I don’t know about you, but for me, the lines between trauma, stress and suicidal depression can get pretty blurred. Whatever you call it, I feel like I’m being attacked from all sides. The universe is out to get me. Nothing I do can make any difference. My mind and body have betrayed me.

- Family and friends become suspects or spies.

- Help degrades to force or manipulation.

- Reassurance mutates into lies.

- Neuronal connections to happy, hopeful memories drop like flies.

I once spent four years of my life like this. The lion’s share of it I was praying to die. Life was a prison camp with no future. Just torture or death in a hold so deep and dark no sunlight made it to the walls.

The last fight left was with myself. Conscience in chains, I watched my integrity slither away and disappear through a gap in the bars.

I tried to describe what was happening to my doctor: Are you sure this is depression? Because it feels like abject terror to me. It’s as if some portentous wraith showed up, hijacked my body and opened a refuge for underworld drifters. Now, they’re all hanging out, making themselves at home, feeding on my energy and laughing at what a goner I am. It’s no use trying to kick them out. The next day they’re back in force with a new pack of goons, mocking me for trying and tormenting me all the more.

Doctor: You’re depressed. Your symptoms are classic. Your mother had depression. Your grandmother had depression. It’s genetic. Take your medicine. Eventually you’ll come out of it. Most people do.

Maybe he was right. I did come out of it. Meds probably played a role.

But I think I was righter.

Nailing Jello to the Wall

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®)1 devotes 34 pages and a host of symptoms and diagnostic specifiers to the various permutations and combinations of human despair (pp. 155-88). When you look at it, these criteria are all over the map. There’s no rationale for why certain things cluster. It’s like nailing jello to the wall. As a diagnosed person, it spawns an almost overwhelming urge to throw up my hands, stick my head in the sand, and turn over my future to someone else.

This is what makes the stress response so exciting to me. All I have is a lay understanding of stress. I’m pretty much totally self-taught at the level anyone can get by reading a bit of popular science. But if I combine that with a survival/trauma paradigm called “the defense cascade” that’s emerging in the clinical literature, I can make sense of every symptom and subtype of depression based on my own experience of what happens in my own body. In fact, I can pretty much do this with the entire DSM.

This raises, for me, some important, troubling questions. By and large, most of society agrees we have a depression epidemic that affects millions of people each year. Everyone also pretty much agrees that suicide rates are disturbingly high. Yet, by and large, the mental health industry is still seeing and treating these concerns as biochemical and genetic in origin.

But the fact is, my body can turn this kind of stuff on and off, practically on command. Just in the course of writing this blog, I got to see, time and again, how all of this stuff eased or passed as the stress equation in me changed. Sometimes on, sometimes off. Sometimes many, sometimes just a few. On and on, over and over, in various patterns, depending on how, for me, the stress-cookie crumbled.

And, over the course of three months, I cycled through pretty much all the so-called symptoms of DSM depression. Just based on how stressed I was or wasn’t, while writing this blog.

So what does that say about the biogenetic, chemical imbalance theory, where depression is a lifelong illness and all I can do is take my meds?

In other words:

- What if we don’t have a depression epidemic at all? What if we have a stress epidemic that’s reaching traumatic/survival proportions…?

- What if the reason a lot of us aren’t getting any better or feeling any better is we’ve been taught to believe we have a lifelong, incurable disease?

- What if we’ve been steered away from exploring our minds and bodies—learning how they actually work—and into believing that our attempts to survive and respond to traumatic, threatening real-life circumstances are “symptoms of mental illness”?

- What if a huge part of our distress is that we’ve been advised, by professionals, society and everyone else in our known world, to just sit still and wait for “the experts” to fix us—and until then we’re out of options?

As we will see in just a few hundred words, that kind of thinking—in and of itself—is a recipe for a state of “traumatic immobility” that explains away all the major indicators of DSM depression. Yep, no real disease needed. Just an effed up brain loop sold to us by Pharma, payola government, and the mental illness industry.

Introducing the Defense Cascade

The defense cascade is this framework that trauma therapists have been working on. I have a really cynical theory as to why.

Obviously, recalling trauma can be upsetting. So upsetting, apparently, that some of us become unresponsive.

It turns out that this can create quite a crisis. You might guess for the client, but it’s actually the clinician that I suspect the concern is mostly about.

Suppose you’re a therapist and the 50-minute hour is over. So you say to the client, “Your time is up.” But they don’t move. So you say it again, but they still don’t seem to hear you. So now you muster your most firm, directive clinical voice, “Your time is up. I’ll see you next week.” Still nothing. Just dead air. It gets even worse because ethics prevent you from even patting the laggard’s arm to get their attention.

Given that there is usually a client #2 in the waiting room whose session can’t start until #1 is removed, you can imagine how many therapists this may have traumatized.

Eventually, this phenomenon recurred enough times that it couldn’t be written off. It had to be more than pathetic, Hail Mary, end-of-session attention-seeking by said client #1’s. At that point, the professional world took some interest and some measurements.

What they found was fascinating:

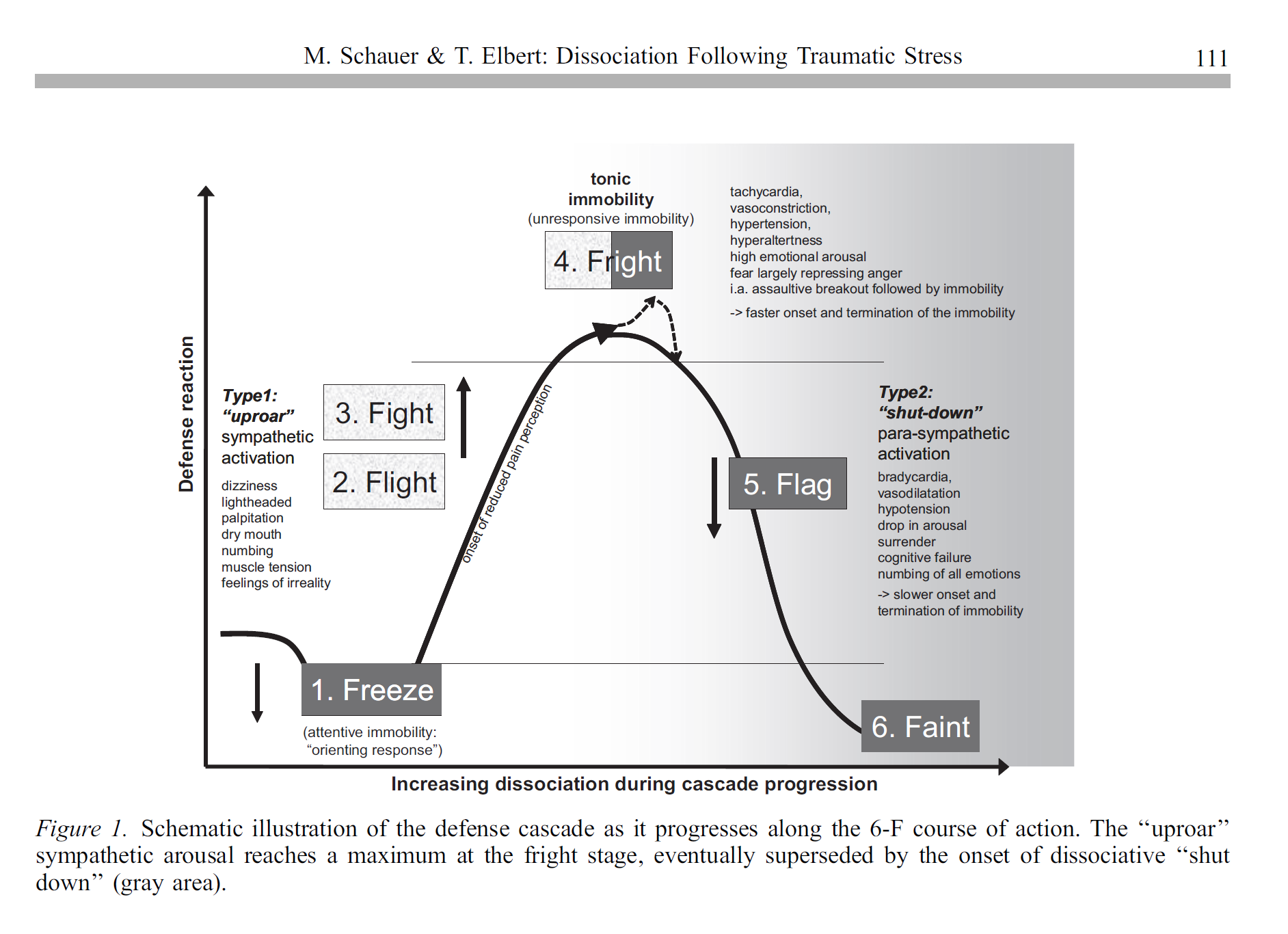

(Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 111)2

(Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 111)2

As it turns out, the phenomenon we are talking about has a real name (#4 in Figure 1 above: Fright / tonic immobility). It also has measurable, observable physiological characteristics (Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, & Carrive, 2015;3 Schauer & Elbert, 2010; see also Roelofs, 20174).

Not only that, but it seems that there is a logical progression—and clear reasons in mind and body—for when and why this phenomenon appears:

[W]e propose that defense reactivity is organized to account for battlesomeness (chances to win a fight) of the threatened individual, that is, the appraisal of the threat by the organism in relation to its own power to counteract (age, gender, physical condition, defensive abilities, etc.) and, not least, for the threat-specifics (type of threat, type and speed of approach, context, threat involving blood loss, etc.). Whereas the dynamics of the defense cascade progresses in gradients of alternating ascending and descending activation, the various defense responses can be categorized into two general forms, namely active defense and immobility. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p.110.)

In other words, my body offers me two basic types of defenses (active/immobile) when I feel threatened. After a preliminary appraisal, I go with the approach I think offers me the best chance to survive.

The type of defense I choose (active or immobile) depends on how threatened I feel. In addition, both types (active, immobile) give me some sub-levels to choose from as the degree of threat changes. Different body systems are brought into play, in different combinations, based on the defense level I end up going with:

Our model … suggests six defense responses, notably Freeze, Flight, Fight, Fright, Flag, and eventually Faint, whereby during the two Fs Flight and Fight bodily responses are mainly regulated via the sympathetic branch (‘‘uproar reactions’’) and the following three Fs, the second half of the cascade, are dominated by parasympathetic arousal, determining the spectrum of dissociative responding (‘‘shut-down’’ reactions: Fright, Flag, and Faint). We thus may arrange the stages of the defense cascade in form of an inverted u-shaped arousal function with the alarming flight-fight responses on the ascent of the curve and the set of dissociative variants on the descent (see Figure 1). (Schauer & Elbert, p. 111, 2010)

A simple way of thinking about this is like a car. The active defenses—Fight and Flight—are controlled by the Gas Pedal (sympathetic) system. This system gets energy to my muscles and allows me to move. From there, it is a simple matter of direction:

- Fight is like barreling forward into the stuff I’m afraid of.

- Flight is like backing up and trying to get away.

Most people try to get away from scary stuff if they think that’s an option (Schauer & Elbert, 2010).

Freeze, Fright, Flag and Faint are all dominated by the Brake (parasympathetic) system of the car. If a Brake response comes on, it means that, for one reason or another, my body has decided that it’s smarter to slow down or not move at all.

What is this thing called Fright?

Fright is a state of intense distress, equivalent to what my car would probably feel if I floored the Gas Pedal and slammed on the Brake at the same time. Like my car, the engine is all revved up and raring to go, but the energy it produces is totally jammed and blocked from taking me anywhere.

