Editor’s Note: Over the next several months, Mad in America is publishing a serialized version of Peter Gøtzsche’s book, Mental Health Survival Kit and Withdrawal from Psychiatric Drugs. In this blog, he begins a discussion about discontinuing psychiatric drugs. Each Monday, a new section of the book is published, and all chapters are archived here.

As noted above, it took almost 30 years before the psychiatric profession and the authorities admitted that benzodiazepines are highly addictive. Propaganda is highly effective, and the reason it took so long is that it was a big selling point for the drug industry that they were not additive, in contrast to the barbiturates that they replaced, just as it became a big selling point around 1988 that the newer depression pills were not addictive, in contrast to the benzodiazepines they replaced.

The lies do not change, for the simple reason that the drug industry doesn’t sell drugs but lies about drugs, which is the most important part of their organised criminal activities.1 The industry is so good at lying that it took about 50 years before the authorities finally admitted that the depression pills are also addictive. Even after this colossal delay, they are not yet ready to call a spade for a spade. They avoid using words like addiction and dependency and talk about withdrawal symptoms instead.

The worst argument I have heard—from several professors of psychiatry—is that the patients are not dependent because they don’t crave higher doses. If true, this would be good news for smokers who, after smoking a pack of cigarettes every day for 40 years can stop overnight, without abstinence symptoms.

Patients don’t care about the academic wordplays whose only justification is to allow the drug companies to continue to intoxicate whole populations with mind-altering drugs. The patients know when they are dependent (see Chapter 2); they don’t need a psychiatrist’s approval that their experience is correct, and some say the withdrawal from a depression pill was worse than their depression.2

Progress is very slow. In a 2020 BBC programme, the mental health charity Mind said it is signposting people to street drug charities to help them withdraw from depression pills because of the lack of available alternatives. Alas, homage is always paid to the wrong ideas people have been brainwashed into believing: “Although they are not addictive, they can lead to dependency issues,” a voice-over told the viewers. Haven’t we heard enough nonsense by now?

One of the most meaningful things a doctor can do is to help some of the hundreds of millions of people come off the drugs they have become dependent on. It can be very difficult. Many psychiatrists have told me that it is much easier to wean off a heroin addict than to get a patient off a benzodiazepine or a depression pill.

The biggest obstacles to withdrawal are ignorance, false beliefs, fear, pressure from relatives and health professionals, and practical issues like the lack of medicines in appropriately small doses.

Very few doctors know anything about withdrawal and make horrible mistakes. If they taper at all, they do it far too quickly because the prevailing wisdom is that withdrawal is only a problem with benzodiazepines and because the few guidelines that exist recommend far too quick tapering.

The situation in the UK improved in 2019 (see Chapter 2) but I have seen no improvements yet in other countries and here is an example. In November 2019, the Danish National Board of Health issued a guideline about depression pills to family doctors, which was enclosed in the Journal of the Danish Medical Association, ensuring everyone would see it.

The sender was “Rational Pharmacotherapy,” but it wasn’t rational. As the guidelines are dangerous, I wanted to warn people against them, but I knew from experience that it doesn’t work to complain to the authorities, which think they are beyond reproach. I therefore published my criticism in a newspaper.3 The Board of Health was given the opportunity to respond but declined—another sign of the arrogance at the top of our institutions, as it is a highly important public health issue.

