After Joanna Moncrieff and colleagues published their study debunking the low-serotonin theory of depression, the editor of Mad in Sweden, Lasse Mattila, wrote Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare, asking if this study would affect Sweden’s national guidelines for treating depression. Here is how the national board responded:

“The state of knowledge on the antidepressant effects of SSRIs is not based on theories of [their] mechanisms of action but on clinical studies comparing drug effects in patients with placebo. The article therefore does not change the state of knowledge on the clinical antidepressant effects of SSRIs or the basis for recommending antidepressants in the national guidelines for depression and anxiety disorders.”

The Swedish national board is pointing to a simple bottom line: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials have found antidepressants to be “efficacious,” and that is why the board recommends their use for treating depression and anxiety. At a national level, the drugs are seen as providing a positive public health benefit.

This is the same “bottom-line” understanding that has driven prescribing of antidepressants in the United States and much of the developed world. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) are seen as the “gold standard” for assessing the efficacy of a drug treatment, and their results are perceived in society as providing a binary conclusion: either a drug is proven to be effective or it isn’t. If it is the former, then it is understood that the presence of that drug in a country’s armamentarium serves a public health purpose: the drug should help ameliorate the public health burden of depression and anxiety.

This reliance on RCTs as the final word on the effectiveness of antidepressants—as though the God of science has stretched out his long finger and declared them good—is easily shown to have produced a public that is deluded about their merits and oblivious to the harm they have caused at a public health level.

To understand why this is so, we need only to investigate this question: In nature, there is often a natural capacity to recover from a “disease.” Do antidepressants improve on that natural capacity to recover?

As even a quick review reveals, RCTs of antidepressants don’t provide evidence of that. Even the limited data they do provide is of dubious quality, as they come mostly from industry-funded trials, and the findings are not predictive of outcomes in “real-world” settings.

The enshrinement of RCTs, in fact, leads to a type of societal and medical blindness. The psychiatric community—and by extension, our society—focuses on a single data point plucked from the RCTs: the difference in “symptom reduction” between drug and placebo groups at the end of the study period (typically six weeks.) Meta-analyses of trials have found the mean difference to be “statistically significant,” and that becomes the bottom-line. This conclusion remains even as researchers point out that the difference in symptoms is so small that it is clinically meaningless; that it comes from trials that are biased in multiple ways; and that when exposure to adverse events is added into the risk-benefit equation, the majority of patients suffer harm from the treatment.

That is the myopia that occurs when RCTs results are summarized. Perhaps even more problematic, findings from other types of studies—a history of research that spans more than 50 years and tells of antidepressants worsening long-term outcomes—are dismissed because they don’t come from an RCT. And voila! With the blinders firmly on, our RCT fetish leads to definitive pronouncements that antidepressants “work.”

This mindset was made visible in 2018, when an international group of researchers published a meta-analysis of 522 randomized trials of 21 antidepressants in the journal Lancet. Theirs was an analysis that focused on differences in symptom reduction at the end of short-term trials, and even though the researchers concluded that there was a “moderate to high risk of bias” in 82% of the trials, and even though the difference in symptom reduction was quite small, they concluded that all 21 “were more efficacious than placebo.”

Newspapers and other media picked up on the bottom line: This study had proven, once and for all, that antidepressants work.

This was the finding that Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare was referring to when it stated that clinical studies supported its recommendation of antidepressants as a treatment for depression. The RCTs had spoken, and that was all the evidence that needed to be considered.

RCTs in Psychiatry

The adoption of the “randomized, well-controlled, double-blind” study as the gold standard for assessing drugs dates to the late 1940s, when British investigators used a randomization design to assess the efficacy of streptomycin as a treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. The randomization provided a clear picture of the drug’s benefits, and over the next decade, the “well-controlled” and “double-blind” elements were added to randomization to create this “gold-standard “methodology.

Societal reification of RCTs came in 1962, when the FDA began requiring pharmaceutical companies to prove to the FDA that their drugs were not just safe, but effective too. The evidence for efficacy, the FDA stated, was to come from “adequate and well-controlled studies.”

As a method for assessing the effectiveness of a treatment for an infectious disease, an RCT has obvious value, and often can deliver a definitive judgement. However, even before the FDA added the efficacy requirement, it was understood that applying this tool to psychiatric drugs would have its challenges. The RCT was born as a way to assess the efficacy of a treatment for a specific disease, yet patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or depression were not known to share a common pathology. There were concerns that psychiatric drugs, because of their effect on inner emotional states, would lead to an unblinding of the trials, and this would lead to biased results. Most important, it was unclear how outcomes could be measured, given that there were no biological “disease” markers that could be assessed.

However, once the FDA adopted its efficacy standard, such concerns were pushed aside.

Psychiatry would have to adopt a disease model for testing its drugs. Psychiatrists developed “rating scales” to provide a numerical measurement of symptoms said to be characteristic of depression and other psychiatric disorders, and once that occurred, the societal blinders were fixed firmly in place. The rating scales of course would lack the precision that measurements of physical illnesses can have, and they would also be subjective in kind, and yet use of a scale would still spit out a specific number, and suddenly a score of 14 on a 52-point rating scale could be seen as a precise evaluation of a depressed patient’s symptoms.

The ingredients for an institutional myopia were now set. The FDA, the psychiatric profession, and society would see short-term reduction of symptoms as evidence of a drug’s efficacy, and even if a psychiatric drug did this only to a slight degree better than “placebo,” it would be deemed efficacious. The six-week clinical trial would be proof that use of the drug in society provided a benefit.

Industry-controlled RCTs

Prior to the 1980s, pharmaceutical companies mostly had to come with “hat in hand” to ask academic physicians to conduct their trials. NIH grants were the coin of the realm in academic medicine prior to that time, and the academic physicians, if they agreed to run the drug trials, would insist on designing the trials, analyzing the results, and publishing the results. The independence of academic physicians provided a scientific integrity to the trials.

For a variety of reasons, that independence began to disappear during the 1980s, and that was particularly true in psychiatry. The first SSRI to arrive on the market was Prozac in 1988, and by that time pharmaceutical companies had asserted control of the RCTs of their psychiatric drugs, and that has remained true ever since. The pharmaceutical companies design the trials, analyze the results, and decide what results to publish.

The results that emerge from RCTs of antidepressants serve the pharmaceutical companies in two ways: they provide data for FDA approval and “statistically significant” results that can be used to market the drugs. The question important for society is this: What is the relevance of those findings to clinical practice and their contribution to an “evidence base” for use of these drugs?

No comparison with “outcomes in nature”

The placebo group in a drug trial is supposed to represent the outcomes that occur in the “natural course of the illness.” However, in RCTs of antidepressants, patients currently taking such drugs are regularly enrolled and then they go through a brief washout before randomization to the drug and placebo arms.

As such, the “placebo” group is best described as a drug-withdrawal group. Thus, the trials do not provide information about the natural capacity of depressed patients to improve over the short term, and how RCTs may alter that natural recovery rate. For the RCTs to provide that information, patients enrolled into the trials would either need to be medication naïve, or at least have been off antidepressants for an extended period.

Study volunteers are not representative of “real-world” patients

For RCTs to be useful, they should provide evidence of drug effects in patients who will be prescribed that drug in clinical settings. However, in psychiatric drug trials, pharmaceutical companies use inclusion-exclusion criteria to select patients most likely to respond well to the treatment. Exclusion criteria in antidepressant trials may include psychiatric comorbidities, alcohol abuse, suicidal thoughts, and a non-response to a previous antidepressant.

A 2005 report by the House of Commons in the UK summarized this deficiency in RCTs:

“Human trials tend to have limited predictive value due to problems of extrapolation to routine clinical practice. Typically, only a small sample of the prospective population to be exposed to the drug can be studied in clinical trials. Furthermore, those patients who will probably be exposed to the drug if it is marketed may be excluded from clinical trials because they have multiple pathologies or take a number of different medicines.”

Studies have found that 60% to 90% of “real-world” patients are excluded from industry-funded trials of antidepressants. This led John Rush, a psychiatrist at Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, to observe in a 2004 article that “both shorter- and longer-term clinical outcomes of representative outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder treated in daily practice in either the private or public sectors are yet to be well defined.”

Use of concomitant medications confounds results

A RCT is designed to isolate the effect of the specific drug that is being tested. However, in antidepressant trials, the use of concomitant medications is common.

This practice showed up in the first SSRI approved for marketing (Prozac.) In the initial clinical trials of fluoxetine, investigators noticed that the drug was inducing “akathisia and restlessness” in a significant percentage of patients. In response, Eli Lilly amended its protocols to allow “the use of benzodiazepines to control the agitation.” The trials were now testing this possible combination of psychiatric drugs, and as Eli Lilly’s Dorothy Dobbs later confessed in court, the use of benzodiazepines was ‘scientifically bad,” as it would “confound the results” and “interfere with the analysis of both safety and efficacy.”1

However, once the FDA approved Prozac, drug companies understood that this “scientifically bad” practice was now acceptable. In a 1997 article, researchers wrote that “concomitant use of medication is a common practice in most clinical trials of antidepressant medication.”

The practice continues today. In the trials of vortioxetine, which was approved for marketing in 2013, the protocol allowed for “occasional use of zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon for insomnia.” Three of the 17 questions on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) assess insomnia, with the collective scores for the three questions ranging from 0 to six. The concomitant use of a sleeping pill in the trial could be expected to reduce this number, and thus help augment the “efficacy” of the antidepressant.

This means that RCT efficacy findings cannot be attributed to the antidepressant alone, but rather to the combination of drugs.

Bias by design

Pharmaceutical companies want clinical trials to produce results that will help their new drugs succeed in the marketplace. Their aim is not a scientific one, but rather a marketing one.

There are numerous ways that pharmaceutical companies seek to achieve this goal. They can design trials that favor the drug and minimize evidence of side effects, publish only the trials that produce positive results, and spin those results.

As noted above, in the antidepressant trials, patients who have been on antidepressants and other medications are enrolled into the study and these drugs are then rather abruptly withdrawn. The trials often then employ a “placebo run-in” phase prior to randomization. Those who get better during this phase—e.g., placebo responders—are not randomized into the study. This exclusion of placebo responders produces an entire cohort of patients that may be experiencing withdrawal symptoms at “baseline,” and randomization separates them into a placebo group that may continue to experience such symptoms, and into a group put back on a drug similar to the one they had been on.

In a 2019 paper, Nordic Cochrane Centre investigators concluded that this design could have three effects on study results:

- Participants treated with the study drug, or a similar drug, prior to inclusion and subsequently randomized to the drug will most likely tolerate it and experience fewer harms compared with a drug-naive population (reduced harms in the drug group).

- The withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group can be misinterpreted as signs of worsening of the depression or as adverse events (reduced benefits and increased harms in the placebo group).

- Participants already treated with an antidepressant and subsequently randomized to the study drug may have experienced withdrawal symptoms during the placebo run-in that are then alleviated by the study drug. It could be misinterpreted as an improvement of the depression, as opposed to a relief of withdrawal symptoms (increased benefits in the drug group).

A protocol may incorporate any number of elements designed to produce results favorable to the drug. For instance, a protocol may seek to reduce evidence of side effects by requiring patients to spontaneously report side effects, as opposed to having investigators ask patients about such symptoms. Or even if a symptom checklist is used, the list may not include adverse events that cropped up during earlier stages of testing but aren’t part of the known side effects of this class of drugs.

The FDA is well aware of this bias. FDA reviewers of “New Drug Applications” often point out the ways that the trials are biased in favor of the manufacturer’s drug, or how possible side effects have been minimized. This agency awareness showed up in the FDA’s reviews of Prozac.

In their written summaries of fluoxetine, FDA reviewers noted that its efficacy over placebo was of a marginal sort, and that it was less effective than the comparator drug in the trials, imipramine. Their review of case reports revealed that fluoxetine could cause a long list of troubling side effects—psychosis, mania, insomnia, nervousness, confusion, dizziness, memory dysfunction, tremors, and impaired motor coordination—and they could see that even this list of side effects was incomplete. Eli Lilly, wrote the FDA’s David Graham, had “engaged in large scale underreporting” of the harm that fluoxetine could cause.2 Another reviewer, Richard Kapit, provided this bottom-line conclusion: fluoxetine “may negatively affect patients with depression.”3

However, the FDA gave Prozac its stamp of approval, and in doing so, set a standard for the agency’s approval of antidepressants: even if the drugs performed poorly in trials, or even if the company had sought to hide adverse effects, the FDA would give it a green light.

Indeed, when Pfizer sought approval for sertraline (Zoloft), FDA reviewers noted it had failed to show efficacy in four of six trials, there was a fifth that was “questionable,” and only one that was positive. The FDA’s Paul Leber, while urging the FDA’s Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee to approve sertraline, confessed that he had “no idea what constitutes proof of efficacy, except what we, as a Committee, agree on, on an ad hoc [basis], that there needs to be.” The advisory committee, he added, “might say to us, ‘look, we think the standards in this field are terrible.’”4

All of this is well known. In a 2017 meta-analysis of 131 RCTs of antidepressants, Danish researchers concluded that all 131 “were at high risk of bias.” The Nordic Cochrane Collaboration Center investigators, who reanalyzed the data from the 522 studies in the Lancet study, concluded there were none that were free from a risk of bias, and that there was a “high risk of bias” in 414 trials. As a result, they concluded that the “certainty of evidence” in the Lancet meta-analysis was “very low.”

Antidepressants do not provide a clinically significant benefit over placebo

The primary outcome in RCTs of antidepressants focuses on a single measurement: At the end of the study (usually six weeks), have symptoms in the antidepressant group decreased more than in the placebo group, and is the difference statistically significant?

