Sir Robin Murray, a distinguished British professor of psychiatry, recently published a paper in Schizophrenia Bulletin titled, “Mistakes I Have Made in My Research Career.” He describes the evolution of his thinking regarding the concept of schizophrenia, including the problems with the neurodevelopmental model, the limitations of the drugs used to treat the condition, and his failure to pay adequate attention to the role of social factors in the etiology of psychotic states. These ideas are not new to anyone who has read Anatomy of an Epidemic. Sir Robin’s ’s paper could be read as a synopsis of Chapter 6, “A Paradox Revealed.”

When a commentary on this paper was published on Mad In America, it garnered significant attention (over 100 comments in its first week). I, too, was fascinated. What for me was most striking was captured in the title. It harkens back to the book by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson, “Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)”. That book was about the concept of cognitive dissonance and its role in making errors in our thinking difficult to acknowledge. But notice the difference in titles. Professor Murray did not distance himself from error. He could have called his paper, “Mistakes Psychiatry Made.” Instead, he titled it, “Mistakes I Have Made” (italics mine). Kudos to him. In his paper and his comment on MIA, he distinguishes himself as a gracious man.

I perceived his paper to be a self-reflection rather than an indictment of psychiatry. It is an example of the impact of cognitive dissonance and the various biases to which we are all susceptible. When Murray writes about his belated acknowledgement of the role of social factors in the etiology of psychosis, he states, “The truth was that my preconceptions [regarding the neurodevelopmental model] had made me blind to the influence of the social environment.”

One type of bias is known as confirmation bias. This is the tendency to pay more attention to information that supports one’s opinion and discount or ignore data that contradict it. According to a leader in this field, Daniel Kahneman, these tendencies are not a reflection of limited intelligence or moral failing but are a core component of human cognition. (Kahneman’s work is summarized in his outstanding book, Thinking, Fast and Slow.) We have an amazing ability to make rapid inferences that are often correct. But this comes at a cost and carries risk.

In the history of science and medicine, there have been repeated instances of highly valued theories elevated prematurely to accepted doctrine only to give way to new ideas and theories. Every young medical student has the experience of thinking smugly about discredited ideas once highly revered that now seem, in retrospect, quaint. We value science and logic and believe they will protect us from the same fate. But time marches on and it is a rare medical or scientific career that is untouched by the experience of having to give up an idea once “known” to be valid.

Ideas may give way under the weight of new data; the scientific process continues to hold its value. But it is not impervious — sometimes over decades — to error. Although we might conclude our careers with our mostly deeply held beliefs intact, who knows what our successors will retain and discard?

I wonder what leads Robin Murray to acknowledge his mistakes when others seem to hunker down. I also wonder how I can know when I am misled in my assumptions. I have changed my mind multiple times in my career. I do not know if my current ideas are any truer than earlier ones. I had a conversation recently with a colleague in which I was articulating these thoughts about Professor Murray’s essay and she responded that my confirmation bias had led me to draw faulty, negative conclusions about the usefulness of antipsychotic drugs. We were at an impasse. If we all have confirmation bias, how do we decide who is correct? How do we know what is true?

In recent years, as my own conclusions have diverged from those of so many of my colleagues, I often find myself caught up in an inner dialogue about knowledge and truth. Peter Zachar’s book, A Metaphysics of Psychopathology, has been another important resource for me. It concludes with a philosophical examination of psychiatric nosology that is preceded by a careful examination of epistemology — how do we determine what is true, who has the authority to judge truth? I think of it as a philosophical companion to Kahnemann’s book. Zachar discusses the radical empiricists’ notion of the coherence theory of truth. He writes that “new propositions that seem to readily cohere with what we already believe are going to be accepted more easily than propositions that contradict currently accepted knowledge.” This makes it hard to shift in a more discordant — radical — direction.

At the same time, philosophical modernism led us to question authority, or at least acknowledge that authorities can be wrong. Zachar writes about literalism — a philosophical stance that is often associated with fundamentalist interpretations of the Bible but can be found elsewhere. One literalist assumption, according to Zachar, is that “It is important to discern which ‘experts’ should be granted epistemic authority.” We live in a world that is so complex; in many areas, none of us can ever know all of the available evidence. So while we may value our ability to think for ourselves and form our own conclusions, we still rely on authorities. I believe in the reality of climate change not out of a deep understanding of climatology but mostly because I have decided which experts I will trust.

I am preoccupied with “truth” claims in one very narrow area of our universe — namely, what is the best way to think about the antipsychotic drugs. I have decided that Joanna Moncrieff’s drug-centered model is most useful because it helps me to consider these drugs not as a specific treatment for a specific disorder but as psychoactive drugs that may have some benefits for some people at some times. This strikes me as a paradigm that is more consistent with the available data on the subject. The Krapelinian concept of schizophrenia has not held up well over the century since it was posited. There is no unified theory of etiology or pathogenesis, its genetic risk factors are multiple and variable from one individual to the next, and there are vastly different outcomes for those assigned the diagnosis. It is at best a category that entails considerable heterogeneity.

