COVID-19 has forced us all into new ways of being, new ways of relating, and new ways of responding in a time of crisis. These new ways reveal more clearly than ever how essential dialogue is to the human experience. We are all to some degree shaped by the dialogues we are born into, and the ones we join as we move out into the world. Now, more than ever, we are engaged in a global dialogue, the outcome of which will shape our uncertain future.

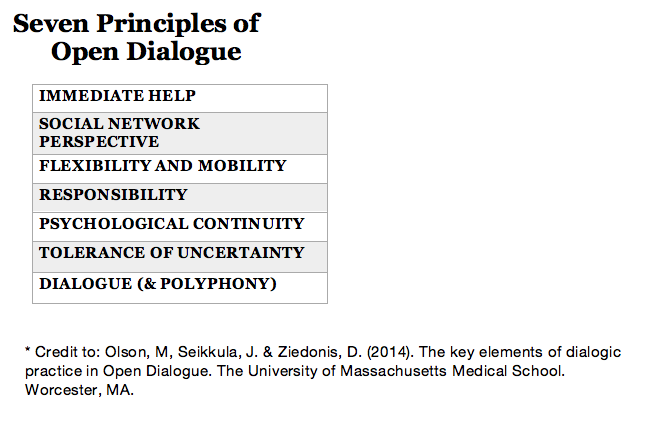

Dialogical practices, such as Finland’s Open Dialogue, and Hearing Voices Groups, have been working and learning for over three decades how to respond to crisis by convening those affected into dialogue.

Dialogue goes back to the origins of humanity. Dialogical thinking adds to this the notion that dialogue itself is core to the experience of being human; that we make sense of the world, and meaning, together. “Madness,” therefore, is what we see or feel when this process goes awry or is blocked. People who are unable to find the words for the dilemmas they face, or whose words are not heard, might grow increasingly strident or bizarre in their efforts to make sense of things and to be heard, or they might give up entirely. The cure is to get the dialogue started and on track again.

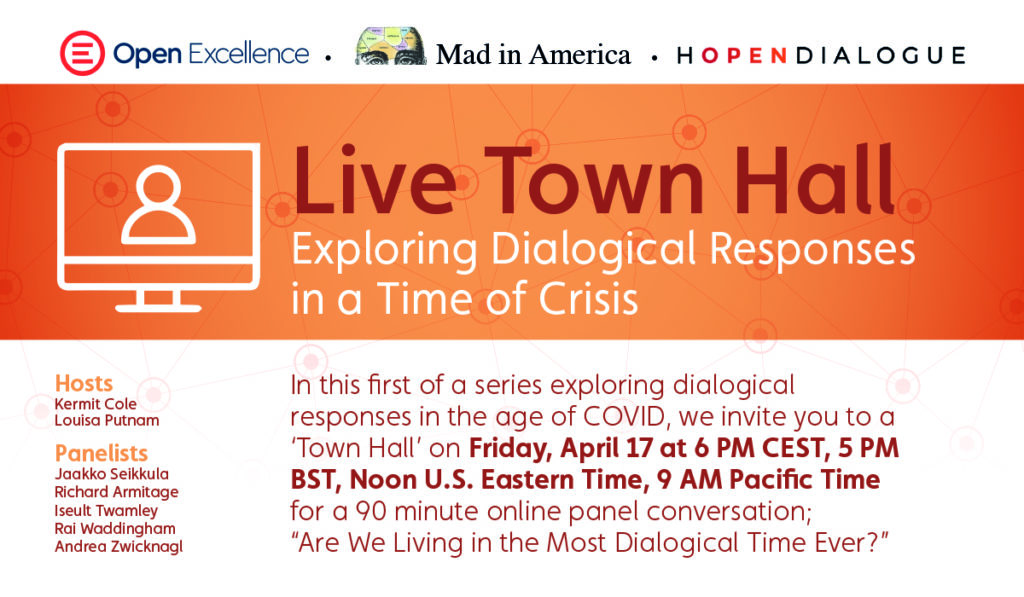

We may now live in the most dialogical time ever, as we are engaged in a global dialogue in which we collectively struggle to find our way into an uncertain future. Mad in America is proud to introduce a new venture; a web series of “Town Hall” conversations, “Exploring Dialogical Responses in a Time of Crisis,” on Fridays at noon, Eastern Daylight Time.