In humans, this dual activation of both the Gas Pedal (sympathetic) and Braking (parasympathetic) systems of our bodies is called ‘Fright.’ It typically occurs when intense fear or threat combines with a sense of being trapped or constrained. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010) Essentially, a threshold is reached where mental and physical arousal are sky-rocketing. But there are no good options and thus, no viable strategy for unleashing all that energy. It is no longer adaptive to run or fight (active defenses), so the body changes tactics and begins to shut down (immobile defenses). In the prodromal period before complete shutdown, “[g]eneral fear symptoms are experienced, including dizziness, nausea, palpitation, drowsiness, lightheadedness, tension, blurred vision, feelings of irreality, numbing, and tingling appear” (p. 112).

As the lack of options is confirmed and hopelessness sets in, distress and activation jointly peak in a “peritraumatic ‘panic-like’ dual autonomic activation” (p. 112). This is the tipping point: “sensation, perception, motor abilities, and speech behavior are dramatically altered” (pp. 112-13, emphasis supplied). A “‘shut-down’ reaction” occurs (p. 112):

- The Braking (parasympathetic) system powers on—forcing heart rate and blood pressure down and making active defenses all but impossible.

- The Gas Pedal (sympathetic) system goes into overdrive—muscles become “overly tense and rigid,” and movements are “slow and difficult”—to the point where “overt behavioral actions are not an option” (p. 115).

- Normal channels of awareness and perception are blocked, and endogenous opioids flood the system.

In this dual Gas Pedal/Brake state, “various forms of dissociation appear” (p. 112):

- “Memory retrieval deficits” occur (p. 113).

- Consciousness alters, with a prevailing sensation of “alienation of oneself or the external world” and “a flattening of emotional experiences” (p. 113).

- There is failure, of both mind and body, to “deliberately control processes and take actions that can normally be influenced by an act of volition” (p. 113):

As a result, previously accessible information does not reach conscious awareness, and voluntary movements are not attempted. (p. 113)

Why would I ever opt for Fright?

Fright is basically a strategic surrender when I’m overwhelmed and out of options. It buys me time to regroup, and I also hopefully get hurt less:

Tonic immobility [fright] is almost always displayed when the person is overwhelmed by threat and not allowed and not able to act aggressively against the threat. Thus immobility functions to suppress anger in the victim and acts bidirectionally to inhibit aggression. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 116.)

To grasp what’s going on, let’s take a look at how this plays out in the wild.

Suppose I’m a rabbit trying to avoid becoming a foxy meal. I’ve run my fastest, fought my hardest, but I’ve lost. So now the fox has me down by the neck, and it looks like I’m done for.

Not so fast! I still have one trick left up my sleeve: Play Dead. Next thing I know, the Brake slams on and overrides the Gas Pedal. Instant immobility.

Surprisingly, Fright may save my life. The Braking system so completely subdues me that I give no appreciable signs of life. The fox thinks I’m dead and loses interest or his appetite. The moment the fox is out of sight, the Brake lifts, and I floor the Gas Pedal back to my hole.

Time for the Spoiler

As you may have guessed, the Fright response is a big part of what I’m referring to here as “traumatic immobility.” It’s not the only factor, however.

Traumatic immobility also extends to stages 5 and 6 (Flag and Faint) of the defense cascade (see Figure 1 above). Flag and Faint largely result when Fright goes on too long, or when distress continues to rise. At that point, awareness of suffering loses adaptivity, so the Braking (parasympathetic) system shuts down consciousness even further, and Gas Pedal (sympathetic) arousal fades away. I end up just laying around—a sort of floppy, semi-comatose, helpless blob. That’s Flag. If I become wholly unresponsive, that’s Faint. Either way, no more faking it—this is true surrender. My mind and body have conceded defeat, and we’re just waiting for the end.

Each of these variants on traumatic immobility has something to add to our discussion of depression. As we will see in a later piece, Fright, Flag and Faint all meet the DSM criteria for a Major Depressive Episode in their own right. In addition, they each neatly correlate with a specific depressive subtype (i.e., anxious, melancholic and catatonic features, respectively).

There’s some ground work to lay before we get to that. Right now, it’s time to dive deeper into traumatic immobility and the paradigm shift it points to.

It’s not all in my head

When I came across the defense cascade, I could have kissed the researchers who wrote the article. Finally I had some answers. Finally, I could explain experiences and deep moral conflicts that had been dogging me for 20 years. Finally, it wasn’t all in my head.

Here are the basic components of traumatic immobility (Fright, Flag, Faint on the defense cascade).

- Overwhelmed by threat

- Out of options

- Gas pedal (sympathetic) activation or shut-down

- Brake (parasympathetic) shut-down

- Reduced capacity to respond, mentally and physically, to compelling life circumstances

Here’s how I applied that to make sense of my last major depression/DSM symptoms two years ago:

- Felt constantly threatened (repeated job loss, poverty, homelessness, out of sync with mainstream & workplace values, relationship failure, social pariah): low mood, worry, mental and physical activation, weird appetite and sleep

- Felt out of options (low physical, material and social resources; tired all the time, brain not functioning): hopelessness, sadness, despair, indecision

- Gas pedal/sympathetic (constant pressure to do something to fix it): worry, activation, insomnia, eating for energy

- Brake/parasympathetic (no clue how to fix it, where to turn or if it would ever get better): Low energy, low mood, low appetite and low interest in life; digestive troubles, stomach cramps, poor thinking and concentration; leaden limbs, sleeping a lot

- Life indefinitely stalled by Brake (wasting my life, leaving a legacy of suffering and pain, letting myself and others down): Worthlessness, emptiness, guilt, indecision, crying a lot, preoccupied with death and suicide

Again, this is just a first offering. In a future piece, I will go deeply into the DSM definition of depression and really deconstruct it—subtype by subtype, symptom by symptom, line by line. But right now, I have bigger fish to fry. Because for me, the DSM criteria didn’t come close to capturing the distress I was feeling. And they certainly didn’t give me a clue as to why. So I want to take some time and go into that now.

