In this article, Peter C. Gøtzsche reports what happened, or rather did not happen, when he contacted National Boards of Health in eight countries with his serious concern that the use of depression pills in children is increasing and leads to more suicides, apart from Denmark where usage decreased by 41% in just six years because of two simple interventions. The continued official denial that these drugs cause suicide and that something substantial needs to be done is appalling.

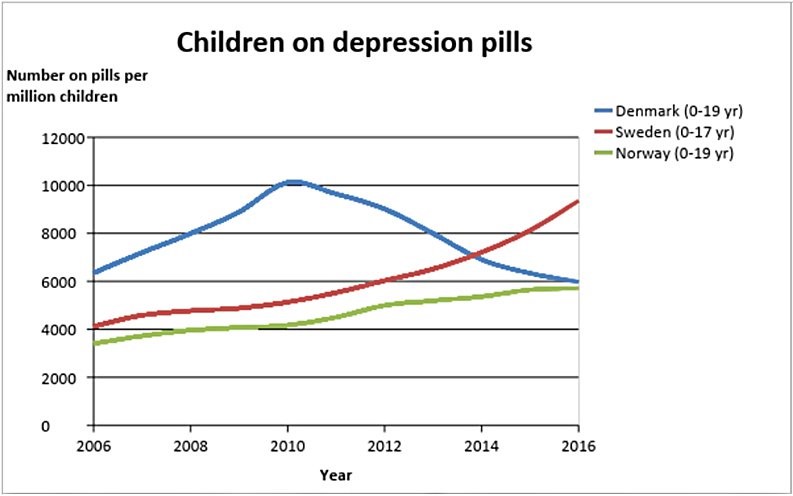

On 4 March 2018, I explained in an article on the Mad in America website that the usage of depression pills—commonly but misleadingly called antidepressants—was almost halved among children in Denmark, from 2010 to 2016, whereas it increased in other Nordic countries.1

On 22 November 2018, I wrote an open letter to the National Boards of Health in Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland about this very serious matter and attached my paper. I noted that depression pills double the risk of suicide compared to placebo in the randomised trials in children and adolescents, which is why health authorities all over the world have warned against using the pills since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alerted people to this fact in 2004 and again in 2006.2

Despite the warnings, the usage of depression pills in children continued to rise everywhere. In the summer of 2011, the Danish National Board of Health reminded family doctors that they should not write prescriptions for depression pills for children, which was a task for psychiatrists.

At the same time, I began to warn strongly against the suicidal effect of the pills, which I have done countless times ever since in radio, TV, articles, books and lectures. I was triggered by Lundbeck’s director who claimed in a radio interview to the astonishment of the journalist and a person from the Danish Drug Agency that the pills protect children against suicide.1

In my letter, I wrote:

The result of these two interventions are dramatic. Since 2010, the usage of depression pills in children and adolescents has dropped by 41% in Denmark while it has continued to rise in Norway, Sweden and Finland (data not shown in the graph for Finland in the attached paper, but usage in Finland increased by 44% from 2010 to 2017):

Leading professors of psychiatry in Denmark, Sweden and Finland have continued to deny that depression pills increase the risk of suicide in children to such an extent that they have claimed the opposite, that the pills protect children against suicide—in lectures, also for medical students, newspaper articles and scientific articles.

As I have documented in a book (Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial), to “prove” their point, these professors refer to unreliable research, and they consistently fail to cite much more reliable research that shows the opposite. Particularly two people have been responsible for the misleading research: Göran Isacsson in Sweden and Robert Gibbons in the USA. They, and others, have published papers showing that suicides went up after the FDA introduced a black box warning and the usage of depression pills went down, or vice versa. However, there are many countries and time periods where the opposite occurred, but leading psychiatrists consistently ignore also such data and publications.

In my view, this behaviour looks like scientific misconduct and it could be a punishable crime in a court of law, as drug companies have been held responsible for similar misinformation, also when it led to suicides in adults caused by the pills. The consequence of the collective, professional denial is that both children and adults commit suicide because of the pills they take in the false belief that they will help them. I shall not discuss the clinical effect here, only say that a clinically relevant effect on depression has never been demonstrated in children or adults (see my book, for example), not even for fluoxetine, which is the favoured drug for children.

In my view, children should not be treated with depression pills, and I therefore urge the Nordic National Boards of Health to take action. At the very least by issuing a guidance like the one issued by the Danish National Board of Health in 2011.

