The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Leah Harris: Welcome to the Mad in America podcast. My name is Leah Harris. I am a political correspondent with Mad in America, and a psychiatric survivor activist. It is my pleasure to introduce you to Dorothy Dundas. She’s also a psychiatric survivor activist, a mother, a mentor, and an incredible supporter of the activists in all of our movement-building work, going back several decades. It’s such a pleasure to have you on the podcast, Dorothy.

Dorothy Dundas: Thanks, Leah.

Harris: I would love it if you could tell the listeners a little bit of the story of how you found this movement, and how you got involved. How did it all get started?

Dundas: Well, it’s really interesting because back when I was married in 1978, I had four children, and my husband at the time was a psychiatrist. And he said, “Come to a meeting with me. There’s a psychiatric meeting downtown in Boston and you might be interested.” So I went with him to the meeting. Only I never actually got to the meeting because in the lobby, right by the stairs, there was a sign with an arrow pointing down to the basement saying, “Judi Chamberlin reading from her new book, On Our Own.”

And I thought, “Well, gosh, that sounds interesting.” And so I went downstairs. Lo and behold, I never heard of Judi Chamberlin in my life, but there she was in this little room reading from her brand new book, which had just been published. And I was just completely amazed. So after I did her thing, I went back upstairs and told my husband, “My life is completely changed.”

Judi said, “Come to a meeting Monday night. We meet every Monday night.” So Monday night, I went. I forget where the first meeting was. Somewhere in Cambridge, every other Monday. Dan Fisher was there, Judi was there, David Oaks was there. And a couple of other people, whose names I no longer remember, because it was so long ago. But I’ve kept up with David, I’ve kept up with Dan all these years. I mean, that was literally 1978. That’s how it started.

Harris: Thank you. I was going to say, for listeners who may not be familiar with the work of the late Judi Chamberlin, she was one of the early folks who got engaged in trying to radically remake the system. And she wrote this incredible book called On Our Own. So you heard Judi, and what was it that you heard that undid you or made you think about things in an entirely different way?

Dundas: It’s not that I hadn’t been thinking about things. I had been thinking about things since December 4, 1960 when I was first locked up. I had never stopped thinking “What is happening to me? This is the most horrible thing. When I get out, good lord, I’m going to change things. I’m going to try to change things.”

So I finally got out in 1963. Even though I was raising my four children, I always thought about it. It was in the background of my mind all the time. So when I met her I was thinking, “Oh my god, this happened to her too! This is completely amazing. I have found my family. I have found my family of people who’ve been through what I’ve been through.” That was the most thrilling thing of all, to think that there were other people like me actually out there. Because in my regular life, I just wasn’t meeting people who’d been through what I’d been through. And I really didn’t talk about it very much, because people didn’t like hearing about it.

And so then, that started me writing articles for the Boston Herald and The Boston Globe. I would write op-ed pieces. I got completely obsessed with telling my story! This was way before cell phones. I had a typewriter and carbon paper. And my baby at the time, Matthew, was crawling around underneath my feet. I’m basically typing my story on a typewriter, with the carbon paper. Then I would put it an envelope, put him in his car seat, drive it down to The Boston Globe and leave it off. I just became obsessed with that and I had maybe three or four articles published, and wrote many, many, many letters to the editor.

Harris: I love this story because I think we take for granted this age of social media, where it’s so easy to share our story in a whole variety of different ways. I’m really appreciating the effort that it used to take to get those stories out. And so what is it that kind of propelled you towards telling your story, and what did it do for you to be able to express and to be heard in that way?

Dundas: I was propelled just by the sheer horror of what happened. I always knew I needed to tell my story, but it wasn’t really until I met Judi and met with those people on Monday nights, that I felt completely compelled. All I know is that it made a huge difference in me. I spent a lot of time choosing every word and then sending it out. The first article I wrote, I was still married, and I did not put my name on it. I simply said, “Mother of four, from Newton, Massachusetts,” or whatever. And the Globe was okay with that. But then the next one I wrote, I was already divorced, or certainly separated. Clearly I needed to put my name on it. And I heard back from a lot of people.

The purpose was to try to keep it from happening to somebody else. If a life could be saved by reading one of those op-ed pieces or one of those letters to the editor, then that will be good. The purpose of the whole thing was to educate people and to prevent it from happening.

Harris: If you could share for the listeners, the capsule version of what it is that you did experience and the story that you needed to tell. How did that factor into your work as a writer, as an activist and as an artist?

Dundas: Well, I think the details are actually pretty horrifying. They’re still horrifying to me. I took a small overdose when I was 19. My boyfriend had just left me. I took maybe half a bottle of aspirin, and told my parents. It was not a real suicide attempt, because I told them immediately. I went to the hospital. From that point on — remember it was 1960 — I got put in the Mass General. Within three or four days, they transferred me to Baldpate Hospital, which is a very small hospital in Massachusetts, where I was petrified. And immediately, because I didn’t talk, they diagnosed me as being “schizophrenic” and gave me insulin and shock without any anesthesia.

Which basically meant that they wake you up at six o’clock in the morning in the pitch dark in December, freezing cold. And there were four girls, all of us teenagers, in beds right next to each other. And one at a time, we would first get an insulin injection, which was supposed to put us in a coma, but it didn’t always do that. It was very slow in doing that. So by the time they came around to doing ECT, the guy would come in the room. He was wearing a black suit and had a little black suitcase, and he would open the suitcase, and there would be the ECT machine. He would stick the electrodes on my two temples and then he would say, “Is everybody ready?” Meaning, are all the nurses holding me, holding my legs down and holding my arms down, so when I had a seizure, I wouldn’t jump up off the bed. But they were not talking to me. Of course, I couldn’t speak. I mean, I was paralyzed.