The drugs classified as “antipsychotic” are similarly varied in their actions in the brain. In recent years, their proposed targets have broadened. The idea that antipsychotic drugs treat a specific pathological process inherent to all who merit the diagnosis of schizophrenia simply makes no sense. And yet these compounds seem fairly consistently to reduce the intensity of voices and lessen the intrusiveness of unusual thoughts. The notion that their impact results from their inducing a state of cognitive indifference, as Laborit observed so many years ago, seems to explain why they can be helpful in some circumstances. The cognitive indifference reduces the intrusion and intensity of voices. That is consistent with what people tell me when they take the drugs.

At the same time, it makes sense that this same effect might contribute to the negative impact on functional outcomes when people take them over years. Their drive to get out of bed, engage with people, and find jobs may be diminished by the effects of the drugs. It also makes sense that the drugs might have this impact on anyone who takes them, regardless of diagnosis. That is to say, it is likely better conceived as a drug effect and not a disease-specific effect. This does not lead me to a conclusion that they should never be prescribed but it leads me to be more cautious in their administration.

My views overlap considerably with Professor Murray but they also diverge. For instance, I do not accept that “there is no doubt that antipsychotics are necessary in acute active psychosis,” although I often find them to be helpful in that setting. What is remarkable is that while my views are shared by other colleagues, I find it hard to find anyone with whom my perspective overlaps fully. This seems to be less a reflection of my “rightness” or their “wrongness” but of the complexity of the evidence and the question at hand.

If I understand Kahnemann, his antidote to cognitive bias is to slow down and do the hard work of thinking through problems. I wish I could borrow his supple mind. While I like to think of myself as deriving my conclusions through careful research and reason, I am also told — repeatedly — that I am passionate and some have suggested my passion clouds my reason. I like to think my passion drives me to reasoned inquiry, but who knows?

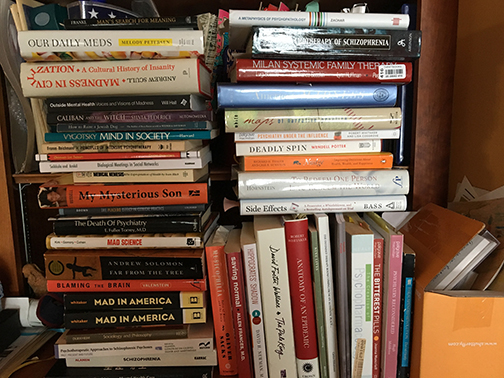

The photo shown here — of the many books I have read in recent years — at least speaks to my attempt at reasoned inquiry.

Thank you, Professor Murray. I would much rather engage critically with accepted dogma at the risk of making mistakes than sit back and accept what the reigning authorities assure me is true.

* * * * *

This blog is dedicated to Mickey Nardo, MD, a psychiatrist and blogger who embodies careful thinking and a deep humanity. His blog, 1boringoldman.com, has done the heavy lifting of careful analysis of drug studies that has been sorely missing in other quarters. He has taught me and many others and I look forward to reading more of his blogs in the months and years to come.

The reality of the “schizophrenia” diagnosis, according to the medical evidence, seems to be that the majority of those diagnosed as “schizophrenics” are child abuse victims. And the reality is that when you give a victim of a crime, as opposed to a person with an actual brain disease, an antipsychotic drug, the neuroleptic drug can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. Or the neuroleptic drug can create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” and actually make the person psychotic, via anticholinergic toxidrome.

I am unaware of great controversy over these syndrome/toxidrome, but the “schizophrenia” diagnosis has been confessed to be scientifically “invalid” by the head of the National Institute of Mental Health, as have been all the DSM disorders. The truth of the matter is the DSM is a classification system of the iatrogenic, not “genetic,” illnesses created with the psychiatric drugs, and the medicalization of all human attributes. None of the DSM disorders are real diseases, and the psychiatric drugs are “torture” drugs, primarily used to silence child abuse victims given that, “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).”

I will also mention it was confessed to me by an ethical pastor that “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions” is that the psychological and psychiatric professions have been in the business of covering up the “zipper troubles” of the mainstream religions, and the easily recognized iatrogenesis of the incompetent doctors, for profit and for decades.

And it has come out, via Wiki leaks and on the internet, that the current self proclaimed “elite” of the US and Europe have pedophilia problems, which would explain why these so called “experts” / higher education financiers are advocates of the DSM and it’s theorized disorders. But I do not believe this adds credibility to their claims of being “experts.”

I politely request that the medical community and their religious hospitals get out of the business of profiteering off of turning child abuse victims into “schizophrenics” and “bipolar” and “borderline” patients, with the psychiatric drugs.