In collaboration with HOPEnDialogue, which seeks to connect and support the Open Dialogue Learning Community, and Open Excellence (formerly the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care), which has been instrumental in funding and promoting Open Dialogue and Hearing Voices practice and research, we will gather to reflect on what they are learning about responding dialogically on the front lines of this crisis. The first live town hall will be held on Friday, April 17. You can register here.

My partner Louisa Putnam and I began our Open Dialogue Foundation training in London four years ago on what turned out to be the day the UK voted for Brexit. What had started with the excitement of gathering with people from nine countries to learn about healing through dialogue turned to sadness as it seemed the world was choosing silence. Two months ago, on our way home from our last class in Helsinki to become Open Dialogue trainers this past February, excited to become part of the network of people around the world working to promote Open Dialogue, signs in the airport cautioned about the coronavirus. Shortly after we arrived home, it was clear we wouldn’t be going anywhere for the foreseeable future.

It became clear in conversations with our train-the-trainers classmates that something new was happening. As the requirement to maintain physical distance became increasingly clear, the need to be in dialogue became ever more clear as well. It may be, in fact, that the principles of Open Dialogue that have been so difficult to implement or have accepted in the world as it was may be more evidently needed—and attainable—than ever before. Where once these principles may have been impractical due to issues of monetization, or ideology, or simply inertia and/or resistance to something new—even with its demonstrated effectiveness—the elements and principles that have been so simple and evidently effective in crises have become increasingly evident to a world in crisis.

Immediate Help

In this new world, untethered to physical offices, many dialogical practitioners are finding they are able to provide “Immediate Response” by phone or online, where once a long wait for an office appointment was the norm.

Social Network Perspective

Families that had not gathered for years in the same room are now open to gathering online. Problems of distance are eliminated, as are inequalities that come with ownership or authority over a physical space.

Flexibility

Many clinicians find that, untethered to physical office visits, “flexibility” to meet clients as needed, as for instance with daily ten-minute check-ins, is a practical reality as well as a necessity. And with this flexibility it becomes easier to divest ourselves of power and authority, as the creators of Open Dialogue have labored to do. We meet with people not in our offices but in their homes, and from our homes. One clinician noted that for some “oppositional” children, the feeling of “seeing a friend online” rather than “going to a doctor” helps to establish a deeper connection. In this new context many clients express care and concern for their therapists in a way that might have seemed “out of place” a month ago.

Dialogue & Polyphony

“Face-to-Face” meeting has taken on an entirely different meaning, as we were asked to keep our bodies first three feet apart, then six, then to wear protective equipment if not to stay away from each other entirely. All participants—including clinicians—now join the dialogue from their own homes, via identical boxes on a screen. Differences of size, height, or strength are eliminated.

People who may have had difficulty looking into each others’ eyes, or tracking the body language in a room, find themselves looking at faces mere inches away, and clustered in an easy-to-manage group. Some practitioners report a welcome ability of groups to spend long periods of time in silences that had previously been awkward. The smallest movements, the softest murmurs—also a part of dialogicity—take on weight and significance across a physical void that we might have missed or recoiled from in person.

Tolerating Uncertainty

One of the most essential elements of Open Dialogue, “Tolerating Uncertainty,” is also famously the hardest to learn in a world that presumes to offer ready answers for fear and suffering. Now, in a world where people who may have the virus are told to stay at home, often alone, with no more than a daily call from the hospital to check on symptoms, the support of dialogical clinicians who are accustomed to holding space rather than “fixing” is more relevant than ever. Some support families who are unable to be with ailing loved ones, sometimes never to see them—or even their bodies—again. They report finding that they are grateful for all the time spent learning to tolerate uncertainty.

“Welcome to MY World!”

Many who have lived isolated, often in fear, now express feeling less alone. Jaakko Seikkula noted in a Facebook post titled “The Most Dialogical Time Ever?” that “some people who had been suffering from mental health crisis have said that they feel they are becoming closer to ‘normal’ people because we all are suffering now … There is nothing to be enjoyed in this terrible disaster. But the only option, and perhaps the best opportunity, is to learn to live together in the uncertainty.”

Peer-Supported Open Dialogue trainer Russel Razzaque responded in a comment that “The very notion of certainty about anything at all will, I hope, be relegated in many respects to the realm of fiction where it always belonged. And whatever change beyond that emerges, I agree that dialogue will be at its heart.”

