“The expanding use of fast-acting NMDA receptor antagonists for psychiatric disorders is a significant risk to the public.”

That’s the conclusion drawn by researchers in a new multidisciplinary review in the journal Pharmacotherapy. They evaluated 60 years of studies on ketamine (and its newer variety, esketamine) for depression treatment, and write that their evidence serves to “raise substantial questions about both safety and effectiveness of ketamine and esketamine for psychiatric disorders.”

The study was led by Thomas J. Moore at the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, and the Department of Epidemiology, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University.

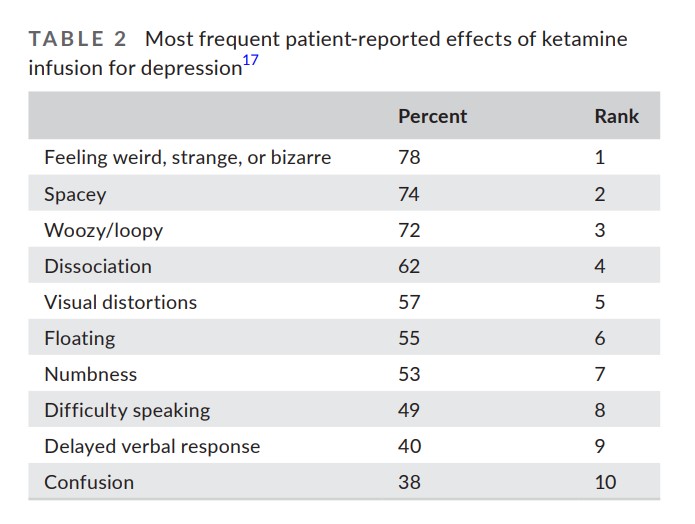

Two of the challenges of ketamine research are a) ensuring that clinical trials are appropriately blinded, and b) differentiating ketamine’s supposed rapid antidepressant effect from the euphoric high that recreational drug users experience. The table below, compiled from data in a 2020 study by the current authors, demonstrates the common consciousness-altering effects of ketamine infusions that patients report experiencing during treatment for depression:

The idea that 78% of patients could experience “feeling weird, strange, or bizarre” and not guess that they are in the ketamine group—rather than on placebo—is unlikely.

Additionally, the researchers report that more than a quarter (27%) of patients experience “euphoria”—a drug high that drives recreational use. Does the drug have a rapid antidepressant effect on people with depression, or are its users experiencing the same brief high as recreational users?

Ketamine Efficacy

According to the researchers, ketamine’s status as a potential breakthrough depression treatment came in 2000, when a small study out of Yale found that ketamine infusions led to a large average decline in depression within 72 hours. However, this study was incredibly small—including only seven patients.

Four systematic reviews of the ketamine efficacy research were published in 2014-2015. The researchers note that while these reviews found large and rapid antidepressant effects for ketamine, the studies they included were all at high risk of bias, did not use a true blinded comparator group, used very small sample sizes (ranging from 4 to 47 patients), and included only extremely short-term data.

“The trials with one exception featured a single infusion of ketamine, and none measured the effect later than 14 days, leaving duration of benefit uncertain but openly questioned in the report texts. With one exception discussed below, none of the trials featured a design with blinded active-drug controls. This was especially relevant given a drug that within 40 min of administration induced an altered state of consciousness that would be immediately evident to the patient and probably the investigator. The altered state of consciousness would compromise blinding in the four clinical trials with a crossover design.”

So, what of the one trial that was an exception to this rule?

This study was the largest and included an active placebo—a benzodiazepine, intended to mimic some of the consciousness-altering effects of ketamine. This study found a large, rapid antidepressant effect for ketamine in treatment-resistant depression (people who had not responded to at least three previous antidepressant drugs).

However, although it was the largest study of ketamine, the trial only included 47 people—small by most standards. Moreover, it was led by authors with significant conflicts of interest; two of the authors—and one of the two medical centers used for the study—held patents on ketamine (which would only be lucrative if the FDA approved the drug based on their study). Four authors were consultants for pharmaceutical companies.

Esketamine Efficacy

The researchers write that those small, biased studies of ketamine infusions tend to find a large, rapid antidepressant effect—but the strict, well-conducted studies of esketamine (Janssen’s trademarked version of ketamine, also known as Spravato) don’t replicate this finding. Instead, with larger studies, more governmental oversight, and stricter methods, esketamine generally fails to induce any antidepressant effect over placebo.

“The promising results seen in the small, single-infusion, single-center trials of racemic ketamine were generally not replicated in the larger, multi-site trials of esketamine nasal spray,” the researchers write. “The esketamine trials were also subject to FDA site inspections, data integrity checks, and other forms of independent scrutiny.”