Report comment

“I wonder what leads Robin Murray to acknowledge his mistakes when others seem to hunker down.”

Well Sandra, as Upton Sinclair said in the early 20th century, “It is difficult to get a man to understand that ‘schizophrenia’ is not an illness and that antipsychotic tranquilizers are not ‘medications’, when his salary depends upon his not understanding these facts.”

Or is that a misquote? I’m joking… but perhaps once they come to the end of their career, it becomes a bit easier to acknowledge mistakes.

From an outsider perspective like mine, it seems obvious that it would be much easier to admit one’s mistakes once one’s living has been made and one’s retirement has been funded, as in Murray’s case (given that he’s in his mid 70s). It’s still good of him to admit to mistakes, but less impressive – and perhaps from another perspective less foolish and risky – than for a younger man. In his case, speaking out involves primarily humility, which is a good thing, but not risk. But for younger psychiatrists, speaking out could involve being unable to pay their mortgage, not being able to send their kids to school, not being able to fund their retirement, etc… who would take those risks?

Regarding this, “The idea that antipsychotic drugs treat a specific pathological process inherent to all who merit the diagnosis of schizophrenia simply makes no sense. And yet these compounds seem fairly consistently to reduce the intensity of voices and lessen the intrusiveness of unusual thoughts.”

This is where I think it would be helpful to simply name most of these compounds as tranquilizers or deadeners. People will not do that, perhaps because they don’t want to face the reality that we are silencing our fellow humans en masse by loading them up with numbing agents that block their ability to think and feel… treating them, in some cases, almost like non-human animals or cattle. It’s not a very attractive picture. The euphemism that we are giving them “medications for schizophrenia” protects the self-esteem of professionals and prevents us from facing how inadequately such people are really being treated.

More broadly, the need to frame antipsychotic drugs as “medications” treating an specific disease process, and the need to overfocus on biology, must be traced directly back to the profit motive for both psychiatrists and their benefactors, the drug companies. I discussed these factors in my essay last year:

“This bio-genetic focus is understandable when one considers that primarily bio-genetic explanations of psychosis have numerous “advantages” for the psychiatric profession, in that they:

1) Support the illusion that psychiatrists are treating well-defined brain diseases in their privileged role as medical doctors;

2) Justify the use of tranquilizers, euphemistically named “medications,” to treat the supposed illness;

3) Protect psychiatrists and allied mental health workers from having to get to know psychotic people intimately as individuals, a process which often involves encountering uncomfortably large amounts of confusion, terror, rage, and despair;

4) Allow for shorter sessions and more profit per hour worked – it is much easier and more lucrative to give someone a pill after a 15-minute evaluation, than to sit and talk to them for an hour;

5) Allegedly protect parents from being “blamed” for contributing to their child’s psychosis despite the fact that biological models actually encourage prognostic pessimism, and obscure the obviously uncomfortable fact that not all, but many parents of psychotic individuals have abused and neglected their children, as pointed to by the studies connecting trauma and psychosis”

Lastly, Sandra, you might be interested to check out how George Soros picked stocks in his early career. He studied the thinking processes you describe and tried to interrupt his own processes of easily assuming which stocks were best by reading many contrary views – i.e. constantly challenging himself by reading both the supporters and critics of ideas about different companies. In this way he stopped himself from becoming too enchanted with any one view. I read about this in an interview, but I don’t have the link.

Another good book on a related subject is Future Babble, in which cautious thinkers who think along ranges or continuums are more accurate in making predictions than more certain thinkers who try to make precise prognostications.

Report comment

Matt and Sandra

Sandra, I appreciate your blog and the issues you are willing to critically explore, including your own biases and the related moral issues regarding the role of psychiatry.

When you say: “…to all who merit the diagnosis of schizophrenia…”

I believe you are still perpetuating the worst of Psychiatry’s harm through it’s use of oppressive labels and the resulting horrible treatment that flows from their use. By not challenging the very existence of this particular label (among many that fill the DSM Bible), especially by using quotations, are you not succumbing to the very historical biases you are now questioning?

Matt, I agree with all of your above points but would add this MOST IMPORTANT point to the list. The “bio-genetic focus” you refer to has an especially important role within an oppressive status quo (a profit based Capitalist/Imperialist society) of shifting the focus AWAY from people examining what is inherently wrong with the political and economic structures within our society. Instead it shifts the focus to people blaming society’s harms on “genetic theories of original sin” or so-called inherent flaws in human nature. How convenient his becomes for the ruling classes to be able to maintain their power and control over the broad masses of people.

Richard

Report comment

Hi Richard,

Thank you for your comments. I thought I was clear in this paragraph preceding this statement that I was challenging the legitimacy of that category “schizophrenia.” By “merit the diagnosi” I was just referring to people who reported the symptoms which in our current nomenclature would lead to this label. It was not intended as a endorsement of the category. I am not sure how to critique a position without describing it.

