the sun. Kirkbride facilities were notorious for their “backwards”, a term we owe to the arrangement of the buildings, Also, as with other asylums, for their concrete grave stumps showing only numbers on them representing human lives. I’d call that a lot of shame to stomach, even if you’re dealing with the dawn of such facilities, and the beneficence they were supposed to be bestowing.

Western State Hospital in Staunton, Virginia, my old alumnus, (5th public asylum in the country), undergoing it’s third incarnation (move and rebuilding), was not that long ago visited by a french film crew, and they were calling it a model hospital for it’s ankle bracelet monitoring devices and other restrictive treatment innovations, Quite some progress, huh?

Report comment

Excuse me, I meant Western State Hospital was my old Alma Mata, of which I was Alumni. It also BTW predated Worcester when it comes to the admission of patients, going back to 1828.

My guess is that the easiest explanation for this kind of fault of omission goes back to the 1860s, a time when Eastern State Asylum found itself occupied by the Union Army.

Report comment

I find this article breathtakingly naive.

There are no ‘good old days’. Manicured gardens, gothic architecture, some unlocked wards, social workers and occupational therapy have provided the backdrop to untold torture and abuse.

It is not just the modernish drugs and bio-medical model that have caused psychiatric abuse.

Report comment

Sorry, but I think Katherine’s article is great. And “out” there was a period of the “good ol days” at Danvers. We’re going back to the days of Doretha Dix and Thomas Kirkbride. When Danvers was first built, it wasn’t instantly the “snake pit” that’s burned in everyone’s memory today. George Kline, Charles Page and other superintendents were some most honorable and respected men in the medical field at the time.

“In Massachusetts Dr. C.W. Page, for many years superintendent of the Danvers State Hospital gave much careful attention to the matter the developed a public sentiment which has found expression within the past two years an act passed by the State Legislature forbidding patient restraint” This is from the Institutional Care of the Insane in the US and Canada 1916.

As the times and society changed so did the State Lunatic Hospital at Danvers (the original name) later changed to Danvers State Hospital.

Report comment

Alright. You should see some of the bozos who are among “the most honorable and respected men in the medical field” today. It would make one blush with shame.

Francis Stribling of Western Virginia State Lunatic Asylum was friendly with Dorothea Dix, too. She, after all, is said to have been the inspiration behind the building of some like 40 such institutions. I, on the other hand, don’t care much for either of them.

There weren’t THAT many institutions throughout the 18th century yet, but with the 19th century, chiefly on account of the moral reform movement, the numbers of patients were multiplied many times over. Just look at the great size of those Kirkbride monstrosities. Early in the 20th century, and riding on the tail-end of moral management, you have the mental hygiene/health movement. a movement that is still with us today in it’s efforts to medicalize every aspect of everyday life. Back up a few centuries. Maybe it was NOT such a good idea to lock up so many people?

Ending restraints is a big problem for reformism. Two hundred since that began, with the demand to end restraints, and they still haven’t managed to do so. Why is that? I think it has something to do with the matter of not being serious about the matter in the first place. When you’ve got a captive population, if you haven’t got shackles, you’ve still got solitary confinement. Take off the restraints, and you’ve still got a prison inmate. Okay. When do we get around to talking about liberating all of the prisoner/patient/consumers. Seriously!

I’m not against discussing history, I just want to stress that there is another side to it. Another side that you might miss altogether if you set your sights on doing so.

Report comment

“I’m not against discussing history, I just want to stress that there is another side to it. Another side that you might miss altogether if you set your sights on doing so.”

Yeah, Dorothea Dix was useless and did absolutely nothing to help the illness and was a total whore from what I read.

Report comment

Oh, she did a lot to help the “disease” alright. She campaigned for more and more asylums. She thereby got more and more people locked up who could, by a slight stretch of the imagination coupled with a twist of phrase, be considered “afflicted”. and labeled “lunatic”. As for the “whoring”, I have absolutely no idea where her private life was at.

