The worst interview I’ve ever done — or the best, depending on how you look at it — was in early 2016, on the phone with a guy named Ron. All I knew about Ron was he had some affiliation with a defunct magazine I was researching and he lived in California. Ron had asked that we speak in the evening, his time. Out in New York I spent my day as I did then, alone in the apartment reading, probably anxious about having a late call, an interview no less. Finally at the appointed hour I dialed Ron.

Though plenty of times now I’ve picked up the phone and interviewed strangers, I can’t say it’s gotten any easier. I’m not a journalist by training. I have two degrees in what’s clumsily called “creative nonfiction writing.” I think I was attracted to the genre because I liked being alone. The father of the essay, Montaigne, literally lived in a tower. In recent years, though, I’ve taught myself to talk to strangers, both on the phone and in person and at some point realized I’m a reporter, a journalist.

What I know of journalism I mostly learned the years I was an editor for BuzzFeed News. BuzzFeed was a small-ish start-up when I started there in 2013 and something else entirely by the time I left in 2015. I was part of the initially two-person team responsible for features, stories over 5000 words, written by freelancers mostly. They took months or sometimes years to produce. They were narrative and nuanced and fact checked. When I told literary types at parties that “BuzzFeed” was where I worked, they’d sometimes laugh right in my face.

In some senses it was a silly place to work. Hanson dropped by once. I went to the kitchen for seltzer and bumped into Ice-T. I’ve met Grumpy Cat and Lil Bub (twice). But my favorite parts of the job were the serious parts, the hours I spent working with journalists — foreign correspondents, data wonks, reporters who covered war, corruption, sexual violence. I learned a lot from being around these people: perfectionists, nerds, folks with a strong belief in fighting injustice. Ones who’d be furious if they realized they got one tiny thing wrong. Let alone something key.

I say all this to say: I know enough about journalism to respect the hell out of it. I know enough to know it’s important to check your facts, to pursue truth relentlessly, and to also check your biases. And, in America in 2019 especially, to follow the money. To think about: who’s paying for me to think this, or to think that? Who’s paying for me to assume something or another is a given, when it actually is not?

That evening, when I finally began my interview with Ron, I could sense something was going terribly wrong almost immediately. During an interview I tend to tell people a little about myself and my work — I usually mention how I’m a literary nonfiction writer, so I work slow, and I sometimes explain I got interested in all this because of working on a book about my Uncle Bob. Then I usually give a very open-ended question, like, why don’t you take me back in time, tell me about how you came to be involved with yadda yadda. That night I asked Ron a general question about his involvement with the defunct magazine I was interested in.

But Ron didn’t want to talk about that. Instead, he began talking about something else entirely, a feature story I’d published the year before on BuzzFeed, right before I left the company. It was a 8000 word piece about a woman in San Francisco who was shot by the police. Hearing Ron say the name “Teresa Sheehan,” my pulse shot up.

Ron began discussing specific errors I made in the story. He leapt from mistake to mistake, unpacking one for a bit, then moving on. I was confused and then stunned and deeply embarrassed, but also, on some deeper level, I was really relieved.

I looked out at the night, at the city’s lights and the bridges. I looked, too, at my own reflection on the glass. I watched myself nod and listened as Ron spoke.

* * *

Back in the spring of 2015, I had been at my desk in the BuzzFeed newsroom, consuming a salad and Twitter, when I read about a Supreme Court case called City and County of San Francisco v. Sheehan.

Teresa Sheehan was a woman who lived in San Francisco’s Mission District in housing for people with disabilities. Her diagnosis, I read, was schizoaffective disorder. One day in August 2008, police were summoned to her room by a social worker; apparently she hadn’t been taking her medications for some months. She was shot either six or seven times by an officer who arrived on scene. She was arrested for having allegedly charged at police with a knife. Teresa said she used it to cut fruit.

Teresa clung onto life. She was brought to trial a few months later. The jury was hung; the city decided to not re-try her and dropped the criminal case. Her family then filed suit against the city. Seven years they’d waited for a single day in court as the city had appealed and appealed. Now they were headed to the Supreme Court, and hence the case had gotten a little media attention.

The question the highest court had agreed to review struck me as quite important—especially if the court were to side with the Sheehans. Namely, when a police officer fails to appropriately respond to a situation involving an individual who’s been psychiatrically diagnosed, are they in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act? Reading about all this, I felt suddenly something like guilt, guilt that I knew this was an important story, one I could write.

No, one I should write.