Report comment

Yes Sandra, I urge you to reconsider the language, “those who merit the diagnosis of schizophrenia”.

Nobody merits or deserves such an invalid, outmoded, harmful, misleading label.

Try “receive”.

Report comment

The problem is that that the word “merit” makes it sounds as if the word “schizophrenia” is something that people deserve or earn… almost as if the label schizophrenia were valid or accurate, and as if such a label was worthwhile. In reality, two people can “merit” this label while having no experiences in common. It is largely arbitrary and subjective. Not to mention extremely harmful given the assumptions attached to this outdated word.

These labels are just so problematic.

Report comment

Fair point. Thanks.

Report comment

Dr. Steingard, understandably, the nit-picking of every word that you write on this platform (even if your intentions were something else when using certain words) can become draining (I found this to be the case for myself on another topic here). There is a reason why we nit-pick them or re-frame sentences. It’s because we have seen where the thought process of thinking that way goes.

Hopefully, these tendencies amongst us will not discourage you too much from making positive contributions here.

Report comment

I think I get it. I have changed my word use after considering comments. I use “drug” instead of “medication” because of comments on my blogs. Nit pick away!

Report comment

@Matt: “Receive” is a passive acceptance…. Try: “are given the label”…. Nobody ever “receives” a psychiatric diagnosis. They are GIVEN. It’s the difference between “active voice” and “passive voice”, in grammar terms.

Report comment

You asked “how do we decide who is correct? How do we know what is true?”

and stated “The drugs classified as “antipsychotic” are similarly varied in their actions in the brain.”

Whatever has results we can judge as correct and true.

I as a person diagnosed with severe mental illness at age 19 , and now 48 , and I do not take psychiatric medications, where do I fit into “who is correct? what is true?”.

Authority used to use external devices such as ropes and chains on the mentally ill, psychiatric medications invisibly chain the misbehaving patient. http://time.com/3506058/strangers-to-reason-life-inside-a-psychiatric-hospital-1938/

To claim the new chains are better than the old chains gets you a paycheck.

Report comment

Sandra,

I don’t think you need to appeal to Kahnemann’s theory or any fancy psychological terminology here. The problem you’re addressing is straightforward matter for rationality. Everyone has their own individual understanding (Kahnemann re-labels understanding as the ‘ability to make rapid inferences’) based on their experiences, past and reason. That’s human nature and there’s nothing wrong with it. And so it takes good arguments and quality evidence to change one’s understanding. That being said (and that’s a traditional position) I’ve never seen someone change their understanding just based on the “weight of new data”: anyone can derive as much as data on anything they want. I wouldn’t expect anyone to change their views due to data; data is in and of itself meaningless until interpreted. Data needs to be formulated into an argument that appeals to understanding before it means anything.

Think of the most obvious case of the “data-weighing” fallacy: clinicians continue to produce positive clinical data for psychiatric drugs even though researchers long ago showed there’s no basis for this. Where’s this positive data coming from then? Clinicians are simply cherry-picking outcomes, excluding AEs & non-responders and ignoring underlying drug mechanisms to produce supportive data. They’re doing a great job of supplying an overwhelming “weight of new data”. I’m sure that they will continue doing this and can do it ad infinitum, even though a rational interpretation of their data immediately shows it to be junk.

So we’re left with the good old fashioned human dilemma: how to use our own reason to improve our understanding? From what I see and hear in the medical profession, it seems like physicians constantly struggle with this. You’re always seemingly at at a rational deficit and I think it’s because you’re trained from the outset to use textbook concepts taken on authority. If you take a class in critical thinking, the first thing you learn is that an ‘appeal to authority’ is a glaring logical fallacy and invalid in argument. Unfortunately this uncritical approach in medicine has meant that medical doctrines, disproven by research, can persist for decades, even centuries, and cause tremendous harm, without physicians changing their practices.

So, the solution to the problem you raise is simple: use your reason, prove your case and win the argument. Otherwise you’ll be following the “data” into your grave, probably doing great harm and changing no one’s mind.

Report comment

Thanks for your comments. I am not sure how “use your reason” will protect one from these various biases. In your use of the term “appeal to authority” you are referencing Kahneman’s work. The problem I am posing is that we all struggle with this, we are all vulnerable. At least that is what my reason suggests to me.

Report comment

Sandra, may I suggest two things? Listen to your patients and stop prescribing psychotropics.

