I did it. I finally did it. I went and took a Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) class.

Why did I do it? (Why does everyone around these parts keep asking me that?!) Well, honestly, I just wanted to be able to critique it better.

I mean, I had already conjured it up in my mind to be big, bad and terrible based on what I understood to be its basic premise, the affiliated website, and all I’ve ever heard about it from anyone else. However, the truth is that many of those anyones also hadn’t taken it, and so… what if it was better than we all thought? What if we were full of assumptions and were just plain wrong?

First, what is this thing called Mental Health First Aid? MHFA markets itself as:

“an 8-hour course that teaches you how to identify, understand and respond to signs of mental illnesses and substance use disorders. The training gives you the skills you need to reach out and provide initial help and support to someone who may be developing a mental health or substance use problem or experiencing a crisis.”

The training’s target group is the ‘average Joe,’ and not so much someone who specializes in the ‘mental health’ field and is already assumed to have ‘deeper knowledge’ of these issues. Attendees may range from teachers to first responders to family members to your concerned neighbor Sally. In fact, before taking the course myself, I’d always kind of thought of it with the sub-title of, “The average citizen’s guide on how to diagnose and send off your friends and neighbors.” (And, in fairness, I still kinda think of it that way now, too.)

MHFA is also heavily backed by one of the nation’s most powerful mental health-oriented organizations, the National Council on Behavioral Health which has professed the dream of reaching ‘one million Mental Health First Aiders in the U.S.’ (It’s worth noting here that the Council is pro-Murphy Bill and heavily backed by the pharmaceutical industry.) MHFA also has its share of celebrity endorsements. For example, Dr. Oz’s sweet mug even greets you on the front of the MHFA website saying, “Dr. Oz is trained in Mental Health First Aid. What about you?” Now, if that doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will.

But, what does an actual day in the life of Mental Health First Aid look like?

First, I want to take a moment before truly diving in to say that this blog is NOT a criticism of the two trainers who led the class that I took, and I don’t plan to identify them or the organization for which they work. They actually seemed to be putting in genuine effort to create space for me and the friend who accompanied me to challenge the material. Sometimes they even expressed their own contrary beliefs. (Why they then would feel compelled to continue to teach this curriculum as it’s written is a topic I’ll leave for another time… or, at least, later in this blog.) Yes, the class could have been much worse had we found ourselves at the hand of more rigidly minded facilitators. Thank goodness for small favors and all that.

So, moving on to the material itself: I have to admit that there was one (and only one) area where it seemed a bit better than the average tripe, and that was ‘self-injury.’ While it still had some problematic things to say on this topic, it also is probably the first training (coming from the traditional mental health set, anyway) that has ever stated so clearly that self-injury does indeed have a tangible benefit.

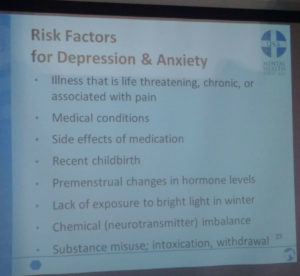

Otherwise, however, it hit all the most stereotypical marks including a nod to the ‘chemical imbalance’ myth (absent the mentioning of the myth part, of course), ignored most environmental factors (homelessness, racism, poverty, and so on), and offered plentiful references to the value of psychiatric drugs (including some solid re-assurances that at least the ‘anti- anxiety’ variety has supposedly “minimal side-effects”). And, had I been playing a drinking game based on how many times the words ‘mental illness’ or ‘disorder’ showed up (verbally or in writing), I would have left very drunk.

anxiety’ variety has supposedly “minimal side-effects”). And, had I been playing a drinking game based on how many times the words ‘mental illness’ or ‘disorder’ showed up (verbally or in writing), I would have left very drunk.

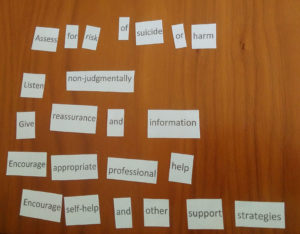

We were also asked to repetitively review (and sometimes chant) the meaning behind MHFA’s foundational tool, ALGEE. (One exercise even required us to put together a sort of word ‘puzzle’ to further help drill it into our heads.) It goes like this:

A is for ‘ Assess for risk of suicide or harm’

Assess for risk of suicide or harm’

L is for ‘Listen nonjudgmentally’

G is for ‘Give reassurance and information’

E is for ‘Encourage appropriate professional help’

(Give me another) E is for ‘Encourage self-help and other support strategies’

And at least some of that didn’t even sound half bad… I mean… not the ‘listen nonjudgmentally’ part anyway. By the way, as it turns out, ALGEE is also the name of MHFA’s Koala bear mascot. (I always love when tools to push people along the ‘mental health’ pipeline masquerade as ‘help’ and are marketed with cute little stuffed animals… don’t you?)

nonjudgmentally’ part anyway. By the way, as it turns out, ALGEE is also the name of MHFA’s Koala bear mascot. (I always love when tools to push people along the ‘mental health’ pipeline masquerade as ‘help’ and are marketed with cute little stuffed animals… don’t you?)

Really, it was all to be expected, though. (I’d actually even met a live version of ALGEE all dressed up and cheerfully taking photos with conference attendees at a National Council conference just a year or so before.)

What I absolutely didn’t expect, though, were some of the exercises that encouraged us to sink to truly bizarre levels of judgement and MHFA’s own brand of ‘disordered thinking.’ Here’s one of my favorites: Early on in the day, the trainers literally asked participants to arrange a list of ‘disorders’ by severity. No, seriously. (Stop it! I’m so not kidding!) The list included (in no particular order):

- Moderate depression

- Severe depression

- Non-invasive breast cancer

- Severe asthma

- Epilepsy

- Low back pain

- Uncomplicated diabetes

- Severe schizophrenia

- Severe dementia

- Gingivitis

- Severe vision loss

- Severe post traumatic stress syndrome

- Paraplegia

- Severe chronic bronchitis or emphysema

Here’s the list re-ordered by Mental Health First Aid from (supposedly) least to most severe:

- Gingivitis

- Low back pain

- Uncomplicated diabetes

- Epilepsy

- Non-invasive breast cancer

- Moderate depression

- Severe asthma

- Severe vision loss

- Severe post-traumatic stress syndrome

- Paraplegia

- Severe chronic bronchitis or emphysema

- Severe depression

- Severe schizophrenia

- Severe dementia

That’s right, folks. So-called ‘moderate depression’ is seen as worse than breast cancer, but both ‘moderate depression’ and breast cancer still trump blindness or not having use of one’s legs. And, at least three potentially fatal medical illnesses (cancer, severe asthma, and emphysema) are apparently all preferable to schizophrenia. Hell, apparently just about everything is preferable to the devastation wrought by ‘schizophrenia!’ (Unfortunately, this last point is a theme that continues throughout the training.)

If you’re feeling particularly masochistic, you can actually watch a video of people participating in this exercise (third one down), although the instructor in this version refers to the ordering as being based on ‘least to most disabling’ (as opposed to least to most severe). Not that that improves anything. At all.

There were a host of other strange exercises, including relatively inexplicable requests to ‘draw’ representations of the symptoms of depression and anxiety, and to alphabetically call out words that we commonly hear in our culture related to ‘mental health.’ (My friend snuck in ‘pharmaceutical industry’ when we reached the ‘P’!)

There were a host of other strange exercises, including relatively inexplicable requests to ‘draw’ representations of the symptoms of depression and anxiety, and to alphabetically call out words that we commonly hear in our culture related to ‘mental health.’ (My friend snuck in ‘pharmaceutical industry’ when we reached the ‘P’!)