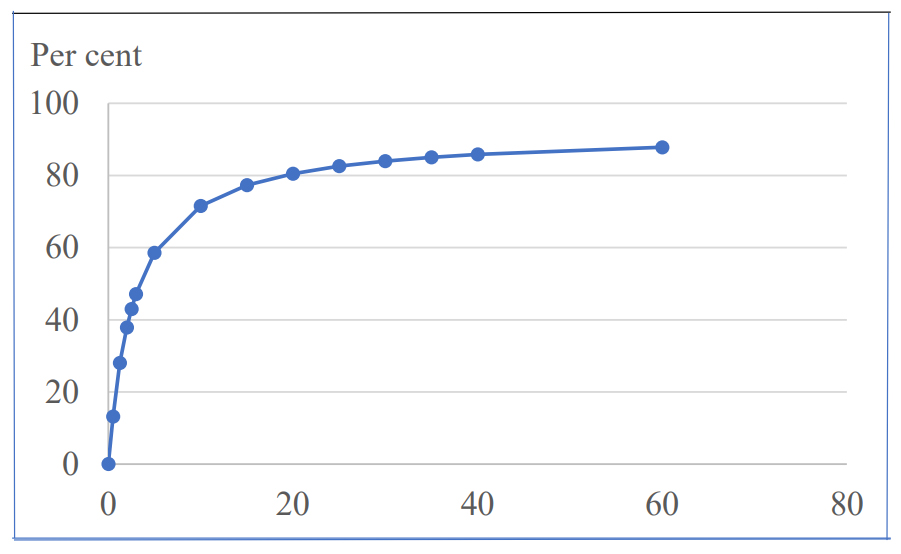

Although the author group for the guideline included a psychiatrist and a clinical pharmacologist, they didn’t seem to know what a binding curve for depression pills to receptors looks like. As with other medicines, it is hyperbolic. It is very steep in the beginning when the dose is low, and then flattens out and becomes almost horizontal at the top (see figure).4

This is important to know. The board recommends halving the dose every two weeks, which is far too risky. At usual dosages, most receptors are occupied because we are at the top of the binding curve where it is flat. Since virtually all patients are overdosed, they might remain on the flat part of the binding curve after the first dose reduction and not experience any withdrawal symptoms. It could therefore be okay to halve the dose the first time.

But already the next time, when going from 50% of the starting dose to 25%, things can go wrong. Should the withdrawal symptoms not occur this time either, they will almost certainly come when you take the next step and come down to 12.5%.

Hyperbolic relationship between receptor occupancy and dose of citalopram in mg

It is also too fast for many patients to change the dose every two weeks. The physical dependence on the pills can be so pronounced that it takes months or years to fully withdraw from the pills.

Fast withdrawal is dangerous. As noted earlier, one of the worst withdrawal symptoms is extreme restlessness (akathisia), which predisposes to suicide, violence and homicide.

A withdrawal process should respect the shape of the binding curve, and therefore become slower and slower, the lower the dose. These principles have been known for decades and were explained in an instructive paper in Lancet Psychiatry on 5 March 2019 by Horowitz and Taylor.4 Since my colleagues, who have withdrawn many patients, and I have written repeatedly about the principles in national Danish newspapers and elsewhere since 2017, there was no excuse for the people working at the National Board of Health for not knowing about them.

Psychiatric drugs are the holy grail for psychiatrists, and they are the only thing that separate them from psychologists, apart from their qualification as doctors. You would therefore expect huge pushbacks from the psychiatric guild and its allies when you tell people the truth about these drugs and start educating them about how to safely withdraw from them.

This happened to me, on many occasions. As noted in Chapter 2, my opening lecture at the inaugural meeting for the Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry in 2014 was immediately attacked by the top of British psychiatry. The Council was established by filmmaker and entrepreneur Luke Montagu who had suffered horribly from withdrawal symptoms for many years after he came off his psychiatric drugs, and he wanted to highlight their harms.

I mentioned Luke’s name in 2015 in an article I was invited to write for the Daily Mail.5 It came out two weeks after I had published my psychiatry book where all the evidence was.6 The editor made many changes to my article and insisted that I added this statement: “As an investigator for the independent Cochrane Collaboration—an international body that assesses medical research—my role is to look forensically at the evidence for treatments.”

My research was publicly denigrated by the Cochrane leaders who uploaded a statement that is still up.7 They claimed that my statements about psychiatric drugs and their use by doctors in the UK could be misconstrued as indicating that I was conducting my work on behalf of Cochrane. They also said that my views on the benefits and harms of psychiatric drugs were not those of the organisation.

Cochrane has three mental health groups that have published hundreds of seriously misleading systematic reviews of psychiatric drugs where the authors did not pay enough attention to the flaws in the trials but acted as the mouthpiece of the drug industry.6

Cochrane tried to disavow my conclusions about psychiatric drugs, but the organisation cannot have any “views” on such issues that carry more weight than those of a researcher who has studied them in detail. But the tactic worked, of course. Five days after they uploaded their statement, BMJ published a news item, “Cochrane distances itself from controversial views on psychiatric drugs.”7

Both then and subsequently, Cochrane’s support of the psychiatric guild and the drug industry was widely abused by leading psychiatrists. David Nutt (see more about him in Chapter 2) said during a lecture in New Zealand in February 2018 that I had been kicked out of Cochrane. He was seven months premature.7

Luke wrote about his own “career” as a psychiatric patient in the Daily Mail article.5 The symptoms were of such a nature and severity that I at first found it hard to believe him. I had never learned about anything remotely similar to this during my medical studies or later. But I quickly realised that Luke was not kidding and had no psychiatric condition whatsoever but was a lovely person who had unwittingly fallen into the psychiatric drugging trap.