And then one of those mornings, my little roommate Susan Kelly, she died in the bed from that. It was just plain horrifying. I think the fact that she died is also what propelled me into telling my story, because her life was lost right beside me. And any of us could have died from that. Any of us. It was really, really, really awful. I mean, we did it for six weeks, Monday through Friday for six weeks. And every single day I thought I would die. But here I am. I didn’t die.

Harris: And not only did you make it out to tell your own story, but I know that a part of your story is to speak for those who can no longer speak. People like Susan, who died as a result of these horrific “treatments,” which we all know are not treatment, but torture.

Dundas: Torture.

After my parents were told at Baldpate that they couldn’t do anything more for me, they sent me to the Menninger Clinic in Kansas, where I was put on a teenage ward. Everybody was locked up. There were probably 12 or 15 of us, all locked up. There, they put me on masses of Thorazine, so I could hardly move. My tongue swelled up, and I couldn’t talk. It was 400 mg of Thorazine. It was terrible.

I witnessed a young woman who had a baby. They’d taken her baby away from her in Argentina, and sent her there. And they would put her in cold packs, and she’d be screaming for her baby from this cold pack. I could hear her screaming for her baby.

Then they said they couldn’t help me anymore. They sent me to the Mass Mental Health Center in Boston, where they took me off all the medication because they didn’t believe in it, which was a good thing. So I had probably a year of Thorazine and then I was taken off when I got there.

Harris: What was the time span from the moment you attempted to take your own life until you kind of went through that cycle of shock, Thorazine and then off Thorazine?

Dundas: December, 1960 and I got out in mid-late January 1963.

Harris: I remember you and I were talking, because my father was in the Menninger Clinic around the same time, and we were trying to figure out if the two of you were in there at the same time. But we never quite figured that out.

Dundas: When I was there it would have been starting in April 1961, for about eight months. Everybody kept saying, “We can’t do anything more for her.” Mostly because of my behavior. I was so furious at being there that I would stop eating. I was basically objecting to everything that happened. I was really angry, really objecting, not playing by any of their rules. And therefore, they would say that they couldn’t help me anymore.

And I think honestly, the fact that I had so much anger, it’s probably what saved me. Because there were a lot of kids there who became completely mute and never said a word. And I’m not sure if they were saved.

Then I went to Mass Mental Health, where they also said they couldn’t help me anymore. And so I was then sent to Westborough State Hospital, which was like the end of the line. There I saw these elderly women tied to the chairs, and they were urinating on the floor. They looked to me to be very old. But then, I was 21. Maybe they were 40 or 50, but they just looked really old to me. They looked like they’d been there forever, and they might have been there forever. That was really shocking.

I need to tell you how I got out. A friend who was at Harvard Law School who had been locked up with me at Mass Mental Health Center — his name was Bob Joost. He is no longer living, but he would be happy to have his name here. Bob Joost was at Harvard Law School. And every time he got halfway through the third year of law school, he would end up at Mass Mental Health Center. He would get very “manic,” and they would lock him up. And so I made friends with him three times, because I was there every time he came. He kept coming back and I kept still being there. And so when he finally got out, he would come and visit me at Westborough every afternoon. He would leave law school and drive an hour out there to visit me. And then he finally went to my parents and said, “If you don’t get her out of here, I will get custody of her and sign her out, because she’s going to die in there. She’s never going to get out unless we take her out.” He finally convinced my parents to sign me out. And that’s how I finally got out.

When I got out it was really, really hard because I was kind of a shadow of my former self. I’d been very social, and I went to a very rigorous high school where I did well. But my brain was really crushed by the ECT. And my whole self was kind of flattened, as flat as a pancake by the whole experience. And so I just took baby steps, you know, teeny weeny weeny little baby steps. Which is probably why I loved that movie called What about Bob? where [Bill Murray] was talking about baby steps. And he would carry a little fish around his neck, in a little envelope full of water or something.

In order to get out of Westborough, I had to promise my parents in front of the superintendent that I would go to secretarial school. And at that point, I would have done anything to get out. So I promised I would go. I knew I probably shouldn’t run away again, because they would probably lock me up again and I would never get out. So, I went. I went every Monday through Friday and learned to type 120 words a minute. I became a typist, which really helped me a lot, because when I was writing my op-ed pieces on the typewriter, I could type really fast.

Harris: So it ended up working out in your favor.

Dundas: Exactly! And then I found two people to share an apartment with through secretarial school. They’d been sent there by their parents or something. No one had been locked up in there, but they were willing to share an apartment with me. And then one day, as part of the conversation, I brought up around dinner one night that I had been in a mental hospital. One of my roommates packed her bags and left that night, and never came back. She was so petrified of what I had said, and so scared of me and what I might do, which of course was crazy. So that was really interesting to me. My feelings were hurt, but I was mostly kind of “What?” I was not quite believing it.

Harris: You know who you are. And then, people hear “psychiatric hospital,” they think you’re going to take out a hatchet in the middle of the night or something.

Dundas: Exactly, exactly.

Harris: And that’s the society we live in. Right? We are still dealing with those kinds of stereotypes.

Dundas: Exactly. Anyway, after I got out of secretarial school, I got a job at Brigham Hospital, being a secretary there for a professor of surgery. And that was interesting. I learned a lot typing his letters. I typed his letters all day long, and I learned that smoking was bad for you because he was writing the first early letters about smoking. About cutting into people’s lungs and seeing that they were completely black from their cigarette smoking. And it wasn’t long after that that I actually stopped smoking, because of those letters that I had typed for him.

It was just really hard at the beginning. But after I’d been out probably for about a year, I got my feet underneath me, and moved into an apartment by myself. Met the guy across the hall. About a year later, we got married and then I had four children. And I went back to college.

