There are very few things considered more taboo in the world of mental health than the suggestion that problematic family dynamics can lead to a child developing a psychotic disorder. And yet, when we look honestly at the history and research of psychosis and the broader concept of “mental illness,” it becomes apparent that there are few subjects in the mental health field that are more important. I’d like to invite you, then, to join me on a journey into this taboo territory, dividing our trip into three legs. In the first leg (Part One), we’ll go back in time to explore how such a crucial topic has become so vilified, and then embark upon a flight for an aerial view of some of the most essential findings of the last 60 plus years of research that look at the links between problematic family dynamics and psychosis. In the second leg of the journey (Part Two), we’ll explore a framework that offers us the potential to unify the research on the various problematic family dynamics, trauma, and other factors associated with psychosis, locating the roots of psychosis within two core existential and relational dilemmas that I believe we all struggle with to greater or lesser degrees. Finally, in the third and last leg of our journey (Part Three), we will reap the fruits of our exploration, and consider how what we have learned may guide us as parents, as family members, and as society as a whole in offering genuine support to those who continue to grapple with these extreme states of mind.

A Brief History of a Serious Taboo

Between the late 1940s and the 1980s, we saw a steady flow of exploration and research on the links between certain kinds of parent/child dynamics (and general family systems dynamics) and the subsequent development of psychosis within the child. Among those leading the charge on this research were pioneering psychologists and family systems theorists such as Freida Fromm-Reichmann, Gregory Bateson, R.D. Laing, Murray Bowen and Carl Whitaker. Based upon the fruits of this exploration, there was a period of time in which tremendous hope existed that certain kinds of family therapies and parent education could lead to a significant reduction in the amount of adolescents and young adults who went on to experience psychosis and other distressing states of mind, or that such interventions could at least foster recovery for those who had already gone down this path. One book from that era that I find particularly illuminating and accessible to the layperson, highlighting the hopeful family-oriented movement of this time, is The Family Crucible, which documents a successful family therapy process that leads to the reversal of an adolescent girl going down the path of a schizophrenia diagnosis (Napier & Whitaker, 1978).

Fast forward to today, however, and we find that any quick surf across the internet will pull up a plethora of mainstream mental health organizations that are very quick to denounce the possibility that problematic family dynamics has anything at all to do with a young person developing a psychotic condition. So what happened? It appears that the general assumption within mainstream society today is that somehow the entire 60+ years of research finding links between problematic family dynamics and psychosis must have been thoroughly debunked; and in fact you will find explicit statements to this effect throughout the mainstream mental health field today. And yet, after years of poring over the literature on the etiology and recovery of psychosis, I have yet to find any substantial research that directly contradicts the essential premise that problematic family dynamics can lead to extreme psychological breakdown. So again, what happened?

Let’s rewind to the early 1950s, when the development of the first psychiatric drug, the “antipsychotic” drug Chlorpromazine, led to one of the most powerful industries the world has ever known—that formed by a coalition between the pharmaceutical and the psychiatric industries (which I’ll just refer to as the psychopharm industry for short). This industry was founded on a single ideology—the “mental illness” theory, or “medical model” (which I’ll refer to simply as the medical model)—an ideology that gave this industry tremendous power and influence. The medical model essentially states that distressing states of mind can, for the most part, be categorized into discrete “mental illnesses,” and that although these mental illnesses continue to the present day to be rampant and even growing within our society, we must rest assured that the great medical advances of this industry have already developed powerful drugs that can generally contain them, and that it is just a matter of time before our medical technology will eliminate these illnesses altogether (see my book, Rethinking Madness, or my article here for a more thorough critique on the medical model).

The medical model had already been in existence with varying degrees of power for many decades prior to the development of psychiatric drugs, having been particularly fostered within the field of psychiatry. However, up until this point, the medical model had not been able to fully overcome the popularity of the more psychosocially oriented models and methods when it came to making sense of and dealing with human distress, and this presented a particularly challenging dilemma for the psychopharm industry. How could this industry convince the public that much of human distress could be conceived of as discrete “mental illnesses” arising from diseases of the brain and requiring “medical treatment” with psychiatric drugs at a time when psychosocial interventions were showing so much promise? In the 1970s, the answer to this dilemma came in a somewhat surprising form—the parents of those diagnosed with schizophrenia.

As mentioned earlier, beginning in the late 1940s, we find this very dynamic period of time in the field of psychosis theory and treatment/recovery models in the West, in which a series of studies and projects emerged that offered considerable hope for the prospect that for many young people who were experiencing psychosis, their recovery could be greatly facilitated by addressing the problematic relationships within their life. These included various family and social systems models that supported the entire family or social system, seeing the “identified patient” as essentially a canary in a troubled coal mine; residential facilities such as Soteria, Diabasis and I-Ward, which fostered the development of healthy relationships in away-from-family environments; and transpersonal approaches that viewed such crises from within a spiritual context (i.e., as “spiritual emergencies”), and supported the development of healthy relationship between the “self” and the entire web of interdependence that extends beyond simply one’s immediate social network.

But as this psychosocial movement entered the 1970s, just as it was reaching a point of truly game-changing momentum, a tremendous backlash occurred. Many parents, understandably not feeling comfortable with so many fingers being pointed at them, resisted the idea that they played any role in their children’s development of psychotic conditions, and they began to push back, hard. And it just so happened that the psychopharm industry was more than happy to take full advantage of the situation, providing these parents with the perfect remedy to their dilemma—the medical model. For these parents, this model offered them an alternative narrative that relieved them of any burden of responsibility—their children simply have brain diseases, which is terribly tragic but has nothing to do with family and social dynamics; and for the psychopharm industry, these parents provided the ideal platform with which to spread this model so crucial to increasing their power and their profit margin—what could possibly be a more persuasive “grass roots movement” than an army of concerned parents willing to offer their complete devotion?

The power of this coalition between defensive parents and the psychopharm industry rapidly escalated, leading to a kind of perfect storm that essentially obliterated the movement towards family therapy and general relationship support as a means to addressing psychosis and other extreme states. The flagship organization of this coalition, which still maintains extraordinary power and influence within the mental health field today, is the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI). As an indication of just how successful this coalition has been, in spite of over 60 years of very robust research showing strong correlations between problematic family dynamics and psychosis, and in spite of robust research showing the great benefits of fostering healthy interpersonal relationships as a means to support recovery from psychotic conditions (discussed in more detail below), it has become one of the most serious of taboos within the mental health field to suggest that problematic family dynamics can precipitate psychosis and other extreme states of distress.

In short, then, we find ourselves living in a society in which disability due to psychological breakdown has been continuing to grow at nearly exponential rates in spite of (or perhaps partially because of, as documented so well in Robert Whitaker’s Anatomy of an Epidemic; 2010) a psychopharm industry whose scope and power has likewise grown at a nearly exponential rate. And all the while, we find that the very hopeful and well established premise that so much of this psychological breakdown is rooted in problematic family dynamics has been discarded like so much outdated and worthless trash.

I and others have come to believe, however, that this has been a colossal mistake—that if we take the time to pick up this “trash” and carefully reconsider it, we will find that we have thrown away some truly valuable gems, gems that have the potential to offer real peace of mind to so many troubled individuals and families within our troubled society. So let’s take the time now to look more closely at some of the key findings of the links between family/relational dynamics and psychosis, and explore some of the implications of these with regard to avoiding the onset of psychosis in youth, and in supporting the recovery of those who have already experienced such a breakdown. But before we do, let’s first take a closer look at what we mean by the term “psychosis.”

What Exactly Is Psychosis?