Luke, heir to the Earl of Sandwich, had a sinus operation at age 19 that left him with headaches and a sense of distance from the world. His family physician told him he had a chemical imbalance in his brain. The real problem was probably a reaction to the anaesthetic, but Luke was prescribed various depression pills that didn’t help.

None of the other doctors and psychiatrists Luke consulted listened either when he said it had begun with the operation. They offered him different diagnoses, and all gave him drugs; nine different pills in four years. As it so often happens, Luke reluctantly concluded that there was something wrong with him. He tried to come off the drugs a couple of times but felt so awful that he went back on them. He thought, which is also typical, that he needed the medication although what happened was that he went into withdrawal each time.

In 1995, he was given Seroxat (paroxetine) and took it for seven years. When he tried to come off it, he felt dizzy, couldn’t sleep and had extreme anxiety. Thinking he was seriously ill, he saw a psychiatrist who gave him four new drugs, including a sleeping pill. He quickly felt better, not realising he had become “as dependent as a junkie on heroin.”

He functioned okay for a few years, but gradually became more and more tired and forgetful. So, in 2009, believing it was due to the drugs, he booked into an addiction clinic. His psychiatrist advised him to come off the sleeping pill right away and within three days he was hit by a tsunami of horrific symptoms—his brain felt like it had been torn in two, there was a high-pitched ringing in his ears and he couldn’t think.

This was horrible malpractice. Rapid withdrawal from long-term use of a sleeping pill is a disaster. The detox was the start of nearly seven years of hell. It was as if parts of his brain had been erased.

Three years later, he very slowly began to recover, but he still had a burning pins and needles sensation throughout his body, loud tinnitus and a feeling of intense agitation.

When I last met with Luke, in June 2019, he was still suffering from withdrawal symptoms but was able to work full time.

He is determined to try to help others avoid the terrible drugging trap. After setting up the Council, Luke founded the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Prescribed Drug Dependence (APPG), which successfully lobbied the British Government to recognise the issue. He recruited the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Psychiatrists to support this. That led to a ground-breaking review by Public Health England with several key recommendations, including a national 24-hour helpline and withdrawal support services.8

These recommendations do not only focus on the traditional culprits, opiates and benzodiazepines, but also on depression pills. In December 2019, the APPG and the Council published the 112-page “Guidance for psychological therapists: Enabling conversations with clients taking or withdrawing from prescribed psychiatric drugs.”9 This guide is very detailed and useful, both in relation to the drugs it describes and in terms of the concrete guidance it offers to therapists.

It became more and more difficult to ignore the huge problem with patients who are dependent on depression pills. In 2016, I co-founded the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal (iipdw.org), based in Sweden. We have had several international meetings and have established a network of like-minded people in many countries, and the interest in finally doing something is spreading fast.

I have lobbied speakers on health in the Danish Parliament for over 10 years and they were always positive when I explained why major changes are needed in psychiatry. But they are afraid of going against the psychiatrists who are quick to tell them that psychiatry is outside their area of expertise. Therefore, nothing substantial has happened.

In December 2016, there was a hearing in Parliament about why withdrawal from psychiatric drugs is so important and how we should do it, which was also the title for my talk. There were contributions from a psychologist and a pharmacist with experience in withdrawing drugs and from a patient relative. There wasn’t a single psychiatrist with experience in withdrawal on the programme.

The only psychiatrist was Bjørn Epdrup who explained when and why neuroleptics are needed—and forgot to tell us when they are not needed—and he said that he could see schizophrenia on a brain scan. This isn’t possible. Scanning studies in psychiatry are highly unreliable,6 but Epdrup left the meeting before anyone could confront him with his claim. The only thing that can be seen on a brain scan is the shrinking of the brain that neuroleptics have caused!6,10,11

In January 2017, I was invited to give a talk at a meeting about overdiagnosis and overtreatment in psychiatry in Sherbrooke, Canada. The meeting was accredited and counted in the physicians’ continued education portfolio. Even though most of audience were psychiatrists, 74 of the 84 participants felt my presentation had responded to their needs. I had not expected this, particularly not after the somewhat tense discussion.