Where did I go?

For me, depression was like being in a constant state of grief over someone who was lost—except it was me. The person I had known myself to be wasn’t there anymore, and, for all I could tell, was permanently gone. All that was left for me was to wait in bed and hope she would return. So I just sat there watching as life passed me by and everything and everyone I had once cared about slipped away or left.

Then there it was—the reason in print:

In order to enable a maximal defensive and ‘‘dead’’ appearance (‘‘as if dead,’’ ‘‘playing possum’’), which provides survival advantage by complete giving in and cessation of fighting, moving, perceptions and later emotions need to be switched off or deactivated. To guarantee motionlessness in these highly perilous situations, the organism should be unable and unwilling to use voluntary muscles and should feel neither anger nor pain, be finally emotionally numb, as if anesthetized (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 113, emphasis supplied).

I found this weirdly reassuring. Knowing what was happening and why made me feel so much safer: I’m not actually dying. I’m not even lost. Rather, a part of me is so scared—so in over my head about something gone wrong in my life—that my own body has shut me down. My very aliveness is being hidden from me (and others), deliberately, in response to the situation I am in.

But how does my body make all of this seem so convincing?

As it turns out, the way we perceive ourselves as being alive—and as actually present in our bodies—probably has something to do with the continual sensory feedback that our bodies give to our minds:

A person’s sensory processing (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch), of kinesthetic (perception of movement and muscular sense) and somesthetic (sensory data derived from skin, muscles, and body organs) stimuli normally continuously serves the perceiving self as evidence that it resides ‘‘in’’ the physical body. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 117)

It probably also has a lot to do with our experiences of thinking and feeling. This is not just awareness of sensory information, but also the associations, emotions and memories they generate, and all the mental processing our minds do about them. (p. 117)

During traumatic immobility, the Brake system progressively shuts this down:

Kinesthetic, somesthetic, nociceptive stimuli no longer seem to reach the central processing units, causing changes in body awareness and loss of control (depersonalization). Numbness prevails…. Conscious processing of the events becomes limited, making meaning seems irrelevant…. emotional involvement fades away, that is, no action dispositions are assembled and memory consolidation becomes weak and later rehearsal more difficult. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 118)

Thus, access to the thoughts, feelings and sensations that I experience as the essence of me is blunted or blocked. And so is my motivation and ability to address that. (p. 117) The resulting internal silence is deafening. I literally feel like I am dying—that the essence of “me” is gone, probably for good.

Am I Just Faking It?

The “Play Dead” response explains another thing that has really tortured me. I had this nagging sense, at the height of my depression, that actually I am faking it. There was this odd internal turf war: Something deep inside me has dug in its heels and insists it will not move, while something else is whispering in my ear: You could do better if you tried.

Well, there’s an answer for that too. Traumatic immobility isn’t called the ‘Play Dead’ response for nothing. A part of me knows there’s still life inside somewhere. At the same time, the physiological changes that are taking place totally convince me otherwise. With heart rate capped, digestion cramped, and righting reflex pulled out from under me, instinct commands that I lie down. Endogenous opioids (endorphins) swoop in. Communications crash, and it all gets very, very heavy. The rest is history.

Am I Morally Weak?

One of the hardest things about this state of mind and body was having to face myself: Where did my integrity go? Why was I groveling in fear?

There was no physical predator standing over me. I was being stalked by paperwork, bureaucracy and poverty, not a lion or the Huns. I knew I was being irresponsible. I knew there was business to attend to. I knew there would be no rescue unless I created one.

But still I couldn’t do it.

Why, why, why?

Here’s at least a partial answer:

Tonic immobility guarantees negative or quiescent behavior even in the presence of massive aversive stimulation, a stilled organism that makes no attempt to struggle for freedom or fight. (Schauer & Elbert, 2010, p. 115, emphasis supplied)

The implication: In this state of mind and body, survival instincts override the impulse toward ‘recuperative behavior’. (p. 113) I remember being hypnotically suggestible to some internal whisperer—Stay still. Don’t move. It’s not safe enough yet. Getting up now will be certain disaster. It seems ludicrous in retrospect. There were deadlines to meet, rent to pay, taxes to file, phone calls to make, forms to complete. But I just lay there waiting. Desperately hoping for the odds to change.

Again, it helps to understand the physiology. The same ‘decoupling’ we talked about above between body and brain likely affects our capacity for executive functioning—the ability to plan, prepare, and be disposed for action. (p. 119) It also affects the mirror neuron region of our brains, which helps us reflect and connect ourselves to the behavior of others. (p. 119) The joint effect is a vastly reduced ability to appreciate consequences, care about them, or mobilize the resources needed to address them.

The dis-ease of being human

I don’t know about you, but all of this helps me feel a heck of a lot more hominid and a heck of a lot less pathological or creepy. Instead of thinking of myself as having a brain disease, abnormal, defective, mentally ill, chemically deranged, mentally unscrewed, at the mercy of mysterious factors, randomly firing, totally out of my control—I can just say to myself: Oh, I’m having a rough time and my stress is too high. What do I need to change? That shift alone brings the stress down several notches.

Imagine what that could do for other people too. Instead of those around me looking at me and saying: Oh, what a weird freak. She’s got this crazy, deranged brain thing going on that could make her flip out on me at any moment for no reason at all, they can go: Oh look, she’s having a rough day and her stress is too high. How can I be helpful?

Suffice it to say, the stress response is a great leveler. It’s vastly different that we’re talking about something all of us can relate to—a genetic endowment we’re all born into by virtue of being human. Call it the “human condition” if you will.

In a lovely, quirky way, it’s both reassuring—and threatening—for everyone:

- We’re all in this together.

- We’re all genetically predisposed.