We typically throw the word “psychosis” around freely as if we’re pointing to a condition or illness that is well established, but I’ve come to feel that the term “psychosis” is far overused and abused in our society. Essentially, whenever someone has beliefs, perceptions or behaviors that don’t line up with the generally accepted norms of one’s society (i.e., consensus reality), they’re at risk of being diagnosed with a “psychotic disorder,” typically “schizophrenia,” “schizoaffective disorder” or “bipolar disorder.” However, just because certain beliefs, perceptions or behaviors are considered “abnormal” does not automatically imply that they are “unhealthy,” and vice versa. To the contrary, contemporary society as a whole is extremely violent and destructive—indeed, multiple indicators suggest that we as a species will be quite fortunate if we survive the 21st century; so we need to rein in any tendency we may have to automatically assume that “abnormal” beliefs, perceptions and behaviors are problematic or represent “mental illness,” and that “normal” beliefs, perceptions and behaviors are necessarily “healthy.”

As I’ve discussed extensively elsewhere (and as summarized in my article here), I think it’s helpful to first make the distinction between those anomalous experiences (shorthand for “nonconsensus beliefs, perceptions and behaviors”) that are harmful/distressing and those that are not. If they’re not harming anyone or distressing the individual, then what’s the problem? Why give them any kind of label at all? And in those cases where they are harmful or distressing, this still does not necessarily mean that they are qualitatively any different than other harmful or distressing beliefs and behaviors that are considered more “normal,” such as burning fossil fuels, eating meat, getting drunk or believing in the special entitlement of one’s nation, race or religious group.

There clearly are, however, certain states of mind that are more than simply the existence of certain anomalous beliefs, perceptions and behaviors, or experiencing particularly intense states of emotions. Many people clearly do develop a condition in which these kinds of extreme experiences become significantly unstable and overwhelming, and it is this condition to which I think it can be helpful to refer to as “psychosis.” I have come to see this condition as generally representing an unconscious attempt of a desperate psyche to radically transform one’s deepest experience and understanding of the self and the world—a condition that occurs when one’s current experience and understanding of the self and the world has reached a point where it is simply no longer tolerable, for whatever reason. And considering that our capacity to relate to self and other is so profoundly shaped by our relationships with our parents and other close family members, it stands to reason (and to the research, as discussed below) that these most primary of our relationships can profoundly affect our vulnerability or resilience to such psychological breakdown.

An Overview of the Research on Family Dynamics and Psychosis

Regardless of the particular theoretical model used—whether seeing the etiology of psychosis as being predominantly due to “nature” (i.e., biological/genetic) or “nurture” (i.e., one’s environment), or some combination thereof—what remains undisputed is that the development of psychotic conditions tends to run in families. In spite of the fact that the prevailing mainstream belief is that psychotic disorders are caused by yet to be established genetically inherited brain diseases, the research supporting this is actually very weak (discussed more thoroughly in Rethinking Madness; 2012). On the contrary, when looking at the research linking psychosis to environmental conditions, and especially interpersonal conditions, we find quite a rich and compelling history of research that strongly supports this link. Let’s take a moment now to go over some of the most significant of these:

Between the late 1920s and the late 1950s, psychotherapist Frieda Fromm-Reichman devoted much of her time to trying to understand the nature of psychosis, and to working therapeutically one-on-one with people struggling with such conditions. Building her own theories from a predominantly psychoanalytic relational orientation, she essentially came to the conclusion that psychosis typically occurs when a person becomes overwhelmed by a dilemma in which they both intensely long for and intensely fear the symbiotic merger with another. She believed that such a predicament most commonly emerged as the result of early childhood relational confusion and injury associated with the child’s primary caretaker, which is most often the mother (and hence her coining the controversial term, “schizophrenogenic mother.”) In 1964, Joanne Greenberg, a patient of Fromm-Reichman who experienced full recovery from a debilitating psychotic condition, published the bestselling book, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, which offers a compelling autobiographical account of the potential for full recovery from long-term psychosis when such individuals are supported in repairing early childhood relational injuries.

In the 1950s, Gregory Bateson and his colleagues followed a line of reasoning similar in some ways to that of Fromm-Reichman, and after extensive research, proposed the “double-bind hypothesis” (Bateson et al., 1956). This hypothesis suggests that if the authority figures within a family (typically the parents) place the child in a double-bind by setting up conflicting injunctions so that it is impossible for the child to satisfy one without violating another, then a situation can result in which the child experiences such overwhelming distress that they are forced into a kind of psychotic reaction as a kind of extreme strategy to tolerate this otherwise intolerable situation.

Piggybacking off of the work of Bateson and his team’s double-bind hypothesis, R.D. Laing suggested that these kinds of interpersonal and intrapersonal binds that develop within dysfunctional family systems go on to create an incompatible knot, or untenable dilemma within the child that forces her to essentially “go mad,” which he saw as a profound transformation of the self resulting from a desperate attempt to resolve this otherwise irresolvable dilemma. After closely studying the family and social systems surrounding over 100 cases of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, he concluded that, “without exception the experience and behavior that gets labeled schizophrenic is a special strategy that a person invents in order to live in an unlivable situation [author’s emphases]” (1967, pp. 114-15). So Laing was one of the first in the West to emphasize the deeper wisdom and potential for positive transformation and renewal within the process of psychosis. Laing went on to write extensively on these topics, with The Divided Self (1961), Sanity, Madness and the Family (1964) and The Politics of Experience (1967) being among the most essential of these.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Murray Bowen, a founding pioneer of family systems theory and therapy, came onto the scene as a leader in researching links between certain kinds of family dynamics and the development of “schizophrenia.” Among his most well-known family systems concepts is Differentiation of Self, which essentially refers to the capacity to experience a self as distinct from others, and particularly from one’s primary caretakers. He derived this concept during his years of working with those diagnosed with schizophrenia, when noticing that those so diagnosed typically developed an unusually poor Differentiation of Self.

Bowen also came to notice a significant pattern in which patients diagnosed with schizophrenia often improved when being separated from their families (typically when being placed in the hospital), but then deteriorated upon returning to their families. Subsequently, he became inspired to head an inpatient hospitalization project for the National Institute of Mental Health, in which he compared family members deemed “schizophrenic” with those considered “normal,” and concluded that:

. . . family members were involved in the [psychotic] process with the patient more deeply than had been hypothesized. Fathers were admitted to the family groups, and the hypothesis was extended to think of schizophrenia as a symptom manifestation of an active dynamic process that involved the entire family, and a plan was devised to treat the family as a single unit rather than individuals within a unit. (Bowen et al., 1960)

In this and his other work, then, Bowen contributed significantly to the idea that what is called “schizophrenia” is more appropriately seen as a problem existing broadly within the entire family system rather than simply existing solely within the “identified patient.”

In 1966, George Brown and his colleagues effectively demonstrated that “schizophrenia” patients discharged from the hospital and returned to family environments that have particularly high degrees of criticism, hostility and emotional dependency, are much more likely to return to the hospital. He coined the term “expressed emotion” or “EE” to describe this particular family dynamic, and found that patients from high-EE homes were about 6 times more likely to be rehospitalized than those from low-EE homes (Brown et al., 1966), a finding that has since been replicated numerous times. A later closely related study followed adolescents for 15 years and found that of those whose parents both scored highly on EE measures, 36% of them went on to become diagnosed with schizophrenia, whereas not a single youth became so diagnosed if one or both parents scored low on EE measures (Goldstein, 1987).

