49 people died in a club in Orlando, Florida at the hands of a man who is now dead, too. In only a few hours time, he destined himself to be forever made infamous as one of an increasingly long line of ‘shooters’ that have sent our nation on a desperate search for who or what to blame. I never met this particular ‘shooter,’ but in my teens I did meet one.

Here’s how that went:

I entered college eleven days after I turned 16. It was great because I was on my own and out of the house where I grew up for the first time ever. It was also terrifying because I was on my own and out of the house where I grew up for the first time ever.

Why I ended up in college at a relatively young age is a long story, but suffice to say it had to do with equal parts privilege, abusive home environment, and difficulty fitting in at my hometown high school in Greenwich, Connecticut (for so very many reasons).

The short version of the story goes like this: Things were really bad (and getting worse) between my mother and I, and I’d started to skip class and do pretty poorly in school. She thought to ‘get me under control,’ she’d send me off to boarding school. So, she paid big bucks to some educational consultant to ‘make it happen.’ But, that high-priced hire instead suggested a college that accepts kids who have finished at least their Sophomore years, and I got hooked on the idea. So, upon acceptance, I dropped out of my Junior class, and then in mid-January, off to college I went.

I muddled my way through my first semester, even though I was sometimes so scared that I shook and I couldn’t feel my fingers when I tried to write. I also didn’t really make friends in those first few months, although there were people I admired at a distance in my entering class of twenty other kids. Fortunately, in my second semester, I started to form some connections.

One friendship that began to blossom was with a young man who came along one semester behind me. He was just as scared as I’d ever been. He explained that his family had been very strict, and it felt weird to him to stay out late, even though freedom was at his fingertips whenever he wanted it now. Gradually, he loosened up, and we took long drives together late at night. (I’d managed to acquire a somewhat old, but relatively reliable used car by then.) He told me about the girl he liked who had also played violin in the same orchestra in which he’d played back at home in Montana, and that his favorite song was Lady in Red.

Eventually we drifted apart. I don’t remember why, exactly. I just remember that the last time I saw him, it was one semester later (my third) and I was crossing over a little foot bridge. I looked up at his dorm, and he was gazing out a second floor window in my direction. Our eyes caught, and then we both looked away.

I left after that semester, and I’m glad I did. Because the following January (20 years to the day before the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary took place), he picked up a gun and became one of the first well-publicized school shooters spoken of in the media. Although more were injured, he only ended up killing two people. One of them was a boy (Galen Gibson) toward whom I’d harbored a longstanding crush. (He was one of the aforementioned 20 in my entering class.)

The court proceedings and media chaos that ensued in the aftermath assembled various characters who bickered back and forth about whether his motives were racially based, or the result of such psychiatric phenomenon as ‘paranoid schizophrenia’ or ‘narcissistic personality disorder.’ Incidentally, I’ve had contact with him off and on in the last few years, and he says that he never received any ‘mental health’ treatment after he was convicted of all 17 counts that stood against him and sentenced to two life terms in prison. He says that his reasoning and the events that transpired that January are a blur. (I have my own theories, but none of them are easy or fit nicely in a box as most would prefer.)

Since that time, there have been so many more tragedies, and so many more heated (and often futile) arguments grappling with why. Don’t get me wrong. I understand the need to make meaning. It’s not just so that we can find peace in what’s come to pass, but also so we can mend the gaping hole in our collective illusion that the world is a ‘safe place’ moving forward. Because without patching that up, it’s hard to feel okay about running errands, and letting our offspring out of our sight to go to school and living our regular day-to-day lives in any way. I should know. I have to intentionally put effort into turning off the ‘what if’ switch in my brain every day.

So, we choose those explanations that feel furthest from ourselves and at least sound like they’re real. In our current climate, that most typically amounts to he was a ‘terrorist,’ or he was one of ‘the mentally ill’ (and sometimes both). Although I personally spend more time arguing against the ‘mental illness’ piece based on my work and life experience, both answers seem to offer a similar benefit: They are two things most people feel they themselves could never become. It’s safety wrapped in distance wrapped in pat words (wrapped in so much ignorance and hate). So neat and tidy!

Except. Except that neither one (not ‘mental illness’ nor the ‘terrorist’ designation) is particularly finite, and both are entirely movable by those in power who are free to lay those labels wherever they choose, either before or after something happens. Whatever serves the purpose at hand. Of course, this generally makes them utterly meaningless as serviceable ‘reasons’ why it all happened in the first place, but no one seems to bat an eye or name that problem (at least not too publicly), or recognize them for what they truly are so much of the time: Tools of social control.

I don’t think I’ve ever used the term ‘mental illness’ as much as I am in this piece (and please do note the quotations in each instance), but here it goes a few times more: It seems such willful ignorance that people accept ‘he was mentally ill’ or ‘it wouldn’t have happened if he were in treatment’ as any kind of answer in these sorts of situations, and especially since so many in question were in fact in treatment of some kind. (I sometimes hate to acknowledge this point, because certain groups will hear it as affirmation that ‘they’ were ‘mentally ill’ since they sought some sort of assistance, when in fact, I mean it more as a note that so many of us struggle at some point in our life and are met with ‘help’ that does not ‘help’ and sometimes drives us further into the abyss.)

As aforementioned (but worth saying again) I think the driving force behind the acceptance must be to not feel paralyzed from all the fear of the not knowing and randomness of life. Or to not look too close to home because doing so might point the finger back at some of us.

The logic is so loose. Why is it seen as an acceptable ‘answer’ to say someone was ‘mentally ill,’ when so many who are diagnosed don’t harm anyone? (Never mind that there is no objective test for these supposed diseases of the mind, and psychiatrists can’t even agree which ‘disease’ someone has half the time.) Even if the quality being blamed does exist on some level (as in, he was in fact diagnosed or has been struggling emotionally in some way), correlation does not mean causation. It’s almost just as silly to say that he did it because he had a psychiatric diagnosis, as it is to say he did it because he was 20-something (simply because of the broad base of evidence suggesting youth is somehow tied to certain crimes).

There is always more to the story. Someone who hears a voice saying to kill another doesn’t have to be any more likely to act on that order than I am when my own mind indicates to me that I should ‘strangle a person’ out of frustration. (Although admitting the former is certainly likely to land one with a psychiatric label, who among us has not had such a thought?) Most of us contemplate ending our lives at our own hands at some point, yet few of us act. The majority of kids at college get drunk, are full of hormones, and get rejected at some point, yet most of them do not rape. Clearly there are other layers and influences at play.

Similarly, why are we so quick to accept the answer of radicalization, as if it were some far off and foreign thing that is not of our own culture? These explanations seem of similar ilk. If we can accept Islamic radicalization as a full response to explain away something terrible, then how about hate radicalization in general? Like racist or misogynistic radicalization, for example? Or the elements of Christian radicalization that so many use as justification for their horrific disposition toward those who do not live up to religious man-plus-woman expectations?

Why is it so easy for people to see one as a systemic issue applicable to a whole group of people (and that their often willing to go beyond the law to attack), while they view the others as ‘isolated incidents,’ or a good thing gone off course, and that perhaps was even somehow (in some cases) still fueled by something akin to ‘mental illness,’ too? In spite of the stark reality that many more people of color, women and individuals existing along the ‘LGBT’ spectrum are hurt by these supposedly ‘isolated’ ideas and individuals gone rogue, it remains easier to focus in on terrorism and ‘mental illness’ as the primary problems because it makes it more about ‘them’ and not ‘us.’ And, in the end, that’s what we need to sleep at night, right?

So, no, he did not kill them because he was mentally ill or because he was of a different culture that we do not understand or have demonized for our own solace. He killed them because he was violent. He killed them because he wanted to and he had access to guns. He killed them because he felt alienated from and angry at society. He killed them because he felt numb to everything but intolerable indifference (sometimes drug-induced). He killed them because he’d been taught to have hate and rage in his heart, and to believe he was somehow righteously justified to act upon it.