I explained that my research group had recently published unique research results based on our access to clinical study reports from the European Medicines Agency (about 70,000 pages) and that we were likely the only ones in the whole world who had ever read all these pages, which amount to 7 meters if stacked. This made it possible for us to show, for the first time ever that:

- Depression pills double the occurrence of aggression in children.3

- Depression pills markedly increase the occurrence of FDA defined precursors to suicide, violence and psychosis in middle-aged women with urinary incontinence.4

- 12% more patients (all ages) drop out of the trials when they are on a depression pill than when they are on placebo, which means that patients think placebo is a better pill than a depression pill.5,6

- Quality of life (all ages) has rarely been reported, even when measured in the trials, and even in the clinical study reports, there is markedly selective reporting of the results. This makes it highly likely that quality of life is worse on a depression pill than on placebo.5

I ended my letter by saying that I was willing to discuss the issues and to lecture on this, reminding the boards of health that the matter is very serious, particularly considering that leading psychiatrists misinform the public about the suicide risk of depression pills in all Nordic countries.

No Replies—Or Late and Meaningless Replies

I received no replies, apart from one authority explaining they had sent my letter to another authority. I therefore sent the letter again, two months later, and noted that I would upload it as an open letter on my website.7

I noted that the science clearly shows that depression pills increase the risk of suicide in children and adolescents and that they should therefore be avoided. I also requested to know when I could expect a reply.

Two months later, four months after my first letter, the Norwegian Directorate of Health noted that they were already aware of the usage of antidepressants among children and adolescents and that independent information about the effects and safety of medicinal products was important. They did not communicate any concerns about whether usage was too high or inappropriate but invited me to a phone meeting.

At the phone conference, one of the people on the line spoke about his own good clinical experience from treating people with depression pills. Pretty astonished, I reminded the Directorate of Health that clinical experience in psychiatry is highly unreliable, which is why we required placebo-controlled trials.2 The conversation lasted one hour but I got nowhere. These people did not want to do anything.

After five months, the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health responded in the typical mumbo jumbo sort of way that civil servants use when they praise a system that clearly doesn’t work, but refuses to acknowledge this and to take any action:

According to our legislation the health care must be based on evidence and it needs to be of high quality, safe and appropriately carried out. Finnish Medicines Agency Fimea promotes rational use of medicines in order to support the health of the population. Fimea also provides information on medicines in order to improve the effectiveness of medicinal treatments. National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health Valvira supervises and guides healthcare professionals and medical facilities both in private and public sector.

According to Finnish Evidence-Based Medicine Guideline on Childhood depression, “The use of medical treatment in childhood depression should always be carefully considered by a child psychiatrist, and any treatment should be monitored with frequent follow-ups … fluoxetine can be used … to treat severe or prolonged depression in children … increased suicidal thoughts have been connected with SSRIs in some studies.”

According to philosopher Harry Frankfurt this is “bullshit,” which he considers short of lying.8 I cannot see any difference to how drug companies praise themselves. Everything is always okay even when hundreds of thousands of patients die unnecessarily every year.9 Frequent follow-ups are a fake fix, as suicide in children often occur without any warning, when the child seems to be well but suffers terribly from the harms of the pill without realising that there is nothing wrong with them, only with the pill.2,10 Further, the systematic denial is obvious. “Suicidal thoughts” and only “in some studies.” This is terribly misleading and underplays the harms. When all studies are taken together, it is clear that depression pills increase everything: suicidal thoughts, behaviour, attempts, and suicides, even in adults.11,12

After five months, the Swedish Board of Health replied that I needed to contact the Swedish Drug Agency that monitors the usage of depression pills in children. They also referred to national guidelines. They expressed no concern that the usage had increased by 82% in a short time window, from 2010 to 2016, while it decreased by 41% in Denmark.1 In a report from December 2017, the Swedish Board of Health writes that, “There is great general interest in increasing prescribing of psychiatric drugs for children and young adults. The Board receives many questions about this from the media, for example.”13

It is not surprising that when the public has been seriously misinformed by people like Isacsson, who has been very active in promoting his dangerously erroneous ideas in the media, parents may think depression pills are good for their children.

After six months, the Swedish Drug Agency replied, in much the same way as the Finnish authorities did. It was all about processes, and since 2005, no new safety signal concerning suicide ideation/suicide had been discussed. I was told that the agency had issued treatments recommendations in 2016 so I looked them up. In February 2016, the Swedish Drug Agency arranged a meeting with experts in order to produce recommendations.14 For children, they suggested four different depression pills could be used. Under side effects, there was absolutely nothing about suicidality. Not a single word. Further down in the document, it was mentioned that depression pills increase the risk of suicidality slightly and significantly, but we are also told that, “they do not increase the risk of suicide, and there is some evidence that the risk is decreased.”