Report comment

By way of explanation…

“Patient Critiques of the Asylum

Despite numerous positive reports on asylum conditions, many citizens suspected that the new institutions hid terrible abuses behind their walls. First hand accounts published by disgruntled former patients fueled rumors of inhumane practices. Usually committed against their wishes, many patients did not believe they were insane and resented their treatment by relatives and physicians”…

“Records left by patients describing their asylum experiences vary from letters expressing appreciation for the restoration of their sanity to bitter lawsuits against hospital and family. The complaints often centered around wrongful confinement: to commit a relative in the mid-nineteenth century families needed only to obtain a certificate from one physician (in some states, two) testifying that the individual was insane. Patient advocates, such as Haskell, whose family got their dentist to sign his certificate of insanity, descried the ease with which families could dispose of unwanted kin and take their property.”

from Madness In America: Cultural And Medical Perceptions Of Mental Illness Before 1914. Lynn Gamwell and Nancy Tomes (1995), pg. 62

Report comment

Like I said, Katherine Anderson’s story is great.

Report comment

I’ve spent years studying the history of public mental health systems in the US, and there were no “good old days.” The folks like Dix who argued for creating bucolic refuges instead of the admittedly vile county poorhouses that often locked up people deemed mad in the 19th century sold the public a bill of goods. These mid-late 19th century “asylums” were horrid places of often life-long confinement in inhumane conditions.

Report comment

Thank-you, Katherine, so very much for this article, and the years of work and dedication which it represents.

Now, of course you know I have to pick a few nits. I’m an MiA regular, so maybe my sensitive and hyper-critical nature is genetic. Heck, maybe it’ll be in the DSM-6. Early in the article, you use the term “mentally ill”, and “insane”, but without the quotation marks. Later, you use “mentally ill” WITH quotation marks. Personally, I think you should only use “so-called “mentally ill””, with quotation marks around “mentally ill”.

My point is, that for all the change in knowledge, understanding, and culture, we still don’t really know what we’re talking about here. We can’t agree on what words to use to describe “it”. Whatever “it” is. But as the early years of Danvers show, we actually did a MUCH better job helping hurting and scared and confused persons 100 years ago, than we do now! Psychiatry and psych drugs have been steps backwards, not the “progress” the psychs would claim.

And it’s interesting to note your description of handcraft occupations as “demeaning”. That’s bunk, and it’s not flattering that you think that way. Would it be better that persons sit in drug-induced stupors all day?

We’ve seen that so-called “sheltered workshops” for so-called “retarded” persons have been phased out, as “reformers”, and “progressives” THINK they know better than common sense. So-called “community treatment” of the so-called “mentally ill” has been an abysmal failure, but it isn’t because residential facilities were too big.

I hope you spend many hours here at MiA, and learn from those of us who have spent some time at places such as Danvers. You’ve done a valuable service by keeping a historical window open into our collective past. So-called “mental illnesses” are better seen as “STD’s”. They are “socially-transmitted disorders”.

Thanks again.

Report comment

I’m curious now. Is there a better written article or documentary on Danvers? (In this site or some other site?)

I would love to read more about the actual economics of how a place runs especially going forward when such facilities need to built or maintained or expanded.

Report comment

Bradford-

Thanks for your comment. If you look at what I wrote I actually said those activities MAY seem demeaning today. When the asylum farms and patient jobs were phased out it was because “they” (whoever they were) said that handwork was demeaning to the patients, that “patient labor” was a violation of human rights. However, I argue strongly that patients gained a sense of accomplishment when occupational therapy was used as part of their treatment. For the first century of Danvers’ existence they relied primarily on physical cures like OT, hydrotherapy, and others. Doctors firmly believed all “mental illnesses” could be cured much like a physical illness, a concept we’ve strayed away from over the years.

Report comment

Of all the important and salient issues here, why on earth would basket-weaving strike anyone as especially offensive and belittling?

I used to attend the seminars of our local philosophical luminaries (I’m not going to pin it down more than that description.)

