Editor’s Note: The following is an original research article by Peter Sterling, Professor of Neuroscience at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. We are presenting it in its native format as a scientific paper. In the paper, he reviews the evidence for the biological models of depression from his perspective as a neuroscientist.

Title: A Neuroscientist Evaluates the Standard Biological Model of Depression

Abstract

Neuroscientists widely hypothesize that “depression” arises from a brain disorder caused by some defect in a specific neural pathway. If so, we might identify and localize the defect, and then develop a rational therapy. However, recent evidence from multiple sources fails to support this hypothesis: (1) Neuroimaging does not identify brain abnormalities in depressed individuals; neuroimaging does not even distinguish between large populations of depressed vs healthy. (2) Genome-wide association studies identify hundreds of variants of small effect, but these do not identify a depressed individual, nor even a depressed population. (3) The “chemical imbalance” theory of depression has failed for want of evidence, thus depriving “antidepressant” drugs of a neuroscientific rationale. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, new analyses of clinical trials indicate rough parity for most participants between drug and placebo. (4) Depression, while weakly predicted by any “biomarker,” is strongly predicted by childhood trauma and chronic social stress. Furthermore, depression is significantly reduced by physical repairs to the community (housing facades and vacant lots) and by psychological repairs through sharing experience of trauma and abuse. Thus, depression—given its lack of any reliable biomarker, its diverse and shape-shifting symptoms, its transience on the scale of human lifetime, and its positive response to renewed hope—would be most fairly characterized as a distressing psychological disturbance rather than as a brain disease or disorder.

Various of my friends and family take drugs for depression and anxiety. Some have confided that they are unhappy with the effects but find it difficult to quit. Wondering if my experience as a neuroscientist1,2 might help, I investigated. I found new insights across many levels: large-scale neuroimaging and genomic studies, longitudinal studies of prevalence, and reviews of clinical trials. Here is my current understanding.

Neuroimaging

Depression is widely claimed to be a distinct disorder at the level of neural circuits—that is, a disruption of neurons, connections, or signals in a specific neural pathway. Were that so, neuroscience might trouble-shoot the circuit and try to repair it. But no example has been found of mental disturbance attributable a disordered neural circuit. Consequently, mental “disorders,” such as depression, are said to be “just like” a neurological disorder—usually “just like” Parkinson’s disease whose cause is certain, a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons, and whose therapy follows from that understanding. “Just like” is a simile, a figure of speech, and what it really expresses is a hypothesis that neuroscience and psychiatry often forget is unproven.

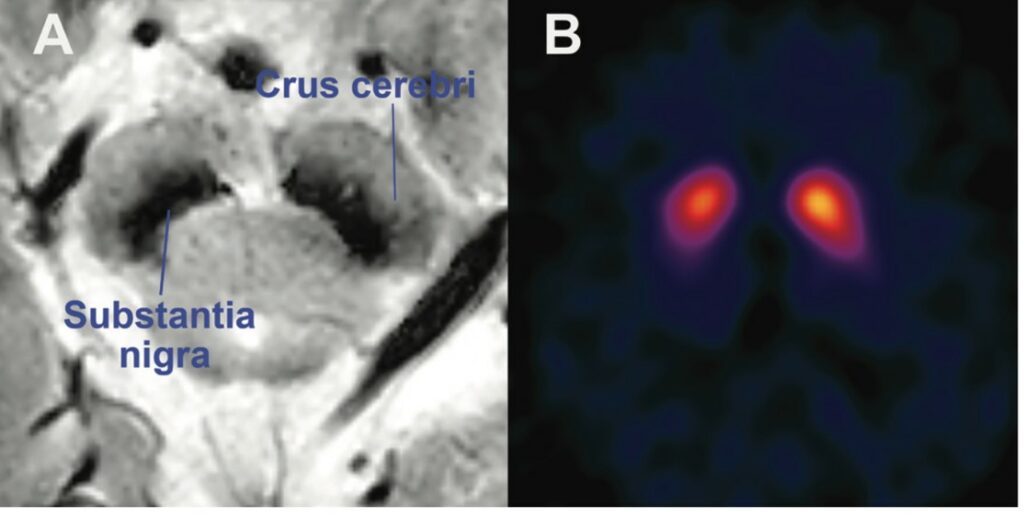

The faulty circuit in Parkinson’s disease can be observed reliably in a single slice of one brain by various modes of structural and functional neuroimaging (Figure 1)3. So, if depression were really “just like” Parkinson’s, it should be identifiable by one of those measures. Indeed, there are long-standing claims of abnormal images from the prefrontal cortex4. More recently, resting-state connectivity imaged in depressed individuals was reported to define four neurophysiological subtypes of depression5. But none of these reports have been subsequently confirmed by larger studies6.

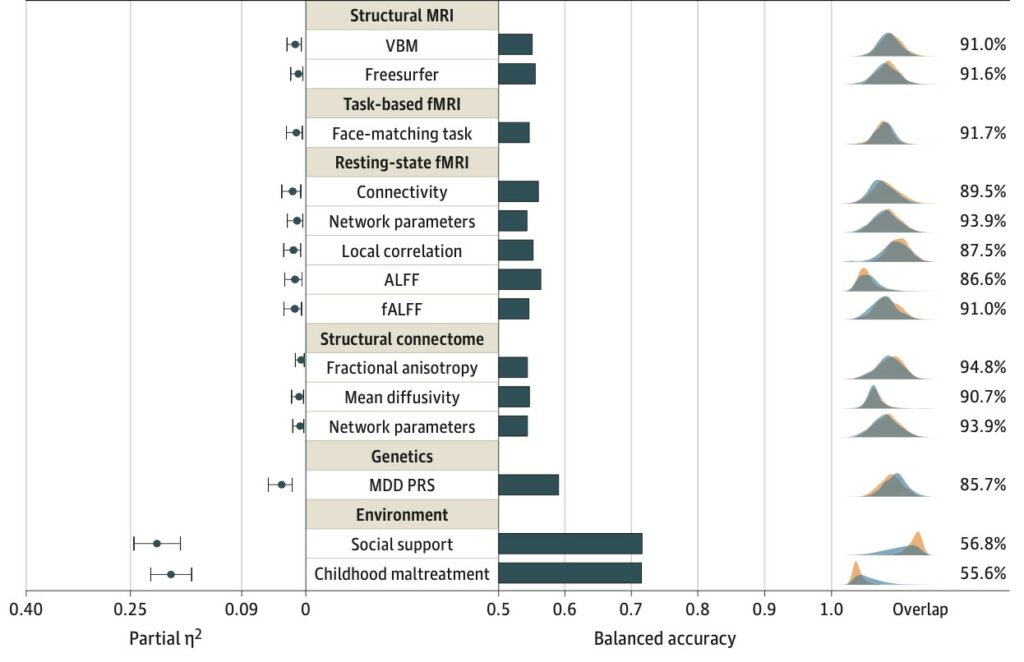

For example, probing for brain abnormalities associated with “major depression,” a recent study pooled data from from 49 research groups in 15 countries7. Differences between depressed and normal groups overlapped extensively on every comparison—nothing like Parkinson’s where the problem is obvious and diagnostic for an individual. However, concerns were raised that brain abnormalities associated with depression might have been obscured by clinical and methodological heterogeneities. So, a new study was undertaken to create a harmonized data set with invariant protocols, quality control, neuroimaging data acquisition, and clinical assessment for a sample of 861 adults diagnosed with “major depressive disorder” and 948 healthy controls8.

