In late February, newspapers in the UK and elsewhere announced that a new meta-analysis published in Lancet had proven, once and for all, that “antidepressants work.” The lead author of the paper, Andrea Cipriani, and other psychiatrists from the Royal College of Psychiatry in the UK, declared that this was a definitive study, and that any debate over the drugs was now over. This led at least a few newspapers to dust off their Prozac headlines from 25 years ago and declare that “Happy Pills” were here again.

Joanna Moncrieff and others have written detailed critiques of that study. Their most important point is that this meta-analysis relied on an outcome measure that inflates the perceived efficacy of the drug. Otherwise, the study provided little that was new. Previous meta-analyses of the literature for antidepressants had found that their effect size was small to moderate over the short term, with these results mostly coming from industry-funded trials, and the Cipriani study, when carefully parsed, found the same thing.

Unfortunately, it is the “antidepressants work” soundbite that will remain in the public mind and not the critique. And here’s the problem: there is a need for the public to know the many types of evidence that bear on this question of whether antidepressants “work.” Psychiatry relies on a particular slice of evidence—RCTs in a carefully selected group of patients—to support its “antidepressants work” message. But a review of the evidence regarding their effectiveness in real-world patients, over both the short term and long term, tells a different story, and this is precisely the evidence most germane to patients.

Personally, I think the question—do antidepressants work—is a poor way to frame this debate. Some people respond well to antidepressants, some do so-so on the drugs, and others worsen. Furthermore, this spectrum of outcomes occurs in comparison to natural recovery rates, which also need to be fleshed out. Thus, the challenge is to review the evidence in a way that best illuminates the risk-versus-benefit equation for individual patients. That is what is necessary for informed consent, which is fundamental to the practice of ethical medicine.

There are three parts to the review that follows:

- The evidence for the efficacy of antidepressants over the short term in RCTs, which is the evidence that psychiatry relies on to claim that the drugs “work.”

- The evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants over the short term in “real-world” patients.

- The evidence regarding their long-term effectiveness in real-world patients.

This broader review of the research literature does then lead to a dichotomous question for society. Do antidepressants, as they are being prescribed now, “work” for society? Do they produce a public health benefit?

Efficacy of antidepressants in RCTs

As Moncrieff noted in her critique, meta-analyses of RCTs assessing the short-term efficacy of antidepressants may give a skewed view of the drugs, simply because the RCTs are fraught with problems. Most of the studies are industry-funded; investigator bias is a worry; the placebo group is composed of patients who have been abruptly withdrawn from their drugs, which isn’t a true placebo group at all; negative results go unpublished; and the studies are conducted in a small subset of patients who could be expected to best respond to a drug. All of these shortcomings with the RCT literature bias outcomes in favor of the antidepressants.

Even so, the evidence of antidepressant efficacy that emerges from RCTs is, at best, a modest sort.

Symptom reduction scores

Irving Kirsch and his collaborators, in their meta-analyses of industry-funded RCTs, have reported that the difference in symptom reduction between the medicated and placebo groups is less than two points on the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (HAM-D). The National Institute of Clinical Excellence in the UK has stated that there needs to be at least a 3-point difference on this scale to be clinically relevant, and Kirsch found that it was only in a subset of patients, those severely depressed, that SSRIs met this standard.

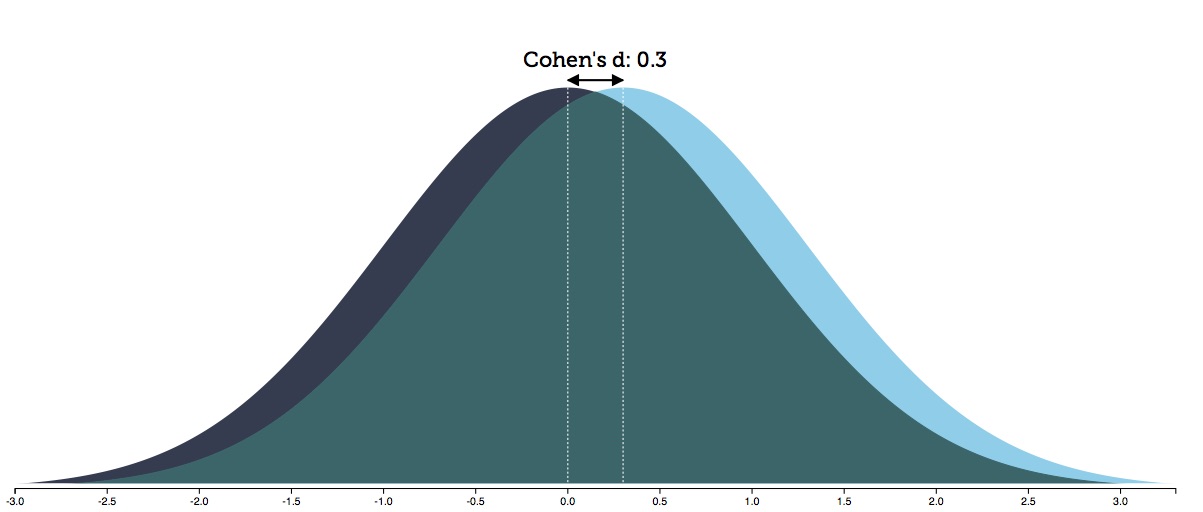

Kirsch and others have calculated “effect sizes” of around .30 for antidepressants based on symptom scores. As is shown by the graph below, this means that there is an 88% overlap in the distribution of outcomes for the drug-treated and placebo patients.

Given the placebo response rate in these trials, an effect size of .30 produces an NNT—number needed to treat—of 8. This means you need to treat 8 people to produce one additional person who benefits from the treatment, as compared to placebo.

Thus, the risk benefit equation from this symptom-reduction data can be summed up in this manner: Is exposure to the adverse effects of drug treatment worth the 12% chance of a better outcome? Or to put it another way: 12% of patients will benefit from the treatment, while the remaining 88% will suffer the adverse effects of treatment without any additional therapeutic benefit beyond placebo. Those are the odds that a person contemplating taking an antidepressant drug might want to know.

Response rates (at eight weeks)

In their Lancet study, Cipriani and colleagues relied on “response rates” to assess the efficacy of antidepressants. Response was defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms. The researchers then calculated the “odds ratios” for the response rates in the two groups, which tells of a relative efficacy. How much more likely is it that patients in one group will be responders compared to patients in the second group? Cipriani reported that the “odds ratios” favored the antidepressant over placebo in every case, with the “ORs” ranging from 1.37 for the least effective antidepressant, and 2.13 for the most effective one.

Kirsch and Moncrieff, as well as others, have noted that using response rates as a measurement inflates the perceived efficacy of the drug, and it is easy to understand why. A patient who has a 52% reduction in symptoms on the HAM-D will be classified as a responder, while a patient who has a 48% reduction in symptoms will be classified as a non-responder, even though there is no real difference in improvement between the two. As a result, a slight difference in HAM-D scores between drug and placebo groups may show up as notably increasing the likelihood that a person will “respond” to the drug treatment.

Unfortunately, Cipriani and colleagues didn’t report the response rates that were used to calculate the odds ratios, which is the very information that the public would like to know. Do 25% of people “respond” to antidepressants? Fifty percent? Seventy-five percent? There is no way to answer such questions from the odds ratios alone. Thus, the very study being touted as proving that “antidepressants work” fails to give any information about what percentage of people “respond” to the medication.

However, other meta-analyses of RCTs of antidepressants have reported mean placebo response rates of around 37% for the placebo group and 60% for the antidepressant group, which fits with the overall odds ratios published by Cipriani. In terms of the risks and benefits of taking an antidepressant, this outcome can be interpreted in this way:

- Thirty-seven percent of patients would respond without treatment, and thus treatment exposes them to the adverse effects of antidepressants without any additional benefit. As such, they could be said, on balance, to have been harmed by the treatment.

- Forty percent of patients will be non-responders to the treatment, and yet will be exposed to the adverse effects of antidepressants. They too could be said, on balance, to have been harmed by the treatment.

- Twenty-three percent of patients will be responders to the treatment who otherwise would be non-responders. This is the group that could be said to have been helped by the treatment.

In sum, in terms of assessing risks versus benefits based on response rates, 77% of all patients will be exposed to the adverse effects of the drug while receiving no extra therapeutic benefit. Only 23% will experience a therapeutic “response” that they otherwise wouldn’t have had. This produces an NNT of 4, and while this is twice as good as the NNT calculation based on the symptom scores, it still leaves three out of four patients experiencing the adverse effects of antidepressants without any benefit beyond placebo.

Both of these methods of assessing efficacy in RCTs—symptom reduction and response rates—provide evidence that, in statistical terms, “antidepressants work.” But it is easy to see that in terms of evaluating the risks-versus-benefits for the individual patient, they provide no such certainty.

Short-term effectiveness in “real-world” patients

As Cipriani and colleagues noted, industry-funded RCTS are conducted in a select set of depressed patients—those without comorbidities or suicidal thoughts. In essence, the pharmaceutical companies use eligibility criteria to select a group most likely to respond well to the drug. Only about 10% to 30% of real-world depressed patients meet these criteria.

With this thought in mind, John Rush, a prominent psychiatrist at the University of Texas Southwestern, conducted a study in 2004 of the effectiveness of antidepressants in 118 real-world patients. Effectiveness describes outcomes in real-world settings, as opposed to the drug “efficacy” that is measured in RCTs, and thus this is the outcome data that would be most relevant to patients.

The patients in Rush’s study, who were seen in an outpatient setting, were given the best clinical care possible. Yet only 19% had responded to the treatment at three months, which was one-third the response rate recorded in RCTs.