And then there was their handling of all things ‘psychosis.’ While the curriculum required the instructors to parrot the line about ‘people with psychosis [being] more at risk of being victims of violent crime,’ literally everything else flashed a virtual neon sign of ‘danger.’ For example, only when reviewing the section specifically labeled ‘psychosis’ did we come across any tips for ‘de-escalation.’ And, while film clips (oh yes, there were film clips for each diagnosis!) for earlier labels portrayed people benignly immobilized on couches, the ‘psychosis’ clip compounded the already readily apparent fear and agitation with echo-y effects, and featured two women who were clearly afraid to enter their neighbor’s home when they realized he was ‘arguing with someone who wasn’t there.’

Check out this segment of said clip (starting about 50 seconds in).

It charmingly focuses on the fact that ‘psychotic’ neighbor man has stopped taking his ‘medications.’ The full clip (sadly, not available in its entirety on-line) also concludes with one of the women threatening this man (who they lured out of his home against his protests and who was not making any of his own threats toward himself or others) with calling the police if he doesn’t agree to call crisis evaluation services or go to the hospital (a perfectly satisfying ending for the MHFA set).

Finally, at the end of the day, when we were given what amounted to our MHFA certification exam (passing grade required to become official), both questions focused on this particular area were clearly written with fear, danger and violence in mind:

#4: You’re outside the pre-school waiting to collect your child when you notice another adult behaving strangely. He’s walking in circles and having a heated argument with someone who isn’t there.

Do you:

- Ignore him. He’s not your problem as long as he doesn’t come anywhere near your child.

- Assess the situation for risk of harm to yourself or others. If needed, encourage others not to be confrontational with him. If you feel safe and able to approach him non-confrontationally, ask if he’s OK and what help he might need. Consider notifying school personnel.

- Approach him directly, standing squarely in front of him and making clear eye contact. Put your hand on his shoulder and be assertive, telling him that he needs to leave the area.

#8: You’re at a party when one of the guests becomes violent. She has a knife and it’s obvious that she’s responding to voices only she can hear.

Do you:

- Try to gain her trust by pretending you can hear the voices too. Agree with everything she says until you can get close enough to take the knife away from her.

- Take her down physically be whatever means possible and have someone call the police.

- Call 911. While you’re waiting for the police and mental health crisis team to arrive, turn off the music and encourage people not to confront her or get too close; make sure your exist is not blocked. Perhaps speak calmly to her, but don’t argue with her.

Interestingly, several people (from trainers to the general public to some of my Facebook acquaintances) have attempted to defend MHFA as ‘worthwhile because it teaches compassion to the average citizen’ (or some variation on that theme). Most of them have acknowledged it has its shortcomings (though, they may still argue as to whether MHFA is more or less severely impaired than cancer or diabetes). Few of them seem to have even the slightest inkling of just how dangerous such mass-marketed tools can become.

In fact, I might argue that it’s the guise of ‘teaching compassion’ (along with the few other benefits it might genuinely purport) that is precisely what makes it so dangerous for all the masked misinformation those benefits allow it to slip in unnoticed. Haven’t we yet learned that teaching people that so much human distress boils down into illness does nothing to reduce ‘stigma,’ and in fact, makes discrimination worse? Aren’t we now wise enough to see that the more medicalized we become, the more disability and despair plagues us, as well?

There is no benefit to teaching more people that this is all ‘mental illness,’ or playing part in increasing its numbers and count. There is no benefit to ‘one million Mental Health First Aiders’ further cementing knowledge based on fiction or assumption, or creating higher walls between us and unlearning. The suggestion that all of this loss may somehow be ‘worth it’ because we’re teaching people to talk openly, comfortably and with care about ‘mental health’ is beyond foolish if it’s tied inextricably to labels and language that damage us at the same time.

There are other options to teach ‘compassion,’ and ways to talk to people about their distress or unusual experiences. There’s no reason to talk about MHFA as if it’s this or nothing. And, hell, if you don’t have access to one of those other alternatives, create your own! Anything would be better.

At the end of the day, I completed this training and I also completed the final exam. But, in true-to-me form – for about half of the questions – instead of choosing from among the answers available, I added a fourth option. I turned in my test that way, and seeing it was ungradable and that I would inevitably fail and not earn my certificate, one of the trainer’s asked me:

“Could you just answer the questions how you think Mental Health First Aid would want you to answer them?”

No, I’m sorry. I can’t. It’s not worth it. Not even for a second. I refuse to fall into that trap of feigning belief in something harmful for the sake of some perceived or implied gain. And, I can only hope that you’ll come to see that it’s not worth it, too.

Wow! Thank you so much for this article. Much as it amused me, it also scared me to the core. I recently read an evaluation report of the use of MHFA in “supporting people working with the Prevent agenda.” The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 contains a duty on specified authorities in England, Scotland and Wales to “have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism.” This is known as the Prevent duty. There is much going on in the UK about the link between “mental illness” and “radicalisation” (the link itself is not clear, does radicalisation cause mental illness or does mental illness cause radicallisation – the mind boggles). And this section (among many) from the report seemed especially problematic:

“I would never as a Police Officer explain to a supervisor I needed guidance on how to investigate a crime, because the first question they would ask is ‘what sort of crime?’ If you know the type of crime i.e. Fraud, the supervisor can signpost you to the Fraud Team.”

“I have been in multi-agency meeting where a delegate suggests there is a mental health problem, the mental health practitioner correctly asks what sort of mental health problem to which the delegate had to admit they did not know, other than it was a mental health problem!”

The MHFA course is supposed to be helping the concerned person identify the correct mental health problem just as they would be able to correctly identify the type of crime. More than that, it is the juxtaposition of “crime” and “mental health problem” that spoke volumes to me.

Report comment

Jayasree,

Thanks so much for reading and taking the time to comment! It was fascinating (and frightening) how much ‘double speak’ there seemed to be in the Mental Health First Aid training. For example, they do say multiple times that as a ‘non-professional’ it is not your job to ‘diagnose,’ and yet so much of the training is spent ‘training’ people to recognize which ‘mental health problem’ is at hand.

Similarly to the links being made between psychiatric diagnosis and terrorism, I’ve even begun to see links be made by some between psychiatric diagnosis and extreme racism. It is indeed truly terrifying.

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks for the great Article Sera,

I do identify with the double speak.

We ARE seeing links between psychiatric prejudice and extreme racism. I notice this in the UK. Nobody would dream of talking to an ethnic minority person the way they talk to a person with a ‘diagnosis’.

Though this approach usually gets switched on when a person questions the status quo. Otherwise I think ‘diagnosed’ people are perfectly okay providing they are fluffy.

The reason for this is that Psychiatry is a very insecure ‘medicine’.

Report comment

I immediately wondered how this course was going to be used to aid not the patient but the police and their so-called war on terrorism. They are using community members to help them but what we must beware of is their use of entrapment.

COINTELPRO is back and has been back since the 1980s. In the US, it has infiltrated groups like National Lawyers Guild, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter. Moreover, it affects individuals, particularly whistle blowers, activists, and writers, but also more vulnerable groups like those who are poor, minorities, or suffer mental illness. COINTELPRO sows paranoia.

As well, there are thousands (probably tens or hundreds of thousands) of individuals complaining of Voice of God technology being used against them. This is a real technology – patent available & was used in the Gulf War. Today it is called voice-to-skull or V2K. It mimics schizophrenia.

Communities (Infraguard neighborhood watch groups) and community services (mental health, social workers, etc.) are being co-opted to herd “patients” (ie, dissenters and undesirables) into law enforcement where they can be institutionalized or incarcerated. Some commit forced suicide. Others have committed homicide (Myron May, Aaron Alexis, et al).

This is a serious issue. It’s called ‘no touch torture,’ ‘prison without walls,’ and slow kill for a reason.

