When persons holding the beliefs of modern western “psychiatry” advocate for and attempt to explain electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), formerly known as electroshock therapy, they usually say something like: “We don’t know how it works. We just know that it works.” This is completely understandable since those working in this field of medicine rarely have any training in electrical theory or safety, unlike those working with electrical injuries or those truly using electricity for therapeutic modalities, such as physiotherapists.

Persons working in the field of modern western “psychiatry” are likely to say the same thing about computers: “We don’t know how they work. We just know that they work.” Of course, if they did know how computers actually work, they would never suggest that ECT is like “rebooting the brain,” which is a very common analogy used in modern western “psychiatry.” The suggestion of rebooting a person’s brain the way a computer is rebooted would be horrifying to anyone familiar with computers and the rebooting process. One may be tempted to sarcastically respond to such suggestions and explanations with: “What operating system do you intend to load when you reboot my brain?” Or: “How long will it take to reload all the data into my brain that I’ve acquired throughout my life and where is this data saved while my brain is rebooting so that it can be reloaded?”

Those trained in electrical theory and computers, such as the author of this blog, who is a Certified Engineering Technologist (CET), would have to agree that the explanations of modern western “psychiatry” about ECT seem to confirm that they “don’t know how it works.” However, the use of the term electroconvulsive rather than electroshock seems to suggest that they understand more about how it works then they are now willing to openly admit.

The term “electroshock therapy,” despite the word shock also having relevance in the field of electrical injury, was incorrect because a pathophysiological state of shock was not the actual goal, but rather to induce a grand mal seizure with bilateral convulsive tonic and clonic muscle contractions. This is more evident in other so-called “shock therapies” that were really convulsive therapies, such as those that induced convulsions with pentetrazol or flurothyl. Thus, “electroconvulsive therapy” more correctly describes what is achieved with this treatment.

From the perspective of electrical injuries, the term “electroshock therapy” is also inaccurate because electric shock encompasses even small currents that would be imperceptible or produce only a light tingling sensation. Such electric shocks are normally harmless, though they could startle someone and inadvertently result in an injury by causing some other accident. If, however, an electric shock is strong enough to cause convulsions, it is well beyond the range of harmless and the convulsions themselves are evidence of an injury. Thus, the word electroconvulsive correctly implies that an electrical injury is the objective.

The combination of the word electroconvulsive with the word therapy does not seem to make much sense, except to perhaps evoke cognitive dissonance. Whether or not an electrical injury of the brain is therapeutic, however, will be addressed later on in this blog when the perspective changes from electrical science to an Orthodox understanding of the human psyche, which is beyond the realm of the empirical sciences.

E is for Electro

A scientific understanding of electricity’s effects on the human body has only been around since the last half of the 20th century. Charles F. Dalziel, a professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences at the University of California, Berkeley, was a pioneer in understanding electric shock and set the standards for understanding electrical injury. In addition to his book The Effects of Electric Shock on Man published in 1956 by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Safety and Fire Protection Branch, he also invented the ground-fault circuit interrupter (GFCI), known in the United Kingdom as the residual-current device (RCD), in 1961. While his groundbreaking work (if you will forgive the pun) has prevented many injuries and deaths, as with all science, our understanding of electricity and electrical injury has increased a great deal since then and continues to increase.

If this understanding of electric shock and electrical injury from the latter half of the 20th century was had in the first part of the 20th century, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) would likely never have been accepted by modern western medicine. Unfortunately, ECT was invented and accepted by modern western medicine before a scientific understanding of electricity’s effects on the human body had been established. Having ECT approved as safe by any responsible regulatory body would have been much more difficult after the publication of Professor Dalziel’s book, but ECT had already been accepted with widespread use by that time.

In 1902, Leduc of Nantes demonstrated the possibility of putting animals into a condition he called “electrical sleep” or “cerebral inhibition” by sending intermittent constant current through a part of the central nervous system. Zimmern and Dimier replicated Leduc’s study in 1903 with transcerebral currents and concluded that this “cerebral inhibition” was a post-epileptic coma. The first cases of surgery on animals with electroanesthesia were in 1907, but the early decades of electroanesthesia was always associated with muscle contractions, cerebral shock, cerebral hemorrhage, hyperthermia, cardiac arrhythmia, and convulsions. Due to these intense side effects, interest in electroanesthesia waned.

Frederic Batelli, a physiologist in Geneva, was the first, in collaboration with Jean-Louis Prévost, to achieve defibrillation of the heart by electrostimulation. However, he also documented being able to induce convulsions through electrostimulation of the brain. He assumed this was harmless, even though his experiments in inducing ventricular fibrillation with less electricity were obviously fatal if defibrillation with larger currents of electricity was not achieved.

It was this work of Batelli that led Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini to use electricity in 1938 to induce a convulsion in a human. They assumed it was safe because Cerletti had witnessed pigs being anaesthetized using electric shock in a Roman slaughterhouse. If an animal was not immediately slaughtered, it would eventually recover consciousness and walk away, which assured Cerletti it was safe to use on humans. Apparently, he was not aware that electroanesthesia was not accepted for use in surgery due to the above-mentioned side effects, but such side effects were irrelevant if electroanesthesia was only used to make slaughtering an animal easier. Thus, ECT was invented and became popular without any real understanding of electric shock’s effects on the brain other than that an electric current that was usually fatal when applied to the heart was not fatal when applied to the brain.

