Editor’s note: In this second part of MIA’s report on compulsory outpatient treatment orders, Michael Simonson tells of how he came to report on this topic, the results from MIA’s survey of people who have experienced such forced treatment, his interviews with several of the survey respondents, and more on Andrew Rich’s life. Part one can be found here.

********

A Personal Disclosure

My professional background is in marketing, and that background has provided me with experience in conducting surveys. However, I had no experience as a reporter before working on this MIA Report.

This subject of forced treatment has personal interest for me. Fourteen years ago, as a college sophomore, I was involuntarily committed to psychiatric wards in two hospitals over a five-week period. I was heavily medicated against my will in both hospitals. Although I was never on an outpatient order, that forced-treatment experience had a profound impact on me.

As I began this reporting, Bob was adamant: I had to put my personal experience aside and listen to the stories that were told to me, whatever they might be. I spent several months interviewing people who have experienced compulsory outpatient treatment orders, and investigating Andrew Rich’s story. Many of the interviews were recorded, and all were fact-checked. I obtained court records to document Rich’s treatment in the legal system.

MIA’s Survey

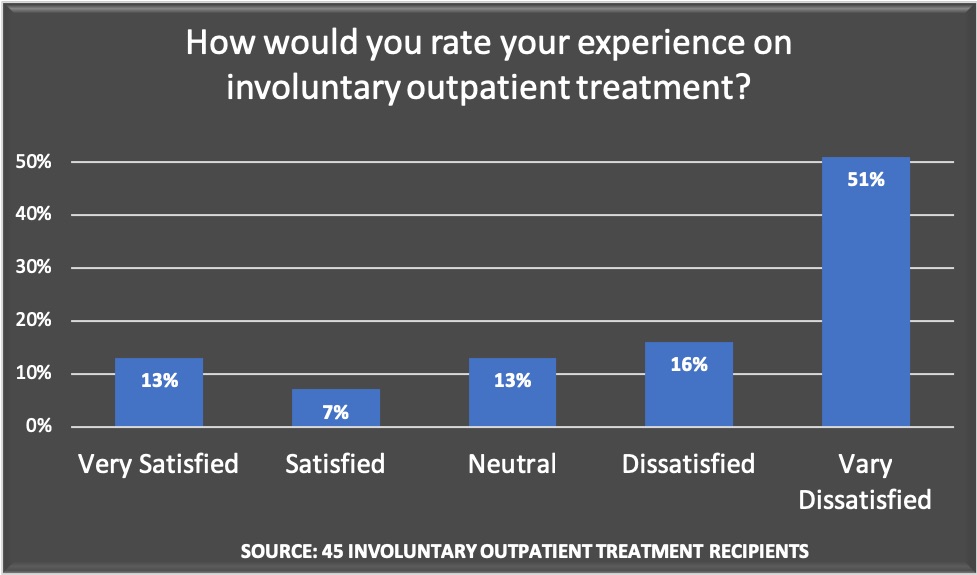

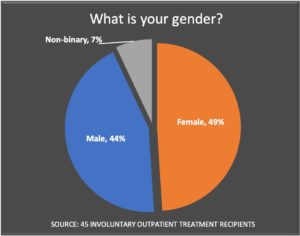

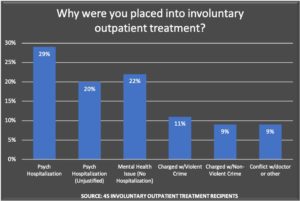

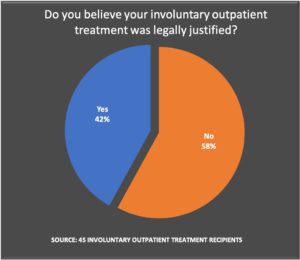

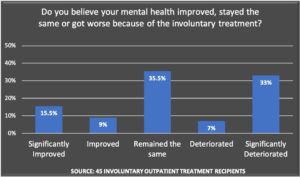

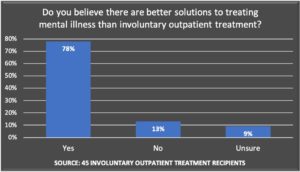

In our survey of current and former “recipients” of Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), or some other similar type of compulsory treatment, respondents regularly told of judicial proceedings that were “unfair” and of mandated treatment that they objected to. Two-thirds of the 45 respondents from the United States said they were “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with compulsory outpatient treatment.

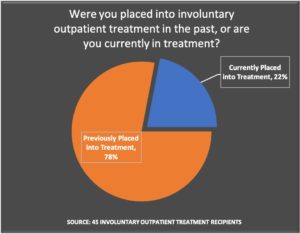

To conduct the survey, MIA recruited participants through a notice on the MIA website, a paid Facebook ad and in Reddit mental health forums of people who had experienced Assisted Outpatient Treatment or a related version of compulsory outpatient treatment. The respondents were a self-selected group, which included 10 current and 35 former outpatients.

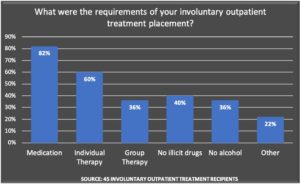

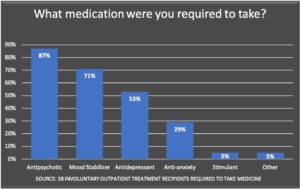

As would be expected, the most common reason for an AOT order was its use as a step-down from an inpatient hospitalization. Most were mandated to take psychiatric medication, with antipsychotics the court-ordered drug of choice.

The majority of respondents found AOT legally objectionable, medically unnecessary, and harmful to their mental health.

Interviews with AOT Recipients

In addition to conducting the survey, I spoke with twenty-six Americans and two Canadians who had been ordered into AOT or similar involuntary outpatient treatment programs (most of whom also took the survey). All 28 described deeply distressing outpatient experiences. Many were outraged, in particular, at the attitudes of the doctors, nurses, social workers, judges and attorneys who oversaw their treatment.

