My story spans all thirty-three years that I’ve been alive. I could not possibly include all the details, so I’ll keep the timeline succinct before appealing for a major change in psychiatry.

I come from a small town in Nova Scotia, Canada where, especially in the early 1990s, there was no such thing as mental health care. I also grew up in a troubled, alcoholic home and from an early age suffered from severe anxiety. And so, when I was 15, my family doctor prescribed me a benzodiazepine: Ativan, twice daily. Not knowing that benzos are tranquilizers, I took it faithfully as prescribed and functioned quite well in high school as a result of my laid-back attitude from the soothing relief the pills provided.

Late in my final year of high school, however, I began to feel sick much of the time, so I stopped taking the Ativan cold turkey. Looking back, I now realize I fell into severe withdrawal, but at the time it was assumed by family and doctors that I had suffered a “nervous breakdown.” My parents were worried I’d take my own life, so I began seeing psychiatrists at the nearest hospital to my hometown, but nothing the doctors suggested could revive me.

The year was now 2001. I was 6’6” and weighed 250lbs, being an avid bodybuilding fan. Yet when 2002 hit, I was down to 187lbs and looked like a skeleton. I slept during the days and stayed up nights by myself so I wouldn’t have to face the criticism of my parents for my current condition. I never left the house and would not let anyone in to see me. I didn’t know what was happening, but I knew it wasn’t my fault. I couldn’t convince anyone of this, however, so isolation from people became my refuge.

Suddenly my health took a sharp turn for the better that same year. I saw my family doctor again, and, similar to in 1998, he prescribed a benzodiazepine (clonazepam) as well as an antidepressant (Celexa). Unlike the treatment from the mental health professionals in hospital, I came back to life immediately: returning to the gym within days of being re-medicated and speaking to friends and family again. In fact, within the next 12 months, I attended university full-time and no one would ever know by looking at me that I had been through a prescription drug addiction and withdrawal.

On clonazepam I soared, making the Dean’s List in all fours years of university, graduating with first-class honours, and receiving a full scholarship to graduate school. I was also fully dedicated to weightlifting again.

Just before graduation in 2007, though, I experienced my first trauma flashback stemming from childhood. It scared me, but I was already seeing a university counselor and taking my “medications,” so I didn’t think much of it at the time or worry about the future. I knew I was a great student, so I assumed there would always be a career for me in academics.

After moving to Toronto to attend graduate school is when I fully fell apart. I began seeing “big city” doctors in Toronto who diagnosed me with Major Depression and General Anxiety, but nothing changed from the care my family doctor provided; it was still just frequent antidepressant changes and daily doses of benzos. When I would bring up family issues, I’d just have the option to choose another antidepressant, as no doctor had the time to sit down and talk about my feelings or thoughts; they only wanted to know my symptoms. They’d refer me to a counselor for all my personal issues.

I grew sicker and weaker over the next two years until I was unrecognizable to myself: having fits, in constant pain, insomnia, internal bleeding, digestion issues, derealization and panic attacks on top of the stress of grad school and my family imploding. I began checking myself into any emergency room in the city that offered psychiatric care, pleading for help. Not once were the benzodiazepines pointed to as something that could be hurting me after (at this time) 11 years of use.

In 2009, I decided to commit suicide: sitting on the edge of my bed with a knife in one hand and a bottle of benzos in the other, my plan was to swallow the remainder of the pills and then, when I was dozing off into unconsciousness, cut my throat. But something unexpected happened: when I loaded the benzos into my mouth, they started to melt! I panicked. It was no longer my decision when I cut my throat. I was suddenly on the clock due to the rapidly dissolving tranquilizers in my mouth. It was now or never. I chose never, spitting the pills all over my room. Crying uncontrollably, I called a cab to take me to another emergency room, but I knew this time I’d not be coming home for a while.

Starting in 2009 and into 2010, I spent 10 months in four different hospitals. In each hospital, I was ripped off benzos in days only to be given a fresh prescription when leaving inpatient care after I failed to get better. I realize now that no treatment or therapy in any hospital would have worked, as I was in severe withdrawal and kindling from the benzos. Yet doctors saw it as a personal failure on my part: why did I not want to get better? The fourth and final cold turkey attempt resulted in doctors suggesting electroconvulsive therapy, as I was clearly beyond modern psychiatric help.

I woke up too soon from my first ECT session: I regained consciousness, heard the doctors and nurses talking, knew I was being moved, yet I couldn’t speak or breathe because the muscle relaxers had yet to wear off while the anesthesia clearly had. I was a living corpse at that moment. Thus, for the following 16 rounds of ECT, I pleaded with my anesthesiologist to kill me. I hoped to never wake up again rather than experience another ECT session. To think about how I was crying out for help, but couldn’t move, speak or breathe, is a nightmare I’ll never outgrow. Further, it’s the perfect metaphor for the next two years of my life navigating the public mental health system.

Upon hospital discharge I was given a public psychiatrist who had zero time for me from the get-go. He looked at my hospital charts, saw the ECT sessions and the grocery list of pills I’d tried and asked me why I wasn’t getting better. It was my fault: why did I resist treatment in the past? Why was I so stubborn in dealing with doctors? Why was I against medication? Why did I not want to get better? I’ve heard it all.

