The standard conversation that typically ensues when an individual inquires, “Should I ever ask someone if they’re suicidal” centers around the myth that asking a person such a question might potentially be the cause of them reaching that state; as if the mere utterance of the word itself somehow makes someone more susceptible to a suicide infection of sorts. That’s nonsense. Most of us know that. But, there is a much deeper conversation to be had here. Specifically, even if we all fully accept that asking someone if they’re suicidal does not magically make them so, does that necessarily mean it’s a good idea?

The implication from the suicide preventionists who spend substantial time disabusing people of the aforementioned myth is that asking this question is basically the best idea ever. Gatekeepers unite! (Yuk.) And yet, I’m not so sure. It’s true that some people have said that being asked that question and answering it honestly was a “weight off their shoulders.” It gave them space to finally acknowledge their own personal elephant, and shrink it down to a more manageable size simply by speaking the words out loud. But that’s only a fraction of the story. It doesn’t change another, somewhat separate truth: The question itself has long since become corrupt.

For every person “Are you suicidal?” may assist, there are many more of us who are scared into silence when those words are uttered. Why? Well, “Are you suicidal?” is, in fact, the king of the suicide risk assessment questionnaire, with “Do you have a plan” serving as its beloved queen. Too many of us now know that those questions don’t typically come from the mouths of people who are invested in more than whether or not we need to be controlled and locked away. As such, “Are you suicidal?” has become the red, neon, flashing sign that screams “Stop! Don’t talk to me!” Perhaps this might just explain some of why suicide risk assessments are well known not to work.

It’s interesting that risk assessment is always seen as a one-way street: The professional evaluates the (so-called) “client” (or “consumer,” or “patient,” or “peer”… don’t get me started…) for “risk to self or others.” But, what of the risk posed to us by those seen as there to “help”? Given that force (including coercion), and being held on a psychiatric unit are both associated with increased risk of death by one’s own hand, the risk posed to us by providers (and those who see their roles as deferring to them) can be great. Saying “Yes, I am suicidal” to the wrong person can be the precise precursor to loss of job, relationships, identity, and freedom. Studies now abound that tell us that even being quarantined against one’s will in a cushy hotel or one’s own home can have long-lasting emotional impacts, and psychiatric facilities are usually a hell of a lot worse than all that. No wonder that question sends so many of us running in the opposite direction.

The truth is that the best way to create space for taboo topics like suicide to be discussed is not to hammer away at them, or try to force them open, but rather to build trust and create space for the conversation to move naturally where the person wants it to go. Such a process often allows for not only the answer to that question to be revealed but also for the much more important “why” to rise to the surface. This concept is, in fact, what underlies the Alternatives to Suicide approach.

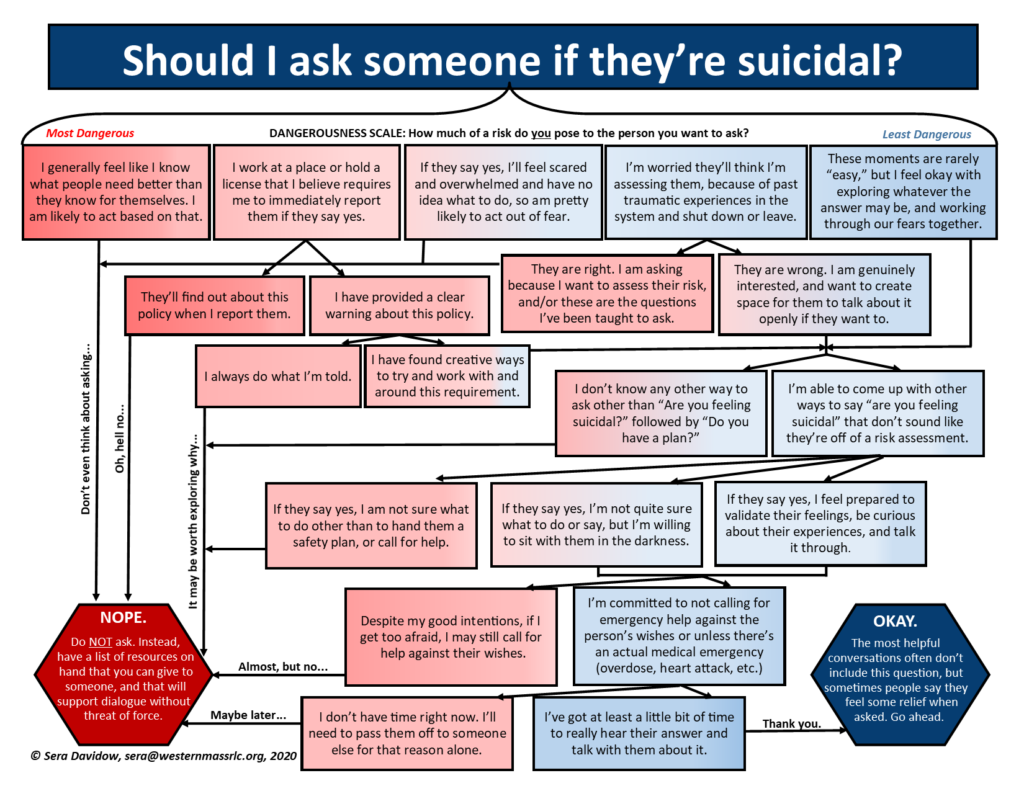

All that said, there’s that question—Are you suicidal?—still hanging around, and occasionally used as a tool for good effect. So, let’s consider how we determine if it’s ever worth asking within that aforementioned provider “risk assessment” framework. In order to do so, we need to consider (as any good risk assessment does) not only the risks, but also protective factors. The flowchart below attempts to do just that.

As you see, some of the major risk factors include:

-

- Routinely believing you know (due to your training, your work experience, or perhaps just your superior brain) what’s best for others. Unfortunately, this level of arrogance—not uncommonly rooted in the apparently unbearable worry that one has wasted their time and money on higher education and/or unintentionally harmed those they were charged with helping—leads people to crush personal autonomy and miss what’s right in front of them on the regular.

-

- Working in a role that (you at least believe) requires you to report the moment someone indicates they may be considering killing themself. This belief is often rooted in erroneous ideas about what it means to be a “mandated reporter,” liability concerns, and not wanting to be fired or face potential disciplinary action. It’s all often quite misguided, but all the more dangerous for how easily it is justified as “just doing my job.”

-

- Lack of access to other tools or time spent thinking of ways to speak about suicide beyond the most basic risk-assessment language. When someone hasn’t had a chance to unpack what they’ve been told, hasn’t been supported to understand the influences of systemic oppression and marginalization, and hasn’t been offered any other words or tools to explore… they tend to revert to what they (think they) already know. Effective or not.

And, while being overly confident that you know what’s best for others is high on the list above, conversely so is being wracked with a significant level of fear and uncertainty about what to do. Why? Because when we get afraid, it’s only natural that we fall back on the most concrete “what to dos” that let us feel like we’ve at least “done something” without leaving much space to evaluate how or why.

On the other hand, protective factors include:

-

- Adequate time to be present and not just pass someone down the line. Because you can be the most trustworthy, well-intended, anti-force-committed soul around, and it still makes it unlikely that the person to whom you make your “warm handoff” (gross!) will hold to the same standards.

-

- An already established commitment to avoiding coercive and force-laden acts, as well as a pre-established understanding of what constitutes a true “medical emergency.” Knowledge about the true impacts of force and coercion are not come by easily in this world. It takes work that cannot possibly be done when one is in the midst of what at least feels like a crisis. And, where medical emergency is concerned, should we care to assess the hospitals as to their efficacy in treating different conditions, we will consistently find that they do well in responding to overdoses and heart attacks. Quite well, in fact. But not so much for emotional distress of any kind.