Now that we’ve come full circle, I’ll happily concede this one to my doctor. After all, my mother was a mammal. My grandmother was a mammal. Their ancestors were mammals. They all got stressed too. Aw shucks. I suppose I got it from them.

Time to Brake

All of this can be a lot to digest. But I hope there’s some good news just around the corner. For me, beginning to view these issues through the lens of stress has opened up a whole new way of working with them.

- If depression is a stress response, then it’s potentially reversible. There’s stuff I can do for myself, with or without the medical profession.

- If depression isn’t a stress response, that still isn’t the end of it.5 6 Stress affects virtually every system in our bodies. So maybe I can free up some energy for coping or healing simply by learning more about how the stress response works and then tipping that balance in my favor.

The next offering in this series will propose a framework for understanding where all this stress response is coming from. It’s always tempting to blame the identified patient, e.g., you’re not resilient enough, so work harder on your wellness tools. But I’d like to push back a little. When you look at the research, there’s a really good case to be made that “stress” is actually driving depression. If so, this begs the question:

- Why are so many people in modern society stressed to the point of incapacity?

- Why are we feeling so helpless and hopeless that our bodies are concluding the best we can do is just lay down and die?

- What about modern society—and the options we are giving each other—is generating such resoundingly lethal impressions?

If you’re like me, you may be surprised to realize how much you’ve been up against. Understanding that has helped a lot. I no longer feel like I’m doing something wrong or that breaking down is all about me.

Also, forewarned is forearmed. Now I can think more strategically about the defenses I use to protect myself and my future from some of the pitfalls of mainstream thinking and modern living.

If you don’t want to wait until then, let’s start talking and working on these issues together. How about Sundays at 4 PM Eastern? The join-up information is below:

REVERSING THE STRESS RESPONSE

Sundays 4-5 PM Eastern

- Join by computer or smart phone: https://zoom.us/j/119362879

- Join by phone (US/Canada): +1 669 900 6833 or +1 646 558 8656 (Meeting ID: 119 362 879)

- International callers: https://zoom.us/u/jkwt3wHh

“The business of psychiatry is to provide society with excuses disguised as diagnoses, and with coercions justified as treatments.” – Thomas Szasz

Report comment

All too often, so painfully true!

Report comment

Every field has its own jargon/terminology. For my sake Folks, please keep it simple or I wont want to listen to you for very long. I understand the word “depression” to mean some heavy duty unhappiness and/or sadness that there are no pills for. When I was chronically immobilized, I finally bought a book that suggested I force myself to do things I didn’t feel like doing.. This was so hard that I had to force myself, to force myself, to do things I didn’t feel like doing. I did this for a time and one day I noticed that I felt sexual feelings that had been dead for decades. I was happy…I felt good…

The medical model is creepy and sleazy and rampant capitalism is sinister: neither make me feel very good. I am tapering off some chemicals that have damaged me. Please keep it simple or you folks can’t be my friends.

Report comment

Great as usual, Sarah. I love how you make *being human* the issue, given that is what connects everyone. Indeed, the epidemic du jour is extreme stress, and there are a plethora of potential causes. That’s a great place to start, by reducing stress. Not just our feelings shift from this awareness, but also our perspective. High stress can cause us to distrort things, it is a filter through which we perceive. We can take some control here.

“‘Oh, I’m having a rough time and my stress is too high. What do I need to change?’ That shift alone brings the stress down several notches.”

When I work with people as an energy healer and teacher, first thing we talk about is “coming back into alignment,” when we feel overpowered and paralyzed by stress. There are a variety of techniques to assist this process, but it’s really about knowing the difference–on a feeling level–between being in our center vs. out of our center, without any judgement whatsoever about it, as this is most universally human. We all go in and out of alignment, that is part of life’s journey, and also an aspect of the manifesting process.

Getting back into center is a matter of shifting our focus to feel relief from the stress. I do believe we are wired as humans to allow one state of being to shift into another, which is a gift because we don’t always feel in control, as you talk about. But also, this is a practice we can employ ourselves, concsiously and at will, and it serves to shift neural pathways aka neuroplasticity. We can shift so much internally this way. That, alone, changes the landscape of our perceived reality in an instant.

Making the priority to consciously come back to center (stress reduction) before doing anything else can lead to radical changes, based on helping the world come into alignment. After all, we are each a part of humanity–each one of us a unique aspect of it–no exception. Nature will always find its way back to balance, and we are natural beings. One way or another, we “know” to come back into balance.

When we fight this, we are fighting nature, and that is an extreme struggle which brings with it chronic stress. When we come into alignment, we cease to struggle with our own nature, and that is a HUGE relief!

I find it to be amazing work–paradigm shifting, in fact. New ways of thinking come from this, far and away from the toxic mainstream. Thanks for the inspiration!

Report comment

Thanks Alex. Really appreciate the work you are doing and how you articulate it. For me, in terms of the stress response, you’re describing the difference between living from fear-driven reactivity (essentially where the experience of threat activates the Gas Pedal response of the sympathetic system and Brake responses of the parasympathetic system) and living from the trust-based potential that is at the core of the parasympathetic system. As a modern world, I suspect we’ve been so mesmerized by the power and control capacities of sympathetic activation, that we’ve largely overlooked (and failed to develop) the incredibly healing capacities of its quieter and far more faithful neighbor – the parasympathetic system. The more I learn about that system, the more impressed I am by the human body and it’s inherent capacity to heal – physically, mentally, spiritually, socially – if just offered something – almost anything – worth letting ourselves trust in as an organizing principle for existence and well-being. More on that later in a future offering. So glad (and grateful) that you’re doing the work you’re doing!

Report comment

Excellent! And all so very true to my mind as well. Fear-based vs. trust-based would be not aligned vs. aligned.

I use the Chakra system as my orgainzing principle, based on energy frequencies and how we experience our body/spirit connection. How we navigate our emotional responses is central to this because it is how we know our spirit.