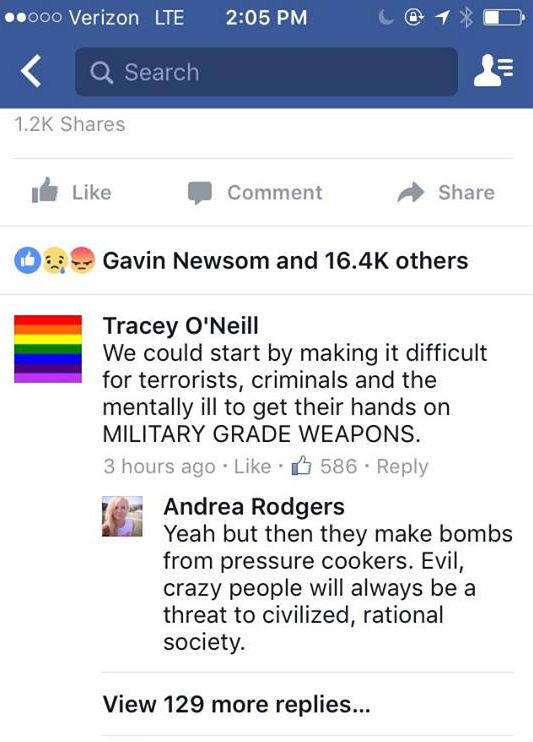

49 people died in a club in Orlando, Florida last night, and it (unsurprisingly) took less than 12 hours for both terrorism and ‘mental illness’ to get pegged as the culprits. Facebook posts like this one scored thousands of likes a piece by mid-afternoon.

49 people died in a club in Orlando, Florida last night, and it (unsurprisingly) took less than 12 hours for both terrorism and ‘mental illness’ to get pegged as the culprits. Facebook posts like this one scored thousands of likes a piece by mid-afternoon.

But, he didn’t do it because he was mentally ill. Whatever his allegiance with various groups, ‘terrorist’ is also not an adequate answer. (Perhaps, instead of these factors, some 200 anti-LGBT bills introduced in the last handful of months might have provided some of the fuel here?) Saying so might bring some people a vague sense of peace for all the reasons I’ve named above, but what gets lost in all this false ‘fact’ finding is the very real harm done along the way. When violence is conflated with ‘mental illness’ (or particular religions, as the case may sometimes be), the price we pay for that imaginary sense of security are the very real lives of those we’ve deemed worthy of all the blame. They become our ‘fall guys,’ if you will, simply so that we can feel like we’re in ‘the know,’ and post angry Facebook diatribes demanding ‘action.’

In truth, these attitudes push us toward force and oppression and even more hate. These ‘reasons’ compound the underlying problems that drive the violence, and lead many people to feel somehow ‘above the law’ in their efforts to control future outcomes. How sad that our fitful efforts to increase our safety in the world, do nothing but tear it all down.

Yes, what happened in Orlando was a tragedy, but it will become no less tragic if we comply with those forces that would have us blindly sacrifice more innocent souls to our drive for easy answers. There are no gods waiting to spare us further loss if we continue down this path.

The Government and Big Media’s latest attempt to ostracize, marginalize, periferize, and warehouse an otherwise easily exploitable population; luckily we DVM-V Diagnosed Humans are stronger and more intelligent than to let intollerence, stigma, and hatred permeate and saturate the main stream ethos and collective unconscious of others.

Report comment

Thanks for reading, TranspersonalPardigm. We are smart, but need a louder voice and more outlets to be heard on… I hope with the shift in what constitutes ‘media’ these days, our voices is getting out there more!

-Sera

Report comment

Agreed

Report comment

The intersecctions of this mass shooting are sickening. I think some people are just pure evil. Blaming drugs and diagnoses get us nowhere. He was raised and fed a daily dose of American colonized hate. Politicians have to stop hiding behind the shield of blaming Islam/Muslims/Mentally Ill. The time is now for us as citizens to stand up and say no more hate, no more…no more.

Report comment

Thanks for reading and for your comment, Iden. I stand with you in complete agreement. -Sera

Report comment

“But, he didn’t do it because he was mentally ill. Whatever his allegiance with various groups, ‘terrorist’ is also not an adequate answer.”

On the terrorism point, the shooter begged to differ; he took the time from his rampage to call 911 to pledge allegiance to ISIS. What else did he need to do to demonstrate his terrorist motivation? And how do you know that he was not mentally ill or that mental illness was not a factor? Reports from his former wife and co-workers paint a picture of an individual who was clearly unwell.

Report comment

As aforementioned, the ‘he’ through much of this article refers to the many ‘he’s who have committed these violent acts and not any specific one.

However, to your point specifically: This particular person made all sorts of different references to different terrorist groups, as best I can tell… Not one consistently.

And what *is* ‘mental illness’ precisely? There is no test for ‘mental illness’… There is the observation that some people are struggling, in distress, in altered states, suffering in some way (all varies with the person), and that is what earns them the label… But what does it REALLY mean? Someone may earn such a label for being suicidal, but the underlying issue is homelessness (for example), and not a brain disease. Others may be labeled as ‘mentally ill’ simply because someone in power doesn’t like or is uncomfortable with how they are living their life (e.g., diagnoses that have existed in reference to trans people, individuals who are something other than heterosexual, or enslaved people who tried to escape, etc.).

We can certainly say that people who do these things are ‘unwell’ on many levels, but suggesting they are ‘mentally ill’ suggests that they are of a specific group that is clearly definable and not subject to interpretation… It suggests that we *know* what ‘constitutes’ mental illness and thus leads us to the (erroneous) belief that we can identify such people in the future and prevent them from doing such things (a belief that leads society to hurt many people)…

In some ways the terrorist designation is similar… It can be applied by people in power in ways that make sense to them, but can be based on wildly disparate characteristics… Is this guy a terrorist because he called himself one at some point? Eh, maybe. But what does that really mean?

THAT is the point of this article… That these things are ALWAYS more complicated… That these labels people feel free to apply with such confidence do not have very clear definitions, and their application leads to two great harms: The abuse of and discrimination toward all people who are apart of the same group or possess characteristics that associate them with that group in some way… And the unspoken permission given to society to ignore some of the societal ills that are really to blame …

-Sera

Report comment

Few things are harder to shake than cherished notions. A cherished notion- that plentiful guns and being ready to start shooting at a second’s notice are what keep the nation safe- is at stake here. For such mentalities, everything must be done to save the cherished notions; even arresting people for not carrying firearms in public is better than taking precious guns out of (AAAAA) circulation. (For years I’ve been waiting for the NRA to promote automatic weapons for the blind, because they can’t see what they’re shooting at).

Report comment

My initial thoughts about this predictable turn:

Hmm… already, in the wake of this horrible tragedy of the 50 plus people killed at the Orlando gay nightclub, bullshit about the shooter being “bipolar” and this being an explanation for his actions is starting to spread.

http://myfox8.com/2016/06/12/orlando-shooters-ex-wife-calls-him-bipolar-abusive-unstable-very-short-tempered/

I am sure this illusion of “serious untreated mental illness” being the cause of the shooting will be seized upon to justify more coercion, more forced drugging, and more scape-goating of people given ridiculous unscientific labels like bipolar and schizophrenic.

And the illusion will grow that if only the shooter had been confined or given drugs at the right time, that this tragedy could have been prevented…. yeah right.

Meanwhile, little consideration will be given to the great likelihood that this man who committed this heinous act was likely himself abused, neglected, and/or discriminated against for long periods of time, had no one to talk to about it, and gradually internalized more and more hatred and sense of alienation that eventually led him to kill.

Report comment

Thank you, BPDTransformation. I fear you’re right on all counts… It’s much of what I’m referring to when I referenced how societal responses do little other than make the violence worse by pushing force and more oppression, etc. What happened in Orlando is tragic, and unfortunately, so is what will follow.

