Randomized controlled trials are seen as the gold standard for guiding “evidence based medicine,” and up until recently, I didn’t pay much attention to the “kind” of evidence they provided. But after writing recently about two meta-analyses of antipsychotics and antidepressants that concluded these drugs were “effective,” I have come to think of RCTs in a new light.

The most important data in an RCT is not whether the drug provides a statistically significant benefit over placebo. The most important data is the “number needed to treat” calculation (NNT). This is the data that should be used to provide patients with informed consent about the likelihood that they will benefit from the treatment over the short term, or, conversely, be harmed by it. And it is this data—and not efficacy data—that should inform prescribing protocols.

In the past, I have written about the corruption in the RCTs of psychiatric drugs—the bias by design, the use of a placebo group composed of people withdrawn from their drugs, the spinning of published results, and so forth. But this post is about something different. Even if we take the RCTs of antipsychotics and antidepressants at face value, the NNT data from the meta-analyses reveals that the overwhelming majority of patients do not benefit from the treatment, and thus are harmed, at least to some degree, by their exposure to the drug.

In short, the NNT numbers provide evidence for utilizing the drugs in a selective way, and avoiding their immediate use in first-episode patients.

Efficacy vs. NNT Findings

The finding of efficacy in a trial of a psychiatric drug comes from calculating aggregate outcomes for the drug and placebo groups. If the reduction of symptoms, on average, is greater in the drug group than in the placebo group, and if this difference is statistically significant, then the trial is deemed to be positive for the drug. The treatment provides a benefit over placebo.

This is the evidence that is cited in psychiatry for using antipsychotics and antidepressants as first-line therapies for depression and psychotic disorders. These drugs—and this is how the findings are presented to the public—can be said to “work.”

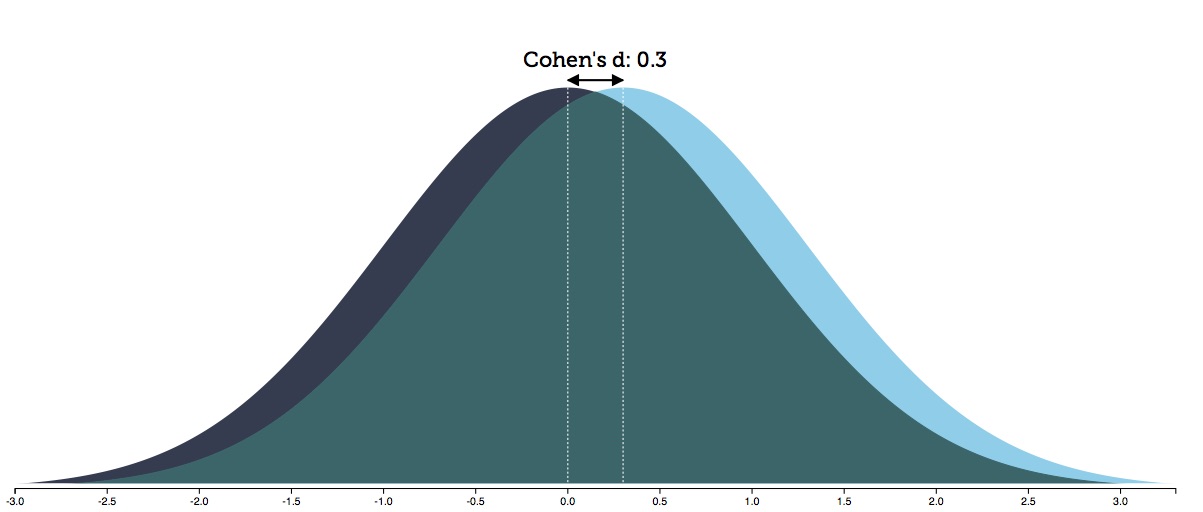

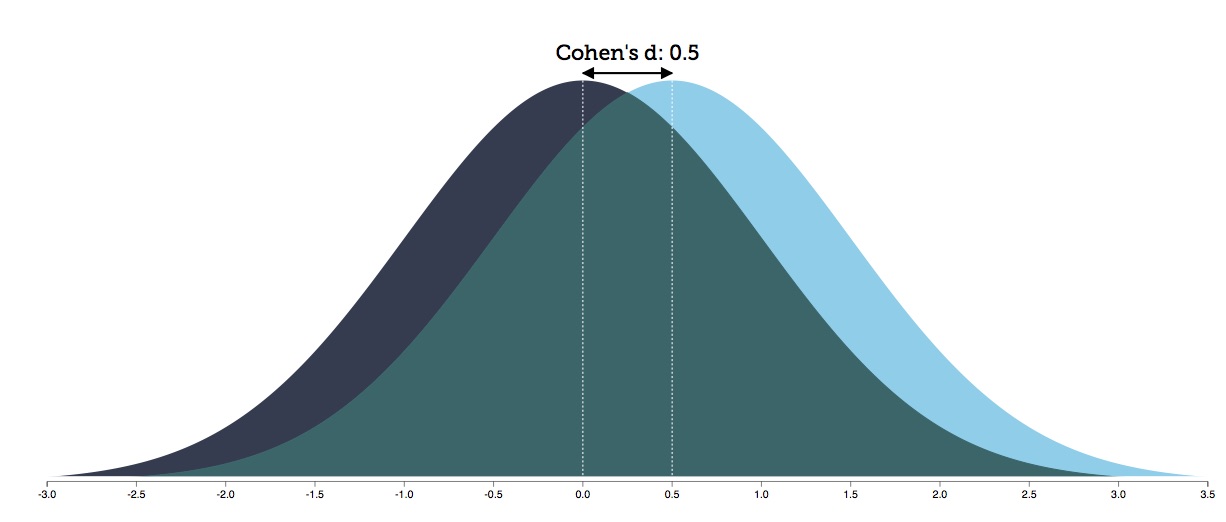

However, the individuals in a trial of a psychiatric drug, in both the placebo and drug-treated groups, will have varying responses: some will worsen, some will stay the same, some will get a little better, and some may get a lot better. If you plot out the individual responses in the two groups, the bell curves for each group will overlap to some degree. The degree of overlap is reflective of the “effect size,” and that in turn leads to a calculation of the number of people who must be treated to produce one additional person who receives a benefit from the drug (NNT).

Thus, the NNT tells of the percentage of people who are being exposed to the adverse effects of the drug without any additional benefit, and the percentage of people who have a positive therapeutic response they otherwise wouldn’t have had. The first group could be said to have been harmed by the treatment, while the second group could be said to have benefitted from it.