It’s imperative we raise awareness – however, exercise extreme caution when doing so. Glenn Greenwald and Amy Goodman have managed to write about COINTELPRO; but many fear their careers will be ended. It’s a slippery slope – but we must overcome this grave injustice.

Report comment

Can you provide any more info or links to such? Cointelpro is a fact of history by now, so talking about the past isn’t as risky as talking about the present. Is there a way for someone to definitively determine whether this technology is being used against them?

Report comment

That quiz reminds me of an incident many years ago, when I encountered a gent reciting his life history to the sky. I chose to leave him alone, as he was obviously talking to God and didn’t need some chump interrupting his conversation with the Divine.

Report comment

Thanks, bcharris. 🙂 I wish more people were comfortable with creating that sort of space for people who might be doing something that they don’t necessarily fully understand.

-Sera

Report comment

I was one of those who was DSM defamed and drugged for belief in the Holy Spirit and God, and by a paranoid of a non-existent malpractice suit PCP, a child abuse cover up profiteering “holistic Christian talk therapist,” a couple of Jewish psychiatrists, and at an ELCA Lutheran hospital. The psychiatrists in this country apparently don’t know it’s illegal in the US to torture Christians for belief in God and the Holy Spirit, and they believe Jesus’ theology of treating others in a manner that they would like to be treated, does not apply to them. Glad you are wiser, bcharris.

“No, I’m sorry. I can’t. It’s not worth it. Not even for a second. I refuse to fall into that trap of feigning belief in something harmful for the sake of some perceived or implied gain. And, I can only hope that you’ll come to see that it’s not worth it, too.” Good for you, Sera.

It strikes me that since the DSM was confessed to be lacking in validity and reliability by the head of NIMH in 2013, that this country should be getting rid of the scientifically invalid DSM stigmatization system all together. I know the problem is the whole iatrogenic illness creation system, that is today’s DSM theology, is very profitable. (The ADHD drugs and antidepressants create the symptoms of “bipolar.” And the “bipolar” drug cocktails create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. And the neuroleptics create both the negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia,” via NIDS and anticholinergic toxidrome.)

But creating “mental illnesses” in people with drugs is neither ethical behavior, nor “mental health care.” And the medical evidence is in proving “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).” Which basically means today’s psychiatric industry is really nothing more than one giant child abuse covering up industry. The psychiatrists just changed from claiming Jews were “mentally ill,” to claiming child abuse survivors are “mentally ill.”

So how much longer are this fraudulent DSM classification system, and the toxic torture drugs of the psychiatrists, going to be propagandized, used, taught in our universities, and forced onto innocent child abuse victims and those who dealt with easily recognized iatrogenesis? It strikes me the entire system should just be scrapped. And all in this country, including the psychiatrists, should return to an understanding that “all people are created equal.” And profiteering off torturing and murdering child abuse victims, or those who dealt with easily recognized iatrogenesis, based upon scientifically invalid “mental illnesses” is no better than profiteering off torturing and murdering Jews based upon the insane notion being a Jew is a “mental illness.” It’s time for “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions” to end.

Report comment

I’m arguably part of the establishment. That said, I took mental health first aid. 8 hours of my life I will never get back. And I was appalled at the lack of understanding of even the misinformation (if that makes sense?) that is generally available. Nobody understood the 10,000 plus ways people cope (which I expected), but nobody understood traditional old school treatments either. More than a few people offered the “hold them down” answers, as though a person experiencing some form of non-consensus reality should be treated like they are having a seizure or something.

Report comment

seltz, Your referring to some of what is conveyed in this training as ‘misinformation’ makes absolute sense. It sounds like your training may have been even worse than mine!

-Sera

Report comment

Our training did include a video from speaker Kevin Hines, who jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge and survived. That part was more instructive than anything.

Report comment

I’m certainly aware of Kevin, but don’t know much about what he has to say… And, admittedly, I worry that the media seems to give voice to people who make suicide attempts that seem more sensational (e.g., jumping off the bridge), sometimes to the exclusion of those whose actions were quieter and less ‘exciting’ to hear about, but who have a ton of wisdom to share… I’m sure I’ll get a chance to hear his message soon enough.

-Srea

Report comment

You”l appreciate this – Recently, at an MD’s appt., he handed me a “drugs contract”, and asked me “how I felt” about signing it. I glanced at the 3 dense pages of legal boilerplate, and casually said, “Well, I’d rather jump off a bridge.” Yeah, it was a stupid, “throw-away” type of comment, but he jumped on it like a starving dog on Alpo! He ranted on for 10 minutes about whether I was “suicidal”. Please enjoy what humor there is. “Mutual Assured Destruction” is insanity. Jumping off a (tall enough) bridge is simply stupid suicide. ~B.

Report comment

Wow, the first thought I had after reading this was, “Sheep!”, but of course I’m trying now to think about it as “people acting like sheep”, rather than “people actually are idiotic sheep”, thanks to Richard and Steve.

Still, how much faith can I have in my fellow humans after reading this? If they are not mindless simpletons, most of these people certainly act like it. I guess it’s just hard to see that these people really don’t know what they don’t know. They have no idea what they are missing. I do have to wonder if people drawn to this sort of thing are those who want to deny the real causes of distress in others/their family using the simplistic biological model.

The koala bear thing is pretty perverse. It’s a cute, harmless animal. But the people using it as their mascot will increase your chances of getting diagnosed and drugged with all the bad – and sometimes deadly – outcomes that follow from those things on average. This is one case where the presence of a koala bear may correlate with a deadly outcome.

The part about psychosis is particularly upsetting. As has been repeated ad nauseum, there is no such thing as lifelong schizophrenia, but a syndrome or continuum of psychotic states that may be more or less severe, last more or less long, have many different causes at different times. And those states are not brain diseases, although the extreme distress people experience is expressed in brain chemistry.

This motivates me to keep working on my own site about psychosis so I can put it out there as an alternative to this neurotrash.

Report comment

Sera et al,

Here’s what this group’s mascot should be:

http://www.amazon.com/Aurora-World-Misty-Flump-Sheep/dp/B00SUE8V22/

Isn’t it cute?

Report comment

BPD, Hah, that would make for an amusing mascot, indeed. 😉 Good idea!

Thank you for taking the time to read, write, and offer up a new mascot! 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Sera, Can you give more details about how exactly you challenged the disease/defect model at this conference? Did you actually state that psychiatric diagnosis is invalid, there is no evidence for a disease process causing disturbances in psychotic people, that the evidence supporting long term use of psych drugs is weak to nonexistent?

And if so what did people say to those things?

Report comment

BPD,

Well, I definitely said on multiple occasions that psychiatric diagnoses are not founded in science, pointed out the research on people being most likely to kill themselves after forced hospitalization, and that psych drugs can contribute to many problems… Gave details about the Open Dialogue system, along with encourgement to go watch Mackler’s film on Youtube… Spoke specifically to my concerns about the threatening nature of the video about the man referenced above… And lamented out loud the lack of ‘risk factors’ that were environmental (like discrimination and failure to meet basic needs)… I also gave a lengthy description of an alternative way I may have supported the man in the video that included asking him about his sleep and food, *entering* his home rather than luring him out, engaging in conversation to explore his fears and voices, etc…

In truth, I was actually making a conscious effort to not throw the whole thing off too far because – while I often do go places just to heckle and counter their material… in this instance, I really just wanted to know what the deal with this whole MHFA thing was…

Report comment

BPD,

Most people don’t know anything about a non disease model, and this would seem to include most General Practitioners.

We (at MIA) know all about studies into suicidal reaction to medication and anti depressants but GPs still prescribe (and they are not all evil).

The message isn’t getting through.

(I think your description of ‘schizophrenia’ is enlightened)

Report comment

Ok Sera thanks. And I was wondering, did these revelations make the people take notice and seem to get it? Or did it seem to go in one ear and out the other, with only token acknowledgment? I’m guessing the latter.