-

- Prior work done and resources available to help the supporter to sit with their own fear rather than projecting it onto someone else. We are all caught in a society that tells us that the lines that separate the helped from the helpers is quite clear. That is a lie. And even when one is sitting most squarely in the “helper” role, everything challenging that comes up won’t be coming from the person they’re attempting to support. It is absolutely essential that each person learn to do their own work and find support resources for the fear that it is normal to have rise up in situations such as these. Otherwise, they’re all the more likely to make sweeping gestures to try and control what the other person does simply as a counterbalance to their own discomfort.

This idea of a risk assessment for providers is one that bears much more looking into, and is a project I hope to get to soon. In the meantime, when considering the seemingly simple question of whether or not to ask someone “Are you suicidal?” I hope we can at least find a way to simultaneously drive out the fear of talking about death that’s wrapped up in what might stop our mouths from forming around those words… while also finding better ways to be with and talk to one another all the same. It’s not that the question will cause suicide. It’s OK to ask some of the time. It’s just that we can do better than that. We have to.

Click here for a shareable PDF of the image above.

Glad your capable of at least discussing this taboo topic openly Sera.

I read the second question, “Do you have a plan?” and wonder what would happen if the plan was so bizarre that it seems almost impossible to achieve? For example;

Do you have a plan Boans?

Yes, i’m going to get a degree from University, get a job and save up enough money to go to Africa and travel to the Zambezie river where I intend putting myself in the path of a herd of Hippos (are they a herd?) and get stomped to death.

Not much of a plan but …… it’s a plan.

I suppose in the current environment I would be locked up for being delusional, getting a job waaahahahaha your insane.

Seriously though, good on ya for at least trying to speak openly about the topic. Thats at least heading in the right direction I feel. Though the way things are at present the questions can be weaponised to catch the unweary traveller who may find themselves wondering what it was they said to end up a dribbling mess in a locked ward.

“A traveller journeys along a fine road. It has been strewn with traps. He falls into one. Do we say it is the fault of the traveller, or the scoundrel who laid the traps?”

Good luck.

Report comment

Boans,

Ha, interesting question. Fortunately for you, were you to say that within the context of a risk assessment process, they’d probably rule you out for immediate use of force primarily because that’s a pretty long range plan, as opposed to an immediate risk. That said, I’ve seen providers who have an agenda to get someone in to a hospital use statements like “I have a plan” and simply write those down in their notes and leave out the broader details that make the risk seem minimal or at least not current.

And yes, the whole point of this piece really is that these questions aren’t a bad idea because suicide is scary and shouldn’t be talked about, but rather they’re a bad idea because they’re canned questions that usually signal “I’m going to try and take control now.”

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

“That said, I’ve seen providers who have an agenda to get someone in to a hospital use statements like “I have a plan” and simply write those down in their notes and leave out the broader details that make the risk seem minimal or at least not current.”

So you’ve met ‘verballers’ then? The line drawn by the law with regards sworn statements (not just notes) is that the statement should not be “false or wreckless as to the truth”. Deliberately remaining vague in your statements to mislead the reader IS an act of fraud, and should be dealt with as such. The ‘good faith’ defence does not apply. The intent was not good, but rather to decieve, ie bad, or should i suggest, evil.

“The validity of an oath, affirmation or statutory declaration is not affected by the fact that the person taking or making it does not use the exact words required as long as the words actually used do not materially affect the substance of the exact words and are not likely to mislead.” (From Oaths, Affidavits and Statutory Declarations Act 2005.

I always smile when I read the response of our Chief Psychiatrist to my complaint about the fact that my dentention was enabled by a ‘verbal’. He states that the Form 1 Stat. Dec. gives reasonable grounds for detention, which only proves that the ‘verbal’ is effective, and has actually misled him into a false belief that the detention was justified. Not likely to mislead? He has provided me with the proof that it misled.

The Community Nurse who had a duty to use literal and not figurative language writes in his “observations” (a protection from being locked up on heresay) that he saw me having “thoughts of harming others”. Note “others” when what he was informed of was a disagreement I had with someone three weeks earlier, which had been resolved.. So he literally travelled back in time to make this observation and make it current, and just changed the singular to plural to generalise the threat. Quality work from a fraud and slanderer. I wonder sbout how many deaths this particular person has caused, and those who are protecting him in his acts of fraud.

In my State unfortunately they encourage public officers in acts of ‘verballing’. I even went to a creative writing class with a police officer who was having difficulty doing it. Imagine him writing down the facts. The aim is to mislead the reader into thinking you had justifiction for your actions. Combine that with the planting of physical evidence and the world is your oyster. The ‘watchdog’ bodies have been ‘spiked’ and had their teeth removed by our politicians desperate to appear to be getting results with regards crime statistics (note I say statistics, they don’t give a damn about the organised criminals operating in our hospitals, and are in fact aiding and abetting them).

There was a Royal Commission into Police Corruption here many years ago now and the Commissioner stated that the corrupt practice of ‘verballing’ was having a damaging effect on our courts. Resulting in many wrongful convictions etc. I feel certain that this poison that runs rampant in mental health services has resulted in many deaths from suicide, though they tell me they don’t do body counts of the enemy. Must have been their illness huh? Maybe we need more money to try and stop this epidemic?

Report comment

Hi Sera,

I’m not a therapist, but I can see why this might be a tricky question.

The main problem I see is the Control and Authority thing in ‘Mental Health’, otherwise I’d imagine it would be perfectly okay to ask the question (if it was suitable) and to advise, or support a person as they would like.

(I recall seeing an article some time ago on a BBC Website where seemingly a lot of young British people privately dwell on suicide – but obviously most don’t go ahead with it).

Report comment

Fiachra,

Yep, that’s the issue… When I facilitate trainings on this topic I and my co-workers spend a fair amount of time zeroing in on the fact that loss of power and control is a major contributor to suicidal thoughts and feelings, and examining how the system that’s trying to stop someone from killing themselves nonetheless immediately resorts to things that take power and control away… It makes zero sense, and yet it happens all the time.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

Yup. Nothing says, “I care” like handcuffs, a squad car, and being forcibly injected with mind-altering and body-altering drugs. Cheers me up every time.

Report comment

To be completely honest, I cannot identify with non psychiatric ‘medication’ induced Suicide.

I know people often find life very hard, but most of the time they don’t kill themselves.

Report comment

Well, there have always been suicides, but it appears that using “medications” can make people kill themselves or want to who never had that impulse before, that’s for sure. How SSRIs ever got the reputation for being helpful for suicidal people is beyond my comprehension.

Report comment

The fact that “Antidepressants” can cause suicide is a bit like – a “sick joke”.

Report comment

“Yup. Nothing says, “I care” like handcuffs, a squad car, and being forcibly injected with mind-altering and body-altering drugs. Cheers me up every time.”

I used to think the one good thing psychiatry has given the world was the script for Frasier (Cheers …… me up every time). How ironic that in his workplace his signature line is “I’m listening” and he has headphones (earmuffs?) on lol

Report comment

I LOVED the graphic! I am envisioning a potential client approaching a “professional” with this in hand. “Before I agree to share my feelings and experiences with you, I have a few questions I’d like to ask. First off, do you feel you are in a better position to know what to do that some of your client? Please elaborate…”

Report comment

Haha. That’s my fav part of this, too, Steve. I’m wanting to develop a whole risk assessment for providers (to be used on them, not by them to be clear :p) soon!!

-Sera

Report comment

Sweet! I want a copy!

Report comment

Why ask them when you can simply presume they are? As just happened to someone I know….

Anyone here remember those old books for kids “Choose Your Own Adventure”?