From how I am understanding sympathetic and parasympathetic responses from your writings, there seems to be quite a bit of overlap–certainly the very same principles involved, that we are naturally self-healing beings. I believe that is our power, including to make change.

And indeed, we’ve gotten into some bad habits based on all that programming we took on at different levels (family role, social expectations, advertising propoganda, etc.). I think what you are doing will help to reverse this, and get us back connected to ourselves. That busts up the programming right there. That has been the exact focus and purpose of my work with myself and others.

I am excited about your work as well, and I look forward to reading more! Really great stuff, Sarah. There is good strong light here, I have no doubt.

Report comment

So much of this reminds me of experiences I’ve had over the years, that I’ve only just begun to understand in the last few years, having discovered the sources you’ve linked to, among other things. It’s uncanny when I find out that what I took to be just my weird behavioural tendancies are actually revealed to be part of our natural defense mechanisms. . . that made me feel a lot less freakish & abnormal, I know that for sure!

If you haven’t discovered the work of Dr Gabor Mate on trauma & its effects, I’d highly advise checking him out. His perspective links in with the stuff you were talking about, & has been as much of a revelation to me, as this info has been.

Report comment

Thank you so much Fern. I’ve only connected on a surface level with Dr. Mate’s work. I totally admire what he’s done in the field of addictions. Will look more into his work in areas like this one.

Report comment

This is brilliant reasoning. And it makes perfect sense, in light of my own mental health history.

Report comment

Thanks so much for reading Linda Lee Lady Quixote!

Report comment

Almost TLDR! Don’t take this the wrong way, Sarah, but 1/2 way through, I found myself confused! I kept asking myself, “WTF? is she talking about!?”…. I’m stressed out right now, from helping my friend. She’s a trauma/abuse victim, and is being grossly over-drugged and gas-lighted by the local “community mental health center”. The psych DRUGS are doing her more harm than good, but she’s court-ordered. She lives in subsidized housing, on disability, and a homeless meth-head/addict has moved in on her, and is taking advantage of her. The police are now involved, and she should be ok soon, but…. I’m stressed out! I’ll go for a long walk, and listen to some soothing tunes….and smile, and be glad and grateful thjat I’m at least rid of the pseudo-science lies of the drug racket of psychiatry! And c’mon, you know the DSM-5 is really only a catalog of billing codes, full of invented “diseases”! I’ll read the whole thing later, it’ll make more sense then….

Report comment

Bradford – thanks so much for the work you are doing in caring for your friend. Sorry to add to the stress by my writing. Absolutely agree with your assessment of how stressful and counterproductive systemic ‘interventions’ like you’re describing can be. Hope to say more about that – and the systemic and mainstream culpability in perpetuating the kind of suffering you describe- in future offerings

Report comment

Please let me clarify, Sarah! I’m stressed out, yes, because I care about my vulnerable friend. (I forgot to include that her Mom talked her into getting Electro-Cution Torture (“ECT”) years ago, and there’s a subtle but real “echo” of the neurological damage that most people miss because she’s also over-medicated on heavy neuroleptics.) The local CMHC is doing her more harm than good. She’s in rougher shape than when I met her years ago. I got free of the system over 2 decades ago, thank God! But in my present state of mind, I’m needing to walk miles a day more, for stress relief. And what you’re writing is just to confusing to me, to wrap my head around! I sense that you’re on the right track, when I read it. It’s so hard to put some of this stuff into words, I get that! It was more a report on my current, – TEMPORARY – head state! I’ve learned that all states of mind and emotion are transient, temporal, and they either get better or worse, eventually. Then you die. So why not choose to be happy, anyway!? Happiness is a choice. The more we practice to choose happiness on a daily basis, the more it becomes our default state of mind. We truly are as happy as we choose to be. The more we spread our happiness to others, freely given, without thought of return or reciprocity, the more our natural state of happiness manifests inside. Who I AM, and who I consciously CHOOSE to BE, drives my emotional state. No longer does my emotional or mental state determine who I am, and how I behave, and what I do. We all have far, far, FAR MORE power and control over our minds, thoughts, feelings, and emotions than we’ve been led to believe. It’s SO SIMPLE! (Just because I find your writing a little intellectually complicated for my Winnie the Pooh brain, is MY problem, not yours! )

@GRIN@

Report comment

I love this! Finally a hands on, first person approach that makes more sense than anything the mental illness machine has been plugging. Thank you for this logical and factual presentation to give me permission to see my reactions as defense and not “mental illness”.

Report comment

Thank you squash! Really grateful for your feedback. My hope in writing this was to pretty much do exactly what you said in your comment. I want to feel less alone and more like my experiences make sense to me and others. In addition, because words often fail me when I need them the most in this frame of mind – and also because even when I have words, others mostly don’t listen to me long enough to really explain what is happening, I am hoping to offer something that those of us on the ground level who have to live this stuff every day can take with us – to family gatherings, medical appointments, community meetings, employee assistance, and just hand to them and say – this is what I’m experiencing! Read it. Then stop patronizing or labeling me, and help me with my real problems!

Report comment

Wow, thanks so much, Sarah. I love that you take the language of psychology and break it down with a very clear analogy to explain what’s going on. As I read, I thought about many years ago when I was in an out-patient program and met a woman who was catatonic….it seems to me that maybe catatonia fits into fright. But instead of any kind of holistic treatment, she had some ECT treatments and then got “better.” I could cry at the thought of what might have been for her had anyone seen her in a different light.

Yes, we all have agency and are not at the mercy of imbalanced brain chemicals. Keep writing to create a new paradigm!

