I can’t even begin to count the number of times I’ve heard “Research has found that about 90% of individuals who die by suicide experience mental illness.” This particular sentence is courtesy of our good friends at the National Alliance on Mental Illness, although it’s repeated many places elsewhere (both live and in print), and sometimes in even more inspired ways. For example, the ‘Man Therapy’ website has this to say (emphasis added):

“There’s nothing inherently wrong with the personality or character of a person who dies by suicide. However, 90% of the time, there is an underlying sickness in the brain. And, like any organ, such as the heart, liver or kidneys, when the brain gets sick too often, it can lead to some life-threatening consequences.”

If you haven’t checked out the ‘Man Therapy’ website, by the way, it’s worth a look… at least if you care to experience a combination of horror, befuddlement, and ‘can’t-look-awayness’ all at once. A stereotypically ‘manly’ fictionalized therapist, Rich Mahogany, will lead you down a path of strange ideas and misinformation that follow no particular uniform code. For instance, I still find myself bewildered by the answer to the question, “Am I going to be seeing a therapist or need medication for the rest of my life?” This question (to be found in the ‘Man FAQs section’) offers the following response:

“No, you probably won’t. Depending on the severity of your issue, therapy and medication often is prescribed for 16 to 24 weeks.”

Wait. What!? While I appreciate the message that medication isn’t forever, I’m mystified by the message that an average expectation would be 16 to 24 weeks, especially given the site’s simultaneous claim that depression is a ‘sickness in the brain.’ Is there anyone reading this who’s only been prescribed a so-called antidepressant for 16 to 24 weeks and then stopped taking it because your psychiatrist felt it ‘did the job’ and sent you on your way? All I can fathom is that this is some sort of trick… A bait and switch, if you will. In this nation where ‘short term’ often refers to years (at least where psychiatric drugs are concerned), perhaps it’s just a ‘we’re telling you this so you’ll go down the road of getting started, and THEN we’ll tell you it may actually be for a lifetime” kind of game. But I digress.

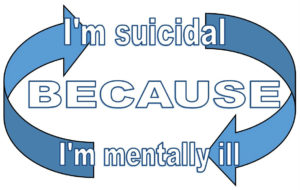

So, yes, that 90% figure is offered up time and time again. But, what on earth does that figure even mean? In a world where one can earn a psychiatric diagnosis largely because they acknowledge suicidal thoughts or tendencies, this may just be the greatest tautological trap of all time. In other words, what does it really mean to say one is suicidal because they’re ‘mentally ill’, if the proof of such supposed malaise is largely that they’re suicidal in the first place?

suicidal thoughts or tendencies, this may just be the greatest tautological trap of all time. In other words, what does it really mean to say one is suicidal because they’re ‘mentally ill’, if the proof of such supposed malaise is largely that they’re suicidal in the first place?

Here’s what I believe it means in far too many instances: It’s an ‘out.’ It’s an easy answer that absolves us all of blame. If someone has a ‘sickness in the brain,’ then it doesn’t have to be our fault or even necessarily our concern. We can ignore homelessness, racism, transphobia, poverty, homophobia, misogyny, joblessness, lack of good healthcare, the impact of war and violence, and so many other societal ills with impunity because the reason that person killed themselves is because they were ‘mentally ill.’ Nothing wrong with us! At worst, maybe we just failed to force a good, old fashioned hospital stay on them when it was most needed (before releasing them out into the same chaos from whence they came).

Conveniently, it’s also easy enough to tear down anyone who should say otherwise. After all, not all people who are subject to the incessant abuse and traumas that can come with being trans* die by their own hand! Not every woman feels broken down by constant objectification. Not all people who are homeless try to kill themselves, right? And, in fact, it’s true. Some people (for example) live on the streets for many years and still feel deeply invested in continuing to breathe. However, it’s a strange, cruel world we live in if it then makes sense to anyone to say, “If you can’t handle the terror, pain and desperation that often comes with being homeless like that guy over there, then boy do you have a problem! I call mental illness!” We’re allowed to have different tolerances, and sensitivities. Inevitably, each of us will learn to survive hell in our own ways and tolerate it for different amounts of time. That doesn’t make any of us sick.

This absurdity represents an outrageous failure within all of our systems, and a relentless level of denial (perhaps due to our own sense of hopelessness and helplessness about our ability to change some of those things). And until we come to terms with at least some fraction of that fact, we will continue to diagnose people (sometimes posthumously) to keep ourselves rolling forward while committing a sort of societal suicide along the way.

Unfortunately, and as with so many other similar situations, this ridiculous diversion prevents us from ever asking any of the right questions. If we strip away all the things we know not to be true – the chemical imbalance lies and our own brains in the role of supreme super villain – then maybe we can start to see. And, if we stop being afraid to take some responsibility – not for each other, but for our role in creating or perpetuating some of the conditions that lead to such despair – then maybe we can find our way to change.

I can’t pretend to know why particular people choose to kill themselves. I’m still learning and exploring more and more about why this is an urge I sometimes face, and I’m certainly not going to claim one uniform reason (or even a few) across the board. But here’s what I do know:

There are at least two key questions in supporting people who are struggling in this way. Neither of them include ‘do you have a plan?’, nor do they ever require you to assess and identify an objective reason as to why death might be the current topic at hand. (These are little more than the flailing efforts of someone who knows not how to approach another human, but rather simply seeks to yell, ‘Stop!’ while they plug their ears.) Instead, they are:

When you say you want to kill yourself, what do you mean by that?

And

What is leading you to the point of wanting to die?

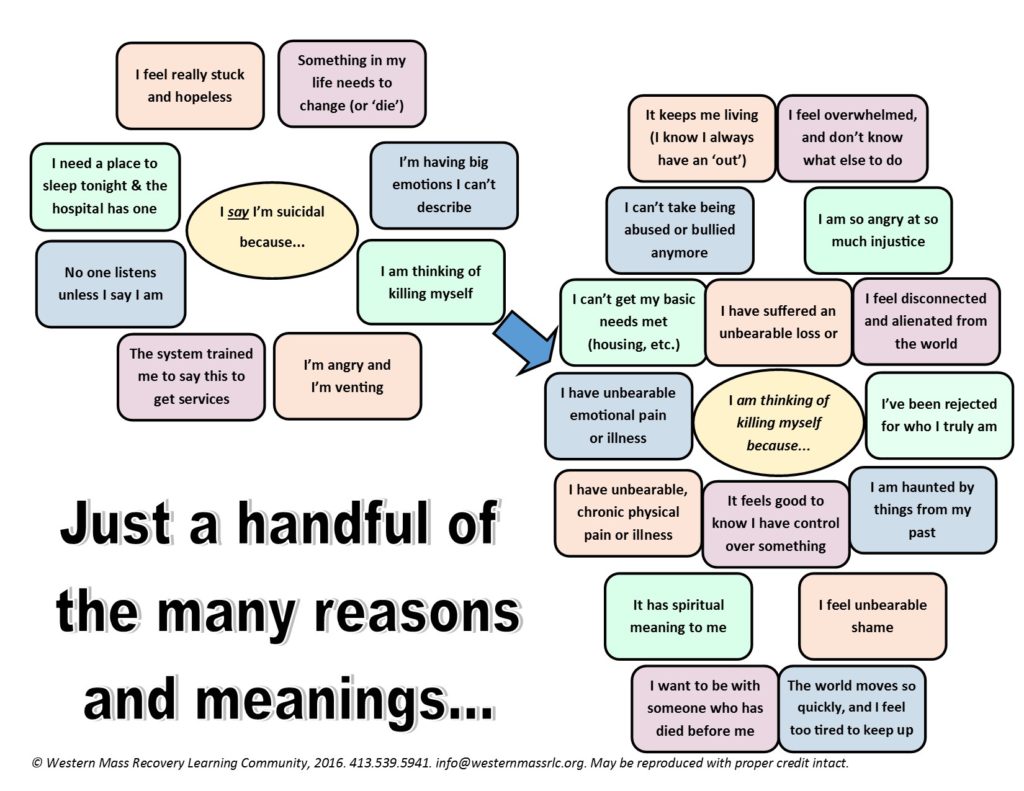

Now, I’m not suggesting that those two questions be consistently asked, and certainly not word for word. They are not ‘the‘ answer anymore than anything else. What I’m getting at is that some people talk about wanting to kill themselves when they really mean something else entirely. Some people have simply been trained to use ‘I am suicidal’ as a code word for, “I want to go to the hospital,” or to represent need or want for some other service. Others may mean that they want some particular thing in their life to stop (or ‘die’), and they’re at a loss as to how to make that happen without dying themselves. And, skipping over that layer of exploration can actually play a part in pushing someone in a direction they hadn’t really intended to go in at all.