“A social worker came daily to watch me take my meds,” a Milwaukee, Wisconsin woman said about her 2012 court order. “It’s as if they assumed I didn’t want to get better.” A New York woman who recently got off her court order remarked, “I don’t get it. I’m not a criminal, and I feel like we’re free to do what we want with our bodies.”

Below are stories from four involuntary outpatient treatment recipients that I believe best represent the many comments about the failings of AOT.

Jill Kesti

In early December 2016, Jill Kesti was in the throes of a manic episode inside her Lansing, Michigan home. She hadn’t eaten or slept for two weeks and, in her own words, “was crawling on the floor and imagining the world from a 3-year-old’s point of view.” Understandably concerned, Jill’s boyfriend drove to a nearby police station to ask for medical assistance. Without a warrant and without knocking, officers entered the house, handcuffed Jill and drove her to a local hospital. The next day she was involuntarily committed to a psychiatric ward at War Memorial Hospital in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan

By her own count, Jill had been admitted to psychiatric hospitals, voluntarily and involuntarily, approximately ten times prior to December 2016, though she had no history of exhibiting violent or threatening behavior. “I’m a pacifist. I don’t kill flies. I’m Buddhist if you have to put a label on me,” she said. Her criminal record consisted of a single arrest for possession of marijuana.

Although she wasn’t working at the time of the December commitment, Jill had successfully supervised a team of graphic designers for over a decade at the Lansing State Journal until around 2013. Before that, she graduated near the top of her high school class and, in 1997, studied sociology at The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. At the time of her manic episode, she had recently celebrated a three-year anniversary with her boyfriend, and they were considering having children. As Jill was 41 years old, she felt that this was a decision they should make fairly soon.

Upon her December 5 admission to War Memorial Hospital, Jill was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Jill’s doctors described her mental state as “manic, severe with psychosis” and believed she posed a “risk to self and others.” In her hospital notes, a doctor also stated that “it was clear the patient would need a long-acting injectable due to long history of mental illness and medication noncompliance.”

By highlighting Jill’s psychiatric history and medication noncompliance, the hospital convinced a mental health judge to issue a three-month AOT order, which required her to take the antipsychotic medication Abilify. The judge granted the court order despite Jill’s rapid improvement after her early December manic episode; by the time she was discharged on December 21, doctors noted that Jill had begun “to stabilize” and was “outgoing, social, appropriate with peers (and) staff and attended to her nutrition (and) hydration.”

Jill, who felt psychiatric drugs were counterproductive to her mental and physical health, was furious. She had “laid in bed for almost a year” while withdrawing from psychiatric medication in 2013. She recognized that she had been manic in the weeks leading up to her latest hospitalization, but felt she had the right to recover on her own. “I was safe in my home,” she said. ”I was where I couldn’t hurt myself or anybody else. I wasn’t on the road in my car. I was here in my house trying to get through it without (psychotropic) medication.”

Part of the reason she wanted to remain drug-free was her desire to have children. Antipsychotics like Abilify, when taken during pregnancy, have been shown to cause neonatal problems such as respiratory distress in newborn babies.

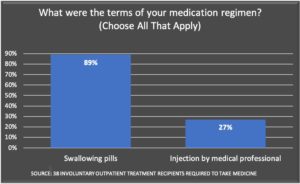

Jill was “shocked” with how the drugs were administered on AOT. “Every morning a lady brought the pills to me and watched me swallow. This woman came in snowstorms, no matter what, at 7:00 AM every morning, waking me up.”

After a month, Jill’s doctors switched her to monthly long-acting injections of Abilify, which led to an even more disturbing experience. “I felt like I was being raped every month. I was going to this office, this lady would pull my pants down and put the needle in my hip.”

The Abilify devastated Jill’s mind and body. “I was basically a zombie for a year. It’s like running through water. I couldn’t function. I slept twelve to fourteen hours a night. I ended up gaining like forty pounds. I didn’t really care about anything. I had no emotion. I couldn’t laugh or cry.”

In spite of her resistance to this “treatment,” Jill’s medical team attempted to extend her three-month AOT order an additional year when it expired in March 2017. In a letter to the court, Dr. C. Michelle Morgan wrote that Jill should be ordered to take Abilify because “she believes pharmaceuticals are more harmful than helpful.” Yet, in their letters to the court, neither Morgan nor Jill’s case manager David Cole argued that Jill was currently exhibiting psychotic or unstable behavior. Nonetheless, a judge agreed to grant a 12-month AOT extension that would last until March 2018.

Hoping to file an appeal, Jill tried to get a second opinion from a doctor who didn’t subscribe to a “medication-first” treatment model. Based on eighteen years of hospitalizations and therapy sessions, Jill knew that traditional psychiatrists would refuse to testify against the medication order. After conducting research, she discovered Toby Watson, a Wisconsin psychologist who focuses on “an individual’s wish and right to be treated without the use and reliance upon psychiatric medications.” In early April of 2016, Jill drove five hours to Watson’s office for a two-hour interview. After their initial meeting, Watson determined that the medication order was unwarranted.

In order to hire Watson to prepare a thorough report for the court, Jill needed to persuade her publicly appointed attorney, Rudolph Perhalla, to coordinate a $1,600 payment to Watson from the Michigan court that administered the AOT. However, it took six months for this to happen, and thus it wasn’t until a September 2017 hearing that Watson’s assessment was presented to the court. “The negligence of the court caused me to have that drug for another 6 months,” Jill said.

Watson’s report revealed insights seemingly overlooked by the doctors who ordered Jill into involuntary outpatient treatment. Watson noted that Jill’s manic episode in December partially stemmed from “past traumas,” including a sexual assault that occurred in November 2017. In addition, Watson wrote that Jill’s use of stimulants (including energy drinks, coffee, cigarettes and diet pills) contributed to a number of her prior manic episodes and hospitalizations.

Watson’s report also mentioned that Jill’s psychotic break in December may have been caused by two non-psychiatric pain medications (baclofen and prednisone) prescribed to her in November. Numerous studies have shown that the medications can result in mania and psychosis, including a 2006 analysis which warned that, “clinicians should consider baclofen-induced psychosis as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with psychosis during treatment with this drug.” Jill’s medical records indicate she told her treatment team, five months before Watson’s report was submitted to the court, that she believed the baclofen and prednisone caused her psychotic break. No adjustment was made to her court-ordered treatment plan.