Fiachra, that description of psychotic states is based on my reading of books by therapists that work with psychotic people outside of the established system and see how different they are as individuals and how the can get well with sufficient time, support, and understanding. And, also based on my own experience of being psychotic for several years. I was once a voice-hearer… no longer… and was once nonfunctional and terrified most of the time, but that no longer either. Extreme states of fear and defensive reactions against terror (the cause of so-called schizophrenic symptoms) are extremely individual and variable depending on many factors like past relationships, current stress levels, how the individual conceptualizes their distress, the culture, etc. There is no one schizophrenia disease and it’s sad to see people think so simplemindedly.

Report comment

Hi BPD,

Your descriptions are brillaint regardless.

My experience was of years of uselessness on psychiatric medication and lots of completely new problems on coming off medications. But I did get around the problems with fairly straightforward help.

With the right direction I wouldn’t even make a big deal out of recovery. Though the disability cost the country a fortune.

I think we’re still in medieval terms regarding mental health in the developing world and we’re getting worse, not better.

Report comment

YO!, “BPDT” – go to “lyrics.com”, and read Frank Zappa’s “I Am the Slime”, from his album “Overnight Sensation”. It explains how the American people have been propagandized, and literally brainwashed, for decades. I myself prefer the “sheeple” metaphor!…. LOL

Report comment

Mental First Aid should include a view of the MIA webinars Nutrition and Mental Health by Bonnie Kaplan and Julia Rucklidge

Report comment

amnesia,

Good luck on convincing them of that one. 😉 Though, in truth, I’d vote for taking some things *out* before I’d necessarily vote for putting other things in… In my experience, adding a few good things in amidst a bunch of terribleness usually still means that people only hear the terribleness (if for no other reason than it sends a message that already fits with what the person believes or has heard before)…

-Sera

Report comment

Well, I did take gluten out of the diet of a woman who heard voices and cut herself – she had been doing so for 15 years. Her life was the non-stop revolving doors of a psychiatric hospital. She stopped cutting and her ‘voices’ went to a minimal. She had no hospitalizations for a full year and was very happy – and for the first time in her life – to get a job. Bread went back into her diet at the suggestion of a doctor who was concerned about her not getting enough fibre – (there are other sources of fibre) – within a month she was back to hearing command voices and cutting herself and back to the hospital where she died after receiving ECT. She was barely over 30 years old.

Report comment

I believe you. I’ve been encouraged to cut certain foods for non ‘mental health’ reasons ;and I do notice an emotional benefit.

Report comment

The negative psych effects of wheat and gluten were discovered by an allergist decades ago. Since he wasn’t a psychiatrist, he was naturally ignored, and since this didn’t concern a matter directly and only involving brain function, it will doubtlessly continue to be ignored in orthodox psychiatric circles.

Report comment

Another great article Sera…although this one is just so sad…

The saddest part of Mental Health first aid is the fact that “ordinary citizens” are being taught to identify people behaving strangely and than are encouraged to recruit them for medicalized treatment, with the assumption that this will be helpful. Feels fascist to me.

People should be taught to be polite, or otherwise just leave other people alone if the potential “helper” lacks the intelligence, courage, and/or resources to be of real assistance. Yes, we will see homeless and ranting people on our streets under such circumstances, but I’m uncertain that American society has developed a less harmful alternative. If you feel so guilty, have a conversation, give them some money or buy them some food (or bring them into your own home if you’re THAT guilty).

Personally, I wouldn’t want anyone’s “help” under these circumstances. I’d be perfectly happy handling my suffering on my own, considering the cultural climate available to me.

Spiritual teachers GI Gurdjieff and Chogyam Trungpa both spoke of “idiot compassion”, “compassion” without courage or intelligence. This is the ignorant mentality we are seeing promoted by these cultural overhauls led by the faceless MH establishment.

Report comment

Hi Rooster,

Thanks for takign the time to read and comment… I completely agree that it is all very sad, and yes, that sometimes just leaving people alone would be better than dragging them into a system that is prepared to do little more than cause harm.

I tried to have a bit of that conversation with another participant in the training who was defending the threat of calling the cops if the man in the video didn’t agree to meet with crisis… I asked him how he would feel if someone lured him out of his home when he was posing no threat to anyone and then threatened him with police or hospital… Momentarily acknowledgement *seemed* to flicker across his face, but then I think he settled back into ‘well, that wouldn’t happen to be because I’m not like THAT guy.’ (He didn’t say anything of those things… It’s just what appeared to be happening based on his facial expression, and other things he said…)

-Sera

Report comment

Yes, I wondered about that, myself, particularly doing it without seeing how our suddenly non-medicated guy is faring and what he’s doing. You want to have an existing reason for involving the cops; you don’t want to make one. Is there something wrong with diplomacy nowadays or is it bad for mental health?

Report comment

I have a neighbor below me who talks to people that aren’t there. I leave her alone with them when she carries on conversations at night. She’s not hurting anybody. They seem to keep her company.

Report comment

How do you know she’s not rapping?

Report comment

So many people have so many different ways of getting through the world 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Thank you Sera for this article. And notice, the article is primarily about psychotherapy issues, not drugs, electroshock or lobotomy.

In my opinion psychotherapy is where we need to set the bar of zero tolerance.

I had this friend before who had worked for a long time in various mental hospitals as a technician. There was a time in my life when some extreme things were happening, and it showed in my countenance. So this guy used to talk to always talk to me, “****name***, so how are you feeling today?”

Finally I just said to him, “***name***, you are talking to me like you talk to your mental patients. I’m not going to put up with that ( very clear baiting, taunting, and open ended threatening tone, letting him know I was ready to take his head off right then. ), and they shouldn’t put up with it either!”

We need to organize. The main problem I see in the routines for talking to the suspected crazy is that the questioner is not really listening, not really taking it seriously. They are talking the position that everything the suspected crazy is saying is just about what goes on in their head. That kind of talk, like it is all just in your head, enough of it, would drive anyone into the behaviors we label as schizophrenia.

So we need to organize and offer assistance in getting fairness and redress in life’s various situations. We won’t be able to solve all problems, but we should be able to take on some of the bigger ones.

Our society has become very informal. Okay, but people misuse that to torture and torment people.

Thank you Sera again, for a wonderful article.

Nomadic

Report comment

Hi Nomadic,

Thanks for reading and commenting… Technically, Mental Health First Aid isn’t about psychotherapy either… Rather, it seems largely about pushing people into drugs, therapy, and so on…

But I do agree with you that the fact that so many people start from a point of not believing that what people say has meaning (including those trained by Mental Health First Aid) is a serious (and ‘crazy’-making) issue!

-Sera

Report comment

I say it is psychotherapy because it is talk instead of drugs.

But it is a kind of talk which could push anyone over the edge. The primary mistake the patient is making is faulty friend or foe identification. Once someone discloses feelings or personal matters to anyone accept a true comrade, they are only hurting themselves.

So I wish I had a card I could give people to hand out whenever in such a situation, so that the mental health worker would be directed to call me. Besides issuing ultimatums over the telephone, I really would start filling out the lawsuit forms right then.

I carry in my wallet the biz card of a very aggressive and well known defense attorney, as well as one for an ACLU linked police monitoring group. These are there in case police ever go through my wallet. The more socially marginalized you are, the more they think they can do to you.

Again, excellent article!

Nomadic

Report comment

Also, its not just that a mental health professional might not believe what a client is saying, its that they dismiss it’s relevance. Again, they act like it is all in your head.

And then, isn’t that what psychotherapy is really about, convincing you that the only problem there ever was was your own stubbornness and refusal to forgive and forget, and measure up to societal expectations.

And so people who are the family blacksheep, or our society’s blacksheep, end up having to live in extremely stigmatized states.

