In a new study, researchers analyzed fMRI brain imaging data for children with autism diagnoses, ADHD diagnoses, and no diagnoses (referred to as “typically developing”). They specifically looked at functional connectivity, a measure of how well parts of the brain “communicate” with each other. They found that there were no brain differences between any of the diagnostic categories.

The researchers also theorized that executive functioning (a measure of cognitive skills such as attention, memory, planning, and problem solving) might be related to functional connectivity, independent of any diagnosis. However, they found no brain differences between children with different levels of executive functioning, either.

The research, published in NeuroImage: Clinical, was led by Dina R. Dajani at the University of Miami. Other researchers involved hailed from Johns Hopkins University, the Kennedy Krieger Institute, the University of Minnesota, and Yale University. Dajani and the other researchers write:

“This work contributes to a growing literature suggesting that traditional diagnostic categories do not define neurobiologically separable groups.”

Previous research on functional connectivity in the brain has been inconclusive. Some studies have found slight average differences in this biological measure between children with an ADHD diagnosis compared to children without a diagnosis, or children with autism compared to children without a diagnosis.

However, most research has found no such brain differences. Even the differences that have been found could be the result of false-positives, which have plagued the neurobiology field in recent years. According to the researchers:

“The neuroscience field is becoming increasingly aware of the lack of reproducible findings across studies, which may be the result of low sample sizes, inflated false-positive rates due to analytic choices, and heterogeneity inherent to groups of interest.”

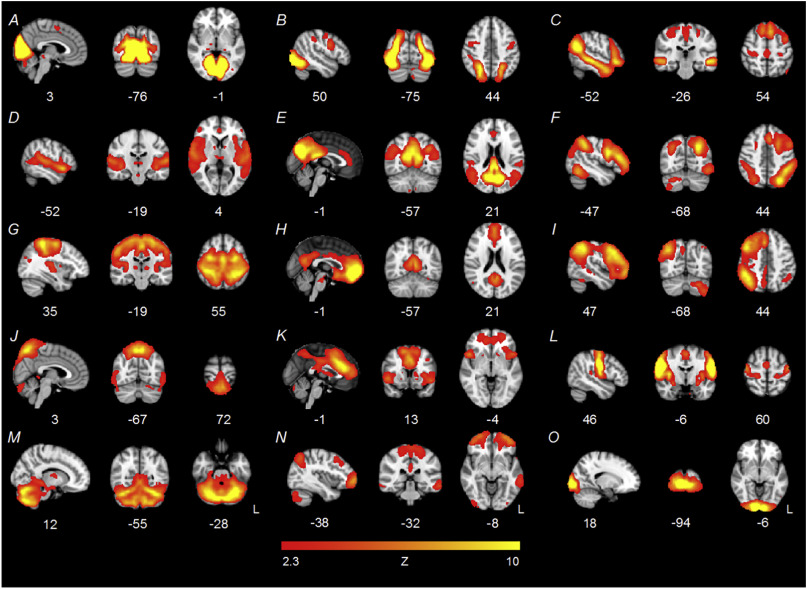

Dajani and the other researchers wanted to clarify these contradictory findings, so their study used larger samples and targeted methodology. They studied the fMRI data from 168 children (ages 8-13) divided into three groups: children with an ADHD diagnosis, children with an autism diagnosis and children with no diagnosis (referred to in the paper as “typically developing”). Some children had both autism and ADHD, so additional analyses were performed to assess whether having both diagnoses made a difference.

The researchers found no brain differences between the diagnostic groups. That is, children with “typical development” did not have different brain activity than children with ADHD or autism diagnoses.

The researchers then divided the children up separately by executive functioning—independently of their diagnosis. They made three groups: above average, average, and below average executive functioning. They then compared the functional connectivity for these three groups.

Again, the researchers found no brain differences between the groups. Even the above average and below average executive functioning groups had similar brain activity.

The researchers argue that previous findings of brain differences likely “represent false positives due to low sample size.” They suggest that the diagnostic classification system—at least for these two diagnoses—does not have a basis in neurobiology, nor does the behavioral classification of executive functioning skills.

