When I was training to be a child psychiatrist in the mid-1990s, childhood depression was considered to be rare, related to adversity, and generally unresponsive to pharmaceutical treatment. Since then much has changed in a very short period of time. Even day-to-day language seems colonized by medical terminology with youngsters describing their feelings using clinical (“I feel depressed”) as opposed to more ordinary language (“I feel unhappy/sad/miserable”). Like medicalized childhood behavioural problems, medicalizing mood creates great commercial opportunities. From books to therapies there is no shortage of products that can be sold to the concerned parent or stressed teenager. Just as promoting the idea that behaviours that stress parents out can be solved by the simple act of taking a pill, the pharmaceutical industry understood the potential money to be made by promoting the concept of depression as something that affects kids in the same way as adults and that can be solved with a pill. Just as our ideas about what is expected in kids’ behaviours and how to interpret perceived problems is changed by labelling them with a ‘diagnosis’, so our ideas about and perception of suffering and resilience can be affected by such medicalizing of mood; potentially alienating the young of today from the possible learning and insight that can come out of experiences of mental distress and adversity, at the same time as distancing us from seeing the social and political sources of suffering.

McDonaldisation of growing up

I often wonder about how our understanding of children, childhood, child development, family life, and education have changed as we have succumbed to the ‘McDonaldised’ notion that the challenges and uncertainties connected with growing up can be placed into neat categories of things ‘wrong’ with individual children, which can then be fixed with simple, one-size-fits-all interventions.

Children are ultimately dependent on adults to make most decisions on their behalf. But, it seems to me, we have professionalized the process of growing up to such a degree that many parents and other adults in caring positions (such as teachers) are afraid of actively intervening to guide children in their care. They fear that they may do or say the wrong thing, given how pervasive the discourse of the fragility and vulnerability of children is. They may feel they need an ‘expert’ to best understand what the right thing to do is. Others feel judged and embarrassed by their children’s behaviour, as parents (particularly mothers) are often blamed for poor parenting, but rarely praised for good parenting. Others have been forced to work long hours leaving little time to be with their family, and often with little support as a result of diminishing local community and extended family connections.

It is hard to be a ‘normal’ parent these days. If you are judged as too close to your children you are ‘enmeshed’, too distant you are too ‘cold’ and don’t know how to ‘love’ your children in the right way. Of course abuse and harm does happen, whether deliberate or accidental, but being a parent has become an anxiety provoking experience these days with much confusion and often little emotional and practical support, particularly for mothers who continue to carry the majority of the burden for bringing kids up. There is much money to be made from this anxiety and the inevitable desire parents have to make things ‘better’ for their kids, and soothe the anxieties they feel.

Children, meanwhile, are measured, tested, ranked, and commented on in schools, sports, appearance, social media, and so on, such that they, from a young age, learn that they get value from what they do, rather than for just being. Like living in an ongoing X-factor contest, they may feel scrutinised for how they ‘perform’ as individuals, more than how they contribute to the common good and being part of the family and community around them. They may have full timetables and then plenty of distractions such as TV, smart phones, junk food, and an array of colourful toys. It is also hard to be a ‘normal’ kid these days. If you are judged too lively you are ‘hyperactive’, too quiet you may be ‘depressed’, a bit shy, you may be autistic. Of course kids do suffer abuse and trauma and communicate this through their behaviour, but, in many Western societies, to be a kid these days is to be closely monitored and scrutinised for your level of performance. When things are judged ‘not right’ by someone, you can then become exposed to a variety of assessments and procedures to determine what’s wrong, broken and ‘dysfunctional’ in you. There is much money to be made from identifying your ‘dysfunction’ and the marketing promise that this will lead to something (a label, a treatment) that will make things ‘better’.

Childhood depression is one of these successful modern ‘brands’ that helped monetise and arguably entrench states of alienation from self and others that arise out of both the reframing of the ‘ordinary’ struggles and sufferings that accompany growing up, and the increased gap and tension that arises in a culture that fears ‘ordinary’ intervening in children’s lives (lest it upset their autonomy) and so professionalizes this. It takes its place next to the two other successful categories of ADHD and Autism as brands with great commercial success.

The birth of scientism in childhood depression

The growth of the popularity of the concept of childhood depression, evolving from a rare to a common ‘diagnosis’ that is similar to adult depression and amenable to individualized pharmaceutical and psychological treatments, started to happen in the early 1990s and accelerated rapidly over the next decade. A shift in theory and consequently practice took place as influential academics began claiming in books and articles that childhood depression was more common than previously thought (quoting figures such as 8-20% of children and adolescents), resembled adult depression, and was amenable to treatment with antidepressants. Popular books claiming this started to appear in the 1990s, before any studies that showed benefit of ‘antidepressants’ in the under-18s were published. Thus prescriptions of drugs marketed as ‘antidepressants’ began to be made to youth, under the assumption that adolescents experience this disease called ‘depression’ in a similar way to adults and respond to the same treatments.

The widespread use in Western societies of drugs marketed as ‘antidepressants’ had begun to unfold in the late 1980s, particularly after the release of the first SSRI — Prozac — in 1987. Putting aside the poor evidential support for drugs classed as ‘antidepressant’ in general, use in young people had no evidential basis prior to its adoption as a prescription for young people in the 1990s. Previously it had been accepted that children and young people do not respond to the older generation ‘antidepressants’ (such as the Tricyclics) and so this class of drug was simply never used for that (previously) rare diagnosis of childhood depression.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s the first studies, mainly pharmaceutical industry sponsored, of antidepressants in under-18s were published. They appeared to support the new practice of using SSRIs for this age group, concluding that these drugs were safe and effective in this age group.

A classic example of how results were ‘spun’ to hide the real findings that these studies were uncovering was the study of the SSRI paroxetine (often referred to as Study 329) that was funded by SmithKline Beecham (SKB; subsequently GlaxoSmithKline, GSK) and published in 2001. The original study concluded that “Paroxetine is generally well tolerated and effective for major depression in adolescents.” In a unique subsequent re-analysis of this trial (unique because it is so rare to be able to get hold of original trial data held by drug companies), this new study using the data from the original Study 329 found that paroxetine in fact showed no efficacy for major depression in adolescents (when compared with placebo), and there was an increase in harms — the opposite of what the original Study 329 trial had reported.

This new false claim from the emerging literature then set the pattern of increasing rates of prescribing of antidepressants to under-18s that has largely continued to this day, with one important exception in these trends. In 2002 in the UK, the BBC aired a prime time documentary programme (known as ‘Panorama’) about the SSRI antidepressant ‘Seroxat’, examining the false marketing, addictive potential and the evidence suggesting that it caused increased suicidality particularly in young people. After the programme aired, the BBC received thousands of calls from viewers reporting similar reactions to that described in the programme (of agitation, aggression, and suicidal thoughts). The ensuing media coverage forced the UK Committee on Safety in Medicine (CSM) to investigate these alleged dangers. In December 2003 the UK CSM issued new guidance to UK doctors stating that SSRI antidepressants (bar one, fluoxetine) should not be prescribed to the under-18 age group, as available evidence suggested they are not effective and run the risk of serious side effects such as increased suicidality. Several reviews around that time found disturbing shortcomings in the methods and reporting of trials of these newer antidepressants in young people, and concluded that drug company supported investigators had hidden unfavourable data and exaggerated the benefits of these antidepressants and had hidden or minimised adverse effects, particularly the increased risk of suicidality.