Yet, this time — after being broken by ECT — I wholly gave in to psychiatry. I accepted all the pills. My family couldn’t help; they told me to stop resisting treatment despite the horror stories I told. Within months, I was on eight medications: 1) Effexor for depression, 2) Clonazepam for anxiety, 3) Wellbutrin to help the Effexor, 4) Zopiclone for sleep, 5) Synthroid just in case my thyroid was out of whack, 6) Lithium because, by now, it was just assumed I was bipolar as well, 7) Seroquel because, if I was bipolar, well, why not at this point? And 8) Lamotrigine because one ER doctor said it was a “miracle pill.” To top it all off, I was prescribed psychodynamic therapy twice a week.

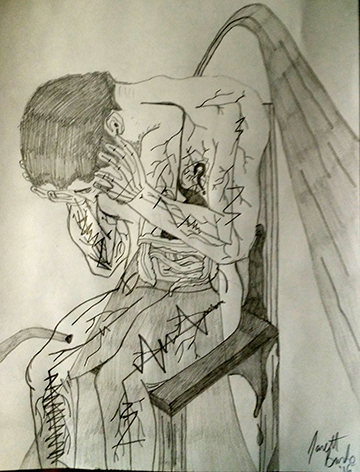

After eight pills and twice-weekly psychodynamic therapy, I simply gave up. Knowing I’d not commit suicide, I settled for cutting myself… and it felt amazing. In fact, it felt so good that it became my therapy of choice over the next two years (2011-12), and I stopped trying to get help from the public mental health system. I had no money, no place to stay, no food, nothing. Cutting was the least of my worries, and it made me feel better, so I did it. I knew I was getting a surge of dopamine each time I cut myself, so I reasoned that if this were the only way to stop the pain I would do it to stay alive. I quit psychiatry because I was getting better help from a steak knife.

During this time free from doctors, I tried to make use of my education, gain employment and just be myself, but I could still barely function despite the cutting. I’d find a job and then lose it; I’d get Social Assistance, find another job, and then eventually lose them both. I did, however, manage to wean myself off of Effexor, Wellburtin, Synthroid, Lithium and Zopiclone while staying with friends.

As each drug came out of my system, I functioned slightly better. At one point in 2012, I was in low-income housing and working two part-time jobs. I was binge eating, cutting and eating Seroquel like they were candy, but I was functional enough so that the public mental health system and provincial government could stop caring about me entirely. I was 29 and this sure wasn’t how I’d pictured my life turning out.

In 2012, I discovered Buddhist meditation and teachings. The one good thing to come out of my 2010 hospitalization was a free mindfulness meditation course based on Jon Kabot-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction work. During my first body scan I knew there was something to mindfulness, yet it wasn’t until I discovered the Buddhist teachings that life became slightly more manageable. I soon discovered that I was a basically good human being simply by existing. There was nothing wrong with me after all. I was just anxious, but so is everyone in modern society. What a revelation! I knew I was trying hard all these years. Deep down, I knew I was working my butt off just to stay alive, yet I’d never get any credit for my work from doctors or family.

Despite reading Buddhist texts and meditating regularly, I was still unable to hold down full-time work. I always crashed due to the enormous amount of energy it took to perform the self-care I needed away from the job. At this time, I was a client of a group that helped people with disabilities secure and hold employment. This group offered to fund 12 sessions with a private psychologist to help ensure future employment. That’s the day my life started to turn around for the better. Having never been able to afford private care before, I jumped at the opportunity.

After one session, the doctor told me she knew what was wrong, but wanted to wait one more session to confirm. After the second session she told me that I had Complex PTSD.

I was blown away. I cried, I laughed, I raged, I found hope again. I’ve always suggested to past doctors that I may have PTSD, but they would only scoff, get irritated and hand me the DSM IV, which clearly stated that I needed to have suffered a near fatal event in order to have PTSD. Where was my Vietnam? Where was my car crash? No, to them I was just looking for attention, and they’d follow that by telling me to let them do their job. However, in 2013 an updated DSM5 included Childhood Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Complex PTSD, so maybe I should have been doing their job after all?

Here’s how my psychologist cured my PTSD: she listened to me, first and foremost. Here’s why psychiatrists would never cure my PTSD: they’d ask for my symptoms, and only my symptoms. Next, they’d walk across the room, look in the DSM IV and tell me I have _________ (based on whatever diagnosis cross-referenced with my symptoms that day, which changed often).

I’ve seen people put more research into how to cook a turkey at Christmas time than previous psychiatrists did for my health. From the DSM to the prescription pad, if it wasn’t there, it didn’t exist. It’s a very cut-and-dry, mix-and-match method to modern medicine that has harmed millions of people, and it nearly killed me.

Instead, through a Cognitive Behavioral/Exposure Therapy model, I was working full-time within one year. I’m still shocked at how quick my turnaround was. I survived PTSD and was proud of myself. My physical symptoms never went away though. I was in pain all the time, mainly headaches. Also, I still couldn’t sleep without benzos and Seroquel. My stomach kept giving me more and more problems; it was no longer bleeding, but it was always bloated and extended. I was having visual problems and was very sensitive to light and sound. But I was content and happy to live like this forever, if need be.

Having taken on too much responsibility with a full-time supervisory position, plus being in my first relationship in seven years, my physical symptoms kept getting worse until I started to regress mentally. Once again, I sought out a psychiatrist because my psychologist couldn’t help me with the physical pain. The first thing to come from seeing a new psychiatrist was Prozac, and it helped the pain for about a month. Along with the Prozac, I also started EMDR therapy, and Wellbutrin soon followed; so, in my mind, I was going the wrong way again: too many similarities to the days of eight medications and psychodynamic therapy. Critically, the new psychiatrist never said that benzos were harming me either; in fact, she increased my dosage. Fortunately and unfortunately, though, she’d soon never give me another pill again as she moved to another province and left me with no follow-up care.