They would often debate what they saw as ‘the’ issues in psychiatry. It always took my breath away that they could pick out minor matters in relation to the big picture, and in doing so, deftly skirt the elephants in the room, and proceed to argue those minutiae to death. Talk about trivial pursuits.

Report comment

Basket weaving has become a mentalist stereotype, like eating watermelon has become a racist stereotype. It doesn’t have anything to do with the activity itself.

Report comment

Katherine,

I went too thin, when I was buttering on the flattery. You weren’t the target of my criticisms; – you just happened to be walking in front of the target when I fired my latest salvo! Large, State-run institutions have been snake pits and hell-holes, yes, but I think there are larger political, social and economic forces responsible for that. The earlier photos, and your description of early days at Danvers show that Danvers started out with good intentions, and was probably a pretty nice place to be, back when. One big problem with psych drugs, is that they are used as “chemical restraints”, and “chemical straitjackets”, which negates any therapeutic effects they might otherwise have, and makes any kind of actual “therapy” much less effective, and likely. I’m a HUGE history fan, and articles like yours are some of my favorites!

Report comment

We can’t agree on what words to use to describe “it”. Whatever “it” is.

You put your finger on it — this is the key to whatever “dilemma” people think exists about what causes “it” or what to call “it” if “it” isn’t “mental illness”:

THERE IS NO “IT”! There are only idiosyncratic blends of thought, belief, experience, feeling and behavior which cannot be categorized despite imagined or projected (and superficial) similarities between different people’s “presentation,” as we are after all the same species.

The above should not be confused with Bill Clinton speculating on what the connotation of “is” is.

Report comment

Very well said!

Report comment

Can’t understand why anyone thought an article like this would be a good idea, other than maybe to “stir debate” — but even debating the pros & cons of one concentration camp vs. another is offensive.

Report comment

It’s offensive but it can be realistic too.

If you know one concentration camp has a better way of being run versus another concentration camp – you pick up clues on how to actually build a better facility. That can’t be discounted.

Is it going to lead up to debates? Maybe but life is not don’t talk about my hell – let’s build heaven.

Yeah, where was heaven for Franco Basaglia and the people that worked in tandem with him? There was none so understanding the specifics of how these things are told are necessary because it stirs awareness. Maybe an extremely low amount of awareness for people who know about the place but then what about for those who don’t?

The bad idea behind the article is that it’s one article on a blog. It doesn’t teach or show anything at all. It’s just a story.

But to say why the existence of any kind of article that’s potential information looks like it can’t be a good idea? That’s calling for censoring of history.

Report comment

I appreciate this point of view. When I was asked to write this post it was meant to explain what it was like to write about a place like Danvers or any other state hospital. It’s a part of history many people are loathe to talk about openly and books like these are meant to spark debate. Why were these hospitals successful for small windows of time? Where did they go so horribly wrong? If one hospital is successful and 20 are not, where do we start to learn from what’s wrong while preserving what’s right? It’s a never ending conversation when you’re caring for human beings.

Report comment

Well to an extent it’s only a never ending conversation when no one actually wants to make things work by creating an alternative from the lessons gathered from these books you’ve published. (and may publish in the future)

This never ending conversation does not apply to you cause every conversation restarts every time someone buys or reviews your books and someone else buys them again. I’ve just checked your Amazon.com profile but keep in mind there’s also a big difference between knowing the story behind “Danvers State Hospital” (so that people especially knee jerk commentating people can at least get as close to a proper picture even if they just skimmed the text)

…and “telling the story behind places like Danvers or any other state hospital.”

Which may spark debate but may also spark accusations of incomplete information towards the messenger so much so that many won’t even be able to view the message as something about Danvers but about a grand collection of vague state hospitals.

This is my interpretation of why oldhead appears to not appreciate your contributions to society yet. (but keep in mind, my interpretation will instantly change when this person or someone close to this person can show evidence that my view is misinformed on that end)

It’s the catch 22 with narratives in general. Just as you can contribute to society by releasing this books, you also have to consider why the critics of your article or book react negatively to this while the audience is not large yet.