Report comment

In my humble opinion, I think people have a problem with drugs for a few of the following reasons:

a.)The drugs had side effects worse than the condition they were purported to treat.

b.)They caused irreparable damage to the person who took them.

c.)They were improperly prescribed to the person, either in terms of being given drugs they did not need, or in dosages which were an overkill.

d.) They were prescribed drugs for problems in living which had nothing to do with being prescribed drugs, or there was misplaced emphasis on drugs “making the person better”, when the “becoming better” part would not be solved by drug use.

e.) They were forcibly given drugs.

f.)They did not have pre-existing information about the dangers of the drugs and were not given proper information about it.

g.) It didn’t just end at the drugs, but they got involved in the whole psychiatric paradigm which goes beyond simply prescriptions, which caused trouble. This psychiatric paradigm involves being labelled, an addiction to appointments, playing the indignant patient role, being disease mongered on, surrendering power over to the labellers and their organisations, social and legal problems like abusive parents, spouses, children, divorce cases etc. all of which made worse by psychiatry and in some of the cases we find here, forced treatment.

After all, drugs don’t take themselves, just like knives don’t kill people by themselves.

Human beings have been ingesting various drugs in the form of nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, ayahuasca etc. for centuries. Today there are drugs which are termed “medications”. The fundamental principle is the same. A human being ingests any drug, whether prescription or illicit, because it makes him feel better in some way. *Of course, this is when it is voluntary, not forced. And not drugs which have terrible side effects, which I as an individual have already faced in the past*

Now, if the additional psychiatric junk (labelling, power structure, dependence etc.) did not exist, and people had full awareness of the long term dangers of these drugs (and there are long term dangers with street drugs too), their side effects, how to mitigate them etc., I presume some people would buy them over the counter without any psychiatrists at all (just like they do alcohol or anything else), just to ease mental distress like a low mood, or anxiety or whatever else it is, caused by whatever problems, just like some people engage in “substance use”.

But to me, this is similar to some people choosing to drink alcohol every night to relax.

So, I would rephrase your comment as “Listen to your patients, and stop prescribing them psychotropics or make some changes when they tell you the points above.”

Because if some find them beneficial, it is their choice to take them, and her (unfortunate) duty to prescribe them.

Report comment

Thanks for the comment. I think you have rephrased the drug centered approach to prescribing. In the early 60’s in a response to thalidomide, the FDA required that drugs have specific targets. This led the shift to a disease centered paradigm. This has not served us well. The field is now tripping over itself to explain why ketamine might be helpful for depression and why so-called antipsychotics are helpful for people labeled with mood disorders who have never experienced psychosis.

Report comment

There is a lot of emphasis on studies, and receptors and this and that.

Which is why, to me, it is the real life experiences of people that matter, and a resolution of cases in a case-by-case, individual-by-individual manner that is important.

We do not see enough posts here by lawyers and attorneys who have dealt with individual cases involving psychiatry, DSM labels, drug effects etc. Having those cases, and the knowledge of how respite was provided to an individual negatively affected (directly or indirectly) by the psychiatric paradigm, would be very beneficial.

MIA is a hodge-podge of people variously affected by the mental health field. Every case is different and unique in its own right, with there being some overlap in themes among different cases.

Edit: I wrote this before I saw Dr.Steingard’s follow-up comment.

Report comment

I have just read the article in Schizophrenia Bulletin and I didn’t pick up that he was making an apology; it seemed more like a “my interesting career” article. And it is still all about D2 receptors whatever it is that messes them up. Nothing about people. Did he have patients? Or was his work purely laboratory? What did he get a knighthood for?

Report comment

Bramble,

I would agree that Sir Murray still holds on to a fundamental notion that neuroscience will lead the way to a deeper understanding of this kinds of experiences. I am less sure of that.

Report comment

Sandy I deeply appreciate this essay of yours. I agree this is complex stuff. But some of it isn’t complicated at all….. like study 329: not complicated! Psychiatrists blatantly lied and put public health at risk. I know that’s an example of an antidepressant and so not as relevant but the point is some of this stuff is actually straightforward. Lies vary rarely lead to good medicine, especially when the lies are created on behalf of special interests. Again, thanks for your essay. Full disclosure: I am a SURVIVOR whose life was derailed by psychiatry.

Report comment

Thanks for the comment, Randall. I am angry about this same kind of thing. I believe this is what fuels some of my passion. But I still wonder if that anger clouds my thinking in other areas. That is what some have told me. This essay is a reflection of my reflections on these wonderings.

Report comment

Dig deeper into the egregious corruption. Don’t get me wrong. I admire your probing of the tough calls and ambiguity. But some of this stuff isn’t a tough call at all. Your anger and passion aren’t clouding your judgement imho. You are pushing the conversation forward, bravely. If I had known about you and Bob six years ago my life would be about 10x better. Hope this makes sense. Thanks

Report comment

I dedicated this blog to Mickey Nardo. There is a link to his blog. He has done remarkable work in dissecting studies and exposing corruption. It is an amazing and important resource.

Report comment

Acknowledgement Of Medication Dangers.

Dear Sandy,

I believe Robin Murray has also acknowledged that genuine Recovery from “schizophrenia” can only come through “psychotherapy”.

