Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness

Anne Harrington

Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness

Andrew Scull

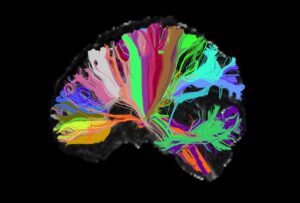

From Boston Review: “In 1990 President George Bush announced that ‘a new era of discovery’ was ‘dawning in brain research.’ Over the next several decades the U.S. government poured billions of dollars into science that promised to revolutionize our understanding of psychiatric disorders, from depression and bipolar disorder to schizophrenia . . . The 1990s, Bush declared, would be remembered as ‘The Decade of the Brain’ . . . While it was impossible to predict exactly what the future would bring, there was an overwhelming sense that psychiatric science was going to crack the ‘mystery’ and ‘wonder’ of this ‘incredible organ,’ as Bush called it.

Looking back as a psychiatrist and historian today, I find that these hopes feel quaint. They remind me of other misplaced visions of technological futures from the twentieth century: flying cars, pills for a whole day’s nutrition . . . Thirty years later we still have no biological tests for psychiatric disorders, and none is in the pipeline. Instead our diagnoses are based on criteria in a book . . . We also have not had any significant breakthroughs in treatment . . . People with serious mental illness today are more likely to be homeless or die prematurely than at any point in the last 150 years, with lifespans that are 10 to 20 years less than the general population . . .

In 2015 the former director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Thomas Insel, crystallized this disillusionment:

I spent 13 years at [NIMH] pushing on the neuroscience and genetics of mental disorders, and when I look back . . . I realize that while . . . I succeeded at getting lots of really cool papers published by cool scientists at fairly large costs—I think $20 billion—I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, improving recovery for the tens of millions of people who have mental illness.

It does not help that academic psychiatry today feels out of touch. Many people have underscored the profound importance of mental health amid the social isolation of [lockdowns], racial violence in our society, and the increasingly hyper-competitive culture of schools, sports, and the market. But academic psychiatry’s almost singular focus on brain-based research has meant that the profession has been largely absent from these conversations. And for what? All the ‘cool papers’ on neurobiology have won academic grants and helped professors get promoted, but they have not meaningfully impacted the . . . care of the millions of people suffering psychic distress.

How did we end up here? If we have failed to understand psychiatric disorders biologically, what happens when we examine them historically? Two recent books by historians explore the crisis in biological psychiatry, tracing the political, economic, social, and professional factors that led psychiatrists to attempt to pin the reality of ‘mental illness’—and the legitimacy of the profession—on the brain. Written by leading historians in the field, these are big books, in heft and scope, that cover two hundred years of the profession’s failures. They reveal that U.S. psychiatry, across its history, has been dangerously susceptible to hype and ‘cool,’ ranging from enthusiasm for brain dissection in the 1890s to the fanfare surrounding neurotransmitters and genetics a century later.

Understanding the undulating history of psychiatric hype and crisis is crucial today as the profession builds toward its next trend: psychedelics, already heralded as a ‘renaissance’ and psychiatry’s ‘next frontier.’ These two histories demonstrate that the academic and corporate pursuit of such hype has neglected the perspectives of communities most affected by psychiatric research and care, resulting in significant psychological and bodily harm. The strengths and limitations of these important books push . . . us to envision a future world where the billions of dollars invested in biological research are instead redistributed to the communities who need it most—in order to provide the resources necessary for radically reimagined forms of care that center whole humans instead of just brains.”

***

Back to Around the Web