Whether or not an electrical current through hand-to-hand contact caused ventricular fibrillation was the main concern outlined in Charles Dalziel’s 1956 book. The value given in that book for this concerning amount of electrical current was 50 milliamps. However, as little as 30 milliamps could potentially cause ventricular fibrillation and almost everyone who has done any automotive mechanics has experienced at least one electric shock in excess of 50 milliamps without experiencing ventricular fibrillation. Thus, the amount of electricity is not the only factor. Nonetheless, comparing the 50 milliamps cited by Charles Dalziel with the 500 to 900 milliamps cited in the specs of ECT machines, a person may have thought more than twice about whether it was safe or not.

Physiotherapists are trained in electrical theory and safety because they do use currents that could potentially be harmful. Nonetheless, the range of a typical TENS machine is 0 to 80 milliamps, with some machines providing outputs up to 100 milliamps. This is far less than the 500 to 900 milliamps of ECT machines, but physiotherapists are still taught not to use TENS directly on the spinal column or transcerebrally (i.e. through the head) for fear of possible adverse neurological damage.

High Voltage Pulsed Current (HVPC) is used to stimulate wound healing, pain relief, and to facilitated oedema resolution. Since it uses between 150 to 500 volts, it could be compared to ECT since ECT has a cutoff limit of 450 volts. However, HVPC uses pulses that are less than 200 microseconds while modern ECT uses pulses in excess of 250 or 300 microseconds, often as much as 1000 or 2000 microseconds. Thus, the current flow through tissue will average to a very low level in HVPC, while it will be much higher in ECT.

Even the electrical load delivered by a Taser is less than that delivered by ECT. However, the electrical theory needed to compare the load delivered by ECT to the load of a Taser appears confusing and complicated to the average person, just as the theory needed to compare ECT to HVPC and TENS will appear confusing and complicated to the average person. As well, such numbers do not necessarily have a direct correlation to the amount or type of damage done to a person. One thing is obviously certain about ECT, though: it causes convulsions.

C is for Convulsive

A person, whom we shall call “George” for the sake of anonymity, once had a series of ECT followed by a number of years of various drug trials. After tapering off all medications and terminating this treatment, he continued to intermittently suffer some strange symptoms, especially at night. He hoped that these symptoms would eventually resolve, but they continued to worsen over the years and for longer periods of time. It became so bad that he would sometimes need three or four hours to recover from a night’s sleep or even just a 20-minute nap, and this would go on for a few days at a time. He suspected that this was due to some of the various drugs he had been put on, but it was suggested to him that these might be nocturnal seizures due to the series of ECT he had years earlier.

He requested to see a neurologist and eventually was able to see one. By this time, he had become aware that the medical community is reluctant to investigate any possible negative side effects of so-called “psychiatry,” especially ECT. (Perhaps this may start to change after the recent lawsuit resulting in Somatics, LLC issuing a warning of “permanent brain damage” in its new risk disclosures of October 19, 2018.) He had heard of people losing opportunities for a proper medical evaluation, such as an EEG, after it had become known that they had previously had ECT.

Fortunately for George, he had previously worked in a field that involved electricity. As long as the neurologist never reviewed his medical history, he hoped that by mentioning something about his former job and that he’d sustained an electrical injury to the head, he would received a proper medical evaluation. This plan was successful and nocturnal seizures were ruled out; however, before being sent for his EEG, the neurologist said a couple of very revealing and affirming things to George.

After assuming that George had received an electrical injury in a work-related accident, the neurologist asked him if he convulsed. George was startled by this question and was surprised that it seemed to be the main question to determine the severity of the electrical injury. Obviously, George confirmed that he had convulsed, which seemed to impress upon the neurologist how seriously George had been injured.

He had also explained to the neurologist that at the time of his appointment, he was experiencing the above-mentioned symptoms on a nightly basis. The neurologist said that it was highly unlikely to be nocturnal seizures and than added, “If you were having nocturnal seizures on a nightly basis like that, you’d have an IQ of 60 and that obviously isn’t the case.”

Although there is a great deal that is unknown about epileptic seizures, neurologists and, presumably, all other healthcare workers are well aware that they are accompanied by brain damage and subsequent lowering of a person’s IQ.

A person, whom we shall call “Alice” for the sake of anonymity, received a series of ECT, after which she began to receive maintenance ECT every three weeks. Although different protocols have been and are used, a series of ECT usually consists of two to three treatments a week for three to six weeks. Once a person has initially recovered from a series of ECT, often a single ECT must be administered to renew the effects received from the series of ECT, which is then repeated once initial recovery is again achieved, which usually takes between two to four weeks. In Alice’s case, she received a series of eleven ECTs over the period of a month, which was followed by ECT every two weeks, then every four weeks, then becoming rather consistent at every three weeks.

After receiving maintenance ECT for four years, she followed a suggestion to try a different “psychiatrist” (please see our last post for an explanation of why the word “psychiatrist” is in quotes here). This new “psychiatrist” sent her for a neurological assessment to determine if she should continue ECT. It was this appointment with a neurologist that really began to open her husband’s eyes concerning ECT.