Back then I didn’t tell anybody about the project about Uncle Bob, which I’d been working on for five years to that point. I regarded it as a secret, this Word document I’d wake up early to visit an hour before I walked to the train. Back in 2009, when I was just starting grad school, Bob mailed me his autobiography, which he’d typed on his typewriter. On a cover page he’d described it as a “true story” about being “labeled a psychotic paranoid schizophrenic.” We spoke on the phone a few months later, once I’d finally read the whole thing. He said he wanted to get the story “out there” because it was “true.” For a few years after, I had quietly worked on a piece of writing based on what Bob sent me. I didn’t know what I was writing, or why, and kept mostly to myself about it. It wasn’t something I was ever going to try to publish. Even then, I figured nobody would want it. There were big obstacles. For example Bob and I had discussed the very real problem of the many other people in our family who’d likely be greatly aggrieved if anyone were to try to tell this story publicly. Then there was the issue of his diagnosis.

Back when he sent me his story a decade ago, I couldn’t have told you what the phrase that he’d typed across its cover meant, “psychotic paranoid schizophrenic.” Soon after I got it, I went down to the university library and checked out whatever books seemed relevant. I stacked them in a pile tall as my apartment door, read through them over the course of the next couple semesters. I wandered around the internet, too, reading anything and everything I could find.

The more I read, though, the less certain I became. I read another cluster of books I found shelved nearby to the ones about schizophrenia, mostly from the sixties — Foucault, Goffmann, Laing. I realized this was a fight, psychiatry versus anti-psychiatry. It was clear that my uncle’s text, generally, was more in the tradition of the latter. I wasn’t sure who was right. In my own piece of writing, I didn’t include anything else that people said, only what Bob had to say about himself. All I focused on was presenting his story as vividly as I could.

But by the time I moved to New York in 2013, the project felt basically dead. I ignored it for more than a year, more concerned with getting a lease, getting a gig, making rent. I’d occasionally find myself making small talk with someone who worked at a publishing house or a literary agency. I’d describe the project, a nonfiction piece based extremely closely on a document written by my uncle, who was a self-identified “hermit” who lived in the desert and had been diagnosed with schizophrenia at sixteen. A nonfiction book written in two fonts with aliens and a misspelled title. People would frown, or even laugh. A friend’s boyfriend who worked in an agency read some pages, and told me if I ever tried to sell it, it’d have to be called fiction. (That, I knew, I’d never do; it was extremely important to Bob that his story be understood as “true.”)

Then three things happened, all of which I did not see coming: In the summer of 2015, Bob died. Grieving, guilty I’d not tried to do so sooner, I decided to try to find a literary agent. All I’d ever heard basically was that finding an agent is impossible. How you’re supposed to find one is you send them pages. I instead emailed a few and asked them to coffee. I was doing a lot of online dating and think I’d become accustomed to making small chat with strangers. Six agents I spoke with weren’t much interested in this project I described about my uncle.

But then I met the seventh; our meeting electric. We spoke about his family and mine. I saw he got it, he got that this did matter. A few months later I got up the nerve to send him a few chapters and he called me and said “You’re going to remember this call for the rest of your life.” I signed with him.

That same month, I read about Teresa Sheehan. As I did, I felt my insides stir. I yearned to understand how my piece of writing about Bob fit into some greater scheme. I knew as well that if this agent was going to find a publisher for my book, I might be expected to weigh in somehow on this topic that continued to confuse me, “schizophrenia.” In some sense I dreaded he might succeed in finding a publisher, as I was entirely unsure I was up to the task of writing a book on this topic. I felt I needed to learn a lot more about mental health, and fast.

The Teresa Sheehan supreme court case, this was perhaps reason enough to justify me writing a big feature story about mental health, or at least I hoped I could convince my editor, also my boss, of this fact. I did genuinely want to know: How is it that police have become the people who respond when someone like Teresa Sheehan needs help? Why are bullets what our society has to offer her — even in San Francisco? I grew up just north of San Francisco. It’s the first city I loved. It’s a region full of people who believe themselves liberal and also good.

I chatted with BuzzFeed’s Supreme Court reporter about the Sheehan case. I revealed my interest in writing about it because of a longer project I’d long been working on about my uncle. I probably said he “was schizophrenic” or “had schizophrenia,” and when I said the diagnosis aloud, I was probably uneasy, unused to vocalizing this word I’d typed countless times.

My colleague said it seemed next to impossible that the highest court would side with the Sheehans regarding this ADA argument, given our courts’ attitudes towards police liability. He guessed the case itself would be of no legal significance. In other words, from his vantage, there wasn’t any good reason for me to write about it. I told him I understood.

I walked back to my desk and nonetheless convinced my boss it was a good idea for me to book a ticket to San Francisco.

If I didn’t write about this, I felt, nobody would.

* * *

Two of Teresa Sheehan’s sisters welcomed me into a modest but warm apartment on the city’s foggy western side. They poured tea and served little Hawaiian desserts. They told me about their childhoods on Okinawa, showed me pictures of their relatives in Japan and America. They told me about Teresa’s youth and teenage years. They described how brilliant she’d been, how academically adept. They described how she’d gone off to college but at some point after had been hospitalized for the first time. How she didn’t finish college but they didn’t know what happened, really.