Following the publication of the CSM guidance in the UK there was an initial impact on rates of prescribing of ‘antidepressants’ to young people, which at the time was estimated to be prescribed to about 50,000 youngsters in the UK. For a couple of years there was a dramatic decrease in the prescribing of these SSRIs to under-18s, apart from fluoxetine, the only SSRI not to be clearly contra-indicated, whose rate of prescribing remained stable. However, by 2006 in the UK, prescribing rates to under-18s for all SSRI antidepressants, except paroxetine, started recovering and have continued to gradually increase again.

In the US there was a rapid acceleration of SSRI prescriptions to under-18s from the late 1980s to 2004. Following the events in the UK that culminated in government supported advice to stop prescribing SSRIs to young people and the publications of several reviews showing a lack of efficacy and increased likelihood of experiencing adverse events such as suicidality on these medications, many other countries found themselves pushed into re-examining their practices and guidelines.

In the US warnings about safety of SSRIs in under-18s came in October 2004 when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued what is known as a ‘black box warning’ for all SSRI antidepressants prescribed to those under the age of 18 (a ‘black box warning’ denotes a ‘box’ or border around the text that appears on the package insert and signifies that medical studies indicate that the drug carries a significant risk of serious or even life-threatening adverse effects). The FDA carried out its own study of 23 trials from 9 drug companies and found an average risk of suicidality of 4% in SSRI treated under-18s, which was twice the 2% risk found in the placebo group. Unlike in the UK, studies evaluating the impact of FDA warnings on prescribing rates in the US found differences between forecasted and actual rates following the black box advisory, but what these investigations didn’t find was a significant decrease in prescription rates after the black box advisory, but rather a reduction or levelling off of the rate of prescription growth in the years immediately after the warning, with rates of prescribing increasing again after 2008.

Despite the evidence showing potential harms outweighing potential benefits in under-18s, which has not been contradicted since but rather further supported in subsequent studies, the brief period of decline or levelling off of SSRI prescriptions to the young did not persist. In fact antidepressant use in children and adolescents increased substantially between 2005 and 2012 in any Western country studied. Recent UK data has confirmed that antidepressant prescribing to young people has continued to increase in the last three years including to children 12 or younger and including the whole range of SSRI drugs.

Scientism fights back

So the story so far is that childhood depression was, until three or so decades ago, considered a rare condition likely to be related to environmental stressors and not amenable to treatment with pharmacology. Over the course of the nineties, and before evidence about the safety and efficacy was available, the newer SSRI ‘antidepressants’ began to be used, alongside a new narrative that childhood depression was common, a precursor to adult depression, hugely under-diagnosed, and that early intervention with pharmaceutical treatment was often necessary, effective and safe. Now that there was a potential for great wealth to be generated by opening up new markets for ‘antidepressants’, pharmaceutical companies began publishing studies purporting to show that the medications they made were safe and effective in this age group. The BBC Panorama documentary in 2002, UK CSM guidelines in 2003, and US FDA black box warning in 2004 all threatened to fatally dent the profiteering that could be made through marketing these drugs to minors. And for a short time they did. But scientismistic help was on the way.

Scientism 1: SSRIs work when combined with psychotherapy

One year after the CSM guidelines were made public, the Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study (TADS) was published (2004). I remember listening to the lunch time news on my car radio, following the publication of this study, as I drove between clinical commitments. I heard an ‘expert’ saying that after the guidelines the previous year telling us to be cautious about prescribing these antidepressants to young people, this groundbreaking study had shown that the best outcomes come from combining an antidepressant with psychotherapy and this is what we should now offer depressed young people. So the first rehabilitative measure came from this study which concluded, “The combination of fluoxetine with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) offered the most favourable trade-off between benefit and risk for adolescents with major depressive disorder.” The authors further conclude that despite calls to restrict access to antidepressant medications, medical management of major depressive disorder in young people with fluoxetine should be made widely available, not discouraged. Indeed it is this study that has been particularly influential in maintaining the idea that fluoxetine is the one SSRI that has been found to be ‘effective’.

TADS was a large multi-centre Randomised Control Trail that randomised the adolescent participants diagnosed with ‘Major Depressive Disorder’ to four treatment arms: 1. SSRI antidepressant (fluoxetine) only, 2. Placebo only, 3. CBT only, 4. fluoxetine plus CBT. The first and most obvious problem comes from the study methodology. Comparing results across all four groups is misleading as some patients knew they were having an active treatment and others didn’t. Essentially TADS is really two separate randomised studies: a double blind comparison of fluoxetine (109 subjects) with placebo (112) — as these subjects did not know whether or not they were getting the active treatment — and an un-blinded comparison between CBT alone (111) and fluoxetine plus CBT (107), as these subjects knew they were receiving one active treatment in the CBT alone group and two active treatments in the CBT plus fluoxetine group. This latter group therefore received more face to face contact and knew (as did their doctors) that they were not receiving placebo. The reason the authors gave for not including a placebo plus CBT group is that they used a placebo group to get a ‘baseline’ to compare the other treatment groups against. This is not convincing. Most likely the authors knew that having ‘more’ treatment in a treatment study is likely to enhance any placebo effects and therefore skew findings towards more positive outcomes for the group having two active treatments, known to the participants.

Not mentioned in the abstract is that TADS found no statistical advantage of fluoxetine over placebo on the primary end point, the Children’s Depression Rating Scale. This and the small or absent advantage of fluoxetine on other end points suggests that the only legitimate conclusion that can be made from this study, as far as efficacy of fluoxetine in childhood depression is concerned, is that it is no more effective than placebo.

So much for antidepressant efficacy in TADS. What about adverse events? Well significantly more psychiatric adverse events occurred in the fluoxetine group than the placebo group. Despite small numbers and the exclusion of known suicidal behaviour, TADS still found a trend to more suicidal behaviour in those taking fluoxetine (15 v 9, taking fluoxetine v not taking fluoxetine), which is consistent with other trials of SSRIs. So as with other more objective analysis of SSRIs effects in childhood depression (such as the re-analysis of Study 329 discussed above), the relevant data from TADS shows fluoxetine to be as effective as placebo but produces more adverse events including a greater tendency to suicidal behaviours.

I’m sure readers won’t be surprised to hear that although TADS was funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health, many of the authors disclosed ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including Professor Graham Emslie, who had extensive ties to the pharmaceutical industry and was lead investigator in the first two studies for fluoxetine in childhood depression.

Scientism 2: The black box warning has led to increased suicide rates in young people

In 2007, another highly publicised paper was published. The authors examined U.S. and Dutch data on prescription rates for SSRIs up to 2005 in children and adolescents, and suicide rates for children and adolescents (through to 2004 in the United States and through to 2005 in the Netherlands); in order to determine whether there was an association between antidepressant prescription rates and suicide rates during the periods preceding and immediately following the 2004 FDA black box warnings. As reported in mainstream news media, the authors concluded that SSRI prescriptions for youths had decreased in both the United States and the Netherlands after the FDA warnings were issued and that subsequently youth suicide rates increased. They concluded that because of the FDA black box warning, a decrease in prescribing of SSRI antidepressants to the young had happened and this had likely caused an increase in suicide rates due to larger numbers of youth not being effectively treated.