For instance, an NNT of 10 means that 10 people must be treated to produce one additional person who has a positive outcome, which leads to this benefit-harm equation: nine people will be exposed to the adverse effects of the treatment without any additional benefit (and thus are harmed), while one will have a beneficial response that he or she would not have otherwise had.

With an NNT number in mind, a person contemplating taking a drug can assess whether the odds of having a better response that comes with use of the drug is worth the certain risk of being exposed to the drug’s adverse effects. That’s the equation patients should look to when considering whether to take a drug, as opposed to the “efficacy” finding we usually focus on.

It’s easy to appreciate the dramatic difference in understanding that comes from seeing the merits of a drug through the NNT lens, as opposed to the effective/not effective lens. The first provides a sophisticated understanding of the risks that come with taking the drug and reminds patient and prescriber alike that individual outcomes may vary widely. The latter leads to a simplistic “drug works” conclusion, which promotes the false notion that most patients can expect to benefit from the treatment.

In other words, the NNT illuminates the drug’s variable impact, while the efficacy finding leads to a hiding of this critical fact. The efficacy data, in fact, could be said to lead to a clinical delusion.

The NNT for Antidepressants

Irving Kirsch and others have calculated that antidepressants, in the RCTs, have an effect size of .30. Here is a visualization of a treatment with an effect size of .30:

In this graphic, there is an 88% overlap in the spectrum of outcomes between the two groups. This produces an NNT of 8. One in eight people treated with an antidepressant will have a positive response they otherwise wouldn’t have had; the other seven will have been exposed to the adverse effects of the treatment without receiving any additional benefit.

Thus, for the person considering taking an antidepressant, the NNT data provides the “math” needed to weigh the potential benefit of taking the drug against the potential harm of doing so. The patient will know they have a one-in-eight chance of doing better than they would without the antidepressant, and thus the question for the patient: Is this possible benefit worth the negative aspects of being exposed to the drug?

To complete that informed consent, the patient would need to have an understanding of the possible negative effects of exposure to an antidepressant. The side effects are many, starting with sexual dysfunction and an increased risk of having a manic reaction, which may lead to a bipolar diagnosis. Other possible negative effects include suffering withdrawal symptoms when trying to quit the antidepressant and possibly ending up on the antidepressant long-term, which in turn often leads to a host of physical and emotional difficulties.

Many depressed people, presented with this information, might still choose to take an antidepressant. They would see it as a worthwhile risk. At the same time, many would likely choose to forgo taking the drug and seek out a non-drug alternative.

My own guess is that the vast majority of people, when confronted with the NNT of 8 finding, would take the second option, particularly when suffering a first episode of depression. Unfortunately, very few patients are presented with the NNT data when they are considering taking an antidepressant, and such data rarely informs the thinking of prescribers.

It should be noted too that this NNT of 8 is derived from industry-conducted trials of antidepressants, and that in studies of “real-world” patients, such as the STAR*D trial, drug-response rates have been much lower. It may be that in “real-world” patients, antidepressants provide no “efficacy” benefit at all over placebo in the short term. The NNT-of-8 calculation is a best possible scenario for assessing the benefit-harm ratio for short-term use of an antidepressant.

With Antipsychotics the NNT is 6

In a 2009 report, Leucht published a meta-analysis of 38 trials of second-generation antipsychotics and reported a response rate of 41% for the drug-treated patients versus 24% for the placebo group. These percentages, they noted, produce an effect size of .50, which translates into an NNT of six.

Six people must be treated to produce one more person who has a favorable response. The other five (80%) can be said to have received no additional benefit from the treatment but were exposed to the adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment, which, as is well known, are many.

The responder percentages cited by Leucht make it easy to see the benefit vs. harm equation in the use of an antipsychotic. Those harmed are the non-responders to the drug (59%) and those who would have responded without the treatment (24%), which equals 83% (or roughly five of every six patients.)

The adverse effects of antipsychotics are almost too numerous to list. Second-generation antipsychotics may cause weight gain, diabetes, metabolic dysfunction, Parkinsonian symptoms, cognitive slowing, emotional numbing, and brain shrinkage. It can be difficult to withdraw from an antipsychotic, and the risk of long-term use includes tardive dyskinesia and a host of other negative effects.

Thus, the benefit versus harm equation that comes from Leucht’s meta-analysis: Is it worth it for a patient who is “psychotic” to take an antipsychotic to gain this one-in-six chance of having a favorable response they otherwise wouldn’t have had, with this possible benefit coming at the expense of exposure to the adverse effects of the drug?

NNT-informed Prescribing Practices

The NNT data reveals that the majority of patients will be harmed to some degree by taking an antidepressant or an antipsychotic, even over the short term. With antidepressants, 88% will fall into this category of being exposed to the drug without any additional benefit; with an antipsychotic, 80% will fall into this category.

Given this fact, it is easy to understand that RCTs in psychiatry do not provide an “evidence base” for “one size fits all” prescribing practices. Instead, they provide compelling evidence that prescribers need to develop “selective use” protocols, which would seek to identify those who could get well without the drug treatment, and seek to halt treatment in non-responders to the drug.

Placebo response vs. drug response

There is ample evidence that recovery from a depressive or psychotic episode without exposure to drug treatment puts the patient onto a much better long-term path. Relapse rates are lower for those that recover without medication, and their long-term functional outcomes are better too.

There is a fairly easy way to identify those who might get well without drug treatment, particularly with first-episode depression or first-episode psychosis. Prescribers, while providing psychosocial care, could utilize a watch-and-wait practice. Wait for a week or two to see if the patient begins to improve without the drug, and this would help identify those who could get well without the drug.

This is the antipsychotic protocol used in the Open Dialogue program developed in western Lapland in Finland, starting in the 1990s. They have reported that two-thirds of their first-episode psychotic patients recover without the use of antipsychotics and are well at the end of five years. Their results tell of the extraordinary public health benefit that can come from a watch-and-wait practice.

As for first-episode depression, prior to the marketing of the SSRIs, it was understood that depression was an episodic illness, and that most people could be expected to recover in time without any somatic intervention. Indeed, in the early years of the antidepressant era, a common thought was that the drugs were useful because they could speed up this natural healing process.

Thus, the benefit that would come with a watch-and-wait protocol is not simply that some patients would avoid the drug’s adverse effects over the short therm. Recovery without drug treatment also puts patients onto a better long-term course, as can be seen most clearly in the Open Dialogue outcomes.