Alice explained to her husband that another lady who was receiving maintenance ECT at the same clinic had to stop ECT after a neurological assessment determined she had accumulated too much brain damage and could not risk any more with ECT. Alice’s husband found this quite disturbing, but he found it even more disturbing that his wife did not find this disturbing. She indicated that all of the patients receiving maintenance ECT were aware that they could also eventually accumulate too much brain damage and would have to discontinue ECT. They saw this as something undesirable because they would then have to rely solely on medications, which were less effective and produced worse side effects. This reasoning perplexed Alice’s husband because all of these patients were also on medications and discontinuing ECT did not seem to change their medication protocol to any great extent.

Alice told her husband that he should not repeat what she had told him because people would not understand. Her husband, however, began to understand very clearly that his wife was in a very abusive situation, as were all of the other patients. Alice passed the neurological assessment and continued ECT under her new “psychiatrist.” It took quite some time and a great deal of effort, but Alice’s husband eventually succeeded in stopping both Alice’s maintenance ECT and medication protocol. Alice had actually tapered off her last medication successfully a month before she even knew it. Her husband had continued the taper after she refused to continue it and for the last month, she had been taking empty capsules.

Three days after Alice had unknowingly discontinued her last medication, she had an appointment with her “psychiatrist.” Her “psychiatrist” openly admitted that he was confused as to why Alice was doing so much better. She had disconnected ECT more than six months earlier and, as far as Alice and her “psychiatrist” knew, was on a dose of medication that was below the “therapeutic threshold.” Alice’s “psychiatrist” was confused about why Alice continued to show improvement when she had effectively stopped all therapy, especially since she had not shown any real improvement in the years just prior to terminating “psychiatric” treatment.

Alice’s husband was confused about why someone who was intelligent enough to get through medical school seemed to lack any sense of rational thought or critical thinking. It was obvious to Alice’s husband: Alice was doing better because she had had six months of recovery from the traumatic brain injury caused by ECT and had stopped ingesting neurotoxins. Of course, the confusion experienced by Alice’s “psychiatrist” had nothing to do with a lack of intelligence, but with delusional convictions that suspend rational thought. Although there is evidence to suggest that at least some, if not many, in the field of modern western “psychiatry” are aware of what they are really doing.

In addition to using the example of rebooting a computer to explain ECT, so-called “mental health” practitioners also often compare the importance of taking “psychiatric” medications with how important insulin is for diabetics. The interesting thing about such a comparison is that so-called “antipsychotics” were originally called neuroleptics because they supposedly accomplished the same thing as epileptic seizures. However, insulin is important for diabetics to prevent them from going into diabetic shock and having seizures, which all healthcare workers know will cause neurological damage. Thus, these so-called “psychiatric” medications were specifically meant to cause what insulin for diabetics is meant to prevent: brain damage.

(As a side note: apparently some clinics are now screening diabetics for possible symptoms of bipolar disorder because statistics show that diabetes is often comorbid with bipolar disorder. The very bizarre thing about these statistics is that some bipolar medications are known to cause diabetes, which results in the statistics of bipolar disorder having a high comorbidity with diabetes.)

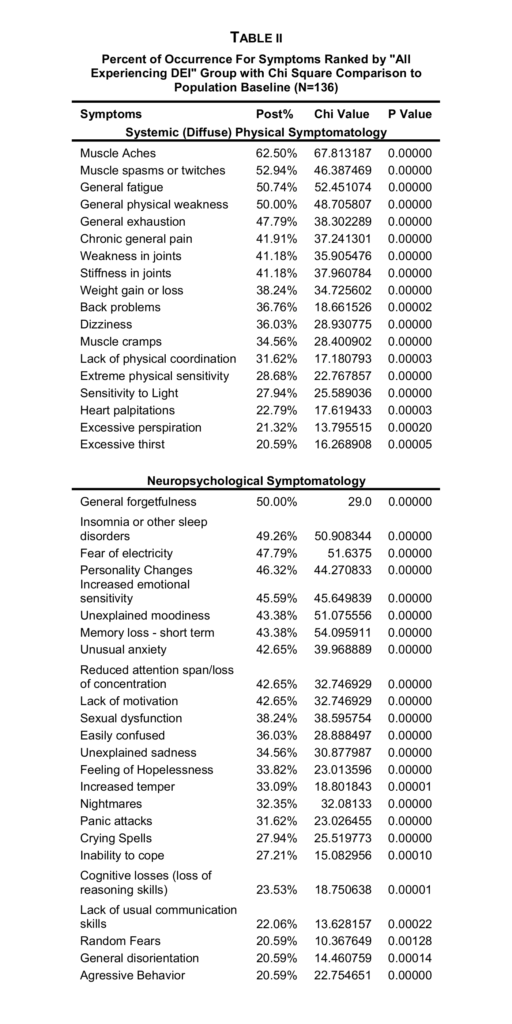

It is very strange that other fields of medicine attempt to prevent what modern western “psychiatry” specifically causes with its therapies, but do not acknowledge or treat the illnesses they cause (aside from things such as diabetes). Research and treatment of electrical injury, especially diffuse electrical injury (DEI), clearly contradicts the misinformation the medical establishment provides the general public concerning ECT. Acknowledged symptoms of electrical injuries, often from electrical currents smaller than those used in ECT and not with the head being in the direct path of the current, are almost always dismissed when they are a result of ECT. Many of the symptoms experienced by persons who have received ECT, but specifically denied by the medical community, are listed in this scientific study on diffuse electrical injury (DEI):

While the medical community seems to be very reluctant to acknowledge the obvious, perhaps an appeal should be made to the professionals in this field. The code of ethics of every professional association of engineers and technologists would prevent anyone from designing, manufacturing, and maintaining ECT machines without risking serious disciplinary actions. Nonetheless, for those not so technically inclined, simply the fact that enough brain damage is done by ECT to induce a convulsion should be sufficient evidence that ECT is not therapeutic, but abusive treatment causing bodily injury.