I had a really, really great, psychiatrist that I had found at Mass Mental Health Center. The day before they transferred me to Westborough. And he had told me, “You don’t belong in Westborough. There’s nothing the matter with you.” And I said, “Well, they’re going to send me there. They’re going to send me there, because I’m not behaving and refusing to make my bed. I’m so mad at them.” And he said, “Well, you don’t belong there. There is nothing the matter with you. Your behavior is caused by how badly they’ve treated you in these places. There’s nothing the matter.”

And so I remembered him. I remembered his name, and I found him. And he’s the one who eventually helped me get my records. I saw him once a week or once every few weeks, just to kind of check in. And whenever I would have a baby, he would come to the hospital and see the baby. He was just great.

I’d been trying to get my records. I couldn’t get them from anywhere. It was letters back then, and I never heard back from anybody. Finally, because he was commissioner of mental health in Massachusetts, he then decided he would write a letter to the Baldpate Hospital on his fancy stationery, and say he wanted to go out there and have a meeting and see my hospital records with me. And they agreed, because how could they not? He was the commissioner. They had to agree.

So I went out there with him and we read the records, and he knew ahead of time that I was bringing a briefcase with me. And I said to him, “You know, I’m going to steal these things.” He said, “That’s okay. That’s okay. You can steal them.” First I would read a page and I would pass it over the him. So we read the entire thing, starting with me, passing over to him. About two-thirds of the way through, he said, “Now, I’m going to go to the bathroom. Do whatever you want to do.” But because he’d been so sweet all those years, he just been the kindest kindest guy, I knew that if I stole them all, he would get into trouble. And that probably wasn’t going to be a good thing for him. So I just stole every other page. I picked the worst pages, and stole every other one. The people who ran the institution, they were so stupid, they didn’t even realize. And so we had something to give back to them that was considerably lighter than what we had had been given. But nobody said a word, and I went off with what I had. And then I put them in a box in my closet. That was around 1980.

Harris: I also had this incredible desire, several years after the fact, to obtain my records. I could not obtain all of them because one of the hospitals, it was a private psychiatric chain called Charter Behavioral Health. They went under because several kids had died under their “care.” So I couldn’t get my records from them, but I did manage to get every other record that I could — mine, and I have my mother’s. For people who haven’t had this experience, I want to back up. There is something that my friend Chacku Mathai has said: “I got out of the hospital, but I’m still working on getting the hospital out of me.” And I think part of that process of “getting the hospital out of you” was, at least for me, to be able to see those records. To see what they said about me, and to understand it on a deeper level. What was that like for you? What was that drive to get a hold of those records? Why not say, “Hey, I’m just going to put this behind me?”