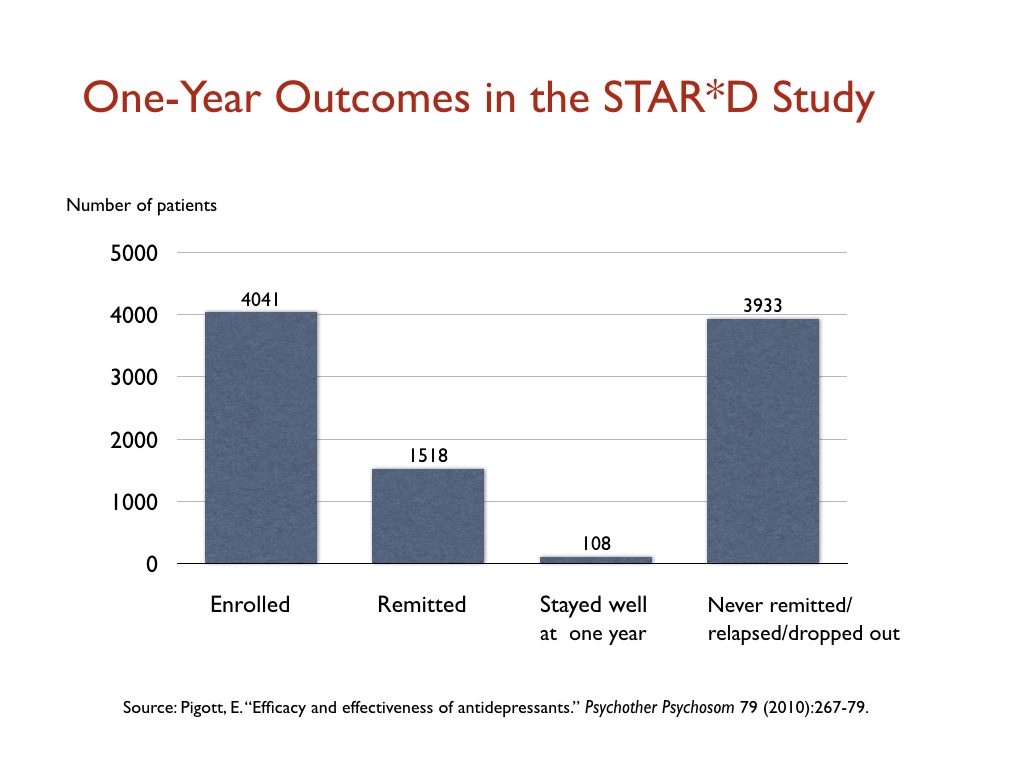

Rush was also a lead investigator in the NIMH’s STAR*D study. This was hailed as the largest antidepressant study ever, and it too was meant to assess the effectiveness of antidepressants in real-world patients, most of whom were only mildly to moderately ill. Moreover, the study had a design that could be expected to produce a higher response rate than usual in an RCT. Patients who didn’t respond to a first round of treatment could then have a second round with a different antidepressant, and so on through four courses of treatment. The idea was that eventually a treatment would be found that would work, with patients given multiple chances to register a HAM-D score of seven or below. Yet, even with this design, only 38% of the 4041 patients reached this level of improvement.

These real-world response rates reported by Rush raise an obvious question: Are they better than “natural recovery” rates over the short term? I am not sure there is a good answer to that question in the research literature, but what can be concluded from these two studies is that there is a lack of evidence that antidepressants are effective in the majority of real-world patients, even over the short term. They “work” in only a minority of patients, and it may be that they don’t provide any benefit over natural recovery rates at the end of 6 to 12 weeks.

Long-term effectiveness in real-world patients

Remission rates

The goal for people who are depressed is to get well and stay well. In research terms, patients want to experience a “sustained remission.”

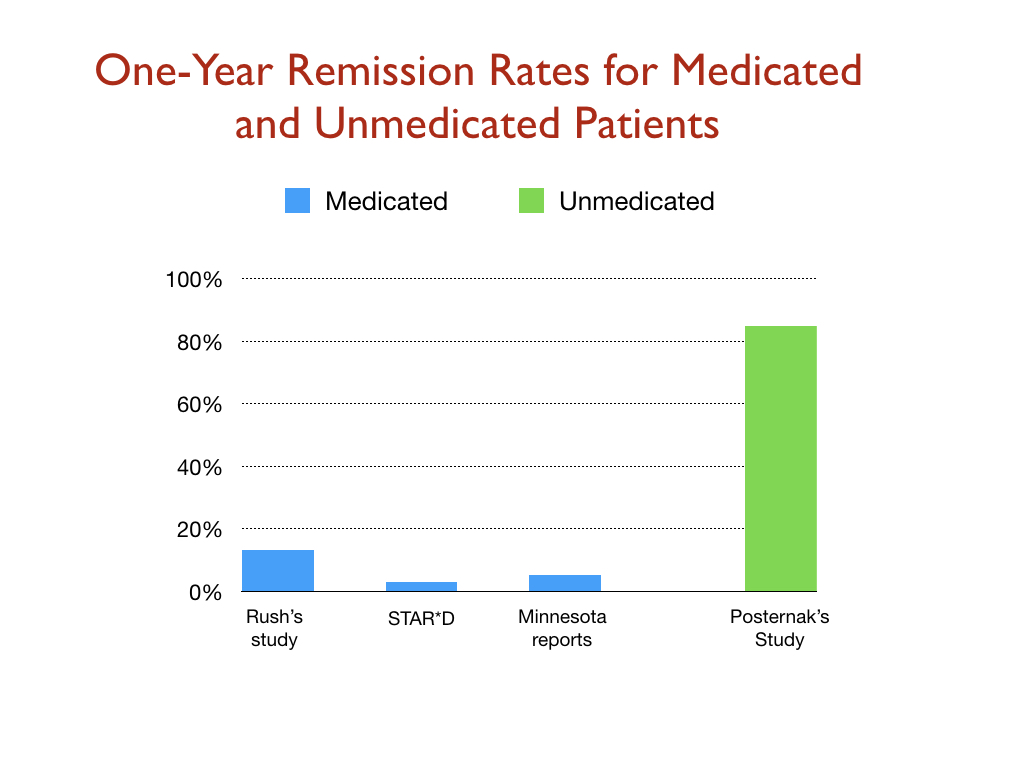

In Rush’s study of 118 real-world patients, 13% were in remission at the end of the year, but only 5% had a “sustained remission” during the year. The outcomes in his study, Rush confessed, “reveal remarkably low response and remission rates.”

The documented stay-well rate in the STAR*D trial was even worse. At the end of one year, only 108 of the 4041 patients (3%) had remitted and stayed well and in the trial. All of the others had either failed to remit, relapsed, or dropped out of the study.

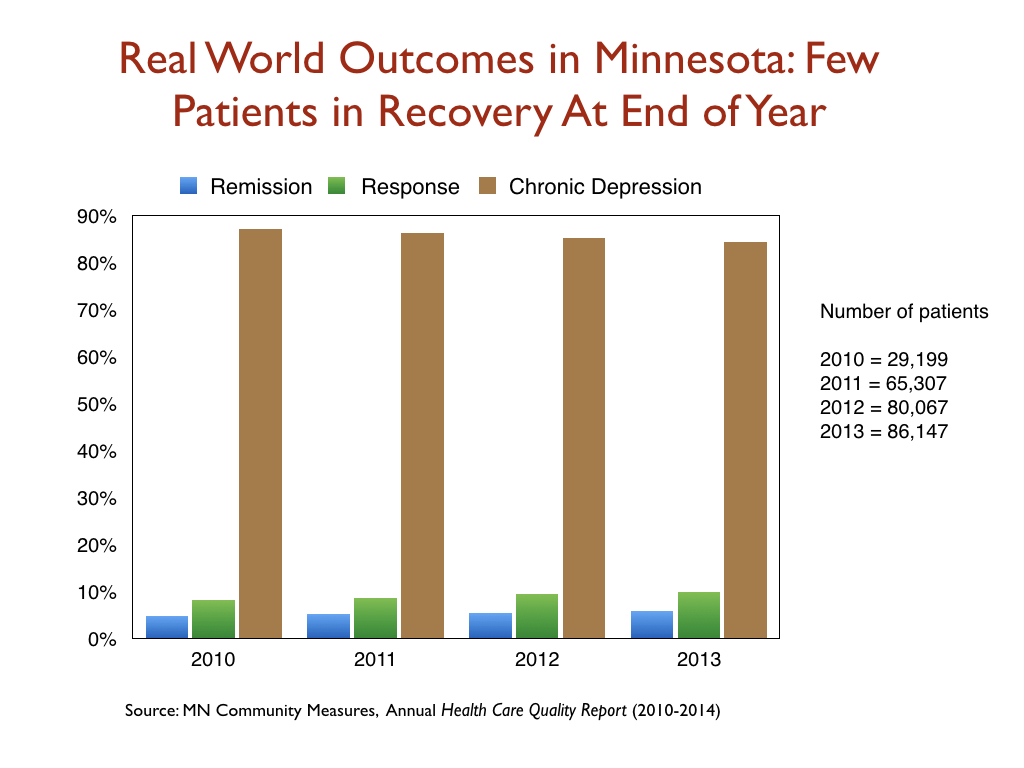

A Minnesota report on the real-world outcomes of 260,000 patients treated for depression from 2010 to 2013 found similarly low remission rates. At the end of each year, only about 5% of the patients were in remission. Another 10 percent or so were still considered responders to antidepressant treatment. The remaining 85% were categorized as chronically depressed.