Well psychiatry is like one of those only no matter what you answer to “Are you suicidal?” the outcome is the same…

Report comment

In fairness, there are some rational helpers scattered about in the “mental health” system, and if you’re needing someone to listen and they have the capacity and skills and proper attitude to do so, it would be a shame to blot them out by generalization. On the other hand, Muhammad Ali used the analogy that if you’ve got a hundred snakes outside you’re room and 90% of them are nice snakes and only 10% are planning to bite and kill you, are you going to go out and check and see which ones you can trust, or are you going to just keep your damned door shut?

Report comment

I know Steve. Just in a bad mood here….Someone I know was made to disappear into the system lately and they used a false accusation of a suicide attempt to get them there. From the details I eventually got it doesn’t even remotely sound like they were suicidal.

P.S. The snakes I’ve met were quite nice actually. Very shy creatures…far less afraid of them than psychiatrists lol.

Report comment

A sad comparison!

“Hospitalizing” someone for suicidal thoughts or plans is one of the most counterintuitive things I can think of. And someone PRETENDING you are suicidal is far worse!!!! I can’t imagine my rage – but of course, my rage would be “evidence of my disorder” and be held against me, too.

Report comment

Yes I’m very angry, or “mad” in the true sense of the word over what’s been going on here. Not that this is about psychiatry but I’m feeling this kind of anger (very fitting for these times):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRuS3dxKK9U

Report comment

I’m sorry that happened to that person (and so very many others). As I noted above, there are many times when answering the questions “right” can help someone stay out of the system… But, of course, one of the great foundational problems of why we’re even here on this site having these conversations is that – when the system has an agenda for you – they have the power to make it happen in far too many instances without their ethics or ‘rightness’ ever being questioned (at least in a way that requires them to respond).

Report comment

I’m not sure it was even a situation where there were questions asked to be honest. Too complicated to go into here, but they may never have asked just assumed.

Report comment

No Scientiologist ever called me “schizo”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vd9aIamXjQI

Report comment

Very powerful clip boans thank you for that.

Report comment

Yes ThereAreFourLights, it sure is.

What I like about it is it highlights how psychiatric supporters and mental health professionals will use the Sceintologist claim against we who oppose them (anti psychiatrists), and we end up fighting against the Scientologists for them. It’s clever, and has not gone unnoticed.

Notice the educated white boy trying to get Ali to go and kill yellow people for him, so that he doesn’t have to?

Accusations of being a Scientologist work in exactly the same manner.

Report comment

But boans South Park says Scientologists are bad. Who are you to disagree then? lol

Seriously I’m convinced most people’s hatred of Scientologists can be traced to South Park and that time Tom Cruise jumped on Oprah’s couch. When people would tell me they were opposed to Scientology I’d ask them what they knew of it and…they usually haven’t got much to say.

Someone’s doing their thinking for them…

And as far as psychiatry is concerned, my feeling is that if they want to call us all Scientologists, then psychiatrists have to be accountable for that. Scientologists don’t control what psychiatrists say.

Report comment

One of the short surahs in Qur’an about those who reject faith (al Kafirun) says “to you be your Way, and to me be mine”.

It says a lot without saying a lot lol. I’m not put here to shove anything down anyones throat and force them to think like me. And in return I expect the same.

This raises the question of what it actually is that psychiatrists ‘treat’. The behaviours? Well, then consider I was referred by police for a mental health assessment because I was asleep, and was in possesion of a knife (lets assume they didn’t know it was a plant). So it can’t be the thoughts, unless they could see my dreams. And it can’t have been the behaviour because I complied with their requests to get up against the wall and spread em. So what was I actually referred to mental health services for and had my life destroyed because of????

Hearsay. Rumours. Slander. Gossip. Backstabbing.

These are signs of people who need to be treated according to my Book. And not harshly with beatings and beheadings, but with understanding. They need to be raised up to become good people. They really lack insight into their conduct, and the consequences of it. And should they fail, then they may require some coercion. But drugging them to damage their brains? It might work. So might a public flogging. But what is it that makes them act in this manner? To think that behaving like night club rapists could be disguised as ‘medicine’? Well, to be honest, the rest of my community seems prepared to do just that, accept it as ‘medicine’, because these vile people seem to have deceived the community, in one way or another. Is it the fear of having them snatch you out of your bed next for complaining? Or is it that you truly believe what they are doing works (despite ample evidence to the contrary)?

I’m standing by the above though, no Scientologist ever called me “schizo”, and in fact they were one of the few who bothered to listen to and hear what I was saying. This of course before police realised I still had the documents. I can’t imagine that the truth went iunnoticed by people with a thorough understanding of the law. But, maybe they’re as ignorant as our Cheif Psychiatrist and don’t even know what a burden of proof is?

Ever lifted a piece of tin in a shed and watched as the mice ran in all directions because they felt they had been exposed? The cat got his lunch that day.

Report comment

“No Vietcong ever called me nigger” — Muhummad Ali

“No Scientologist ever called me schizo” — Boans

Report comment

ThereAreFourLights,

You’re right that some providers are willing to twist and look for signs of whatever they want if they’ve got a particular agenda… On the other hand, I’ve seen people who’ve been dragged through the system quite successfully give each other advice on things like how to answer the questions so as to not end up in a psych facility, etc. It’s one of the more valuable forms of “peer support” that I’ve seen take place. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

“Are you suicidal” seems like an almost zen-like question. It’s a very subjective definition/self-definition. If someone were “suicidal” in the sense of being gay, or Catholic, truly “suicidal” people would be almost impossible to find alive (other than those who were highly incompetent). Otherwise it’s like asking if someone is “violent”: it has more to do with a specific circumstance. (Also, asking “are you suicidal” is a little different that asking “are you currently contemplating suicide?”)

Finally, from what I know of quantum theory (which is minimal) the nature of any reality is changed by the presence of an observer, hence seeking any objective answer to such a question is impossible; the person doing the “assessment” is actually a participant in the phenomenon being “assessed.”

For what it’s worth, Camus said that the only legitimate philosophical question is whether or not to commit suicide, that the rest is just detail, or something like that.

Report comment

Contemplating one’s own life or death (such as Camps spoke of) is indeed an important question that far more people consider than those who will admit to it. It is a far cry from that contemplation coming from another person, often in the spirit of assessing how much control they should wrest from you. :p

Sera

Report comment

oldhead you are breaking principle one of dealing with psychiatrists–never talk to them about religion, politics or philosophy. Or physics. Or the news. Or literature, art, alchemy, tarot card reading, ornithology, mycology, anthropology, film, opera, basket weaving, hairdressing, tax preparation, Egyptology, astrology, big band music, mechanics, science fiction and fantasy, reggae, mythology, divination, ritual, football, hockey, baseball, stamp collecting, skateboarding, gaming, calligraphy, history, computer programming, horticulture, feminist theory, ufology, flint knapping, crocheting, photography, animation, tea leaf reading, knitting, quilting, guitar playing, shamanism, classical music, tennis, scuba diving, wake boarding, kite flying, historical re-enactment, herbal medicine, reiki, bottle cap collecting, phrenology, poker, sewing, gardening, calculus, art restoration, equestrian, cross country skiing, archery, travel…. It’s an automatic admission.

Report comment

I loved this comment. 🙂 hahaha. Still chuckling.

Plus thank you Sera for the essay. Very helpful.

Report comment

ThereAreFourLights comment is indeed a good one!! :p Thanks to them, and to you, o.o. for spending some time here. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Sera, thank you for your article and work overall, I really like your writing. And it’s nice that you engage with the readers too.

Report comment

I love it ThereAreFourLights.

Trouble is that this ‘right to silence’ in regards mental health professionals opens one up to the use of known torture methods here in Australia. They couch it in terms of “medication administered without knowledge” and induce an “acute stress reaction” rather than simply write, ‘won’t talk, torture required’. I feel a bit like someone who has been shown how to do the trick with the three cards, and I stand watching as people are being cheated out of their money by scammers. Only it isn’t their money they are loosing but their human and civil rights. Right under the shadow of their big noses (as the Finns say).