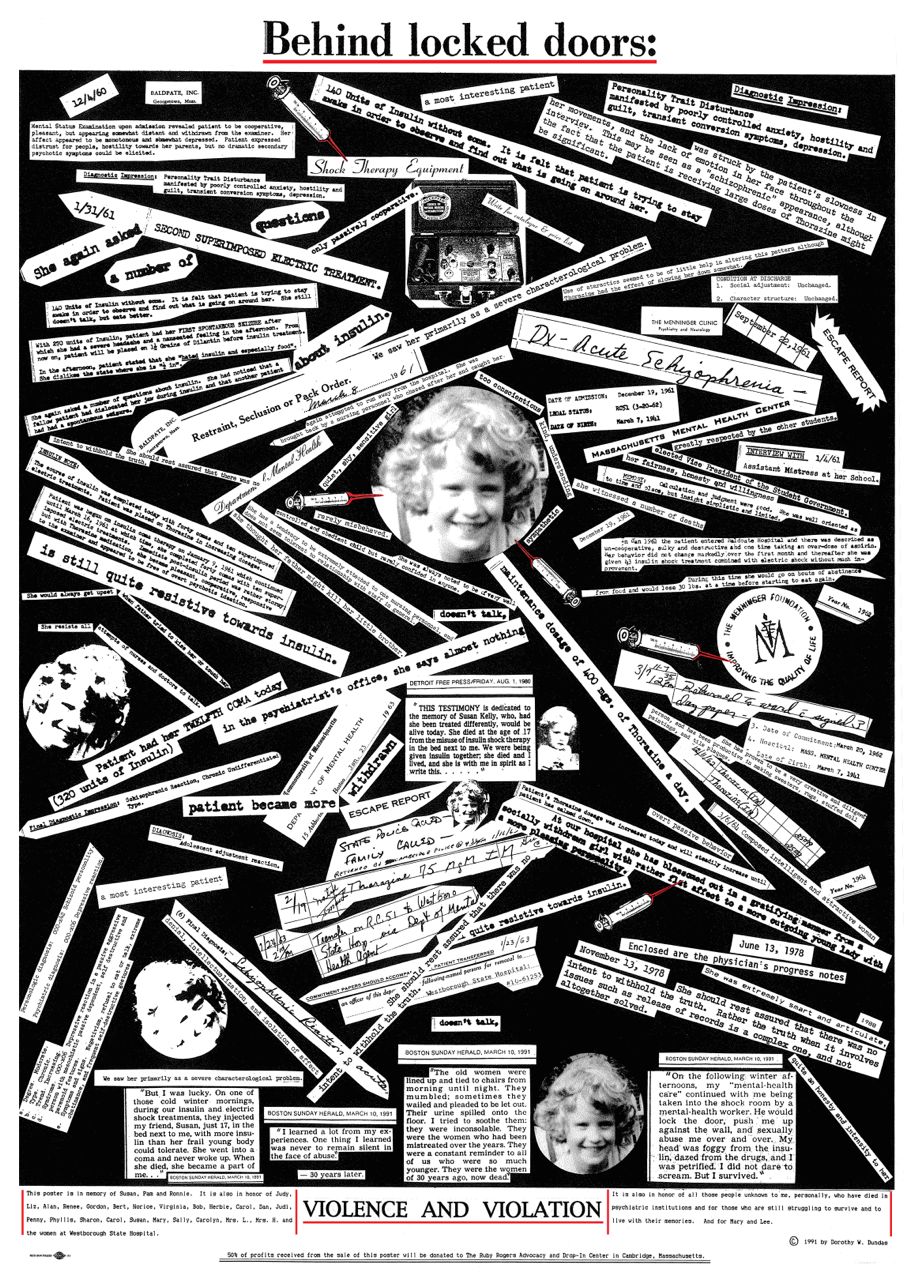

Dundas: I felt that they were me. I literally felt they were part of me and I just can’t even describe it to you. Without those records, without me being able to see those things — I knew they had said things about me that were terrible. I had to be able to see them, and see them in print. I felt like those records belong to me. They are part of me, is the best way I can describe it. Mind you, I only read the ones from Baldpate hospital where I had the shock. In other words, I was never able to get them from anywhere else at all. Nothing from Menninger. Just this tiny, stupid little short version. Nothing. But the worst language was what I put onto the poster. And it’s why I love my poster. I love selling it. I love giving it away. I love looking at it. I love everything about it.

Harris: Tell us the story of your poster. What was the political context for it? How did that poster come into being?

Dundas: It came into being because in 1991, I happened to be watching television. The Anita Hill hearings. I was so horrified by how poorly she was being treated, that I went up into my closet, and I got out my hospital records. Over the course of I think two or three days that I was watching TV when they were doing the hearings, I would look at the records, and pick out the pages I wanted to make copies of. Because back in those days you had to go to the copy shop, and they’d make copies for you while you stood there, or you left them there and you came back. And I’d make copies so that I would have duplicates of everything.

I had a vision of what I wanted. I knew exactly what I wanted. I wanted a poster. I wanted to make it as true to life as possible. With as many bad things in it, with also the little bits of the op-eds that I’d written at the bottom. And I wanted the names at the bottom of the people who had died. And I was propelled that particular moment by Anita Hill and how poorly she’d been treated. And of course, when I listened to the Kavanaugh hearings, I had the same feeling. My poster was already made. But I had the same feelings during the Kavanaugh hearings: “What in the world are they putting that woman through? That is just plain disgusting.”

Harris: I so appreciate what you say about anger. Especially as female-identified people in society, as women, our anger is so often pathologized as something that is abnormal, you know? But I love your story because you talk about how anger actually probably helped you get out of the hospital. And that anger sort of helped you to continue to sustain yourself, even in the face of how that trauma played out. Even long after you’re out of the hospital. But it sounds like for you that anger was a bit of an antidote to that trauma, and a way for you to claim your power back.

Dundas: Yes. I think it was. I think it totally was. Even though every time I expressed the anger when I was locked up, I would be given IV Thorazine, so it wasn’t allowed to last very long. So I would end up on a mattress with no sheet, in a locked room completely passed out from IV Thorazine. But still, I kept being angry, because they had locked me up against my will and did all these terrible things to me. So what was I going to do? I still am speechless when I think about it.

Harris: It’s incredible that with everything that they did to you, it didn’t put you into a place of resignation. I remember when I was locked up, even with other young people — so many of them had already given up. Which is really easy to do, because of all the disempowering messages and the things that happen to you in those places. And so I just want to say that I’m so grateful for your anger. I’m so grateful that you were able to channel it into this incredible piece of art. We will put your contact information at the end, so people can get their own copy of your poster. You are distributing them, correct?

Dundas: I am. I’ve been asking people to donate $25, and then I send them anywhere from one to ten posters, however many they want. And that pretty much covers the cost of the tubes and the postage. Or I’ve been sending ten at a time out to places like MindFreedom and then they just give them away. If people don’t have money, I’m happy to have them pay the postage through PayPal and then I send them a free poster.

But what I also wanted to say was that I learned a lot from a woman called Mrs. Lizer, who has obviously long since died, because she was quite elderly even though she was on the teenage ward. I don’t know why she was on the teenage ward, but there she was. And every single day, they would give her her breakfast tray or her lunch tray or her dinner tray and she would come out of her room, and she would march down toward the nurses’ station. She would take her tray and she would turn it upside down and dump it all over the floor and shriek and scream and say she was not going to stay there a day longer. She was not going to eat a single bite of their food. And you know what? I learned a lot from watching that. I have no idea how long she was there. She was there the whole time I was there, which was about eight months, but she’d probably been there longer, much longer. And there she was expressing her rage.

Harris: It’s like she was a model of resistance.

Dundas: She was a model of resistance and yeah, none of the other teenagers did that, but she did. And she wasn’t afraid of anything. I wasn’t afraid of them, but that’s also where I took a cigarette, and I burned a hole in my arm with the cigarette. And that was my form of resistance. And every time they would take the cigarette away, I would get one from somebody else and continued the burning. It wasn’t such a healthy thing to do. On the other hand, it helped me feel better.

Harris: And it makes so much sense because you know, you’re in a place where obviously any outward expression of anger is going to get you drugged up and harmed even more. So it would make sense that you’re sort of turning it on yourself. Right?

Dundas: Yes.

Harris: I want to come back to this resistance and the activism for a moment if we can. Let’s go back to that early connection that you had with Dan Fisher, David Oaks, and Judi Chamberlin. Tell us a little bit about that. What was the work that you all were doing together? What was the activism that you were doing? What kind of campaigns were you involved in? I know you were writing letters, and being involved in media activism, but I’d love to hear more about what those times were like. What were your meetings like? How did you decide what you were going to do, and how did you go about doing it?