-Sera

Report comment

Sera,

This paragraph is a bit problematic:

“So, no, he did not kill them because he was mentally ill or because he was of a different culture that we do not understand or have demonized for our own solace. He killed them because he was violent. He killed them because he wanted to and he had access to guns. He killed them because he felt alienated from and angry at society. He killed them because he felt numb to everything but intolerable indifference (sometimes drug-induced). He killed them because he’d been taught to have hate and rage in his heart, and to believe he was somehow righteously justified to act upon it.”

Saying, “he killed them because he was violent” is kind of like saying, “Grass is green because it is green.” Explains nothing. Most of the rest refers to proximate causes, not ultimate causes based on personal relationships and the emotional environment in which someone grew up.

The part about being from a demonized culture on the other hand, may in fact be part of the explanation. The United States has done tremendous damage to contemporary Islamic cultures (as they have done tremendous damage to us), killing hundreds of thousands of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan during invasions mounted on false pretexts of weapons of mass destruction etc. This stuff does matter; our killing of innocents in Iraq and Afghanistan creates hatred, alienation and the desire to strike back. It’s uncomfortable to admit, but the US is not 100% pure or right in its invasion of Middle Eastern countries. Two sides to every story.

To get a sense of what was going on in this guy’s mind we’d have to know more about his family background, key relationships, cultural/religious affiliations, and most important the quality and tenor of his relationships to family and friends throughout life. I’m willing to bet that during key formative periods of his life he was seriously emotionally neglected, abused, discriminated against, and marginalized. Someone growing up with two genuinely loving parents in a secure, loving family almost certainly would not randomly decide to walk into a nightclub and kill 50 people. Mental illness doesn’t make people do that either, since it is a ghost. Bad relationships, neglect, trauma, deprivation, stress, and isolation are almost always the ultimate culprits.

Also Sera, did you know that when you say, “between my mother and I” it’s actually, “between my mother and me”? As an English major can’t resist correcting that 🙂

Report comment

BPD,

Fair enough. I more or less agree with you on the ‘violent’ part… That sentence was more about *access to guns* then being violent/why he was violent. That’s how I meant it, anyway. (I.E., As a statement about access to guns.)

I also agree that there’s much more that can be said about why someone becomes violent in terms of their upbringing… I’ve written about that before, and just made a decision here to focus more on the what it’s NOT about then write at length about what it *is*… The isolation, alienation, and hate in heart pieces are meant to allude to much of what you write about more expansively here.

Thanks for expanding upon it!

-Sera

Report comment

if sera’s english is being corrected – i wonder what will happen with mine. that is one of the reasons why i am reluctant to comment here anyways and the last sentences of the previous comment just nurtured my nervousness.

still i wish to express how great this text is. the paragraph that has been found problematic is one of my favourites. thank you sera for taking time to write this clear, clever and much needed counter-analysis!

Report comment

Thanks Jasna… (And if this is the Jasna I suspect it might be, then good to hear from you!)… I like that paragraph, too…

And actually, I’ve been thinking a lot about my concession on the point of ‘violence…’ On the one hand, I agree that it’s a circular argument (he committed violence because he was violent), but on the other hand it’s also true that one of the greatest *actual* predictors of future violence is past violence, and so I think it’s meaningful on some level, all the same.

In any case, thanks for reading and overcoming your reluctance to comment. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Steroids. Androgenic-anabolic steroids. That’s pretty well established.

Of course, many people use them and do not go nuts. But people who use them go nuts more than people who don’t use them do.

Report comment

“Meanwhile, little consideration will be given to the great likelihood that this man who committed this heinous act was likely himself abused, neglected, and/or discriminated against for long periods of time, had no one to talk to about it, and gradually internalized more and more hatred and sense of alienation that eventually led him to kill.”

This is beyond parody. What exactly are you advocating, therapy for would-be terrorists?

Report comment

Errrrrrrrr….. no. I’m saying that the causal factors that drove this guy to kill are mainly psychological and social factors. Most terrorists are made, not born.

Where does it say therapy in my comment…

Report comment

I always point out that NAMI and other anti-stigma mouthpieces are constantly saying that ‘mental illness’ (whatever THAT means) is not more common in one country than another. So if “mental illness” is the problem, why are there such a disproportionate number of these random-type shootings here in the USA? And it can’t be “untreated mental illness” either, because our “treatment” rates are among the world’s highest. (Of course, the idea that the “treatment” itself could be contributing is rarely mentioned…)

So logically, the “mental illness” explanation has no legs. But as you point out, people aren’t necessarily looking for true explanations, just convenient ones.

—- Steve

Report comment

Really important points, Steve. Thank you!

I also think about this sort of thing every time someone says ‘it’s not about the guns… if someone really wants to do this they can use anything!’

Report comment

Yeah that is one of the stupidest explanations of the pro-gun people. Try killing 50 people with a pocketknife or a peashooter. Guns do not kill alone, but they greatly enhance the lethality, speed, and ability to kill of a murderous person.

Report comment

Well said, Steve. I will quote you directly.

I agree, let’s look at the REAL REASONS these mass shootings in the U.S. (radicalism, bigotry, misogyny, and relaxation of gun violence prevention measures, paid for by gun lobbies).

–Yoshie Hill

Report comment

Blaming guns I would call one of those convenient ones. People in the U.S. have always had guns. We haven’t always had mass shootings on a weekly basis. Not that I think this is comparable to Columbine, as I think the guy’s motivation has been made pretty clear.

Report comment

Oldhead,

“Pill induced” violence tends to be dramatic.

Report comment

Not sure what you mean as it relates to this?

Report comment

Oldhead,

The characteristic of drug induced violence, is that it tends to be dramatic and out of character – like the Orlando shooting.

Report comment

OK that’s what I thought you were saying. Guess we’re all waiting on any psych drug info to come out, so far haven’t heard anything.

Report comment

Fiachra, that ‘pill induced’ violence you mention is what Peter Breggin calls ‘medication spellbinding’. Basically, when on certain types of medications, especially psychiatric drugs, these can have profound effects on the individuals psyche and can drastically change their personality, including psychosis, mania, and/or violence. However, the individual has little understanding that it is the drugs that are causing the effects and instead thinks it is simply them and what they are feeling is natural. Which is why such effects are so dangerous because the person has absolutely no clue that it’s the drugs that are causing them to act so out of character.

I have a personal experience with such medication spellbinding. In my teenage years I took some anti-psychotic drugs (not my prescription, some people I knew took them because it made them hallucinate), yet when my own hallucinations kicked in I didn’t/couldn’t cognitively put two and two together (took drugs to hallucinate, then started to hallucinate), so I thought what I was seeing was real and freaked the hell out. This of course got me sent to a mental hospital where, if you can believe it, they gave me anti-psychotic drugs to treat my hallucinations that were caused by anti-psychotic drugs.

Report comment

Ragnorak,

You describe spellbinding very well. I was certainly spellbound, and there’s a lot of it about. It’s just swept under the carpet!

‘The shooter’ would have had at least a 10% chance of being on a neuroleptic (as any one else in the West would).

Report comment

Steve,

“….Of course, the idea that the “treatment” itself could be contributing is rarely mentioned….” – it IS rarely mentioned and it is also kept o off *research. Nearly every post 1st admission hospitalization I had was a suicide event, and when I stopped the medication – there were no more hospitalizations.

Akathesia can have different forms mine was acute and transitory – whereas SSRI might be milder but more long lasting.

The *University (hospital) where I had been treated had conducted research paper after research paper on the usefulness of the drugs that had caused my problems.

Report comment

In this case the guy was not diagnosed bipolar; that’s his wife’s assessment. We might hear otherwise, though. I have heard steroids mentioned, and that he’d bulked up at some point. Anabolic-androgenic steroids would do it.

I agree–Research hospitals are the worst. It adds the ego/career motive to the money motive, the ego-career is much stronger and more corrupting.

And then swapping stupid stories, here’s mine:

My SNRI akathisia lasted 24 hours and was treated as bipolar for three years, often with the original SNRI, with Abilify that orovoked akathisia overnight, which went on for a couple of months during what the main thing I ever said was this is unbearable.” (Know that one?)