With Watson’s help, Jill was granted a reprieve from the court order at the September 2017 hearing. After nine months of mandated injections, she no longer was forced to take Abilify.

As is well known, it is dangerous to withdraw quickly from an antipsychotic, and thus it took Jill an additional year to safely withdraw from Abilify. The AOT order, she believes, “stole” her chance to have children.

“I met the guy, we’re ready to go,” she said. “Let’s begin. I’m finally drug free. Now here comes the state to force me to take these medications that I cannot get pregnant on.”

Genevieve Andrus

Genevieve Andrus was ordered into outpatient treatment after she sought help for anxiety and depression at Providence St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana. She told hospital social workers that her abusive ex-boyfriend, who was the father of her daughter, was trying to break into her house. In fact, she already had taken out a restraining order against him. Nonetheless, hospital social workers considered Genevieve’s claims to be evidence of paranoia, and committed her to the hospital’s psych ward.

After a month in the hospital, doctors told Genevieve they would transfer her to Montana’s state psychiatric hospital unless she agreed to participate in an AOT program. She was confused by the doctors’ desire to forcibly treat her. While she been admitted voluntarily and involuntarily to psych wards on six or seven previous occasions, Genevieve had no criminal record or history of violence. She ultimately consented to being placed on AOT because, after four weeks in the hospital, she was afraid of losing custody of her daughter. She turned down the chance to contest the AOT at a court hearing because she didn’t want to be transported to the courthouse in shackles, a traumatic experience that she had been subjected to during a previous hospitalization.

As part of the AOT order, a hospital employee came to Genevieve’s house one or two times a day to watch her swallow lithium, a mood-stabilizer drug often used to treat bipolar disorder, and Seroquel, an antipsychotic. Genevieve said the meds “snowed” her. She “couldn’t function, couldn’t do anything.” Every three to four months the AOT order would come up for review, but Genevieve repeatedly failed to convince her psychiatrist to end the forced treatment. After a year, she found a peer advocate willing to attend the renewal meetings with her. Emboldened by the peer advocate’s presence, the normally timid Genevieve told her doctor and case manager she was going to “fight” to get off the AOT. Genevieve’s newly discovered outspokenness worked. After a year and a half, in 2014, the treatment order was terminated. It took Genevieve two additional years to withdraw from the Seroquel she had been forced to take.

Zelda Menard

Both Jill Kesti and Genevieve were threatened with hospitalization for not taking their medications. Zelda Menard, on the other hand, was threatened with losing contact with her three-year-old son if she failed to comply with treatment.

In 2009, a Washington State divorce attorney hired by Zelda’s ex-husband drew up a custody agreement stipulating that she could only visit her then two-year-old son if she was taking her psychiatric medication. And even if she was “medication compliant,” the agreement stated, her son would still spend most of the time with her ex-husband. A family court judge approved the custody agreement even though Zelda was never accused of child abuse or of putting her son’s health or safety at risk, and she had a successful career as an elementary school teacher. In fact, she continues to teach today.

According to Zelda, the hospitalizations stemmed from verbal arguments with her husband, after which he either called 911 or drove her to a hospital for a psychiatric evaluation. Zelda admits that she entered into psychotic states prior to all three hospitalizations, but maintains that her husband also acted erratically. Zelda told paramedics, doctors and nurses about her husband’s role in her breakdowns and how he could be emotionally abusive, but most of her complaints “weren’t taken seriously at all.”

Ten years after the custody agreement was approved by the court, Zelda remains legally bound to take lithium if she wants to see her son. The custody agreement allows Zelda to see her son every other week, mostly on weekends. Last summer, she paid an attorney $20,000 to help her contest the agreement in court; a court commissioner refused to make any changes.

Zelda’s custody agreement is not as strict as the court orders that Jill Kesti and Genevieve Andrus had to follow. She does not face the threat of being arrested and locked in a psychiatric ward for not taking her prescribed meds. In 2015, Zelda’s psychiatrist allowed her to stop taking Geodon, an antipsychotic medication, and significantly reduced her lithium dosage. Currently, Zelda only has to meet with the psychiatrist once a year. Still, losing visitation rights because of medication noncompliance remains a possibility for six more years, until Zelda’s son turns 18.

Zelda wants others to know about the coercive psychiatric treatment she has endured over the past decade. “I don’t want to hide this crazy experience. I’m definitely an open book and want this out. I tried to ask for help from the ACLU and Disability Rights Washington, but nobody sees this as a problem.”

Sue

Like Zelda and Genevieve, Sue—who asked that her last name be withheld—also struggled to find advocates to contest her court-ordered treatment. In 2010, after suffering a nervous breakdown tied to her mother’s recent death and job-related stress, Sue voluntarily checked herself into the psych ward at a hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. Upon discharge, psych ward doctors prescribed Sue antidepressant medication that caused severe side effects; the worst side effects occurred when she tried to withdraw cold turkey.

“I thought I was dying and having a heart attack,” she told me. “Another time I thought my kidneys were failing.” When the side effects and withdrawal symptoms became unbearable, Sue would check herself into the local ER. “I didn’t know anything about withdrawal effects. I didn’t really understand tapering. They don’t tell you anything about that.”

After Sue’s seventh visit to the ER in a one-month span, doctors began to think her issues were related to mental illness. They sent her to the psych ward, where she was committed against her will. She was discharged, but involuntarily committed again a short time later.

During Sue’s second involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, her doctors petitioned a civil commitment court to place her into involuntary outpatient treatment. They ignored her lack of psychiatric history prior to 2010, and the absence of a criminal record or history of violence. “It was a really bizarre experience,” Sue said. “The outpatient court was in the hospital. They treat you like a criminal. They don’t spend much time listening to you. It’s a bureaucracy. They don’t care. They automatically label you as a crazy person. I was a white-collar professional with a college degree. I had this really good job. They would laugh and say ‘you never did that.’”

