Editor’s Note: Over the course of several months, Mad in America is publishing a serialized version of Peter Gøtzsche’s book, Mental Health Survival Kit and Withdrawal from Psychiatric Drugs. In this blog, he discusses the risk of suicide and other causes of death from psychiatric drugs, focusing on depression pills. Each Monday, a new section of the book is published, and all chapters are archived here.

Suicides, other deaths, and other serious harms

Depression pills

Depression pills are the poster child for psychiatry, the pills we hear most about, and the pills which are most used, in some countries by more than 10% of the population.

As noted, it is one of psychiatry’s best kept secrets that the psychiatrists kill many patients with neuroleptics. Another well-kept secret is that they also kill many patients with depression pills, e.g. elderly patients who lose balance and break their hip.4,96

The psychiatrists have fought really hard to hide the terrible truth that depression pills double the risk of suicide, not only in children but also in adults.2,4,97-100 The placebo-controlled trials are hugely misleading in this respect, and a lot has been written about how drug companies have hidden suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviour, suicide attempts, and completed suicides in their published trial reports, either by wiping the events under the carpet for no one to see, or by calling them something else.2,4,101

This massive fraud is routine in drug companies. I devoted a huge part to the fraud in my 2015 psychiatry book,4 and shall therefore only mention some recent research results here.

My research group found that, compared to placebo, depression pills double the occurrence of FDA-defined precursor events for suicide and violence in healthy adult volunteers;97 that they increase aggression in children and adolescents 2-3 times,55 a very important finding considering the many school shootings where the killers were on depression pills; and that they increase the risk of suicide and violence by 4-5 times in middle-aged women with stress urinary incontinence, judged by FDA-defined precursor events.98 Furthermore, twice as many women experienced a core or potential psychotic event.98

Psychiatrists dismiss research results that go against their interests. They have also criticised our use of precursor events, but there is nothing wrong with this. Using precursor events to suicide and violence is similar to using prognostic factors for heart disease. As smoking and inactivity increase the risk of heart attacks, we recommend people to stop smoking and to start exercising.

It is cruel that most psychiatric leaders say—even on national TV102—that depression pills can be given safely to children because there wasn’t a statistically significant increase in suicides in the trials, only in suicidal thoughts and behaviour, as if there is no relation between the two.4 The psychiatrists reward the companies for their fraud while they sacrifice the children. We all know that a suicide starts with suicidal thinking followed by preparations and one or more attempts.

A US psychiatrist who argued that suicidal behaviour should not count because it is “an unvalidated, inappropriate surrogate” contradicted himself, as he wrote in the same paper that, “A history of a prior suicide attempt is one of the strongest predictors of completed suicide,” and also wrote that the rate of suicide is 30 times greater in previous attempters than in non-attempters.103 This is full-blown cognitive dissonance with deadly consequences for our children.

When I wrote my 2015 book, it became clear to me that suicides must be increased not only in children, but also in adults, but the many analyses and reports were confusing with some having found this and others not.4

The crux of the matter is that many suicide attempts and suicides are left out in reports. In 2019, I found additional evidence of this, when I compared a trial publication104 with the corresponding 1008-page clinical study report submitted to drug regulators.105 The authors of the published report did not mention that two of 48 children on fluoxetine attempted suicide versus none of 48 children on placebo.

The first author, Graham Emslie, falsely attributed the funding of the trial to the US National Institute of Mental Health, but FDA data showed that the study was sponsored by the manufacturer of fluoxetine, Eli Lilly.106

Suicide attempts and suicides are not only concealed during the trial. Most often, they are also omitted when they occur just after the randomised phase is over:4

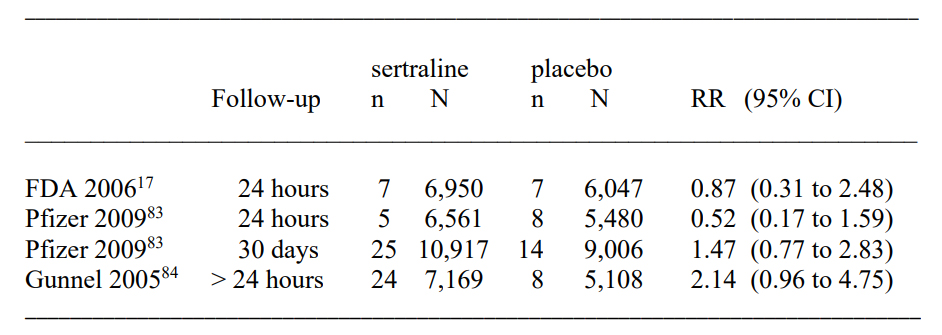

Sertraline trials in adults; n: number of suicides and suicide attempts; N: number of patients; follow-up: time after the randomised phase ended; RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval.

When the FDA did a meta-analysis of sertraline used in adults (Table 30 in their report),107 they did not find an increase in suicide, suicide attempt, or self-harm combined (risk ratio 0.87, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.48).

Pfizer’s own meta-analysis found a halving of the suicidal events when all events that occurred later than 24 hours after the randomised phase stopped were omitted.108 However, when Pfizer included events occurring up to 30 days later, there was an increase in suicidality events of about 50%.