Responsibility: The Virus as Metaphor

Perhaps most importantly, the principle of “Responsibility,” honoring the relationships we take on with people in crisis, applies to all of us now. The virus has made starkly evident that we are all responsible for each other’s welfare, as in the world of coronavirus nobody’s well-being is independent of anyone else’s. The virus is perhaps a metaphor for what dialogical practitioners have long known about mental health: that what manifests as “illness” in one person is often representative of invisible threats that affect all of us. Our ability to listen and respond to the most vulnerable among us is essential to our collective well-being.

This is the beginning of what will hopefully become an ever-renewing dialogue, as it is the nature of true dialogue to be; not a search for answers, but a search for new ways of being together. The world will try to go back to what it was before, but it will not be able to. It is up to us what it will become. We seek to inspire and encourage individuals, families, communities, nations, and the world to take this opportunity learn from this moment, and then work together to face an uncertain future, becoming ever more human—ever more dialogical—in the process.

This Friday we will meet with Jaakko Seikkula, a co-founder of Open Dialogue, Rai Waddingham, an Open Dialogue and Hearing Voices trainer and practitioner, Iseult Twamley, and Open Dialogue trainer and practitioner, Andrea Zwicknagl, a peer support worker practicing Open Dialogue and advisory board member of HOPEnDialogue, and Richard Armitage, a dialogical practitioner. Next week we will host Russell Razzaque and Jimmy Ciliberto on a panel focusing on the responses in Italy and the UK.

“The virus is perhaps a metaphor for what dialogical practitioners have long known about mental health: that what manifests as “illness” in one person is often representative of invisible threats that affect all of us. Our ability to listen and respond to the most vulnerable among us is essential to our collective well-being.”

Kermit, that is beautiful and simply true and ties in so perfectly with tolerating uncertainty, which is so difficult.

And well, if we fail and lack of certainty causes distress, that is okay too. Just another thing to try and tolerate 🙂

Report comment

I differ. Analogizing viruses and emotions is the same sort of tired metaphor that led to concepts such as “mental illness.” (See my comment to Enrico Gnaulati, PhD.)

Report comment

I had one problem with it but I was tired of being a big party pooper.

I was having trouble with the word “manifests”, as “illness”.

I am detecting “manifests”, sounds very akin to “diagnosis”, as if it is understood by “manifestation”. Having trouble expressing what I mean.

I figured that Kermit most likely never meant that, and I notice that for some it seems to be difficult to steer away from an overused language.

Perhaps we need a linguist 🙂 I know I could use one.

Report comment

We definitely need some movement linguists. Even Chomsky has proven disappointing when it comes to “mental health.”

Report comment

At least he acknowledges it to be a metaphor. Unlike mainstream psychiatry.

Report comment

My point is that “mental health” aficionados are not generally the sharpest tools in the shed and cannot be trusted to discern between the two. If he were writing about carpentry or climate change it might be different.

Report comment

Very exciting. Count me in! You correctly state: “inequalities that come with ownership or authority over a physical space”

Recently, like many, I have been attending more than the usual number of Zoom meetings because its the only way for most people to meet right now. Since Coronavirus, most of the meetings have been characterized by by a sense of relief not just because people are more ready to let the veneer of professionalism drop a tad bit, after all we are supposedly in this crisis together, so people are uncommonly ready to talk about their struggles and make themselves uncharacteristically vulnerable. Seeing everyone in there home environments can have the effect of being an ‘equalizer’ when people feel more empowered in their home environments.

For survivors of forced drugging and institutionalization, the prospect of going voluntarily to a clinic for a simple med check, can be a daunting experience, even after decades of living peaceably in the community outside of an institution. Even attending a hearing voices support group can be challenging, depending on one’s past experiences.

Acquiring the etiquette of an online town hall meeting will have a learning curve but for many, it could be a way to gain trust in community again and reintegrate.

I just hope that the facilitators will make a place for people in altered states or whose boundaries need work. People who are cognitively impaired or whose personality was altered by state sanctioned torture are often said to be in a state of ‘decompensation’ or extreme disorganization’ or to have a ‘personality disorder.’ This leads to discrimination and they cannot practice reintegration, even in the very meetings that purport to exist for their benefit!

Their failure to communicate ‘normally’ is often used against them. They may be banned, furthering their frustration and isolation.

I hope that there will be a dedication to including all voices using the principles you cite.