At this point, I was spiraling downward again due to physical pain and regressing mental health. I lost my job and my relationship. Then I had to rely on the government again for food and shelter. Even without the stressors of the job and relationship, though, I kept getting physically sicker and weaker. I’d have trouble just walking to the grocery store and back. I’d be in bed, not from depression, but because I just couldn’t muster the strength to stand up anymore. I was fading fast and there was nothing my psychologist could do.

Yet, she did the most important thing imaginable: she believed my theory that the benzos were killing me, and she offered to see me for free when I no longer had money. Basically, she listened, again, and she saved my life, again.

It took exactly one year to find a new psychiatrist. When I found one, I wasn’t excited; instead I was terrified, having zero trust left for anyone with a prescription pad. Yet he listened to my horrible past and agreed that the benzos were destroying my life. After having doctors say I’d be on benzos for the rest of my life, here was one saying I needed to get off of them or I’d never be healthy again. I reasoned that after dealing with roughly seven years of PTSD, I’d kick these pills no problem. I was wrong.

About five months into my taper, I lost the ability to walk any further than the bathroom and back with any reliability. With three months to go until my final pill, I began experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms: burning nerve pain in my spine, brain and limbs; sickening nausea so bad I wanted to die; insomnia; extreme depersonalization to the point where I questioned what was real; my sense perceptions were all off and, of course, I had no energy. This lasted for 12 months. I’d have a few hours of relief every three or four days, but for the most part, I had to be in bed with pillows over my head to block out all light and sound. I lay in bed wanting to die, daily.

It’s been 14 months since my last benzodiazepine. At the 9-month mark, I was able to walk consistently again and the pain and nausea started to lessen. I’m about 50% healed now. I still struggle mightily with the withdrawal (perhaps brain injury is a better term at this point). But I’m myself once more, even with the physical pain and sickness. I’ve returned to a creative life that gives me purpose, meditating daily, eating well, and working part-time so I can afford food, while hoping to exercise soon.

I’ve had my life ruined by trauma and pills, yet there are days when I’m happier than any time I can remember in over a decade. I’ve found an unshakable faith in myself through this journey. And now that I’m almost in the clear of psychiatric medications (I have Prozac left to taper) and I can trust my mind and feel that I know myself, I’m convinced that I’m on this planet to help others find the same kind of peace.

I want to share my story of recovery with the world to ensure that everyone currently suffering knows that they are worthy of help, support, treatment and love. I offer hope as one person in the fight toward a global shift in the way society thinks and treats people with mental illnesses.

What needs to change in psychiatry? It’s simple: doctors need to listen to their patients and treat them as individuals rather than as a puzzle piece to be slotted into a diagnosis. Of course, doctors know more about the body and brain than I do, but I know more about my body and brain than any doctor.

I truly believe that if doctors just listened a little more to their patients, suggested lifestyle changes first (like diet, exercise and mindfulness), and only took out the prescription pad after the conversation was over, there would be a lot less mentally ill and chemically dependent people in society. Also, as a doctor, allow yourself to think outside the box, as the current box (psychiatry’s model of care) is dangerously broken. As a doctor, you’re most likely intelligent, so use said intelligence instead of mindlessly following what’s been done before that clearly doesn’t work.

The overprescription of psychiatric drugs ruins lives. There’s no longer any doubt. Thus, be part of the solution and not part of the problem by treating patients as individuals. It’s the least anyone deserves who’s seeking help. No matter how overworked or burnt out a doctor is, he/she can always take a nap to recover, or even quit the profession altogether. Patients don’t have that option. Once hooked on psychotropic drugs, we remain hooked until we either find a rare, life-saving doctor who listens — or we die.

Jarett,

I’m glad to hear you survived your gruesome journey. Can you imagine if you’d met a decent “counsellor” at the start and how much grief that would have been saved.

I reckon at least half of all the “Severe Mentally Ill” population – could make full recovery with suitable non drug help.

I’ve had very similar life experience myself (but with Neuroleptics as the offenders ) and over the years my anxiety has come right down.

My solutions were in staying away from the services funded by taxpayer – because these are the ones that make a person sick!

It’s great to hear your story!

Report comment

Thank you Fiachra!

I often think what would have become of me if I was allowed to talk to a professional before being medicated. My life would surely have been radically different. But, I’m here now, so I’m going to make the most of it

Life is a strange, strange path. I’m looking forward to 2017 though. Hopefully I continue to make strides in my recovery and I can help others do the same.

Report comment

Thanks Jarett,

You are helping people!

Report comment

“I quit psychiatry because I was getting better help from a steak knife.”

This sentence is one of the best commentaries on psychiatry that I’ve ever read. I believe that the prescription pads need to be taken away from psychiatrists because, when it comes right down to it, they don’t know what in the hell they’re doing! Everyone knows that benzos are only supposed to be used for a very short time and here they had you on the damned things for over 11 years! What was done to you is criminal and it’s really too bad that, at this point in time, psychiatrists can’t be brought to trial and put in jail or prison for what they did to you. Thank goodness you woke up, despite their drugging, and decided that you know what is best for yourself. Congratulations for pulling yourself out of all this. Thanks for sharing your story.