It is written into my own records in the UK that I am “allergic” to certain psychotropic medications – but Akathesia and Suicidal Reaction to medications is not directly entered into the records (as far as I know).

I notice in the case (LINK below) that the charged person called up an ambulance twice in the year previous to the dreadful event because they feared harming themselves – what kind of a person behaves like this?

https://www.google.co.uk/amp/www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/38878443

The charged person has been diagnosed as having acted during an acute “schizophrenic” episode – I wouldn’t be so sure.

I have attempted suicide twice under the influence of psychotropic medications – but this was medically suppressed on my records (to the point of future endangerment).

Report comment

Thank you for this, Dr. Steingard, a lot to chew on here.

“If we all have confirmation bias, how do we decide who is correct? How do we know what is true?”

What a gorgeous exploration these questions make. I can’t imagine all the diverse responses these questions generate. At least that I know is true.

“While I like to think of myself as deriving my conclusions through careful research and reason, I am also told — repeatedly — that I am passionate and some have suggested my passion clouds my reason. I like to think my passion drives me to reasoned inquiry, but who knows?”

I think passion makes us human. All of us are right sometimes, and wrong sometimes. Who cares? Life is not an exact science, it is a creative endeavor. Without passion, we are totally dull and spirit-less.

Healing from what I experienced as a psychiatric client involved a great deal of forgiveness, in addition to actually fixing the damage. In addition, I could begin to harness gratitude for the experience of awakening to my true path and spirit (my personal truth) to which all of this led me. In the end, we are all human beings doing the best we can with what we know, learning as we go–hopefully. How we affect others is something we might or might not consider along the way.

I can forgive what psychiatry and the mental health system did to me–the deep harm and betrayal–but that’s not a pass to continue doing it. It means that I’ve released my resentment, because I recognize how this all adds up for me and my life, how I’ve been guided to where I need and want to be at present. This is for my good, and for my holistic well-being, makes me feel lighter and clearer when I release resentment.

But it still makes me angry that it continues, despite all of the obvious protests. So many of us call psychiatry and the like social abuse, purely. There is a lot of gaslighting that happens here, and that is very dangerous for people, can really mess people up. Can we perhaps look into this and see what this over the top oxymoron is about, that psychiatry is actually crazy-making? I believe it goes way deeper than the psych drugs, that’s just a symptom of the core issue here…

Report comment

What Peter Breggin wrote in “Beyond Conflict”, is that Psychiatry was invented to give justification for incarcerating homeless men, who were breaking no law. He is talking about the 1600’s, and he is of course drawing heavily from Foucault.

Today it still seems to work exactly the same way. The concept of Mental Illness is inseparable from poverty, homelessness, and familial scapegoating.

Economic problems and child protection failures get converted into bogus claims of mental illness, and these in turn are used to support the resurgence of eugenics. In order to keep our economic system running, it is necessary to have scapegoats, and it is necessary to delegitimate those on the margins.

And as it looks, the federal Housing First initiative is now getting used to justify building homeless internment camps, and to pressure people into accepting a mental health interpretation.

And then Psychotherapy, Recovery, Life Coaching, and Healing are pretty much sugar coated versions of the same thing, dealing with social marginalization and abuse by denial. Do anything it takes, except seeking political and legal redress. And the survivors of abuse and marginalization make for an excellent source of profits.

And then all of these things are merging with Evangelical Christianity, via their outreach ministries and their involvement with local governments. And one of the leaders in this merger is Rick Warren, founder of the Saddle Back Church in Southern California.

http://hope4mentalhealth.com/

“Second Chance Grace Place”

“Everybody needs Recovery”

around 5:00

http://mediacenter.saddleback.com/mc/m/4028b

Recovery has become the new Original Sin. And vast numbers of people listen to Warren and the others in his movement. It is all about turning the blame back onto the victim. Most of the people in these churches have designated scapegoats in their own families, as did Rick and Kay Warren.

So we need to start responding to Psychiatry, Psychology, Recovery, Life Coaching, and Healing, with lawsuits. Lets build up a list of interested attorneys.

Nomadic

We need to form an Anti-Mental Health, Anti-Recovery, Anti-Self-Improvement, Anti-Eugenics forum. Posts will not be censored:

http://freedomtoexpress.freeforums.org/index.php

Report comment

Great writing.

It does seem that the drug-centered explanation for why some people experience some relief some of the time is the best one. This is also evident in the fact that other types of drugs, like benzos or opioids seem to calm them down as well.

People have taken intoxicants to “take the edge off” unpleasant feelings since time immemorial, so this is hardly surprising.

Report comment

I don’t think it helps to have a doctor admit to mistakes his or her profession has made without those mistakes being delineated. There is much need for a paradigm change in psychiatry because of the drugs being used on patients. Those drugs have been shown to:

1. debilitate, and effect one’s overall physical health in a negative fashion.

2. impede the process of recovery, if in fact the patient recovers, and also increase the severity of the “disorder” they would be “treating”.