This article is a quite straightforward attempt at deception. It beggars belief that it got through the peer review process and was published, with its message that the warning has led to more suicides in young people, in a leading psychiatric journal (American Journal of Psychiatry). The most glaring deceit is in the presentation of data shown on the graphs depicting prescribing and suicide rates respectively. In fact if you look at the graphs carefully you will see that in the year in which suicide rates rose, there was no significant drop in SSRI prescribing. Their graphs for US prescribing rates show no significant decrease in antidepressant prescribing for 2004, but a 17% increase in suicides amongst the young that year (compared to 2003). The graphs show the alleged decrease in prescribing took place in 2005 (not 2004). The argument that there were decreasing rates of antidepressant prescription following the FDA warnings are based on the 2005 prescription levels (compared with 2003); however, figures for 2005 suicides were not available at the time the paper was written and therefore do not appear. This means the paper’s main conclusion is based on using the decrease in 2005 prescribing rates and linking this to the increased suicide rate found in 2004. In fact when suicide figures were available, they showed a decrease in the suicide rate in 2005 (compared to 2004) and suicide rates hit an all-time low for the US in 2007, a point in time that clearly follows the alleged decrease in prescribing (however, as I argue below this does not imply any causation, simply that the association they tried to claim in their paper does not stand up to proper scrutiny).

The graphs on the Netherlands are mixed, show no recognisable pattern, and are based on very small numbers. For example, 2002 shows a 25% increase in suicides compared with 2001, yet it was also the year with their highest rates of prescribing of antidepressants for children and adolescents. At least for the Netherlands data the authors do compare the correct year of prescribing rate with numbers of suicide, but it seems an arbitrary conclusion to just pick out the decrease in prescribing rates (between 2003 and 2005) and a smaller increase in suicide rates (than for example in 2002) in 2004 and 2005 compared to 2003. This article prompted a complaint by psychiatrists from the Netherlands about the misrepresentation of the Dutch data. The use of Dutch data also raises questions as to why, out of all the other countries they could have had access to prescribing and suicide rate data, they chose the Netherlands. Presumably, they needed to search for a country where they could try and extract data that somehow matched their narrative.

Predictably, when you look at the conflicts of interest statement, several of the authors, including the lead author, disclose conflicts of interest related to financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry.

Scientism 3: If we stop prescribing antidepressants youth are more likely to self-harm

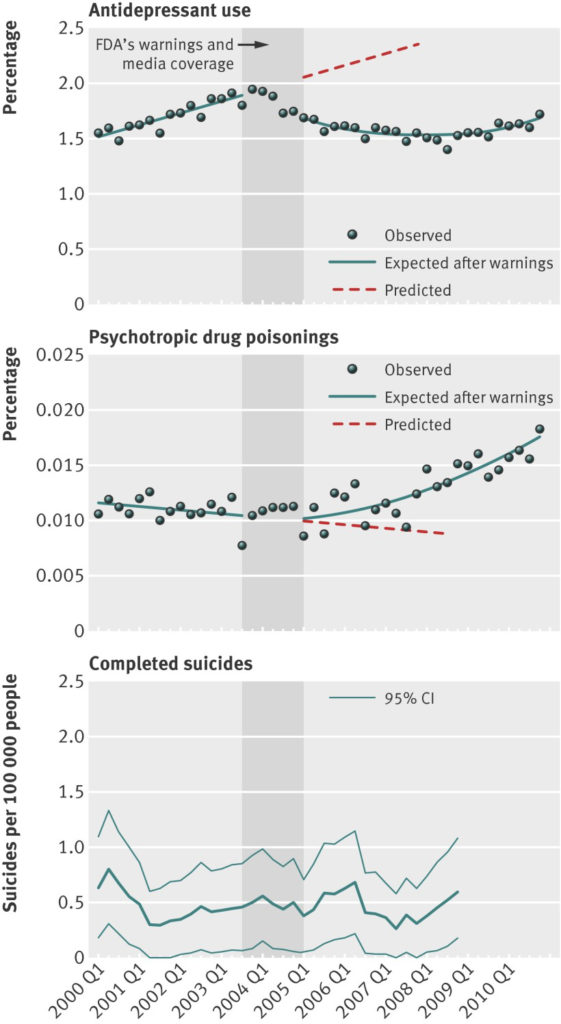

In 2014 a paper in the British Medical Journal claimed that there were significant increases in self harm through drug poisonings (overdoses) in adolescents in the years following the FDA black box warning and concluded that safety warnings about antidepressants and widespread media coverage led to decreased antidepressant use resulting in increases in suicide attempts (self-harm) among young people. This paper was accompanied by an editorial, which, using this study, argued that this was an example of how warnings about adverse effects of medicines can lead to under-treatment and consequently even worse adverse effects. A full 10 years after the black box warning, these arguments were still being put forward in major medical journals and garnering significant press attention.

The study design was described by the authors as ‘quasi-experimental’, examining trends in rates of antidepressant dispensing, psychotropic drug poisonings, and completed suicides.

The methodology is so bizarre that I have found myself re-reading this paper several times in disbelief. The authors are attempting to show that overdosing with psychotropic drugs is increasing because doctors are prescribing less psychotropic drugs. They use ‘psychotropic drug poisoning’ as their proxy measure for “suicidal behaviour” (which is the term that appears in the title). This is the relevant methodology statement:

“While encounters for suicide attempts can be identified in administrative databases using external cause of injury codes (E-codes), they are known to be incompletely captured in commercial plan databases. Our preliminary analysis found that E-code completeness varied across study sites, treatment settings, and years. Therefore, instead of deliberate self harm E-codes, we used poisoning by psychotropic agents (international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9) code 969)”

These are the drugs that are coded under ICD9-969, Poisoning by psychotropic agents: antidepressants, phenothiazine-based tranquilizers, butyrophenone-based tranquilizers, other antipsychotics, neuroleptics and major tranquilizers, benzodiazepine-based tranquilizers, other tranquilizers, psychodysleptics (hallucinogens), psychostimulants, unspecified psychotropic agent.

So realistically out of that list the only two that are relevant, in that appreciable numbers of adolescents may be prescribed them, are antidepressants and psychostimulants. Psychostimulants ought to be controlled for as they can cause suicidal impulses too and so if poisoning by psychostimulants is to be used in this context we need to see figures for psychostimulant prescriptions. Furthermore, psychostimulants are not a recognised treatment for depression and therefore psychostimulant overdoses could not be used as a proxy for untreated depression. This leaves antidepressants; so essentially this study is arguing that a consequence of warnings about prescribing antidepressants to adolescents is that fewer adolescents are being treated with antidepressants, which is therefore leading to more adolescents taking an overdose with antidepressants. What sort of voodoo science is this, I ask?

Leaving aside the obvious scientific mistake of assuming correlation equates with causation (i.e. the mistake of thinking that because reduced prescribing is associated with increased overdoses that one causes the other), this study is also another example of straightforward deception.

Below are the graphs for adolescents associated with the claim (reproduced from here):

Look in particular at the lines of best fit the authors have chosen for the second graph (rates of psychotropic poisonings). Look again. What do you think of their line of best fit? Are they drawn to fit their hypothesis or the data? Their line of best fit starts to increase after 2005, however, looking at their scatter diagram this does not fit with the data they present. In their diagram, rates of self-poisoning continue to vary by site around a mean that largely stays static until 2007, after which rates start to noticeably increase from 2008 onwards, when coincidently, according to their first graph, rates of antidepressant prescribing also start increasing again, but of course this association (increasing rates of antidepressant prescribing at the same time as psychotropic poisonings increasing) should not be read as causative. Looking at the third graph you can see that rates of adolescent suicide vary around a mean between 2001 and 2007 (when they hit an all-time low) and also start rising in 2008.

