The ‘problems of living’ that Szasz identifies as being referred to as ‘mental illness’ are, in his view, the inevitable consequence of the ‘moral conflict in human relations’ (1970, p 24).1 For Szasz, therefore, mental disorders are patterns of conduct or behaviour that are not just baffling or eccentric, but are identified as problematic by the group or society in which they are embedded. So one way to understand ‘mental disorder’ is to ask what sort of social problems are referred to in this way. In other words, what social functions do services for people with mental disorders fulfill?

Here are some further examples (in addition to the one described in the previous blog in this series) of the sort of situations that occur frequently in mental health services:

A young man becomes increasingly obsessed with religion. He can’t concentrate on his studies and has to drop out of college. He starts screaming and shouting about God in and outside his house, and at one point he pins his terrified mother to the floor, shouting at her to confess her sins. He then drags his sister out of the house still shouting and the police arrive and apprehend him.2

A professional woman with three young children starts to become increasingly preoccupied with writing poetry, to the extent that she loses interest in her children and in the ‘practical details of living’. She starts to express the idea that there has been a world catastrophe that she is responsible for, and she describes feeling afraid but also having a sense of importance. She talks to an imaginary companion, but has no desire to communicate with real people. She is admitted to hospital in a ‘rigid catatonic condition’.3

A man starts to believe there are evil spirits in his house and that he needs to decontaminate it. He starts lighting little fires in the house, and then lights a large fire in the garden, which burns down the whole garden and might have spread to the house or neighbouring properties had the neighbours not called the fire service in time.

Following retirement and the death of his wife, a man becomes depressed and stops looking after himself. Gradually he does less and less until he is found by his children in a state of advanced self-neglect. He is admitted to hospital and then a care home, where he is reliant on full-time care for several years.

In the last blog in this series, I suggested that some forms of mental disorder involve a loss or alteration of normal reasoning processes. Although this is distinguishable from the consequences of brain disease (not simply a depletion of abilities, as described in another previous blog), the cases described above illustrate how the social consequences can be similar. Like some cases of brain disease, the behaviour we refer to as mental disorder can render the individual unable to look after themselves, or liable to behave in ways that others find disturbing.

As I have described in another earlier blog, we can learn much from looking at history. In particular we see that these sorts of problems have beset society for centuries, and we can perhaps also learn something from the ways in which former communities dealt with them.

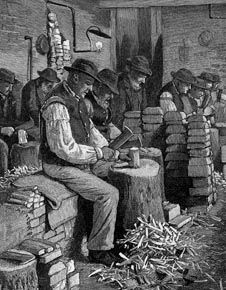

One of the first formal systems for looking after people who were unable to get by was the English Poor Law, which was first passed under the Tudors. This consisted of a bureaucratic system centering on the local church or Parish. Parish officials administered the Poor Law, collecting taxes (rates) and distributing the proceeds to local people who needed assistance. Recipients included families of people who were unable to earn a living or fulfill other familial duties due to physical illness, frailty or a mental disorder. The officials were also charged with maintaining social order. If an individual was felt to pose a danger to the community, and the family could not guarantee the community’s safety, the Poor Law officers could, for example, arrange for a neighbour to keep the individual securely locked up until such time as they had recovered.4

There was also a county-level system charged with keeping order administered by locally appointed Justices of the Peace — later called magistrates. Justices of the Peace could, in extreme cases, forcibly remove someone to a local prison or prison-like facility (e.g. a House of Correction). The local rate payers had to pay for this, so it was generally used as a last resort, and people were brought back when they could be.

These systems involved contentious decisions about the rights and entitlements of individuals, balanced against other individuals. They were accepted while communities were still small, and people knew their neighbours, but started to break down with industrialisation and urbanisation in the 19th century. These developments created rising numbers of dispossessed migrants, who lacked a family network to support them, and as the financial burden of caring for the poor increased, rate payers became increasingly disgruntled, convinced they were being swindled by hordes of idlers.

The idea of mental disorder as a disease starts to take hold in the context of changing attitudes towards poverty. In place of the traditional view of poverty as the inevitable consequence of a hostile and uncontrollable nature (drought, famine etc), the emergence of capitalism recasts it as a failing of the individual. French philosopher, Michel Foucault, echoing Marx and Weber’s analyses, traces how attitudes to madness were transformed in response to the emergence of Protestantism, and the beginnings of capitalism. As industrial production starts to emerge, hard work and discipline become the cardinal social virtues. Any condition that threatens to contaminate the work ethic must be corrected.5

Thus the English Workhouse was designed to deter people from seeking state assistance, and once they had, to ensure they were inculcated with the values of hard work and discipline, which they were assumed to have lacked. The Victorian asylums were an integral part of the Workhouse system, designed to care for poor people who could not tolerate the harsh conditions of the Workhouse, or whose behaviour was disruptive to Workhouse routines.6

In this context, madness, previously viewed as an interesting, if inconvenient, manifestation of humanity, comes to be seen as a social problem in need of correction. A ‘cult of curability’ emerges,7 with the new asylum system hailed as the solution that would teach the mad the error of their ways.

Like Szasz, Foucault suggests that medical explanations for madness and the medical approach to treatment are grafted onto an older system of social organisation and control. Once medicalisation takes hold, it obscures the underlying functions, but the system remains, in essence, a moral and political enterprise.

Then, as now, the aims of this system are to change or manage behaviour that is inconvenient or socially disruptive. Sometimes the individual welcomes support to change, but often they do not, and there is conflict between the desires of the individual and the interests of the community. This is the core of what psychiatry is about — a system of control and care, inherited from the past, that attempts to balance the needs of individual and community. Psychiatry, and the medical framework it brought with it, legitimated this system at a time when it was being increasingly questioned. The medical framework has then expanded the remit of the service by pulling in other social problems and personal distress that can now be reconceptualised as medical conditions.

In my view, the evidence does not support the claim made by some that the medicalisation of the ‘mental health’ system was brought about by a conspiracy of doctors or psychiatrists.8 The aspiring alienists of the 19th century were not particularly influential, and would likely have had little success if their claims were not consonant with wider political attitudes and interests. Evidence from the early 20th century suggests psychiatrists were skeptical about government efforts to medicalise mental health laws.9 Medicalisation occurred because it was politically expedient, because it provided a simple solution to awkward political problems.

The question of how a modern, caring society should respond to the problems that are associated with madness or mental distress continues to present us with serious challenges. What should be done if someone is unable to sustain themselves? How do we judge if they are really unable, or just unwilling? Do we owe people a ‘duty of care’ even if they don’t want our help? How muddled do people have to be for it to be legitimate to make decisions on their behalf? How should behaviour that disturbs or threatens other people be addressed? Do we have a right as a society to try to prevent individuals from causing harm, even if they have not yet done anything that could easily be addressed by the criminal law (as some argue that societies have always tried to do10)? How do we stop some of the individuals described above, for example, from causing injury or aggravation to their relatives or neighbours?

The criminal law is not adapted to address the behaviour of people who are severely disturbed. Most criminal offences require that the accused has a ‘mens rea’, meaning they can employ commonplace reasoning processes to form an understandable intention of committing a crime, or can recognise the likelihood that a crime will result from a particular act or omission of an act. Where reasoning processes are disturbed, and someone does not initiate actions following usual principles of logical thought (as described in the last blog of this series), they are not regarded as possessing the mental capacity required to take responsibility for their actions. The mental health system can be seen as filling the lacunae of the formal criminal law, but not necessarily in the fairest and most transparent manner.

