I recently submitted my last article about 10 things I’d learned in 5 years of consulting with people coming off psychiatric meds to a local zine requesting writing on alternative approaches.

I did not read over their submission guidelines carefully, nor did I know who they were or what they stood for, except that they seemed to be speaking out against forced treatment and for humane alternatives.

It was described as a zine on mental health responses that don’t involve the state, insurance, etc. originated by people who both struggle with mental health concerns, have been non-consensually incarcerated for “treatment,” and provided this support to others.

I got an email back saying thank you for your submission, but it doesn’t really fit with the topic of mental health crises, these are the questions we want answered (the same ones I had skimmed over the first time):

1. How did you become aware of the need?

2. What made you decide to meet it?

3. What worked well? What didn’t?

4. What community supports does someone who is doing this work need?

Having a busy week where I was getting multiple emails a day from people who had read my blog and told me how psychiatric drugs had ruined their health and life, I starred the email in case I’d have time to write a piece for the local zine, answering their questions more directly.

I never did get to it and it fell into my long list of starred emails that I’d respond to if time started falling from the sky one day…

About a week later I got another email from the local zine organizer. They asked a few questions about my experience and said they would be interested in a story about helping people go through the withdrawal process. They wrote, “We would not publish anything that said that psychiatric medicine was bad ‘full stop’ as at least one of our organizers credits their meds with keeping them alive.”

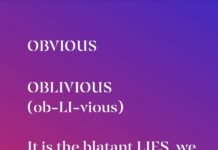

I hadn’t used the word “bad” to describe psychiatric drugs, and certainly not the phrase “full stop,” and it disturbed me that by writing about what people are struggling with on psychiatric drugs and in withdrawal, someone would feel the need to caution me against saying psychiatric drugs are bad “full stop.”

There is such a large platform and loud microphone for “PSYCHIATRIC DRUGS SAVED MY LIFE.” No one hasn’t heard that line. It’s the mainstream party line in conversations about the dangers of psychiatric drugs and withdrawal, such as: “Of course psychiatric meds save lives and some people need them but for others they can be problematic and near impossible to get off of…”

“Psychiatric drugs save lives” is considered medicine and science by journalists. They write that, or something similar, as a disclaimer almost, as if to say they aren’t anti-science, anti-medicine or anti-evidence. They write it to give “both sides of the story,” while plenty of news articles are written about psychiatric drugs that don’t give the side of the story where psychiatric drugs ruin lives and kill people.

The media refers to the side of the story where meds kill people and make them suicidal or disabled as literature, opinion, politics, anything but science and medicine. This is odd because scientific studies do show that psychiatric drugs cause suicidality and many health problems in a large number of individuals.

Psychiatric drugs cause enough severe health problems that the drug companies have to warn of all of these possible conditions on every single advertisement and prescription.

“Psychiatric drugs save lives,” while it may be a true statement for many, is at least as close to mythology and opinion as “psychiatric drugs destroy lives and kill people” (I’d say much closer, but that’s “just my opinion”). It could be placebo and/or getting attention and other help that actually saves the lives of those in despair. We don’t know for sure.

What we do know is that once someone’s life is destroyed or killed by psychiatry, they no longer have the voice to testify. That’s why I wrote the blog Michael Samuel Bloom, my very first post on Mad In America. Michael fell into both camps: one might say psychiatric drugs both saved his life and killed him. Again, there is no scientific evidence that can prove or disprove either statement.

Life and death also can’t exactly be reduced to a pill, as there are many people with the same diagnoses who take or abstain from the same pills and some live while others die. Since the diagnoses don’t have biological basis or involve medical tests, there’s absolutely no evidence of a medication curing, halting or slowing any biological process that would be killing someone, by their own hand or otherwise.

I wrote that blog because no one else was going to tell the story of how psychiatric drugs killed Michael. I’m not saying that is the only story, but it is part of a larger story, a part I could see, having known him his whole life. I understood things maybe others in his life didn’t, having been on the drugs myself and worked with others on and off them for over a decade when Michael killed himself soon after having been put on several more drugs.

I’m not worried about marginalizing people who think psychiatric drugs saved their life. Their story has been told over and over. That doesn’t mean it isn’t true. Their suffering was and is real, and psychiatric drugs may have relieved some of it in a way that prevented them from suicide or other death-inducing behaviors. The same could be and has been said of heroin, alcohol and other substances.

Just because psychiatric meds may save some lives, doesn’t mean they are the best or least harmful way to save lives. A starving person’s life can be saved by candy bars, or by a home-cooked, locally grown meal made with love, care and fresh ingredients. Both will save someone’s life, but if eaten day after day for every meal, the candy bars will eventually ruin the person’s life and health, while the home-cooked meals will enhance and build it.

In an emergency moment, the candy bars may be just what someone needs to prevent starvation: the quick sugar, the high calories. What helps someone survive in an emergency is rarely what helps sustain and nourish them day after day. Long-term healing requires nourishment on all levels rather than chemical sedation, stimulation or restraint.

It’s not about whether it’s right or wrong, true or false that psychiatric drugs save lives. Science can never figure out for sure if it is a drug that saved someone’s life or all of the other factors that go along with having an emergency, getting a diagnosis and taking a prescription medication that one is told will help relieve their suffering.

It’s about telling the stories that aren’t being told.

That’s why psychiatric drugs saved my life after they destroyed my health and nearly killed me. They gave me something I care about and am passionate about writing about. They gave me a pathway to bring healing to others. Life is paradoxical that way. The thing that nearly kills us, can also save our life. The thing that saves our life, can also kill us.

I fear for my life when I don’t take medicine. I’m threatened and harassed 24/7.

Report comment

Hmmm…are you threatened because you don’t take medicine?

Report comment

Are people threatening you with AOT or locking you up in a psych ward? Or do you hear disembodied voices threatening you, Pat?

Report comment

This is a great Article Chaya. You’ve answered your calling.

I read through “…destroyed my health and nearly killed me…” and I can’t help feeling that you would have been better off had you taken street drugs. You would at least have had some real enjoyment (and access to relevant information about what you were consuming).

Psychiatric drugs nearly killed me again and again and again. When I recovered as a result of quitting drugs suitable for SMI and clarified this to my Psychiatrist he moved from Galway Ireland, to Ontario, Canada.

(He was to return to Ireland though, and write promotional research papers on the offending Drugs – for Money)

When I caught my present day GP in the UK exploiting my records he was apologetic. He committed verbally and in writing to removing all diagnosis. I discovered shortly after that he hadn’t.