I’m sure you know this more than I do since you’ve actually published a book but I have to insist on you not being stuck on the sparking the debate thing.

You have to get better at delivering the message even when someone just asks you to write something. You’re a public figure and we need you to go above and beyond sparking a debate on these specific locations and time periods.

Not just in terms of acquiring more data or publishing more books but in actually being better at sharing these stories in such a way that unites us rather than makes us victims feel like you are obfuscating the truth because it is in that process that you will get more buyers, build up more credibility among reviewers but ultimately help us many who are overlooked by society to have resources that can help people care about us and just like those past time periods of Danvers – it can seem never ending but the conversation ends when a new conversation begins and it only begins once the story of something’s decline changes into a story of how something actually declined and why that should never happen again in our time.

Report comment

So which was better in your view, Auschwitz or Buchenwald? How could concentration camps in general be improved based on experience?

Report comment

@oldhead

I would say Buchenwald at a quick glance.

Certainly a case can be made for Auschwitz being more commercially viable which means a non-Government Backed Soteria House closer to Loren Mosher’s model could potentially last longer if we learn more things about how it was able to expand on a more evil landscape but life isn’t about sustaining something and turning it into a greater commercial success sometimes and Buchenwald is also a successful concentration camp for its time too.

Plus it’s arguably able to host a more diverse group.

Sure both concentration camps are still concentration camps and not asylums but then the asylum in Gorizia that Franco Basaglia got sent to was no less than a concentration camp in name either which is why he hated it:

“He never grew to love Gorizia. His small group of like-minded colleagues kept to themselves. When the town really got to him, he would put a record player on his top floor balcony and blast out the antiwar song Gorizia, ti sei maladetta (Gorizia you are damned) to the high street below.”

Source: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/05/asylum-franco-basaglia-psychiatry-mental-health

So if we look at both camps’ qualities and the potential for a Basaglia to make a temporary base on it before it crashes down, Buchenwald had closer criterias for any movement that wants to bring down psychiatry because it almost matches Gorizia in terms of how it was kept.

For ex.

Buchenwald was run by almost two people:

Buchenwald’s first commandant was Karl-Otto Koch, who ran the camp from 1937 to July 1941. His second wife, Ilse Koch, became notorious as Die Hexe von Buchenwald (“the witch of Buchenwald”) for her cruelty and brutality.

Gorizia was run by Franco and his wife.

Obviously there are other staff among many other factors to consider but Buchenwald had elements that would make it easier to rescue the people inside. It also had many elements within it that allow for diverse people to share their views. (Obviously as prisoners and not as scholars but this diversity was critical to influence Viktor Frankl to see the light at the end of the tunnel too in his days of hopelessness which these prisoners not only require but absolutely need otherwise Basaglia’s philosophy wouldn’t have worked)

” It was important to build up a relationship with the inmates and to listen to their stories. In one case, Basaglia and his first collaborator inside Gorizia, Antonio Slavich, spent four days and nights listening to the traumatic life story of a patient called Mario Furlan, who had repeatedly tried to commit suicide. Furlan went on to become one of the patient leaders of the movement inside the hospital. Basaglia did not just remove fences, gates, and barriers — as well as locks on doors — but encouraged the patients to take power. The patients themselves pulled down fences”

So more data would obviously change these things around especially if we expand this to things like Danvers but the more we know how a pre-existing structure declines the greater data the antipsychiatry movement can utilize not only as researchers or readers sharing their text to their fellow group but also to use against our enemies when it comes to needing to hand out studies that shows why a Basaglia Law needs to happen for example. (Especially since regardless of how much Franco fought for the movement, he never really got to do anything about the Basaglia Law. It was just named after him and now there are other laws that are worse to pump up rather than bring down psychiatry such as Laura’s Law.)