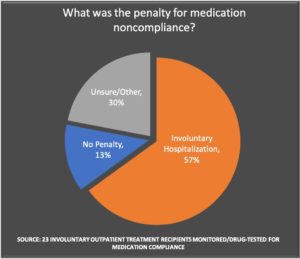

A mental health court judge agreed with her doctors, and placed Sue on a six-month AOT order that required her to take the antidepressant Zoloft and high doses of the antipsychotic drugs Zyprexa and Risperdal. If she didn’t take the drugs or attend her court-ordered therapy sessions, police would come to Sue’s door “right away.” After one such missed appointment, Sue had to talk the police down from whisking her away to the hospital for a “wellness check.” The drugs made Sue feel like she had been given a “frontal lobotomy”; she would “fall into this deep sleep for fourteen hours.” To add insult to injury, Sue’s health insurance did not cover the high cost of the medications—she had to pay out of pocket.

Prior to the expiration of the six-month AOT order, Sue experienced another adverse reaction when attempting to withdraw from her medications, leading to a third involuntary psych ward admission. The doctors on Sue’s psych ward, unhappy that she had stopped taking the court-ordered medications, sought to extend her involuntary outpatient treatment for six additional months. They also said that her withdrawal symptoms were evidence her mental illness was “coming back.” For unclear reasons, Sue wasn’t given a lawyer at the extension hearing.

“I didn’t have anyone there to defend me. I didn’t have a jury trial. I talked with an evaluator who was filling out a checklist. It was happening really quickly. I tried to say the drugs were messing me up. (The evaluator) just nodded her head. She had no sympathy. I looked terrible and she saw that, and it struck her [as a sign of mental illness].

I go sit in another room and found that I had to be on court ordered outpatient treatment for another 6 months, and that’s it. I felt like I lost all my rights. It was like Alice in Wonderland and Dante’s Inferno combined. It was this bizarre world . . . no one heard me. It’s like trying to scream through water. . . . They never told me what my diagnosis was. They don’t tell you the details. They just decided to continue [with the treatment]. They would tell my family members, but they were told not to discuss things with me because it might upset me. It’s like you’re a child. You have no rights.”

Sue was able to get off the involuntary outpatient treatment only after moving out of state to live with family, near the end of the second six-month court order. The court “came looking for me. I got all these notices,” Sue recalled. “A family member contacted them and said I had moved. And they decided to dismiss (the AOT).”

Sue is still haunted by her year-long AOT experience. During the involuntary outpatient treatment, she got laid off from her job, her partner left her, and she amassed tens of thousands of dollars in medical debt from her inpatient psych ward admissions. “I had no idea how easy it would be to get into that mess . . . I look back now and think, these people don’t know what they are doing.”

The Hidden World of Wisconsin’s Civil Commitment Courts

While reporting on Andrew Rich’s story, I conducted a series of interviews with his mother, Elizabeth Rich. It would not have been possible to document Andrew’s story were it not for the fact that she is an attorney and thus knows how to navigate the legal system, which can be particularly byzantine—and secretive—when it comes to mental health proceedings.

Authorities regularly cite medical privacy laws for keeping these proceedings hidden from the public. The Sheboygan County District Attorney’s office, citing such laws, refused to even acknowledge that one of its prosecutors had worked on Andrew’s case. The Sheboygan County Health and Human Services department refused to release any of Andrew’s medical records for the same reason, and was unable to provide civil commitment court records. Wisconsin’s Civil Court Access was a great source for criminal records, but does not list civil commitment court records because those records are “not open to public inspection.” The Wisconsin Public Defender’s office has a wonderful blog that documents some of the bizarre civil commitment cases they have litigated, but their office refused to comment on this story, or about any other aspects of the civil commitment system.

However, in this instance, Elizabeth Rich attended almost all of Andrew’s hearings and saved court transcripts, evaluation reports and emails with doctors, and she shared these documents with MIA. Those documents made it possible for MIA to tell of Andrew’s life and death in Part I of MIA’s Report on AOT.

Furthermore, to fully understand the nature of the legal proceedings that forced Andrew to take antipsychotic drugs, it is helpful to know more about the professional practices of his court-appointed psychiatrist, Daniel Knoedler; the conditions inside Winnebago Mental Health Institute; how difficult it was for Andrew to find an expert who would take up his case; and the poor legal counsel he received from one of his public defenders.

They Call Him a Pill Pusher

As was reported in part one of this MIA Report, Daniel Knoedler shows up on Medicare Part D records as a prolific prescriber of antipsychotics. He was insistent that Andrew Rich needed to stay on these drugs. I interviewed three other patients of Knoedler, all of whom told of experiences that echoed Rich’s. They described Knoedler as a “pill pusher.”

Knoedler, for his part, declined to be interviewed.

The first patient of his that I spoke to was Jackie Scheidt. Jackie saw Knoedler because he was the only psychiatrist in the area who accepted her government insurance plan.

Knoedler, she said, has a “close minded attitude” about psychiatric drugs, and “brushes people off and dismisses peoples’ concerns” about the drugs. In one instance, Knoedler prescribed a medication for panic attacks that Jackie protested wasn’t safe, but he ignored her. After she took the drug, she ended up in the hospital. “He just wanted to cram (drugs) down my throat.”

Jackie has several friends who have been court-ordered to see Knoedler for psychiatric treatment, and much like Rich, her friends were transformed by the drugs he prescribed. Before seeing Knoedler, she said, her friends were “talkative and happy go-lucky”; afterwards they turned into “robots . . . on auto-pilot.”

Just prior to this article’s publication, Jackie said that she was dropped as a patient by Knoedler. In a letter sent through the mail, Knoedler expressed concerns over “rumors” that she was complaining about his misconduct.

Like Jackie, Destinie Thede started seeing Knoedler because he accepted her government insurance plan. In her 15-minute appointments with Knoedler, he would “up the medication, and up it again and up it again,” she said.

The polypharmacy prescribed by Knoedler led her to develop tachycardia, at which point Destinie saw a cardiologist, Dr. Coulis, who told Knoedler he had to stop giving her this mix of medications. After Destinie stopped the polypharmacy, her tachycardia went away. Coulis said that someone with an existing heart condition “probably would have died” on the drug cocktail she had been prescribed.