A 2005 meta-analysis conducted by independent researchers using UK drug regulator data found a doubling in suicide or self-harm when events after 24 hours were included.109 These researchers noted that the companies had underreported the suicide risk in their trials, and they also found that nonfatal self-harm and suicidality were seriously underreported compared to reported suicides.

Another meta-analysis carried out in 2005 by independent researchers of the published trials was very large, as it included all drugs (87,650 patients) and all ages.110 It found double the amount of suicide attempts on drug than on placebo, odds ratio (which is the same as risk ratio when events are rare) 2.28, 95% CI 1.14 to 4.55.

The investigators reported that many suicide attempts must have been missing. Some of the trial investigators had responded to them that there were suicide attempts they had not reported, while others replied that they didn’t even look for them. Further, events occurring shortly after active treatment was stopped were not counted.

The reason it is so important to include suicidal events that occur after the randomised phase is over is that it reflects much better what happens in real life rather than in a tightly controlled trial where the investigators motivate the patients to take every single dose of the trial drug. In real life, patients miss doses because they forget to take the pills to work, school, or a weekend stay, or they introduce a drug holiday because the pills have prevented them from having sex (see below).

It differs from trial to trial what happens when it is over. Sometimes, the patients are offered active treatment, sometimes only the treated patients continue with active treatment, and sometimes there is no treatment.

In 2019, two European researchers finally put an end to the psychiatrists’ fierce denial that depression pills are also dangerous for adults. They re-analysed FDA data and included harms occurring during follow-up.99 They were criticised and published additional analyses.100 Like other researchers, they found that suicide events had been manipulated, e.g. “Two suicides erroneously recorded in the placebo group from the paroxetine approval program removed.”100 They reported twice as many suicides in the active groups than in the placebo groups, odds ratio 2.48 (95% CI 1.13 to 5.44).

There should be no more debate about whether depression pills cause suicides at all ages. They do. Even the FDA, which has done it utmost to protect drug companies marketing depression pills,2,4 was forced to give in when it admitted in 2007, at least indirectly, that depression pills can cause suicide at any age:4,111

“All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases. The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants … Families and caregivers of patients should be advised to look for the emergence of such symptoms on a day-to-day basis, since changes may be abrupt.”

The FDA finally admitted that depression pills can cause madness at all ages and that the drugs are very dangerous—otherwise daily monitoring wouldn’t be needed. It needs to be said, however, that daily monitoring is a fake fix of a deadly drug problem. People cannot be monitored every minute, and many have killed themselves with violent means, e.g. hanging, shooting, stabbing, or jumping in front of a train, shortly after they seemed to be perfectly fine to their loved ones.2,4

But the organised denial continues undeterred.4 Two years after FDA’s announcement, the Australian government stated: “The term suicidality covers suicidal ideation (serious thoughts about taking one’s own life), suicide plans and suicide attempts. People who experience suicidal ideation and make suicide plans are at increased risk of suicide attempts, and people who experience all forms of suicidal thoughts and behaviours are at greater risk of completing suicide.”112

True, but why did suicidality not include suicide? If you want to find out how dangerous mountaineering is, and you include injuries when people have serious thoughts about climbing mountains and attend a fitness centre, and injuries when they plan to climb a mountain and when they attempt to do so, would you then exclude deaths due to falls? Of course, you wouldn’t, but this was what the Australian government did. They showed the lifetime prevalence of suicidality, divided into suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempt, but there were no data on suicides.112

There is a long way to go. In our review of 39 popular websites in 10 countries, which we carried out in 2018, we found that 25 stated that depression pills may cause increased suicidal ideation, but 23 (92%) of them contained incorrect information, and only two (5%) websites noted that the suicide risk is increased in people of all ages.32

Depression pills can cause violence and homicide.2,4 But this is also one of psychiatry’s well-guarded secrets. Particularly in the USA, psychiatrists and authorities won’t tell the public if the perpetrator was on a depression pill. It can take a long time and involve Freedom of Information requests or lawsuits before anything gets revealed.

It took quite a while before we learned that the Germanwings pilot who took a whole plane with him when he committed suicide in the Alps, and that the Belgian bus driver who killed many children by driving his bus into a wall, also in the Alps, were both on a depression pill.

Even though we suspected serious underreporting of harms in the clinical study reports we examined—some outcomes appeared only in individual patient listings in appendices, which we had for only 32 of our 70 trials, and we didn’t have case report forms for any of the trials—we found alarming events, which you will never see in publications in medical journals.55 Here are some examples:

- Four deaths were misreported by the company, in all cases favouring the active drug.

- A patient receiving venlafaxine attempted suicide by strangulation without forewarning and died five days later in hospital. Although the suicide attempt occurred on day 21 out of the 56 days of randomised treatment, the death was called a post-study event as it occurred in hospital and treatment had been discontinued because of the suicide attempt.

- Although patient narratives or individual patient listings showed they were suicide attempts, 27 of 62 such attempts were coded as “emotional lability” or “worsening depression,” which is what you see in publications, not the suicide attempts.

- One suicide attempt (intentional overdose with paracetamol in a patient on fluoxetine) was described in the adverse events tables as “elevated liver enzymes,” which is what you get if you drink a little alcohol.

- It is of particular relevance for the many school shootings that the following events for 11 patients on a depression pill were listed under “aggression” in patient narratives for serious adverse events: homicidal threat, homicidal ideation, assault, sexual molestation, a threat to take a gun to school, damage to property, punching household items, aggressive assault, verbally abusive and aggressive threats, and belligerence.