Report comment

Wow. Maybe I’m not understanding the full context of this discussion, or maybe the above post by Paul was written with a strong sense of irony…but comparing Buchenwald and Auschwitz regarding which one was “better” is deeply, deeply offensive. These are both places designed with the sole purpose of genocidal mass murder on an industrial scale – it is unbelievable to me that ANYONE can make that argument, even in these days of “Alt-Right” and neo-Nazi resurgence. Paul, if I misunderstand this comment, please forgive me; but if not, this is an incredibly disgraceful ‘argument’ to make.

And yes, it’s difficult to see past the devastation that giant institutions like Danvers inflicted on so many – destroyed countless lives, but I see some value in exploring some of the ideals of the “moral treatment” philosophy, which, while contained within a flawed, outdated “institutional” philosophy, were at least offered with a sense of social responsibility. For me, it has been an important part of advocating for a right to fresh air, which I worked on for many years in Massachusetts (the law was passed, but is not being routinely enforced). Anyway, the value of exposure to nature was respected for a time, with positive results.

Report comment

I forgive you Jonathan.

Report comment

Could you expand upon what you mean by that? How have I misunderstood your comment?

Report comment

It would be tough to expand on a post that I already expanded above Jonathan but I’ll try.

I am not sure I can add anything else to what I already wrote though.

I’ll focus on this one particular context (but this has already been addressed previously)

“These are both places designed with the sole purpose of genocidal mass murder on an industrial scale”

If you read my reply above, I compared Buchenwald specifically to Gorizia. (Right now I still see the link.)

…and I mention this because it ties to the grander theme of more studies = more opportunities to not only recreate or re-strengthen/reintroduce the Basaglia Law in modern times (a law where Franco Basaglia didn’t manage to change the law of Italy but they couldn’t do anything except name it after him because unlike the CRPD that defends the rights under the guise of Human Rights, Basaglia specifically targeted the mentally ill. There was no vague random Human Rights report that says x person is being persecuted, here’s a HR report and here’s x number of people an entity like the UN has saved but then when you follow the news it turns out the UN can’t intervene in the case of the person being reported except…report it)

This is all narrated to in that link. Franco Basaglia wasn’t a “here’s a bunch of people I saved guy” – no he was a believer that the mentally ill are functional and he proved it to society. Sure he needed other theorists or writers so that he wouldn’t just get kicked out of his position but he wasn’t a text book person. He wasn’t the type of guy who will just write The Myths of Mental Illness, go on a court case, lose most of the court case and then be famous for his books and then have fans of his mini-victories while the majority views him as a fringe who went on to join Scientology.

He went straight at the people he wanted to help. This was why he is as much associated with radical mental health as he is with antipsychiatry. His theory aside (I don’t know much about this there are few Eng sources), his actions dictated I want you to help yourself so that I can help you get out AS SOON AS POSSIBLE. I know this institution is ridding you of your autonomy the longer you stay in here and I can’t let you out immediately and let you roam around from place to place but I need you to understand that I am going to do something as swiftly as possible to your specific case.

It had an ethical seriousness to this on top of a realistic understanding of freedom in his time (regardless of what political party he associated himself with)

So Basaglia was in Gorizia and he needed to understand Gorizia and he needed to do something about Gorizia. He had no delusions or care whether people find it offensive that he was bringing all these doctors to this asylum and creating radical mental health.

He cared only that the doctors arrived, he didn’t get fired and he continued to fight to bring down psychiatry as the quote shows where he hated Gorizia.

This was what produced a Basaglia Law. The lone global law in history that took the mental health industry face to face.

It happened because Franco Basaglia (though he may or may not have desired the law) studied the specifics of an asylum. For years. He worked on it. He deployed the asylum. Made it more economically appealing even if it would temporarily strengthen the abuses in other geographically closer institutions of his time.

He may not have loved the fact that he had to study and listen to all these random prisoners and treat them as individuals as opposed to anecdotes but he kept on learning. He kept on making a Franco Basaglia ruled asylum “better” instead of clinging to what should or shouldn’t be a moral treatment.