And of course once mental health services are allowed to do it, police will be most enthusiastic about accessing their services, and tbh I can’t blame them. No one here wants to talk to them either given their reputation (that they don’t know about).

All they need is one doctor prepared to sign off on ‘spikings’ (i’ve got a name, and a possible reason as to why this particular doctor might wish to commit such corrupt acts for police. A Quid Pro Quo, and I know he speaks Latin as I tested that when I spoke to him without the staff understanding what I said. Vulpes Pilum Mutat Non Mores. Forcing me to remove my clothes and inserting objects into my mouth or anus when I had denied consent? You’ve done this somewhere before Father.). That ‘assault’ then combined with psychological coercion resulting in the ability to conceal acts of torture, simples. But lets keep it between you and me huh? We’ve got people at the lowest levels of police and mental health services authorising the use of known torture methods, and their superiors then concealing these vile acts for them. Amazing the knee jerk reaction to ‘refoul’ victims of torture here, and leaves me wondering how much of it they are actually doing when they have a system set up to conceal it.

Report comment

boans I just read that you felt you have had a stroke. Very concerned for you…I understand why you wouldn’t want to see a doctor (I am the same way.)

I know (ethical) doctors would be best for you to see for a stroke but, given the risk here…are there alternative people who work outside the tax funded system where you are who might be able to help? Our health care systems (which are different based on what province you are in) cover most health care services but there are some kinds of practitioners like acupuncturists who are not covered…and records don’t get sent to them.

I realize this is probably not helpful information as i would guess were it an option you would have already thought of it by now. Just feel sick at heart reading of your suffering so, I feel so helpless reading that, if there is anything I can do please ask.

Report comment

Not saying that I know for sure that alternative health care pros can help a stroke, I don’t know if they can and I sure would not want you to get worse too.

What kind of a world is this where they torture you and then leave you with no help? It’s just unbearable, is there no justice anywhere???

Report comment

Oh there will be justice, but not in this place.

I have tried to remove myself from here but have been denied access to my property to do that. It’s clever, anyone who speaks the truth, don’t let them eave, particularly when they have the proof.

I really don’t think I give a damn anymore. I tried in the flase belief that people actually cared when others were being tortured. I mean I see people who have actually committed serious offences get access to legal representation and complaints regarding torture. I disagreed with my wife, who sought advice from someone who wished to do me harm. And who had already done so.

Anyhow, good news is they have passed a Euthanasia Law here and can ‘treat’ anyone they wish and as I have proven they can then distribute fraudulent documents to any lawyers wishing to make inquiroes about the unintended negative outcome. That is total control. I have shown how to have police snatch people from their beds and have them delivered to any hospital one wishes for this ‘treatment’.

I have asked questions regarding these crimes only to be ignored by people with a duty to act on them, in fact in the case of the Chief Psychiatrist he has rewritten the law to ensure he removes the legal protections he is responsible for.

Not a concern on the opart of anyone. I even wrote to the Mental Health law centre pointing out these facts, but they too don’t recognise the legal protection of “suspect on reasonable grounds” and seem to think that what was done to me was perfectly reasonable. I ask anyone who knows what O have claimed how they feel about that. And how they then feel about the protections THEY have as a result of agreeing with these authorities.

I’m sure it was all a big mistake, and we can’t have torturers and kidnappers being punished. It would maen a loss of trust on the part of the public, and that is needed when your kidnappig and torturing and calling it medicine by a change of status post hoc.

Come on guys, were all making lots of money. Whats with complaints about shoving a few into the showers. It’s not like its large scale, yet.

I really do not care anymore. Who would want to live in a place where all is false. People talking about their ‘battles’ against the abuse, actually participating in concealing the abuse? Well done to the Mental Health Law Centre in the assistance you are providing the government in concealing these human rights abuses. I mean where else would people turn in a time when they were bieing subjected to abuse by mental health services? Your worth the money from the government to assist in concealing any demonstrable abuses. And what a shame the people who volunteer at your service go into it with the opposite intent, ie stopping human rights abuses. More than their careers are worth in the end I guess. I’m sure they will do weel as a result of being taught how to do the ‘nasty’ to victims of crimes, not unlike the people who concealed children being raped by priests. Though that should worry you because you can’t run and hide forever.

My faith is strong ThereAreFourLights. If I am meant to go, then so be it. If not a real doctor who treates people, and is not interested in the political gains to be had from the organised crimes being enabled in our hopitals will step forward. Amd keep in mind what happened the last time a doctor tried to murder me lol. Had him doing all sorts of extra work running the doctors union, corrupting others, free hair cuts in the lunch room ……. lol

Looking back I get the feeling that the biblical prophesies were fulfilled. My wife two broken arms, the Minister and principle of the Law Centre ‘flogged’ and not allowed to act in the name of Jesus, the Community Nurse running for his life calling on a God he didnt believe in when he was bearing false witness…… Allahu Akbar.

My work here is done 🙂 I’ll leave those who continue to maintain the falsehoods to others. It is known who they are and they will be dealt with in His time.

I like where you got your name. I see four too, funny that.

Report comment

never talk to them about religion, politics or philosophy

This is key…Psychiatry Inc. has no “official” position on “life after death” — something it conveniently ignores as perhaps irrelevant or “personal” (as though anything else they want you to talk about isn’t personal).

However, one’s beliefs about whether or not life/consciousness continues following the death of the physical body has a great deal to do with how he/she presumes to live a good or “appropriate” life on Earth. So how can they legitimately “kick the can down the road” on this while professing expertise on everything leading up to it??

Report comment

Thanks O.O…I saw your post about your t-shirt about surviving a ward too I almost spit my drink on my laptop reading it lol sounds like you are a fair prankster…My kind of person (wish I’d thought of that shirt idea!)

But what am I saying…No laughing O.O. and no talking about laughing either… 🙂

Report comment

I would take what most contemporary scientists purport to know about quantum theory with a pinch of salt. Look up what Eric Dollard (today), and others before him, like Tesla, Steinmetz and Heaviside have / had to say on the nature of the universe.

Report comment

If I observe a priest, or a sports teacher, or a swimming instructor (sexually) abusing a child, I’m not going to blame myself (partially) for observing the act just because I was a witness (or observer) to it. I would, however, be complicit, if I didn’t try to stop it. If I stop it, it doesn’t change the nature (or intent) of the act that was in progress.

I am responding to this:

“the nature of any reality is changed by the presence of an observer, hence seeking any objective answer to such a question is impossible”.

Report comment

A quote (I don’t know if he actually said this), Tesla made about Einstein:

“Einstein’s relativity work is a magnificent mathematical garb which fascinates, dazzles and makes people blind to the underlying errors. The theory is like a beggar clothed in purple whom ignorant people take for a king… its exponents are brilliant men but they are metaphysicists rather than scientists.”

Report comment

Except that all sorts of successful technologies are based on his theories.

Einstein was not in the “quantum” camp apparently. But don’t ask me to specify the key conflicts here.

Report comment

“Except that all sorts of successful technologies are based on his theories.” (Oldhead is referring to Einstein).

No, all his theories were stolen. His “groundbreaking” work on relativity is stolen. He doesn’t reference anyone for his “findings”.

His most successful technology is this:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einstein_refrigerator

Most (if not all) of the work was done by someone else.

Report comment

I’m not going to blame myself (partially) for observing the act just because I was a witness (or observer) to it.

I’m talking about physics, not morality.

Report comment

“the nature of any reality is changed by the presence of an observer”

I was referring to that. But I get your meaning, by “any reality”, you are excluding human behavior (or even plants). It’s a bit bizarre, but ok.