Report comment

Thank you for naming this reality madmom. When I was on social media I was called out aggressively by a fellow survivor. I asked if we could speak one on one with our voices instead of writing knowing my own challenges to be understood. It turns out she was furious but also lacked the ability to slow her reactions due to a TBI. Once we talked and I understood we were able to adapt. She didn’t scare me anymore. Our world rewards those who have the ability to hide and punishes those who don’t. You named the difficulties so clearly. How many survivors don’t have trauma compounded with brain injury and neurological difference? We need dialogue more than ever. Places to grow with feedback and accommodation rather than

the all too common assumption of ill-intent and excommunication from yet another space, or more painfully, being ghosted without ever knowing why.

Report comment

Being ‘ghosted’ is useful term. It aptly describes how society treats many of us who seeking justice or a modicum of understanding for past harm to ourselves or a loved one.

I had a friend once complain that when we got together, I appeared t be obsessed over my daughter. I’ve heard the same thing reality for grieving family members who are told to ‘get on with their lives.’ At the time she made this complaint, my daughter was constantly under siege by the mental health system and once, she came within inches of losing her life to overmedication while being institutionalized against her will. Had my daughter been kidnapped in a foreign country by terrorists and held hostage for years and years, if under those circumstance I and my husband had to track our daughter down and come up with a hefty ransom and work through the embassy to get her back, I’m sure my friend would have drawn a different conclusion about my so-called ‘obsession’ People are not prepared to accept some people’s pain.

I honor you O.O. for the honesty with which you describe your social situation challenges and I hope that you will participate in many future town hall meetings

Report comment

The Ghosts of the Civil Dead.

And the thing about getting your daughter back from terrorists in a foreign land madmom is that they can’t simply call police and have her ‘recaptured’, and nobody is calling what they do ‘medicine’.

I know i’ve been ‘ghosted’ by my community. I get tortured and kidnapped, get the proof that is what was done, and they simply don’t like that truth, so ignore my complaint.

I wonder how many fraudulent documents are being distributed to lawyers to conceal the vile abuses being concealed as ‘medicine’. That fact MUST be ignored by my government, their primary weapon being the trust people place in Doctors and Lawyers. And of course once they start threatening your family? What then?

Police tell me that a complaint regarding torture and kidnapping the process is they send an email that you never receive and after two weeks thats the end of the matter. With regards the threatening of your family, they didn’t receive a complant from the people who were threatened so nothing to see there. And the police officers present while I was tortured? The eye witnesses? The term used in the Convention is “acquiesce”, which is precisely how they are enabling the use of known torture methods, and then bringing the victims under the powers of the Mental Health Act to conceal their human rights abuses.

Not a soul prepared to even look at the documents I have objectively. Or those that have saw an opportunity and took it.

“They will take their oaths as a cover”

I mean consider. Even if we put aside the fact that I was ‘spiked’ and had a knife planted on me (ie the conspiring) what do I have? Police and a Community Nurse turn up at my home knowing I have been spiked with benzos. Police ‘detain’ me as a result of the weapon, and make immediate referral to the Community Nurse who then authorises the ‘spiking’? He then interrogates me, verbals me up to be ‘treated’ in his locked cage, and then hands me over to police for interrogation. This whole time I’ve not been informed, and the duty of care these people have to me is ignored because they are busy torturing me?

And lawyers, advocates, and literally everybody seems to agree that this is fine? Would it be fine in the US? The UK? Have police found a method of drugging suspects before subjecting them to interrogations for 7 hours? Is mental health services assisting in those torture methods? Our police here are notoriously corrupt but I had no idea that our Politicians were authorising this, and I have written proof of that. Maybe we’re just the Lucky Country? Lucky police get to torture anyone they like, and any problems Doc will fix it up with an O.D. in the Emergency Dept?

I guess the government is relying on y’all staying silent, and making it easy to slander me (ghost) and not check the facts. Isn’t that how they are calling this system of abuse ‘medicine’?

Acquiesce? It’s a word that needs to be applied to these so called ‘advocates’ as far as i’m concerned. Reform? How about we at least try and stop the killings and use of torture?

And don’t for a minute give me the “oh the officers didn’t know what they were doing was torture”, the State has a duty to train them in what does and does not constitue torture. Fuking destroy anyone who complains and we’re good to go.

Report comment

There is nothing wrong with Chomsky unlike many others he has kept the faith. I first read chomsky as a smallchild in a cold northern library in a bleak and desolate place . Kermit cole thank you for reminding us all of our hopeless desolation.