Dundas: The biggest thing about the meetings was the camaraderie and the support we got from each other. Just simply being together. We’d be at Dan’s house or Judi’s house or we would be at my house, or every now and then we’d be at Brooks House at Harvard, which we got through David Oaks. And it was mostly talking. I remember we were trying to start a house, a safe house. There aren’t very many across the country, but similar to what they have in Northampton. There’s one in New York state, I think. Basically a house run by survivors without any medical personnel. Just safe places to go. Respite houses, whatever you want to call it. We were trying to start one of those and frankly, we just never succeeded.

That’s mostly what I remember about those meetings. They were emotionally supportive. It was before I ever heard of the Alternatives Conference. After a while I kind of stopped going to those meetings, because when I became a single parent, I then decided that I needed to dedicate every single minute to my children. The children took a lot of physical and emotional attention and dedication. It was the same kind of dedication that I needed to be involved as an activist. And I found it hard to do both at the same time, when the children were very young. And so I dropped out for a while and didn’t start coming back until my kids were grown. They were teenagers at that point, and even in their early twenties.

Harris: It makes so much sense, and yet you’ve always stayed connected to the movement. Something that I know about you is that yes, you spent all this time really focused on raising your children to be the wonderful, empowered adults that they are. I know several of them personally. But you never had a job in this “world.” I started off doing activism and what I did for work had nothing to do with psychiatric survivorship or any of the other sort of system-changing work that we’re trying to do. And then, a lot of folks end up getting hired, as part of the system or hired as some kind of an alternative to the system. But it does sort of change what you’re able to do sometimes, because you’re connected to an organization. There may be things you can’t say, or you’re worried about saying them. Do you feel like never actually having had a job in the movement gave you more freedom to express yourself however you needed to and not sort of hold back, toe any kind of line?

Dundas: Well, I’ll tell you. In terms of jobs, even though I’ve never had a job within the movement, I have had plenty of jobs in my life. One thing I learned from Lee Macht very, very early on — Lee Macht is the name of the guy who I’ve mentioned before, who took me to get my records. He told me long ago that when I filled out a form, I needed to not check the box, “Have you ever been in a psychiatric hospital?” I applied for a job. I checked that box. Of course, I didn’t get the job. So when I told him that, he said, “You cannot check that box.”

I said, “Well, it’s a lie. I’ve been in these places.” He said, “That’s a little white lie that’s important for you to tell. I will support you one hundred percent to lie about that, because you won’t get a job if you tell the truth.” So I taught kindergarten in the Boston public schools when I finally got out of college. There was that box when I applied for that job, and I didn’t check the box and I got the job. And I taught in the Boston public school for two years, kindergarten. And when I was raising my kids, I did daycare for other people’s children so I could stay home with my kids. And then I eventually had my own business where I could be my own boss. For 30 years, I drove a taxi, which is similar to what Uber does now. Only it was all, “Call me on the telephone or page me on my pager,” way before cell phones.

I never wanted to work in the movement. I just didn’t. I just knew that I would feel constrained, and I could not be constrained. I had had enough of that. But every now and then I’d think, “Boy, I sure do need money. Maybe I could go get a job doing something in the movement.” And I think, “Wait, wait, don’t. Don’t.” So I don’t.

Harris: In your story, I’m so struck, and this was something that I really recognize in my own story — it’s almost a sort of magical synchronicity where people showed up for you at the right time, you know, and sort of helped you to escape, and helped you to access your records. And gave you that advice to keep your hospital history on the “down low,” because they don’t need to know. All of these people who were able to sort of support you to have the kind of life that you wanted to have. When I think about you, I think about how you are so much that person for others, especially folks in our movement and especially younger people. When I got involved in this movement when I was about 25 years old, which is way long ago, you were always there supporting me and encouraging me. And just reminding me how important this work is even though it’s so hard, and you’re going into your wounds every day. What do you see as your role today in the movement and what would you like to say to younger people who are coming in behind you and behind me?

Dundas: I do see my role from way back, but especially now, especially in the last 10 years or so, I would say definitely my role is number one, to be an example to the younger people.

You can have a perfectly fabulous life after going through sheer hell — you can go through it, and you can come out on the other side. And nine times out of ten or even ten out of ten, there was never anything diagnostically the matter with you.

Most everybody’s “crazy” behavior — I love the word crazy, it’s so expressive — is very often a completely normal response to whatever is happening in your life at the moment. And so I really, really want to be an example to other people, and just be supportive of all the young people. I feel like I have a lot of daughters in this movement. And I have some sons. And you’re one of my daughters, Leah.

Harris: And you’re one of my “movement mamas!”

Dundas: Oh my gosh, it’s so moving. Anyway, I just would say to the people coming along after us: Number one, believe in yourself. Don’t believe in any of the diagnostic labels that were slapped on you, because they’re not true. And just put one foot in front of the other and know that you will come out on the other side, even if you’re feeling just absolutely dreadful. Just know that you can do it. Just to give people hope, I think, is a really important thing.

Harris: And you do that. Every day, I see you doing that. And you are incredibly active on social media, posting and sharing information, but also supporting folks and being that role of the “movement mama,” the supporter, and the agitator.

Is there anything else that you would like the listeners to know? Any stories, anything that you want to share, by way of closing as you reflect on the incredible work and everything that you continue to contribute to this movement?

Dundas: I think I would like to give special thanks to all of my children in this movement, because I really love you all. And I also would like to give another special thanks to Bob Whitaker. When I first read Mad in America, one of his first books, I read it and I found my story in there. He was in Cambridge and I found him somehow and I said, “I need to have lunch with you, I need to have dinner with you, coffee with you, something!” And he had lunch with me. He could not have been more lovely to me. So he is somebody that I have always wanted to thank. And I have thanked him.