I often mentioned that 49 was late onset for bipolar disorder, but despite having a PhD in psychology, I was a pitiable, typical bipolar patient resisting “my meds.”

It’s foul how the patient nicknames her chemical death. One of the last things I said to the last mental midget who thought I believed his plastic model of a neuron inhibited from re-uptaking serotonin by a mighty SSRI was, “they’re not my meds, they’re yours.”

By then I was in dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (DAWS), which no one recognized, despite my previous doctor’s wild notion that I had ADHD, not bipolar disorder, and should be on two stimulants and Prozac.

The tiny clown wth the 3D neuron toy had prescribed so much Seroquel (which minimizes your dopamine) that I stopped breathing at night on several occasions. I also prayed for death much of the day or night; that’s DAWS which is not helped by scrubbing every last dopamine molecule out of your nail beds.

Report comment

Go watch a bunch of fossil Westerns to find the stimulus. Practically any will do.

Report comment

Jeff Lieberman said James Holmes was merely troubled. So this one was a paragon of health.

Report comment

I think people are overthinking this. It was a violent political act, period. There’s not much anyone who’s not telepathic could have done about it except erase history. It certainly has nothing to do with the existence of guns. If someone in the club had had one the outcome might have been different. I haven’t actually heard much “mental illness” talk yet other than people equating violence with “mental illness.”

Report comment

I have to disagree, oldhead.

Comments on Facebook (such as the only I attached to this blog) mention it… Articles from the ex-wife mentioned it, and even a diagnosis has been named… It’s not been as bad as it could be, but it’s circulating.

Also, I’m not sure how it could not be about guns? People have been murdered without guns, but not generally at the volume as those incidents where there are guns (yes, I know there are exceptions to this, e.g., the planes on 9/11, but it’s a rarity)…

I appreciate what this Australia comedian has to say on the topic:

https://youtu.be/0rR9IaXH1M0

Well… I like his second-half less as he goes down the ‘crazy’ path in the second half and some other offensive bits… But worth a watch where guns are concerned.

The only thing I can agree with you on is that we will never be able to predict and stop all violence, and frankly our efforts to do so (much like the suicide prevention industry’s efforts where suicide is concerned) cause more harm than good in so many instances…

However, I absolutely do think that there are things we can look at that are societal influences that may have impact… For example, would this guy have done this if he didn’t live in a society that was so conflicted and violent toward people who identify as something other than heterosexual/cisgender, etc? Maybe… Maybe not, but it seems worth our energy to move toward a less hateful society and it seems inevitable that doing so would at least reduce violence.

-Sera

Report comment

Yes, of course he was reacting to all these things which are an integral part of this system. They won’t go away until the system is neutralized. As far as guns go, I’m not even getting involved in that except to ask who’s going to take away someone’s gun except someone else with a gun.? So all this “gun control” talk is more honestly a conversation about who gets the guns.

As far as “hate,” and relating this back to Richard L.’s comments under David O’s blog, hate is something which arises out of material circumstances and when it’s not distorted and permutated has a function just like any other emotion. Rather than attempt to get people to purge their hatred it might be wiser to get them to direct it at the right things. And I’m not talking about violently. (Don’t know why it’s necessary to emphasize that.)

Report comment

Actually the “mental illness” talk has been picking up. Bipolar especially, wonder why, whether he was in “treatment” & taking drugs. Doesn’t sound that way so far.

Report comment

Tragic how heroes with guns hardly ever appear when they are needed.

Report comment

http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/mentally-ill-man-shot-by-police-at-westfield-hornsby-on-day-release-20160610-gpgmfd.html

and can be quite dangerous when they do.

love the comedy sketch Sera.

Report comment

Oldhead

There was someone there with a gun; an off duty policeman or deputy I don’t remember which. And the person did engage with the gunman but it didn’t seem to help or to stop the carnage.

I disagree. I believe that guns and the ability to get them so easily in this country is a large part of this problem. People can talk all they want about Second Amendment rights and all that, but I do not believe that a person has to possess an assault rifle to take care of their SA rights. Assault rifles are intended for one thing and one thing only and that is destruction for the largest numbers over the shortest amount of time.

Report comment

I don’t have much interest in the so-called “gun control” debate from either side. I do have an interest in separating logic from emotion. The two most relevant facts I’ve stated elsewhere here:

— Americans have always had guns. It is only recently that mass shootings have become “normal” events.

— The only person who can take away someone’s gun would be someone else with a gun. So this is really not an argument about whether to have guns, but who gets to have them, and who decides.

Report comment

Mass shootings became normal events with the advent of the SSRI’s. Go back and start checking and you’ll find that with their appearance all of these things began happening. Now, hardly a week goes by without a big shooting taking place. The day after the murders in Orlando there was a guy who took his manager hostage in a Walmart store, both of them ended up dead. It’s become so commonplace that we don’t really spend too much time thinking about what happened. We’re getting used to it all.

Along with the SSRI’s came mass shootings. We may always have had guns but all of this didn’t start until the devil’s tic tacs came along. I still say that guns are the problem. Give one of these mass murderers a knife and see how many people they can murder at one time.

Report comment

You just explained that SSRI’s were the problem then changed it to guns. If it’s the SSRI’s people wouldn’t be misusing guns to begin with, right?

Report comment

“I think people are overthinking this. It was a violent political act, period. …… It certainly has nothing to do with the existence of guns.”

I agree. The slaughter in Orlando is not unlike the terrorist massacres in France and Belgium, where guns are clearly not a factor. Terrorists will get their arms no matter what. More facts need to come out, but political correctness may have been more of a factor. Why was this disturbed guy working as an armed security guard?

Report comment

This is not always true: “terrorist will get their arms no matter what.” It’s more subtle than that. Not everyone will get a gun no matter what, terrorist or non-terrorist. If guns are harder to obtain, some terrorists will certainly still obtain them illegally, but those on the fringes / those who are on the borderline of being radicalized will have a harder time getting them, or those part-timers without the necessary dark market connections will not etc, and fewer of them may obtain high-powered weaponry and carry out deadly assaults. Thus legislation and policy can make a difference, but only on aggregate, and has to be looked at in the big picture, not via speculating about individual events.

Report comment

Sera, I loved your article Suicidal Tendencies Part 1. What happened to part 2?

Report comment

Becky,

Thank you, and the trouble with all this is that I do best when the energy builds so that I feel like I just *have* to write something to get it out of my head. And other topics have felt more pressing than going back to that one, so I’m just kind of waiting to be re-inspired to return for Part 2. 😉 Hopefully you’ve found some value in the other blogs I’ve posted. 🙂

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

I believe that these mass shootings can be best understood as a form of suicide- as an effort to find more comfort in suicide.

Report comment

This seems to be becoming more & more identified as a “genuine” terrorist act, i.e. more than a loner getting fired up over stuff on the internet. So lumping it together with “psych drug” shootings and the like may be premature.

Report comment

The distressful experiences of his life and the fact that it was a suicidal attack seem more telling to me than the fact that it was a terrorist attack.

Report comment

What motivates the modern day kamikaze? This has to be a question for our time. There is a disrespect for life in general going on here. Not only for the lives of others, but for one’s own life, too. It seems very much a hate crime, but the extent to which self-hatred may have played a part is undetermined.

This guy, Omar Mateen, was carrying an AR-15, very popular of late among the multiple murder set, but do you think these law and order types will consider renewing the expired ban on assault weapons? Probably not. I imagine it’s back to the increased funding through “crisis in mental health” scare, and disarm the nut-jobs, but only those nut-jobs, legislative efforts.

Report comment

Interesting that this should happen on the eve of Murphy being given a green light by Congress. We should up the talk about psych drug murders and make people more aware of this.

Report comment

Interesting perspective, Steve. I’m not sure I’d necessarily agree… Can you say more?

