This has been some year. We (indirectly, sort of) elected the most openly bigoted president of the United States in recent racist history. The media tried to make us believe we were witnessing a new phenomenon by flooding us with news of so many of the latest police killings of Black men (while still mostly omitting all the deaths and disappearances of women and trans* people of color). We’ve teetered precariously on the edge of our apparent destiny as a ‘reality TV’-driven nation, and finally decided to dive full on in.

Yet so much violence mixed with the grandiosity of Trump’s hateful gestures – rather than drawing attention to and raising awareness and concern about all shapes and forms of racism – seems to be making the more everyday variety that much harder to see; As if we needn’t concern ourselves with the comparatively ‘small stuff’ while the big stuff (like a presidential incumbent who’s been formally endorsed by the KKK) is…well… so big. Even though we know that racism is much more about the nearly invisible (to white people, anyway) stuff embedded in our most basic system structures and ways of being, then about those blatant acts that are more ‘symptom’ and ‘outcome’ than ‘disease.’

Unfortunately, this all seems to have distracted us and re-enforced the belief that our own movement(s) should get some sort of ‘pass.’ Because Trump’s policymakers are coming for us, too. Because many of us have been deeply wounded and experienced oppression first hand. And because, well, we’re working hard at tackling that type of systemic oppression. So, shouldn’t that be enough to fill our ‘fights injustice’ quota? Isn’t looking at anything else just a distraction that will water down our abilities to be successful in our own realm?

Truth: Our movement is just as racist (and sexist, and classist, and transphobic, etc.) as any other. We are just as liable to get lost in or be blinded by our privilege (white, male, cis, etc.), in spite of the profound pain and systemic oppression so many of us have survived. The majority of our communities (both on-line and in person) and events are still centered around the voices of white people, even when we’re talking about non-white experiences. And our best efforts thus far to correct for all that have tended toward demands that white people make space for those who are not white at tables where we’re not even sure it’s worth having a seat, or to post ‘Black Lives Matter’ signs in our yards to meet a trend before going about our day.

There are many reasons why this remains so, yet all of it co-exists alongside the fact that Black, latinx, and many other people of color are substantially more likely to be given what are seen as the harshest psychiatric labels, to be subjected to psychiatric force, and to be injured or killed during interactions not just with the police, but also with ‘mental health’ professionals. It also remains so in spite of the fact that our collective voice is weaker, less capable of making change, for all its fractured off pieces, and that it seems the height of hypocrisy to claim the mantle of ‘social justice movement’ if we’re ignoring all these points.

There’s no clear path to digging ourselves out of this mire, but even in the absence of a precise recipe for success, the following ‘don’t’s and ‘do’s seem good food for thought.

DON’T (as in NO! Just stop it! Right now!):

-

Stop comparing psychiatry to slavery (or similar): A common response when this topic rears its head is to debate precisely what constitutes ‘slavery’ (in the most basic sense of the word). In some ways, this can be a complex argument, littered with various dictionary definitions interpreted in somewhat variable ways, and because it is true that race-based slavery and the Atlantic Slave trade is far from the only example of the existence of slavery in our world’s history. However, here’s a bit of a reality check on these points:

When one Googles (yes, that’s a verb now) for images representing slavery (at least from a computer based in the United States), about 98% of the images that pop up on the first page represent enslavement of people of African descent. A word-oriented Google scan also elicits a first page of results that are made up of references to slavery as it has existed most prominently in the USA with a few generic definitions thrown in for good measure. And, when one speaks of ‘slavery’ (without any other qualifiers) to those around them (again, at least in this country), few report hearing someone ask, “What kind of slavery do you mean?”

When one Googles (yes, that’s a verb now) for images representing slavery (at least from a computer based in the United States), about 98% of the images that pop up on the first page represent enslavement of people of African descent. A word-oriented Google scan also elicits a first page of results that are made up of references to slavery as it has existed most prominently in the USA with a few generic definitions thrown in for good measure. And, when one speaks of ‘slavery’ (without any other qualifiers) to those around them (again, at least in this country), few report hearing someone ask, “What kind of slavery do you mean?”

So, when objections are raised in response to the term ‘psychiatric slavery’ for all the appropriation and denigration of the history of so many Black Americans that it represents, it feels completely disingenuous for proponents of this analogy to offer up vague dictionary references or historical citations of slavery in Greece and Rome as first defense. It’s not that any of these points are exactly untrue, per se. Yet, it all rings of feigned ignorance to the reality these words have lived and the impact they are likely to have in the here and now.

Now, to be clear, this ‘don’t’ is directed primarily at white people. Sometimes Black people do make this comparison, and there is a difference. When asked about this topic, Suman Fernando (a Black psychiatrist originally from Sri Lanka currently residing in England and who has done a great deal of work related to racism and psychiatry) had this to say:

“When a black person with a family heritage of slavery (as meaning race-linked slavery) says that psychiatry feels like slavery (I have heard this mainly in the context of being forced -sectioned), that feeling is to be taken seriously as a valid statement with sometimes very deep meaning not just for the person but for anyone trying to understand the effect of the psychiatric system on other people (ie. academics, writers and most of all psychiatrists). If a white person and or someone who has no family heritage of slavery (is not an expert by experience on slavery) says the same thing, it usually means -‘I have experienced psychiatry so I know what slavery is like’ and this is an insult to people whose heritage has slavery experience and a devaluation of the experience of slavery – and indeed an attempt to appropriate someone else’s experience.”

Now, Suman should not be sought out for his expertise on what it’s like to experience psychiatric oppression in general (he has not experienced it), but his words as a Black man who has spent many years examining the relationship between psychiatry and racism should carry great weight. If nothing else, they should carry far more weight than those of Thomas Szasz (who certainly does otherwise have many messages of value to offer) and other white men commonly cited as utilizing the frame of ‘psychiatric slavery,’ but who know very little about living Black in this world.

(Oh, and while we’re at it, also stop comparing the experience of psychiatric oppression to the Jewish Holocaust, the genocide of American Indians, or any other such devastating experience held by another group of people in our nation.)

-

Stop appropriating the words of Black people to support system (or anti-system) messages: We understand it can be tricky to know when quoting a person of color is an effective way of using our own voice as a tool to raise up the voice of another, or when it becomes little more than a way to make one’s self look good or progressively minded. Clearly, white people only referencing other white people is not the way to go. However, how many times has a white person quoted someone, when they could have instead stepped aside to make room for a real, live Black person to speak for themselves? And, based on existing trends of the extraordinarily small pool of Black people recognized as worth quoting (or ‘gentle enough’ to be heard), how many people might unknowingly be walking this earth thinking that Martin Luther King Junior was the only Black person ever to have said anything worth repeating?

On Monday, September 19th, 2016, the opening dinner for the Alternatives Conference was held in San Diego, California. One of the opening speakers was a white presenting man from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, the funders of the conference). Throughout his talk, he increasingly referenced the words of different Black people up to and including Oprah Winfrey (?!). While he inevitably meant well, his frenetic inclusion of every name at the top of the ‘well-known Black people list’ was overwhelming. Toward the end of his speech, he also directly appropriated a quote from Martin Luther King Junior (because, as aforementioned, no speech where race is referenced is complete without at least one MLK nod).

Instead of “…will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character” (from MLK’s 1963 ‘I have a Dream’ speech), he said (basically… we might have a word or two off):

“Judge a person not by the contents of their prescription bottle, but by the content of their character.”

Wait, what?! No. Just no. There’s so much wrong here, from the entrenched association between emotional distress and psychiatric drugs to a white presenting man opening a predominately white conference by appropriating a Black man’s quote and twisting up its meaning to fit a completely different agenda. This should never have happened, but it set (or perpetuated) a tone that was never truly questioned.