Report comment

Thank you so much annieblue. so grateful to you for seeing and pointing out the possibilities inherent in seeing things differently. Will cry with you and share in the pain of the millions of stressed and traumatized souls we have lost and are losing to some horribly harsh and dehumanizing ‘treatments’ in the name of ‘healthcare’ and ‘medicine’

Report comment

HI Sarah. From what I’ve seen of your work you’re sort of stuck in one (or more) of those familiar patterns resulting from trying to understand your issues using a “mental health” paradigm. Though you realize on many levels that psychiatry is not only problematic but completely bogus, on another level you still obsess on the minutiae of labeling/”diagnostic” language and conceptualizations, which to me indicates that, while you understand intellectually that “mental health” is a bankrupt ideology, you can’t quite cut that remaining thread on an internal level and free yourself.

Why do you need to label your feelings in the first place? From what I can see they’re perfectly normal reactions to a culture and political system at war with life itself (this is not hyperbole). As a living creature instinctually wired for self-preservation you react to this in all sorts of ways meant to warn you of danger. The purpose of psychiatry is to perpetuate that system (yes, we call it capitalism) and suppress that perception of danger, which if left unchecked could lead to resistance, rebellion or even revolution. The idea is to convince you that the problem is not collective but within you, and that your resistance/rebellion are “symptoms” of an internal flaw you need to “work out” (suppress) rather than dealing with the systemic, i.e. political, source of the problem, which is not good for business.

“The psychiatric system cannot be reformed but must be abolished.” 🙂

Take care.

Report comment

Yessssssssssssss! Hopefully will be getting closer to the points you are making here, and the research that (I believe) supports a fundamental paradigm shift in our way of seeing what we are up against as a human community, in the next offering in this series.

Report comment

You already have your finger right on the crux of the matter with your realization that you are simply dealing with what it means to be human in an oppressive system. And I think you get that all these so-called “skills” are simply aspects of our own humanity from which we have become alienated, and sold back to us as commodities.

Though I hesitate to bring this up for a number of reasons, this inability to fully embrace the truths he articulated so well led to Matt/BDPTransformation allowing the mythical “expertise” of mh pros to negatively influence his outlook on life, with tragic results. I think it’s a lesson that has been largely ignored in the professionalized milieu of MIA.

Report comment

Oldhead – I’m hoping that eventually I’ll become humble enough to hold your point ever present in my mind. And also humble enough to hold a heathy regard for the power of overwhelming despair to decimate any of us. My main hope for now is simply to appreciate the energy the day gives me and use it to live values that, I hope, based on my experience and observation to date, could possibly change the world for the better. If I’m able to do that until the day the universe calls back my borrowed breath, then I suspect it will have felt to me like a good life. If I get to the place where I feel it necessary to surrender my borrowed breath by my own hand, then I hope that surrender will free up resources, possibilities And inspiration for others to carry on with their vision of a better world in my absense

Report comment

Resources are infinite, there’s no way you could hoard them if you tried since (as Wayne Dyer might have said) Source is infinite.

I don’t usually think in these terms btw, something here is sparking my tendency to free associate.

Another thing running through my mind is Dylan’s line, “For them that think death’s honesty won’t fall upon them naturally life sometimes must get lonely.”

(Also from the same verse: “Money doesn’t talk, it swears; obscenity, who really cares; propaganda, all is phony.” )

https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/bobdylan/itsalrightmaimonlybleeding.html

Hopefully someone will find this pertinent. It’s a great song anyway, check it out.

Report comment

Oldhead,

Wayne Dyer saved my bacon.

Report comment

Thank you for this; it’s incredibly helpful. I can’t even begin to describe how much of a relief it is to know that others have experienced such similar reactions. Lately I have been looking into theories of depression as evolutionary adaptation but this goes beyond that – as a “patient” for 30 years now, I am finally understanding that I am not “ill”, not crazy or built wrong – but reacting and adapting to circumstances. Like you said above, it HELPS to know what’s really wrong, that alone relieves some of the stress.

Report comment

Thank you so much for sharing this. It took me two months of ups and downs and self struggle to give Birth this piece and connect with the parts of my experience that seemed to want to speak these ideas to others. I couldn’t hope for more rewarding feedback than what you just shared

Report comment

WOW!

I will never forget the day you explained some of this to me on the phone Sara and my whole body was resonating with it as the truth.

I instinctively knew it then and absolutely understand now (sans some of the complexities that require further unpacking for me to connect all the dots – but that make sense nonetheless.)

It is basic biology, it is largely in our control and manageable and once we grasp it, it frees us.

Adding ‘free” to the F’s seems appropriate in that after we’ve come full circle through the ringer of life, dispelling with the “mysterious unknowns” of theories that make no sense because they, omit, divorce and dismiss the human body as irrelevant, when it is the very environment where we live out every experience that makes up LIFE, are anti-life… pieces of this and that, that lack a coherent, holistic, comprehensive reality that includes and see and treats ‘us” as living breathing, entities who are attacked by virus’s and pollutants, who break bones and tear skin, and struggle to comprehend the incessant stupidity and cruelty of others, and moment to moment shift our weight to achieve the comfort of peace in our skin.

This is part of the missing link- a BIG part, the genesis, the starting point from which we can wipe the dirty slate clean and see with fresh eyes why some people’s version of help, couldn’t possible be true simply because it is harmful to so many. What is broken here is those flimsy, disconnected inhumane, for our own good theories. May they rest in peace.

I love it. Thank you for all you have done to clear the way.

Judy

Report comment

Oh year and the addition of “Free” is a master stroke. I’ve listened to fight, flight, freeze, floppy etc but Freedom is what we are looking for isn’t it? Not f…ing diagnosis

Report comment

Yesss-whisperquick- love that addition of free . It’s brilliant. Thanks for your resonance and amplifying this direction

Report comment

Judy, I love that you add a 7th F. Free free free. Yes , can’t wait to develop that more as part of the solution. In the Meantime what you write here should be a blog in its own right. Thanks so much for commenting

Report comment

James Hillman, Re- Visioning psychology, Suicide and the soul. Manufacture of madness.

I am not searching for non existent cure or hope. Because I am not interested in naive theologization of psychological reality. I am looking for the truth. Hope is not even a logic assumption. Hope is not an psychological term, it is theological naivety.