Report comment

17 years, all told! Thank you for the kind words Stephen. I also like the steak knife commentary. It’s a shocking image that (hopefully) will affect the reader. Thanks for reading.

Report comment

“I quit psychiatry because I was getting better help from a steak knife.”

I loved the line too.

Report comment

A brilliant piece of work. Full of humanity and hope. I wish you well as you continue your journey toward health.

I agree that psychiatrists need more than a fifteen minute session to get a feel for their patients. But where is the money in that?

Report comment

Hi Stephen,

I think psychiatrists do know what they are doing but most engage in what I call deliberate ignorance.

Jarett, I was completely speechless after reading your story. I swear, everytime I think things can’t be any worse, someone like you sadly proves how wrong I am.

Kudos to you for what you have accomplished in spite of going through hell.

Report comment

Thank you for taking the time to comment, AA. Much appreciated.

Report comment

Thank you Randall. I truly appreciate it.

Get ya in and get ya out! Then submit the bill to the government. What a mess…

Report comment

Jarrett,

Thanks for sharing your story, it’s similar to many of ours, a tale of psychiatrists not listening, not believing, and in my case, after several years my psychiatrist finally did listen to me, and he declared my entire life a “credible fictional story.” Of course, I had to leave him then.

And the medical evidence has come in showing that the primary actual function of today’s psychiatric industry is denying and covering up child abuse, just as happened in your case, and mine.

I do so hope the psychiatric industry will soon get out of the business of profiteering off of defaming, poisoning, torturing, and killing child abuse victims and their concerned parents. Personally I believe our society should go back to arresting the child molesters instead. I’m glad you survived to tell your story. Thank you for sharing it.

Report comment

Thank you Someone Else. It just takes one doctor to listen, if my story suggests anything. I hope you don’t give up searching. I know it’s a disheartening, deadening process, so I wish you well!

Report comment

Jarrett, loved your story. Similar to mine. Keen to hear how you are getting on. Best wishes,

Greg

Report comment

The ignorance about the effects of benzodiazepines and other psychiatric drugs on the body and psyche is utterly appalling and outright dangerous.

Having been on Klonopin for ten years, I understand the harrowing hell and complex journey you must have been through (and are going through) and how we’re only getting glimpses of it here.

While I’ve not had ECT, there were times when I felt desperate enough and thought nothing else would work, so I requested it. I’ve requested ECT several times, but always while I was maxed out on Klonopin at 8mg a day and 7 other psychiatric drugs. Fortunately, my medicators haven’t practiced it and have told me that they’d need to refer me out for that “service.” Well, thanks for that! was my thought. So, I understand when you write, “I pleaded with my anesthesiologist to kill me.” In a way, I was pleading with my medicator to killl me.

Over the past ten years I was iatrogenically dependent on benzos, mainly Klonopin, taking as prescribed, and having a myriad of issues that I thought had nothing to do with benzo use, but now I realize have everything to do with bezno use. I have the reports and tests to prove it. I have reports from cardiologists, gastroenterologists, neurologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, optometrists and so on. I have had all kinds of MRIs, X-Rays, blood work, genetic testing. All of them are within normal limits except the psychiatrists! Of course, when I would get back negative results, I thought: well, okay, good, but, am I going mad? Madder?? Now, it’s empowering information! Unfortunately, the other medical health providers failed to pick up on the psychiatric drugs as being a leading factor for my symptoms–if they did, they didn’t express detectable concern.

Congratulations on getting this far on reclaiming your narrative and your life from psychiatry and from mental health–not an easy task!!

Report comment

Thank you kindly! Yes, us Benzo Warriors could probably paper our walls with negative test results telling us that we’re fine. Just about a month ago I had an EKG done and the doctor told me I am a very health young man. I laughed out loud at how absurd that comment was, but – on paper – it’s true!

Wishing you all the best in your recovery.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your story Jarret. Every time someone is brave and transparent and puts their story out there, I believe it has the potential to save someone else from a similar plight. Congratulations on your freedom and wishing you continued healing.

I’m not sure if Mad in America wrote this part of your bio: “17-year prescription drug addiction to benzodiazepines.” or if you did, but I would implore either of you to change it for accuracy to “iatrogenic dependence” or “prescribed physical dependence”.

Report comment

Hi Cole,

Sorry if I chose the wrong wording for harm caused by benzos. I’m not up on the lingo, but I did change it in my bio. It was my wording, not MIA’s. My mother died from her addiction to alcohol and was also badly damaged by benzos, so I’ve always identified with the term “addict” as I’ve seen my own addictive behaviours throughout the past 17 years eerily mirror that of my mother’s.

Hope you are well.

Report comment

Jarret,

Your story is a heartbreaker but congratulations on coming through with flying colors. You are an amazing guy! If you don’t already know about her, you might like Monica Cassani’s website beyondmeds.com. Her experience has been a lot like yours.

Mary Newton

Report comment

Thank you, Mary. I will be sure to check it out. I truly appreciate the kind words!

Take care

Report comment

Hi Jarett,

Well done on speaking out about all this publicly; that takes a lot of courage. And glad to hear you are feeling better now; you surely deserve that.