And all of the people that I’ve had to dinner at my house. We had had group dinners at my house over the years, and I’ve now decided it’s time to pass those dinners on to somebody else. I’ve been hosting them for five years, and I let some of the people know that it’s time for someone else to take that over.

I also very much appreciate the time I spent at the Esalen Institute, which was two donated weeks for me to spend there with other mental health people, trying to change the system. And I met a lot of new people there that I had never met before. There’s been significant people in the movement who are not necessarily survivors in the same way that I’m a survivor. But I think the important thing to remember is that most people in this world are survivors of something. Our particular situation is unique to us, but many of these people who’ve given back to people like us have also had their own difficult times to live through. And so I’d like to thank all of them as well.

Harris: I know every single one of them would thank you right back, myself included. What I really take away from your story is yes, the activism is the work that we do to try to change the system and raise awareness, or call out harmful ways of working with people and create something new in their place. And another piece of the activism is that even though there’s conflict and challenges in every movement, it’s how we are with one another, right? In our survivorship. And it’s never perfect. But I hear in your story that those connections are also activism. Finding each other, connecting with each other, staying connected. How can people who would like to reach you get a hold of you? What are the best ways to do that, whether that’s email or social media? You have your poster up online?

Dundas: It’s on my Facebook page and it’s in a Mad in America blog. The blog is about how I made the poster. As well as two videos: a video of me speaking out at a protest in New York City and another video of the details of what happened to me. They can also get in touch with me through Facebook Messenger.

Harris: Fantastic. We’ll put that in the show notes so people can find you, if they want to reach out to you and learn more about you and what you’re doing.

Dundas: Thank you so much. I really appreciate this. Because as you know, Bernie Sanders had a heart attack. Bernie and I are the same age — 78, maybe he’s 79. But he had a heart attack, and that is what suddenly made me start to think about, “Oh my God, I have to get these posters out immediately, so my poor children don’t find them under my bed, and have to figure out what to do with them.”

Harris: Well, you and Bernie are going to be with us much longer. I insist on it.

Dundas: Thank you, honey.

Harris: And thank you so much again. Thank you for being on the podcast and thank you for all you do.

Dundas: You’re very welcome.

Links:

Dorothy Dundas author page at Mad in America

“Behind Locked Doors: How I Got My Hospital Records, and What I Did With Them” by Dorothy Dundas

To contact Dorothy and/or to order a “Behind Locked Doors” poster

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Sometimes I read articles on MIA and I’m so “intimidated” by the writer or interviewer that I don’t comment. I make an exception in your case and will just wing it, because you really look like my aunt. Thank you for this wonderful interview and example of the silver lining of anger. I’m happy you were angry, that it helped you survive and that you shared all that with us. I can’t beleive they treat human beings as they do and I pray that we can stop that abuse by institutions (without resorting to bombs). I’m also grateful that you have a better typewriter. “Thanks” isn’t enough.

Report comment

Thank you, Redcat.

Report comment

Well, surviving is always good, and resistance is better. But it’s important to keep in mind that “protest” is basically complaining to or about those in power, and “resistance” is akin to leaning against the door to hold back the storm. We need to go beyond resistance and take the offensive in our endeavors to bring a complete halt to the machinery of the psychiatric system.

Report comment

Yes, oldhead. Very true.

Report comment

Glad we’re on the same basic page. Congrats on “surviving” btw. 🙂

Report comment

Thank you for speaking out against the fraud and harm that our “mental health” workers are participating in, ladies. I agree, picking up one’s medical records and reading all the misinformation that is written within them is highly enlightening. And pointing out all the misinformation written within my medical records was staggeringly embarrassing for my psychiatrist. So much so, that he declared my entire life to be a “credible fictional story,” so I had to leave him.

I agree with old head, we need to “bring a complete halt to the machinery of the psychiatric system.” Because, in Allen Frances’ words, “it’s bullshit.”

Report comment

Thank you, Someone Else.

Report comment

Boy, if ever there’s been a survivor in life, it’s Dorothy! Way to go!

I found it quite intriguing that Dorothy was able to get her op-eds and letters-to-the-editor published by the Boston Globe. When was that; back in the 1960’s? I’ve never had that kind of luck with any of the publications I’ve submitted to; censorship is the name of the game. If it was in the ’60’s that Dorothy was published, it’s interesting to see how the hatred of us has intensified since then. I had no luck whatsoever getting any of my vignettes published, including at the great Rolling Stone Magazine! And, believe me, this wasn’t because I’m not a good writer!

Report comment

Thank you, kumininexile. My op-eds were published in 1979-81. Also in the Detroit Free Press and The Miami Herald. I sent out many, many paper envelopes filled with my writing to many newspapers all over the country which had over 100,000 subscribers. I was lucky.

Report comment

Same here, you find the medical proof that even “schizophrenia” is an iatrogenic illness. Both negative and positive symptoms created with the “gold standard treatments,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome and anticholinergic toxidrome. And that’s NOT news!

That’s why we need to end direct to consumer advertising. Our media outlets are controlled by their pharmaceutical advertisers – and “censorship is the name of the game.”

Report comment

Thank you for your comment, Someone Else.

Report comment

“You can have a perfectly fabulous life after going through sheer hell — you can go through it, and you can come out on the other side.”

Thank you for those words. I’ve heard them before, but NEVER from someone who would completely understand what it is to try to get your footing back after escaping. I too had the internal urge to get my medical records. I only got them from one hospital, the others wanted to charge me and due to their “treatment ” I am not working yet, therefore could not afford the proof. For me, my records were the thing that confirmed that I was not lying or exaggerating concerning the torture I suffered through. I also feel that my anger at being locked up for no valid reason, in my opinion, just a child sex abuse victim with depression, saved my life. My anger protected me from being completely brainwashed, although they did try hard and I was falling into it at times.