T is for Therapy

Jeffrey A. Lieberman has some very interesting things to say about the field of modern western “psychiatry” in his book Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry. In writing about when he was in medical school during the 1970s, he writes: “Back then, the majority of psychiatric institutions were clouded by ideology and dubious science, mired in a pseudemedical landscape where devotees of Sigmund Freud clung to every position of power.”

This bleak description of his profession in the 1970s is contrasted by his description of his profession in the 21st century: “For the first time in its long and notorious history, psychiatry can offer scientific, humane, and effective (sic) treatments to those suffering from mental illness. I became president of the American Psychiatric Association at a historic turning point in my profession. As I write this, psychiatry is finally taking its rightful place in the medical community after a long sojourn in the scientific wilderness. Buoyed by new research, new technologies, and new insights, psychiatry does not merely have the capacity to raise itself from the shadows but the obligation to stand up and show the world its revivifying light.”

If we overlook the overtly religious overtones, not to mention that the “historic turning point” he mentions was only in May of 2013, these statements from the introduction of his book clearly outline the theme: “…psychiatry progressed from a field that didn’t have really any scientific foundation to one which established a scientific basis…” (Lieberman’s own words while promoting his book). The history of ECT clearly demonstrates that ECT was developed and became popular without any scientific basis other than that it didn’t result in immediate death and that brain damage mutes the symptoms of mental illness.

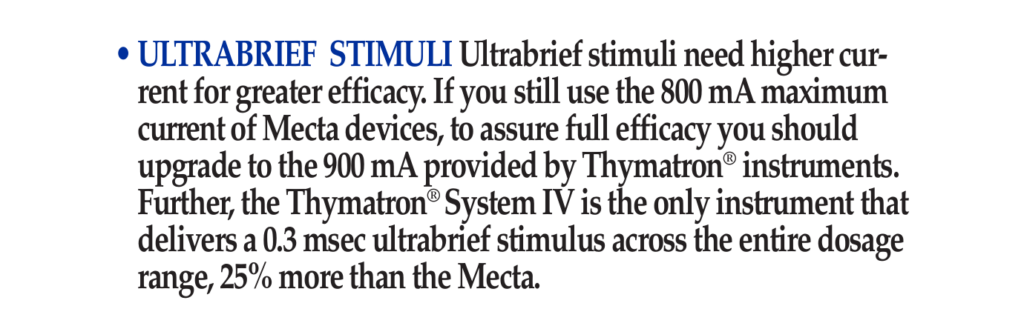

In his book, Lieberman does not discuss any of the actual science involved in ECT other than mentioning some of the additional protocols introduced to reduce the physical harm caused by the convulsions and the direct path of the electrical current. “[T]he strategic placement of the electrodes at specific locations on the head” determine which part of the brain receives the full load of the ECT machine and, therefore, the concentration of brain damage. However, his suggestion that “improved technologies enable ECT to be individually calibrated for each patient so that the absolute minimum amount of electrical current is used to induce a seizure” appears to contradict the sales literature from Somatics, LLC: “Ultrabrief stimuli need higher current for greater efficacy. If you still use the 800 mA maximum current of Mecta devices, to assure full efficacy you should upgrade to the 900 mA provided by Thymatron instruments.”