Mad mom agree with you and your hopes completely . Keep the faith

Report comment

I WANTED to vreate and post my own blog here, but I cannot find the way to do so?? SO I will have to do it this way:

THIS COVID-19 PANDEMIC IS A ‘LIVE EXERCISE HOAX!!!:

I am amazed that people who have known about the mental illness myth, and/or are victims of it seem not aware of just how evil and pernicious and manipulatind the powers behind this so-called pandemic are. YES it is a very same mindset that has been targetting millions of people, including children and evn babies with having ‘mental illness’ and needing ‘treatment’ in the form of drugs and/or ECT. Now THAT is medical fascism and abuse is it not? IE people who find themselves sectioned/in lockdown di not have any human rights and can be forcibly drugged. Now my question is: does anyone see a connection between THAT abuse of human rights and what this ‘COVID-19’ is all about, and its agenda? Can you not see, connections, patterns, because I will show them to you.

For one it is a PLANdemic. It has all been carefully planned. You need to research ‘Lockstep’ which was connected with who esle but the Rockefeller family in 2010 planning simulation of a pandemic which ‘coincidentally’ sounds extremely similar to what we have been and continue to go through. Then about two months before this so-called COVID-19 pandemic, there was an even called EVENT 201 funded by none other than the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation ALL ABOUT a …yeah, a pandemic happening, and everything happening ‘miraculously’ was acted out in that. So if it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck….

Please understand that mainstream media is not your friend. it has for decades lied to you/us getting people to accept war, etc etc. And it is lying to you now. The medical mafia CDC has openly admitted that it is rigging the numbers of those suppsedly having ‘COVID-19’. Please hear what I just said!!

Although the 24/7 news propaganda-on-teroids is claiming hospitcals are ‘war cones’, independent citizen journalists have actually made the effort to go to the hospitals, and find they are note like …well empty, dead, and there are ambulance and staff just hanging around, the staff playing video games on their smart phones. It is a SCAM. You need to look WAY from that screen on the wall pumping out ‘The News’ and use critical thinking checking out other sources. Understand that the min players behind this unprecendented global scam gain to add millions to their millions, however little independent journalists, always threatened with being censored (and BEING so) from Youtube etc are doing it for us, you, the people like them!!! yet THEY get called over and over ‘conspiracy theorists..

I have a video where a doctor exposes how they have been told to rig the numbers of COVID deaths, and yet people like him also are called conspiracy theorists by people like Dr Fauci. WAKE UP!

So what is their agenda doing this? it is to more and more control us. To get us digitally impregrnated so they can track us and control us under the pretense they care about people’s health!! Can people at Mad in America not see/get/understand that the oppressive power the controllers have waged over those labelled ‘mentally ill’ is now graiadening out to include more and more/ALL of us? trying to make it mandatory for ALL of us to take their vaccination which will include devices. I am not making this up!

Bill Gates ID 2020 – PLANdemic COVID Tyranny

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EIWfhZAhk3Y

Report comment

Are you sure your not making this up Juliano?

But you do have a point. I know that they have passed laws here fairly quietly that will make mandatory tracking devices easier to attach to ‘citizens’, police are now openly admitting to using phones as tracking devices, and they are now using drones openly to ensure people don’t gather in groups of three or more. I don’t know if they are loaded with Hellfire missiles like they are in Pakistan where going to weddings can be quite a dangerous exercise but ….. maybe a burst of 50mm might stop people enjoying the beach lol. I’m sure it will be AFTER the crisis that people will slowly become aware of the rights and privileges they have lost while they were busy not getting sick and dying. Haha (in the style of Nelson Muntz), we’re not all in it together now.

I guess my government is regretting removing s. 54 (b) from our Criminal Code which meant that it was illegal for three or more people to gather in a public place without a permit from the State. That of course was removed as a result of it being “Unconstitutional” (after 11 years of using it). Not unlike our police raiding journalists with invalid search warrants but not destroying the evidence they have gathered on the whistleblowers. Its easy to break the law when your the one who decides their will be no consequences for that breach.

Good news about my country is that according to the definition of mental illness contained in the Mental Health Act the whole country is mentally ill anyway. We can’t get any sicker. I suppose technically if someone were to make an appeal to the High Court regarding the laws that have been passed by people unfit to pass wind they might realise the insanity of what they are actually doing.