He got away with this, but two months later he was involved in a patient fatality that went to the Coroners Court.

(Both doctors had been genuinely spooked, because ALL the evidence documentary and otherwise, pointed to Suicidal Reaction + Disability from Psychiatric drugs, and a return to Full Wellness as a result of carefully quitting these drugs).

Report comment

Thanks Fiachra. I’m glad you’re still alive to tell your story.

Report comment

“Psychiatric drugs save lives” is a meaningless phrase. But what are we talking about? Suicide, of course. It is well known that neuroleptics and antidepressants increase the risk of suicide. To say that neuroleptics and antidepressants “could” reduce the risk of suicide in some people is as doubtful, as implausible as saying that soaking one’s wound in a putrid swamp “could”, in some cases, improve the healing.

But then why do some people claim that psychiatric drugs saved their lives? Here is my answer:

People unable to take responsibility for their deaths are also unable to take responsibility for their survival.

Just as they attribute to a “disease” the suffering of their lives, they attribute to a drug the responsibility for their survival. But this opinion is similar to that of the savage who believes that his wound has been healed because a sorcerer has put a dirty ointment on it. In reality, the ointment has increased the risk of infection, but as the wound has healed anyway, the savage attributes it to the ointment.

These false beliefs about psychiatric drugs are only the extension of the disempowerment of patients, the need for unreality, especially on sensitive topics such as life and death.

These beliefs are understandable, but if we want to be responsible for death and survival, we must stick to science.

Healy, D. (2012). Benefit Risk Madness: Antipsychotics and Suicide (html) https://davidhealy.org/benefit-risk-madness-antipsychotics-and-suicide/

Healy, D., Whitaker, C. (2003). Antidepressants and suicide:risk-benefit conundrums (html) J Psychiatry Neurosci 2003;28(5) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC193979/

Report comment

Wow, what a powerful statement:

“People unable to take responsibility for their deaths are also unable to take responsibility for their survival.”

I felt this truth in my gut, literally, when I fired my obstetrician at 30 weeks and decided to have a homebirth with a midwife instead. I Trusted her, this midwife. I was unwilling to cede the responsibility for the well-being of my child and my Self to this man my gut told me was a Danger, “specialist” or not. Thank you, Sylvain, for words that perfectly express what I felt in that decision. The assumption of risk belonged to Me and nobody else. I had no regrets in the least doing what I knew from the heart of my intuition was right, and my baby (over 9 lbs) was born at home, perfect APGARs, and I did not tear or require even 1 stitch. Neither of us would have had a sunny outcome had I not followed my gut and just caved to the threats and fear-mongering he tried to pull on me. But I trusted Myself, put my life and the life of my baby in my Own hands instead of trusting him more. He was flabbergasted at being fired!

Report comment

Sylvain, thanks for your comment. I agree with you that people have a hard time being honest with themselves. On one hand I think you are right, that there is a personal responsibility that is being averted.

On the other hand, I don’t think people need to take total responsibility for everything in their lives OR put the responsibility on diagnoses and drugs if they are able to hold complexity. In fact, I think if people were able to accept that they don’t actually know why they lived, or the exact cause of their problems, and acknowledge that there were/are a bunch of different possibilities, explanations and forces at play, they might be able to find peace without dishonestly clinging to an unscientific or untrue explanation.

If it’s a choice between saying it’s all their responsibility or all a diagnosis and a drug, many people will choose a diagnosis drug…but if it’a also socioeconomics, trauma, mystery, fate, etc etc…then there doesn’t need to be one answer. To me that is more honest, and even more scientific.

Report comment

We’re talking about murder too, not just suicide.

Yes, most of the cases where people who are not naturally homicidal and become so, are caused by these drugs. But not always.

There’s the case of Andrea Yates – probably caused by the drugs she had taken.

But there was a similar case about 200 years previously in Maine, documented in a book by a midwife who worked in the community. No drugs involved, obviously.

Sometimes, there isn’t time to deal with a problem via the long (of course more effective) non-drug route – dealing with trauma, giving empathy etc

Sometimes you need to inject someone with something quickly, and then, when they cool off a bit, you can go the long route. Sometimes you don’t realize things have escalated so far until the situation explodes and it’s too late to intervene less drastically.

You may argue that the injection violates their rights or whatever – but of course, murder violates rights too.

Yes, thank you Chaya! I’m presuming that with your candy bar analogy you are acknowledging that there can be a very limited, short-term place for use of these otherwise life-destroying drugs. If someone has another emergency first-aid way of getting someone “down” from a mad spell that threatens to turn very violent, I’d like to hear it – truly. It’s all very well to write, “They just need to be in a supportive, loving environment,” or whatever, but people who are in the grip of terrible paranoia do not recognize that environment for being supportive – they believe themselves under attack from all sides and that can have disastrous results.

Report comment

Yes gabi, I agree and thanks for your comment. As far as we know all or almost all of the mass shooters in recent years were on psych drugs. CCHR has a list of all of them if you google it.

I do think in emergencies, drugs can be helpful, when taken as a one time thing, or maybe for a few days to help some one calm down or sleep if there’s an emergency need for sedation.

There may be herbs and less dangerous techniques that can work too. Recently a young woman in my town died of a chemical restraint, that was a benzo.

Some herbs are extremely calming and sedating, and safer than benzos. An expert herbalist would know more than me, even while I’ve been studying and using herbs for a long time. There are those who know more. Sometimes even good food can be enough to stop violent behavior. Common sense often goes out the window in emergency moments.

Here’s something I wrote with some alternatives:

https://chayagrossberg.com/alternatives-chemical-restraints/

Report comment

Szazs talked about murderers who committed crimes out of obedience to “God” or space aliens. He suspected they heard these voices because they wanted to murder and needed an excuse.

Why obey some voice telling you to commit murder anyhow? “Just following orders” is a lousy excuse whether they come from a colonel or an imaginary voice in your head.

My drugs caused me to hear voices telling me to rip off my clothes and run around swearing…never acted on it. And none of the drugs helped–they were the cause of this nightmare!

Report comment

How will having 6 orderlies dog pile on top of them and inject them with a mega-dose of stupifying Haldol make them feel more secure? Never had to be forced but that stuff gave me seizures!

If they are dangerous they certainly should be locked up. There’s no drug known to science that can transform Timothy McVeigh into Gandhi.