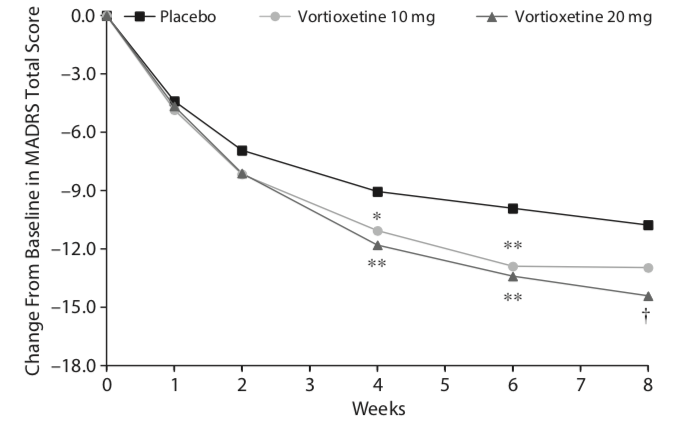

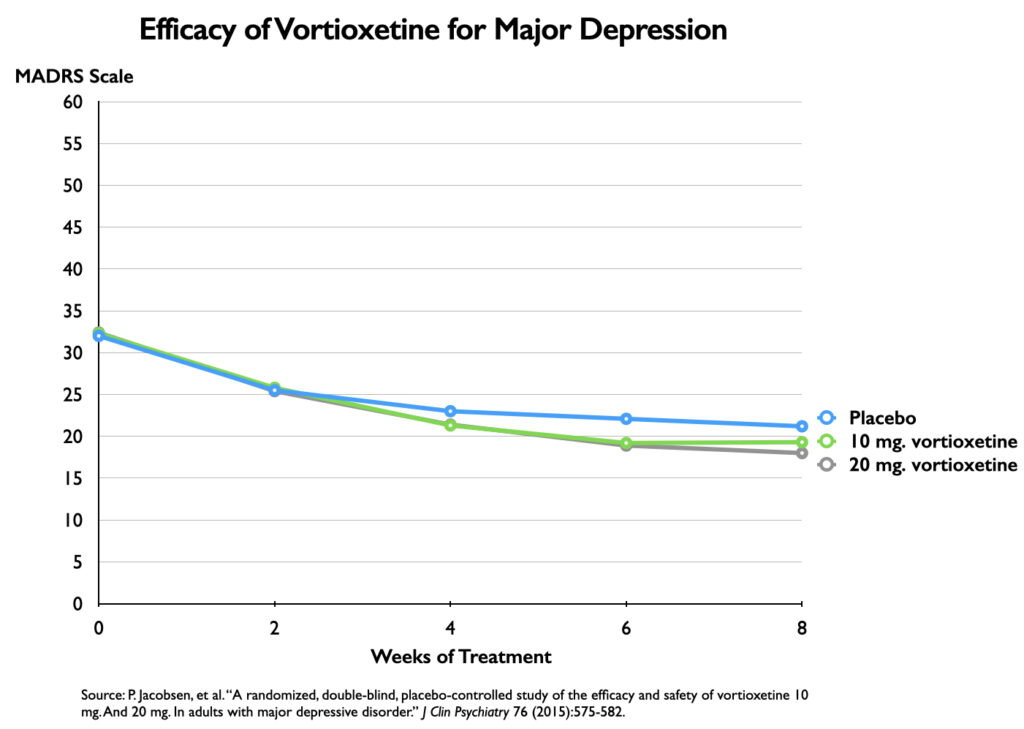

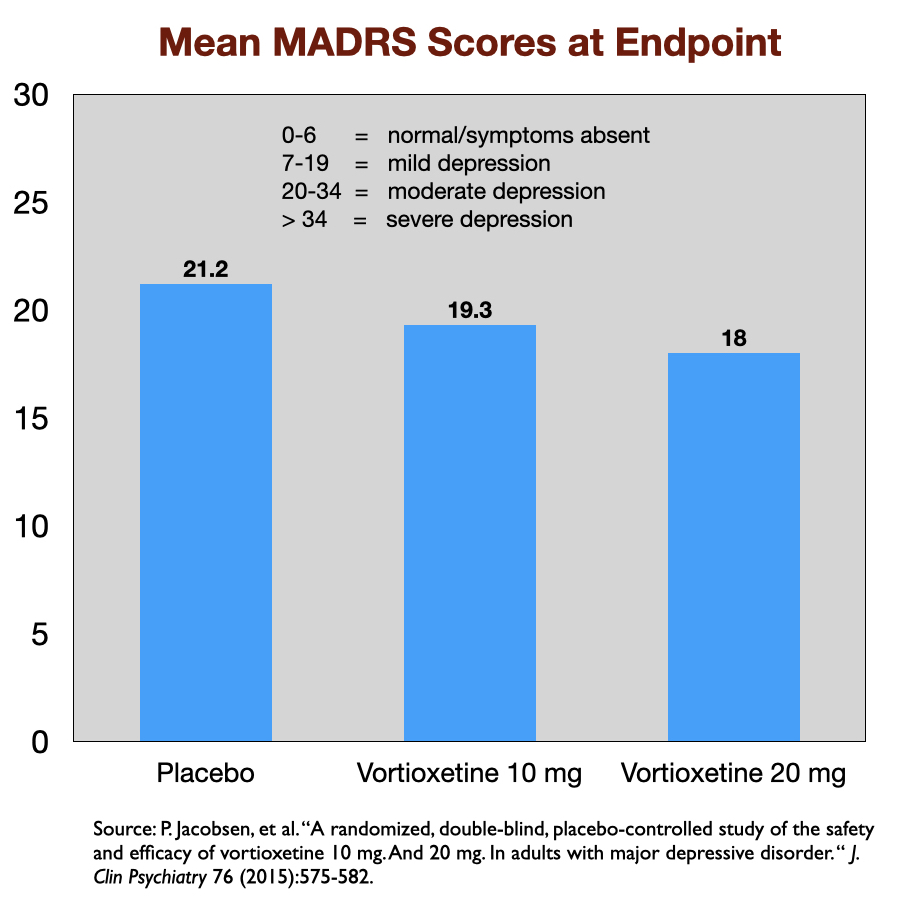

Reports of industry-funded trials regularly feature a graphic that appears to show a noticeable difference in symptom reduction between the antidepressant and placebo. Here, for instance, is a graphic that tells of outcomes in a US trial of vortioxetine, which was approved by the FDA in 2013. Symptoms were measured on the 60-point Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

This graphic, upon close examination, shows that symptoms decreased about 14.4 points for those given 20 mg of vortioxetine, 13.0 points in the 10 mg group, and 10.8 in the placebo group. The difference of 3.6 points between the placebo and 20 mg dose was statistically significant, and thus evidence of the drug’s efficacy at that dose. (The 10 mg dose didn’t pass the “statistically significant” cut.)

This graphic, upon close examination, shows that symptoms decreased about 14.4 points for those given 20 mg of vortioxetine, 13.0 points in the 10 mg group, and 10.8 in the placebo group. The difference of 3.6 points between the placebo and 20 mg dose was statistically significant, and thus evidence of the drug’s efficacy at that dose. (The 10 mg dose didn’t pass the “statistically significant” cut.)

However, the chart serves as an illusion of efficacy. The difference in symptoms is plotted against an 18-point y axis, rather than the full 60-point MADRS scale. Researchers have determined that a 6-point difference in MADRS scores is the “minimum difference” that is clinically significant (or even clinically noticeable.) If you chart the outcomes with a 60-point scale, you can immediately see why this is so.

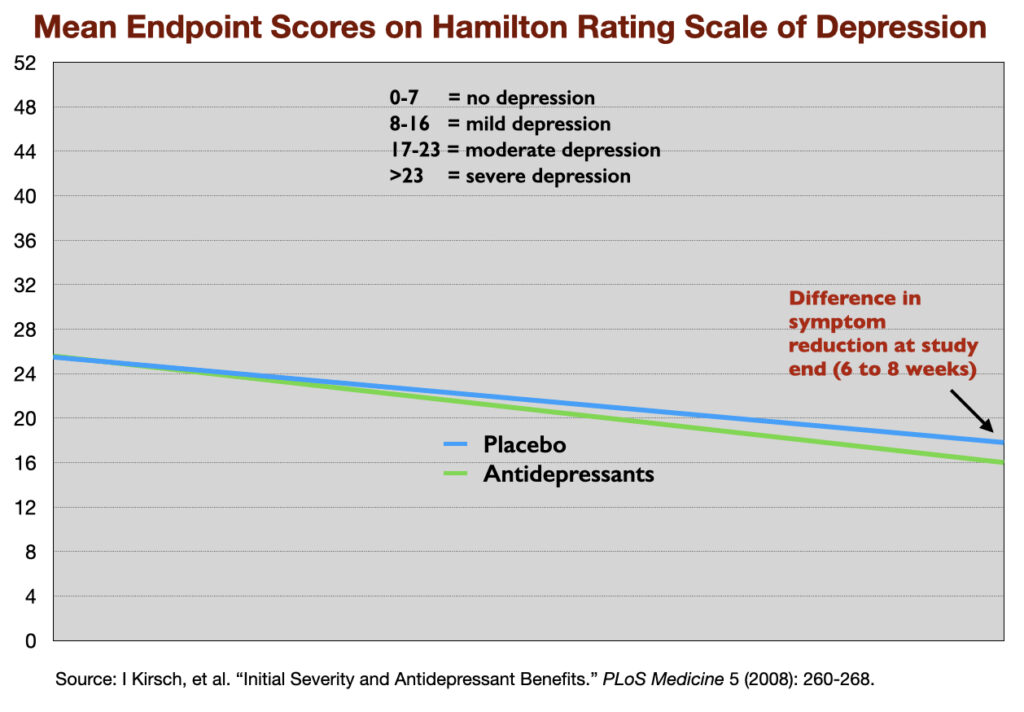

This lack of clinical significance has shown up repeatedly in meta-analyses of antidepressant trials. In 2008, Irving Kirsch and colleagues reviewed 47 trials of four SSRIs, and determined that there was a mean reduction of 9.6 points on the 52-point HRSD in the antidepressant group, and 7.8 points in the placebo group, a difference of 1.8 points. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence had set a 3-point difference on the HRSD as the minimum difference that could be seen as clinically significant.

More recent meta-analyses have come to the same conclusion. The Danish study of 131 trials found a mean difference of 1.94 points, which, the investigators noted, “was below our predefined threshold for clinical significance of three points.” The Nordic Cochrane Centre, in their review of the Lancet paper, determined that the mean difference between the drug and placebo arms was 1.97 points. They too noted that “clinicians are unable to detect reductions on the Hamilton depression rating scale of three points or less.”

Thus, the very meta-analysis that newspapers touted as proving, once and for all, that antidepressants work, actually told of a difference, between drug and placebo, so small that clinicians wouldn’t be able to notice it, and this was in trials known to be biased against placebo.

The majority of patients in RCTs remain depressed

Although the patients treated with an antidepressant in the RCTs show a reduction in symptoms, at the end, the majority remain depressed. For instance, in the vortioxetine trial, the mean MADRS score for those who received the 20 mg dose—the dose that was deemed efficacious—was 18. This score is at the top end of the range of scores for mild depression (scores 7 to 19).

Although Kirsch and colleagues in their 2008 report didn’t provide a composite endpoint score for the patients in their meta-analysis, they did report endpoint scores in 35 of the trials, and if you average those scores, the mean for the antidepressant arm is 16.0, which is categorized as “mild to moderately depressed.”

Effect-size analyses reveal that 8 of 9 patients treated with an antidepressant suffer “harm”

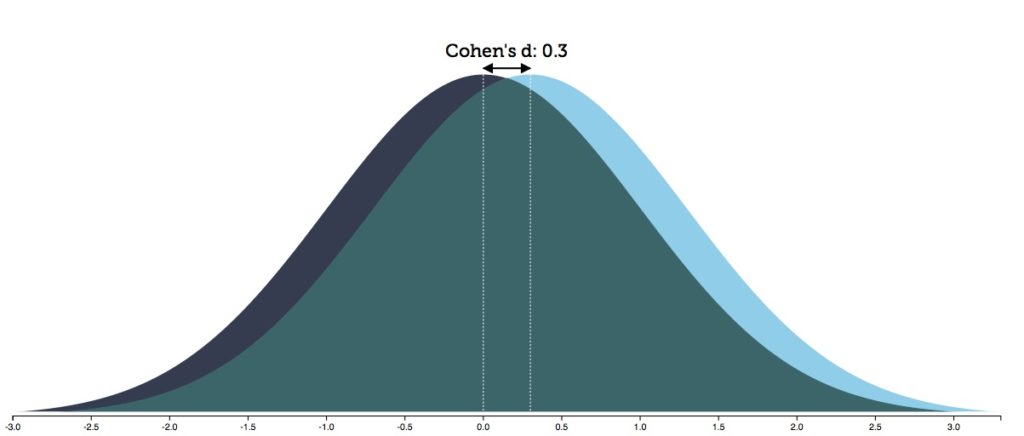

The RCT data, when carefully parsed, provide a method for assessing a “benefit/harm” equation for patients. Kirsch, the Danish investigators, and others have calculated that the 2-point difference in symptoms equates to an effect size of 0.3. An effect size of 0.3 means that there is an 88% overlap in the spectrum of outcomes for the drug and placebo group.

A related calculation that investigators make is the “number needed to treat” (NNT): how many patients must be treated with a drug to produce one additional responder beyond placebo? With an effect size of 0.3, that translates into an NNT of 9. Thus, the bottom-line risk/benefit equation that emerges from RCTs of antidepressants: One of nine patients will receive a benefit beyond placebo. The other eight will receive no additional benefit, yet are exposed to the adverse effects of the drug. This puts them into the “harmed” category. The nature of the possible harm can be seen in a compilation of the drug’s adverse effects, together with hazards associated with long-term use of antidepressants.

The Bottom Line

As can be seen, RCTs of antidepressants do not provide evidence that antidepressants “work.”

There is no comparison to outcomes in untreated patients; industry-funded trials produce exaggerated accounts of efficacy; the outcomes are not seen as predictive of outcomes in real-world settings; the placebo group is a drug-withdrawn group; the drug benefit over “placebo” is of no clinical significance; and NNT calculations reveal that eight of nine patients could be seen as “harmed” by the treatment.

Yet, such is the shine of RCTs that none of these shortcomings and failures derail the binary finding—that antidepressants are more “efficacious” than placebo—that guides societal use of these drugs. Indeed, if we return to the Kirsch report, here is an illustration of the single data point that psychiatry and society are relying on to claim that the drugs are an efficacious treatment for depression:

The Data that is Ignored

The RCT data is one element in a large pool of data that exists regarding the impact of antidepressants. The various “kinds” of data, when viewed separately, are like the pieces of a puzzle lying about, and any assessment of the evidence base for antidepressants should seek to see how they fit together. What is the big picture?

