On March 27, Mad in America published a review of a “viewpoint” in JAMA Psychiatry that told of how psychiatry did not have evidence of “successful outcomes.” This prompted psychiatrist Awais Aftab to write a blog critical of our science reporting, with the March 27 report exemplifying our failure. He led his blog with a quote describing “rationalisation markets,” which was meant to describe our “insidious impact”:

“Rationalisation markets provide a helpful framework for understanding why certain information can often be so misleading even when it is accurate. To the extent that pundits or media organization exist not to inform, but rationalize, their insidious impact often lies not in the strict falsity of their content but in the way in which it is integrated and packaged to support appealing but misguided narratives.”

Mad in America gets criticized all the time, and for the most part, we just ignore it. Aftab has criticized us before, and so this too is nothing new. However, his criticism in this instance provides us with an opportunity not to be passed up, as it illuminates why Mad in America’s science coverage is so threatening to psychiatry.

Aftab has staked out a position as being open-minded to critiques of psychiatry, and that is a public stance that makes him particularly valuable to his profession. He can serve as a defender of psychiatry against critiques that are truly threatening, and his criticisms will be seen as coming from someone who is open-minded about psychiatry’s flaws.

Mad in America certainly offers a critique that is threatening to psychiatry, as our mission statement makes clear.

“Mad in America’s mission is to serve as a catalyst for rethinking psychiatric care in the United States (and abroad). We believe that the current drug-based paradigm of care has failed our society, and that scientific research, as well as the lived experience of those who have been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, calls for profound change.”

Our mission statement tells of a failed paradigm of care, with that failure documented in the scientific and medical literature. This is an assertion that psychiatry cannot let stand.

As such, Aftab’s criticism—which states that our coverage has an “insidious impact” because it is “packaged” in a manner that supports a “misguided” narrative—provides us with the chance to ask this question: Is it Mad in America that misleads the public? Or is it psychiatry, as an institution, that is guilty of this sin?

There is a journalistic history that serves as the foundation for Mad in America’s science coverage, and from there it is easy to show that Aftab, in his criticism of us, is seeking to protect psychiatry’s narrative of progress—a narrative that arises from psychiatry’s guild interests, and not a faithful record of its own research literature.

The Journalistic Path to MIA

The first time I reported at any length on psychiatry was in 1998, when I co-wrote a series for the Boston Globe on the abuse of psychiatric patients in research settings. As I have noted before, at that time I had a conventional understanding of psychiatric drugs. I understood that they fixed chemical imbalances in the brain, and thus were like insulin for diabetes. I also understood that the second generation of psychiatric drugs—SSRIs and atypical antipsychotics—were much better than the first generation of psychiatric drugs.

I had come to that understanding based on traditional newspaper methods of reporting on science. I called up experts in the field, and reported what they told me. They were the ones who knew the science. However, while doing the reporting for that series, I stumbled on findings that belied that narrative of progress.

First, I read two World Health Organization (WHO) studies that found that schizophrenia outcomes were much better in three developing countries—India, Nigeria, and Colombia—than in the U.S. and five other “developed” countries. In the second study, the WHO investigators specifically looked an antipsychotic use, and reported that schizophrenia patients in the developing countries used the drugs acutely but not chronically—only 16% of the patients were regularly maintained on the drugs. This was a result that didn’t fit with psychiatry’s claim that all schizophrenia patients needed to stay on these drugs because they fixed a chemical imbalance in the brain.

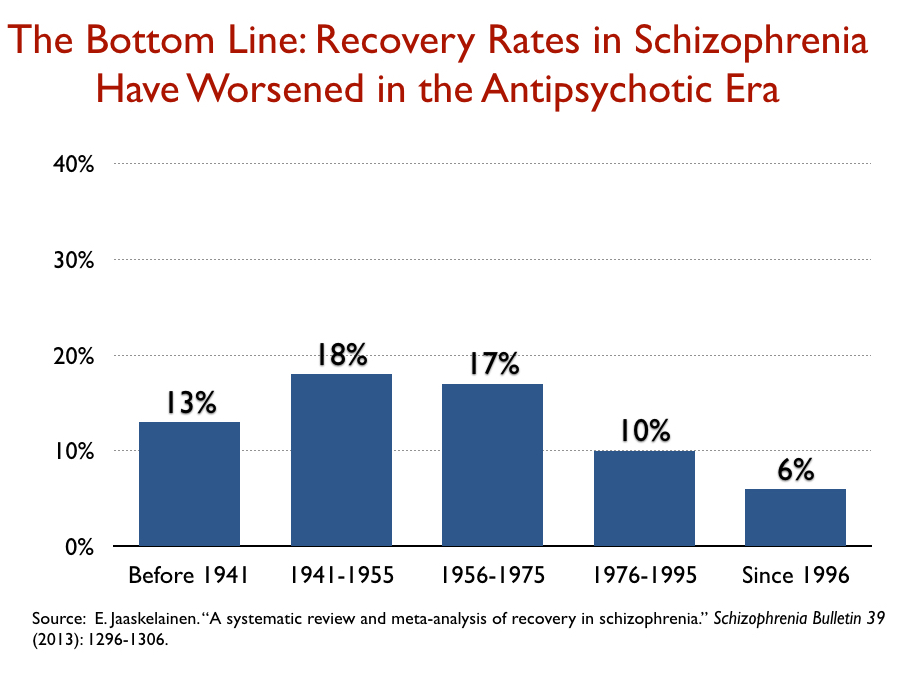

Next, I found a 1994 study by Ross Baldessarini and his colleagues at Harvard that determined that recovery rates for schizophrenia patients in modern times had declined over the past 15 years and were now no better than they had been in the first third of the 20th century, when water therapies and other strange somatic treatments were standard practices. This finding did not tell of a field that was making great progress in treating “schizophrenia.”

Finally, after the Globe series was published, I asked leading psychiatrists—and researchers at one of the pharmaceutical companies that had brought a new atypical antipsychotic to market—a simple question: could they point me to the research that had shown that schizophrenia patients actually suffered from dopamine hyperactivity, with this imbalance then fixed by antipsychotic drugs? Here is what I was told:

“Well, we didn’t actually find that.”

This was the “aha” moment that transformed my approach to reporting on psychiatry and its “science.” In my interviews for the Boston Globe series, I had been repeatedly told that antipsychotics fixed a dopamine imbalance in the brain and thus were “like insulin for diabetes.” Yet, now that I had asked to see the evidence for that claim, I was informed that “like insulin for diabetes” was just a metaphor, and that it was useful because it helped schizophrenia patients understand why they should take antipsychotics. And I immediately thought this: It’s not my job as a reporter to peddle a false story to the public so that schizophrenia patients will take their drugs. The WHO results also made me wonder whether there was something wrong with the claim that continual use of antipsychotics led to better outcomes for those diagnosed with schizophrenia.

At that point, I got a contract to write a book, titled Mad in America, and I did so with this plan in mind: I would tell of a history that could be found in the scientific literature. Rather than rely on interviews with experts in the field, I would rely on research that could be found on library shelves.

That book traced the history of the treatment of the “seriously mentally ill” from colonial times until today. The controversial part was the history I told about antipsychotic drugs.

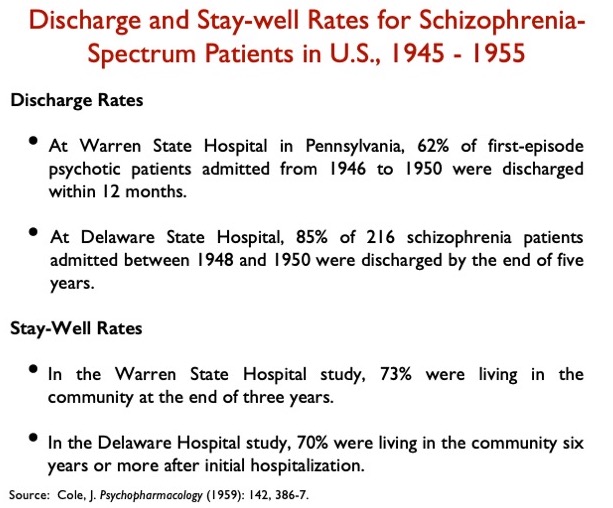

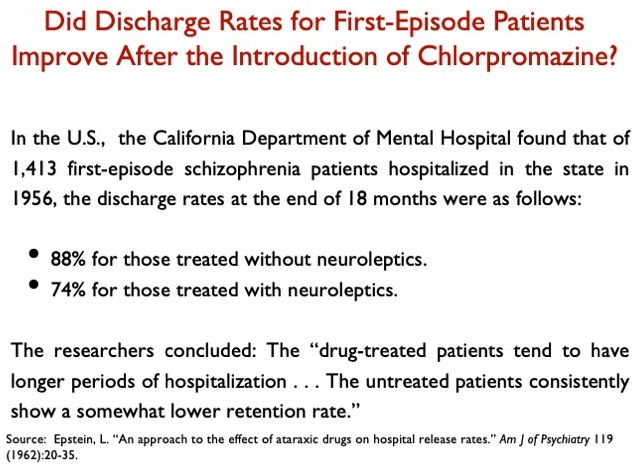

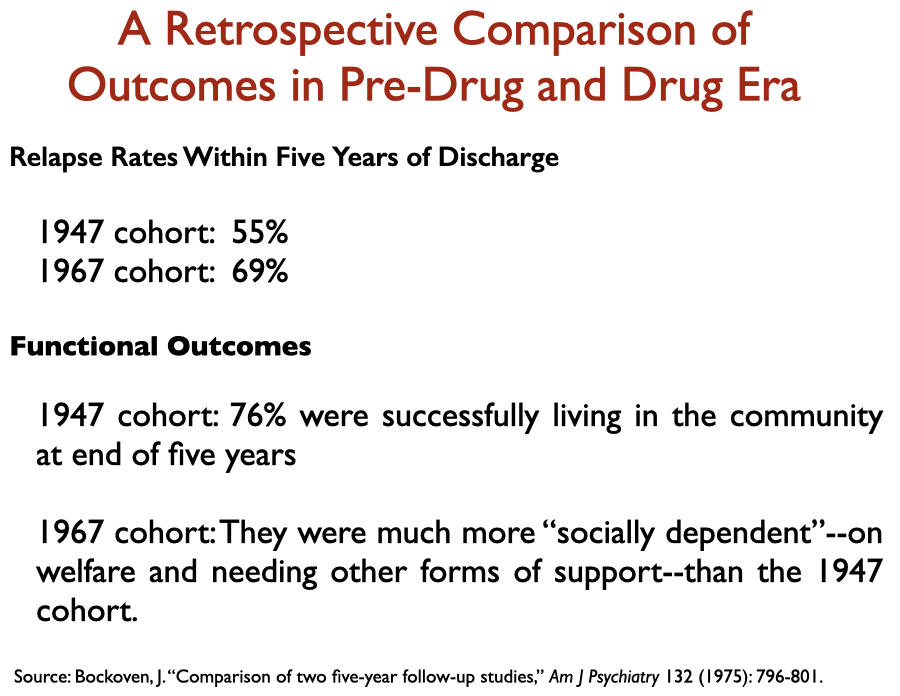

The conventional history of psychiatry tells of how the introduction of chlorpromazine into asylum medicine in the 1950s kicked off a “psychopharmacological” revolution, a great advance in care that made it possible for people diagnosed with schizophrenia to live in the community. However, the scientific literature told a different story. Chlorpromazine, which is remembered today as the first “antipsychotic,” was initially praised for providing a chemical lobotomy; the introduction of chlorpromazine didn’t, in fact, improve hospital discharge rates for first-episode schizophrenia patients; and a variety of studies in the 1960s and 1970s told of how it appeared that relapse rates—and functional outcomes—worsened with the introduction of these drugs.

Here is a sampling of such data that appears in the medical literature:

Then, there was this dark secret that could be found in the research literature: By the end of the 1970s, researchers had raised the possibility that antipsychotics induced a dopamine supersensitivity that made patients more biologically vulnerable to psychosis and thus increased the chronicity and severity of symptoms in a significant percentage of patients. The drugs also caused Parkinsonian symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and a host of other horrible side effects, all of which led Jonathan Cole, the long-time director of the NIMH Psychopharmacology Service Center, to co-author a 1976 paper titled “Maintenance Antipsychotic Therapy: Is The Cure Worse than the Disease?”

Finally, I turned my attention to the second-generation “atypical antipsychotics” that came to market in the mid-1990s. Zyprexa and Risperdal were being touted as breakthrough medications, more effective and safer than the first-generation antipsychotics, with breathless stories appearing in major newspapers telling of how schizophrenia patients were now going back to work like never before. I had obtained the FDA’s reviews of those two drugs through an FOIA request, and those reviews told of how the clinical trials of these two drugs had been biased by design against the first generation, and how there was no evidence they were any better or safer than the old ones. The one difference, the FDA reviewers said, was that the nature of the side effects with the newer drugs could be expected to differ, in many ways, from the side effects with the older drugs.