Drug non-responders

The RCTs of antipsychotics and antidepressants tell of a significant percentage of patients who do not get better on the drug. Given this fact, the second part of a selective use protocol would be to stop prescribing the drug to non-responders, and to try other therapeutic methods instead.

This seems rather obvious—why prescribe a drug that doesn’t work—and yet the current practice is to double down on the drug treatment. Doctors put non-responders on additional drugs, and soon these patients are on a polypharmacy regimen, and struggling with a mounting burden of side effects.

The NNT numbers warn prescribers that there will be many non-responders. If prescribers were to adopt a selective-use protocol, they would try to identify these non-responders quickly, and switch them to a non-drug therapy. This would be an essential aspect of a prescribing protocol that sought to determine “for whom” the drug works, and “for how long,” which is understood to be the question that needs to be answered in order to make “best use” of a drug.

A Unified Body of Evidence

In Anatomy of an Epidemic, I presented the evidence base for psychiatric drugs in this way: I wrote of how RCTs provided evidence of their short-term benefits (at least to some small degree), and then examined evidence of many other types—epidemiological studies, longitudinal studies, MRI findings, and so forth—that told of how psychiatric drugs worsened long-term outcomes.

In other words, in that book, I told of a paradox: drugs that “worked” over the short term, but caused harm over the long-term.

However, if you focus on the NNT data from the RCTs, the paradox disappears. The RCTs tell of a majority of patients who do not benefit from the drugs, and thus are harmed by one-size-fits-all prescribing practices. Specifically:

- They tell of a significant percentage of patients who would have recovered over the short term without the treatment but have now been exposed to the drug, and this may put them onto a path of long-term use of an antidepressant and other psychiatric drugs, which is fraught with possible negative effects.

- They tell of a significant percentage of medicated patients who are non-responders and soon head down the polypharmacy rabbit hole.

Indeed, the RCTs and long-term outcomes literature now come together to tell of a paradigm of care that, as currently practiced, leads to more harm than good for patients right from the first moment. The biggest risk for first-episode patients is that first use of a drug will turn into long-term use, which means that in return for a small chance—1 in 8 for antidepressants, 1 in 6 for antipsychotics—that a person will have a better response on drug than on on placebo, that person is exposed to a significant risk that they will become a long-time user of a psychiatric drug.

There are hundreds of personal blogs that have been published on MIA that tell of this short-term to long-term pathway of harm. The authors tell of either not responding to the drugs in the first place or gradually worsening on a psychiatric drug, of falling into polypharmacy torment, and eventually of lives that were diminished or even ruined. Their personal stories attest to the very outcomes that are visible in the RCTs and long-term outcomes literature, if only the profession would take a close look at its own findings.

In the solutions section of Anatomy of an Epidemic, I wrote that psychiatry needed to adopt selective-use protocols, based on two precepts: avoid immediate use of drugs to identify those who can get better “naturally,” and try to minimize long-term use, which includes stopping treatment in non-responders.

The NNT numbers from the short-term RCTs argue for this same selective-use protocol, and this was the aha moment for me. There is a consistent evidence base, starting with the RCTs that assess short-term outcomes, that calls for psychiatry to dramatically rethink its use of these drugs and to adopt selective-use protocols. As long as it fails to do so and clings to its one-size-fits-all protocols, psychiatry will be using the drugs in a way that does—and there is no other way to put it—great harm.

What you say is extremely reasonable. Unfortunately in a society where physicians use drugs to solve all sorts of problems, change is unlikely. Too many people benefit financially by maintaining the status quo. The NNT is high for many drugs commonly promoted (by doctors and medical associations as well as by pharmaceutical companies). For example:

Statins for people who have no heart disease: at least 104

Anti-hypertensive medication in people with relatively non-severe high blood pressure: 118

Daily aspirin to prevent heart attack or stroke in people with no previous heart disease: 1167

Bisphosphonates to prevent fractures in those with low bone mineral density: 50 for primary prevention

Report comment

This could be the next Money Making Scheme:-

Over 40s health check to include dementia advice – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-44502861

Report comment

I am neither a scientist nor very well mathematically informed, but what you say about the numbers only makes sense. This is a very clear piece of data (NNT numbers) that I should hope the public would be informed about, but when even I, who reads everything he can about the subject, have no idea what all of this means, then the general public is bound to be hopelessly misinformed of what’s happening. I can only hope that these conclusions will form a chapter of your latest book.

Report comment

Dear Mr. Whitaker,

Currently, research cited by MIA tends to prove that:

_ anxiolytics aggravate anxiety in the long term,

_ antidepressants aggravate depression in the long term,

_ antipsychotics aggravate psychosis in the long term.

Therefore:

“anxiolytics” should be called: “anxiogenic drugs”

“antidepressants” should be called: “depressogenic drugs”

“antipsychotics” should be called: “psychosogenic drugs”.

Since then:

Why advise a anxious, depressed or psychotic person, a “selective use” of anxiogenic, depressogenic or psychosogenic drugs? For their short-term effects? But, if the long-term effects cancel the short-term effects, and even reverse them, should not you be for the complete prohibition of all these drugs?

There is an inconsistency in your remarks, a political inconsistency.

Rigorous scientific reasoning leads to the conclusion that psychotropic drugs should never be used to solve social and psychological conflicts (“madness”). I think you do not come to this conclusion for political reasons, because you do not want to sound too radical.

You play in the center.

Report comment

How do you make your money Sylvain?

Report comment

Sounds like the ad hominem approach to argumentation.

Report comment

Rigorous scientific reasoning leads to the conclusion that psychotropic drugs should never be used to solve social and psychological conflicts (“madness”). I think you do not come to this conclusion for political reasons, because you do not want to sound too radical.

I’m sure there’s a better answer, right Bob?

My whole conundrum/exasperation with RW’s research has always been that, combined with the Szaszian deconstruction of psychiatric ideology, it destroys any minute trace of credibility that psychiatry might have ever possessed, and points to the obvious conclusion that it serves no valid function. So why the talk about “appropriate” anything insofar as the prescribing of neurotoxins?

Report comment

Psychiatry serves two functions. Hope and security.

The hope is for desperately unhappy people and their family members. Hope that the next magical pill will solve all life’s problems, destroying all pain and maximizing pleasures associated with living.