Their conclusion is that brain science cannot distinguish between ADHD, autism, and typically developing children, nor can it distinguish between different levels of executive functioning.

****

Dajani, D. R., Burrows, C. A., Odriozola, P., Baez, A., Nebel, M. B., Mostofsky, S. H., & Uddin, L. Q. (2019). Investigating functional brain network integrity using a traditional and novel categorical scheme for neurodevelopmental disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical, 21(101678). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101678 (Link)

Autism is like taking meth, or am i wrong? I mean that when a child with autism perform certain actions, the level of serotonin increases.

Report comment

I think nobody knows what a child with autism feels.

But i made this picture in a state of cannabis induced psychosis

https://imgur.com/lHVsWT8

And now i read that children with autism may have a refusal to eat, selectivity in the choice of dishes.

I felt the same. It is possible that all children are in a state of psychosis up to a certain age, but children with autism are stay in it longer than usual.

I thought that food is like an illusion or a hoax.

Report comment

And also it was like taste of products led to certain associations and images in the brain (not images but something like that, it is hard to explain)

Report comment

Can one “assume” that the prevalent fixation in other tendernessing given market preternities causes the electromagnetism of the machinery’s scans to give way to more locked up values?

Or is it more an inclusive barrier within the field?

And when such a field expands to the size of prior tragedies, is it’s intake of sufficient priorities to be oblique or of appropriate distance from where it would have been, given need of testing, when there’s no need of it?

Report comment

Thanks for the science!

Report comment

Or, at least pointing out, the lack of scientific validity, of the DSM disorders. One must wonder how long it will take for the “mental health” workers to garner insight into reality.

Report comment

ive sometimes wondered if -in some cases- “autism” is a medically-sanctioned form of child abuse. Even many mainstream people doubt ADD/ADHD, or did when I was in my late teens (been a while…), but “autism” has this air of “bona fide science” about it…

and yet, it seems to be more DSM bullshit, too. funny, that.

but, yeah. ADD/ADHD is useful in some families (and foster care, obviously), but it can also be useful for more afluent kids dealing with the pressures of growing up and also excelling at school, extra-curriculars, etc. and…after a certain age, the uppers go from being force fed to the kiddies to being requested, by name…often so they can share them with friends. but autism?

autism, to me, is sort of like “Schizophrenia” was in, say, the 50s and 60s…its a convenient label for the people in power, not so much the person so labeled, and the younger a person is when labeled…

the more I wonder…

and yet, I see families struggling with obviously suffering kids, and the parents don’t like the psychiatrists, either. what’s that about, you think?

Report comment

At least some cases of “high functioning” autism could be attributed to extreme awkwardness. Asperger’s for instance.

Report comment

I would like to know what people who have this label find useful about it. They obviously do though the science is non existent behind the diagnosis.

Report comment

if family, “experts,” etc. apply the label early enough…and the label is drilled into the ‘autistic’ individuals’ mind, combined with drugs and whatever non-drug ‘treatments’ are out there…

I would think it would take a lot for them to move forward in life, anyway, so the label might then be…just a role they found themselves thrust into, one they play as best they can.

Report comment

Like how Szazs described “mental illness” as a role people play. Educators know it’s harmful to label a kid “stupid,” “liar,” “lazy,” or “worthless.” But somehow they think these names help them.

Report comment

They mention “heterogeneity of groups of interest.” This is a very oblique way of saying that the people “diagnosed” with these “disorders” have little to nothing in common. Which can even more directly be reframed as “These diagnoses are all bullcrap!”

Report comment

The diagnoses might be a description of behaviour like” too fast” or “too slow”, but the trouble with giving such a description-diagnosis to a child or anyone under the age of 18, is that the diagnosis is self fulfilling.

The doctor says I have a low attention span due to a disease? That’s a great excuse for not taking responsibility for my actions, for not trying to get better. I got a disease! My actions and inaction are a result of a disease. The doctor says so!

This is the TRUE danger of psychiatric diagnosis, the nocebo effect.