In my book Anatomy of an Epidemic, and in two previous Mad in America essays, I put the pieces of the puzzle together in a narrative manner that told of how, prior to the arrival of “antidepressants,” depression was understood to be an episodic disorder, and that after antidepressants became the first-line treatment, depression began to run a chronic course, with researchers eventually presenting a biological explanation for why the drugs might have this effect.

What follows are simply the pieces of the puzzle that exist in the medical literature (beyond the RCTs), without any effort by me to draw a conclusion. This is information that psychiatry—and thus society—ignores when it puts our societal focus on the RCT data. The purpose here is to illuminate the myopia of that focus, and how it ill serves our society.

The natural course of depression

The natural course of an “illness” serves as a necessary baseline for assessing whether an intervention is helpful. For instance, imagine that in nature, 50% of patients struck with an illness have recovered at the end of one year. A medical intervention needs to produce a higher recovery rate than that to provide a benefit. If a medical intervention leads to a one-year recovery rate of 40%, clinicians—if they don’t have a sense of the natural recovery rate—will likely see their intervention as effective. The 40% of patients who have recovered will see it that way too. Yet, in fact, the medical intervention has reduced the recovery rate, a fact that will remain hidden without knowledge of the natural course of the disorder.

Prior to the introduction of antidepressants, depression was understood to be a fairly uncommon disorder. Community surveys in the 1930s and 1940s found that fewer than one in a thousand adults suffered a bout of clinical depression each year. Studies of hospitalized patients told of how the depressive symptoms regularly waned with time, and often never returned.5

In 1972, Samuel Guze and Eli Robins at Washington University Medical School in St. Louis reviewed the scientific literature and determined that in follow-up studies that lasted ten years, 50% of people hospitalized for depression had no recurrence of their illness. Only a small minority of those with unipolar depression—one in ten—became chronically ill, they concluded.6

This was the scientific evidence that led NIMH officials and others, during the 1960s and 1970s, to speak optimistically about the long-term course of the illness. Here is a sampling of such pronouncements:7

• “Depression is, on the whole, one of the psychiatric conditions with the best prognosis for eventual recovery with or without treatment. Most depressions are self-limited.” –Jonathan Cole, director of the NIMH’s Psychopharmacology Service Center, 1964.

• “In the treatment of depression, one always has as an ally the fact that most depressions terminate in spontaneous remissions. This means that in many cases regardless of what one does the patient eventually will begin to get better.” –Nathan Kline, director of research at Rockland State Hospital in New York, 1964.

• Most depressive episodes “will run their course and terminate with virtually complete recovery without specific intervention.” – Dean Schuyler, head of the depression section at the NIMH, 1974.

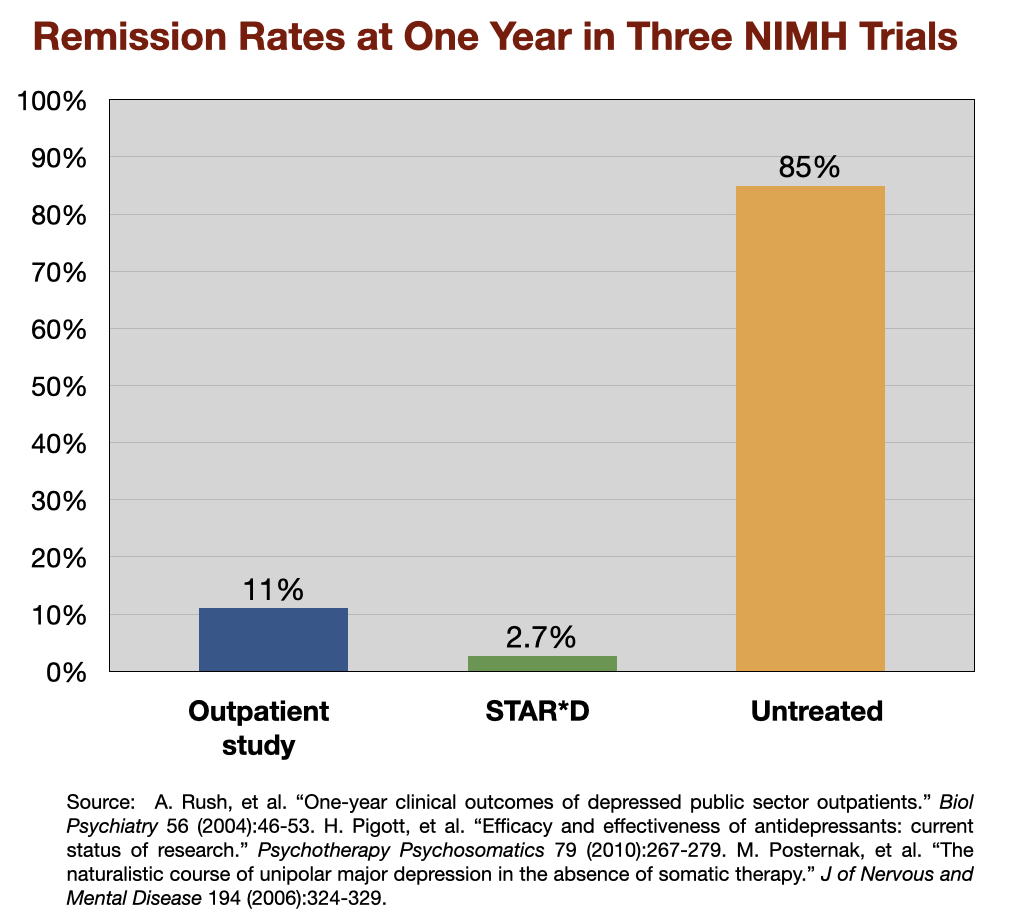

Indeed, spontaneous remission was so common that Schuyler concluded that it would be difficult to “judge the efficacy of a drug.” Perhaps a drug could shorten the time to recovery, as spontaneous remission in hospitalized patients often took many months to happen, but it would be nearly impossible to improve on the high remission rate—85% or so—at the end of one year.

Outcomes in real-world patients treated with antidepressants

In the 1970s, benzodiazepines were the drug of choice for “anxiety” and other emotional discomforts. The benzodiazepines fell out of favor because of their addictive qualities, and soon antidepressants became the drug of choice, and this was particularly true after Prozac’s arrival in 1988.

During the 1990s, psychiatrists in the US and elsewhere fleshed out the spectrum of outcomes associated with antidepressants. One third of all unipolar patients were non-responders to the drugs and had poor long-term outcomes. Another third were “partial responders” to the drugs, and in short-term trials, showed up as being helped by the drug. The problem was that these patients subsequently relapsed frequently. The final third remitted over the short term, but only about half stayed well.

The American Psychiatric Association’s 1999 textbook summed up this spectrum of outcomes:

“Only 15% of people with unipolar depression experience a single bout of the illness,” the textbook noted, and for the remaining 85%, with each new episode, remissions become “less complete and new recurrences develop with less provocation.”8

Around this time, the NIMH funded three studies to newly assess the one-year outcomes of “real-world” patients treated for depression. In two of the studies—the first a study of 118 outpatients in Texas; the second the large STAR*D study—all patients were treated with antidepressants, and both protocols were designed to maximize remission rates. The third was a study of 84 patients to assess the “untreated course of depression.” The remission rates at the end of one year were as follows:

The lead investigator for the “untreated” study, Michael Posternak, concluded that the results reflected the outcomes reported by Emil Kraepelin nearly a century earlier. Kraepelin had observed that untreated depressive episodes usually cleared up within six months, and this new study, he wrote, provided “perhaps the most methodologically rigorous confirmation of this estimate.”

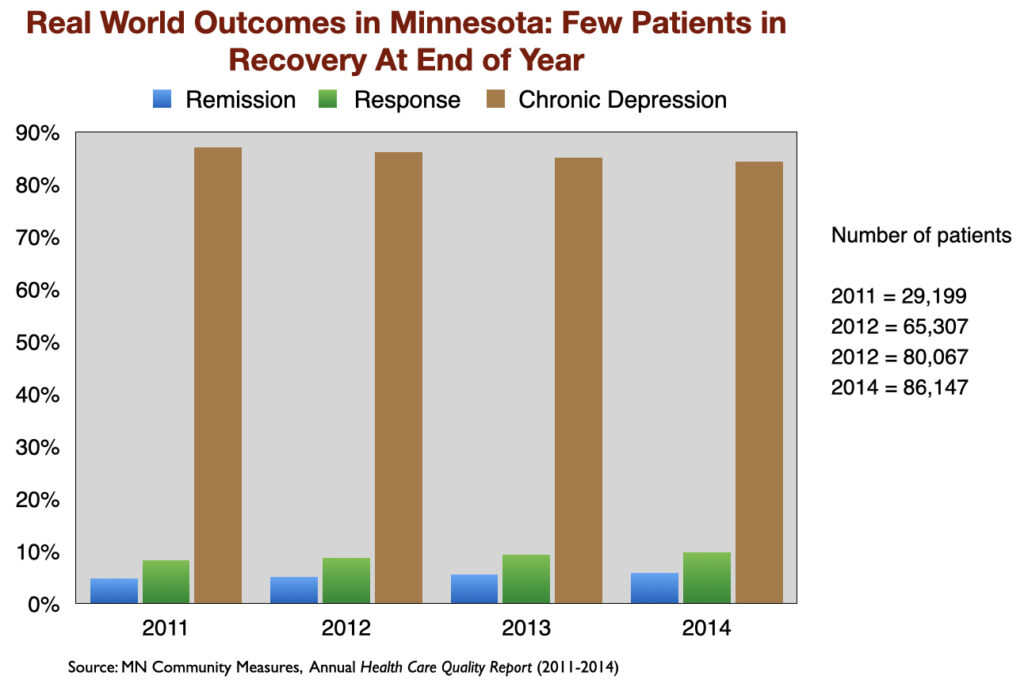

The poor results that showed up in the two NIMH-funded studies have been replicated in other “real-world” settings. For instance, a Minnesota report on the real-world outcomes of 260,000 patients treated for depression from 2011 to 2014, by medical providers around the state, found similarly low remission rates. At the end of each year, only about 5% of the patients were in remission. Another 10 percent or so were considered responders to antidepressant treatment (50% drop in symptoms.) The remaining 85% were categorized as chronically depressed.

Two studies published in 2022 complete this picture of poor outcomes in real-world patients:

- In a 2022 international study of 1,279 patients, which was funded by Lundbeck and conducted by investigators with numerous ties to pharmaceutical companies, only 25% responded to antidepressant treatment. The rest were either non-responders (34%) or deemed to have become “treatment resistant” after failing twice to respond to an antidepressant (41%).

- In a study of 1,944 patients at 22 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, which involved testing for possible gene-drug interactions with the hope that it could boost response rates, the composite response rate for the two groups was 30%, with the genetic testing proving to be of little value.

Medicated vs. Unmedicated Outcomes

During the past 25 years, researchers in Europe, Canada and the United States conducted a small number of “naturalistic studies” that assessed outcomes for depression based on their use of antidepressants. These investigations regularly found that the medicated patients are more likely to be depressed and functionally impaired.

Here are quick summaries of ten such studies.

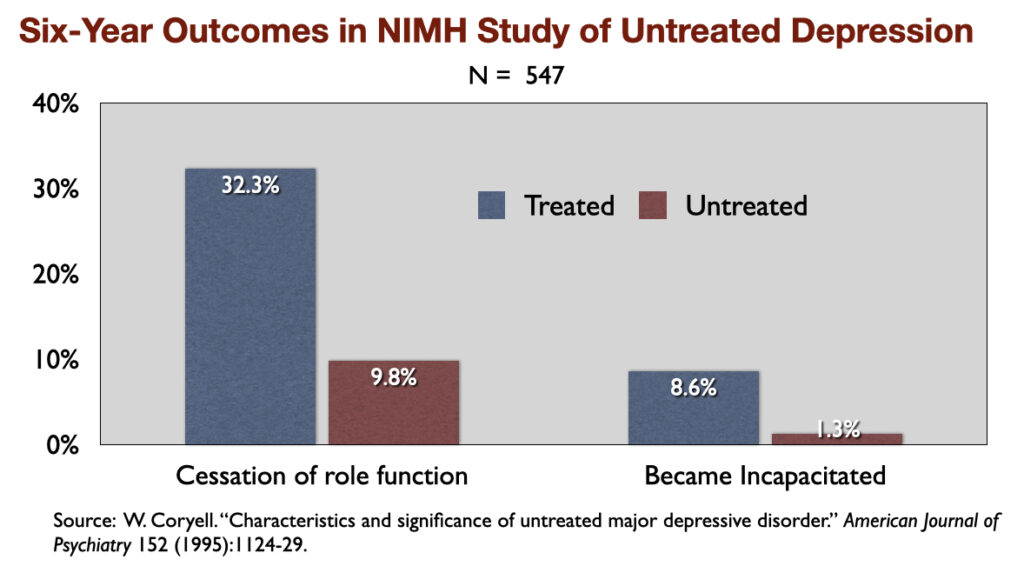

1) “Characteristics and Significance of Untreated Major Depressive Disorder” (1995). NIMH-funded investigators reported that over a period of six years, those who were “treated” for the illness were three times more likely than the untreated group to suffer a “cessation” of their “principal social role” and nearly seven times more likely to become “incapacitated.”

The NIMH researchers wrote: “The untreated individuals described here had milder and shorter-lived illness (than those who were treated), and, despite the absence of treatment, did not show significant changes in socioeconomic status in the long term.”

2.) “Outcome of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Primary Care” (1997). In a British study of 148 depressed patients, the never-medicated group saw their symptoms decrease by 62% in six months, whereas the drug-treated patients experienced only a 33% reduction in symptoms.