This study reported 11 imaging parameters that showed the largest differences between the two groups. Again, the effects were small, with all the distributions overlapping extensively (Figure 2). By these measures the likelihood of correctly identifying an individual as “depressed” or “healthy” fell between 54% and 56%—essentially a coin flip—and acute and chronic depression were the same. The report concluded: “…patients with depression and healthy controls are remarkably similar…regarding neural signatures of common neuroimaging modalities.” The report also considered a twelfth biological measure, “polygenic risk score,” and again found close overlap (Figure 2). Thus, neither the neuroimaging nor genetic associations came anywhere near to localizing a depression-related disturbance in an individual brain, nor even distinguishing a group of depressed brains from a group of healthy ones.

However, two additional measures did separate the two distributions (Figure 2, lower right). Depressed individuals were far more likely to report childhood trauma and far less likely to experience social supports. Many studies find childhood maltreatment strongly associated with long-term risk of depression and anxiety9-11. Maltreated children show earlier onset of psychiatric disorders, which are more likely to be severe and to be associated with greater comorbidity. Also, maltreatment in childhood causes later difficulties in establishing social relationships, leading to smaller social networks—fewer relationships and less frequent contacts.12 In other words, the psychological variable identified in the imaging study as “childhood trauma” causes the subsequent psychological variable, reduced “social support,” and together they predict depression far better than the lower-level neurobiological measures.

The study concluded: “Biological psychiatry should facilitate meaningful outcome measures or predictive approaches to increase the potential for a personalization of the clinical practice.” In plainer language, the study doubles down, calling to continue the neuroimaging search for biological markers of a brain disorder. An editorial commentary, written by an author of the prior imaging study, concurs12. Apparently, they are unwilling to face the implication of their meticulously analyzed findings—that depression, down to the finest accessible levels of neural circuitry, is not “just like Parkinson’s.”

Neuroscientists accept foundationally that the brain represents every distinct thought, feeling, and behavior as some sort of neural ripple: a sad thought must at some level differ from a happy one. But we are very far from identifying such ripples in a human brain, and farther still from understanding how to intervene at that level to shift the balance from a sad ripple to a happy one. Yet, if neuroscientists are unwilling to acknowledge that their hypothesis of depression as a brain disorder currently lacks evidence, they render it unfalsifiable—and thus “just like” religion14.

Genome wide association studies (GWAS)

One great hope for the Human Genome Project around 2003 was to identify key genetic variants that “cause” mental “disorders.” Twin studies had suggested significant heritability, and various “candidate genes” had been reported sporadically for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, but these candidates always proved spurious. As sequencing methods advanced, larger projects were undertaken to discover genes associated with specific “disorders,” initially covering thousands of individual genomes and now millions.

An early report15 found 44 genes associated with major depression. The associations were generally weak, each accounting for only a small proportion of the total heritable component. This study also found an association with father’s age at death (rg= –0.28), perhaps a marker of childhood trauma strongly predictive in the imaging study. This study concluded that “major depression is a brain disorder.” However, one wonders what is meant by this term since the study found that “…major depression is not a discrete entity at any level of analysis.”

The next report16 on genes associated with depression analyzed roughly 250,000 “cases” and 560,000 controls, identifying 102 variants as associated with depression. Again, these associations, although reaching statistical significance, are weak, meaning that the same genes are common in the control population. Sorting individuals as “depressed” or “normal” based on these associations would (as for neuroimaging) do hardly better than a coin flip.

Subsequently, 50,000 subjects from the exome-sequenced UK Biobank were analyzed for genes that would significantly influence the probability of developing a mood disorder resulting in psychiatric referral17. No gene or gene set reached statistical significance, and the author concluded: “It seems unlikely that depression genetics research will implicate specific genes having a substantial impact on the risk of developing psychiatric illness severe enough to merit referral to a specialist until far larger samples become available.” Speaking plainly: not even 50,000 subjects sufficed to identify genes for a mood disorder. The most recent study18 was still larger, several million subjects, and reported still more genomic loci with small effects.

All the positive studies find that the genes weakly associated with depression are modestly enriched in prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex—where affect, cognition, and action finally meet—as if to support the hypothesis. But where else would genes associated with these highest integrative levels be enriched?

As these studies progressed, the genetic variants weakly associated with depression turned out to be also weakly associated with other diagnosed mental “disorders,” including bipolar, ADHD, schizophrenia, and anorexia nervosa. These findings play havoc with the standard diagnoses and suggest a strikingly different view of mental disturbance, perhaps most clearly expressed by Daniel Geschwind in his 2017 talk19 on GWAS at the Allen Institute:

“Psychiatric disorders are syndromes…What we call psychiatric diseases are just levels of impairment…The threshold is not scientific but a clinical/practical threshold for when individuals are unable to function in the world. These syndromic diagnoses are not etiologically defined… just one end of a continuum of normal variability…For most disorders it’s the common variants that move an individual toward that threshold, and sometimes a rare variant can push the person over.”

Geschwind’s conclusion meshes with recent longitudinal studies.

Longitudinal studies

A cohort of more than 1000 individuals in Dunedin, New Zealand was followed from birth to age 45 years20. The cohort spanned a range of socioeconomic backgrounds in a country approaching the US in economic inequality and rates of addiction, suicide, and assault21. Individuals were assessed by neurocognitive examination at age 3, followed by neuropsychological testing during childhood and adulthood. The cohort was assessed for specific mental disorders nine times between ages 11 and 45. Diagnosable mental disorders appeared early and often, 59% by adolescence. Thereafter prevalence grew more gradually such that 86% of the cohort were affected by mid-life.

Most affected individuals experienced more than one disorder. Eighty-five percent of those diagnosed early had accumulated additional comorbid (simultaneously present) diagnoses by mid-life. For example, 70% of those diagnosed with an “internalizing” disorder (depression or anxiety), also experienced “externalizing” disorders (disruptive behavior, substance abuse) or thought disorders (disorganized thoughts, delusional beliefs, hallucinations, obsessions and compulsions). Another 16% suffered multiple categories of internalizing disorder. In other words, most individuals with depression or anxiety eventually suffered from disruptive disorders and/or thought disorders, or various subtypes of depression. Virtually no one, it seems, experiences a single, pure type of disorder. On the other hand, 75% of those with additional diagnoses had them at only one assessment age—indicating that mental disturbances arising across decades, also resolve.