At the end of that book, I wrote briefly about what could be done to improve treatment of the “seriously mentally ill” in the United States. I concluded with this line:

“At the top of this wish list, though, would be a simple plea for honesty: Stop telling those diagnosed with schizophrenia that they suffer from too much dopamine or serotonin activity and that the drugs put those brain chemicals back into ‘balance.’ That whole spiel is a form of medical fraud, and it is impossible to imagine any other group of patients—ill, say, with cancer or cardiovascular disease—being deceived in this way.”

After that, I took a break from psychiatry. I wrote a history of the first scientific expedition from Europe to South America (The Mapmaker’s Wife), and a history of a racial massacre in Arkansas in 1919 and the legal struggle that it spawned that served as a foundation for the Civil Rights movement fostered through Supreme Court decisions (On the Laps of Gods). Then, in Anatomy of an Epidemic, I investigated this question: How do psychiatric drugs affect the long-term course of psychiatric disorders? What did a review of the scientific literature reveal?

This was a question that required a deep dive into the research literature. What long-term outcomes were reported for a major diagnostic category prior to the introduction of “psychiatric drugs”? When the drugs were introduced, did clinicians at that time notice any change in long-term course? What did longer-term studies reveal about the changing course? In longer-term studies that compared outcomes for medicated and unmedicated patients, which group had higher recovery rates? Did all these pieces of data piece together to paint a consistent, coherent picture?

With each class of drugs, the same bottom-line conclusion emerged: Psychiatric drugs worsened long-term outcomes compared to natural recovery rates. And at least a few researchers, confronted with data of this type, sought to provide a biological explanation for why antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines might have this negative long-term effect.

There was one aspect of turning to the research literature in this way that had its challenges. Much of the long-term research had been funded by the NIMH, and these studies were regularly authored by academic researchers who had ties to pharmaceutical companies and were known as prominent “thought leaders” in the field. The negative findings threatened psychiatry’s public story of great progress, and such findings wouldn’t be highlighted in the abstract, or else they would be explained away. The same was true in the discussion section of the articles. There was regularly this effort to spin the results so that the drugs wouldn’t be seen as doing harm, and as a result, I learned to focus on the data tables and graphics. What did the data say?

We founded Mad in America in January of 2012, and our science coverage was meant to continue the reporting that was present in those two books: we would provide a running account of studies that belie the common wisdom but are never promoted by psychiatry for that reason.

With this in mind, we set forth a template for reporting on research:

- We identify the authors, detail the study’s methodology and limitations, and report on the principal findings.

- We raise questions: What are the possible implications of the findings—why are the findings important?

- We put the findings into a broader context: Do the results from this one study fit within a larger body of related research? We provide links to earlier studies that provide this context.

- We assess the presence of spin: Is spin present in the article that is designed to protect the conventional wisdom?

In sum, our reporting on science isn’t meant to serve simply as a collection of reports on individual studies. We provide reviews that help readers see the “bigger picture” that exists in the research literature, and yet isn’t generally known. Indeed, if you go to our archive of science news for drugs, you’ll find reviews of more than 650 peer-reviewed articles, and as you peruse the headlines for these articles, you will immediately see that very little of this research is communicated to the public. I am quite certain there is no other media archive of drug findings like it anywhere else in the world.

Our Review of the JAMA Psychiatry “Viewpoint”

The principal findings

In their article titled “Success Rates in Psychiatry,” the authors, Kenneth Freedland and Charles Zorumski from Washington University School of Medicine, defined “successful outcomes” in this way:

“Successful outcomes include both the prevention of undesirable events, such as death and disability, and the achievement of desirable ones, such as remission.”

This is a definition that doesn’t just look at short-term RCTs as evidence of a treatment’s efficacy, but rather at a bigger picture: how does the treatment affect the patients’ lives and their ability to function over the long-term?

In other medical disciplines such as cardiology and cancer, the authors noted, researchers have been able to document how the introduction of new therapies decreased mortality rates. This is bottom-line data that tells of an improvement in “successful outcomes” for those diseases. But psychiatry, they wrote, does not have such “successful outcome” data.

“Despite advances in measurement-based psychiatric care, clinical [success rate] reporting systems do not exist for most psychiatric services. This applies to all psychiatric treatments including pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and neuromodulation.”

The fact that psychiatry has never reported on such success rates, they concluded, makes it “difficult to determine whether psychiatric treatment outcomes are improving over time, stagnating, or perhaps even regressing.”

Moreover, this is the very information that the public wants. “Patients with serious illnesses care about their chances of having successful treatment outcomes. They also expect to receive more effective treatments than the ones that were available to their parents or grandparents, and they hope that even more effective treatments will be available for their children and grandchildren.”

Hence, the principal elements summarized in our headline and subtitle:

Title: Jama Psychiatry: No Evidence that Psychiatric Treatments Produce “Successful Outcomes.”

Subtitle: In a viewpoint article in JAMA Psychiatry, researchers reveal that psychiatry is unable to demonstrate improving patient outcomes over time.

The implications

The authors stated that patients today want to know if treatments today are better than they were in the past, and that without success outcomes data, there is no way to know this. Our review turned that conclusion into a concrete question: Are outcomes today better than in the era of lobotomies, insulin coma therapies, and other harsh somatic treatments? Or better than they were in the early 1800s, when Quakers created moral therapy asylums in the United States? We raised the question, which was consonant with the authors’ discussion of how “success outcomes” data was necessary to make such assessments. It was an obvious question for us to ask.

The bigger picture

Although the authors state there is a lack of “success outcome” data for psychiatric treatments, there is in fact much data that is available that is relevant to this question. There is data that tells of rising disability rates due to mental disorders in the modern era. Standard mortality rates for schizophrenia and bipolar patients have worsened in the past 40 years. Long-term studies tell of higher recovery rates for schizophrenia patients off medication. There is evidence of many kinds that tells of how depression has been transformed from an episodic disorder into a chronic condition in the Prozac era. Public health data tells of a mental health crisis in our country today, despite the dramatic increase in the percentage of the population receiving treatment.

All of this tells of “psychiatric treatment outcomes” that are regressing. In our report, we briefly referred to several studies of this kind.

The spin

As our report noted, the authors wrote of how the assessment of “successful outcomes” is necessary to determine whether medical care in a discipline is improving. Given that psychiatry has not gathered “successful outcome” data, then it would logically follow that psychiatry cannot claim a record of improved outcomes. But having made this argument in the first two sections of their viewpoint, in the third section the authors pivoted in a way that made their paper palatable to the psychiatric profession. The head of the third section reads: Using Success Rate Data to Accelerate Progress.

With this pivot, the authors were fitting their “viewpoint” into the narrative of progress that psychiatry has told to itself and the public. This is a discipline that has made progress in its treatments of major disorders; what it needs to do now is develop systems that can measure this progress, which in turn will spur further progress. They wrote, in conclusion:

“The development of well-designed, sustainable success rate data systems would facilitate this kind of progress and help ensure that psychiatric treatment outcomes continue to improve in the decades ahead.”

This “continue to improve” statement doesn’t logically follow from their conclusion that psychiatry lacks “success outcomes” data that would enable the field to assess whether outcomes are improving, stagnating, or regressing over time. And so, in our report, we called out this spin.

The authors’ conclusion, we wrote, “suggests that psychiatric treatments have been shown in the past to lead to successful outcomes; yet, as they write here, there is no data on whether medical treatments for psychiatric disorders, past or present, produce that bottom-line result.”

Aftab’s criticism

In essence, Aftab’s criticism of our report boils down to this: He wanted us to report on the paper without evaluating the implications of the authors’ assertion that psychiatry hasn’t gathered any data on “successful outcomes;” without linking to data that told of poor outcomes with psychiatric drug treatments today; and without pointing out the spin in the last section of the viewpoint.

Here is his take:

This is a story of progress

He first summarizes the key points of the JAMA Psychiatry “viewpoint,” and says that he agrees with the authors. By charting “success rates,” he concludes, “we’ll be able to track the progress we’ve made, and we’ll have a better idea of where progress is needed.”

How dare we question this story of progress

After criticizing our headline, Aftab takes issue with our questioning—based on the absence of success outcomes data—of whether there is evidence that present treatments produce better outcomes than in the pre-drug era, or during the early 1800s, when the Quakers introduced moral therapy. He writes:

“This is a pretty wild extrapolation! A call for implementation of temporal tracking of psychiatric success rates is being interpreted here to suggest that we cannot say with any confidence that outcomes of psychiatric care are better now than they were in the 1800s. Just because we haven’t tracked temporal outcomes in the specific manner suggested by Freedland and Zorumsky doesn’t mean that we cannot make reasonable inferences from existing RCTS, observational data and clinical experience. Not only do we have multiple treatment modalities (pharmacotherapies, psychotherapies, neurostimulation, lifestyle modifications, community services, etc.) and multiple treatments within each modality that have demonstrated efficacy in RCTS, we can combine these treatments as well as use them sequentially to increase response and remission rates. This is not being disputed by Freedland and Zorumski, who state “stepwise approaches can produce cumulative success rates that are considerably higher than their constituent ‘specific success rates’ [for each treatment]and cite the results of STAR*D in support.”

Studies we cited that tell of treatments that worsen outcomes are not to be taken seriously

Aftab writes: “There is of course no acknowledgement to the casual reader that these assertions presented as facts here are highly controversial claims with little acceptance in the scientific community.”

Let’s Go to the Scientific Literature

Aftab’s criticism of our reporting illuminates a fundamental question: Should society consider psychiatry to be a faithful recorder of its own scientific history, as it tells of a history of progress in the field? Or is there a gap between that public story of progress and the history that is told in the research literature, which is the very belief that has animated my reporting on psychiatry for the past 25 years, and was a motivation for founding Mad in America and is present in our mission statement?

We could of course cite the chemical imbalance story as illustrative of this gap, but let’s keep it within the confines of this JAMA Psychiatry “viewpoint” on “Successful Outcomes” and Aftab’s criticism of our report.