Sera

Report comment

People fight for their politics and may risk death for their politics, but do not choose death for their politics unless they are living in painful emotional despair. Hence, most suicide bombings are promoted by political figures who find those most in despair to do their bidding.

From the reports that I have seen, I can only imagine Omar’s life as one of despair. He was raised in a desperate (fantasy) world of creating a holy government-in-exile from Afghanistan. His father taught him religious extremism in an environment that provided no affirmation for his religious upbringing. His first wife rejected him and ran away from him; this was a total humiliation to his concept of a marital relationship and manhood. His attempt to defend his religious beliefs with work colleagues (as his religion is increasingly attacked in the community) was met with ridicule (and a label of “mental illness”). A public display of affection between two men recently caused him to go ballistic (by his father’s account) because that appeared to him to be socially accepted while his religious beliefs seemed socially unaccepted. I believe that he chose suicide to end the emotional pain of his alienation from the community (his perceived rejection by the community), and chose a method that made a statement about his religious rejection of homosexuality. This seems more suicidal than political.

Report comment

Mateen’s ex-wife looked and sounded more “unstable” than Omar himself did! At least Omar didn’t try to play the victim when he was ranting about “killing n*****s” and mimicking the planes that flew into the World Trade Center. Calling “bipolar” people “abusers” is a hysterical and grossly dishonest way for sanists to manipulate the health care and legal systems into criminalizing Free Madness. Call me crazy, but I suspect that Mr. Mateen was groomed into becoming a killer by family members, coworkers, etc. who had, foolishly, decided to rest easy in their lives away from him AFTER they had treated him/made him feel like “toxic” waste.

p.s. Google “toxic families” and see how many webpages, books, etc. refer to Mad family members as the locus of the family’s toxicity.

Report comment

Comment removed.

Report comment

Excuse me, oldhead? Have you read the news lately? Apparently, Mateen was a self-hating homosexual who turned to alcohol in order to cope with the burden of hiding his sexual orientation from his hostile family. Name even ONE mass shooter who didn’t have a fucked up family. The violence we see is always but an echo of the violence we don’t see.

Report comment

“The violence we see is always but an echo of the violence we don’t see.”

I agree, this is always going to be the case. The root of violence lies in the self-loathing that people can feel thanks to the messages delivered by a toxic society. If we want peace, we must find it within ourselves, first, and embody it in the world. I don’t believe there is any other way.

Report comment

Exactly. Just as some sects of Christianity attack people who are LGBT and try to make said people believe that they are hated by God and are the most sinful people on earth, Islam in its most distorted forms allows LGBT people to be murdered in the name of Allah.

I suspect that this man was conflicted in so many ways that we will never know. Am not taking up for him or what he did, but if he was gay, he faced total and absolute condemnation in the strict application of Islam in its distorted forms. He didn’t seem to even understand that many of the Islamic groups that he supposedly pledged himself to were opposed to one another. He didn’t seem to be well informed about a lot of stuff.

Report comment

And he was certainly not alone in experiencing treacherous inner conflict–our nature vs. the demands of a toxic, judgmental, shaming, and marginalizing society. That’s not even limited to gay folks, it is across the board.

Some kill others as a result of social trauma, some kill themselves, some do both, some get physically ill, some live lives of quiet desperation, and some successfully individuate from the toxicity, heal, and get on with things without incident or fear, and in fact, go on to create great things for themselves and society, as a result of having experienced this level of trauma.

I’d be most curious to know what factors create these diverse responses to social trauma.

Report comment

Calling “bipolar” people “abusers” is a hysterical and grossly dishonest way for sanists to manipulate the health care and legal systems into criminalizing Free Madness.

Putting “bipolar” in quotes nevertheless indicates an acceptance of the designation as something real. At any rate if someone is abusing someone else he is an abuser regardless of his psych label. You’re calling domestic abuse an expression of “free Madness”? Why am I even arguing with this?

I checked your comment history and was surprised to see that most of what you write is generally intelligent and apropo. Don’t know what happened here.

Report comment

What happened, oldhead, is that you TOTALLY (deliberately?) misunderstood what I was saying. “Bipolar” does not “indicate an acceptance of the designation as something real”. I have NO acceptance for that – or any other – psychiatric designation. None, zero, zip. “Bipolar” was the sanist slur that was flung on camera by Mateen’s slandering, bigoted, drama-queen ex-wife. I used the word “bipolar” ONLY to give you and our fellow commenters an example of how Mateen was a VICTIM of abuse *before* he was an infamous perpetrator of mass murder.

Obviously, being Mad doesn’t give anybody a license to abuse others or themselves. But when Mad people are abusive to others or to themselves, their Madness should NEVER be exploited by *anybody* as the *sole* explanation for their destructive and/or offensive actions. In this instance, we know for sure that Omar Mateen’s family did not accept him (Mateen had to hide both his addiction and his sexual orientation from his family.), listen to him (They pathologized Mateen’s distress over their treatment of him as “bipolar”.), or respect the pace at which he was able to grow into manhood (They pushed Mateen and his ex-wife into marrying each other LONG before either of them were prepared to marry ANYONE.). Those actions are violent *even* when the people who perpetrate them are unaware that their brutal antics are pushing their victims into Madness and homicide. I DO NOT BUY the flimsy perpetrator-apologism of assuming and believing that whichever perps who sit atop the Totem of violence just “did the best they knew how to do”. Even if people shouldn’t be punished for their ignorance, they should still be blamed for the destruction that their ignorance has wrought upon society. The hopeless inaccuracy of post-mortem psychiatric “diagnoses” is yet another reason why America’s “court of public opinion” should quit scapegoating Mateen’s “severe mental illness” for his crime. By all accounts, Mateen led a self-sufficient and unremarkable life. Though he seemed to have been completely alone in the world (Based on the news reports, he’d had no friends, nasty coworkers, and a rotten family – all factors that MAJORLY contributed to his killing spree.), he did graduate community college, fully support himself through his long-time employment as a security guard, and maintain the apartment he lived in entirely by himself. Mateen’s employers demanded him and all of their other employees to take routine background checks and psychiatric exams. During the nine years that Mateen had worked in the security industry, he had never failed a single background check or psychiatric exam. Similarly, Mateen had never been under the “care” of any psychiatric clinicians. Usually, Mad people’s health, academic, social, legal, and occupational histories aren’t nearly as presentable as Mateen’s was. Our refusal to make the specious “success” = “health” argument DOES NOT absolve us from scrutinizing the premises that (a) Mateen was “severely mentally ill” and (b) that his “illness” led him to kill 49 people. Even the people who *do* (and, to repeat myself, I DON’T) believe in psychiatry won’t label anyone as “mentally ill” until AFTER they’ve exhibited more social, occupational, academic, legal, or domestic “dysfunction” than Mateen did, prior to his deadly rampage. So, it’s ridiculous for you to troll my comment history and negatively compare my current comments to my past comments. I AM right. Free Madness and Free Mad people ARE being oppressed whenever anybody – even you – decides to pigeonhole folks like Mateen into the “psycho killer” trope. Whatever Madness that Mateen may have been living with had, clearly, been a mere subtext in the totality of his life, and only a CONSEQUENCE of his horrible familial and professional environments. There’s no chance for any of the key players in Mateen’s life to EVER outrun the boomerang of culpability they’ll rightfully endure whenever public speculation lands on the role – if any – that Mateen’s supposed “bipolar disorder” may have had in the murders he committed. Oldhead, you really ought to get more focused on stopping the SPREAD of violence, rather than the public’s cogent UNPACKING of it. I’m glad the moderators deleted your vicious comment to me. It was unnecessarily aggressive and, like your latest comment, COMPLETELY out of step with what’s *really* going on.

Report comment

So, oldhead, people who are shunned, shut-up, and slandered by everyone they know “lose their right” to strike back at a society that turns away in complacency from their humanity-corroding plight? I don’t think so. Human beings are not expendable, and it’s the recklessness and carelessness of such an INCOHERENT mindset which started a landslide of violence that has culminated (thus far) in America’s bloodiest mass shooting EVER. It is human expendability – more than guns, “mental illness”, misogyny, or anything else – which is responsible for our increasingly dangerous world. Read the New York Times article, “Thinking Against Violence”, by Natasha Lennard and Brad Evans.