“When do I get the right to discuss moving off those medications?”

Michelle, who asked to be identified only by her first name, has been on a Sheboygan County outpatient commitment court order since 1996. “It’s been so many years of this,” she told me. Knoedler has been her court-appointed psychiatrist since 2002; she currently meets with him “once every three months” for 15 to 20-minute therapy sessions, which she described as coercive and counter-therapeutic.

“If (I) express an extreme emotion, he analyzes that. And my emotions weren’t that extreme. It was distaste or sadness or frustration. And I wasn’t allowed to feel those things without fear or retribution. He would say, ‘you do have this issue.’ . . . When does it get to the point where you can have an emotion without you having a mental health issue at that moment in time?”

Michelle is currently ordered to take five psychiatric medications, including injections of the antipsychotic drugs Risperdal and Invega, and the oral antipsychotic Geodon. “They have me on so many meds that it’s unbelievable,” she complained. “When do I get the right to discuss moving off these medications? Do we set goals towards that or does it never get discussed?”

Since Knoedler began seeing Michelle, she has “felt (too) intimidated” to ask him more than “once or twice” to end the court order. “It was coercion the whole time. Dr. Knoedler made me afraid. He used intimidation techniques to have me avoid going to another doctor.”

On one occasion, over a decade ago, Michelle “wholeheartedly” expressed disagreement with Knoedler about the terms of her outpatient commitment. As a result, “he immediately had the cops pick me up and take me up to the hospital, after no violent threats” (Michelle said she has no history of violence).

Michelle has been forcibly hospitalized so many times during her twenty-plus-year commitment that she was asked to speak about it. “Would you believe they had me give a speech to police officers to teach them how to do trauma-informed care and crisis intervention?”

Most of the forcible hospitalizations were because she missed an appointment, she said.

Michelle also said that that five or six years ago, Knoedler presented her with a deal. If Michelle agreed to remain on the order, Knoedler said that he would let her take her disability “money out of family services.”

Michelle consented, reluctantly. “Now I have my own money, but I had to stay on commitment to do it.”

Michelle stressed that the excessive medications, unjustified hospitalizations and unsympathetic treatment she has endured during her outpatient commitment is “a county-wide problem . . . this goes much deeper than Dr. Knoedler . . . these practices of putting people on meds, taking their rights away.”

Michelle’s commitment order originated in 1996, after she was raped. “I attempted suicide because I was anxious and upset. (The doctor) gave me treatment for that and then I tried to run away, and he ended up hospitalizing me.” Two months after the hospitalization, Michelle learned she was pregnant. Her doctors, she said, “offered no type of counseling to keep the child or to even give me guidance to make my own decision, which was left to my family.”

Michelle received an abortion, but was unable to escape involuntary treatment, which included a court-ordered birth control regimen (even though she wasn’t sexually promiscuous). “They kept hospitalizing me as I attempted to break free and move on . . . They were able to get a Chapter 51 3-party commitment. I don’t know how . . . they kept throwing me in group homes.”

Her underlying PTSD, depression and anxiety were never addressed. Instead, doctors focused on her “psychotic” behavior. “They led me to believe I wasn’t capable of doing anything on my own,” Michelle said.

Inside Winnebago Mental Health Institute

After he was committed to Winnebago Mental Health Institute in June of 2017, Andrew Rich complained to staff about his treatment, which led, his mother said, to his being “routinely restrained,” and placed in seclusion. A federal inspection would later validate his complaints, but what the court would see in his record was that he had needed to be restrained, which could be taken as evidence of his being a “danger to self and others.”

The deafness of the court to Andrew’s complaints about the conditions at the hospital can be seen in a report by psychologist Kevin Miller, who was sent by county officials to Winnebago to evaluate Andrew’s mental health. According to the report, Andrew started their meeting by “discussing a variety of alleged human rights violations he believes have transpired at WMHI and other locations.” Yet, rather than discuss this subject with Andrew, Miller redirected the conversation to matters related to Andrew’s strange behavior on the night of May 8 and his current mental state.

In his report, which the county used to secure Andrew’s initial six-month commitment, Miller concluded that Andrew was a danger to others and should be held in a locked hospital unit. As evidence of this “dangerousness,” he referred back to the police report. “While in a manic state the subject was approached by law enforcement who indicated he ‘squared off to fight,’ putting the officer in danger.”

However, in his report, Miller confessed that he, personally, had not witnessed any such threatening behavior. “Mr. Rich,” he wrote, at the bottom of his report, “was an enjoyable fellow who was not threatening or hostile in any way during our meeting.”

The validation of Andrew’s protests about conditions inside Winnebago Mental Health Institute came later that year. A report by federal inspectors documented 48 violations at the institute, which included improper patient care, inadequate nursing staff, poor oversight of medical staff, and an unsafe physical environment, among others. One violation cited by the federal investigators was related to a patient who died after not receiving medical care for over 12 hours.

But for Andrew, his protests against such conditions had simply become a black mark on his record as he moved through his various court proceedings.

Andrew’s Public Defender

After Andrew lost the December 2017 recommitment hearing, he had two options left. The first was to find a psychiatrist willing to testify at a rescheduled commitment hearing that involuntary treatment wasn’t warranted. However, all three psychiatrists Andrew met with refused to testify on his behalf.

Without a psychiatrist in his corner, Andrew’s only remaining option was to file an appeal of the December re-commitment ruling. No longer able to afford a private attorney, Andrew was appointed a public defender. A 2015 report found that Wisconsin public defenders were the lowest paid in the nation at $40 per hour.

Even if Andrew had been appointed the state’s best public defender, he would have faced an uphill battle in court. Instead, he was represented by Len Kachinsky, who had a public record of incompetence.

In 2006, Len Kachinsky had been appointed by the state to defend Wisconsin resident Brendan Dassey on a murder charge. Rather than argue in court that Dassey was innocent, Kachinsky hired a private investigator to goad Dassey into confessing to the murder. While the confession proved worthless, it allowed police to arrange a phone call between Dassey and his mom in which he gave a confession that was eventually used to win a conviction.