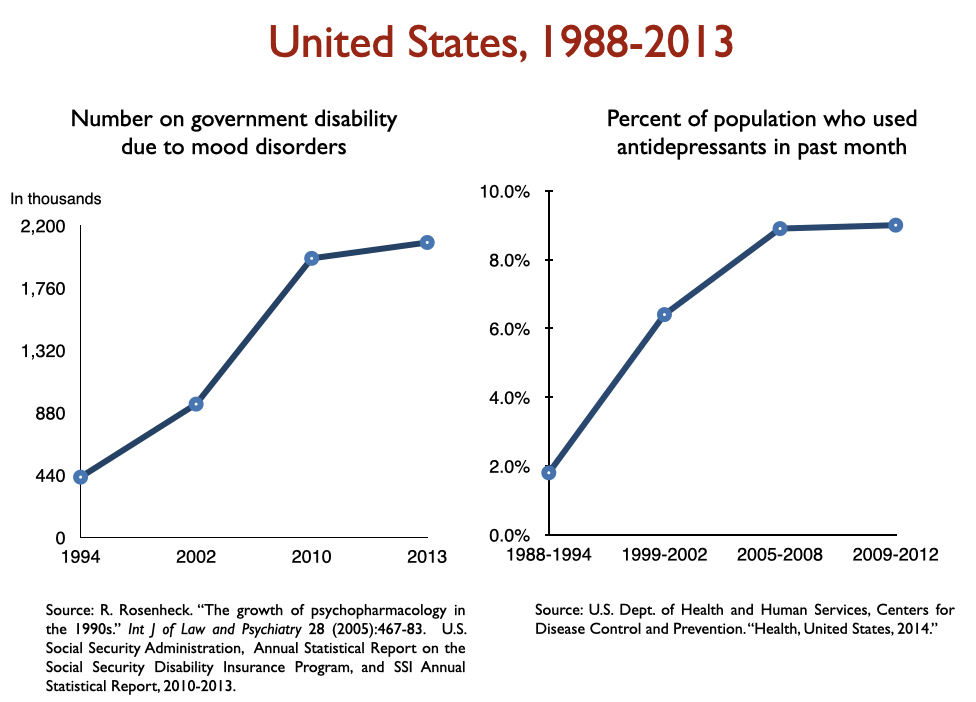

Disability due to mood disorders

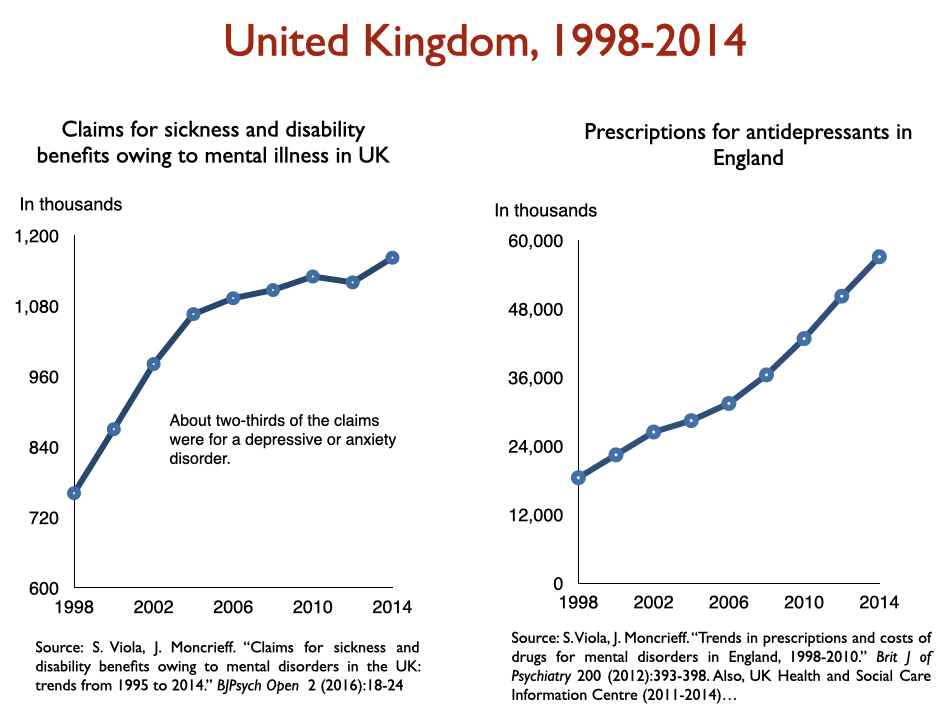

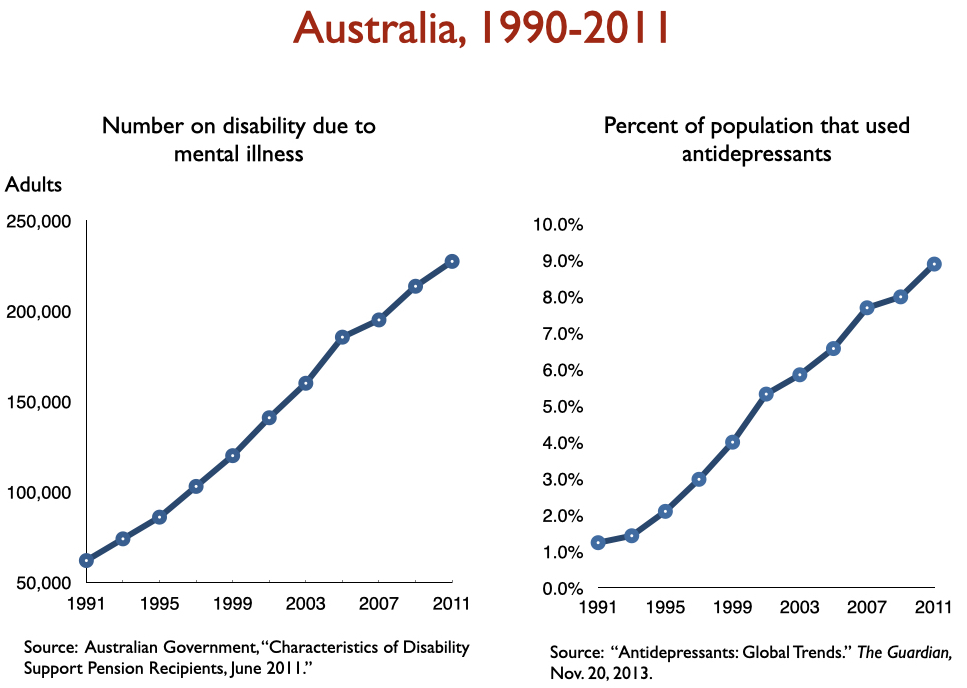

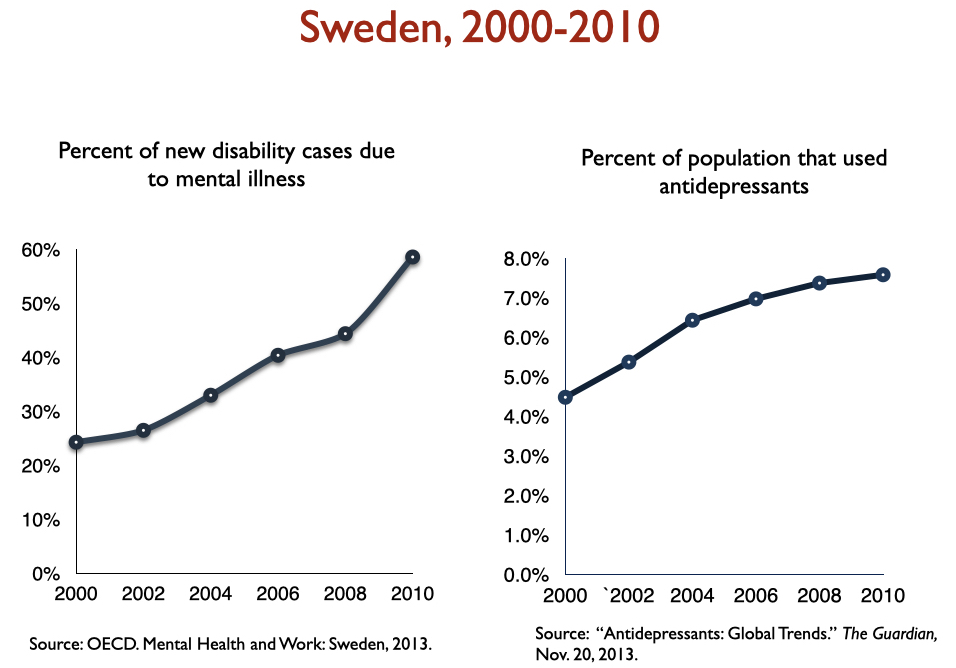

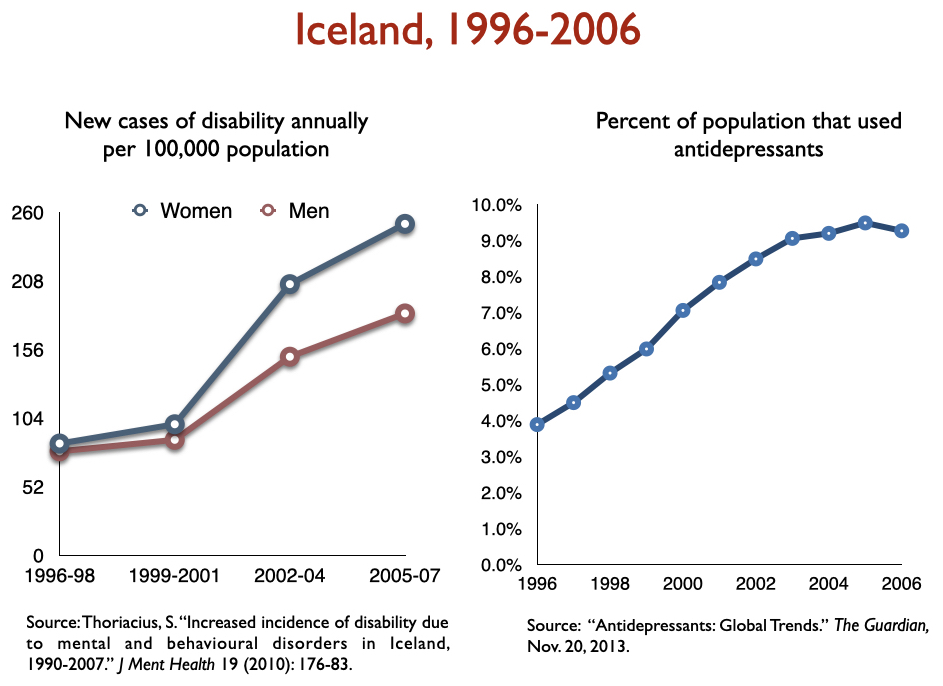

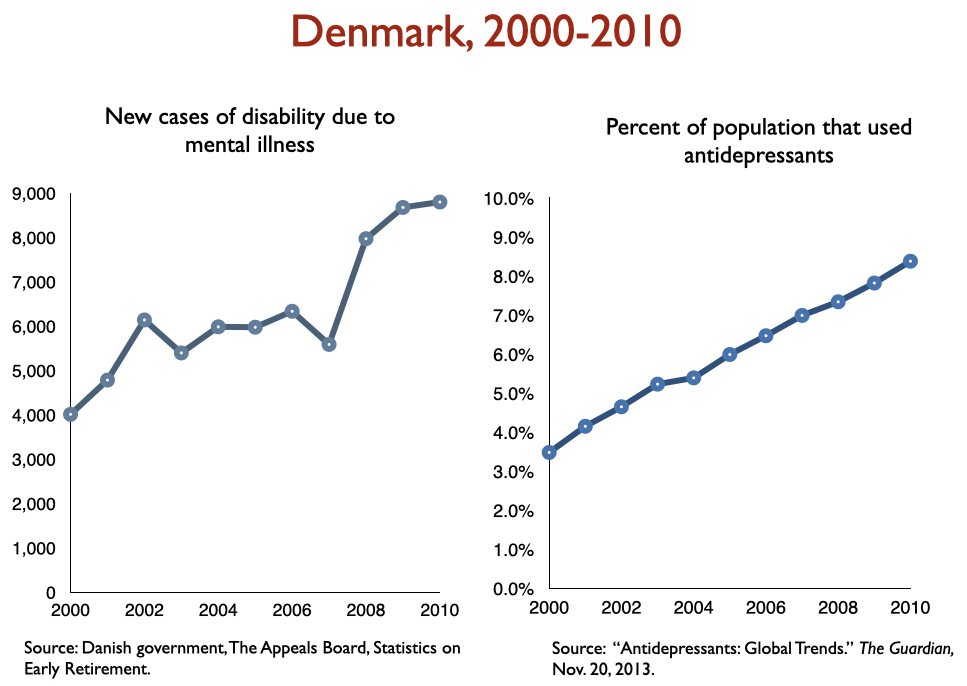

Freedland and Zorumski state that “successful outcomes” data should consider such outcomes as disability and mortality rates. Okay, let’s look at disability rates due to mood disorders following the introduction of SSRIs, starting with Prozac in 1988. Here is the data on disability I prepared when I was asked to present to the UK Parliament on this topic in 2017:

In sum, disability rates notably climbed in country after country with increased use of antidepressants.

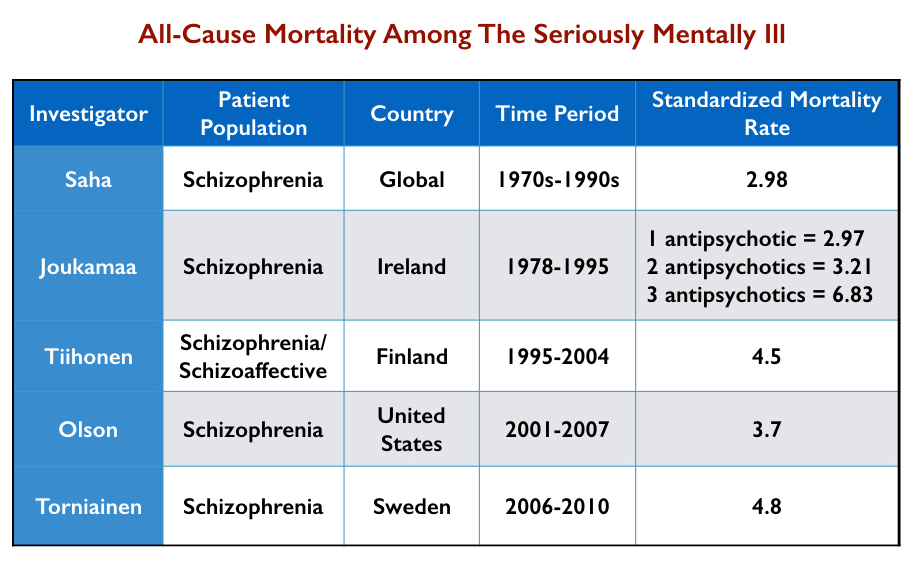

Standard mortality rates for psychiatric patients

Standard mortality rates (SMRs) tell of the higher mortality rates for patient groups compared to the general population. For instance, a standard mortality rate of 2 for schizophrenia patients means that they are twice as likely to die over a set period than the general population. SMRs for schizophrenia and bipolar patients have worsened over the last 50 years.