In the 70s, stemming directly from this earlier research and Laing’s Kingsley Hall experiment, we witnessed a movement towards the development of residential facilities whose aim was to provide the opportunity for young people grappling with psychosis to extract themselves from problematic family systems and live within social environments designed to maximize healthy relationships with others while offering support in resolving their psychotic crises and moving towards independence. The most well known of these is Loren Mosher’s Soteria home, which was originally established as a National Institute of Mental Health funded research project, comparing the recovery outcomes of such a home with those of mainstream “treatment as usual” (which primarily consisted of hospitalization and psychiatric drugging). This study demonstrated that the Soteria project was equal or superior to the standard treatment on every outcome measure studied, with a significantly higher percentage of Soteria residents going on to live independently with less psychiatric drug use and fewer rehospitalizations (Bola & Mosher, 2003).

Two other similar but lesser known “madness sanctuaries” developed in the 70s were Diabasis, designed and directed by John Weir Perry, and I-Ward, a project initiated by the Contra Costa County Hospital. Though less well researched than Soteria, the evidence suggests that these other homes were able to demonstrate very hopeful outcomes similar to those of Soteria. After reviewing the collective research on the outcomes of such homes, Mosher concluded that “85% to 90% of acute and long-term clients deemed in need of acute hospitalization can be returned to the community without use of conventional hospital treatment” (1999, p. 142).

Unfortunately, in spite of their success, all of these homes were closed due to a lack of funding, which Mosher and others have ascribed to an underhanded political assault by the psychopharm industry, as the existence of such homes clearly represented a potent existential threat to the psychopharm industry. Since that time, several other Soteria and Soteria-based homes have been established within the U.S. and Europe, but these have generally demonstrated less successful outcomes, due most likely to the fact that these more recent homes have been crippled by a mental health system that has become increasingly entrenched within the medical model paradigm. In particular, these more recent homes have generally not been trusted to receive people experiencing first-episode psychosis, they have often been forced to alter their approach in certain ways to conform more with the medical model, and they have often found themselves excessively burdened by being required to support individuals who have already received significant psychosocial injury from years of previous drug treatment and institutionalization (see this article by Dan Mackler for a more thorough analysis of these issues).

Beginning in the late 70s and through the early 90s, several other models that drew from a family systems perspective came onto the scene. In contrast to the Soteria-type homes, these programs consisted of trained facilitators who worked directly with the families (and extended social systems to various degrees) within the family’s natural environment. One such approach is Windhorse Community Services, which draws its guiding principles from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, and attempts to foster the “basic sanity” and wisdom that underlie the chaotic system that has emerged within the mind of the individual and the broader family system. Windhorse continues to provide services in several regions of the United States, though remains generally marginalized by the mainstream system and forced to conform to some extent with the medical model philosophy and treatment approach.

In the late 70s, a team of Italian psychologists developed the Milan family systems approach to working with those diagnosed with schizophrenia, drawing particularly from Bateson’s work on the double bind theory, and developing what they called the “counterparadox” technique, which consisted of various ways to directly counter the entrenched double binds, or “paradoxical communication,” that had formed within such families (Selvini-Palazzoli et al., 1978). Drawing directly off of the work of both Bateson and the Milan team (as well as Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s Dialogism; 1984), a group of mental health professionals in Western Lapland, Finland, developed the Open Dialogue approach, which involves a team of facilitators who work with the family in their own natural environment, and who create a space in which the principles of “tolerance of uncertainty,” “dialogism,” and “polyphony” are emphasized (Seikkula & Olson, 2003). In essence, this approach attempts to create a space in which all voices are heard, and any existing rigid right/wrong or true/false frameworks held within the family system are exchanged for one that is more open to multiple perspectives, with the idea being that such a space provides the fertile ground for genuine resolution and a more sustainable order of harmony to emerge. After documenting the outcomes of this approach for over 25 years, the Open Dialogue approach has demonstrated the best evidence-based recovery outcomes in the entire Western world, with over 80% of individuals experiencing a psychotic breakdown going on to experience full medication-free recovery. The Open Dialogue approach has recently begun to spread to other parts of the world, continuing to offer significant hope for individuals and families so afflicted.

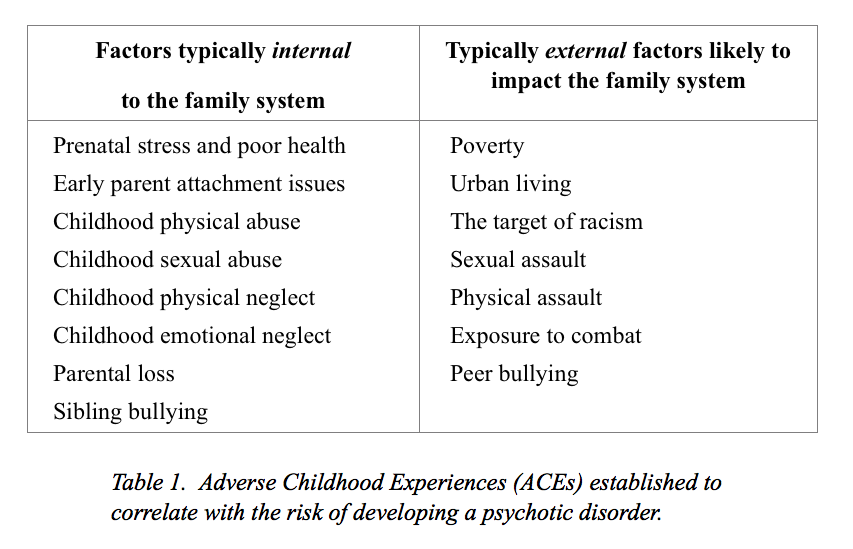

Presumably due to the increasing dominance of the medical model paradigm in the later decades of the 20th century and up to the present day, research into problematic family dynamics and psychosis has become increasingly sparse. However, over the past 20 years or so, a closely related line of research has come into sharper focus—research into correlations between childhood trauma and the subsequent development of psychosis. In particular, a number of adverse childhood experiences have been shown to be highly correlated with the development of a psychotic disorder, particularly those listed in Table 1.

The findings of several such trauma-based studies have been particularly striking, essentially shattering any doubts people may still have about environmental and relational factors playing a major role in precipitating a psychotic condition in a young person. For example, a 2004 Netherlands study followed 4,045 participants who were initially free from psychotic symptoms for 3 years. They found that victims of child abuse were 9 times more likely to go on to develop psychosis, and that the victims of the most severe child abuse were 48 times more likely to develop psychosis (Janssen et al., 2004). And in 2007, a UK study went over the records of 8,580 participants to identify the correlations between a broader array of childhood trauma and psychosis. They found that individuals with 3 types of trauma were 18 times more likely to have subsequently developed a psychotic condition, and that those with 5 or more types of trauma were 198 times(!) more likely to have subsequently developed psychosis (Shevlin et al, 2007). In contrast, research into biological or genetic correlates for psychosis has not been able to establish degrees of correlation anywhere close to these (for a particularly comprehensive review of the literature on childhood trauma and psychosis, see Read et al., 2008).

Note that one factor not listed in Table 1 in spite of significant correlations with the onset of psychosis and other extreme states is the use of psychoactive drugs, including both recreational drugs (such as cannabis and methamphetamines) and most major classes of psychiatric drugs. I didn’t include this factor in the table, however, since drug use doesn’t typically represent an adverse childhood experience in itself, but rather is generally best seen as a common response to the distress caused by such experiences, as psychoactive drugs can often provide temporary relief from such distress. There is a painful irony in using such drugs to ameliorate distress, however—although they may provide significant relief in the short term, they actually increase the likelihood that the person will go on to develop psychosis and other distressing states of mind further down the road (see Whitaker’s Anatomy of an Epidemic or my own Rethinking Madness for more about this).