Meanwhile, for people who do actually mean that they are literally contemplating death by their own hand, failure to even try to understand why (especially out of the arrogance of assumption that one already knows) can truly mean the difference between life and death. This is decidedly not because knowledge means the power to ‘fix’. That will often still elude us. But it is a necessary step toward really being able to sit with someone else in their pain, and that level of being ‘seen’ has more healing potential (for society and for one another) than most anything else we typically have at our disposal.

The real truth is that people are going to die. Sometimes they will die because they kill themselves. There’s no way we will ever be able to stop that, and it seems clear that we do far more harm than good by acting as if we have (or should have) such power over one another. By constantly focusing on the superficial stopping of the act itself (often by any means necessary), we rob ourselves of the time and relationship needed to build understanding. It is in that relationship that we find our real strength.

The graphic below is not intended to offer any answers, but is simply meant as a visual reminder of the complexity of our words and experiences and the value of exploring them and learning from one another. (Click here for a printable version.)

Coming soon: Suicidal Tendencies, Part 2: But, when do we call the cops? No, really…

“Consider suicide, I do that these days

I thought about what I could do with my grave

Google search how to make a grenade

Toggle my aim, scribble some names

Took a few breaths, blew out some steam

AND SENT THAT SHIT OUT AND I BLEW UP THE GAME.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ebySFDUPbRk

Yeah, good chart, staying alive has felt like participating in my own objectification for as long as I can remember, so. Would be nice to get somewhere else but I’m not banking on it.

Report comment

Thanks, Lily. I appreciate your sharing (both the lyrics/link and a bit of your own experience). I find myself stuck in the ‘world is moving too fast, and I’m too tired to keep up’ and the ‘what’s the point of it all anyway’ places all too often.

Thank you for reading and commenting.

-Sera

Report comment

To start, it’s a truism, even from their perspective: “he committed suicide because he was mentally ill.” If you define suicidal ideations and actions as part and parcel of mental illness, then 100% of people who commit suicide are mentally ill. It’s a disingenuous use of statistics at best and my graduate degree is in financial statistics, so I have some authority on the subject.

But to your broader point, I attempted suicide in 2012 because I was on a cocktail of eight different psychiatric medications that left me overweight, stupid and useless, frankly. I was burden to everyone around me. I also had two torn meniscus joints and no health insurance. As an athletic person, I was cut off from the one outlet from anxiety/depression that I had always depended on.

But what pushed me over the edge?

A psychiatrist put me on amphetamines – though he knew about my severe issues with anxiety – and its was like throwing gasoline on a campfire. I lost impulse control and tried to swallow a bottle of Lithium – something I never, ever would have done otherwise. Fortunately, even my liver emerged unscathed, but I came very close to death that evening.

In 2013, I acquired health insurance through Obamacare – had two knees surgeries – and started to hit the gym again. That was maybe 20 months ago and I stopped counting at 50 lost pounds – probably I have lost more like 60 by now. It’s one pillar of a holistic regimen that also includes nutrition and meditation. I average a 10-11 mile run every other day on average and I am 49 years-old.

So as I said I agree that its disingenuous to blame “mental illness” as if someone’s mental condition remains unaffected by social ills and personal circumstances (economic collapse, homelessness, discrimination, illicit substance abuse).

If there is such a thing as a mental illness, it is not a virus that exists largely independent of someone’s wealth or social status. Both a rich man and a poor man can get the flu, right? But the correlation between poverty/discrimination and “mental illness” (and I imagine suicide) is undeniable. In other words, it has a context beyond the physical body and its immune system, more so than a physical illness.

Report comment

Thanks, Robert. You say a lot of important things here one of which (in particular) I didn’t address in the blog which is that sometimes people are moved toward suicide specifically because of psychiatric drugs… I’m hoping to focus a whole piece on that issue as a part of this series, but I’m really glad you brought it up here!

Thank you for sharing a part of your story. It illustrates so very much of what’s terribly wrong with this system in a really concise and clear way. I really appreciate it. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks, and its a great subject. I love (not) how the psychiatric establishment and its partners abuse statistics to blame the patient.

It makes no more sense to me than the “insanity defense,” though I have much greater sympathy for a suicide attempt. “I murdered him because I am insane and therefore not responsible for my actions.”

In a courtroom, that’s a legitimate legal defense in some murder cases. But again its a truism to me. From my point of view, it takes a “dangerously insane” person to commit murder. The insane part is inherent to the act of murder – it does not make you less culpable or less responsible for your actions.

If I am a compulsive alcoholic – and I just can’t help but drink too much – and I kill a family of four in a traffic accident when I am out drinking and driving, I am still guilty of negligent homicide, despite my illness (provided you buy into the disease model for alcoholism – but let’s put that aside for argument’s sake).

With that said, its very important to note that people with mental-health diagnoses are far more likely to become the victims of violent crimes than perpetrators.

When I researched this subject, the only conclusions I could find stated that even paranoid schizophrenics were no more likely to hurt other people “unless they were on street drugs.” That last clause bugged me because anyone on certain street drugs – especially cocaine, crack and crystal meth – is far more likely to commit violent crimes, regardless of mental-health diagnosis.

Yet, every time there is a mass murder the media labels the perpetrator a “paranoid schizophrenic” when there is zero (none whatsoever) correlation between schizophrenia and criminal violence (period).

Report comment

Yes, in fact I think most research will ultimately acknowledge that people with psych diagnoses are more dangerous under the influence of certain drugs/alcohol…. but no moreso than anyone else.

The insanity defense speaks point you make also speaks to a much broader issue of people in the system not being held responsible for anything negative they do because their ‘illness’ made them do it… and then the providers aren’t responsible for any of their violence or wrongdoing either because, well… the person’s illness made them do that, too! Oy. What a mess.

Sera

Report comment

By “providers” do you mean psychiatrists, Sera? They should be held legally responsible for mass shootings if the shooter is being “treated” by them IMHO.

We know the mother smothered her toddler because she was bipolar.

How do you know she was bipolar?

Because only a person with bipolar would smother a toddler.

Brilliant deduction. And a perfect example of the Circular Reasoning Fallacy.

Report comment

“Is there anyone reading this who’s only been prescribed a so-called antidepressant for 16 to 24 weeks and then stopped taking it because your psychiatrist felt it ‘did the job’ and sent you on your way?” LOL, psychiatrists almost never intentionally take people off of drugs. I did find embarrassing them, by pointing out the stupidity of their logic to other doctors, did work in getting weaned from the drugs though.

As to the psychiatric industry’s “I’m suicidal, because I’m mentally ill,” and “I’m mentally ill, because I’m suicidal” theology. I believe this is known as circular reasoning. “Circular reasoning (Latin: circulus in probando, “circle in proving”; also known as circular logic) is a logical fallacy in which the reasoner begins with what they are trying to end with. The components of a circular argument are often logically valid because if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true.”

I will also say I found the “mental health” industry to be absolutely obsessed with suicide. I was asked over and over again if I felt suicidal or had ever contemplated suicide. I wasn’t suicidal, which was “of great concern” to my easily recognized iatrogenesis and child abuse covering up psychologist and psychiatrist. So they decided to defame me, and try to murder me via multiple anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings.