Esketamine was approved by the FDA for use in treatment-resistant depression in a controversial decision, according to the researchers. Indeed, Erick Turner, a member of the advisory board that recommended approving the drug, wrote a scathing editorial about the decision in Lancet Psychiatry, calling it “a historic break from precedent.” Other researchers called it “flimsy evidence.”

Esketamine failed to beat placebo in five of its six clinical trials. Researchers referred to it as approval of an ineffective drug with known harms and called it “repeating the mistakes of the past.” And safety concerns were emphasized by other researchers.

Indeed, according to Moore and his co-authors, although the FDA granted “breakthrough status” to esketamine because of its rapid antidepressant effects in a phase 2 trial, none of the larger, more strict phase 3 trials met the FDA’s criteria for such an effect.

Esketemine’s efficacy for reducing suicide risk was also tested in three clinical trials. It didn’t reduce suicidal ideation in any of them:

The researchers write: “The trials to document the expected benefits of a rapid reduction in suicidality were an unambiguous failure.”

Despite this, the FDA granted Janssen an expanded indication, allowing esketamine to be used for treating suicidality—apparently based on those failed trials, according to Moore and his co-authors.

“Although an FDA-approved indication normally means ‘substantial evidence’ of benefit,” the researchers write, “the indication contained the unusual qualifier, ‘The effectiveness of SPRAVATO in preventing suicide or reducing suicidal ideation or behavior has not been demonstrated.’”

Safety

Nor are ketamine and esketamine as safe as advertised. The researchers write that studies in animals since 1989 have consistently found neurotoxic effects of the drugs, and studies in human recreational users found reduced cortical thickness and damaged cognitive performance. The FDA accepted three toxicology studies supposedly proving the safety of the drug, but all three involved only a single dose delivered to rats.

There is very little official data about the long-term use of the drugs, since most trials are limited to extremely short term (two weeks or less) outcomes. The FDA accepted one open label (unblinded), 1-year study of 100 patients who had already responded well to ketamine as evidence of its safety.

According to the researchers, “Almost any drug intervention can be made to appear safe or beneficial if unblinded and limited to a small group of patients who, from the onset, had already responded well.”

Although ketamine is supposed to reduce suicidality, it instead seems to consistently cause it: In one recent study, it failed to beat placebo for reducing suicide attempts, and one person died by suicide after taking the drug. In a 2016 study of 12 people, one person died by suicide after taking the drug and another was hospitalized after expressing suicidal intent. And a 2013 study demonstrated delayed-onset suicidal ideation, dysphoria, and anxiety in 2 out of 10 people taking ketamine infusions—who had minimal depressive symptoms when the study began.

In a study of the first four patients to receive esketamine treatments at one center, one ended up on antihypertensive drugs for life to manage the detrimental effect of esketamine on blood pressure, while another attempted suicide one hour after taking the drug. None of the patients were able to safely discontinue esketamine, with thoughts of suicide common after beginning to withdraw the drug.

According to a review of the esketamine studies, about 20% of people will experience bladder problems after taking the drug.

Moreover, a case study in the American Journal of Psychiatry demonstrated the frightening consequences of ketamine tolerance and withdrawal—as does another case study involving a patient prescribed ketamine who, after becoming dependent on the drug, turned to alcohol abuse and died by suicide.

In summary, the researchers write:

“Considering the scientific studies reviewed in this assessment, we find that neither ketamine nor esketamine has been shown to be safe for extended clinical use to treat depression. At subanesthetic doses, ketamine is a well-documented drug of addiction and abuse.”

****

Moore, T. J., Alami, A., Alexander, G. C., & Mattison, D. R. (2022). Safety and effectiveness of NMDA receptor antagonists for depression: A multidisciplinary review. Pharmacotherapy, 42, 567–579. DOI: 10.1002/phar.2707 (Full text)

What is described as researched is not the protocol for Ketamine.

It is strange to suggest that a single dose of anything making a major difference in serious, long-lasting despair. It entails the assumption that it is the treatment experience itself that lifts mood. This was not what I found.

I agree about the danger of esketamine. In this I’m assuming you are talking about multiple treatments, otherwise the bladder damage makes little sense – it is not a sequelae of a single dose. This is a problem arising from too much for too long.

As one who found profound benefit – not at the time of taking it but in the time outside of the actual treatment – (I found the actual treatment horrible not euphoric) – I’d like to hear about research findings of a few doses of Ketamine within a few weeks followed where necessary by widely spaced maintenance -as is the usual treatment protocol.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing this “Significant Risk to the Public,” of ketamine and esketamine, Peter.

Especially given the fact that those of us here know that many psych “professionals” now claim to not know what drugs are actually beneficial to their patients.