Report comment

Have you, or, will you, consider that the child wants to learn? She goes to class eager to learn. She wants to follow along, to contribute. She wants to understand what is being taught and discussed. However, for some unknown reason she sits in class and tries to follow along, but she can’t. When she’s called on, she blushes and can’t respond. She’s laughed at. The teacher moves on to another student and the child is embarrassed, hurt, confused and feels all alone and afraid. What about her?

Report comment

You are assuming that the “ADHD” child WANTS to learn but is UNABLE to learn. If that is the case, why is it that one review after another over decades shows that stimulants create more “on-task” activity but do NOT translate into more learning/understanding in the long run? Is it possible that the child is being forced to do “work” that is not actually educational for them? That they already understand the material and are simply bored by having to “practice” over and over and over again doing something they already have down? Or that if offered a more hands-on, active, self-paced opportunity to learn, they would thrive on it, but such an opportunity is simply not made available to them?

I’d also ask you to explain why long-term outcome studies show no discernible effect on self-esteem, if these shaming experiences are theoretically reduced in number? Is it perhaps that we are replacing one shaming experience with another, telling a child he “needs his meds” in order to learn things? Singling him out as “disordered,” often in ways that are obvious to everyone in the classroom? What does it do to a kid’s self-esteem when told that his brain “doesn’t work right” and that he needs a drug to “rebalance his chemicals?” What happens later on in life when he discovers that he was actually lied to about that supposed “fact” (because as we should all know by now, the “chemical imbalance” theory is dead, even in mainstream psychiatric research circles)?

I was a shy kid in school. I had no trouble understanding anything the teachers were trying to teach us, though I did get frustrated at the ridiculously slow pace. Frankly, I was BORED TO DEATH, and no amount of increased “time on task” was going to teach me anything I didn’t already know. And trust me, I daydreamed like mad, and often completely tuned out the teacher droning on about something I already understood. I needed some NEW TASKS in order to learn more, not more time on the same boring tasks that I’d long since mastered!

I was very good at “complying,” so stayed out of trouble, but was terrified to talk because of the potential shame involved in exposing oneself to possible ridicule from the teacher or the other kids. I got embarrassed, turned red, and could not respond. I was laughed at. I avoided talking so as not to keep having that experience.

So what was the problem, Enrico? Was I “disordered,” because I was sensitive and easily embarrassed? Was my constant daydreaming an indication of me having “ADD without hyperactivity,” or a sign that I was in an incredibly dull and unstimulating environment for hours on end every day? Was I “disordered” because I didn’t want to risk getting humiliated? Or was the problem PERHAPS that the environment was a complete and total setup for a shy person like me to be exposed to? Was the fact that no one gave a shit whether or not I was shamed or embarrassed, or that the teachers themselves often PARTICIPATED in the shaming behavior perhaps a factor in why I was so reticent? Today, I would no doubt be “diagnosed” with “Social Anxiety Disorder” and efforts would be made to make me more participatory and to be able to “control my emotions” so I was “tough enough” to handle the inevitable shaming experiences that would ensue. My needs would be invalidated, and I would be accused of being a failed person because I couldn’t easily “fit in” to what I was expected to do.

Kids should not have to learn in a shaming environment. They should not have to learn in ways that risk trauma if they participate. They should be able to learn in ways that work for them, instead of having to be forced into a rigid structure that takes their normal ways of learning and makes them a source of shame and embarrassment? Instead of trying to alter the kids’ personalities, maybe we ought to teach our teachers how NOT to shame kids and how NOT to set up situations where other students can shame them as well?

Another interesting study showed that kids diagnosed with “ADHD” actually LEARNED MORE WHEN MOVING AROUND! So by forcing them to sit still and “pay attention” to the teacher talking, we are STOPPING them from learning. If giving them stimulants makes them more willing to sit there and take in all the boring “information” being tossed at them, that apparently doesn’t translate into them learning any more than they would have if they goofed off the entire lecture. In fact, they’d probably learn MORE if they were allowed a half hour of searching the internet and reading about what they’re interested in than they do sitting through a lecture in a chemically altered state.

I’ll again refer you back to the 1970s era study on “ADHD” kids in open classrooms. They stood out like sore thumbs in a “normal” classrooms, but professionals COULD NOT TELL THEM APART FROM THE “NORMALS” in an open classroom. So instead of drugging kids so they can sit still through a boring lecture and get higher points for “Stayed on task,” why not create open classrooms for anyone who needs or prefers that style of learning?