But I will say, drugging every human who has ever considered suicide, especially with the SSRIs that are known to create suicidal tendencies, is a stupid idea. Since contemplating suicide is quite common.

http://www.nbcnews.com/id/32883786/ns/health-mental_health/t/million-americans-consider-suicide-each-year/#.VqULMrQ-C9Y

Report comment

Thanks, Someone Else. Yes, obsessed indeed, I agree with you… While I believe people do care on a human level in many instances, I think so much of this comes out of liability… If you die slowly on our psych drug prescriptions, we can avoid blame… But if you die quickly on our watch, it’s all our fault. That thinking drives far too many things…

-Sera

Report comment

“If you die slowly on our psych drug prescriptions, we can avoid blame.” This is the problem, the psychiatrists need to be held legally liable for all the deaths and harm they are causing. But they are not being held responsible by our current government, resulting in a new psychiatric holocaust.

http://www.naturalnews.com/049860_psych_drugs_medical_holocaust_Big_Pharma.html

https://www.rt.com/uk/258133-antidepressants-unnecessary-for-many/

http://www.rehabs.com/pro-talk-articles/psychiatric-medications-kill-more-americans-than-heroin/

One must wonder how long today’s medical holocaust will continue.

Report comment

Its called the pharmacaust.

Report comment

Oh my goodness! That’s a very good way of putting it!

Do I have your permission to use this phrase because it’s pretty amazing.

Report comment

I do wonder how much longer the pharmacaust will continue.

All the evidence of more harm than good is out, its easy to find with simple Google searches at this point.

But I have been at this long enough to know psychiatry is not about helping people its about controlling people controlling unwanted behavior and thought so the fact that the drugging is harming people long term is not that much of an issue to them.

Here is a video that comes up when the word pharmacaust is searched.

The Pharmacaust: The Destruction of the “Mentally Ill”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vkRt46QMms

Report comment

The psychiatric industry has actually proven to all the “professions” that it has the legal authority, given by our government, to unjustly defame, discredit, torture, poison, and create ‘psychosis” in any person, for any unethical reason.

And the ability of the psychiatric industry to do this, with the blessings of our current government, is the basis of injustice.

This “right” of the psychiatric industry needs to be taken away.

Report comment

Very true, someone else. I wish it were a clearer path as to how to hold people responsible.

Sera

Report comment

One of the best predictors of suicidal behavior is recent release from inpatient psychiatric treatment.

Why is that ??

Having experienced inpatient psychiatric treatment I would think that what happens is the person really expects help. That word help is used over and over to describe inpatient psychiatric treatment. Then the person finds out they are not getting help they are getting strip searched , NO SMOKING, locked up and dehumanized … Coerced drugging , forced drugging… The only “help” is talking to the other patients sometimes.

I can’t speak to the dead but my guess is the inpatient abuse nightmare sends them over the edge. This is what they call “help” , this abusive nightmare ?

Eff this world if that’s what they call help its hopeless … Again I can’t speak to the dead but my guess is that when you promise people help and all they get is the abusive inpatient nightmare what else is their to expect ?

It is important for clinicians to know that an especially dangerous characteristic, one that exponentially increases the chances of suicide, is recent discharge from a psychiatric hospital.

And I think the worst thing to say to a person that was abused inpatient or just hated it is “I am sorry that happened to you”.

“I am sorry that happened to you” WTF does that mean ? That means its YOUR fault inpatient was abusive but you “needed” it.

It is important for clinicians to know NOT to say “I am sorry that happened to you” and say “that SHOULD NOT have happened to you” instead.

Suicide, the way inpatient psychiatry treats people is the reason for so much of it.

Report comment

The cat: While I had fleeting suicidal thoughts prior to my civil commitment, I can state unequivicatly that the only time that I constructed a plan was after my back to back experience with two state hospitals.

Report comment

“And I think the worst thing to say to a person that was abused inpatient or just hated it is ‘I am sorry that happened to you.'”

No, actually the worst thing is to completely deny the inappropriate maltreatment, which my follow up psychiatrist did, and continue to force medicate the person on drugs that make the person “psychotic.” My follow up psychiatrist claimed I had “odd delusions” of prior maltreatment by doctors, according to his medical records.

Now he’s morally responsible for all the deaths subsequently cause by the now FBI arrested doctor I was medically unnecessarily shipped to, and “snowed” by, V R Kuchipudi.

http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndil/legacy/2015/06/11/pr0416_01a.pdf

The psychiatrists really need to get out of the business of denying, covering up, and rationalizing the crimes of the unethical doctors, because this results in more medical murders.

Report comment

The cat, yes, that’s a really important finding… that suicide risk is at one of its highest points immediately after being ‘helped’ in a hospital. It speaks to many interesting subpoints like does ‘safety’ only matter as long as you think you’re liable/responsible? Does ‘safety’ only mean preventing someone from taking lethal action in a given moment? At what point is ‘safety’ ever defined by the person deemed ‘unsafe’? And you’re certainly right that there’s a complete failure to respond with any seriousness to abuses that do happen… laws are violated on a daily basis in the name of ‘safety’ and with impunity with the Same justification… it certainly is maddening.

Sera

Report comment

Clearly the only solution is to never release anyone from a psychiatric institution.

Report comment

Not to mention release from the hospital usually occurs right in that 1-3 week range when the most suicides from new antidepressant or antipsychotic prescriptions are most likely to occur.

— Steve

Report comment

Love your heading, the circularity of the reasoning there is so apparent. Failure at suicide in today’s world means guaranteed “mental health” treatment. I think suicide can be rational, that is, non-madness, in fact, but I wouldn’t encourage it. In Europe there are places where a person, even a person suffering from a “mental illness” label, can get physician assistance in the matter. No so-called “mental illness”, in itself, is lethal. None. Physician assisted suicide, in such cases, is homicide, and it is my feeling that it should be prosecuted as such. Suicide is very do it yourself as far as I’m concerned. If one needs assistance in the matter, one doesn’t need to kill oneself.

Report comment

Hi Frank, yes, the circularity seems so obvious and yet people keep throwing it around like it’s some big meaningful fact. Oy. The conversation you bring up about assisted suicide is an interesting one and one I’m planning on getting at to a certain extent in a later blog… it’s definitely complicated by a number of factors… do you feel the same even in situations where someone is dying or deteriorating due to a physical illness?

Report comment

No, terminal, and often painful, physical disease might require desperate measures. However, I’ve seen where a person diagnosed bi-polar has gone to Switzerland to get approved for doctor assisted “euthanasia”. Bi-polar disorder isn’t terminal, and I question whether any of what is referred to as bi-polar disorder isn’t primarily a matter of prescription drug effects and dependence. Seeking a doctor’s assistance in relieving one’s “mental” hell through physical termination, it isn’t necessary, and if it isn’t necessary, it shouldn’t be done. In such cases, doctor assisted suicide is a euphemism for what is, in point of fact, homicide, murder. If a person wants to kill him or herself because of psychological turmoil and upheaval, they should not be aided and abetted by a medical doctor in doing so. There are other ways to resolve psychological turmoil that are not so extreme as that of completely and permanently extinguishing the physical organism.

Report comment

I agree, but we probably have to acknowledge a general right to end one’s physical existence for any reason (though maybe not a right to do it in the face of a non-consenting person). However I also believe that if a doctor participates in an assisted suicide based on his validating the patient’s belief in a nonexistent disease he should be fully prosecuted.

Report comment

So this is how the University of Washington’s Social Work Graduate Program interpreted the original results by SAMSHA – and its not as simplistic as the NAMI quote and makes a little more sense.

“The great majority of people who experience a mental illness do not die by suicide. However, of those who die from suicide, more than 90 percent have a diagnosable mental disorder. People who die by suicide are frequently experiencing undiagnosed, undertreated, or untreated depression.”