Report comment

I wish I were making it up. What has happened and continues to is the most insane sh*t I have ever experienced or even known of in history, and that’s saying something! The bottom line is they are wanting everyone tested, and digitally monitored for ultimate control. Similar to what is happening in China, and worse. So we have to take all this very seriously while we can still resist this insanity. This video is also extremely interesting because it goes into the psychological history of all this, and how it was planned a long time ago: Covid19 – Psychological Warfare

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTmPDfzFp10

Report comment

I posted this quote in another article just recently but, to save having to look for it I’ll repost here. It’s from one of my favorite books, the Hagakure (which I am currently rereading).

“There is something to be learned from a rainstorm. When meeting with a sudden shower, you try not to get wet and run quickly along the road. But doing such things as passing under the eaves of houses, you still get wet. When you are resolved from the beginning, you will not be perplexed, though you still get the same soaking. This understanding extends to everything.”

There is something to be learned from a virus …….

We can’t resist the insanity (it’s out of our control), we must resolve ourselves to getting wet and not being perplexed, especially if we survive. The mad and insane are the people running around trying to garner support with statements like “we’re all in this together”. I accept no responsibility for the evil deeds inflicted on others by some, and I am in no way going to be held responsible for those deeds on the Day of Judgement. “Your on your own” backstabbers and hypocrites.

Though I guess my attitude was hardened when confronted in an ED with a doctor who was going to murder me, and my whole community turned a blind eye, nay were quite prepared to restrain me while he did it (though they may have been of the belief that what he was doing was ‘chemically restraining’ and would be confused about the unexplained death).

And the Ass saw the Angel.

Report comment

Well Juliano, I’m thinking I’m not much of a “conspiracy” type, and as far as Covid-19 (I hate the term), I doubt whether most of mankind has a brain to ever “plan” anything properly. I think man is a devious creature by design, however, it is rather random and selfish.

YET, you are most likely correct of your assumptions or views, because what most of society suffers from is fall out,

I see NOTHING “good” coming from another botched “cry wolf” BS “horrible world event”.

I see it happening, people are ditching common sense everywhere, from those who pay no attention to those who “isolate” in the extreme sense.

It will definitely lead to a negative fall out, and that fall out does not lead to a “safer” environment. In fact anything but.

The media loves it, people gobble like vultures at a carcass.

Ohh and the pickings are right for “mental illness”, you know, that biomedical one, and we can now deliver proper diagnosis from armchair, WHICH was never okay before.

I think though, as long as we can SEE the faces, or hear the words, we can “accurately” “diagnose”.

Well I’m ditching my phone and computer and moving to the bush where certain plants grow. lol

Report comment

“Ohh and the pickings are right for “mental illness”, you know, that biomedical one, and we can now deliver proper diagnosis from armchair, WHICH was never okay before.”

Sam I’d almost forgotten about ‘remotes’. They’ve been wanting this ability for some time now. Arbitrary detentions are of course a sign of a totalitarian Police State but ….. if we call it medicine we can, as has been done with the use of torture methods, conceal it.

And the suckers are lining up at their ‘compromised’ computer screens as a result of the ‘stress’ knowing that their confidentiality amounts to zero. Not only are multiple governments ‘collecting data’ from their communications, but any hack who knows how to instal the most basic keylogger etc. Mind you the confidentiality provided by our laws (Privacy Act) basically amounts to nothing when the government is the one fuking destroying people. They released a whole bunch of misleading and fraudulent documents about me to lawyers and have been slandering me for 9 years now. I’m sure at some point (possibly election time) this will be brought to peoples attention that they have been uttering in this manner. But for now ……

The clause in the Mental Health Act states that the “mental health practitioner” must have personally examined the victim within the last 48 hours, and it is unlawful to detain otherwise. Careful who you answer your phone to, because if they permit the use of video/phone chats then all they would need to prove to have people detained would be an answered phone call.

That’s going to be really useful when doctor want someone ‘treated’ for whatever reason. They used to have to go to the trouble of ‘spiking’ people with benzos and planting a knife on them for police to find after they lied to police and made the claim that the victim was a “mental patient” and they were doing this to protect the person from doing damage to their reputation. Now they just call you and then send police to detain and transport. Knock knock. “Honey, it’s the Einsattsgruppen for you”. Just kidding, they don’t knock and prefer to jump you while your asleep.

See that? They honestly believe that dragging people from their homes and informing neighbors that they are having police take them to a locked mental institution does NO damage to the persons reputation. I’m sure they must be taking these intoxicating stupefying drugs themselves to not be able to see the damage and harm they do to people. Its one explanation at least.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2A262DPeR34

Nah. it’d never happen here right?