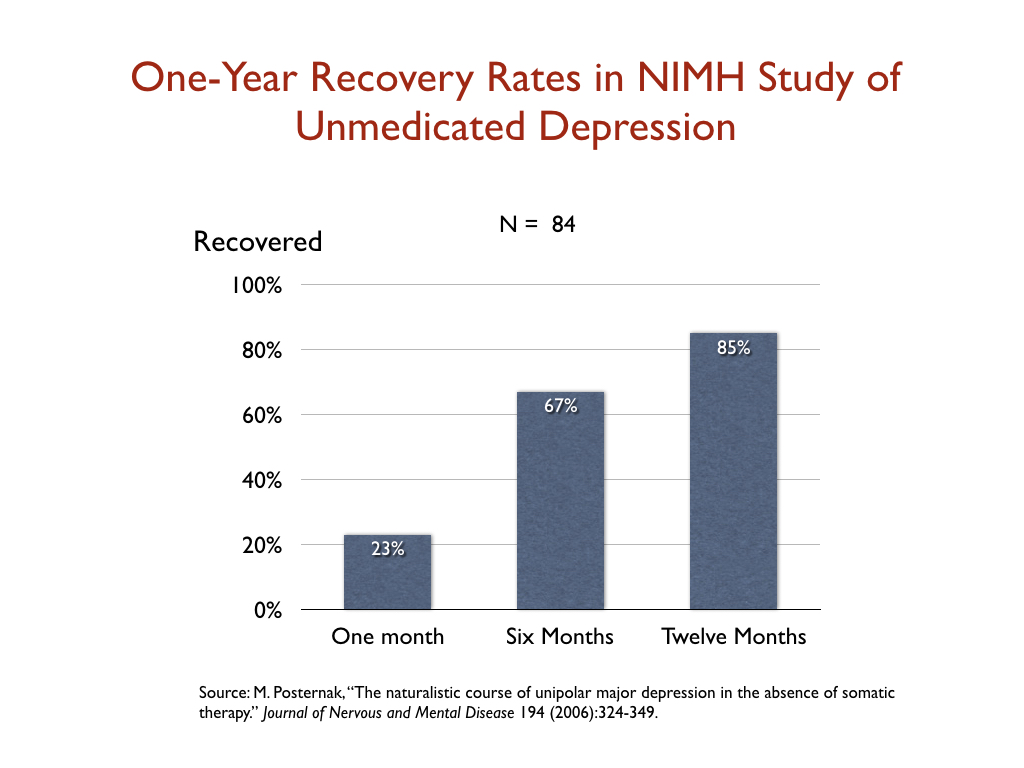

In 2006, Michael Posternak, a psychiatrist at Brown University, studied the one-year remission rate for unmedicated patients. To do his research, he identified 84 patients enrolled in an NIMH study who, after recovering from an initial bout of depression, subsequently relapsed but then did not go back on an antidepressant. He tracked their remission rate over time: 23% percent had recovered by the end of the first month; 67 percent at the end of six months; and 85% at the end of one year.

Posternak summed up his results in this way: “If as many as 85% of depressed individuals who go without somatic treatment spontaneously recover within one year, it would be extremely difficult for any intervention to demonstrate a superior result to this.”

Now it is possible that these various “effectiveness” studies, for one reason or another, assessed recovery rates in patient cohorts that were quite different. Even so, it is notable that the one-year outcomes for the medicated and unmedicated groups in these studies were the polar opposite of each other: 85% of the medicated patients were chronically depressed, while 85% of the unmedicated patients were in remission. As the graphic below shows, this comparison demands further investigation.

Naturalistic studies of unmedicated v. medicated depression

There have been a handful of naturalistic studies during the SSRI era that have compared longer term outcomes for patients who chose to take antidepressants and those who did not, with these studies helping to flesh out the evidence regarding the “effectiveness” of these drugs in real-world patients. Specifically:

- In a 1997 study of outpatients at a large inner-city clinic in the UK, 95 never-treated patients saw their symptoms decrease by 62 percent in six months, whereas the 53 medicated patients experienced only a 33 percent reduction in symptoms. The medicated patients “continued to have depressive symptoms throughout the six months,” the investigators reported.

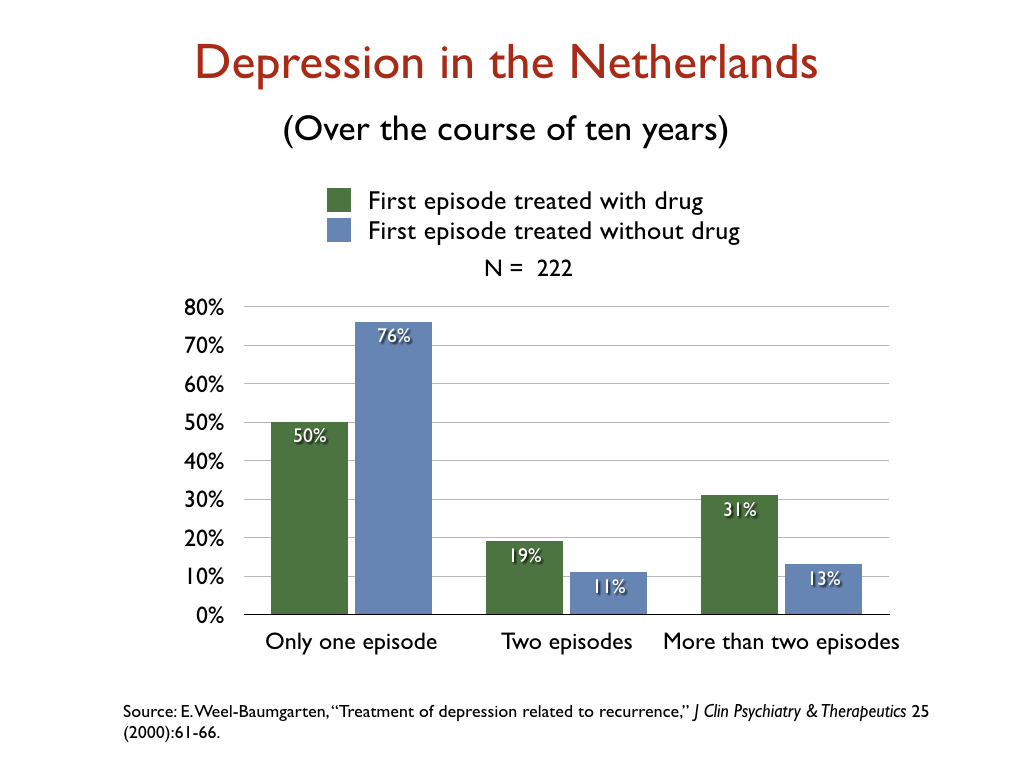

- In a retrospective study of the 10-year outcomes of 222 people who had suffered a first episode of depression, Dutch researchers reported that 76% of those not treated with an antidepressant recovered and never relapsed, versus 50% of those initially prescribed an antidepressant.

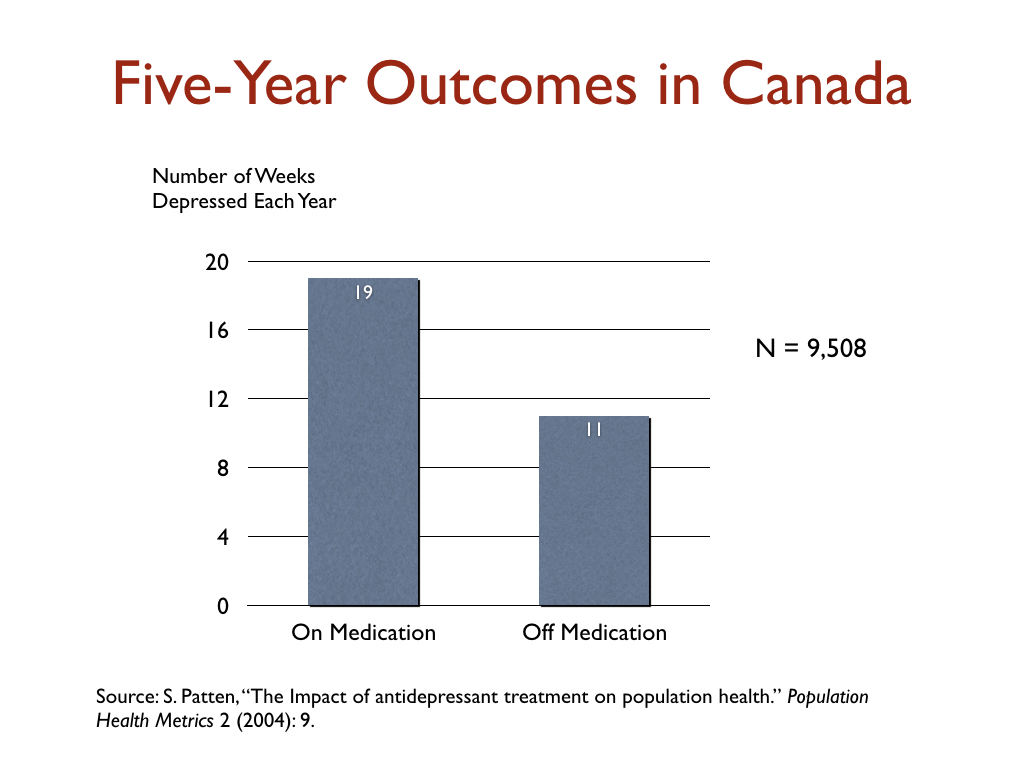

- In a Canadian study that charted outcomes for 9,508 depressed patients for five years, those taking antidepressants were depressed on average 19 weeks per year, versus 11 weeks for those not taking antidepressants.