I say this all to say thank you. Thank you for sparking that hope in me that I can be more than a mother again. That I can actually maybe one day , WANT to be here for more than just making sure my kiddo is safe. Thank you….

Report comment

Thank you for your moving comment, psmama. Never give up and never be afraid to speak out! Good luck!

Report comment

Hello, Dorothy and Leah,

I want to thank you both from the bottom of my heart. Your interview was a boost of energy in a moment when I surely needed it.

Thank you, thank you, thank you, both, for being who you are and doing what you do.

With much love and appreciation,

Jim Probert

Report comment

With heartfelt thanks for your kind comment, Jim.

Report comment

I agree. Don’t check the box. Don’t admit it. Don’t even imply it. Interestingly, since the diagnoses have no validity, if you don’t tell, if you act as if you were never locked up, as if you never had a diagnosis, no one will know. If you tell the wrong people, they won’t just run away, they’ll do anything to smear your reputation. You will become a scapegoat. People need someone to hate, someone to blame for their own flaws and mistakes.

I agree that the hatred out there is worse than ever. I have had a lot of trouble getting the attention of journalists and nothing I write to the Boston Globe even gets read.

Report comment

All mass murderers are supposedly “mentally ill.’

Good and evil are unacceptable words now. By blaming a select group for all the vices of humanity, the mainstream absolves itself.

And it sounds so SCIENTIFIC. 😛

Report comment

Very true, Rachel777

Report comment

Thank you, Julie Greene. All that you say is true. And, I also haven’t had anything published for years.

Report comment

Dorothy, thank you so much for sharing your story. It was helpful. So many times and in so many ways one has to live in the closet. I have tried several ways to integrate my psych life experience with life outside and most times it has not gone well. Either there is a cold draft that creeps into the air or silence. Most folks really don’t want to know.

This is similar but not totally like females and or mothers with addiction issues. The elephant in the living room.

In my area the 12 step groups have been alive and kicking and some of my own support has come from there but not always and still a separate issue.

Not being able to tell my children oh you need to talk to my friend so and so because she lived through what you did with me is a great sorrow and I am not sure how much it is because I still own the shame and humiliation.

There is no good manners, etiquette framework to discuss this issues and other crisis episodes of human life. I think we have all been in places where a brave soul brings up something and then silence and a quick change of subject.

And I think we psych survivors are not the only hurting hidden humans here.

When I was in a Preschool Board one of the mothers lost a child. No one expected her to come but she did and only one mother was able to meet her eye to eye and greet her( A LISW I knew- so yes so some profs can rise to the occasion) .

That mother and I became great friends unfortunately she died of cancer and was not alive( trauma anyone?) when I slid , was pushed, into crisis.

Thanks again, your voice is so important.

Actually there is an old book and a movie on a psych survivor story written by a fellow high school alum though more addiction than anything else but she was in our local unit. The Cracker Factory- FYI

Report comment

Thank you, CatNight. I shall find that book.

Report comment

Hi Dorothy,

Thanks for continuing to speak out about the abuses that are being disguised as ‘medicine’. I remember reading one of your articles some time back now regarding your access to documents, and the struggle I was having in understanding the ones I had at that time (redacted).

I like the comments made above about hatred of the truth. It was when I tracked my documents back after being confused about why ‘my’ lawyers could not assist me that I found out the hospital had supplied them with a fraudulent set. Unless of course taking the documents that contain the fact that I had been ‘spiked’ with benzodiazepines without my knowledge out, and replacing them with others creating the appearance that I was a “patient” of this hospital for more than ten years is considered “editing”. I think the correct term is fraud given the flustered response from authorities when I turned up in a police station with the documented truth. Not that it helped, they were going to arrest me for having them despite not being able to tell me what the charge would be. Once its a crime to report the crimes of your government the way I figure it it’s hard to call it a democracy anymore. More a totalitarian dictatorship, but they did call fraud editing too sooo. And as long as they are selling off our National assets to purchase weapons I guess they will maintain their control.

Anyway, the ‘update’ is that they have been brought the truth, but they hate it and so continue to conceal it with falsehoods. I read that “Men can not settle the high affairs of the Universe. If they plot against the Truth, the Truth will destroy them, just as if they accept the Truth it will make them free.” Okay, so I haven’t seen my daughter or grandchildren for 8 years as a result of these frauds and slanderers. Thats a short time when I consider how long they will be tasting the fire in Hell.

Their secrets and private counsels have been recorded in these documents, and will bear witness to their crimes on the day of Judgement. Your posters should make certain people very afraid. Bearing false witness is a serious matter, and knowing it has been done and not correcting the error stands right alongside it.

Still, these are the same people who saw the systematic abuse of children in institutions as being “character flaws” rather than criminal offences and allowed hundreds of children to be sexually assaulted. And I expect them to do something about me being abused? I see what they mean about my need for ‘treatment’ lol. It saves them having to face the truth that they are torturers and kidnappers (unless they can prove I was actually a “patient” which is impossible given that it is not true and has only been achieved via fraud Note they even tried to have me go to a doctor and get a referral backdated to make me into a “patient” post hoc)

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chelmsford_Royal_Commission

This would have continued if it weren’t for people telling their stories, and someone with morals ensuring it wasn’t buried by putting pressure on politicians to keep their promises. Keep telling your story Dorothy.

Report comment

Thank you, Boans.

Report comment

Dorothy and Leah, Thank you for this podcast and for all your work and advocacy. Dorothy your story is gut wrenching. You have incredible strength and resilience to have endured these barbaric psych practices at such a young age and then actually witnessed your young roommate Susan die from these barbaric practices. I deeply admire your advocacy and for speaking out against psychiatry to help others. I had naively agreed to see a psychiatrist for chemo-induced insomnia and ended up paying a huge price for being naïve. Like many of the general public I had no idea of the damage psychiatry inflicts on innocent people and was shocked to discover psychiatry wields ultimate power and control. Psychiatry is a total sham – but the word of psychiatry somehow rules supreme over every other branch of ‘real’ medicine. I cannot wrap my brain around that. It wasn’t until I found the MIA site that I realized how extensive the damage of psychiatry was. Thank you for still speaking out after all these years and for all your endeavors to help others avoid similar fates. God bless you sweet lady!