The security is for those worried about crime and acts of violence. Psychiatrists assure the public that they can know–by scientifically verified magic–who will commit crimes and they can save these people from themselves and society from THEM.

Of course the hope and security are illusions. But when we critique or question psychiatry people get very angry. We popped the pretty soap bubble they based their lives around.

Report comment

A twisting of justice.

“It is better ten innocent Persons should be found sick-guilty and “helped” (tortured by psychiatric drugs and psychiatric prison), than that one sick-guilty Person should escape.” says Psychiatry.

the original

Sir William Blackstone, who lived from 1723 to 1780, “It is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer.”

Second Rosenhan Experiment

“Rosenhan used a well-known research and teaching hospital, whose staff had heard of the results of the initial study but claimed that similar errors could not be made at their institution. Rosenhan arranged with them that during a three-month period, one or more pseudopatients would attempt to gain admission and the staff would rate every incoming patient as to the likelihood they were an impostor. Out of 193 patients, 41 were considered to be impostors and a further 42 were considered suspect. In reality, Rosenhan had sent no pseudopatients.

Report comment

I don’t think heard of the Rosenhan experiments until very recently. (Why not?) I know there are criticisms, and yet, I think the studies are very telling, and significant to my own experience as well.

Abilify (possibly in combination with other “medications”) caused me to hear voices. When I told my then psychiatrist about it, instead of correctly blaming the drug, I was given an additional incorrect diagnosis of “schizoaffective.” Of course, once I went off Abilify, the voices ceased entirely (although it took some time). I was further vindicated by finding another person who had the same “side-effect” from Abilify and from another psychiatrist who believed me and listed the drug as an “allergy” – probably not quite correct, but the best she could do in their computer system.

And I also very much appreciate your comparison between psychiatry and the Blackstone quote.

Report comment

Ms. Monique, I always felt the “meds” messed up my thinking. But no one believed me. My parents did at first Mom said, “Rachel never was this bad till she went on Anafranil.” The shrink said it was my fault I went crazy. If I weren’t mentally ill the life-giving medicine would never have hurt me.

When I read William Glasser, Terry Lynch, Bob Whitaker, and others I felt relief. I was right after all. it really was the pills making me crazy!

Some people get angry, insist that they are too bipolar, their pills are “salvation” and become quite hateful. (They often post these misspelled, ungrammatical rants in all caps.) I don’t understand that behavior at all. I never aspired to be a career mental patient myself.

Report comment

Rachel – Thank you for sharing that. So glad you figured it out. I didn’t read “Anatomy of an Epidemic” until I was off the drugs (“meds”) for a while, but when I did, it was like “Ohhhh this is actually a thing. It’s not just me.” What an eye opener and a relief!

Report comment

I was literally tortured by psychiatry at the age of 19 on my first breakdown,( now 50). I was given drugs/forced drugs that made me unspeakably thirsty and tied into a bed/gurney. No lawyer. No court. No one to appeal to , to get freedom.

Report comment

I like this article – I’m so fed up of “experts” saying somehow that the data doesn’t matter compared to their “clinical experience”.

I could not frankly believe how poor the NNT’s were for psychiatric drugs, particulary the antipsychotics actually, which really are not very good for the harm they always cause.

I think NNT or effect size should be on the patient leaflet. NNT requires an agreed level of improvement in order to calculate it, but I see no reason why the Cohens effect size could not be published, its no less the the patient deserves for putting his/her physical health on the line. Its a measure of product performance such as we would expect on any product.

And in the UK, shouldn’t NNT or effect size be in the NICE and the Maudsley Guidelines?

As an aside, I was aghast At what Dr Cipriani et al said recently, that “there was an undue focus on the binary and polarising question of clinical significance”. Honestly, you could not make it up. Whats binary and polarising are ludicrous quotes from the “experts” that AD’s “work”, “final answer” etc, etc. NNT or effect size is the right way to explain how well a drug works, not evidence-free catchphrases that are becoming risible.

Report comment

‘I could not frankly believe how poor the NNT’s were for psychiatric drugs, particulary the antipsychotics actually, which really are not very good for the harm they always cause.’

Makes me wonder what the NNT is for antipsychotics being prescribed as “adjunct treatment” for depression, for which they are now often touted.

‘Dr Cipriani et al said recently, that “there was an undue focus on the binary and polarising question of clinical significance.” ‘

Apparently one of the perks of becoming an “expert” is that you are allowed to selectively ignore the scientific evidence.

Report comment

Yeah thats a good question, I have heard the “mood lift” property of Quetiapine, for example, mentioned many times. Although I cannot actually see why a drug that sends you sleep, makes you fat and gives you diabetes and metabolic issues would perk you up, but oh well, psychiatrists will believe anything.

Just googling around, I found an Australian Meta-Analysis by Spielmans from 2013 which mentioned NNT’s of the adjunctive AP to be 7-10 with an effect size of 0.34. Not very good! And the Olanzapine/Fluoxetine combo had an NNT of 19. Oh dear.

They said:

“All of the studied drugs except risperidone demonstrated substantial risk of several adverse events”

and

“We interpret the effect of adjunctive antipsychotic treatment on depression measures as of questionable clinical relevance.”

They concluded with:

“Taken together, our meta-analysis found evidence of (1) some improvement in clinician-assessed depressive symptoms, (2) little evidence of substantial benefit in overall well-being, and (3) abundant evidence of potential treatment-related harm.”

To me, that’s a pretty rosy assessment of adjunctive AP . Once you get into effect sizes of 0.3 and NNT of 8+ and you know there is publication bias and the depression scale favours sleepy drugs – well you have to entertain the likelihood that there is actually nothing there. The damage done, however, is pretty certain, because thats what these drugs do – primarily they disable neurotransmitters that you actually need working to stay healthy.

Report comment

ConcernedCarer:

Thanks so much for this additional information. I have a hard time getting my head around finding out such things (and I think it’s partly because my brain is still healing from being on these drugs), so I appreciate very much that you made the effort.

And as for the data that you outlined so clearly, my best response is “Yikes!”

Report comment

Best regards for your continued recovery Monique. I find it useful to check out the science, and Robert has pretty much taught us how to go about that. I’ve yet to find a pro-drug psychiatrist who will stand their ground in the face of the evidence, so if there is one here who disagrees, I hope they put forward their alternative view backed by evidence, because the orthodox case is somewhat listing in the water right now.