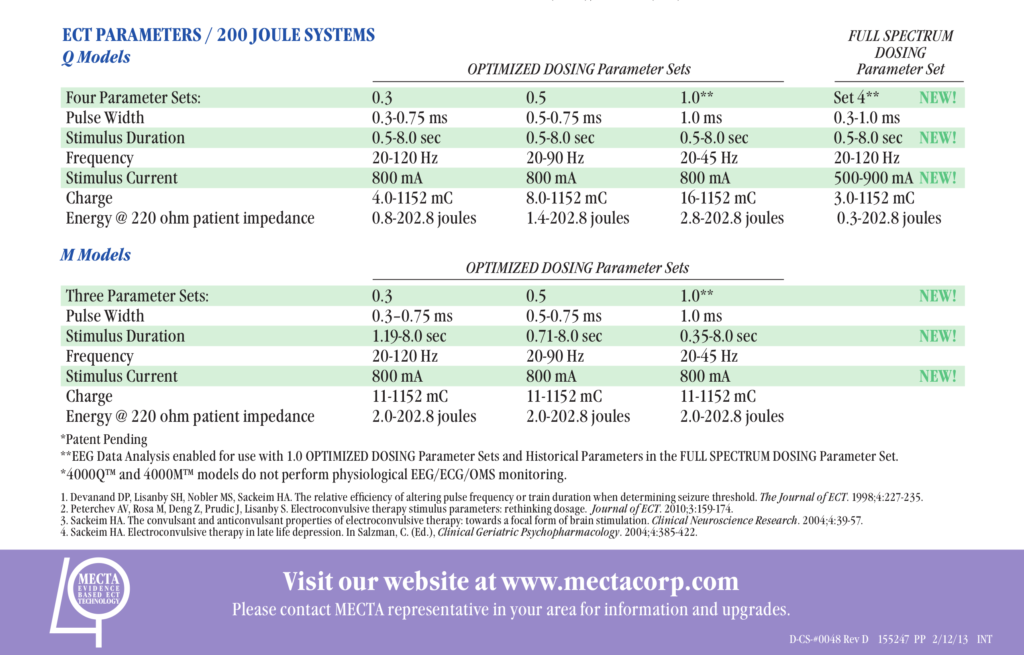

Among the various modifications to ECT that dealt with the problem that, as Lieberman notes, “the experience of delivering ECT can be quite disturbing” is the change from a sine-wave current to a pulse-wave current. Since the objective of ECT is to administer an electrical load that causes enough brain damage to induce a convulsion, changing from a sine-wave to a pulse-wave would require, as the sales literature from Somatics points out, a stronger electrical current. The shorter the pulse, the greater the current that would be needed to deliver a large enough load to trigger a convulsion. The most advantageous reason to use a pulse-wave rather than a sine-wave would be to suggest to an uneducated audience that a smaller electrical load is being delivered. Perhaps even an uneducated audience, however, would see that the 0.5 joules delivered into a load cited in research into TASER and Sudden In-Custody Death is obviously much lower than the 0.8-202.8 joules cited by Mecta in their international sales literature for “ultrabrief” ECT machines (this is twice the maxim of their machines sold in the USA).

Lieberman begins to conclude the segment of his book on ECT by saying that this invention of Cerletti and Bini “was the only early somatic treatment to become a therapeutic mainstay of psychiatry.” This statement may cause one to wonder how a somatic treatment can be, or at least appear to be, therapeutic for a psychic illness. Alice’s husband, who is mentioned above, witnessed a very clear example of this.

As Alice recovered from her maintenance ECTs, her husband would visit with another patient who would have maintenance ECT on the same day as Alice, only he seemed to recover from this treatment much faster than Alice and wanted to visit. Please note that we are only referring to recovering consciousness and being able to walk away, much like the animals Cerletti witnessed in a Roman slaughterhouse. We are not referring to the two to four weeks initial recovery from the resulting traumatic brain injury, after which another ECT is needed to renew the brain injury. For the sake of anonymity, we shall call this other patient “Gordon.”

Although Gordon was usually pretty happy after an ECT, sometimes he would express his great anger towards his brother whom he hadn’t seen in many years. Apparently, Gordon had bought a brand-new truck, which his brother then totaled in a car accident. Gordon would become so angry over this that he would talk about wanting to go to his brother’s place and beat him up. Alice’s husband would do what he could to change the subject to something less upsetting, which often didn’t take much effort.

When her husband began attempting to explain to Alice that the ECT was causing her brain damage and that she should stop, she attempted to defend the use of ECT by using Gordon as an example. She said that he already had a traumatic brain injury from a car accident, so it didn’t matter that ECT also caused a traumatic brain injury. This line of reasoning didn’t make any sense to her husband, but after he finally succeed in having Alice not go back for any more ECT, she revealed something else about Gordon. The car accident in which Gordon acquired a traumatic brain injury was the same accident in which Gordon’s brother totaled Gordon’s truck. Worse than that, Gordon’s brother was killed in that accident.

Gordon was not actually angry that his brother totaled his brand new truck. He was simply attempting to grieve the death of his brother. The psychic trauma Gordon suffered from being in the car accident that took his brother’s life was apparently being treated by sustaining a traumatic brain injury that prevented him from remembering or caring that his brother was killed. This may produce the empirical appearance of being therapeutic, but any unbiased and sane person should be able to see that this is a false appearance and that this so-called “therapy” is actually preventing any real healing.

After obtaining and reading Alice’s medical charts, her husband noticed that Alice’s extreme memory problems began when they switched from unilateral ECT to bilateral ECT. Thus, switching from concentrating the damage on only half of Alice’s frontal lobe to her entire frontal lobe resulted in a noticeable cognitive deficit that is consistent with research on head injuries. While the resulting convulsions would have appeared the same, the amount of brain volume directly damaged by the electrical load was much larger. This does suggest that a convulsion is not actually the goal of ECT, but the brain damage that induces the convulsion, even though the pseudomedical literature generally no longer admits this.

Before the introduction of “modified ECT” and modern western “psychiatry” starting to “offer scientific, humane, and effective (sic) treatments,” so-called “psychiatrists” openly speculated on how brain damage and a lower IQ was beneficial to persons suffering from psychic trauma. Since such speculation is no longer publicly acceptable, all they can say is, “We don’t know how it works. We only know that it works.”

ECT works by preventing the psyche from expressing itself through the soma, that is to say, ECT works by preventing the soul from expressing itself through the body. As quoted in our previous post, Fr. Theophanes (Constantine) explains this in Volume 1 of The Psychological Basis of Mental Prayer in the Heart:

“The soul functions through the body, and if the body is damaged, say in its higher brain centres, then the soul cannot express itself, without for all that having been lost.”

While Orthodox psychiatry has a great deal more to say on this subject and how modern western “psychiatry” actually attempts to prevent any true psychiatric healing, the above summary is sufficient for now. Even if one does not wish to explore the Orthodox perspective on this subject, any unbiased examination of the empirical evidence clearly demonstrates that ECT works by damaging the brain. The only issue for intelligent discussion is whether or not such brain damage is therapeutic, and the only rational question to ask is: how could an intelligent person believe brain damage is therapeutic? It is obviously not therapeutic and believing it is therapeutic is not a question of intelligence, but concerns the ability to think rationally.