This is not unusual. It follows on the heels of one of the organizers for this very same conference having proclaimed, “All Lives Matter!” just the year before. It happens all the time. Our movement, for example, quite regularly speaks of “Creative Maladjustment,” and one relatively recent Mad in America blog went so far as to say:

“In fact, if you wish, and you reflect the values of Martin Luther King, you may say you are leading the organization that he first envisioned, the International Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment (IAACM.)”

Honestly, it’s awful hard to imagine that MLK would have ever envisioned an IAACM that was so white, where Black people and others people of color so commonly feel excluded or spoken for and over, and where a white presenting man would open a majority white conference contorting MLK’s words into something they were never meant to say.

-

Also, stop appropriating imagery from our racist history for other causes: Individuals fighting psychiatric oppression are not the first to appropriate experiences associated with our country’s long record of racism. This is also an issue, as it turns out,

among animal rights activists (see image to the left). In December of 2015, Claire Heuchan (a Black radical feminist and writer from Scotland) authored the article, ‘Veganism has a Serious Race Problem’, in which she made the following statement:

among animal rights activists (see image to the left). In December of 2015, Claire Heuchan (a Black radical feminist and writer from Scotland) authored the article, ‘Veganism has a Serious Race Problem’, in which she made the following statement:

“Material designed to provoke a white audience is also liable to alienate a Black audience. By using slavery as a tool to promote vegan values, vegan activists make clear that vegan spaces are frequently racist spaces. As is often the case in predominantly white spaces where racism goes unchecked, there is little room for people of colour. This marginalisation results in the perception that veganism is a movement by and for white people, which certainly isn’t the case.“

That first sentence seems especially worth repeating: “Material designed to provoke a white audience is also liable to alienate a Black audience.” We would do well to learn from and apply this in our own work.

-

And, stop arguing with Black and other people of color when they tell you to stop: It really should be unnecessary to write more than just, ‘Don’t’ in this section. Yet, judging by the frequency with which this occurs, it seems much more is needed. There is a phenomenon called ‘whitesplaining’ that occurs fairly commonly, and one of the ways in which it rears its ugly head is when white people attempt to explain to Black people or other people of color why they shouldn’t find something offensive.

However, in a society that has consistently catered to white feelings, perceptions and interpretations, if we are truly going to move forward toward healing racism, then the very least that a white person can do is listen when a Black person tells them that something they are doing or saying feels racist or brings up hurts that are so related.

However, in a society that has consistently catered to white feelings, perceptions and interpretations, if we are truly going to move forward toward healing racism, then the very least that a white person can do is listen when a Black person tells them that something they are doing or saying feels racist or brings up hurts that are so related.

And beware the urge to go in search of another non-white person to contradict the first (generally done in effort to somehow vindicate one’s self). Certainly, there are many times when people of color will disagree on such points. There are many groups, after all, that fit within the term ‘people of color,’ and even if you narrow it down to just one – Black, for example – there is no obligation to be any less varied or diverse than any other group in what individuals within those groups think, feel or say. However, our time would be far better spent examining our own motives and why it feels so important to hang on to something if we’ve been told so clearly that it’s hurting a fellow human being, especially when that fellow human comes from a group that has already lived a lifetime of being silenced and devalued.

Better that one just… stops.

-

Stop proposing ‘color blindness’ as a goal:

“I don’t see color.”

“I wish we were all colorblind.”

“Race is a social construct.”

When we say those things, it often seems that the intent is to say that people are people.

That we aspire to see people as the whole of their selves instead of as some label they have been given. In this psychiatric survivor movement, where we are so intentionally trying to move past preconceived notions that stick to people’s being, it even seems understandable.

That we aspire to see people as the whole of their selves instead of as some label they have been given. In this psychiatric survivor movement, where we are so intentionally trying to move past preconceived notions that stick to people’s being, it even seems understandable.

It is a flawed concept though. This movement is very white. Deep breath. It’s been said. The list of reasons is long, but at least part of that is that inviting people of color to an all white table is complicated. Nobody wants to be tokenized or treated as some sort of exotic foreigner. So, perhaps, well meaning people offer the color blind explanation to try and offer some comfort. Intentions being what they are, it can be seen as a welcoming gesture.

However, the first flaw is the implication that blackness or brownness is something to be ignored. And, the second flaw is the inherent privilege of that statement. If you are a white person, you can be color blind. Racism is like the next city over. Sure, it impacts you… from a distance. But to see it, requires leaving your comfort zone and intentionally seeking it out. If you are a person of color, it’s more like your neighborhood. You have to work hard to even have a small space where the impact doesn’t exist. The society we live in means that every retail experience, every police stop, job interview, all of it has the opportunity to remind you that the world sees you as a lesser person. You cannot be color blind because there is no space for that.

It’s okay to want to not see how unfair things are. To wish them righteous. It just doesn’t do anything.

Yet, promoting ‘color blindness’ seems to be a phenomenon that is sweeping our movements most closely associated with ‘mental health’.

While we all instinctively want to be able to stand on the merit of our individual personhood, Black folks have rarely (if ever) been able to focus on the individual self, to be seen as possessing of individual identities rather than simply as one of a mostly faceless mass. It is born of privilege that white people are able to be individuals at all times, to not focus on race, and to (supposedly) not see the color of other individuals.

What evidence is there that Black people and other people of color are not allowed to be individuals? We need only look at the way laws are enforced across entire communities of color. Police forces occupy such neighborhoods daily. Recently, you have seen these occupying forces in Ferguson, Baton Rouge, and Standing Rock; Police officers dressed as if they are going into military battle with American citizens.

What evidence is there that Black people and other people of color are not allowed to be individuals? We need only look at the way laws are enforced across entire communities of color. Police forces occupy such neighborhoods daily. Recently, you have seen these occupying forces in Ferguson, Baton Rouge, and Standing Rock; Police officers dressed as if they are going into military battle with American citizens.

When was the last time you have seen occupying forces such as this in white communities? How has their response compared in university towns that riot after winning tournaments, or cities that riot after winning professional championships? Whenever there is a random shooting in Chicago the media portrays the entire community as a criminal element. When 9/11 occurred every Muslim in this nation feared for their lives and many still do today.

Yet, just recently a white man murdered two police officers, and not once was his race mentioned. Not once was his community or family held accountable for his actions. As a matter of fact, the term “Lone Wolf” was created to effectively give white men a way to be individually identified in domestic terrorist acts, acts of racial violence, and any other criminal activity in which they may be involved. This is the color blindness that white people are able to practice so unabashedly while still participating in racial profiling, oppression, and systemic racism.

The intergenerational trauma we face as a nation together and then in our respective communities has shaped the way we view and interact with each other. The shame, fear, hate, and refusal to ‘see color’ has played a significant part in transforming this nation into one of traumatized individuals who have refused to deal with the elephant in the room.

The last eight years, we have witnessed what many thought was a past that was long forgotten, but in reality was only swept under the carpet. Many white people respond to the hatred of Trump supporters and those who blame Muslims for any incident that might be related to terrorism in feigned disbelief. They are seeing now what many Black people and other people of color have known for years. Racism has always been alive, practiced, and tolerated in this country.

(As a side note, it seems worth adding: When people of color laud ‘color blindness’ or throw out a ‘All Lives Matter’ cry to groups of mostly white people… Well, whatever they may mean in those instances and however differently intended it may be from when it leaves the lips of a white person, it’s probably worth considering what the white people hear… Do they care what is actually meant, or does it simply get translated into an excuse to do the same, and serve to undo so much work of others who have fought to broaden their view and understanding?)

DO (as in YES! Please. Give it a go! Trust us!):

-

If you see (or hear) something, say something: Here’s a line most commonly associated with abandoned backpacks or suspicious activity in public places, but what’s much more common is witnessing people making comments that perpetuate hate, negative stereotypes, prejudice, and/or plain lack of respect of one marginalized group or another. And, more often than not, such statements go unchallenged.