A more obvious association that may have some causal connection is that the rates of self-poisoning in adolescents, that actually start increasing significantly after 2008, are at a time when the financial crash happens and families and the society around them come under greater stress. But heaven forbid we take a context-rich view that perhaps depression and self-harm might be a reflection of real life events and their consequences. So another unchallenged assumption behind this and the other scientism articles I’ve discussed (that are maybe better thought of simply as ‘junk pseudo-science’) is that what is called ‘depression’ and the related self-harm is a medical disease that afflicts the inner spaces of an individual, who is thus ‘broken’ and ‘dysfunctional’ (for example, due to a chemical imbalance), and by not ‘treating’ these broken individuals with pharmaceuticals we let them become more ill.

Resist the psychiatrization of growing up

This is the kind of irrational delusion we have created through the belief that we have diagnoses in psychiatry that have explanatory capabilities. I believe the spread of this type of psychiatrization and McDonaldisation of the pain and struggles involved in growing up and the insecurities created by neo-liberal marketization has caused considerably more harm to young people than good. I believe the science is on my side in this conclusion. As I have shown above, there is plenty of junk pseudo-science scientism propping up the other side of the argument.

so what should we do about very unhappy kids…

Report comment

Very Unhappy Kids do not exist in a vacuum. Social services and counseling that addresses the parents emotional and socioeconomic issues are far more likely to help long term.

Report comment

how about nutrition and mental health for kids

Report comment

Kids eat what their parents provide. Nutrition counseling for parents and financial support to purchase wholesome foods would be great. And mental health for kids? That’s far too broad to have any meaning. If you want to help kids, address the parents emotional functioning and communication skills, address any financial shortfalls preventing proper care, address any issues with social functioning. You’ve heard of the poem ‘Children Learn What They Live’? It’s one of the most accurate and poignant descriptions of the children’s outcomes every written in so few words and yet people still don’t seem to get it. Kids are products of their environments, plain and simple. They aren’t machines that come precoded for certain outcomes. Kids require a massive amount of input and behavior shaping. It’s almost ridiculous that this is completely accepted in animal training and yet we act like kids can simply raise themselves and any failure on the part of the child to do that is a sign of illness.

Report comment

Thanks Kindred for the poem reference. It is worth a read and maybe a mailing to professionals and government officials.

Marian Wright Elderman if the Children’s Defense Fund has several books one with another poem.

The first child abuse prosecuted was in NYC two centuries ago and they had to use an Animal Rights Law.

There are so many threads here. The complete and utter lack of trading in Child Development to all or many professionals who work with children.

Michael Harrington’s The Other America is also a must read though old.

Jean Vanier and his L’Arche Communities not close to this but helpful to know about.

Every child is unique and deserves not only a safe place at home and school but also the opportunity to thrive with environmental and economic equality.

Read Octavia Butler’s bio. What she could have achieved with equal supports. And yes she was depressed but who eouldn’t be in society as she was asso many of us are or were?

Sen. John McCain in the other side of politics for me did send the first National Geographic magazine that featured Climate Change to all members of Congress with another official.

We need to do more of this.

Report comment

Littleturtle

Why would you even consider exposing children to “mental health” and all the snake oil shenanigans of the “mental health” system? If anything we must keep our children free from the “mental health” system at all costs. It has nothing of value to give to children, period. To willingly take your children and hand them over to “mental health” is the same as selling them into slavery for the rest of their lives.

Report comment

I am using the words mental health in an

individual way…not the system…the system is sick…

I am talking about the part that is not…

like nutrition…

Report comment

Slavery, I think, is a few degrees more serious than this. It doesn’t come across as helpful, in my opinion, to make such extreme comparisons.

Report comment

I also hear from people who post blogs here comparing being forcibly injected with haldol to being physically raped. If you want to be taken seriously, you have to let go of these sorts of comparisons. If you don’t, no one will take you seriously.

Here is a simple question: If you are acting out of control and brought into the emergency, what do you expect them to do? You may not like it, but their going to pull down your trousers and inject you. It’s not the same as being raped.

Report comment

I have heard many people make this exact comparison, including people who have experienced both. Are you suggesting that the people in the hospital ER have no other option besides Haldol injections, or that we ought to be well informed enough to know this and therefore avoid getting taken to the ER?

Report comment

Despondent, I’m sorry you can’t see the connection between forcible rape and forcible injection with medication. Both involve violating the bodily integrity of another against their will. How is this a hard concept to grasp? As someone who was violently raped, the analogy works for me.

Report comment

@kindredspirit I do understand the analogy. I’ve been injected with haldol a few times after being taken to hospital. I understood at the time that if I was going to resist, they would have to hold me down. It’s just one injection, the effects wear off within a day. The hospital staff giving the injection are not rapists. They would rather not have to deal with it at all.

Report comment

@kindredspirit My problem is with the psychiatrist, who convinces you that there is no cure for what you have, and proceeds to drug you day after day …

Report comment

@kindredspirit People have to learn to be more careful with their wording.

Report comment

despondent,

As to “I also hear from people who post blogs here comparing being forcibly injected with haldol to being physically raped. If you want to be taken seriously, you have to let go of these sorts of comparisons.”

As one who has experienced both rape, and being forcibly injected with antipsychotics, the latter is infinitely worse. Not just because being penetrated against your will, in any manner, is morally repugnant. Which it is.

But the psychiatrists who do this, also label you with their made up DSM disorders, that they fraudulently claim are “lifelong, incurable, genetic diseases.” And they try to defame you to every doctor you will ever deal with, and every insurance company in this country. Who then claim you no longer have a right to even purchase health insurance, due to your bogus “pre-existing condition.”

At least the young man who raped me, apologized afterword, said he couldn’t help himself, and did not try to harm me for the rest of my life.

Do you see why psychiatric rape with a needle, and the subsequent, systemic, psychiatric DSM defamation crimes against a person, are infinitely worse than even rape by a man yet?

Report comment

@Someone Else Maybe you didn’t understand what I was trying to say. I’m talking about the one-time injection a person is given to calm him / her down when in the ER (in my case, there were only a nurse and a few orderly’s hovering over me). Not the institution of psychiatry. There I would agree with you. But that’s much more subtle and does a lot more harm.

Report comment

@Steve McCrea I’m not saying either. I’m saying the comparison just feeds the “beast”.

Report comment

@Steve McCrea I think I need to clarify a little more:

You can see the same type of rhetoric from the other side. “These people need to be on antipsychotics for the rest of their lives, their unpredictable and could be a danger to themselves or others if not medicated”.

The discussion on long term use of antipsychotics would be mute if the supersensitivity hypothesis was proven.

Report comment

I agree. Most of the “data” in support of long-term antipsychotic use is based on withdrawal studies, which completely fail to take supersensitivity and withdrawal effects into accounts (primarily because they want to pretend that such effects don’t actually exist). It’s pretty warped!

Report comment

“…Even day-to-day language seems colonized by medical terminology with youngsters describing their feelings using clinical (“I feel depressed”) as opposed to more ordinary language (“I feel unhappy/sad/miserable”)….”

The LINK below is a good example of this type of Brainwashing:

https://youtu.be/HOiGm-X8cak

The drug damage is also easy to see.