Remember also the study showing that these supposedly “disordered” kids were a critical element in groups of elementary school kids actually solving problems. They brought something to the table that three “normal” kids would have benefitted from. Why do we want to suppress that strength, just so that teachers and parents have an easier time?

The fact that teachers and other students hurt, shame and confuse other kids who don’t function well in a standard classroom is the fault of the teachers and the system they work with. As I’ve said before, my own kids had NO STIMULANTS despite pretty severe “ADHD” symptoms, but both graduated high school with honors and are paying their own way in the world and have functional relationships and goals and are functioning in every way as a contributing member of society. No one today would “diagnose” them with anything at all. What was different? We didn’t try to force our “square pegs” into the “round holes” of the school system until THEY decided they were ready for it. We loved and respected them, but of course taught them things they needed to know, including how to discipline themselves and how to get along with folks they disagreed with. Neither of them were in the tiniest degree unable to learn. In fact, they are both brilliant, fast learners! But they did not learn the way that schools expected them to learn. We never considered that their fault.

You are asking others to consider your hypothetical scenarios. What about my very REAL scenario of my two kids, and the research that supports what we did to help them mature into functional adult citizens? Does that suggest that alternative viewpoints may not only exist, but in fact be viable ways to view the situation that lead to positive results?

Report comment

Read the literature in order to not say bullshit: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328734204_A_theory_of_evolution-biased_reduction_of_gene-expression_manifesting_as_autism_the_antiinnatia_theory_Improvedupdated_presentation_of_A_theory_of_general_impairment_of_gene-expression_manifesting_as_

Report comment

So when does the recall of ADHD drugs begin and those to whom they have been falsely prescribed compensated?

Report comment

Psychiatry is not a branch of medicine. It is monotheism in medical disguise. Psyche belongs to polytheistic reality. But theology/religion creates the foundations of philosophy behind the psychiatric dehumanization.

We live in the world created by the words.

Monotheism destroyed the wor(l)ds which described polyheistic reality. Our philosophy is also based on religious fundamentalism. The victims of psychiatry are victims of monotheism.

Science is also a weapon of monotheism, because science defines the raison detr’e. And psyche is not scientfic thing — so it does not exists or is not REAL for materialists. Psyche belongs to reality BEYOND the wor(l)ds of materialistic primitives.Apollonian ego fundamentalism is based on theology, not on human (polytheistic) assumptions. Monotheism and science destroyed psychological reality.

————————————————————————————————————————

Psyche needs Copernicus not pseudo medical masqueraders.

Autism and schizophrenia are the heart of psychological reality.

Apollonian ego (normal people) are monotheistic enemies and the destroyers of psychological reality. Polytheistic reality.

Apollonian ego, science, religion = materialism, monotheism

Psyche (autism schizophrenia depression) = non materialism, psychological polytheism, but this is no metaphysics.

Psyche is non theological and non material thing. So schizophrenics, autistics, depressed are not real human beings. They does not exist.

——————————————————

Antichrist = Psyche (human psyche, not monotheism)

—————————————————-

James Hillman Re- Visioning psychology.

Report comment

Materialism = monotheism, science, religion, theology.

For the materialists psyche is the brain or some kind of spiritual utopian non human reality.

Polytheism describes real human reality. Polytheism is not a religion, it is a philosophy which supposed to created the foundations of nowadays psychological reality.

Atheistic people, materialists are also the apostles of monotheistic reality.

Report comment

Autism and schizophrenia are PSYCHE.

AND GOD AND MATERIALISTIC PEOPLE ARE AGAINST PSYCHE.

It is obvious that antichrist revenge is correct answer to anti human fundamentalism.

Report comment

If god is a chaos, and it seems like psychiatry is a chaos then you’re right. But psychosis is also a chaos, and only depression is the order

Report comment

Actually, chaos theory (from mathematics) might be more useful for understanding human behavior and emotion than almost any proposed psychological theories about such.