3. put a patient in the grave 15-30 years before the patient would have died by “natural causes”.

I think it important that people get a grip on why “mental health treatment” desperately needs to change. When people are dying because of standard practice, more aptly referred to as standard malpractice, this is something that affects everybody. I don’t think the case can be stated often enough. There are a great many reasons why doctors should be doing some things differently.

Report comment

BBC Today:- Unexpected Mental Health Deaths up 50% in Three Years

“…The number of unexpected patient deaths reported by England’s mental health trusts has risen by almost 50% in three years, figures suggest.

The findings, for the BBC’s Panorama programme, are based on FOI results from half of mental health trusts.

Unexpected deaths include death by suicide, neglect and misadventure….”

https://www.google.co.uk/amp/www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/38852420

Report comment

Thanks, Fiachra! I cut-n-pasted a paragraph from the article you linked to. It’s an excellent example of the gobbledygook, fuzzy logic, and double-speak which psychs are expert at:

“A Department of Health spokesman said: “This increase in the number of deaths is to be expected because the NHS is very deliberately improving the way such events are recorded and investigated following past failings.” <–from the linked article

Think about what's REALLY being said here: Better AFTER-the-FACT "reporting" and "investigating" is *CAUSING* more deaths. Try using car crashes as an example.

Imagine a Police traffic spokesperson saying: "Were doing a better job reporting and investigating traffic crashes, so there's more of them" Does that make sense?

This kind of taxpayer funded nonsense is hurting and killing us all, "MEA CULPA" or not!….~B./

Report comment

It is interesting that you posit that the scientific method can lead to errors. However, the scientific method was devised specifically to avoid the kind of confirmation bias you and the earlier author are reporting on. Hence, the errors in psychiatry are not errors of the scientific method, but errors that arose from failing to apply it in favor of personal, institutional, and/or financial conflicts of interest.

I think it is VERY important to stress that good science had already invalidated many of bio-psychiatry’s main premises in the 1980s, and any serious application of the scientific method at this point would completely destroy the idea that giving people drugs for life for “schizophrenia” is completely invalid, not only because it doesn’t help in the collective over time, but also because the category of schizophrenia, like almost every artificial “diagnosis” in the DSM, has no scientific legitimacy whatsoever.

Thanks for your intellectual honesty and your willingness to tolerate the masses of feedback and emotion your posts sometimes stir up. It’s a sure sign that you’re on the right track when lots of people want to comment on your discussion!

— Steve

Report comment

There is a major discussion going on in other fields about the failure to replicate studies. This has gotten much attention In psychology.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reproducibility_Project

There is now a major effort under way in cancer research.

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/01/rigorous-replication-effort-succeeds-just-two-five-cancer-papers

There seem to be many factors that contribute to this – cost, subtle bias.

For me, it does not undermine the scientific method but demonstrates how hard it is. In the meanwhile, we all form ideas about what is true. These challenges lead some to completely denigrate science and we see the emergence of “alternative facts.” For me, it leads to some deep sense of unease about the shifting sands of knowledge along with an aspiration towards humility.

Report comment

Yes, I DO expect an answer here, Sandra. I say that psychiatry is a PSEUDOSCIENCE.

What do YOU say?

Q?: Is psychiatry a pseudoscience?

YES, or no….????….

What’s your answer?

It MUST BE one or the other.

It MIGHT be EITHER.

It CAN NOT be NEITHER….

……..?????……..___________________?

Report comment

Humility is the key. Real scientists understand that science is intended to undermine their confirmation bias, and want to know the truth, even if it is not convenient. Wolfgang Pauli, one of the founders of the theories of quantum mechanics, said that he really WANTED his findings to be false and did everything he could to try and falsify his findings, but could not. He begrudgingly admitted his original hypothesis was wrong. That is what a real scientist does, but we don’t have a lot of real scientists at work any longer, because they have other priorities, including making money.

Report comment

Sandy,

Your humility, ongoing self examination and scientific search for truth are admirable.

Thank you again

Report comment

“I also wonder how I can know when I am misled in my assumptions.”

“[I like the drug focused model] because it helps me to consider these drugs not as a specific treatment for a specific disorder but as psychoactive drugs that may have some benefits for some people at some times.”

I quoted these because I want to respond to them alone, at risk of replying out of context, rather than the overall topic of the article which is a synthesis of different pieces about acknowledging of mistakes, changing perspectives, and moving on. For me the only ethical answer in these scenarios is for the “client” themself to be the one to have FULL access NOT to “informed consent” regarding drugs but to the gamut of materials disproving the chemical imbalance theory and reviewing the horrid past and current behavior of psychiatry as a field. I still get a sense that some psychiatrists feel that there is a “time and a place” for an authority figure (ie a psychiatrist) to “choose when to employ drugs” as a “part of that client’s plan”. I guess I feel like the client should always be the one and only authority figure in the room, which means, what is the role of the psychiatrist? A redundant question, since if the psychiatrist has no authority to suggest actions then they serve as a figure for someone to come to and say what they want, ie the “psychiatrist as a vending machine”.