Why? This happens for a variety of reasons including that the person in the ‘witness’ role:

- Doesn’t want to be seen as rude or risk damaging a relationship

- Is afraid they’ll somehow be a part of silencing a person of color or unintentionally treat them as incapable if they speak up in their defense

- Is afraid of getting labeled as the ‘fun police’ or being excluded from a group of friends or colleagues for being ‘too sensitive’ or ‘too difficult’

- Is in a position of lesser power and is afraid of the consequences of questioning or potentially embarrassing a person they see as ‘above’ them in some regard

- Feels less educated and/or confident in their communication skills than the person they want to challenge

- Isn’t entirely certain that what they heard is truly ‘wrong’ and isn’t quite sure why it leaves them feeling uneasy

- Isn’t sure what to say to challenge or interrupt what was said

- Is waiting (hoping) for someone else to step in

- Feels like it’s pointless to speak up, because they have no hope of changing that person’s mind

Within the movement(s) that seeks to address psychiatric oppression, silence can also sometimes be the result of just how difficult it can be to tell someone who has been so oppressed in their own way that they’re nonetheless hurting someone else, or taking advantage of their privilege. Indeed, it can be very hard for someone who’s spent years in a psychiatric institution or who has been living in poverty to hear or acknowledge that they have any privilege at all.

But, getting comfortable with saying something (even if clumsy and imperfect) is absolutely key. Even if it feels like there’s no chance of changing the other person’s beliefs (because what you say may impact others who are listening, and seeing your example may give someone else the courage to also speak up and interrupt in the future, and because being silent in the face of oppression is rarely the right thing to do). In fact, given that it’s white people that have historically held the power and been responsible (however unwittingly) for maintaining institutional racism, it makes all the sense in the world that they should also be primarily responsible for its undoing.

Along the way, expect to make mistakes. And, when a Black person or other person of color ‘checks’ you or otherwise gives you feedback… Well, in most instances, you’ll want to refer to #4 in the section above, thank them for letting you know and move on.

-

Work together to develop our own language: As a movement, we have continuously recycled language from other groups. Calling the fight against psychiatric oppression a ‘civil rights movement’ is one example that walks the line. (Why not just call it a human rights movement?) And, as noted in the previous section, a particularly painful example is using terminology from the slavery era (aka ‘psychiatric slavery’) to describe psychiatric units, forced treatment, and the mental health system at large.

Many Black people have stepped up and asked that this language not be used in relation to modern day mental health, only to be met with white (as well as a handful of Black) folks who have loudly proclaimed that they have a right to compare slavery to the modern day system. However, what seems to be lost in this conversation (aside from a heavy dose, once again, of #4 from the ‘Don’t’s section above) is the generational trauma associated with this history. So many seem to be oblivious to the fact that many Black people are literally being re-traumatized by the very people who claim to be fighting for their rights.

There simply is no reason in today’s world that we can’t find alternative language that is both more accessible and less harmful.

Language has great power. It can create connection or build mistrust. Proclaiming who you’re fighting for is meaningless if you trample those people’s feelings and wants along the way. It is not the job of people of color to offer new language. It is up to the movement as a whole – and particularly those who say that they care – to see, hear and feel how they are impacting others.

We can and should do better.

-

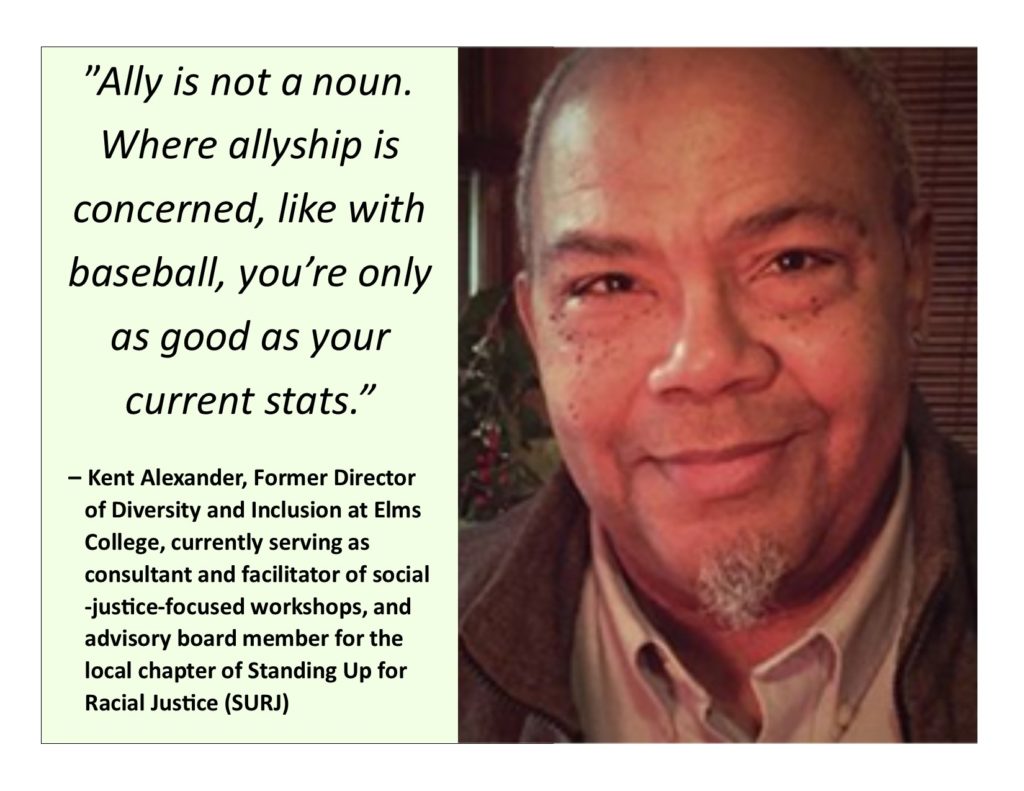

Work from a social justice framework, NEVER an industrial one: This ‘movement’ has been fragmented, and far too many people are now focusing on ‘peer support.’ More importantly, they’re focusing on peer support not for its purest vision or value, but for its career path and industrialized potential. ‘Peer’ itself is now most commonly boiled down (in this context) to two people with similar diagnoses (or to one person who has been diagnosed), rather than the commonalities between two people who have experienced similar dehumanization or systemic oppression (often of more than one kind), in addition to any personal struggles that may have led them there.

But few people seem to recognize how our power is slipping further and further with every ‘peer’ job that is created, especially for all the compromises we seem willing to make to reach that end. And, when we are so quick to lose our way in the battle that we say we are prioritizing, how can we ever expect to get right with all its intersections with so many other kinds of oppression (or how we are playing our part in keeping them alive)? It may all be well intended and start under the guise of creating change, but in the end, rendering those who would put up the most heartfelt fight dependent upon those they seek to change for their financial survival is often the most effective way to shut them up.

But few people seem to recognize how our power is slipping further and further with every ‘peer’ job that is created, especially for all the compromises we seem willing to make to reach that end. And, when we are so quick to lose our way in the battle that we say we are prioritizing, how can we ever expect to get right with all its intersections with so many other kinds of oppression (or how we are playing our part in keeping them alive)? It may all be well intended and start under the guise of creating change, but in the end, rendering those who would put up the most heartfelt fight dependent upon those they seek to change for their financial survival is often the most effective way to shut them up.

To fight one battle, we must see them all for what they are, and call them out as such.

-

Focus more on the comfort of those who’ve experienced oppression than those in the dominant group: Our movement (like so many others) has often made the mistake of believing that we are obliged to afford boundless room to be sensitive to people’s needs to learn and how hard it is to unravel those invisible messages we’ve been taught. But – in our effort to be understanding – it seems we often only manage to perpetuate the creation of spaces that continue to be inaccessible to those who have been most harmed.