Beyond the drugging, another aspect of your story stood out to me – the misleading effects of being diagnosed with so many different labels. Like so many people it sounds like you were brainwashed to believe your distressing experience represented “disorders you had”, rather than primarily understandable reactions to your own complicated individual experiences over time. When one doesn’t know any better and has professionals in white coats telling one that one’s distress is caused by one’s “bipolar” or by one’s “major depression”, the inversion of cause and effect that appears so frequently in psychiatric logic, and its divorce from the context of a person’s life, may not be immediately apparent.

In other words psychiatrists brainwash many people into believing that “the disorders” magically cause the distress in isolation, rather than interaction between the individual and the environment over time leading to distress. Thus the decontextualists (i.e. the psychiatrists) make it more difficult to think of distress as logical and understandable responses to what has happened in one’s life, and more difficult to believe one can take action to change one’s circumstances for the better.

It’s good to hear you were able to start thinking for yourself more and trust your own sense of the right path to take. That is what so many psychiatrists do not allow, by paternalistically labeling suffering and pressuring people into numbing “treatments”, rather than by listening to them and giving them real choices.

I felt this section below provided a good example of how what psychiatrists tell people often warps their minds:

“I was blown away. I cried, I laughed, I raged, I found hope again. I’ve always suggested to past doctors that I may have PTSD, but they would only scoff, get irritated and hand me the DSM IV, which clearly stated that I needed to have suffered a near fatal event in order to have PTSD. Where was my Vietnam? Where was my car crash? No, to them I was just looking for attention, and they’d follow that by telling me to let them do their job. However, in 2013 an updated DSM5 included Childhood Post-Traumatic Disorder or Complex PTSD, so maybe I should have been doing their job after all?”

There is no recognition by the professionals that these “disorders” lack validity and do not truly exist as discrete entities. In the black and white world of psychiatry, subjectively-observed disjunctive criteria are enough to “have” or “not have” a supposed disorder, and thus to spin the bottle for this or that pill, with barely any regard for the social context or life story of the person involved. It is truly amazing to see how little understanding some psychiatrists have that distress occurs along a continuum/spectrum with adverse social experiences being one of the major contributors to most reports of distress – and this applies not just to “PTSD” (another artificially delineated and questionable concept, as if PTSD were clearly separable from other DSM diagnoses), but also to more severe distress often (mis)labeled as bipolar.

Ultimately psychiatrists fail to realize that our complex human genomes did not evolve to reify or confirm fabricated DSM diagnoses, which are simply labels made up by old white men sitting in boardrooms.

If you haven’t heard of him, you might also like the writing of Colin Ross – http://www.rossinst.com/about_dr_colin_ross.html – such as his book the Trauma Model, A Solution to the Problem of Comorbidity. It explains why separate psychiatric disorders do not really exist as 0s or 1s that has one either has or doesn’t have, but that emotional-social problems and biological correlates are matters of degree over time.

Lastly you might also like this article by John Read on the future or lack thereof of psychiatry, if you haven’t already seen it: http://www.future-science.com/doi/pdf/10.4155/fsoa-2015-0011

Thank you again for speaking out Jarett; we need more people like you doing that.

p.s. While I focused on the weaknesses of diagnosis – one of my favorite topics – I did hear the immense suffering caused by the drugging. I was on over 10 drugs myself, although I didn’t have as difficult a time coming off. And my father was on many different psych drugs and was harmed by both them and ECT. So yes, the side effects (and psychological effects) of these drugs can be very nasty, and lead one further and further away from being able to do the things that can really lead to wellbeing. Again glad you are working past that. Once one has some momentum, is getting off drugs, and no longer believes the lie that one has lifelong brain disorders, getting well is not impossibly difficult.

Report comment

Thank you Jarrett for being braver than I at this point on multiple levels. Kudos!

To you and Matt regarding DSM conniving.

According to. DSM workshop I went to back in the day it wasn’t in boardrooms but basement rec rooms and kitchens. Though boardrooms were there always as invisible guests. The doc leading the workshop called what it was and is hanky pi

This was known but somehow scrubbed out of general medical knowledge.

Report comment

Sorry for the typos again!

Report comment

You’re welcome CatNight. Bravery will come when you’re ready. I’ve been wanting to tell my story for years, but I just couldn’t… for some reason. So, I guess the time is just right now. I’ve also tried to force bravery, and it never worked out well. Patience leads to bravery.

Take care!

Report comment

Wow. Great post Matt. Thank you so much for the information and links. I will look into them.

I’ve been beaten to death by the DSM. At one point or another in my journey, I’ve been diagnosed with Major Depression, Manic Depression, G.A.D., Bipolar, as someone with borderline personality disorder and an addiction, and I’ve been seen in early psychosis units. Also, my anxiety was so bad as a child doctors thought for a brief time I had tourrettes. I’m telling you, if diagnoses were worth anything, I’d be a millionaire.

Hope you are well!

Report comment

Haha that is true Jarett – if diagnoses were also worth anything I’d also have a lot of cash. On the other hand as we both know it is not really a laughing matter to be given one of these “serious mental illness” diagnoses.

Regarding Borderline Personality Disorder, please read my story about recovering from problems associated with that label –

https://bpdtransformation.wordpress.com/2015/03/26/24-how-i-triumphed-over-borderline-personality-disorder/

Btw I checked out your personal Wix and see you are helping other people be more encouraged – well done! It is very rewarding to help people.