Like some other commenters I think there is never a legitimate time or a place for these drugs, that they do more harm than good, that completely “untreated” fill-in-the-blank is preferable to going on the drugs, and consider myself a psychiatry abolitionist. I’m not sure if I even want you to reply to this, and I do not mean this as a personal attack but rather what came up for me reading certain sections of this. These select quotes, which may or may not be out of context, just reminded me of how I feel that even psychiatrists who dedicate their life to learning how to cause the least harm and be the most human are often still open to letting people choose to roll the dice at times and still open to holding secret knowledge in the room above the client even if the psychiatrist is armed with quality literature such as Anatomy of An Epidemic. I mean, how many psychiatrists directly tell their clients about Anatomy of An Epidemic even if they have read it themselves? I feel that the only real way to stop the harm is for psychs to completely stop prescribing and instead to use sessions showing people where they can start their own research into alternatives, or helping them taper off, then letting them go. Not as a personal attack to you Sandy but rather just in general sometimes this type of article makes me feel jealous that I have to be on “this side” of psychiatry, I have been chemically mutilated, made disabled and traumatized and it’s not a question of somewhat abstract ethics or moving a field forward for me. It’s my life. I wish I had my life and my health back.

Report comment

I am sorry for now you have suffered. I wish you the best. Thanks for reading and commenting.

Report comment

Dear surviving the system and Sandra and others,

This was an interesting dialogue it is a start. Thanks all for your thoughts.

I think the pain of folks here is palpable and strikes me to the core because I feel it as well. I do wish I could relive my 16 years and undo it all and excise the memories especially the really really bad ones.

Sandra if you are reading – undoing is on of Anna Freud’s defense mechanisms. Have you read her work?

Children use it and so do adults though one would like to use sublimation more.

The damage we have suffered like so many humans do through the Agee is done. No matter how hard we sit for it not to be.- it was. So what do we do with justified anger and outrage. We can use it for good and we can try to let go with forgiveness and acceptance. Not an easy task especially when MH professional folks are unable to go the full ten yards with the idea yes bad things happened, we are sorry, and although we cannot change your past we will try to make amends.

I think Sandra you personally and others are struggling with acceptance of this paradigm and I thank you for the initial efforts.

One way might be a medical record line line tool to strike out the label and diagnosis in our charts. Some sort of mechanism to undo the label forever.

What do folks with Type II diabetes have in their charts when they successful end the issue by diet and other means?

Maybe this needs to go throughout the medical world.

Strike Out the Diagnosis!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Report comment

Thanks for your comments. I am still reading and listening.

Report comment

Dr. Steingard,

1.) A certain question has always puzzled me. Psychiatrists and mental health workers often talk about the stigma associated with mental illness. However, in my view, part of the stigma is caused by the very labelling itself.

Let me give you a few examples. I have met people labelled as schizophrenics, who are otherwise, quite smart, articulate, some even have Ph.Ds, others are graduates etc., who at some point in their lives may have had certain problems of thinking, feeling and living. On the other hand, there is the perception of a “schizophrenic” as that homeless, paranoid man that talks to things in the air, is psychotic etc.

When you give both classes of people the same label, naturally, stigma will follow even the smart, articulate ones, even if undeservedly. Also, it need not be that the paranoid, delusional, homeless man may be that way forever.

Why don’t some of you actually engage in explaining to people the dangers of labelling, myths etc. during your talks?

2.) As a legal example, think of a man labelled as a schizophrenic at some point in life, let’s say because he had some sort of a delusion that the CIA was following him everywhere, and there were tracking devices everywhere in his home or that aliens abducted him. This was at a point in life. Now, he has them no more, and realises the irrationality of those past thoughts. But, the label remains. OR he may even still have some thoughts that way.

However, during a legal dispute with a family member who knows about the label, the family member uses it, reads up all the worst possible behaviours, delusions etc. associated with the label, and alleges that the labelled man has all those. How does the labelled man disprove it? He has to rely on the charity of his psychiatrist, who may or may not act in his best interests, but will first keep his own professional interests in mind.

These are some things to think about, and more importantly things for some of you to do.

In fact, I do not specifically see articles on these topics on MIA either. They are usually pretty long biographical articles or vignettes about research findings.

There are always talks of stats, and studies full of terminology, effect-sizes, confidence intervals etc., but the more practical issues like the points I’ve raised get left out in talks/presentations given to the public which are sometimes uploaded to social media websites like YouTube.

Why do no psychiatrists give talks on these matters? It would do a lot more for people who bear these burdensome labels, than some study which finds that X-drug is over used in population type Z.

Report comment