In 2007, Australian researchers conducted a systematic review of published reports of mortality rates of schizophrenia patients in 25 nations. They found that the SMRs for “all-cause mortality” rose from 1.84 in the 1970s to 2.98 in the 1980s to 3.20 in the 1990s.

Here is a summary of the increase in SMRs for the seriously mentally ill from various studies:

In 2017, UK investigators reported that the SMR for bipolar patients had risen steadily from 2000 to 2014, increasing by 0.14 per year, while the SMR for schizophrenia patients had increased gradually from 2000 to 2010 (0.11 per year) and then more rapidly from 2010 to 2014 (0.34 per year.) “The mortality gap between individuals with bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, and the general population, is widening,” they wrote.

Long-term use of antidepressants has also been found to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

The long-term course of depression

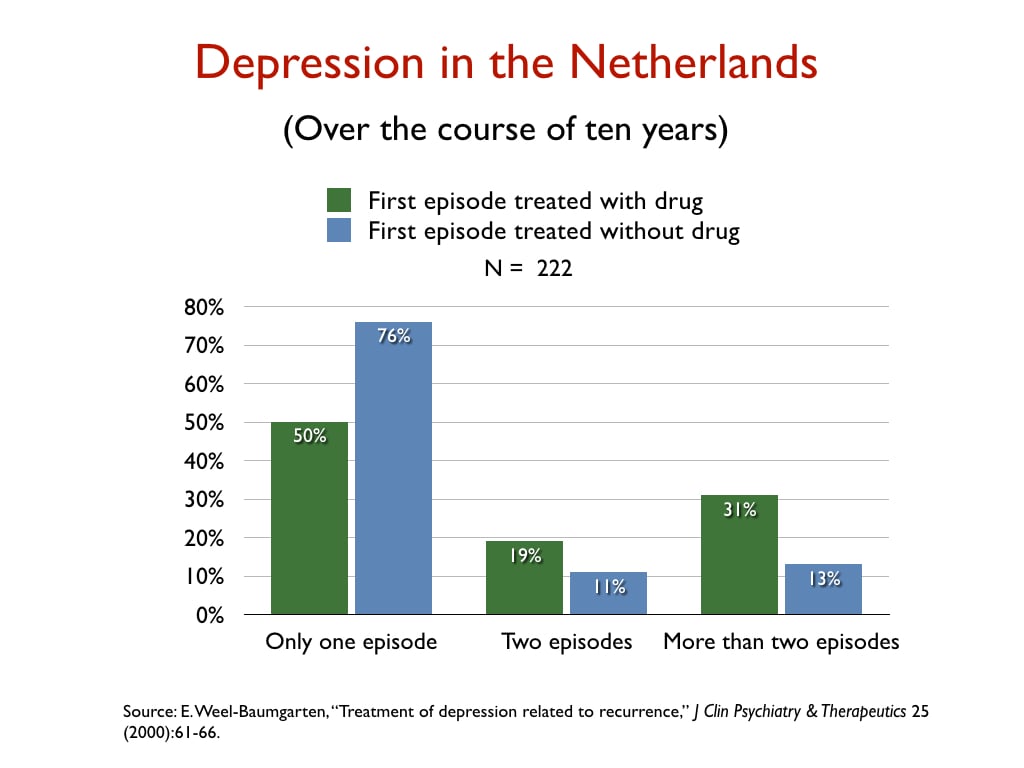

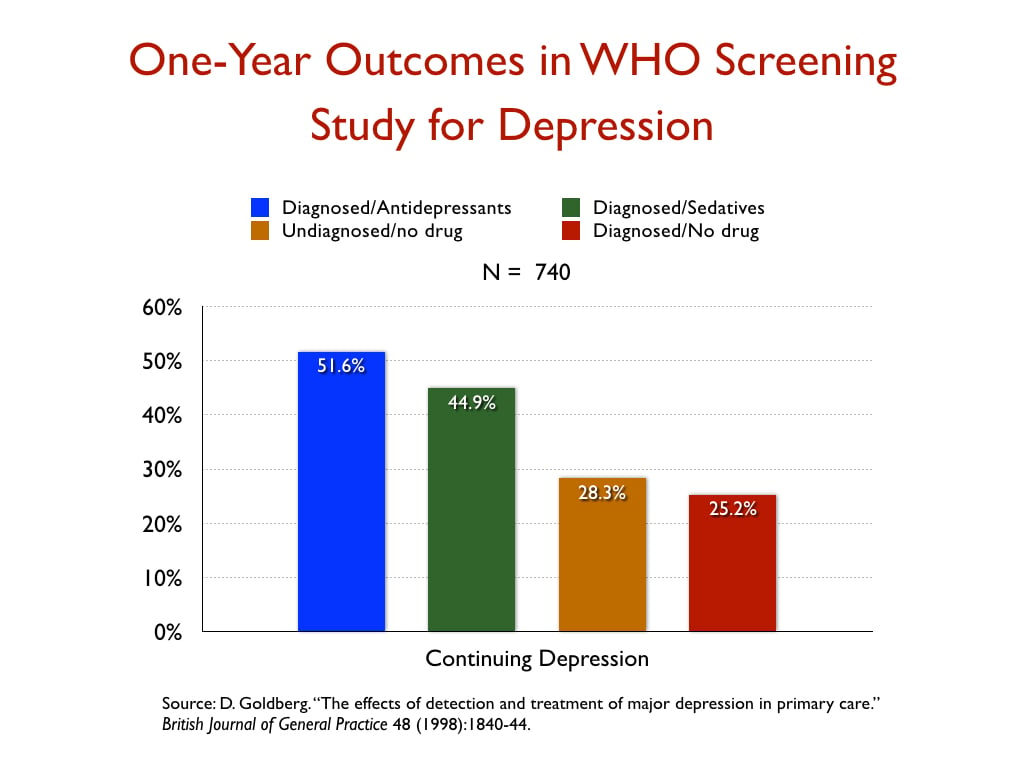

There is abundant evidence that depression has been transformed from an episodic disorder into a chronic condition in the antidepressant era. Here is a sampling of graphics from studies that assessed longer-term outcomes for depressed patients treated with and without antidepressants.

In a retrospective study of the 10-year outcomes of 222 people who had suffered a first episode of depression, Dutch researchers reported that 76% of those not treated with an antidepressant recovered and never relapsed, versus 50% of those initially prescribed an antidepressant.

In a WHO study designed to assess the merits of screening for depression, which was conducted in 15 cities around the world, the patients who were diagnosed by their GPs and treated with an antidepressant were twice as likely to be depressed at the end of one year as those who weren’t diagnosed and treated, even though their baseline depression scores were nearly the same.

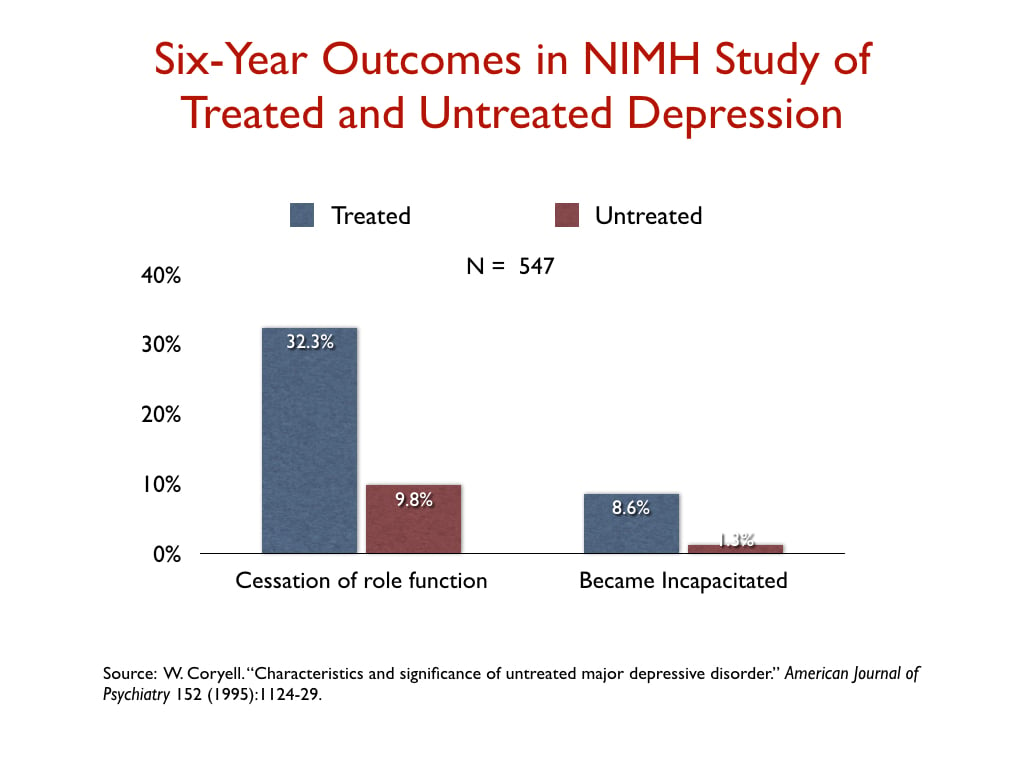

In a NIMH-funded study, investigators assessed the six-year “naturalistic” outcomes of 547 people who suffered a bout of depression, and found that those who were treated for the illness were three times more likely than the untreated group to suffer a “cessation” of their principal social role, and nearly seven times more likely to become incapacitated.

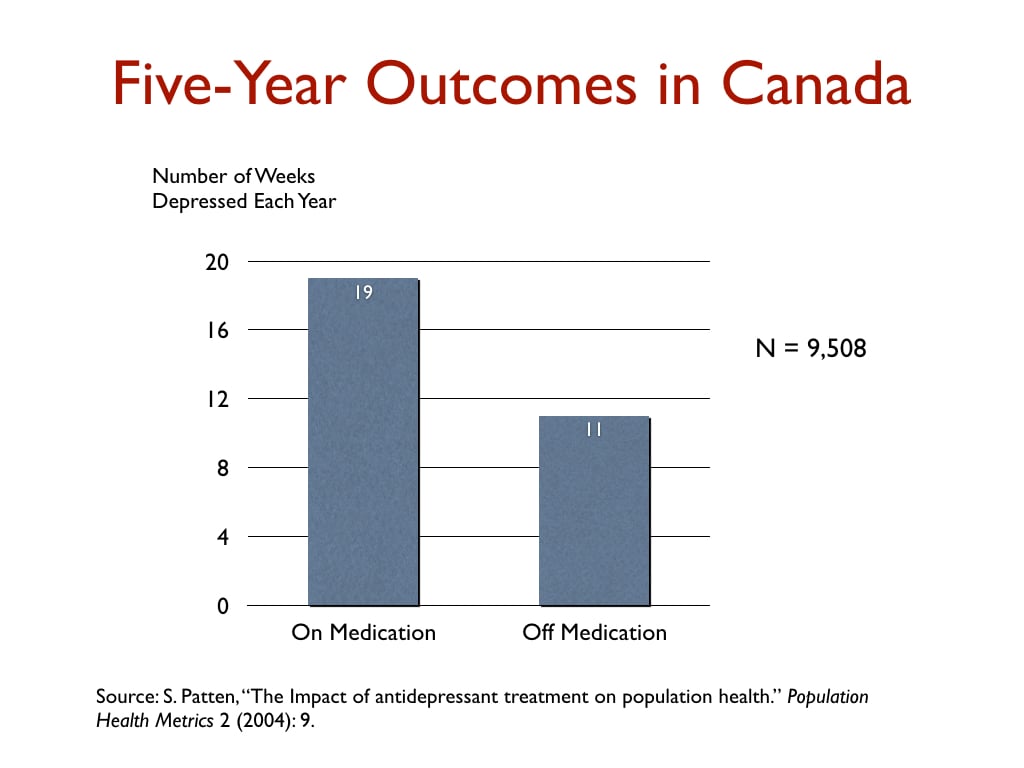

In a Canadian study that charted outcomes for 9,508 depressed patients for five years, those taking antidepressants were depressed on average 19 weeks per year, versus 11 weeks for those not taking antidepressants.

In a Canadian study that charted outcomes for 9,508 depressed patients for five years, those taking antidepressants were depressed on average 19 weeks per year, versus 11 weeks for those not taking antidepressants.