Report comment

Your instincts are serving you well Juliano. It will be a while before we figure out exactly what’s really going on, but meanwhile be VERY SUSPICIOUS. Especially when the Gates Foundation is involved.

Report comment

Thanks oldhead! I had the instinct not to get a mobile phone from the first, and when I began to see more and more people, all types and age groups, looking like zombies on their phones everywhere, even in the most wonderful places, even with their dogs and little children, when they shoulda been part OF that experience, I decided I never want one of those fukin things. I do have a computer, but it isn’t WIFI. I also have tried to avoid that too. NEXT breath you see they – the technocrats – want to irradiate the whole planet with 5G !!!!

THIS, what I call a PLAN/SCAM demic is very part of their eagerness to roll out 5G. It all comes together if you research the larger context of what’s going on. The extraordinarily insane Bill Gates wants every one on planet Earth vaccinated, and if you look at ID2020 you see that along with that is the design to get everyone digitally chipped so they can get complete control of everyone, and the 5G will be the infrastructure for their sick dystopian agenda. So all the ‘mad people’ of the past, called ‘schizophrenics’ etc telling others the government is spying on them. They are more like prophets and/or SEEING and FEELING what is ACTUALLY going on, all along!!! They have two common terms they weaponize for people who see and warn about such as that, ‘mentally ill’, and ‘conspiracy theorist’!

China Flu = Vaccine/Chip. Will you accept the NWO Beast System? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lf0SrFCbi-k

Report comment

So where did you come from out of the blue? 🙂

Your well articulated “paranoia” resonates with me and probably has others regarding you as a crazy crazy.

I have heard claims that 5G helps activate the virus when it’s turned on. I’m in no position to judge this one way or another. But I strongly believe a big part of this “crisis” is an attempt to terrorize people into being “vaccinated,” as they clearly see us as livestock.

Report comment

https://www.msn.com/en-ca/news/canada/bc-father-ordered-to-give-inhaler-to-child-he-believes-doesnt-have-asthma/ar-BB12YYJz?ocid=spartanntp

I am not surprised to see this event take place and even though it has nothing to do with covid, it is subliminally incorporated. It will definitely have effects and negatively so.

If people decide to have children now, it is a crapshoot, if they will become part of the “manipulated” and controlled, or be part of the controllers.

Call me craycray

Report comment

julianno

It is interesting that the 900 page bailout could be written in a matter of days, WOW, Mitch McMconnell and Pelosi must have been up all night writing it. Working hard to make our lives better.

Jim

Report comment

Responding to madmom’s insight that aspiring to be a Town Hall will require patience from us all, as we are on “a learning curve.” I will confess, I am not learned in Town Hall etiquette but, as Kermit said to me this sunny, snowy morning, we ”feel fortunate and blessed to have met these estimable people and to have the opportunity to invite them to our virtual table and hear their dialogue.”

Bear with us please, dear Sam, oldman and madmom and other contributors.

My brain is still a scramble from years of terror walking beside my son into madness and the biomedical and not so humane response. My “tool” is admittedly not so sharp. Help us out with your wisdom and experience, as you are doing in your comments.

Perhaps “MWE” all do our best to speak and offer what we can and invariably make lesser and also terrible mistakes. Let the hive make honey together.

Rumi’s

Last night I dreamt,

Oh Marvelous Error!

that there were honey bees in my heart,

making honey,

from my past mistakes.

I am from a small town in NH but we didn’t have town meetings. Close by in Nelson, they held these forums in their Town Hall. I remember the ethos of everyone’s voices being heard and the meetings going on and on and on.

Currently we are planning on a half hour of opening the conversation up to the attendees’ reflections, questions and comments, at the end of the panelists’ conversation amongst themselves. As we see how this Friday’s gathering unfolds, the form will evolve. At present, Some of these written reflections, questions and comments from the attendees will be read aloud by Kermit and me and responded to by the panel. The thought behind this is, as best we can, to make space to respond to as many voices as possible. Perhaps in the future we will use the Zoom function to break into small groups for discussions and report back. Your feedback is important so let us know how you feel about this first gathering and your suggestions going forward.

Your words, madmom, “… it could be a way to gain trust in community again and reintegrate.” ring in me. I think of Gheel in Belgium. People came there for the waters, to be healed and then families took them in. may the world follow their compassionate lead.

If a hundred people offer their voices on Friday, we will sadly, only, in a half hour, be able to respond to a few.