Report comment

No but I did notice those PRN’s did a great job of calming down the “staff.” Ever notice that? Take a pill and then they left us alone.

Report comment

That’s the much vaunted placebo effect! Still works on my family.

I recently visited my parents since my brother was there with my nephews and niece. Around evening I’d say, “Need to take my ‘meds’,’ and pop a bunch of supplements I’m forced to take because of my ruined gut. No one was any the wiser.

When we “mentally ill” don’t take our pills, those around us can get pretty paranoid–dare I say psychotic? Take your “meds” to prevent their going crazy!

Group paranoia is the real phenomena at work here. Like ye olde witch hunts. Hanging/burning harmless old ladies may not cure the outbreak of plague, end the drought, or make the cows lactate, but it makes us feel warm and secure. At least SOMETHING is being done.

Report comment

Well said Rachel.

Report comment

this is in response to Gabi’s request: “If someone has another emergency first-aid way of getting someone “down” from a mad spell that threatens to turn very violent, I’d like to hear it .”

How about being on their side? Not pacifyingly, but agreeing with them, radically being with them. Instead of countering their fear, terror, paranoia with rationality and trying to bring them around to agree with the consensual reality, flip the script. Try being in their reality with them, as an ally. You cannot be an ally while insisting they are wrong and you are right. Doing that only paints them into a corner and makes you another thing they need to protect themselves from, so don’t allow the consensual reality to dictate your interactions.

Rev. Dr. Steven Epperson gave a lovely example of this in one of his blogs here on MIA, a story about a woman who spent all her time under her bed acting as if she were a fish. What made her finally talk to someone about why was that the man had joined her in being a fish: he laid down under the other bed, assumed the same position, looked at her and said “glub” probably through puckered fish-lips. He did this patiently until she trusted him enough that he was an ally fish, and finally trusted him and herself enough to be willing to be human again.

Now, granted, there was nothing threatening in her demeanor as a fish. But the technique would be the same in terms of gaining trust. Can’t be done if you are frightened, feel threatened, or are pacifying them long enough for them to drop their guard so you can proceed with your agenda. You’d have to be open and curious and caring, willing to step into their reality and be on their side. Being an ally can often de-escalate a situation that otherwise would escalate to somebody getting assaulted (and yes, needle rape is definitely an assault!).

One of my favorite shows is Grey’s Anatomy, and I can think of several examples on that show in interactions between the doctors and patients with Alzheimer’s. When Dr. Ellis Grey was admitted to the hospital, they needed to do a basic exam, check vitals, etc. but she thought it was decades earlier and that she was running late to perform a surgery. When Dr. Karev went with that narrative instead of insisting she agree to the consensual reality, and told her it was a new hospital policy, she rolled her eyes and allowed it. That’s just one.

I would think that people who have experienced the “yes, and” of improv theatre would be good at this.

Report comment

I like your idea – I wonder if you know of any examples where it’s been used and found effective. My personal experience with someone with extreme paranoia (my husband) is that he didn’t open up and tell me about his fears because he had enmeshed me in them and feared me too. There was no one left in his world that he trusted. But each case is different.

The story about the woman who thought she was a fish is a plagiarism of a very old (over 200 year old) story attributed to the Jewish Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. It’s called “The Turkey Prince” and is about a prince who thought he was a turkey and spent his time undressed under the table eating crumbs and picking at bones. He was healed by a wise man who joined him there in his situation, and then said, “You know what? We can be turkeys and get dressed too.” They got dressed. “You know what? We can be turkeys and eat regular food.” They did. Eventually, the prince came out from under the table and started acting like a prince again. And his state of mind reflected his actions (which is also a Jewish principle, that a person is influenced by his behavior).

Report comment

Gabi I recall when my late boyfriend believed he was a “federal agent” I went along with it. I listened to his entire fantasy about his work as an “agent” and all that that his “assignments” entailed. I kept on listening and if something sounded scary to me, I said so and asked him if he also felt scared or threatened. He said he did. We talked through all of it and I never said “That is not true.” I never tried to prove him wrong nor rationalize nor minimize anything he told me. ALL of what he said was based in reality, and actually much of it I never realized until years or even decades later. For instance, a lot sprung from his anger over my ECT. I was barely aware that I’d been damaged by it, but he was painfully aware that the person he had known may not come back from ECT fog (I did!).

Another thing I perceived at the time as being unrealistic was his claim that the drugs were “poison.” He insisted they were “bad for him” and he did not want to take them. He spat them out and hid the spat-out pills from the staff. One day, he handed me a wad of them that he had spat out, saying, “These are poison and I will not take them!” I didn’t know what to do except walk away and toss them out in my trash.

Now, well over a decade has passed and in my heart I know he knew exactly what he was talking about. He knew. Even after he finally agreed to take them, which he agreed under much pressure, he knew deep down they were killing him.

Report comment

Well, I’m happy for him that he had someone so understanding to be at his side.

I found it difficult if not impossible to do the same when my husband was running through the streets yelling “Murderers!” He wanted to take “them” (most of whome remained forever unnamed) to court to sue for damages. He still blames “them” for his troubles. I’ve tried lots of things, including agreeing with him about certain members of “them” but if “they” are a convenient scapegoat to avoid taking responsibility, then it’s tricky. One of his doctors, years ago, actually told me that he wasn’t worried about the strange ideas. He said lots of people have weird ideas, and nobody has to even know. It’s the consequences that can get tricky. If you think “they” are out to get you, you might preempt the attack with one of your own. Expressing sympathy might help – it also might not. Going out armed because you’re scared might seem like a good idea unless it gets you arrested. It’s not as simple as some people would like to make it out to be.

Report comment

Gabi it wasn’t easy then either. I was scared and so were many people. As I said before eventually they drugged him and the drugs did him in…so was the outcome all that great?

Report comment

No. What’s the choice though? You tried, you stood bravely at his side, and it still didn’t turn out great.

The thing with the Turkey Prince is that he could take out time from life to get himself sorted. Not all of us – probably hardly any of us – have that option. Can we envision a society where there are enough Soteria Houses for the people that need them? (Or a society where we won’t need them at all?)

Report comment

Julie, I remember when I was first in the hospital system many years ago (in 2001 to be exact), I told my friends that, “There’s this system,” and when they asked if I trusted my parents to help me, I said, “They’re part of the system.” To them I was psychotic, but when I look back now, I knew exactly what was going on. I knew there was a totally rigged system, and like I said, this was in 2001, before you could do real research on the internet, before anyone in my world (and most of the world) knew or talked about big pharma. It was when people still thought psych drugs were medicine,

Often the one we call psychotic is in some way ahead of the curve in their awareness.