Report comment

If there is any hope of a scientific understanding of the human mind, Chaos Theory appears to be the only sensible way to start. But psychiatrists aren’t mathematicians for the most part, except that they do know how to calculate income as related to type of “treatment” offered, apparently the only graph of any real importance.

Report comment

“Actually, chaos theory (from mathematics) might be more useful for understanding human behavior and emotion than almost any proposed psychological theories about such.”

I agree, this is absolute truth. You nailed it, KS. Problem solved, like in math.

https://fractalfoundation.org/resources/what-is-chaos-theory/

“Chaos is the science of surprises, of the nonlinear and the unpredictable. It teaches us to expect the unexpected. While most traditional science deals with supposedly predictable phenomena like gravity, electricity, or chemical reactions, Chaos Theory deals with nonlinear things that are effectively impossible to predict or control”

Report comment

I really like the Wikipedia entry on this one. It’s written for dummies like me in plain English:

“Chaos theory is a branch of mathematics focusing on the behavior of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions. “Chaos” is an interdisciplinary theory stating that within the apparent randomness of chaotic complex systems, there are underlying patterns, constant feedback loops, repetition, self-similarity, fractals, self-organization, and reliance on programming at the initial point known as sensitive dependence on initial conditions. The butterfly effect describes how a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state, e.g. a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can cause a hurricane in Texas.[1]”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaos_theory

It accounts for the millions of random environmental inputs that make us unique, and it follows that if each of us are a unique series of inputs then attempting to label and “fix” the natural results of those inputs is misguided at best.

Report comment

Right, there is nothing to fix. We can work with the chaos. I don’t see us as humans being powerless to the chaos, but more so we participate in it. It is our nature. I think when we take that in, we can stop struggling against it as though there were something “wrong” with chaos, and instead work with it in a way that is fruitful and reassuring. Like going with the stream rather than struggling against the current to go upstream.

Chaos is nature and nature is chaos. There is always an “x factor,” which makes life interesting, challenging, and creative–anything but static. How we organize this within ourselves depends on many things, but ulitmately, it determines how we experience our reality, which is also unique.

We can create order out of chaos for the purpose of manifesting something, but that can go away as quickly as it came. The chaos is constant, underneath it all. Good stuff, I think, real truth.

Witnessing is the power here, I think.

Report comment

God is not a chaos. God is the anti psychological fundamentalist, he represent the spiritual fanatics. The confused psyche with spirit.

Apollonian ego is also confused with Christian spirit.

Apollonian ego fixation over controlling the rest of psychological reality is the main problem, not “mental illness”. Psyche is just a psyche, psychopathology is just somethong different than apollonian ego easy reality. Apollonians (normal) are the real crazy ones.

Their sick attitude towards the things they cannot control is a lethal danger to the psyche. They are spiritual and egoic fanatics. Their problem is that their psychological life is too easy.And, easy, from psychological perspective, means also dumb, blind, convenient, shallow. Stupid. Normal people, spiritualists, are just too stupid to realize what psyche is.

From psychological perspective, mental health (apollonian ego) is equal to some kind of mental weakness or stupidity. No matter how well mentally health are well adapted to material reality, psychological man means——- more than apollonians.

Cosmos is something more than Earth, and Earth belongs to cosmos. Earth cannot exists without cosmic reality.

Apollonian ego belongs to Hades (psychological reality) Hades is a matrix for apollonian ego.

Apollonian ego (normalcy) does not exists without Hades reality (mentally ill). Because Hades reality is the main reality.

Normalcy is a form of tragic deformation of psychological reality. Normal people are just more unreal than “mentally ill”, because they are far far away from strict psycholological reality. from death reality, and death is the truth. The are more unreal that they think. They reject death and suffering on psychological level, without their will, of course. Their archetype is extremely easy to endure. Normal people are extremely simple, compared to strict psychological reality.

They will never agree with that fact. That they are more unreal than those called “mentally ill”, because of their tragic psychological blindness.

—————————————————

Psychological reality means more than normalcy.

—————————————————–

There is a hierarchy in psychological reality. Materialists have forgotten about it.

Hillman is the key to understanding the psyche.Because he is the only key.