Early mental disturbance presaged more total years of disorder and greater diversity of comorbid disorders. The accumulated disturbances and their eventual chronicity were associated with cognitive decline and premature brain aging quantified from neural images. Greater early trauma increases post-traumatic stress and dissolves social supports. Although individuals adapt allostatically to their life stress, stress wears down both body and brain (see ref 2).

The Dunedin study confirmed a far larger longitudinal study of a Danish population that also found early onset of mental disorder, high lifetime prevalence, and high comorbidity22. Prevalence was somewhat lower, but the Danish study relied on hospital records that would have missed individuals who were untreated or treated by general practitioners. Moreover, compared to New Zealand, Denmark has substantially lower economic inequality, far better child wellbeing, and in correlation, lower prevalence of mental illness23.

Social interventions treat depression

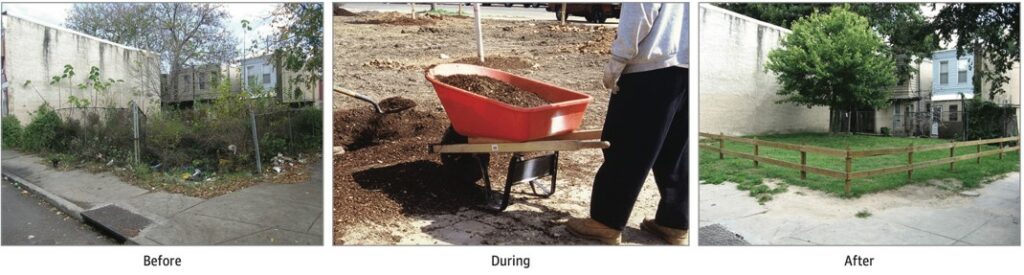

Small improvements to community life have large impacts on mental health. For example, converting vacant lots in poor neighborhoods to green spaces reduced depression by 42% and feelings of worthlessness by 51% (Figure 3)24. Also, repairing the visible facades of homes in poor neighborhoods caused total crime to fall by 22%25. Moreover, the effect was dose-dependent: repairing more houses caused greater reduction. Decreased violent crime in a neighborhood is also associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality26.

To summarize: neuroscience from three perspectives—neuroimaging, neurogenomics, and natural history of diagnosis—suggest that mental depression is nothing like Parkinson’s. All these studies find small effects at the level of neurobiology, but large effects at the level of family and society. Generally, when scientists find many small effects and a few rather large effects, they choose to pursue the large ones. But that is not happening here. Neuroimagers, neurogeneticists, neuropsychiatrists, and neurosurgeons continue to promote their own technologies—despite the solid science indicating the greater value of reducing childhood trauma and enriching social connections27, 28.

Is there a rationale for “antidepressants”?

During my four decades at the University of Pennsylvania, medical students were always told that depression is “just like” diabetes, where “inappropriate” levels of glucose are homeostatically restored by insulin, and “just like” Parkinson’s, where “inappropriate” levels of dopamine are restored by L-dopa29. This familiar simile offered a plausible rationale for “antidepressant” drugs. One could imagine their restoring deficient catecholamines or deficient serotonin. Moreover, since depression caused by childhood trauma might be mediated by a neurotransmitter deficit, this could be a rational fix. But the hypothesis has collapsed30. Depressed and “healthy” brains have not been found to differ in transmitter levels, so there is nothing identified to “restore”.

But maybe we don’t really need a therapeutic rationale. Maybe it only matters that antidepressants work and do no harm. Yet, a systematic review of efficacy with blind raters finds that for most people the drugs do not work better than safer alternatives. Symptomatic improvement with drugs resembles that from alternative treatments, including placebo, psychotherapy, exercise, and acupuncture. The type of treatment matters less than involving the patient in an active therapeutic program31. Diverse therapies yield similar reductions of depressive symptoms probably because of their shared psychological factors—such as establishing new social connections and renewing engagement.

This hypothesis receives significant support from an analysis32 of over 230 controlled trials of antidepressants (including over 73,000 subjects) submitted to the FDA over 37 years (1979-2016). This effort accessed results of individuals, rather than the usually reported aggregated data. The upshot: depressed patients were likely to improve substantially from acute treatment with drug or placebo. The mean drug advantage was small, but some patients benefitted substantially. Thus, possibly substantial benefits for the few (15%) must be weighed against serious risks for the many (85%), including disturbed metabolism (weight gain, with consequent risks of type 2 diabetes and hypertension) and disturbed sexual function (loss of libido, anorgasmia, lack of vaginal lubrication, and erectile dysfunction).

Why should drugs, named for their supposed specificity, as in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), cause such diverse effects? Because when the drugs inhibit reuptake of serotonin into synapses, that is just the start33-35. They also inhibit reuptake of other neurotransmitters, though less strongly, such as norepinephrine, dopamine, and histamine. The SSRIs antagonize the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at its M1 receptor, inhibit synthesis of the neurotransmitter nitric oxide36, increase potency of endogenous opioids at delta opioid receptor37, and allosterically sensitize the receptor for the neuromodulator, brain-derived growth factor (BDNF)38. In short, SSRIs are not specific but rather affect at least eight distinct neurotransmitter/neuromodulator systems distributed throughout the body and brain. Consequently, the drugs perturb such diverse processes as blood clotting, carbohydrate metabolism, inflammatory response, cognition, learning, and memory.

Various distressing effects are caused by pathways entirely unrelated to serotonin or norepinephrine. For example, M1 acetylcholine receptors in hippocampus and cortex are important for cognition and learning—so important that a drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease tries to stimulate M1. So, when an SSRI blocks M1, it might well disturb cognition and learning, although this could be hard to tease out from effects on dozens of other receptors serving the eight neurotransmitter systems. SSRI inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis prevents vascular dilation that drives erection and thus frequently causes impotence.

Antidepressants pose additional risks via their interactions with other widely used drugs. For example, SSRIs combined with a statin (taken by over 40 million US adults) can elevate glucose, which contributes to type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Metabolic effects associated with drug-induced weight gain and type 2 diabetes cause inflammation, which negatively affects cognition. Big Pharma calls these “side effects,” but neuroscientists should know better. We should not be designating as “specific” a molecule whose gazillion effects rattle throughout our whole organism.

Now it is reported that all three types of antidepressant—tricyclics, SSRIs, and ketamine—bind to TRKB, a receptor for the neuropeptide BDNF39. Binding facilitates the effect of endogenous BDNF, and this action is now hypothesized to be the mechanism of their action to elevate mood. BDNF localizes to both sides of synapses all over the brain and affects multiple forms of synaptic plasticity. The report acknowledges that “BDNF can trigger multiple and often contradictory functional consequences based on its mechanism of expression, site of release, and site of action”. Yet the report also notes a search for small molecules to selectively target TRKB.