They talked about how in their family it wasn’t openly discussed, whatever was going on with Teresa. Their parents aged; her sisters attempted to step in, when it came to Teresa’s care. But they were up against a lot. They told me about Teresa’s thirties, her forties. Her sisters described how Teresa would be fine for a while — living somewhere, working somewhere. But then things would start to unwind, and then perhaps she’d stop getting out of bed for weeks, months, and they’d get in an argument. Or she’d go missing.

Details of Teresa’s life reminded me a lot of my uncle Bob’s. Teresa and Bob were almost the same age, and Bob had likewise spent much of his life in the Bay Area. The dynamics between Teresa and her family reminded me of those between Bob and his family, as well. As did the dynamics between Teresa and society as a whole. So much of my Uncle Bob’s “true story” of his life was actually his commentary on society — and psychiatry.

Teresa’s sisters described driving around at night, searching for her. They wept, acknowledging that they had no idea how truly horrific Teresa’s life had been. However bad it was before August 7, 2008, then came the six or seven bullets; it was never entirely clear how many there were. However bad it was before, then came the seven years that had followed — for Teresa’s family, and for Teresa.

Before I flew to San Francisco, Teresa’s sisters said it was unlikely Teresa would want to speak with me for my story. They said I shouldn’t be offended, that she refused to talk to most all people. That morning, they had called her and asked if she’d join. They offered to pick her up from where she was living now, in the Tenderloin. They said she’d very politely declined. They always emphasized how polite she was. They apologized to me but reiterated that she really didn’t like meeting anybody.

We spoke for hours. At some point I told them I wasn’t a journalist anymore, just a person. We talked about their lives and mine. One of their daughters came by. They roasted carrots, chicken, they opened wine. I went back to my hotel and got into bed and sobbed and sobbed and sobbed. I sobbed for Teresa and her family. I sobbed for my uncle Bob. I had sobbed for him before but that night I felt myself committing to him, to his task, to an extent I’d probably been avoiding. I sobbed I think because I knew that I was only beginning my journey, learning about the truth of schizophrenia.

* * *

Back in New York, I read more into the story of how police had become the people who are called when people experience psychiatric distress. I hired a freelance data reporter to answer a question I believed was critical to the piece I was writing: What percentage of those American killed annually by police have disabilities, including psychiatric disabilities?

By now I was reading the likes of E. Fuller Torrey and Pete Earley and Susan Sheehan’s Is There No Place on Earth for Me? Together, these books described a present day mental health catastrophe, one in which psychiatric care has been cut to nothing through the last half century. One in which these days, people with severe mental illnesses are much likelier to be homeless, to be incarcerated, and to be injured or killed by law enforcement.

I interviewed Teresa Sheehan’s childhood friends on the phone. I spoke with more of her family. I spoke with her attorneys in the civil case. I spoke with her former public defender, and others who were around during those very hard months right after the incident. We spoke about logistics like getting Teresa clothes for her court appearances or whether her bullet wounds would become infected. I spoke with people from a support group for families of those diagnosed with mental illnesses, the National Alliance on Mental Illnesses (or NAMI). Some had sat through Teresa’s trial. They spoke to me about how stigmatized these diagnoses are. They lamented the lack of funding for mental health care.

I called the city of San Francisco and the police, got a lot of secretaries and PR reps and eventually spoke with representatives from various offices. I spoke with police officers who’re involved with an effort to further train law enforcement in what’s called Crisis Intervention Training or CIT. I tried to contact the officers who barged into Teresa Sheehan’s room, the one who shot her. I didn’t hear back from them. I knew they’d have no reason to want to talk to me and perhaps were barred from doing so legally. I’d likewise tried and failed to speak with the social worker who’d summoned the police that day. (Many who work in health, including mental health, are barred by law from speaking with journalists because of patient privacy law.)

Another group of people I now spoke with on the phone were relatives of people with psychiatric diagnoses who’d been killed by law enforcement. Children, fathers, siblings told me about their someone with pure joy in their voices.

They spoke about the years in and out of hospitals, and then the bullets, the taser, the jump. They described what came next. No coverage. No justice. No compensation. Or if they got a day in court, how the kinds of attorneys who take these cases take sometimes 70%.

They described their dismay at how little officials, departments — our society — care about this.

* * *

Something bothered me, though. I didn’t like that I hadn’t spoken with Teresa Sheehan. Her sisters had said that Teresa didn’t want to speak with me. Still, I wondered whether I should try to find another way to ask her this question — whether she’d talk to me. I thought about how to find her. I considered walking through the Tenderloin asking people if they knew her. But I knew doing so, if it worked, would seriously breach my trust with the Sheehans. There was a possibility I’d get to talk to Teresa later — let’s say the Supreme Court decision was really unexpected in some way. All the time this bounced around in my brain. I hated it, the fact that I hadn’t actually spoken to Teresa Sheehan.