This information contrasts with the text in the Swedish package insert for fluoxetine, which mentions that, “Suicide-related behaviour (suicide attempt and suicidal thoughts), hostility, mania and nasal bleeding were also reported as common side effects in children.”15 Some of the so-called experts (e.g., Håkan Jarbin) had financial ties to manufacturers of depression pills, but none of this was declared in the report.

After six months, in June 2019, the Directorate of Health in Iceland replied: “We have asked for an expert opinion regarding the views expressed in your letter. I hope to be able to give you a detailed reply soon.” I never heard from them again.

Around 1 May, I sent a similar letter to the Therapeutics Goods Administration, Australia, Greg Hunt, the Federal Health Minister of Australia, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, the UK, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Public Health England, Matt Hancock, Minister of Health, New Zealand Ministry of Health, David Clark, Minister of Health, Medsafe, and Chloe Swarbrick, Spokesperson for Health, the Green Party.

I did not get any replies from Australia or the UK. I received an undated letter on 22 July 2019 from the Ministry of Health in New Zealand, which said that the drug regulator had not approved the use of fluoxetine for people less than 18 years of age. Furthermore, the government had just declared, in response to a report it had initiated, that they would complete a national suicide prevention strategy and plan and establish a suicide prevention office.

The background for this was dire, however. A UNICEF report from 2017 showed that New Zealand has the highest suicide rate in the world among teenagers between 15 and 19, twice higher than in Sweden and four times higher than in Denmark.16 Furthermore, the lack of approval of depression pills in children is no hindrance for their usage, which increased by 78% between 2008 and 2016.17 A report found that 3353 children under 14 were prescribed such pills through community-based providers (pharmacies) in 2018.18

Minister of Health David Clark declined to be interviewed about this, but the deputy director of mental health, Ian Soosay, said that, “Antidepressants will be part of a package” even though “the prescriptions aren’t the only tool used to help under-14s.”18

Why have a system of drug approval when even people in official positions don’t care whether a drug is approved or not? When I visited John Crawshaw, Director of Mental Health, Chief Psychiatrist and Chief Advisor the Minister of Health, in February 2018, I was told by the drug regulator that antidepressants were not approved for children. When I argued that they were used off-label all over the world, also in New Zealand, and asked Crawshaw to make it illegal to use these drugs in children in order to prevent some of the many suicides, he responded that some children were so severely depressed that depression pills should be tried.

So-called experts on suicide prevention appear to be highly biased towards drug use and in the way they cherry-pick the studies they decide to quote despite calling their review systematic.19 Suicide prevention strategies always seem to incorporate the use of depression pills,19 even though they increase suicides, as has been seen also in a suicide prevention programme for US war veterans.20

Conclusions

The title for one of the chapters in my book about organised crime in the drug industry is “Pushing children into suicide with happy pills.”9 Can we do any worse than this in healthcare, telling children and their parents that the pills are helpful when they don’t have any relevant effect on depression and drive some children into suicide?2,9,10 To a considerable extent, the misconceptions about depression pills are due to outright research fraud leading to omissions of many suicides and suicide events in published trial reports.2,9,10,21

Why is it close to impossible to get the truth accepted and to incorporate it in official guidelines?

Well, Pete, your work has probably got these distinguished medicos placing you in the Granola Crowd of crazed naturopaths who oppose all medical drug use, even though many of these “depressions” can be successfully treated by dangerous substances like vitamins B1, B3, B6 and B12. What doubtlessly makes them dangerous is your inability to kill yourself with them, unlike the antidepressants, where suicide by OD is quite common.

Report comment

Dear Dr Peter,

Its too big a scam to be allowed to collapse and there’s lots and lots of money changing hands. At this stage we’d need to Prosecute entire National Medical Councils and I don’t know if this would be likely to happen.

We don’t compulsararily trust Priests in Ireland, and we need to take the same approach towards Doctors (for common sense reasons).

Report comment

Unfortunately sticking to their guns means killing children; when these children could ultimately overcome their gloom.

Report comment

The good chemical dealer tells parents their child needs these chemicals.

Horrible, absolutely horrible.

I would also like to know whatever happened to being able to grow up to be the miserable grump?