No, he could worry about that later. Gorizia was his turf regardless of how much it was a small unknown territory and how much his fellow professionals said he wouldn’t amount to anything. He didn’t see these victims as a large group of anecdotes that needed to be freed, no he actually went out there to free these people and show them these actions free them…not in some kind of ivory tower text (though again I need to emphasize this was a two pronged attack – he also needed the ivory tower texts to protect him while he was doing the grunt work while helping educate him on how to make an asylum better) – because there was no room for theory when you can’t even go out of your way to offer a helping hand to someone.

This is the first reason behind my reply.

My 2nd reason involves a comment elsewhere in this thread related to markps2. I won’t re-copy my reply because that would be redundant but here’s the first line of my reply so that you can easily search for it:

“This still exists today in my country”

So there’s a whole misconception floating around these institutions to begin with.

People want to bring down psychiatry but they end up demonizing these facilities without understanding them and so while most facilities are more pristine or other facilities have no cameras so that you don’t know how bad they are but they are still no concentration camps – a lot of the narratives have been obfuscated so that…yes, a ward is get brought down when a scandal strikes but then where is it often reported?

In richer countries with a wider media exposure of course.

To compound the problem, how does this waterfall “cleaning up on institutions” occur on lesser countries? (I can only specifically refer to my experience on my own country and I’ve only been to two wards. 1 was consider a halfway house where staff would hand say the filter of a cig they smoked to patients and 1 was a prestigious local hospital where everything was pristine but all the hospital policies allow for cases of mental torture inside in the three times I was sent inside. For ex. when (I think) a JCI inspector was coming staff were so concerned about putting a pillow on my bed to keep up with the standard but they had less urgency when they were inserting a tube up my nose. Everything was a joke to the lower level staff while the top level doctors and the mid-level doctors scurried around the institution and occasionally talked to a patient.)

Everything looks pristine though especially if it’s your first time in and out. When it was over-crowded, it meant a room designed for holding up a patient that was sound proof would have a patient on it but you didn’t get any over-crowding because protocols were in place to keep a 1 patient per 1 room facility.

Not to mention there were always hospital policies being hidden from you. For ex. it was only my third time that I could go out of the psych ward provided I was escorted by an off-duty staff but I needed this in my 2nd psych ward because I badly needed to consult other non-mental health professionals on top of my low energy levels requiring me to exercise. (the real functional method not some mat you place during break time inside the psych ward so that it looks like you are doing some activity)

It didn’t happen though because it was only in the third time that a patient actually knew of this key word so she had this privilege and of course once she had this privilege I can also use this privilege provided I can present it properly to my psychiatrist that I knew this keyword and it would be “therapeutic” to me.

So I need a lot of these details to better make my move since every element of these institutions waterfalls down into my country and if I need it, I know someone else needs it because the reports aren’t dwindling in terms of how many people are affected by the psychiatric business model as quickly summarized in this reddit post of mine:

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/9f2j6w/serious_youre_given_the_opportunity_to_perform/e5tw2ng/?context=3

Report comment

Hi Paul,

Thanks for describing your view in more detail. I appreciate your ideas and dedication to a worthy pursuit. I also read the article about Basaglia, which was very interesting.

However, I still can’t understand the Buchenwald vs. Auschwitz comparison. While I completely agree the abuse and mistreatment of people in mental institutions was and still is a massive, horrific and largely-overlooked part of history, I believe that comparisons to the Holocaust, are, for lack of a better term, “apples to oranges” comparisons. Auschwitz and Buchenwald were places designed for the sole purpose of extermination of human lives. As someone whose ancestors were murdered in the Holocaust, I think we have to be careful when using past events for comparison’s sake.