I was a nonprofit fundraiser and grant-writer for 25 years, so I am accustomed to fundraising and advocacy organizations reducing statistics into alarming sound bytes for the purposes of promoting their agendas and raising money, whether for good or evil purposes. Its very rare that these organizations attempt to qualify these statements within a broader context, because the average donor does not respond to intellectual appeals – he responds to emotional appeals. I tried to get to SAMSHA website to look at the original source, but it would not load for some reason.

http://mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/suicideprevention/suicidefacts.asp

The NAMI quote is not a lie per se but it is dangerously reductionist. It makes it sound like all people with mental health diagnoses are prone to suicide, when the original study apparently concludes that the opposite is true. In fact, the original findings conclude those most prone to suicide have “undiagnosed and untreated” mental illnesses. Welcome to the world of marketing, political advocacy and fundraising, folks!

Still, its dangerous to promote the idea that all people with mental-health diagnoses are prone to commit suicide, because it filters into mainstream reproach (social isolation) and the judicial system, where we become by definition second-class citizens because we are inherently incapable of making decisions in our own best interests. I believe the clinical word is ego-dystonic – e.g. as a gay person I was once once considered ego-dystonic because being gay had an adverse impact on my aptitude for personal happiness via social acceptance.

I do need to qualify the statistical correlation between suicide and poverty. Again, this is first blush research but it comes from a short article in The Huntington Post. Apparently, suicide rates are highest at both extremes: the extremely wealthy commit suicide at more or less the same rates as the extremely poor. In particular, the major variable is your socioeconomic status relative to those around you. If you make significantly less than your neighbors, you are more prone to suicide than people who live among their socioeconomic peers. Interesting….

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/09/suicide-rate-rich-neighborhoods_n_2102777.html

In a nutshell, the real troubling correlation is the suicide rates among people with undiagnosed and untreated mental illness, according to the study. But that does not comport with personal experience.

The further I get away from psychiatry and its medications, the better I feel – and the more likely I am to make healthier choices. Its a popular political opinion these days that the answer to our social problems (like gun violence) is more funding for mental health programs, instead of stronger background checks and other reasonable impositions. In my experience – and this is only my experience – in the world of mental health and psychiatry in particular – the cure has always been worse than the disease. I would not expect funding for mental health programs (psychiatry in particular) to reduce gun violence, suicide, etc…

P.S. Not to parse words or get off topic. Circular reasoning is the use of something to justify its own existence. To paraphrase British philosopher David Hume in his critique of science: “You cannot use the empirical method to justify the empirical method.” – that is circular logic or reasoning.

I chose the word “truism,” which is a self-evident or so obviously true statement that does not bear mentioning, like “He committed suicide because he was mentally ill.” Regardless, we are more or less on the same page, and I am just a word nerd.

Report comment

Robert, I am not sure the quote you offer is all that much better. I still find it to be highly problematic because, well… what is ‘mental illness’?? If it is simply the existence of pronounced suffering, then that most people who kill themselves experience pronounced suffering is certainly true… however, the problem is thatg mental illness tends to much more specifically mean a medical condition in the brain…. and if the only proof of a medical condition in the brain is the act that people are saying is caused by that medical condition (or the feelings of distress leading up to it) then that seems the epitome of circular reasoning to me… and seems particularly problematic when one considers that there are about a zillion reasons why someone might contemplate intentional death that have nothing to do with disease in one’s brain….

Report comment

However, of those who die from suicide, more than 90 percent have a diagnosable mental disorder

What sorts of circumstances account for the remaining 10% of apparently “mentally healthy” suicides?

Report comment

Large sums of money that would be distributed in other directions if the person who committed suicide were deemed incapable of dealing with their own affairs. Know what they say…. where there’s a will….. there’s relatives lol

Report comment

Hi Sera,

A good article covering many familiar themes.

Another important cause of suicide is poor parenting. Rather than blaming parents, it should be acknowledged that abuse and neglect often gets repeated by parents who inadvertently mistreat their own children, just as they were poorly raised by their own parents (the grandparents). This inconvenient fact shows up in the ACE study and the many studies of John Read linking childhood abuse and neglect to “mental illnesses”, with those pseudo-diagnoses being correlative risk factors for suicide.

It is incredible to read such simplistic and meaningless denials as “schizophrenia cannot be blamed on parents” or “depression is not a character fault”, and a related one is “parents are never to blame for a child’s suicide.” Of course they shouldn’t be blamed, but parents often are a powerful contributing reason to why a child chooses to commit suicide, because unskilled parents do not adequately love their children, do not develop a secure relationship with the child, and fail to adequately prepare the child for adulthood. Therefore such parents are causal agents in predisposing the children to overwhelming anxiety and depression from which the child may choose to escape via suicide.

Acknowledging parents’ contributions to suicide risks could be a positive thing, because it could enable broader application of family-centered approaches including trauma-focused psychotherapy.

The primary drivers of mental hospital “treatment” in the United States includes fear of lawsuits, fear of people who are “out of control” (experiencing terror, rage, and difficult life situations for which there is not easy solution), and of course the need to profit via giving drugs that rarely help and often worsen the situation in the long-time. Mental hospital workers have little interest or ability/training in understanding the complex developmental causes, often including poverty, bullying, poor parenting, abuse, neglect, rage/terror, that lead to a person becoming suicidal. Their primary motivation is to not get sued, to avoid any real confrontation with difficult emotional problems that they are poorly trained to handle, and to keep the profit machine running.

Because of the perverse motivations of its staff, an American mental hospital is often the worst possible place to go if one is in crisis, and is a place that I always advise people not to visit unless absolutely necessary, just as I advise people not to visit psychiatrists whenever possible.

Report comment

Bpd, yes, early childhood trauma is an extremely important factor in so much suffering… but also as you note, it can be extremely hard to get at these conversations without people feeling blamed and defensive… in any case, thank you for reading and taking time to write such an in depth comment

Sera

Report comment

This is a well-written piece. When I was at the height, or should that be depth of my depression the 2 reasons I had for wanting to end my life were simple. One, to end my painful anguish; and Two, to stop being a burden upon my friends and family. I thought that they would be overjoyed if I was off their plate. But that is nonsense. That said, the depressed suicidal person is not rational, and therefore any attempt to explain their decision on a rational basis is bound to fail. I am still here because people did not give up on me. My recovery to where I am today – coping, not cured, – has taken years and not an arbitrary 16-20 something weeks. I look forward to reading Part II of your excellent article. Thank you for listening.

Report comment

Hi Redbox, Thank you for reading and commenting. I really appreciate that people are sharing here and on the Facebook end of things what their experience of suicide has been.

-Sera

Report comment

redbox

I would disagree. I think that people can be rational and yet kill themselves.

Report comment

BA: Has anyone else been following the unearthing of Heidi Cruz’s brush with the “danger to herself” tribulation. While no fan of the Cruz’s political outlook, it is a good day when anyone manages to right their situation without becoming ensnared into the mental health-big pharma industrial complex. It was Szasz’s contention that psychiatrists and lawyers (the two professions most directly involved in civil commitments) avoid at all cost from becoming the subject of that process.

Report comment

Chrisreed, Hmm. I hadn’t heard anything about Heidi Cruz. I’ll have to google that! Thank you for pointing me to it!

Sera

Report comment

You make me feel prosaic, just taking my vitamins and avoiding caffeine, alcohol and junk food. But I don’t feel suicidal, so what the hell.

Report comment

I sometimes feel suicidal because ever since I was a wee little thing I was made to feel useless and unwanted. Society has done nothing to abate those feelings. There is too much competition. It is just a fear of God that has kept me going. These days there are a number of suicidal people on a certain superhero cult group which, I feel, indicates that the ego is somewhat involved. These people make extraordinary efforts to make themselves present and useful in society but find that society is too cold, hateful, and more than ready to see them die. Like you said, you cannot mask the truth. But, like Lao Tsu said, ““If you are depressed you are living in the past. If you are anxious you are living in the future. If you are at peace you are living in the present.” We need to strike a balance between feeling needed/useful in the present and helping others around us. Everybody needs help so the demand is there.