So much that’s embedded in our culture we have absorbed without ever thinking it through. Take words for example: Who knew that terms like ‘cotton pickin’ hands,’ ‘sold down the river,’ ‘getting gyped,’ and ‘no can do’ all find their origins in such a racist history? Of course, if most of us paused for a second to think about some of those phrases, their problematic nature would become obvious, but the reality is that so much has sunk into our minds and ways of being without us realizing (or living lives that require us to realize) its there. And, so, far too much of the time, we simply don’t have an awareness that there’s anything to even think about.

It’s true, we can’t suddenly know what we don’t know, yet we need to move away from the idea that mistakes are ‘okay’ (while retaining some of that compassion for the process). Instead, we need to re-frame the conversation around the idea that our mistakes, missteps, microaggressions, and needs to learn (and unlearn) make sense, but that they are categorically, completely not okay. Otherwise, we will never hold each other (or ourselves) strongly enough to the necessity of change.

Yet well intended people are pulling ideas out of their trendy ‘non-violent communication’ tool bags, and proposing warm and fuzzy phrases like, let’s learn to “call in” instead of “calling out.” And, sure, (as Loretta Ross, among others, has spoken to) there is a time for calling ‘in’ to people with curiosity, an invitation to learn, and a desire to understand and be understood, rather than calling them ‘out’ in a way that might make them feel shameful and judged. (Or to call ‘out’ the actions while somehow still calling ‘in’ the people.)

But, at some point we need to stop and ask ourselves on whose needs and culture is that approach based? Is this not sometimes twisted into just another way to ensure that white people’s comfort and feelings continue to reign supreme (in keeping with a ‘white fragility’ frame)? Who’s potentially being silenced along the way?

The reality is that white people have the privilege of whiteness to increase their comfort in so many (read: almost all) venues. So, perhaps it’s just fine if our approaches to discussions around racism are a tad less… precious, and that we might make ample room for anger, and yes, a healthy dose of calling ‘out’.

-

Pay attention to internalized racism: Here comes some more fun. Why is internalized oppression important when we talk about racism in the psych survivor movement? Isn’t the whole point to give people of color a voice? Well, absolutely, Mr. Literary Device, but (and this is said with full knowledge of the inherent dismissive implication) when a system is built on teaching people how fundamentally ‘less than’ they are, that voice may need a history lesson.

A vignette from Earl: “So, this one spring day, I found myself in this workshop on diversity and inclusion. I find myself in these sorts of spaces fairly regularly, and it was pretty standard stuff aside from a single double sided page called ‘Possible Things To Consider When Working With African Americans (IMHO)‘. It was pretty appalling.

Included were things like ‘If you do not have any friends of the same background, culture and race as the person you are working with it’s best to assume you are not culturally competent.’ That isn’t super off on its own, but the part that caught me was the reverse implication: That having a black friend could possibly make you competent to an entire, huge, wide ranging culture. (Note that this is perfectly in sync with one of the most commonly used, eye-roll inducing defenses around when a white person is accused of being racist: ‘Hey, I’m not a racist because I’ve got a black friend!’)

It went on to say that ‘The darker the skin color and the less European the person looks, the more likely it is that we have dealt with racism and discrimination.’ This essentially serves to establish a color chart of oppression, and, most absurdly, suggests that perhaps some of us who are lighter skinned have somehow evaded being impacted by what we know to be a deeply systemic issue. Most upsetting for me, was point number five suggesting that language such as ‘recovery, mental health and wellness’ are ‘too white, fancy or educated and not of our culture’.

I imagine, most people can see where I might have felt upset. I followed up by reaching out to folks from the almost entirely white led organization who put this out. Initially, they just put me off, and when they did address the point, there were really only two responses. One, said in private, was that I was too Christian and educated. (I’m an atheist with a GED, but that is just another example of people making assumptions.) The other response, the one said directly to me, was that this was a group of black people and thusly to question the paper was to implicitly question their experience.

That wasn’t my hope. I wanted, however, to talk to them. To ask why they felt like these words were inaccessible. To ask why they would write a paper to white people that reinforced the narrative that black people are less intelligent and less resilient. I never got to have that meeting but those questions persist.

I remember being in hospitals and knowing without anyone needing to tell me that if I got angry, I would be restrained. There would be no question of why, or an assessment of my danger levels, because I was assumed to be inherently dangerous. I couldn’t ball my fists when I was angry, or make intense eye contact. I couldn’t be alone, and I couldn’t be more than a role that had been predetermined.

I’m a black man, which means I am a time bomb. You want my opinion, when we agree. You want me at the table, when it isn’t your table. You want my intensity in doses you can measure out and my body when it’s useful. I had a teacher call me a gang member in the administrative building we called a school in Connecticut, despite the fact that I had only made one friend in my 6 month stay and when I gave that little blonde girl a hug after my mom moved away, I wasn’t allowed within ten feet of her again.

I say that stuff mostly to say that my history within the psychiatric system is really informed by the ways in which young men of color are told this narrative of themselves. For a long time, I wasn’t someone who had heard these things. I was these things. Florynce Kennedy once said, ‘When a system of oppression has become institutionalized it is unnecessary for individuals to be oppressive.’ I wasn’t smart enough, or well-read enough, or on a more base level, worthy enough of not being a fearsome entity in a story other people had written for me.”

This movement, in large part understands that when we talk to people who have been given a psychiatric diagnosis that those words may have become a central pillar of that person’s existence. That to ask them to re-define themselves without the tools they need to build another, different pillar isn’t fair. That it would be a disservice. The same thought makes sense when talking about anybody who has been fighting the weight of oppression. The solution isn’t any more complicated than to be compassionate and curious about where people derive the definitions of who they are; to try to understand why and how they’ve come to believe what they believe. Assuming you know something about another person comes with a cost.

That is to say, if we assume that just because a person is Black that they have ever necessarily had space and time to ponder their position in a racist society is to assume we know intimate details of their life with no rhyme or reason.

Conclusion:

Our communal trauma has only been exacerbated since the Civil Rights movement. While so many white people had the luxury of assuming that the Voting Rights Act, the Housing Act, and desegregation put an end to racism, Black, latinx, and other people of color have been painfully aware of how its all only grown more covert and expanded into many other forms such as redlining to suppress voting, housing, and educational opportunities.

When you recognize and face hurdles day in and day out, no matter how hard you strive to achieve academically, professionally, and in social settings… When you walk to the corner store and pass five or more police officers, or are stopped walking the two blocks to the corner store only to be asked where you are going, or to show your identification… Then you begin to realize that your community is being targeted and treated differently than other communities.

And yet our own movement(s) trucks on, with its largely white-driven leadership, conferences, and forums such as this one. With people periodically expressing outrage when racism is brought to the forefront, as if little of note is otherwise happening most of the time beyond the Murphy Bill and so much else that is directly related to our own little corner of the world.

And, so this blog returns to where it started:

The idea that we are truly standing in opposition to systemic oppression becomes a bit of a joke if we have to add a tag that says, ‘Oh, but we only really mean that for this group.’ And, failing to make ourselves accessible (and relevant!) to so many people ensures that our voice will never gain the numbers we need or get loud enough to have any shot at competing with any of the forces currently standing in our way.

Shortly after Trump was named incumbent, Black Lives Matter released a powerful statement that concluded with the following sentence: “The work will be harder, but the work is the same.” For our own movement(s), there is also much truth in those words.

But, for us, the work had also better be different. We had better fight to include far more voices than ever before. We had better look to get much more honest about our failings and who’s been left out. Ignoring these realities is a path to nowhere.

A racist movement cannot move.

NOTE: We realize that there are some concepts, references, and language that may be less than completely familiar to at least some people reading this blog. As such, as have done our best to insert links (wherever you see blue text) as an additional resource for anyone interested in learning more.