You might also be interested to check out groups such as ISEPP (www.psychintegrity.org), which includes some psychiatric survivors. About early psychosis, you might like ISPS (www.isps.org), as well as my article rejecting the validity of schizophrenia: https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/09/rejecting-the-medications-for-schizophrenia-narrative-a-survivors-response-to-pies-and-whitaker/

Sorry for trumpeting myself here. I want to encourage you that there are quite a few other psych survivors speaking out publicly about the ways they found to get better deeply and holistically (as opposed to “I’ve got a lifelong brain disease and have to take my meds to manage it”), and in so doing encouraging others. It took me a long time to get to the point of speaking out publicly, due to fear of stigma, job loss, etc. But I’m glad I did it and commend you on doing the same.

Report comment

Encourage away, sir! I appreciate all the links and knowledge.

I never actually HAD any of those diagnosis, by the way. My only diagnosis is (and has been) benzo withdrawal, then came PTSD much later. Looking back on the past 17 years, it’s insane how easily I’ve been diagnosed and treated for anything but withdrawal and trauma. Healing from both withdrawal and trauma are very time consuming projects, so public psychiatrists do not have the time to treat them, therefore they don’t acknowledge them. That’s been my experience, anyway.

I was using my personal blog to start writing again after being afraid to do so for a long time. I’ll keep practicing there and try to help MIA in the future if they need a hand.

Report comment

Courageous truth-speaking from the voice of lived experience, thank you Jarett. Psychiatry is a train wreck, no doubt, and tragic. Congratulations on finding your way to clarity and for taking action in the direction of your well-being, based on your own self-knowledge and wisdom.

“I’m convinced that I’m on this planet to help others find the same kind of peace.”

Inner peace is, indeed, a gift we can share lovingly with others. Very best wishes on your noble mission, and your continued healing.

Report comment

Thank you so much for the kind words, Alex.

At some point during the withdrawal, I decided that the only way I’d survive was if I started to live for others (even with the minimal strength I had). If I was only living for myself, I don’t think I would have kept going as my life (and Me, myself) had lost all meaning and value. I am working on rebuilding that lost meaning/value for myself as I help others.

Take care

Report comment

Sorry you went through that nightmare, Jarrett. No one should have to experience that torture. With the following exceptions:

Dr. Torrey

Tim Murphy

Dr. Ronald Pies

Pete Earley (might promote emotional bonding between him and Kevin)

Dr. Lieberman

Report comment

Thank you. I’m not sure who those people are, but I’m guessing they’re doctors working with Pharma?

Report comment

The five horsemen of the psychiatric apocalypse 🙂 Ignorance is bliss.

Although I have a feeling the comment by FeelinDiscouraged is going to get into trouble with the moderator when they see it…

Report comment

Guess it wasn’t. Hee hee.

😀

Report comment

I met a friend at the weekend who had upped his tranquilisers due to government induced stress (he is being transferred from one benefit to another).

He has a physical health condition that causes him chronic pain and takes pain killers for that.

I wonder whether the benzos are contributing to his pain levels and general bad health?

Apart from that this article just confirms to me that psychiatry needs to end. It is the drug delivery agent for Big Pharma and it tries to make sure no one thinks about why someone is distressed.

Report comment

I hope your friend is coping, John. He/she may want to check out the online support group Benzo Buddies and get engaged in conversation with others to see if his/her symptoms could be benzo related.

Report comment

It could also be from the chronic use of opiates. You can reach tolerance on those and they cause rebound pain (much in the same way that benzo tolerance causes worsening anxiety even though they’re prescribed as so-called “anxiolytics” for anxiety). I’ve conversed w many folks who actually had less pain once they tapered off of their chronic prescribed use of opiates.

Report comment

John,

I’m sorry about your friend.

If the UK wants people on their feet, then they’d need to do something about the “mental health’ approach, because there’s nothing as disabling as being switched off by neuroleptics. When I was on a ‘maintenance dose’ I wasn’t very productive.

The last person I met on neuroleptics had been working sucessfully as an engineer – and now he spends the day watching television.

Report comment

Sad!

Report comment

Jarett, it was a pleasure to read that. Thank you for writing it, as another survivor of ECT and the whole psychiatric system.

Chris

Report comment

You’re welcome Chris. I’m glad you survived and hopefully you’ve healed by now (or are in the process). Psychiatry can be a monstrous system where trusting people are chewed up and spit out. I’m worried about the future and my friends’ kids. So, I want to do my part and caution against “the system.”

Take care.

Report comment

Wonderful article Jarett. I never had the benzo issue but certainly had every anti-depressant thrown at me and plenty of anti=psychotics. I actually found, for myself, that those “medications” increased my impulsiveness, never decreased my “depression” and gave me a host of other physical problems. I also got the wrong diagnosis and my complex PTSD was ignored entirely by the prescription profiteers (for over 3 decades). I am off all of the garbage two years now, except for a sleeping pill that I have accepted I may never be able to break it off with, and my life and overall health have improved so much I am astonished. Could it be the medications actually make one sicker than they ever imagined they could be? Psychiatry isn’t even symptom management anymore as much as it is illness maintenance! By sharing your story you help shed light on the long term consequences of pill pushing.

I found your story so inspirational and your courage and strength inspiring! I am glad you are still among us.

And, as I am planning on Moving to NS, what’s it like there? lol

Report comment

There is no medication for Complex PTSD, so a typical psychiatrist just sedates and medicates. Everyone I meet who has PTSD I recommend they see a psychologist or even a counsellor of some sort to get all the darkness out and bring in some light. Talk therapy is a miracle if done right. I’ve made more progress in healing my PTSD in one therapy session involving a huge, sobbing cry than any pill could possible do for me. I’m sorry you spent so long seeking help only to have the root cause ignored. You’re tough!