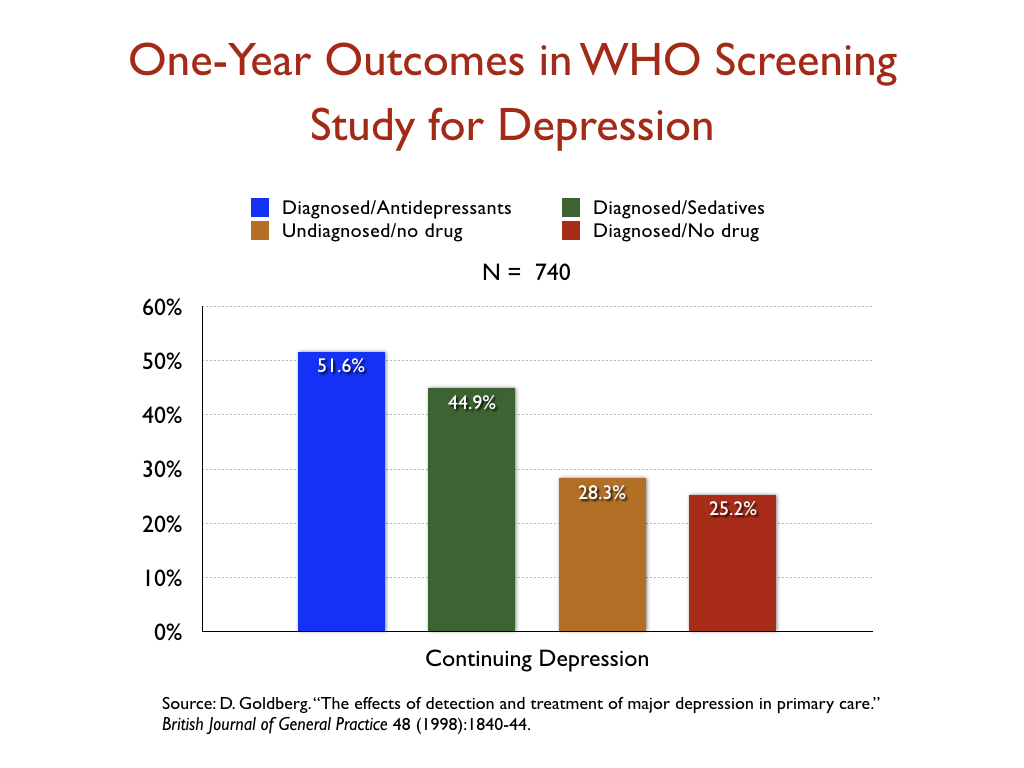

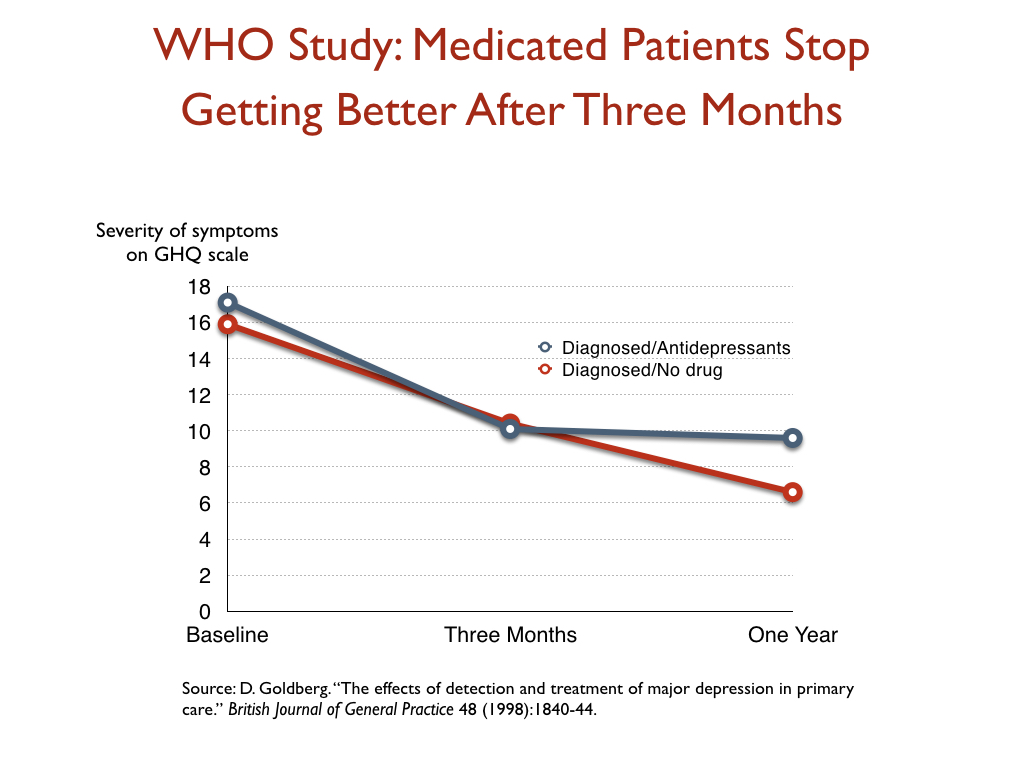

- In a World Health Organization study designed to assess the merits of screening for depression, which was conducted in 15 cities around the world, the patients who were diagnosed by their GPs and treated with an antidepressant were twice as likely to be depressed at the end of one year as those who weren’t diagnosed and treated, even though their baseline depression scores were nearly the same.

This WHO study also provided some insight into the effectiveness of antidepressants—or their lack of effectiveness—over time. At the end of three months, the patients treated with medications had improved slightly more than the unmedicated group, but after that time they stopped getting better, while the unmedicated group continued to improve throughout the year.

Disability studies

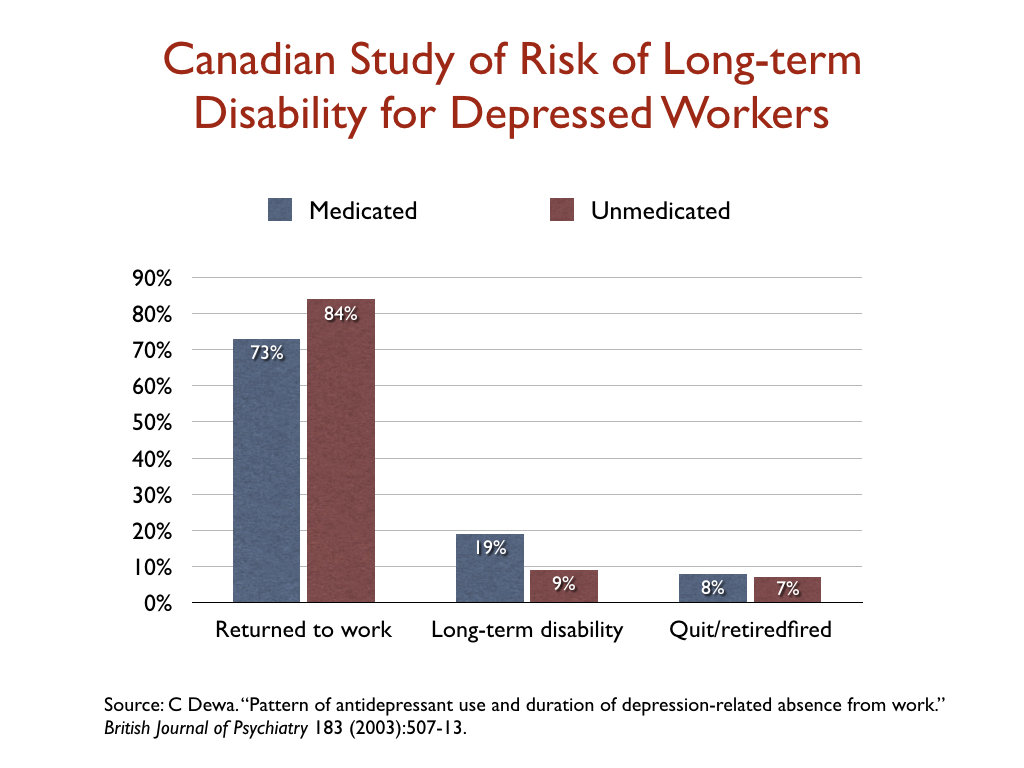

While most studies of depression focus on reduction of symptoms, a few researchers have looked at whether antidepressant use affects disability rates. In a study of 1,281 people who went on short-term disability in Canada due to depression, 19% of those who took an antidepressant failed to return to work and went on long-term disability, compared to 9% of those who didn’t fill a prescription.

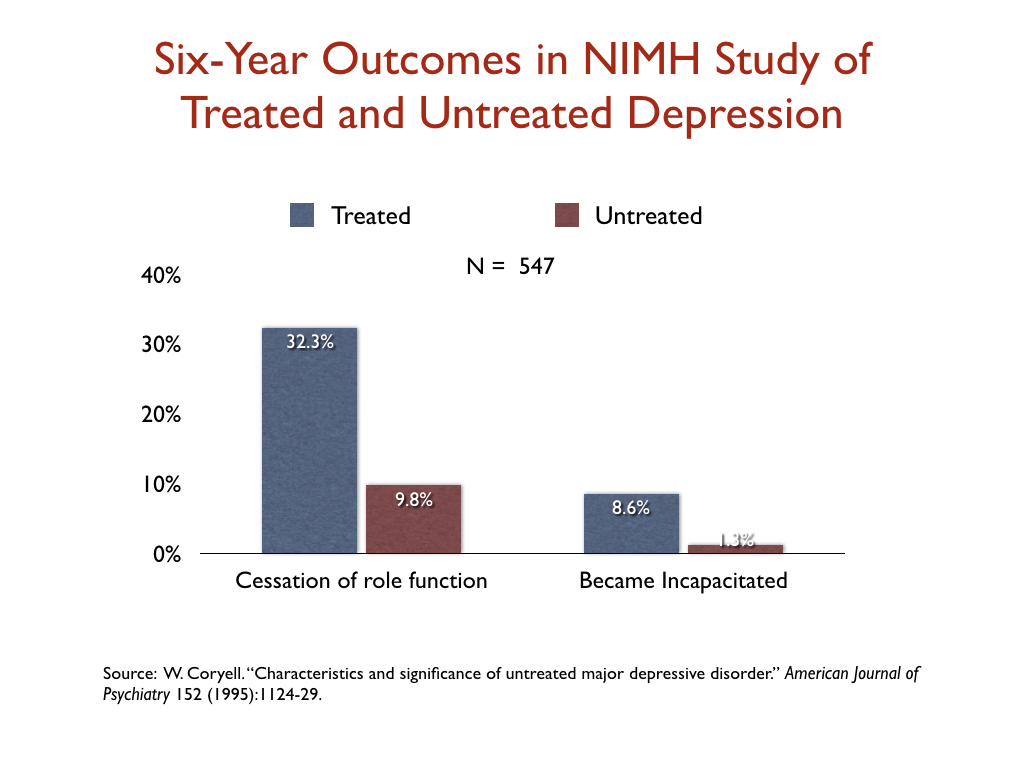

In a similar vein, an NIMH-funded study assessed the six-year “naturalistic” outcomes of 547 people who suffered a bout of depression, and found that those who were treated for the illness were three times more likely than the untreated group to suffer a “cessation” of their principal social role, and nearly seven times more likely to become incapacitated.