Here is an opportunity for neuroscientists to pause and reflect. Probably BDNF’s selective activation of TRKB belongs to the brain’s overall design (see ref 1). Would it be so smart, then, especially without an identified pathophysiology, to activate all types of plasticity across the whole brain? Would it be clever to erase a traumatic memory from the human hippocampus, as apparently we can do now in mice? Would that relieve depression, or would it engender a new source of misery: still depressed but unable to recall why? To get this right, neuroscientists should first ask: which are the most appropriate levels to intervene?

Why are antidepressants addictive?

Various websites deny that antidepressants are addictive. Here, for example is the Mayo Clinic40: “Having antidepressant withdrawal symptoms doesn’t mean you’re addicted to an antidepressant. Addiction represents harmful, long-term chemical changes in the brain. It’s characterized by intense cravings, the inability to control your use of a substance, and negative consequences from that substance use. Antidepressants don’t cause these issues.”

Another example41: “Zoloft is not addictive. With addiction, a drug continues to be taken even if it’s causing harm.” But, of course, antidepressants are addictive. Of course, people continue to take them even if they are causing harm. Of course, they are difficult to stop, even with tapering42.

One need only read the ominous warnings about stopping: “To minimize the risk of antidepressant withdrawal, talk with your doctor before you stop taking an antidepressant. Your doctor may recommend that you gradually reduce the dose of your antidepressant for several weeks or more to allow your body to adapt to the absence of the medication.”

And: “Because stopping Zoloft can cause discontinuation syndrome, it’s very important that you don’t suddenly stop taking Zoloft. Instead, you and your medical professional will work together to lower your dosage slowly over time. If you’re interested in stopping Zoloft, it’s advised that you speak with your medical professional. They can help plan a drug taper that’s specific to you and your dosage. It’s important to not stop taking Zoloft without first speaking with your medical professional.” Not addictive—just don’t stop it!

The neuroscience of withdrawal was outlined clearly in 199643 by two leaders in biological psychiatry, who explained that drugs of abuse alter cascades of gene expression, synaptic plasticity, and connectivity—to which the brain stably adapts. They applied the same model to antidepressant drugs, which also provoke widespread adaptive responses, and thus explained simply why “tapering” from an antidepressant can be difficult—it is just like tapering from cocaine or heroin:

“During a cocaine binge target neurons would be bombarded by far more dopamine over a longer period than would be expected for any non-pharmacological stimulus. The result of these types of repeated perturbations is to usurp normal homeostatic mechanisms within neurons, thereby producing adaptations that lead to substantial and long-lasting alterations. In the case of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs, these adaptions are therapeutic; in the case of drugs of abuse, the result is addiction.” [Edited for brevity.]

Neuroscience distinguishes short-term from long-term memories. We forget the number of our hotel room on route to the airport, but we cannot forget our first kiss, nor unlearn how to ride a bike. We are enjoined to forgive trespasses against us—precisely because we cannot forget them. Thus, we must expect that adaptations to a drug altering myriad physiological systems, both somatic and neural, might be hard to erase.

Conclusions

Current evidence does not support the hypothesis of depression as a localized, disordered neural circuit. The mental disturbance manifest as depression cannot be identified by neuroimaging, and there are plausible reasons why small studies generate such erroneous claims44. Nor can depression be predicted in individuals by analyzing their genetic variants. “Chemical imbalance” theories of depression have not been supported, thereby removing any scientific rationale for “antidepressant” drugs. The drugs are not specific but rather affect myriad neurotransmitter systems, offering little advantage for most individuals, but commonly causing long-term harm. The brain adapts to antidepressant drugs, just as it adapts to drugs of abuse, and so for both withdrawal can be extremely difficult.

Depression is far better predicted by levels of childhood trauma, life stress, and lack of social supports. Depression in individuals is significantly reduced by physical repairs to their depressed communities and by psychological repairs through shared experience of childhood trauma and chronic domestic abuse (see ref. 28). Neuroscience should identify therapies with large effects that do no harm: these include affective and cognitive repairs to the individual, family, neighborhood, and society. People need assistance in healing trauma and reasons for hope. Drugs may temporarily distract us from these deepest needs, but generally, because they lack a rationale, they impede the way forward.

Acknowledgments

I thank Simon Laughlin, Stan Schein, David Linden, Robert Williams, and Michael Platt for general comments and Irving Seidman, Sally Zigmond, Peter Strick, and Brian Wandell for several specific suggestions.

References

- Sterling P and Laughlin SL (2015) Principles of Neural Design. MIT Press Cambridge.

- Sterling P, (2020) What is Health? Allostasis and the evolution of human design. MIT Press. Cambridge.

- Bae YJ, Kim J-M, Sohn C-H, et al. (2021) Imaging the substantia nigra in Parkinson disease and other Parkinsonian syndromes. Radiology 300:260–278.

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR Jr, Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, and Raichle, ME (1997) Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature 386, 824–827.

- Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, Dunlop K, Mansouri F, Meng Y, Fetcho RN, Zebley B, Oathes DJ, Etkin A, et al. (2017) Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Med. 23: 28–38.

- Nour MM, Liu Y, and Dolan, RJ. (2022) Functional neuroimaging in psychiatry and the case for failing better. Neuron 110: 2524-2544.

- Schmaal L, Pozzi E, CHo T, etal. (2020) ENIGMAMDD: 7 years of global neuroimaging studies of major depression through worldwide data sharing. Transl Psychiatry. 10:172. doi:10.1038/s41398- 020-0842-6

- Winter NR, Leenings R, Ernsting J, et al. Quantifying deviations of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder across neuroimaging modalities. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online July 27, 2022.

- Kuzminskaite E, Penninx BWJH, van Harmelen AL, et. al. (2021) Childhood Trauma in Adult Depressive and Anxiety Disorders: An Integrated Review on Psychological and Biological Mechanisms in the NESDA Cohort. Affect Disord. 283:179-191.

- 10. Kuzminskaite E, Vinkers CH, Milaneschi Y, et al. (2022) Childhood trauma and its impact on depressive and anxiety symptomatology in adulthood: A 6- year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 312:322-330.

- Lippard ETC and Nemeroff CB (2020) The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders Am J Psychiatry 177:1 20-36.

- McCrory E, Foulkes L, and Viding E (2022). Social thinning and stress generation after childhood maltreatment: a neurocognitive social transactional model of psychiatric vulnerability. Lancet Psychiatry. Published online August 1, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00202-4

- Schmaal L (2022) The Search for Clinically Useful Neuroimaging Markers of Depression— A Worthwhile Pursuit or a Futile Quest? JAMA Psychiatry. Published online July 27, 2022

- Rajtmajer SM, Errington TM, Hillary FG. eLlife. (2022) How failure to falsify in high-volume science contributes to the replication crisis. eLife 11: e78830.