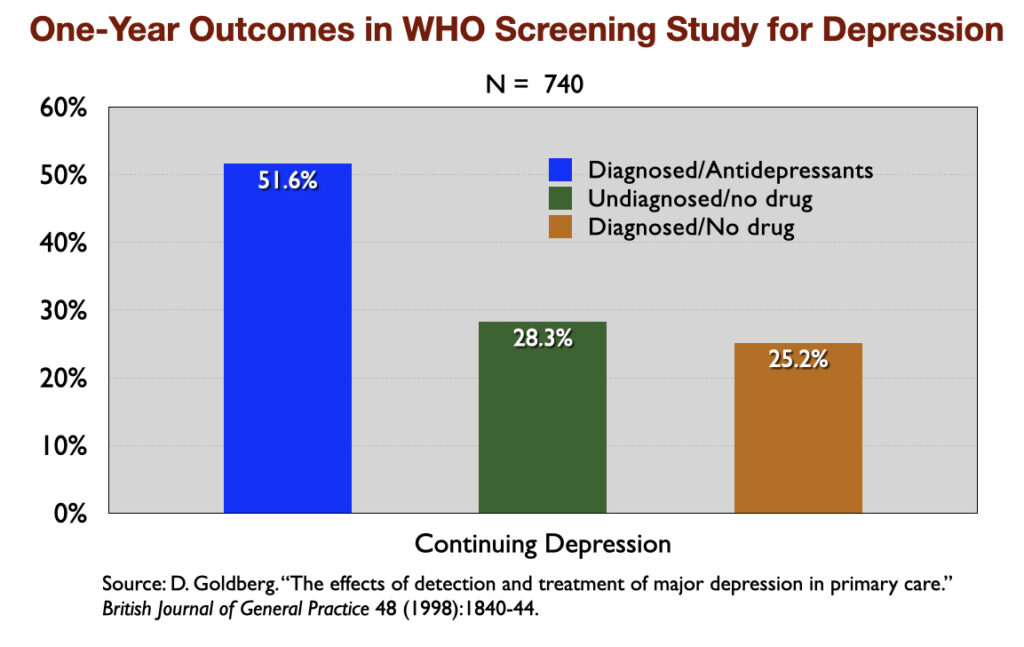

3. “The Effects of Detection and Treatment on the Outcome of Major Depression in Primary Care” (1998). A World Health Organization study of depressed patients in 15 cities around the world found that, at the end of one year, those who weren’t exposed to psychotropic medications enjoyed much better general health, their depressive symptoms were much milder, and they were less likely to still be “mentally ill.”

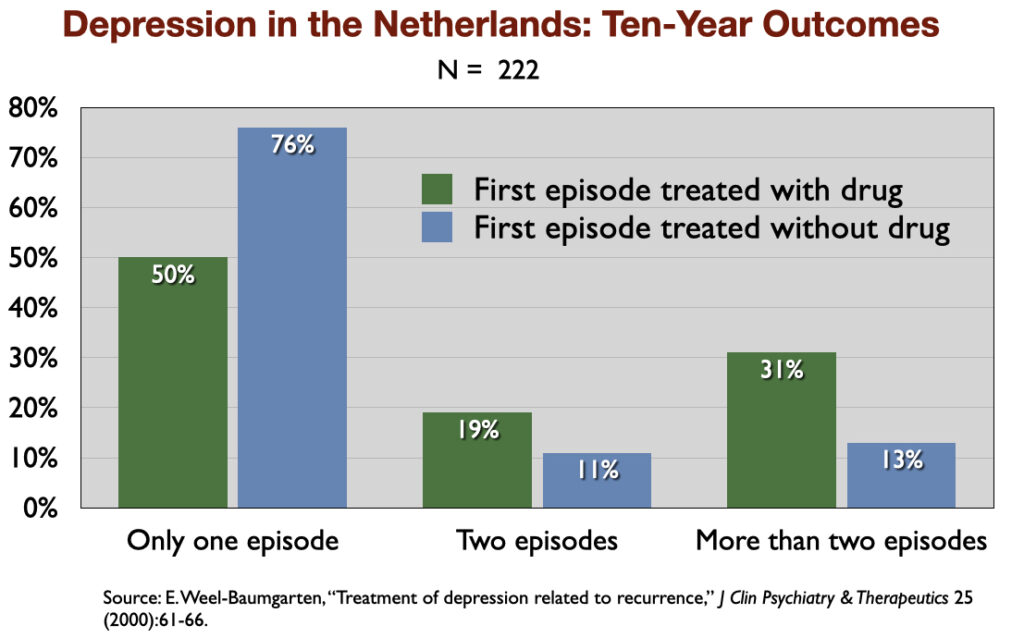

4. “Treatment of Depression Related to Recurrence” (2000). In a retrospective study of 10-year outcomes, Dutch investigators found that 76% of those not treated with an antidepressant recovered and never relapsed, compared to 50% of those prescribed an antidepressant.

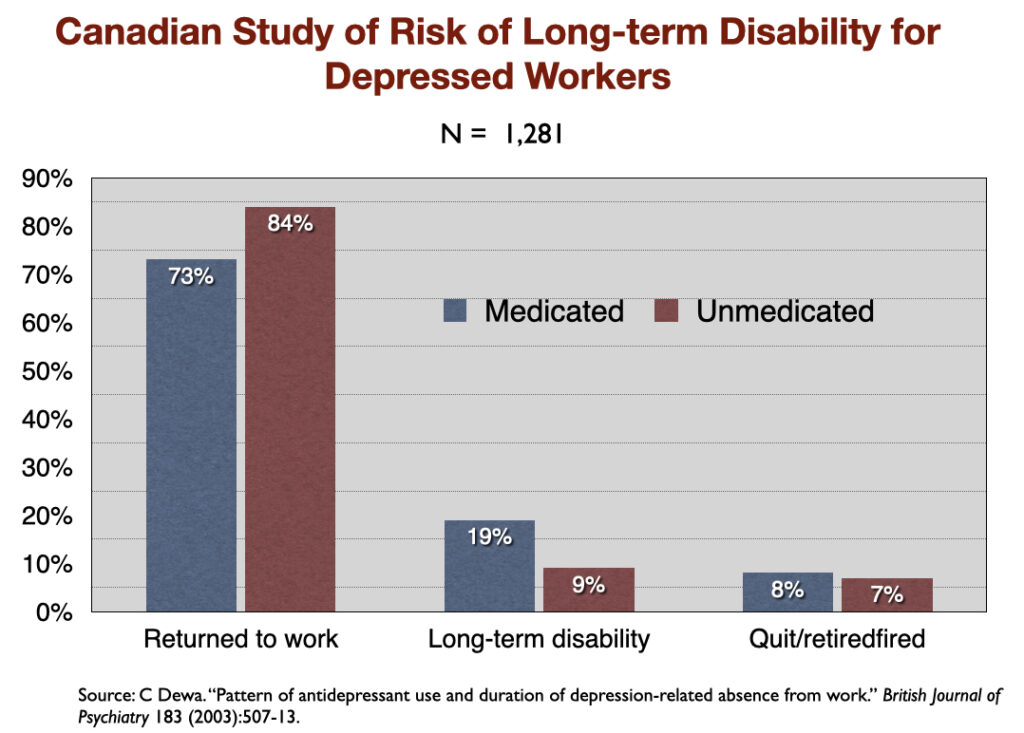

5. “Pattern of Antidepressant Use and Duration of Depression-Related Absence from Work” (2003). Canadian investigators identified 1,281 people who went on short-term disability between 1996 and 1998 because they missed ten consecutive days of work due to depression. Those who didn’t fill a prescription for an antidepressant returned to work, on average, in 77 days, while the medicated group took 105 days to get back on the job. Only 9% of the unmedicated group went on to long-term disability, compared to 19% of those who took an antidepressant.

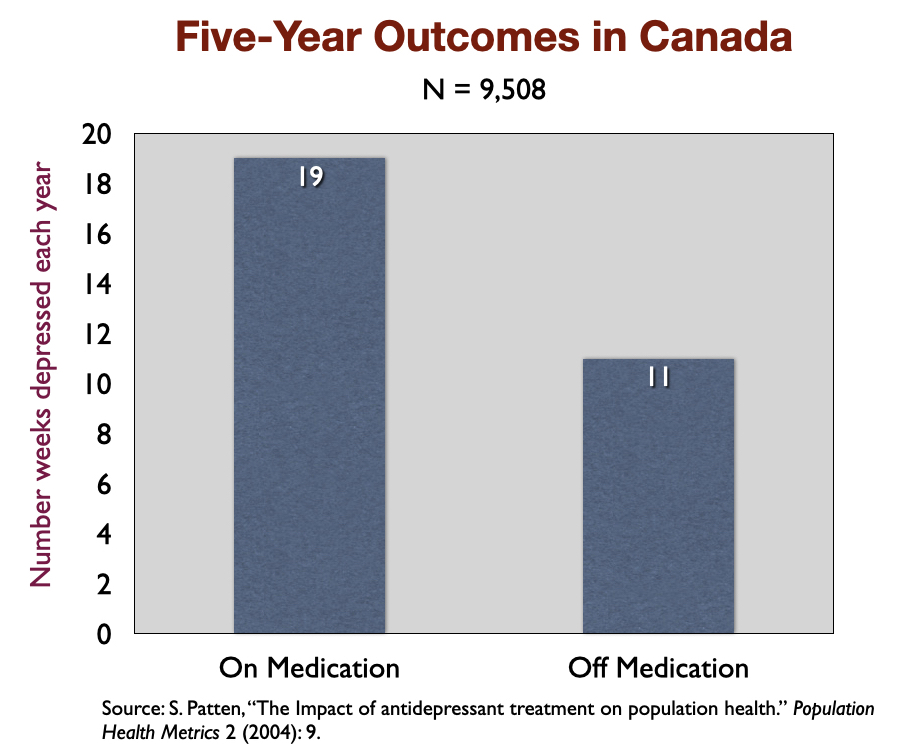

6. “The Impact of Antidepressant Treatment on Population Health” (2004). In a five-year study of 9,508 depressed patients in Canada, medicated patients were depressed on average 19 weeks a year, versus 11 weeks for those not taking the drugs. The Canadian investigators concluded that “antidepressant treatment may lead to a deterioration in the long-term course of mood disorders.”

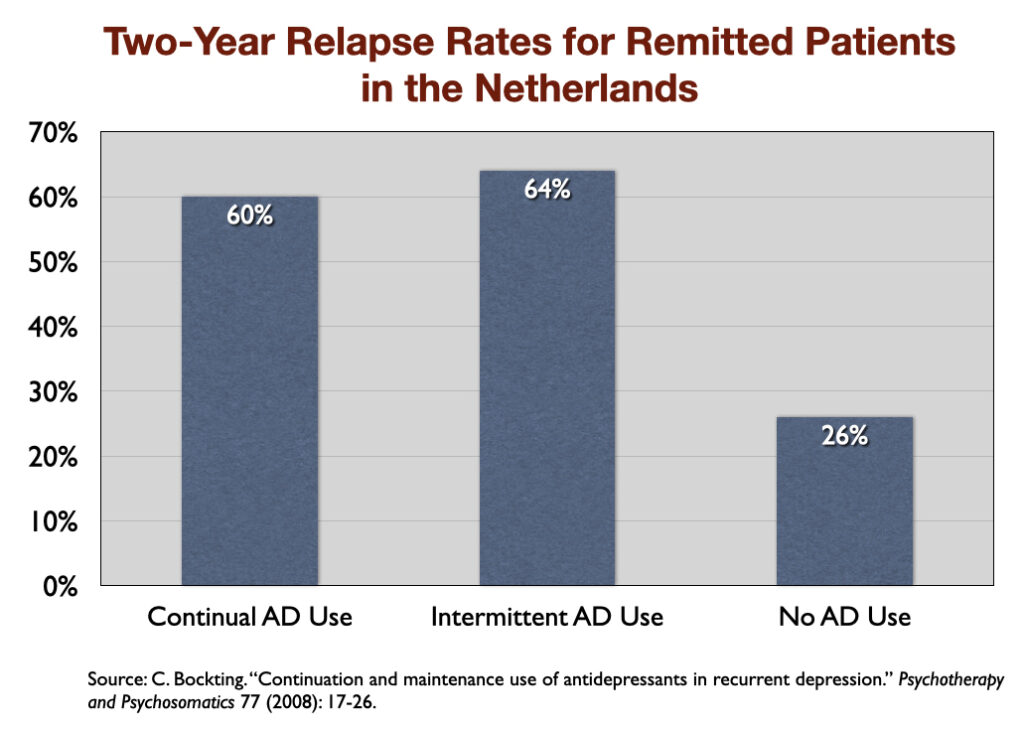

7. “Continuation and Maintenance Use of Antidepressants in Recurrent Depression” (2008). Researchers in the Netherlands followed 172 patients for two years after their depression had gone into remission, and found that during this follow-up the relapse rate was 60% for those who continuously took an antidepressant, 64% for those who intermittently took one, and 26% for those who didn’t take an antidepressant at all.

8. “Impact of Duration of Antidepressant Treatment on the Risk of a New Sequence of Antidepressant Treatment” (2011). French researchers, in a study of 35,000 first-episode patients, found that the longer patients were treated with an antidepressant before withdrawing from the drug, the higher the rate of relapse. Those who were exposed to an antidepressant for longer than six months had more than twice the risk of relapse than those exposed for less than one month.

9. “Poorer Long-Term Outcomes Among Persons with Major Depressive Disorder Treated with Medication” (2017). An analysis of the outcomes of 3,294 people who were diagnosed with depression and followed for nine years revealed that those who took antidepressants during that period had more severe symptoms at the end of nine years than those who didn’t take such medication. The difference in outcomes could not be explained by any difference in initial severity of depression.

10) “Antidepressant Use Prospectively Relates to a Poorer Long-Term Outcome of Depression” (2018). A prospective study of 521 depressed patients in Switzerland, who were followed from age 20 to age 50, found that taking an antidepressant at some point during that period was associated with worse outcomes at the end of the study, even when controlling for initial symptoms and other factors.

Adverse Effects

The NNT that emerges from the RCTs of antidepressants tells of how eight of nine depressed patients treated with an antidepressant do not receive any benefit from the drug (in terms of symptom reduction beyond placebo), and yet are exposed to the hazards of the medication.

The list of known side effects associated with antidepressants is long. It includes numerous physical, emotional, and psychiatric adverse effects. The biggest risk, however, is that exposure to an antidepressant will lead to a long-term worsening: a conversion to bipolar disorder, persistent sexual dysfunction, and chronic depression. Difficulties withdrawing from antidepressants increase the likelihood that an initial prescription will evolve into long-term use.