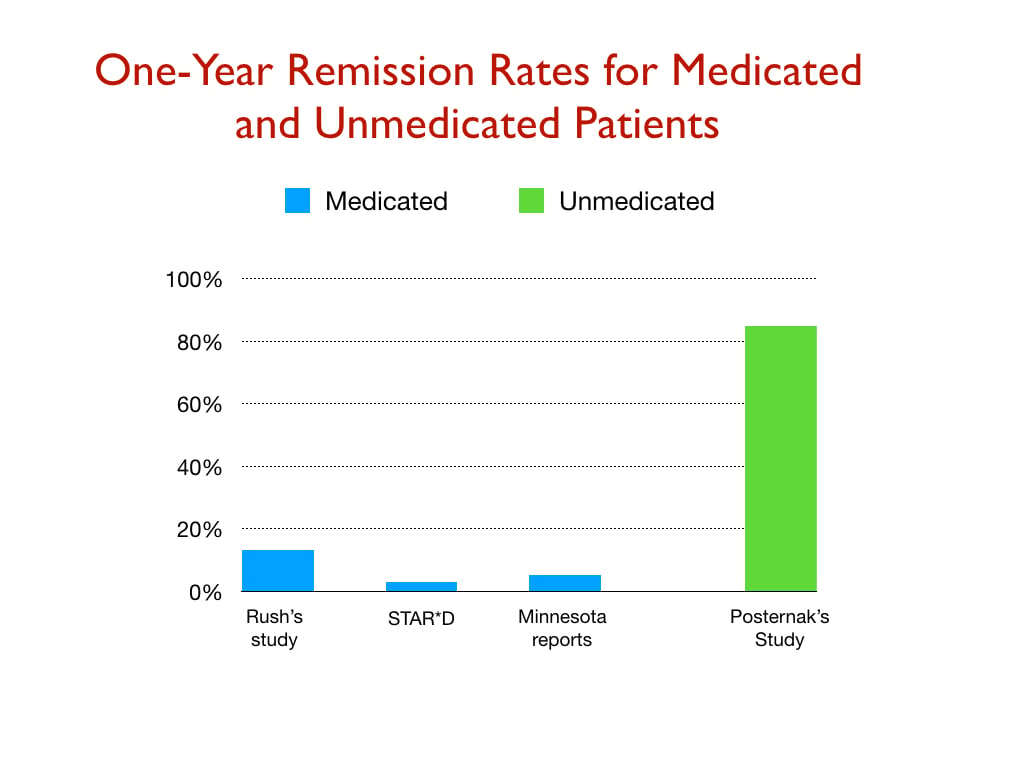

The next graphic provides a comparison of one-year remission rates from three studies of real-world patients (Rush study; STAR*D study; and depressed patients in Minnesota), and a NIMH-funded study of unmedicated patients.

The next graphic provides a comparison of one-year remission rates from three studies of real-world patients (Rush study; STAR*D study; and depressed patients in Minnesota), and a NIMH-funded study of unmedicated patients.

More recently, a study that charted outcomes for depressed patients at nine years, and a second one that did so for 30 years, found worse outcomes for those who took antidepressants for long periods of time.

More recently, a study that charted outcomes for depressed patients at nine years, and a second one that did so for 30 years, found worse outcomes for those who took antidepressants for long periods of time.

Recovery rates for schizophrenia patients have declined

The best long-term prospective study of schizophrenia outcomes was the NIMH-funded Chicago Follow-up Study conducted by Martin Harrow and Thomas Jobe. They found that recovery rates at 15 years for those who had stopped taking their antipsychotic medication were eight times higher than for those on antipsychotic medication. In a 2018 paper, Harrow and Jobe noted there were now seven other studies “assessing whether schizophrenia patients improve when treated longer than two-three years with antipsychotic medication . . . These research programs included samples studied from 7 to 20 years. Unlike short-term studies, none of them showed positive long-term results” for the medicated patients.

As noted earlier, I stumbled upon a 1994 paper by Ross Baldessarini that told of how recovery rates for schizophrenia patients had declined from 1976 to 1995. A 2013 systematic review of recovery rates after the atypical antipsychotics came to market in the 1990s found that recovery rates continued their decline, and since 1996 are now lower than they were in the first third of the 20th century.

Outcomes with moral treatment

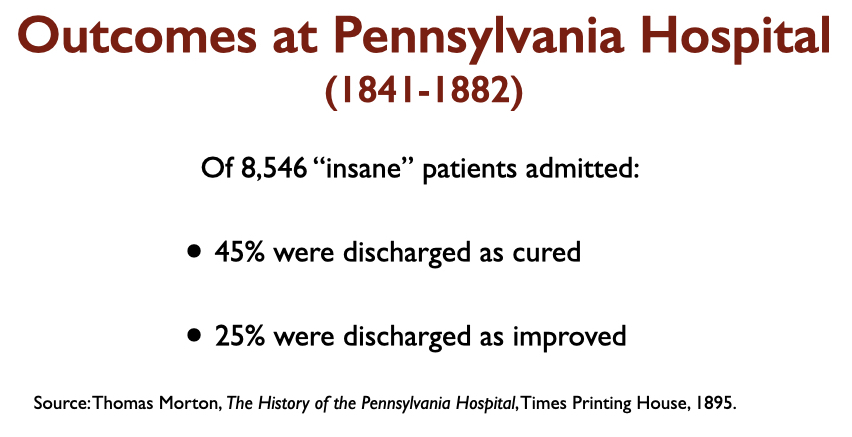

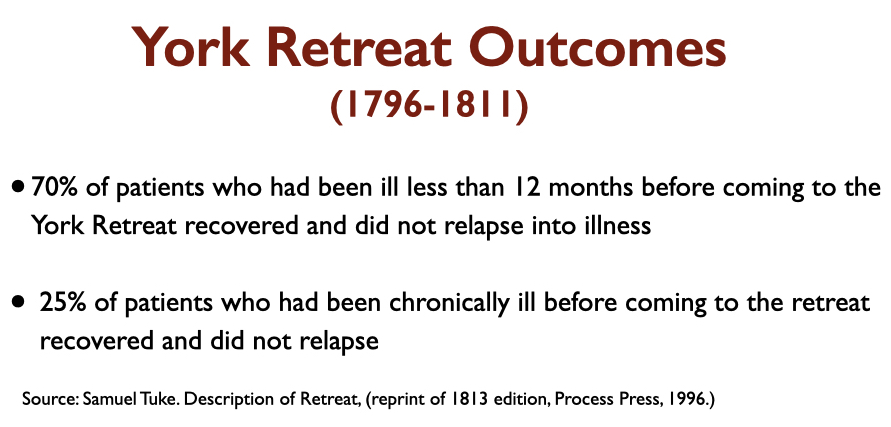

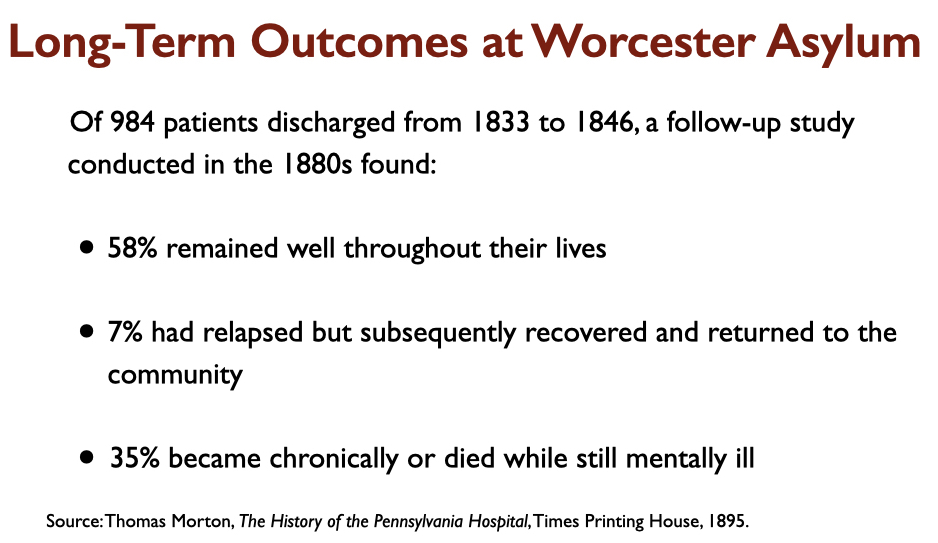

Case reports of the “insane” patients admitted to moral therapy asylums in the first half of the 19th century tell of seriously disturbed patients. Here are the outcomes reported at that time from three prominent “moral treatment” asylums, which are far better than the 6% recovery rate for schizophrenia patients today.

STAR*D as Evidence of “Cumulative Success Rates”

STAR*D as Evidence of “Cumulative Success Rates”

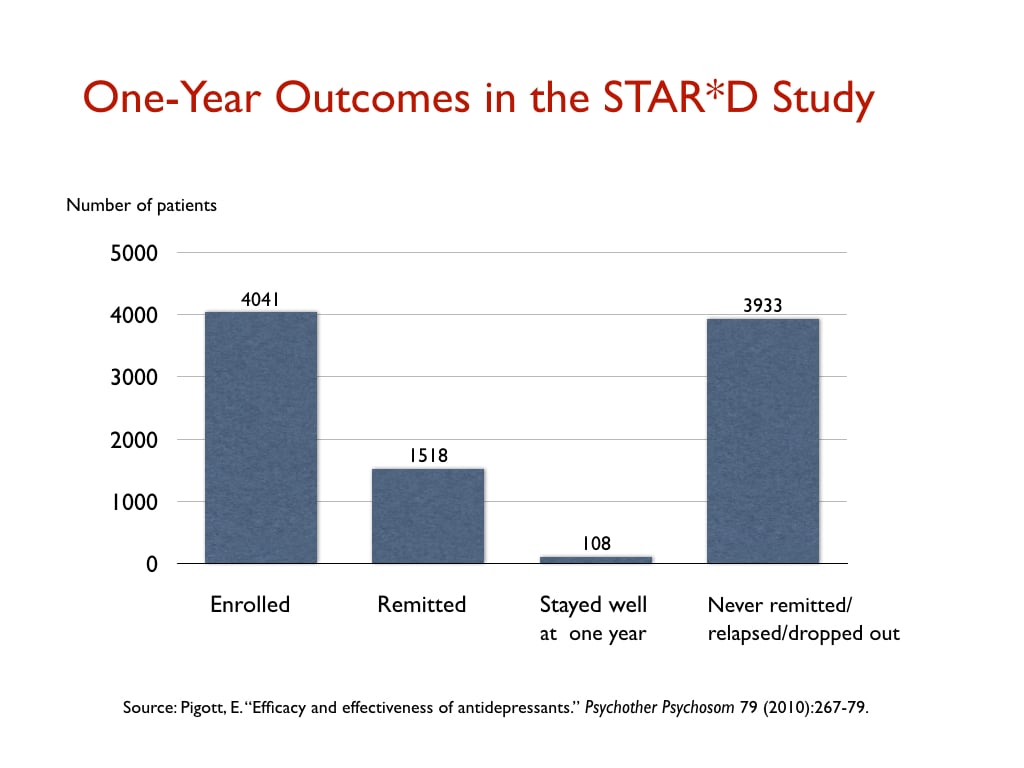

In their JAMA Psychiatry paper, the authors write that psychiatry should track “cumulative success rates,” meaning the clinical outcomes for patients who may be treated with multiple forms of treatment and trials on various psychiatric drugs (as opposed to the effectiveness of a single treatment). They cite the STAR*D study as an example of a study that shows that the cumulative success rate may be much higher than “success outcomes” with a single form of treatment. In his blog, Aftab refers to this passage and the STAR*D study as evidence of psychiatry’s progress in producing good outcomes.

The STAR*D investigators, in their reports on remission rates in the trial, which was the largest antidepressant trial ever conducted, did claim such success. There were 4,041 “real-world” patients enrolled into the trial, and if they didn’t remit on a first antidepressant, they could be switched to a different antidepressant and also receive psychotherapy, and ultimately they could be given four different concoctions of treatment to see if they could find one that led to a remission of their depression. The STAR*D investigators reported that at the end of the four steps, the cumulative remission rate was 67%.

That finding is still cited today by the mainstream media as evidence of the effectiveness of antidepressants, and they do so after speaking with experts in the field. The New York Times, for instance, cited this finding to reassure readers after Joanna Moncrieff and colleagues reported in 2022 that there was no evidence for the low serotonin theory of depression. There was no need to worry; the STAR*D study showed that antidepressants fully chased away depression in two-thirds of patients.

As Aftab surely knows, nothing like that actually happened in the STAR*D study. Indeed, this study stands out as the best example of how psychiatry, in its communications to the public, cannot be trusted. The STAR*D study is a story of scientific fraud.