Report comment

ConcernedCarer: Thank you for your response, and I’m sorry to keep going on about this, but I feel the need to add that I actually have a master’s degree in a science field (not a biological/medical/life science) and my thesis was about statistics. So, ugh, I understand stuff and yet there are areas that I still can’t “get my head around.” Very frustrating, and I do appreciate your encouragement.

Report comment

Dear Bob,

The idea behind Severe Mental Illness is that it is very disabling. *But my own disability ended when I stopped taking strong psychiatric drugs.

You have mentioned Neuroleptic withdrawal “High Anxiety” syndrome in your writings. I certainly suffered from this, even though I tapered carefully from the drugs.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SOLUTIONS

What I found was that if I was able not to engage with the Anxiety it gradually diminished ; and when it diminished it was no longer a problem. This might be described as a Buddhist (or CBT) solution. But this Approach can be PROVEN to work (for Normal Anxiety and Severe Anxiety)

As regards Neuroleptic Danger:- the drugs I consumed had the acknowledged “side effect” of Akathisia. This side effect is recognised by the FDA as a potential cause of suicide, and every hospitalization I had (besides the first one) over a four year period was a Suicidal Event.

These drugs are also practically guaranteed by the manufacturer to cause Tardive Dyskinesia in the majority of consumers.

My historical Psychiatrist was also a University Researcher, who promoted these drugs through positive Research Papers.

The SUICIDE rate in Ireland at approximately 400 deaths per year is about 10 times the HOMICIDE rate at approximately 40 deaths per year. *My SUICIDAL Hospitalizations stopped when I stopped consuming Strong Psychiatric Drugs.

Report comment

Bob

I agree with what you say about the overstatement of evidence, and that people are being duped about the effectiveness of psychotropic medication. However, the harms they cause are a separate matter, aren’t they? I just wonder whether this should have been made clearer.

Best wishes, Duncan

Report comment

Could you clarify why you think the harm done by psychotropics is irrelevant to whether or not they are effective.

Report comment

“Overstatement of evidence”, what exactly do you mean by that?

Report comment

I didn’t mean that harm done by psychotropics is irrelevant. It’s just that using something that is ineffective may not be a proper measure of harm. Evidence is always open to interpretation and can be overstated because of bias.

Report comment

What would be a proper measure of harm? I don’t quite follow your logic.

Report comment

“Open to interpretation and bias” seems to imply mischievous intent. Which is what it is.

Report comment

Irrelevant in relation to their effectiveness. Which is what you said. Not irrelevant without qualification. I don’t understand why you think it’s a separate issue.

Report comment

If a drug isn’t beneficial, what is it? I think harm is very much a part of the equation, otherwise you’re just writing off functional impairment, parkinsons, metabolic syndrome, TD, etc., etc. If 1 in 8 or 1 in 6 benefit, what’s up with the others? I wouldn’t, for example, call non-benefit beneficial. These controlled studies are performed to get drugs approved for use by the FDA. Nobody is conducting controlled studies to get substances disapproved for use by the FDA. The very fact that there is so little benefit should be a scandal, and it isn’t. This, I imagine, is because rather than science, what you’ve got going on here, are rites being performed by the “mental illness” denomination clergy. The doctor is administering drugs, in other words, for the same reasons the priest administers ‘holy water’. He thereby receives validation in his role as priest or doctor for the potential miracle of having gone through the motions, motions that, in other words, must in almost every last case, literally accomplish no more than a placebo.

Report comment

“The very fact that there is so little benefit should be a scandal, and it isn’t.” Amen to that.

Report comment

“…If a drug isn’t beneficial, what is it?…”

Its something that disables a person and makes them easy to control (- if it’s a Neuroleptic).

Report comment

Thanks for these comments. Marie, on the high NNT of other drug interventions–I think this is the point of why NNTs should be the focus for informed consent for medical interventions of all types. They allow the individual to assess the “odds” of having a better outcome than they would without the intervention (regarding the target symptom or problem), versus the “harms” that might come from the treatment.

This leads to Duncan’s comment about the “harms” being a separate matter. Well, in this piece, I am using “harm” to describe being exposed to the adverse effects of a psychotropic without benefitting from the treatment on the “target symptom.” Then the question is what are those adverse effects, how common are they, and so forth. I don’t think these are properly identified at all, leaving people contemplating taking a psychiatric drug really in the dark when assessing the potential harms, particularly when initial use of a drug proves to be a gateway to long-term use. Trying to better understand the short-term and long-term risks/harms that can come from taking a psychiatric drug is the other half of providing informed consent, and this too is missing in terms of what people are told.

Report comment

Agree there is uncertainty about some of the side effects of psychotropics. These can be overstated as well.

Report comment

What is the uncertainty and what, in your opinion, can be overstated ?

Report comment

Or, as is more often the case, understated.

Report comment

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akathisia

“….Neuro-psychologist Dennis Staker had drug-induced akathisia for two days. His description of his experience was this: “It was the worst feeling I have ever had in my entire life. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”…”

This is why people attempt SUICIDE on Psychiatric Drugs.

Report comment

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/11/neuroleptic-drugs-akathisia-suicide-violence/

Report comment

It took me a long time to get that the psychiatric drugs were interfering with the part of my brain that I needed to explain (or, at first, even realize) how they were affecting me badly. I still struggle with how to explain that. Anecdotal? Yes. (And yet, quite significant to me personally.) However, I do think it points to what Frank said and one way that the adverse effects can be understated.

Report comment

No one ever overstated any dangers to me, Dr. Duncan. Or stated them for that matter.

Report comment

That’s what I meant!

Report comment

You left out, in your analysis, that, even if they are effective (rare) in the short term, or even in the medium term (2-4 years), after that, due to the brain having adapted to the poison (drug), it only causes harm. Then, what do you do?

Report comment

Robert, can you please refer me to studies that involved ECT. I am interested in the NNT when it comes to this form of “treatment”

Report comment

Brilliant observation and article. I can’t see how the “experts” can dispute this, but being as cynical as I am, I fear they will find a way, and it’s terribly unfortunate.

Learning to employ the concept of cost vs. benefits in my life has been extremely helpful and I’m glad to see it employed here. If the antidepressants were presented in the way you suggested, I doubt I would have ever taken them. The first one I took (Zoloft) did appear to “work” – but not completely – and I was suspicious even at that time that I would have improved just as much without it. As it was, several years later when I was struggling again, the Zoloft didn’t “work”and I thus spiraled down the “polypharmacy rabbit hole.” And I am still finding my way out, even after nearly 4 years off the drugs. (I was on the drugs for a total of about 14 years, I think.)