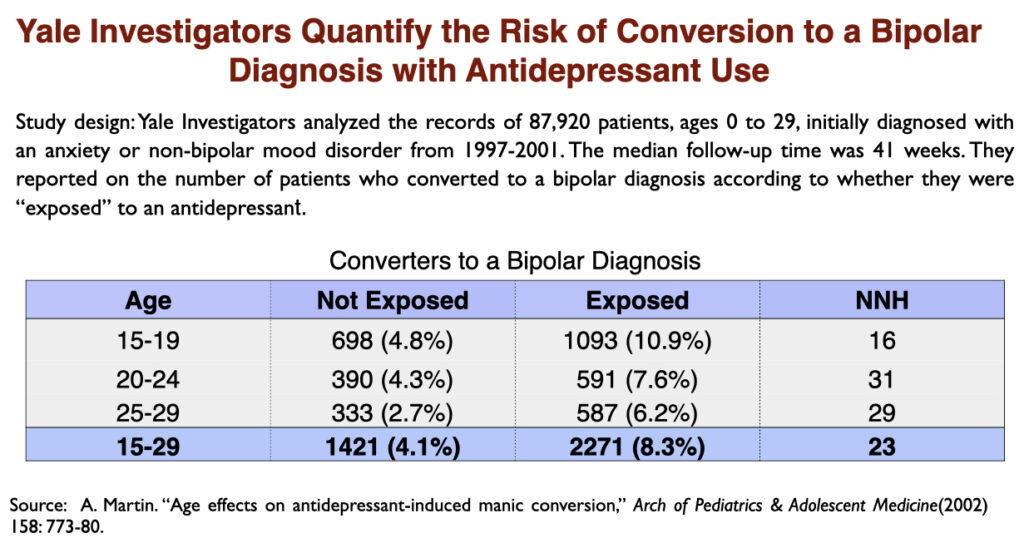

It has long been known that antidepressants can trigger a manic episode. This is an “adverse effect” that can convert “unipolar” depression into a bipolar diagnosis. In a 2002 paper, researchers at Yale University quantified the risk during a ten-month period: one of every 12 depressed patients exposed to antidepressants will convert to bipolar, which is double the rate of conversion in depressed patients not exposed to the drugs.

Up to 75% of SSRI users report some degree of sexual dysfunction—low libido, vaginal dryness, erectile dysfunction, and less intense orgasms. As Irish researchers wrote, “adverse sexual effects appear to be the rule, rather than the exception with SSRIs.” Moreover, even after withdrawing from an SSRI antidepressant, the sexual dysfunction may persist indefinitely, a condition known as PSSD: post-SSRI sexual dysfunction.

The risk of developing PSSD is not known. Sexual dysfunction can of course be devastating to the individual. From an evolutionary perspective, PSSD can be seen as a person being made “less fit” by the drug. A nation of people on SSRIs would not be a thriving population.

As noted above, in the pre-antidepressant era, recovery from a depressive episode was expected. After antidepressants were introduced, the long-term course of depression—as clinical studies revealed—began to run a more chronic course. By the early 1990s, researchers reported that 10% to 15% of patients diagnosed with major depression had become “treatment resistant.” This poor outcome continued to increase as the SSRIs were popularized, such that a 2006 survey concluded that nearly 40% of depressed patients who took antidepressants for a longer period ended up “treatment resistant.”

With depression running a more chronic course, and nearly 40% of patients ending up “treatment resistant,” Italian psychiatrist Giovanni Fava and a handful of others proposed a biological explanation for this decline in outcomes: SSRI and other antidepressants induce brain changes that make patients more biologically vulnerable to depression.

In a 2011 article, El-Mallakh, a mood disorders expert at the University of Louisville School of Medicine, summed up the hypothesis:

“A chronic and treatment-resistant depressive state is proposed to occur in individuals who are exposed to potent antagonists of serotine reuptake pumps (SSRIs) for prolonged time periods. Due to the delay in the onset of this chronic depressive state, it is labeled tardive dysphoria. Tardive dysphoria manifests as a chronic dysphoric state that is initially transiently relieved by—but ultimately becomes unresponsive to—antidepressant medication. Serotonergic antidepressants may be of particular importance in the development of tardive dysphoria.”

He concluded that drug-induced tardive dysphoria could “continue for a period of time after discontinuation of the medication, and may not be reversible.”

While many people exposed to antidepressants are able to quit the drugs without too much difficulty after a shorter period of use, extended use can lead to a “discontinuation syndrome” when people try to come off the medication. Withdrawal symptoms, researchers wrote in a 2022 paper, include flu-like symptoms, anxiety, emotional lability, lowering of mood, irritability, bouts of crying, dizziness, shaking, fatigue, and electric shock sensations. The symptoms usually persist for weeks and can last months or even years. Half of the patients who experience withdrawal effects rate the symptoms as “severe.”

Public Health Outcomes

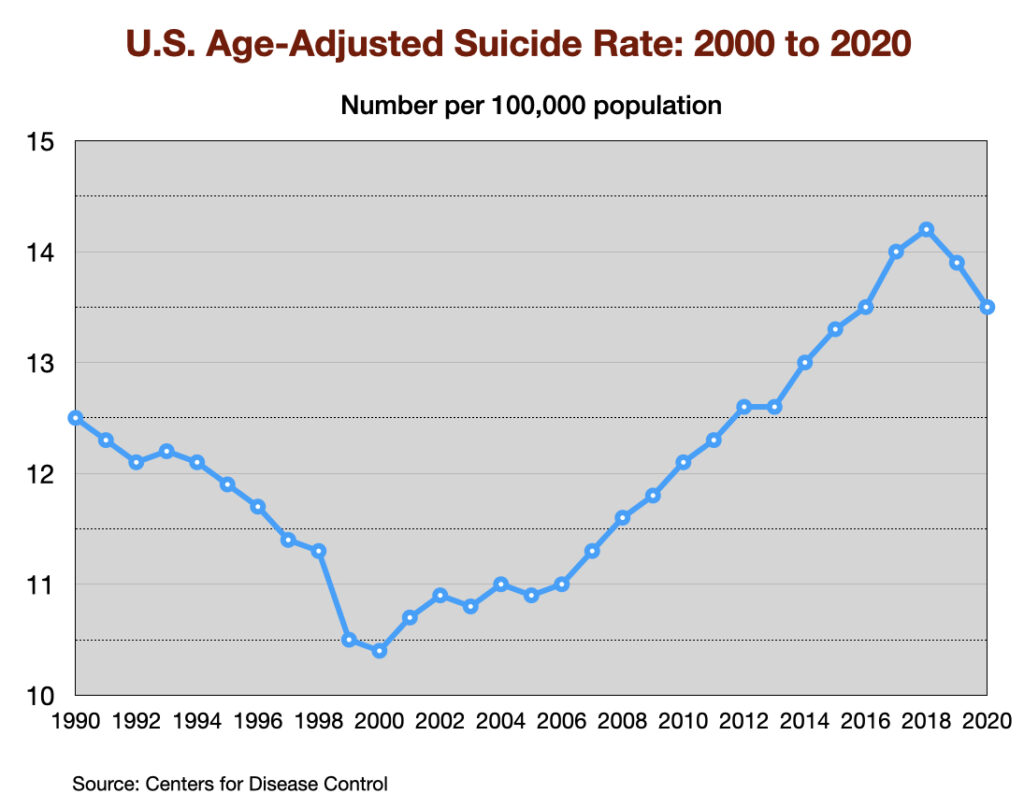

If antidepressants “work”, the public could expect that the increased prescribing of these drugs over the past 30 years would have reduced the “societal burden of depression.” They would have provided a public health benefit: the economic burden would decrease (as more people were able to work); the suicide rate would decrease; and disability rates would fall.

Yet, the opposite has proven true.

Antidepressant Use

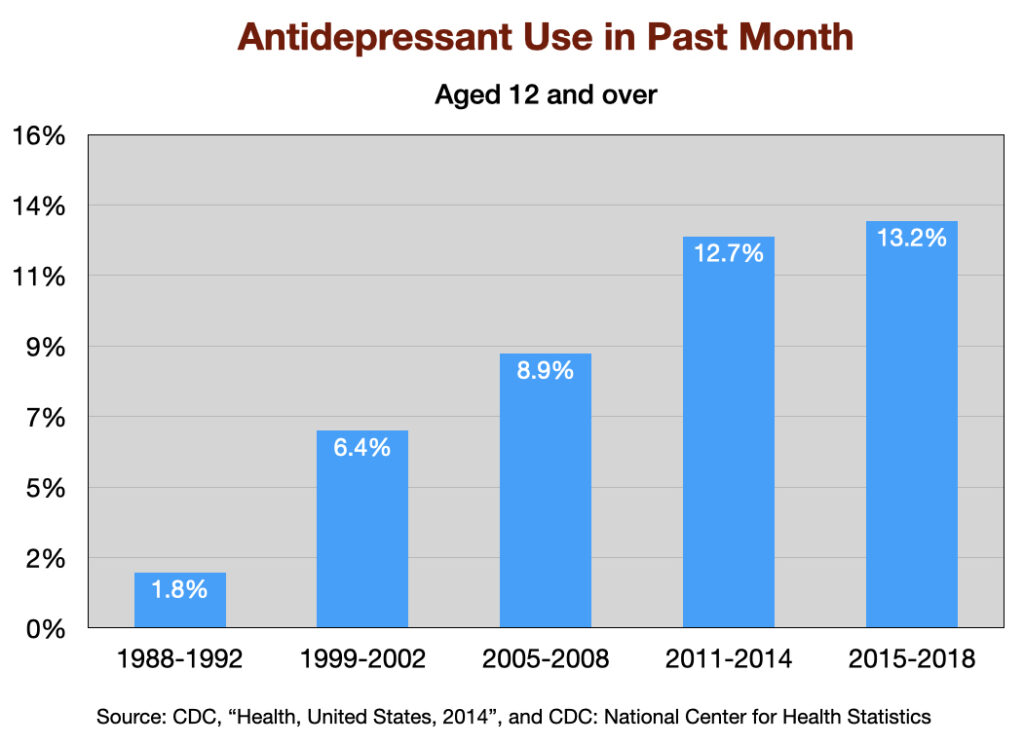

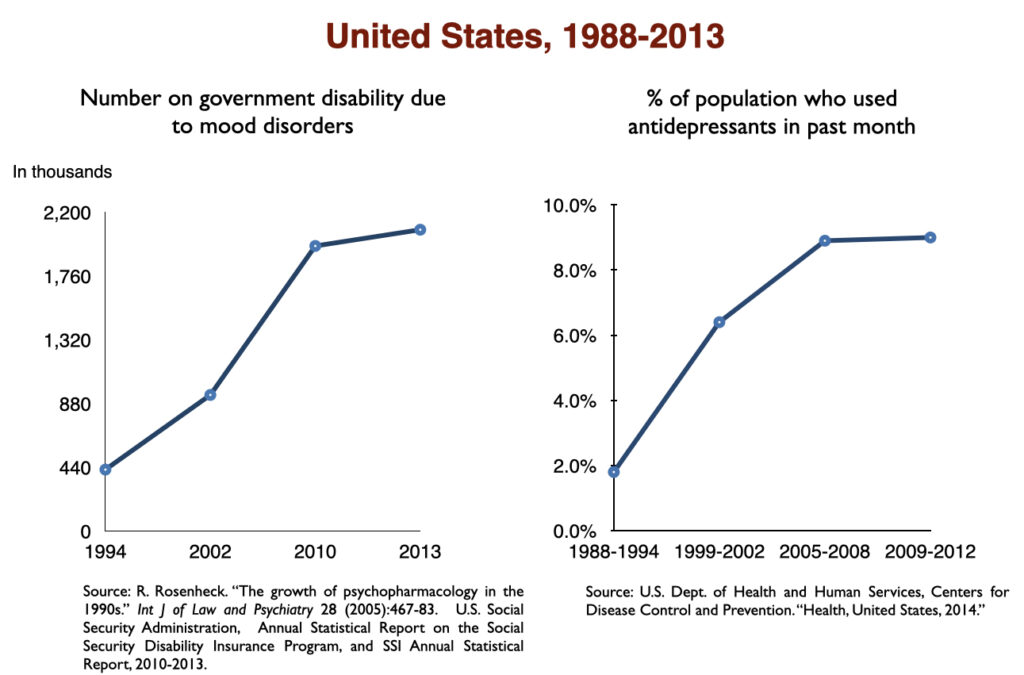

The use of antidepressants has increased steadily since Prozac was introduced in 1988. The percentage of US adults aged 12 and over that used an antidepressant the “previous month” jumped seven-fold over this 30-year period.

Economic burden of depression

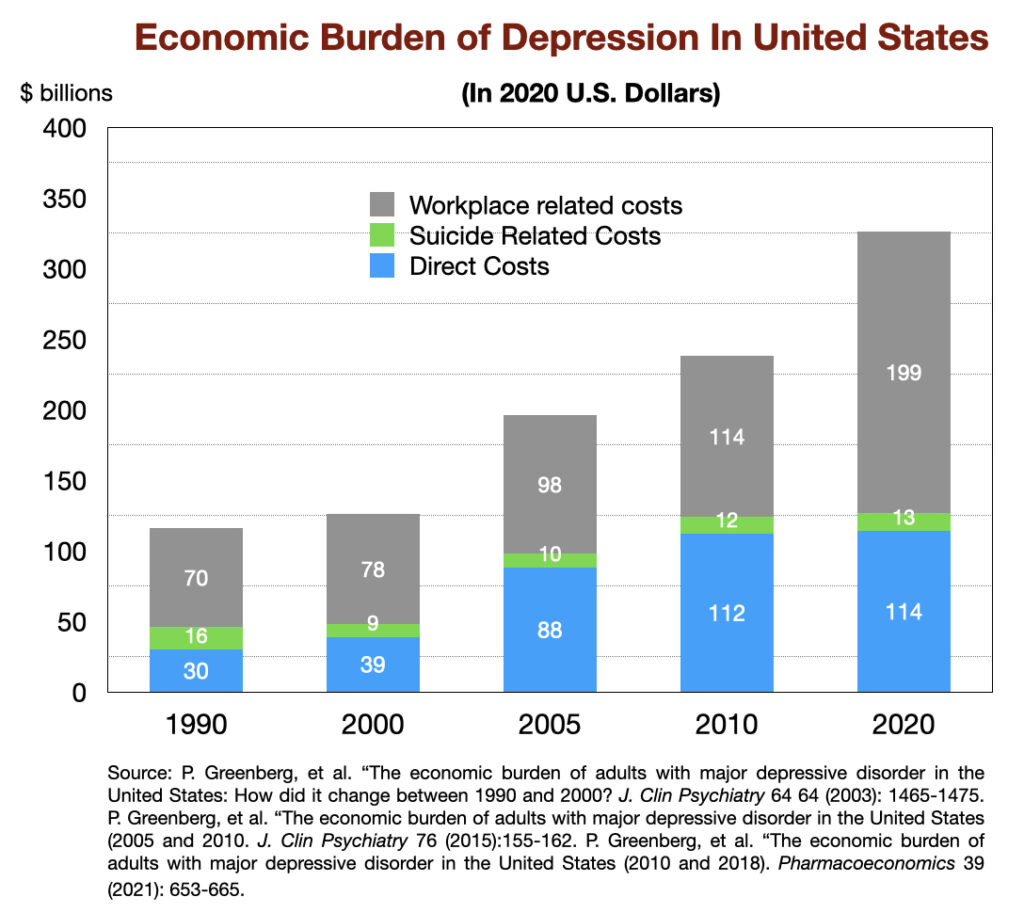

In 1990, the “economic burden” of major depression in US was calculated to be $116 billion (in 2020 dollars.) This tally is composed of direct spending on therapy and medications, as well as residential care in facilities; suicide related costs; and workplace costs (loss of productivity due to depression.) This economic burden has increased three-fold since then, reaching $326 billion in 2018 (in 2020 dollars).

