In an article for Clinical Psychology Forum, disabled British scholars Tumu Johnson and Emily Joy Carroll highlight ten principles of disability justice that expand on the social model of disability. Going further, they discuss the oversights of the social model, namely the intersections of identity and lived experience that complicate disability.

“Alongside changing the ableist structures we live within, we feel that the move towards Disability Justice is in small acts within our everyday relationships,” Johnson and Carroll write. “It is in those mundane moments on google when you dig and dig to find the correct number for the community center to find access requirements, in the awkward conversations with families or colleagues, where disablist assumptions have taken root. Keep going!”

The article is structured by highlighting the principles of disability justice defined by Sins Invalid in 2015.

The article is structured by highlighting the principles of disability justice defined by Sins Invalid in 2015.

- Intersectionality

- The leadership of those most impacted

- Anti-capitalism

- Cross-movement solidarity

- Wholeness

- Sustainability

- Cross-disability solidarity

- Interdependence

- Collective access

- Collective Liberation

Before exploring the nuances of each of these principles, the authors draw attention to the deadly state of ableism in the United Kingdom. They note that 29 percent of working-age Disabled people live in poverty compared to 19 percent of non-disabled adults and that disabled people are almost twice as likely to be unemployed.

“During the global pandemic, blanket Do Not Resuscitate orders have been placed on Disabled people without their consent, and discriminatory health measures (such as frailty scores) used to determine access to critical care,” they add. “Embedded in our fields are the use of IQ tests, curtailing of freedom through psychiatric incarceration, and complicity with deeply racist and ableist institutions such as the police.”

The authors call for a radical reframing of disability not only in the UK but across the globe. The way forward, they argue, is through earnest dialogue with the ten principles of disability justice.

- Intersectionality: Disability justice models agree with the social model of disability that disability is constructed, as are gender and race. But disability justice takes it one step further. It highlights that both ability and disability are affected by racism, classism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and other powerful prejudices that complicate lives and lead to suffering and even death.

- The leadership of those most impacted: Fortunately, the social model of disability and prior disability and crip movements uniting around the mandate, “Nothing about us without us,” have brought inclusion issues to the forefront. This has increasingly led to disabled people at the decision-making table. However, rarely are psychosocially disabled people empowered to make decisions about their bodies, let alone choices about their physical world and accommodations.

- Anti-capitalism: If disability is socially constructed and affected by racism and classism, it is necessary to be staunchly anti-capitalist as a disability justice advocate, the authors argue. They write:

“Disabled people find themselves at a very specific juncture with capitalism, where we are asked: are we of any use? And if not, we ask: can we live?”

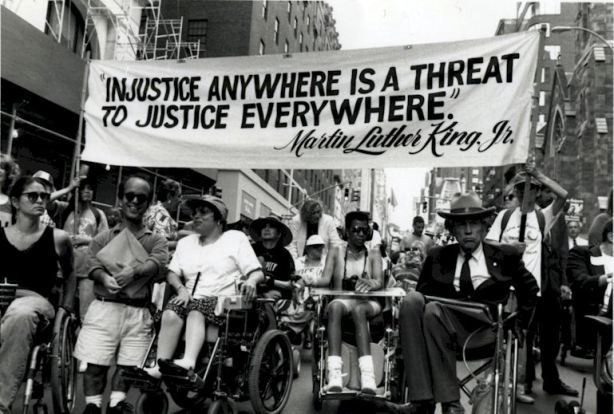

- Cross-movement solidarity: Cross-movement solidarity can build political power and bring about change. For example, the authors call on disabled people to show up for Black people and other groups that experience racism.

- “Wholeness” or “recognizing wholeness”: A kind of deficit-based mind-body dualism is fundamental to maintaining capitalism and ableist structures, claim the authors. Seeing someone as Disabled means understanding them as holistically Disabled—and then seeking meaningful accommodation. In services, this can look like holistic and spiritual therapy practices and or trauma-informed care.

- Sustainability: This principle prioritizes rest and recuperation—two things capitalism actively discourages. Sins Invalid puts it this way:

“We pace ourselves, individually and collectively, to be sustained long term. Our embodied experiences guide us toward ongoing justice and liberation.”

7. Cross-disability solidarity: This can look like mad and crip studies collaborating and working together. In mental health services, it can mean meaningfully and sustainably creating peer support networks. The authors explain:

“Solidarity recognizes our wholeness through interdependence and relationship. Solidarity is not charity, it builds grassroots power, not philanthropic or state power.”

8. Interdependence: To practice interdependence is to meaningfully look to your communities and ask for support and sustainability from them rather than the state.

9 and 10. Collective access and collective liberation: Be in community with others and create meaningful access to everyone so that when liberation does happen, it happens to everyone. The authors write:

“We do not dream of ‘services’ and ‘benefits,’ but collective liberation. We dream of a solidarity where Disabled people’s needs are not seen as individual, ‘other’ or burdensome, but are recognized as collective, inevitable and human.”

July is both Disability Pride month and Mad Pride month. While Psychosocial disability is frequently used in international conversations surrounding mental healthcare, some people who identify as mentally ill or mad, among other identities, have raised issues with the term “disabled.” The authors here make a case that identification with disability may create solidarity between mad liberation movements and cross-disability justice initiatives.

****

Johnson, T., Carroll, E.J. (2022). Constellations of disability: 10 Principles of Disability Justice. Clinical Psychology Forum. 1(353), 54-64.

How many are alone in their apartments because of physical problems and a history of being hurt when they have dared venture out in public?

Report comment

Great to learn about the disability justice and the social model of disability. Thank you Samantha!

Report comment