In a chapter titled “Gender, Depression, and Emotion: Arguing for a De-colonized Psychology,” scholar-activist Bhargavi Davar investigates how narrow conceptions of emotions in the West have led to the medicalization of depression, the imposition of ineffective approaches to mental health throughout the Global South, and the pathologization of women’s experiences worldwide.

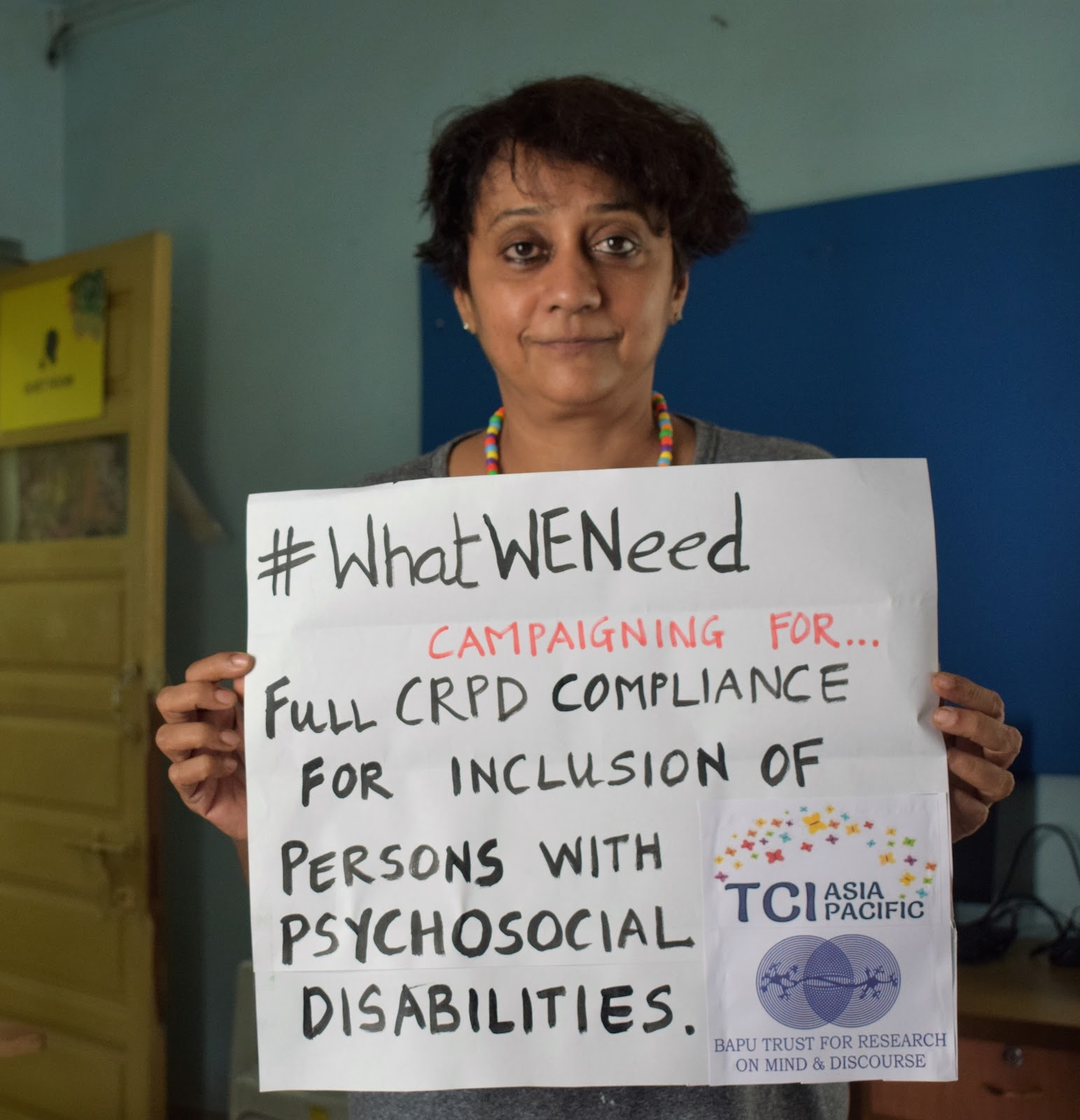

Davar is a philosopher and social science researcher as well as a psychosocial disability activist. She is an international trainer in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), an editor for Mad in Asia-Pacific, and the founder of the Bapu Trust for Research on Mind and Discourse in Pune, India.

Bapu Trust aims to give visibility to user/survivor-centered mental health advocacy and studies traditional healing systems in India. Published in a new book Gender and Mental Health: Combining Theory and Practice, Davar’s chapter demands a more inclusive understanding of emotion, and consequently, depression.