Report comment

Hi lshane,

Thank you for your comment. I like the Lao Tsu quote, although I’m not 100% sure I agree with it. : ) That said, balance does indeed seem key… Particularly the balance between believing that our own basic needs are going to be met, and supporting others to find the same!

-Sera

Report comment

Hi lshane! I relate to this a lot! Curious about said superhero cult group… Definitely it’s depleting to try to engage with people in a society that treats us as disposable. Glad yr around.

Report comment

Hi Sera,

I like the way you describe the cringe inducing ‘man to man’ website – you’re very eloquent.

I’m also against mental illness promotion (through the back door). 150 years ago when children were employed in work houses they weren’t ‘mentally ill’ they were being exploited.

My main problem really was the medication, and once I stopped the strong medication I was no longer a suicide risk.

Report comment

Thanks, Fiachra. My problem (with thoughts of killing myself) has never been psych drugs (though they did bring on some other interesting effects that I’m glad to be long rid of!), but it’s been really interesting to see just how many commenters on here and on Mad in America’s Facebook page have noted that that was the issue for them, and so frustrating that so many would deny that. Thank you for taking the time to read and share!

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks for replying, Sera.

Report comment

I have felt suicidal many times, beginning at the age of 15, made several attempts, and happily I now have these feelings much less frequently. At one time in my life, I found myself in a situation with severe legal, moral and financial ramifications, and I felt that I could not tolerate the pain and the consequences of this situation. I could not find any help or any way out.. All other times the wish to die has come from loneliness, from being alone, being unable to connect with another person, unable to feel a connection, left out, isolated. As I get older, the intense need and desire to connect doesn’t really diminish, but I am better able to (1) see some of this loneliness as existential, as a result of my human condition, and (2) to be happier with more informal contacts, like being part of a group in which people get along and are kind to each other, being in a class with those who share interests, the conversations at the bus stop and so forth. Some of my struggle has had to do with depression, some with my skills at making connections, and some I cannot explain. I take offense at experts who “know” why people commit suicide. I think that they are projecting their own ideas, and that they never knew the individual people they are talking about, each of whom had a life of their own. I think there will always be people who take their lives, who make that choice, but I also think that we can make better efforts to help others figure out and find what they need.

Report comment

Celestevt, I relate greatly to how you describe the source of some of your emotional pain. I’ve never been good at making friends or feeling comfortable in social situations, and sometimes feel most alone when I find myself in groups and realize that everyone else seems at ease and connected and I’m… just not. I can also appreciate what you describe about it getting a little easier somehow as you age, not because it’s actually easier but because it’s a little clearer what it means… Thank you for sharing.

-Sera

Report comment

Hi Sera, this is too well written for me to take issue with anything even for the sake of argument. It’s good to see some articles of substance appearing, it’s been getting pretty abstract & academic around here lately.

What I keep thinking about is how your title reminds me of the ditty we used to sing on the “hospital” bus during occasional field trips:

(To the tune of Auld Lang Syne) “We’re here because we’re weird because we’re here because we’re weird…” Over & over & over. Ah, nostalgia.

Report comment

Hey Oldhead, Thanks for reading and commenting as always. 🙂 That song is indeed very ‘apt’ 😉

-Sera

Report comment

Where did these alleged psychiatrists who treated Mr. Pfaff come from? Do alien life forms disguise themselves as psychiatrists to spy on us? These guys’ medicating practices are behind those of an educated stoner. I’d prefer a long-term member of Schizophrenics Anonymous to treat me for a serious relapse to these guys.

Report comment

bcharris, Wow. That’s quite a statement, based on the little I know of Schizophrenics Anonymous! Thanks for chiming in 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

BeHarris, I recently read that psychiatrists may be coming from a planet circling the star Kepler 438b, which is 470 light years from Earth. According to the conspiracy theory, starting around 1500 AD, the aliens inhabiting this planet decided they wanted to embark on an intergalactic voyage of colonization. They identified Earth as their target. Traveling at close to light speed, they arrived on Earth in around 1970 AD. They disguised themselves as humans and quickly filled most of the senior psychiatrist and research-psychology positions at elite universities, shifting the psychiatric model from psychological to biological.

Using the pharmaceutical companies and politicians (many of whom are also body-snatched aliens), the alien doppelgangers proceeded to change government and medical policies so that America and all other countries would increasingly sedate their citizens with mind-numbing drugs. This would prepare Earth for the all-out alien invasion that will follow once around 90% of the global population is sedated with antipsychotics, benzos, and antidepressants. At this point, the plan is for most able-bodied humans to be repurposed as permanently drugged slaves of the alien overlords.

Recently intercepted communications from Kepler 438b indicated dissatisfaction with the fact that only around 20% of Americans are sedated so far, with demands for the process of zombification to accelerate and for the alien leader, one E. Fuller Torrey, to amplify the campaign of drugging preparing the way for the mothership’s arrival.

However, American presidential candidates have chosen to ignore this looming threat, because they consider Islamic terrorism, gun violence, abortion, and gay marriage to be greater threats than the coming alien invasion.

Report comment

LOL!!!

You have such a way with words and a very active imagination! This is great!

Report comment

I have a friend who is Schizophrenics Anonymous so I resent the comparison. Perhaps could you change your statement to something like: “I would rather be treated by Sarah Palin’s speech writer?”

Report comment

+1 🙂

Report comment

I’m reminded of the words of one Prof Patrick McGorry who was on a discussion panel about mental illness who said something like “no, suicide is not mental illness, but it’s also not a very mentally healthy way of thinking”. (sure we got it covered doc?)

Same guy who says psychiatric treatments have advanced significantly, for example fish oil. But we need laws to be able to snatch people from their beds in Fallujah style night raids and incarcerate them in order to get them the help they need. The fish oil.

It’s a handy rubber stamp down at the coroners when one reads the reports. Lots that doesn’t need to be examined if they had a broken brain.

Look forward to part 2 Sera.

Report comment

All very true, Boans… especially that rubber stamp part. I think I tried the fish oil thing once, but I couldn’t really afford to keep it up to see if it actually did anything worthwhile… Now I focus on keeping pills *out* of my body, rather than looking for the next great one to put in…even fish oil.

-Sera

Report comment

“But we need laws to be able to snatch people from their beds in Fallujah style night raids and incarcerate them in order to get them the help they need.” I very literally was dragged out of the comfort of my own bed in the middle of the night, by five giant paramedics, as the sixth paramedic told the other five that what they were doing was illegal, since I was neither a danger to myself nor anyone else, and I’d agreed to just go back to sleep.

Damn the laws, said the five paramedics, men need to incarcerate women for a sleep walking / talking issue. And, unfortunately, I wasn’t treated with fish oil. No, I was subjected to ten days of V R Kuchipudi’s medically unnecessary “snowings” with massive quantities of the psychiatric drugs. And I was only finally let out, after two and a half weeks, because my insurance company refused to pay to have me incarcerated for life, as was the hope of the “snowing” psychiatrist, Humaira Saiyed.

http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndil/legacy/2015/06/11/pr0416_01a.pdf

It took seven more years for Kuchipudi to finally be arrested for doing the same thing to lots of other patients. And Humaira was never arrested. Power corrupts, and absolutely power corrupts absolutely. The power to incarcerate and force treat people for profit needs to be taken away from the medical community.

Report comment

Laws? What was I thinking.

Our Chief Psychiatrist who has the duty of protecting consumers, carers and the community doesn’t even recognise the law. His grandiosity has resulted in his removing the flimsy protections that were there in the form of a burden of proof (suspect on reasonable grounds). Apparently he is quite prepared to accept that the grounds for incarceration and forced drugging can be met because tomato.