Report comment

Strike back at “society”? Who is “society”? Wife abuse is striking back at “society”? Do you volunteer to symbolize “society” for some equally confused and violent person?

Report comment

To oldhead,

First of all, I’m not violent. Fortunately, I’ve had the opportunity to both give and receive a lot of unconditional love throughout my life. Not the case for all of these mass shooters, which was my whole point – the point you keep on missing over and over again. Read the article “Excluded from Humanity: The dehumanizing effects of social ostracism” in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Neglect is a form of aggression too, and words are as deadly is bullets. You will NEVER be able to escape those two truths, no matter how well you *think* you are at living as an island.

Society is you, me, the people you know, the people you don’t know, the people you don’t want to know, and the people you (here’s more of your precious entitlement again) “shouldn’t have to know”. We are all part of society, despite the fact that people like you are good at tricking yourselves into believing we aren’t. Weak and greedy people like you may push some members of our society waaaay over to its remote and narrow margins, but you’ll never push those scapegoats out of our society altogether. These realities of life answer all the questions you’ve asked and could have answered yourself, if you had really tried to nudge yourself out of MEEEEE-mode. Society is created by and composed of every human being, both dead and alive. So, yes, wife abuse (and husband abuse, child abuse, cyber abuse {of which you are a perpetrator}, etc.) IS striking back at society. Every one of those victims/wannabe victims/forgotten victims/ignored victims are here in our society to stay, whether you want them around or not! And *SOCIETY* does NOT belong in quotes. There is no human achievement or failure more REAL than the societies we’ve built and destroyed over the last several dozen millennia. No society or member of society is a “symbol” for anything or anyone else. “In-groups” of societies always “symbolize” their social outcasts as “lone wolves” whenever they know that they’re too lazy to get smart about public safety and must, therefore, settle for the semantically reduced odds of reaping what they’ve sown, in lieu of putting forth the MASSIVE effort to raise a literal and sustainable level of societal harmony. People like Omar Mateen are firmly ensconced in and evenly dispersed throughout our unstable and callous society. So, trust me, they don’t require any “symbol” in order to represent themselves. Those “confused and violent” people are perceptive enough to figure out how society REALLY works and brave enough to *show* you how society REALLY works. A person like you, oldhead, who needs to take sociology and political science lessons from killers is, no doubt, the REAL criminal. You are NOT a society unto yourself. None of us are. Grow up and start treating everyone as though you can’t kick them to the curb, because the truth is that, in most instances, YOU CAN’T!!!!

Report comment

Last post. I didn’t call you violent, for the record. You might practice reading for comprehension. Otherwise, who am I to argue, you obviously have it all figured out.

Report comment

To oldhead,

“Do you volunteer to symbolize “society” for some equally confused and violent person?”

Here, you are claiming that I’m choosing to substitute for and/or speak for people who are (a) as “confused” as they are “violent” (b) as “confused” and “violent” as I supposedly am or (c) some of a and b. My reading comprehension is just fine and dandy. It’s your intellect that needs a tune-up. To do that, you need to crawl out of your ego-cave and start interacting with people in a more reciprocal and civil manner. Most forms of intelligence are cultivated through productive social interactions, and perhaps those social interactions could sharpen the mind and strengthen the moral backbone of even the most basest of simpletons, such as yourself. I really wish you the best of luck in, one day, completing this elementary stage of human development.

Report comment

the most basest of simpletons

Report comment

That’s called a typo, uprising. I meant to say just “basest simpletons”.

Report comment

Comeon oldhead, putting “bipolar” in quotes in no way indicates an acceptance of the designation as real. It means you are acknowledging that other people use this word to mean something, but that you yourself question its validity and usefulness.

Report comment

Comeon oldhead, putting “bipolar” in quotes in no way indicates an acceptance of the designation as real.

Come on BPD — out of this whole nonsense the part that bothers you is about the semantics of “bipolar”? What about the assertion that wife abuse is an expression of “free madness” and an understandable way of “striking back at society”?

Report comment

Oldhead, avoiding my point doesn’t change its validity: Noting that another person uses the term “bipolar” in no way constitutes acceptance of its validity for oneself. I’m not the only person in the thread who called you out for this illogical non-sequitur comment. Try acknowledging you might be wrong for once…

As for what you’re talking about, can you translate that into English?

Report comment

BPD, we’ve been through this before but if it’s important I responded with a new thread here:

http://www.madinamerica.com/2016/06/no-he-didnt-kill-them-because-he-was-mentally-ill-why-tragedy-struck-in-orlando/#comment-89576

Report comment

He killed them because he wanted to and he had access to guns.

Really ?

26 years ago, Cuban refugee Julio Gonzalez killed 87 people when he set ablaze Bronx dance club Happy Land in a jealous rage after an argument … http://www.google.com/search?q=happyland+fire

He Killed them because he had easy access to gasoline.

So anyway those ISIS people want to kill us so lets disarm Americans to make us all sitting ducks, ya that makes sense.

Report comment

Cat,

Do I think guns are the whole issue? No. Do I think they are a part of the problem in many of these scenarios? Absolutely.

I hear this argument about our need to have guns so as to not be helpless and be able to defend ourselves… But, could you point me to the scenario where someone arrives with the intent to gun down as many people as possible, and some citizen who was legally carrying a firearm while out on the town stops them?

Again, I find this comedy routine to be a useful reference:

https://youtu.be/0rR9IaXH1M0

-Sera

And, could you explain to me why the land with so many legal firearms is also the land with so many of these sorts of shootings?

Report comment

There’s the mystique factor. I see it in the guys who troll me when I mention that you’re more likely to die by gunshot in Switzerland, the gun fanciers paradise, with assault rifles in every house and a miniscule homicide rate, than here. (Their suicide rate is three times- probably only two times, now- ours, and 3 out of 4 are with guns).

Report comment

And everyone in Switzerland belongs to the army, everyone does a tour of duty and I believe that this includes women but I’m not totally sure about this.

Report comment

Yes, that was the deal for women getting the vote. Maybe some mossback thought they’d want to stay silently at home, the way they had for centuries. Alas, he was in error.

Report comment

Are we forgetting the psych drug factor?

Report comment

Ask your doctor why they never ask these questions on the news before taking commercial breaks for ask your doctor ads.

Report comment

Woman confronts man breaking into home, deputies say

Published 9:53 PM EDT Jun 10, 2016

FLAGLER COUNTY, Fla. —A Palm Coast woman confronted a man who invaded her home while she was inside with two children, WESH 2 News has learned… According to the report, the victim came from behind the hallway wall and pointed the pistol at the man and told him to leave the residence.

http://www.wesh.com/news/woman-confronts-man-breaking-into-home-deputies-say/40005218

But, could you point me to the scenario where someone arrives with the intent to gun down as many people as possible, and some citizen who was legally carrying a firearm while out on the town stops them?

It stops them before they get started, they target places they hope no one is armed.

Its just the stupidest thing in the whole world, bad people acting out with guns so good people should not be allowed to have them and be sitting ducks.

We should give up our right to self defense cause of ISIS terror wile simultaneously importing more people from middle east war zones. Really that’s the plan ??

The first semi-automatic rifle was introduced in 1885, the first semi-automatic pistol in 1892, and the first semi-automatic shotgun in 1902. You can’t outlaw 1800’s technology anyway, at least not for crooks.

Report comment

Hmmm… I asked:

“Could you point me to the scenario where someone arrives with the intent to gun down as many people as possible, and some citizen who was legally carrying a firearm while out on the town stops them?”

What you offered doesn’t really counter that…

I don’t know that I really have the energy for a full on gun debate. Honestly, I wish people could just have the space to grieve all that’s happened without needing to have any arguments at all… But it seemed necessary to put something out there to counter the scapegoating.