Report comment

Despondent, Haldol WOULD wear off. But they never let it! And they blame all the seizures/eye rollings/Parkinson/etc. on lucky you. Or your Mental Illness which is in fact the Real You forever after.

Report comment

We should start by listening to them. Children are the most disempowered group in the world. The odds are tremendous that their feelings of hopelessness have to do with being in a hopeless situation that they are unable to fix or escape.

Report comment

Thank you for this excellent article; consistently, I worry about “autism” when addressing the harm of pathologizing childhood. The statistics on “autism” are tragic (from 1:2000 in 1990 to 1:59 in 2018); “autism” is a childhood health epidemic of historic proportion.

Report comment

what is causing this..

Report comment

I believe that an increase in cultural stress on children to “achieve” is a large part of the problem. This is harmful to childhood development especially when any faltering from childhood “success” is widely pathologized.

Pediatricians discount the epidemic because anti-vaxers have tied the increase to vaccines and are thereby causing a different childhood health problem of distrust of vaccines. This sad situation reminds me of Antipsychiatry discounted because people want to associate it with Scientology.

Report comment

A lot of men carry their cellphones in their front trouser pockets. The increased radiation could effect sperm and dna. Just a thought.

Report comment

SSRIs are associated with an increase in behavior that gets labeled “autistic.” Massive increases in SSRI use by pregnant women may be a contributing factor.

Report comment

The big increase in SSRIs came before the big increase in “Autism Spectrum”.

Report comment

“Pediatricians discount the epidemic because anti-vaxers have tied the increase to vaccines”. That sounds very far fetched to me. More than a 60 fold increase since 1990 and pediatricians say it’s a conspiracy from the anti-vax community?

I would seriously look into the negative effects of EMF radiation from WiFi, Cell Phones and bluetooth devices. The rise in 1990 of autism coincides nicely with the rise in cell phone use and other wireless technology.

Here’s the first article that comes up on a Google search for prenatal exposure to emf radiation:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3302692/

Report comment

Here’s a video of early signs of autism:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7NeBs5wNOA

Do you really believe this is due to “an increase in cultural stress on children to “achieve”” Or is it more likely a neuro-developmental problem. Possibly caused by something that has changed in the environment.

Report comment

Specifically, I do not know what caused the behaviors expressed in the video referenced above but I believe that these types of behaviors generally express environmental stress (“an increase in cultural stress on children to ‘achieve’”). I believe that this is a “neuro-developmental” problem caused by an environmental change to a more stressful culture for children. I do not believe that radiation from modern technology can account for the epidemic. BTW, I have not heard of references to an increase in “autism” greater than 30-fold (which is a staggering figure).

Report comment

Steve, do you think too much screen time may also play a role? Have you read The Plug In Drug by Marie Winn?

Report comment

@Steve Spiegel Why do you believe radiation is not a factor? How does a toddler experience this cultural stress?

Yes, you are correct, I made an error when dividing 2000 by 59. But you knew that already. It’s interesting you would mention it.

Report comment

Toddlers predominately learn stress from their parents; I contend that cultural stress is causing parents increasing stress that is problematic (confusing/distracting/distressful) for childhood development.

There is no general consensus about the statistics for “autism”; general confusion about the statistics prompted my questioning your figure (I was not mocking a math error). The baseline for my statistics comes from scientific research during 1980-2000; the CDC now rejects all statistics before 2000 as under-reported, but I do not. The CDC started over about 2000 with a much higher figure of 1:400-800 “based on better accounting” of the newly defined “spectrum.” Thereafter the CDC claimed better accounting for a 1:170 statistic until better accounting now promotes the 1:59 figure. The CDC claims no significant increase in “autism” while I claim that their own statistics since 2000 describe an epidemic. I do not know the real statistics (as if that is possible) but I did not want to let a “60-fold increase” pass unchallenged when I was defensive about my statistics of a 30-fold increase.

Report comment

The problem with autism is that no one sees the psychological need of autism in reality destroyed by hegemony of apollonian ego. Thank you. If no one is to build up the background of the psychological realm and psychological hierarchy, those kids will remain seen as impaired rather that higly psychological. Those kids are and will be the main reason of psychological socialism. As they represent the highest archetype in psychological hierarchy. Their non ability to cope with this higly psychopatic and materialistic reality by themselves, is the step further to the psychological state, Scientists were supposed to serve THE OTHER ARCHETYPES, not to terrorize and abuse the psyche. And they will be.

ADULTS WERE SUPPOSED TO SERVE AND THEY ARE MAKING FUN OF THE PSYCHE, YOU AUTHORITARIAN SHITS. YOU KILLED AND SOLD SACREDNESS. YOU WILL PAY FOR SELLING THE PSYCHE TO PSYCHOPATS.

James Hillman Re -Visionning psychology.

Shalom to you autistics children or Aspargers or whoever with diagnose from beyond apollonian ego fundamentalism. Shalom from the future system. To you TITANS.

Shalom my gods.

HAVE YOU SEEN THE GREAT MOVIE ABOUT MONKEYS MORE HUMAN THAN PEOPLE? THE MONKEYS ARE THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PEOPLE, MORE HUMAN THAN HUMANS.

Report comment

Shalom sweetheart.

Report comment

Titan means titanic psychological work if you still don’t know. Is a FORM OF SOPHISTOCATED work. THE PSYCHOLOGICAL WORK. I do not care if authoritarians have objections. I spit on your graves psychological communnists, capitalists and so on THE SAME WAY YOU ARE SPITTING ON THE PSYCHOLOGICAL REALITY.

You, authoritarians, you will serve to psyche one day, It is a promise.

Report comment

INDOLENCE IN THINKING IS KILLING THOSE KIDS, because THE MORE IMPORTANT HUMAN KNOWLEDGE WAS DESTROYED BY SCIENTISTS.(HILLMAN)

AND YOU HAVE NO RESPECT TOWARD THE STRICT PSYCHOLOGICAL REALITY WHICH HAS NOTHING IN COMMON WITH APOLLONIAN EGO.

APOLLONIAN EGO IS THE SIMPLE FLESH REALITY

AND HADES REALITY HAVE NO MATERIAL BODY, EVEN THOUGH PEOPLE HAVE. THEY ARE IN THAT PSYCHOLOGICAL REALITY, NOT IN THE MATERIAL REALITY in the body- THIS IS AUTISM. This is not the impairement, this is beyond everything you know, and you will ever know about psychological reality. Those kids are the property of the PSYCHE, not of the authoritarians. I see them as more important.

Report comment

As gods themselves.

Report comment

Danzig666, my condolences on what you have suffered. 🙁

May you find your Peace soon.

Report comment

It’s interesting to see the devices psychiatry uses to defray attention away the lack of efficacy and safety.

1. The Water Muddying Strategy (also known as the Bundling Strategy). We know the drugs useless but it works in combination with therapy, such a fortuitous combo. So if we provide therapy can we please drug them as well.

2 and 3. The No Way Out strategy. It seems we can’t find any efficacy over placebo, but for god’s sake don’t stop taking the tablets because bad stuff happens, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Prof Pariante and co are endlessly inventive and have further strategies

4. The “it must work for someone” strategy. If there is a bell curve for response , then surely their is a subgroup who respond well, do let us experiment to see if you are in that group. But don’t mention placebo, which had almost the same response curve…..

5. The “it must improve something” strategy. Look, item x.x of the blah scale showed an improvement, can we retrospectively look at that instead of the pesky primary outcome which showed no effect.