State officials removed Kachinsky as Dassey’s attorney. Kachinsky’s “actions went on to taint the trial,” according to Laura Nirider, co-director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth at Northwestern University School of Law.

Kachinsky’s behavior in that case was famously documented in Netflix’s 2015 documentary “Making a Murderer.” In a review of the award-winning film, Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel reporter Bruce Vielmetti wrote that Kachinsky’s legal representation of Dassey “comes off as one of the bigger incompetencies and injustices.”

As a result of his poor representation of Dassey, Kachinsky was decertified by the Public Defender’s office from working on homicide cases. However, by 2017 the state had allowed him to work on civil court cases like Andrew’s.

Charles Wingrove, Andrew’s attorney from the December 2017 recommitment hearing, sent Kachinsky a letter spelling out six “issues” that could be successfully appealed. Elizabeth Rich said that Kachinsky waited until the last moment of the 60-day appeal window to file a motion, and when he did, he betrayed his client in an extraordinary way.

Kachinsky filed a no-merit petition, which signifies that an attorney believes his client’s basis for appeal is frivolous. In effect, Kachinsky undermined Andrew’s opportunity to appeal the court order.

Andrew could have filed another appeal, but would have been prohibited from contesting the six legal defects identified by Wingrove. Instead, Andrew chose to wait until the December 2018 recommitment hearing to fight the court order, which he lost. Kachinsky did not represent him at that hearing.

Kachinsky has since been arrested on charges of stalking and violating a restraining order. On July 9, the Wisconsin State Supreme Court barred him from serving as a judge for three years retroactive to July 2018, though he continues to handle criminal appeals as an attorney.

Is This How AOT Is Supposed to Work?

E. Fuller Torrey and other proponents of AOT regularly claim that compulsory treatment orders are granted only when the “mentally ill” meet specific criteria. Yet, most of the people on AOT orders that I interviewed didn’t seem to meet the criteria, and that was true in Andrew’s case too, and so I called Torrey to ask him about this.

I told him that most of AOT “recipients” were non-violent women with no criminal history, and that they reported that the antipsychotic and mood-stabilizer medications they were ordered to take caused them considerable dismay, pain, and hardship.

Torrey did not find this alarming. “AOT has different rules in different states, and is very clearly set up to be used for people who need it. I can’t tell you who is put on it in what state. All I can tell you is that we have tried to make the rules as tight as possible so the people on it are the people who need it, and who have a history that justifies making them take medication to improve their own lives and improve other people’s lives.”

I then asked Torrey about the case of Andrew Rich, and whether his story was an example of someone getting wrongly trapped in an AOT program, as Rich didn’t have a history of repeated psychiatric hospitalizations, or a history of violence.

“I think generally [AOT] is working,” Torrey said. “I won’t say that there [isn’t] some misuse of it, but generally I think it’s working . . . obviously I can’t comment on this case. You’re saying he’s running around naked. He may well be a danger to himself on it. Running around naked is not good.”

Andrew’s V.O.I.C.E.

Prior to Andrew’s death, his mother Elizabeth had become so alarmed by the legal process that had ensnared her son that she left her law firm to represent people who want to get off involuntary commitment orders. “We’re taking away someone’s liberty,” she told the Sheboygan Press.

Since then, she has launched a nonprofit advocacy group, Andrew’s V.O.I.C.E (Victory Over Involuntary Commitment Excesses). “The goal is reform of mental health laws and the entire mental health care system, which I perceived to be a very broken system,” she told the newspaper.

Elizabeth plans to become a registered lobbyist, and to advocate not just for the reform of civil commitment laws, but also of the drug laws that saddled Andrew with a felony conviction that severely limited his educational, housing and occupational opportunities. Her V.O.I.C.E website describes her new mission:

We can and must do better than this. It is our hope that Andrew’s tragic passing will serve to raise awareness of the significant defects in how our government handles criminal cases involving drug addicts and the mentally ill, as well as how involuntary civil commitments are handled. It is, literally, a matter of life and death.

Remembering Andrew

Once Andrew Rich got addicted to Oxycontin in high school, after he injured his knee, he clearly led a troubled life for the next nine years. He had numerous brushes with the law, there was a felony conviction for possessing heroin, and he struggled in emotional ways throughout this period.

The felony conviction is what haunted him after he got sober in 2013—it made it difficult for him to get work and back into school.

Yet, while reporting on this story, I was repeatedly struck by how his friends and family members expressed how much they adored him.

“He was super caring, very concerned, extremely loyal,” Andrew’s ex-girlfriend Lisa Baniak told me after I contacted her through Facebook. “I lived with him for a little. He’d let people stay at his house and rent a room even if he didn’t like the person that much. He just wanted to help people out all the time . . . Andrew was an empath. He loved to love.”

Tanya Payne, who grew up two houses down from Andrew and whose husband was his best friend, considered Andrew part of her family. “He took our kids on walks in the woods. They would go exploring. They would have swordfights. He would come over for bonfires.”

Andrew, Tanya added, “had a presence before entering a room. His eyes would light up.” Andrew’s brother Jacob similarly recalled that he “got his energy from interacting with people and having a lot of friends.”

Meanwhile, his mother spoke of his empathy toward other patients at Winnebago Mental Health Institute and the group home he went to after being discharged from Winnebago. Here is what she told me:

“He often talked to me about the people he met at both places. He said, ‘you know mom, there might be a few people there who really need help, but I’m not even sure about that . . . I don’t even think any of them are mentally ill. They’re just . . . almost all of them are artists of one kind or another, very creative people. There’s nobody who’s violent . . . the ones who seem the worst off are the ones who are super sedated . . . there are probably a quarter of the people that are just sitting in a corner literally drooling and they can’t focus their eyes and they can’t speak, not because they are mentally ill but because they are overmedicated.”

Andrew’s mother found this “so shocking. Here I am 60 years old — I had no idea this was going on under my nose that people were being treated like this.”