Akathisia is a horrible feeling of inner restlessness, which increases the risk of suicide, violence, and homicide. We could only identify akathisia if we had access to the verbatim terms, but we nonetheless found that, like aggression, akathisia was seen twice as often on the pills than on placebo.

In three sertraline trials where we had access to both the verbatim and the coded preferred terms, akathisia was coded as “hyperkinesia,” and miscoding seemed to have been prevalent also in paroxetine trials since we didn’t find a single case of akathisia.

For Eli Lilly’s drugs, fluoxetine and duloxetine, we compared our findings with the summary trial reports that are available on the company’s website. In most cases, adverse events were only shown if they occurred in, for example, at least 5% of the patients. In this way, the companies may avoid reporting many serious harms. We found that suicidal events and harms increasing the risk of violence were seriously underreported:

Only 2 of 20 suicide attempts (17 on drug vs 3 on placebo) were documented. None of 14 suicidal ideation events (11 vs 3) were mentioned. Only 3 akathisia events (15 vs 2) were mentioned.

Akathisia is also seen with other psychiatric drugs, e.g. neuroleptics (see below). Akathisia is a Greek word and means inability to sit still. Patients with akathisia may behave in an agitated manner, which they cannot control, and they can experience unbearable rage, delusions, and disassociation.80 They may endlessly pace, fidget in their chairs, and wring their hands—which have been described as actions that reflect an inner torment.1

Akathisia need not have visible symptoms but can be extreme inner anxiety and restlessness, which is how this harm is described in the product information for Zyprexa. In one study, 79% of mentally ill patients who had tried to kill themselves suffered from akathisia.1 Another study reported that half of all fights at a psychiatric ward were related to akathisia,5,113 and a third study found that 64 moderate-to-high doses of haloperidol, a neuroleptic, made half the patients markedly more aggressive, sometimes to the point of wanting to kill their psychiatrists.1

Since depression pills have purely symptomatic effects and many harms, it is highly relevant to find out what the patients think about them when they weigh the benefits against the harms. They do this when deciding whether to continue in a trial till the end or to drop out of it.

It was huge work to study drop-outs in the placebo-controlled trials. We included 71 clinical study reports we had obtained from the European and UK medical agencies, which had information on 73 trials and 18,426 patients. No one, apart from my research group, had ever read the 67,319 pages about these trials before, which amount to 7 meters tall if stacked. But it was well worth the effort; 12% more patients dropped out while on drug than while on placebo.114

This is a terribly important result. The psychiatrists’ view is that depression pills do more good than harm,4 and the patients’ view is the opposite. The patients preferred placebo even though some of them were harmed by cold turkey effects. That means that the drugs are even worse than found in the cold turkey trials.

Because we had access to detailed data, we could include patients in our analyses that the investigators had excluded, e.g. because some measurements had not been made. Our result is unique and reliable, in contrast to previous reviews using mostly published data. They failed to find more dropouts on drugs than on placebo,114 e.g. a large review of 40 trials (6391 patients) reported that dropouts were the same (relative risk 0.99) when paroxetine was compared with placebo.

Next, we decided to look at quality of life in the same trials. Given our result for dropouts, the tiny benefit of depression pills that lacks any relevance for the patients, and the pills’ many and frequent harms, we expected that quality of life would be worse on pills than on placebo.

We were perhaps a bit naïve, because we had now come too close to the secrets of depression pills. What we found—or rather didn’t find—was shocking.115 The reporting of health-related quality of life was virtually non-existent.

In five trials, it was unclear which instrument was used and no results were available. We included 15 trials (4,717 patients and 19,015 pages of study reports), a substantial amount of data on which to base conclusions. However, nine of the 15 clinical study reports displayed selective reporting, and in the companies’ online registers, there was selective reporting for all 15 trials. We received 20 publications from Eli Lilly and retrieved six from the GlaxoSmithKline register. There was selective reporting in 24 of the 26 publications. Despite this extensive selective reporting, we found only small differences between drug and placebo.

This was more than a roadblock; it was sabotage. The companies are obliged to ensure that what they submit to drug regulators to obtain marketing approval is an honest account of what happened, and that important data or information have not been left out. We wondered why the drug regulators had not asked the companies for the missing data.

The pills that destroy your sex life are called happy pills

In the upside-down world of psychiatry, the pills that destroy your sex life are called happy pills. Half of the patients who had a normal sex life before they started on a depression pill will have their sex life disturbed or made impossible.4,116 The sexual disturbances can become permanent and when the patients find out that they will never again be able to have intercourse (e.g. because of impotence), some kill themselves.117,118

When I lectured for Australian child psychiatrists in 2015, one of them said he knew three teenagers taking depression pills who had attempted suicide because they couldn’t get an erection the first time they tried to have sex.

It is so cruel. And yet, the professional denial is widespread. The patients are often humiliated or ignored by their doctors who refuse to believe them. Some patients are told that such complications from taking depression pills are impossible, and others are put on neuroleptics after having been told that their problem is psychosomatic.118

One patient who had sent a couple of links to studies and reviews about post-SSRI sexual dysfunction received this reply: “If you wish to have such ‘syndrome’ continue what you are doing … read obscure studies and reviews in obscure databases and I can guarantee you that you will have it till the end of your life!”