Report comment

Thank you, Rosalee.

Report comment

Hi Rosalee, Isn’t it amazing that you are experiencing their “hatred” for just being here? We can look back and remember the times we looked at ‘those people’, the ones who we thought of as MI, yet here we are discovering that we saw distress and we now know that if psychiatry can use their hate crimes on someone needing sleep, how much more hateful are they with those in visible distress.

I don’t just see getting rid of psychiatry, I want to see them brought to trial for inflicting, infecting society with their pathogens. There are still some Psychiatrists who believe they are doing good or better, and have the public believing the crap that they spew. I honestly don’t care how much insight a shrink has, they still remain part of the problem. If he cannot get you out of the rabbit hole, if no lawyers are willing to step in, they all remain part of what psychiatry does for a living. And that guy that gives people a heart surgery, that ER doc, they all are part of the club. It’s sheer power exposes it’s danger. No entity should have this much power.

Report comment

Dorthy Dundas: Thank you very much for your harrowing story. Whats sad is you just needed someone to talk to. Your suicide attempt was a cry for help and you were castigated and tortured. Don’t you think we should be listening to people who have distress, especially when they are young? It seems to me the whole psychiatric establishment is about silencing people. I really needed help to cope with early childhood trauma and instead I was ignored and drugged. It felt so invalidating, because I wanted help to understand and prevent my troubling experiences and they offered nothing.

Report comment

Thank you for your comment, Lockjaw. Yes, the system hurts so many people. Kindness and patience can go a long way to helping people heal.

Report comment

Lockjaw, I just wanted to say, I Hear You! When we were kids, they should have listened instead of shutting us up any way possible. I’m sorry you experienced that heartlessness in your time of need too…

Report comment

Thank you, psmama!

Report comment

Thank you Leah, thank you Dorothy. In awe. My life, your life, our lives are not here for the obsessed, defensive, egotistical, fearful minds of psychiatry to be the object of their dark lying existence.

Report comment

Thank you, Sam Plover!

Report comment

Documents

My legal representative writes to the Chief Psychiatrist

“We submit that the time taken to provide access to our clients medical records was unreasonable, and prevented Mr Boans from obtaining legal advice and assistance from the Mental Health Law Centre” and “The copies of the medical records were provided to the Mental Health Law Centre in “edited form” with sections blacked out”.

Not only were sections blacked out the documents that demonstrated that I had been subjected to torture and kidnapped were removed and other documents put in their place. It took some time to figure that out. So whilst the government has procedures in place to ensure your human rights are observed (ie provision of docs to lawyers in a timely manner) they have managed to delay me obtaining these documents for 5 years. And in the meantime distributed fraudulent documents and released confidential information to the public. How nasty do these people get.

I’m assuming those who know the system would understand why 5 years to obtain access to your file by a lawyer might be a problem?

I am told by a lawyer at S+G that its too late now. They won’t assist and sorry but its like with the child raping priests, we sit on our hands and deny access to legal rep while they rack up the victims. I’m sure their consciences are clean. And well, the conflict of interest regarding the legal/medico report wouldn’t have had an influence, i’m sure no favour will be sought from the Private Clinic Psychiatrist.

Letter from the Chief Psychiatrist says he gets the impression that the documents were applied for under thew FOI Act, despite having been provided with the letters of application bolded with Application for documents under the MHA Act s. 160/1. It did however once again ensure this torturer was enabled for well, another 8 years now. I’d call that criminal negligence but police don’t have a copy of the criminal code and threaten peoples families so ……

The problem was always with the hospital having to write to the lawyers and ask them to engage in a criminal conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. Got to be careful putting that sort of thing in writing. “Hi, we can’t give you these documents unless you swear to not tell anyone we are torturing and kidnapping cirtizens and using police resources to do it, agreed?” Especially with regards offences such as torture and kidnapping and no good faith defense. Mind you killing people who complain seems a bit rich. Or “unintended negative outcoming” as the Chief Psychiatrist prefers to call them.

Report comment

I must admit that I wonder about the diffusion of responsibility where thse matters have been concerned. No one wants to deal with the organised criminals operating in our hospitals and they hand ball resposibility to any othe rbody they can. The Office of the Chief Psychiatrist passes to AHPRA and HaDSCO. AHPRA says its out of their brief and well fortunately the guy at HaDSCO was an ex police officer and actually knew some of the police who had been assisting these criminals. Biut of a laugh his ex colleagues handing someone over to criminals to be killed lol. He recommends going to police integrity, but they just hand ball back to ‘medical’ authorites. And in the confusion I am almost murdered in an ED and they still haven’t figured out whats going on. Too busy making it someone elses business.

And the public are simply too afraid of our government these days given the amount of police corruption and enabaling of organised criminals in our hospitals to dare stand up and say anything. They’ll do your family.

So the crooks are on a good wicket, and a bit like to folk who stood and watched Kitty Genovese murdered they stand and watch assuming someone else will do something about it. Anyway, i’m off to lunch lol.

Lucky that one person recognised what they were going to do to me and was waiting in the next cubicle in the ED. Should have seen that doctors face caught in the middle of attempting to murder someone lmao. Shame you have to rely on that though because the authorities don’t give a damn and are asleep at the wheel.

Report comment

Thank you, boans.

Report comment

Thank you, boans. it is so frustrating. I was lucky to get at least some of my records.

Report comment