When looking at the list of childhood traumas in Table 1, it’s easy to see that all of them are either directly related to serious problems within the family system, or at least directly impact upon them. So looking more closely at this list, and at the types of problematic family dynamics that have been implicated within the research mentioned above, a very important question emerges: What do all of these have in common? In other words, is there some common denominator that all of these types of trauma and patterns of problematic family dynamics share, a single underlying factor that makes someone particularly vulnerable to experiencing a psychotic breakdown? Indeed, I believe that there is, which will be the topic of exploration in Part Two.

* * * * *

References:

(for all three parts of the article)

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Problems of Dostojevskij’s poetics. Theory and history of literature: Vol. 8. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Bateson, G., D. Jackson, D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia. Behavioural Science 1, pp. 251-54.

Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Berry, K., Barrowclough, C., & Wearden, A. (2007). A review of the role of attachment style in psychosis: Unexplored issues and questions for further research. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(4):458-475.

Bola, J., & Mosher, L. (2003). Treatment of acute psychosis without neuroleptics: Two-year outcomes from the Soteria project. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(4), 219-229. doi:10.1097/00005053-200304000-00002

Bowen, M. (1960) A family concept of schizophrenia IN D.D. Jackson (Ed.) The Etiology of Schizophenia. New York: Basic Books.

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, 3 vols. London: Hogarth, 75.

Brown, G.W., Bone, M., Palison, B. & Wing, J.K. (1966) Schizophrenia and Social Care. London: OUP.

Fromm-Reichmann, F. (1948) Notes on the development of treatment of schizophrenics by psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Psychiatry, 11, 263-273.

Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2000). Perceived parental behavior, self-esteem, and happiness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(10, 463-470.

Galambos, . L. (1992). Parent-adolescent relations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 146-149.

Goldstein, M. The UCLA High-Risk Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1987; 13(3):505-514.

Greenberg. J. (1964). I never promised you a rose garden. Chicago; Signet.

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2004;109(1):38-45.

Karen, R. K. (1994). Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity to love. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Laing, R.D. (1960) The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Laing, R.D. and Esterson, A. (1964) Sanity, madness and the family. London: Penguin Books.

Laing, R.D. (1967). The politics of experience. New York: Pantheon Books.

Miklowitz, J.P. (1985) Family interactions and illness outcomes in bipolar and schizophrenic patients. Unpublished PhD thesis, UCLA.

Mosher, L. R. (1999). Soteria and other alternatives to acute psychiatric hospitalization: A personal and professional review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 142-149.

Napier, A.Y. & Whitaker, C.A. (1978; 1988). The Family Crucible. New York: Harper & Row.

Neufeld, G., & Mate, G. (2014). Hold on to your kids: Why parents need to matter more than peers. New York: Ballantine Books.

Norton, J. P. (1982) Expressed Emotion, affective style, voice tone and communication deviance as predictors of offspring schizophrenic spectrum disorders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, UCLA.

Read, J. (2004). Poverty, ethnicity and gender. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall, (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia (pp. 161-194). New York: Routledge.

Read, J., Fink, P., Rudegeair, T., Felitti, V., & Whitfield, C. (2008). Child maltreatment and psychosis: a return to a genuinely integrated bio-psycho-social model. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 2(3), 235-254.

Read, J., & Gumley, A. (2008). Can attachment theory help explain the relationship between childhood adversity and psychosis? Attachment—New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 2(1):1-35.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., … & Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Jama, 278(10), 823-832.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K., Keränen, J., & Lehtinen, K. (2006). Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 16(2), 214-228. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268490.

Seikkula, J., & Olson, M. E. (2003). The open dialogue approach to acute psychosis: Its poetics and micropolitics. Family process, 42(3), 403-418.

Selvini-Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., (1978). Paradox and counterparadox. New York: Jason Aronson.

Shelvin M, Houstin J, Dorahy M, Adamson G. Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr Bull 2008;34(1):193-99.

Siegel, D., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D., & Payne, T. (2014). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain way to calm the chaos and nurture your child’s developing mind. London: Scribe.

Whitaker, R. (2010). Anatomy of an epidemic: Magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Williams, P. (2011). A multiple-case study exploring personal paradigm shifts throughout the psychotic process, from onset to full recovery. (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2011). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/54/3454336.html

Williams, P. (2012). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of psychosis. San Francisco: Sky’s Edge Publishing.

Wynne, L.C., Ryckoff, I.M., Day, J. & Hirsch, S.I. (1958) Pseudomutuality in the family relations of schizophrenics. Psychiatry, 21: 205-220.

This is a great article Paris. I always like how courageous you are in bluntly and directly addressing these controversial issues.

As I’ve noted in other comments, it is pretty obvious from the type of studies you referenced, and from common sense, that poor parenting of all forms can and does contribute to increased risk for “schizophrenia”, i.e. psychotic breakdown. Abuse and neglect cause psychological stress, psychological stress increases the risk of someone being overwhelmed emotionally, and in extreme cases this can lead to psychotic symptoms. It’s pretty logical and the data from John Read, ACE study, etc back it up. I remember in John Read’s interview at UCLA recently he was saying that over 50 separate studies are now showing strong links between trauma, abuse, and development of psychosis.

As Donald Winnicott noted, schizophrenia or psychosis can be viewed as the negative, or mirror image, of the healthy process of increasing security and trust which develops between skilled parents and well-supported children.

It is sad to see NAMI parents saying that poor parenting can’t possibly cause schizophrenia… when sometimes, these are ironically some of the very parents whose neglect, poor parenting skills, and abuse, will have partially contributed to their children’s having a breakdown and getting diagnosed with schizophrenia. One can understand how it’s more comfortable for such parents to delude themselves into believing that they are good parents, and their children’s whole problem is one of faulty brain chemistry and genes (which isn’t very flattering to parents, either).

But the notion that parents should be blamed if they contribute to their children’s psychosis is simplistic and wrong; of course they shouldn’t be blamed. Trauma can be passed down through generations and there is no one person to blame, only problems to be understood. Understanding and acknowledging how parents contribute to psychosis risk can actually be a positive thing because it can allow for change, prevention, and repairing relationships. Deluding oneself that schizophrenia is a brain disease, on the other hand, usually dooms the young person to a life of being drugged and viewed as a chronic invalid. That is unfortunately what happens today to most young people unfortunate enough to be caught in this very unfair situation involving multiple lies about what is known about so-called schizophrenia, told by psychiatrists and our System.

Report comment

Paris, I want to note that your writing appears to me (I have read all of Rethinking Madness) to be mostly missing one major area of hopeful research… Fairbairnian and Kleinian psychoanalytic approaches to psychosis (what a mouthful!).

You mentioned a couple of these in your book (referencing Silvano Arieti) and in this piece, referencing Freida Fromm-Reichmann.

If you haven’t read them in depth, I recommend to you the writers Harold Searles and Vamik Volkan. Their insights into psychosis are truly profound, and their case studies fascinating.

Searles has the four phases of schizophrenia recovery: Out of Contact, Ambivalent Symbiosis, Therapeutic Symbiosis, and Individuation. For him these phases he encountered in working with schizophrenic patients reversed, or cured, the pathological regression or negative sequence of emotional development that occurred between the psychotic-child-to-be and its early world/parent figures. I recommend his chapters such as “The Mother Transference” (about how conflictual feeling surrounding the psychotic client’s parents get transferred to the therapist) and “Intensive Psychotherapy of Chronic Schizophrenia, A Case Report” which give a great insight into how parental and family relationships contributed to the development of the psychosis and how replaying and modifying these interactions can lead to healing. These essays are in his collections, Collected Papers on Schizophrenia and Related Subjects, and Collected Papers on Counterference and Related Subjects, available on Amazon.