Report comment

Thank you Louisa so much for your idea to do this so hope it goes forward

Report comment

Dear Louisa,

I’m deeply sorry for your pain and terror. I understand a little as my wife and I walked into hell together…and yet we were able to find our way back out…together. But it still takes a toll as you know. And my brain is also in a scramble. But if you’d ever like to talk, your SO knows how to find me.

Sam

Report comment

If the stated goal of all this “dialogical” talk is not to end psychiatry the only “logic” which will prevail is that which supports the continued existence of psychiatry and its related professions (including “MIA Author”).

Report comment

I agree OH.

But then, I see myself as an educator, as much as any author on MIA. And learning is ongoing.

People who are “therapists” are as much in need of ongoing education, as anyone. I think it’s terribly difficult

for “therapists” to pave their own path.

I do know that if I had been a “therapist”, that is one title I could not list on my website, in all honesty. Life is rather diverse and we really need to be aware of how much we need the needy.

I rather enjoyed the people, and enjoyed the “chat” section. I felt I “knew”, or was “meeting” people. I was aware of my stance entering the door, and so do the panelists.

Report comment

But in the end everyone agreed that psychiatry must go, right? 🙂

Report comment

🙂 I think so, although we did not go there. I think it was about keeping on topic. Goodness knows how wild a crowd it could be.

I find myself raising subjects that really have no place in our civil society, you know, when people might look elsewhere, or try to change the conversation?

So there are a few places I actually try to control myself lol.

Report comment

we did not go there. I think it was about keeping on topic

And what was the topic?

Report comment

OH

“what was the topic?”

Good question. There were two going on. The “dialogue”, which is it’s own topic, but I rather enjoy listening to others talk, as long as it’s not pro-psychiatry or about “mental illness” and I particularly get turned off when “dialogue” turns into a round about way of discussing “MI”, or “unusual” responses.

There were in fact two “dialogues” going on, which I rather enjoyed, the chat and the panelists.

And the chat part would not have happened without the town hall meeting 🙂

I think meetings are great for that, you get drawn to certain people, people chatter and it’s a supportive environment.

Report comment

“what manifests as ‘illness’ in one person is often representative of invisible threats that affect all of us.” As one who was misdiagnosed, due to distress caused by 9/11/2001. Unbeknownst to me at the time, because most “mental health” workers had gone off believing the delusion that “all distress is caused by chemical imbalances” in individuals’ brains. I agree, there are visible and “invisible threats that affect all of us.” But being cognizant of those “threats,” when the “mental health” workers weren’t, wasn’t actually an “illness.” Neither was distress caused by 9/11/2001.

“This is the beginning of what will hopefully become an ever-renewing dialogue, as it is the nature of true dialogue to be; not a search for answers” – nor a search for “the right diagnosis” in a debunked DSM “bible” – “but a search for new ways of being together.” It should always have been about dialoguing, including listening to one another, in a mutually respectful manner.

Thanks for your thoughts, Kermit. And, hey, we could be related because there are Cole’s in my family’s genealogy. As a matter of fact, I have a child named Cole, excellent name.

Report comment

I did join in this OD webinar.

Parts of me never trusts the “helpers” anymore…I rather went for one, curious. And two, to be part of something.

I was moved, and even though I could poop on just about anything to do with “mental health”, I refused to see it as such.

I decided to see it for that moment, for what it meant to me. To see people connecting. There was a broad sense of sameness and I enjoyed the chat of viewers also.

So thanks Robert Whitaker, and panelists.

Report comment

Thank you Sam I cried almost all the way thru

Report comment

The only thing I can say, is that IF the Country wants to move back into Full Production regardless of the Corona Virus and the amount of people that ‘Might / or Might Not’ DIE as a result – is that there is an effective International PRECEDENT in Covering Up deaths in Mental Health, and this could be UTILIZED.

We’ve already seen a bit of this in the UK with thousands of people dying in Care Homes and not being accounted for.

Report comment

MIstake on my part

The stanza I quoted was from a poem by a Spanish poet, Antonio Machado, from the poem, Last Night I Dreamt.

Thank you for your comments and reflections. We hope to have another Town Hall in three weeks if all goes well.

Report comment

Just watched the pod cast first time in ten years I have felt connected to a community of people who care. Key question for me “can home healing be enough.. It can’t if everyone in that home is also broken.. Which we are thank you so much to all of the panel so much appreciated much love to all

Report comment