I want to say that even a stronger stance should be taken. I don’t know – maybe those one out of eight (or less, I know) really are “helped” enough to outweigh the costs. Are they? Or is it really the placebo effect, which of course isn’t that because of the negative effects that are also occurring from the very start?

Although I respect everyone’s right and responsibility to decide for themselves, I don’t believe the benefits ever outweigh the costs, and I hate hate hate these drugs and only wonder how long it will take for our society to look back in retrospect and see how horrendous “treatment” was (is) in our times. I am confident that this will happen more quickly due to this site and others like it, so I’m very grateful to you, Robert, and all who contribute here.

Report comment

Should patients receive informed consent about the potential harms of medications? Yes. Should the decision be left up to the patient in distress? No. Why? Well, here’s the rub: Humans are notoriously bad at playing the odds. Humans in distress are worse. Even when something has a high chance of harm, people in distress are willing to try it in case they might be one of the few people who benefit.

Take the lottery as one easy example. Poor people buy the overwhelming amount of lottery tickets. Even if they understand the millions to one odds that they will lose. Even when they’re hungry and spending their last dollar that they should spend on food. Even with all the warnings about the odds they will be broke again (or in jail or dead) within a short period of time (one to several years). We as humans are just really really bad at gambling.

Now you’re talking to someone who’s super depressed or experiencing psychosis and suggesting that they’ll have a 1 in 6 or 1 in 8 chance they’ll receive some benefit from the medication. In the mind of the person in distress, those are fantastic odds! Even in the face of almost certain odds of experiencing adverse effects, I think most people experiencing severe distress would take that in a heartbeat. Especially since we have a pervasive societal attitude now that we can eat whatever we want, not exercise, not make any personal effort at maintaining our health because there is a pill for everything and anything goes.

Given this massive cognitive dissonance on the part of the average citizen then, I think this needs to be a regulatory issue rather than a case by case issue. Guidelines need to change so that no one ever is given these medications on a first episode basis. And for those who experience episodic distress, there needs to be a cost benefit analysis done not between the doctor and patient but by a medical board to decide what other therapies would be likely to help more. Those therapies need to be low cost or free to the patient and easily accessible. Then only in the cases of absolutely intractable suffering does the medical board decide that the patient be allowed to choose to risk these dangerous drugs.

As we’ve seen with some cancer therapies, people will try absolutely anything even when the odds they will die from the treatment are greater than receiving any benefit. Psych drugs cause a living death for so many people that they need to be treated as an absolute last resort and should not simply be a matter of allowing a patient to gamble at will under the pretense of informed consent.

As an aside, I know the tortilla chips I’m eating aren’t healthy. I know they’re high in fat and calories and I need to only eat a few and then add in more activity to counter the additional calories. I know I’ll probably eat the bag while sitting in front of my TV or computer. When I gain weight and go to the doctor with my weight related ailments, he’ll advise me I need to eat healthy and exercise more. I know I can then take to the internet and accuse him of fat shaming and a legion of angry obese people (and their thinner defenders) will mob the doctor via nasty online reviews, messages, phone calls, and social media posts. All while the cost of medical care is skyrocketing and fewer and fewer people can afford it.

How do we get back to the understanding of personal responsibility and taking care of ourselves? Humans are terrible at playing the odds and doctors aren’t allowed to dispense common sense anymore, which is one of the things that led to them just writing scripts for everything. This goes way beyond the need for informed consent to really the need to relearn societally how to make wise decisions for ourselves and those around us. (Sorry for the tangent, but I feel like it’s a necessary part of the conversation.)

Report comment

This is a great point. The patient “will try anything” and the psychiatrist feels they “just have to do something” – neither of them are thinking straight.

Report comment

If Neuroleptics are of no benefit most of the time, then what would a person in crisis benefit from?

I think they would benefit from genuine Safety until the crisis resolves.

Report comment

Bob and Kindredspirit

Bob, great blog and further development of your critical scientific analysis of the overall harmful effects of psychiatric drugs throughout society. You have made a great case for the importance of NNT’s in analyzing the available data for the dangerous risks involved in the promotion and use of these mind altering drugs.

Kindredspirit, you also raise some excellent points about how people in general are so willing to take risks (sometimes enormous risks) to get some perceived benefit from potentially dangerous drugs and/or some other gambling type activities in society.

What has been left out of this discussion is how ALL of these important questions (of risk vs benefit) are both magnified, and their eventual course determined by a capitalist/profit based market place.

Big Pharma (in collusion with psychiatry) is able to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to control the overall narrative while advertising and hyping the so-called benefits of these drugs, while downplaying the harmed caused. The counter narrative of forces such as MIA and other critics, is allowed to promote its counter perspective, but it is a mere tadpole swimming in a sea of sharks.

Here the “Powers that Be,” that control the entire status quo, can say there is “free speech” and that the public has so-called “equal access” to a counter narrative, but we all know that the access to the “truth” is NOT on an equal playing field AND NEVER WILL BE as long as we live in a profit based capitalist system.

Here it might be important to look at the history related to the FDA approval of the drug Vioxx (for arthritis and chronic pain) which was removed from the marketplace in 2004 due to dangerous side effects (or main effects) on the heart. It was determined that this drug probably caused anywhere between 88,000 to 139,000 heart attacks with 30 to 40 percent of those resulting in death. The pharmaceutical company Merck & Co., who produced this billion dollar blockbuster drug, was guilty of hiding valuable data that actually revealed the dangerous potential of heart damage, but continued to market and sell the drug.

Interestingly enough, in 2005 the FDA and Canada’s equivalent agency voted to allow this drug to once again be sold in the marketplace DESPITE these serious heart consequences. Merck has not pushed for this to happen because of the high number of lawsuits and settlements proving major harm done to high numbers of people.

However, it has been rumored that Vioxx may soon once again appear in the marketplace because both Merck & Co and the FDA may argue that its benefits outweigh any of the major risks involved in its use, and they may find a way around having to pay any more for legal damages.

AND it should be quite apparent that they, (Big Pharma and the other powerful medical institutions), have enormously powerful financial, legal, political, and advertising resources at their disposal. These institutional forms of power and control are clearly based in a profit based/capitalist system and are driven by a set of economic and political contigencies that we have virtually no control over.