Volkan is technical and hard to read but, in my opinion, is the best and most insightful writer on how to work intensively with severely psychotic people. He writes about how abuse, trauma, and neglect can lead to organismic terror and horror, and the need to defend against these extreme emotions lead to the creation of a subself (a container of developmentally early representations of oneself and others) that he calls the “infantile psychotic self”.

This infantile self arrests the personality in a kind of twilight zone in which the psychotic part in its terror produces delusions, hallucinations, and bizarre thoughts. Meanwhile, the “uninvaded self” – the fragmentary but slightly more mature self-and-other images surrounding the infantile psychotic self structure – attempt to maintain a modicum of a relationship to the external world, but are unable to cope with the primitive overwhelming affects of terror, rage, and despair during difficult periods. The archaic (developmentally early) self-and-other images in the infantile psychotic self have to be painstakingly matured and modified in relation to the therapist or another person or entity, in order to help the person become non-psychotic.

Volkan’s cases of Attis, the delusional “Would-Be-Wife Killer” who later came to be a beloved community priest when he was no longer psychotic, and Jane, the psychotic girl who reminded Volkan of Tarzan’s bride and later became a renowned painter, are truly incredible reading; they are in the book The Infantile Psychotic Self and Its Fates.

The last therapist I want to recommend to you is the Italian Gaetano Benedeti, and his writing in such books as Psychotherapy as Schizophrenia. His long-term study of 50 schizophrenic clients given psychotherapy an average of 3x/week for 5 years, that he did with Pier-Maria Furlan, is particularly interesting and hopeful.

Another writer at these one’s level, if you need more reading, would be Bryce Boyer, e.g. The Regressed Patient. There are many others found in the references of these books.

Also, I have never seen you cite the document I link below, but I think it’s among the most important I’ve read about psychotherapy and psychotic conditions – William Gottdiener’s metaanalysis of 37 studies containing 2,642 people labeled schizophrenic who were in psychotherapy an average of 20 months, 1.5 times a week. A big mix of studies, but most of them were long-term psychotherapy, and the effect size was quite large and robust, favoring psychotherapy as helping people with psychosis be much better off (in other words, obviating the need for the recent RAISE study). The main finding is that 20 months of psychotherapy made psychotic people almost twice as likely to recover as those who didn’t receive therapy. Gottdiener explains the statistical measures better than I can.

Here’s a paragraph you might find of interest: “When antipsychotic medication was used with individual psychotherapy the mean effect size was r = .31 (95% CI + .19 to .42). When antipsychotic medications were not administered with individual psychotherapy the mean effect size was also r = .31 (95% CI + .12 to .48). The corrected effect size and BESD results for psychotherapy with medication and without medication was the same…..

It is surprising that the proportion of patients that were likely to improve without conjoint medication, is similar to the proportion of patients that were likely to improve with a combination of individual psychotherapy and antipsychotic medication. This finding is contrary to most therapists’ clinical expectations. The finding that individual psychotherapy can be effective without medication is not new (see Karon & VandenBos, 1981). However, it is important because it suggests that individual psychotherapy alone might be a viable treatment option for some patients who do not improve from treatment with antipsychotic medications, for some patients who refuse to take medications, or for patients who are treated by therapists that choose to use little or no adjunctive medication. ”

I was not at all surprised by this, but I’m sure most psychiatrists would be.

http://psychrights.org/Research/Digest/Effective/BGSchizophreniaMeta-Analysis.htm

Report comment

Hi bpdtransformation,

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed the article. I’m impressed by your breadth of knowledge(!) Thanks for your suggestions of readings–I’m familiar with some but certainly not all of them, and look forwad to following some of these leads.

You commented:

“But the notion that parents should be blamed if they contribute to their children’s psychosis is simplistic and wrong; of course they shouldn’t be blamed. Trauma can be passed down through generations and there is no one person to blame, only problems to be understood. Understanding and acknowledging how parents contribute to psychosis risk can actually be a positive thing because it can allow for change, prevention, and repairing relationships.”

I just want to say that I couldn’t agree with you more about this, and I hope I didn’t come across in this part suggesting that we take a stance of “blame and shame” towards the parents. I actually will be discussing this very issue in more detail in the next two parts (especially Part Three) of this article. In particular, as you say, all of us (parents included, of course) are embedded within social systems that are very wide (extending out to our extended family, community, nation, and all of the human society) and very deep (extending back through many generations). So as we raise our children, we bring all of this with us–the beliefs and pressures of “wider” and the “deeper” social systems–but we are often oblivious that we are doing so. So when we find that our family system is struggling (and they virtually all struggle at times), as you suggest, the first and most critical step to is become curious about what kind of beliefs and behaviours are present here, where do they come from, and how can we shift towards something more harmonious and wholesome..? So shifting from an attitude of “blame” to “openness, curiousity, humility and shared responsibility.”

Thanks for your comments,

Paris

Report comment

Paris, thank you and no I did not ever think you intended a blame or shame approach. My comment regarding the simplistic nature of blaming parents was covertly directed toward those groups who fraudulently hold that identifying parents as contributors to a child’s receiving a schizophrenia diagnosis constitutes blaming: some NAMI members, the APA, most American psychiatrists, and the disease model in general.

Report comment

Thanks for the clarification, BPDTransformation. Good point about the way people (like myself, you and others) who encourage parents and society to consider the harm that problemtic family dynamics may cause are then vilified themselves–a common derogatory term I have found used to try to shut people like us up is referring to us as “mother blamers.” A frustrating and very “head in the sand” response, to say the least (!) I’ll say a lot more about this issue in Part Three.

Paris

Report comment

Thank you for stating your definition of “psychosis” but for me there was nothing existential about my emotional distress; my experience were a living nightmare and caused unbelievably painful emotional distress.

I think that distressful experiences cause “psychosis” and that parents are a primary cause of distressful experiences but they are not the only source of distress. Good parents are getting involved in harmful support groups with good intentions defend themselves from blame along with bad parents who are there doing the same.

Best wishes, Steve

Report comment

Thanks for sharing a bit about your own experiences, Steve.

To clarify, I certainly have no intention to “romanticize” psychosis (if that’s what you have taken away from my words). To the contrary, having dipped into these waters myself, I agree that it is very difficult to convey to others who haven’t experienced this kind of thing the intensity of pain, terror, confusion, etc., that can go along with such experiences. I simply have a lot of faith in “organismic wisdom,” that as long as we are alive, some part of us will continuously strive for health and wholeness, although whether this is actually attained is a different matter. Also, by “existential,” I’m simply referring to the basic core dilemmas inherent in our existence–difficulties and challenges that we all face, so long as we are alive, and of course learning how to work with the inevitable pain and confusion of life is part of this (I’ll be saying much more about this in Part Two of this article).

Best regards,

Paris

Report comment

Thank you, Steve

Report comment

I think when a child’s natural behavior indicates that they are challenging the norms of the family, how parents react and respond to this makes all the difference. If they shame, punish, or guilt the kid for going against the grain in a way that does no one any harm–and in fact, which gives opportunity for growth in the family– but it’s simply different than what the family dogma would dictate, then there will be rebellion and power struggles, perhaps leading to depression and anxiety, at the very least, due to feelings of being emotionally coerced into compliance. Families can be like a cult, if the dynamics exist to appease abuse and dysfunction. We need permission to be ourselves, for health and well-being to occur.