All I know is that the stats from this country verses other countries just doesn’t seem to hold up the arguments you’re offering, and in order to change the direction in which we seem to be heading, *multiple* things need to change…

-Sera

Report comment

It seems to me, from reading them, that a lot of this weapons advocacy seems to be from people who haven’t been in gunfights, but who have a secret desire to participate in one. Thus we have this craving for firepower with little understanding of the consequences of indiscriminate shooting.

Report comment

The second amendment protects us from tyrannical government and that is very important. Has everyone already forgotten that police kill more Americans then terrorists ?

Eric garner, Walter Scott, Samuel DuBose …

Americans 58 Times More Likely to Be Killed by Cops Than by Terrorists http://filmingcops.com/new-study-americans-58-times-more-likely-to-be-killed-by-cops-than-by-terrorists/

I cant prove it, that would be impossible but I believe police and government would abuse us much much more if they didn’t have to worry that the population has the ability to fight back. What the hell in 2015 we had protests , riots and cities burning it got so bad.

And why do so many American cops believe that shooting a mentally ill man dead for failing to drop a screwdriver is an acceptable outcome? Jason Harrison and Keith Vidal.

So what happened in Orlando was horrible but WTF Amercans fear much more for their lives when they see flashing lights in the rear view mirror then when they see a Muslim man and that’s the truth of it.

Terrorism Terrorism be scared be scared bla bla bla all day long on the TV bla bla bla… I am not buying it.

And I kind of like that when I go to sleep at night burglars and home invaders have to worry that I might not be a sitting duck if they pick my place. They have no way of knowing.

I don’t care if or if not someone arrived someplace in the past with the intent of doing a mass shooting and some citizen who was legally carrying a firearm while out on the town stopped them.

I so hope Crooked Hillary mother of mass incarceration hater of the second amendment looses the election. Crooked Hillary Clinton on “Superpredators” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALXulk0T8cg

Report comment

I agree with you that the Orlando shooter did not commit that violent act because he was mentally ill, but I disagree with your opinion that mental illness can’t make a person commit violent acts. I myself have been violently psychotic, and I can tell you that when I was delusional, paranoid, and hearing voices, I could not think rationally in order to not obey the psychotic ideas. It’s like being in a dream. I didn’t know it wasn’t real and I had no control over what was happening. I stabbed myself in the chest and swallowed bottles of pills because I thought God was telling me to do it to escape Hell and if I didn’t I would be damned forever. It wasn’t just a belief or idea that I could choose to dismiss; I really “saw” these things happening. I thought I saw the Apocalypse happen, and the world had descended into the Abyss and the people in it were actually demons and they were coming after me. Another time, I almost stabbed my father and brother with scissors because I was convinced that they were part of a satanic organization and they were going to grab me and take me down to the basement and sacrifice me to the devil. I was trying to defend myself. I thought I was an angel and they were going to breed me to make demon babies. I again thought I saw the Apocalypse happening. And I was going to get a sword to fight the shadow demons living on my roof. I was taken by the police to the hospital. I thought all the people in the hospital were part of the satanic organization that was after me to kill me. I thought they were pretending to be a hospital and were actually going to crucify me. I thought they put a microchip in my brain to track my thoughts and control me. It was terrifying beyond description! Again, I was 100% convinced these things were real and I couldn’t think rationally enough to distinguish between reality and psychosis. My point is that psychosis can take over your mind and make you commit violent acts. You can’t resist the impulses to act if you can’t think rationally. In those cases, anti-psychotics saved my life! When I was put on anti-psychotics (against my will), those delusions vanished!

Report comment

I don’t think that any of us are saying that you can’t do violent things when you are experiencing alternate realities that seem absolutely real and which you can’t separate from the consensual reality at the time. I don’t think that violence at the hands of the so-called “mentally ill” is the usual experience by and large.

I work in a state “hospital” and find from my own limited experience that most of the people experiencing alternate realities are not violent. There are a few but they are not the majority. Most people who are labeled as “mentally ill” have more chance of having violent things done to them by the so-called “sane” people than we find them carrying out violent acts against other people around them.

Thank you for sharing your experiences so that those of us who’ve never experienced alternate realities as you have may come to a little better understanding of what that feels like.

Report comment

Stephen, I just wanted to say that I love your thoughtful replies. The presence you bring here I find comforting.

Report comment

I thought my mother was trying to feed me rat poison, but I didn’t offer the kind of resistance that would have endangered life. Neuroleptic drugs didn’t do me any good, and could be considered a form of “rat poison”. The time frame for ‘leveling off’ the drugs was not a short one for me, and they could, in fact, have contributed to my confusion. I just want to make clear that sometimes matters are no so clear-cut as one might want to make them appear after the fact, and there are things that only additional research might be able to get to the bottom of, providing, of course, that it isn’t biased as so much of the research taking place today is biased.

Report comment

truecelt,

I’m in no position to tell you that your story and experiences aren’t real. Thank you for sharing them.

However, I don’t think that changes the fact that what gets labeled as ‘mental illness’ isn’t really a finite *thing* that can be said to be the cause of anything in particular, and that it’s always more complicated than that. We don’t really know what brings people to the point that you describe having experienced or that there’s really any one clear reason. We do know, though, that violence driven by altered states is really rare and (when it happens) often not driven by those states alone, and that psych drugs often don’t help, don’t help enough, or can make things worse…

Most importantly, the blog really is more about the reality that it is all most often way more complicated than pegging some simplistic cause, that we need to stop ignoring our societal ills and biases in how we identify what is ‘wrong,’ and that scapegoating a group in the way that is so common when bad things happen is not only misguided and harmful.

Thank you again, though, for being willing to share so much of your own story.

-Sera

Report comment

Hi Sera,

Thank you for your reply. I agree with you that the mentally ill shouldn’t be used as scapegoats in society and society’s problems certainly shouldn’t be blamed on mental illness. And mental illness is indeed complicated. Those two times I described when I was profoundly psychotic happened within months of stopping my anti-psychotic meds. I was in a frenzy of mania and was capable of anything, and I had no control over my mind or what I was doing. I am normally a very peaceful person who wouldn’t even step on a ant. Psychosis makes you into a completely different person. I am too scared now to ever try to stop taking my meds again!

Report comment

Truecelt,

I am in absolutely *no* position to tell you why you have experienced the things you have experienced… but I just want to make certain that you are aware that many people experience disruptions when they first go on or off psychiatric drugs… And that those disruptions commonly have far more to do with the chemical changes related to the drug than anything to do with the individual themselves… Even though it’s very commonly used as proof of need of those drugs, which is quite unfortunate.

Again, no idea what that means for *your* situation, and I make no recommendations about what you should do… But just wanted to put that out there.

-Sera

Report comment

I want to second what Sera stated here. These drugs cause severe withdrawal and cannot be gone off of cold turkey. The withdrawal is then interpreted as a “relapse” of the “mental illness” and people usually get more drugs. Just something to think about and maybe investigate on your own.

Report comment

I can’t agree, I know you are trying to distance those who are sad or mentally ill from violence but you are doing so disingenuously.

The fact is which you point out is that those who are diagnosed are less likely to be violent, because they are being treated.

He was mentally ill, it was just that he was not treated.

Now we can go over the most compassionate way to treat, like medications which have their own problems, or talk therapy which is effective but takes long, or involuntary stays at the hospital for long periods of time which can take away the rights of the mentally ill who are not violent.

But that is a different topic, and being dishonest is no way of helping the victims who are sad or mentally ill whether they are violent to themselves such as in self harm, or to others as this guy, or neither, and just need love, companionship, and someone to talk too.

Report comment

jackdaniels,

If you took anything I said to mean that those who are being treated are less violent, then you’re absolutely misunderstanding what I’m saying. I actually see *many* examples of treatment *leading* to violence… because people are acting in self defense in situations where ‘treatment’ is being forced on them… because psych drugs can sometimes *lead* to violence… and because oppression in general leads to the sort of alienation that I think can also potentially feed into despair, anger, and isolation that could be contributing factors.