The Orthodox believe that human intellect is fallen and corrupt, and that rational thought is only possible with Divine assistance. Perhaps only a little rational thought may allow one to realize that a “psychiatrist” who believes the psyche is actually somatic rather than psychic is only under the delusion of being a “psychiatrist.” It is often impossible to convince a person under a delusion that he or she is delusional. Such a person is more likely to suggest that the sane person is delusional. This is why our venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony of the Desert (251–356 CE) said: “A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him saying, ‘You are mad, you are not like us.’”

Curiously(?) enough, the only shock doc I ever knew wasn’t a psychiatrist by training, but an internist. He worked in a hospital in Michigan’s Oakland county, where, I believe he did them all. Unlike the above professional apologists, he mentioned, in a review of them, that he didn’t even curl his subjects’ toes. I knew him from when he was moving to a small town further north, where he hoped he could practice using therapeutic fasting, as described by Theron Randolph(MD) in the 1950’s. As he adjusted my B3 (why I went to see him), I suspect he also had his downstate patients on it as well, which would reduce the likelihood of serious memory loss. Unfortunately for him, the new hospital staff thought that controlled fasting was too dangerous a practice, an interesting observation on hospital medical thinking.

Report comment

If there is a thing in the world that can be called “brain rebooting”, then it is a psychosis.

I was talking to a man who was getting ECT, and he said that the people who invented this should be put in prison.

Report comment

I made this picture, influenced by psychiatry and how it treating people

https://imgur.com/IdBdMqG

Report comment

Father Anthony of the Desert was right, it will happen

Report comment

Awesome work, Russel!! This information is so important for people to understand. Unless you’re trained in electrical theory it’s hard for the average person to grasp what ” a small dose ” of electricity actually does to the brain does to the brain and body. It’s so easy for people to be convinced by psychiatry’s claims.

Distilling this info gives people some facts to counter their misinformation.

Thank you for writing this!

Report comment

Thank you for the work that you do and for hosting the above video on your YouTube channel.

Report comment

I thank you for providing this detailed, valuable blog Father John with your knowledge and training in electrical theory and safety. It is so disturbing to read about ECT especially knowing it is still being inflicted on people every day. I wonder if there are any future ECT protests coming up in Alberta?

Report comment

There was one in Edmonton and Calgary in 2015 and another one in Edmonton in 2016. Perhaps there will be more in the future, but none are planned.

Report comment

ECT is a lunatic assault on the sick and vulnerable. It must be banned.

I am left wondering about Alice. Did she get better? How much damage and memory loss did she have? How many ECT did she endure?

Report comment

Alice appreciates your concern and gave permission for me to say this. Her records show that she had a total of 101 ECT over a little less than six years. She does have major memory issues, but her family says she’s much brighter and more alive than when she was having ECT.

While having an eye example, the optometrist noticed that Alice displayed classic symptoms of a TBI. Assuming the most common reason for this, the optometrist asked her how bad the car accident was and if she had an MRI. Since the symptoms were obvious to the optometrist, Alice’s mother attempted to have the brain injury diagnosed so that they could access services. However, since they couldn’t point to any such accident and any harm from ECT is denied by the medical system, Alice was denied access to any medical assistance for the brain injury.

Report comment

Is there a possibility, now that Somatics has admitted to its machines causing perm amnesia and perm brn dmg, with the judge’s ruling in CA, that Alice’s family, with the help of an attorney, could challenge her right to rehabilitation for brn injury?

Report comment

The closest legal precedence in Alberta, Canada, which is where Alice lives and received ECT, is the law suit filed by Leilani Muir who was involuntary sterilization in 1959 under the Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta. The Sexual Sterilization Act and the Alberta Eugenics Board were repealed and disbanded in 1972, but Leilani Muir’s case did not go to full trial until 1995. Since then, over 850 victims have filed lawsuits against the Alberta government, most of which have been settled out of court.

The Canadian National Committee on Mental Hygiene (CNCMH) played a major role in establishing the Alberta Eugenics Board and continues to exist today, though they’ve changed their name to Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). Despite the name change, their underlying philosophy has remained the same, which is the same materialistic philosophy underlying modern western “psychiatry.” A number of the parks and neighbourhoods in the capital of Alberta are named after political leaders who were instrumental in establishing the Alberta Eugenics Board, such as Emily Murphy, Louise McKinney, and Nellie McClung. Eugenics and its degrading philosophy that forms the basis of modern western “psychiatry” are a major part of the history and culture of Alberta. Thus, Alberta would likely be the last place in Canada where ECT victims receive any compensation or recognition and that would only be after ECT is banned.

Additionally, those who receive ECT have to sign a consent form, which avoids the appearances of being involuntary. Alice was very clearly coerced into ECT by a doctor who was “caring” for her while her doctor was on holidays. Alice’s husband was very against it, but there was nothing he could do, especially after Alice reluctantly signed the consent form. It is quite unlikely that Alice will receive any real care in this regard except for the care of her husband.

As well, it appears it was a Mecta ECT machine that was used on Alice, not a Somatics machine, so that would likely be distorted into being somehow relevant.

Report comment

“It is often impossible to convince a person under a delusion that he or she is delusional. Such a person is more likely to suggest that the sane person is delusional. This is why our venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony of the Desert (251–356 CE) said: ‘A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him saying, ‘You are mad, you are not like us.’’”