- Wray NR, et al. (2018) Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nature Genetics. 50: 668–681

- Howard, D et al. (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nature Neuroscience | VOL 22 | MARCH 2019 | 343–352 |

- David Curtis (2021) Analysis of 50,000 exome-sequenced UK Biobank subjects fails to identify genes influencing probability of developing a mood disorder resulting in psychiatric referral. Journal of Affective Disorders 281: 216–219

- Levey DF, et al. (2021) Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in >1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nature Neuroscience | VOL 24 | JULY 2021 | 954–963

- Geschwind D. (2017). Human cognition and genetic variation: life on a continuum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-P2w3RR9wk

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Ambler A, et al. (2020). Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Disorders and Comorbidities Across 4 Decades Among Participants in the Dunedin Birth Cohort Study. JAMA Network Open. 3:e203221.

- https://www.science.org/content/article/two-psychologists-followed-1000-new-zealanders-decades-here-s-what-they-found-about-how (2018)

- Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, et al. (2019). Exploring comorbidity within mental disorders among a Danish national population. JAMA Psychiatry. 76:259-270.

- Wilkinson R and Pickett K (2010). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Press New York.

- South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, et al. (2018) Effect of Greening Vacant Land on Mental Health of Community-Dwelling Adults: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 1:e180298.

- South EC, MacDonald J, and Reina V. (2021) Association Between Structural Housing Repairs for Low-Income Homeowners and Neighborhood Crime. JAMA Network Open. 4:e2117067.

- Eberly LA, Julien H, South EC, et al, (2022) Association Between Community-Level Violent Crime and Cardiovascular Mortality in Chicago: A Longitudinal Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 11:e025168.

- Sterling P, Platt ML (2022) Why Deaths of Despair Are Increasing in the US and Not Other Industrial Nations-Insights from Neuroscience and Anthropology. JAMA Psychiatry. 79:368-374.

- Peretz A (2021) Opening Up. Radius Book Group New York.

- Sterling P (2014) Homeostasis vs Allostasis. Implications for Brain Function and Mental Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71:1192-3

- Anga B, Horowitz M, and Moncrieff J (2022) Is the chemical imbalance an ‘urban legend’? An exploration of the status of the serotonin theory of depression in the scientific literature. SSM – Mental Health 2 100098

- Khan A, Faucett J, Lichtenberg P, Kirsch I, Brown WA (2012) A Systematic Review of Comparative Efficacy of Treatments and Controls for Depression. PLoS ONE 7(7): e41778.

- Stone MB, Yaseen ZS, Miller BJ, Richardville K, Kalaria SN, Kirsch I. (2022) Response to acute monotherapy for major depressive disorder in randomized, placebo-controlled trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration: individual participant data analysis. BMJ 378:e067606

- Nevels RM, Gontkovsky ST, and Williams (2016) Paroxetine—The Antidepressant from Hell? Probably Not, But Caution Required. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 46:77-104.

- The distribution of muscarinic M1 receptors in the human hippocampus. Scarr E, Seo MS, Aumann TD, Chanad G, Everall IP, Deana (2016) Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy 77:187–192.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paroxetine#Pharmacology

- Finkel MS, Laghrissi-Thode F, Pollock BG, and Rong (1996) Paroxetine is a novel nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Psychopharmacol Bull. 32:653-8.

- Brackley AD and Jeske NA (2022) Paroxetine increases delta opioid responsiveness in sensory neurons. eNeuro. 9:ENEURO.0063-22.202 2.

- Wang CS, Kavalalin ET, and Monteggia LM (2022) BDNF signaling in context: From synaptic regulation to psychiatric disorders, Cell 185:62-76

- Casarotto PC, Girych M, Fred SM, et al. (2021) Antidepressant drugs act by directly binding to TRKB neurotrophin receptors. Cell 184, 1299–1313.

- Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/expert-answers/antidepressant-withdrawal/faq-20058133#:~:text=To%20minimize%20the%20risk%20of,the%20absence%20of%20the%20medication. (Accessed 9/8/2022) (edited for brevity).

- https://psychcentral.com/drugs/zoloft#zoloft-vs-lexapro (edited for brevity). (Accessed 9/8/2022)

- Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, Guidi J Jenny Guidi, Offidani E. (2015). Withdrawal Symptoms after Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation: A Systematic Review. Psychother Psychosom 84:72–81

- Hyman SE, Nestler EJ. (1996) Initiation and adaptation: a paradigm for understanding psychotropic drug action. Am J Psychiatry. 153:151-62.

- Marek S, Tervo-Clemmens B, Calabro FJ, Montez DF, Kay BP, et al (2022) Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature. 2022 603:654-660.

Disclosures: Peter Sterling reports no financial interests to disclose.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from The Thomas Jobe Fund.

This “depression muddle” is what happens when you mistake a syndrome for a single disease and erroneously seek a single cause to “explain” its presence. It would actually be a miracle if you discovered much of anything, as you’re dealing with a heterogeneous population, whose difficulties aren’t likely to be universally consistent.

Report comment

The way doctors treat depression is like endlessly giving someone aspirin to treat a fever without ever looking for the cause.

Report comment

Thank you Peter for this article.

When I was a kid I asked my parents why people use illegal drugs. They said it was because they couldn’t face reality.

It seems most neuroscientists aren’t much different.

Inventing elaborate diagnostic labels and getting immersed in complicated neurological “studies” is a way for people to distance themselves from dealing with painful psychological and social realities, and provides a way to insulate themselves from feeling any responsibility for what causes them.

So what is psychiatric neuroscience? Intellectual junk food.

Report comment

Peter,

Thank you for mentioning acupuncture. I found it does an amazing job calming down my nervous system.

It’s my belief that early or unrelenting emotional and psychological stress can get encoded in parts of the brain, but that doesn’t indicate biological cause or discrete “illness”. And I think non-invasive things like acupuncture helps unlock and rewire things. At the very least, acupuncture relieves physical tension, and even physical pain, which often eases psychic tension, which can lead to more positive outlooks.

It’s too bad America’s gotten so goddamn neuro-fixated and drug-happy.

Report comment

I also believe that unrelenting or repeated emotional and psychological stress/trauma is what causes most “mental illness”, even such devastating conditions like “Bipolar”, (be it 1 or 2), or “schizophrenia”. So how come some people develop these problems while others don’t? Because people experience and process things differently, which doesn’t mean “illness”.

And “psychiatric neuroscience” has yet to prove otherwise. But some people like building roads to nowhere.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

And why does greening vacant lots in depressed neighborhoods cause improvements to individual mental health?

BECAUSE IT MEANS SOMEBODY GIVES A DAMN —

Report comment

Here’s a simple fact: if you’re treated like shit, you feel like shit.

So what’s the first thing wrong with “psychiatric neuroscience”?

It puts the cart before the horse.

Looks like the dumbbells of neuroscience forgot the law of cause and effect.