It’s like that Shlomo Riskin Quote: “When you’re one step ahead of the crowd you’re a genius. When you’re two steps ahead, you’re a crackpot.”

Report comment

Gabi and Julie, also I think it can sometimes be easier for someone who has less at stake to go along with someone’s story, versus their significant other or family member, who is probably tied into the whole drama much more. Even having an attachment to the outcome can be a hindrance in these circumstances.

Report comment

Yes, Chaya, that I observed also. This is one reason a “therapist” can sometimes be easier to talk to than a family member. The conversation is less “loaded” if you are talking to someone with less history behind her. Of course so can a friend or neutral person you meet online that you don’t have to pay $150 an hour to talk to.

Rachel, I remember saying the same thing to myself. I thought it was very sad that no one would speak to me at the time, literally no one even though I tried so hard. So I was going to have to find some “therapist” and PAY that person who was going to hate talking to me, but she was being paid to sit there and if she could stand me, listen to me. I hated the thought of it, but I figured if I was going to have any spoken conversation at all it was going to have to someone I paid. Then, of course, I realized that therapy is nothing but prostitution! I cried every day during those years, crying out of the isolation I was stuck in and lack of spoken conversation.

Report comment

Lavendersage, I love this, and I do know people who do theater improv and who are much better than the average person at being with those in “altered states”.

Report comment

thanks Chaya!

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Lavendersage, thanks for your comment. Listening to our gut is so important in making medical decisions.

Report comment

So-called “mental illnesses” are exactly as “real” as presents from Santa Claus, but NOT more REAL. So-called “mental illnesses” have no objective reality, – they ONLY have subjective reality. Psychiatry is a pseudoscience, a drug racket, and a means of social control. It’s 21st Century Phrenology, with potent neuro-toxins. The DSM-5 is nothing more than a catalog of billing codes. ALL of the bogus “diagnostic” allegations in the DSM-5 were INVENTED, – not “discovered”, – to serve as EXCUSES to $ELL DRUG$. Real people can have real problems, but imaginary, totally subjective “mental illnesses” shouldn’t be part of that. Speaking of suicide and psych drugs, we can NEVER know exactly what role psych drugs did, or did not play in MOST suicides. Not even Harvard Medical School (just for an example), has access to the data needed to study the role of psych drugs in suicide. If psychiatry were truly a REAL SCIENCE, and not a fraudulent scam of a pseudoscience, data on psych drugs would be painstakingly compiled and studied. But look at the “medical system”, – they do NOT want accurate data on psych drugs and suicide. Sure, you can say “correlation is not causation” until you’re blue in the face, but the evidence is vast and compelling. PSYCH DRUGS KILL, either acutely, through suicide or homicide, or else chronically by life-spans shortened by as much as 20 or 30 years or more…. There’s another factor which doesn’t get near as much exposure and consideration as it should, and would, *IF* psychiatry was anything other than a fraud drug racket: Why has there been NO organized clinical research on who should, or should not, be given psych drugs. I have never heard any psychiatrist or researcher say what would happen to a “non-mentally ill” person who took psych drugs for an extended period of time. Wouldn’t they become more mentally healthy than normal? Why not?…. etc.,…._____________________________________

(c)2018, Tom Clancy, Jr., *NON-fiction

Report comment

Thanks Tom.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Wow, great blog, Chaya! I particularly liked the analogy of candy bars for emergencies vs. long term health. I also appreciated your elucidation of how mainstream views are always presented as “the other side of the story” while the mainstream speakers are never required to be balanced by other points of view. This is stuff I’ll be able to use in talking with others about the strange anti-critical bubble that seems to surround the psychiatric worldview. Thanks!

Report comment

Thank Steve! Good luck in speaking about it with others. Somehow facts seem less relevant in these conversations than they should be.

Report comment

Maybe they consider these pro-pharma ravings “the other side” of the story because a “crazy” is allowed to talk. Mostly it’s shrinks and NAMI mommies and other “sane” folk praising the drugs. The “sane” are one side. The “insane” on the other. As long as all say the same thing the media love to let the “other side” talk.

Report comment

Amie disagrees with her PROFESSOR [a tenured layabout]. She is told she is ARROGANT.

Bella disagrees with her LAWYER [a self-serving manipulator]. She is told she is ARGUMENTATIVE.

Caprice disagrees with her BOSS [a run-of-the-mill paper-pusher]. She is told she is a WHISTLEBLOWER.

Dolores disagrees with her CITY COUNCIL [six well-intended civic-boosters]. She is told she is an COMMUNITY ORGANIZER.

Evangeline disagrees with her FEDERAL GOVERNMENT [400-600 educated and accomplished legislators]. She is told she is a POLITICAL ACTIVIST.

Felicity disagrees with her DOCTOR [a socially-elevated drug-dealing barber]. She is told she is MENTALLY ILL.

Report comment

Sticks and stones can break my bones but names will never hurt me… What we are inaccurately called only matters if it is then considered “science” or worse, law.

Report comment

The alcohol crashed the car, it wasn’t my fault. I can’t use that excuse? But i can say alcohol saved my life?

Report comment

Yeah, we can say whatever we want but if the law disagrees we have a real issue. If “science” disagrees, we have a social issue because “science” is waaaaay more political than people would like to admit.

Report comment

Good article. Thanks.

The question, of course, is what on earth is meant by the phrase “saved your life.” Imagine a world in which there never had been any psychotropic drugs. What would people say about persevering through challenging times? One might say that a good friend “save my life.” Another might say that improving my diet “saved my life.” Yet another might say that more consistent and better exercise “saved my life.” Instead, we live in a world in which Big Pharma and psychiatry have colluded to create and distribute neurotoxic drugs to which people then ignorantly ascribe their happiness and well-being: Neurotoxic drugs “saved my life.” Damaging psychiatric labels and involuntary incarceration “saved my life.” A pseudo-scientific, drug dealing psychiatrist “saved my life.” Give. Me. A. Break.