However, if parents can welcome the challenge because they expect to be challenged by their children, and they know how to set healthy boundaries while giving permission for the kid to explore their nature, even if it goes against their grain, then I feel there will be a better outcome in the clarity and confidence of the child. The child may fall and have to get up again, but that’s part of growth and learning self-resourcefulness and self-care.

I’m not saying it’s not a challenge for parents, who are also human and who come with their own baggage. But I think there is a clear line between a child who is allowed to explore their nature and one who is shamed, demeaned, and ostracized for being themselves, or even for having a need, when these should be totally expected. Parents may have issues, but they are the adults and influence kids in every way, first and foremost. How they set the example for how to deal with their personal issues and the shit in the world is what the kid will most likely internalize and repeat, when they experience life’s challenges.

It’s a delicate balance, but I think raised awareness around the issues of parenting and control are always helpful to all concerned. After all, what we learn in our families is what we bring to our communities, these are direct reflections of each other. Social healing is the order of the day, imo.

Report comment

Actually, regarding the personal issues of the parents, when a kid challenges them and they feel angry and blaming about that, that is a PERFCT opportunity to work on their issues. Blame the child for challenging them? I don’t think the child is at all at fault, no way they can be. It’s their job to challenge parents.

Great growth and healing opportunities for all concerned, if we stay out of (or work through or ascends, however one wants to put it) judgment, blame, and guilt. Everyone makes mistakes, we needn’t punish ourselves for them, nor punish others for making them. Better to simply correct them and move on in a new way. That’s how we evolve forward.

Report comment

I think these are all really good points, Alex. They speak directly to what I’ll be discussing in Part Three of this article–towards effective parenting and communication. I’ll look forward to any feedback you may have on that section, if you’re so inclined.

Best wishes,

Paris

Report comment

Thanks, Paris. I definitely look forward to the next parts.

Family healing was core to my own healing and personal transformation. I was the ‘truth-speaker’ (and forgiver) who challenged the family system in every way, and for a while, it was hell to pay, and, indeed, it was literally crazy-making.

But I worked with these issues for years to find a delicate balance, where I honored from where I came without giving myself over to values which were not meaningful to me–and which in fact, were stigmatizing and wounding to me, as a child–and I was finally able to unearth and dismantle what I had internalized from the family dogma, so that I could achieve the emotional freedom to walk my soul path of truth, which has proven to be extremely beneficial healing in every way imaginable.

Family healing is a remarkable and enlightening journey of personal discovery and integration. I’m so happy you are writing about this, specifically, I feel it is extremely valuable and supportive to changing the world. It is the core of our society.

Report comment

Hi, Alex,

There are all kinds of children, and I feel I need to point out that it is not just the “challenging” children who may end up with a diagnosis of ‘schizophrenia.’ In fact, IMO, they may be in the minority, but they are the vocal Majority of people who blame their condition on childhood trauma. Consider, the quiet, obedient child who challenges nobody. The guy or girl who passes under the radar. There’s a lot of stereotyping at MIA that it’s the rebels who become schizophrenic because they’ve been at the receiving end of their parents anger. Not necessarily the case. Perhaps these quiet ones “wake up” around their late teens and decide that being a passive observer of life is now their biggest challenge to overcome.

Just my thoughts, based on my experience.

…Rossa

Report comment

Excellent point; thank you for giving voice to quiet sufferers.

Best wishes, Steve

Report comment

Point taken, Rossa.

I guess I was talking about kids that do challenge their parents–not just with aggressive behavior and the like, but simply by choosing a different path than what parents intended and expected. That was my situation, and I speak from that experience. I also know a lot of people–both in person and also a lot of people that I’ve read about, famous people–who tell about going against the grain of their parents’ wishes for them, and the problems that it caused in the family.

Am I saying this causes something which could be DSM diagnosed? Not necessarily, but often it is, and at the very least it causes distress that can manifest and play out in a variety of ways.

I hear this is not your experience, that you are coming from a different dynamic. I appreciate your experience.

I don’t feel I’m blaming anything on anyone, simply providing a perspective from my own experience and from what I know about others, my work with clients, my friends, etc. Sorry if it comes across as blaming. I do feel parents play a role in how their kids embrace adulthood, but that is a long and complex discussion of generational patterns and contracts, cause-and-effect, and how we influence each other energetically.

Thanks for your feedback, I’ll keep in mind how I express myself.

Report comment

And not just a different path, come to think of it, but who develop different values, etc. Really, going against the grain of the family value system and choosing one’s own way of doing life, is really what I’m talking about–being made to feel guilty or selfish for being independent from the family. That’s a very common double bind which, indeed, causes internal emotional conflict, and potential suffering for the adult child, until they claim their freedom by simply not caring about the naysayers.

Report comment

Hi, Alex,

I don’t feel you were parent blaming in what you wrote. I just felt I had to point out that it’s often the quiet ones, the ones who never rocked the boat, who end up the dreadful “S” label. So, no need to write with everyone in mind. You’re experience is what counts for you.

Best,

Rossa

Report comment

Ah, ok, thanks Rossa, I did misinterpret, thanks for clarifying and of course I totally agree with you, that there is a wide spectrum here. Indeed, all voices need to be heard, from these different perspectives and experiences.

I’m kind of chuckling to myself, here, because I can have trouble discerning here online whether I’m being accused of being or saying something, or if something is being added to the conversation in a neutral way. I’m just so accustomed on here of being called out for something. Especially this topic, regarding families and parenting. I totally understand the challenge of that.

I guess some people know I made a film about stigma and discrimination. My assertion is that, for a lot of people, (not all, but still common, I think), this begins in the family. So for the film, I asked everyone about their family relationships (given that my family dynamic was totally instrumental in my falling into the psychiatric pit), and I got some very interesting answers.

These are 6 diverse voices–different walks of life, different personalities, different experiences, different perspectives– and in fact, one of the women in the film was what you are calling ‘the quiet one,’ and she talks about what happened to her when she was hospitalized in a very articulate and moving way, I think.

Our experiences of childhood turned out to have some overlap and also a lot of differences, we were on a continuum.

Check it out if you wish, this is all about family influence on our mental health, and then what happens when we give it over to the system. And yes, some people have trouble sitting through this, specifically because the family issues make them uncomfortable. Still, it is without a doubt vital to explore this, so I broached it without apology, as directly and sensitively as I knew how–

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AtDGxJWmj5w

Report comment

My thoughts too, based on my experience, and Laing too seemed to think that the good obedient child was more likely to have problems along the road. I understood from his writings (Divided Self) that although the teenage years make evident the problem, the problem started way back in the formative years i.e. conception to age two or three. If the self isn’t formed properly then (yes, because of faulty parenting) then there is no strength for rebellion later. Open rebellion is so much healthier than rebellion turned in, attacking the fragile self – not just psychosis but also anorexia and probably other examples too.

It’s particularly tragic because these are the children who so longed for acceptance throughout, tried their best to be good, and then in the end, still can never measure up and on top of everything, when they finally fall apart under the strain, are blamed for bringing disgrace, expense, worry etc. to the family and told that they’re crazy.

Jewish tradition teaches that parents are supposed to look at the things in their children that bother them the most, and see them as reflections of their own imperfections – i.e. the parents are the ones who are supposed to change as a result. This is also true between spouses.