Report comment

Here’s a simple fact: when you’re treated like shit, you feel like shit.

So what’s the first thing wrong with “psychiatric neuroscience”?

It puts the cart before the horse.

Looks like the yahoos of neuroscience forgot the law of cause and effect.

Report comment

Thank you for your honest assessment of the fraud, and systemic child abuse covering up crimes, of the psychiatric and psychological fields, Peter.

Report comment

I do not understand how neuroscience justifies saying anything about higher-order phenomena like personality, emotions, etc. given the Hard Problem of Consciousness.

I have faith in the observations of more directly mechanistic causation such as motor functioning and brain regionality. Anything beyond that seems to be flagrant abuse of correlation-causation.

Would love to see a truly frank discussion of that topic at some point on MIA.

Report comment

I agree completely. It is presumptuous to assume the right to assign cause to something that one doesn’t even know how to define!

Report comment

“Here is an opportunity for neuroscientists to pause and reflect. Probably BDNF’s selective activation of TRKB belongs to the brain’s overall design (see ref 1). Would it be so smart, then, especially without an identified pathophysiology, to activate all types of plasticity across the whole brain? Would it be clever to erase a traumatic memory from the human hippocampus, as apparently we can do now in mice? Would that relieve depression, or would it engender a new source of misery: still depressed but unable to recall why? To get this right, neuroscientists should first ask: which are the most appropriate levels to intervene?”

It is an amazingly well researched article, to the T!

We can erase a traumatic memory from mice? I wonder where this proof comes from, added to that I agree that even if this were possible that it’s not a good idea because one might forget why one is depressed.

When children are forced to behave a certain way, treated in a manner which by their parents is considered discipline, but in reality can be seen as trauma, I think they also fail to remember the trauma. People with multiple personalities have also quite sophisticated ways of putting memories beyond reach, but the memories still are there. In fact, this suppressing of traumatic memories, especially when the trauma was used as a mind control vehicle, this exhibits itself not only in various institutionalized settings (social groups, academic groups, religious groups etc.) but extends to whole countries or cultural groups that have been at war for generations because one was always taught to hate the enemy, hatred that was traumatized into children at a young age, and thus it’s never questioned but has become a reflex. Conflict is sustained rather than what would resolve it, and who profits from this?

So, I really wonder what’s done to these mice to allegedly rid their hippocampus of traumatic memories. Although it’s only stated that “apparently” we can. Thus implied that it’s only an observed phenomenon and that something else might be going on. You can traumatize the person or the brain to not remember trauma, but you can do who knows what to accomplish a state where memory of the trauma is shown to not be there anymore, but what else has been lost, and where really has that memory gone?

To study how to erase a memory of trauma, one can only question why one wants to erase that memory. Isn’t that also what a child molester does, use trauma to prevent a person from remembering the trauma? That’s also what’s reported to be going on in mind control experiments such as MK-ultra, experiments allegedly imported through project paperclip from Nazi Germany after WW2, so that the Russians wouldn’t get their hands on it. Create reflexes through trauma, and then use trauma to erase the memory of the trauma used to create reflexes, and retain the reflexes as mind control. B. F Skinner gone over to the dark side.

How much of the populace of social workers, other medical professionals and psychiatrists have been brainwashed to have the reflex believing they are treating chemical imbalances, rather than creating them? How much is such an effect of what works to create “happiness” transposed to reflexes, associations and desires people have towards what kind of food to eat (whether it’s to feed their health or not), what to believe, what not to believe, what to wear (whether it’s functional or comfortable), etc. etc? And to sustain the reflexes, the belief in all of that “happiness” we have what’s outlined in the prior paragraph from what I already quoted at the beginning of this post: “Now it is reported that all three types of antidepressant—tricyclics, SSRIs, and ketamine—bind to TRKB, a receptor for the neuropeptide BDNF39. Binding facilitates the effect of endogenous BDNF, and this action is now hypothesized to be the mechanism of their action to elevate mood. BDNF localizes to both sides of synapses all over the brain and affects multiple forms of synaptic plasticity. The report acknowledges that “BDNF can trigger multiple and often contradictory functional consequences based on its mechanism of expression, site of release, and site of action”. Yet the report also notes a search for small molecules to selectively target TRKB.”

And more…..

It doesn’t work statistically, so what kind of “reflexes” is it supporting, in economic, social, scientific and belief (religious) trends that it’s market as if…… it does?

Report comment

How do neuroscientists know they’ve erased traumatic memories in mice? Do the mice actually tell them? And how did the mice get traumatized? Wait—let me take a wild guess—the mice sensed they were trapped and going to be tortured, or, to use more neuropsychiatrically polite lingo, used as “experimental subjects” for “research”. And if neuroscientists think what they’re doing is so fine and dandy, ask ‘em to use each other instead. I doubt any of them would volunteer to be their next lab rat.

All they’re doing is high tech lobotomies.

Report comment

No psychiatrist, or neuropsychiatrist, will tell you depression is a homogenous disorder. Most will tell you that a lot of the people diagnosed with it don’t have any kind of mental illness, or even a disorder. That doesn’t mean that depressives who go into a catatonic state or people who experience depression and mania simultaneously are perfectly normal, or that their suffering is similar to emotional suffering, or that most people experience something similar. They don’t.

Parkinson’s wasn’t always well understood. Did Parkinson’s not exist when no one knew what caused?

There has been research showing anomalies in the brains of the depressed, and people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Just because something isn’t completely understood yet doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. You might want to talk to people with severe depression or bipolar disorder about their experiences instead of just assuming they’re imagining things. It’s cruel and dehumanizing.

They’re not there yet. They’re working on it:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/brain-imaging-identifies-different-types-of-depression/

Report comment

But they have not yet realized what you said, that “depression” is not a “homogeneous disorder.” They continue to comment on and “diagnose” “major depression” based on subjective criteria, and studies are done over and over on groups of people “diagnosed with major depressive disorder.” The only way anyone will make ANY kind of progress on if there is a subgroup who actually DO have something physiologically wrong with them is to STOP grouping heterogeneous people together as if they all had one “disorder,” and instead start breaking down the subgroups and try to find some who actually DO have something in common with each other.

And I have no faith that brain scans are the way to do this. But even the link you mention still talks about “different types of depression” rather than “some depressive symptoms may have a biological cause.” They are still running on the assumption that ALL cases of depression are “medical,” that ALL of them are caused in some way by biological anomalies, and that sorting these “depressed people” into categories will solve the problem. Until and unless they begin to recognize that MOST cases of “depression” are NOT caused by biological problems, but by a wide variety of social, interpersonal, and individual psychological needs, and that even those cases which DO have biological causes need to be checked for things like sleep deprivation, nutritional deficiencies, anemia, and so forth before jumping to the unwarranted conclusion that something is wrong with their brains and that brain scans will somehow answer this very complex question.