Rights and protections paid for in blood, removed with the stroke of a pen, and not even requiring the authority of our elected officials.

Those pesky laws getting in the way of ‘medicine’. Lets just misrepresent them and do what we want.

Disgraceful.

Report comment

Sera,

Many thanks for your sharp insight into this difficult subject. Just to add my own experience to the growing list: The only time I felt close to suicidal was on release from psych hospital over 20 years ago. It had been a brutal experience, and I vowed that whatever happened I was NEVER going back. With that came the frightening realisation that there was no safe place for me to turn if I reached crisis point again. Severe depression took hold, compounded by the fact that I never questioned the “illness like any other” line, and believed my very genes and brain were defective and diseased. I felt as though I was rotten at the core of my being.

It was only on discovering Anti-Psychiatry activists on the nascent Internet that I learnt there were other ways of viewing these experiences. This made me angry as I felt that I’d been cheated of a chance to learn and grow from the experience of madness. The anger helped lift the depression, and I was able to start rebuilding my life.

Report comment

Sinope,

Thank you! I love what you shared, because anger is so often pathologized, but it’s been lifesaving for me, too. And yes, I think it’s so common that people go through a sort of grieving process when they hear that there is something else, and could have been something else for them through some of their hardest times… Such important points. 🙂

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

I’d attend SA meetings myself, Madmom, except that there aren’t orthomolecular medical practitioners in my neck of the woods. I’d be a one man meeting.

Report comment

I used to work at a suicide hotline, and I learned to ask those very questions (or paraphrases of them) very early in any conversation with a person who stated suicidal intent or thoughts. There was almost always a very good reason for the person to feel suicidal, and I found that agreeing that the situation was depressing and felt hopeless led to lots of helpful conversations.

I also learned that almost no one in the mental health field had any training in suicide prevention beyond “ask if they have a plan and if so get them to the hospital.” Our volunteer phone counselors had more training than the average MA counselor in suicide intervention. Most counselors were completely at sea in dealing with any kind of a suicidal person.

Maybe my favorite call ever was from a woman who was depressed about her boyfriend breaking up with her. She went on at some length about how her mom had told her she’d easily find other men, and her girlfriend said he was a jerk and she’d be better off without him, but despite all this, she still felt depressed. They’d broken up four months ago after a four-year courtship. I told her, “Not only do I think it’s totally normal for you to feel depressed right now, if you weren’t at least a LITTLE depressed, I’d think there was something wrong with you.” She said, “Really?” I said, “Yeah.” She said excitedly, “Wow, thanks!” and hung up the phone!

Sometimes giving a person permission to tell their story and validate their reaction to difficult events is all that is needed. Unfortunately, psychiatry and our mental health system these days almost always provides the opposite – disinterest in the story and distress and disempowerment about the reaction.

— Steve

Report comment

That’s a great story, Steve. Thank you 🙂

Report comment

On the day you posted this, someone in my online recovery forum committed suicide.

Thank you for this. It gives me new ways to think about it.

And – I can’t wait for the next one. When does the thought become a pattern, become an ideation, become a plan, become a danger?

Report comment

Hi JanCarol,

That sounds really hard, JanCarol. Even with on-line connections, it can be so hard (at least in my personal experience) to not wonder what you ‘could have/should have’ done, and hard to not look at it as some sort of personal failure on an individual or group level.

I’m glad reading this was useful to you, and hope it has been to others as well.

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Sera

Thanks for bringing this up and discussing it in an intelligent manner. I did not accept or believe nor do I now believe that just because I wanted to kill myself, and tried, that I was ever “mentally ill”. I just wanted to end the pain caused by countless and overwhelming losses suffered over a period of two years. In fact, I was very much in my right mind. No matter how hard the psychiatrists and the system tried to convince me that I was “ill” I never, ever bowed down and complied with their “diagnosis”. As far as I was concerned there were a lot of very good reasons for me to die at that time. I’ve since changed my mind about all that.

I had a therapists who, although young in years knew just the right questions to ask to open the doorways for me to explore the losses and the changes that resulted from all of them. He also cared deeply for those people he worked with and for. He was pretty phenomenal and a very rare find in a system that doesn’t seem to really give a damn about us or about what is happening in our lives. It was only when I was denied any more individual therapy, because the new head of the community mental health clinic decided that I didn’t pay enough money to continue seeing the young man, that I finally went over the edge.

I agree with you that oftentimes asking a person what’s going on and why they want to die are the most helpful things that can be done for a person in this situation.

I can’t speak for others, but for me it helps when a concerned and caring person asks me why I’m feeling the way that I do. It gives me a chance to talk through things so that I can see them more clearly. Far too many people clam up and refuse to talk with you for fear that talking about wanting to die will make you go out and kill yourself. Exactly the opposite happens for most people. I wanted to talk about what I was feeling but no one would open up and do so.

Report comment

I also find it very interesting that the stats show that a person is more at risk for killing themselves after being released from a psychiatric facility. I wonder why? Could it be the awful, dismal, and depressing fact that almost everyone in the system works to convince you that you have a broken brain for life and will not amount to anything in the eyes of society?

Report comment

“Could it be the awful, dismal, and depressing fact that almost everyone in the system works to convince you that you have a broken brain for life and will not amount to anything in the eyes of society?”

Interesting little fact. Seligmans experiments on dogs and learned helplessness identified three locii of control which determined which animals became helpless. An attribution style which is internal, stable and global actually produces learned helplessness.

And what is it that biological psychiatry is telling their patients? That their ‘illness’ is internal (broken brain), stable (for life) and global (effects you in all environments). Ideal way to produce what might be termed depression in a patient.

People are being taught how to think in the most unhealthy way, and one which will reduce any possibility that they could help themselves.

Report comment

Interesting point. Thanks for sharing it. I believe that you’re onto something here. I work in a state hospital and most of the staff take offense when I talk about how the system teaches learned helplessness to the people on the units. But it’s absolutely true; we do teach learned helplessness as the staff, from nurses to social workers to psychiatrists constantly emphasizes how they have “chemical imbalances” and will have to take the toxic drugs “for the rest of their lives”.

Report comment

There are never any conversations about recovery or finding health and well-being even though recovery is a glaring work in our mission statement. The expectation is that people on the units will come back to the “hospital” again and again so that their drugs can be “fine-tuned”.

Report comment

Just as a contrast Seligmans model would suggest that those who were likely to recover would have an attribution style which consisted of external (the trauma I suffered has resulted in this pattern of behaviour), unstable (it is limited in the amount of time it will last) and specific (the environment I am in can be changed).

Also fascinating that in order to bring about this induced learned helplessness that caging the animals and administering electric shocks induce ‘psychosis’, and given no escape they finally learn to be helpless.

Of course there is no way that any psychiatrist with an external, unstable and specific attribution style would be able to recognise their contribution to the harm being done to their patients. Perhaps some time in a cage and a few belts from a wall socket might give them some insight lol

Report comment

Thanks, Stephen. I really appreciate that his blog has drawn people to share so much personal experience, yours included.

So often people are looking for the next training on what to ‘do’ to someone to ‘fix’ them, and as the holders of the ‘way’ and the ‘knowledge’… I wish instead we could revision this whole system as if we’re all stuck in a series of dark tunnels, and our job is to be together (rather than alone) in the dark, to feel our way along the edges *with* each other and support one another to find our ways out… knowing that the tunnel out for one person may be blocked off or too steep a climb (or what have you) for another but that there’s always another tunnel to find and explore, and that none of us are operating with the knowledge of which one is ‘right’…

-Sera

Report comment

This is a such an important article, and I look forward to reading Pt. 2! Having had thoughts of suicide for many years of my life, I am more comfortable than most people sitting with the pain and discomfort of someone who is talking about wanting to kill themselves, but I do wonder if there ever does come a time when I should seek outside assistance.