Of course we also need to ask ourselves what it is about the structure and culture of modern society that may foster or contribute to the problems referred to as ‘mental disorder’. The solutions involve changing the nature of the society we live in, as well as trying to ameliorate the problems themselves. I have no doubt that a society with a more equitable distribution of wealth, with opportunities for everyone to engage in meaningful and valued activities, with structures that enable communities to be inclusive and supportive, would reduce the trauma, abuse and isolation that nurture mental disorder and help people to build the confidence, self-esteem and mutually rewarding relationships that protect against it.

Nonetheless, I think any society, however Utopian, will have to deal with some of the sorts of problems that mental health services are presented with today. I do not have a blueprint for a fairer system, and I think the survival of the mental illness concept is testimony to how difficult the issues are, and how strongly societies and governments want to avoid having to confront them. But surely it is not beyond the capacity of the modern world to think of a better system? And having an open and inclusive discussion about alternative approaches is where we need to start!

We could start by disconnecting the need to detain people who are creating problems from the idea of forcing “treatment” on unwilling detainees. What’s wrong with the idea of “keep[ing] the individual securely locked up until such time as they had recovered?” Why does holding someone who is threatening to burn down the house imply enforcing drugs or other violent

“treatment” on their unwilling bodies?

Report comment

Psychiatrists would say that what is wrong with that idea, Steve, is that they KNOW they have treatments which will make the detainee better, and it would unethical not to administer them to a patient who, after all, does not know what is best for them. And that dishonesty is a problem that absolutely demands a different role, with different powers for psychiatrists. In the panic and distress of the consulting room, they can and do say anything – things like “this serious illness is caused by a biochemical imbalance which is treatable”, and “all the evidence suggests that you cannot recover on talking therapies alone”. I kid you not, this is the NHS in 2018.

Report comment

People who lie whenever convenient have no right to public trust or any powers at all!

Report comment

I did Recover on Talking Therapies alone but you wouldn’t know this from my Records (historical or otherwise).

Galway, Ireland, November 1980:-

“..The patient was co-operative well orientated with intact memory. He had mildly agitated psychomotor behaviour. There was no evidence of any florid psychotic features…”

Admitting Doctor 1980 Dr Fadel

Galway, Ireland, November 1980:-

” ..Presented with aggressive behaviour, paranoid delusions, ideas of reference and auditory hallucinations…”

Dr Donlon Kenny 1986 – to the UK

DR WRAY NEWTON MEDICAL, CENTRAL LONDON OCTOBER 2012

“…Eye contact normal currently functioning, no sign of self neglect

mildly agitated but no sign of thought disorder…”

MY COMMENTARY

I have never had an eye contact problem, I have never neglected myself, and I have functioned completely normally in the 30 years I have been in the UK.

I was not mildly agitated, I was unhappy with the misuse of my personal information. I have not suffered from thought disorder in my 30 years in the UK.

Report comment

Threatening people with knives is illegal regardless of motivation. That first example Joanna presents might benefit from a serious talk with a clergy member who would point out how unChristlike and unBiblical his behaviors are.

Report comment

I agree that we should give people time to recover without drugs, as some people will certainly do. However, where psychosis is protracted I do think it is worth trying the use of antipsychotics. I think these drugs can sometimes suppress psychotic symptoms enough to enable individuals who are wrapped up in their psychosis to interact with the outside world again, and resume a more ‘rational’ form of behaviour and communication. If people then feel they would rather not take the medication, I completely agree they should be able to stop it.

Report comment

What you recommend almost worked for me Joanna. A small amount of the neuroleptic Stellazine helped me overcome my intense anxiety in college after years of bullying in high school. After a month I really didn’t need it any more. I was making friends and doing much better.

My shrink disagreed and fed me the “chemical imbalance” lie. Two years later I had sexual thoughts I wanted to suppress and he gave me Anafranil. It caused psychotic mania–which he swore was impossible. I wonder if I will ever have a life now. 🙁

Report comment

@Rachel777:

Is your other pseudonym here FeelinDiscouraged?

I was labelled “bipolar” when I was 16 due to mania caused by sertraline prescribed for anxiety. That label is a lie. Labelling people with defamatory labels and robbing away their truths for drug induced occurrences is something psychiatry commonly does. It isn’t so much the prescription of the sertraline I was worried about. It’s everything else that came with and after it.

I have been harassed, abused and gaslighted for years because of the labels I have (I’m not talking about psychiatry) which are a lie. I cannot even get justice from said abuser because I’m labelled with DSM garbage.

It’s not so much that I have not had anxieties or anything. But that’s the thing. You enter, or you are made to enter, into these systems with one problem. When you come out, you have two more.

I am still living with so much dejection and pain everyday. Not many people can understand this, except some folks on here. Despite having people all around me, and talking to so many people, it’s like living a bit of a lie.

Report comment

My condolences.

I feel a lot better since getting off drugs and relocating. I’m building a writers portfolio and hope to (finally) get off SSI.

Still pretty sick. If I had taken large amounts of heroin or meth for 20+ years my health would be poor too. Not proof of a meth deficiency. 🙂

Nearly all my problems are physical. That throws everybody off since they “know” non-compliance means psychotic mania or suicidal depression. Not severe anemia, allergies, and exhaustion.

The anemia actually started before my taper. I believe long term SSRI use has damaged my digestive system. Of course no doctor dares to say this. Did I mention I distrust the medical profession?

Report comment

Yes, I’m Feelindiscouraged. Not trying to raise up a sock puppet army, but my short term memory is poor. Hence pass word problems and multiple accounts. Plus Feelindiscouraged was a negative moniker.

Report comment

I agree that the name change feels more positive.

Report comment

@Ms. Moncrieff:

You have given a few examples: two of them being a man obsessed with religion and a woman whose delusional thinking starts with writing poetry. In the hands of psychiatry, both these individuals will be labelled with some or the other DSM rubbish. Schizophrenia or what have you. Don’t you think the best way to provide any form of help to them would be to not rob away their truths by labelling them with a lie (irrespective of what the clinical definitions of the DSM labels applied to them are; in the future if being a psychiatrist was a social sin defined as Ethics Deficit Disorder, it would have clinical definitions and a barrage of journal papers and brain scans to go along with it too) right at the start and see their problems for what they are?

The person and his/her family members will see the label and have a false sense of having some sort of an explanation when it isn’t. Family members with bad intentions will misuse the term in a false manner.

Also, there is no context with regards to why those people got obsessed with religion or poetry. What were the preceding events? What else are they surrounded by? Why the obsession with religion and not with the weather for instance.

I agree with you that drugs used for a short period of time may have some positive benefit assuming they don’t do other horrible things. But what after that? What about the consequences of the labelling? The consequences of having become a part of the psychiatric system and it becoming a permanent fixture in one’s medical records? The indoctrination of families that comes with it?

What if the person wants to take prescription-only drugs without psychiatry as a middleman (because there are a lot of things that come with simply getting a prescription)? What when they want to taper off of them?

See. Ordinarily, a person in a phase of distress will have some issue for which, if they are in the right mind to see it, they will seek some form of assistance. Depending on the problem, it may be going to the police, going to a drug store to buy pills, talking to a friend etc. If they are not thinking rationally, for the time being, there will be an intervening force in the form of some or the other people related to the person.

How does one eliminate psychiatry as an interfering agent between whatever the person wants as help?

Report comment

Schizophrenia is a Long term serious and chronic disorder more disabling than being blind or in a wheelchair – But can be proven not to exist with the right kind of non chemical help.

Report comment

Both their behavioral patterns were hurting not just them but those around them.

I love poetry. I am deeply religious. But my religion teaches me to love my enemies–forgive the psychiatrists and others who have wronged me. I wish I could!

It never has caused me to hold a knife to someone’s throat screaming at them to repent. I know these things happen, and they baffle me. For me, my faith has been a center of sanity in the craziness of the psychiatric system.

Poetry also helps me. There is actually a field called poetry therapy that helps people get a grip on emotional pain through writing poems.

Report comment

In one of your post above you stated that you feel that SSRI’s are the cause of your stomach problems. This is interesting since the place in our bodies that we have the most serotonin is the stomach. It makes perfect sense that something that affects serotonin levels would affect the working of your stomach. And psychiatrists know this but deny any connection at all.

Report comment

Well, Jesus was right when he said that the Kingdom of God is within you- it occupies a small space near the top of most people’s right temporal lobe, which is why you might want to take our man of God to a neurologist first, instead of a shrink, as there might be something physical affecting or irritating the activity going on in God’s suite. You’d better hope not- treatment may cut off access to God’s place, so our sufferer may be noncompliant for obvious reason, once he discovered he’s being cut off from God’s influence, as well as His world.

Report comment

Dear registeredforthissite,

I agree with you that labelling someone with schizophrenia or other diagnosis is not helpful and can be damaging, particularly because people fail to realise (psychiatrists often included) that the label does not refer to an underlying entity or cuase of the beaviour, but is simply a description of the behaviour. And I agree that it is important to try and understand the meaning of the behaviour, and how it relates and responds to the individuals current circumstances and personal and cultural history. I agree this is an important part of trying to help people, as I stressed by referring to the work of RD Laing and other in my previous blog. But i think we should not hide from the fact that what we refer to as mental disorder can soemtimes cause real distress and distrubance to people (individuals and those around them) and sometimes actual danger, and I think some sort of social response is needed. I think this could be done by a variety of agencies. Possibly it could be done by family and friends, but my experience is that they often feel overwhelmed and are desparetly looking for help. I suppose I am really just arguing for an open and transparent debate about how we address these situations fairly, in a way that causes the least damage to the individual, but also respects the needs of others.

Report comment

Hi Joanna,

I’ve just come across this article and haven’t yet read all the comments (or your other blogs) so forgive me if I touch upon something that has already been said.

For me, personally, there is no reason at all to label anything as a ‘mental disorder’ or ‘mental illness’ – that doesn’t take away from or detract from the possibility that certain experiences in life can be extremely distressing.

One of the problems, from my perspective, is that the moment we label, or think we need to label something as a ‘mental disorder’ is that we are automatically putting a lid on understanding what is really going on for that person – in a way that allows us to understand and respect their internal, subjective experience.

It is almost always (probably always) the result of a lot of things that have happened for a person in their life to reach a state of being so desperate that things start to “look strange” from the perspective of someone who has never been through these sorts of things or who has been through only labelling – never given the space to understand their experience.

“Schizophrenia” isn’t really a description of anyone’s behaviour, ever. It’s a label that ends up being given to people in particularly powerless situations. Some people end up being labelled with “schizophrenia” while others manage to avoid this label, quite irrespective of the types of thinking and behaving that might have occurred at times in a person’s life. There is something of a hierarchy of labels, with avoiding a label altogether (being lucky enough to find understanding people to help with a crisis) being at the top, then going “down” through the labels like ‘trauma’, ‘complex trauma’ ‘nervous breakdown’, ‘brief psychotic disorder’ etc etc with “schizophrenia” all the way down the bottom. It’s a label that (to me) says ‘a person who was unable to find someone who was willing to genuinely understand them in a relatable human-to-human fashion and ended up being slapped with this label’.

As Mary Boyle points out in her book “Schizophrenia: a scientific delusion?”, many people engage in some behaviours like “other blaming” as an explanation of what is happening in their life – eg some groups of people might blame their personal socio-economic situation on ‘immigrants’ – as bizarre and unconnected as this might seem, it’s not labelled as a ‘delusion’ in a clinical sense despite it being an impairment in logical functioning. In our society we have diverse ranges of groups who engage in what other groups might see as ‘delusional thinking’ – like ‘flat earthers’ for example (yes, that’s a thing). But so long as they remain within groups, these people don’t get labelled as ‘schizophrenic’ – that only happens when people are isolated, alone. Pick a ‘flat earther’ off from the herd and yes, a psychiatrist would probably call them ‘delusional’. But it’s quite ironic really, given that psychiatry itself has a long history of believing in quite delusional things (including, some might argue the notion of ‘schizophrenia’ itself).

Reading between the lines, it seems to me that what you are trying to get at is the idea that sometimes people can experience severe distress in their lives, and that sometimes people in such a state might want to reach out for an understanding human to help them feel safe again and make sense of what is happening.

With this I agree. But there is no need to label that distress a “mental disorder” – it’s ok for it to just be normal human distress. Being ‘normal’ doesn’t mean the experience is not painful, hurtful or frightening. It doesn’t mean the person doesn’t need or want help and support. It just means that it is a part of the rich tapestry of human experience. It is one of the “normal’, “expected” and “usual” things that a person might experience in life.

One of the things that (many) psychiatrists have been slow to cotton onto is the idea of trauma. We all seem to understand trauma well enough when it comes to physical trauma – eg. my leg is injured. But not so much with the idea of emotional trauma – eg. my psyche is injured. Some people – in all walks of life, including some with a psychiatric background – have done a lot of work in this field. They’ve come to understand that when human beings are very very frightened and hurt, they need to feel safe again. In Australia we have the “Blue Knot foundation” and various other trauma groups that help understand childhood trauma and how to help people heal again.

I’ve found these people and their ideas very helpful – but that doesn’t mean I wan’t to be labelled with ‘post traumatic stress disorder’ or ‘complex post traumatic stress disorder’. Why would I want or need such a label? If I have a broken leg, I heal my broken leg and get on with my life. If I have an injured psyche, I should be able to get help from sensible people who can help me make sense of my injured psyche and get on with my life. I shouldn’t need to be forever thinking of myself as having suffered from some ‘abnormal’ experience.

Psychiatry and the concept of the “mental disorder” have done a lot of harm. Some of which we are only starting to wake up to. For example, let’s say some things in my life have mounted up to the point where I am sad a lot of the time. In a world where people are sensible and try to understand and help me put my situation in context and heal and learn from it. I can learn to understand why I’m feeling sad and powerless and get past this period relatively quickly. Everyone else can do the same. There’s room for this in life. It’s normal. There would never be a need to declare on any medical questionaire – for any job, not even going to an extreme environment like Antarctica – that I had such an experience because there would be an understanding that such things were a normal part of life. That we learn and grow and even get stronger from them.

Compare this to the idea of ‘depression’. A history of labelling people with ‘depression’ and giving them drugs and the belief that they have a thing called ‘depression’ has created a society where being sad and not knowing why is not considered ‘normal’ – we can’t just start from -ok we don’t know yet so let’s figure out why you’re sad and how to overcome it. The idea of ‘depression’ hasn’t worked out (research shows that believing in ‘depression’ gives people less coping skills). So statistics start to show that ‘depression’ keeps coming back. Now people testing for resilience will want to know if a person has a ‘history of depression’ and so forth. There is an understanding that these things are not a ‘normal’ part of life. That we don’t learn and grow from them. That they weaken us.

That is the world that the ‘mental disorder’ has created. We don’t need it. That doesn’t mean that there is not room for ‘helping’ professions. It just means that there is a deep need for a radical retraining in the thinking of some of these professions to stop thinking in terms of ‘abnormal’ or ‘disordered’ or ‘pathology’. The type of thinking that requires one person to see another person as ‘diseased’ or ‘disordered’ takes a step back from that person, from being able to relate to that person with whatever they are going through. That means taking a step back from actually helping that person.

Conversely the type of thinking that allows a person to step forward and understand another person, relate to another person, recognise that person’s experience as entirely normal is taking a step towards helping that person. We stop making that person ‘the other’. And that is, in itself, a powerful and essential thing. A thing we can’t do unless we ‘drop the disorder’.

For people who have been trained their entire lives to ‘otherise’ people this takes a lot of inner work. To recognise the way that we distance ourselves from other people and their distress by describing it ‘from the outside’ while we describe our own experience ‘from the inside’. It takes a lot of work to be willing to change our perspective away from doing this but it is essential. Without learning to understand and relate to other people we can’t help them. And the idea of ‘mental disorder’ is all about labelling what ‘they’ are going through as ‘maladaptive’ without recognising just how ‘maladaptive’ we are being when we do that labelling.

As for a ‘social response’ – in a space where people become very skilled in understanding other people and making them feel safe there isn’t any need for coersion and force. But the ‘workforce’ charged with ‘social response’ and ‘intervention’ are typically not skilled in understanding people – particularly people in severe distress -but in a false paradigm of ‘diagnosis’ and ‘treatment’ with neuroleptics and worse yet ECT. They aren’t people who have done a lot of work in understanding the subjective experience of other people in distress, but who have rather done a lot of work in distancing themselves and labelling people (which is quite the opposite). They aren’t skilled in creating a sense of safety but in creating an environment of power and fear. A lot of the ‘interventions’ involve coersion and force as well as over-reliance on neuroleptics that doesn’t make people feel safe, thus worstening trauma and hence worstening the ‘symptoms’ of trauma. Neuroleptics might be able to ‘dull’ things for some people but for others they make them feel less safe (particularly when administered forcefully by violent strangers in a highly unsafe environment) and they don’t address or attempt to understand what is going on for that person that is making them feel unsafe. If a person is used to relying on their wits for survival and a group of violent strangers is trying to dull those wits – that person isn’t going to feel safer. The story of intervention has been a long story of the wrong people doing the wrong things.

A person who is going through severe distress should be able to have access to help, support, safety and understanding. But it is going to take a lot of work and a lot of rewiring the brains of those who genuinely want to work in ‘helping professions’ to make this possible.

Report comment

Fred77’s comment is spot on.

The Diagnosis–>Disorder–>Treatment model is disastrous, because it “otherises” and makes people thinks their brains are broken, which means they may never really feel fully better because they will always define themselves as having an abnormal brain.

Thats why “recovery starts with non-compliance” is so true: once you’ve decided (and there’s loads of evidence) that it’s psychiatry, not you, that has lost the plot you can feel the hope that you aren’t broken.

The problem with “illness” and “disorder” is that, given the treatments have such doubtful efficacy, it sounds permanent and is therefore debilitating, when these problems are very likely episodic relating to circumstances or stage of life.

I honestly believe that voice-hearers aren’t just normal, they are special. I don’t have evidence for that, just as psychiatry has no evidence that they are disordered. But its a much more helpful belief, and there most certainly is evidence that if you believe something helpful then you will get better faster.

Most of us can only function because of some of the “disordered” beliefs we have. God? Praying? Heaven? Ritual? Love? Nah, those don’t make sense!

As an aside, I shudder when I recall the long monologues from the psychiatrist about how the paranoia and anxiety was an abnormal, “serious psychotic” illness that was “psychiatric” not “psychological”. But as time rolls on it just becomes laughable.

I thought Fred77’s contribution was really well put.

Report comment

Dear Dr Joanna,

I initially refused drugs and requested the talking treatments but after being on long acting injection for a number of years it was extremely difficult to stop.

Coming off “medication” can be extremely difficult. A person might need several attempts and a lot of help in doing this.

There’s probably no reason other than policy, that most people can’t learn to cope at the start with non drug help.

Report comment

I have a friend with a “Diagnosis” and on a present day Long acting injection. His appearance and manner is well above average.

But when he tries to discontinue the “medication” he quickly runs into trouble – and the people around him are not very sympathetic.

If he doesn’t come off these drugs they will eventually destroy him. It is possible to come off a Long acting injection carefully with the help of practical psychotherapy but the “Mental Health System” is totally out of its depth in dealing with situations like this.

No other medicine that I know of in the UK has this type of dead end approach.

Report comment

Just on the drugs: isn’t the effect size for antipsychotics, in particular let’s say Quetiapine, so low that most of the effect must be placebo?

Back to main thrust of this thread, the issue of undue influence. Helping people when they are struggling mentally seems to me to require a higher standard of evidence, guideline adherence, and transparency. And if its not black and white, there must be choices?

Report comment

Joanna, the point you have failed to state is whether or not this so called treatment is voluntary. Also who is to say what is rational? Is it rational to believe that Jesus lives in my heart?

Report comment

About 3% of the UK Population are now “Severely Mentally Disabled” and receiving Psychiatric Drug Treatments – so this is now, what Mental Disorder is.

Even if a person takes “medication” at the beginning, they can still make long term recovery but how many doctors would allow them to? Or how many doctors would know how to help them to do this?

According to my experience ALL people should be able to make Full Recovery without Psychiatric Drugs. It’s the medical system that’s blocking the process.

(Genuine Social Problem or Mental Health Issue would only apply to a very small fraction of todays “Severely Mentally Disabled”. Kidnapping might be the right description).

Report comment

I disagree with using any antipsychotic for hallucinations. You are essentially training the brain to rely on this “toxin” to recover instead of using a couple benzos to maybe take them down a little. They shut off the dopamine production in the brain and have been shown to shrink it. This can’t be good in any dose. Doctor’s will never utilize this drug in small quantities. The profit is too great not to fall into the trap of increasing the revenue of this drug. Like LSD, make it illegal and stop the production of it. It causes atrophy of the brain, Andreasen and Ho.

Report comment

Bruce Levine has the same opinion.

I believe that there might possibly be SOME benefit to using small amounts of neuroleptics for 2-4 weeks. Like pain-killer. Not insulin!

No psychiatrists are open to this idea however. So folks in emotional crisis just need to hide till they feel better. Disgusting how we punish the weak and suffering!

Report comment

If you are saying that it has something to do with our present society valuing propriety over freedom I would have to agree with you…but not it.

You are weighing in in favor of some kind of social control, beyond law, criminal law, it seems to me, and I would not be doing so.

I see a lot of exaggeration taking place in the name of “mental health”, and, frankly, I would go in the other direction, that is to say, I would downplay the matter rather than turn the problem of problem people into a runaway and thus unstoppable industry.

What was done? These huge asylums were built to contain, and keep hidden, the problem. Essentially they came to serve as the rug under which society swept it’s unwanted castoffs. If you accept the human about us as a whole, in my opinion, you go in the opposite direction.

“Supports”, “help”, blah blah blah, “the community mental health system”, much of whining nanny statism, etc., in general, these matters are part of the problem and not part of the solution.

Report comment

For those who physically assault others or commit arson there’s the legal system. Many “symptoms” in the DSM are actually crimes. Or simply rude behaviors.

Prosecute the offender as a criminal or treat them like you would a less eccentric boor. They will be better treated as ex-felons than “bipolars” or “schizophrenics” so you can’t argue inhumanity.

Report comment

You are weighing in in favor of some kind of social control, beyond law, criminal law, it seems to me, and I would not be doing so.

Ditto.

Report comment

Hi Frank,

I used to be against any form of social control (in addition to the legal system), but having worked for a long time with people with serious ‘mental disorders’ I have come to conclude that it is sometimes necessary. I don’t think using the criminal law is fair or adequate in situations where people are too confused or preoccupied to appreciate the effects of their actions and yet I think that the community sometimes needs protection from danger or disturbance.

My concern is that portraying these situations as medical conditions obscures what is really going on, making it impossible to devise a system that is fair, or as fair as possible, to all concerned.

Report comment

I’ve seen situations in the USA where people were locked up by these Assertive Community Treatment teams, these teams assembled to provide care for those considered most disturbed and less able to care for themselves. My concern is protecting people who find themselves in such situations. Like so many other people in the system we are talking about people who are victims of a leap to judgment. Technically, one might call “addition to the legal system”, the illegal system, there are so many constitutional rights violations involved. Calling such treatment “social control” is being honest about it. Calling victims of this illegal system “people with serious ‘mental disorders'” is being dishonest about it. I just think this extra-legal system of social control an illegal system if it would undemocratically support the rights of some people at the expense of the rights of other people. Calling upon medical authorities for social control purposes, automatically we are seeing the medical profession called upon to break the maxim that insures good care, “First, do no harm.” Secondly, there is the dishonesty involved in calling your morality police force medical doctors. “Sometimes necessary” covers a lot of ground, too much in my estimation, especially when in this country a person is deemed innocent until proven guilty. The “mental health” system, as it is not subject to due process, throws open the door to all sorts of abusive behavior on the part of the authorities and the state. I just don’t think effective rights protection, were it possible, would permit such social control practices as those that you would be excusing.

Report comment

Hi Frank,

Thanks for your reply. You make some really important points. The system of social control that psychiatry currently enacts is highly contentious, and that is why it is convenient to diguise it as medicine. I agree with you that it is wrong and dangerous to label it in this way or put doctors in charge of it. And I agree that devising any system that is consistent with human rights is really challenging. But I think it is difficult to say we should dismantle psychiatry and do nothing. I think there are situations where it is reasonable for society to have a response of some sort and I see no reason why ‘due legal process’ should not be part of this. In fact it is essential, because as you point out there are many fuzzy areas and the potential for abuse.

Report comment

Polite society is good at launching witch hunts while witch society is pretty slim to non-existent if not inconsequential. When “mental patients” cease being considered, as they have, members of the public, I think you can begin to see what kind of a problem we have generated for ourselves. One social problem, as with “medicalization”, right now is how “society” is dealing with some of its “problems” and/or “problem” “members”(?). Disenfranchisement and ejection/rejection, on top of this situation, must compound the matter a great deal. I myself see a big problem in that part of the population that would designate another segment of the population the problem population.

Report comment

A major problem, Joanna is we have a one-size-fits-all solution for those labeled SMI. No real distinctions are made between the violent and nonviolent, the out-of-touch and the eccentrics (who probably don’t need any help at all), the anxious and the angry. The examples you describe only fit maybe 5% of the “mentally ill” at the very most.

Something no one mentions is the mass shooters usually had histories of violent crimes. But no one takes little things like that into consideration when drafting crappy legislation.

Report comment

The majority of the huge UK “mentally disabled” population would have had transitory problems to begin with, but are now trapped in longterm psychiatric disability – as a result of psychiatric treatment.

I dont think people trapped in long term psychiatric disability would just recover by coming off “medication” – they would need a lot of help as well.

In my own case there’s no reliable evidence of any original mental illness. I came from England to Ireland and the English doctors were extremely “noncommittal”. My recovery after a number of years of disability in Ireland was as a result of rejecting psychiatric treatment.

I’ve been well for 30 years in the UK but my GP Surgery Newton Medical, London W2 have been attempting to promote an “Unwellness” idea regarding me.

Its not for genuine reasons as my GP Dr Simons knows that my main work in the UK is on Building Sites. It’s about “bent” behaviour in “Mental Health”.

Report comment

Emotional suffering and other natural “problems with living” are predominately solved with more social and economic justice. However, this is a far more monumental task than you imply in your article. Our society is often cruel and unjust at the bottom of our “social pecking order;” we lack the will to address social welfare problems far more than the means.

Report comment

Well said!

Report comment

“Social welfare problems”? I’m not a fan of the throw money at it, and it will go away theory. I just don’t think it works. Throw money at a problem, and you’re funding it. Now what we’ve got is an entire service industry growing up around the idea of “homelessness” and people not being able to take care of themselves. This industry is doing anything but providing affordable housing, as well as independence and self-sufficiency. What it is doing is perpetuating itself, and the population that it thrives upon, the so-called “needy”. Treat adults like children, and what do you get? Of course, adults who act like children. Treat adults like adults, and once again those adults have rights.

Report comment

How about creating a society where people who have jobs are able to afford living, like we did in the 60s?

Report comment

That would be great, for a start, but then…

How about creating a society where all people had jobs? I don’t think we had that even in the 60s.

Who is served by unemployment? Corporate interests I would think. What do they get out of it? 1. a surplus labor force, the old Marxist thing, growing less important all the time, 2. a scapegoat, 3. deflected scrutiny, 4. increased mechanization, 5. maximized profits, 6. bought politicians, 7. tax cuts for the rich, 8. an aim for philanthropic efforts, 9. a country of suckers, 10. bought institutes of higher education, 11. stiff competition for jobs within the monopolies (stifled competition), 12. gated communities and slum lords, 13, oligarchy (government by, for, and of the rich), 14, disenfranchisement of the vast majority of humanity, 15. elite status and privilege, etc.

Not to fear, the terminator is coming.

Report comment

I’m not really disagreeing with you but there were societies where everyone had a job. Remember the communist countries where everyone had a job and the results were that the products that were produced were of faulty quality compared to products from supposedly free countries. Even China doesn’t seem to be working under this principle any longer and allows some little experience of free enterprise. What do you think about the programs being tried in some places where everyone is guaranteed a basic income, no matter what and they can do whatever they want with the money?

I no longer believe in capitalism which has become cannibalistic in many regards due to the corporate interests that drive it so fiercely these days. I seriously don’t know what to believe in at this point. Some places still carry on modified bartering, in smaller communities where I live. They’re kind of experimental at this point but are having some interesting results. But, this obviously is not practical on a national level these days.

Report comment

The argument of capitalism versus socialism aside, ending political corruption in this country is going to be a matter of getting the money out of politics. Corporations should not have been given the same rights as individuals because people are harmed thereby, but it is big money that created this problem in the first place. Big money that has much less influence when election campaigns are paid for in a more democratic fashion, that is, by the people, and not just the rich people.

Report comment

Frank, you might also consider….

1a) When supply and demand of high enough wages are persistently high, increase the supply of people that will live in groups in a small place and live with less by allowing more H1B visas, and therefore increase the price of education in this country to compete with the new work force and decrease overall wages for jobs requiring higher levels of education.

Report comment

Psychiatry “helps” people in one way by banishing them from the workplace. Disabling people who would gladly support themselves otherwise, forcing tax payers to shell out $$$$$ for the drugs and other crap the shrinks provide. The shrinks are bigger drains on our economy than any welfare recipients.

Their greed is insatiable too. How many crippled young people are enough Dr. Quackenbush? 20%? 25%? 33%?

When shrinks rave about all the “mentally ill” not getting the “help” they–the young people–need they are actually filling everyone in on their business goals over the next 5 years. Cha-ching!

Report comment

I think money is earned through “arrangements” and not through “work”. The resources are divided up between interested parties and these would be maybe 15% of the population.

The other 85% of the population are being reduced down. The middle class are becoming the lower middle class; and most jobs are coming under the influence of mechanization.

Report comment

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar creating his own Controversy

https://youtu.be/z2IWmyFhjOE

(Anyone can say the wrong thing)

Report comment

You are absolutely right, Frank. The Fed starts raising the interest rates whenever the unemployment rate drops below 5%. They say it’s because they’re afraid of inflation, but it’s really rising wages they hate. Recently, the rate has dropped below 5% and rates started to rise a little, but wages remain stagnant, so they’re not too worried. I think this is because most of the jobs available pay crap, but in any case, it’s definitely a conspiracy to keep wages low and profits high.

Report comment

Denmark is a country where everyone is more our less provided for from the Cradle to the Grave. It’s a very competitive country and a very ‘happy’ country.

But – the psychiatric abuse is supposed to be as brutal as anywhere else.

Report comment

we lack the will to address social welfare problems far more than the means.

Also the political power, which must be taken, as it won’t be given. But this also depends on how much will we have, and how much we are willing to sacrifice.

Report comment

Yes, and that’s frankly very frightening so it’s understandable why we’re more willing to sit here and talk among ourselves all the time rather than getting out and taking power into our own hands. I admit that it scares the absolute bejesus out of me and it shames me that I can’t seem to take that first daring step to actually do something.

Report comment

Any chance of you sharing your email (or giving Emily the moderator permission to pass it along)? There’s lots of useful stuff that can be done that’s not that scary, but just requires persistence.

Report comment

Oldhead,

I have made one serious allegation after another on this Website against named professionals. As far as I know, I have the reliable evidence to back up the allegations I have made.

Report comment

To be very clear, “taking power into our own hands” rarely means literally “storming the barricades” or any of the many other stereotypical romantic visions people have of “revolutionary” activity. (I wouldn’t know where to find a barricade if I wanted one.)

What we do need, for example, are sophisticated, documentable and easily readable educational materials on psychiatric oppression, drugging, etc., and creative ways of putting them in the hands of the masses. Before there is a demand there must be a clear understanding of what we are demanding and why; next there must be an effective way of drawing the rest of society into our perspective. All of this requires serious preparation and research, not just internet chatter.

Report comment

I agree that social and economic conditions have a lot to do with mental suffering and disturbance, and I also agree that I have not done this issue justice in this blog. We know from epidemiolopgical studies that most mental disorders are more likely to be diagnosed in people who are poor, unemployed, have histories of abuse etc. I agree that being able to contribute to society is essential for wellbeing, but modern work is often exploitative and underpaid, and does not necessarily give people a sense of being valued.

I am also very interested in the experiemnts in universal income. I think this should be coupled with providing opportunities for people to do meaningful and rewarding activities that contribute to the community and whose value is properly acknowledged.

Report comment

This article is sickening, truly sickening. What is most sickening is that Moncrieff understands better than most people the terrible harm that is being caused in the name of psychiatry, and yet she still attempts to justify it.

“For Szasz, therefore, mental disorders are patterns of conduct or behaviour that are not just baffling or eccentric, but are identified as problematic by the group or society in which they are embedded.”

This is simply not true. This supposed summary of Szasz’s ideas regarding mythical mental illness run counter to almost everything that he wrote. Moncrieff’s article begins with a misrepresentation of Szasz, and then a misleading question. I suppose that it’s no wonder that she arrives at such erroneous conclusions.

It should probably come as no surprise that psychiatrists and mental health workers either dismiss Szasz or try to dilute his arguments. Szasz saw through the nonsense that is disseminated in the name of psychiatry and the horrors that are perpetrated in the name of so-called “mental illness” and “mental disorders.” Karl Kraus saw through these lies long before Szasz. But too few people take the time to read and understand what Szasz and Kraus actually wrote. What we have instead are caricatures of their ideas that are used to hide the very injustices that they opposed. What is so tricky about Moncrieff’s justifications for psychiatric abuse is that she couches her arguments in half-truths. Szasz recognized that the promulgation of the myth of mental illness was a political weapon and a method of social control that had nothing to do with healing or medicine. But did he endorse this concept? No. Just the opposite. Szasz championed liberty and responsibility in opposition to the coercion and force that masquerade as medicine. Moncrieff writes as if the concept “mental disorder” describes some underlying metaphysical reality, but this contrasts sharply with almost everything that Szasz wrote.

Whether intentionally or not, Moncrieff overlooks the most basic question: “What is mental illness?” Instead, she assumes that “mental disorders” refer to actual social problems, and that there are social functions for “services” for people with “mental disorders.” The tautology ought to be apparent to any reasoning being: mental disorders exist, and services for people with mental disorders fulfill some social function; therefore what social functions do services for people with mental disorders fulfill? And don’t even get me started about the use of the euphemistic term “services.”

As if this weren’t enough, Moncrieff attempts to support her tautological argument with eccentric examples that are meant to lend legitimacy to notion of “mental disorders.” She claims that these are “the sort of situations that occur frequently in mental health services.” This is simply untrue, and Szasz knew as much. And don’t even get me started about the use of the euphemistic term “services.” Are involuntary incarceration, drugging, abuse, torture, shock, labeling, and slavery services?

Moncrieff’s first example is particularly dangerous because it portrays religion in a negative light in the way that C.S. Lewis understood long ago. Consider this statement:

“We know that one school of psychology already regards religion as a neurosis. When this particular neurosis becomes inconvenient to government, what is to hinder government from proceeding to ‘cure’ it? Such ‘cure’ will, of course, be compulsory; but under the Humanitarian theory it will not be called by the shocking name of Persecution. No one will blame us for being Christians, no one will hate us, no one will revile us. The new Nero will approach us with the silky manners of a doctor, and though all will be in fact as compulsory as the tunica molesta or Smithfield or Tyburn, all will go on within the unemotional therapeutic sphere where words like ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ or ‘freedom’ and ‘slavery’ are never heard. And thus when the command is given, every prominent Christian in the land may vanish overnight into Institutions for the Treatment of the Ideologically Unsound, and it will rest with the expert gaolers to say when (if ever) they are to re-emerge. But it will not be persecution. Even if the treatment is painful, even if it is life-long, even if it is fatal, that will be only a regrettable accident; the intention was purely therapeutic. In ordinary medicine there were painful operations and fatal operations; so in this. But because they are ‘treatment’, not punishment, they can be criticized only by fellow-experts and on technical grounds, never by men as men and on grounds of justice.”

For every 10,000 victims of psychiatric abuse, there may be a case such as is described in Moncrieff’s first example. Even then, such cases are often CAUSED by the effects of psychotropic drugs.

The second case is almost as absurd as the first one. In any case, a poor woman who exhibits such behavior is only at the beginning of her troubles once she is labeled as “schizophrenic.”

The third example is also an outlier, and uncommon. For every 10,000 people who are drugged into oblivion by neurotoxic chemicals, there is one person who thinks that he can drive away evil spirits with fire. Perhaps his method was wrong, but what will psychiatry do with such a case? The man is doomed to some form of psychiatric torture.

Finally, the fourth example is yet another sad demonstration of how psychiatry exacerbates the suffering of innocent people. The man’s wife died! Is anyone so heartless as to believe that mourning and depression might not follow such a difficult experience? Rather than help him through the process of mourning, why did his children dump him off in a “hospital”? Why? Because psychiatry gives people an easy excuse to dispose of inconvenient loved ones.

Moncrieff then suggests that “some forms of mental disorder involve a loss or alteration of normal reasoning processes.” Anyone who is paying attention can see the tautology: Normal reasoning is healthy, therefore abnormal reasoning is a “mental disorder.” How can we be sure that Moncrieff’s reasoning is healthy or normal?

Moncrieff is right about one thing, however. We CAN learn a lot by looking at history. But the lessons to be learned are the precisely the opposite of those that Moncrieff suggests. The history of psychiatry is riddled with lies, deception, coercion, abuse, torture, and even murder. Compared to the suffering that psychiatry has caused, the supposedly abnormal behavior of a few eccentric individuals has done relatively little harm to anyone at all.

I can also appreciate this paragraph: “Like Szasz, Foucault suggests that medical explanations for madness and the medical approach to treatment are grafted onto an older system of social organisation and control. Once medicalisation takes hold, it obscures the underlying functions, but the system remains, in essence, a moral and political enterprise.” But how does medicalization take hold? Szasz explains in many of his works how the old system of persecution by false priests and clergymen has been passed on to the modern false priests of the false religion of psychiatry. Doctors and psychiatrists have taken the place of the clergy. Is this something to celebrate or perpetuate? I think not.

But psychiatry is not just about changing or “managing” the behavior of those who are deemed socially unacceptable. Psychiatry is about DEFINING what is or is not socially acceptable. Furthermore, the tyranny of psychiatry brings almost all human behavior with in its scope and grasp.

The core of psychiatry has everything to do with coercion, force, control, dominion, and torture and nothing to do with “care.” It is not all inherited either. Many innovations and oppressive measures came about during the rise of psychiatry. Moreover, what on earth can possibly be meant by the notion of a “caring society.” “Caring” societies are the most dangerous. After all, it was the Nazi’s who “cared” for the Jews. Slave masters “cared” for their chattel slaves. Is this the kind of “care” that is needed?

“What should be done if someone is unable to sustain themselves?” Please allow me to quote C.S. Lewis once again: “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.” The only “duty of care” that we should be worried about is our duty to take care of ourselves, our families, and our neighbors. We have no duty to torture, abuse, drug, incarcerate and label those whose behavior we find objectionable.

“How muddled do people have to be for it to be legitimate to make decisions on their behalf?” Moncrieff’s arguments in this article are as muddled as anything I have ever read, but she is free to believe and to write as she wishes without intervention from any thought police. As muddled as it is, no one has any right to make decisions on her behalf.

As far as preventing individuals from causing harm… that is supposedly what laws are for. When laws are broken, and crimes committed, there ought to be just penalties attached. But for heavens’ sake, leave innocent, law abiding citizens alone!

“Do we have a right as a society to try to prevent individuals from causing harm, even if they have not yet done anything that could easily be addressed by the criminal law (as some argue that societies have always tried to do)?” NO! What is this? Minority Report? Before the rise of psychiatry, at least in the United States, a person was innocent until proven guilty. Now, under the tyranny of psychiatry, people are guilty until proven innocent. I don’t think that Moncrieff should be arrested for writing this article, so why should other innocent people be presumed guilty?

“How do we stop some of the individuals described above, for example, from causing injury or aggravation to their relatives or neighbours?” A better question might be, how do we stop psychiatrists and mental health mongers from their tyrannical rule over the lives of innocent people? As Szasz often pointed out, psychiatry inculpates the innocent and exculpates the guilty. With the insanity plea and other measures, psychiatry has made it more difficult for people to be held accountable for their actions. Psychiatry is the opposite of freedom and responsibility. Is is slavery and justification for criminal behavior.

“Of course we also need to ask ourselves what it is about the structure and culture of modern society that may foster or contribute to the problems referred to as ‘mental disorder’.” That’s easy. PSYCHIATRY invents and perpetuates the very problems that it purports to resolve or to cure. PSYCHIATRY is responsible for promulgating the myth of mental illness along with all of the train of abuses that follow in its wake. And no amount of utopian speculation will solve the problem. Psychiatry IS the problem. No alternatives are needed. Psychiatry must be abolished. Slay the Dragon of Psychiatry.

Report comment

Fantastic summary of Szasz. Joanna distorts his views and she uses Szasz’s reference as a sort of tip of the hat to alternative thinking while maintaining the status quo. Why do people claim to represent Szasz distort his views? He couldn’t have written more clearly. Never asks man for his honest opinion when his living depends on doing the opposite.

Report comment

dragon…I like what you post…

but I thought that szasz was not anti-psychiatry…

but anti-coercive psychiatry…

Report comment

Szazs looked at “psychiatry” as inherently coercive because it’s based on lies. Honest–sometimes brutally–he did not care for liars.

He counseled people by encouraging them to be honest with themselves and not to build their lives on a lie.

I liked his idea that a man who hears a voice telling him to kill his wife and obeys that voice actually deceived himself. He caused himself to hear a voice because his marriage was unhappy and he didn’t like alimony. Of course he could just be lying to the court too; he never heard any voice, but wanted a lighter sentence.

Report comment

There are some rare cases of “religious zealots” who act like Joanna’s example. I have never met one personally–because they are RARE. Talking to a clergy member who would tell them how wrong this behavior is might help more than psychiatry.

Actually all of her examples are extremely rare. Maybe 1 out of 1000 get inducted into the “mental illness” hall of fame start out this way.

Most enter through one of two doors. They act very eccentrically–freak people out–and get “treated.” Others start out with real problems. Emotional problems, not organic. They seek out a shrink in desperation and receive “help” in the form of lies, neurotoxins, lies, imprisonment, and more lies.

The freakish extremes need help. But I wish Joanna Moncrieff and others would acknowledge that most do not fall into this category.

Report comment

They sure are. That’s why I suggested a trip to the neurologist instead of the shrink for her Man of God in an earlier post (a number of lines above this post), to get an idea of what you’re dealing with).

Report comment

Skimming this to the best of my ability as my eyes are blurring. Looks like Dragon Slayer has it pretty much nailed here from what I can see!

Report comment

Dear Slaying the dragon,

Although we clearly disagree profoundly on this issue, I appreciate your detailed criticism. I think our main point of disagreement is that I believe there is a social problem that needs some sort of response, which is not just created by psychiatry. I do not think it is a medical problem, and I am not trying to defend the current system. I use the term mental disorder because it is difficult to conjure up another term, but I have tried to make clear that I am referring to a variety of behaviours and experiences that do not necessarily have anything intrinsic in common, but which cause a set of social problems that institutions like the criminal justice system are not easily able to address. The whole point of this blog is to call for a collaborative effort to imagine a better system.

As I said to Frank above, I used to be a libertarian, but I have had so much experience of situations where people’s behaviour causes considerable distress, disturbance or danger to themselves and others that I have come to conclude, reluctantly, that some system of social control is necessary. Although you say I am offering extreme or absurd examples, I could have offered many more in a similar vein. In the first example, the man was actually taken to hospital on another occasion by members of his church, because they were so concerned about his strange and disruptive behaviour during a service. This is a good example of the point that Jeff Coulter makes, that madness or mental illness is defined by the community, not by psychiatrists. The psychiatric diagnosis or label is a technical-sounding, post hoc justification for action that has already been decided to be necessary by the local community and society in general. Of course psychiatric discourse feeds into what the community defines as unacceptable behaviour, and it has widened the range of this considerably, but as history suggests there have always been situations that ordinary people find dfficult, disturbing and perplexing and struggle to deal with. Psychiatry responds to deeper social and political needs, it does not create them, but that does not mean to say that it is the right or the best response to these needs.

You object to the concept of a ‘duty of care’ and I agree that paternalism is dangerous and problematic. At least in some circumstances, I think we should leave people who are only harming themselves to their own devices. However, I think there are some situations where actions appear to have been impulsive, or someone is in an altered and confused mental state where we should intervene to protect people’s own safety.

Report comment

As you know, there is a requirement to have an “action plan” in the UK and this was such a laugh – it was basically step 1, calm down and go home, step 2 call A&E or the police. If you call the nightline you just get that advice down the phone. It’s useless, you are well and truly on your own. Furthermore if you’ve been given a drug treatment that you are not totally happy with and could conceivably be part of the immediate problem, it feels doubly frustrating that there is no-one there when you need them (but they are all over you when you don’t). I think carers and family could be given a lot more advice about what to do, it saves them searching the internet in a panic, and why not a 24 hour social worker team who come out? Grizzled people that have experience and are just there without getting all officious and threatening.

Report comment

Joanna some people have very low IQs. Mentally they never age beyond say–age 8. Are you saying people disconnected with reality fall into this category?

Sadly I have to agree. But these people are much less common than everyone thinks. And–just like we would want to improve the cognitive abilities of an adult with developmental delays–we should strive to bring the “dreamer” back to reality. Pills are not the answer, since they will turn a brief stroll down La la Lane into a life long residency in the Twilight Zone. 70% recovery beats 0.

Report comment

Joanna, thank you for your reply. I’m sorry if my response to your article came across as too acrid. I respect your work and admire much of the research that you have done, and I believe that we can also learn from your experiences and opinions. If I forcefully reject your premises and conclusions it is because I know from both study and personal experience, too terrible to describe in words, the harm that psychiatry inflicts upon untold numbers of innocent people. In fact, I would agree with you that there are a lot of troubling things out there in this crazy world. Nevertheless, it is helpful to hone in on the basis of our disagreement because truth may come to light where the contrast is most salient. You say that there is a social problem. Very well. Let’s talk about this social problem. What is it? Unless we understand very clearly what the problem is, I will remain highly skeptical about any “solutions.” If I understand you correctly, you claim that “mental disorders” are at the root of this social problem, and you use the term “mental disorders” because that is the term that is commonly understood to constitute the root of this social problem, whatever it might be. As far as I can tell, you reject the notion that “mental disorders” are biologically based, but you insist that there is such a thing as a “mental disorder.” Unless I am wrong, it seems that you argue that psychiatry presents some sort of a solution to this social problem, whatever it might be, because the legal system or criminal justice system falls short. Am I understanding correctly?

For the record, as much as I admire Szasz’ work, I’m not a libertarian either. I understand the need for good government, and I am as opposed to anarchy as I am to psychiatry. As I’m sure that you know, and as Szasz often explained, the notion that an individual may be a danger to himself and others is very deeply rooted in psychiatric ideology. I’m sure that you could come up with many more extreme examples of distress that psychiatry allegedly resolves. So could I. But do you agree that such cases are the exceptions? In my mind it is crystal clear that the vast majority of victims of psychiatry are not only innocent and harmless, but that even the rare, bizarre cases that you mentioned are more often than not the result of some previous psychiatric intervention (Peter Breggin’s book “Medication Madness” comes to mind, as do the numerous violent rampages that were provoked to some degree by SSRIs).

What happened to the poor man who was taken to the hospital by his church members? Did psychiatry fix the problem? Whatever was going on with that poor soul, I can guarantee you that his situation is 1,000 times worse if he had any contact with psychiatry after that. What was his experience with psychiatry before that event? These are the kinds of things that the media refuses to report.

“This is a good example of the point that Jeff Coulter makes, that madness or mental illness is defined by the community, not by psychiatrists.” How would the community, whatever that might mean, have any idea of “mental illness” if it weren’t for psychiatry? Communities may stigmatize and ostracize people for behaviors, but psychiatry provides the supposed authority for the stigmatization and ostracism of such individuals. As Szasz often demonstrated, psychiatrists are like the new class of false priests to whom the laity turns for solutions. Psychiatry is a false religion that persecutes dissidents and heretics with more fervor than any inquisition.

“…but as history suggests there have always been situations that ordinary people find difficult, disturbing and perplexing and struggle to deal with.” What sort of history do you have in mind here? Only after the rise of psychiatry have we seen the outright medicalization of every day life. Have there always been problems? Of course. It’s called life. And what do you mean by ordinary people? Do you include psychiatrists within the rubric of ordinary? That alone would be an extraordinary claim.

“Psychiatry responds to deeper social and political needs, it does not create them, but that does not mean to say that it is the right or the best response to these needs.” Can you please provide some evidence for this assertion? What are these deeper social and political needs? How is it possible to claim that psychiatry does not create the problems when you admit that neurotoxic drugs often cause the harm that is interpreted as “mental illness”? How is it possible to claim that psychiatry does not create problems when the DSM-V has a fictitious diagnosis for almost every possible human behavior?

“However, I think there are some situations where actions appear to have been impulsive, or someone is in an altered and confused mental state where we should intervene to protect people’s own safety.” Is it not abundantly clear that neurotoxic drugs, psychiatric interventions, involuntary incarceration, torture, psychiatric abuse, and labeling impel many people to act in the ways that you describe? The recent Florida shooting is just one among many similar examples. On the rare occasion when a person acts in the disturbing ways that you describe without any previous contact with psychiatry, is it not abundantly clear that the same person will be 1,000 times more likely to exhibit even worse behavior after psychiatric interventions? Please help me to understand. If you believe that restraining, drugging, incarcerating, and labeling some odd-ball will do any good, either to him or to society, then I confess that I am baffled by your support for psychiatry.

Perhaps I agree with you that there is a social problem. As I see it, the social problem IS psychiatry itself. I’m not sure that psychiatrists should be arrested and incarcerated just yet, although someone needs to be held accountable for psychiatric crimes. The abolition of psychiatry will help everyone, not just victims of psychiatry. When psychiatry is abolished, psychiatrists will be freed from their supposed “duty of care,” and they will be liberated to pursue honorable employment. The abolition of psychiatry, like the abolition of slavery, may take some time. Nevertheless, society as a whole will benefit. The psychiatric slaves will be set free, and the psychiatric slave masters and wardens will be set free from their imagined duty to resolve what they perceive to be social problems.

Will there still be problems in the world after psychiatry is abolished? Naturally. But at least people will be free to resolve their problems without fear of oppression and coercion by psychiatric overlords.

Report comment

Hi Slaying the dragon,

I appreciate that you are willing to engage with my arguments! Yes I think there are social problems that are associated with what we currently call mental disorder, but that does not mean I think that mental disorder is a term that denotes a consistent set of problems or an abstract thing of some sort.

Mental disorder it seems to me is a broad umbrella term (and not a unsatisfactory one, but there is no good alternative), and I have been talking mainly about situations we might previously have called madness that are characterised by behaviour and speech that is bizarre, irrational, unpredictable and sometimes associated with disturbance to, or dependence on, other people, as illustrated in my examples. There may be many people who are quietly mad, yet get on with their everyday lives, I am not aure we will ever know how many, but the people who come to the attention of ‘services’ present problems of one sort or another.

I completely agree with you that psychiatrists have sucked in many other sorts of life problems by presenting the enticing idea that they are diseases that can be easily fixed. My experience is that many people like this idea and are quite resistant to having their problems presented in a different way, but of course this follows years of mental health ‘education’ campaigns.