And finally, if “they are not there yet,” why do “they” pretend that they ARE there and claim things are true that they don’t know about? Why do “they” get so threatened when people point out there are 80% or higher associations between MDD and childhood adversity/trauma and that attacking THAT problem will probably be a lot more fruitful than experimenting on people’s brains when you don’t really know what you’re doing?

Report comment

I agree, all the way. That’s part of my frustration — I have bipolar disorder and people think the depression is something along the lines of low self esteem or being unhappy with my life. It isn’t, and it doesn’t remotely resemble anything like that. It doesn’t even seem to have to do with the content of my thoughts. It’s like mania — an abnormal mental state.

I think lots of psychiatrists are well aware there’s a problem with depression and with lots of diagnoses, particularly since some psychiatric diagnoses seem to have become trendy. I’ve read complaints about it. Someone reads about bipolar 11 and thinks their moodiness resembles the symptoms, then goes to the psychiatrist and says s/he has those symptoms. You have to question them carefully, you don’t want to give them the toxic drugs prescribed for bipolar unnecessarily, you also don’t want to give them an antidepressant in case they really do have bipolar. It’s a mess.

My mother was offered an antidepressant by her GP when she was caring for my terminally father. She hadn’t even used the word depressed, and she didn’t think she was. So I agree there definitely a lot of doctors who are medicalizing suffering.

I also think a lot of the difficulty is that you can have depression of the endogenous sort without it being severe. I’ve experienced it myself, for much of my life. So people can indeed be “depressed” in the mentally ill way without there being an obvious sign like psychomotor retardation. If that’s the case, you want to try to treat it and hopefully prevent its progression. However, if what’s going on is more like what I read one psychiatrist refer to as “s*hit life disease,”you’re giving them pills for no reason.

There’s an environmental component to even bipolar and schizophrenia. Twins don’t match up 100%. And therapy can help even what’s considered severe mental illness. The issue there is, in my experience, most therapists aren’t trained in those therapies.

I’m short, I agree it’s a disaster. But I don’t like depression treated like it isn’t a real mental illness just because most of the people diagnosed with it aren’t mentally ill. The real deal depression is horrific. Most people are lucky enough to never experience it. My guess is it’s about as common as bipolar or schizophrenia- about 1%. That’s just a guess.

Report comment

Well, they will never be able to help the 1% until they start admitting that the 20% that are diagnosed are 19% having a hard time with a traumatic existence. And I agree, the severity is not related to whether or not it’s a “biochemical depression,” if such a thing is proven to exist. Many, many cases of experiential depression are incredibly severe! And as you say, there are some people who have depressive tendencies that are mild but chronic who may very well fit into the same category with someone who is genuinely “seriously depressed for no reason.” Until there is some effort to actually make this distinction, any case of ACTUAL biological depression will be totally submerged in the flood of experiential depression cases and will never be identified or detected as a valid group for study. And I don’t see psychiatry being willing to go there any time soon. There is WAAAY too much money being made under the current model, even when they themselves know it’s not a valid model at all.

Report comment

@Walter:

People always bring out the MRIs and fMRIs claim even though it’s actually pointless in real life. Have you gone to a neurologist, taken an MRI (or anything else like an EEG), and then given it to another neurologist (or heck, even a psychiatrist) who does NOT know what your problem is, but he can still look at the image and tell you your “diagnosis”? Most people who talk of MRIs/fMRIs have never done that. Almost NO ONE who gets into a psychiatrist’s office ever has any kind of imaging done on them. Maybe just those who get put in research studies. But they certainly sell that line so much! MRIs and fMRIs and EEGs!

It’s just a selling point to shut people up for a variety of reasons:

i.) people trying to tell others “Look my suffering is real! They have proof from MRIs!” (despite never having seen an MRI of their own brain).

ii.) people trying to tell others they can’t accept their problems: “Look, MRIs show that people like you have X and Y abnormalities. Shut up, sit down and take your pills” (once again, despite never having seen an MRI of the brain of the person they’re talking down to).

iii.) Mental health workers trying to desperately legitimise what they’re doing when confronted by skeptical suffering individuals: “Do you believe in MRIs and fMRIs? See this textbook”? The guy will be much more likely to go along with their plan of help when they spout this.

iv.) Gaslighting: “Well, bad brains and bad genes. They say it can be seen in MRIs”. What more can you say?

Did you sit down with a doctor and cross out all medical/neurological problems that could be causing your problems before it being placed in the “idiopathic” bin of psychiatry?

BTW, I agree that depression and mania are very real, can be very serious and disabling, and the pathways to them both are many. I don’t deny or invalidate the suffering of people.

What you perhaps also don’t understand is how much cruelty and dehumanising of people, how much gaslighting and scapegoating goes on under the guise of “bipolar”, “schizophrenia”, “borderline” etc. either. Your desire to “validate” your “bipolar” and your talk of “brain abnormalities, there is so much we don’t know” (this is actually pretty typical talk of people fairly new into psychiatry) could lead you down a very dark place in life.

I don’t know what caused your depression or your mania, because there are a whole host of reasons that could happen. Smoking marijuana can cause mania resulting in a “bipolar” categorisation applied on the person. Antidepressants prescribed for anxiety can cause mania resulting in a “bipolar” categorisation. A person could have a “spontaneous” episode of mania resulting in a “bipolar” categorisation being given to them. For a certain individual, an “antidepressant” not working for depression, but a “mood stabiliser” working to alleviate his depression could lead to a person being categorised as “bipolar”. All different circumstances. I’m pretty sure all their brains and life experiences are different.

Whatever works for you. At the most, if you are placed in the bin of psychiatry, you will get 3 things in life: listening and talking, pills and psychiatric categorisations (don’t expect it to stop at “bipolar” because you could get 5 or 6 more down the line). If it works for you, great. If you are unlucky, you will face coercion and gaslighting and basically your life will get screwed.

I hope it works out well for you.

Report comment

Wonder if this caused parkinson.

https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2009/January/09-civ-038.html#:~:text=American%20pharmaceutical%20giant%20Eli%20Lilly,Department%20of%20Justice%20announced%20today.

Report comment

So, today I went to a Neurologist and checked out if my brain actually shows any sign of abnormalities on an MRI. Well, the neurologist looked at my scan and could find nothing.

The radiologist’s observations are thus:

i.) Brain stem and cerebellum are normal.

ii.) Cerebrum is normal. No focal lesions noted.

iii.) Ventricular system is normal.

iv.) Basal cisterns, sylvian fissures and cerebral sulci are normal.

v.) Visualised cranial nerves appear normal.

vi.) Internal auditory canals and their contents are normal.

vii.) Visualised dural venous sinuses and deep cerebral veins are normal.

viii.) Sella and pituitary gland appear normal. No obvious lesions noted.

ix.) Orbits and their contents are normal.