Summing up the people’s evidence

When psychiatry states that “antidepressants work,” the profession is telling of efficacy findings that emerge from RCTs, which are conducted in a small subset of real-world patients, and are fraught with design problems that favor the drug. Even so, the effect size favoring antidepressants is small, with an NNT of eight based on symptom scores.

In real-world populations, response and remission rates are lower, and they are particularly poor at the end of one year. Medication appears to provide few people with a sustained benefit, and there is substantial evidence that natural recovery rates are much higher. Medication also increases the risk that a person will become disabled by the disorder.

In addition, antidepressants may cause a wide range of adverse effects, which have not been listed here. This review of outcomes in real-world patient has focused on the “benefit” side of the question to assess whether antidepressants can be said to “work,” and even without subtracting the many risks from the benefits, the effectiveness studies provide reason for people to think twice before starting an antidepressant. The studies regularly tell of a treatment that increases the likelihood that patients will become chronically depressed.

Do antidepressants work for society?

The question of whether antidepressants “work” for society is different in kind than whether the drugs “work” for patients. The societal question requires a review of public health data: Does the treatment lead to a lessening of the societal burden from the disorder? Do antidepressants have this effect on depression?

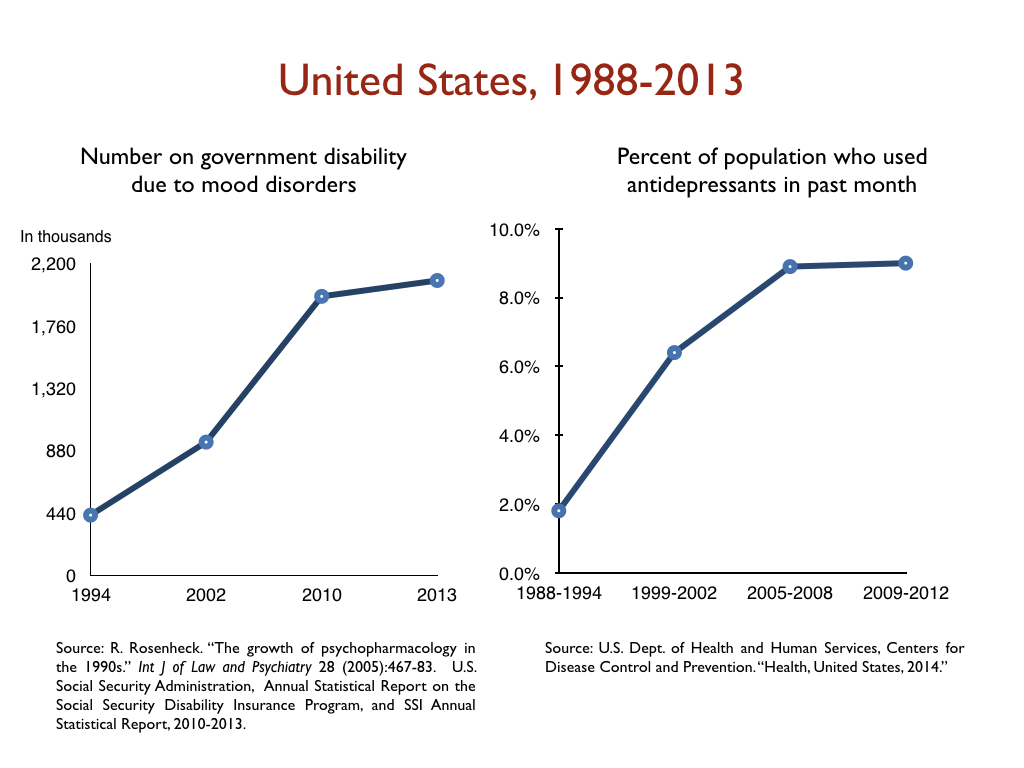

Unfortunately, the public health data tell of a failed paradigm of care. The burden of depression in developed countries around the world has dramatically increased since Prozac arrived on the market in 1987. A 2015 study found that the economic burden from depression in the United States increased from $83 billion in 2000 to $210 billion in 2010.