6. The Black Is White strategy. Surprisingly effective, most people are too busy gasping for air so it passes unnoticed. Try Pariante’s “all the studies prove antidepressants reduce suicide” or Prof David Taylor’s “much better than placebo”. Important: you do not need any data to back up your claim, it’s just a distraction.

7. The My Clinical Experience strategy. This again requires no data and the key is to elevate your day to day drug pushing to the the wisdom of Solomon. No-one will challenge you.

8. The “the products useless but look at the extras” strategy. The drug doesn’t do what it’s supposed to, but has a rather intriguing side effect like “mood lift”, or “helps you sleep (all the time)”. You are looking like you could use a few pounds anyway.

Report comment

I would rather take Valium, Morphine, or some other pain killer/tranquilizer for my sorrows than the crap they misleadingly dubbed “antidepressants.”

Report comment

Even more interesting is the psychiatric fury that arises when treatments for such conditions arise that are actually effective, such as dietary/nutrient based actions that use no pharmaceutical agents. The practitioners of such methods are regarded as agents of the Devil, dedicated to restoring medieval superstitions, in addition to condemning such valuable drugs as antidepressants.

Report comment

yes yes yes….nutrition…duh

Report comment

Thank you Sami for this comprehensive article about the darkness of psychiatry, the mental health profession, and modern society.

While Bob Whitaker and Lisa Cosgrove (in Psychiatry Under the Influence) were correct to call psychiatry “institutionally corrupt,” psychiatry is horrifically guilty of “institutional child abuse.”

While the Catholic Church covered up the child abuse of many within the Church, psychiatry — in Orwellian fashion — has convinced society that its abuse of children is “treatment.”

The abuse includes, on the most obvious level, ineffective and dangerous drugs which, also in Orwellian fashion, are called “medication.” But the abuse does not end there. The abuse is about exploiting family and society tensions caused by normal child behavior so as to institutionally expand and profit. And, perhaps worst of all, the abuse is about psychiatry convincing a child, their family, and society that children who create any tension are defective when they are just being human.

Institutional psychiatry, like make other abusive institutions, has leveled “career violence” at its critics. This violence can be especially ugly for the handful of critics who are psychiatrists. So thank you Sami for being unintimidated. From my experience, the vast majority of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals do everything possible to stay in complete denial of this institutional abuse or, when the abuse is so obvious that it is impossible to deny, are cowards about challenging it — Bruce

Report comment

I absolutely agree, “psychiatry is horrifically guilty of ‘institutional child abuse.’”

“While the Catholic Church covered up the child abuse of many within the Church, psychiatry — in Orwellian fashion — has convinced society that its abuse of children is ‘treatment.’”

Psychiatry, in reality, convinced all the mainstream, paternalistic Protestant Christian religions, but also the Catholics, to buy into their child abuse covering up “treatment” system long ago. This is actually known as “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions,” according to an ethical pastor of mine.

And the primary actual function of today’s “mental health professionals” is covering up child abuse, even according to their own medical literature. This covering up of child abuse by today’s “mental health professions” needs to stop.

Today, over 80% of those fraudulently defamed with the “affective and psychotic disorders” (“depression,”

“anxiety,” “bipolar,” and “schizophrenic”) are actually misdiagnosed child abuse victims. Over 90% of those labeled as “borderline” are misdiagnosed child abuse victims.”

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

Why all this misdiagnosis of child abuse survivors? Helping child abuse survivors is NOT a billable DSM disorder. So ALL child abuse survivors MUST be MISDIAGNOSED, if the “mental health professional” wants to get paid. And they all do.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Today’s so called “mental health industry” is actually functioning for the religions and wealthy child molesters, as a multibillion dollar, primarily child abuse covering up, system. I hope today’s “mental health professionals” will rethink the wisdom of functioning as nothing more than pedophile profiteers for today’s satanic, fiscally irresponsible, war mongering and profiteering, globalist so called “elite.”

Report comment

critical psychiatry will be very effective…

anti-psychiatry may make things worse…

what works the best…

Report comment

There will be no psychiatry without psyche. There is no finger without the rest of the hand and the body. The finger without THE VISION OF THE REST OF the body means nothing.

Report comment

You often repeat this. I’m not sure what you mean. Why is “antipsychiatry” going to make things worse?

Report comment

very obvious…a frontal assault against the guys with power

is not wise….it is best to work at the bottom…get ordinary

people helping…and don’t go with hatred…go also with critical psychiatry..

anti-psychiatry trys to take everything down…does that make sense steve..

Report comment

From one point of view, it does make sense. I guess the question people struggle with is whether a real change in how things are done can be accomplished without challenging the “guys with power.” I think on an individual level, your approach is probably very wise. However, it seems unlikely that the people making so much money on this racket are going to give up their power without a fight. So if enough people get together, maybe it DOES make sense to take on the “big guns.” Hope that makes some sense!

Report comment

you have to take on the big guns…

but take down only what needs to go…

my psychiatrist does not need to be taken down…

my psychologist does not need to be taken down..

and people are people…they want pills…

and they want a quick fix….a pill…and

the doctor is there…

Report comment

Littleturtle, people want a quick fix because they’ve been culturally programmed to believe that quick fixes exist in the first place.

Report comment

Who’s talking full frontal assault? I prefer guerrilla warfare with anonymous blogs, memes, etc. Check out Auntie Psychiatry’s blog sometime.

Report comment

Now psychiatrists are experimenting with ketamine on children

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-6020211/Scientists-test-ketamine-CHILDREN-depression.html

“What’s more, it works much faster than SSRIs, and appears to last longer to move congestion in the brain that may be hampering the patient’s freedom of thought and feeling. It’s widely agreed that patients with depression appear to have dampened connections between certain neurons, caused by a build-up of proteins on top of cell membranes. In healthy brains, cell membranes are free and open to receive signals. In patients with depression, an overwhelming amount of G proteins pile up on top of lipid rafts – kind of like lids which sit on top of cell membranes.”

So now we know.

Report comment

Ofcourse they are ‘treatment resistant’ Adults who are ‘treatment resistant’ get ‘augmentaion treatment’ an SSRI plus an ‘antipsychotic’ another brilliant marketing tool: ‘treatment resistant’

Then at the end you have the expert validating the BS.

Report comment

Yeah, how do they get away with that? Not, “I wasn’t able to help you” or “I haven’t been able to figure out what you need” or even “We seemed to be unable to connect,” but instead, “You have ‘treatment resistant depression?'” What a freakin’ cop out!

Report comment

“Always blame the patient” is their mantra.

Report comment

If you want a healthy brain steer clear of “mental health.”

Report comment

Well hmm Bramble.

My child can’t be treated with chemo if no cancer is found. My child can also not be treated with chemo if they do not have a test for cancer.

My child cannot be treated with a drug, unless their “coated neurons” are shown, unless their “dampened connections” are shown, unless their “imbalance is verified”.

“depression” responds to change in environment. Disease does not. If depression did not respond to environment, they would NEVER EVER try ketamine. Ketamine changes your environment.

Except, a child can NEVER report on how weird their brain feels on meds or without. They exhibit behaviour and adults interpret it to mean something. Take that child out for 4 solid weeks and play, read, have fun and VOILA, a change.

Same with adults.

Psychiatry is based on the fact that most people are either vulnerable or inexperienced. Enlightenment comes with age and experience.

Thank god psychiatry lets a few of us live on with some heavily coated neurons, to be able to form independent thought.