Something else that bothered me was a single interview I’d done that was different than all the others. It was with two women from an organization that said they advocated for psychiatric patients’ rights. When someone was put on a 72-hour psychiatric hold, for example, they’d try to get a representative there to advocate for them. They were especially critical of psychiatric medications.

I wasn’t sure what to do with this point of view, or how it fit into everything else. Though it was actually a point of view, broadly speaking, that I understood very well, having spent five years closely reading Bob’s text. I knew where Bob stood when it came to such topics as the psychiatric hospitals he’d been held in, and the medications he’d been made to take. I knew where he stood on the topic of his diagnosis and on the perception that society as a whole has about people like him generally. I knew where he stood on the question of whether pharmaceutical companies were murderers and liars and thieves, and the public complicit.

In the days leading up to the publication of the Sheehan story, I privately panicked about questions that felt both small and enormous. What exactly was “schizoaffective disorder,” for example? On WebMD the diagnosis was discussed confidently. Likewise in the manual written by the psychiatric profession, the Diagnostic and Statical Manual or DSM, it was discussed at length. But then if you read further (I knew because I had) it became clear that these diagnoses were hypothetical. That these categories were created by psychiatrists by committee. Not proven in labs.

Whether they referred to anything real was a matter of contentious debate. On the one hand there was what psychiatry (and all of society) seemed to think about “mental illness” and on the other was what people like Uncle Bob said. Though I had realized that many people in fact agreed with the likes of Uncle Bob. For example, for the Sheehan story I’d interviewed Dr. Thomas Insel, then the director of one of the two most important federal government agencies regarding mental health, the National Institute of Mental Health. Back in 2011, Dr. Insel had published a rather famous blog post condemning the DSM diagnoses for their “lack of validity.”

Of course I now wish I’d worked harder to wrap my head around this question of what “schizoaffective disorder” was or wasn’t, or how psychiatric medications fit into all this. Ron for example has explained to me how it’s incredibly easy for someone like me to inadvertently make decisions that reflect big biases we hold, however consciously. I told him I don’t have an excuse for my choices when I reported the Sheehan story. But at the time I just didn’t realize that it was in fact my job to take the point of view of people who’ve been psychiatrically diagnosed very seriously. For one I wasn’t certain Uncle Bob and everyone who felt like him was right. But more honestly, I was terrified of appearing to challenge the profession of psychiatry. Back then I was too nervous to even talk to my editor or the copyeditor about my doubts.

My feature about Teresa Sheehan published in July, 2015. I told myself I was pleased with how it came out. I liked that it carefully told a story about a woman and her family and how our state and society have treated them all. The following October, I read that the Sheehans finally got a million dollar settlement from the city of San Francisco, though they likely got much less than that.

In answer to that question — what percentage of people shot by police have psychiatric disabilities — the number the data reporter found was 16%. She limited what she looked at to a particular year in California. She examined every case of an officer-related fatality and then scoured police reports and local media for mention of a psychiatric history. I guessed the estimate was low. There were other sources, for example the Washington Post, which keeps count of how many Americans are being killed by police as well as some demographics about these citizens. In 2018, 995 Americans were killed by law enforcement, and of those 210 have “mental illness” listed as a factor. That’s about 21%.

* * *

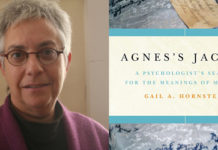

That summer, just as the Sheehan story was about to publish, I got a call: My agent had succeeded in selling my book about Bob. It was the best and worst news I’d ever received.

My new editors said the book needed to have a subtitle. Nonfiction books had subtitles, they said. I gave examples of nonfiction books I like that don’t have subtitles — In Cold Blood, The Argonauts. My editors said the word “schizophrenia” had to be in the subtitle, that way people interested in the topic would know that is what the book is about. I explained that for some years I’d been reading about this topic, “schizophrenia,” and guessed that while the word’s presence there might help attract some readers, it’d certainly repel others. I knew that to some people who’ve been given the diagnosis, a word like “schizophrenic” is just a slur.

Of late, I had been practicing dropping the word “schizophrenia” into conversation, as well. Someone might ask me what I do for a living and I’d say: “I’m writing a book about my uncle, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia.” I’d see how they’d react, like you’d conjured a ghost, or like you’d spat in their face.

But my editors felt it was just too important that the word “schizophrenia” be there. My book is subtitled A True Story about Schizophrenia.

I reasoned that Bob had typed the phrase “psychotic paranoid schizophrenic” across his manuscript’s cover page. His manuscript definitely aspired to comment directly on that label and about the psychiatric system generally. Donning this subtitle, my book now challenged me to rise to this opportunity to comment “about schizophrenia.” I’d never imagined the story might be published, let alone potentially to a wide audience. I now imagined I might try to reach people who otherwise had no interest in this topic.