She went on:

“The other issue Andrew raised about his fellow patients was that he was really grateful that he lived in the apartment that I owned, because so many of the people that were in there with him . . . [they] were forcibly ripped from home and most of them don’t own their own place, they’re renting . . . [If it weren’t for the apartment I owned] all his stuff would have been on the street. He would have lost all his possessions, all his photos, everything that meant so much to him. A lot of people there had lost their pets, you know they were ripped away from their pets. The pets get sent to the humane society. If you think of somebody who is a little emotionally fragile, you take away everything, every possession, their pets, everything that’s stripped from them, my gosh, what a horrible thing.”

Andrew’s maternal grandmother, Irene Gamsky, similarly described Andrew as a “gentle person.” Andrew, she said, “was a writer, he was a poet. He was such a good friend and decent kind of person.”

At his funeral, recalled Andrew’s grandfather Neal Gamsky, there were so many people who wanted to remember his grandson that the presiding minister had to put a cap on eulogies.

“The line was so long,” he said. “They were packed in there. One after another, acquaintances, boys, women, men, kids he grew up with, kids he was social with. I was amazed at how many friends he had.”

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

We need to get forced treatment and psychiatric drugging prosecuted in the International Court. Penalties will usually start at 20 years.

Germany did not invent Universal Jurisdiction, it was handed to them with their constitution. But they are making very good use of it.

https://www.ecchr.eu/en/publication/burbach-is-not-guantanamo/

Report comment

“most of AOT ‘recipients’ were non-violent women with no criminal history, and … they reported that the antipsychotic and mood-stabilizer medications they were ordered to take caused them considerable dismay, pain, and hardship.”

Jill was put on AOT due to a likely psychiatric drug withdrawal induced “super sensitivity manic psychosis.”

Genevieve was put on AOT to cover up her abusive ex-boyfriend’s crimes against her.

Zelda was forced to take drugs because her evil ex-husband had his lawyer make that a condition, for her to see her own child.

Sue ended up on AOT because she was upset about her mother’s passing and job stress, as well as due to withdrawal symptoms of psych drugs.

Jackie “and friends were ‘talkative and happy go-lucky;'” prior to psych drugs, “afterwards they turned into ‘robots . . . on auto-pilot.'” But we don’t know why they were all forced to see a psychiatrist.

We also don’t know why Destinie saw a psychiatrist.

“Michelle’s commitment order originated in 1996, after she struggled to cope with being raped and the pregnancy that resulted from the rape.”

None of these issues sound like “lifelong, incurable, genetic mental illness” problems.

It sounds like a lot of AOT to cover up men’s crimes against women, and a lot of AOT to cover up the adverse and withdrawal effects of the psychiatric drugs, so the psychiatrists can’t be sued for all the harm they’re doing.

Covering up abuse of women, and especially silencing child abuse survivors, has been a primary actual function of our “mental health” workers for over a century.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

And turning child abuse survivors into the “mentally ill,” with the psychiatric drugs, is the number one actual function of today’s psychiatric industry. Today, “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).”

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

As to the psychiatric drug induced, iatrogenic etiologies of both the “bipolar” and “schizophrenia” diagnoses.

https://www.alternet.org/2010/04/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Why is covering up child abuse and rape the number one function of all our DSM deluded “mental health” workers today? Because NO “mental health” worker may EVER bill ANY insurance company for EVER helping ANY child abuse survivor EVER. The DSM is a child abuse and rape covering up system, by design.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Shame on this “dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” But covering up child abuse and rape is a multibillion dollar industry for the doctors, and the religious hospitals in which they work.

Thank you, Michael, for pointing out the abuse of AOT orders. And forced treatment in general, is being abused, for similar unjust reasons, as well.

Report comment

Absolutely on point, Someone Else. And absolutely sickening. Thank-you for summarizing these crimes against women so succinctly.

Thank-you for the links.

Report comment

I do have to commend Andrew’s mother for keeping such good records.

I also had a friend that told me how the asylum’s psychiatrist had threatened her with more detention unless she took a whole cocktail (or I think more appropriately called arsenal) of drugs; and she displayed how they made her shake. She then ended up committing suicide, shortly after, when she came down from that. And she had told me how down she would get after being committed, and I had warned her mother stating that if she was committed again, I thought they would lose her.

But for the life of me, to try to get any record of what all happened.

And no, her mother didn’t start a movement.

And the girl herself prior to all of that had taken someone in, and then when he got difficult had him involuntarily committed, with help of his NAMI parents, all of this quite before she told me how depressed she got when she herself had been committed.

She was livid when I criticized her for having someone committed. When she herself was committed, a friend of her’s was livid that she got out too soon, stating that she was still “psychotic,” this after they had her committed with quite a few lies (she supposedly was running around naked, which the police informed me of when I called them to say that her “friends” had trespassed into her house (where they called her case manager). I only did that after wards, because one of them had sarcastically suggested I do that when I told them if they didn’t get out of her house I would (call the police) so I knew they would fill the police with “stories” with lies; So I hadn’t yet to only later hear how they had already lied enough that the police were telling me untruths)) (((sound like the mental health system!?)))

I mentioned to the moderator here that it would be “interesting” to see brain scans of people in such behavior, and how much that correlates with brain activity involving addiction. But then he pointed out that they would try to make that out to be healthy behavior.

Anyhow, she was committed twice, and so fixed up that when they let her out at first her mother told me she wouldn’t even know whether she was taking her medications, and then she slid into hanging out with ANYONE probably, out of desperation, that she got raped, and when she was in the asylum again her house was broken into by people she had run into.

The wonderful “Nun” processing her to get committed had her restrained when she couldn’t hold her urine because of Geodon (which is a side effect of it), which she couldn’t clearly point out (and made it clear such behavior was normal) to the nun. And when she said she was raped the nun said she was being too provocative. And then her sister later had to clear that up, that she had been raped. And in trying to get away from the people that were committing her, she had torn her Achilles tendon, which they didn’t attend to in the medical facility called a psychiatric institution, although they drugged her up so nicely, I’ve already related what happened when she got out to be committed again. Her Achilles tendon was ruined because they never tended to it in time, they told her they couldn’t ever fix it afterwards.