This is the key sentence in your article: “What we do know is that once someone’s life is destroyed or killed by psychiatry, they no longer have the voice to testify.” There are many reasons for this. A couple of these reasons, as you mentioned, are that a person may be killed or maimed in such a way as to render them unable to testify. Nevertheless, the blood of the innocent cries out from the ground for justice, and the groans of the wounded ascend to heaven where God in His mercy groans with them. It may be, however, that the more prevalent problem is that psychiatric survivors DO have a voice, and they DO speak… but NO ONE LISTENS. Even Mad in America, a supposedly “critical psychiatry” organization, is not really listening.

Why is this? Because only psychiatric survivors really know what is going on from the inside. If psychiatry is a pseudo-scientific system of slavery that is destroying the lives of millions of innocent people (AND IT IS), but the vast majority of people still believe that psychiatry is a field of medicine that helps the “mentally ill” or “saves peoples lives,” how will this racket ever be exposed for what it is? It is more nefarious than chattel slavery in this way, because at least it was apparent to all that slavery in the South was wrong. Southern slave owners might even be stung by their own consciences from time to time. Not so with psychiatry. Under psychiatric slavery, many of the slaves believe that the slavery is saving their lives, and many slave masters are praised for their benevolence – assuaged by their own conscience that they are providing a needed service for humanity:

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.” – C.S. Lewis

Of course, there is nothing remotely “medical” about “meds.” The word “meds” is a euphemism for a dangerous neurotoxic drug. Just because hoards of people have been deceived by psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry does not mean that their lives have been saved by these “meds.” In fact, the best way to destroy lives and make people slaves is to fool them into believing that they are free. Psychiatry either forcibly removes liberty from people or it deceives people into willingly surrendering their liberty. Many people willingly surrender their liberty with a belief in the false notion that psychiatric “meds” will heal them. Either way, psychiatry robs them of their liberty.

Psychiatric “meds” DO NOT save lives. They fool people into believing that their lives are being saved while simultaneously robbing them of the liberty and the means to persevere through difficult times. This is just one of the many reasons why the dragon of psychiatry must be slain.

Report comment

Well put Slaying the Dragon. Don’t you think the term “meds” came about with psychiatry because medicine is so obviously an inaccurate term? “Meds” is a euphemism, and feels a little less dishonest than medicine somehow.

Report comment

Thanks Chaya. Good point. Since psychotropic drugs are so obviously not “medicine” or “medication,” someone must have thought that a more subtle euphemism would be “meds.” What on earth are “meds”? Are they “medications”? No. Are they “medicine”? No. They’re “meds,” or in other words, brain destroying, neurotoxic, psychotropic, thanatophoric chemicals. It’s still dishonest and misleading, just like everything else in psychiatry. But we’re talking about a pseudo-scientific system of slavery that is so deceptive that euphemisms like “emotional lability” are used to cover up murder.

Report comment

The term “meds” evolved to get away from calling them “drugs”. It’s been apparent from the first that these drugs were in a different category than normal medicine, and the fear of people creating an analogy (essentially correct) that these drugs are not dissimilar to street drugs. So we call them “meds” to make it seem like it’s somehow different.

Report comment

Steve, yep. I’m glad more and more people are calling them drugs lately.

Report comment

When I first was told about them in the 90s, it was always, “the medication”.

Report comment

No because patients have “brain diseases” and “medicine” is too long and complex a word for our diseased brains so they shorten it to an easier word, “meds.” Simplify it for us simpletons. Or maybe for the junior staff who cannot possibly memorize “medications” either.

Report comment

Hadn’t thought of that one Julie.

Report comment

That’s why the CV sheet we have to sign when we are admitted is colored differently. Ever notice that? It’s not for OUR benefit. It’s for the junior staff to ensure they know which paper is the essential one we have to sign No Matter What. We have to be coerced into it No Matter What. So because they can’t be trusted to memorize “conditional voluntary” written on top of the page, the paper is colored differently. After all, cumulatively speaking, the staff are far less educated and less intelligent and far less insightful than the patients.

Report comment

Slaying the dragon, yes, you’re right. It’s still dishonest and misleading.

Report comment

Slaying_the_Dragon, there were slaves who felt they needed their masters to “take care of them.” These condescending jerks told their chattel over and over how helpless and stupid they were, how they were not as smart or resourceful as “normal” aka white people and needed to be cared for.

Abuse comes with slavery. Emotional even if no whips and chains are involved.

Psychiatry is not only emotionally abusive in its own right but it encourages this abuse in family, coworkers, friends–while you still have some–and society at large. Then they marvel at how all “bipolars” and “schizos” suffer from low self esteem. Must be a symptom of the “illness” right? 😛

Report comment

Internalized oppression.

Report comment

I beg to differ. I have been emotionally abused by psychiatrists, by nurses, by various other “staff,” and by all means by therapists. I have been worse emotionally abused by mental health professionals than by any other people I have ever come into contact with in my entire life.

Report comment

Yes – they often see themselves as the ultimate arbiters of who their patients are – i.e. are they okay or not – and of course they’re not, because otherwise they wouldn’t have come for “treatment.”

I had one therapist tell me (on our first meeting) that I don’t love my kids unconditionally and that if I don’t fix that, they’ll be going to therapists 20 years down the line. She also told me that my idea of wanting to become a therapist myself (because I knew I could do what they were doing so much better and with less damage…) was a waste of time because I lacked charisma.

But who can understand the ways of Providence? When I recall that, I recall too telling that to my father, with whom I have a very problematic relationship, and him telling me that he thought I had a lot of charisma. Coming from someone who spent most of his life putting me down, that meant a lot. So everything can be mined for the diamonds, I guess.

Julie, where do you get your strength from?

Report comment

Gabi, That is a funny question. I am proud to be alive in spite of psychiatry. I am alive because I refused it. I am alive because of noncompliance.

My mom taught me something when I was a little kid. She said if you ever have a difficult problem to solve, you can solve it! Just put on your Thinking Cap. She said everyone has a Thinking Cap. But we have to remember, she said, to put it on.

Psychiatry tells us we do not have Thinking Caps. Psychiatry tells us we have to rely on Them for all our needs. However, if we rely on them, we will fail, over and over and over. This is because they are unreliable. What happens is that we end up terribly disillusioned by psychiatry, and subsequently we might feel disappointed in humanity in general. But the beautiful thing is that we then might fall back on what is left–ourselves. Lo and behold, we might dust off our Thinking Caps.

We all have one, and we can put it on and use it anytime. My mom was right! It costs nothing to use it. It is magical and amazing. Put it on and you can do just about anything.

Report comment

How unconditional is your therapist’s love for you? There’s a good question.