So, i am not so quick to exonerate parents and say, “Poor things, they did the best they could.” Maybe they did, but when the tragic results become evident and they still don’t examine themselves to wonder how such a thing happened, then they deserve, to my mind, a measure of condemnation.

Report comment

Great piece! Thank you to the author and all those that took the time to make useful comments. Very useful.

Report comment

Dear Paris, I really love the depth, research and innovative thought that you have put into your work. Since you are being so thorough, I can’t help but wonder if you are skipping too quickly over particularly extreme context of today’s society for young people.

The use of psychoactive drugs, both recreational AND psychiatric/prescribed is not just a common response to distress used to provide temporary relief but it’s increasingly part of young people’s culture of experimenting, gaining street cred and even “independent” economic support through “disability” for those who feel little hope for finding meaningful work with fair wages. Are you aware of the way the Hunger Games books and movies speak to younger people. These are extreme times in their reality and imaginations.

Report comment

Hi Diana,

I’m glad to hear you’re enjoying the article, and thanks for your insightful comments.

As I mentioned above, it’s a bit tricky breaking the article up into 3 parts like this, as much of the comments are pointing to issues I discuss in the later parts, such as yours here. If I’m understanding you correctly, you’re wanting to make sure we acknowledge the importance of the broader social networks and how they impact families and the development of youth. I couldn’t agree with this more. Although I’m primarily discussing the nuclear family in this article, families are embedded deeply within the broader social networks–so just as a child is embedded in a family, the family is embedded with the community, the community within the nation and broader human societies. In order to support the individual who is really struggling, we have to recognize that this individual is really just a canary in a coal mine, pointing not only to the problems within the family, but also to those within the broader society (and they are many!). I discuss this further in my article here, which you may enjoy:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/06/can-madness-save-the-world/

Best wishes,

Paris

Report comment

Your theory that psychosis is caused by distress alone does not explain why many people experiencing extreme distress do not become psychotic. If psychosis was caused by distress alone, one would expect high levels of psychosis in war fields and refugee camps but this has never been the case. Distress is known to be a factor in many illnesses including heart disease and cancer. It appears to be a factor in mental illness but is certainly not the only cause, maybe not even a primary cause in many cases.

In my many years of meeting with people who suffer from mental illnesses and their families I have met some who were traumatized but also many others who had very normal, mundane lives. Some became psychotic after suffering from viral illnesses or using certain drugs such as SSRIs. Others became psychotic after going without sleep or going on extreme diets. Some have family members who have mental illnesses, others do not. There appear to be many causes of mental illness and endless debates about causes seem to be doing little to alleviate suffering.

I would love to see more research on what works to give sufferers relief rather than more debate on the causes of the suffering.

Report comment

“I would love to see more research on what works to give sufferers relief rather than more debate on the causes of the suffering.”

You might check out the link I gave in my comment above, to Gottdiener’s metaanalysis of psychotherapy for psychosis. Also, check out the books Treating the Untreatable (Steinman), The Infantile Psychotic Self (Volkan), Recovery Sanity (Podvoll), and Weathering the Storms (Jackson) for some fabulous case studies of chronically schizophrenic individuals who were healed. You can get them used on Amazon.

Regarding your comment, I think Paris’ studies linked above are quite convincing in making the case that trauma, abuse, neglect, and poor parenting in general are one of the main, if not the main, factor contributing to psychosis / getting a schizophrenia diagnosis. John Read has many more of these studies if you look up his work.

I would say the idea that “psychosis may be caused by distress alone” may be misleading or out of context. I believe that distress alone is not enough; there also needs to be preexisting vulnerability – this can be the case for a developing child or young person simply by virtue of the emotional stage they are at. Or there also needs to be distress/trauma that is long and severe enough to wear down a strong personality to the point where it is vulnerable. If you read the developmental theorists like Searles or Volkan, I think it helps to understand these processes of personality development or regression better.

In a war zone or refugee camp, many of the people will have had relatively stable families growing up, and although they are suddenly thrust into an overwhelming situation, their previously non-psychotic personality organization is usually strong enough to weather the extreme stress, as long as it doesn’t go on too long. On the other hand I think that many, many of our veterans do get given serious diagnoses of whatever “mental illness”, misnomer as that is, when the return from the war zones.

By contrast, perhaps you are aware of the studies that show that almost anyone, if kept in solitary confinement / supermax prison conditions long enough without any access to their fellow human beings, will begin to show signs of schizophrenia after several months of complete isolation. This shows that even the strongest personality can break down into psychosis given long and severe enough neglect and isolation.

Also, we should be clear that psychosis is not an illness, but a complicated syndrome or related constellation of psychic experiences. As far as we know currently, there are no illnesses that are mental. Real brain diseases on the other hand are things like Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Report comment

Very well stated, BPD

Report comment

I think I see where you are going. While it’s true that many, many people who experience psychosis have suffered trauma, to assume that ALL have would not explain the phenomenon in its entirely. (I have not, personally experienced anything I would consider traumatic but I have certainly departed from consensus reality. I didn’t consider these to be learning experiences, though I understand they can be.) If I had to shoehorn myself into the model in the article, I suppose putting “trauma” on a spectrum, maybe my threshold for being traumatized was extremely low given my basic personality and temperament, and my rather average childhood (which produced siblings that are well adjusted) was somehow devastating to me subconsciously? Then again, trying to fit the details of my life into models that don’t apply is how I got stuck in psychiatry in the first place.

Report comment

I totally agreed with you until I experienced an extended period of extremely distressful experiences; thereafter, I realized that we have little understanding of the experiences of others. Prior to trauma, I believe that my experiences were “average” and that my successes in life were substantially attributable to a better “inherited” mind/brain. I considered distressful “events” as small hurdles to overcome in an exciting journey through life. After trauma, my experiences took a different path and became predominately distressful. Distressful “events” became part of a pattern of painfully distressful experiences that exemplified my painful plight with an increase in emotional pain. People perceive of distressful “events” differently because of personal histories of experiences that are impossible to qualify or quantify for research.

Understanding that distressful experiences cause of mental distress (emotional distress) is the key to improving “mental health” care. Believing that emotional distress is a “mental illness” is the reason that mental health “care” is so harmful.

Best wishes, Steve

Report comment

Good points, madincanada and BPDTransformation,

A particular framework that I think really speaks to this is that of an holistic organismic one. In other words, I think that we (the collective we, as a society) make a mistake by trying to compartmentalize various kinds of experieces (mind vs. body, environmental vs. biological, physical toxins vs. relational toxins, etc.). If we consider the organism as a whole, then we recognize that any state of distress (whether it be “biological” illness or “psychological distress”) represents that this organism is struggling to meet certain basic organismic needs, and is simply responding in the best way that it can to try to meet these, to survive and hopefully thrive. So whether someone is experiencing cancer or a flu, or so called “psychosis,” “depression,” “autism,” etc., we can say that what we are basically seeing is a desperate organismic response to some barrier(s) that are interfering with it meeting its basic needs; and the challenge as supporters is to support the person in idenetifying where these barriers are coming from (often from more than one domain) and in working with (rather than against) this basic organismic wisdom of the being to facilitate recovery. What makes what I’m calling psychosis a bit different than the other kinds of organismic responses is that I believe psychosis represents the organism’s attempt to radically transform its basic cognitive constructs (its lens through which it perceives and interprets self and the world) in order to surive what is experienced as an overwhelming threat to the self at a very core existential level–yes, certainly a very risky and haphazard strategy, but one that I believe does have potential to lead to very powerful healing and transformation if successful, and not only for the individual, but also possibly for the larger social networks (indigenous cultures generally understand this, and therefore value individuals who go through such paradigm transforming experiences).