I felt a change was on its way. Two months later, psychologist Allan Holmgren and a political party arranged a conference in Parliament with the theme: “A psychiatry without drugs.” Robert Whitaker lectured about the psychiatric drug epidemic and my title was also direct: “The myth about biological psychiatry: The use of psychiatric drugs does far more harm than good.”

To read the footnotes for this chapter and others, click here.

Thank you Dr Peter for this contribution,

“…These principles have been known for decades and were explained in an instructive paper in Lancet Psychiatry on 5 March 2019 by Horowitz and Taylor…” – This has got to be true, but it’s a good service to have it recorded in Black and White.

Report comment

Peter, I am enjoying thinking you are a listener. I liken the erasing of the reality of schizophrenia illness, whether anyone cares to call it that or not, to the current enthusiasm for erasing of the word “woman” or “man”. Erasing is nearly always done by folks who have felt nothing of the despair of real schizophrenia. I met one or two in the Hearing Voices Network who volunteered as non schizophrenic group leaders. They seemed to me like sudden armchair colonislists who have never been in the schizophrenic tribe and have never had a moment of schizophrenia in their life. How can it be that someone who has NO experience of an illness can wish to abolish the reality of it? The laughable and tragic thing is how do these people expect to draw funding into their charity boxes to fund wonderful alternative things like Soteria houses, which in my opinion are the way forward, if…there is no such thing as schizophrenia? Are we to call Sotieria houses places for the terribly upset? I would like to see that work on a charity box…The whole world will say “everyone on the planet is terribly upset and needing to keep all our charity coins for our big upset”.

I understand that abolishing or erasing or crushing the pharma pill seems to require crushing the supposed illness it was given for, but I know my schizophrenia is real, however you care to treat it. I think those who are vociferous in wanting to erase that word, may clutch it back when needing to fund a new paradigm of care. In the meantime us schizophrenics continue to be shouted at by people who do not know anything about the hellish lived exeperience of it. And my slight concern is that in getting rid of pills and getting rid of psychiatrists and pooh poohing psychology what on Earth is going to be left for those who know full well what their torment is but dare not speak its name….

I have schizophrenia.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/not-guilty-by-reason-of-insanity-inside-the-central-mental-hospital-1.3544665

“…Patients who come to the Central Mental Hospital from the criminal courts have usually pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, or NGRI for short. The most typical patient is a man suffering from schizophrenia who has stopped taking his medication and has killed a family member – often a parent….”

It’s well known Medically that people that come off Strong Psychiatric Drugs abruptly can go completely MAD – even if they were completely SANE to begin with.

Report comment

Two cases of Familicide in the Irish News Website RTE – today

Mother pleads not guilty to murdering three children

http://www.rte.ie/news/courts/2021/0517/1222181-trial-children/

Man accused of murdering wife, children to face trial

http://www.rte.ie/news/courts/2021/0517/1222094-sameer-syed-court/

( With AKATHISIA Doctors are Deliberately Hiding the Information:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vYO9r1FkdJSv8Bi8Q3c3u9WXNZXkmxvO/view?usp=drivesdk )

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

thanks for this and all your other work. seriously. I live in the US, where direc to consumer drug ads have been legal for a while (maybe 20 years, now?), and the (highly profitable) pill for every ill outlook is more or less inescapable. Your work is…not to be cliche or anything, but…truly, a breath of fresh air (and much needed honesty, of course).

I just wanted to jump in and say that psych drug discontinuation is a tricky business, indeed. What strikes me, having somehow survived it in years past, is the cruelty of psychiatrists. I don’t doubt that family doctors make mistakes, but with the psychiatrists, it is truly cruel, sometimes to the point of true sadism. rapid tapers of high potency benzodiazepines, for instance. My own opinion is that this is not any sort of ignorance on the psychiatrist’s part, it is, rather, yet another example of deliberately inflicted pain and harm by pseudo-doctors.

as a side note: I have personally found high dose supplementation (inspired by old school Orthomolecular) quite helpful in facilitating psych drug discontinuation. In the older literature, one reads about MDs prescribing (often surprisingly low, given the era) doses of neuroleptics alongside vitamin therapy. The more modern literature I have come across is surprisingly honest in their assessment of neuroleptics (in particular) as damaging and the potential for careful supplementation to save people/’patients’ from an early grave, ongoing disability, etc.