By far most patients who are on a depression pill will feel something has changed in their genitals, and many complain that long after they came off the pills, their emotions continue to be numbed; they also don’t care about life or other people like they did before the pills.

Psychiatry professor David Healy has told me that some patients can rub chili paste into their genitals and not feel it. In his work as an expert witness, he has seen data no one outside the drug industry has ever seen, which are sealed as soon as the company settles out of court with the victims. Healy has described that, in some unpublished phase 1 trials, which are performed before a drug is tested in patients, over half of healthy volunteers had severe sexual dysfunction that in some cases lasted after treatment stopped.119

The numbness of the genitals is used in marketing. The depression pill Priligy (dapoxetine) has been approved in the European Union for treating premature ejaculation.

It is interesting to contrast this with the information provided in package inserts, e.g. for Prozac (fluoxetine).120 Right from the start, it puts the blame on the patient rather than on the drug: “changes in sexual desire, sexual performance, and sexual satisfaction often occur as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder.” Accordingly, an FDA scientist found out that SmithKline Beecham had hidden sexual problems with paroxetine by blaming the patients, e.g. female anorgasmia was coded as “Female Genital Disorder.”121

Healy sent a petition to Guido Rasi, the director of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in June 2019 signed by a large group of clinicians and researchers. EMA indicated they would ask companies to mention enduring sexual dysfunction in the labels of depression pills. Six months later, Healy sent a new letter to Rasi stating that the drug agencies had responded that these conditions might stem from the illness rather than the treatment.

He added: “Melancholia, which is very rare, can lead to lowered libido but the kind of depression for which SSRIs are given does not lower libido. Indeed, just like people comfort eat when they have ‘nerves’ so they often have more sex in an attempt to handle their ‘depression.’”

In its package insert,120 Eli Lilly stated that, “some evidence suggests that SSRIs can cause such untoward sexual experiences.” It is not some evidence. When you look at all the evidence, it becomes abundantly clear that these drugs ruin people’s sex lives.

Lilly’s denial mode continues: “Reliable estimates of the incidence and severity of untoward experiences involving sexual desire, performance, and satisfaction are difficult to obtain, however, in part because patients and physicians may be reluctant to discuss them.” Since we have this evidence, what is then the problem Lilly has in acknowledging what it shows?

In Lilly’s trials,120 “decreased libido was the only sexual side effect reported by at least 2% of patients taking fluoxetine (4% fluoxetine, <1% placebo).” If you don’t ask, you won’t see the problems. In a carefully conducted study, 57% of 1,022 people who had a normal sex life before they came on a depression pill experienced decreased libido; 57% had delayed orgasm or ejaculation; 46% no orgasm or ejaculation; and 31% had erectile dysfunction or decreased vaginal lubrication.116

There was nothing about this in Lilly’s package insert apart from: “There have been spontaneous reports in women taking fluoxetine of orgasmic dysfunction, including anorgasmia. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies examining sexual dysfunction with fluoxetine treatment. Symptoms of sexual dysfunction occasionally persist after discontinuation of fluoxetine treatment.”

Some package inserts are more truthful, e.g. for venlafaxine:122 decreased libido 2%, abnormal ejaculation/orgasm 12%, impotence 6%, and orgasm disturbance 2%. But this is still far from the truth.

- If you feel depressed, don’t go to your doctor who will very likely prescribe a depression pill for you.

- Never accept treatment with a depression pill. It is likely to make your life more miserable.

- Don’t believe anything doctors tell you about depression pills. It is highly likely to be wrong.

- Depression pills are dangerous. They increase the risk of suicide, violence and homicide at all ages.

- Depression pills are likely to destroy your sex life, in the worst case permanently.

- Consult a psychotherapist. You might also consider if you need a social worker, counsellor or lawyer.

To read the footnotes for this chapter and others, click here.

I know Peter is one of the “good guys,” nonetheless I don’t comprehend why we are now on the 5th installment still belaboring what was more or less agreed upon after the first installment — that simply having “evidence” does not connote legitimacy to the conclusions based on that evidence, and is essentially meaningless without considering evidence to the contrary. So the question “is psychiatry evidence based?” is really the wrong question to begin with, which should be something more like “does psychiatry interpret its proffered ‘evidence’ in a legitimate manner?”

But the real question is always “How can psychiatry conduct ‘research’ on a figure of speech with a straight face?” And maybe also “should high school writing and literature classes contain mandatory warnings about the manipulation of metaphor in everyday life?”

Report comment

Facts and logic likely won’t get someone out of an opinion that facts and logic didn’t get them into.

This especially applies when the facts and logic show the person has caused massive suffering and harm.

Schools and parents should teach kids about logical fallacies. A major problem is that most discussions devolve into repeating the same logic fallacies over and over. But then adults wouldn’t be able to easily use those logical fallacies to control the kids.

Psychiatry initiates family and people by getting them to coerce “mentally ill” people to take drugs and “seek help”. This is exactly what gangs do when they initiate new members by having them commit a crime. These initiated people can’t exit denial when they see facts and logic about how psychiatry causes only harm because they helped perpetuate psychiatry on others. It is either admit they got conned into poisoning and stigmatizing their loved ones, or flail with logical fallacies, and ooze self righteous anger at the messenger. Maybe an effective strategy is first addressing people’s guilt. How to do that is beyond me at the current moment though.