All of these same institutional forces mentioned above, ultimately control and govern the entire course of how ALL psychiatric drugs are both viewed and dealt with by millions of people around the world. We cannot make fundamental change in how all forms of psychiatric abuse are addressed in society without confronting the very nature of the economic and political system we all live within.

It is clear that MIA and the entire worldwide backlash against the psychiatric drug “revolution” has a significant number of credentialed experts, along with a powerful number of credible published stories by psychiatric survivors, yet the number of drug prescriptions and psychiatric labeling increases by the day throughout the world. Incremental reform (while both noble and necessary) is NOT going to lead to any fundamental change when it comes to ending all forms of psychiatric abuse.

Just as with the enormous level of cognitive and political dissonance between Trump & Co. and those who oppose his rule, this System, can and will, tolerate vastly different narratives in the “marketplace” of ideas and regarding the sale of certain commodities, as long as it DOES NOT threaten the fundamental nature of a profit based system and those that rule it.

Richard

Report comment

You wrote “…harms of medications? Yes. Should the decision be left up to the patient in distress? No.”

Wrong.

You can not prove what ever chemicals, are medications, they are just drugs. You would have to prove a physical aberration to justify applying a physical solution.

A piece of rope controls someone the same a chemical that stops someone from movement/action or thinking of action and movement.

Otherwise authority can lock people up and wait to see if they start to get better, or communicate better. Whats the problem in the first place?

Report comment

Guidelines need to change so that no one ever is given these medications on a first episode basis. And for those who experience episodic distress, there needs to be a cost benefit analysis done not between the doctor and patient but by a medical board to decide what other therapies would be likely to help more.

I find it surprising that you would say this KS — why would you trust decisions by a medical board when there is no medical issue whatsoever (except possibly brain damage from neurotoxins)?

Report comment

Why oh why are we supposed to care about any drug trial that uses the HAM-D as a measure of depression. It’s beyond elephant in the room. It’s a rampaging Mastodon with rabies and I have yet to see it discussed as the main reason to disregard the clinical trials that use it.

CIpriani’s mega-analysis relied on it. Cipriano included studies in benzodiazepines were available to subjects who experienced insomnia, disclosing how many studies did that but not how many subjects participated in such studies.

The HAM-D has one question about mood and three or four about sleep. Of course people on bentos will see their sleep improve.

There’s even a question about anxiety, which is fine, I guess, but not if you gave subjects a benzo.

Here.

The HAM-D

(To be completed by a clinician based on a structured interview)

1.

Depressed Mood (sadness, hopeless, helpless, worthless)

0 Absent

1 These feeling states indicated only on questioning

2 These feeling states spontaneously reported verbally

3 Communicates feeling states nonverbally, i.e., through facial

expression, posture, voice and tendency to weep

4 Patient reports VIRTUALLY ONLY these feeling states in his

spontaneous verbal and nonverbal communication

Feelings of Guilt

0 Absent

1 Self-reproach, feels he has let people down

2 Ideas of guilt or rumination over past errors or sinful deeds

3 Present illness is a punishment. Delusions of guilt

4 Hears accusatory or denunciatory voices and/or experiences

threatening visual hallucinations

Suicide

0 Absent

1 Feels life is not worth living

2 Wishes he were dead or any thoughts of possible death to sel’

3 Suicide ideas or gesture

4 Attempts at suicide (any serious attempt rates 4)

Insomnia – Early

0 No difficulty falling asleep

1 Complains of occasional difficulty falling asleep i.e., more than an hour

2 Complains of nightly difficulty falling asleep

Insomnia – Middle

0 No difficulty

1 Patient complains of being restless and disturbed during the

night

2 Waking during the night — any getting out of bed rates 2

(except for purposes of voiding)

Insomnia – Lat

0 No difficulty

1 Waking in early hours of the morning but goes back to sleep

2 Unable to fall asleep again if gets out of bed

Work and Activities

0 No difficulty

1 Thoughts and feelings of incapacity, fatigue or weakness

related to activities; work or hobbies

2 Loss of interest in activity; hobbies or work — either directly

reported by patient, or indirect in listlessness, indecision and

vacillation (feels he has to push self to work or activities)

3 Decrease in actual time spent in activities or decrease in

productivity. In hospital, rate 3 if patient does not spend at

least three hours a day in activities (hospital job or hobbies)

exclusive of ward chores.

4 Stopped working because of present illness. In hospital, rate 1

if patient engages in no activities except ward chores, or if

patient fails to perform ward chores unassisted.

Retardation

(slowness of thought and speech; impaired ability to concentrate;

decreased motor activity)

0 Normal speech and thought

1 Slight retardation at interview

2 Obvious retardation at interview

3 Interview difficult

4 Complete stupor

9. Agitation

0 None

1 “Playing with” hand, hair, etc.

2 Hand-wringing, nail-biting, biting of lips

Anxiety – Psychic

0 No difficulty

1 Subjective tension and irritability

2 Worrying about minor matters

3 Apprehensive attitude apparent in face or speech

4 Fears expressed without questioning

Anxiety – Somatic

Absent Physiological concomitants of anxiety such as:

Mild Gastrointestinal – dry mouth, wind, indigestion,

Moderate diarrhea, cramps, belching

Severe Cardiovascular — palpitations, headaches

Incapacitating Respiratory – hyperventilation, sighing

Urinary frequency

Sweating

0 None

1 mild

2 moderate

3 severe

4 incapacitating

Somatic Symptoms – Gastrointestinal

0None

1 Loss of appetite but eating without staff encouragement. Heavy feelings in abdomen.

3 Difficulty eating without staff urging. Requests or requires

laxatives or medications for bowels or medication for G.l.

symptoms.

Somatic Symptoms – General

0 None

1 Heaviness in limbs, back or head, backaches, headache,

muscle aches, loss of energy and fatigability

2 Any clear-cut symptom rates

Genital Symptoms

0 Absent 0 Not ascertained

1 Mild Symptoms such as: loss of libido,

2 Severe menstrual disturbances

Hypochondriasis

0 Not present

1 Self-absorption (bodily)

2 Preoccupation with health

3 Frequent complaints, requests for help, etc.

4 Hypochondriacal delusions

Loss of Weight

A. When Rating by History:

0 No weight loss

1 Probable weight loss associated with present illness

2 Definite (according to patient) weight loss

B. On Weekly Ratings by Ward Psychiatrist, When Actual Changes are Measured:

0 Less than 1 lb. weight loss in week

1 Greater than 1 lb. weight loss in week

2 Greater than 2 lb. weight loss in week

17. Insight

0 Acknowledges being depressed and ill

1 Acknowledges illness but attributes cause to bad food,

climate, overwork, virus, need for rest, etc.