The investigators went through any number of machinations—deviations from the protocol—to produce an inflated remission rate. Patients who dropped out early and should have been counted as treatment failures weren’t counted. The investigators switched from the depression rating scale that was supposed to be used to evaluate outcomes (the HAM*D scale) to a secondary one (QIDS-SR scale) that produced higher rates. They then calculated a “theoretical” remission rate: If all patients had stayed in the trial throughout the four steps, rather than progressively dropping out during the study while still depressed, and if these drop-outs had remitted at the same rate as those who stayed in the trial, then two-thirds would have eventually gotten well. This calculation alone turned 606 treatment failures into treatment successes.

A team of independent researchers subsequently obtained access to the case report data, and they found that the actual “remission” rate in the study was 26%, rather than the 67% rate the STAR*D investigators promoted to the public (which is still promoted to the public)! Aftab, in his blog criticizing us, similarly cites this fraudulent study as evidence of psychiatry’s cumulative prowess in treating depression.

But even this isn’t the end of the duplicitous aspect of the STAR*D study. The purpose of the study, which was touted by the NIMH before the results came in as the research that should guide clinical practice, was to see if psychiatry, with its various treatments, could get patients well and keep them well. In one of their reports, the STAR*D investigators did publish a table on the one-year outcomes, but it was nearly impossible to decipher, and they did not detail the one-year results in their written text. However, psychologists Ed Pigott and Allan Leventhal subsequently determined that the one-year table told of how only 108 patients—out of the 4,041 who had been enrolled—remitted and then stayed well and in the trial to its one-year conclusion.

Here is a graphic of the one-year results from the STAR*D study:

The Scientific Literature Has Spoken

As can be seen from even this brief review of the research literature, it doesn’t support a narrative of therapeutic progress, of psychiatric treatments that have “continued” to improve over time. Aftab, in his criticism of our science coverage, asserted that there was plenty of evidence from RCTs and such that told of the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments and that it was ridiculous to think that outcomes were not much better than they had been in the early 1800s with moral therapy. He described our links to studies telling of how antipsychotics and antidepressants worsened long-term outcomes as “highly controversial claims with little acceptance in the scientific community.”

I don’t know about acceptance within the “scientific community,” but I do agree that within the psychiatric community, this research is mostly derided, ignored, and kept from the public. The reason is that this research, which is their research and voluminous in kind, belies the narrative of progress that psychiatry has told to itself and to the public, and in order to maintain that narrative, it has to keep such research hidden from the public, or to dismiss it as insignificant. When MIA continues to make it known to the public through our science coverage, the same impulse of institutional self-preservation takes hold. We must be portrayed as “untrustworthy”—it’s the only way that psychiatry can protect the narrative it holds so dear.

And that’s what Aftab’s blog, when it is deconstructed, makes clear.

Aftab’s the perfect front man for a “profession” that sees its days are numbered, but his carefully modulated hissy fits are a testament to MIA’s integrity. He sees the writing on the wall and it has him running scared…

Report comment

Aftab needs to realize he can’t outrun the truth.

Report comment

Correction: Aftab needs to realize he can’t outtalk the truth.

Report comment

Correction: Aftab needs to realize he can’t out-philosophize the truth.

Report comment

Aftab needs to check his calendar: it’s 2023, not 1983, so controlling the narrative’s a thing of the past, thanks to the internet.

Report comment

What Aftab fails to see is this:

Psychiatry will eventually collapse under the weight of its own lies—with or without MIA.

Report comment

If Aftab felt secure in his convictions, he wouldn’t bother with MIA —

Report comment

Thank you Robert Whitaker for this important, meticulous, evidence based deconstruction. (Retired Physician – not “Casual Reader”.)

Report comment

My question for Awais Aftab is this: Is there ANY evidence at all that would convince you that psychiatry is a failed paradigm of care?

If you, Awais Aftab, cannot answer that question, you are not a scientist but a theologian or a propagandist.

For any legitimate scientist, what Robert Whitaker has discussed in this article would get them to at least CONSIDER THE POSSIBILITY that psychiatry is a failed paradigm of care, but if you, Awais Aftab, cannot even consider the possibility, then you are not a scientist but a theologian or a propagandist.

Robert Whitaker writes: “Aftab has staked out a position as being open-minded to critiques of psychiatry, and that is a public stance that makes him particularly valuable to his profession. He can serve as a defender of psychiatry against critiques that are truly threatening, and his criticisms will be seen as coming from someone who is open-minded about psychiatry’s flaws.”

This analysis of Awais Aftab’s role rings true to me. Does Awais Aftab at least CONSIDER THE POSSIBILITY that this is his role?

Report comment

It is wrong to say that anyone who is a theologian necessarily doesn’t consider evidence contrary to his beliefs. In fact, I know of many theologians and philosophers that do consider evidence to their being wrong, but who just aren’t convinced by such evidence and believe theism has a greater explanatory power. I wouldn’t call myself a theologian, but I am religious and I do consider ideas contrary to mine. Also, for that matter, I have heard of many non-religious people being asked this exact same question of yours – “Is that any evidence at all that would lead you to belief?” – and not being able to answer it.

Report comment

Believe this:

Psychiatry has no facts to back up its claims, by god.

Report comment

And psychiatry has no answers to explain that either.

Report comment

As an atheist I would reconsider my religious belief if adequate evidence was presented to me that there is a god: e.g., that a representative (another Jesus, for example) performed miracles in front of me, such as, raising the dead or other miracle(s) to be negotiated. I have discussed this with a couple of religious people and their reaction was that god doesn’t need to satisfy me, but beyond that couldn’t provide any advice about how else I could be convinced that they are correct and god exists. To me, this is similar to the psychiatric position about their pathology dsm belief system: that any dissenters/heretics and other non-believers must conform to what psychiatrists and other medically minded people consider adequate proof. No thanks.

Report comment

Marx is known for saying that religion is the opium of the masses. And psychiatry is today’s opium of the masses. And I doubt psychiatry has any “evidence” that it hasn’t pulled out of its collective asses.

Report comment

I think Aftab wears two hats at the same time: drug-pushing theologian AND drug-pushing propagandist.

Report comment

Aftab’s a politician, more than anything else, because psychiatry is politics, more than anything else.

And if that were not the case, there’d be no cause for argument.

Report comment

Correction: psychiatry is a religion more than anything else, because it believes in magical thinking.

Report comment

Definition for Magical Thinking: believing that genetics explains psychic suffering

Report comment

But like all politicians, Aftab’s greatest strength lies in talking out of both sides of his mouth.

Report comment

The Mental Health Movement (MHM) has long been spear-headed by psychiatry, which claims to be a legitimate medical specialty. The major claim of the MHM is that there are two radically different types of people, the mentally healthy and the mentally ill. The corollary to this premise is that the mentally healthy are superior and the mentally ill are inferior and must not be tolerated. (The MHM is a form of biological determinism, whose major historical example is perhaps eugenics.)

There are two methods to accomplish this goal.

The first is by propaganda to get people to voluntarily comply with the dictates of psychiatry.

The second is to get people to comply involuntarily by coercion and/or outright force.

Robert Whitaker has carefully dismantled the standard Whig history of psychiatry which runs like this: Yes, things were awful in the bad old days when we didn’t realize that the mentally ill suffered from chemical imbalances and unrecognized brain diseases. Just as allopathic doctors resorted to unproven and unscientific methods such as blood letting prior to the germ theory of disease discovered in the late 1800s, psychiatry engaged in all kinds of ignorant treatments until the discovery of the chemical imbalance theory.

But psychiatry had its own “revolution” in the 1950s, with drugs producing miraculous cures and emptying the state mental hospitals and making it possible for patients to live and succeed in the community.

In fact, mental hospitals are still deserving of the “snake pit” moniker. But there are more of them now with locked psychiatric wards in hospitals and crisis and suicide hotlines that can be used as a direct conduit into these prisons.

When Thomas Szasz first started criticizing “The Myth of Mental Illness” in the 1960s, he made a clear distinction between voluntary psychiatric treatment, which he favored, and involuntary treatment, which he criticized. In later years he abandoned the distinction because nearly every psychiatric encounter held out the very real possibility of coercive and/or forced treatment under state and federal laws.

Even your nice psychotherapist is required by law to break confidence and report you to the authorities if they suspect several types of actual or potential behavior such as “harm to self or others.”

Whitaker is right to conclude that psychiatric “research, which is their research and voluminous in kind, belies the narrative of progress that psychiatry has told to itself and to the public, and in order to maintain that narrative, it has to keep such research hidden from the public, or to dismiss it as insignificant.”

Report comment

First, the original MIA review by Peter Simons was excellent.

Second, in my opinion, mainstream psychiatry’s attitude is that it is impolite to make a big deal of this study, it should be swept under the rug like any other contrary to the prevailing narrative of its vast success, and MIA’s big transgression was bringing it to public attention.

(The recent Moncrieff et al. study nailing up the coffin of “serotonin deficiency” received likewise paradoxical outcry from psychiatry as, while quite dry, it was uncompromising and did not contribute to the credibility of the profession.)

From his point of view, Awais Aftab was alarmed at the incivility of MIA’s public display of psychiatry’s dirty linen. Savagery! He tends call for civility, to allow psychiatry to do its undetectable, invisible work of transformation (or not) out of the public eye, and cooperate in maintaining the reputation of the specialty as well as the public’s confidence. Maintaining status is the point, not science, historical record, or improving patient outcomes.

Report comment

Awais Aftab‘s beliefs fit in with mainstream medicine with its dependence on Big Pharma and its reliance on experts who have extensive conflicts of interest. Aftab insists that the JAMA article does not say there is no proof of psychiatric efficacy, just that psychiatry has not done a good job of tracking these successes. He says that looking at the totality of evidence people are helped by psychiatric treatment. This has not been well documented, he argues, because it is difficult to prove that using a succession of treatments over time results in improvements. He ignores evidence to the contrary.

Like Aftab, many physicians ignore or are unaware of evidence that their treatments not only won’t help but may even harm. Examples are abundant. Telling a healthy woman with moderately elevated cholesterol to take statins is just one small example.

My point, which I’ve made before, is that psychiatric malfeasance is part of a general problem in health care.

Report comment

For a REAL scientist, failure to prove efficacy leads to the conclusion of “no efficacy.” The “null hypothesis” is assumed true until proven false. So Atfab is talking through his hat, but it seems that’s the only way to justify continuing to prescribe these “treatments” to innocent patients who don’t know any better.

Report comment

The null hypothesis , which only applies to a particular study, does show no efficacy. But American medicine is filled with treatments that have not been proven through believable blinded randomized controlled trials. Physicians base a lot of their treatments on their experience, what other physicians are doing, poorly done studies and so on. Aftab, is doing nothing different than what is done by many physicians in other fields when he says that looking at the totality of evidence psychiatric treatment works. I don’t buy his argument although I’m sure the authors of the JAMA study would agree with him. Robert Whitaker gives an excellent summary of why his position is wrong.

Report comment

Very well put. The biggest difference in psychiatry is that psychiatrists can seriously make things up out of whole cloth and use “reference to authority” to “prove” they are right, since there are no actual criteria for success. As much as it may not be proven that reducing cholesterol levels has any positive effect on frequency or heart attacks or life expectancy, at least the “treatments” DO have to reduce cholesterol numbers. There’s no such measurement in psychiatry, so they can REALLY go wild with their claims, as soon as anyone believes their bogus “diagnoses” are real.

Report comment

Or their half-cocked “genetics” theory.

Report comment

“psychiatrists can seriously make things up out of whole cloth and use “reference to authority” to “prove” they are right, since there are no actual criteria for success.”

Fails Carl Sagan’s Baloney Test Kit miserably. Passes the Fuhrerprinzip though…… der Fuhrer hat immer rescht. Which should be a worry but …….

With regards Aftab, I heard from a Hadith last week that the signs of a hypocrite are three; They lie when they speak, they make promises they don’t keep, and they betray.

What bigger betrayal can there be to a ‘patient’ than to lie to them about a ‘chemical imbalance’, and promise them there are ‘treatments’ available that work?

Still, wish for your brother what you would wish for yourself.

Report comment

Quite a strange place to wear a hat.

Report comment

Very well said. Thanks Steve!

Report comment

Here’s Aftab’s idea of progress:

1. More diagnoses

2. More drugs

3. Less dissenting opinion

Report comment

And dispensing an endless supply of cognitive dissonance.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Someone needs to ask Aftab about the philosophy of bait and switch.

Definition for Bait and Switch: Fraudulent or deceptive practice.

The ploy of offering a person something desirable to gain favor (such as political support), then thwarting expectations with something less desirable.