Report comment

Let me qualify first by saying I belong to MIA because I have a dx and consider myself to have been very inappropriately “treated” in the current system. Having said that, I likewise wrote a brief piece about the time period when Raleigh NC’s Dorothea Dix hospital was a functional community of people with diagnoses and the live-on-campus staff who supported them. I “discovered” this subject after I met several people who had grown up on the campus, knowing that the place they lived was stigmatized and also seeing their parents welcome patients as guests when the kids sat down for afterschool cookies in their on-campus homes. There’s every reason to abhor what can happen in institutions; there are also reasons to consider how structured settings can facilitate life success. There’s a great deal of appropriate nuance in this conversation.

https://churchandmentalillness.wordpress.com/2017/07/29/dorothea-dix-built-inclusive-communities-for-mentally-well-ill/

Report comment

there are also reasons to consider how structured settings can facilitate life success

Forced success? (Just trying to clarify.)

Report comment

I do. And I think the story is great.

Report comment

I would like to comment back in the days before science most mental illnesses were in fact physical illnesses such as syphilis.

Back in the days before science, they had no blood tests and no penicillin.

That era and today can not ever be compared from because there was no SCIENCE at that time.

People who went to hospital/asylums at the time and who recovered were known as addicts. Once free to resume their addiction many went back to their addiction.

This is not medicine but morals. Locking people up forced them to be moral or abstain from their addiction.

The author is also confused as to what a hospital is and what a prison is. If you can not leave the room you are in, that is a prison, not a hospital. Those in authority do call it a hospital as there is no one to oppose the statement.

“Why were these hospitals successful?” Who reports the success versus failure? The lobotomy was judged a success by those that gave the operation. and the new technique to control the “ill”, given a Nobel prize.

Locking people up does control them and does stop them from abusing drugs and alcohol and such things. You can call it medicine? Who is paying for the medicinal treatment of steel and concrete walls?

Report comment

This still exists today in my country:

People who went to hospital/asylums at the time and who recovered were known as addicts. Once free to resume their addiction many went back to their addiction.

This is not medicine but morals. Locking people up forced them to be moral or abstain from their addiction.

Report comment

I don’t think you understand, Katherine.

The history, the documents, who wrote them? whose accounts are available to history? Did you cosider the capacity for for patients to complain or assert any thoughts, feelings aor decions about themselves, their experiences or their lives in this situation, or to make choices about much of anything

What about the decisions about which records should remain, and the context of what could happen should anyone complain? In regard to decisions about what and who was photographed, who made them and who held the camera?

Any comments and reports from patients and their famlies – in what context were they made? Who chose what was heard and kept on record? Did even the voluntary patients have any real voice?

And what about the beliefs and expecations in the wider community, how did these filter the understandings of everyone concerned?

Mad people were marginalised in, and rejected by communities, and often their families. These were institutions. There was even less accountability than now for those who worked in these places. I feel that creating fairy tales from the self-serving records of those with almost unlimited power and little or no scrutiny, about their own benevolence is to make myths. This was the context into which the drugs, lobotomies, shocks etc., were birthed. They did not corrupt a previous garden of eden. Things could well have gotten worse with their arrival, but I don’t think it is wise to understand the oppression and cruelty of psychiatry as being caused by them. To do so is to minimise, deny and misconstrue oppression.

Report comment

Katherine, Interesting though the comments here are correct – this is old stuff and it pays to be sensitive to those who are reading. That being said who asked you to write it and submit?

It is important to know the curve and trajectory of history but there are slot of gaps like maybe Bedlam? And the Dalem Witch Trails right up in your state. One reason was possible Ergot poisoning. That is worth a blog right there.

I think one reading one of these articles it would help to know many many states had institutions like these and many are still alive who were in them or like mevisted and or did volunteer or fieldwork in them. All of the ruined buildings are places for the kids to go in and get scared.

Matter of Fact there was a big movement just awhile ago about this very topic. Halloween and the insane asylum for fun and profit. No.

The point on the graveyards.Just like in Ireland. I strongly recommend the movie about the Magdalene Laundaries – very unsettling but true. In Taum numbers and numbers of small bodies were found and I would be if a dig was done in an asylum some small bodies would be found as well.