Thanks, yet again. 🙂

Report comment

In his book, Peter says that the Care Institute in the Netherlands (ZiN) opposes the reimbursement of medication in small dosages to taper in a safe way (taperingstrips) Thanks for mentioning!

Can you imagine? Such a governmental institution of a country from which this important innovation came about!

The same goverment decided to spend 24 million euros on a project to improve the prevention of suicide.

Our Patients Association suggested to also pay attention to the awareness of the increase in the risk of suicide of withdrawal, protracted withdrawal and akathisia, and the need for adjustments of the guidelines on these points. Their answer; ‘ Maybe we do this in one and a half year’

Report comment

Psychiatrists don’t want to admit their drugs are highly physically addicting. Instead they use the drug harm of withdrawal to manipulate the people they harmed into believing the drugs are helpful.

Even the studies used to claim the drugs are helpful are designed to take people addicted to the drugs and withdrawal them.

Report comment

Yes, you’re right, but, according to these psychiatrists, etc. is that withdrawal symptoms, effects, etc. only prove that you are SICK and in need of these evil drugs. I think they call this obfuscation, but this dangerous obfuscation because, it maims, damages, disables, disturbs, and sometimes even kills. The “cure” is worse than the “disease” because there is no “disease.” Thank you.

Report comment

Yes, Rebel, my schizophrenia is everything I choose to believe it is. I believe it is a disease. Tomorrow I may call it trauma. The day after I may call it the will of God. The next day I may call it malnutrition. The following day I may call it schizophrenia again.

IT IS ALL UP TO ME how I regard what is the matter with me. It is my “free choice”. IT IS MY BODY. IT IS MY BRAIN. NOT YOURS.

I wonder does my free choice to know “me” disturb you? Someone can believe in the Virgin Birth and I just say nothing so as not to insult their “free choice”. I do not follow their every comment with irrefutable proof it cannot be true. That would be bullying. I feel people on this site should feel free to define the cause of their emotional troubles in any way they deem healing. If a ninety year old schizophrenic came on this site, one who had never had antipsychotics, and never would, and told you they believe they have a disease would you berate their free choice? And if so what does that honestly achieve in your life if you pressure them? Can they not be regarded as having the ability to think for themselves?

You may be able to say that you believe there is no disease of the specific chemical or genetic sort that science initially linked to that disease and thought was the location of it in the brain, but that was evidently science getting it wrong again as science often does in its pursuit of causes. Science used to think MS was not a brain disease, and yet we now know it is. Science stuffs up routinely. It does not mean there is NOT a disease. Rickets is a disease caused by lack of vitamin D. It is a real dis-ease. Scurvey is a disease csused by lack of vitamin C. It is a real dis-ease. Both can cause depression. You could say depression is not itself a disease but is a symptom of disease. Well so is DEATH a symptom of disease. I dont much give a damn about what an individual with “free choice” chooses to call their illness. Whatever helps them cope with it is fine by me. I suspect you get muddled between the travesty that is the “treatment” and the innocuous names by which we are ALL entitled to call our soreness. My calling my illness a disease helps me understand it better. My using that word on myself does not construct a pharmaceutical industry that might want to sell me pills to treat it. I do not “cause” psychiatry. I am blameless. My saying I feel I have a speckled carpet does not mean I “cause” a vaacuum cleaner industry to suddenly fall out of the sky in to my street with its door to door vaaccum pushing salesman.

Report comment

A disease or illness is a biological abnormality that causes negative effects. Every psych drug causes chemical, biological and brain abnormalities including brain damage. You are 100% correct. By definition the cure (psych drugs) is the disease.