In my experience, anti-psychotics and ADs make me jittery and uncomfortable. So, I’d agree that for people like you and I, they only make us worse. I’m very excited to begin my Prozac taper in the new year. I’ll be free as a bird sometime next year.

Well, Nova Scotia is wonderful if you like the outdoors. Halifax is really the only city. The rest is mostly small towns and communities. We used to get lots of snow, but not so much anymore. Summers are starting to get REAL hot too. Spring is rainy and cold, but Fall is perfect (and my favourite). It’s very clean and people are friendly. It’s ‘home’ to me, so there’s no other place I’d rather be, really. Hope your move goes smoothly!

Report comment

Jarett

A truly inspiring story of someone who has been able to climb out of the Hell of the current “mental health” system and then speak out with such a powerful voice. I hope you continue to educate yourself about the criminal nature of Biological Psychiatry and use your story to educate others.

I have a couple of questions and additional comments: How much were you influenced in your recovery by the emerging movement against psychiatric abuse – such as websites like MIA and other critical writers, including psychiatric survivors?

Have you considered the long term effects of benzo dependency causing a condition similar to what happens with long term opiate use, that is, “Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia.” The long term use of these drugs actually makes a person more sensitive to pain, thus lowering their pain/frustration tolerance level. I believe that benzos may also cause a similar type reaction in the body due to its disturbance and overall down regulation of Gaba receptors.

On the issue of language, especially calling psychiatric drugs “medications.” Remember the use of the term, “medications,” is a “System” term that is the strategic result of literally billions of dollars of advertising by Big Pharma in collusion with Biological Psychiatry. True medications in the field of medicine address human disease processes or other cellular anomalies in the body. Psychological distress of a severe nature is NOT a disease. Even “post traumatic stress” is a real reaction to our conflict with our environment and we should probably make it a point to leave off the “disorder” part to not reconcile with “System” language and all their DSM diagnoses. Psychiatric “drugs” are exactly that: mind altering drugs, and I believe it is very important for us to use this scientifically more accurate language to counter the false narrative promoted by Biological Psychiatry.

Sometimes mind altering “drugs” can play a positive role for some people, especially in the short term. So by countering the “System” narrative (by not using the term “medications”) we are not necessarily promoting and “anti-drug” position. Food for thought.

Once again, great blog! I hope you write more in the future.

Richard

Report comment

Thank you Richard. My first insight into psychiatric abuse came through mind.org.uk. I was in the hospital in 2010 and somehow I came across their guide to coming off psych meds and what caught my eye was the severe warnings they gave the reader. Also, in that same year, my pharmacy started labelling benzos as a narcotic, so I put two and two together. Unfortunately, it was a long, long time until I could taper properly.

I keep up with mainstream news articles about the overprescription epidemic, and I follow MIA regularly, but that’s only been within the last 6 months or so. I rented Whitaker’s “Anatomy” from my library right before I began tapering Klonopin, but I was unable to read it as I got very sick, very fast. So, all told, I’m quite new to the world of psychiatrist abuse outside of my own experience. During my taper and much of the withdrawal I could’t read.

I didn’t have to consider the benzo equivalent of “Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia” as I lived it for years. My threshold for pain was low, as was my threshold for stress. It still is and I’m 15 months off the pills. I believe it’s as real as any other side effect from benzos.

The fact that I called them “medications” was supposed to be a jab at psych drugs because I put it in quotation marks. I agree. They are drugs. No doubt.

Hope you are well! Thanks for commenting. I appreciate it.

Report comment

We have very similar stories. However, I am off my cocktail that included Klonopin now for going on 4 yrs. The healing will keep on coming. We are the lucky ones in this unlucky lot and we have our whole lives ahead of us. Congrats. Well done,

Sonja

Report comment

Thanks for giving me hope, Sonja. It’s still very hard, but I know I’m healing, so I just have to be content to wait it out.

Report comment

Glad you survived and thanks for sharing your story! I have a similar story and have managed to get off all psychiatric medicine myself: http://www.optimallivingdynamics.com/about/

Fixing my blood-brain barrier really helped me: http://www.optimallivingdynamics.com/blog/how-to-repair-a-leaky-blood-brain-barrier-ways-heal-fix-supplements-mental-health-neuroinflammation-treatments-causes-gaba-injury-hyperpermeability

Cheers,

Jordan

Report comment

Thanks Jordan,

I’m glad you are recovering. I’m actually really interested in the blood/brain barrier as many, many people in my benzo withdrawal support group swear by it. I’ll use the link you gave me to find out more. Much appreciated!

Report comment

ECT breeches the blood brain barrier, leaving devastation in its wake. You attribute most of your damages to trauma, toxic psych drugs, and withdrawal. How did ECT affect you? What “type” did you have?

Report comment

Bi-lateral. I honestly don’t even remember that time of my life. I know I had 17 treatments. That’s about it. I wanted to die before, during and after my entire ECT experiment, so I’m convinced all my suffering was benzo related.

Report comment

Jarett wrote:

“Psychiatry can be a monstrous system where trusting people are chewed up and spit out.”