I completely agree with you on the circular reasoning / tautology at play in “Research has found that about 90% of individuals who die by suicide experience mental illness.” I think our society falls into a similar tautological trap when we label perpetrators of mass shootings as “mentally ill.” (Of course, this label tends to apply only when the shooters are white, since we have other rough and ready labels for Black males (thug), Muslims (terrorist), etc.) Adapting words from your article: In other words, what does it really mean to say one commits a mass shooting because they’re ‘mentally ill’, if the proof of such mental illness is largely that they committed a mass shooting in the first place?

To me, the mental illness / mass shooter tautology is no more meaningful and informative than the following tautology: “All mass shooters are violent.” Most people would not grant this statement much explanatory power. Yet many people seem content with mental illness as an explanation for mass shootings, and it is used as an “out” in much the same way as the suicide / mental illness tautology is. Again, to adapt your words: It’s an easy answer that absolves us all of blame. If someone has a ‘sickness in the brain,’ then it doesn’t have to be our fault or even necessarily our concern. We can ignore homelessness, racism, transphobia, poverty, homophobia, misogyny, joblessness, lack of good healthcare, the impact of war and violence, and so many other societal ills with impunity because the reason that person killed [a bunch of people] is because they were ‘mentally ill.’ (As an added bonus, we then have a clear solution to the problem: Keep guns out of the hands of the mentally ill.)

I am also interested in the 90% statistic. The fact that it is not 100% indicates that some reasons for killing oneself are deemed legitimate or acceptable or rational by our society (or at least by the researchers). I suspect that killing oneself prior to dying naturally of a terminal illness is one of the acceptable reasons lumped into the 10%. Personally, I am grateful that it is becoming socially acceptable for a person to make choices that might allow her to avoid pain, suffering, and indignation at the end of her life. But, as you say Sera, there is much strangeness and cruelty in our world if we continue to label people “mentally ill” for wanting a way out of the pain, suffering, and indignation of poverty, homelessness, racism, sexual violence, homophobia, transphobia, etc.

Report comment

Great comments, Katie. LOL, on this one, “I think our society falls into a similar tautological trap when we label perpetrators of mass shootings as “mentally ill.” (Of course, this label tends to apply only when the shooters are white, since we have other rough and ready labels for Black males (thug), Muslims (terrorist), etc.) ” Of course, laughed out loud, NOT because this is funny, but because you listed a group of incredibly pathetic belief systems, for which our society at large should know better by now, not to believe. Nonetheless, agree, completely. Don’t kill yourself, we need you!

Report comment

Thanks, Katie! Lots of great thoughts in your comment… I absolutely agree that the violence/psych diagnosis thing is just as meaningless… Though I’d say it’s an assertion that gets made not just to absolve people of blame, but *also* to be able to claim we ‘did something’ about that terrible thing that happened.. (i.e., politicians etc get to say they ‘did something’ with the new law or policy or whatever targeting people with psych diagnoses, and so they get credit for having ‘acted’ and no one really pays attention to whether or not what they did actually made any sense below the surface…) *and* it carries forth an illusion that ‘we are safe’ in a way that also lets people get back to their lives… I.E., The responsible politician/lawmaker acted, now we don’t need to be paralyzed by fear and we can return to normal… voila.. It seems to have become a sort of personal ritual that is all about that process and has nothing to do with what’s actually going on.

Also a good point about the 10% … I’ll have to see if I can find out who those 10% are (supposed to be)… I’m definitely interested to know!

-Sera

Report comment

Great article. Love the title. Looking forward to the second one.

Report comment

Thanks, beckys11! -Sera

Report comment

I threw myself off my roof top three months ago, and am still undergoing rehabilitation. I broke almost every bone in my body and am “lucky” (depends on the day) to be alive. I wrote an article about my attempt, suicide myths and research in December on my Web site, “A Disordered World” – please read it – as it addresses similar issues you raise there – including the failure to address suicide as a primarily a socio-cultural and political, rather than “mental illness” problem.

Here is the link to my article, “No room in the inn: Suicide survivors’ social, and emotional, wasteland”: http://adisorderedworld.com/?p=1355.

I also intend to pursue a more ambitious writing project on suicide, as my physical rehabilitation improves…

As a survivor of violent suicide, I don’t entirely agree with some of the discussion points you raise here – although you get a lot right. I do however take issue with the two questions you think can help people contemplating suicide. Read about the work of Dr. Thomas Joiner, which I summarize in my article. Despite being a psychiatrist – after years of research, he has boiled high suicide risk down to three primary risk factors, none of which have to do with a diagnosis of mental illness. (His father also died by suicide)> His findings resonate with my experience. I really don’t believe any words can help a truly suicidal individual – I think only remedy of social injustice, and action, can. I am told I am a brilliant writer, for example, by hundreds of people – yet no one will hire me due to my “coming out” as someone “mentally ill.” I live in poverty. I am 41, single, and will always be alone and never have children. The prejudice I experience as a result of being branded “mentally ill” and wrongly forced into the system – when 12 years ago I was a successful, high-functioning journalist – is what led me to suicide. No matter how hard I work, I cannot seem to gain a foothold in this world and make a sustainable living. My lack of agency in this world, my complete powerlessness, is what led me to do something I never thought I’d do. It wasn’t my “depression,” my “eating disorder,” or various, subjective and pointless diagnoses. You definitely bring up important and valid points — but I just want to emphasize I don’t believe there will ever be a “solution,” helpful words, or true solace for suicidal people until the prejudice and oppression we and other minorities/disadvantaged people experience ends. It continually infuriates that the “mentally ill”‘ are denied even the opportunity to be recognized as fighting to launch a legitimate civil rights movement. We absolutely need to find some way to come together – there are too many factions, among those of us who think in alternative ways about the psychiatric establishment – and launch a bonafide civil rights movement the likes of which have been seen with other minority groups.

Report comment

A good read Jeanene.

I stepped in front of a truck as a result of being subjected to a forced psychiatric ‘assessment’ after being drugged without my knowledge with benzos. Glad they found that there was nothing wrong with me, and a shame that in order to find that out they have virtually killed a good man.

I note that Joiners three factors are almost givens for anyone who is subjected to forced psychiatry. Goodbye friends/relatives, hello hopelessness, and fearlessness will come from the drugs.

Anyway, thanks for speaking about your experience. It does matter. And there are those of us who don’t have the skills required to convey this important, though ignored message.

regards

Boans

Report comment

Thank you very much for reading about my experience, saying it matters, and thank you equally for your insight about Joiner’s research, Boans. I’m so glad you were able to extricate yourself from The System – even though cost was very unjust. I hope you are in good health now.

Report comment

Not a single day of my life has been worth living since unfortunately Jeanene.

I say that it was the ‘assessment’ that contributed to my major suicide attempt. That’s a little misleading. It was more that the Community Nurse decided to engage in a criminal conspiracy with the person who drugged me with benzos. Of course not knowing I had a degree and studied psychology he then detained me without lawful grounds to do so, fabricating the evidence on the stat dec.

Once I tried to obtain the documents, a further conspiracy, and then when lawyers attempted to assist, the Clinical Director of the hospital authorised fraudulent documents to be sent. Remove the evidence of the drugging, and I looked like a paranoid delusional thinking I was drugged. Funny thing these mental illnesses.

I did try and write about it all in a thread in the community forums but have failed miserably I feel. And in the end who cares if a victim of serious criminal offenses commits suicide, because then we get to call them mentally ill and it all goes away.

These people I feel are great at killing souls and yet keeping the body alive. I look forward to my final rest.

Take care and if you have time take a look at the thread title “the bridge”. My attempt at resolving these issues and trying to ‘heal’ from this brutality they call mental health.

Report comment

Jeanane,

So, I don’t disagree with you, but here’s the thing:

I think what you bring up and what I’m speaking to are somewhat different things. ‘Micro’ and ‘Macro’, if you will… Ultimately, I agree that fundamental changes need to happen in order to stop driving so many people toward hopelessness and feeling completely devalued and that really should be – as you suggest – the primary focus of so much of our energy.