Report comment

Peter, it is my belief that akathesia I experienced on antipsychotics is NOT the same hyperarousal cortisone and adrenalin state experienced in withdrawal. Nor is it the extreme restless leg syndrome that comes after quitting antipsychotics. Both the hyperarousal state and the restless leg syndrome state could push someone to suicide. However, akasthesia is a far, far worse cause of suicidal impulse, both of which lessened dramatically AFTER I quit antipsychotics. I belabour this point because if people think ghastly akasthesia is going to occur post quitting then that untruth disincentivizes people to quit. Really there should be a new name given to the experience of riotous restlessness and hyperarousal post quitting. I can say that both of those in combination are really very unbearable and even worse than akathesia, but the good bit is that like the agony of childbirth, they do not last. Maybe six months. It was worth it to go through those six months in my case. Yes I felt I could not bear it at times, and this could lead some to throw in the life towel. But proper actual akathesia from being on antipsychotics is a whole other depth of awfulness that caused me suicidal ideation every day. The lifting of akathesia, through quitting my meds, lifted that daily toll of suicidal impulses in a blessed way for me. Within days of abruptly quitting that relentless akathesia and suicidality also abruptly ceased, but what it was replaced with was like psych withdrawal childbirth that dragged on for six months. That childbirth state was horrendous, however it was not continuously awful since it also had the brain derailed effect of ecstatic elevated mood at times, and the eupohoria from those intermittent phases of withdrawal sort of “medicated” the flipside of that hyperarousal which was an adrenalin sense of impending doom. So ironically, the curse of withdrawal symptoms can flip into a blessing, and it can flip over unendingly many many times a day, and this flipping can lead to a sense of overwhelm and pandemonium and exhaustion but also exhilaration after a decade of all feelings being squashed to a dull flat akasthesia drudgery.

Because my experience was abrupt withdrawal I got the help of that flipping into euphoria, which became a trusty companion on my voyage, explosively showing up every two hours or so. It is not unlike the body capture that paralyses or animates you on LCD but without the visuals and is a trip of six months. However, Peter, although I am reticent of people withdrawing fast, as I feel that must be excruciating for the brain, even though people do cope with something like a motorcycle crash okay, I am not convinced that long tapering is that great either, given that akasthesia made feel suicidal every day, in a way that withdrawal did not, and given that it is possible the turbo charge rocket fuel of euphoria, something that occurs in actual childbirth, was actually really helpful to keep me on the withdrawal path, I mean I thoroughly enjoyed those reviving sips of hypermania, if a long taper squashed all of that thrilling exuberance and dragged on my akasthesia suicidality I might not be here writing this to you. I quit hard and fast and I found it helpful. But I have alot of experience in talking myself down from metaphorical panicky tall buildings. Many naive people may not know how to do that. Again it is like childbirth. So learning lots of techniques about how not to panic is best, BEFORE quitting. And I think a medium length taper may be better than a forever taper. I needed the bursts of euphoria, which also felt extremly physically “restless” but for me I KNOW that was NOT akasthesia. It was worse, it was relentless hyperarousal. But it was temporary. Although I have been left with bothersome restless leg syndrome, it is NOT akathesia. Will it develop into parkinsonism? Well that was probably on the menu anyway, on the first day of my taking an antipsychotic.

I think alot of people on antidepressants have not experienced true akathesia of the antipsychotic induced sort. They may have felt over stimulated or panicky or anxious but NONE of these are akathesia. I think what is then happening is they are hearing all about this scary thing called akasthsia and are assuming their over stimulation or panic or anxiety is it. Then when they withdraw from antidepressants they may experience over stimulation and panic and anxiety IN the brain derailment of quitting that leads to extreme hyperarousal. The hyperarousal is like over stimulation and panic and anxiety maxed up to the hellish hilt of human endurance. They are then of a mind to call that also akasthesia, even though they may never have actually experienced true akasthesia either before, whilst on antidepressants, nor off. By true akasthesia I mean the sort I ONLY EVER got from several brands of antipsychotics and NEVER from dozens of brands of antidepressants. There may be a disservice being done to schizophrenic and bipolar sufferers who HAVE years of experience of true akasthesia. If a person on antipsychotics wants to discontinue those meds and is constantly being heckled by the antidepressant quitters that they WILL still get apparent akathesia AFTER they withdraw, believe that this will cause deaths in schizophrenic and bipolar antipsychotic takers, who maybe derive no benefit from such meds, who dread now coming off since all they hear is that quitting causes what they already have in terms of true akathesia, which in my opinion is grave error of sensationalism. Why the sensationalism wont be corrected is that is many antidepressant takers and quitters are in a hurry to debunk the reality of schizophrenia and bipolar anguish so that all mental illnesses can be squashed nearer to what is only standard depression or anxiety, possibly so those with only these kinds of illness feelings can present themselves are the epitome of abject suffering, in the absence of any competing narrative. The depressed or anxious are morphing themselves into the new schizophrenics and bipolar sufferers by claiming they suffer the same symptoms, or the symptoms dont exist, and by claiming that torments like true akathesia are what they have. All of this is murky.