Nomadic

Report comment

That’s not what my therapy looked like, either what I received or how I handled clients myself. I was always about POWER – getting more power for the client, both internal and external. Some of it is obviously exploring options outside of what you’d normally consider, but a lot of it was helping understand how NORMAL it is to be upset about a life and a society where you’re constantly disempowered and at the mercy of others. Finding ways to be LESS at their mercy was the core of what I found helpful to anybody, regardless of what was bothering them. That’s what I think real therapy should be about!

—- Steve

Report comment

Do tell, what were some of the final exam questions in the armchair psychology training, and how did you answer them?

Report comment

I wanted to know this too. Sera, I suspect I would have answered as many or more than you did with my own answer. I would have failed their test!!!

Report comment

Let’s see… Here’s a few more:

1. You’re at home watching a favorite movie whe n your ex calls sounding really upset and making statements about wanting to kill him/herself.

Do you:

a) End the call quickly, this is not your problem. People who threaten suicide rarely go through with it. Your Ex can take care of him/erself, and you are no longer together.

b) Ask your Ex if s/he has a plan or has made any prior suicide attempts and consider if s/he has the resources to attempt suicide now. Discuss ways s/he can stay safe, such as calling a suicide hotline, a mental health crisis team, or 911.

c) Ask how s/he intends to kill him/herself. If your Ex doesn’t hav e plan s/he’s probably not serious and so you can go back to your movie without worry.

I answered d) And said something like ‘None of the above. I’d talk, ask what’s happening, what they’re feeling, if there’s anyone they trust they might want to be around, etc…’

2. You notice that a family friend who is a college sophomore has been functioning less well as the school year progresses. At the beginning of the semester, she was vibrant and seemed to enjoy her classes. Now she has clearly lost weight, seems depressed, has a hard time paying attention, expresses odd ideas sometimes when you talk with her, and seems to have lost her motivation.

Do you:

a) Tell her she needs substance abuse treatment and you are sorry she succumbed to the drinking and drugs that are all too common at most colleges.

b) Suggeste that she get academic counseling or tutoring to help her get back on track.

c) Express your concern and offer to help her get an appointment at the college counseling center or other service.

I don’t remember quite what I said, but it was another ‘D) None of the above’ response…

There were others, but I didn’t do as good a job as I might have of capturing them all with pics on my phone!

The two worst ones were the ones I included in the blog above, but as you can see – there is a trend toward assess and push into ‘professional services’…

-Sera

Report comment

I wonder if anyone brought up the possibility under question 1 that the person threatening suicide might be a domestic abuser. Suicide threats are a common tactic used to make a departing partner feel guilty and re-engage with the abuser. Any discussion of this question that doesn’t raise that point is, in my view, extremely irresponsible, because the answer should be VERY different than in a non-coercive ex-relationship.

The whole thing sounds like a very juvenile attempt at indoctrination. I admire you for being able to sit through it without becoming physically ill.

— Steve

Report comment

It was just on the exam, and not discussed out loud, but yes I’ve been in that situation before (suicide threats used to control or force one to stay in relationship) so I get your point and it’s very valid… Who KNOWS how they would have responded to that had it been discussed, though…

-Sera

Report comment

It should have been discussed, if you really want to have people providing “first aid” in this kind of situation. This would be like forgetting to mention that blood spurting from the body intermittently means an artery has been cut and immediate action must be taken. You could end up getting someone killed if you handle that situation poorly. I find it inexcusable, but not surprising.

Report comment

OMG you’re helping people cheat!

Actually they’re all trick questions as there are no right answers.

Report comment

I don’t like the look of the old lady in the video.

Report comment

Sounds creepily like the Peer Support course I did in Reading, Berks, UK.

I complained to the head office who promptly sent my complaint to the trainer who asked to meet me in a cafe. Stupidly I agreed and she was angry that I had not told her directly.

It’s times like this when I think custard pies and glitter bombs are in order

Report comment

I wish I could claim that all peer support trainings were inherently better than this mess… but they’re not… which is very, very sad.

Report comment

Sad and dangerous.

We were give a list of diagnosis (depression, schizo, anxiety etc) and then asked to list appropriate treatment. The treaments were drugs, with talking as alternatives.

I questioned both the dignosis and the drugs and the tutor agreed there were controversies but did not encourage much discussion and certainly not the required answers for the full marks.

At no time was anyones personal experiences solicited.

Serious situations were asked for and the correct response was refer back to the psychiatrist. At no time was discussion of people’s experiences of psychiatry elicited despite the room being full of service users. So if someone is having a crisis and hates thier psychiatrist, too bad because the peer support course said to refer them back.

Report comment

… I had already conjured it up in my mind to be big, bad and terrible…

When I first saw that lead-in it sounded like it would be leading to the conclusion that actually it wasn’t that big, bad & terrible after all, and thought “this should be interesting”… but I do the same kind of “know your enemy” stuff, like listening to Limbaugh & co. to understand how the enemy reasons.

Three observations, nothing too controversial:

— What prompts one to decide that someone else needs to be “assessed,” or is it totally random?

— The ALGEE formula seems to mandate “appropriate professional help” in every case. So as soon as you “assess” someone you will inevitably be recommending they get “help”?

— Instead of a bear shouldn’t the mascot be some sort of seaweed?

Report comment

Hello again Oldhead,

1. Basically it seems to come down to whether or not you’re seeing any ‘signs or symptoms’ of various diagnoses, which they do spend a fair amount of time reviewing via slides and their fab book of which I now have my very own copy…

2. Yep, there are even comments in some of the films about how it’s critical to get help as *soon* as possible, though they’re not too clear on what doom befalls one who does not… But lots of emphasis on ‘professional help’ for sure…

3. Well, yeah, there’s lots to be said about the acronym and the mascot… Oy. The whole thing started in Australia, so that’s where it comes from but beyond that I don’t know what to say about it other than ugh!

-Sera

Report comment

So by inference, the logical progression would be that any suspected glint of a “sign” or “symptom” leads to an “assessment” which inevitably leads to a recommendation of “treatment.”

Report comment

Odd that it started in Australia. The Australians also have a word- wowsers- that refers to people who feel themselves in such command of their lives that they want to take command of yours as well.

Report comment

Excellent article, Sera! I’d wondered for a while about the content of these courses and now I know. And I’m so pleased you rebelled and offered sensible alternatives in the quiz.

Report comment

Thank you, Gary! (And appreciated your recent article, as well!! Those phrases… or, more importantly, the belief systems that lead to some variation of them… are still very much alive and well!)

-Sera

Report comment

For those of you who make it down this far in the comments section, there’s so much I could have included in this blog that I didn’t… Here’s one additional ‘tidbit’… In one of the packets we were given, there’s a ‘Who Am I’ game with substances… Here’s my favorite (I think it will be yours, too):

Who am I? ___________ I am a stimulant and i come in many forms: power, tablets, capsules, crystals, or liquid. I am known on the street as ‘crystal,’ ‘speed,’ ‘base,’ ‘ice’ or ‘shabu.’ I can cause ‘speed psychosis,’ which involves symptoms similar to schizophrenia. The only proper use for me is for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), under the direction of a physician.

Oy.

Report comment

Why, you’re amphetamine, of course. Brother Dextro keeps himself busy filling tablets that schoolchildren consume, while cousin Meth hangs out on the street, looking to turn his admirers into wasted, toothless speed freaks advertising that scurvy is still alive and well in the 21st Century.

Report comment

Don’t forget Uncle Ritalin, who is in denial that he’s actually an amphetamine relative, though he does have Cocaine relations on the paternal side…

Report comment

Tell Uncle Ritalin I’m sorry.

Report comment

That’s OK, he’s used to people pretending he’s not part of the family.

Report comment

Thanks, my comments on ADHD stuff just got better.