Report comment

More on Bait and Switch:

1. Psychiatry promises relief from pain through drugs that cause iatrogenic harm, which it then denies

2. Psychotherapy promises psychological freedom by creating emotional dependence on “therapy”, which it then denies

Report comment

Maybe Aftab should spend a little less time twittering and a little more time listening.

And here’s something that just might expand his awareness a wee bit:

“Psychiatry’s Cycle of Ignorance and Reinvention: An Interview with Owen Whooley”, a conversation with Ayurdhi Dahl, PhD, courtesy MIA

Report comment

And if that’s not too taxing, Aftab might pick up a copy of “A Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Free-Thinking and Radical Enlightenment”, by Bruce Levine, PhD.

Report comment

And for something more visually entertaining, Aftab might watch this: “The Myth of Low-Serotonin & Antidepressants – Dr. David Horowitz”, courtesy After Skool

Report comment

Another look at Aftab’s twitter tells me he’s much too busy promoting himself to spend any time reading anything that doesn’t flatter his already inflated ego. So here’s something short and sweet from Psychology Today:

“Review: The Book of Woe: Why the DSM is doomed to fail”, by Helene Guldberg, PhD

Report comment

And here’s something NO ONE should miss:

“May Cause Side Effects”, by Brooke Siem

Report comment

You gotta hand it to Aftab. After all, it must be tough being an apologist for psychiatry in this day and age.

But as the saying goes, “It’s a dirty job, but somebody’s gotta do it.”

Report comment

Its not just the general public that are duped by the empty hype and lies drug companies, psychiatry and the media constantly produce but the majority of people working in the sector. If you try and raise these issues you are told to ‘stay in your lane’ or are ignored.

There must be something very comforting about believing the lie that you are engaged in services, systems or professions that are progressive and science backed. I think on the Heels of Ignorance by Owen Whooley is one of the best psychiatric histories i’ve read lately. He frames the history of of psychiatry through the lens of ignorance and its a real page turner.

I’ve love to see an interview with William M Epstein or at least a deep dive on his three books relating to psychotherapy and its lies about being evidenced based – The Illusion of Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy as religion and psychotherapy and the social clinic.

I think its all over hyped and overinflated but especially dangerous are the reductionist approaches like CBT because they directly legitimise and support psychiatries nonsense of ‘mental disorders’ – what can it mean for a therapy approach that uses ‘disorder specific models’ to ‘treat’ people if those disorders are voted into existence? Its not uncommon to hear people say but if you use a standardised assessment people can get more agreement on xyz disorder – but if the constructs are as deeply flawed as they obviously are what can it mean to have agreement on them? so more people are in agreement on a completely misleading and wrong construct? its bloody mad.

Report comment

I believe it’s called collective insanity.

Report comment

Or maybe it’s groupthink. Or even gaslighting….

Report comment

Topher,

I just took a look at “The Illusion of Psychotherapy” on Amazon and it sounds well worth reading as Epstein addresses the many social-relational causes of psychic distress.

I look forward to getting a copy once I find one less pricey.

Report comment

Here’s the “science” behind Aftab’s psychiatry: “It IS so because we SAY so!”

Yet for all his disorganized rhetoric, he fails to answer the most basic philosophical question: WHAT THE FUCK IS PSYCHIATRY TRYING TO DO?

Here’s more food for thought: “On the Heels of Ignorance: Psychiatry and the Politics of Not Knowing” by Owen Whooley

Report comment

An even better question: What makes Aftab want to be a publicity hound?

Report comment

Great comment, Birdsong. It reminds me of the UK parliamentary post of ‘Minister of State for Brexit Opportunities.’ If ever there was a poisoned chalice ….

Bob writes: ‘We must be portrayed as “untrustworthy”—it’s the only way that psychiatry can protect the narrative it holds so dear. And that’s what Aftab’s blog, when it is deconstructed, makes clear.’ It always surprises me when defenders of the status quo so quickly drop the superficial aura of evidence-based, scientific objectivity and resort to attacks and personal insults. Some of that flavour can be detected when Aftab interviewed me:

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/moving-beyond-psychiatric-diagnosis-lucy-johnstone-psyd

He played the dirty trick of inviting two very senior psychiatrists – without telling me – to oppose what I had said, on the grounds that I had misrepresented them so badly (in ways he was never able to clarify) that they had to have right of reply. I was the only interviewee accorded this honour.

Recently he has written a curious blog about the Power Threat Meaning Framework, in which he claims that a) no one has ever heard of it b) everyone thinks it is rubbish anyway but c) everyone needs to be warned against it….. and attributes the authors’ motivations to ‘active hostility….against diagnosis.’ Which doesn’t really stand up as an evidence-based refutation.

Report comment

Thank you very much, lcjohnstone. And thank you for the wonderful link.

Aftab’s inviting two senior psychiatrists to oppose you proves you set his pants on fire, but I bet he had the old farts lined up long before the interview, as anyone who dares speak the truth poses a threat their identity and Power. And Aftab’s insistence on proving abstractions proves he’s a fool, a fraud, and a fake.

And thank you for lighting the match.

Report comment

Correction: Aftab’s inviting two psychiatrists to oppose you proves his pants are on fire.

Report comment

Psychiatry’s poisoned chalice is a jug of Kool-Aid. And Aftab’s the perfect Kool-Aid Man.

Report comment

It’s obvious that getting under Aftab’s skin is easy.

He’d be well advised to fix the carefully concealed chip on his shoulder.

Report comment

Ahh I see what happened here. The milieu of performing this study and receiving replies and commentaries has created an environment that has put Aftabs body under vague and non-specific ‘stress.’ This stress has triggered Aftab’s underlying Schizoid disorder, and now his body is generating non specific responses that have no bearing on his particular relationship to MIA, but nevertheless issue in aberrant paranoid ideation. It seems urgent to me that he be drugged liberally and with reckless abandon with these great substances he loves so much.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

But Aftab obviously has Schizoid disorder. Must be from trying to mix psychiatry with philosophy.

Report comment

Lc didn’t mean to reply to you directly. But rereading your comment, you might want to check out the letter written about Johaan Haari in response to his book ‘lost connections’ by a prominent psychiatrist. I read lost connections a million years ago when I was still being actively medicated under a psychiatric paradigm. It covers a lot of the research on psychosocial causes of depression, as well as the false narrative around serotonin and the limited efficacy of ssris. I was really happy to read it because I’d been saying so many of those things for so many years and was always recriminated for it. I didn’t at the time think it even contradicted a paradigm where there were biological things going on, just showed that the biology might reflect psychosocial influences, which always seemed obvious to me. The response letter I read shocked me. The author covered none of the research or reporting that haari did. He went right for Haari’s character, the whole thing was an ad hominem diatribe. It was very deflating for me to read at the time but after hanging around MIA for a minute I was both sad and vindicated to discover that ad hominem is psychiatry’s stock in trade for any challenge to their hegemonic narrative. No matter where the ‘challenger’ falls on the spectrum, if he pokes a hole in ANY aspect of the prevailing paradigm of ONLY broken bodies with NO psychosocial influences and PROVEN effective drugs, he must have his character annihilated and his voice crushed, his credibility ruined and his career tanked. I wish I could remember the psychiatrists name and link you to the letter but I’m

Sure it’s really easy to

Find.

Report comment

Rasx says, “….ad hominem is psychiatry’s stock in trade…”.

You forgot drug pushing.

Report comment

Oh dear, asking those psychiatrists to reply without asking you to respond to them is very bad form. I have had that done to me. It is a way of saying you are rubbish without allowing you to respond. Very bad form from Awais imho.

Those psychiatrists ignored your main points and slurred your character. Normal operating procedure for power under threat. Take it as a compliment.

Report comment

lcjohnstone says:

“Recently, he [Aftab] has written a curious blog about the Power Threat Meaning Framework, in which he claims that a) no one has ever heard of it b) everyone thinks it is rubbish c) everyone needs to be warned against it….. and attributes the authors’ motivations to ‘active hostility….against diagnosis’. Which doesn’t really stand up as an evidence-based refutation.”

He says that stuff because the PTMF rattles his cage. And don’t be surprised if sooner or later he tries to hijack the idea with his own distorted version. But he’d be much better off if he’d a) own his own ‘active hostility’, b) quit his twitter habit, and c) stop dabbling in philosophy that only makes him sound more ridiculous.

And as for him claiming that no one has ever heard of the Power Threat Meaning Framework: it’s my understanding that people at the World Health Organization have heard of it.

I’ve learned one thing dealing with psychiatry: it’s best not to engage with it at all, because it’s full of people like Aftab who will defend their dubious “diagnoses” till their dying day.

Report comment

It is odd that he says no one’s heard of it but they all think it’s garbage! How can “they” think such things if “they” never heard of it?

Sure sign that someone’s afraid to be found out when they start coming up with irrational attacks! Of course, a lot of his friends probably DO think it’s garbage, but I think the same thing about their “model!” Depends who you hang with, I guess!

Report comment

He’s tripping over himself trying to dance the Ad Hominem Shuffle.

Report comment

But maybe he’d be able to catch the beat by cranking up the hurdy gurdy to this snappy tune: “One Thing Leads To Another”, by The Fixx

But I doubt he could handle the lyrics.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

And here’s a song that should be on everyone’s playlist:

“Twisted”, sung by Joni Mitchell

Report comment

Thank you for all you do, Mr. Whitaker. I think assuming and defaming people as “untrustworthy” is what psychiatry and psychology do best. And they make such (often incorrect) assumptions about people within minutes of meeting the person, based upon lies and gossip from others, and sometimes prior to even speaking to the person at all – at least according to my family’s medical records and experience.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Aftab will be paid very well for his work.

And that is all I need to say.

Report comment

He clearly loves being psychiatry’s latest Golden Boy.

Report comment

As always Bob, an excellent essay.

I have always struggled to understand how the bulk of psychiatrists are able to ignore the suffering and abuses. One explanation stuck with me from 25 years ago. New York was holding an educational symposium to educate the judges who adjudicate complaints of inpatients from the 18 state psychiatric hospitals that existed then. I was asked to speak to the group. I agreed to speak but wondered what I could say that would reach these judges. I called my mentor and friend, Rae Unzicker and asked for advice. She told me to tell them that the only people who had an understanding of what really went on in there, were the patients who spent 24 hours of every day confined there. The workers went home each day and saw an extremely abnormal way to live as a NORMAL workplace – how else would they be able to survive and see what took place and not see the suffering. The capacity/ability for the denial of reality(if there is a reality that is more than a convenient agreement of the majority) is not just for those judged psychotic. But for some of us who are better at exercising self interest – it may be the major criterion of diagnosing who is “mentally ill?”

Report comment

Psychiatry is a profession of Power, big egos, and deliberate misperception.

Report comment

Correction: psychiatry is a profession of insults (DSM) practiced by insulting people.

Report comment

Correction: Psychiatry’s a profession of Power, HUGE egos, and deliberate MISREPRESENTATION.

Report comment

When our son was put in antipsychotics I researched the drugs and at that time ten years ago the literature declared they didn’t know how they worked. I thought that illogical. How do you develop a drug if you don’t know clearly the biochemical mechanism by which they are effective? After five years of failure, five hospitals in two countries, the drug clozapine was used and in someway his brain lit up and he could actually half function again. But after realizing the NMDA receptor balancing and killing candida ( so regulating gut microbiome), and a few other goodies this drug offered, and the way the drug modulates the immune system ( calm cytokines down and stabilize mast cells) ; it became apparent that drug resistant schizophrenia was likely Lyme disease and autoimmune encephalitis or autoimmune against the basal ganglia. Which is what my son has. About the only good thing about Pharma in psyche in this age is to walk backward on the mechanism of action of drugs that work, and analyze what was wrong to begin with. It may indeed be the failure of most drugs which teaches us more than their efficacy.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Aftab’s keeping busy, alright. He just posted a response to Mr. Whitaker’s essay, which, unsurprisingly, is quite condescending.

All I can say is Aftab seems like one touchy guy.

Report comment

And VERY thirsty for validation.

Report comment

[Duplicate Comment]

Report comment

Bob, I am a member of the Critical Psychiatry Network (CPN) and am inundated with calls for help from people all over the world desperate to stop taking psychiatric drugs.

We are picking up the pieces of the physical, emotional and psychological harm done by psychiatric drugs. And they have all been prescribed by doctors most of whom have coerced patients into taking the drugs without giving even the basic information about effects, side effects and withdrawal effects, and therefore not having informed consent. Surely, this cannot be called consensual. It is as if patients’ minds and hearts have been abused, some might even say raped, by psychiatrists. But is there an equivalent social movement for these people like #MeToo naming the psychiatrists like Aftab?