Someone who pretends to care about you for $50-100 an hour.

I remember crying to myself in pain/loneliness once as I realized only one person was willing to talk to me and treat me kindly. And she had to be paid to do this. 🙁

Report comment

I agree they themselves are the most emotionally abusive. But they encourage others in the life of the designated scapegoat of society to view the scapegoat with fear and loathing. The psych system’s role is similar to the one a “narcissist” plays in a dysfunctional family drama.

Report comment

I had a narcissistic therapist. That was hell. The whole time I saw her was hell on earth. I remember leaving Maria’s office feeling like I wanted to kill myself and wondering why.

Maria was controlling and abusive. She used to accuse me of vomiting over and over and I never vomited. She told me she was arranging for me to go to the State Hospital.

After I was deprived of water at Massachusetts General Hospital (which is TORTURE under any law in any country!) she told me the “unit” was on did not exist and that I was totally psychotic and it never happened. Then she claimed this meant I needed the State Hospital even more. She pushed for it harder after that and threatened me at every appointment.

That woman should not be licensed and in fact I think she should do prison time even though I don’t believe in prison really. I HATE WHAT SHE DID so much. I hate what she did to me and I hate what she did to all her patients because in my heart I know I was not the only one. One of these days she will have a suicide on her hands. I pray this doesn’t happen but I see it as inevitable and I pray she gets nailed for it. At least.

Report comment

I’m kind of feeling a lot of hatred towards Elyn Saks and her book ‘The center cannot hold’ since she said exactly what everyone wanted to hear:

1. Psychiatry is cool

2. I’m sick bad person

3. I should always take my drugs

Then it becomes a best-seller, everybody happy – poor bad ugly creepy schizophrenic

Now let’s say someone writes a book with opposite view, today, in 2018 – how many would seriously read this?

I’m the one btw who currently takes the drugs – I took low dosage of anti-depressant, mine is helping me with anxiety. Antipsychotics made me fat, slow, without ability to experience emotions and/or imagination. They made me suicidal – but I don’t believe that this is somehow drug problem, in my case life become so shitty – you couldn’t bear it. Lithium is something disastrous – goodbye, kidney, goodbye, liver, goodbye thyroid.

Report comment

Thanks Igor. I never felt good about that book. I heard rumors it was sponsored by pharma, like they paid her to write it, though I don’t know for sure. I wouldn’t be surprised though. Even the phrase “my drugs” or “my meds” bothers me because people identify with them as “theirs” which doesn’t seem healthy, like it creates an attachment.

Report comment

It’s funny how people talk about pill shaming. They see the pills as an extension of themselves–like they have no personality/conscience/soul without them. Part of what made me grow to hate the drugs was not just how stupid and awful they made me feel but how the “experts” around me told me I would be a murderous sociopath/rabid dog without them. I found the whole idea dehumanizing and good for producing existential angst that frequently led to contemplating suicide.

Report comment

I really enjoyed your perspective on this subject. It’s one that I’ve stewed over a lot.

I start to get itchy when people oversell the idea that depression and anxiety have a ton of stigma (ALREADY!)–as a response to conversations around iatrogenesis–when almost every trendy Youtuber is being sponsored by Betterhelp and talking about their “mental illness” of anxiety and depression. I don’t think there is no stigma towards neurodivergence (“mental illness”), but in comparison to iatrogenisis– along with the glaring absence of all attributes of societal acceptance and support– Like I said, I get itchy.

I guess in a way it’s frustrating that in speaking out about iatrogenesis is necessitates a conversation about necessary use of meds and where the government should draw that line. Some days you just want to say fuck these drugs for the life and body disfigurement and not run it past anyone’s filter. Thank goodness for support groups.

The candy bar analogy was spot on for people who can bare to live chronically on these drugs. Great piece!

Report comment

Thank you Ally! I’m curious, do you think the term neurodivergent is meaningful or accurate? To me it sounds like yet another euphemism, that may or may not mean anything in particular. Perhaps some people identify with it, but without a set standard for “normal” or “mentally healthy” I’m not sure how we can even know what neurodivergent is. And more importantly, I don’t want a standard for mentally healthy as I think it would severely limit creativity, connection and healing.

I totally agree with you about iatrogenesis and how little social support there is, how few people even know about it or understand it, even now.

Report comment

When my relationship to these ideas began (in benzo neurtoxicity) I thought the method of ingroup/outgroup, mentally healthy/mentally ill categorization was all wrong. And based on the paradigm of pathology I still do.

I think it wasn’t until my friend was horrifically manipulated by a person who could easily be diagnosed with NPD– that I’ve become more flexible with yes, unpathologizing personality disorders and giving them a label that is more based in biology. I just can’t read what I’ve read about the personality “disorders” and think that there shouldn’t be some type of labeling for that. Particularly NPD, APD. Neurodivergent was a word that I heard some people in the community use and it seems more appropriate than mentally ill. Happy to hear another perspective though. There is still so much reading I haven’t been able to do because of this brain injury.

If people see the world in a hierarchy where they are on top and others are below– and that is built into their programming, it seems almost irresponsible not to have language to represent that. Just like with anything, i think there is a spectrum of experience and some who have these experiences can carve out some self awareness– but many can not. Listening to the stories of many children with parents who are diagnosed with NPD is pretty heartbreaking, and I found that I couldn’t tease out this awareness from my beliefs against having a standard of mental health… or a state of being neurotypical.

I suppose I was wrong to use neurodivergence to describe depression and anxiety. I do like it better than mentally ill as an overarching term.

Report comment

The worst example of narcissistic behavior that I have seen recently was my therapist that I had between November 2010 and around March of 2012. I was total hell having her for a therapist. She had a Savior complex and was very controlling and manipulative. She regularly threatened me and falsely accused me of all kinds of things, whatever she felt like accusing me of. I am horrified that she still practices therapy.

Still, on principle, I don’t call people narcissists. I say, “narcissistic behavior.” I don’t label others. Much as I hated Maria’s behavior I will not label her. I know in my heart that what she did was criminal. It was abuse. It was not a disease and I will not excuse her abuse by claiming it was a symptom of a disorder. She should not practice therapy until she can work out her control issues. I hope she reads this and wises up.

Report comment

Thanks Ally. I see what you mean in a way, because sometimes when I have been abused by family members, or others, I have had a strong need to label them somehow. I often go to, “they are a bad person”, which is interesting because I never used to believe people could be inherently bad.