Suicide rates

There are a number of factors associated with changing suicide rates, with gun ownership and unemployment two principal factors. The suicide rate declined in the 1990s, and then rose steadily during the next two decades.

Antidepressants are expected to serve as a factor that lowers the suicide rate. However, two large cohort studies of depressed patients in primary care settings (one in the US and one in the UK) reported much higher suicide rates for depressed patients who took an antidepressant. A third study in the UK of first-episode depressed patients found a much higher suicide rate while they were on the drug or during the first four weeks after quitting the medication (drug withdrawal period.)

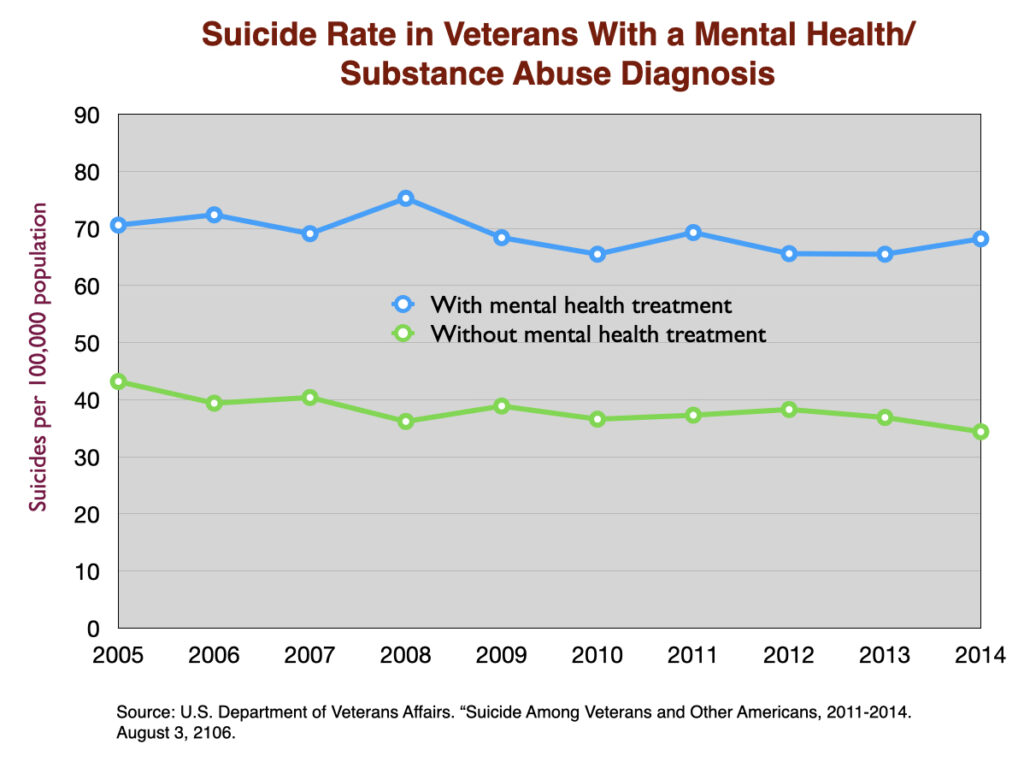

Similarly, a large study of US veterans diagnosed with a mental health condition found a 50% higher suicide rate in those who got treated for the condition.

The Bipolar Boom

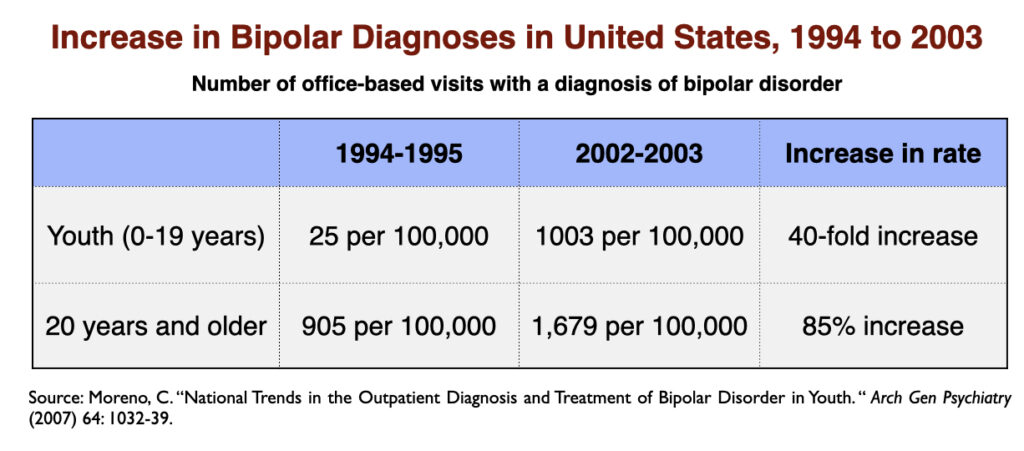

The rapid increase in the prescribing of SSRIs in the 1990s was accompanied by a notable increase in the prevalence of bipolar illness in our society. In the short span of a decade (1992-2003), the prevalence of bipolar in adults nearly doubled, and increased 40-fold in youth.

While the expansion of diagnostic boundaries contributed to this astonishing increase in bipolar illness, a survey of members of the Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association found that 60 percent of those with a bipolar diagnosis had initially presented with major depression and had turned bipolar after exposure to an antidepressant.

At a public health level, the rise in the number of “bipolar” patients tells of a worsening of societal mental health. Bipolar is understood to be a more serious disorder than depression or any of the other mood disorders; 85% are said to suffer from “serious impairment.”

Rise in Disability

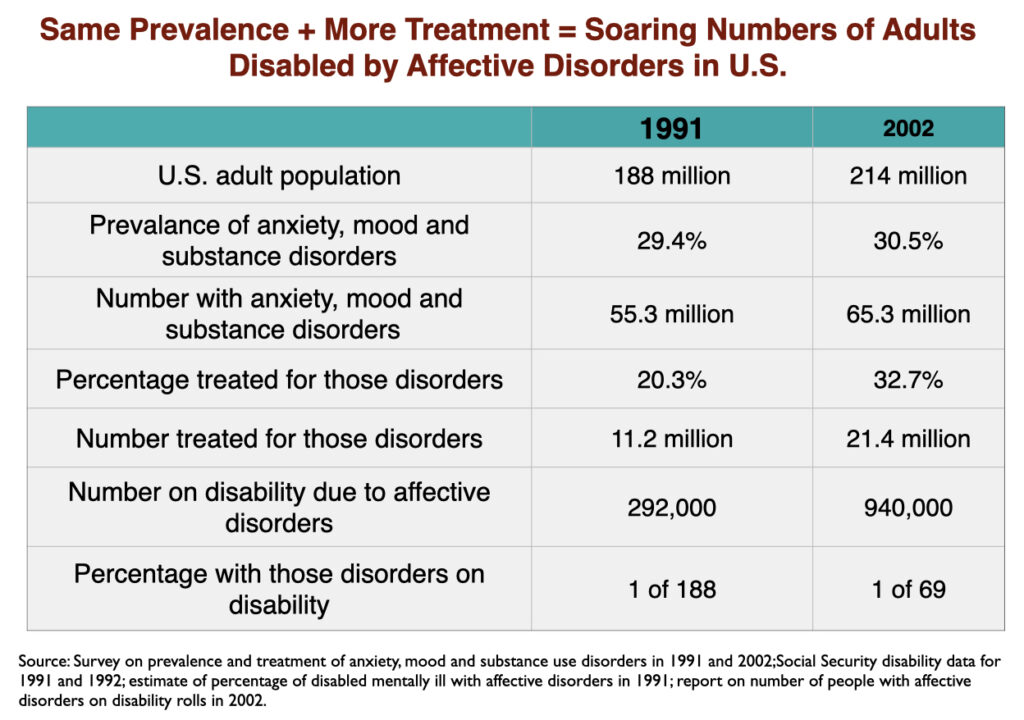

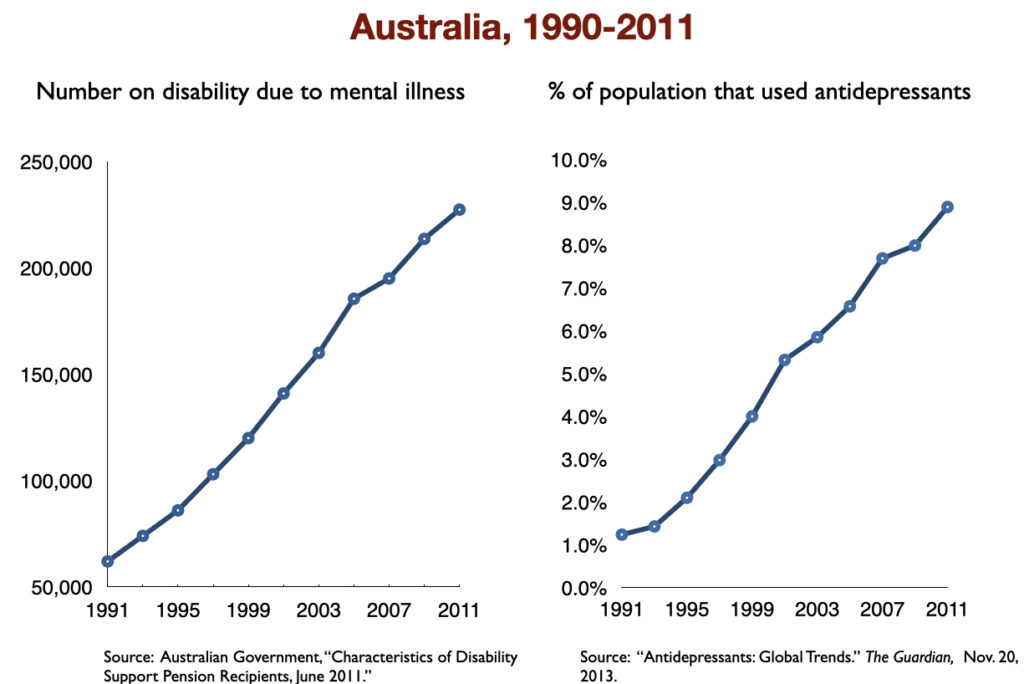

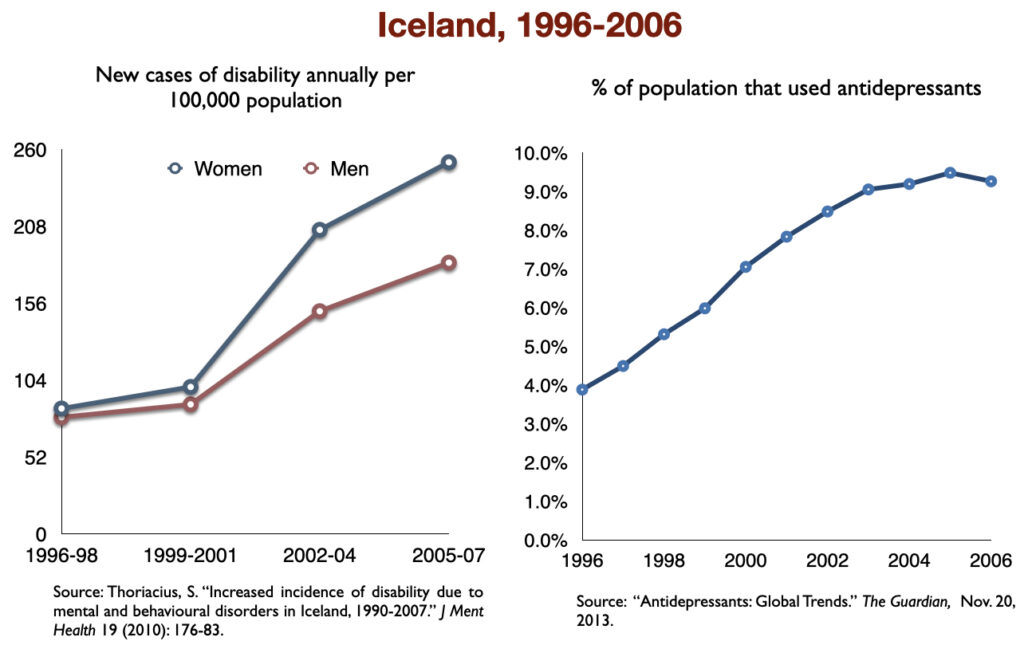

Two of the studies cited above in the section on “medicated vs. unmedicated outcomes” found higher disability rates for depressed patients who took antidepressants compared to those who did not. At a societal level, those studies served as a prediction that disability due to mood disorders would rise with increased use of antidepressants. That rise quickly showed up in the 1990s, when SSRIs became top-selling drugs.

While the percentage of US adults suffering from mood disorders did not change from 1991 to 2002, the percentage who got treatment did. In other words, the prevalence of mood disorders remained the same; the difference was that the number of adults treated for a mood disorder rose from 11.2 million in 1991 to 21.4 million in 2002. As this occurred, the number of adults receiving a federal disability payment—SSI or SSDI—due to a mood disorder jumped from 292,000 to 940,000. In the short span of a decade, the disability rate for adults with mood disorders rose from 1 in 188 to 1 in 69.