Here is a famous quantum theorist squirming when asked about magentism:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MO0r930Sn_8

I learned a lot about slippery surfaces, but not much more. Notice the interviewer asked first “why” magnetism happens, and then “how” it happens. The quantum theorist concentrates on the “why” and goes into a long monologue about aunt Minny. It suggests he doesn’t have a good answer to the “how”. And there is a reason for that. Most (if not all) of the technology we have today is attributed to people who were marginalized, like Tesla and Heaviside.

Report comment

I think in the IFS concept of the mind, some or most, maybe all of us have among our many parts of the mind a suicide part, which looks at how much pain we are getting and makes suicidal feelings to help us escape from what it considers unbearable. So if I was talking to someone I think I would start with that idea and then ask them about the pain, because then it’s not like a one subject discussion. We could talk about maybe asking the suicide part why it thinks this pain could be unbearable. Then you don’t have this kind of all or nothing thing you have with a unitary mind.

Report comment

dfk,

That’s a really interesting idea, dfk, and absolutely..this all or nothing way of thinking about people and their distress is really bizarre and harmful. As is the idea that most “normal” people don’t ever think about suicide. The reality is that most of us do, but even the “suicide prevention trainings” like “ASIST” make that seem shameful.

-Sera

Report comment

Yes, risk assessments for professionals! I love it

Life takes courage and sitting with someone in the most difficult spaces takes more than most ‘professional services’ support, allow or encourage.

I fear professional responses and ‘care‘ more than almost all human experiences of emotional and existential distress.

The best “alternative” I’ve found when one may want a bit of what professionals offer is Peer Supported Open Dialogue, (POD) with at least equal numbers of peer and clinical 50:50 staff facilitators.

Thank you Sera

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Truth in Psychiatry. Open Dialogue is so interesting. I share about it often in trainings for a number of reasons, but – while I’m aware it’s happening – I’m not terribly familiar with the “Peer Supported” version, and I’ve heard real debates about how ethical it is to have peer supporters be involved. I’m not sure what to make of all that, but you’re absolutely right that the average “professional” is in a bind even if they want to do a good job of supporting someone through a really dark time based on what’s expected of them by their employer/the system overall.

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks for your response Sera. I am familiar with the differences of opinion about including peers in anything ‘clinical,’ including Peer Supported Open Dialogue. That word itself is a huge problem and assumes a medical, individual pathology understanding before there is any conversation about what’s happening. The invitation for polyphony and disagreement is one of the things I value most about POD and the dialogic approach.

I share many of the concerns I’ve heard about ‘peers’ on treatment teams, especially with the ongoing power imbalances that keep people with lived experience in token or junior clinician type roles. Systemic power is a real and pervasive concern and has led me to push for an approach where peers are at least equal in power and number to any other role on the team.

As someone with survivor, therapist and parent experiences with emotional struggles, I have noticed that we often still turn to or end up in the current medical model system when things get really tough or when we don’t know of or can’t find the much better alternatives out there like Alternatives to Suicide, peer run respites and HVN. POD is the best thing I’ve found so far, but always welcome the dialogue about better ideas.

With respect always

Report comment

I had an interesting experience with a (mental) health worker (over a period of some months). I began slowly confiding (of sorts) in him. Even bought him lunch a few times. I won’t get into the details, but it was the wrong thing to do. I did give the whole organization he was working for a piece of my mind.

Confiding in a psychiatrist (the top of the pyramid) is almost always guaranteed to be disastrous.

Report comment

I know I can cope without neuroleptics, with the help of ‘basic psychology’ – so I’d wonder how many MH Workers are up to the job.

Report comment

Never try to explain anything to a “helper”. One really never knows what the helper is quietly thinking.

Too often, a conversation is one way. True dialogue is when two parties are completely safe to be open with each other.

Perhaps it is rare.

One can fall into a hunger for am open discussion.

Report comment

Berzerk,

I’m not sure what happened, but I can imagine several possible outcomes to that that could be really harmful. I’m sorry that they violated your trust however they did. Someone mentioned Open Dialogue above, and from what I at least understand of how it exists in Finland, one of the key differences is that many people actually *trust* their system and reach out for help early on in their distress. Can you imagine living somewhere where the system designed to “help” actually helps more frequently than it hurts, and can be trusted in that regard? I wish I could.

-Sera

Report comment

Sera,

Awesome as usual. You put so much work and heart/thought into your blogs.

You do create a safe space.

I guess we have to ask if the act is wrong and how so? Is it “morally” wrong?

We also have to ask if the thoughts are wrong.

Psychiatry should explain fully of why it is illegal and it must be illegal if people are not

allowed to talk about it, and risk jail for it. Psych units are absolutely not “hospitals”.

One could use any cage, it’s all the same.

Of course we know the underlying reasons are about self protection, in a legal manner. Thing is, the chemicals cause suicide and there is no legal protection for the client. But it looks good on paper.

So many “health professionals” are coached in “suicide prevention”. They are 22 year old nurses who are interested in hitting the bars after work, who might or might not have ever encountered a thought beyond needles and makeup.

The suicide prevention classes are unfair to everyone. It is absolutely not based on any reality and as such can never be dealt with in any real constructive manner.

If all they do is “teach” people that it is wrong and a “MI”.which of course the teachers know is bogus)

It’s interesting that on some reserves in Canada there has been explosions of suicides in very young.

They send counselors. “let’s “talk” about it”.

Suicide is most often a sign that it is MUCH bigger than the thought emanating from the person and as long as the focus is on the person, it will create chaos, with often disastrous results and the reasons are never fixed for the next person.

I love the new age question that some people use now “Are you safe”?

I heard that posed to me last year, and I innocently thought that the massage person was referring to me being safe from someone other than myself.

After we got to the bottom of it, I really gave her a talking to. About the conspiracy narrative running around in her head, about possible projection and that I had not made presumptions about her, but boy did she open a can of worms and that she should realize that SHE is the one who left me feeling not just unsafe, but rather grossed out and I was not about to come back and lay on a massage table, to be made to feel really weird.

I’m afraid she had no clue what I was talking about, but I do hope she doesn’t go around asking people if they are “safe” anymore.

If she had asked me if I was safe from other sources, that might have been much more relevant.

So yes, that question can have bad effects and often it’s completely off the beaten path.

One also has to wonder, when is it really someone elses business? In order to truly “save” people, one has to inquire about just about any other environment around that person. It is mostly their environment that is not “safe”.

Report comment

Sam,

Hah, A co-worker (Sean) and I were just talking about what ‘safety’ means within the context of a film we’re working on (related to psychiatric oppression). It is indeed one of the trickiest questions they’ve got, especially as it relates to being a “risk to self or others.” So many words and all their special meanings in the system.. Oy.

-Sera

Report comment

Awesome about that film. I’m so glad you have the energy and I hope you continue to have that energy and passion.

Report comment

I’m going to go on a little rant here because it’s safe to do so.

The suicide question got me sent from the ER to a separate psych ward. Of course, I had gone to the ER because I had a really nasty skin infection, but I guess my non-existent suicide threat was more important than antibiotics. (It was a bad infection. The ER nurses were almost impressed with how bad it was.)

All because I answered the question, “Have you ever thought about suicide?” with a “Yes, but I don’t feel that way now.”

I was only held for 18 hours, but I managed to check off enough boxes in psych ward bingo.

I was separated from my dad because I was a “danger” and placed into a different section of the ER. I had my shoes taken away (never got them back, either) and was put into a tiny room with three beds crammed into it. The only thing I could do was lay and watch TV. No food or water, even though I was there for a solid 8 hours.

Then they took me to the psych ward at 3 AM. Since I was “crazy,” I was strapped down to a stretcher. I had straps over my head, shoulders, waist, hips, legs, and ankles. The people transporting me were nice, though.