Report comment

“Drugs are bad unless we tell you to take them, then they’re good.” Pretty simple, huh?

— Steve

Report comment

I was taking these classes to work at a drug and alcohol treatment center. The called it behavioral or mental health tech basically “counselor lite”.

It seems that for every hour I would get to work with a client using what I learned from recovering myself I would be basically working 7 hours for “The Department of Children and Families” doing paperwork “documenting” . The Department of Children and Families… think about that name for a second, talk about Orwellian police state, how about stay away from my family and kids ??

But here is the real kicker, I would be expected to work with probation officers and RAT OUT clients if say one of them had an anxiety attack and ran to the bar or liqueur store trying o make it go away. Happens all the time. I know how those feel, its hell.

Hi authoritarian terd with the usual IQ deficiency, glad you called… (social niceties go here) I am a scumbag back stabber and the client I am trying to “help” was caught drinking last night…

Never in a Zillion years.

I want to help people not be part that wrenched system that led many of them to having problems spiral out of control in the first place.

The class I took pushed the usual psychiatric lies and bull too.

Report comment

“We believe that our findings of rising suicide risk with increasing recency and frequency of contact point toward a strong independent effect of criminal justice history,” the authors write. “Thus, exposure to the criminal justice system in itself may contribute to elevating a person’s suicide risk, rather than simply reflecting the traits and characteristics of people who come into contact with the system.” https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/02/110207165436.htm

Well thanks capt obvious for writing this paper. But anyway “just doing my job” (A Nazi Quote) I have to tell your PO you drank yesterday and add more misery to your life.

I find some dark humor in the fact that those who engage in victimless crime don’t create any real victims until they are put behind bars, at which point they cause the State to steal $47,000 a year from the tax paying public.

I guess that’s enough posts from me. I kind of over do it sometimes.

Report comment

The_Cat,

Ugh, thank you for sharing your experience… It’s amazing what can be done in the name of ‘for your own good,’ including things that so many of those ‘doing the good’ do themselves (like coping with alcohol)… Somehow, it’s okay to do those things when you’re lucky enough to be perceived as ‘okay’ yourself…

-Sera

Report comment

I did have fun in my class though.

Asking questions like how does a ride in a police car to a psychiatric facility to be strip searched and locked up getting cell phone and cigarettes confiscated and getting forced into nicotine withdrawal for 72 hours in an environment full of violence help a depressed person ???

Report comment

Yeah, I always wondered about throwing someone into nicotine withdrawal during a depressive crisis. For all their yammering about “chemical imbalances,” they don’t appear to understand the first thing about the impact of drug withdrawal. Can’t think of a worse time to force someone to quit smoking against their will!!!

Not to mention those other “minor” trauma…

—- Steve

Report comment

And caffeine withdrawal too. The depressed patients must get worst of that.

We used to call a crisis a nervous breakdown. Anyone that’s ever lived it knows that it’s just that, an overload from trying to solve what seems unsolvable problems and breaking.

I got to think my way out of this, I got to think my way out of this…. I just need a cigarette to get my head straight … I can’t focus. Wow I made a mess of things and I am in a psychiatric facility, I really did it this time. I need a cup of coffee like I have had every morning my entire adult life so I can think… And who is going to feed my cat wile I am stuck in here ? All my numbers are in my phone and its “in the safe”.

NO, line up shut up and at 9:30 you have to fill out some papers then then at your evaluation where we record your reaction to this whole ordeal as “symptoms of the illness”.

Well this post was kind of a fail, but I was trying to explain how the can’t focus part of withdrawal prevents you from coming out of the crisis , nervous breakdown , mania psychosis or what ever. Just a 30 second break from this anxiety and I will snap out of it…

Never again, if a breakup or family death or anything leads me to a hotel room and a week of solo drinking again screw the ER , call my buddies at AA and say dudes sorry I disappeared but I am really screwed up , hang out and help me walk it off.

I realize these places can’t be vacations but my ordeal was a kidnapping and the bill was extortion after I was stuck there a month for refusing to be drugged into Zombie oblivion only to go home and have rebound withdrawals from all that crap ( 2 anti psychotics and an epilepsy mood pill) and be no better off then the day I went in. Zyprexa withdrawal, fool me once shame on you twice shame on me.

Oh and for anyone reading this when they make the standard threat of injection if you refuse your Haldol and other pill lobotomy, they say that to everyone so don’t have massive anxiety over the impending assault with no place to run like I did. They need a court order or for you to react badly.

They came at me with that after I came out of it and was regrouping and feeling better. No longer am I stuck in a hotel going back and forth to the alcohol store, no now I am told have to ingest massive amounts of disabling drugs or they assault pull down my pants like rapists and then stick in a needle !

And detox meds, never got those. Never Again.

Report comment

When I was last “hospitalized” many years ago, taking lots of Thorazine and chain-smoking Kools (1-2 packs a day), I decided to stop smoking, which I successfully did cold-turkey on a locked ward. One of my psych student monitors “advised” me that given the stress level I was dealing with that stopping smoking was not the best use of my energy. I did anyway. And stopped the Thorazine immediately upon being released. Both of theses steps away from dependency would probably have been considered “symptomatic” behavior.

Report comment

Sounds like you had Smoking Withdrawal Disorder and Thorazine Discontinuation Syndrome 🙂

Report comment

Stopping smoking was just one symptom of Sucking Up to Psychiatry syndrome. When I finally realized the game I needed to play to get out — and the (unacknowledged) rules — I announced to someone “watch how straight I can get and how fast.” I also got my hair cut and became president of the “patient government” lol. None of these things were officially acknowledged as having anything to do with my release several weeks later.

Report comment

Steve

Where I work they offer a person a nicotine patch. But then the people go around chewing on the damned things.

Report comment

How very thoughtful of them.

Report comment

Here in Melbourne they cut out smoking in a prison after a short warning period. They too offered patches that people ate then there was a riot. The place was locked down for days, millions of $ damage, but the prisoners took the blame. Talk about stupid! Smoking bans are fine if you can get away from the banned area, they’re cruel oppression if you can’t. It’s bad enough to be shut away without rights but it’s wicked to add avoidable pain.

Report comment

Steve

Since we are a “state” facility the entire “hospital” was forced to go smoke free. Up until about seven years ago people were allowed to smoke. And of course, you can go to the private “hospital” in town and smoke all you want. Smoke breaks are one of the ways that private “hospitals” control people and get compliance with the “program”. If people act up or are not compliant you don’t get to have any smoke breaks that day. Smoke breaks are used as rewards. I was held in a private “hospital” for seventeen days and since I didn’t smoke I asked for a reward different from smoke breaks. They got angry with me and told me that I’d better quit trying to cause trouble for the staff! They told me to get my ass out there with the smokers and enjoy the fresh air and quit causing trouble!

Report comment

Nothing is more trouble than the patients having individual needs they have to deal with!

Kind of disgusting, really. Both making people stop cold turkey, and denying smoke breaks as a punishment for “misbehavior.”

Not sure what else to say. These staff people are the ones who have the mental problems!

Report comment

Sera,

Thanks for an excellent exposé on an important topic. Pharma-psychiatry’s tentacles are everywhere, always masquerading as something helpful and benign.

Report comment

Thank you, Philip, and for your important writing, as well! That disguise (helpful and benign) is indeed what makes it all so deadly…

-Sera

Report comment

As Phil Hickey says> “Pharma-psychiatry’s tentacles are everywhere, always masquerading as something helpful and benign.’ Well Plato said it too:

“This and no other is the root from which a tyrant springs; when he first appears he is a protector.” – Plato

And Martin Luther King Jr: `Nothing in the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.” A succinct version of C.S. Lewis’ “Of all the tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under the omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience…Their very kindness stings with intolerable insult. To be ‘cured’ against one’s will and cured of states that we may not regard as disease is to be put on a level with those who have never reached the age of reason and those who never will’ (C.S. Lewis, 1970

It’s about creating fear of the `other’ by manipulating these ignorant, trusting people in order to increase power and money of the select few.