Also before writing I would suggest you do some research on the West African port city? that was the dispatching site for the Slave Trade. There are several good media pieces about African Americans walking through the holding rooms.

I think this is still important as one day one hopes the well intentioned good and the horrors are catalogued as past history as the families and children who have been detained by our government will walk through the buildings and walk through not as refugees but as free people. The same with Rikkers and other heinous facilities.

Report comment

The incredible meanness of psychiatry is in the substitution of fundamental moral represent. – Man, his will, his feelings, beliefs, his individuality are marked by illness. That is, a person is designated as a disease. And further with the person it is possible to address, as with illness. Ignoring the will of the man himself, ignoring all his protests! After all he is not a person, he is a disease. And doctors know better what to do with the disease. Clear, is in this situation with a person can do anything. And everything can be imagined as helping a person. The worst example of discrimination is not found! And of course at all times psychiatry was aimed at destroying the objectionable. And used the funds that were available at that time.

Report comment

Katherine who is your target audience?

Thorzine and other brain damaging techniques helped Danvers pack warm bodies in till they were overflowing. Ugh. No wonder things went downhill. I hate psych drugs more than ever.

I have been in some jam packed, depressing places that stunk of urine and stale cigarettes. I was another body to stuff in till I died. Thank God I escaped!

If you aren’t crazy when you enter they’ll take care of that. Horrible. 🙁

Report comment

Danvers began in the 1870’s. (I couldn’t find the exact date here.) Thorazine was invented in the 1950’s. So I don’t think Thorazine helped Danvers do anything. I’d guess Katherine’s “target audience” is as much of the general public as she can reach. She wants to sell books. Duh. But educating the public is more important, and I bet Katherine agrees with me on that. We’ve both been in some psychiatric snakepits, it sounds like. But if Katherine’s story about Danvers gets us so upset, maybe we’re still back there. I only get stressed thinking about the places I was actually tortured and incarcerated at. And yes, I, too, heard that line, “If you weren’t crazy when you got here, then you will be when you leave.” And, our “recovery” will be a life-long process. We can NEVER be who we would have been, if we had never been subjected to what we were subjected to. You can turn a cucumber into a pickle, but you can’t turn a pickle back into a cucumber.

We here at MiA are ALL “psychiatric pickles”! (Dills are ok, but too sour. I like sweet gherkins the best!)

Report comment

“It was built in 1874, and opened in 1878…”

‘The entire campus was closed on June 24, 1992 and all patients were either transferred to the community or to other facilities.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danvers_State_Hospital

“Chlorpromazine (CPZ), marketed under the trade names Thorazine and Largactil among others, is an antipsychotic medication.”

“In December 1950, the chemist Paul Charpentier produced a series of compounds that included RP4560 or chlorpromazine.”

“By 1954, chlorpromazine was being used in the United States to treat schizophrenia, mania, psychomotor excitement, and other psychotic disorders.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlorpromazine

1954 to 1992. That adds up to 38 years of potential Thorazine use at Danvers. Thorazine, for a spell, must have been used to help Danvers manage it’s inmates.

Report comment

Psychiatry has always been atrocity. But in former times she did not have in its arsenal such refined, destructive means. What happens as a psychiatric “cure” for the last 70 years is a fantastic nightmare! And this is mainly “thanks” to the new “therapeutic” means. Torazine (in Russian transcription – aminazine) appeared in the early 50’s. And since then has been and is the most effective, not replaceable means of suppression. This is an incomparable destructive tool! It is unlikely that in any other way can cause such a total damage to the human being!

It is no accident that these “universal tools” appeared shortly after the war. In Nazi Germany, medical experiments on people were put on stream. For this there was a suitable condition – a huge number of prisoners of extermination camps. No consent of the victims was, of course, required. Undoubtedly there, in the Nazi camps, pharmacological means of destruction were constructed. But only the themselves nazis professionals bring experiments to the desired result apparently did not have time. Herefore, their ideas were subsequently implemented by criminals in other countries.

Report comment