I still don’t actually believe that people are simply bad. Abusive people became that way for a multitude of reasons, yet sometimes I just want to call them bad, because they hurt me so much and analyzing “why” they did so puts me into empathy and considering their situation instead of my own. For me this is usually not healthy at all.

If I decide they are bad people, I can simply stay away from them and focus on bettering my own life, healing and not being abused anymore.

So I think there’s a time and place, especially for those who were conditioned to be empathic, to simply label another person. It doesn’t mean they necessarily have an intrinsic disorder or that it could never be reversed, but it can be a good protective instinct, and a reasonable prediction. People can change, I believe, but after a certain point, I’m not holding my breath, and if I were to do so, it would make ME crazy.

Report comment

Chaya, just one little point. If a person is truly starving then you’d better not give that person candy. This, sadly, was a misunderstanding when the American soldiers came upon some starving Holocaust survivors. In their zeal to get them fed, they gave the starving survivors chocolate. The survivors died.

What happened? When you overwhelm a starving person’s system with candy or chocolate after prolonged starvation, sometimes a condition called “refeeding syndrome” can develop. Usually, once it starts, the condition worsens and the person dies. It is very complex and serious, involving edema, heart failure, diarrhea, and physical lethargy. It is very hard to reverse refeeding syndrome. But the soldiers didn’t know that this would occur.

Nowadays, refeeding syndrome almost exclusively occurs in ED treatment facilities when patients are tube fed too rapidly. This is a huge liability risk for these facilities and they are truly scared that patients will develop it.

All I am saying is that candy is not an answer to starvation. It isn’t that it is unhealthy food, it really can kill a starving person fairly quickly. As for helping for weight gain for a non-diabetic person who isn’t starving, it might help, but you might get a stomach ache.

Report comment

Thanks Julie, good to know.

In emergencies, with people who have health challenges, psych drugs can also instantly kill them such as in this case:

http://www.theolympian.com/news/local/article198930799.html

Report comment

Candy can save the life of a diabetic going into shock. But follow this analogy and you’ll realize type 2 diabetes usually is related to an unnatural diet high in refined sugars and other stuff.

I continued taking psych drugs for more than a year after making the decision to quit. In my case going cold turkey might have killed me from the shock my system would have gone through.

Report comment

Ms. Grossberg, nice job.

I was part of the “bipolar gold-rush” of 2004; presented with financial stress, a fight with my mum, and insomnia, no DTS/DTO. 30 minutes later I was bipolar-1-for-life and’ Seroqueled’ to my knees, an NMS reaction and my future for the next 11 years. Lost my custom beach house of 12 years (current mortgage and auto) and bankrupted (my first and last); couch surfing at 55 years old…not a good look. Lost my ‘good’ insurance because I couldn’t work from brutal side effects (you know, ‘my’ worsening SYMPTOMS). Certified SMI by the Medicaid marriage counselor (Yikes).

After another NMS AND anaphylaxis (they gave me the same drug twice over my objections while in full decomp), I forced the meeting with a doctor (hadn’t seen one in 7 years). He was on the fast track for CMO and took me as his ONLY PATIENT (after all, there were liability concerns) for the next 2.5 years to 1) ensure I was who I said I was 2) titrate me safely off of the neurotoxins 3) vacate my LIFETIME bipolar diagnosis AND decertify the SMI. (Yes, I am a unicorn)

It seemed a small balance of justice ; MY trifecta for theirs; gaslighting, fraud, and greed…not to mention 11 years of an adult dose of suffering (a new word for my vocabulary). I ‘have my papers’, like a Jew in Nazi Germany.

As you all know, I represented a revenue stream, job creator, and practice builder-my diagnosing dr. is in “Dollars for Docs”, Propublica.org, racking up $65,000 plus annually, a mid-size C-Class Benz, mostly from Astra Zeneca-Seroquel!) Big fan of irony. The only challenge they faced was keeping me, the ‘host’ alive while feeding me the drugs. I was of no use dead. It was a close call at times.

I’ve rebuilt since 1/2016 with the usual; tai chi, acupuncture, some Charlotte’s Web, &and great nutrition. Everything is getting better …except for those pesky random, little seizures (7 so far). They didn’t ‘show-up’ on the 1st tier of tests with my new neuro; he is uncomfortable and losing interest, telling me…u guessed it..”anxiety, dear, go see a shrink”.

Sweet Baby Jesus.

Report comment

Stella your neuro was likely projecting. Ask him what he was so anxious about…..

Report comment

Ms. Green

He was uncomfortable because psych drugs are outside of his sphere…ALL drs are loathe to say “I. Don’t. Know.”

I had brought him 5 clinical, credentialed articles on neurotoxin damage, specifically anti-psychotic short-term use resulting in known damage…shrinkage of the pre-frontal lobe. Ruh Roh. I took them for 11 years.

He gave me an earnest little dr frown & nodded ‘thoughtfully’. In the south we say to that flavor of bs….’Bless your heart’.

I’ve already reached out to some MIA experts for a more forward-thinking, informed, & open-minded neuro in my metro area. Hopefully they can point me towards an enlightened soul.

Regardless, I’m “Ride or Die” (more irony) to protect & heal my brain, in light of the misplaced trust that “we” paid dearly for.

I am relentless…it’s how I ‘self-rescued’ in a very hostile clinic system. I was APPROPRIATE but absolutely relentless…dealing with caseworkers with hi-school equivelancy certificates….again, Bless their hearts”…and I was drugged & decomping.

RAGE AND TERROR ARE MIGHTY MOTIVATORS…you know, Fight or Flee….but I needed those papers to spare the paranoia of anything ,going left,….the rest of my life….and hearing those damning words “she,s off her meds’, regardless of my happy stable life.

It can bite u bad.

Report comment

Stella, I’m curious what you mean by “Charlotte’s Web.” Do you find the book or movie/s inspirational? Or are you referring to something in the book?

Report comment

Ms. 777, The hybrid hemp derivative, “Charlotte’s Web” developed by the Stanley Brothers/Denver. It is chock full of cannabinoids that our bodies produce on their own; only trace THC (the ‘get high’ part of weed). This is a supplement, carefully grown and ‘processed’, organic and no pesticides. It is restorative, calming and neurotransmitters love it. There are ‘other’ brands out there now; I know that the Stanley Bros cultivation and processing is safe.and pure.