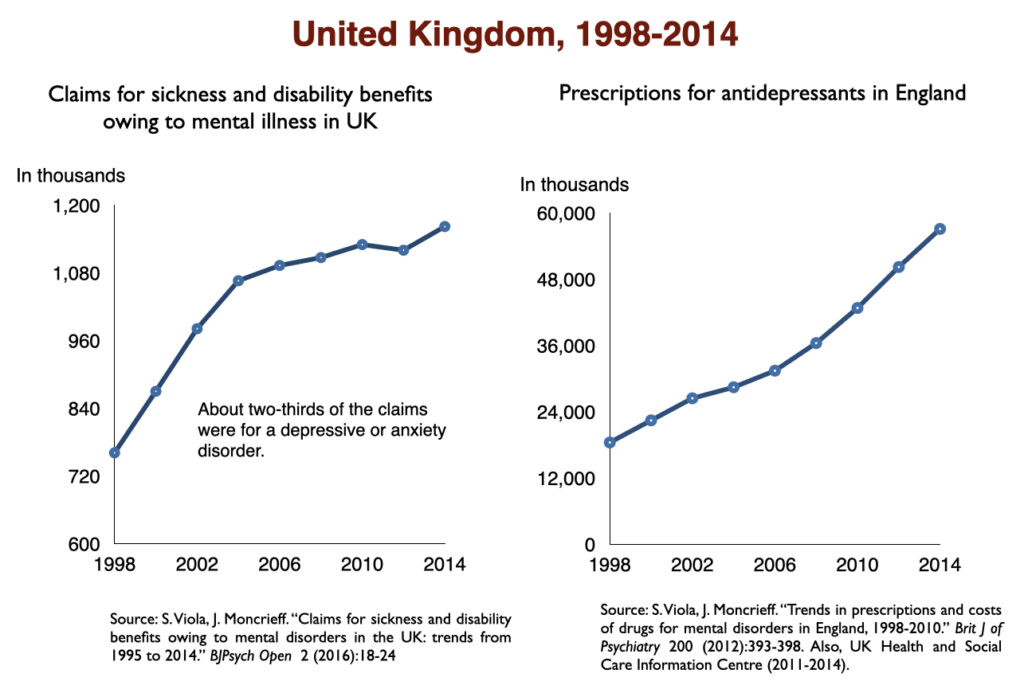

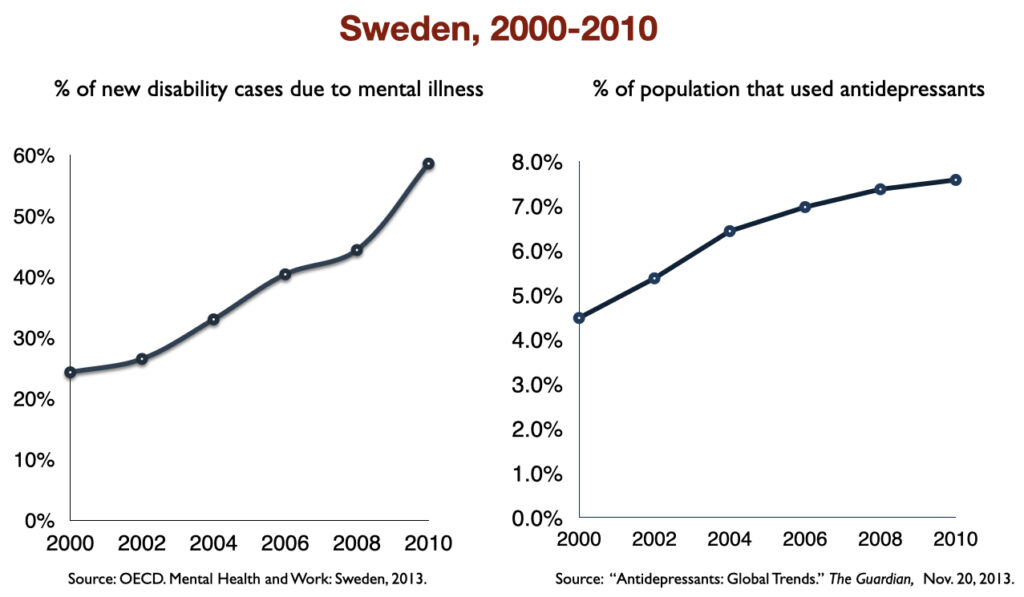

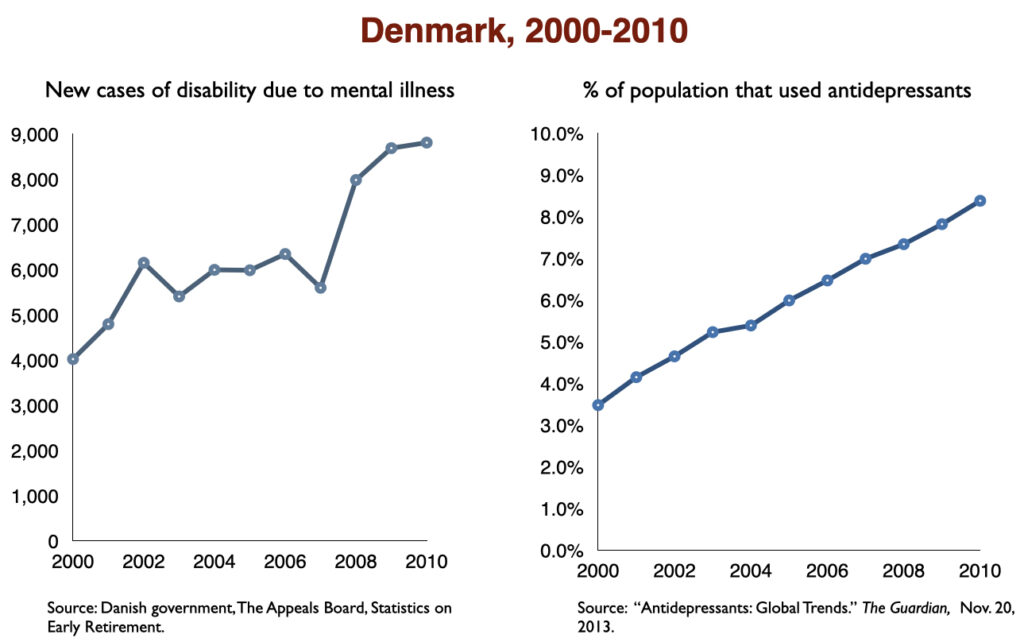

In 2016, a work group in the UK Parliament invited me to give a presentation on the rise of disability due to mood disorders, as this was occurring in the UK too. At that time, I collected data on increases in antidepressant use and disability rates in six countries.

Such are the public health outcomes associated with the increased use of antidepressants in the past 30 years. The economic burden of depression more than doubled; the suicide rate steadily increased during the past two decades; there was a “bipolar boom,” and disability rates due to mood disorders soared in country after country that adopted widespread use of the drugs.

The Pieces of a Puzzle

As I wrote earlier, the various types of evidence regarding the impact of antidepressants are like the pieces of a puzzle. The hope is that the pieces will fit together to present a clear “evidence-based” picture of their merits.

In this instance, here are the pieces of puzzle:

- In RCTs, antidepressants provide a “statistically significant” greater reduction of symptoms over the short term compared to placebo.

- The difference in symptom-reduction is so small that it is clinically insignificant and would not be noticeable by clinicians or patients.

- Most of the RCTs are industry funded and biased in ways that favor the drug.

- Based on “effect size” calculations, eight of nine patients will not benefit from the antidepressant treatment (beyond placebo), and yet will be exposed to adverse effects associated with its use.

- In the pre-antidepressant era, depression was understood to run an episodic course. Most people could expect to recover. Once antidepressants were popularized, depression began to run a more chronic course.

- Studies in “real-world” patients find that only 25% to 30% “respond” to an antidepressant, and that remission rates at the end of one year are much lower (below 15%.)

- A study designed to assess recovery rates in “untreated” patients reported that 85% were well at the end of the year, similar to outcomes in the pre-antidepressant era.

- Naturalistic studies that assess outcomes according to antidepressant use regularly find that the medicated group has worse outcomes: they are more likely to remain symptomatic and more likely to become disabled by the disorder.

- At a public health level, the burden of depressive disorders has markedly increased during the past 30 years.

The conclusion that “antidepressants” work comes from puzzle piece number one . . . that and an RCT fetish that puts the blinders on. RCTs have proven that antidepressants produce a “statistically significant” benefit over placebo in the short term, and the rest of the information can be dismissed. The deconstruction of the RCTs is put into the background of the conversation, and the rest of the information is dismissed as inferior to the RCT studies.

Such is the myopia that guides societal use of antidepressants.

A very different picture, of course, emerges when puzzle pieces two through nine are incorporated into the “evidence base.” Those pieces come together to tell of harm done and, one could argue, of harm on a vast scale. Even the RCT data now adds to that conclusion: it tells of drugs that, in trials biased by design to favor the drug, fail to provide a clinically significant benefit over the short term. If you take off the blinders, the scientific literature tells a very robust story about the efficacy of antidepressants and their impact on public health.

What is it about making drugs in a pharmaceutical lab that makes people think pharmaceuticals are less hazardous to their health than the nicotine in tobacco or the alcohol in fermented grapes?

Report comment

Superstitious belief.

Report comment

Whenever I noticed a sudden lifting of my depression I always had a cigarette in my hand at the time.

Report comment

Woops.

Who’s going to tell them? I’d be ready to run when they do. Unless they’re ready with a ‘marketing strategy’….. we have this pill …… it’s in the early stages of development……

Report comment

Yes, we have to get these drugs off of the market.

You used to be able see this on youtube, and his other one about Autism. Now you have to be in the UK and register for a free account to see them in full.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQsmynA18OU

In the first it is beyond anything one could fabricate. In Pittsburg, he talks with several families, but this one he lived with. The mother has a PhD and she used to be making regular trips to Paris. But now she says, “There is too much going on here.” So she has to stay home and they keep the 10yo drugged. They even keep their dog drugged. The boy seems like the very nicest when Lou talks with him. The boy does maybe seem kind of beaten down though. The father talks about the boy as though he is a terror, and he cites a suicide attempt.

The boy does kind of try to slip in an out of situations. Reading Françoise Dolto, she described such a boy as moving like a cat. And it is totally a product of the family environment he is living in.

But the doctor points out that the boy does not say hello or goodbye when he enters or leaves his office. And so his “illness” is effecting the course of his life and how people respond to him, so he needs to be on drugs.

As I see it, in these cases there are always two bodies of persons behaving completely unethically, the parents or guardians, and the doctors. And often it does go beyond unethically and into criminality. And that fact that we have mandatory reporting laws makes it even more likely that it is criminal.

But what makes it hard to prosecute is the doctor’s license certificate, framed and up on the wall.

The whole idea of mandatory reporting is that in most all cases of familial child abuse, doctors had long seen things that could not be proper, but they did not report, or they tried to solve the problem by talking to the parents themselves. Mandatory Reporting is supposed to solve this. But then when you have doctors becoming complicit in the fictional ailments, or advertising a position of parental exoneration, then the problem continues.

I had talked about this issue with someone I knew in County Social Services and she teaches their class on mandatory reporting, and she insists, “You report everything.”

It seems very different for the doctors in private practice, though the law and the issue are the same. They are just choosing to interpret the situations differently.

And then some minors will come of age and side with their parents and the drugging. “I have a mental illness.” Or “I have autism.”

And so likely so that they can side with the parents they will have children of their own and do the same or similar to them. That way they identify with those who have the power and never have to re-experience what it was like to have that kind of stuff done to them.

But these drug doctors hold government issued medical licenses, so this is a systemic and organized form of oppression, and clearly within Nuremburg Precedent.

Joshua

Report comment

Joshua explains how psychiatry and the legal system often play a big part in the continuation of intergenerational trauma.

Report comment

Very well put Birdsong.

As I see it the whole thing revolves around intergenerational trauma. The idea that someone is “mentally ill” seems to start in the family, and mostly it is about not measuring up to social expectations for the middle-class.

Joshua

Report comment

Thank you, Joshua.

I too, believe that a lot of what is called mental illness has to do with what happens in childhood, although it could be due to any number of things.

Report comment

R. D. Laing wrote a number of books which deal with this, and his views are not completely consistent. As I would explain it, he is not saying that childhood experience causes mental illness. That would only mean that you have to submit to treatment to get cured before you can have a voice.

No, childhood experience could not cause mental illness because there is no such thing as mental illness.

But childhood experience often does track people into situations where they are ripe for getting sucked into the mental health system, drugs, electroshock, lobotomy, and disclosing their affairs to a psychotherapist who is not licensed to practice law.

Joshua

Report comment

Thank you so much, Mr. Whitaker, for speaking the truths about the harms of the antidepressants, and pointing out the iatrogenic etiology of my “bipolar” misdiagnosis.

But the truth that the antipsychotics – which are the “schizophrenia” and “bipolar” treatments – can create both the positive and negative of “schizophrenia, via anticholinergic toxidrome and neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome, does also need to be exposed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

Report comment

Sadness used to be what you feel, when you feel it. A natural part of life. Before you make change in life, realizing something is not what you thought, or what you were told, and you have to redirect your attention, or rebel, or move away from something, you would go through this period. Or what you had to let go of. If someone dear to you passed away, it was something you went through, something that might even make the time you spent with the more dear to you. Now it’s a disease!? Something you push away from feeling it. Something you’re not supposed to want to feel. Added to that the treatment is more apt to make you suicidal, all added to the fact that it’s a disease, rather than if you just let it be you might find out what it’s telling you. I don’t think you can tell your doctor that someone you loved passed away, or that you’re going through anything, without possibly being offered this disabling substance.

HOW MUCH of what goes on in life is reflective of this. When there’s change that needs to take place, instead of people going through the period of sadness in order to integrate their feelings about it, in order to process how they feel, that this is made out to be a disease!? What kind of complacency to consumerism, and the marketing of social norms, and mob mentality, and the ability to feel or even process what we want in life are we robbed of? I remember commercials regarding social anxiety, and if you were uncomfortable going to the prom, this pill would help you. How much of stuff that’s simply unhealthy: what we eat, the social environment we think we need to compromise ourselves, to, the daily habits we take on, how much of this when it doesn’t please us is met with this magic pill so we don’t find out what the true result is of what we take into our lives?