Report comment

Deeeo42, Thanks for all the great quotes! 🙂

Report comment

Good job Sera. Some of you may know that a group of us with lived experience originally created Emotional CPR as an alternative to MHFA. We now just try to create alternative ways that anyone can help anyone through distress or just communicate to lessen the distress of living in such an oppressive world. We avoid all references to diagnostic or other mental health terms other than saying we hope eCPR will help prevent people being labeled and processed by the system.

Report comment

Dan,

Yes, I actually mentioned eCPR several times to the trainers or whenever I heard people justifying the whole of Mental First Aid for the sake of the ‘compassion’ it claims to be trying to teach….

That said, I’m also concerned with how eCPR has come to be marketed (beyond as a basic tool for first responders, general public and as a counter to Mental Health First Aid)… But you’re right that it is certainly successful at teaching people to seek to connect and present with people who are struggling without all the counterproductive and damaging crap that comes with MHFA!

Sera

Report comment

Thanks so much for this important article Sera. In addition to Emotional CPR (www.emotional-cpr.org) there is also Intentional Peer Support (www.intentionalpeersupport.org). Both teach people to tap in to our humanity and better connect with people in distress, thus avoiding entrapment in the “mental health” system.

Report comment

Thanks, Oryx, and thanks for mentioning Intentional Peer Support (IPS)! Although IPS (in its full t-day training form) focuses on going deeper than perhaps the average citizen might have time or willingness to go, it has been tremendously helpful to us in Western Mass and to so many who are offering peer-to-peer support across the country.

-Sera

Report comment

Can someone give me some details about these types of programs. As far as I know there is little going on in Australia except Hearing Voices as supports for people outside the psychiatric system.

Report comment

deeeo42,

Do you mean Intentional Peer Support and eCPR and so on? What are you looking for, specifically and I’ll see what I can unearth for you 🙂

I know there are, at the very least, some in Australia who have been through Intentional Peer Support training!

-Sera

Report comment

Anything. I have been asked to advocate for people to get them out of the institutions, away from ECT etc but always my stumbling block has been where to send them. Few can walk away and stand alone. People DO have issues, and need often very serious ongoing help and support as do their families. I have looked around for Australian involvement in Mindfreedom, Icarus, Open Dialogue etc but found a small amount of lip service and no action. I need somewhere to send people. I’m old and a bit tired and can’t do it alone.

Report comment

Thanks, Sera. I just finished reading all 70+ comments, in addition to your article. I don’t feel better, yet, but I’ll be ok, after I eat something. “MHFA” is SCARY STUFF. Did you notice that the short-haired, gray-t-shirt student is a *COP*? And, the supposed ‘psychotic” person was a really, REALLY bad actor?

Anyway, I found 2 cartoons today. The first is by “Glasbergen”, and it shows a Doc., talking to the patient:

“We can’t find anything wrong with you, so we’re going to treat you for symptom deficit disorder”…..

In the second, by Streeter, 2 people are talking:

A.”My meds spoke to me this morning”

B.:”What did they say?”

A: The meds aren’t working”.

THANK-YOU, Sera!

(God-DAMN, that MHFA shit scares me!…..

Report comment

I think we need as much humour as we can find. It;s very difficult to be taken seriously when your flies are undone. When the rush is over I’m getting onto it. Short stories, sketch comedy, cartoons, short fims, a TV series set in a mental health institution…come on folks get laughing!

Report comment

Bradford, And scared we should all be! 😉 Thanks for reading and writing, especially the cartoon words… They’re good ones, although I suspect a lot of people would interpret the second one much more differently than most of those of us around these parts!

-Sera

Report comment

FIrst Aid is for general first aid, about what to do before medical help arrives. I see a person in need of assistance, I call emergency services, and it is about what do I do between calling emergency services and emergency services arriving.

Mental Health First Aid to my understanding was started in my own country of Australia, at least 10 years ago. I am truly sorry it has been taken overseas, although pleased to know it only goes for 7 hours. Our courses continue to go for 20+ hours, over 3-4 days. Our courses teach nothing but the DSM criteria for the conditions and the pharmaceutical treatments for them, because they are chemically imbalances in the brain!! While Australia bands drug companies from advertising directly to the public, the names of medications are mentioned in this course, minus the side effects of course. ECT also often gets a mentioned. The testing is on being able to diagnose the person and know what medications they need. The only useful thing said, although I questioned whether it is of any use is that if you see a person in acute distress, assumed to be acutely psychotic or suicidal you should apparently call emergency services, something the average person would already have done anyway.

They claim the success of the course is that on average 60 -70% of people who participate in the course, take themselves to the doctor after realising they have anxiety or depression. Yet before the course they were working full time, raising a family, socialising with friends, etc., etc., without issues!!

The government here will even fund people doing the course and employers training all staff in in, which is not of any use really, because then they wonder why the whole population becomes mentally ill, when we are doing first aid, and then they all suddenly need disability pension and cannot work anymore!

There is absolutely NOTHING first aid about the course, and the most useful thing to teach people in how to be around people in acute distress is de-escalation training, yet no such thing is taught and it is still not taught to anyone working in our mental health services.

Report comment

Belinda,

Wow, Mental Health First Aid in Australia does indeed sound worse than I went through!

And yes, the instructors of my course mentioned at least once that it was an ‘evidence based’ course, and I did want to ask (though ended up forgetting to do so)… But I was kind of suspecting that it probably meant that people were more likely to go into ‘treatment’ or what have you…

Here’s the link to the USA ‘evidence’ page, which seems to mostly be citing Australian studies and does seem to largely be about being more able to identify diagnoses and places to send people off to…

http://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/cs/about/research/

And more from several places around the world here:

http://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/cs/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/MHFA-Research-Summary-UPDATED.pdf

I guess it’s easy enough to prove you are successful when you get to define what ‘success’ is in the first place…

-Sera

Report comment

Success here is termed the number of people who turn up to a mental health clinician. Given the publically funded nature of own health service very easy to know who uses what. The government introduced a policy of GP’s being able to refer people to psychologists, previously the only thing our public health system paid for was medical doctors, medical tests ordered by them and optometrists. Initially it covered up to 18 sessions per year, then it was reduced down to 10, the reason being over 70% of people only accessed one session, which proved how effective they could be!! On the one hand I see hundreds of people going off to psychologists who do not need them, and reducing that is not bad, equally I see people who have gone through really traumatic events and really do need support and are not really being given it.

The Australian government built a whole heap of youth mental health services, there is no evidence of people getting better, just the numbers of people who attended at least once, many of whom never went back again, and others who would have been better if they never did.

As you have said it is very easy to be ‘successful’ when you define what success means, and within Australia it has come to mean people who go to see someone, or diagnose themselves, regardless of the outcomes of that supposed treatment. If I thought the clinical trial data was bad, it has been taken to a whole different level.

Also interesting how common it has now become, it was only 10 years ago, seen as something that 25% of the population would experience in their lifetime, now 25% will experience it every 12 months and everyone will at least once in their lifetime!

I think what angers me more about the mental health first aid is that it is called that. It is now run by standard first aid groups, like red cross and the like!! If they called it mental health education, or the like I would not like it, but it would at least be a more honest description of what it is, although I guess you would not get as many people doing the course then would you!!

Report comment

“They claim the success of the course is that on average 60 -70% of people who participate in the course, take themselves to the doctor after realising they have anxiety or depression. Yet before the course they were working full time, raising a family, socialising with friends, etc., etc., without issues!!”