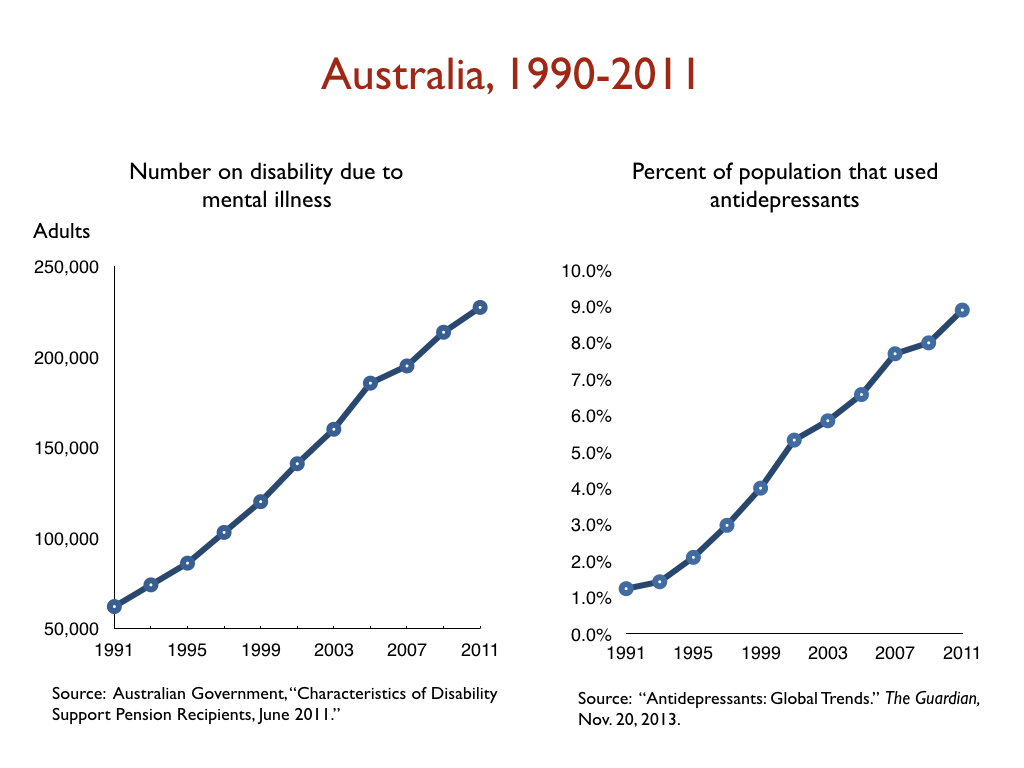

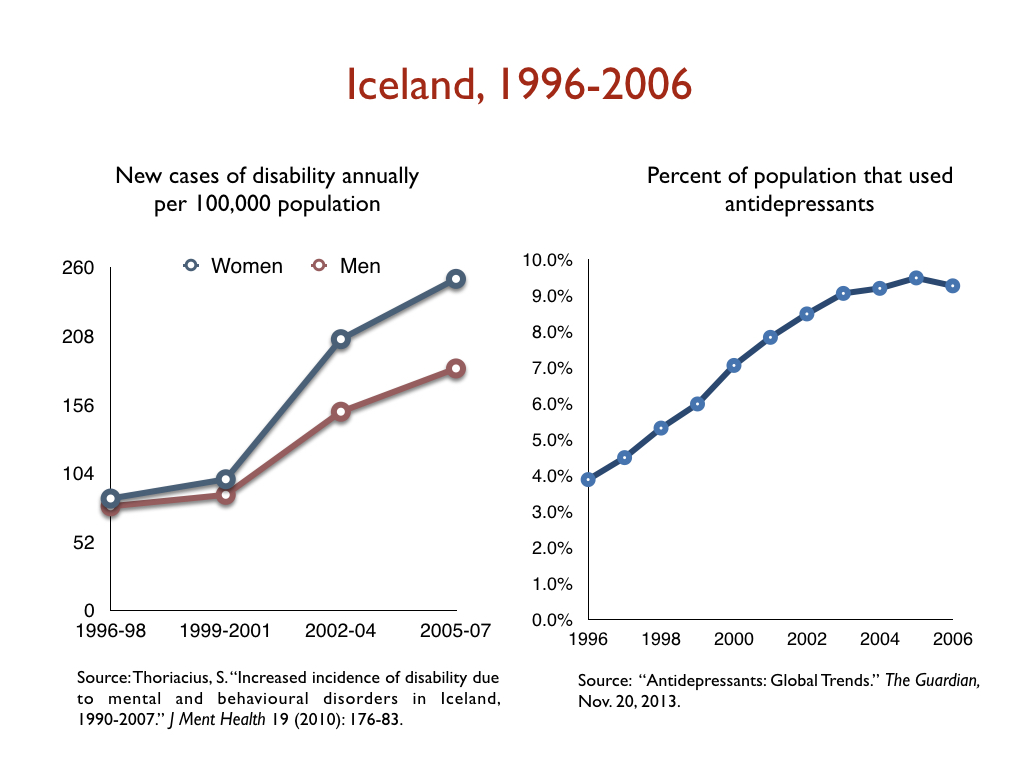

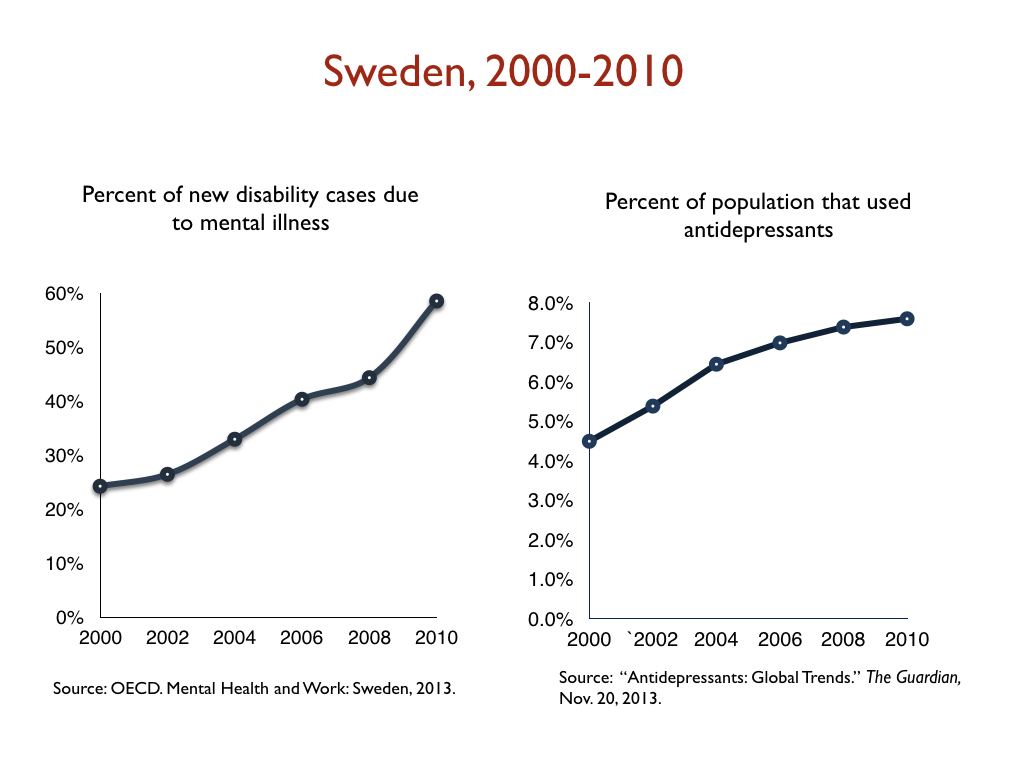

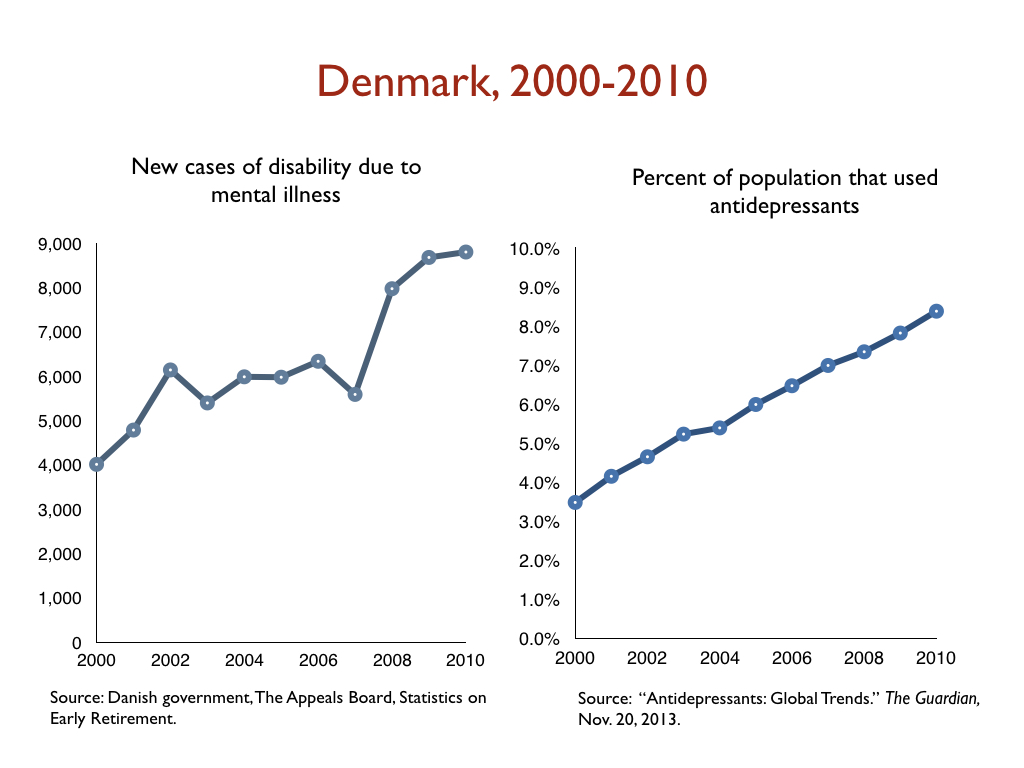

In a similar vein, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of people on disability due to mood disorders in developed countries during the Prozac era, with this increase happening in lockstep with the increased prescribing of antidepressants. Given the disability studies conducted in the United States and Canada, this is precisely the public health outcome that one would expect.

Here are relevant disability statistics for five countries:

I think it is fair to conclude, based on this data, that antidepressants, as they are used now, can’t be said to “work” for society. Instead, they can be said to cause significant societal harm.

Thank Mr. Whitaker. Great work. I will make a more thorough response tomorrow. In the mean time, the question “Do antidepressants work?” is obviously a loaded question. It implies that there is such a thing as an “antidepressant” and that the neurotoxic drugs that are euphemistically called “antidepressants” were designed to correct some mysterious chemical imbalance in the brain, which we all know is simply untrue.

Report comment

Gee I wonder if any psychiatrist will bother to read this. Flies in the face of everything they hold sacred: their self-esteem, their livelihood, etc.

Report comment

I suspect that most psychiatrists and medical prescribers, if they have the opportunity to read this, will dismiss it as antipsychiatry rhetoric. On the other hand, I have been meeting some young psychiatrists who are surprisingly aware of the real literature and who are highly skeptical of the drugs. These doctors will embrace a well written article like this. For myself, I find that articles like these allow me to cite statistics as to why starting with antidepressants is not such a good idea. The days when everyone wanted Prozac are past, and most patients are more interested in good information than a quick prescription. Now if only the doctors could get on board… Articles like this one are not going to revolutionize psychiatric prescribing overnight, but they do have an impact.

Thanks Bob.

Report comment

It’s GP’s that prescribe these the most. They need to be the subject of targeted campaigns at their professional bodies.

Report comment

Had a GP argue that discrimination against the “mentally ill” doesn’t exist. Really.

This naive simpleton also claimed that fruit was “carbohydrate free” and metformin would help me lose weight since 2 pounds a week wasn’t fast enough. He wrote me a prescription for it which I never filled. I do not have diabetes.

Quack quack!

Report comment

Thank you Bob, for a wonderfully argued and well cited review of the “effectiveness” of “antidepressants”. This is an example of the type of information that could make a difference, if more thoroughly disseminated in the wider medical industrial complex. Since I have little faith that it will be read by those folks, I hope it can at least be spread more widely among those who have been or are contemplating psychiatric “treatment”. The societal impacts are profound, and too often the individual harms are ignored or minimized to keep the popular “mental” health narrative going. Wonderful work!

Report comment

Well that was comprehensive. I kind of want to throw it at the Royal College of Trick Cyclists, or anyone else who thinks these drugs are the best things since sliced bread and say, “Take that, you drug pushing idiots.”

I wait to see if there is a rebuttal from someone who should know better.

Report comment

Thanks for this informative and apt review. If people get “chronically depressed”, and “functionally disabled”, as a result of taking SSRI anti-depressants, were one to call for accuracy in advertising, perhaps it would be more fitting to call these drugs depressants rather than anti-depressants. What do the research results actually show? People are more likely to recover off the drugs than on. Hmm. Could it be that these drugs are somehow behind the epidemic of “mental disorders” that we’ve seen sweeping the nation in recent years? I think I could safely place a wager that such is indeed the case. Any studies that would try to say otherwise are obviously based on those short-term studies the drug companies use to get FDA approval, and to peddle their wares. Not surprisingly, a lot of doctors, “mental health” professionals, politicians, and others, are implicated in bolstering this multi-billion dollar industry.

Report comment

Yes. Neurotoxic drugs would more accurately be named “depressants.” Since these neurotoxic, depressant drugs also cause a wide variety of terrible symptoms, and may even lead to violence, suicide, and death, maybe the should be called thanatophoric drugs. (Thanatophoric, meaning deadly, lethal, or leading to death). That’s it. Thanatophoric drugs. “Antidepressants”? You mean thanatophoric drugs?

Report comment

Do thanatophoric drugs work? Of course! They are lethal. They lead to death.

Report comment

The ultimate pain killers. 🙂

Here are more accurate names for drug classes. Diabetes inducers. Passivity enhancers. Thought inhibtors.

Report comment

Exactly. Good one Rachell777… “ultimate pain killers.” Bingo. Psychotropic drugs are pain killers because they kill people who are in pain.