I quit my job, in part because I could, but in part because I realized I now had a much bigger problem. Now, it was literally my job to understand “schizophrenia” enough to put some information about it down in a book. I’d never known more about it and I’d never felt less certain what to say.

I now spent my days alone at my boyfriend’s apartment, with his bossy gray cat. I opened book after book about schizophrenia and tried to read them. I ended up reading a lot about another group of people, one whose point of view is so well represented in the mainstream press — the psychiatrists. I read the history of their profession, its long entanglement with eugenics, for example. I read about the pills they sell to treat the diagnoses they describe in their books. I read about the histories of those pills and about the other treatments psychiatry has offered people at present and historically. I read Robert Whitaker’s Mad in America. Afterward, like many before me, I found this website, which began as that book’s blog. If I had to pinpoint it, that’s when I finally fell through the looking glass, so to speak.

I read lots of articles on this site, and then books I read about here. I wandered the internet and reached out to people for interviews. I contacted anyone I could find who seemed they might have perspective to lend. I wrote psychiatrists, psychologists, geneticists, asking for interviews. I asked questions like “What is schizophrenia?” I was also interviewing everyone who’d known Uncle Bob, everyone I could find, everyone who’d talk to me. I amassed more and more material, knowing the heaping pile I was creating contained many incompatible truths.

Fall became winter. I left the apartment rarely. I read all the time — on the couch, in the bathtub, in bed. Sometimes I’d force myself to go sit in a cafe for a few hours, and read there. Or I’d schedule a meeting with someone, try to feel like I still lived in the world.

Nowadays people — reporters — ask me how I wrote this book. I have no idea how to answer this question. Lots of trial and error, I tell them. Lots of drafts. Lots of my editors sending the whole thing back and me feeling, basically, like I was starting over again. And crying, lots and lots and lots of crying.

I would look out the window at the avenue, at the river and New Jersey beyond. I studied clouds and sunsets. I thought a lot about Uncle Bob. I thought about him writing his own book at his typewriter in his house in the desert. I spoke on the phone with relatives who knew him well, much better than I did in life. Sometimes I spoke to him. Unlike me, Bob believed in heaven, so if he’s right about that, I figured he heard. I figure he’s watching all of this.

* * *

One morning, more than a year after I published the story about Teresa Sheehan, somebody on Twitter was in my mentions, ripping it apart. He seemed to work in mental health himself and ragged on me first for clearly not having the kind of experience he did. He seemed particularly aggrieved by a passage in my story about a proposed law, what I called the Murphy Bill. I had interviewed one of the representatives behind it, Republican Tim Murphy (an anti-abortion Republican who resigned after it was found he’d pressured a mistress to have an abortion).

Murphy had described the bill as being one that would fund more psychiatric care. I had included some about the Murphy Bill in my piece about Teresa Sheehan because I was bothered by how negative it all seemed, how grim. I wanted to put something in my piece that felt positive, that felt like a way forward. Having spent a lot of time speaking with families of people who’d been killed by police and various professionals who worked with people who’d been diagnosed, a reasonable answer sounded like more funding for mental healthcare. I now see I should have been asking what exactly such funding would yield.

But with my eyes now, reading this guy’s critical tweets, I knew he was right. I re-read the Teresa Sheehan feature with my new eyes and felt guilt in my gut like a stone.

But I didn’t know what to do about it. I didn’t work at BuzzFeed anymore. I couldn’t issue a correction — what would I even be asking to correct? My entire point of view? I couldn’t take the whole piece down. Nor did I regret everything about the piece. I still felt it was very important that people know about Teresa Sheehan’s life, and about her family, and about all the people around her who knew this situation is terrible and want the slaughter to stop. I vaguely hoped nobody would see the story, which was old by now, and that’d be it.

But then came my interview with Ron Schraiber, him enumerating the numerous egregious errors I’d made when I wrote about Teresa Sheehan.

For example, the story had been published with several headlines, as is often done on BuzzFeed and other digital news outlets. One — “The Trials of Teresa Sheehan: How America is Killing Its Mentally Ill” — was offensive because of the phrase “The Mentally Ill.” I’d reduced a group of people to that phrase.

Ron criticized the assumptions I’d made about Teresa — for example that she was wrong or misguided to not want to consume psychiatric medications. He pointed out errors in my understanding of what psychiatric diagnoses are and aren’t, scientifically speaking. He assailed most sharply my decision to discuss the Murphy Bills in any positive light. I’d read plenty more about them now (the Western Massachusetts RLC for example has a good page). I told Ron the truth, that I’d been reading and interviewing a lot more in the last year and had suspected much of what he was now clearly articulating. I felt shame but also immense gratitude.

I should say Ron wasn’t at all unkind during this critique; he really stuck to the page. Editor-to-editor, I appreciated this. He was also delightful to talk to. Ron is one of the most brilliant people I’d ever spoken with, and also one of the funniest. He’s compared his manner of speech to a Joycean stream of consciousness. He’ll toss in impressions and aphorisms and quotes — Audre Lorde, Rodney Dangerfield, the Talmud.