What do you even mean when you say ‘He was mentally ill?’ How do you know this, and what specifically do you mean? The idea that ‘the mentally ill’ are even a finite, definable group is misguided and part of the problem all on its own. As we’ve seen historically, who is ‘the mentally ill’ is a moving target based on societal norms of the moment, who is in control, who we want to control, and so on.

There’s so much more to say in response to what you’ve offered, but most of it has been said before. I’m just left struck by how you’re even defining ‘mental illness’ and particularly what you think you’re accomplishing for all of us who have been so diagnosed and had ‘treatment’ forced on us for precisely the mentality you’re expressing here… I stand by my point that scapegoating people who’ve been giving psychiatric diagnoses and increasing force and ‘treatment’ against people’s wills will lead to *more* violence and tragedy, not less.

I also really object to your lumping in self-harm to this broader conversation about violence. As someone who still periodically self-harms as a way of coping, I don’t want anyone trying to ‘treat’ or stop me at all, or associating me in any way with people who would go out and murder or hurt others.

Nonetheless, thanks for reading and posting.

Sera

Report comment

Self harm is an act of violence against one’s self, if you can’t see that I am sorry that someone who is responsible for your care has not explained that to you properly.

It is why you distinguish violence of people who are chronically sad, as the ones who do it outwardly are bad and the ones who do it inwardly are excused and good.

The people who are mentally ill are sometimes their own worst enemies because of ignorance, myself included.

I respectfully ask that you ignore the stigma of society in determining your position, you hold a position of power with your articles so please use it responsibly to show compassion.

I agree with you about the pitfalls of the current psychiatric establishment, the over prescribing of medications, the denial of the rights of the mentally ill, but that is no reason to be dishonest and it won’t improve the situation.

Report comment

I find your assertions about self-harm fairly insulting. No one is ‘responsible for my care.’ And even if I decided to go back to the system for support (fat chance of that, but let’s say I did), it *still* wouldn’t be the case that someone else would be in a position to explain meaning to me.

Just about everyone ‘self harms’ in some way… Too much food, too little sleep, too much work, too much exercise, drugs, alcohol, etc… Tattoos and piercings are also often (certainly not always) used as a method of self-harm. Those who hurt themselves in ways that are socially accepted or valued get excused or even rewarded. Those who self harm in ways that scare others or that are less socially acceptable get ostracized or even pegged as ‘sick.’

And yes, there is an issue with people demonizing outward shows of distress and rewarding inward ones. But there are both highly valid and problematic sides to that. The problematic side is this: Pain is pain and disregarding that pain because someone is containing it to their own detriment and then demonizing healthy anger causes problems. However, on the other hand (and this is very important): Stopping someone from harming others represents a PROTECTION OF FREEDOMS AND RIGHTS (of others). Applying (misguided) definitions and preventing self-harm often represents a VIOLATION OF FREEDOMS AND RIGHTS (of the self). That’s a pretty enormous difference.

I would appreciate if, in the future, you would not suggest that others are somehow ‘responsible’ for me and ‘my care.’ It feels very condescending and invalidating.

I do not look at stigma, which often amounts to a painfully misguided campaign to ‘stop ostracizing those mentally ill people so they can get on with accepting their illnesses and getting treatment.’ It completely ignores the harms of treatment and of the disease model itself. Instead of ‘stigma,’ I look at discrimination and oppression.

I stand by what I say in this article and all the past ones I’ve written.

-Sera

Report comment

When I said someone responsible for your care, I meant someone who has compassion and love should explain to you that harming yourself is not healthy. If you don’t like therapists, one of your friends should have told you this, or family?

None of us are perfect, you are right we all engage in self harming activities from time to time, like eating unhealthy, or not exercising, but you are advocating that we embrace this?

I don’t know what you do to self harm, and hope its not cutting or something along those lines, but I do hope someday you are able to empathize with the mentally ill like yourself, and show us compassion.

In the bible it says we must show compassion in order to receive compassion, but that can be used by everyone whether or not they belong to a religion.

It is not my intention to insult you, but I am finished freely expressing myself and would have to agree to disagree with you on why this guy and you share the same mental illness, that leads to violence if not treated.

Thank you for your time in responding, good day.

Report comment

I agree with Sera 100%, and would add that self-harm is not necessarily an act of violence at all. I’ve spoken to many, many people who self harm, especially when I worked at a crisis line, and almost to a person, they explained to me that they were not suicidal or even feeling masochistic, self-harming was simply a way of coping with overwhelming pain. They often called the crisis line because they could remain anonymous, and reported that telling their treatment providers of their actions often resulted in hospitalization, even though they had no intention of doing serious harm to their bodies. I’ve always viewed MOST “mental illness” as a person’s means of coping with a difficult reality. Our judgment of these choices to cope in ways that society at large doesn’t like is actually the source of the “stigma” you are so worried about. The only path away from “stigma” (which I also agree with Sera is really a euphemistic term for oppression and discrimination) is to accept that PEOPLE DO WHAT THEY DO BECAUSE IT MAKES SENSE TO THEM IN SOME WAY. Instead of trying to STOP someone from self-harming, why not try to understand why they feel they benefit from doing so? You will become more enlightened and less stigmatizing in moments! Same for drinking and drug use, suicidal thinking and attempts, intense activity labeled as “manic”, withdrawal labeled as “major depression” – 98% of it is coping with pain and distress caused by circumstances or the society we’re in impacting an individual in a bad way. And the other 2% actually have something wrong with them that an actual doctor can detect and treat FOR REAL once the patient gets away from the psychiatrists trying to explain that it’s all about bad brain chemistry.

It seems that while you reject psychiatry’s solutions, you’re still buying into their framing of reactions to distress as “disorders” that need to be “treated.” I hope these comments help you reconsider that maybe that framing itself is the bigger problem that leads to ineffective and destructive “treatments” in the first place.

—- Steve

Report comment

jackdaniels,

I’m honestly having a really hard time with your responses, and so having to think before I ‘type’ to not come across too harshly.

I genuinely do *not* need anyone else to explain to me what self harm means. When I do ‘self harm,’ it is mostly burning myself, and I’m pretty okay with that. I don’t need anyone’s pity. I don’t need anyone to define what it means for me. And I don’t really feel the need to stop it. Anyone who approaches me with a focus on stopping it loses my interest and trust pretty quickly. If you’re interested any further in my thoughts on this, I suggest you read my blog on the topic which can be found here: http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/11/p-s-sometimes-still-hurt-p-p-s/

Similarly, I have a blog on ‘stigma’ that you may want to check out here: http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/04/false-arguments-part-2-anti-anti-stigma/

And I do not identify as ‘mentally ill,’ and I wonder you feel empowered to identify me in that way, or what it means to you when you say those words?

-Sera

Report comment

I do not look at stigma, which often amounts to a painfully misguided campaign to ‘stop ostracizing those mentally ill people so they can get on with accepting their illnesses and getting treatment.’ It completely ignores the harms of treatment and of the disease model itself. Instead of ‘stigma,’ I look at discrimination and oppression.

Just on this point — this is something that came up with several people off-site. There’s really no need for the term “stigma,” as it’s only used to confuse. Pharma sponsors “anti-stigma” campaigns so people will think it’s hunky-dory to mask and distort their feelings with chemicals. Meanwhile the other emphases of those concerned about “stigma,” i.e. actual discrimination and oppression, can more accurately be referred to as “discrimination” and “oppression.”

As far as one’s self is concerned, “stigma” disappears as soon as you reject the “mental illness” label. What others may think is their problem as long as they don’t impose it on you. (Then it becomes discrimination etc.)

Report comment

I believe the confusion occurs when we hear the term “self-harm.” To harm means to “inflict injury,” so I think it’s understandable how someone can assume this is an act of violence toward self, simply from that phrase. When it is a coping strategy, shouldn’t it be called “self-soothing?”