Report comment

Reading this made my heart feel so heavy and sad 🙁

Report comment

Alex, this was really well stated. I like the idea of working with the chaos. 🙂

“Right, there is nothing to fix. We can work with the chaos. I don’t see us as humans being powerless to the chaos, but more so we participate in it. It is our nature. I think when we take that in, we can stop struggling against it as though there were something “wrong” with chaos, and instead work with it in a way that is fruitful and reassuring. Like going with the stream rather than struggling against the current to go upstream.”

Report comment

Actually Alex, what you said reminds me I am not a salmon, and made me think of the song Swim by Jack’s Mannequin. Have you heard it?

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=sA8PaIw5gcE

Report comment

I had not, this is awesome! Thank you for posting it. This lyric really spoke to me big time–

“You gotta swim, swim in the dark

There’s no shame in drifting

Feel the tide shifting and wait for the spark”

Simply beautiful.

Report comment

ALex: I think that nature is not a chaos, but rather as an electrical gadget , only instead of electricity it uses a chaos, yes we have our own batteries (brains), but they don’t work very long and there are things like lightning (psychosis) and static electricity (autism) that we don’t understand. That is why when people reduce brain activity with psychedelics, they often report the occurrence of synchronicities.

Report comment

Salimur, I think we all have our take on this, nothing is set in stone about it. I believe it’s a matter of how we take in and interpret the nature of life, based on who we are and how we organize information. It’s different for everyone. I see it as an exploration.

With that said, what comes to mind from reading your post is that I do feel we run energy akin to electricity, that our bodies are comprised of a continual action of electrical impulses, which would be our brain activity in relation to our nervous system, and all the signals that go out to the different parts of our bodies for the sake of functioning. It is why grounding is vital, the way we ground our appliances so they do not short curcuit. We have circuitry, too, that is our nature.

Everyone experiences lightning and static electricity, these are most natural and universal. So to liken them to “psychosis” and “autism” only works for me if you’re saying that we exist on a continuum and each of us can achieve these extremes. That would be human nature, not just the nature of “some people.”

Perhaps we all go in and out of different aspects of the contiuum without even realizing it, if it is our nature. So the question would be, why do some people get stuck at the extremes and wind up labeled, and rather boxed in for life, based on these labels?

Finally, I’ve never heard of “synchroncity” being associated with “reduced brain activity,” although it makes sense now that I think about it. I associate synchronicity with increased awareness, especially present time awareness. It is one way we witness life happening in the moment.

Too much brain activity means we are running a lot of electricity and that takes us out of the moment, and also out of our grounding, so indeed, we would not notice the synchronicity. Which is too bad, because synchronicity is the magic of life! It is all around us all the time.

I would say heart activity is a higher current of electricity, so to speak, than that of brain activity. Brain activity is dense and heavy, to the point where it can lead to fog. Heart energy is aligned with love. That is our nature, too, I believe. And love can be, both, healing and quite chaotic. Still, there is clarity in love.

Report comment

ALex: I agree with all that you said. Especially about the heart, since our heart, stomach etc. have a certain autonomy, so as not to overload the brain.

I just wanted to pay attention that you can’t get chaos (real randomizing) even using the most powerful computers (I know this as a programmer), so why do we expect this from nature?

I think that randomicity is something that can be implemented on a quantum scale, such as quark and gluon field fluctuations etc.

And Darwin’s theory tells us that mutations are random, but it doesn’t tell us how they can be random.

On the other hand, we have paranoia (occuring synchronicities).

I think that synchronicities is the universal language of nature, it is a tool of evolution.

I like the quote by Antero Alli:”Yesterday they called it coincidence, today its synchronicity, tomorrow they`ll call it skill”.

Report comment

“I just wanted to pay attention that you can’t get chaos (real randomizing) even using the most powerful computers (I know this as a programmer), so why do we expect this from nature?”

This is very interesting and your question makes perfect sense. I do find paradox here because in one sense we can say nature would be infinitely organized (I can only imagine) and on the other hand, it can create chaos, so I can also imagine it by nature being chaotic. Plus, I am always able to say I feel my chaos, even though I’m a very focused and highly organized person. But it takes effort to focus and I also like to relax and just allow, be “in the flow” as is said, which is when I feel my “chaos.” Which is fine, I’m good with it, still grounded and all.