Divide and Conquer

Never in human history has there been a more effective way for tyrants to rule over large groups of people who, should they ever learn to cooperate, would easily throw off such tyranny.

The ruling class, the elites, what ever you want to call them, have been stirring up racism for the last few years for reason. If you look at Google images for “Eric Garner Protests” EVERYBODY was sick of the police state. What do you do when you are running a police state and the people are starting to rebel ? Divide and Conquer ! Make them hate on each other, keep the busy with that and you stay in control.

Report comment

The_cat,

I guess the question is at whose feet should it most rest to make concessions for the sake of cooperation? The unspoken expectation in answer to that question – at least in this context – is most typically that people of color must be the ones to let some of this go.

This blog, on the other hand, would suggest the reverse… Which feels most consistent with overall social justice principles in my eyes. Shouldn’t we almost always look to the group who has been most marginalized within the context of which we speak to teach us and tell us what is being asked? And shouldn’t we do our best to listen, even in advance of fully understanding?

Sera

Report comment

All I know is I was enjoying watching the police state, the prison industrial complex, the tyrants, what ever you want to call them, getting their butts kicked until they opened up a can of divide and conquer.

Racism was dying if not dead, a whole generation of whites and their favorite music artists and sports players are mostly black, you just don’t or didn’t have a racism problem in the hip hop generation or “millennials”, it was over and they brought it back for divide and conquer.

But yes “we” should listen to “them”.

Also when ever I get stuck filling out a form and it has check boxes for ethnicity I leave it blank or write NOYB (none of your business), screw check the box to get put in one. I am human, that they should be able to figure out. Social engineers, sick of them.

Report comment

The_cat,

You left this comment on Noel’s post, too. I responded there, but will offer something similar here.

The suggestion that racism was ‘dying if not dead,’ seems strange and incredibly untrue to me. What you are speaking of is cultural appropriation… the ability to take what we like, without having had to live through any the terribleness that was a part of birthing the art.

I do not know you, and do not know anything about the color of your skin or your ethnicity. But, when I read what you write – particularly at the end there – I just want to refer you back up to the ‘color blind’ piece in the blog.

Report comment

Muslim is not a race it is a religion. And when did liberty and justice for all turn into birds of different feathers MUST flock together ?

This whole diversity thing is a sham anyway, the goal is not diversity, it never was, the goal is to mix everyone up till its gone and have a whole nation of tax and debt slave automatons.

Where are all the nativity scenes and Menorahs this holiday season ?? Those “offensive” things. The USSR was the first state to have, as an ideological objective, the elimination of religion and its replacement with universal atheism.

They want “diversity”, give me a break, I see right through it.

Report comment

This ‘dialogue’ strikes me as pointless, so I’m going to bow out of it here. If I’m honest, I’m not even sure I follow some of your commentary. It seems very unfortunate that you’ve gotten to such a place where you seem to think that acknowledging, seeing, respecting and valuing people’s different ways of being in this world is a ‘sham’, though.

Report comment

Divide and conquer has been around since the beginning of time. The difference here is that whenever divide and conquer is used as a tactic in he Black community our allies are able to go back to their way of lie and possibly become our next oppressor. During slavery this tactic was used successfully for one main reason Black folks can never (even if we wanted to) assimilate into white culture our skin color simply won’t allow it. The Irish indentured slaves were able to do that sand therefore effectively became another group that became oppressors. So, yes we are weary because we know and remember history. When a group of folks are offered power it’s rarely turned away.

Report comment

Hi All,

I’m going to disagree with some points of this well-intended article, which at some times unfortunately come across as thought-policing:

Firstly, any person of any race can be enslaved; African-Americans do not have a monopoly on this most unfortunate experience throughout human history. Today in small parts of Asia and the Middle East, non-black people are still enslaved. Historically, many, many peoples of different ethnic backgrounds have been enslaved – from smaller Hispanic tribes conquered by the Azctec and Incas, to European peoples forced into labor or battle by the Romans, to a variety of East and South-East Asian groups throughout history. Let’s get a broader perspective – simply because the majority of historical slavery in America has been of black people – a very unfortunate fact – does not mean that we cannot discuss the experience of slavery in relation to psychiatry (psychiatric slavery extending far beyond America) without being insensitive (which is a matter of opinion, anyway).

Furthermore, there are significant parallels between being deceived about the nature of one’s distress and put on drugs for life (rendering one unable to work and love), and being enslaved in more overt and visible ways. In this country, we fortunately have free speech, so I am free to continue to point this link out. You all are also free to interpret the term “psychiatric slavery” in a discriminatory way, but your analysis here obviously didn’t convince me of the rightness of your point.

Lastly, no matter what we say, we’re going to upset some people. I don’t worry constantly about who will be upset by everything I say. I believe our culture has swung way too far in the direction of being careful about saying every little thing, to the point that we now have “protection zones” where upsetting things can’t be said on college campuses. This is a country of free speech; let’s remember that.

Also, the higher diagnosis rates of non-illnesses among black and Latin people is likely primarily due to social factors more frequent in those groups, especially poverty and lack of economic opportunity. Their getting these labels is not caused directly by their skin color in a simplistic cause-effect way. Although bias by white people “over-diagnosing” (if one can overdiagnose an invalid psychiatric non-illness) is also likely involved.

Re: The part arguing, “Stop arguing with Black and other people of color when they tell you to stop.”

Sarah and Iden, human psychology being what it is, you must know that ordering people to do some general thing in relation to a certain race is unlikely to work. No one likes being told what to do. And postulating a general rule about what white people should do in relation to black people is unrealistic and simplistic. Sometimes white people’s positions are going to be right (or right to a degree), and sometimes they’re going to be wrong (or wrong to a degree). And vice versa. Generalized rules for how to interact in unique, quickly-evolving interpersonal situations are unlikely to be useful in my opinion. I’m sure it feels good to you to write this in a moralistic way; it will probably just do nothing to effect those who read it..

Notice, I don’t say that people shouldn’t find things offensive. White, black, yellow, brown people can react to me however they want, as long as it’s physically non-violent. For example, people online have even recently been telling me I should kill myself, that I was misdiagnosed and never had a severe mental illness, that I’m still crazy and delusional, and stuff like that. It doesn’t bother me because I am immune to that bullshit. Although of course I don’t appreciate those sentiments, dumb people (my opinion) also have a right to say them.

But I also have a right to say what I want, and the authors of this article cannot tell me what I should do in conversations with people of other races. That is what free speech is about.

A bit about my current background – I interact with black and Latin people all the time in my meetups, and for the most part these issues never come up. I just treat people as people, trying to engage with them in a positive way regardless of their skin color. Then again, I don’t move in the circles anymore of the “mental health” system and its oppressions. I left that in the dust long ago. And to be honest, I escaped what I will call psychiatric slavery largely because I had enough money, and because I knew that psychiatric diagnoses were frauds and that there was a better way.

I imagine you may try to claim that my comments vindicate your criticisms of what white people do, but if you claim that; you will simply be ignoring the validity of my concerns in the same way you accuse others of denying the importance of many of your key points.

So, I will continue to use the analogy of psychiatric slavery; this article makes no impact on me in that regard. And I will continue to help extremely distressed people in the ways I do, which many of them report finding very helpful/hopeful… there is no one size fits all for how to advocate and relate.

Report comment

Matt,

You seem very invested in your perspective, even though it is hurtful and dismissive toward many people of color. I wonder why you feel your opinions on this matter – as a white presenting person – are equal to those who have lived black or brown in this world? I’m not speaking from a legal perspective… I’m speaking from a social justice, and a just ‘what’s right and decent’ one.

Your thoughts?

Sera

Report comment

Sera,

I have no reason to think my opinions are less or more equal or valuable than opinions of people of any other race.