Depression remains one of the most commonly diagnosed ‘mental disorders’ in the United States, and the first line of treatment is antidepressants. There are significant criticisms that have pointed to the severe and debilitating long-term withdrawal effects, and the dubious ineffectiveness of these treatments, yet they remain popular.

In the last two decades, psychiatric intervention has crossed national and cultural boundaries through the rise of the Global Mental Health Movement, which insists that the Global South needs immediate access to psychiatric care. The availability of psychotropic drugs is considered essential to this treatment despite critics vehemently arguing the legitimacy of this “treatment gap,” and the validity of using universal psychiatric labels cross-culturally.

Bapu Trust in India is one such site of resistance, which has repeatedly fought against culturally insensitive and physically intrusive approaches. India has a long history of psychiatric interventions built from the time of the 200-year long British colonial rule. Most of these interventions are not responsive to the realities of life in India, such as caste discriminations, gender dynamics, and local healing practices.

In this book chapter, Davar argues that psychological understandings of emotions are premised upon Western values and ethics. Thus, they are often useless or even harmful, especially when used for interventions in the Global South. She suggests that emotions should not be viewed as primitive responses to pressing issues, but rather as important and useful ones.

She particularly points to depression, which, while understood as an emotional (mood) issue, is still treated as a physiological one. To this end, she seeks to overturn three colonial claims about emotion: emotion is universal, individual, and mental (exists inside us). Instead, she insists that emotion is local (specific to certain areas), communal (not at all internal but a shared external experience), and embodied.

In response to criticisms of the Global Mental Health Movement, many psychiatrists have acknowledged that depression is connected to socio-economic factors (poverty, domestic violence, disadvantage at work, etc.). But Davar insists that they still fail to treat it as a socio-economic problem and instead revert to “chemical cures (antidepressants), and colonial cures (segregation and restraint).” Others, such as researcher Lisa Cosgrove, have similarly criticized the lip service offered to socio-economic factors while treatments remain strictly physiological.

Davar notes that the psychiatric system has used depression (also hysteria, in the past, and, more recently, PMDD) to dismiss legitimate, external problems of women. Vaginal discharge, ‘genital complaints,’ menstrual issues, chronic fatigue, etc. are all physical maladies that have been used as the basis for the diagnosis of depression in women. The embodied and social nature of women’s emotions and experiences are reduced to psychological language and treated as a pathology.

In other words, these complaints, specifically from women, are recoded as bodily markers of underlying depression. Simultaneously, indigenous healing spaces and practices which used to provide relief, have been secularized and demonized. She writes:

“Depression may not be a state of abject victimhood. But neither is it a state of total agency and empowerment. It is a state where a woman protests her (bodily, social, and spiritual) circumstances…”

The assumptions that Western psychology makes about emotions reveal that they are rooted in Western philosophy and ethics. This includes understanding emotions to be internal, pre-verbal, chaotic, and opposed to reason. In the case of women, emotions are often seen as a failure to reason and as “a dark and dangerous sibling of thought.”

Emotions are commonly understood to be object-oriented—always about something. Different psychological theories still hold similar assumptions about them. For example, cognitive therapy attempts to bring dysfunctional emotions under reason, and existential thought often focuses on their “thereness” and the feeling/purging of the same.

In India, psychoanalysis historically construed people’s emotions as primitive, primary, unconscious, etc. The gendered implications were many—reason was cast as masculine and emotion as feminine in psychological literature; the colonizer was cast as masculine (with reason) and the colonized as feminine (emotional).

These theories often have a looping effect wherein women begin to understand and experience themselves as more emotional. Since emotional expression is itself problematized as pathology, this has significant implications.

These narrow understandings of emotion and the subsequent pathologizing of affect are in direct contrast to the way that emotion is traditionally understood and experienced in India. Davar uses folklore, literature, and myth to exemplify the social, embodied, external, and communal nature of emotion—especially amongst women.

- Kannagi, the female protagonist in Tamil Sangam literature. Kannagi, in response to her husband’s unjust death, destroys a whole city in her grief and rage.

- In Tamil folklore, the ghost of Neeli (weeping soul), who was repeatedly betrayed by her husband (while being supported by her community), was killed by him (as he grew tired of her sadness and weeping). She then seeks justice for all women.

- Sanichari, the lower-caste female protagonist in Rudali, capitalizes on her profession as a griever and monetizes different version of crying.

These women undermine the idea that emotions are weak, useless, and pathological.

Davar insists that, in contrast to Western ideas and psychological theory, Indian understandings and experiences of emotions are not individual, but communal. They are both expressed and experienced at an inter-connected community level with others around as participants. Emotions have a public, contagious, and physical quality to them, and they function to bind people together.