————————————————————————————————————

Psychological truths are incurable. They can change or they can kill you.

Apollonian ego never will admit that in psychological hierarchy they are those who are furthest away form the psychological truths.

—————————————————————————————————————

Thelogization of the psyche is sin against humanity.

Apollonian hegemony over psyche is a sin against humanity.

Theological,medical hegemony over psychological hades is the end of humanity.

JAMES HILLMAN RE – VISIONING OF PSYCHOLOGY.

Report comment

Love that you explore the spiritual implications of psychology, our current approaches to these issues and point out the need for radical transformation. Amen

Report comment

I wonder if a lot of the fear I have today from just living in the competitive world, are not magnified many times by the childhood fear of abandonment, which I don’t consciously remember. Very interesting article.

Report comment

Great observation. And one That fits for me – and rings true in my experience. Also I suspect that, for me, the mainstream norm of pitting us against each other to compete for basic material, emotional and social needs that none of us can live well without goes a long way toward making abandonment a rational fear, rather than an irrational one

Report comment

Sarah, this is a fantastic article. Congratulations. I have struggled with this traumatic immobility and berated myself thoroughly. Somewhere I know my energy is locked up and the brake and gas pedal metaphor completely got me. I went from an involved active human to feeling like a rat in a round cage and now paralysed through not being able to find the way out or through. I’m interested in Lucy Johnson’s PTM Framework and am hoping to find some answers in that by attending a workshop. Bottom line is you nailed it for me in this article on every level. Thankyou so much and I would love to join the discussion.

Report comment

Thank you so much Whisperquick. So sorry that you know this place well enough to describe it as you do. Yes, love the PTM Framework and where they are trying to move the conversation. Hope the workshop is helpful!

Report comment

Hi Sara,

no nothing is wrong with you or anyone who experiences these kinds of things. The picture of the little bunny and fox says so much. I believe many early childhood abuse survivors view themselves thru that kind of a picture, even if their adults selves don’t realize it.

The ‘nice’ thing about my wife’s d.i.d. is it makes so many things extremely clear. And I still remember the various little girls (alters) telling me how scared each was and how little she felt, and my repeated reply to each was always, “I know you are scared, Honey. But you’re not alone anymore. I’m a big man. I’ve got you now because I take care of my little girls.” And that’s one aspect of how I helped walk my wife thru her paralyzing fear because I inserted myself into her picture of the little bunny and fox until she could see herself with me holding her, and that fox didn’t seem so scary with me in the picture.

In attachment terms they call it proximity maintenance. Mary Ainsworth had a lot to teach all of us in her strange situation protocols. The experts are (finally) beginning to study how attachment concepts apply throughout our lives and not just when we are little children, but pretty much I applied the majority of those concepts that they have identified, that are necessary to produce securely attached, healthy children, to my wife’s healing, and it’s been a godsend for us. Holding her thru that paralyzing fear that she experienced was just one thing attachment theory taught us.

I know each of us likes to view these issues thru various prisms like classes, ‘races’ economic structures, etc, but for me I see so much more relevance in the breakdown of family and social structures. There will always be a ruling, oppressive class to some extent: there always has been throughout the history of humankind, but when the family units and social structures are strong, they enable us to faces those adversities because we know that we are never truly alone in them like that little bunny facing the fox: someone actually is holding us and keeping us safe.

Sam

Report comment

Thanks Sam. Really glad for the healing work you and your wife have been able to do as a family. Remarkable that you were able to learn and apply attachment theory and discover from there some healing ways to be be together. Much to be proud of for both of you.

Report comment

100% true. I’ve considered the threat response one of the Five Causative Factors of supposed mental illness for some time now. Please check out http://www.HarperWest.co for my paradigm for reframing mental illness as normal, adaptive responses to fear/threat, shame, fear of social exclusion, chronic and attachment trauma. I can share a journal article I’ve written based on my book Self-Acceptance Psychology. Keep up the work on this topic.

Report comment

So If “mental illness” is “supposed” (i.e. false) how can there be “causative factors” of something that is nonexistent?

Report comment

I meant it is not “illness.” This term is inaccurate. But there can be causative factors of emotional distress, as I listed. This is well-researched and I list those sources in my book. The research on trauma and attachment trauma is extensive and shows high correlation to emotional distress.

Report comment

I’m a grouch due to iatrogenic illness/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome linked to long term psych drug use.

Report comment

can relate Rachel

Report comment

Really glad to know of your work Harper. I’m sure that taking this path as a practicing professional has required a lot of original thinking and breaking ground. Grateful that you’ve done it.

Report comment

Otter paws and purple hearts Sarah. Many thank yous. I’m so glad I glanced at the clock and did the call in thing today. We’ll talk again soon. (my ground name is Jane) 🙂 <3

Report comment

Thank you so much Jane! Really glad to be in touch.

Report comment

I had been in fight or flight response for my entire life. It showed up as over doing everything the acceptable social behaviors while I was an alcoholic behind closed doors to deal with the stress. Just a few years ago my trauma showed up and I collapsed body mind and spirit. I’ve completely let go of all the doing and feel in my body and feel present. I’ve done somatic experiencing and embodiment work.

The issue now is I feel no motivation to do anything. I don’t want to work, I don’t feel passionate about anything. I don’t feel depressed though. It’s just meh. I definately feel like I could never go back to a high powered job or stressful job or any kind of hustle. That is just out of the question.

I don’t have any triggers anymore. My nervous system is calm and I avoid people and situations that would rev it up. Is this my new normal? Just Zen all of the time or is there something wrong? Is it possible I damaged myself permanently? I still feel like I should be doing something. I’ve always been a person that was motivated and took action. I haven’t really read much around this. I’m wondering if my system went in the extreme opposite direction now. Thanks for this article!

Report comment

Great first step Sarah. I appreciate your work.

Report comment