Then we went to the psych ward, where I filled out paperwork, got my photo taken, and was stripped searched, and then shown a bed. I actually slept for a few hours and then got dressed and made myself presentable. I’m still not entirely sure what the search was for. I don’t know if they were looking for scars, contraband, or drugs. Maybe a mix of the three.

I talked with the psychiatrist, who was polite enough, but then diagnosed me with bipolar disorder because I was very chipper and that didn’t fit in with the intake report. In reality, I was trying to talk my way back to the ER.

They tried to give me meds, but I knew I had the right to refuse their treatment because I had gone in “voluntarily.” Based on a five minute conversation, the psychiatrist wanted to start me on a high dose of Topamax. Thankfully, I knew enough about medications to be like, “Whoa, wait. Let me see the drug info.”

They also tried to give me a nicotine patch, even though I’ve never smoked. Apparently they just give them to everyone there.

What they didn’t do was give me any of my regular medication. I’d missed multiple doses with some of them and they didn’t really seem eager to get them to me.

Let me take a moment to mention that the air conditioner in the facility was broken. This was in June in Florida. It was sweltering.

The ward wasn’t separated by gender and the nurses stayed in their little area. So I had a creepy guy dressed in only a robe come into my room several times, to the point where I mentioned it to the nurses. He did offer me some meth, though. Now that I think about it, the robe was closed (thankfully), but I’m not entirely sure how it was fastened.

Robe guy also announced that his plans for the day were to create a scene so that he’d have to be injected with sedatives. Apparently this was a daily thing and he just came to the facility to get drugs.

There were also a few people who were homeless and were mainly using the acute care facility as a way to get meals and a safe place to sleep at night.

Eventually, my father was able to convince the facility that I was actually quite physically ill and needed medical attention. So I ended back up at the ER and was in the hospital for a week or so, getting 3-4 doses of IV antibiotics a day.

When I’d asked what I had been sent to the psych ward for, they said that I had been taken in because I had been physically violent and threatened to kill my cat with a knife.

I didn’t even OWN a cat!

Moral of the story: Don’t be lazy and attempt to shave you legs with a dry razor. It will make little micro-cuts in the skin and then get infected.

Report comment

30-Watt lightbulb,

Thanks so much for sharing your story. I feel like it would make a powerful published story about the absolute absurdism of the psych system, if you ever decide to write it!

Sera

Report comment

You ended up needing a week in hospital on antibiotics, which is very serious.

There is nothing “medical” going on in a psych ward, despite a few workers believing so.

Most of them don’t believe it.

Psychiatry eventually tries to “defend” itself by saying that clients came to them, so whatever they get was asked for.

LOL, they actually say this. Of course when they get completely flustered.

Report comment

30-Watt lightbulb this story isn’t even unusual, in fact when closely looked at, there are elements of psychiatric authorities or concerned citizens displaying this kind of corruption and paranoia in most if not all cases involving incarceration, diagnosis etc. All because they think there’s some danger, and are so sure of it that they feel free to lie, distort and manipulate through strategical untruths what’s going on. All the way from the basis of whether they are dealing with a chemical imbalance to a person’s behavior to begin with.

I had a friend, who since had committed suicide 12 years ago, who was committed to an asylum, with such lies that when I passed by the whole chase scene, and the police were at her house, and if I simply greeted her (she was outside on her steps) while her “friends” were “informing” the police about stuff, that a police officer told me if I didn’t move on I would be arrested. When I asked why, he said I would be arrested for disrupting an investigation. So, I went home and called non emergency dispatch to tell them that her “friends” had trespassed into her house to call her case manager, after scaring her so badly that she had run away from them and her house. Of all things non emergency dispatch told me that she had been taking her clothes off in public. I had been with her when her friends scared her, and after she took off, at first trying to get away on my bike which was locked and clamping down on the pedals that wouldn’t move being locked with such fright that she ripped her Achilles tendon, and then she had run off; the first thing that one of her “friends” said to me was: “she’s running around naked.” Afterwards, I found out that what dispatch told me, and what her friend determined she was doing, that that wasn’t going on at all, and hadn’t been. She hadn’t been taking her clothes off, and neither had she been running around naked. But And if I simply was around without such paranoia I was interfering with an “investigation.”

OK!

Well, and then her Achilles tendon having been ripped, and needing attention, which expressed itself by there being swelling up to her knee while she was in the asylum, and that not being looked at although she was in a wheel chair consequently (apart from for fun that she in the asylum allowed visitors to scoot around in wheel chairs that were just sitting there not being used, and then the next time we visited the workers being panicked that anyone might be using them and had been told to be wary), no one cared to really find out what kind of a physical wound she had which was why she was in a wheel chair, and by the time she got out her Achilles tendon was ruined for life, and she couldn’t walk around without that disability.

And there are really vulnerable people that already have been made terrified of behaviors they don’t understand themselves, behavior that in contrast to the paranoia against them are completely non violent, and yet they end up thinking that such paranoia is logical, or they just give up even trying to refute any of the lies, as little as one can get people to question the ideology of a fascist system.

I’m glad you somehow got out of it. Being in an asylum because you wanted to kill a cat you don’t own, and then not getting the treatment you needed because of an infection, that’s something they might cover up as well, if you hadn’t survived.

I’ve had people trying to say that my thoughts were non reality based, while they made up more stuff about me that was completely not reality based, nor would they question it, the same as any officiated paranoia. There was one yoga teacher with parks and recreation who was also a social worker, and I actually heard a voice tell me to just stay away from her, and not ask questions, although I was really just interested in yoga. I had noticed how alarmist she might respond if I simply asked any question like anyone might, so I just ignored it, which I shouldn’t have. She thought I was in love with her (I’m gay, she couldn’t do anything for me, plus I found her repulsive and coy, and was quite a bit amused at how pretentious she was, and how she was trying to create following with such artifice). I couldn’t really make out what was going on, and was for a couple of days having thoughts that might be called “psychotic,” although I already saw after two days they weren’t what I thought, and since I completely understand the symbolism. But because I was “psychotic,” she could make me out to be someone that might get violent, and she got a restraining order, and when I simply wanted to correct the whole list of whatever it was (lies, paranoia, incorrect assumption) that amount to non reality based paranoias, she actually, after propping herself up in her chair and taking on the kind of sing song voice people take on trying to convince you they have the answer, said to the judge:

“I know, I know, he doesn’t hear voices, he sees things that aren’t there, it’s non reality based.”

After I had heard a voice telling me to just completely stay away from her. And to tell you the truth, I didn’t really have it through that people like that existed, and how completely totally indoctrinated and brainwashed they can be.

If I went out the same door everyone else did, which I ended up usually doing all myself because everyone else had left. I had to put the clothes over my jogging outfit back on, and her yoga didn’t really calm me down and had to rest a bit, so I most of the time was the last person out the door when she and everyone else had left. But if I ever went out the same door anywhere near the time she did, even though I didn’t nothing but go straight to my bike and leave, then I was following her to her car. And mind you, she would always in a coy voice wish me a good night. I didn’t know she had friends walking her to her car because she thought I was in love with her, which I wasn’t.

And there’s a whole list of other presumptions. And lies.

I had mentioned that her ghetto blaster that she played music on from a CD had one speaker that was giving out static, and she pulled a face as if to denigrate parks and recreation saying it was just for them, and she didn’t want to buy a new one. That turned into me supposedly saying I didn’t like her music (I had never said anything about whatever music she played). She had also mentioned while talking to someone else while I was slowly getting my stuff together to leave, that she had bought a bunch of chocolate, and I had recently found out that putting coco powder in your oatmeal gives you the same resonant buzz as chocolate without the sugar, and when I tried to mention this to her having overheard something she said, she tried to make out I was mad at her for eating too much sugar, and also said she didn’t know I paid such attention to what she said (apparently she was supposed to watch out with sugar) and then tried to make out that because I listened “intently” to what she was saying that I was in love with her. In all honestly I was quite a bit amused, like when you’re reading a story and there’s a really bizarre pretentious character that lives their life quite different that yours, and you would read the description. It WASN’T because I was in love with her at all.