For more of my exploration on the “holistic organismic paradigm,” see:

http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/06/rethinking-mental-health-part-1-from-positivism-to-a-holisticorganismic-paradigm/

…and

http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/07/rethinking-mental-health-part-2-towards-a-needs-based-system-of-diagnosis-and-support/

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris,

This is a interesting set of ideas about organismic reactions… it is basically the same theory, in slightly different language, to what is in with Vamik Volkan’s book The Infantile Psychotic Self. Volkan called the response to existential terror “organismic panic” and the attempt to reach a better equilibrium “psychobiological push”, if I remember it correctly.

His book has great analyses of the relational and psychological-defensive factors that prevent the self structure, in “schizophrenia”, from reaching a healthier non-psychotic equilibrium. Unless the psychotic fears are exposed and worked through, they tend to reoccur in a circular manner and to keep killing off the possibility for having better relationships by maintaining a close psychic system of distorted self-other perceptions… in psychoanalytic language, the self and object relations of a psychotic person do not evolve/mature but instead remain stuck in a cycle of fusing with and separating from other distorted all-bad self/other images.

In a successful therapy an initially psychotic person can reach a symbiotic (borderline) level of relationships and then later a neurotic/healthy level of object relationships. At a certain point in the process they are able to face the original terror and conceptualize it in a healthier, less infantile way; this brave step dissolves the infantile psychotic self and allows for progress to the “crucial juncture”, the psychological place at which all-bad and all-good perceptions can become more integrated.

In Searles’ language, they can progress through the early developmental phases, from out of contact to ambivalent symbiosis to therapeutic symbiosis to individuation, in this way retracing and reversing the pathological regression that occurred after the trauma, when the person who wanted their needs met was instead traumatized and retreated in terror into ambivalent symbiosis and/or out-of-contact phase (also called “autism”, meaning something different from the DSM label).

I encourage you to check out the books by Volkan, Searles, and their colleague Bryce Boyer, it can add another dimension of understanding to your writing and your practice.

Report comment

Paris,

Thank you for this history and analysis of the family’s role in extreme experiences. One of my sons went through a 2 week extreme experience 18 months ago using an Open Dialogue approach. He has not returned to this difficult state which seemed to have been related to extreme worry and stress, a history of bullying, parental divorce, difficulties related to some developmental challenges and severe existential concerns. You helped me with some suggestions at the time and I will be forever grateful for your support.

I agree with you that family experiences and dynamics are a big factor in the development of psychosis and that they need to be included in our understanding and response to these experiences. Furthermore, trauma is pervasive and come in many forms, often beyond the nuclear family. I am convinced that trauma in all it’s forms must also be considered as a cause. Beyond these, development, growing up and life itself are difficult. Psychosis may be an attempt to cope with and make sense of something beyond comprehension.

Your work is so important. Thank you

Report comment

Thanks for your comments, “Truth in Psychiatry,”

I am really glad to hear about your son’s successful working through of his crisis. Thanks for sharing this.

I also appreciate your wanting to make sure we acknowledge the broader context and social systems, and as I just mentioned in my comments to others above, I couldn’t be in more agreement with this(!) as I’ve discussed elsewhere, such as in the following two articles:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2013/05/the-mental-illness-paradigm-itself-an-illness-that-is-out-of-control/

https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/06/can-madness-save-the-world/

I am focusing primarily on the nuclear family in this particular article, but we absolutely need to acknowledge the severe limitations and stress placed upon such families trying to survive in a broader society that is so profoundly troubled (I’ll discuss this a bit further in Part Three).

Best wishes,

paris

Report comment

Truth in Psychiatry,

I agree with what you say.

Your son was out of the extreme experience in 2 weeks – if he had gone through psychiatry he might have been collared as a “schizophrenic” for the rest of his life (depending on the treatment and how he reacted to the ‘medications’).

I think there are probably lots of people that suffer terribly but don’t externalise, theres enough in normal life anyway to drive a person to crisis.

I think “schizophrenia” as a ‘diagnosis’ should be withdrawn because it’s use is very dangerous and open to manipulation (anyone could be diagnosed as a “schizophrenic”, if they were to confide their private thinking, from time to time).

Good luck in the future!

Report comment

Hooray! More of psychiatry’s and NAMI-families’ greatest nemesis: the TRUTH! Thank goodness for the Internet and social media. This may be Mad in America’s first article to go viral. Way to go, Mr. Williams!

Report comment

“Hooray! More of psychiatry’s and NAMI-families’ greatest nemesis: the TRUTH! Thank goodness for the Internet and social media. This may be Mad in America’s first article to go viral. Way to go, Mr. Williams!”

The TRUTH means or should mean “the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” Notably missing from the article is any mention of epigenetics.

Report comment

Hi GetItRight,

Thanks for bringing in the idea of epigenetics. While of course a complex and still far-to-be fully understood field, my understanding of what it essentially has been successful in doing is further reduce the viability of bio-reductionism (the idea that we are born with a rigidly constructed genetic “blueprint” and are fated to developing certain characteristics and/or “illnesses” according to this). And it further reinforces the viability of the role that trauma and core beliefs (often closely related to each other) play in determining the particular qualities we develop and the likelihood of cultivating wellbeing in our lives (or lack thereof). What I find is particularly fascinating with regard to the discoveries of epigenetics is that it reveals that Lamarck was probably a bit more right on than Darwin in recognizing that certain environmental experiences of an organism (i.e., trauma and other powerful experiences) can modify the organism at the cellular level (i.e., epigenetically) in a way that allows it to pass on certain learned responses/”core beliefs” to its offspring purely via genetic/epigenetic transmission. In other words, this field is reinforcing the long held common sense wisdom of intergenerational trauma—that it is passed down not only environmentally but also probably genetically. So rather than undermining our understanding of the importance of family (and broader systems) dynamics, I see the field of epigenetics actually soundly reinforcing it. Whatever trauma, neglect, discrimination, extreme distress we experience within our own lives, if not adequately dealt with and resolved, are likely to change us at a very core level (including cellular level) and then be passed down to our offspring (if not by the actual transmission of certain behaviour patterns and “core beliefs” about self and the world directly, than probably epigenetically to some extent). Btw, I think that quite a good book on these ideas written for the layperson is Bruce Lipton’s, “The Biology of Belief.”

Paris Williams

Report comment

Hi Paris and thanks so much for your comment. I agree that epigenetics puts environment and environmental insults front and center as the cause of mental distress or suffering. (I am familiar with Bruce Lipton’s work and attended a fascinating lecture by him earlier this year.) And, yes, epigenetics will most likely rehabilitate Lamarck and his work. But epigenetics also validates certain aspect of the biological perspective as well, showing that the environment does change one’s biology and those changes are passed on. Epigenetics shows that altered gene expression is transmitted to future generations, and not just through the modeling and repetition of dysfunctional parenting (which, I am sure, does happen), but genetically as well. So, the original sin, or the trauma that originated from the environment, people, life, etc. becomes embedded in one’s physical body and in each subsequent generation, the person with altered gene expression becomes more vulnerable to new environmental insults, bullying, rejection, exclusion, social defeat, etc., leading to further degradation of gene function until, several generations down the road, someone breaks down. Does it follow that the parents did it, or probably did it? I do not believe this is what you intended to say. I actually liked your article very much and I am totally against making parenting issues a taboo subject. I am just arguing for balance and for being open to the whole truth.

Report comment

Hi J,

To me what Open Dialogue proves is that it’s not an ‘illness’. I think that family or no family problems can be sorted out.