Report comment

Yes, that “guilt,” my husband and family felt, after “trusting doctors” (psychologists and psychiatrists), did destroy my marriage. And that “guilt” is still something my mother has a hard time dealing with, but at least she tries to admit to her mistake of “trusting doctors.”

Shame on the mainstream medical community, and other “professionals,” for partnering with, and giving credence to, the scientific fraud based psychologists and psychiatrists. Merely because the psychologists and psychiatrists cover up your easily recognized malpractice, and child abuse covering up crimes.

Report comment

The only correct strategy to blame the real culprits – of apologists of psychiatry. Of those, who impose psychiatric dogmas on society as attitudes that regulate the relationships of community members. These dogmas are absolutely immoral, cruel and illegal. But by these attitudes replace the law.

Report comment

Journey into the surreal. Big Time Psychiatry and You. And they’ll tell you you know nothing and you’d better be forking over the billions to get to Psychiatric Heaven (maybe). And if anything bad happens to you, it’s your fault because you weren’t zombie enough and had a mind of your own.

Report comment

If you do have a mind of your own you’ll likely be stigmatized as “anti-science”, “lacking insight,” and “dangerous”. You’ll be pressured to go to psychiatry for “treatment.” When you complain about anything you won’t be taken seriously because you’re mentally ill and off your drugs so it is automatically your fault.

What’s to be alone when I’m a disease?

It’s no longer home if you set it aflame

In the fire my brain gets the blame

You act like I’m a game to control.

Passed out again with wine on your face

I ask to be treated as if I was human

How could I be fine with a reply of no?

I’m a ghost in death and in this place

But I heard you blame the bottle on me

Still with love that is ready to forgive

For the muscles I can no longer control

And the headaches exacting their toll

Yet with wine you yell “take those pills”

Since even my ghost you want to kill.

Report comment

Lovely, and poignant, poem, Willoweed. Thanks. Just so sorry that so few of the psychologists and psychiatrists, nor their religious leaders, even want forgiveness, from God. Who I believe is love.

Report comment

Great exposure of psychiatry’s lies and crimes are always a very good thing, and Peter Gotzsche does it in a very convincing way. Thank you, Richard

Report comment

Time to read Brave New World again I fear.

Report comment

“All good children” by Catherine Austen is another science fiction book with a story revolving around the wonders of drugging people “for their own good”

The Plague Dogs by Richard Adams is a fiction about two dogs who escape a medical research lab. One of the dogs was subjected to a lobotomy type mutilation. The dogs in the book can be viewed as representing how society treats those who are labeled as mentally ill.

One flew over the cuckoos nest is good book which needs no explanation.

Report comment

Thank you for publishing this.

The suicide studies hit close to home. Neuropsych effects and suicide are closely linked to the lyme community and I know many late and chronic lyme (stage three and PTLD) patients are also psych drugged. One has to wonder if the drugs are contributing to the high rate of suicide in the lyme community. This disease can be Hell on Earth but suicidal feelings are a lot easier to manage without the disinhibition that comes with SSRIs and akathisia of the neuroleptics.

I’d really love to have these statistics for all chronic illnesses since so many chronic illness patients are also treated with psychiatric drugs. It would be interesting to know in other chronic illnesses if there is a connection between the psych drugged population and the suicide rate.

Report comment

Being minimized by medical community will be enough to get people really

down. Then that is treated as “depression”.

Sometimes, it’s just all too much, and the psych drugs might just be the thing that broke

the camels back.

Report comment

“Consult a psychotherapist. You might also consider if you need a social worker, counsellor or lawyer.” This is not actually good advice, except maybe the lawyer part. Since all the psychotherapists and social workers my family had the misfortune of dealing with lied, and did next to nothing. Other than to misdiagnose the common odd, adverse, and withdrawal symptoms of an “antidepressant” as “bipolar.” And ship an innocent human being straight off to the psychiatrists to be massively neurotoxic poisoned. Since none of the “mental health” workers were apparently intelligent enough to read their own DSM-IV-TR, which clearly stated:

“Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.”

And this disclaimer was taken OUT of the DSM5, no doubt to spite Robert Whitaker. Who, thankfully, pointing out the massive in scope iatrogenic “bipolar epidemic.”

https://www.alternet.org/2010/04/are_prozac_and_other_psychiatric_drugs_causing_the_astonishing_rise_of_mental_illness_in_america/

And later, a school social worker attempted to drug my child, because my child had healed from sexual assault; medical evidence of which was eventually handed over, by decent nurses. And my child went from remedial reading in first grade, after the assault, to getting 100% on his state standardized tests in eighth grade.

But I will say all the lawyers I contacted refused to take a case of blatant psychological and psychiatric malpractice. CPS does not look into real cases of child abuse, once the medical evidence of such has been handed over. And the Chicago police tell a mother, whose had the medical evidence of the abuse of her innocent, three year old child handed over, to “talk to a psychiatrist,” rather than doing an investigation.

But, thankfully, I was at least able to scare a private school, which had a pedophile on it’s school board, into closing it’s doors forever. After the medical evidence of the child abuse was finally handed over. So, hopefully, I at least helped protect other children from satanic pedophiles.