Particularly given the fact ADHD drugs and antidepressants can create the “bipolar symptoms,” and they’ve misdiagnosed the common, adverse, and withdrawal symptoms of those drug classes as “bipolar,” in millions of innocent children and adults, already.

https://www.amazon.com/Anatomy-Epidemic-Bullets-Psychiatric-Astonishing-ebook/dp/B0036S4EGE

And given the fact, that both antidepressants and antipsychotics are anticholinergic drugs, which are already medically known to create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Not to mention, the antipsychotics are also known to create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

So when do psychiatry and psychology stop trusting in Big Pharma? And stop misinforming their clients? Thank you, again, for sharing this “Significant Risk to the Public,” of ketamine and esketamine, Peter.

Report comment

You criticize the studies as being too small, or biased and then you do the unthinkable. You use studies for Esketamine to draw conclusions about IV ketamine. I would agree that Esketamine is ineffective, however it is a single isomer given intranasally. Providers like myself use a racemic mixture of ketamine given over a specified time period. Anyone with sense knows that the comparison of those 2 different drugs is ridiculous. That in itself makes the entire article bogus.

Report comment

There are two other issues.

Intravenous ketamine brings very short-lived effects. The effects described above are very brief and the patient is kept safe during that time. About twenty minutes to half an hour in total. This is the antithesis of being drugged around the clock.

The other thing is that brief periods involving just a few sessions do not cause the damaging effects that regular, long-term applications of the patented products do. When actual Ketamine was found to be beneficial for some people experiencing despair, there came a plethora of attempts to create a patentable, commercial product. Ketamine itself has been off-patent for decades.

In order to patent an off-patent drug, it needs to be altered in some way. It seems likely that the ‘need’ for a commercial product may mean the resulting commodity is less effective. It may also, potentially, be dangerous.

Off-patent Ketamine has been safely studied and used in controlled settings and for a variety of conditions, for a very long time.

Report comment

True! I.V. Ketamine should not be categorized in the same way that pharmaceutical versions, however the main question is what happens to these MI patients who get the IV treatment on a regular outpatient basis over years of “treatment” ? Ketamine is both sedating and stimulating at the same time which in the long run destabilizes the “patient”.

All of these con artists M.D.’s who run these highly profitable Ketamine + psychedelic treatment centers or private for-profit practitioners will not report adverse events and patients harmed will simply stop going after paying typically $400 per session where the dose of Ketamine used costs less than $10. Many “clinicians” are just money grubbing psychiatrists who are racking in millions of dollars each year. Another fad of psychiatry likely to the trove of “treatment resistant” patient pool.

Report comment

There are two other issues.

Intravenous ketamine brings very short-lived effects. The effects described above are very brief and the patient is kept safe during that time. About twenty minutes to half an hour in total. This is the antithesis of being drugged around the clock.

The other thing is that brief periods involving just a few sessions do not cause the damaging effects that regular, long-term applications of the patented products do. When actual Ketamine was found to be beneficial for some people experiencing despair, there came a plethora of attempts to create a patentable, commercial product. Ketamine itself has been off-patent for decades.

In order to patent an off-patent drug, it needs to be altered in some way. It seems likely that the ‘need’ for a commercial product may mean the resulting commodity is less effective. It may also, potentially, be dangerous.

Off-patent Ketamine has been safely studied and used in controlled settings and for a variety of conditions, for a very long time.

Report comment

There are two other issues.

Intravenous ketamine brings very short-lived effects. The effects described above are very brief and the patient is kept safe during that time. About twenty minutes to half an hour in total. This is the antithesis of being drugged around the clock.

The other thing is that brief periods involving just a few sessions do not cause the damaging effects that regular, long-term applications of the patented products do. When actual Ketamine was found to be beneficial for some people experiencing long-term and intractable despair, there came a plethora of attempts to create a patentable, commercial product. Ketamine itself has been off-patent for decades.

In order to patent an off-patent drug, it needs to be altered in some way. It seems likely that the ‘need’ for a commercial product may mean the resulting commodity is less effective. It may also, potentially, be dangerous.

Off-patent Ketamine has been safely studied and used in controlled settings and for a variety of conditions, for a very long time.

Report comment

Deleted at request of poster.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Ketamine is a controlled substance so how are these “clinics” and doctors getting a hold of such vast quantities? A pain management doctor told me that if he started ordering these large quantities it would alert the FDA to inquire about the reason and sources.

As Psychiatry fails, and the drug model proves to be a complete utter failure they try these psychedelics and Deep Brain implants (brain stimulation) as well as damaging electro-

shock “therapy”.

Now the large population of patients that have been harmed and labeled “treatment resistant” are candidates for “medical implants” where thanks to a law passed by Congress you cannot sue any of the companies.

Report comment

I’ve read the blog post discussing the significant risks associated with ketamine use. It’s crucial to have a balanced perspective on its benefits and potential harms. This article serves as a reminder of the complexities in psychiatric treatments and the importance of informed decisions in ensuring patient safety and well-being.

Report comment