As you suggested, if psychiatrists cannot or will not regulate themselves they need to be held to account through the courts.

You have provided the information and you have made it widely available to the public and to psychiatrists and general practitioners and the media and the FDA and the NIMH in the USA and the equivalent organisations around the world, and yet …? Where do we go from here?

Report comment

Well done indeed. I worked at The Retreat in York in 1997, as a consultant psychiatrist, but they’d already lost most of the 1796 spirit, sadly.

We need to keep up the pressure of reality, to make changes. What a travesty that the profession I know and love has become mired in a plethora of lies and subterfuge.

But there is hope, and this excellent essay will assist – I shall quote it at every opportunity – and with luck, more such opportunities will arise.

Here’s hoping – keep up the excellent work, and humanity will prevail – oh yesssssss

Thanx

Bob Johnson. 10 April 2023

Report comment

Well done indeed. I worked at The Retreat in York in 1997, as a consultant psychiatrist, but they’d already lost most of the 1796 spirit, sadly.

We need to keep up the pressure of reality, to make changes. What a travesty that the profession I know and love has become mired in a plethora of lies and subterfuge.

But there is hope, and this excellent essay will assist – I shall quote it at every opportunity – and with luck, more such opportunities will arise.

Here’s hoping – keep up the excellent work, and humanity will prevail – oh yesssssss

Thanx

Bob Johnson.

Report comment

Aftab is the face of something that has morphed into a world-wide, legalized drug ring. And no amount of philosophizing can change that.

Any other “therapies” it lays claim to are already being done by other people or organizations with no connections to the drug world which just happen to be showing “better outcomes”. And what are “better outcomes”? No drug-induced side effects or withdrawal effects.

Report comment

Correction: Any non-drug therapies psychiatry lays claim to are already being done by people and organizations that have no connections to the drug world, legal or illegal. And as a result, people are experiencing better outcomes than psychiatry’s depraved world of “medication” side effects and any ensuing drug withdrawal.

Report comment

Very touchy, and likes to do interviews where he controls the questions and ignores any thing he seems inconvenient in the replies but never enter into an equal conversation with his critics. He will never site studies to support his view for example.

Report comment

Agree 100%. All talk, no substance.

Report comment

Those who control conversations are threatened by different opinions.

Those who neglect to cite studies means one of following:

1. Studies are nonexistent

2. Studies are inconclusive

3. Studies are not in line with their desired expectations

Report comment

Aftab can soft-soap about psychiatry all he wants, but it doesn’t change the fact that psychiatry is a dishonest, exploitative organization whose long history of misinforming the public has allowed it to misuse its power against the most vulnerable people with virtually NO consequences and continues to do so TO THIS DAY.

And this has happened because until now the public has lacked access to information that tells them THE TRUTH behind psychiatry’s many FALSE CLAIMS:

1. That psychiatric diagnoses are physically rooted

2. That psychiatric drugs correct “chemical imbalances” or other physical processes

3. That these drugs pose little risk to people’s physical and/or psychological health

And whether not psychiatry does or has done this deliberately is of NO CONSEQUENCE, because the results are THE SAME: iatrogenic illness, disability or even death.

And no amount of charm or savvy on the part of any slickly packaged internet shill can change this AWFUL TRUTH.

Report comment

Correction: Whether psychiatry does this deliberately or not is of NO CONSEQUENCE, because the results are THE SAME: iatrogenic illness, disability and death, which makes psychiatry’s claims of bearing no responsibility completely invalid.

Report comment

COMPLETELY INVALID!!!

Report comment

And psychiatry DOESN’T GIVE A DAMN about the people it harms; it only sees “patients” as COLLATERAL DAMAGE —

Report comment

Awais us like Allen Frances and Thomas Insel; everything is wrong with psychiatry but nothing substantial must change.

Report comment

I’m dizzy with cognitive dissonance at the insanity of it all…

Report comment

As a humble practitioner of clinical medicine and student of behavioral medicine I apologize to those whose comprehensive knowledge of these areas support their painting of all like myself with the broad brush of ill will and deception..

I’ve met no clinician dedicated to the care of those with neurobehavioral disorders whose repertoire of treatment possibilities didn’t span the entire biopsychosocial spectrum. Medications, psychotherapy, exercise, meditation, and religious counseling have all been utilized by those with whom I’m familiar to treat people presenting with varieties of suffering. What treatments might be reasonable are based upon the collection of a comprehensive clinical history, an appropriate examination, and corroboration by friends and family. Once the best information available is reviewed with the patient, decisions are made collaboratively with patients and families to maximize the relationship factors in the provision of care.

The doubt displayed by many in these areas of study and research is reasonable, but the certainty with which associated epithets are cast into the common experience serves only to distract from the goal of improving the lives of those choosing to seek treatment.

Humility informs committed students of the fragility of definitions, and the absolute infinitude of ignorance. The edges of the next moment are scarcely knowable before the recognition fails to be an informative event.

The engagement of others, patients or peers requires a deep respect for oneself and others. Application of the Golden Rule is a necessary procedure in the successful reduction of our collective ignorance.

Criticism is science’s means of approximating truth and honesty. However, applied to others in arenas of advancing knowledge, it’s a device which falsely creates superiority in the group applying the techniques.

I will continue the humble application of knowledge from the range of treatments about which my mentors taught. I will continue to respect the process of discovery that improves the potential treatments for the people I see as patients, and I will be thankful for the successes experienced as such are the beginnings of patient healing.

None of us adequately understand the range of pathologies, environmental/relational stressors, physiological disorders, or neuroimmunological contributions which provoke patients to seek our counsel.

Certainty applied without recognition of our epistemological limitations serves only to exaggerate the creation of cognitive distortions and delusional equivalents. Its utilization is truly foolish in a world in which only ignorance expands faster than data.

I will attempt to become reasonably able to utilize skills and knowledge across multiple paradigms to meet patients in whatever state they may be, treat them with respect, and then participate in a healing process unique to each.

Binary solutions will likely remain inadequate,and are likely to mislead those without the data necessary to engage this matter comprehensively.

I would hope for fewer epithets and more suggestions and cooperation. We do, after all want the same thing….

Report comment

“I’ve met no clinician dedicated to the care of those with neurobehavioral disorders whose repertoire of treatment possibilities didn’t span the entire biopsychosocial spectrum.”

Well, I have. Plenty of them. Not all of them, but I’d say 50-50 would be optimistic in the psychiatry world.

This sentence also subscribes to a certain viewpoint, calling people “those with neurobehavioral disorders,” and assuming that “treatment possibilities” are the answer. This lens in and of itself can blind you and others who see people this way to the many options available for approaching people who are finding the world difficult to sort out at a particular moment. You are assuming you can identify these “disorders” and can assign them to people, which is in and of itself a dehumanizing process. Additionally, seeing these issues as “neurobehavioral disorders” has been shown to DECREASE empathy and INCREASE bias and “stigma” against them. So it is possible that you and many others who see things this way may fully believe you are being open minded and humble, yet still believe you can “know” what is “wrong” with another person and can “tell them” what “treatment” they need. This disconnect can prevent trust from your clients, and can allow you to unconsciously judge people who don’t meet with your expectations.

This is not casting aspersions – this is a simple truth that has been supported by scientific investigation. NONE of the DSM “disorders” have a consistent and testable biological basis, and so none of them are objectively “diagnosable.” Why not simply talk to each person about what THEY think is needed and what they want to change about their lives, and help them based on their framing of reality rather than forcing a “neurobehavioral” frame on what is often simply normal reactions to difficult circumstances?

I hope that makes some sense to you.

Report comment

Psychiatry doesn’t know the difference between presumption and humility.

Report comment

How do I say this without sounding rude?

People suffer from all manner of problems. This is true. All this “neuro” stuff is practically a bunch of junk. It is irrelevant when what you engage in, in everyday practice, because practically it all boils down to listening and talking, drugs and sometimes institutionalisation. I’m not even saying those things are inherently bad. I’m just trying to cut through the pseudo-intellectual junk philosophising that psychiatrists and psychiatric students often engage in.

Simple questions:

i.) How do you help people? In reality, whenever a person comes in for help, in 15-30 minutes his/her identity is permanently changed to a bipolar, a borderline, a schizophrenic etc. You do not have to live with the social, legal and medical consequences of these terms. That are for other people to face.

ii.) Do you label people with further disorders for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric medication? For example, manic episodes and psychosis caused by stimulants, antidepressants and the like?

iii.) How do you financially help out a person suicidal because of not having money, given that that is a huge problem and a burden for a lot of people causing a great deal of anguish with no way to solve it? Ever given cash to someone in a personal capacity? Having an own home to live in, money enough to take care of basic needs, not rely on the mercy of someone else. Trust me, that would solve a lot of problems compared to institutionalisation and drugging. There is no glory or research paper or MD degree that comes with doing that though.

iv.) People aren’t simply “provoked” into seeking your counsel. They seek your counsel during the worst, most distressing phases of their lives when they don’t know what to do because your places are considered de facto places for help in society and they are forced to return because drugs cannot be purchased without your prescriptions, they have to outstretch their arms to you when psychiatry, it’s labelling and other facets, causes them legal problems, social problems, medical problems etc. and they are beholden to your mercy and charity.

v.) Do we want the same thing? Honest helpers would not psychiatrically categorise people with terms known to bring gaslighting into their lives, label them further for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric medication, medicalise their personalities (the fundamental essence of their being), talk about MRIs and fMRIs which are practically worthless in everyday practice in psychiatry, tell them “there is nothing wrong with psychiatric labelling, it’s just like saying you have diabetes or the flu”. All of these are the practical things your profession and colleagues engage in. They never even admit to their harms and whatever the harmed say goes on deaf ears because there’s always the next patient, the next publication, “more research” and fresh fish to catch.

vi.) Part of the problem is not the doctors. It is the patients. They are the ones who turned psychiatry and its ideology into the monster that it is. Many of them truly do lack insight into what is being done to them in the name of treatment and they often act like kapos for mental health workers.

vii.) All of this data collection, philosophising, going back and forth with data and graphs etc. would not even be necessary if you guys came out admitting simple truths. Sometimes I only see this happen when mental health workers and doctors themselves end up in what has been created for patients. How can you say any of you “respect the process of discovery” when your fellow professionals don’t acknowledge the most basic problems right under your noses?

Sorry, this is not to attack your personally. You may be a nice person. But I’m trying to convey an overall sense of what your profession is doing and how detached they are from the everyday problems of individuals (not the problems that people come to you with, but the problems that people leave with due to the “help” they receive).

Report comment

I think ONE word sums up psychiatry: GASLIGHTING —

Report comment

No one need bother with psychiatry’s constantly changing “diagnostic” Temple of Doom, nor any of its pharmaceutical witches’ brew—when the real answers have been with us all along:

“How to Stop Wasting Your Life – Carl Jung as Therapist”, a video from the Academy of Ideas

Report comment

A word from the wise:

“Never do human beings speculate more, or have more opinions, than about things which they do not understand.” – Carl Jung

Report comment

Psychiatry is medical totalitarianism:

“Menticide is an old crime against the human mind and spirit but systematized anew. It is an organized system of psychological intervention and judicial perversion through which a [ruling class] can imprint [their] own opportunistic thoughts upon their minds of those [they] plan to use and destroy.”- Joost Meerloo, The Rape of the Mind from:

“The Manufacturing of a Mass Psychosis – Can Sanity Return to an Insane World?”, from the Academy of Ideas

Report comment

Definition for Totalitarianism: seeks total control over all aspects of life, including social, economic, and ideological; tends to have a highly developed guiding ideology that claims to have the best interests of the people in mind

Definition for today’s Psychiatry: seeks total control over all aspects of life, including social, economic, and ideological; has a highly developed guiding ideology that claims to have the best interests of the people in mind

FYI: “that claims” is the dead giveaway –

Report comment

Psychiatry doesn’t realize it can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

But here’s something that captures the TRUE essence of philosophy: “Philosophy: The Love of Wisdom | A Guide to Life”, courtesy Eternalised

Report comment

Here’s my take on western philosophy’s motto of “Know Thyself”:

Know yourself as yourself — NOT as psychiatry says you are —

Report comment

Psychiatry is the most dogmatic of all religions.

Report comment

Philosophy is the love of wisdom, and there is no wisdom in psychiatry.

Report comment

Psychiatry is medicalized scapegoating on a massive scale.

Worth a listen: “Face Your Dark Side – Carl Jung and the Shadow”, from the Academy of Ideas

Report comment

And here’s psychiatry’s PERFECT theme song: “BIG TIME”, by Peter Gabriel. The lyrics tell THE WHOLE BIG STORY about “psychiatry”….

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment