“If harm happens, and no one’s there to say sorry, did it truly wound?”

The Power of Love vs. The Love of Power

‘Love Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry.’ It’s a catchphrase first popularized by Erich Segal’s novel Love Story back in the 1970s. And it’s wrong. Completely, totally wrong. It is almost as far from an act of love as one can get to refuse accountability; to not have enough respect for someone else to muster acknowledgement for your own missteps or how you’ve contributed to someone else’s pain. That doesn’t mean it is not incredibly human to struggle and sometimes fall way short, but that doesn’t make it an act of love all the same.

It is, however, power. Indeed, never having to say you’re sorry probably means one of two things:

-

- You have a ton of power over someone(s) else: You’ve got nothing to lose, because they don’t have enough power or credibility to take away anything that you value. Especially if you stick to the system’s version of the golden rule: Deny, deny, deny.

- Someone(s) else has a ton of power over you: They’ve decided you are — for some reason — incapable of being responsible for your own words or actions. Whatever you did that might lead to an ask for apology in most situations isn’t actually seen as your fault. Or, perhaps more accurately, it’s still seen as your ‘fault,’ but nonetheless on them to just control you a little better.

There’s also some fear in there somewhere: Namely, fear of loss of power. What underlies that is probably several other fears… fear of being blamed; fear of being alone; fear of not being important or needed anymore.

The Systemic Sidestep

But, this never saying sorry isn’t just a practice that is internally driven. It’s systemic, too, and often heavily influenced by capitalism and other oppressive forces. As cogs in various systems, we are taught that saying sorry increases our ever-feared liability, that it puts our ability to earn our livelihoods at risk. That it potentially invalidates our educational systems, too. And we are taught all sorts of contortion-level strategies to evade actually saying those words, while still trying to trick people into thinking they’ve been said.

-

- “I am sorry if that hurt your feelings.” (Did you catch that sneaky if? I just slid that in there to let you know that I’ve ignored every time you’ve definitively told me that your feelings are hurt, or at least, I’m preserving a bit of room for doubt. It gives me space to breathe.)

- “I am sorry that you feel that way.” (Hey, I’m not saying that I’m sorry about anything I actually did. Just sorry that you feel a certain way about it. I mean, that still makes it kind of your fault, right?)

- “I am sorry, but I think you might be overreacting.” (You can pretty much just ignore the ‘I am sorry’ part here. I may have said it out loud, but it’s more like the silent ‘K’ at the start of the figurative ‘knife’ with which I’m about to jab you. It’s really just there as a lead-in to my letting you know this is still somehow about your own personal failing.)

- “I am sorry, I was just trying to help.” (I mean, you can’t hold me responsible for good intentions, can you? That’d just be mean, and you don’t want to be mean… do you?)

- “I regret that we didn’t take time to pause and talk it through beforehand.” (What I’m really trying to say here is that, while I feel okay about where we landed, I wish we’d put on a better show of going through a process to get there.)

- “I know that we could have done better.” (To be clear, I am not saying what we did was bad. But, we can always do better!)

- “We will consider doing things differently in the future.” (We’ll surely consider your recommendations for five hot seconds at the very next opportunity and right before we basically do the same damn thing we did last time.)

On occasion (though a significantly rarer breed when it comes to people in positions of power), there’s also the over-apologizer.

-

- “I am so sorry. I am so terrible! I really suck.” (My goal here is to make you feel so uncomfortable for naming a problem that you are compelled to shift all your energy into making me feel better. And, if I do it just right, I may score the added bonus of you avoiding trying to hold me accountable for anything ever again! Maybe I can muster a few tears… Just give me a second! P.S. I don’t actually think I did anything wrong!)

Most of the time, these sidesteppers fool no one. When these pseudo-apologies do work, the effect is usually only temporary, as the realization of the illusion of sorry-not-sorry sets in. Perhaps what’s strangest about the whole thing is that it’s so unnecessary. So counterproductive. This conceptualization of power as a thing one either owns or gives up is almost childlike in how it’s been concretized. As one of my favorite social media memes says, “Equal rights (or power, as is the case here) for others does not mean fewer rights (or less power) for you. It’s not pie.”

Most of the time, these sidesteppers fool no one. When these pseudo-apologies do work, the effect is usually only temporary, as the realization of the illusion of sorry-not-sorry sets in. Perhaps what’s strangest about the whole thing is that it’s so unnecessary. So counterproductive. This conceptualization of power as a thing one either owns or gives up is almost childlike in how it’s been concretized. As one of my favorite social media memes says, “Equal rights (or power, as is the case here) for others does not mean fewer rights (or less power) for you. It’s not pie.”

A Trivial Example of Sorry-Not-Sorry

A trivial example of how wedded people in power can get to the sorry-not-sorry approach follows here:

In the last two years, I have seen a lot of movies. A lot. I even went and saw ‘Cats’ expressly to revel in its badness. (Well, okay, and because I wanted to see the dancing-cockroaches-with-human-faces scene in all its Kafkaesque glory.) But about six months ago, my favorite theater decided to “renovate.” Unfortunately, “renovate” translated roughly to reduce food options, increase wait times, hire more employees trained in the art of the blank stare, and, oh yes, add a bar (because prioritizing the addition of alcohol in an environment where silence is key makes perfect sense).

Being who I am, I complained to every employee with whom I intersected, especially as the problems accumulated. And, in doing so, I noticed an unsurprising trend. The higher up in the cinema’s hierarchy someone sat, the more likely they were to pretend nothing was actually wrong. Entry-level managers would nod knowingly, state their agreement outright, or give me insider information about how the renovations had left them with too few grills for hot food. On the other hand, the senior manager on site denied every complaint, or offered some excuse. The end result? I got more upset.

At some point I said to him, “Hey, you know, all your other managers with whom I’ve spoken have actually acknowledged the problem. I hear that you may not be able to fix the problem, but please stop telling me it doesn’t exist.” He made eye contact with me, wearing a bit of a defeated expression (or maybe I just wanted him to look defeated), and said, “Look, things aren’t going to change. This was decided at the corporate level. We’re doing the best we can with it. I’m sorry.”

And then he began shrieking like the Wicked Witch of the West and shriveled away until nothing but a small puddle and his plastic manager’s badge was left on the ground. Or… he was just fine, and I actually felt heard, calmed down, and moved on with life. At least until I got an e-mail from his boss in which she wrote:

“I am sorry if members of our management team have given you the impression that [our theater] has made a mistake with our remodel … The team will be looking forward with a positive attitude and helping find ways to improve guest service within our current concept.”

And around we go. Not only did she not offer any real “sorry” herself, but she tried to take back everyone else’s “sorry,” too. Nice. And that brings me to the not so trivial examples.

THE NOT-SO-TRIVIAL EXAMPLES OF ‘SORRY-NOT-SORRY’

This ‘don’t have to say you’re sorry’ trend if you hold power is everywhere, but there are few places where its more prevalent than when ‘less power’ means ‘psychiactrically diagnosed.’ For the last few years, my colleague Sean Donovan and I have been engaged in making a film with the working title “Three Rooms” through the Western Massachusetts Recovery Learning Community or ‘RLC.’ (Other of our co-workers are also in the film, including Caroline Mazel-Carlton and Cindy Marty Hadge, along with a host of others from Massachusetts and Connecticut.) It is a “video bridge” concept originally inspired by ‘Unexpected,’ a Canadian piece about young mothers living without homes and the healthcare professionals who deliver their babies. The basic idea is that groups of people who intersect with one another in a particular way and who hold very different levels of power are filmed separately. During those sessions, they talk about their own experiences, and their perceptions of members of the other group(s). Clips of their video are then shown to the other group(s), and reactions and responses are captured on film, as well. Another example of this style of filmmaking is ‘Why we Drop Out’ by Ali Pinschmidt, with the groups being made up of former students, teachers, and school administrators.

In ‘Three Rooms,’ the groups are as follows:

- People who’ve been hospitalized and/or lived in group homes (by force or choice or — most often — a mix of both);

- People working in provider systems (in direct support and/or leadership roles); and

- Senior administrators and funders (State Department of Mental Health Area and Medical Directors, hospital CEOs, an administrator from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

Unlike the other ‘video bridge’ films noted, we organized the process so there would be multiple (at least three) video bridge rounds with each group. Frankly, it has been a logistical nightmare to make, and as a largely unfunded project, it’s also been challenging to finish. However, some really interesting themes have emerged. I’m going to leave most of the ‘Three Rooms’ talk for another time, but I bring it up at all because the “sorry” issue showed up in the very first round. It went something like this:

Group 1: They never say they’re sorry for how they’ve hurt us.

Group 2: They’re right, and now we want to say we’re sorry.

Group 3: What the hell does group 2 think they’re doing saying “sorry”?!

Indeed, the most fascinating thing of all was that no one really cared what Group 1 said or did. They didn’t seem to balk at the mention of reparations as raised by cast member Dorothy Dundas in the clip above (which, in theory, should be the scarier of the two asks in her conversation with fellow cast member, Corrine ‘Mitzy Sky’ Taylor). But those with the most power sure were put off by that middle group… You know, the ones who don’t hold the most power, but are apparently charged with the responsibility of acting as the face of it nonetheless?

But, again, what was Group 3 so afraid of? Was it just too uncomfortable to sit with the idea that they’d been in the lead of a service that had caused harm to those they saw themselves as charged with helping? Honestly, part of the hope of the project was to illuminate the fact that no one — not even those in Group 3 — were actually in full control, but that goal seemed further out of reach than we thought. And, most of the people in Group 1 (with an exception or two) weren’t even people who’d been in the facilities run or overseen by people in Group 3, anyway. So, it couldn’t be as simple as pure liability concerns. Was this a savior complex issue? Had they simply spent so much time convincing themselves that their job was to “put on a good face” and do their right best to save the poor sick people? Was the cognitive dissonance just too great? Perhaps, not completely dissimilarly from a “trauma response” (though also not quite the same), they felt their personal construct of the world was under attack and a version of “fight or flight” kicked in. (In fact, one member of Group 3 had to be talked out of walking out midway through the first round, and two of them dropped out before the second meeting.)

When Sorry And Suicide Prevention Intersect (or don’t, as the case may be)

Unfortunately, this ‘never say you’re sorry’ trend isn’t just a problem of casual conversation or accusations thrown in the heat of the moment. It’s at least as present during formal complaint processes as any other time. For example, in the Spring of 2019, I filed a formal complaint through my work with the Western Mass RLC against a chapter of our state’s Suicide Prevention Coalition. Now, this is the same coalition where we got the inspiration for the Alternatives to Suicide approach over a decade ago, and where we developed our initial and still-valued relationship with Tapestry Health — a harm reduction-oriented public health organization that would soon thereafter become the first funder of our Alternatives to Suicide groups.

Although there were always differing perspectives on the committee, there were also plenty of good people, and we’d navigated any disagreements relatively well over the years. Until there was a change in leadership, and a provider took over who at least showed all the signs and symptoms of one who is suffering from “Clinician Sensitivity Disorder” (CSF).* I forget where I first saw mention of something along the lines of CSF, so I’m unclear who to credit, but I’m certainly not its originator.

Although not to be compared, it is reminiscent of ‘white fragility.’ In other words, with pretty much every type of systemic oppression, there is a common component that leads those in the power-up position to commonly feel threatened and respond reactively when anyone raises issues that suggest that those in power may have hurt them, or tries to talk about privilege and power pretty much at all. This is where the “not all (white people/men/straight people/providers/insert pretty much any other group of people seen as holding power and privilege)” phenomenon was born, because when generalizations are made about those in power it’s received as an attack, but when generalizations (aka stereotypes) are made about all people in a marginalized group… well, that’s just how it works.

Now, under this new leadership, the coalition with whom we’d once worked well refused repeated requests to afford membership to a minimum of two people who could speak openly from the perspective of having been suicidal or made suicide attempts. (Note: Up to this point and for nearly a decade prior, we’d been able to send two and sometimes even three people to participate without issue.) That was, they refused unless one of them agreed to essentially be the silent-support-peer (as in not allowed to speak at all) of the other “out” person… kind of akin to an emotional support animal accommodation. Members of the committee also refused to wrap their heads around the idea that promising that there were other people on the committee who secretly had also struggled in the past was not sufficient to avoid tokenization, silencing, or being outnumbered by those who at least outwardly only identified as coming from primarily the perspective of having formal credentials and/or a professional provider role.

At one point, the committee did spend time talking about allotting stipends for more people who’d experienced suicidal thoughts to be able to attend (particularly those without jobs to support them to be present), but followed that up by inviting a police officer instead. The police officer arrived in full uniform — including a firearm — and when my co-worker pointed out how the uniformed officer’s presence (especially with gun) could feel frightening to people who’d, say, been forced into hospital by police in the past, he was silenced. Specifically, he wasn’t denying the relevance of inviting a police officer (suicide rates are indeed high among their community, too), but was citing the disconnect between an expressed want to invite more people with firsthand experience of wanting to die versus the prioritization of inviting someone who holds a role and created a visual that might serve to keep them further away. (The police officer was the only one who apologized.)

Perhaps most amusingly, after several such points of tension, this same co-worker attempted to communicate his level of frustration and hopelessness about the coalition by somewhat facetiously (but also somewhat not) stating that taking part in the meetings was increasing his desire to die. And that Suicide Coalition… Well, they couldn’t handle it. That’s right, folks. My co-worker — a person who has himself struggled with suicidal thoughts for many years and lost people he’s known and loved to suicide, too — was unable to talk openly about suicide to the Suicide Prevention Coalition because it “triggered” them too much. (And therein lies a major root problem with the Suicide Prevention industry all around — this “let’s talk about suicide without actually talking about suicide ‘cause we’re too fragile for that” way of being — but that’s a story for another time.)

The committee also justified spending well over their self-proclaimed limit (that had been used to deny us adequate compensation for the trainings we were committed to offer ourselves) to bring an individual (with whom the leadership happened to be co-authoring a book) across the country to do a “mental illness” comedy routine. Further, while the comedy routine shtick did make space for a panel of people speaking from their own experience with suicidal thoughts, some of them were quite explicitly instructed to self-censor and not say anything negative about the system when discussing their own experience. Meanwhile, minutes of multiple coalition meetings (when there were minutes produced at all) inappropriately included pejorative statements only ever about the people on the committee who had psychiatric diagnoses, while non-diagnosed members were allowed to behave in an array of problematic ways including making transphobic remarks without consequence or notation. And this is just scratching the surface of what was contained in the detailed complaint (with exhibits) that was submitted.

Not surprisingly, the complaint was not decided in our favor, and when we appealed this was the response we got back:

The Executive Committee has fully reviewed both your complaint (including the email you sent following our findings that you requested be included as part of the complaint) and the findings of the subcommittee in response to your complaint. We have discussed the matter thoroughly as a committee, addressing each allegation and the corresponding findings and unanimously voted to uphold those findings.

As I stated in my previous email, this is the last appeal process, and the decision of the Executive Committee is final. We have spent a considerable amount of time investigating and thoroughly considering the allegations from your complaint and we are confident in upholding the findings that came from that investigation.

Now, this complaint — from start to finish — took about six months to process. During that time, e-mails were inappropriately shared with the primary subject of the complaint without warning, and we were given no clear information about the process or timelines. We filed the appeal to the original decision on August 9, and were told on August 27 that they were “unable to give [us] an exact timeline, as September is World Suicide Prevention Month and [their Executive Committee] members are quite over-scheduled at that time.” No outside arbiters were offered or available.

Most importantly, no apology was ever given. No one said “I’m sorry.” It seemed completely unfathomable to them that they might say something like, “Even though we are unable to formally substantiate these claims, we’re really sorry that you were written about in the minutes of a meeting. That shouldn’t have happened.” Or… something. Instead, communication was kept to a minimum, phone calls were refused, and e-mails received were cold and matter-of-fact. How strange that people purportedly so invested in “helping” professions would respond with withdrawal and denial when people are saying they were hurt. How odd that people dedicating their time to “suicide prevention” would be so ignorant as to how power plays in their own gatherings, when they must be at least somewhat aware of the impact of loss of control and power on suicide rates overall.

Sorry-Not-Sorry Cuts Deep

And, let’s be clear. The impact of this severe ‘sorry’ drought runs deep, and far beyond mere annoyance and inconvenience. When one refuses to accept accountability, it can have several dire consequences that include (but certainly aren’t limited to):

-

- Making someone feel (often more) invisible

- Replicating past traumas suggesting wrongdoing was somehow the fault of the person who got hurt (“You made me do it,” “You confused me,” or “You know you wanted it” are all fairly common phrases that people who’ve experienced childhood sexual abuse have heard.)

- Denying someone’s reality and experiences (including those whose psychiatric diagnoses also render them “untrustworthy” and “lacking credibility” in the eyes of the world)

So, in summary, we’re talking about a system where people are constantly getting stuck and dying early; where a huge percentage of individuals have experienced trauma that has played at least some role in their emotional distress; and where feelings of invisibility, loss of control, and powerlessness are known to significantly increase rates of suicide and foster dependence and hopelessness. As a strategy to combat some pieces of that (or at least not make it worse), we’re suggesting something that is totally free, not time intensive, and requires little to no physical effort. And yet, it still seems to be too much.

I wish I could say that there was a clear path forward here, but I don’t know what that is. The absence of ‘sorry’ is epidemic. The fear that drives it is so detrimental that it deserves a diagnosis and subsequent ‘treatment’ all its own. And as luck would have it, I’m prepared to provide a diagnosis: Formido Apologia Disorder* (FAD for short). It translates quite literally to ‘fear of apology’ disorder. (To be clear, it’s disorder and not disease because — just like pretty much every other diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — it’s not actually been proven to be a thing caused by a lesion or other tangible disease process of the brain.) The recommended treatment? Just. Say. You. Are. Sorry. Consider it exposure therapy. I mean, it’s supposedly “evidenced based practice,” and that’s all the rage these days, right?

much every other diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — it’s not actually been proven to be a thing caused by a lesion or other tangible disease process of the brain.) The recommended treatment? Just. Say. You. Are. Sorry. Consider it exposure therapy. I mean, it’s supposedly “evidenced based practice,” and that’s all the rage these days, right?

The Promise of a Sorry Tomorrow

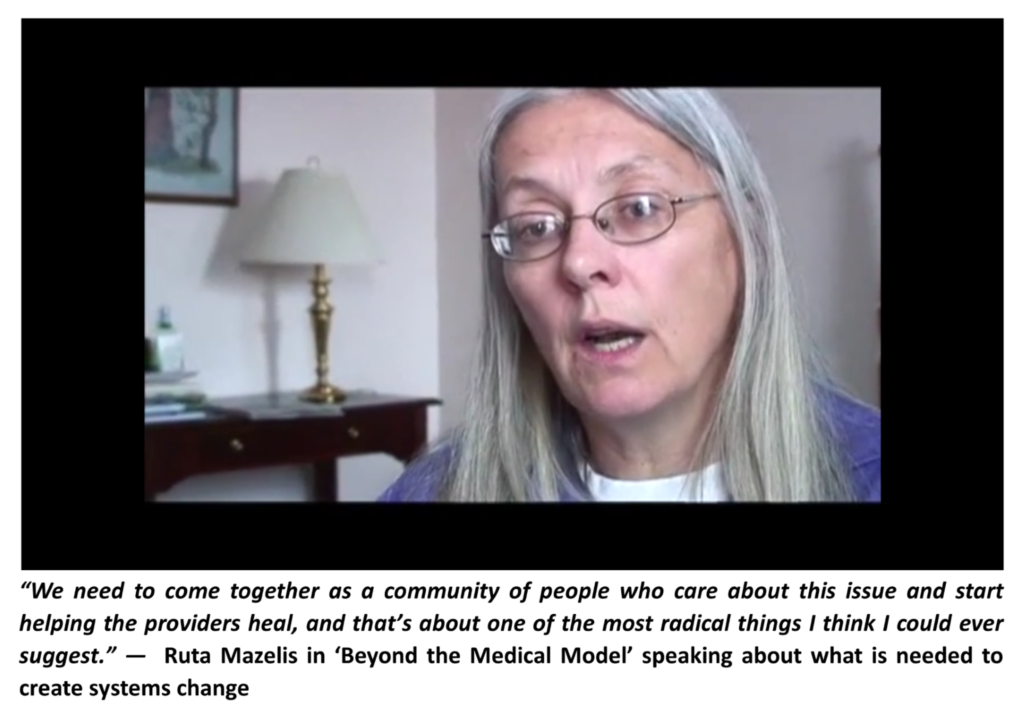

I wonder how this system would be changed if, tomorrow, every provider (past and present) woke up and made it their mission to find someone who’s been through their services in one way or another, and told them they were genuinely sorry for something specific that had happened during that time. One 2017 article, “The Power of an Apology,” states, “Saying ‘sorry’ denotes that you have chosen your relationship over your ego.” What is needed to make it possible for more people to do that?

Hell, what if every provider said sorry for not saying sorry? What if organizations like the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI), instead of business as usual, ran an initiative to get providers to simply say they were sorry, and grieve the harms they’d caused? (Hey, NAMI, I promise to not write another NAMI article for all of 2020 — not even about that creepy Santa video — if you’ll just put your heart into that!)

I wonder what a “say you’re sorry” campaign might actually accomplish, and what opportunities it might open up. But, I’m not holding my breath.

Sorry.

* I speak to two diagnoses in this article: CSD and FAD. Please note that I do so in jest. While the diagnoses represent very real phenomena, I do not wish to perpetuate diagnosing people’s real and human feelings beyond a momentary poke at humor… No, not even when those real and human feelings lead them to do problematic things.

Oh my gosh Sera,

Wonderful article, and how I love your “video bridge” project.

You are out there taking on the world, speaking out.

Your voice is strong.

You are so right about the misuse or un used word “sorry”

Power packs away that word in it’s sorry suitcase and takes it out

for their own purposes, who knows where.

There are so many ways that the word is also misused, as a power trip

Because if someone hears an important person say, “sorry”, and if it is not accepted

by the offended, others often demean the offended by saying, “look he apologized”

Which makes the offended even more upset.

There are times when an explanation is needed behind “sorry”.

And we HATE to squeeze an apology out of someone. If it is like pulling teeth, it is not an apology.

Report comment

Thanks, Sam Plover! Yes, there’s so much else that could have been said here… So many off shoots, including how power also equals credibility (and how power calls upon others in power to protect one another), and how even (especially) a genuine ‘sorry’ knows that forgiveness isn’t required, and so on. Thanks for raising some of that here!

-Sera

Report comment

Neuroleptics, lepto – is like something that you can change and something that you have to pay, so i have to change my nerves in order to pay for something valuable, seeds for example..but what does neuroleptics do? They help don’t lose control. So if someone deals with power – it’s useful to have them at hand.

Report comment

Hey Manyshev, Thanks for your comment! I’m not sure I totally follow, though… Do you mean neuroleptics help people contend with/stay calm when facing people in power? I suppose neuroleptics have different impacts on different people, but of course, I worry that for a lot of people (not all, but a lot!) the ‘help’ to not lose control actually comes in numbness and sedation rather than improved ability to navigate the world.

On the other hand, I definitely see (and maybe you mean?) the system use neuroleptics to aid in *their* not losing control/maintaining power. I definitely, for example, have seen a change made to someone’s neuroleptic drugs to quiet them down when they want to make a complaint against a hospital. (It was very effective.)

-Sera

Report comment

Thank you for the blog! So many great points made!

I wanted to dovetail off this and talk about situations where people abusing you don’t apologize, yet the abused person is expected to apologize for things they don’t need to apologize for such as being in a marginalized position. Also, generally speaking there are many other things in life that people want to shame you over that you don’t have to apologize for. They may get a sense of power and control from guilting and shaming you, and if they feel embarrassed about their conduct, instead of owning their feelings of guilt and shame, through cognitive dissonance they instead continue their abusive behavior, using whatever justifications they can find. You can tell someone who you are until you are blue in the face, but if they want to mistreat you because it benefits them, whether that benefit is being able to hold on to their bigoted beliefs because it is entrenched in their identity or ego, deal with their insecurity, maintain power or status, not be associated with people they view as less than due to internalized oppression, tribalism etc., they will. When a person dehumanizes you in their own mind, there is no limit to what they feel entitled to do to you.

Sometimes people just want to justify their bad behavior. If I have learned one thing in life, it is that the rug can be pulled out from me at anytime, and if my approach is “wrong”, instead of clinging to ego and identity, I will reinvent myself, including if I need to reinvent myself completely. I am not going to get trapped in sunken cost fallacies or anything like that. I have reinvented myself before as I have learned and grown and I am not going to be trapped by my old beliefs, behaviors or patterns. Period. I apply this to myself now, and view life as a continuous process of learning and growing.

I am in a situation where I am being “mental health” shamed and the power differential between the individuals oppressing me and myself is HUGE. The situation itself gives them an unbelievable amount of power over me and I don’t think they even realize it. The people doing it feel justified in their behavior due to fear and hatred and are basically telling me I need to apologize for something that I have no control over (their perceived MH label) through their abuse. For the record, I have been nothing but kind to these people. Of course their behavior isn’t excusable in any context. It is blatant discrimination, but the behavior is instead minimized. I want to go into more detail, but I am scared of them, and so I am trying to protect myself and my anonymity.

Since I can’t really escape this abusive situation at this time, I have some coping mechanisms that work for me. I try to rise above it. I treat them with love, kindness, and set healthy boundaries where possible. I feel empowered approaching the situation in this way. I am assertive when I can be and hope that maybe some day this could plant the seeds for them to look inside themselves and treat people better. My approach may not work for everyone but it works for me. No “right” or “wrong” there.

An unfair criticism I have received is that I should “fight back” harder. This is victim blaming as I have little to no power here. Plus, this is how I personally “fight” back and it works for me. I have also been accused of being “passive”. I believe there is strength in treating people with love and kindness, and approaching situations with positivity and optimism. That is not the same as being passive. It is also a little bit sexist to assume that love, kindness, positivity and optimism are signs of weakness, and ableist to assume that people are “dumb” who find empowerment there. People associate these traits with “femininity” which is (wrongfully) associated with weakness. I am basically being told I should apologize for my approach.

I have suffered a lot of adversity in my life, and I feel really empowered to spread as much love, kindness and compassion when I can-lessen the collective suffering, including that of my oppressors. I feel compassion for them despite all of this. Of course I am not “perfect” at it, but I work at it everyday for ME. I am proud of myself for conducting myself in this manner despite the adversity I have faced throughout my life and now. It’s not easy. It makes me feel strong. I am grateful that I am not behaving in a hateful way– the way they are to me. Hate is contagious but so is love. Again, this is my PERSONAL approach-not saying other approaches are “good, bad, right or wrong”.

Thanks again for the blog!

Report comment

Right you are anonymous17

“You can tell someone who you are until you are blue in the face, but if they want to mistreat you because it benefits them,”

The power imbalance. Try explaining to others that their belief about yourself is not the correct belief and that their belief really holds no importance except to themselves and those they have convinced those beliefs to be true.

Prevailing beliefs are nothing more, than what those around you cling to.

I suffered a lot of discontent to try and convince others that their beliefs would be okay if they were not intended to override another person’s experiences.

Report comment

Hi Sam,

Thank you for the response! Wow this is exactly what I needed to hear. I really appreciate the support! I am going to write a response tomorrow so that I can put a little more time into it.

Report comment

Hi Sam,

Yes! It takes an enormous amount of courage to stand up for who you are when it feels like the entire world wants to tell you who you are or is against you. Talk about a power imbalance. I am glad that you are able to stay true to who you are and speak up for yourself. As far as I’m concerned, we are all victims of these prevailing beliefs and extracting yourself from those clutches is a feat to be proud of. I have to work at the deprogramming daily and I am still hurting big time. The most cathartic thing for me lately in recovering from psychiatric oppression and all these other harmful structures (white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism etc.) which we are all assaulted by daily is to basically do or think, somehow simulate the exact opposite whenever and wherever I can. For instance trust my feelings; not label the harmless as harmful; be gentle with myself when everyone and their mom wants to hate me, define me, or is afraid of me; be accountable when I legitimately screw up; limit consumption; educate myself; self care whenever possible, all the things. Have a great evening and thank you for your bravery!

Report comment

Thanks, Anonymous17! You raise many important points here… there’s a couple that jump out most to me including how some people who are in traumatic, abusive, etc. situations are taught that they need to feel guilty/apologize for everything themselves… It’s a complete mind fuck! And some learn it from such a young age or such an abusive situation that they can’t see what’s happening… Others can see it but feel no choice but to go along with it (no matter how much it tears them apart)… and still others see it for what it is, refuse, and pay a price…and so on.

The second is how much people in activist roles or who are inspired by ‘the fight’ can lose sight of how hard and dangerous the fight can be for people in certain situations, and how one of the most insidious aspects of the system is how it rewards people for silence and punishes them for speaking up… And that can truly be dangerous for someone in so many different ways (psych drug changes, force orders, physical abuse, isolation, threats of loss of basic needs being met, and so on!)… And that just can’t be seen as the fault of the person who is just trying to survive in awful, unfair, and unjust conditions.

It sounds like you’ve been treated unfairly from many directions. Thank you for still showing up here, and taking time to share. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Yes Sera,

It is so easy too, for vulnerable people to accept shame and blame, and in defense to not let it destroy themselves, actually can get frustrated, angry and bitter and lash out.

When one goes to a shrink, we are often there because the thing that bothers us is laced with a shame, a feeling of being faulty, and a shame of even being weak enough, confused enough to seek ‘help’. Basically, that is a shrink’s job, is to agree that one is indeed faulty.

It is all so very twisted…

I feel psychiatry needs to go into a sincere attempt at reconciliation, not a mere sorry. Their damage is so pervasive, since it taints even those who will never enter the doors of psychiatry and NOT because of being well adjusted.

When people are escapees from cults, they often need help debriefing, because the beliefs that the cult helped you adopt are harmful.

There is absolutely nothing helpful or healing about adopting beliefs of being faulty.

….to step into a shrinks office can be seen as being sorry as to who one is.

Report comment

Hi Sera,

Thanks for taking the time to write back! I recognize too that part of my privilege is being able to recognize abuse in the first place and take steps to empower myself. Empathizing with my oppressors isn’t the same as condoning their behavior. I wouldn’t consider my approach a blueprint to deal with oppressive situations nor am I expecting marginalized people to forigive or even hold a shred of empathy for their oppressors. My situation is super nuanced and there are many ways it could be dealt with. This is my approach. I mean if I or anyone else were to scream and cry right there, get reactive, get angry or anything I still feel like the apology should really be coming from the oppressor, not so much the oppressed person who has been forced into an impossible situation. Also there is a very righteous anger you know? It again goes back to the power dynamics and overall harmful power structures in place which hurt everyone, but more so those who are marginalized. I also forgive myself for the times where I was not equipped to deal with the impossible as there have been times when I just couldn’t handle it. I am accountable when I’ve made mistakes of course, and I practice self forgiveness.

I know my writing is a bit sloppy and rushed but I wanted to make sure I clarified that in my previous comment I am not referring to a conversation I had with an activist or anyone in the survivor community regarding my approach to this situation. I want to go into more detail but do not feel safe doing so publicly.

Thanks again and have a great evening!

Report comment

I totally agree, there is a definite lack of saying “I’m sorry,” by the “mental health” workers, and their co-“conspirators.” Especially since the “mental health” industry’s paradigm of “care” has been pointed out as complete scientific fraud, and their drugs have been confessed to be torture tools.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

https://www.narpa.org/reference/un-forced-psychiatric-treatment-is-torture

“What if organizations like the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI), instead of business as usual, ran an initiative to get providers to simply say they were sorry, and grieve the harms they’d caused?” I agree, this would likely be beneficial for the “mental health” workers’ own “mental health.” Since they have systemically been harming millions, which they are now supposedly claiming they did unknowingly.

Despite this actually being a lie, since all doctors – including the psychiatrists – are taught in med school that both the antidepressants and antipsychotics/neuroleptics can create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But there is wisdom in the real Bible, that points out the importance of repentance, and changing from one’s evil ways, in order to receive forgiveness.

Thus, I do think a “’say you’re sorry’ campaign” may have value. Especially if it’s done with the reminder that changing from one’s evil ways, is needed for forgiveness.

I know I’ve got a non-clinical Lutheran psychologist, who is pissed as sh-t at me right now. Because I didn’t fall for his lies, and hand over control of all profits from my work, and all my family’s money to him, via a BS “art manager” contract.

The religions, and their DSM deluded “mental health” minion, really could benefit from learning to say they’re sorry, and changing from their evil ways. Since this is what Jesus said is required for forgiveness.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

https://books.google.com/books?id=xI01AlxH1uAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

And the systemic, child abuse covering up DSM “bible” believers, have given the Lutherans, “delusions of grandeur” that “repentance is a work, thus irrelevant to reality.”

I don’t agree. That’s not what the real Bible says. The real Bible says, “But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and [that] he were drowned in the depth of the sea.”

I agree, an “‘I’m sorry’ campaign,” with a reminder of the importance of changing one’s evil ways, could be beneficial for the scientific fraud based “mental health” workers, and the “delusions of grandeur filled” religions that employ these systemic child abuse covering up “mental health” workers.

Report comment

Thanks, Someone Else! Ultimately, of course, I don’t know what an ‘I’m sorry’ campaign would actually do, especially in the absence of change… But I do think it is relevant to change, personally. On a number of levels. I’d be so curious to see it play out… I hadn’t really made the connections to religious texts that you have here, though, so thanks for that.

-Sera

Report comment

I’ll know the apologies are real if they follow through and change their behaviors. Like anyone’s apology.

But–like my abusive ex–I still won’t go back to the relationship. Nope. Good luck, becoming a better person without me Dr. Quackenbush.

Report comment

About the Love Story reference:

Heyall,

I was reminded by a reader that in Love Story itself there is a deeper meaning to ‘Love Means Never Having to Say Sorry’ that is more about having no regrets than what I write about here. I acknowledge that the story itself had a deeper way of looking at this phrase and that there is truth to that meaning that resonates with many. However, this is a phrase that has lived louder and longer than the meaning from the story, and is nonetheless problematic at least for its superficial appearance and how it’s been used since that time… And perhaps most importantly, what it meant in ‘Love Story,’ just isn’t what this article is about, so hopefully you can look past that even if you are someone for whom the actual book or film was beloved.

Thanks!

Sera

Report comment

Love is primarily compassion. Without compassion, there is no love. Psychiatry belittles the meaning of human feelings – compassion, anger, resentment… Men-tally normal from the perspective of psychiatrists – as close as possible to an inanimate object. A certain idol, tuned to “correct behavior.”

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Lametamor. I agree (if I’m understanding you correctly!) that there’s a certain play with dehumanization and objectification that happens in this system!

-Sera

Report comment

I suspect “Compassionate Personality Disorder” will make it into the DSM-6.

Report comment

A lot of Aussies have what we call DILLIGAF (from the Kevin Bloody Wilson song) which stands for Do I Look Like I Give A ……. i’m sure you get the picture lol Maybe they could make the pills for treating Compassionate Personality Disorder a repackaged brain damaging tranquilliser and call them Dilligafs? All rights reserved by Mr Wilson.

Report comment

Great piece.

The UK psychiatric complaints system is set up so that they hardly ever have to say sorry. Even if they beat up and then “accidentally”kill your nearest and dearest (a case I know of). Or falsely accuse you of being a potential criminal and pervert and force you to leave your job and get sick things on your medical record that takes months of stressful time to get corrected (which happened to me several years ago). Never mind if eventually they agree that the drugs cause more harm than good or that ECT is dangerous nonsense – I’m not expecting any apologies there if those things ever happen.

I was reminded of running a theatre based consultation on Section 136 of the Mental Health Act (UK law which state the police can detain you and take you to a psyche hospital for assessment if they think you are acting nutty). We did it in the day centre and did a line out asking people how bad/good is psychiatry and the line went from mediocre to appalling. We did it again with social workers who did out of hours 136 assessments and the line went from mediocre to brill. Fortunately we had three service users there to take them to task.

We did another piece, a consultation for the Day Centre on proposed changes. We interviewed service users, put a play on that represented there concerns, booked an afternoon to put it on a run a discussion. The staff gave us a day and time that was the lunch outing for members. So we waited for them to come back from there outing. None of the staff were planning on coming and certainly not the area manager who asked and paid us to do the work. So we pulled the staff in from the offices. The normally reserved service users were quite outspoken about the proposed changes, we did our job well, the staff were a bit mortified. We wrote a report for the area manager on what service users wanted and were concerned about. They ignored every word.

The suicide prevention people remind me that nearly all social movements get co-opted by the powers that be. They choose compliant service users to go on committees and professionals who see there job as protecting those in power take over the top positions.

Never saying sorry means you are a heartless, well paid, middle class manager IMHO.

Report comment

Thanks, John! You remind me of the time when someone we were supporting who was incarcerated in a psych hospital got very hurt during a restraint, and when I asked the psychiatrist what he was going to do about the way this person was treated, he said he’d already done it… “changed his meds.” Ugh.

-Sera

Report comment

Well, what else did you expect him to do? It’s the only think he knows! Maybe he can give some drugs to the person doing the restraining?

Report comment

True enough, and still really awfully gross. On the other hand, the person who had his “meds” changed did indeed stop wanting to push a complaint, so I guess it was super “effective” in its way. Ugh.

-Sera

Report comment

Urgh, just urgh.

See, this just reminds me of why I really want a direct action anti-psychiatry movement and very occasionally invade wards and in December gave a psychiatrist a very hard time in a meeting.

Ugh, just ugh.

More strength to your work Sera.

Report comment

It all depends what “effect” you’re trying to accomplish, I guess.

Report comment

We had a situation here where a number of “patients”had their necks broken during restraints. I got the impression it was one of the thugs they call nurses who was practicing what he had been learning in Martial Arts classes. The report into these deaths is where I got my “unintended negative outcomes” from. The Chief Psychiatrist not wanting to give any hint of people being killed in his hospitals needs to call a spade a shovel. Noooo these priests weren’t raping children, it was a “character flaw”. The language is important, and like our recent discusiion regarding Euthanasia of our old folk clogging up our care facilities and winging about being abused, we can’t have our media calling it Euthanasia, call it Voluntary Assisted Dying. People like words like Voluntary. Ask any involuntary “patient” about what that actually means.

I did meet a guy who had asked his Doc to change his ‘medications’ but was denied, so he went to a local shooting complex, hired a pistol and put it in his mouth and pulled the trigger three times (it misfired the first two). He blew away half his jaw and finally got the doc to change his ‘medication’. I got the impression that the Doc was causing this guy some significant pain deliberately once I found out what he was being ‘treated’ for. But ya can’t prove it and thats how these guys are getting away with these human rights abuses. The “effect” you speak of Steve?

Mind you I don’t know that I accept the idea of these ‘powerful’ people who are unaccountable. See for example Fight Club. With our new Euthanasia Laws coming into effect, Doc might want to ensure they have no enemies if they ever require treatment for anything. Once rendered non compus mentis they may find their guardians volunterering them for a little more than they expected. Because we do have the power to ‘coerce’ folk now with mock executions and threats of pack rape.

My Government said “Sorry” to the Indigenous people of this land, and then continues to subject them to the most vile human rights abuses I’ve seen. The ‘test’ lies in what you do to correct your error. If your intent was not to harm then you correct yourself and attempt to make amends. If the word Sorry means nothing, you correct yourself and do nothing. Ive a really good example here from our Chief Psychiatrist, who acknowledges his “error” and then does nothing to correct it. Or so it would seem. Maybe it does take 30 years to stop child raping priests, or abusive organised criminals using their positions in the Mental Health system to torture maim and kill people by changing their status from “citizen” to “mental patient”. Imagine being able to call police and ask them to deliver people to your hospital for ‘treatment’ by simply lying and calling someone a “patient”? Got to be opprtunites to make some significant money doing a few knocks in the ED for criminals there?

“It never happened” I heard from a rather frightened psychologist whose family was being threatened by police. “Not in the public interest” I heard from a rather frightened lawyer who was prepared to take money from a nutjob, but ran when it turned out the nutjob was speaking the truth. “I thought you were mad, but you’ve got the proof” Yes thats right, I was tortured and kidnapped and when I complained they attempted to kill me in an ED. And let me tell you, they do not want to say Sorry. In fact the Operations Manager told me that if I kept complaining they would “fuking destroy me”. And as she was speaking as a represenatitive of my State???? I hope to obtain asylum from these vicious bastards at some point. And of course my State needs to be seen as doing the right thing now they’re crimes have been exposed. “Bad apple”, “isolated incident” except they went and took a peek and found ….. See the t”Targeted Review of Emergency Dept admissions” from the Office of the Chief Psychiatrist. Not a lot of unintentional negative outcomes but enough to have cause for concern.

Report comment

The first quote that came to my mind was from John Lennon: “Love means having to say you’re sorry every five minutes.”

Personally, though, I have little or no use for apologies either way, except a) in relatively rare circumstances where something I have done or said may have objectively harmed someone and b) if someone I truly care for and respect has said or done so to me.

If something I say and truly believe nevertheless and unwittingly triggers a negative emotional reaction I would say “I’m sorry your feelings were hurt,” which would not be “slithering out” of anything, simply being honest in the face of disagreement. To demand a “full apology” is a demand for the person to say “yes I was wrong and I hurt you,” not just an expectation that that person will be concerned about your feelings.

There’s a fine line between sensitivity and getting hung up in a blame game, which seems to come partially from ingrained Judeo-Christian concepts of guilt and confession. In general it’s not good to give people so much power over you that their opinions can ruin your day. In the context of politics or “official” settings it is largely immaterial in the end how someone in power feels about their behavior or whether they’re “sorry”; the issue is whether or not they have changed their behavior and/or addressed any demonstrable damage.

I sometimes will tell someone to stop apologizing so much, and they respond by apologizing for apologizing. At that point I give up and silently smile. 🙂

Report comment

I believe that apologizing is a nice thing to do after transgressing; it promotes a more civil society. However, our community is embattled so I agree with Oldhead that the issue lacks critical importance to me. I believe the slogan was: “I don’t care if The Man likes me; I just want his boot off my neck!”

Report comment

Then again there are the more casual usages of “sorry” as in, “sorry, the way I just phrased that sounded confusing,” which don’t really have anything to do with actual sorrow. But whatever. I’d just prefer that people finally “get” what I’m saying or feeling, rather than “apologize” to me for not having done so previously.

So many conversations on MIA seem to contain an admonition not to take something that has been said “personally.” Sort of like apologizing, when I think it should go without saying. Maybe when someone intends for something to be taken personally they should state it straight out; otherwise we can assume that we are simply engaged in intellectual discourse.

Report comment

Fair enough, Steve. And yet, many people find it quite relevant, myself included… And perhaps most importantly, I believe it’s shifts toward saying “I’m sorry” and so no that may help some folks realize what they’re a part of. The vast majority of people working in these systems are not people wanting to do harm or people who consciously seek out to just control and silence… They’re simply playing a role that they were taught to play, and perhaps if we could get back to some of these basic human ways of saying ‘i see you, and i see my impact on you, and i’m sorry for that,’ the rest would follow? Honestly, while I get that ‘sorry’ matters far less than actually stopping the harm, I’m pretty perplexed that people don’t think those two things are pretty intertwined.

-Sera

Report comment

I agree that the vast majority of people in the “mental health” care industry have good intentions. I also totally agree that the culture should become more civil to meet the needs of the community.

My problem is that I believe that the “mental health” care industry pathologizes social, economic and/or spiritual distress and denies basic human rights for suffering emotionally. As long as the industry believes that anxiety and depression are diseases rather than natural responses to distressing and depressing experiences, they could not possibly “see me.” As long as the industry cannot “see me”, they cannot possibly understand the impact that they are having on me and thus I would consider an apology not relevant.

I believe that if you want to understand someone, you must understand who they are arguing against. I am arguing against psychiatry for advocating the harmful Myth of “mental illness” that pathologizes natural “problems in living” and for their human rights abuses. Are you arguing against the general level of incivility in our culture, or how would you describe the community’s over-riding social problem related to “mental health” care?

Report comment

“I agree that the vast majority of people in the “mental health” care industry have good intentions….”

Good intentions under what beliefs? What discipline?

Sorry, the worst outcomes are laced with good intentions, unrecognized intention. Cleansing is NEVER a good intention

Report comment

Random “incivility” encountered in day to day life is different from systemic incivility encountered in the “mental health” industry. I guess it boils down to the fact that there is such an industry in the first place, which almost by definition engenders alienation and is more or less guaranteed to routinely offend human sensibilities. So in such a context the value of saying “sorry” for every systematized “microaggression” is nil when there is no intent of ever changing that system or the underlying assumptions.

Report comment

As Szazs pointed out they used to “bleed” cholera victims through the best of intentions.

Report comment

Oh, goodness, Oldhead. Sometimes I think you quite intentionally step sideways of the point of things. Not that what you say here doesn’t have lots of validity… It does, and you don’t need me to tell you that… but it’s also not really the point of this piece, which I think you know.

-Sera

Report comment

Just random thoughts, I don’t have a dog in this fight. Not that it’s necessarily a fight either.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

A great piece as always Sera! I thought the woman who tried to take back everyone else’s apology was pretty bad until I read how the fellow was “unable to talk openly about suicide to the Suicide Prevention Coalition because it “triggered” them too much.”

Wow, that takes the cake! How do you spell H.Y.P.O.C.R.I.S.Y. !

It’s appalling “people purportedly so invested in “helping” professions would respond with withdrawal and denial when people are saying they were hurt” (as per the standard operating mode for psychiatry)

And you put it well in that…. “The absence of ‘sorry’ is epidemic”.

And never saying sorry lets someone carry on with their image/façade of perfection or always being right. Ugh!!

As for “Love Means Never Having To Say You are Sorry”, my interpretation is if you follow the golden rule of “Do onto to others as you wish done onto you” you probably won’t need to apologize very often.

Thanks and Happy New Year Sera!

Report comment

“Do onto to others as you wish done onto you” you probably won’t need to apologize very often.”

So true. I guess psychiatry must only be doing what they wished done onto them, if they were in the same MI spot. But then, they are certain that they are not MI, after all, they passed the MI test that they designed.

If I design my own test and pass it, does that count as something credible?

Report comment

Thanks, Rosalee! Yeah, you know, I should be completely used to all the hypocrisy and injustice at this point… Like totally used to and numb to all of it at this point. And yet somehow the stuff like what happened with the Suicide Prevention Coalition absolutely pushes me over the edge at times. It’s far from the worst that happens in this system given the numbers of people incarcerated in psychiatric hospitals and how they’re being treated there on the regular… But it’s such a symbol to me of just how absurd it all is. Thanks for reading and commenting!

-Sera

Report comment

I for one am very glad that it still bothers you, Sera!

Report comment

After a decade of imprisonment from psychotropics, a response to a ‘lifetime’ bipolar diagnosis, I negotiated-lied-‘mirrored’-and implied (blackmailed) prosecution of an anaphlaxis ADR….shining a loud, messy legal light under their secret, sloppy rock….a trade for my cleansed body, soul, records…and freedom in writing. THIS was the ultimate psychiatric quid-pro-quo.

It worked; guided titration, withrawal AND a F49.1 UNPECIFIED ANXIETY sticker on my forehead as I ran out the door 2.5 years later.

ANXIETY? No shit. But certainly not UNSPECIFIED.

PAY ATTENTION….Bipolar is apparently ‘CURED’ by anaphylaxis!!

Alert the scientists & global media!!

They had discovered the cure!!..and now so modest.

They were eager to barter their absolute principles & ‘Bible’ without a second thought, to avoid cost & liability & exposure….on a 2nd-tier city’s community clinic level. What happened to their evidence-based science?

The APA ignored my email asking this question…suggesting…wait for it….’if I was in crisis, not to hesitate to call 911′. Oooof. Irony on that level is a gift.

Any acknowledgement or (gasp) apology suggested liability.

But it happened nonetheless.

Report comment

Ah, yes, it’s funny how the very best cures to psychiatric diagnosis seem to include a mix of insurance running out and no longer being willing to pay and liability risk. I’m reminded of Jim Gottstein’s ‘transformation triangle’ through which he argues that it is creation of alternatives + shifting public opinion + legal pressure (I forget what language he uses precisely) that will lead us to real change overall. I so wish more of us could have gone on to be lawyers! I feel like serious money ought to be invested in sending folks who’ve been in the depths of the system and experienced psychiatric oppression directly through law school.

-Sera

Report comment

Lots of idealistic law students are out there already, but unless they are educated in demolishing concepts such as “mental illness” on the stand and exposing psychiatry’s basic principles as bullshit we’ll end up with another generation of lawyers arguing for the “right to treatment,” “least restrictive alternatives,” and other accommodations to the psychiatric gulag which have nothing to do with the basic fraud and Carrollian logic (as in Lewis) underlying psychiatric oppression. (Wondering what Tina M might have to say about this.)

Report comment

I don’t mean young idealistic law students. I mean some of us who already get it getting funded to become lawyers.

Report comment

It has been one of my hopes is that the lawyers get involved.

In Canada, not so much, because we have chicken lawyers that know they will go broke defending.

Although if lawyers wanted to cash in, a few would be willing to bring it to the forefront, so that eventually lawyers everywhere could benefit.

Lawyers and shrinks are kinda cut from the same cloth. Getting rich from wretched society as they go home to their vid cam attached to their houses and garages.

Report comment

Sam, I am a lawyer, since the 90’s. The psychiatric system has to be reformed. The legal system has to be reformed as well. The rules in the psychiatric system violates human rights and the abuse is concealed. It’s not an easy problem to solve. I’ve met doctors who refused to hand over records for patients…I never saw it as a financial issue. I’ve always felt that the psychiatric system was convoluted. They abide by their own ways. The judges don’t even know. The awareness is limited. And I’ve met doctors that were very helpful and very human. I find that the systems quash the individual who wants changes and it becomes very difficult. What’s the solution – one person at a time or legislative changes? I wouldn’t be so open about my disdain for the medical system if I were not dying. But I am. I still look at both systems in the optic that improvements can be made. Now I can’t walk anymore, I started dialysis last week, and I’m still trying to figure out how to make things better. I guess I just wanted to say both professions are not cut from the same cloth – not even close, in my opinion.

Report comment

Psychiatry cannot be reformed; it must be abolished, as it is based on fraudulent principles and precepts. It’s not a matter of “good” vs. “bad” shrinks.

Anyway, wishing you well in this newest struggle of yours.

Report comment

Perhaps they are not cut from the same cloth, but we know that the fabric itself, our society is permeated by a psychiatric model.

It seems only natural that judges/lawyers/teachers and every institution out there should be educated on and about anti-psychiatry and why it exists. That it does not exist because of some radical thought, some rebellious cretins.

All institutions should be WANTING to hear the opposing views.

Surprisingly they listen to Dr Breggin, but only if push comes to shove. Proving you need to be much more than a patient, x patient, to be heard. In effect, peoples own experience has zilch meaning.

One cannot enter a court of law and be their own defense.

It has always been about the majority and one can only get the opinions and facts out.

Psychiatry is a silencing system. Lawyers are not allowed to let emotions or ‘opinion’ to be used in court.

After all, psychiatry is a medical practice.

I do think if x number of cases were won, simply by patient and lawyers, it would weaken the fabric.

It sucks to be sick redcat. An ugly part of life.

I also live day to day, which is ok, but illness makes it a bit harder.

Report comment

Being in a postion to kill your mistakes means never having to say your sorry.

Good work Sera

Report comment

Thanks, boans, yeah… it’s not just individuals psychiatrists… the system itself expects providers to protect not only themselves but each other…

Report comment

Another terrific article Sera; thank you. Psychiatry can’t be abolished without a war. Psychiatry has become a religion with many followers who are desperate and in pain. Science can no longer justify it’s existence or methods yet it will go on based on the “Bible” that is the DSM and the faith proselytized by the preachers of “evidence based medicine”. As such this religion has become powerful and wealthy and will not yield its power unless it is defeated by a greater powerful force (and what is that?). People must be protected from this religion’s injustices and we must maintain and strengthen all measures to do so as long as it exists. And your wonderful film project relates to this. Those closest to those in pain are confronted with the task of providing compassion and empathy on the front lines. This is a natural human process between people not a “clinical or medical process”. Those not taught to be “clinical” initially understand but are confronted by the “vows” they have taken to live by the tenets of their religion and the threats of acting against the authorities. Those priests who wish to have in their congregation anyone who wishes to be there and marry any of their parishioners gay or otherwise. It is not surprising your initial findings between the three groups; this is powerful human behavior.

As you quote “Jim Gottstein’s ‘transformation triangle’ through which he argues that it is creation of alternatives + shifting public opinion + legal pressure (I forget what language he uses precisely) that will lead us to real change overall”

Are we not at a time where the first two changes in the transformation triangle are available; alternatives and changing public opinion? And this might not represent changing the old but building the NEW. As in any religion if it is not meeting the needs of its congregants and something else is available that does people change. It is not a religion people are seeking but relief from suffering. My hope in the near term is to put great time, labor and whatever resources we can muster working in these areas. There is hope here. Many are dissatisfied with what psychiatry provides but don’t know there are alternatives. Many can relate to our messages couched in human terms regarding pain suffering and trauma. Many are fed up with the overmedication of their children and the horrors of all the long term effects of all the drugging, forcibly detaining (if alternatives are known) and electrifying . They just don’t know what else to do or where to turn. We each have to start within our own communities. We have to make connections with local comunity organizations rather than putting all our resources into large national organizations (NAMI e.g.) that wielld as much power as the APA or Big Pharma. Change from the bottom up while we continue the top to bottom efforts.

Sera you have recently written how tired you are.. for sure. You have given to this cause so much of yourself how could you be otherwise. I truly believe this decade can begin the changes you’ve so stridently fought for. There is reason for hope.

ken

Report comment

I’m not entirely certain that people are looking for relief from suffering, at least not all or most. I think a lot are looking for UNDERSTANDING and CONNECTION, but they are offered “escape from suffering” as a weak alternative by the psychiatric industry, and told that’s all they can hope for. Understanding is more nebulous, requires more work, and can be scarier, but those who have genuinely experienced understanding from another person after working through some pain know it is far superior to merely escaping. Because the escape offered by the psychiatric industry is not very different than getting drunk to forget one’s pain – once one “sobers up,” the pain remains in place and needs to be avoided yet again. To reconsider that pain from a new perspective can not only ease the pain, it can provide meaning for one’s suffering and pathways to create a better life going forward, something no drug can ever begin to deliver.

Report comment

Just reading posts such as yours Steve and Kenneth’s above, are so freeing.

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Steve. I agree that many are not seeking pain relief but connection, understanding, and support to make meaning of their own experiences.

-Sera

Report comment

Psychiatry can’t be abolished without a war.

Psychiatry is basically a one-sided war against the people at this point. We need to organize the people in order to correct that.

Report comment

Yes and I see the process of that happening much like Kenneth does. To abolish and reducing something as to not meaning anything on a social level takes time. But consistency.

If one looks at the system of psychiatry, at the moment it is absolutely nothing more than social control and we do not need cops and psychiatry. It is one or the other.

We also have no use for medicine if it involves psychiatric training which it does.

The systems in place have left people with few or no options and that is one hell of a bust system.

Report comment

we do not need cops and psychiatry. It is one or the other.

Or maybe they should both operate from police headquarters.

Report comment

Our new Mental Health Act placed an “authorised mental health professional” in every major police station in the State. The potential for abuses is massive. I think I mentioned speaking to a MH nurse recently and he tells me that the system is “working well”, which is great coming from someone who is a believer in the methods being used by Deterte where police are judge, jury and executioner.

One of my complaints regarding my treatment was that I walk into a police station after being spiked with a date rape drug (and have the documented proof) only to be referred to mental health services for treatment for my “hallucinations”? Now I only got kidnapped after being ‘spiked’ so what are they doing with people whoi are being sexually assaulted after being ‘spiked’? Are they ending up being ‘treated’ to silence them, rather than do all that paperwork and stuff? Does it depend on who is doing the complaining (ie the bi$%h was asking for it, refer for brain damage. My friends daughter, refer to Public Prosecutor?). Because from what i’ve been told police dont have a copy of the criminal code for anyone they deem to have a mental illness, which means you can literally abuse them to death and not a thing will be done. They will assist in restraining people to be treated by human rights abusers.

Our ‘system’ opens up a fast track for perverting the course of justice. In fact consider this. Given what was done to me our police can now have people ‘spiked’ with date rape drugs before interrogations and have this authorised by the AMHPs. We’ve made torture lawful 🙂

Report comment

I wasn’t looking for anything when I was ‘spiked’ and jumped in my bed. It seems to me that there is something being overlooked in the comments above, that a lot of these folk are having this crap shoved down their throats against their will, not that they are “seeking help for their trauma”.

This ‘industry’ is a means for governments such as mine to enable some of the most vile human rights abuses in history. And given the use of chemicals to torture, maim and kill people on an unprecedented scale? And let me say in the process maintain a ‘holier than though’ stance while torturing citizens and killing them if they complain about it. I mean my government had the cheek to complain about what was done to Jamal Khasshoggi by the Saudi government. Really? Have these people visited a locked ward of a mental institution lately? These places have become franchises of Guantanamo where the rules are ignored. Zimbardos ‘prison experiment’ put into action much like the situation at Abu Ghraib and the ability to deny any responsibitlity should the public become aware. Bad apples, isolated incidents etc, when the truth is this was the intent the whole time.

Take a look at this letter I have from the Chief Psychiatrist. This is someone ‘pretending’ they don’t even understand a burden of proof. Why? To enable arbitrary detentions and torture and ensure the victims have no remedy to abuses. Point out the facts and you are targeted (along with your family) and if you have support, you are ignored. You are denied access to effective legal representation, and police tell you that they don’t have a copy of the Criminal Code whilst arranging for the criminals to come and pick you up from their station because your “hallucinating” if you think being interrogated whilst spiked with stupefying drugs without your knowledge is torture. Clearly a breach of the Convention against Torture on the part of the State Government but who cares when you have the power to kill people in the Emergency dept.

I was not a “patient” and therefore these were crimes. We don’t like that truth so we have prepared fraudulent documents to be distributed and are going to ignore your facts and evidence for a reality we would prefer. And of course many here at MiA know what is being disguised as ‘medicine’.

9 years on and they still sit on their hands because they hate the truth that they torture and kill citizens and conceal it with fraud lies and threats to peoples families if they are exposed.

Report comment

well boans, I think forced drugging of adults and children should be abolished completely.

I’m not sure why this is not on the table.

No psych unit should be allowed to operate without a watchdog in the unit who is present at all interactions.

The watchdogs should be peers that are anti-force, preferably anti-psychiatry and cameras allowed.

If there is nothing to hide, I am sure watchdogs should not be a problem. The committees should be half psychiatry, half anti-psychiatry.

If it sounds undoable I guess it’s because psychiatry needs this, and they have PLENTY to hide.

The only “advocates” and “watchdogs” governments ever instate in systems, are ones who are part of the system.

Report comment

No psych unit should be allowed to operate

Why not leave it at that without the caveats?

Report comment

The ‘watchdogs’ in my country are sychophants. They do exactly what they are told if and when they come across human and civil rights abuses. Because what we are dealing with is effectively a reign by terrorists in much the same way that the National Socialists terrorised certain sections of the communtity in Germany ala 1940s

I dont know that I would have wanted a ‘watchdog’ then who saw ensuring that the removal of gold teeth from their victims was done with dignity and humanely as a success and that they were being ‘effective’ I’m with oldhead on this one, shut these places down, remove their powers and march them past the corpses.

These things simply don’t happen overnight, but are a gradual regression into a collective insanity. Were going mad folks, not us as individuals but us as a society. And the ‘medications’ were trying are making things worse not better.

Report comment

Agreed Steve. It’s very hard. Not only understanding, empathy, connection; add time, perserverance, being with and in it with another, tolerating all the uncertainty of change ever happening, and of course essential supports safety, security meaning and purpose via housing, job and relationships.

Report comment

Agreed oldhead. I’m advocating not entering a direct fight with a power that has the resources to crush anything that directly threatens it. You say it best “We need to organize the people in order to correct that.” Not only organizing people to advocate for change in the current system; that’s being done by many groups around the country to protect the rights and prevent abusing those in the system but also seeking local community connections offering direct non medical services. If people know of and have choice of something else perhaps gradually the system can be starved and weakened.

Report comment

I’m advocating not entering a direct fight with a power that has the resources to crush anything that directly threatens it.

That’s why we have strategy.

You can’t “advocate for change” in a system which is inherently fraudulent and corrupt. You organize to defeat it. We don’t need “services.” We need revolution.

Report comment

I’m not advocating for change of the current system; as Sera says we are losing ground. We do have to protect those facing injustices in the fraudulent system as their civil rights continue to be violated.

Now that we can be free of the medical model to pursue a humanistic way of being with others who seek “connection, understanding, and support to make meaning of their own experiences” (thanks Sera) we have the power to move forward unemcumbered by the restraints of insurances and costly medical services. I believe psychiatry eventually is doomed to fall since it is antithetical to human strivings. How to topple it? Revolution? I don’t know. But I do know if we have the resolve and committment and perserverance peer led communities could conect with their local communities and forge new alliances addrssing their needs.

Report comment

Kenneth Blatt, MD, I believe that you underestimate the power of psychiatry to dominate the “mental health” care industry based on its purporting the “hard” sciences of biology and physiology – natural science. But while neurology is the medical science that addresses the biology and physiology of the brain, psychiatry is philosophy – an illegitimate medical science advocating the Myth of “mental illness.”

We are not “free of the medical model” when the pain of social, economic and/or spiritual distress causes sleep deprivation and resulting disorientation. The coerced “medical” treatment that results is a harmful violation of human rights as mandated by the UN Commission on Human Rights (1948). Until medical schools stop accrediting psychiatry as a medical science, it will continue iatrogenic harm of historic proportions.