But make no mistake, both the psychological and psychiatric industries, and all the DSM “bible” worshippers, in cahoots (“conspiracy” or “partnership”) with the mainstream paternalistic religions, who own the hospitals, are running a multibillion dollar, primarily child abuse covering up, scientific fraud based, “mental health” system.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

https://books.google.com/books?id=xI01AlxH1uAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

These systemic child abuse covering up crimes of the “mental health” and social workers, and religions, were confessed to me, by an ethical pastor of a different religion, to be “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.”

But now that we all live in a “pedophile empire,” many thanks to these “dirty little secret of the two original educated professions'” systemic crimes.

https://www.amazon.com/Pedophilia-Empire-Chapter-Introduction-Disorder-ebook/dp/B0773QHGPT

I hope and pray that God, and we, can take our world elsewhere instead. But recommending people trust in any DSM “bible” biller, or even any mainstream paternalistic religion pastor, is unwise, at this point in time, sadly.

And I will say, the “depression pills” are being handed out, by unethical, malpractice covering up PCP’s, for disingenuous reasons, as “safe” drugs. But I couldn’t agree more, “Never accept treatment with a depression pill. It is likely to make your life more miserable. Don’t believe anything doctors tell you about depression pills. It is highly likely to be wrong. Depression pills are dangerous. They increase the risk of suicide, violence and homicide at all ages. Depression pills are likely to destroy your sex life, in the worst case permanently.”

That is all completely true. Even for those of us, who had to teach the head of family medicine, at one of the most well respected hospitals in the US. That even Wellbutrin, a SNRI, which was “illegally” marketed as a “happy, horny, skinny pill,” for good reason. Because it can have the opposite effect, than most the SSRI’s have, on people’s sexual life.

It’s truly shameful that mainstream doctors, and psychiatrists, know nothing about the common odd, bizarre, and adverse effects of the psych drugs, that they coerce, and force, onto innocent people. While the DSM misdiagnosing, non-medically trained, psychologists and social workers fraudulently claim “the psychiatrists know everything about the drugs.”

Psychiatrists, the mainstream doctors, and all the DSM “bible” billers, claim to know less than zero about the common odd, adverse, and withdrawal effects, of the psych drugs. And they’ve been apparently murdering “8 million” innocent people every year, for decades.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mortality-and-mental-disorders.shtml

Despite the fact, all doctors were taught in med school that both the antidepressants and antipsychotics can create create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome, in med school.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Report comment

There is absolutely no psychiatric heaven. There is only psychiatric hell. But, of course, the psychiatrists and their LCSW buddies will tell you differently (a con!). Also, those little depression pills as the author of this article tells us to “say no to” are basically “gateway drugs.” Those “little depression pills” are like and some still consider this as such: “the marijuana of yore.” I have no patience for marijuana either. But, these “little depression pills” are much worse. They are dispensed by alleged authority figures who maliciously use that authority to convince you to take more and more drugs and there are all kinds of reasons: side effects for one. True freedom will come when America and the world wakes up to the fact that the worst drug pushers are the ones with the degrees who hide behind these degrees in their cute little offices all over America and the world. Thank you.

Report comment

The first Prozac trials gave people benzos to deal with the agitation, sleep troubles and anxiety caused by serotonin drugs. It’s now standard for psychiatry to give people drugs that increase serotonin followed by a neuroleptic which blocks dopamine and serotonin. It is exactly like taking cocaine to get up and opioids to get down.

It also goes the other way as well. Give them neuroleptics followed by stimulants or serotonin drugs to address the effects of the first deadly drug. When the drugs cause akinithsia and TD you’ll get some more deadly dementia causing drugs with zero long term benefits.

Tobacco should have went the psychiatry route. “People have tobacco deficiencies. Studies show tobacco users have biological differences and illness. We have 6 week studies showing tobacco is safe and improves energy, happiness, and productivity. When people with tobacco deficiency disease quit tobacco their symptoms come back and they suffer. Anyone saying otherwise is anti-science, shamming sick people, and being dangerous.”

Report comment

If I say that, wearing the color black is a nono, and if you wear black, then obviously you are defying the norm. You might even feel isolated and shunned for wearing black, but the “evidence” is there, in fact you are wearing black, and thus should either conform or get out.

But no, black was not the disorder, nor was the decision to wear it. Perhaps you were neuro diverse and were purely compelled to wear black.

I made up what will be the evidence, so of course, I will always be able to spot that “evidence”

Report comment

Exactly.

Here is some of what psychiatry measures to determine if their drugs improve depression.

Each change bellow is a 2 point improvement

gaining weight

agreeing you are ill and defective

fidgeting less with hands and hair

Look irritable instead of apprehensive

No longer occupied with health

No longer has moderate complaints about physical symptoms

The drugs in the most biased studies with half a dozen major flaws that make the drugs appear better record a 1.5 point improvement. The studies that release the weekly data show this improvement only occurs in the beginning of use. The withdrawal group (falsely labeled as placebo) has the same relapse rate in weeks 5-6 as the drug group.

https://dcf.psychiatry.ufl.edu/files/2011/05/HAMILTON-DEPRESSION.pdf

https://www.madinamerica.com/2018/03/do-antidepressants-work-a-peoples-review-of-the-evidence/

Report comment

Peter, I can’t thank you enough for being honest enough to write this and

thanks to MIA for printing it.

Long ago, they used knives and all kinds of “treatments” on people, children.