Even in the arts, I’m sad to say. Even though I might sound like a disgruntled ogre. Music used to have a soothing sadness to it, a plaintive quality that allowed and got you to feel what’s in life beyond what you felt you needed to hold onto, that it’s all good. You could detach and just feel. What kind of preppy stimulant or aggressive maniac thrill seeking we’re assaulted with as art now, all genres of it all seeming to be more about what someone posts on their “social” media, what clothes they wear, what they keep hidden in their life, what bait the paparazzi catches, how they play the system, how they get others to think such debauchery is the good life, how you brainwash people with stimulant…..

It’s like an assault on honesty.

I’m not sad, I’m normal: “happy,” wind me up some more! CRANK THOSE GEARS!

https://journalnow.com/more-than-37-million-americans-take-antidepressants-authors-say/article_36f2f74b-e268-5731-bdc0-d92a036d2cd4.html

Report comment

Nijinsky says, “What kind of complacency to consumerism, and the marketing of social norms, and mob mentality, and the ability to feel or even process what we want in life are we robbed of?….It’s like an assault on honesty.”

Welcome to Madison Avenue, where consumer culture meets “science” –

Report comment

Woah! I just looked at how many people clicked on this link, which was 1111, and the amount of comments was 11, but then it switched to 1112. Apparently we are one past ones.

Birdsong, there’s not much science allowed regarding anti-depressants other than marketing.

I’ve had it twice that in encountering family members who lost a child, a mother and an uncle, that simply stating the real science regarding anti-depressants is something akin to trying to tell a pharisee they don’t need to slaughter another animal for whatever reason. How people don’t think that who knows what that for who knows what kind of reason has the deception of stress reduction (slaughter the oxen, and you’ve done something to appease “God” so no worries, and DAMN if there are others that just want to take that belief away from you)…. or it’s about doing that noble thing and promoting said fix, that good clean feeling like joining the army to fight another proxy war where those pumping it up, regardless which side they are funding, really don’t care much about anything other than what they can reap from a destabilized area, which is why they keep it going.

Anything and everything these days that’s a normal healthy response to the challenges of growth, or a catharsis that would lead towards a needed new outlook, it’s all dowsed with these magic pills.

Go to the mall, turn on netflix, God save the Queen, now the King or your favorite Hollywood star or sports hero, have you tried that new chocolate, lets go to that new fast food place, Oh that new fashion or technology is the rave, no lets try Disney…..

Who said that religion was the opium of the masses, that’s past history, now it’s brought to you by the drug companies and the marketing industry….

Report comment

Nijinsky says, “Who said that religion was the opium of the masses, that’s past history, now it’s brought to you by the drug companies and the marketing industry….”

YES!!!

Report comment

Seems true, given our government leaders closed the churches a couple years ago, by declaring them “non-essential” … while coercing and forcing “vaccines” on the populace.

One must wonder if the public will ever start listening to us, well researched, long time pharmaceutical ‘canaries in the coal mine’ … who’ve been warning about the criminality of big Pharma for decades?

Report comment

009 – a License to Pill

The Police were doing raids on Church services to check vaccination status and mask wearing here. All forgotten about now, though a policeman who tried to take his employer to court for discriminating against him for not being vaccinated failed…… setting such a legal precedent would mean the inability of the State to use force if the situation arises again. That is, with no real evidence or proof of efficacy, the drug companies want us all ‘jabbed’ (at a cost to the taxpayer yet to be determined).

“One must wonder if the public will ever start listening to us, well researched, long time pharmaceutical ‘canaries in the coal mine’ … who’ve been warning about the criminality of big Pharma for decades?”

I seem to have come across one of those Priest/Psychiatrist combos who have been doing a little institutional silencing Someone Else. Any advice you would give in having such a person appropriately ‘referred’ for his ‘character flaws’, and snow jobs for others who are providing protections to ensure he is kept well positioned to deal with any ‘complaints’?

Report comment

Although I don’t think the vaccine should be forced on people, the scientific evidence is quite conclusive that they can help people against covid, although not without problems that can’t be ignored. My statement about the church was exactly that, which is what big business is doing now. Promising someone an entrance to Heaven is no different than big business promises of “happiness.” The government also still does not require churches to pay income tax, so it’s hardly that they have been “shut down” the past two years.

There’s a vast difference between how psychiatric drugs have no scientific basis as agents that treat a chemical imbalance and how the covid vaccines work. Not that I am trying to force the vaccines on anyone, but we are talking about science, not about a gripe against anything and everything the pharm industry puts out.

Report comment

I think the vaccine was a missed opportunity for the FDA to educate healthcare professionals about the role of the immune system in depression. I believe most depressive episodes are triggered by the immune system responding to threats, be it psychological or physical. Many of the most effective therapeutic interventions involve triggering minor immune responses to controlled threats in order prevent more significant illness from uncontrolled threats. This is why maintaining a healthy immune system is more effective at treating and preventing depression than medication that often ends up weakening the immune system.

Report comment

This post is NOT about vaccines, it’s about anti-depressants! And there is a science behind vaccines that’s highly lacking regarding anti-depressants.

I think that vaccines have caused a lot of autism, which is not acknowledged. I think that the autism also comes from the way that one company wouldn’t supply its vaccine unless packaged with other vaccines, thus forcing anyone wanting that vaccine to get a dangerous triple does of vaccines with the MMR vaccine, that THAT caused a lot of injuries, I think that giving a child right after birth vaccines, when they don’t even have an immune system to process it, all done to get the parents to think it should be done regularly, I think that that’s ridiculous, I also think people should be allowed to not get a vaccine, if they don’t want to. I also think that when vaccines cause injuries that the companies shouldn’t be held irresponsible, the state instead paying for the costs of the damages.

But all of that doesn’t mean that vaccines don’t help some people. Neither does it mean that the covid vaccines haven’t helped anyone and that they have no scientific basis. I have had both jabs, and a booster, then got covid itself the first week of July, but only had moderate to mild symptoms. I’m not going to disqualify the vaccine from having helped or not. But then there are alternative methods, also breathing exercises, and Thieves oil as an anti-bacterial along with Artemisia extract, and simply staying at home and resting rather than getting alarmed. There is all sorts of alternative help that’s not really shared, simply changing the American diet would do wonders. People are STILL dying more of preventable diseases regarding their unhealthy diet than from covid. That the “government” doesn’t really address that with the same amount of attention is highly corrupt.

If there had been proper quarantines in the beginning the disease might have never spread, since it needs human hosts. No one who is sick she still be forced to work. There’s also evidence you can’t just push to the side that if they weren’t experimenting with biological weapons we wouldn’t have this problem (the US biological weapons dept. went to Wuhan because the US senate didn’t give them enough money to do it in the US, the covid virus comes from a bat that isn’t even indigenous to the Wuhan area, they never found the virus in any animal remains from the market, it only was in water, so could have come from a human, the dna of it shows signs of genetic splicing etc.). Regardless of all of that they shouldn’t be doing such experiments to begin with whether covid was genetically manipulated or not, as little as that being able to blow up all human life at least 20 times with nuclear weapons makes ANYONE ANYWHERE safe. Neither is being able to destroy the pharm industry by being able to blow up all human life 20 times with nuclear weapons the way to make change.

I don’t think people should be forced on the vaccine, in fact I don’t think that Djokovic should have been barred from the US open for not having been vaccinated. He had covid in the beginning, but it was asymptomatic. But this doesn’t mean that there’s no science behind it, and that people who want to be vaccinated are all misinformed.

The scientific technology for the Spizer vaccine is actually something that was already known, and could prove very useful for other diseases, but that technology wasn’t acknowledged, because that’s how the system works regarding stuff that’s new rather than in the market. So, that might even prove to be a plus.

But this post of Whitaker is NOT about covid, or vaccines or masks, and to take up the pitch forks and start demonizing everything about the pharm industry and/or therapists is not helpful, it only gives the extremists on the other side something to point their fingers at. I REALLY wish it would stop, because it becomes highly insensitive to what would help make change. It also shows EXTREME insensitivity to people that simply need a healing environment and NOT one full of distressing demands that they get involved in conflict.

I don’t even know what to say about all of this because I work with a healer, a lady who was tested in Japan and by simply sending energy from the right side of her brain, she got in a hospital with thermal imagery testing, a cancerous tumor to disappear within 10 minutes. Which she did because she found she might be able to help people but DID NOT want to hurt these very vulnerable people looking for help. Since she has helped a whole list of people, and children, and someone who had friends that work with her, who was in the hospital dying from covid who wasn’t suspected to survive was helped by her when his friends asked her to help him, and his health turned around as soon as she helped, and he thanked her. She’s also helped quite a few others. I’ve also had healing that wasn’t supposed to happen, because I wanted to experience that. That also goes along with what would otherwise only be seen as non-reality base “schizophrenic” thinking, because of the extra insight that might come would such thoughts be allowed to have meaning and be processed. Thoughts that happen by themselves. But then again she is NOT from a formal religious setting, and has no need for that. She also has had the covid jabs, but she doesn’t say she can decide for other people, and many were asking her regarding this.

This fanaticism on all sides becomes highly distracting, and now I’ve spent all of this – WAY TOO MUCH – time, and have written something that really is consequently quite off topic. And I’m not going to look to see whether there are any more reactionary responses keeping the post warped off topic with extremism regarding the pharm industry or whether the government sees religion as essential enough or not……|

People should be able to express themselves without having to have all sorts of predatory attempts trying to get them involved in extremism, whether it’s “Jesus,” another “religion,” the Pharm industry, Scientology, the anti-Pharm movement or anyone else trying to indoctrinate people rather than allowing them to think for themselves, to be able to follow their own thoughts, to simply be able to express themselves and feel safe to do that WITHOUT some attempt to make them feel guilty that they don’t see fill-in-the-blank as the enemy. That’s NOT how healing works or happens.

Report comment

Prior to the introduction of SSRI s in 1980 (plus) there was NO Depression. People took it for granted that they might be happy or unhappy, but identifying with Depression showed a person up as a loser.

These days if the “anti depressants” don’t work and the person complains – they might get a shocking (whether they want it or not).

Bob, as regards Disability Benefit – the UK claimants are probably GENUINELY Disabled as a result of exposure to the “AntiDepressants” – I very nearly ended up like this myself.

Report comment

Maybe RCT’s should now be called the fool’s gold standard –

Report comment

Good Point, Birdsong.

Report comment

Psychiatry’s DSM diagnoses medicalize normal reactions to life’s difficulties. And by medicalizing, psychiatry offers drugs that blot out the spiritual lessons and growth that could otherwise take place. And since most psychiatrists have swallowed mainstream psychiatry’s “scientific” delusions of their drugs’ efficacy, they’ve allowed themselves to be lulled into misinterpreting the “results” from their bought-and-paid-for “randomized clinical” drug trials.

Report comment

exactly the same sort of delusion persists in the psychotherapy industry.

Report comment

Thank you for this article. Beautifully done.

Report comment

This is a work of soaring, heroic scholarship, critical thinking and investigative journalism that could only be written by someone far outside the guild; really, kind of miraculous. Congratulations and thank you, sir. This needs to be circulated to the widest possible audience.

Report comment

RCTs do not prove anything (search for an article titled “Twenty-nine legal ways to distort the results of a randomized controlled trial”).

Report comment

Bob, thank you for this excellent, timely, and important piece. This is a complicated topic, and it can only be understood and addressed by appreciating that complexity. At the heart of this issue are fundamental questions about the nature of science itself and how the scientific enterprise can be hijacked by bad actors with agendas that are contrary to science’s goal of finding the truth for the betterment of society. We cannot properly understand the story of “antidepressants” without addressing these fundamental scientific issues. And for better or worse, these issues are complex and take a great deal of time to understand and process. Society reflexively trusts science, scientists, medicine, and doctors. The “antidepressant” story is a cautionary tale about misplaced trust in societal institutions gone rogue.

What we have with the “science” surrounding “antidepressants” is “fruit of the poisoned tree.” There are bushels of fruit, but the tree is rotten to its core, which makes the fruit superficially alluring but poisonous upon close inspection.

Report comment

It worries me that you just told thousands who might be feeling hopeless that the drugs they’re taking don’t work and are instead causing harm but didn’t tell them how, which you would know if you had bother to read the 2 emails I sent you.

Report comment

I don’t hear anyone saying the drugs don’t work. I hear someone saying that the data saying they DO work is biased. We already know that they work for less than half of the population at clinically significant levels – the most objective evidence says 30%. Don’t you think it’s fair to the other 70% to let them know they may not see the purported benefits? Do you think it wrong to let people know the actual adverse effect, including withdrawal, oops, I mean DISCONTINUATION effects, that plague many if not the majority of users? Do you deny that these drugs CAN cause harm to a significant subset of the population, based on the scientific data we now have available?

Report comment

I lost my son to suicide a few days after his dose of Zoloft was increased so I do get it.

What I told Robert in my email was that there is a high rate of MTHFR mutations in people who have depression and depending oil the type and amount, they can cause vitamin deficiencies that can affect methylation….and anti depressants and antipsychotics can cause the same deficiencies. As a matter of fact, I visited one of the groups complaining about withdrawal symptoms and they are exactly the same as the symptoms caused by MTHFR mutations.

In other words, if they had mild vitamin,in deficiencies because of MTHFR mutations, adding antidepressants made them worse. Then you stop taking them and the symptoms remain. They can be treated.

I hope that explains my post.

Report comment

That DOES make a lot of sense. My only caution is that “depression” is not caused by any one thing. But testing for THIS particular thing could save a LOT of trouble and suffering for a certain identifiable subset of the population!

Report comment

Kind of like screening for an alcohol gene before prescribing Paxil. Not than anyone should be prescribed paxil, but it would prevent a large chunk of population from harm.

Report comment

Quite so.

Report comment

Look, this is from the NIH….. Under nutrients affected by SSRIs it lists Folate, Vit D and calcium and they list risk factors which include “MTHFR variants”.

Interestingly, every time I posted about MTHFR at the suicide survivors support group, my posts got deleted and when I mentioned that 3 of their board members have ties to the suicide prevention orgs I was banned for being “disrespectful and argumentative”.

Report comment

Yeah, you don’t want to start upsetting people by speaking the truth!!! Very rude of you! /s

Report comment