Lord knows psychiatrists are not exactly bubbly.

But then, being dead to emotions for others seems to be the effect desired?

Because I no longer know who and what I am supposed to be, how long I should grieve etc.

Kids have no clue who they are supposed to be.

I guess psychiatry assumes that the brain stops developing or changing from age 2 or 6, or 14?

A shrink is the LAST person that should drug kids.

Kids are an offering put onto the altar of shrinks.

Report comment

And the shrinks and psychologists have chosen to become satanists?

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

If he gives a talk, and someone in the audience interrupts him and reacts emotionally, he will get into a state and threaten to leave. “I’ve put a lot of effort into my presentation …”. As I said, an academic.

Report comment

Peter, thank you for your continued efforts.

I am not quite sure why a powerful coalition cannot be formed to stop them, or at the minimum educate schools and universities.

I understand they are digging their heels in, as that is what any criminal governments do, because they simply cannot admit, to save face.

We have to do something. I myself am busy trying to debrainwash my adult children and hope they will do the same for their kids.

Report comment

“Why is it close to impossible to get the truth accepted and to incorporate it in official guidelines?”

They are all corrupt therefore have to keep the lies going just like a ponzi scheme, and will do what all abusers do – blame the victims ‘mental illness’.

I urge everyone to bookmark this post and reference it to any parent of a young person subject to this crime of lies, inflicted toxic horror and suicide for profit. Record all your interactions with these neurotoxin destroyers.

Report comment

Peter, could you please include Estonia to your list of countries?

Report comment

“We have asked for an expert opinion regarding the views expressed in your letter. I hope to be able to give you a detailed reply soon.” If I’m not correct, as a doctor and medical researcher, yours is an “expert opinion.”

But, then again, those of us who’ve had the common adverse effects of the antidepressants misdiagnosed as “bipolar,” resulting in a whole bunch of medically inappropriate anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings. We, too, are experts by experience and medical research.

“Why is it close to impossible to get the truth accepted and to incorporate it in official guidelines?” $$$ / corrupt officials?

Thank you, as always, for speaking the truth, Peter.

Report comment

Not only have I found it difficult to get someone ever enduring anti-depressants to engage with these very well documented statistics, but I’ve had it where someone already off of them, which the other ended up being as well, that one is there to: you know like a used car dealer where they sell you something that doesn’t work, although you have to pay to get it as well as transport it to where you’ll fix it, and then also pay membership fees, and when you figure out what they should have told you, being nice, they repeat what you said and say that that’s why they people that.

!?

Is suicide supposed to exist in Heaven that it’s a thought that doesn’t depend on an anti-depressant, because I think that already would, Heaven existing at all, mean that we have a soul, and that doesn’t die, but thoughts do when they are incapacitated, and that is what ALL psychiatric drugs, and ALL “medical” psychiatric treatments do, and that is disable natural functions of the mind.

Because that’s then their argument, that stopping anti-depressant won’t stop violence, or suicide or the drug companies lying to everyone.

It’s all just conformistic convenience, like Johnny Depp making a movie with Mr. Actor who defends his child murdering, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_Brando but are we to get him and Johnny to admit how misinformed they’ve put forth truly damaging ideas, it’s oh, but there’s something else that makes people violent, or there’s an excuse for the violence, or it never happened, people like that don’t do such things.

And children who truly don’t do such (see above) are never sexually molested.

And chase scenes don’t get people so riled up they don’t know where they are anymore, or how to respond to even trying to cook a meal with the sounds they’ve heard pounding in their consciousness trying to find some entertainment, some leisure for their mind.

And when Johnny Depp has a hoard of friends and family members as well as his pimp Tim Burton make excuses for his behavior when he assaulted his ex wife numerous times, this is normal for the supposed oddballs to have such drug habits, legal and not.

OH, and I forgot Time Burton isn’t his pimp. That used to be someone from Russia who didn’t even know who he was, and he got into doing gay porno under a pseudonym. And has been stalking and trying to intimidate me for more than 20 years feeling free to create gossip about me I never invited while surfing on what he lets out about himself, to sexually harass me and stalk me in coffee houses (helped by the family of someone who died from drugs on his property), and oh, he made a movie where a pill magically helps Don de Marcos know who he is again. Or that flick where his love interest gets treated like she’s at a tropical resort after being committed.

And this isn’t even fictional.