And then she started groaning right in front of me (I had to sit in the front of the class because I didn’t wear my glasses to do yoga, so otherwise couldn’t see) about how she had just had to have vaccine shots because of her job in a hospital. I asked her if she was a nurse, she told me she was a social worker, and then I simply asked whether vaccines really helped as much as they say they do. And mind you, unbeknownst to me, she was getting herself all riled up about stuff that wasn’t going on at all, which I don’t think is good for anyone’s immune system. And she had started the conversation talking to someone on my other side, right through me, and then said I rudely started taking part in a conversation, as if again I’m not supposed to have ears, or even being aware of what she’s going on about means I have dangerous desires to intrude into her life. I couldn’t simply say you have to look at the other side of the argument in a resonant calm tone, or she got all spiked and prickled and annoyed like the spring on a mouse trap had sprung and said: “those who aren’t taking vaccines are making the rest of us sick,” after she said she wasn’t going to have a whole conversation about it. And then I supposedly said that all vaccines were bad, which I hadn’t said, I had mentioned some evidence against vaccines that I had been e-mailed to a parks and recreation person, because I wasn’t taking yoga classes to be told I have to be a consumer of drug company methods, and this is when I mentioned the ghetto blaster where upon they bought her a new one, themselves, because I brought it up, and they said maybe she was scared to ask for on. And I still don’t have any determined stand point one way or the other concerning vaccines, but I look at the other side of it.

And mind you, if I paid attention one way I had devious desires for her, but then she also mentioned that I didn’t do anything she said, during class, which wasn’t true. During one class I had a back ache and couldn’t to maybe 20 percent of the poses, so I didn’t do them, instead watched her to see how they were done, this turned into me supposedly having my head resting on the wrist articulated on my upper arm, and watching her 80 percent of the class.

I also got during that time bad eczema, and couldn’t ride my bike to class because the whether was getting colder and I’d have to wear gloves and my hands would sweat which was like torture to the skin because of the eczema, but might take the bus, which I couldn’t because the bike rack was full (I did ride my bike the half mile or so to the bus stop), when I didn’t show up for class SHE ACTUALLY said that I was resentful that there was a disagreement about vaccines, so I didn’t come to class. So, I actually couldn’t not be in class, and couldn’t be in class, and her assumptions could be magical telepathic insights rather than reality based, because she had to again make out that there was something going on which wasn’t going on, all to sooth her brain washing. I don’t know HOW I didn’t go to class because I had resentments, when having tried to get to class I couldn’t get there. Did I have some supernatural control over whether the bike rack was full, and did those bikes materialize out of nowhere, or the whole bus or what? I meant that’s pretty amazing powers on my part. If I WAS resentful, and that’s not why I showed up, I would have had to be able to manifest all of that to express such resentments.

And that’s just some of it. I could go on and on and on.

And her whole report read like stuff highschool girls would make up about someone they thought was weird, and this from a social worker. She actually said that I was “creeping” them out. I was just calmly getting ready to leave, and consequently doing that with no interest in her whatsoever but a yoga teacher.

In fact the stuff that they called psychotic was exactly expressing that. I have a spirit friend who was Mozart’s mother, and who had a really bad childhood, given HER mother. And then Mozart’s mother’s father had lost everything at one point. I somehow, started picking up that stuff like that was going on given investments, and when you invest in the wrong stuff you can lose everything (reality even);while at this time I didn’t know all of the above mentioned extreme paranoia was going on (was being invested in), something so extreme I was disassociating from it, unfortunately. And the whole Hollywood like chase scene that was going on all fired by adrenaline as if there was some imminent danger that really wasn’t there at all. And this or that resonance from another time made me think something symbolic was going on involving Hollywood, and I could go into it more in detail, but it doesn’t matter because it’s subjunctive and could be any of who knows what kind of stuff dreams are made out of, something more objective than anything tangible in the physical because it involves reflexes and determines the future.

Anyhow, I went on about this here, also

https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/08/blaming-mentally-ill-is-hate-speech/#comment-159669

What did I make up?

Back then, what I referred to there was stuff going on like there is now, only it wasn’t the drug companies, it was the Catholic Church taking over the economic system, invading and controlling government, people’s lives. There were harmonics of that going on, and I couldn’t differentiate, if there was any necessary difference to see, you see.

And there was even a sense of they know psychically what’s going on, and try to scare you, which is what I thought was going on, that the whole media machinery (Hollywood) was doing that, and I could go into stuff Hollywood is lying about or the image games they play, and actual actors coming into my life because I had talked about memories of being the dancer whose name this ID on this site carries, and it’s a big topic for actors, quite a few having played “mentally ill” people while someone actually have gone through it wouldn’t be hired by Hollywood, which already brings out exploitation.

There was a violin maker, during that time when the Catholic Church was taking over, named Guarneri Del Gesu. And he would go to a Tavern where he heard stories about the stuff going on. And there was during this time a Goodwill store that I went to where spirit seemed to be telling me that a lady working there had also been the one at the Tavern back then, the one handing out drinks and such, possibly the owner. And she ALSO had started acting paranoid, anyhow, it gets complicated because the extremely grim lady who worked at a Goodwill store… and I had seen her son at one point there, and it looked like he was working on the candy machine outside of the yoga studio; and then the male bathroom was locked. I had to use the other bathroom, and that had become symbolic enough.

And so I thought that the Goodwill lady, and the lady in the Tavern, that her son who I had seen was somehow connected with Hollywood trying to intimidate me that they had connections, and somehow could get into the workings in my life (could get one of their agents into the candy machine outside of the yoga studio), and I was supposed to be intimidated. Someone from Parks and Recreation actually suggested to call the administration of the school that the class was in (it was at night time when no one was in that school), but I actually know that when there’s such stuff going on that marketing agents would try to get as much going on (prattle blither and chatter) in talk about it, just to turn the whole thing around using the gossip for a marketing scheme for whatever, and suppressing the incomfortable truth. More chase scenes, more chatter about some evil, more magnifying social phobias that people are left allowed to go on about rather than about being human, so I tried to explain that to the man from Parks and Recreation who wasn’t intelligent enough to know what I was talking about, and then later mentioned that he didn’t know what I was talking about at all, which he said to others evaluating me rather than being honest enough towards me that I might have explained it to begin with. I would have been happy to hear there wasn’t such a spooky thing going on as a brainwashing organization trying to intimidate me that they could get an agent to being doing stuff to the candy machine outside the yoga studio, while the male bathroom was locked (which was supposed to have a symbolic meaning to it); which I figured out two days later (without calling others who would have thought I was crazy), but then it was too late. And it brought on enough paranoia to get me away from all of it, actually. And you would think both sides would know better, people from Goodwill, or a yoga teacher, especially a yoga teacher.

I was trying to make a point about investing in such stuff because I was wondering whether that yoga teacher had been the father of my spirit friend (who made bad investments and lost everything), only to realize she was more like the mother, and in trying to communicate any of that it was quite misinterpreted as well. Even like investing in the drug companies (psychiatric drugs) to make a bunch of money, if you would, you’ve lost the truth, and that’s not going to change for it either. Beyond that inciting fear in such a way that intimidation is more important than the truth, and if you win then again you’ve lost.

I don’t have eczema anymore, by the way, and I don’t end up drinking so much coffee to try to escape away from feelings that I think cause me discomfort (which then end up manifesting like a dream state symbolically, and could be labeled as psychotic), feelings as a child I wasn’t encouraged to feel free to express, and that’s just basic intelligence, and spiritual; so I wouldn’t have this whole calvacade, this whole potpourri, this whole assortment of things I hadn’t sorted out.