I try to treat everyone of every race fairly, but I don’t accept being made to feel guilty for what my ancestors did, or the idea that I or other whites need to “atone” or give special accommodation to another group. Having said that whites of course should not discriminate.

There’s a problem when you come out with an article and try to tell people four things they need to do in relation to another race. It’s not gonna work, since people don’t like being prescribed what to do. It comes across as moralizing and paternalistic. Again it might feel good, but it’s unlikely to change minds and hearts.

I’ll be very open and honest about my background, since I believe in the healing potential of that. I come from a family of privileged white people with one of our members being overtly racist toward blacks and Hispanics. But I resisted that, and although I still occasionally hear their voice in my mind telling me unspeakable things about people of other races, I respond to it by trying to be open-minded toward people of all races and not judge them. I think I largely succeed in this.

It’s hard but I think we should take a look at the racial reasons why 47% of the country voted for Trump – in my view it is partly because they are threatened by ethnic-demographic change away from the white majority. But IMO a moralizing, prescriptive, guilt-inducing approach to white people in terms of telling them how they should relate to black people will not work. It will just create more resistance in whites to openness to other races. The Puritanical-prescriptive-guilt-laden approach was probably a large part of why uneducated whites participated in the numbers needed to get Trump through the electoral college.

Report comment

Interesting comment. It wasn’t until recently that I discovered that the white Confederate enlisted troops were, in a sense, being enslaved themselves, because they were fighting for a cause that was out to make them useless. In the mid 19th century, slavery was becoming industrialized and the owners wanted to go national (remember the fighting over slavery in Kansas?). Were the South successful in the Civil War, the lower ranks were going to be permanently idled, replaced by slaves throughout the nation. Since that realization, I find myself thinking of the Confederate flag as the Chump flag; I’ll have to be a lot better at tai chi (too old for hard martial arts) before having a conversation about race with a guy with a Chump flag decal on his truck.

Report comment

Matt, have you ever wondered why these issues never come up at your meet ups? “A bit about my current background – I interact with black and Latin people all the time in my meet ups, and for the most part these issues never come up.”

Report comment

Hi Iden, thanks for your restrained, curious comment.

I am living in a pretty wealthy zip code (outside of Washington DC) but it’s also one full of a broad mix of ethnic backgrounds. I think the people at my meetup social events are largely college-educated (often with masters degrees or more), relatively economically secure, well-read and informed people. And they are people who have been to colleges (and now work situations) where they see a big mix and range of ethnicities and backgrounds. So I think they get to interact with a range of races and backgrounds and that this interpenetration helps them to be open to and not judge people of diverse backgrounds.

I notice when I go to meetups that I still have judgments about people of other races – for example, when I met a young black man at a recent meetup at a restaurant, I spontaneously had the idea in my mind that he was probably relatively uneducated, which turned out to be wrong (while it was probably true of a few of the white people there). As I shared in the comment from Sera, I had a racist influence within my family that contributes to me having these biases or assumptions. But there’s a difference between having a bias/assumption and what you do with it. And, I think that getting exposure to people of other races (sorry, that sounds kind of bad) in a variety of situations really helps to break down barriers and lessen racism. We have that here in Northern Virginia. But I think in a lot of other cities, racial segregation remains to a greater degree, and so racist assumptions (and actions) have less chance to be broken down. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on this.

Report comment

As a former resident of the DC area, it’s interesting to me that you think of northern Virginia as a fairly unsegregated area. I just checked on the demographics and the region is only 11% black, as opposed to the almost entirely black (and extremely poverty-stricken) areas just across the river in southeast DC.

I also wonder if you’ve considered that people of color simply aren’t bringing concerns about racism to you? From the sounds of it you’ve already solidly made up your mind on this issue, and I know that personally I’m more likely to approach people about sensitive subjects if I know they have an open mind.

Report comment

twistthespine:

Thanks so much for coming in and commenting. I appreciate the way you are thoughtfully making your points and asking questions, and so much more briefly than I tend to. 😉

-Sera

Report comment

Twist, you are right; southeast DC is still like a ghetto, full of drugs, crime, and poverty, and it is a terrible thing. I have been there a few times; just walking down the street as a white person one feels afraid.

You are probably right they aren’t bringing their concerns to me; I may not have the life experience to understand their concerns.

Then again, these meetups that I do are not about race. They are social groups for people in their 20s and 30s, of any and all races, to make new friends and have fun. And we do have fun.

In NOVA – a huge metro area – there’s a big range of backgrounds, at least in the areas I am in. It may be only 11% black, but that represents hundreds of thousands of black people. It’s also a very large proportion of people from Hispanic backgrounds and different Asian backgrounds.

Report comment

Hi, Matt. I actually lived in the town Occoquan for about 2 1/2 years in the early 90’s. As you can imagine I was one a few Black faces in town. I also lived in the Appalachian Mountains for about 5 years in the mid 90’s. I was the only Black person in my town of Crossnore, NC. It does help to be exposed to different cultures, ethnicities etc. in order for bias, prejudices and racism to be broken down.

I am a resident of SE/Ward 8/Anacostia/East of The River in DC which I fast becoming another area for gentrification but mostly Black for now. I find myself still in man instances one of the only in many groups I mingle with. And I find if I feel even the least bit unsafe or uncomfortable I will not discuss many topics that deal with any of the isms, oppression etc.

I have heard that from many of my friends and associates as well. People talk about creating safe space a lot in DC in reality, there aren’t many, especially online. And sometimes I step out on faith and speak the truth.

College degrees may help folks feel less of the need to talk in public about race, I assure the conversations are being had in private in safer space with folks that look like them. here codes, unspoken codes in all communities. And Black folks just like any of group of folks have learned to look at body language and speech to know we are safe around. I don’t know you and I’m sure that folks just meeting you at a meetup up are not going to open up to you about racism without getting a good feel for you. I’m happy to see you have some insight into your personal history and will continue to grow in that.

Report comment

Iden, good to see another MIA writer is only about 30 minutes away from me (I’m in Vienna/Fairfax area, west of the river). Maybe we will get to meet one day at one of these conferences.

Thanks for your comment. There is a lot of segregation in DC (and parts of NOVA too, for sure) by income. I don’t like to see that.

And if you ever want to come to one of our meetups email me and I’ll be happy to share info – I’m at bpdtransformation (at) gmail (dot) com

You might be interested to know the folks in my meetup groups have largely no knowledge about my being a psychiatric survivor, writing on MIA and other forums, etc. The Meetups just aren’t about that. And I think they would be surprised if they found out. Probably a few of them will, eventually. But I have nothing to be ashamed about…

Report comment

Matt, I’m too shy to try those meetups 🙂 Maybe one day.

I will email you anyway so that we can have each others contact info.

Report comment

Ok please do email me: mstevenson2010 (at) outlook (dot) com

I was very scared when I went to my first meetup. It gets better.

I’m sure if you speak out about social justice like you do, that you can do it 🙂

Report comment

Matt, DC has also become a city divided not only by race but by income and education. Which gives folks less of a chance to break down those stereotypes. As they like to call these urban areas the coastal elites. They forget the new carpet baggers are coming from the red states and bringing all of the preconceived notions of all POC with them. Which is not a good thing.

Report comment

@Matt Stevenson: Good comment. Lots of didactic, ‘SJW’ ‘thought policing’ on MIA of late, which disappoints on a few levels. These days I mostly look at MIA for ‘On The Web’ curation of articles from elsewhere. Staff and visiting authors appear to be mostly coming from the same ideological perspective and largely the same demographic, which isn’t healthy or interesting. As a ‘non-survivor’ parent of a young, non-drugged child there already isn’t too much for me here, but now it’s really losing me as a reader. Best to you, Liz Sydney

Report comment

I personally think everyone’s opinion should be allowed on MIA, and as people who are shut down, be especially willing to listen, and hear people out. As a community we do all have fighting psychiatric oppression. If people ant to bring up racism, or other forms of discrimination, just think it should be done in a more open way.