I do agree, this is where today’s DSM believing “mental health” workers are. They want to murder and steal from everyone who doesn’t believe in, or even know about, their “invalid,” “unreliable,” and insane DSM “bible.” Today’s DSM deluded are quite similar to the psychiatrists in Bolshevik led Russia and Nazi Germany. And thus we are seeing our very own, on going, banned from the mainstream media, psychiatric “holocaust” in America today.

https://www.naturalnews.com/049860_psych_drugs_medical_holocaust_Big_Pharma.html

“The soul functions through the body, and if the body is damaged, say in its higher brain centres, then the soul cannot express itself, without for all that having been lost.”

As one of the many who was drugged up for belief in the Holy Spirit, God, and belief in the real Bible, by today’s psychiatric establishment for a former pastor, I absolutely agree the soul functions through the body. And the psych drugs do change how one expresses oneself. But I will say, as an artist, I now have a portfolio of artwork, of which my child rape covering up childhood religion is terrified, because it’s “too truthful.”

https://books.google.com/books?id=xI01AlxH1uAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://virtueonline.org/lutherans-elca-texas-catastrophe-coming-lesson-episcopalians

So I would say the psych drugs do hinder the way a soul expresses itself (chaos in the brain = chaos on the canvas), but do not prevent a soul from expressing the crimes committed against one’s family, especially once one is weaned off those drugs. I, thankfully, never experienced ECT, so can not speak to the horrors of that personally.

An ethical pastor did confess to me, once given a medical synopsis of the crimes committed against my family, to the “dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” Did the Orthodox not make this child rape covering up faustian deal with the psychiatrists? Or did you learn from buying into it in Russia, and are now speaking out against it?

The primary actual function of the “mental health” workers, both historically and today, has always been the paternalistic job of covering up rape of children for the Christian religions, and the wealthy they worship.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

The problem is, the wrong banksters took over the world, including America. And in my case, my childhood religion now worships Bohemian Grove attending, Baal worshipping, “cocaine dealing,” child sacrificing, wealthy pedophiles. And this seems to be a systemic problem, even according to world leaders.

https://globalfreedommovement.org/putin-blasts-euro-western-culture-of-pedophilia-and-satanism/

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/us/backpage-sex-trafficking.html

Report comment

I am not Russian. I am Canadian. My family history is a mix of Lithuanian (hence the family name), German (from Slavic lands, likely having gone there under Catherine the Great), English, and Belgian. I converted to Orthodoxy in large part due to a bishop from Ukraine and a monk from a Greek monastery on Mount Athos, both with whom I became antiquated from visiting a Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Nonetheless, my path to Orthodoxy had begun since childhood.

When it come to politics, I prefer to simply quote St. Maxim Sandovich: “My only politics is the Gospel.”

The above mentioned monk from a Greek monastery on Mount Athos was the author of ‘The Psychological Basis of Mental Prayer in the Heart.’ I have one of the few printed copies (given to me by the author’s brother after the repose of the author) and hopefully it will be published once his estate has been settled. Until then, the Athonite monk left it online for the whole world to read because worldly gain is of no importance to a truly Orthodox monk nor to any real psychiatrist (physician of souls):

http://timiosprodromos4.blogspot.com/

Report comment

Father John has done a nice job here of revealing the stupidity the drives, as he refers to it, “modern western psychiatry”. Thank you for this.

I can do the same thing for people that shock does by taking a baseball bat and smacking them a couple of times in the back of their heads. Of course people sit quietly with smiles on their faces after being given a shock “treatment”, they now have a nice, big brain injury. They have a traumatic brain injury, more commonly referred to as a TBI!

Report comment

While between 0.5 to 0.9 amps is used for ECT, captive bolt stunners for sheep use 1 amp, 1.25 amps for pigs, and 1.5 amps for cattle. Captive bolt stunning animals prior to slaughter is the technology from which ECT evolved.

http://www.grandin.com/humane/elec.stun.html

Report comment

Electro-shock de-mystified. We need more articles like this one that present the facts because one thing is for sure, from the system we’re getting a pack of lies. What amounts to injury elsewhere in the medical profession is seen as a miraculously curative “therapy” in psychiatric treatment. Go figure. I would imagine that the half-truths such as are used to promote ECT must actually, in the final analysis, be somewhat less than half-truths. Perhaps one could call them quarter-truths, or tenth-truths. Shock is neither so “safe” nor “effective” as it is billed, in fact, what it is is dangerous and debilitating.

Report comment

Thanks so much for this very logical explanation. None of these things are an opinion, they are facts. We can choose to refuse to believe the facts, or misinterpret them, as most, in fact, will do. We can choose to remember only what we want to remember. In the case of ECT survivors, often we cannot remember.

I am going to share this article with a relative who is a physicist. Much thanks for this!

Julie

Report comment

What an amazing and horrifying article. Several years ago, I seriously considered ECT. The drugs certainly never worked and I was desperate. Thankfully, some small part of my soul spoke against it and I had the sense to listen.

Report comment

Thanks, excellent article.

Just for variety, maybe MIA could publish something by an electrician; they not only understand electricity but generally have experienced some pretty decent shocks as well. Maybe an electrician with a degree in psychology would be the ticket.

Report comment

Just before the ECT protest in 2015, I happened to meet an old friend who was an electrician. He had been in a major work related accident since I last saw him and displayed a number of symptoms common to persons who have had ECT. Electricians, electrical engineers, even an auto mechanic would be able to dispel the misinformation propagated by the medical industry about ECT. This isn’t rocket science. It’s just basic electrical theory and safety.