2 Denies being ill at all

Total Score:

Report comment

Those “somatic symptoms” could easily be caused by legitimate medical problems. But since you’re on a psych ward they’ll probably feed you neuroleptics/SSRIs/other crap instead! Then when your condition stays the same or worsens they’ll up your cocktail. Ugh.

Report comment

Why oh why are we supposed to care about any drug trial that uses the HAM-D as a measure of depression. It’s beyond elephant in the room. It’s a rampaging Mastodon with rabies and I have yet to see it discussed as the main reason to disregard the clinical trials that use it.

CIpriani’s mega-analysis relied on it.

Cipriani also included studies in which benzodiazepines were available to subjects who experienced insomnia, disclosing how many studies did that but not how many subjects participated in those studies.

The HAM-D has one question about mood and three or four about sleep. Of course people on benzos will see their sleep improve.

There’s even a question about anxiety, which is fine, I guess, but not if you give subjects antianxiety drugs (Not to mention the incredible harm that will come to some subjects once they’ve started on a benzo for sleep)..

Here.

The HAM-D

https://dcf.psychiatry.ufl.edu/files/2011/05/HAMILTON-DEPRESSION.pdf

Report comment

Great analysis! And despite these biases and limitations of the HAM-D, “antidepressants” STILL have difficulty reaching even a three-point improvement on the scale. Pseudoscience at its best!

Report comment

Thanks for trying to move attention away from the statistical significance framework, which is not helpful for patients. I agree that NNT is more informative, but NNT must always be related to specific outcomes, not to unspecific “improvement”. And number needed to harm (NNH) must be included in the benefit-harm equation. Each patient has his or her own weighting of every possible outcome, positive as well as negative. Some adverse effects are common, and others are extremely rare. Being exposed to the risk of adverse effects is not the same as experiencing these effects. We need more information about NNTs but perhaps even more about NNHs and how patients value their ratio.

Report comment

Such an important article, Bob! Thank you for writing this and making it so clear and compelling!

Report comment

Hi Dr. Paula. I loved your book, They Call You Crazy. The part that sticks out in my mind is when you compare diagnoses of “mental illness” to constellations rather than actual illnesses.

Report comment

Sorry to be so basic but…as it has been demonstrated that an entity such as “mental illness” is logically impossible according to the basic rules of language, why is so much “research” taking place on how to eliminate “it”?

Report comment

Just thinking about that fateful Cipriani antidepressant study, an NNT was never reported, but I think it might be in plain sight. Sorry this is a long post, but people here are pretty tolerant. Anyway, amongst both placebos and drug takers, 17% were responders. How you can call a placebo a responder beats me, but it’s there in the figures, the 17% who improved more than 50% are 20k cases out of 116k patients. Then, within that 17% the odds ratios varied, but most mainstream antidepressants had, by any favourable view, 1.7 times more drugs than placebos (eg Sertraline 1.67) . In other words, you were 1.7 times more likely to get better with the drug. Sounds great. But hang on, let’s try to get NNT, and I thank Robert for showing how this works. That 17% must be roundabout 6.3% placebo and 10.7% drug to arrive at a ratio of 1.7. Hmm, so a lot of placebos did get better, but if I really want to get better I should be with the 10.7% drug takers. But 6.3% of that 10.7% would have got better anyway! So actually, only 4.4% got better because of the drug, or an NNT of 1 in 23. That’s double what I had in my mind and it’s really poor. And yet this is the primary reason for recommending antidepressants, that they really help a number of patients – a very, very small number!

Report comment

Thank you for giving the relation of Cohens effect size and NNT.

I have tried to find out how many patients are medicated by neuroleptics (antipsychotics).

– Svedberg et al. 2001 reports 93% used neuroleptics and 75% ongoing (See: http://wkeim.bplaced.net/files/Open-Svedberg.gif )

– In Australia over 90% of people diagnosed with a psychotic illness are prescribed medication, and polypharmacy is common (Waterreus et al., 2012 http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0004867412450471 )

– Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis (TIPS) early-detection study medicated all in the beginning and approx 70% ongoing (Wenche ten Velden Hegelstad et al 2012: https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030459 )

– Open Dialogue Therapy in Western Lapland 33% use neuroleptics and 17% ongoing (See: http://wkeim.bplaced.net/files/Open-Svedberg.gif )

But only one in 6 patients get a symptom reduction og 50% or more according to Leucht et al. 2009.

Bjornestad, Jone et al. 2017 reported “Antipsychotic treatment: experiences of fully recovered service users”: “(b)etween 8,1 and 20% of service users with FEP achieve clinical recovery (Jaaskelainen et al., 2013)” under the profession’s current protocols.

Jaakko Seikkula et al 2010 (Journal Psychosis Volume 3, 2011 – Issue 3) has reported on long-term outcome of first-episode psychotic patients treated with Open Dialogue Therapy in Western Lapland approx. 80% recovery. “Showing the benefit of using not much medication supported by psychosocial care.” 19% were on disability allowance or sick leave with 17% ongoing neuroleptics. Sveberg (2001) reported 62% on disability allowance or sick leave following standard care and 75% ongoing neuroleptics. Disability allowance or sick leave goes up more then 40%. Open dialogue reduced the incidents of psychosis from 33 to 2 per 100 000 annually.

Is it possible to give a very rough guess on the long-term effect/harm of antipsychotics on recovery? http://wkeim.bplaced.net/files/question-recovery.html

Would between 2/3 and 80% be appropriate?

Report comment

Thank you for writing about patients who do not fall into the few who get reduction of symptoms.

Most of patients deteriorate

Levine et al 2012 ( https://www.schres-journal.com/article/S0920-9964(12)00039-4/pdf ) looked at treatment reactios for Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). Ca. 73% became drop-outs. «Trajectory analysis of the entire sample identified that 18.9% of participants belonged to a group of responders. This figure increased to 31.5% for completers, and fell to 14.5% for dropouts.» For 72,9 % of drop-outs PANNS symptoms increased from ca. 3% in the beginning to 35% after 18 months (see http://wkeim.bplaced.net/files/Levine-2012-drop_outs.png ). For 23,7% of completers PANNS symptoms increased from ca. 8% in the beginning to 30% after 18 months (see http://wkeim.bplaced.net/files/Levine-2012.png ).

Report comment