No public members questioned it. If they did, it was silently, or they were ignored.

Eventually, it was from the “inside” that it was frowned upon.

They switched to a more hidden practice by using brain pills. There was absolutely ZERO science

in the use. Only some chemistry in the actual creation of the drugs. It “treats” NOTHING!

Again, from the “inside”, is the rumble. Because THEY and their subjects know. The “public” is mostly

preoccupied with eating.

We have to keep asking the young and upcoming. “what is science”.

Report comment

The trick to protecting yourself from the medical community, who seems to want to drug all people with the “depression pills.” May be to tell the unethical doctors, that you are allergic to the anticholinergic drugs. That comment does tend to make the unethical doctors, quickly walk away, in embarrassment.

Report comment

My experience with physicians and SSRIs has not been positive. Years ago a psychiatrist prescribed an antidepressant for my son (for anxiety). He wound up in the ER with the feeling that his whole body was on fire. The ER doctor said it was the SSRI. When my son called the psychiatrist, he said no way it was the drug and wanted to increase the dose. I’ve had two internists over the past 10 years. Both wanted me to take an antidepressant (not for depression). The second doctor was so insistent I lied and told her I’d think about it. You can say change doctors, but I think most of them are that way. Concerning antidepressants, the medical profession abetted by the FDA, has been irresponsible.

Report comment

Yes the medical profession is very fond of psych drugs because they hope the patient will go away.

Problem is, they come back with many more issues.

Our “health system” is not about health, it makes people ill.

They have lack of science, useless drugs and no time, but if they prescribe something, it makes them look

as if they are being scientific.

Report comment

Well, they can’t TOTALLY go away, or they’ll have to find new customers. They mostly want them to be inert, except to have just enough energy to pick up their next prescription.

Report comment

The notion that one can just change doctors is kind of outdated with modern electronic records. (EPIC really IS epic.) The new doctor is generally able to view other doctors notes about you and will be biased before he even meets you.

In fact, there really is no clean slate for anyone in the current era. You are who you always were and there is little motivation to change and grow in a culture where you can be canceled for something you wrote or said or thought too loudly when you were younger in a different headspace. That is depressing in and of itself.

Report comment

Why is it that whenever something goes sideways after starting ‘treatment’ (drugs) they always ALWAYS want to increase the dose of whatever it was that made things screwy in the first place???

ALWAYS

I’ve been out in the internet world a lot lately; my conclusions are depressing.

RW’s message about psych drugs is still not being heard. Psychiatry’s message is embraced and history repeats itself.

My own ‘brain injury’ from poly-pharm/benzos is much better after 7 1/2 years but boy…still so many deficits. Still huge amounts of anxiety. Driving freaks me out; it’s a real problem.

Glad y’all are still fighting the good fight. I’m just tired- but always react like someone conditioned whenever anyone starts going on about folks with ‘mental illness’ or how much their antidepressant is helping them…I will never shut up about what is happening to so many distressed humans via capitalism.

Report comment

It can never be caused by the “treatment” – it’s always the patient’s or the “disorder’s” fault, as if the “disorder” is some kind of animated being that is trying to thwart their “treatments.” It seems it is never, ever the doctor’s fault or failure, no matter the actual data.

Report comment

Why are governments allowing pharmaceutical companies to damage and kill people?

Report comment

Management of the population is one of the primary demands of government. The basic function of the carceral state – which includes both “corrections” as well as behavioral healthcare – is to keep the population under control. It is in the government’s interest to maintain control over the population even as a portion are harmed by such. One could ask the same kind of question about the “war” on drugs, that educated people know was largely an effort to suppress the Black population and has been assisted over decades by CIA operations in foreign countries to deliberately funnel drugs into US inner cities. Then our police turn around and patrol those places and incarcerate the population, whose labor is in turn exploited by both the state and private corporations. And politicians earn votes for being “tough on crime” and “keeping communities safe”. None of this is a secret. It is also why our “class system” is so effective at keeping us competing with each other instead of following our natural tendency to cooperate for survival. Nobody wants to be the poor schmuck at the bottom of the heap. We give to the homeless and to charity to prove we aren’t like them. But the truth is any one of us could be at any time due to the realities of our economic system and lack of a social safety net.

I actually believe that this is why so many people fall prey to conspiracy theorists and groups like Qanon. When people know they can no longer trust their elected leaders and government agencies, they are apt to seek out leadership elsewhere and cult-like behavior ensues. In the end, the chaos provides cover for ever greater expansion of privacy-invasion and collection of data in the name of security. It’s a self-perpetuating feedback loop at this point.

So yes, disabling (maiming and killing) parts of the population serves a very central function of keeping it under control.

Report comment

There has to be some “collusion” from elected representatives.

Report comment

Actually, I think “collusion” is a loaded term suggesting that elected representatives are fully aware that the legislated interventions they are promoting do more harm than good. The issues go a lot deeper than that.

I think we need to look at two factors, the most important of which is the single biggest barrier to almost all legislation and that is whether or not something will bring short term or long term results. In a system where we hold elections every 2-6 years with few restrictions on time limits in office, for most politicians, their main focus is going to be on what gets them re-elected. Those are the projects that appear cost effective with robust short term results they can use in their next campaign.