She notes that psychological theories have fostered academic imperialism and played a part in individualizing and medicalizing emotions in the Global South. Other prominent researchers have similarly pointed to Western psychology’s failings and epistemological violence when it comes to theorizing and intervening with a socio-centric rather than an egocentric sense of self.

Davar suggests that, while the West is beginning to pay attention to the role of community in psychology and the role of bodywork in trauma, many non-Western traditions have been doing this for a long time. Spaces such as healing temples or dargahs in India are an example, but these practices have had largely been dismissed and derided by the Movement for Global Mental Health.

She further writes that an emphasis on the verbalization of experience in psychotherapy often leads to a focus on individual differences. Conversely, a focus on embodied and communal interventions attends to group connectedness.

Davar argues that it is essential to expose the colonial legacy of our understandings of emotions and the resultant pathologizing of depression, writing:

“The emotions that underlie depression are those that contribute positively to experiencing sensitivity to our social and spiritual connectedness, to nature and our cherished relationships.”

Davar concludes that Western medicine should integrate more traditional approaches in its treatment and understanding of depression, particularly in allowing for the performance of emotion through shared ritual behavior.

****

Davar, B.V. (2020). Gender, Depression, and Emotion: Arguing for a De-colonized Psychology. In M. Anand (Ed.), Gender and Mental Health: Combining Theory and Practice (pp 19-32). Springer. (Link)

I don’t think there is any question that psychiatry and psychology are paternalistic, to the point of being misogynistic. For goodness sakes, the primary function of both industries is covering up child abuse and rape.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

How much more anti-woman/anti-mother and anti-children can psychiatry and psychology get? But that being the case, I don’t agree that psychologic and psychiatric beliefs “are premised upon Western values and ethics.” Quite the opposite, their systemic child abuse covering up actions show a complete lack of values, ethics, and respect for other human beings. They stigmatize/defame and neurotoxic poison people, what is ethical about that? Nothing, in any culture.

Report comment

When I taught Freshman Psychology after my lecture on depression a student from Nigeria told me that they don’t have depression in his country…at least there is no label like that.

Report comment

They should consider creating one, advertising it and selling a cure DrGaryG.

Consider, when did “stress” enter the psychological language/literature? And what a coincidence that the drugs that cure it appeared at the same time.

Report comment

It doesn’t take long anymore to create the right drugs for the mentical illnesses.

Isn’t science wonderful?

Report comment

Well Gary,

it seems men and women have been unhappy for eons. And the funny thing is, no one got treated for it and despite all the “treatments” in our “medicalized” society, once people are in “care” they often are the same or worse. Yet psychiatry keeps looking for subjects, complaining that people are not getting the “care” they need. They are correct, people are often not getting care, but it is certainly not found within psychiatry unless someone got very lucky.

Report comment

A simple google search of “nigeria depression” turns up a multitude of results regarding depression and suicide in Nigeria. Perhaps the clique the individual came from didn’t have a concept of “depression” or “clinical depression” (as mental health workers call it). But it’s obvious that an extremely low mood would exist in individuals in any country.

BUT. I’m happy that the individual probably doesn’t recognise it through the prism of the mainstream mental health profession. Maybe he/she will find an alternate route, and that’s great.

Report comment

“actions show a complete lack of values, ethics, and respect for other human beings. They stigmatize/defame and neurotoxic poison people, what is ethical about that? Nothing, in any culture.”

Well said SE. Women also often feel guilt, so it is a perfect state to lay on more feelings of inadequacy or failure.

Report comment

“As the ego does not represent the whole psyche, so the Western mind cannot speak for the whole world.”

― James Hillman, Philosophical Intimations

Report comment

Bhargavi has an interesting experience of growing up with her mother committed to a mental institution for many years. This was a British system that was obviously suppressive.

Now she has adopted elements of Critical Theory to point out these weaknesses and advocate for change. She knows of some traditional methods that can be used, and her psychology training probably also informs her. But she doesn’t really have a new vision yet. That’s a weakness of Critical Theory.

I listened to a radio interview with her where she tells a story of something that happened to her brother, I think, about a ghost trapped in a wall. It talked to him and convinced him to let it out! This is somewhat common in India. Can you imagine how many ghosts might be hanging around in a land that has been continuously inhabited by a similar culture for thousands of years?

The West doesn’t appreciate any of that. And now many Asians are getting trained in the West, so they are losing their appreciation for these realities also. I have found a teaching that embraces both Eastern and Western aspects of experience. And that’s what they need in the East. So they can tell the West, “we’re doing just fine, thank you. We don’t need your solutions!” But I fear that most of Asia still looks to the West with great envy. They want what we have, and don’t care (yet) about the consequences. But some do realize that there will be consequences.

Report comment