Jarett,

Kudos and brownie points to you for recognizing the worst and most neglected evil of the whole psychiatric system: the abuse of vulnerable people’s trust by powerful and well educated professionals. It compares unfavorably to priests’ sexual abuse of children. Children can grow up and escape their tormentors. Victims of psychiatry too often remain stunted and dependent until their too-early deaths, crippled by their faith in the god-like suits and heels who are paid so handsomely to stigmatize and drug them for life.

So keep up the good work toward the day when we have a Pope Francis of Psychiatry who recognizes what’s going on and acts accordingly. How about going back to school and applying for the job yourself?

Best regards,

Mary Newton

Report comment

I loved this comment! Thanks Mary. I’d love to go back to school and become a doctor, but I’m afraid that costs a small fortune now-a-days. I had to go bankrupt during my illness, so I’ll never be able to borrow money again as I’m looked at as ‘financial cancer” to anyone in a suit. I think I’d make a great psychiatrist/psychologist too.

Step 1 is healing. Who knows what will happen in the future?

All the best!

Report comment

I’ve dealt with the “we’ll have you committed” nonsense when I wasn’t even delusional. I got manic though so I think that didn’t see it because was high on a good mood. I was psychotic during my last mania so my time to get off these drugs will come. I don’t get enough to abuse of anything I take. I want off though.

Report comment

I admire your bravery, courage, and strength: you never give up hope. That reminds me of me. I always in the end find some hope to keep me going. I go through dark periods then I reorient myself for hope again. You inspire me. I shall write my story one day soon. I could write it here, or write it and send it to MIA.

This ebook inspired me recently. Beat Depression and Anxiety by Changing Your Brain, by Debbie Hampton. She took an overdose of pills because of chronic depression and ended up with severe brain damage. She could hardly walk or talk but she learnt about neuroplasticity and epigenetics and how the brain can repair itself. So she got into exercise as best she could, and mindfulness meditation. She got interests and hobbies going and over the next two years she made a full recovery. She worked for it, and we can do the same.

All the best, and thank you you your inspiring article. It really moved me.

Report comment

I’m glad to have inspired you. And I’d love to read your story someday. Also, thank you very much for the book recommendation. I got the ebook this morning and I’m half-way through it. Very helpful and easy to read. I’ve tried to read “The Brain That Changes Itself” by Norman Doidge but I’m still having trouble reading and understanding what I read.

All the best

Report comment

Hi Jarrett,

Debbie Hampton has a blog which looks interesting.

http://reset.me/story/neuroplasticity-the-10-fundamentals-of-rewiring-your-brain/

Report comment

Very interesting. Mindfulness is one of the main tools i use to deal with my hallucinations and delusional thoughts.

And yes, the withdrawals from psych meds are often mistaken for psychotic symptoms.

Report comment

Jarett, what a remarkable story I know all to well. I was mis-diagnosed Bi-polar 40 years ago and poly-drugged for 35 of them. The drugs destroyed my life, and that of my children. When the iatrogenic illness set in Doctor’s didn’t know what to do, so it was off to ECT’s. So fast forward 35 years and everyone of my Mental Healthcare workers informed me it was ‘just fine’ to cold turkey off all five of my current meds. They never informed me of one single withdrawal symptom I may experience, nor did they believe me when I began telling them weekly how strange and bizarre I was feeling. And I was refused access to my psychiatrist when I began losing contact with reality as I once knew it. They said, “Sandy, you just have to wait until your upcoming appointment a month away.” I told them I couldn’t wait that long. They didn’t care. They pretty much left me to die at home, alone. I also lived in Klonopin ‘interdose withdrawals’ for eight years that totally crippled me before my cold-turkey Klonopin withdrawal that threw me into the pits of Hell. It warms my heart to read a ‘success’ story of someone who was able to gain an education and proceed in life. The drugs did too much cognitive damage for me it would be impossible to even think about going to college, let alone try to help mankind in fighting Psychiatry & Big Pharma. But I sure am happy you did. Thank you….

Sandra Villarreal

Report comment

That’s very kind of you to say, Sandra! Just hang in there and let the brain’s natural healing occur. I truly hope you are doing alright. Be good to yourself.

Report comment

I hardly detailed my story as much as you did. But I do appreciate that you went into so much detail. Hopefully, you’ll read my article “Waking Up Is Hard To Do” and get a good idea of my history. Both of ours are tragic, and unfortunate. Your story made me feel a bit better about the brain torturing hardship I went through just this morning, going off a milligram of Stelazine, an antipsychotic I’ve been taking for about two and a half years. I’m still on two mgs of Klonopin, (which I hope to taper off using “Tapering Strips.” Have you heard of them? There was on article about them on the MIA site about 6 weeks ago. I’m also on 325mg of Lamicdal. I would welcome the opportunity to maybe speak with you on the phone, if you’re open to it. I am not connected with others who are going off or have gone off drugs and would love ti share thoughts with you.

Report comment

I’m just musing how the psychiatric system, including the insurance companies, and everyone who is paid for whatever work they do that is related to the mental health system, for or against, is in someway profiting from the human suffering, no matter the cause.

Jarrett, thank you for articulating your journey of suffering and perseverance. Thank you for shining your light and love.

Report comment

I hope you see this Jarett! You popped up in my dream last night lol! We were all at a Halloween party. That part isn’t important, but today it brought me to your incredible story. I hope you’re doing well! Thank you for sharing your story with the world, I know this will help a lot of people and inspire many.

Report comment