“The government here will even fund people doing the course and employers training all staff in in, which is not of any use really, because then they wonder why the whole population becomes mentally ill, when we are doing first aid, and then they all suddenly need disability pension and cannot work anymore!”

Belinda, this is so awful, it’s almost funny! People need to wake up and see what we are doing to ourselves. I wish it was unbelievable, but I believe it because I’ve seen this sort of thing over and over again.

“Mental Health” education or “treatment” is often “iatrogenic” meaning that it causes the very issues that it purports to cure. (This happens often in “training analysis, but can be present at any level of the Psych/MH tradition, clearly here in “MH First Aid”).

It’s like a snake oil salesman who poisons people and than cures them of a disease that he actually caused. The biggest problem is that the snake oil hawker is almost always better at infecting people than he is at curing them of that infection!

Report comment

Sera,

I always enjoy reading your posts and savoring your wit and your sharp mind. The MHFA article did not disappoint. Although I have not gone through the training I knew a lot about the original US curriculum that they starting using, e.g., 3 smiley faces next to the recommended ECT intervention (UG, promoting brain damage!!). I don’t know if that is still in the training manual. I see from your blog that MHFA has taken language from Emotional CPR (eCPR) which they have been doing for years and perhaps they have “integrated” others trauma-informed language. Based on your article it appears that the MHFA approach is the same-old-same-old fear-based, linear pathology-think that actually makes the world a less safe and less compassionate place.

Thank you so much for sharing your experience.

Lauren

eCPR Co-founder/Trainer

Report comment

Lauren,

Oy, I don’t know what I would have done with myself if they were promoting ECT in this class… Having no real frame of reference to what it used to be, I can’t really say much about how it’s changed or what it may have integrated in an effort to cover up it’s terrible… but overall… it’s for sure still terrible!!

Thanks for reading and commenting 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

I wish I had time to read all the commentary, but I don’t. Again…Why is starvation ignored? What if the person had not eaten for days? Nothing about eating disorders, apparently….Oh, that doesn’t count? No, ED has to call 911…That “doesn’t count.” Falls between the cracks…AGAIN.

Dear Creators of First Aid, Did you forget about the skinny adolescents? No wonder the kids are dying. I’m not expecting the death toll to get any lower anytime soon at this rate. Or, do you think we are all taken care of at horse farms or busy with fashion mags? Oh, please…….

Report comment

Julie,

Not only did they really not talk about struggles with food at the level to which you’re speaking, but they really didn’t acknowledge the importance of people getting their basic needs (shelter, food, sleep, etc.) met at all… I brought the point up, including how lack of basic needs being met can impact one’s emotional state.. which they didn’t deny, but it certainly doesn’t seem to be a conscious concern of the course itself.

-Sera

Report comment

Wow, I wonder what community this is in? I have seen so much poverty, places where they just can’t afford psychiatry. Sera, I don’t know how old you are, but before 1980, therapy and psychiatry was an “extra,” like nail coverings or hair clips. Something you did in your spare time if you were rich. Very rich. NOT healthcare, and not “required.” No way! Extracurricular. Enrichment or whatever. Then there was this shift. Now that should never have happened. It should have remained always a CHOICE. Shall I paint my nails? I choose. Not.

Report comment

Oh, another thing…..That’s the first thing they ask kids, or should. Do you have enough to eat at home? Or if there’s violence there. Or if it’s clean, and does the family have drinking water and is it warm enough. And if anyone is sick at home.

Report comment

Truth is you do not even need to ask the kids themselves most of the time, parents are more than willing to tell you the information, including the level of neglect they are responsible for, as most of the time they honestly see nothing wrong with what they are doing.

Bruce Perry, is a child psychiatrist, who works in childhood trauma and has published some amazing books, he is not anti psychiatry, but definitely critical of it. He likens the DSM to trying to diagnose a computer problem by listening to the sounds it makes!

His first child psychiatric patient was a 7 year old girl who had been sexually abused by a neighbour and was then found doing the same thing to other children at school. He knew nothing about sexual abuse. He said it was hard to know who was more nervous, the girl or him. He took her into the room, and sat her down and then sat down. She got up, walked across and went and sat on his lap. He thought how cute. Then oh, no. The girl was trying to undo his pants and the like. He immediately got her off, sat her on the floor colouring in, fixed himself up and then coloured in with her for the rest of the session. Immediately afterward he want to get advice from a fully trained psychiatrist, knowing he was out of his depth. Questions, what are the symptoms, not interested in what had occurred, symptoms, not concentrating in class, disrupting, others, etc. Told it sounds like she has ADD, go and look up pharmacological treatments for it and we can talk about it next week. He was shocked. While he knew he knew nothing, he really did not think that Ritalin was quite going to help a child who had been sexually abused and was acting out the behaviour!!!

He has had kids that were being raised in dog cages literally, how was it found out, by asking the parents. The parents had no concerns about what they were doing, in some cases had intellectual disabilities and did not know any better. No one had bothered to ask how the child was living, or anything about the child, let alone go and see the house and what was happening.

The mental health system has a complete inability to see anything other than symptoms of what it considers to be brain diseases, yet they still have no idea of what they are or even if they exist. The do not consider people to be human’s, yet then say people need to have human compassion!

Report comment

Well done Sera,

I mean, how much can a Koala bear? lol Actually a koala is not a bear but ….. how appropriate that they pick an animal which spends it’s days eating eucalyptus leaves and gets off it’s head and sleeps for a mascot.

I’d proudly display a big fail on my wall from such a course if it was marked. They do one in how to identify witches too? lol

Take care and regards

Boans

Report comment

Big Pharma must be desperate for more consumers!

Like Big Tobacco, their customers have a bad habit of dying prematurely.

Report comment

Big Pharma are desperate for money, full stop. How, who cares, why, who knows? Money for money’s sake. The profits made by big pharma could educate the world. Imagine what universal literacy alone could achieve? But it won’t. It needs ignorance, it feeds off superstition and the powerless. Why? To make more money. It’s obscene.

Report comment

Read your account of being trained. Here’s a link to who funds this K street group.

http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/foundation-and-corporate-support

Our Kansas District Representative brags that she has been named a Behavioral Health Champion. Sounds good until you understand that the group is heavily funded by pharma and toots their horn.

Report comment

“They claim the success of the course is that on average 60 -70% of people who participate in the course, take themselves to the doctor after realising they have anxiety or depression. Yet before the course they were working full time, raising a family, socialising with friends, etc., etc., without issues!!” You know why doctors traditionally didn’t want to give people a list of the adverse effects of the medicines they were giving them? Because if they knew about them too many would complain that they HAD them! It’s a variation of the placebo effect. Then there are those who used to be called hypochondriacs, isn’t that a disorder now with a new `scientific’ name. Since the drug companies fund these disease fests, they have probably used some very expensive psychologists to devise a system that encourages people to believe they `have’ something. It disgusts and demoralises me that so many people fall into the trap, then I remember that I did too.

Report comment

I’m very glad to revisit this article & topic. The Director of the local “community mental health center” took this course – “MHFA” – back in April or so, and there was a little story in the local paper. I know this Director personally, and he’s really a nice guy, but he’s drank TOO MUCH Kool-Aid, if ya know what I mean! Funny thing is, he’s been here on MiA, reading about some TRUTHS, too! He’s “conflicted”, as they say. One of my best friends was raped and sexually abused as a young girl, by her Dad, and now as an adult, she’s being forced to take psych drugs. Recently, she was driven to the State loony bin, in handcuffs and shackles, by the Sheriff’s. 3 days later they sent her home in a frickin’ taxi-cab! Her “symptoms” were AKATHISIA. I try to tell this Director guy that he needs to get her off the drugs, and he knows I’m right – but he’s brainwashed. He would talk to her, but he’s the Admin.Director, and not the prescribing M.D.