That being said, I don’t think many SJW points of view are all that sensitive, or compassionate. I know we reguallry get branded as being of privlage for not subscribing to psychiatry’s perspective, or even called Scientologis, just for asking for people to concidder psychiatries harm, or lack of validity.

However, I do hope that soon we will be able to come together, before it’s too late, and slip further affecting generations to come.

Report comment

I’d be interested to hear more from you about how “sjw” viewpoints strike you as lacking in compassion or sensitivity. I personally feel as if I’ve come to my viewpoints (which pretty closely match this blog post) through having a great deal of compassion for those facing the harshest challenges in our society.

Report comment

People who identify as SJW, generally seem more concerned with avoiding certain words, and only listening to certain members of a group that fit their agenda. for example the people who identify with APAs definition of mental illness , or black people who agree with them, while not listening to black people who feel let down, or people in the mental health system who feel let down. They also seem to lash out at those who disagree, and aren’t sympathetic.

Report comment

I don’t agree with that we all have the same viewpoints. I’m sure MIA would love to hear from other voices, especially those of parents such as yourself.

Report comment

@Iden Campbell McCollum, Must disagree here. MIA is very weak on parent voices. It prefers professionals who paternalistically talk ABOUT and TO parents. MIA also prefers parents who needlessly drugged their children for minor issues and regret it, although the information has been available for a long time to have avoided such experiences in the first place. I’ve been dealing with a serious issue for a decade and avoided diagnosis and drugs (simply because I did the reading), but for MIA I’m neither fish nor fowl even though my experience represents something important for other parents. (Incidentally, I submitted a ‘Personal’ piece that they evidently liked and accepted but bounced from one editor/category to another til they dropped it with no word. That’s OK, but signifies that, no, they don’t necessarily love hearing from ‘outside’ voices, or are just confused by them.) Best to you, Liz Sydney

Report comment

Maybe you could use your experience here to spread the word to other non survivors, and parents of non-drugged young children, that there IS oppression and injustice happening to a lot of people. Turning away is what everyone but the philistine did and what most white people still do.

Report comment

Thank you, Iden, Sera & Earl for this much-needed piece. In particular, I’m relieved that you told people to stop using the term “psychiatric slavery” – I’ve had an on-going argument for years with a white movement activist who insists on using this term, and I hope this person will listen now. I also appreciate your calling out the white SAMHSA administrator whose distortion of black leaders’ words at Alternatives (and the puzzling Oprah reference) was so appalling. I’m sure you will get offensive (or at least eye roll-worthy) comments to this piece… but I guess at least it’s good to know where people are coming from. Oh … I see there are some already! So thank you again for saying so clearly what we as a movement need to hear!

Report comment

Thanks so much, Darby! 🙂 I remember well the reactions at the table you and I were sharing at Alternatives when that particular talk was going on. 😉

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks so much for this.It has been a long time coming

Dialogue is so important even if we slip and slide with our words.

I always fee torn and worried because I ave been partly aware since childhood

I am thinking now there may have been more of a family story that I was initially given since my family was aware of Paul Robeson and his life- my mother had membership in the NAACP-my grandmother talked of a quadroon student being a student in her Normal School-and my mother was very aware of the whiteness of state institutions for those folks family didn’t want to care for

So I am wondering about this because it affects me and how I can interact and support without bein dismissive or racist

I try and sometimes have gotten into trouble – being punkslipped-because I did make an issue

My hardest part is speaking with folks who are dyed in the wool raciists. I don’t speak up or give up at the

We can agree to disagree part because it seems a failing cause especially if it is a work or business interaction

I just don’t give them any more of my business

So thanks again

We need to do more and I would love all of your thoughts on the recent SNL scene with Tom Hanks playing in the Family Feud game

Interacting is so helpful to me in growing as a human being

Isolation is intellectual confinement

Report comment

CatNight,

Thanks for chiming in! 🙂 I’m not personally familiar with the Tom Hanks SNL skit. I’ll have to look it up! It can indeed be a hard call when to speak up and when not to, but, of course, if our whole culture started shifting to speaking up being the norm, the personal risks would start to (I’d hope!) go down…

-Sera

Report comment

Thank you CatNight, Paul Robeson was a great man. Your mother must have some great stories from those early NAACP days.

Report comment

I will stop comparing institutional psychiatry to slavery. Institutional psychiatry doesn’t compare to slavery so much as it IS slavery.

There are other isms besides racism. One of those isms is sanism or mentalism. I’m surprised that mention of the topic never came up in the course of the post.

I respectfully disagree with most of statements made in this post. I don’t disagree that there has been a change of administration, and that this change of administration is going to make a great many things worse for a great many people. I’m sure it is going to make matters worse even for people who are not black.

We’ve got a climate change denier and thorough-going oligarch in the White House. His appeal to racists only touches the surface of the many problematic matters arising with the administration ascendant. Hopefully it won’t be long until we can say to Mr. Trump, “You’re fired!” I hope people can take to the streets and make their resistance this repressive regime and their outrage known.

Report comment

Frank, sometimes it takes really bad things to happen for people to wake up to what others have been saying for centuries. We shall see how many folks start marching in the streets January 21, 2017.

Trump could well be our worst thing.

Report comment

Frank,

I’m not surprised to see you here saying this, and I’m expecting Oldhead shortly. 🙂

However, even if you believe – without a doubt – that psychiatry *is* slavery, I continue to be left wondering why it’s such an important concept to you that you’d be willing to alienate and hurt so many people of color just in order to hang on to it?

-Sera

Report comment

The ancient Greeks and Romans practiced slavery. It wasn’t, until much more modern times, an institution directed against specifically black people.

I would no sooner promote institutional (coercive non-consensual) psychiatry than I would promote what we used to call, here in the south, “our peculiar institution”.

I’ve seen people compare that with coercive non-consensual sex because it does bare comparison. I think the same is true of chattel slavery.

Report comment

You’re not answering my question, Frank.

We already addressed in the blog the issue of ‘slavery’ meaning several different things…

What I’m asking *you* is why the comparison is so important… So essential.. .That it’s worth hurting and alienating people in this country who are descendants of those of African descent who were enslaved… ?

Report comment

Sometimes folks latch onto an idea because it speaks to something deep within. Even though they may know the issue has serious concerns from others the only thing that matters is that the concept meets their reality. These movements within the MH, psych survivors etc, have shown this to be the case time and time again. No other voice is to be taken seriously if that voice is not white, old, and seemingly healthy emotionally and mentally. What a shame this was supposed to be a revolutionary movement.

Report comment

Because there have been arguments made to the effect of saying imprisonment and torture, for the designated “mental ill”, are freedom and treatment, and vice versa. I’m saying, yes, total and complete independence is very much worth stubbing a few toes, and scrapping a few thin skins. When the doors are locked, and people are not free to come and go as they please, what you’ve got is a prison, not a hospital.

Report comment

Calling it prison, force, imprisonment, incarceration, etc is quite a bit different then calling it ‘psychiatric slavery.’ Is the latter necessary to discuss the former? And is *that* worth it?

Report comment

Not really. The opposite of a freeman is a slave. I’ve demonstrated on behalf of striking prisoners, too, and I don’t have any regrets about doing so.

Report comment

Not really. The opposite of a freeman is a slave. I’ve demonstrated on behalf of striking prisoners, too, and I don’t have any regrets about doing so. Yes, it is.

Report comment

Sera, if Comparing psychiatric oppression to slavery than I would come at this from a different perspective, but I think most dismiss us from the get go.

It seems like you alienating people who play a key part in this movement. There aren’t many places to express the effects of this kind of oppression. Many had to hold back a lot with psychiatry.