Report comment

My point exactly, glad you agree.

Report comment

And why should the person have a degree in psychology? We need more clergy writing in as this is an underrepresented population on MIA. We need more scientists from other sciences as well. The discussion in the article is about electricity. What does a psychologist know anything at all about electricity’s effect on the brain? If your loved one has been through ECT you know better than anyone else the effect of ECT on a person’s life, regardless of your profession. I agree with the author that those who have been through ECT may not immediately be aware of the damage. My boyfriend did not have a college degree and he had majored in business. He understood more than any of those idiots at the mental hospital that the ECT was damaging to me. I was even seeing an esteemed psychologist for “therapy.” She was totally uninterested in me and even nodded off during our sessions. She was one of the most clueless individuals involved in the whole fiasco. Since when are psychologists the experts on life? I really hope you reconsider your position, Oldhead. You know better than that!

Report comment

Lighten up Julie, I was being facetious. 🙂

Report comment

How about an electrician with a degree in neurology?

Report comment

This isn’t rocket science. It’s just basic electrical theory and safety.

With conductive gel (“A little dab’ll do ya”), the impedance of the head must be brought to below 1500 ohms. A current of 800 milliamps (though, for “greater efficacy,” 900 milliamps should be used) would need a potential difference of 1200 volts, which is why ECT machines have a cutoff at 450 volts to avoid the smell of burning flesh. Once the current begins flowing, however, dielectric breakdown lowers the impedance of the head to lower than 300 ohms, which would only need less than a potential difference of 240 volts (the suggestion from ECT manufactures is 280 ohms, which would need 224 volts).

Under normal conditions, dielectric breakdown of the skin occurs above 450–600 volts, which is likely why a cutoff of 450 volts was chosen for ECT machines, which are not used under normal conditions.

Beyond this, a pulse-wave current makes the math more complicated. However, the fact that the impedance of the head goes from between 1400 and 1500 ohms to below 300 ohms and a convulsion results is more than enough evidence of a serious electrical injury… an electroconvulsive injury.

Report comment

Father John, you are totally awesome and I thank you a bunch for all you have done for us.

Human behavior also is not rocket science. Anyone can have insight into it, including prisoners, janitors, cafeteria workers, students, and anyone who has contact with other humans. Children have amazing insight. There’s no need for a degree to understand lying, dishonesty, and corruption, and to recognize when a worker for the oppressors is breaking the rules, risking their jobs, and actually being kind. There were a few, but most said nothing and complied.

Report comment

I must add a correction to the above comment. The cutoff for Somatics is 450 volts, while the cutoff for Mecta is 460 volts.

Report comment

Thank You for pointing out that ECT is essentially “Man’s Inhumanity to Man”..

G-d bless you!

Report comment

One of the most heartbreaking cases I ever worked on was a young man or woman receiving ECT because of a suicidal gesture– e.g., actions that fall short of a suicide attempt, such as putting an unloaded gun to your head, putting a strip of masking tape around your neck like a noose, or wrapping a cable around your neck and tightening it briefly– when one has suicidal thoughts.

This individual reported extreme memory loss, headaches, and many other symptoms that suggested some form of brain damage– blank stare at times, though moments of humor and laughter seeped through. He/she never had a chance to process the trauma that brought this about, which was the loss of a pet for which the patient felt responsible.

I contacted the psychiatrist in charge of the case, tried to get him or her to budge on anything– stopping ECT, fewer treatments, titrate down on one of the 4 psych meds he/she was on. Very pleasant psychiatrist, very concerned, but did not change treatment in any way.

I was trying to figure out if there was some asymmetrical tactic I could use to get her to a more responsible provider when he/she had a car accident on the way to session– and it was a completely avoidable accident, a U or left turn where patient could have avoided injury just by looking both ways. I reported it to the psychiatrist, but patient had to leave town for economic reasons, and I couldn’t help thinking: Did they pick on this patient b/c he/she did not have resources to resist? What other reason could there be? They had this machine, I guess, and needed someone to use it on, or that was what I speculated, so they chose someone helpless.

Of course, the patient was never well organized enough to make it to session after that, and moved back home with his/her relatives out of state.

I am trying to put together a better tactical plan for dealing with something like this if it ever comes up in the future. I still feel terrible guilt about not being able to help him/her, or advocate effectively, even though the “treatment” was near completed by the time he/she was referred to me.

Report comment

As best as I can figure out from looking through my old paperwork I had a few hundred ECT’s over a period of 15 years. I finally stopped agreeing to having them 10 years ago, and really felt like I had hit a new level of rock bottom a couple of months later. That miserable experience triggered a profound spiritual healing in me…

I still struggle daily with the damage of ECT, permanent memory loss and feelings of emotional detachment. At times I still indulge in getting really angry at the doctors who harmed me, and even shake my fist at God and give him a piece of my mind, but I’ve made a personal decision to do as much good as I can in the time I have left. Hang in there ECT survivors !!!

Report comment

Depersonalization and derealization are common symptoms of traumatic brain injuries and very common with ECT. I am sorry for what happened to you. Your personal decision to do as much good as you can will allow more healing, possibly leading to the anger going away. Being able to “love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you,” results in the healing of one’s self, if not also the other. As St. Seraphim of Sarov said: “Acquire a peaceful spirit, and around you thousands will be saved.”

Report comment