Report comment

“I think alot of people on antidepressants have not experienced true akathesia of the antipsychotic induced sort. They may have felt over stimulated or panicky or anxious but NONE of these are akathesia.”

It may have been your experience, but everyone metabolises drugs differently and have different food interactions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEoSs6Yo0DA

https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/121610p26.shtml

Report comment

Dear Peter, I am responding to Streetphotobeing, but want you to freely listen, since it may intrigue you too.

First, Streetphotobeing, you make an excellent point. Everyone is unique. Yes, yes indeed.

Politely, I would enquire, interestedly, if you yourself have experienced being on antipsychotics, and had or did not have true akasthesis on them. I need no answer. But I shall say that philosophically that would maybe be more illuminating to me than watching a video.

I have friends who are on antipsychotics and I have friends on antidepressants. Those on antidepressants can invariably sit in a chair for a whole hour.

I long for a proper study to be conducted to explore if there is a distinction between antipsychotic induced akathesia and the jumpy sensations of panic that all withdrawers experience. I think that would be really fascinating and may give us all more info on what all of these different drugs are differently doing to us. But I think that in the haste to find ALL drugs harmful there is a slapdash rush to lump every drug together as if it is ALL one monster of a drug with the same effects. Like when people used to say ALL colestorol is bad. The moral panic in the ALLness way of thinking belongs to tabloid scoops. It is the enemy of nuance, and the enemy of nuance is the muffler of truth.

Secondly, Peter, I say something about this in the comments on the MIA article titled…

The ERNI Declaration: Making Sense of Distress Without “Disease”.

Report comment

Yes and I had serious akathisia/toxic psychosis for the first time only after having Sertraline and Citalopram. This was before having any idea of akathisia. I am well aware of how horrific it is and the denile of the cause by the medical and MSM establishment even the alternative media like UK Column News do not seem to want to bring it to light.

“I long for a proper study to be conducted to explore if there is a distinction between antipsychotic induced akathesia and the jumpy sensations of panic that all withdrawers experience.”

Yes it is well known withdrawal induces horrific akathisia, again I have had it.

My descent into hell after the Sertraline three years earlier included three stays which lasted almost a year in a psychiatric ‘hospital’ where I was gaslit, very seriously abused and almost died.

Report comment

You mention Sertraline. I have a friend stuck on it. Horrendous indeed. But Sertraline is NOT an antipsychotic. And this is why it is important never to get drugs muddled up in the attempt to acertain which drugs cause what.

It is a cheating disservice to all SSRI withdrawing people to conflate antipsychotic side effects with their SSRI withdrawal experiences, which may be FAR MORE HELLISH than antipsychotic induced true akasthesia.

There are some people who seem to itch to claim to know what schizophrenics have suffered but this does not mean SSRI’s are not WORSE.

I wish you great healing from your unimaginably dreadful Sertraline withdrawal.

Please do not reply. I am too busy just now to respond.

Report comment

Thanks Peter.

I hope young people read your blog before they see a shrink or before they send their friends to see one. Psychiatry will hurt you in one form or another.

If not the drugs, the fact you saw one will only matter within the medical or judicial system.

The practice of psychiatry is not mental health or medical related.

Drugs and labels have no business to be given if there is no identifying “medical” issue.

Report comment

Hi Peter,

You seem to be very upbeat when describing things which have improved. I would like to suggest that there is a great deal of work to be done. If l want to come off the neuroleptics l am forced to take, there is absolutley no way l am able to do this. Here in France progress is interpreted by praising psychiatric drugs and to hell with the consequences. Several deaths have occured in my circle due to iatrogenic fatal illnesses. The death certificates make no mention of the real cause of death….

Report comment

John,

My experience of Neuroleptics is that they are more likely to cause Serious Mental Health Problems than to heal them.

Report comment

Death Certificates seem to rarely make any mention of the real cause of death. Sometimes, it is a family’s decision. However, more than we would like to admit it is a cover-up of some sort. But, consider that most diagnosis are either false, misleading, outright lies and deception for all kinds of reasons. So many suffer because of those who want to avoid the truth and live in a web of lies and deceit. Thank you.

Report comment