Impression: Normal Study

—

What’s the next thing I need to do? Get an ultrasound of my brain? Will try that one day too. God, people love selling this imaging shit so much. I wish that I had this MRI in my hand when a psychiatrist first told me “do you believe in MRIs and fMRIs?”. People STILL all over forums, comment sections and chatrooms tell others about brain imaging to shut them up. Poor souls have never seen any imaging of their brain so they have nothing to counter with.

But of course, it doesn’t end there. Once you have this in your hands, they have to go back to: “It’s all neurotransmitter based, you can’t see it in brain scans”. Then STFU about the brain scans.

Report comment

The brain imaging stuff is almost all smoke and mirrors anyway. They find that on the AVERAGE, people who “have major depression” have lower activity in X area. They DON’T tell you that not all people labeled with “MDD” have lower activity in the area, some have HIGHER activity, some “normal” people have lower activity and are NOT depressed. So their findings are meaningless.

Add to that the fact that the brain is constantly changing and that PET scans and SPECT scans measure activity levels, and the whole thing really comes apart. I recall an experiment where they had people think about something sad that happened. Their brain scans changed. Then they had them think about something happy that happened. Their brain scans changed back. So thinking a THOUGHT changes your brain activity levels, and the whole idea that higher or lower activity in a certain area means something chemically or structurally wrong is completely debunked.

Report comment

It also doesn’t say anything, if there’s consistent correlation. Which there isn’t here. If you hurt yourself and have a scar, and this is consistent, that doesn’t mean that the scar is a chemical imbalance, not even when the scar hurts. To alleviate the pain (that way you can repeat what caused the scar, possible, and blame it on the scar), this does what?

Your abuser isn’t hurting you

Thou shalt not be sad

Report comment

[Duplicate Comment]

Report comment

Maybe someday the “psychiatric” neuroscientists of the world will realize a lot more can be learned about human consciousness from staring at Rorschach ink blots, or gazing at the stars, or watching the clouds go by, or just looking through their kids’ kaleidoscope! Which reminds me of some song lyrics I heard, once upon a time, “the more you learn, the less you know…”

Report comment

There wasn’t much ‘depression’ until Prozac entered the market – as a treatment – in the later part of the 1980s. Now ‘depression’ is a major illness, even though Prozac has been proven NOT to work most of the time.

Report comment

I would say that there was plenty of “depression” but it was transitory, and understood to be in most cases a normal reaction to adverse circumstances. It seems clear that “antidepressants” are quite capable of taking temporary “depression” and making it permanent. Another psychiatric success story!

Report comment

It’s an interesting conversation point about shifting understanding of what experiences to label as “depression” and what the heck such a label even means. Fifty years ago someone might be having a bad time of it but not use the word “depression” for it. The felt experience didn’t change, but the words used to describe and conceptualize it did.

As you identify, we’re certainly in a period of increasing framing of experience as “mental illness”, which certainly plays into a power narrative of individualized distress with individualized solutions, including both psychotherapy and psychiatric drugs.

Report comment

For the 15% of people for whom the ADs really works, what could be concluded? That their depression or anxiety is biological?

Report comment

Not at all. Drugs work for all sorts of reasons. All it means is that that particular 15% responds positively to antidepressants. There is no other conclusion that can be drawn.

Report comment

And for those whose quality of life is really improved by ADs would you recommand using them? Or this is too much risk?

My psychiatrist argue that having anxiety, stress, or depression all your life isn’t better for the brain…

Report comment

Your psychiatrist is simply telling you what they believe. I know of no data suggesting that “untreated” anxiety is any worse than “treated” anxiety, and the same for every other “mental health condition” in the DSM.

As to whether or not it’s worth it for the “benefits,” that’s something each individual has to decide. My personal view, though, is that the less drugs I take, the better. ALL of them have adverse effects, and the list for antidepressants is quite long. Read up on the issue and see what you think. And remember, recovery rates were MUCH higher before antidepressants existed, and there are LOTS of other things you can do instead that DON’T have these bad effects on your body!

Report comment

@Madineamericonaute:

Let me be honest with you. If ADs are working for you, continue taking them at your own discretion. You mentioned that you were performing much better when you were on them (which is a good reason to take them) but are worried about the long term effects (which is a good reason to arm yourself with more information). No one should talk you out of taking them or into taking them without you being the first judge of it. It is you who is putting them into your body and it is your life that will be affected by it.

On the internet, you’ll find people who have experienced permanent Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction. While sexual dysfunction on SSRIs is common, sexual dysfunction becoming permanent is uncommon (though it happens to some people). But if you consecutively read 10 experiences of people who have experienced PSSD (permanent sexual dysfunction), you will panic, even if that might not apply to you.

If you find some articles or research papers whose results are alarming, talk about it with your prescriber. If your prescriber does not have much knowledge or simply does not want to acknowledge any harms despite evidence to the contrary, find another one.

Try out Surviving Antidepressants. I have never used it, but you might find much more knowledgeable people there.

But ultimately, you are the judge of it. Don’t make hasty decisions.

Report comment

Your doctors are deceiving you if they are claiming SSRI’S are safe for longterm usage. The reality is they just don’t know because there are not good longterm safety studies and the ones we have show some side effects may be permanent is some patients. We do know the drug companies denied the side effects until the FDA forced a change to the warning labels. Even today the warning labels are deceptive. Claiming sexual side effects are temporary when they can be permanent or claiming the drugs aren’t addictive despite the evidence shows they are still being deceitful.

SSRI’S have a strong anti-inflammatory effect and most drugs that do that will also reduce depression and potentially cause mania (think of the steriod high). I’ve taken Paxil on and of since it came out and understand it’s benefits as well as anyone. I also understand that the potential benefits do not justify exposing patients to dangerous side effects doctors don’t understand.

The drugs can have great benefits but few doctors are properly trained in their safe usage. I encourage you to get the opinion of a mental health professional who’s business model doesn’t depend on the belief SSRI’S are safe.

Report comment

A useful starting point is understanding that all psychiatric research is based off of correlation, not causation. For those who self-report, without coercion, that a give medication helps, there is no mechanistic understanding as to why. That doesn’t mean it’s not doing something. But it means we can’t say for sure why it’s working.

We put gas in a car, we know exactly how and why that makes an engine run.

But we simply do not know the exact mechanisms of the brain that give rise to experience, including the experiences of love and joy, as well as anxiety and depression.

Report comment

Nor do we know if such processes are even located in the brain.

Report comment

“Study findings generally support moderate efficacy of clinically employed antidepressants for acute major depression”

A person suffering from acute major depression is thrilled with any relief she receives from her suffering, I imagine.

How much does quantum mechanics play a role in our testing of the brain?

Report comment

Psychiatrists have a bad history adopting new technology. Look at what they did with advancements like electricity, brain surgery, and pharmaceuticals. Then again maybe if an AI tells them they are full of crap they might actually believe it.

Report comment

LOL!

Report comment