*AND*, If someone is in front of me and in deep pain, I don’t think that I should walk away from them and go fight the social justice issues that may not be solved until long after they’re gone (although, sometimes I’ve found it to be hugely helpful to fight alongside someone who’s trapped in that situation… That that can reignite a sense of purpose and value for them, just in the knowing that people are fighting and that they can be a part of that)… All I’m really saying with those two questions (which I definitely agree aren’t any sort of bigger ‘fix’ and don’t do anything to directly address so many of the real underlying issues) is that in a moment where you are with someone in such pain that those *sorts* of questions can be far, far, far more useful than any assumptions or assessments that otherwise might guide someone on what ‘to do’.

I don’t know if any of that resonates for you, or if I might have missed some aspect of what you meant, but it’s what occurs to me in the moment.

Thanks for reading and commenting and for sharing your experience so honest even in the midst of trying to make your way through. I’ve not been in a place with great internet connection since this blog went up, but I will try to make note to read your blog when I’m back in the normal ‘internet’ world!

-Sera

-Sera

Report comment

Sera – yes, I think you hit the nail on the head. In truth I was so exhausted last night that I did not read your article as closely as I should have, and honed in on those two questions you offered. I agree we shouldn’t walk away to go march the streets when someone close is suicidal! :-). I was just thinking that, for me, the questions you offered probably wouldn’t have helped me(no offense to you — they are still much better questions or statements than most people say to someone who calls in suicidal distress). I DO think those questions could definitely help some; just not me. I guess I need to think more about what, in the aftermath of the past few months, I think could have helped. I did try calling two people when I was on the roof – neither answered… I’m not sure what would have happened if they did…. Anyways thanks again, and I will re-read your piece. You are doing great work here on Mad in America and helping all of us. Your insights are unique and profound.

Report comment

I wanted to qualify my first comment, which I wrote in a bit of a rush. I was just introduced to a writer wh0 – so far; I just started the book – seems to provide the first compelling “words” for reconsidering suicidal impulses, and how right that action seems in my/our darkest moments. I hope I’m able to put these words to use, when I reach another, inevitable suicidal phase (fortunately, I am not suicidal currently). The author is Jennifer Michael Hecht, a philosopher/historian/poet whose books include “Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It.” Among other things, she makes two central arguments which bear consideration – 1) That suicide “unfairly preempts your future self” — that perhaps you owe yourself the chance to live to see a day when you might feel better, and do things with your life you never imagined; you owe yourself at least the chance to reach your potential, and 2) We also need to consider suicide’s effect on humanity before taking our life – apparently (I am learning) sociologists and epidemiologists have found that suicide causes more suicide – they have actually tracked suicide “clusters,” a “contagion” effect, etcetera. Hecht writes, “suicidal influence is strong enough that a suicide might also be considered a homicide… [if this is so] then staying alive has the opposite influence: it helps keep people alive. By staying alive, we are contributing something to the world.”

Hecht also talks about each individual’s value to the community – people need people… But the second argument stated above, in particular, appeals to me. I would never, ever want to play any remote role in increasing the risk another might have in taking their life because they were exposed to knowledge – whether personal or distant – of my suicide. Hecht says by simply staying alive we serve a purpose – and the conviction and despair that my life lacks purpose has always played a strong role in my suicidal urges, when I have them.

I’m grateful I discovered Hecht’s book. I’m exploring a variety of readings/research on suicide and learning much from both my experience, and the many fields which study suicide that I was unaware of (there’s even a discipline of “suicidology”!). So far Hecht provides the most convincing secular arguments I’ve ever heard to reconsider that I’m benefitting my family and society by relieving them of my burden (which I always believe, when I have the desire to take my life). Her book might provide some help in trying to know what to say – words that might actually work – to the seriously suicidal individual.

Report comment

” 1) That suicide “unfairly preempts your future self” — that perhaps you owe yourself the chance to live to see a day when you might feel better, and do things with your life you never imagined; you owe yourself at least the chance to reach your potential”

Something I have not shared with a soul since these events. I saved a childs life, and no one even noticed. And in the spirit of true altruism, I stayed silent about it, till now. So the above statement is correct I believe.

“2) We also need to consider suicide’s effect on humanity before taking our life – apparently (I am learning) sociologists and epidemiologists have found that suicide causes more suicide – they have actually tracked suicide “clusters,” a “contagion” effect, etcetera”

This one contains a ‘loophole’ which anyone wishing to avoid the sin of suicide would know of. I won’t state it here though.

Report comment

Boans – I’m really gratified you finally gave yourself, publicly, credit, for saving a child’s life — you deserve that, and deserve to feel proud of that – it’s so huge! I am glad that that first point of Hecht’s resonates with you. I also understand what you’re saying about the second argument, which I tried to address to some degree in a reply to one of Sera’s comments.

Thanks for all of your comments, too — I was sorry to read last night of your plight since the truck incident. I will try to look up the thread where you wrote about it, when I have more energy; I’m a little overwhelmed with just living right now… I hope that whatever the outcome of the systemic injustice you experienced, you can find things to live for and fight for. You clearly have much to offer.

Report comment

I really think Jeanene that anyone else given the circumstances would have done the same thing. But I pause when I consider what has been done to me, and the way this evil (and I draw the distinction that Nietzsche draws between good and bad, good and evil) has spread like wildfire.

Facts, truth, reality don’t count, only the desired outcome. We need to incarcerate this man and get a cocktail of drugs injected into him. Not because he is ill, but because we need to conceal the crime that has been committed against him (intoxication by deception). This requires a criminal conspiracy to conceal the evidence of that crime, the fabrication of evidence to conceal kidnapping him, and deceiving the next person into mistakenly drugging him for an illness he does not have.

Someone (a nurse) noticed and I was cured of the three serious mental illnesses I got as a result of the symptoms of living with my wife and going to college. Psychotic, bi polar… blah blah blah.

Snatched from my bed by police, denied any contact with family until we have him drugged.

I had one person say to me, it could happen to anyone. True, but your life is different when it has actually happened (a priori vs a posteriori knowledge). I had no idea they were running a human garbage disposal unit and calling it health care.

A medical officer pretending to be a psychiatrist so that he can exercise powers he doesn’t have?

I will never trust another human being again in my life as a result. I can’t even sleep without a ‘guard’ anymore. And this to see if there was something wrong with me?

And my whole community had turned their back on me for asking that a question be asked. Instead the Clinical Director of the hospital removes the documents proving the crimes, and inserts confidential and misleading information to slander me for the lawyers.

In some ways I hope it was his grandchild I saved, because I haven’t seen mine for four years as a result of his criminal conduct.

Truth, it is more worthy of being called medicine than these drugs they are pushing are.

They know not what they do huh? You take care, rest and be heard 🙂

Report comment

Jeanane,

I think these are useful points, and I have heard them before although I haven’t read the book you mention. However, they will inevitably work for some and not for others, and can have the potential to be used in both positive ways and negative, I think. For example, I could easily imagine (and have in fact heard, although not in the precise words you offer above) such arguments being used as judgements or ‘how could you’ sorts of statements… Even then, for some, perhaps they’ll make an impact, but I guess I’ve personally found (both in my own struggle and in supporting others), that those ideas held in curiosity and question and mutual exploration tend to be more effective… But in the end, of course, so much of this comes down to how many common threads there are between people who think about or kill themselves *and* how individual their struggles can nonetheless be.

I’m glad they’ve had meaning for you… I saw a presentation comparing suicide to ebola at a conference, and I found that image/comparison to be a little over the top, but the idea was basically what you describe and focused on how knowing someone who kills themselves may make it feel somehow ‘easier’ or more ‘real’ to think about it for yourself. That does make some sense to me in a sort of existential sort of way, and it’s definitely something i’ve thought about particular in regards to my children.

-Sera

Report comment