But no, I never was a dangerous schizophrenic at all, I think the dangerous paranoia lies quite rigidly denied on those making out there’s a danger that’s not there.

But again coffee is a dopamine re-uptake inhibitor, like ADHD medications, and anti-psychotic drugs (for “schizophrenia”) are drugs blocking the dopamine from being able to do it’s work (which actually causes dopamine hyperactivity again because the body then makes more of it, said to be the cause of psychosis); and I don’t think that a re-uptake inhibitor and an anti-psychotic doing all of that messing around with dopamine is in any way going to fix things, let alone that the “science” reported about it all is highly untrue.

And a lot of people never get a chance to sort any of this out, by some miracle I have.

Report comment

Njinsky,

You’re right, it’s not so unusual… and yet, most people in the general world have no idea that’s the case! Thanks for sharing more yourself!

-Sera

Report comment

Curious as to “lots of resources” one might offer a person to help reduce risk. While working the Red Eye as the Peer on the floor and triage team with clinicians working Live Rescues with BHL GCAL (Atlanta), the questions ultimately determine 1.) risk; 2.) access; 3.) means; 4.) intent to self/other harm. Resources generally imply immediate relieving of distress. Curious what “resources” you would certainly include. The graphic of Yay or Nay channels is interesting and basic to the mix. I prefer discernment and a lookee at whatever means other than 911/988 policing in response to expression of self/other harm are effective, protective, proactive and action based because action is necessary. You don’t quite go into solutions. Fast answers help. What are yours? Here’s the thing. Strategy and action mean perhaps a “solution” to distress and discomfort. I really want to know because I advocate for not asking the Q but rather delineating and discerning options to getting to what’s at heart, really. Since we both, I’m guessing, inherently (know) that calling 911/988 in the face of suicidality/ideation = imminent Death at the heart of the system, hospitalization, clinical and medical invasive drug treatment and psychiatric torture, please bring up and address solutions. We can go from there.

Report comment

I’m not sure that I’m entirely following your post, Jen. This article wasn’t about “solutions,” but about that particular question, its harms, and the reality that providers exhibit dangerousness to us on many occasions. I also disagree that resources need to mean solutions. It is this idea that supporting someone through suicidal thoughts necessarily means that our actions must be designed strictly to get rid of the suicidal thoughts. Sometimes, the best “solution” is just being willing to be with someone in the darkness because “solutions” aren’t really possible at that time. We don’t have housing or steady income to give. We can’t raise the dead when someone’s grieving. We can’t zap away emotional distress, and when we temporarily numb it sometimes it actually gets in the way of someone’s ability to move through. The approach we use encourages validation, curiosity, vulnerability (including sharing on the part of the supporter), and community (looking at ways of expanding connections that might tether someone to this world), etc. But we also do all this without the agenda of making someone not kill themselves. Rather, we are looking to support them in the moment, and suicide “prevention” is a common side effect of that. There’s no way to write out easy answers, because the context of people’s lives are unique to them. As to resources, if you’re asking what the infographic is referencing then what I’m proposing is that people who can’t discuss suicide with someone without resorting to force etc have lists of on-line Alternatives to Suicide (or similar) groups, peer support lines that do NOT call 911 (Trans Lifeline, RLC’s Peer Support Line, etc.) on hand so that the person at least has the space to talk about where they’re at without being under threat.

-Sera

Report comment

Awesome Sera. Love this answer and wisdom

Report comment

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/quebec-woman-missing-two-years-found-windsor-1.5585850

I left a few comments on the MSN version.

There are several things wrong in this CANADIAN news article. Number one. She was not “found”. She was “caught”.

Number two. There should be a law against journalists to post your picture nationally, especially if you committed no crimes.

Yes she was “found distressed”. If I was on the run from handlers, I would be distressed also. SHAME ON YOU, Canadian psych. Well we know what is in store for her.

We know it is control and forced chemicals and we know the reason they have to keep you inside while using the chemicals IS because of the very real effects of them causing suicide.

So they have to watch, don’t they.

If she commits suicide once outside, it’s her “MI”.

Tell me what options are there for her? She obviously lived outside of the system, perhaps not as some might like. If I don’t like the way someone lives, I can report them, AS long as they are low income.

I cannot report a psychiatrist, except to his own parents.

Report comment

Sam,

There are so many terrible stories out there of these sorts of things happening. I wish we could all do a better job of understanding and sharing with one another the laws around how to successfully evade this sort of force. For sure, it seems ridiculous that basically a nationwide search could be issued and sustained over years for someone who clearly didn’t want to be caught. The story is so vague that I’m not sure what on earth to make of it, but it’s frightening nonetheless.

-Sera

Report comment

I fear the “real story” never comes out in news articles. It is short, since people tend to have short attention spans lol, it seems to work out.

However, her story I am sure is the long one, and most people are not interested in that story presented by the individual.

The journalist is happy he covered the news, the cops are happy because they served psychiatry. Not the law.

I wish cops would start complaining about having to be hound dogs for psychiatry.

Their jobs should be related to crime only.

Report comment

“Their jobs should be related to crime only.”

Torture, kidnapping, maiming and killing are related to crime. Retrieving documented proof of those crimes is related to crime. Failing to perform your duty because you have a doctor on the phone telling you to commit that offence is related to crime.

It’s almost the perfect symbiotic relationship between organised criminals and the State. Who better to corrupt that a psychiatrist? And what are the chances of anything being done about it even with the proof? Certainly wouldn’t be relying on the authorites such as AHPRA (where you are referred to make dead end complaints). They go way beyond incompetent. I get the feeling that this is where the people go when even the hospital doesn’t know what to do with them anymore, give them a job as ‘investigators’. First year involves investigating where the toilets are. I’m being cynical of course, I just assumed that the regulatory body governing medical professionals would know that a Community Nurse who has no prescribing rights (because they are the ones that licence them) would know he is not allowed to authorise the ‘spiking’ of people he wants to kidnap. Silly me thinking they would know that without me explaining it to them in detail, only to be ignored. A Federal body no less.

We had a Police Commissioner here may years ago Sam who took the job with the opening line of “we’re moving into crime in a big way”. And boy did he mean it. lol

This was a case that interested me at the time

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easton_affair

What isn’t mentioned in the wiki is that Ms Easton was a lawyer who was required to present to the court where she had obtained the documents she had tabled (I believe). Between a rock and a hard place, and doesn’t look like anyone bothered to ask if she was suicidal. She gassed herself in her car four days later. No mention of chemical imbalances I note. It was a political football for some time, with the family finally deciding to put it to rest.

Report comment

Do you think Canada is a bit more extreme because of our funded system? I kind of assumed that we were like the U.S., but when I share stories and fears it seems almost cartoon in comparison at times. Not saying it isn’t a horror show everywhere, just a bit more complicated to escape. I still believe that dying is the only way to guarantee you never get put back. Is that just me? I knew that if I disappeared to save my life there would be a nation wide hunt to “save” me from freedom. I wanted to leave Canada completely, but even when I crossed the border and back was told I had to go back to my own province immediately. How did he know I was avoiding home if they weren’t watching? I’m Canadian, why would I have to check in at home?

Report comment

I think the “care” is basically the same everywhere. Or so it seems.

What goes on in Canada is that no one is smart enough to make up their own minds, or take the helm.

One GP or specialist or psych just copy your file. That is it.

This sharing of files, NEVER had a damn thing to do with care.

If I sit with my friend over tea and gossip to her about a person 3 doors down, and then that person comes over, how will my friend see that person?

Canada loves to be “modern”. I’m surprised they did not copy “open dialogue” as of yet.

Besides, they would mess up a good thing.

As far as where it is worse, I have no clue. I just think of each individual who is caught in this garbage.

Report comment