Report comment

I find Ricky Gervais’ performance at the Golden Globes interesting, to say the least. I won’t go so far as to say his performance has any real value, though.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sR6UeVptzRg

A bit like the downfall of the Roman Empire 2000 years ago.

Report comment

It looks to me like things are opening up a bit in the UK (and Ireland) regarding the problems with “antidepressants”

BBC News – ‘My anti-depressant withdrawal was worse than depression’

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-51834456

I don’t think the BBC would represent this type of article, even a year ago.

I think the momentum is due to patient and persistent human rights campaigning.

Report comment

Why no one think about suicidal notes, is it really written there that “I blame the tablets against the depression in my death”. Theoretically, you can imagine this? As far as I know, the cause of suicide in the conspiracy of parents and psychiatrists, if we are talk about chronic mental illness (since childhood).

Report comment

Most people who become suicidal as a result of taking any drug are unaware that the drug is the cause. And those who are aware or are becoming aware are roundly invalidated by their doctors and “mental health professionals” in the majority of cases.

Report comment

Bang on Steve !

Report comment

GPs ‘now’ prescribe these drugs so they’re bought into responsibility with Psychiatry for outcomes, even though they mostly were not informed of the capacity of the drugs.

If the drugs go down then GPs go down.

Report comment

My good luck was that I could tell when I was in a state of Acute Akathisia. Each time the Acute Akathisia followed a medication introduction, medication change or a medication discontinuation.

Though expressing this did not make me popular.

Report comment

Hello Peter,

Great work! I found this related article on pubmed.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3844115/

Abstract

Objective

To examine if the suicide rate of older adults prescribed antidepressants varies with age and to assess the proportion of older adults who died by suicide that had recently been prescribed antidepressants.

Methods

A population-based cohort study using a nationwide linkage of individual-level records was conducted on all persons aged 50+ living in Denmark during 1996–2006 (1,215,524 men and 1,343,568 women). Suicide rates by treatment status were calculated using data on all antidepressant prescriptions redeemed at pharmacies.

Results

Individual-level data covered 9,354,620 and 10,720,639 person-years for men and women, respectively. Men aged 50–59 who received antidepressants had a mean suicide rate of 185 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 160–211) per 100,000, whereas for those aged 80+ the rate was 119 (95% CI: 91–146). For women, the corresponding values were 82 (95% CI: 70–94) and 28 (95% CI: 20–35). Logistic regression showed a 2% and 3% decline in the rate for men and women, respectively, considered in treatment with antidepressants, with each additional year of age. An opposite trend was found for persons not in treatment. Fewer persons aged 80+ dying by suicide had received antidepressant prescriptions during the last months of life than younger persons.

Conclusion

An age-dependent decline in suicide rate for antidepressant recipients was identified. One reason could be that older adults respond better to antidepressants than younger age groups. Still, the increasing gap with age between estimated prevalence of depression and antidepressant prescription rate in persons dying by suicide underscores the need for assessment of depression in the oldest old.

I hope it is of any use to you.

Report comment

“Why is it close to impossible to get the truth accepted and to incorporate it in official guidelines?”

As I explain in Rebel Minds (https://remarxpub.com/rebel-minds/), global capitalism functions to transfer wealth from the many to the few, something it does exceedingly well. In the process, billions of people are exposed to preventable distress, disease, disability, and premature death.

To protect their system of grand thievery, the ruling class refuse to acknowledge the systemic sources of suffering. Instead, they blame individuals for ‘failure to cope’ (an actual medical term!) and direct people in distress to the medical system. The pharmaceutical industry parasitically profits by reinforcing the medical model of human suffering.

We don’t need more studies to prove what we already know. The truth does not matter in a system that hides the truth about so many things, especially its own role in destroying people’s lives. (See https://susanrosenthal.com/labor/a-socialist-response-to-covid-19/).

To quote Frederick Douglass, “The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong that will be imposed upon them. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Douglass was right. We need to organize a powerful mass movement to demand a very different society that will meet people’s needs. If that means sweeping the global capitalist class from power, then that is what we must do.

If you think that is impossible, pie in the sky, a pipe dream, consider this: When all ‘reasonable’ solutions have proved inadequate to the task, then the only road left, however improbable, is the one we must travel.

Report comment

Susan, well said.

And I very much agree with your last statement and FD’s quote.

Just a few weeks ago, Canada’s first nations people put up roadblocks to stop a pipeline.

All news articles had comments that were against the First Nation’s peoples. In fact, the candidate Scheer who did not win the last PM election, said that the First Nation’s were “privileged”.