And this is all very typical history of what goes on in an asylum, and then isn’t reported properly. And considered “normal” because “they tried….” “it was supposed to work….”

And it becomes more easy to make it out to be a tragedy, because it was supposed to work.

In the meantime, would anyone actually carefully talk to those going through it, or HAVING gone through it, you would hear these kind of stories over and over again. This one probably being a little bit milder than many of them.

Report comment

What did Patrick Henry say about psychiatric oppression of all sorts? Oh, yeah. “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

Report comment

Thanks Michael for Part 2 of this detailed report. Until this past year I had no clue these gross violations and inhumane forced treatments took place on a routine basis. The whole process seems to be running like some kind of shady and ruthless operation. You might expect to hear of this happening in a lawless third world country or a country run by dictatorship but certainly not in countries such as the US and Canada. Thank you MIA for shining a light on this and getting the information out there. My heart goes out to Andrew’s mother, family and friends.

Report comment

Very well documented and written. I see so many of these tragic cases every year, and I am happy to provide the courts with this much needed information. I am thankful for Robert Whitaker and others for putting together much of this initial research and writings. I encourage more professionals and doctors like myself to take these cases on, do the examinations, do the background work, and put forth the effort to truly inform the courts, doctors and families about the nature of psychiatric “care”. Together, we are saving lives and helping people recover! Feel free to use any of my information I often use in court: http://www.DrTobyWatson.com

Report comment

It’s impossible to get honest representation within Psychiatry, as doctors in Psychiatry are allowed to keep half the story off the records.

Basically speaking, doctors in Psychiatry are allowed to lie.

Report comment

“non-violent women with no criminal history”

Even if that were not true, we don’t want to allow forced treatments, or any uses of psychiatric drugs.

Report comment

“Theses drugs improve people’s lives.”

Shrinks’ for example. They earn $250,000 per year (or more) and professional glory by defaming people, making them die 25 years prematurely and forcing them to live in poverty and segregation.

What psych drug was Jill Kesti taking to keep her awake for 3 weeks? Mine was Anafranil. And shrinks pretend the psychosis was caused by noncompliance since “the meds never have that effect on anyone.” And after 3 weeks of no sleep I had bizarre notions of running around naked and screaming obscenities I could barely repress. MEDS COMPLIANT THE WHOLE XXXX TIME!

I tearfully told my parents how I couldn’t think straight on massive quantities of drugs, though I took them faithfully. The good doctor would kindly gas light me. “Those medications are 100% effective on anyone who takes them exactly as prescribed. And Haldol doesn’t cause seizures. Your daughter is obviously non compliant and lying like They all do.”

After years in the system I took to saying stuff that wasn’t true. Mom wondered at it since I had always been scrupulously honest.

Shrinks had turned me into a drug addict. Which explains my personality change. And due to their gas lighting I could no longer tell truth from reality.

Thank God I kept from killing myself and am mentally the woman I used to be. Only older and horribly sick with IBD which I blame on 2 decades of SSRI drugs.

Report comment

You can add me as another woman statistic who had her rights stripped away from her. I’ve been on AOT twice. Once in 2012-14 and now again now. Why? Because each time I tried to get off the meds I ended up in the hospital, sometimes several times a year. Now I am labeled non-compliant plus I have a criminal record because I took a taxi to the airport and had no money to pay. The arrest took me to jail, then shackeled in a forensic unit at Creedmore Hospital, NY and then I was moved to the mental illness section of the hospital for 3 months. The hospital social worker was of no use and threatened AOT out of the blue. The nurses administering the drugs were very unreliable and often gave incorrect doses. The psychiatrist was a nightmare. There was a lot of abuse there, such as food deprivation, etc.

The main thing I noticed was that AOT hearings are a bad joke, and these kangaroo courts are allowed to keep doing their dishonest shenanigans to mostly women I am now seeing. There is hardly anything written on the internet critical of AOT so it is hard to get any information on the subject except for here, on MIA.

Trying to get off the drugs is a real problem here in NYC, because there are no doctors who can help with that. So you are on your own. I was so desperate to finally get off the drugs the I tried on my own only to fail each time, experiencing super sensitivity psychosis. I did see Dr. Kelly Brogan in 2013 who claims to help people off drugs, but she doesn’t know how to help with antipsychotics and she kicked me out of her practice because I disagreed with her on her protocols. Yes, she does this to many patients. Not a very supportive doctor, to say the least. Her practice is also very expensive and so are the compounded drugs. If you are living from month to month of SSD, there’s just not enough money going around to be spending it all on expensive alternative doctors.

I think now at this stage of my life at 60 years old, I will have to give up the hope of ever getting off these drugs which will most likely kill me sooner or later anyway. I am now a dead zombie. Death will come soon enough. Any hope for a life worth living is now over for me.

Report comment

Precisely. I can’t afford Dr. Kelly’s expensive diet of wild salmon, grass fed beef and organic veggies. Let alone pay for office visits.

Glad for those she has helped. Maybe they’re depressed wives of millionaires.

Report comment

“Dr. Kelly’s expensive diet of wild salmon, grass fed beef and organic veggies.”

Also more biomedical bullshit. And it is not punishment for perpetrators and reparations for survivors either.

Report comment

Hi rmales. Do you have a few minutes to chat with me about your experience on AOT in New York? My email is [email protected] and my phone number is 201-572-1030.

Report comment

Thanks so much for this awesome reporting. I find hope here even though what happened was truly tragic. Thanks to you and all those who see through the lies and bullshit propagated by Torrey et al. Clearly, AOT has to go.

Report comment

Andrew thank you.

Report comment

Great article. Those who create and enforce these forced medications orders behave very much like the prison guards in the Stanford prison guard experiment. Give the guard a little bit of power and that power drives them to engage in Gestapo style tactics. Forced anything in medical care is a human rights violation. Informed consent should be mandatory and withdrawal of consent at any time is the proper legal standard of care.

Report comment

GENOCIDE.

Andrew Rich is only one of the fatalities….

….of GENOCIDE.

The genocide of psychiatry…..

Report comment