Frank expresses stuff I bet a lot of people want to, but fee like they can’t. The same is true for Oldhead. Also many have been working hard to keep people up to date.

If you want to discuss on some level, how our launguge, and approach could be improved, that’s one thing. Just think these things should be approached as a discussion. Also think we should also emphasize our movement disivers its own place too. Many have been shut down, in the past, and I don’t think that’s good for anyone.

Report comment

Kayla,

I’d just like to note once again that it would appear that the people who are saying that ‘psychiatric slavery’ is okay or not racist or that it’s okay that people have different opinions about it (and that those different opinions are essentially all equal) at least appear to be white. (I don’t know this for sure, but the people who I *do* know are certainly at least white presenting.)

So, why are the opinions of white people equal to the opinions of black people on matters that are related so directly to our country’s history of slavery and racism? How strongly would we argue against the idea that a psychiatrist’s opinion should NOT be seen as equal to the opinion of someone who’s survived the system on matters of psychiatric oppression?

I’m not worried about alienating people, Kayla. Discussions of racism almost always bring up defensiveness, push back, and poor responses especially by white people. I *am* admittedly a white person, but I also see it as my job to get very okay with this sort of ‘alienation’ you speak of.

Over on the Mad in America Facebook page one of the things I said I will repeat here: When people push back against these conversations in this movement, the expectation seems to be that everyone stop ‘fighting,’ but that they do so in a way that is consistent with the ‘default’ … And the default is almost always the expectations that have been set by the dominant group. In this movement, that dominant group is (like in so many other realms) white people.

The way *together* – as far as I can tell – is to stop expecting people be okay with the default, to speak honestly about these issues that are very real in this movement, to work *through* the feelings of alienation and defensiveness, and to work toward getting to a point where we *respect* each oppressed groups voice, value, and experience in real and intentional ways.

I can’t imagine going in any other direction. In the end I just keep wondering why more people aren’t concerned about how white this movement is… why we keep coming back to this same place.

-Sera

Report comment

Can you please speak what you actually mean, an not use symbols to imply my quotes mean something different, and expect me to know this?

You spoke of alienating other groups, and don’t care about alienating people from within. What are you trying to accomplish?

I do generally think this can be worked out, but it seems like you are ignoring the backlash we get from, “progressive” groups, who seem to think they hold the ultimate truth in this area. Hence why I think shutting down conversation is so dangerous.

Also another point I was trying to make about turning on each other. “When asked about this topic, Suman Fernando (a Black psychiatrist originally from Sri Lanka currently residing in England and who has done a great deal of work related to racism and psychiatry) had this to say” How is this not doing the very thing you accuse others of?

Report comment

Kayla,

I generally don’t understand what you mean either at the start or the end of your comment.

Can you say more? How am I not saying what I mean? How is quoting Suman related to what we are saying is a problem in the movement?

Sera

Report comment

When you type a *word* I say out of context. Like that.

You are saying psychiatric survivors don’t understand black peoples experience when comparing ours to theirs, but you use an example of a psychiatrist. Psychiatrists have literally oppressed many people on the site. Again how is that not doing, what you accuseothers of?

Report comment

Kayla,

Okay, still not so clear on what you mean at the top there… Do you have an example?

But regardless, what I am saying is that people who hold one sort of privilege aren’t in a place to fully understand the systemic oppression that corresponds to the other side of that privilege.

So, as the blog says, Suman is not someone we should go to to understand psychiatric oppression, because he holds the *privilege* end of that particular stick. But he *does* know what it’s like to live black in this world, and has made his career around trying to share, educate, and understand that within the psychiatric system, as well.

*I* am on the privilege end of the stick when it comes to race in this country, as are (as best as I can tell) *most* of the people speaking up on this thread. So, I defer to him and many others of color, and work hard consistently to be aware of my impact on this movement as a white person who doesn’t want this movement to stay so white or feel alienating or not relevant to black people and other non-white people. I would expect him to defer to me when it comes to the topic of psychiatric oppression. By (hopefully) respecting each other’s experiences of systemic oppression and trying to make what is invisible to each one of us for not having experienced it first hand by *listening* to the other and accepting what they say largely as the truth.. THAT is how we come together.

As a side note: I reached out to Suman in particular because in a previous conversation about ‘psychiatric slavery’ on these Mad in America boards, someone attempted to cite Suman’s work as evidence in *favor* of use of the term. So, I e-mailed him and asked him. That is what I got back.

-Sera

Report comment

Why should groups try to avoid “alienating” some people. If you aren’t worried about “alienating” us.

Forget psychiatric oppression, and racism for a minute. Every movement is a difficult balance between, putting forth challenging ideas, but also being understanding of the other side. Well, conflict, communication, and understanding in general is.

If I’m being honest this mostly just seems antagonistic, and I don’t see it as being a place to create understanding. To be honest it seems Allen Frances like. This is a group who is often oppressed, and is being accused of oppression. Guess it wasn’t one part of what you said, or how you said it, but the sum of the whole.

Report comment

“The way *together* – as far as I can tell – is to stop expecting people be okay with the default, to speak honestly about these issues that are very real in this movement, to work *through* the feelings of alienation and defensiveness, and to work toward getting to a point where we *respect* each oppressed groups voice, value, and experience in real and intentional ways.”

Report comment

That all seem so strange to me, Kayla. Because you don’t like the tone of people speaking up, it at least *sounds* like you’re equating that with the oppression they’ve experienced?

When I hear that, I think of so many clinicians and psychiatrists and others in the mental health system who expect us to always be nice, calm, friendly, and do our best to make them comfortable when we state what is wrong. *That* feels like a common component of all sorts of systemic oppressions. This idea that we can ask for change as long as we don’t make people too uncomfortable along the way… It feels bad to me when I hear that from people in the mental health system, and I’m very aware that I’ve heard that that feels bad to many black people and others of color when they hear that from white people. (I’m not saying as a whole group, but it is a common theme that I have heard, nonetheless, and it makes a lot of sense to me.)

I suppose if you don’t like the conversation you certainly aren’t required to stick around for it… But I want to challenge the idea that every push back or talk about racism has to come from a place of not wanting to ruffle any feathers.

Report comment

I don’t like the tone, or the delivery of this artical. Not any hypothetical people speaking up. That’s another issue.

More specifically the fact that this seems to close the door on conversation. It’s also the way your responding to comments. I feel like you’re not really hearing people.

I can only speak for myself, but your really not hearing what I’m saying.

Report comment

Well, admittedly (as I did say above), I’ve had difficulty trying to understand what some of your points have been. I’m sorry that you’re not feeling heard, and I’m sorry that you don’t connect with the blog.

But, I only say that from a place of ‘Oh, I wish everyone liked me and everything I was a part of producing, and I was a part of co-writing this, so I wish everyone liked it…’

But, then, Earl, Iden and I all knew that everyone wasn’t going to like this… But it sure still felt important to say. I feel good about it, and I feel good about the fact that so much of its content has been written by, approved of, contributed to, etc., by people of color who’ve attempted to be a part of this movement and/or have first-hand experience of what this blog speaks about.

I hope you find something you like better… But I hope that it still challenges you to think more about these issues.

Report comment

That’s my point. I feel this is very disrespectful. I’ve not given my opinion. I’m trying to just discuss the importance of dialog, and feel talked down to. Challenge the way I look at what? All I’ve spoken of was encouraging dialog.

I’m to you as a person, not to blacks people, or people of color. Not to any group of people. This seems like. An abrasive, and uniting view from you. Stop making me sound not understanding of groups I’m not speaking to.

This is antagonistic, and hypocritical.

Report comment

The grammar is a bit off. I was flustered. I just have a problem when someone, acts like they can say whatever’s because they’re ‘speaking for a group’. I’ve heard psychitry do it to us. I’ve heard liberals do it to blacks too.

Report comment