LOL, they get pretty miserable when confronted. Nothing like getting a shrink angry, or should I say angrier.

Ever seen the true nature that is behind the façade? More and more it is evident. Years ago, they were much more proud of their occupations.

Why dig the grave deeper by using kids for differentiating, and drugging.

Shows just how adults are starting to get suspicious.

Physical pain does not indicate cancer, or arthritis.

Report comment

All I want to say about this article is that the publicity shot depicting an unhappy/sad/miserable child is the best I’ve ever seen.

Report comment

Sammi thank you so much for this article. I really enjoyed the read and agree with the perspective

Report comment

This generation of drugged children who had no informed consent in their abuse will be even more angry than us lot, who naively walked into their GP’s room and had their lives ruined and hence discovered a history hell hole of medical abuse, violence and death ongoing in a more subtle and defused – by a mountain of nonsense (method used in financial fraud) – but none the less, invidious, insidious, deadly way.

https://youtu.be/7uVhy9JItZI?t=453

“I can’t answer such a vague question”

Report comment

This generation of drugged children will be lucky if they have enough of their marbles left once they reach adulthood to even question their captors, much less rebel against them.

Report comment

Meanwhile on planet ‘guardian’

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/aug/03/uk-children-adhd-wait-two-years-diagnosis-experts

Oh yes Ilina Singh shows us how they are reframing – ‘Boys in particular were often labelled as the naughty children and that then stigmatised the family’ – the reason to implement financially incentivised drugging :

“In the Voices project, they found that “particularly parents who were in low resource settings were often afraid to go and talk to the school. Boys in particular were often labelled as the naughty children and that then stigmatised the family and so there was this disconnect between the family and the school,” she said.”

Report comment

I can take what the Daily Mail says about lids on cell membranes with a pinch of salt but I actually found the Guardian article quite seductive.

Report comment

@littleturtle

There’s an interesting argument developing here about whether you should be tactically anti psychiatry or critical psychiatry.

I say be guided by the evidence, and if it leads in the direction of psychiatry being unreformable, then your position must be anti.

I am clinging to the critical wagon, but I do want people taken down, even though I personally liked them. These people lied to patients. So the psychologist that said “20 mg olanzapine is a small dose (it’s the max) – not an innocent mistake, should be called to account. The psychiatrist that didn’t know sertraline wasn’t licensed for depression in children let alone suicidal children – should be called to account. 2 psychiatrists that said it’s a chemical imbalance – stop practising until you learn and speak the truth.

I think there are decent people who have been simply following orders , but at great cost to patients. In your language , I want them taken down.

Report comment

I don’t think there is any propect of accountability for harmful practitioners, even if psychiatry was dismantled. The complete lack of any genuine accountability is a big part of the problem.

I agree there are good people within the system, people who are trying to help and to minimise the harm the system causes from within that system. I don’t know how they can cope without being dragged under themelves.

The thing is, I don’t know how the system can possibly be reformed. It was born as an alternate prison system for unwanted people. Mental hospitals incarcerated not just the ‘mad’, but those considered intellectually subnormal, children with disabilities (they seldom, if ever, survived into adulthood) errant teenagers, unwanted wives, those prone to epileptic fits, gay people etc., The purpose was part eugenics, part social control and enforcement of ‘normality” and hierarchy, and part concern to ‘unburden’ the respectable, and families.

The legacy of managing the problem of people believed to be inherently defective and subhuman, people society didn’t want, has never left, imo. It is a culture that is passed down. Labels, language and fashions have changed, attitudes have been modified towards faux benevolence, drugs have replaced chains and reduced numbers inside, there is a greater pretence at the trappings of medicine, but at heart this is the system.

How can we change this into something else?

Report comment

out says: “How can we change this into something else?”

My conversion to anti-psychiatry happened gradually, but it was Phil Hickey writing here on MiA who finally persuaded me that Psychiatry is a hoax. And how is it possible to change a hoax into something else?

ConcernedCarer says: “There’s an interesting argument developing here about whether you should be tactically anti psychiatry or critical psychiatry.”

The lively debate around the distinction between critical psychiatry and anti-psychiatry has been running here on MiA for several years, but guild Psychiatry does not concern itself with such niceties. Vocal senior psychiatrists such as Lieberman, Wessely and Pies have weaponized the word “anti-psychiatry” via blogs, social media and mainstream media to make sure everyone understands that anti-psychiatry = anti-science, flaky, bizarre, deviant. Then they can (and do) target anyone they perceive as a threat with the dreaded “anti-psychiatry” slur, and they have an army of dutiful medics, academics and journalists to assist. That is why I decided to embrace and reclaim the word anti-psychiatry – it has been a very liberating move!

Report comment

We all come at this from slightly different places. I have no doubt that every psychiatric treatment there has ever been is bullshit. My problem, Auntie, is that I can’t help my loved one if I’m anti psychiatry – I’m just ruled offside , not to be involved. If I’m critical (and I am a handful in the psych’s office), I can make a difference here and now.

Report comment

@ConcernedCarer: You are right to be cautious. Auntie Psychiatry is my campaigning alter ego through which I can give full vent to my anti-psychiatry feelings. In front of a member of the Mental Health team I am always meek and acquiescent – it is very dangerous to express any dissent at all, let alone let slip that I am anti-psychiatry. If you feel that you can be critical in the psych’s office, then you are doing a lot better than me, but please have your wits about you – things can turn very quickly if you push things too far.

Report comment

It’s like Clockwork on my Records:- when I express truthful disadvantages within “Mental Health” treatment, insinuations of Mental Unwellness have followed.

There are two World Class Eye Hospitals in Central London. At both of these hospitals when I have expressed negative eyesight effects as a result of historical psychotropic consumption, doctors at both of these hospitals have kept what I’ve expressed off the records, and represented me in negative mental health terms instead…

….Even though the negative Psychotropic eye effects expressed by me, are acknowledged to exist by the drug manufacturers themselves on their Drug Information Sheets.

I would imagine that if a doctor were to represent a person truthfully in this regard on their records, that they would not last long at either of these Top Hospitals.

To work in medicine at this level a doctor would have to be corrupt.

Report comment

Right you are! “Antipsychiatry” has been rebranded by the psychiatric profession as “anti-science,” which ironically and subtly supports the idea that psychiatry is somehow scientific despite it’s own admission that not one of its diagnoses can be objectively distinguished from another diagnosis or from “normal” (the admission is right in the intro to the DSM!)

Report comment

This is something that a TON of people miss. You are a smart fox.

The rewording is never missed by me and it comes in so many forms.

Report comment

Devouring more and more souls–especially young ones. Psychiatry is the Minotaur lurking in the labyrinth which is our twisted culture.

This monster must be stopped!

Report comment

“Decent people following orders” is the core of why the system doesn’t collapse of its own weight. If these “decent people” followed their instincts, there would be a huge uprising against the system as it is. I am not saying it is easy to resist, as I was an “insider” for many years and found that resistance to the status quo was punished in various ways, from ridicule to ignoring to dismissing me as “one of those anti-med guys.” I had very little support from colleagues, even though behind the scenes I found that many agreed with my basic principles. It’s scary to stand up, but if you don’t, it’s tacit approval of the system. That’s why I eventually got out of the “mental health” world and into advocacy. I could no longer deal with the moral compromises I needed to make to stay in there, even though the ones who managed to see me instead of someone else were probably much better off because I was there.

It’s a tough line to draw, but I eventually concluded that participation was becoming collusion, and I had to bail.