Report comment

Yes! I told the doctor that the drugs my husband was prescribed for “schizophrenia” (valproate) were making him depressed. The doctor said yes, they do that – and that yes, they were supposed to do that, because if a “schizophrenic” is too happy, he might jump off a roof. Unbelievable? No, not from a shrink. (PS my husband is happily off valproate)

Report comment

Of all the exaggerated claims made for this study, the most bizarre is Prof David Taylor, King’s College: “MUCH MORE EFFECTIVE THAN PLACEBO”. I really think we are entitled to know how this flows from an effect size of 0.3.

Report comment

As far as psychiatrists and the drugs they push are concerned 0.3 is an overwhelmingly large number.

Report comment

I often wonder what goes on in the minds of the psychiatrists when they do the hard sell for antidepressants. There are a number of possibilities:

1. They don’t understand the statistics and are swayed by whatever “response rate” is thrown in front of them by the Royal College.

2. They half understand the statistics but believe they will hit lucky and be one of the few who respond well to drugs (although a placebo would probably do the job just as well).

3. They don’t believe the side effects and withdrawal syndromes and think there is no risk so its worth a punt.

4. They genuinely do get it but want to perpetuate the placebo effect. Unfortunately this smacks of snake oil. I have it heard it said that the drugs are fine, its just these damn placebos that are getting so good! Its hard to blame a sugar pill though.

5. They actually want patients that are dependent on them for continued medication for life. Addictive snake oil!

6. They think that even though the statistics are poor, you are correcting a chemical imbalance because thats what they were told. Therefore there must be something holding the medicine back, maybe double the dose might help?

If I ask myself what effect size looks like it would make a difference, I kind of feel 0.8 is justabout doing something. That would rule out all psychiatric drugs (except maybe clozapine- controversial) and a few more common medicines besides. But then you have to look at the harms and the unknowns, and there the psychiatric drugs are potentially devastating.

Report comment

You’re forgetting one – 7. They are receiving direct or indirect kickbacks from the drug companies for prescribing.

Report comment

BINGO!! Steve, you win the prize!

Always check the Dollars for Docs website before going to ANY physician:

https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/

It’s not perfect–there are many creative ways to take bribes–but at least it’s a good starting point.

Also, look up any of their publications and check the section on conflicts of interest.

Good luck finding a doc without a conflict of interest!

Report comment

Oh, THEY know.

Report comment

Lots of great information. One question: I always wonder about comparing outcomes of those on antidepressants vs. outcomes of those never having taken AD’s. How much information do they have re the comparability of the 2 samples?

In this world, it makes sense that anyone who comes near the “mental health”industry will quickly be offered/railroaded into taking AD’s. What causes some people NOT to end up on AD’s? Was their original “depression’ less severe or less chronic than those talking AD’s? Did they have only peripheral contact with the MH industry, so they stayed mostly clear of the industry’s clutches? Did they get a therapist who disliked AD’s? Did they have a personal aversion to AD’s? Did they have none of these, but a really good social and family support system that made them not feel the need. Or, unlikely as it may be, did someone actually give them adequate information on which to base informed consent?

It is important to know how these comparison studies control for these influences. Bob specifically mentions one study in which the non-AD group had comparably severe “symptoms” – that makes me think these issues may not be well accounted for in all such studies. If I were flacking for psychiatry, I would try to claim that the AD and non-AD outcomes stemmed from bias in selection of the groups and their resulting incomparability.

Report comment

Thank you all for these comments.

Peter, much of this research is dismissed by defenders of the usual practices by arguing there must be a difference between those who take antidepressants and those who do not in these “naturalistic studies.” In the Canadian disability study, for example, the researchers hypothesized that those who decided not to take antidepressants had a greater inner resilience. In the six-year NIMH study, while I don’t think there was any difference in baseline symptoms, once again there was some thought that those who eschewed antidpressants were more self-reliant, etc.

The WHO study is different, however. The way this study was done was this: WHO researchers screened people coming into GP offices for treatment of some kind (physical ailments, etc.), and identified those who were depressed (and with baseline scores, etc.) But they didn’t say anything to the GPs, and hypothesized tht if the GPS identified the depressed patients and treated them, they would do better than the patients who were depressed but that the GPS failed to diagnose.

The hypothesis didn’t pan out. Diagnosis plus treatment led to the worst result. But the researchers did have baseline scores for everyone, and as you can see in the graphic above, Medicated Patients Stop Getting Better After Three Months, their baseline scores were virtually the same. But what is so notable is the difference in trajectories following three months. You know how some patients complain about Prozac poop out, meaning the drug stops working? This graphic shows that.

But beyond that, naturalistic studies always have this problem of possible differences in initial severity, or difference in personality types. But still they provide an important additional body of evidence to consider, and thus are part of the research evidence that needs to be reviewed.

Report comment

It is also bad science to propose new hypotheses to explain away experimental results. They are supposed to state their hypotheses BEFORE running the experiment! Their new hypotheses might form the basis for another experiment, but are IRRELEVANT to their current experiment, as they are pure speculation without further testing. One can almost always come up with multiple ways to explain an outcome, but only pre-existing hypotheses that predict the outcome before it happened can be considered legitimate scientific results.

Report comment

Cooking up hypotheses to support forgone conclusions sounds like rationalization.

The experiment says A but I want it to say X so I’ll hit it with a hammer repeatedly til the pieces all fit. Sigh.

Report comment

Now that inspires me to donate.

Thank you Mr. Whitaker, I was waiting to hear your response.

Report comment

This test is going to go a long way in exposing the harm done by these drugs. To date I have not been able to establish any more information about it. It must be a Cytochrome P450 test. We want transparency on how the information will be used, we want to know if patients will be informed of the results, so they can ascertain past or on going harm done to them by GP’s, psychiatrists and any other doctor..

https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/health/926794/gps-offer-genetic-testing-prescriptions-dna-reduce-side-effects-of-drugs

So how is it this test can reveal the potential harm done by these drugs ?

When we ingest drugs, they are metabolised by enzymes, a particular family of enzymes called Cytochrome P450 are responsible for metabolising most drugs. The important thing to know is that, HOW you, as an individual, metabolise the drugs will determine if you get toxic on them and have a appalling time trying to come off them. This is because we all have different enzyme strengths or phenotypes, these are designated as: normal, intermediate, poor, rapid, ultra-rapid. This is how it can be worked out, although it is not the full picture, being as common food stuffs, herbs and spices also inhibit the enzymes.

Report comment

This is exceptionally good reporting. As someone with 30 years of experience living with OCD and taking high dose ssris for this whole period, I am devastated to learn the truth. Thank you for showing me how these drugs lead to long term disability. I might have lost my life to these drugs but I will make it my mission to warn others.

Report comment

BTW I am finding help finally from a treatment called inference based therapy (IBT) which is a different CBT approach to the resolving of doubt -the very origin of OCD errors in reasoning.

I plan to slowly go off these drugs as treatment begins to take effect. This will be painful but necessary.

Report comment

Depression drugs are compared to cold turkey withdrawal in the placebo group. Even if people in the placebo group are in total abstinence from their previous drug, they do so well without their drug that neither patients nor doctors would be able to know the difference. The placebo group gets as good results as the drug group one week later.

Report comment

Depression drugs are tested by the companies that make them. This is like Pepsi testing if Pepsi is better than Coca Cola or a mobster being judged with only family members in the jury or a judge asking the accused to provide condemning evidence in his own trial. In all other areas of life we disregard the results that come from these kind of testifying on your own behalf.

Report comment

The drugs are not tested on the people who will actually use them. This is like testing drugs against pneumonia and patients who have stomach problems. 90% of the patients will take depression drugs, or not the patients that the drugs have been tested on. This means that we have no evidence base for using these drugs for 90% of the patients who are taking them.

Report comment

There is probably a very simple reason why depression drugs don’t work for children and adolescents, and why they seem to be better for the severely depressed.

Children and adolescents are less likely to be on a previous antidepressant when they take part in drug trails. Therefore we are probably testing the true effect of depression drugs in this group. And the drugs increase suicidality and have no effect.

The severely depressed they are more likely to have been on depression drugs for a long time, and often in high doses, so when these people are put in the placebo group, they have a worse withdrawal response than other patients. This is exactly what the results show: The depression drugs don’t work better in this group, but the placebo group is doing worse, so it seems like the drug it’s more effective. It is quite obvious that the person who has been on depression drugs for years and then goes cold turkey, will be doing quite badly for the whole eight weeks.

Report comment

It is quite amazing that the drug that increases the death rate with 66% in older patients can be used at all, however good it is. When we know that these drugs also make people unable to go back to work according to the research above, it is beyond comprehension that these drugs would be used at all. If people knew that Depression drugs increase the death rate of 66%, meaning that people die 11 years early on average when they take antidepressants, nobody would take them. When we also see that the drugs at least double the rate of dementia, the situation becomes even worse.

Report comment

It is very interesting that the drug industry and psychiatry now feel that they have to defend their drugs. That means that the wind is changing. They are not going forward with optimism, but they have to defend themselves.

Those of us who feel that the science behind this should be known by everybody, should use all the tools we have available for letting people now know the facts. Please spread the word about Robert’s excellent article everywhere, and you can freely copy and paste my arguments to any post you would like on social media. If anybody cares to edit Wikipedia articles, they will usually let you make a statement there if you referred to a meta-analysis or literature review. If anybody cares to make YouTube videos, this is also very effective for the younger generation. Making comments to youtubers with millions of subscribers could also be very effective. Maybe they will make a video about Depression drugs.

Report comment

I keep reading about different types of depression, like “minor depression”, “moderate depression” and “severe depression”. My question is: how objective are these categories? And how does one assess which type of depression the patient belongs to? Sounds kind of arbitrary to me. It’s one thing to state that antidepressants work for the severely depressed (which may be true or not). But who decides what defines severe depression anyway? Because if it’s impossible to tell with certainty that a person is “severely depressed”, how can one conclude with certainty that this patient will respond to antidepressants? I’m sure most doctors and psychiatrists are convinced that any patient who has symptoms of depression must be automatically severely depressed.