The night of our first conversation, I said sorry to Ron so many times he told me to stop saying it. I explained I’d been reading and interviewing and thinking about all this stuff a lot and I told him I understood that my not speaking to Teresa Sheehan was emblematic of a bigger problem to do with my orientation. That night I said maybe I’d write about the whole incident later so that I could tell other reporters or writers about the mistakes I’d made, maybe for Mad in America. He liked the idea.

We kept emailing and speaking on the phone on occasion. He sent me resources on “mentalism,” a term he taught me, and on the history of the “survivor movement,” as he tended to phrase it. He sent me writings by Judi Chamberlin, Patricia E. Deegan, and Leah Harris. He sent a documentary that featured him and his son, whom he raised on his own and who’s now a geneticist.

My book grew closer and closer to being done, though I still felt uncertain whether the way I’d gone about writing about these matters would suffice. When the text was nearly final, I sent the draft to people who knew much better than I did what “schizophrenia” means: I sent it to people who’ve been diagnosed with schizophrenia. I set it to people who’ve had parents, siblings, children diagnosed. I sent it to folks who work variously in mental health.

One of those I sent it to was Ron. I told him he could and should give me his honest thoughts. I explained to him, of course, the editorial dance is always that and what ended up between the cover represents a sort of grand compromise.

He eventually sent some praise and some very sharp criticisms, particular moments I hastened to excise or change. My editors weren’t entirely pleased that I kept trying to mess around with passages they’d rather I left alone.

I worried about whatever errors I still didn’t see. I fantasized about having another year to write the book, on top of the eight I’d already had. I also knew I didn’t have another year. The book wanted out. I often felt the project had its own gravity. I grasped onto it, like a water-skier behind a speedboat.

In July, 2017, I read the entire book one last time with a pencil, correcting occasional typos. I sobbed continuously. I took the train to the city and handed it to my editor and then I walked back out to the street and for a second wondered what now.

What now is I’ve just continued on. Reporting about mental health, researching, talking with people on the phone, going places and interviewing people or just hanging around. Sometimes when I’m reporting someone will refuse to talk to me. They’ll make clear that they don’t like my kind — journalists, reporters, the media. Which I get. I say that. I ask people if they’d like to talk about what the media tends to get wrong. They tend to have a lot of thoughts.

* * *

I once came across a post on the website about journalism, Nieman Storyboard, which promised to give “5 Tips for Journalists Covering Mental and Behavioral Health.” I admit that the first time I clicked on the article, I didn’t make it much past the headline before I stopped reading. At the top, they’d chosen to include a single image, a black and white shot of a young John Hinckley, Jr., looking menacingly at the viewer, holding a gun. I could pause here and talk about why this choice of photograph is problematic — but I know the readers of Mad in America don’t require such an explanation. I stared at my screen, trying to imagine an organization for reporters publishing an ethics guide about writing about any other group of people and making a choice this offensive.

The article in question had been written after a panel discussion. The panel featured psychologist and several journalists who’ve written about mental health. A psychiatrist was also quoted in the piece whose ties to pharma have been reported on extensively (including on this site). Neither the panel nor the article featured a single individual representing the perspective of someone who’s been psychiatrically diagnosed.

I try to imagine someone, in this era, putting together a panel discussion about how to sensitively write about any other minority group that featured no individuals representing the group in question. And I don’t mean to say, with certainty, that none of the individuals quoted in that piece haven’t been on the inside of the mental health care system. But I do know that it matters if someone’s there representing explicitly and only that sort of expertise. In my opinion, your panel should probably feature mostly if not only such people.

Further, the Neiman Storyboard article, like its panel, failed to grasp that this medical metaphor — mental health/illness — is not universally embraced and is not scientifically proven. That if, in fact, you change that proverbial panel to include not only some but many people who’ve actually experienced “mental illness” or “madness” or “spiritual emergency,” to use a few ways I’ve heard it phrased, you begin to realize the public have allowed ourselves to really only hear one side of a very complicated story. The story we hear, the story the media repeats, is largely one that industry writes.

To my fellow writers eager to chime in about “mental health” and editors editing on this beat: I urge you to work with great humility and caution. Work harder to understand the basics when it comes to the big debates in this space. Resist repetition of falsehoods that began as marketing copy. Stray from stereotyped, misleading phrases, like someone “struggles” or “suffers from” or has “descended into” schizophrenia. Don’t use “mentally ill” as a noun, or an adjective for that matter. Work to understand the very understandable reasons an individual may want to resist psychiatric incarceration and psychiatric treatments, especially coerced ones. Which is to say: work to understand what these treatments actually are.

Mostly: make sure you speak with people who’ve been psychiatrically diagnosed. Who’ve got “lived experience.” My former boss, who edited the Teresa Sheehan story, asked if I’d do it differently, knowing what I know now. I replied that it was an impossible question; I was ignorant then; I am a bit less so now and now of course I’d have written a very different story.