Meaning that the fact we give them a pittance to survive on is “privilege”.

As you said, “failure to cope” is what most actually privileged people think is the problem of the victims.

And that it is the victim’s fault.

I saw the roadblocks as a success. It paves the way for other people who are fed up.

Yes, watching the roadblocks, some things were done which people could easily describe as “illegal”, like throwing a burning tire on the tracks of trains.

Yet the MANY illegal oppressive moves done to vulnerable people are never brought to account.

There is no soft rational manner to deal with oppressors.

The first and most important move is to teach people how to say NO.

Psychology parades around words and phrases that they themselves abuse.

Words like “BOUNDARIES”. Psychology for $150-250 per hour, will tell their “patients” about how they should create boundaries in order to move “forward”.

I can teach anyone how to stick up their middle finger at their oppressors for free. I am way past

trying to talk nice to any medical power.

I learned about boundaries, I learned the word NO, and if I have no voice left, I have sign language.

If it comes down to printing off information and driving with a covered licence plate around school zones to “litter” the information around the streets and neighbourhoods, so be it.

All I can be charged with is “littering”.

As in anything related to fighting oppression, we need to set up support networks, to give legal aid, etc to those in movements.

Report comment

Susan,

I agree with you, and I wish I could describe things in such articulate terms.

Report comment

This morning as usual, news about covid-19.

About how it’s affecting adults, and I said “wait for it”, “mental health” and children will be the topic.

Of course it was an easy guess.

So the news person talks about the little ones, the children, oh so tenderly and rehashes the words of an esteemed child psychiatrist.

You know, just in case our little ones are “affected”, “anxious”, in response to news and hysteria.

You know, they will need “mental health treatment”. We should watch out for any symptoms, signs of anxiety so we can take them to our trusted MI caretakers who really mean well.

So much ignorance mixed with an inability to reason, mixed with sheer want of the job. Psychiatrists I think might generally not be THAT stupid, so it must be a plan, but I very highly doubt it is an intent as in malicious targeting. It is simply to protect their lies, their income.

The mangled and the dead, are just the byproduct.

Ohh dear, I do sound so radical, so anarchist, don’t I. Just nobody, spewing my anti-psychiatry rants, just a disgruntled user, an axe to grind….

No, actually I care more about children than myself.

Report comment

The ones that must be made understand what happens is the parents.

The doctors, most but not all of them, and the state officials are too greedy to reject the temptation of the money from Big Pharma. They’re not innocent.

Report comment

Dear Professor Gotche,

Thankyou very much for your research and efforts to raise awareness about the denial & misinformation being given to the public, as well as the evidence for “antidepressant” risks & low clinical efficacy, especially in children.

Australia currently has an open Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disabilities.

Would you be interested to send them a submission? It would hopefully get a more serious consideration than the one you received from Minister Hunt.

Awareness on these issues are very low in Australia and there are key influencers who push very strongly for the “early intervention” model.

It would be very helpful for the commission to receive expert information regarding the research into risks, harms & low efficacy, especially for children and young people, as well as the information on why the research used to claim the opposite has been misrepresented.

Thanks very much again for your work and highest regards.

Report comment

Dear Professor Gotche,

Thankyou very much for your research and efforts to raise awareness about the denial & misinformation being given to the public, as well as the evidence for “antidepressant” risks & low clinical efficacy, especially in children.

Australia currently has an open Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disabilities.

Would you be interested to send them a submission? It would hopefully get a more serious response than the one you received from Minister Hunt.

Awareness on these issues are very low in Australia and there are key influencers who push very strongly for the “early intervention” model.

It would be very helpful for the commission to receive expert information regarding the research into risks, harms & low efficacy, especially for children and young people, as well as the an explanation helping the commission to understand how they research used to claim the opposite has been misrepresented.

Sometimes it gets easy to bamboozle even those who do want to understand, because they don’t have the background to see how data has been manipulated or cherry picked.

Thanks very much again for your work and highest regards.

Report comment

Dr. Gotzsche, I applaud you for all your diligent efforts. It is really disturbing to see such whitewashing and covering up of these matters when children’s lives are at stake. Trying to save lives should not be this difficult but please keep up your much needed efforts.

Report comment

Professor Gotzsche,

BBC News – German police arrest man over high-speed rail tampering

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51992070

When this man ‘messed around with the tracks’ he was arrested for Attempted Murder – and rightfully so.

There’s nothing funny about doctors playing around with pharmaceuticals and people’s lives.

Report comment