Report comment

These designations are completely arbitrary and subjective. They’re based on scores on a depression questionnaire, which relies either on patient reports on subjective questions, or caregiver reports on the same subjective questions. It’s kind of like someone saying, “I feel severely depressed,” and you saying, “That means you have severe depression.” It’s all BS.

Report comment

All mental health/mental illness diagnoses are completely arbitrary and subjective. I challenge anyone to demonstrate with a high degree of confidence that the biochemical, physiological and/or anatomical changes that are supposedly associated with particular mental illness diagnoses are not a result of physical, emotional, and/or economic abuse, rather than being the inherent defect leading to development of mental illness.

There is no way to conclusively separate cause and effect when society refuses to acknowledge the existence of the major driver of mental “illness”: societally-sanctioned abuse aimed at those who do not conform with the societally-sanctioned world view.

Furthermore, the stress associated with being labeled with a diagnosis that is overwhelmingly associated with stigma and discrimination can lead to further biochemical and anatomical changes in the brain, as well as as the rest of the body.

Report comment

Could not agree with you more. Well stated!

Report comment

I was reading an article in a religious magazine yesterday about benefits of sadness–it causes us to be more empathetic and thoughtful for example.

The writer hurriedly made the proviso that sadness was different from “real clinical depression which science has proven to be a chemical imbalance in the brain. If you have that be sure to get ‘help.'”

How do you distinguish between the two? There is no test to measure brain chemistry.

I felt sick and quit reading the article. Naive simpleton! Folks like him LOVE psychiatry since it absolves them from doing squat to help the hurting in their church.

No Rev. Dork, you think you’re humane and scientific, but actually you’re neither. And if you chose to know anything but what you see on television you wouldn’t make such an easy mark for the Rx drug industry!

Report comment

Same here. I have never understood how psychiatrists – or anyone for that matter – can say they can see the difference between sadness and “clinical depression”, whereby the latter is supposed to be caused by a chemical imbalance. As if there are two kinds of depression: the one caused by emotions or social circumstances, and another one that appears out of nowhere and so it must originate in the brain or the body. There is no “nowhere” because everyone has a past, everyone has emotions, and there are always circumstances.

Report comment

The removal of the bereavement exception in the DSM-5 definition of Major Depressive Disorder is proof that sadness, when seen as extreme over a few weeks, is indeed regarded as clinical. It’s as if a psychological injury then triggers a biological illness, chemical imbalance etc. That does not definitely precipitate medication, of course, and there seems to be no evidence of anything.

Report comment

There is no legitimate test for “chemical depression.” Unless you count a check the boxes thing that belongs on a site like quizme.

What kind of dog are you? What kind of movie is your life like? Do you have clinical depression? Real science folks!

If you make the mistake of seeing a shrink they will simply assume you must be “mentally ill” depressed. They sell more pills that way.

Report comment

All those tests are designed so that anyone taking them comes out as being “depressed” or “mentally ill”. There is no diagnosis for “normal personality” in psychiatry anyway, so it’s impossible not to get diagnosed with something. And if you don’t tick all the boxes they just add “not otherwise specified”. “Depressive disorder not otherwise specified” is so vague and meaningless that I don’t know any person who doesn’t fit the description. Who is perfectly happy all the time then? No one.

Report comment

The term “clinical” is another thing that bogs my mind. What does that mean anyway? Isn’t that just “because the doctor says so”? It’s like when you go to the doctors and say you feel depressed, and the doctor replies: “Oh, I see. I think you have a depression. Now it’s clinical because I “diagnosed” you.” What “diagnosis”? I just told you myself I feel depressed 2 seconds ago! You simply repeated it!

Report comment

Telling a shrink you are depressed is like confessing to witchcraft before the Spanish Inquisition. Shrinks should be made to mirandize every person who walks through their door.

Report comment

I was taught this word on Surviving Antidepressants from a veteran there;

Diag-nonsense.

It’s all diag-nonsense.

https://youtu.be/YecBv-5JXmQ

(King Crimson: Elephant Talk)

Report comment

Personally, I think the question—do antidepressants work—is a poor way to frame this debate.

Exactly. “Work” at doing what? Making people compliant with totalitarianism, or at least too incapacitated to do anything about it? They’re pretty effective at that.

Report comment

Not enough apparently. Killing sprees are not a sign of passivity.

Report comment

Thanks for this report.

Report comment

I wonder if antidepressants/psychotics emotion-numbing effect has anything to do with declining birthrates in western countries. Just a thought..

Report comment

The biggest question is why no one else seems to make this connection. 25% of college students have diagnoses of “mental illnesses.”

Report comment

You said in your first book on this that the brain is a self-correcting feedback system, which can be sent into unstable oscillations by a strong chemical push.

That’s consistent with your recovery-vs-disability statistics here — but there are contextual factors that would also make anyone psychiatrically medicated more likely to continue taking them, more likely to consider himself disabled. Doesn’t he know he’s been prescribed meds? Hasn’t he been taking them? Wouldn’t he have felt worse without them? Won’t he feel worse if he stops? Doesn’t his doctor think he’s likely to need them indefinitely?

Aside from long-term double-blind placebo tests, the relative impact of various causes might be impossible to sort out! (I couldn’t say, whether it’s harder to recover from toxic pills than from toxic social expectations — or whether both together would be that much worse. But going by various friends afflicted with the “I am Mentally Ill” belief system, it seems both intractable & likely to lead to further drugging.)

Report comment

A friend of mine quit his lithium for 10 years. Yet he kept saying he was “bipolar.” He’s in the System again.

Report comment

Dear Robert,

All I can say is WOW! This is quite astounding. I knew that you cannot trust RCTs because of the numerous loopholes, but your findings suggest that toxic substances that make people more depressed, more suicidal, and more disabled both short-term and long-term are successfully sold as “antidepressants”!!

We live in a truly perverse and deceptive world that can only be described as The Matrix, complete with a fake government, fake mass media, and science that serves as a puppet for the Wizard of Oz.

Unfortunately, a book or an internet article will not affect the clinical practice of psychiatry, even if you give your books away for free as I do mine. I sincerely hope that you can publish these findings in a peer-reviewed scientific journal with the help of the good scientists that post on this website. It doesn’t have to be a “high-impact” journal. In fact, any scientific journal that is indexed in PubMed will do. Then your results and ideas will make an impact and shake some psychiatrists off the Matrix. Publishing a comment on one of these flawed reviews like Cipriani et al. (2018) will be less effective but better than nothing.

Report comment

Thanks, keep up the good work.

If only psychiatrists would stop prescribing, they have a duty to not to harm their patients which is exactly what they do with their psychotropic drug cocktails.

I am tapering of antidepressants for more than 3 years now. Currently at 0.65 mg.

Horrible drugs, I have an underlying ptsd condition, antidepressants make it impossible to heal.

Once I got to 3mg or so, I noticed my dissociation symptoms just becoming significantly less severe, the only thing I did was lower the amount of ad !

EMDR also does not seem to work when on antidepressants according to my psychiatrist.

HORRIBLE drugs.

Report comment

One important question is what is meant by “depression” in each clinical trial or study. Does the patient base include people who are in distressing situations, such as bad marriages, bad jobs, or grieving? Such situational depression tends to resolve on its own within months and used to be excluded from the diagnosis of “major depressive disorder” (MDD). Now MDD can be diagnosed in a ham sandwich.

For people with situational depression, a diagnosis of MDD might well convince them they have a permanent disease. Combined with drug side effects, they may well be impaired for a period beyond the normal course of recovery, while not experiencing much relief from the distress — they’re still in a situation that needs resolution. Pills rarely do this.

In other news about psychiatric drug efficacy:

Psychother Psychosom. 2019 Mar 20:1-9. doi: 10.1159/000496734. [Epub ahead of print]

Withdrawal Confounding in Randomized Controlled Trials of Antipsychotic, Antidepressant, and Stimulant Drugs, 2000-2017.

Récalt AM, Cohen D.

Abstract at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30893683

BACKGROUND:

Results of relapse prevention randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which discontinue psychotropic drug treatment from some participants may be confounded by drug withdrawal symptoms. We test for the confound by calculating whether ≥50% of the difference in relapse risk between drug-discontinued and drug-maintained groups is present at discontinuation time points (DCTs) with “short” and “long” assumptions regarding onset and duration of withdrawal symptoms.

METHODS:

In eligible RCTs of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and stimulants from 2000 to 2017 (n = 30) selected from a systematic review, differences in relapse risk were examined by arithmetic and graphical comparison of mean behavioral scores or survival plots.

RESULTS:

Only 14 studies (46.6%) with 15 analyses of relapse risk provided sufficient data. Under short and long DCTs, 9 of 13 (69.2%) and 7 of 9 (77.8%) interpretable analyses, respectively, suggested a withdrawal confound. The proportion of endpoint placebo-maintenance group difference present by the DCT averaged 69.1% (range, 58.7-148.0%, n = 13) for short DCT assumptions, and 79.0% (range, 51.5-183.3%, n = 9) under long DCTs. One study (3.33%) controlled for withdraw al effects, and 1 yielded inconclusive results.

CONCLUSIONS:

These results support suggestions that withdrawal symptoms confound the results of relapse prevention RCTs. Accounting for such symptoms in RCTs is an ethical, scientific, and clinical imperative. Justifications for relapse prevention RCTs employing a discontinuation procedure require more scrutiny.

Given the razor-thin margins for significance in findings for psychiatric drug efficacy, the confounding of withdrawal symptoms for relapse may well tip all of these studies into findings of no significant efficacy for each drug.

Report comment