Truthfully, I still don’t feel certain about many of the big questions that writing Bob’s life story has inspired me to try to better understand. But one thing I do certainly feel is that those who’ve been psychiatrically diagnosed have a lot of wisdom to offer the rest of us about what’s really going on in terms of so-called “mental health.” I certainly feel the media’s routine disregard of such points of view is a tremendous, indefensible error.

What keeps those of us who are in positions of privilege from acknowledging that privilege, and how privilege makes us unaware sometimes of crucial things?

Part of it, I think, is that our individual experiences have perhaps lied to us about the greater scheme. Since my book about Uncle Bob published, I’ve been on the road a lot, reading to people, fielding their questions. In my experience, those who are most dogmatically in favor of a biopsychiatric interpretation of things are those who have one intense relationship to a person who’s been diagnosed with a severe mental illness, likewise people who believe they have been greatly helped by a psychiatric treatment. And of course professionals, who’ve maybe spent many years and also probably a lot of money learning what they know and perhaps have had that knowledge confirmed by endless hours working with people who seem to fit the descriptions they’ve read in books.

At my live events, some have sought to challenge me — never people who’ve read my book, but people who assume the book must threaten their realities.

I’ve said to such people: this book honors one man’s truth, or at least aspires to. I’ve written it in such a way that hopefully people with all kinds of beliefs can nonetheless read and enjoy it. Because ultimately I’ve met a lot of decent-seeming people on all sides. A big problem, I suspect, are those who do not care. There are powerful moneyed folks who are profiting off a lot of misery right now and their status quo, I feel, depends upon apathy, upon the misperception that these topics do not affect us all. So I especially tried to write my book in such a way that it might be of interest to people most like I was before Bob mailed me his life story: People who assume this stuff doesn’t relate to them.

A few weeks after my book published last year, I had a reading in Los Angeles. Though I knew Ron lived a few hours away, I didn’t mention it to him specifically; I didn’t want to make him feel like he had to make the trip.

I read and answered questions from the audience and afterward signed books for friends and strangers who came. As happens at my events, people came who had lived experience, who had family in the mental health system, who were professionals. Others confided they didn’t know anything about all this before.

A man in a sweatshirt carrying a manila envelope approached. I realized it was Ron. We hugged. He’d brought me materials to read, some paperwork relating to his psychiatric incarceration, and a photograph of his cat. (Our correspondences often include updates about our respective cats.) I told him it was hard for me to put into words, what it meant to me that he showed up.

Ron has admitted to me he’s not sure whether he liked my book more than he would otherwise because he knows me. He mentioned he gave a copy to a friend of his, to get her less biased take, which I said sounded fair. He said whenever I publish this article, which I admit it’s taken me a long time to finish, he’ll probably comment beneath it, leaving his additional thoughts. I welcome them.

Alexander Sobolev, retired general. He tried to get a huge inheritance from relatives who had died in France, but the Soviet authorities refused him to receive the inheritance. Angered by the actions of the authorities, he refused Soviet citizenship and began to seek exit from the USSR. In 1975, the KGB arrested and placed him in the 9th department of Dnipropetrovsk psychiatric hospital. There his spinal cord was punctured, after this his legs became paralyzed and he died in terrible agony. Relatives under pressure from the KGB refused it.

http://archive.khpg.org/index.php?id=1370526152#80

Report comment

Indeed, increasing the budgets of psychiatry means nothing more than feeding the monster.

But who can blame you for this error in a past article? Nobody, no one can imagine what psychiatry is, before having seriously studied or lived it.

Report comment

This is a beautiful essay. I appreciate your honesty and humility. Ordering your book now.

Thank you.

Report comment

Hi Sandy, I have an MFA in creative writing with a concentration in memoir, Goddard College, 2009. I am also a survivor. I have written about ten books and I hear what you are saying about not being able to change an old text. My thesis, which I published, is a piece of history. Published writing is personal history even if it is not memoir. The work represents where I was at that time, ten years ago. I used the term “mental illness” as part of the secondary title. I will not take that back. That is what I believed in then. Now, I know better.

When I wrote the book I had no clue, for instance, that the year and a half I spent “very ill” in 1997 or so was actually not an illness, but brain damage from ECT. It took me a long time to realize this, and now, I can go back and look on that chapter and realize just how misunderstood I was during that time.

I am caught in the middle a lot when I write. My friend, whose intentions are certainly good, tells me that if I call a mental hospital a prison people are going to be turned off. But what else could it have been? I am caught between trying to sell a book and feeling driven to tell the truth.

Report comment

The truth sets us free.

Report comment

Hi Sandy.

Here’s a quote for you.

“I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” Maya Angelou.

You were right to point out how people like people like Teresa Sheehan are treated whether “mental illness” exists or not.