I’m also an extremely creative person, so the chaos is exciting to me, not at all disorienting. I do create and manifest from chaos, all the time. To me, it feels like my nature, with which I’m totally aligned, so I guess I’m projecting onto nature from my own sense of self. But then again, isn’t that what any of us would do, how it works?

Perhaps we are the ones projecting the chaos so that we can create from it, maybe that’s the human element of nature which brings this. We are definitely unpredictable, never know how we’re going to feel from one day to the next. Chaos is much more interesting than “perfect order,” although there is beauty in symmetry, as well. But we are such creators, I think, that I do believe is human nature. We create one way or another, whether consciously or not.

I’m seeing both sides of this paradox, and I very much appreciate what you say here because you are a progammer and you would know this, so what you say does give me pause. Definitely food for thought, thank you for that!

“On the other hand, we have paranoia (occuring synchronicities).

I think that synchronicities is the universal language of nature, it is a tool of evolution.”

That’s beautifully put. Yes, universal language of nature and a tool of evolution, I’d agree completely with that. But I’m not clear on where “paranoia” fits in here–unless you mean that we can interpret synchronistic events through a lens of fear, which then I could see how paranoia could develop from this. But that’s more about the beliefs we are carrying, not about the synchronicities. Not sure whether or not I’m understanding you correctly here.

I experience synchronicity all the time, and it’s always a good feeling, joyous and affirming. Makes me feel that I’m on my path, and that things are lining up with whatever intention I have at the moment.

It’s been during times where I am lacking synchroncity (or better said, I am not perceiving it due to lack of focus) where I’ve felt in the dark and with a lot of anxiety. Whereas the synchs bring me reassurance, calm, and confidence–a feeling of light and certainty in my body. It is a very good feeling, like, no worries!

Report comment

Brain Scan Blob Pictures Too Macro to Detect Micro Differnces, would be a more honest headline.

Report comment

in the 50s and 60s (in particular…) “Schizophrenia” was -the- diagnosis in both the US and the USSR. mild “Schizophrenia,” “hebephrenia,” “residual Schizophrenia,” on and on it went. In the US, the meaninglessness of “Schizophrenia” became so obvious, and the shrinks were arrogant enough to apply it to people who could (and did) escape their clutches, that it was thoroughly deconstructed. Think…Szasz, even E. Fuller Torrey (“what do you think happened with Torrey?” “FUNDING”), Kate Millet, on and on it went. And now…

there’s 31 flavors “Bipolar” and then there’s “autism.” I’ve seen people use the “autism” diagnosis/label for their own purposes…because they think they will “understand themselves better” (pop psych, plus an alienating culture=lots of this BS exploitation mischaracterized as “self-actualization), but I’ve also seen–thankfully, at a distance–kids labeled and ‘treated…’

and that, to me, says something not only about the families I’ve observed such labels being used in, but (I think…) society as a whole, in the 21st century US.

I’ve read on psych forums, “concerned parents” writing in about “autistic” child+teenage off spring, the pills, the hospitalizations, and….yeah. I imagine the exact benefits and drawbacks of the label vary by social location (education levels, income, overall social standing come to mind as top factors), but the overall theme I personally get from many (but not all) of this is…

abuse. abuse and control and sometimes, I suspect…the same impulse that led everyday citizens to sacrifice their kids to Molech and other deities way back when are at work in parents (and other family caregivers) who give their kids over to psychiatry.

of course, even the under 18 set can have a purpose in engaing the psych professions. attention, stress, loneliness, perhaps the parents are mean-spirited and the psych labels can offer a buffer against their cruelty…myriad possible reasons/motivations, all leading to psychiatrization and labeling.

Report comment

Have you, or, will you, consider that the child wants to learn? She goes to class eager to learn. She wants to follow along, to contribute. She wants to understand what is being taught and discussed. However, for some unknown reason she sits in class and tries to follow along, but she can’t. When she’s called on, she blushes and can’t respond. She’s laughed at. The teacher moves on to another student and the child is embarrassed, hurt, confused and feels all alone and afraid. What about her?

Report comment