The second issue is looking at who they actually represent. In other words, who are their donors? Whose interests are they beholden to? The interests of rural and suburban voters can appear at direct odds with those of urban voters. Rich and poor voters again, different interests. So politicians are going to choose whose interests they are going to value more. It’s not inherently wrong for a politician to protect the interests of the people in their districts. It becomes more of an issue when districts are so deeply gerrymandered that so many politicians have deeply conflicting interests among their constituents.

It seems to me like a fixable set of issues but there are for sure many politicians for whom ‘corrupt’ is an apt label. One need only look at the mess in Georgia to understand the attempts to suppress the number of eligible voters because when more people are able to vote – especially those for whom voting is more difficult for myriad legitimate reasons (like the urban poor, BIPOC, etc) – those politicians are less likely to win. You could design an anti-corruption course just from studying Georgia elections.

I think you’re in the UK so the situation is a little different but to be honest, the UK seems to follow in the US’ footsteps so even though you have more protections and more political parties, your system doesn’t seem to work much different from ours. Power corrupts.

Report comment

Thomas Sas The physician’s job, inter alia, is to help: cure disease with the consent of the patient. The judge’s job, inter alia, is to harm: punish lawbreaking without the consent of the defendant… Wardens who carry out sentences imposed by judges harm their prisoners, regardless of the cause of the intervention. Psychiatrists who carry out sentences imposed by judges also harm their patients, regardless of the cause of the intervention… The difference is that jailers do not claim to be their prisoners’ benefactors, whereas psychiatrists insist that they are the benefactors of their involuntary patients… Most persons experience their coerced psychiatric treatment as punishment. That is why psychiatrists insist that the persons subjected to psychiatric coercion are psychiatric patients, not psychiatric victims; that psychiatric coercion is treatment, not punishment; and that individuals who oppose their “benevolence” are wicked enemies of caring for the sick, not defenders of liberty and justice. He who controls the vocabulary controls social reality. The erosion of our liberties is not a mystery. Overwhelmingly, it is the result of the alliance between medicine and the state, intensifying people’s dependency on pharmacratic authority and psychiatric controls, fostering and fostered by a hyperinflationary definition of disease and treatment. When the government controls religion, not only religious liberty but all liberty becomes a chimera. When the government controls health, not only medical liberty but all liberty becomes a chimera

Report comment

Health care is political

Report comment

The abuse into torture – drug, emotional, physical within psych ‘hospitals’ is the ‘treatment’. They haven’t got it wrong from their point of view. Now psych is being projected into the wider public outside of closed cultures of abuse by MSM – BBC is going hell for leather 24/7… much of the general public still do not get it having got their test/vaccine for a trip to a holiday beach with their heads firmly stuck in the sand.

Do they want psych to depose democracy and rule/torture us as Donald Ewen Cameron wanted…. or will they realise that psych is down right evil.

Report comment

“Psychiatrists dismiss research results that go against their interests.”

As myself and many others have discovered, psychiatrists claim to be in a ‘caring’ profession but have no regard for the health and well-being of those who trust them for ‘help’. It’s all a perverse facade.

Much gratitude for all the meticulous work you do Dr. Gotzsche exposing the depth of the fraud by drug companies and psychiatrists.

Report comment

Perverse is a good word.

My stomach turns knowing that as I type, some poor kid is sitting in a chair being ogled by perverts. Really, the practice of psychiatry seems to be a psychological adaptation to whatever deep seated shit they themselves have. I have no other explanation.

Report comment

To: Dr. Peter Gotzsche: I made an amazing discovery reading this latest Gotzsche installment. :

The pills that destroy your sex life are called happy pills

In the upside-down world of psychiatry, the pills that destroy your sex life are called happy pills. Half of the patients who had a normal sex life before they started on a depression pill will have their sex life disturbed or made impossible.4,116 The sexual disturbances can become permanent and when the patients find out that they will never again be able to have intercourse (e.g. because of impotence), some kill themselves.117,118

When I lectured for Australian child psychiatrists in 2015, one of them said he knew three teenagers taking depression pills who had attempted suicide because they couldn’t get an erection the first time they tried to have sex.

In my case, I was on the older drugs, ( phenothiazines ) and had only temporary, short term impotence. Impotence, in the form of erectile disfunction, has not been my problem for most of my life. I had different drug effects. But apparently the new psychiatric drugs, ( could they be the SSRI’s ? ) cause a far worse problem, as described in the excerpt I just copied above. If the new drugs can cause sexual disfunction in the form of impotence so bad that the man can never again be able to have intercourse; this effect is horrible beyond belief and constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in the extreem and it’s easy to see why these men frequently attempt suicide.

And this other section was very interesting too. :

It took quite a while before we learned that the Germanwings pilot who took a whole plane with him when he committed suicide in the Alps, and that the Belgian bus driver who killed many children by driving his bus into a wall, also in the Alps, were both on a depression pill.

These are 2 major mass murders; in which I doubt very much that the psychiatric drug pushers ( the real culprits ) were ever punished; since they practically never have been, in the history of these drugs. If the pilot and driver had lived; it would be absurd to prosecute them since they were either conned into taking the drug ( which millions are conned or defrauded into taking these drugs by drug company fraudulent

advertising ) or they were out and out forced on the drug. It’s just mind boggling what drug companies get away with nowadays.

Now we are in a new day and age where the drug companies next target is the whole human race; with Bill Gates blessings. But that’s another story altogether.

Report comment