Report comment

“Of course I now wish I’d worked harder to wrap my head around this question of what ‘schizoaffective disorder’ was or wasn’t, or how psychiatric medications fit into all this.”

A little about “how psychiatric medications fit into all this.” The “schizophrenia” treatments (which are today also being given to the “bipolar” and “depressed” labeled), the antipsychotics/ neuroleptics, can create both the negative and positive symptoms of “schizophrenia.”

The negative symptoms are created via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

And the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” like “psychosis” and hallucinations, can be created via antipsychotic or antidepressant induced anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But since these medically known psychiatric drug induced syndrome/toxidrome are not listing in the DSM billing code “bible.” Our “mental health” workers largely know nothing about these medically known psychiatric drug induced illnesses, that mimic the symptoms of the psychiatrist’s “invalid” and “unreliable” DSM disorders.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

I do agree, “The story we hear, the story the media repeats, is largely one that industry writes.” So that’s all the majority of people are aware of, and believe. I haven’t yet read your story, but it sounds interesting. Thanks for your blog, and respecting your uncle enough to research this topic.

The crimes being committed against our society by the psychiatric profession, historically and still today, do culminate in a shameful and tearjerking story, I agree.

Report comment

As a media critic, person with lived experience of mental illness [sic], and MIA staffer, I loved this piece. Thank you.

Report comment

I remember sitting in on a meeting in San Francisco, about 7 years ago, where CIT was being discussed because a gentleman who had been receiving services from California Behavioral Health Services (CBHS), and who used a wheelchair, was shot by police in front of the CBHS building because he was weilding a knife from his wheelchair.

Meeting attendees were the public defender, exec and assistant directors of Mental Health Association SF, an attorney for the defendant, several social workers, and me. I had been contracting with MHA-SF as public speaker and wanted to do more to help bring my lived experience to the table, for that perspective to have a voice in these matters. I was shut down and put on the defensive by those who continuously referred to the defendant as “wheelchair man.”

The public defender asked the attorney a couple of questions about the incident with the defendant, which he could not answer. The attorney passed around his card, and was more interested in media than anything, knew nothing about the client that had been assigned to him several weeks prior.

20 minutes into the meeting, someone came in and signaled to the public defender that he had a phone call, and so he got up and left without saying anything to those of us in the room, and never came back, whereas we all did not know what to expect. A vague discussion took place for about another 20 minutes, where everyone was confused, and then we all left. It was truly bizarre.

The dehumanization process and indifference that goes along with it are thoroughly systemic.

Report comment

I found this very moving. It seems to me that you have learned that humility is the beginning of understanding and being of help to another human being in distress. Sadly, humility is sorely lacking in most of our ‘mental health’ services and professionals. The entire enterprise is based on hubris and prejudice. I wish your attitude would spread among those who errantly believe they are helping. Being willing to hear that kind of feedback is painful but really the only path to gradually unraveling the truth.

Report comment

Thank you for the time and effort you invested in unraveling this critical life and death medical fraud and the compassion with which you did so.

Report comment

Beautifully written Sandy

Report comment

I really appreciate the process of journey you went through , Sandy.

There should be some sort of ethical framework for journalists in how to write on disability issues and a thorough and solid understanding taught in every journalism and or creative writing school on the whole world of disibties and civil rights, and ADA, and a deep understanding of the world history.

At one time, my local paper had a column about disability and I think she had her own story with the disability world which if one is truthful we all have.

The word skizophrenic is a firework word. There is so little understanding and so much FEAR.

There needs to be a dialogue and folks journalists, politicians, clergy, neighbors, relatives need to admit and own up to the fear.

Yeah as in Alex’s story the journalist should have admitted to being afraid to talk to him instead of acting out his fear and dropping the opportunity to do good journalism.

It would help to have disabled journalists of all ilks in every journalistic medium or for them to acknowledge it.

Also if writers or journalists use people’sstories and profit off them there needs to be a form of reimbursement to the individual folks and one also has to acknowledge having one’s story come out can have both positive and negative effects and what to do about the negative effects?

I would like to read about you and your uncle and the relationship. The uncomfortable parts and the comfortable parts.

And the dx part which has done such great damage that needs to be addressed.

And trauma and how we as as a world and society deal with all of its multifaceted layers.

How did and why did your uncle get labeled? And what was the real story ?

Report comment

Sandy, this is a very touching story and a great message to fellow writers and editors. You certainly have an open mind and a humble spirit. It is truly wonderful you got your Uncle Bob’s story told for him. I had a look on Amazon and one reviewer of your book sure stated it well:

“It challenges us to ask ourselves: Who’s really crazy—the people diagnosed with schizophrenia, or the society that allows them to be imprisoned, tortured, chemically lobotomized, and left to beg for pocket change on the streets? What separates a prophet from a madman, a doctor from a patient?”

Well done! I look forward to purchasing and reading your book.

Report comment