Report comment

I realise this conversation is diverting from the subject of the post so I’ll keep this brief.

Where reality is as far from the rhetoric of an organisation as it is in psychiatry, anyone telling the truth will be punished and discredited. Any example of dissent from the party line, however small, will attract anger and derision.

It wouldn’t matter if the majority of staff privately agreed with a particular instance of truth, most would still respond to the group identity threat with at least tacit approval of any resultant punishment. Helping a truth-teller in these circumstances is advising them to keep their truth to themselves.

It’s hard for me to get a handle on how any meaningful reform is possible in these circumstances because in most countries, the absence of any meaningful accountability (including the unchallengable legal status of the records they write), and extent of coercion legally allowed, is greater than that available to any person or organisation, including criminal law enforcement and the spy agencies that purportedly protect citizens from international terrorism.

Report comment

I agree absolutely. That’s why I had to quit.

Report comment

I notice we’re dealing with scientism, rather than real science. Scientism is a kind of religion that worships allegedly scientific discoveries, using “science” as a kind of Godly figure passing down revelations from Heaven to the unwashed herd of mere mortals. Real science is an unknown world to the “scientismists”.

Report comment

bcharris

You just revealed in this comment why it is SO WRONG for this author to continue to use the term, “scientism” repeatedly in his titles and subtitles throughout his blogs. The use of the word, and people’s interpretation of it, usually make no sense at all.

This blog is NOT exposing any kind of MISUSE of science or exposing someone being TOO scientific (although I’ve never understood how that can be a problem) where science does not apply. This is exposing nothing more, or nothing less than, “bad” science, “corrupted” science, “phony” science, and/or simply “pseudo-science.”

The author does use this latter phrase “pseudo-science” in his last sentence when he drops the phrase “pseudo-science scientism.” This ends ups being some type of gibberish phrase, like saying “bad bad” or “phony Phony” etc. etc.

Dr. Timimi’s blogs contain some very important scientific and political exposure of Biological Psychiatry. But when he uses the term “scientism” (which he has NEVER carefully defined) he detracts from, and undercuts, the heart of his message. There is NO USEFUL PURPOSE for his use of this term in his critiques of psychiatric oppression.

The term “scientism” is MOST OFTEN used by people who want to attack the legitimate use of science in its exposure of superstition, climate change, and other controversial topics such as certain religious myths. Here it is understandable why someone might resent people being TOO scientific when they are relying on faith to determine reality, and holding onto some type of Right Wing agenda.

Both psychiatry and their colluding partner, Big Pharma, operate under the cover of alleged legitimate science, but this blog (along with all the other exposures at MIA) have revealed that these institutions only distort, pervert, undermine, and corrupt the scientific method in order to arrive at their false pseudo-scientific, and ultimately harmful, conclusions.

Please leave it all at “pseudo-science” and drop the nonsensical term “scientism.”

Richard

Report comment

“scientism |ˈsīənˌtizəm|

“noun rare

“thought or expression regarded as characteristic of scientists.

“• excessive belief in the power of scientific knowledge and techniques.”

Now that the “scientific knowledge” is out showing that the psychiatric drugs create the symptoms of the “serious mental illnesses”:

https://www.alternet.org/story/146659/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america – symptoms of “bipolar”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome – negative symptoms of “schizophrenia”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome – anticholinergic toxidrome = positive symptoms of “schizophrenia”

Meaning the “serious mental illnesses” have known iatrogenic, rather than a genetic, etiologies. “It’s a lot worse” than “scientism” or even “pseudo-science.” Today’s psychiatric practitioners are utilizing their “scientific knowledge” to intentionally harm innocent humans for profit.

Report comment

Dear Dr Tamimi, Thank you for this Article.

I would say that “it’s” not even “Scientism”. It’s a lot worse.

I believe in 2018 in the UK that 64 million prescriptions for antidepressants were written up – equivalent to 1 for every man woman and child. But 30 years ago in the UK practically “nobody” consumed antidepressants.

The next thing is that I believe it’s now widely accepted that if a person develops problems quickly after they withdraw from a psychotropic that this would be a withdrawal or rebound problem rather than a return of “illness” problem. This position would contradict the legitimacy of most historical “relapsing as a result of stopping treatment” diagnoses.

Report comment

Dr Timimi,

What happens if a person Recovers (No more Disability + No more Hospitalizations) from Severe Mental Illness (Disability + Hospitalizations) through carefully withdrawing from medication?

Is this person allowed to Recover, or are they “A person with A Severe Mental Illness Diagnosis”?

If this is the case, then why spend £100 Million per year on looking for Solutions to “Severe Mental Illness”.

Report comment

Dr. Tamimi- Thank you for the critical review of the various elements that have help manipulate and sell the BIG PhrMA poison to the developing bodies of our children with the acquiesce of parents and other caregivers. You speak of the “McDonaldisation” of growing up and the “expert” opinions we have become so reliant on. That part of the equation is where we must focus to change this sad and frequently desperate situation.

I am a parent, a former patient, someone who has worked in this field and has also been harmed by it. As a parent, I am struck by the way my daughter and her friends now describe themselves as variously disordered- Having panic attacks, anxiety disorders etc.- they own and define themselves using these terms without any real understanding of what the labels mean or subject them to in terms of their own choices and experience of agency as they deal with the very real challenges and changes experienced while growing and becoming.

At various points in my own relationships with the “experts” I have had to make a choice about whether I thought their opinion was worthy of consideration or simply bullshit. On most occasions, the latter was the case and I escaped their intervention and the prison that would have placed me in. I continue this pattern with my child and am truthful with her about the reasons and skeptical approach I have towards those attempting to define and confine with diagnostic labels. These practices, and the narrative that drives them has become so ubiquitous and difficult to escape. It requires constant challenge and education about alternative approaches that broaden and normalize the experience of growing up. It requires parents to be informed, curious and skeptical. It requires us all to be able and willing to call – bullshit and educate our kids to do the same.

Report comment

*acquiescence*

Report comment

You used to hear about when a child had something go wrong, he could just go home and tell his mother, and somehow, she would absorb all the hurt and the tears, and make it come out right. In the process, she would teach her child resilience and strength. What happened to those mothers?

Report comment

Where are those mothers? They’re at work. Few women (or in some cases men) are privileged enough to stay home and raise their children with another parent singlehandedly earning enough to support a family with today’s lifestyle and expectations. American’s have placed such a massive value on productivity that we’ve forgotten the art of child raising. Our kids are being raised by institutions – daycare from infancy, twelve years of public schooling. And the children being raised the way we were fifty years ago? So-called “free-range” kids? That’ll get the cops called and social services investigating. Wasn’t it just yesterday’s headline here at MIA something about how more mental health services in schools would help kids? So the short answer is, parents don’t do a whole lot of child raising these days – haven’t since well before I was a child.

Report comment

We don’t all have the perfect tools as mothers.

I could write a blog about it.

We can blame mothers, we can blame fathers,

we can then blame children who became mothers.

In all things, psychiatry pathologizes and destroys

any bits of sanity that tried to reclaim a tad of earth.

Report comment

Sami thank you for the great article.

You do have science on your side, but also

the honesty to come forth.

We are letting a lot of kids fall through the cracks,

which has always happened, but psychiatry makes

this ‘phenomena’ even more likely.

It is not even good to be a dog anymore because

the vets are offering Prozac, but my dog said no thanks.

Report comment