I researched it in 2014 when it was illegal but allowed to be tested on tiny children with a particular virulent form of epilepsy; 300+ seizures A DAY. It was rare as gold and illegal (federal) to ship anywhere, at that time.

Since the assholes were shoving anti-convulsants down my throat (with everything else), I was very curious about the effect that The product was having on seizing brains…and ones so delicate as children’s. NO SIDE EFFECTS. NONE. I was on a waiting list for alnost a year.

Sanjay Gupta, the CNN Doctor/Neurosurgeon/Emory (who didn’t approve of ‘pot’) started researching it’s qualities and affects on these suffering children and their frantic parents. He made the now famous “WEED” documentary (CNN) and subsequently there is a “WEED 2, 3” and soon 4. It is a revelation and a game-changer.

If you are ‘one of us’, I think it’s an eye-opener.. and it made me weep not just for those little babies and their parents, but for the hope it suggested for my damaged brain.

I use it when I can afford it; I started with drops and now they have caps. You can ‘vape’ (no) and they have topical cremes In most states, I don’t believe you need a ‘card’ or scrip. Dispensarys often have it in a foyer where credentials are unecessary…and now EVERYBODY has it.

“Realm of Caring” or ROC is their website or Google “Charlottes’s Web”; the name is after Charlotte Figis, the first little girl that was on the ‘treatment’ and her remarkable story; “WEED 1”. There are now thousands of children leading better lives. PTSD, Alzheimer’s, dementia, and NFL players use it; not for their aches and pains; food and protection for their brains. Why not ME…ESPECIALLY ME?

I did my homework concerning my neuro-transmitters, synapses, dopamine, and GABA…and what CANNABINOIDS can do for them. Swallowing another pill was not in my plans after I ‘escaped’. I was cautious, but finally completely convinced. This is not a silver-bullt. You won’t ‘feel’ it ‘come-on’ like the drugs. Steady, consistent use (I feel strongly) helped me recover laser focus, nimble vocabulary-once lost, and a positive/curiosity/perspective to healing. And by the way, if that’s a placebo effect, that’s fine. I know I felt better much quicker than I had any reason or right to. My goal in 2016 was not drooling in public and keeping the tardive eye open. I don’t have to concentrate when I stand up. I thought I would be more broken down. I’ve been clean from psych drugs for 2 years now and I HAVE taken very gentle care of myself, feeling whatever I wanted to and being especially ‘expressive’.

YOU WON”T GET HIGH…(and no thank you), the cannabinoids will restore and feed your brain the way pure oxygen is restorative to cells and transmitters, only better..

The website is full of interesting info…but watch WEED 1 &; 2. It’s all there. Stream it, rent it, buy it. Knowledge is power.

BTW, JOHNS HOPKINS THINKS ENOUGH OF IT TO HAVE RUN A TRIAL FOR THE LAST THREE YEARS…I’M IN IT (there are no ‘freebies’, sigh)…I HOPE THE FINDINGS WILL HELP OTHER PEOPLE LIKE US. I want others to get away alive and well.

Here’s the PUNCHLINE…IT’S SCIENCE… that rare commodity in this ‘thing’ of ours…and it’s been around (medicinal hemp) for centuries.

And of course the only obstacles for more use and insurance coverage is PHARMA and their choke-hold on Congress.

The website told me that the feds are causing shipping vendors to ‘slow=route= the purchases now. My last order was ‘routed’ all over the US. They are trying to force the Stanleys out of business to make room for THEIR future product. Buy it local (assuming you can). Watch out for imitators…and Good Luck.

Report comment

Thanks Stella. Thank you for sharing your story and what has helped you.

Report comment

Heroine and LSD haven’t been credited with saving lives. But Big Pharma doesn’t endorse them. They view them as invading their turf!

Report comment

Rachel, definitely. They view marijuana as invading their turf too, and even herbs and supplements, trying to make them seem illegitimate or unscientific, when most of them are far more scientific and safe than their drugs.

Report comment

The Neurotoxing pHARMaceutiKILLING “Mental Health”/Pseudoscience Psychiatry AND Their Neurotoxing “Psyche Meds” took my “life” away slowly starting at age 16. The first “anti depressant” I was on (Imipramine) I just found out this last year can cause Psychosis. The pHARMaceutiKILL Merygoround of “Mental Health’s” LIES and Multiple Neurotoxing “Side Effects” for (too) many years until two years ago when I “woke up” too the Cheap Car Salesman Lines from the “Mental Health” Predators and stopped taking Their Neurotoxins. Unfortunately by Cold Turkey. I already knew through the last two rounds of meds I was getting damaged and losing my “life” and health even more every day. Medical Arrogance, Ignorance and Hostility I’ve experienced for Years when I’ve wanted/spoke for “Alternative” HEALING including Today. Every day from The Skanks and Their Skank children/friends in communities I’m in. Medically ARROGANT, IGNORANT and HOSTILE Predators. Or SKANKS for short.

Report comment

Thanks Huami. Guess I’m preaching to the choir here. I thought I’d get some push back on this one.

Report comment

Thank You and loved the article, btw. I’m working on the “candy bars” and Nicotine. A bit more time.

Report comment

What is mentally healthy in one culture is considered out of the norm in another. For instance, my parents were like other WWII parents and did not share emotionally with us kids. This was the way that parenting was done back then. By the time I got to therapy, my therapists came from the next generation, so they claimed my parents were “emotionally distant.” This was not true. They were most likely warmer emotionally than most parents of that generation. Therapists compared our parents to theirs, and any variation was by definition “abuse.”

Report comment

Excellent points Julie.

Report comment

what was the zine that you were submitting to?

Report comment

Janehhhh, It was a local zine that doesn’t exist yet, so I’m sure you wouldn’t have heard of it. I’m not trying to demonize the people making this zine as I don’t know them at all. I might even like to get to know them, and know better their intentions.

I used this as an example, because it prompted these thoughts, but I’ve heard similar words so many times, that the zine person was just another person saying the same party lines as thousands of others.

Report comment

This article is so wonderful and, “in my opinion,” desperately needed for today’s society!

I would quote the most salient parts of it, but I genuinely feel every word of this needed to be said.

I’m a little shocked I haven’t heard the phrase “psychiatric medication saved my life” discussed from this perspective before. I have had this phrase used against me, about me, about others, and as a general “end of story” in some of the strangest and most stressful conversations I have ever had. I think it’s clear that you’re right in pointing out that this perspective has a very loud and well-established platform already, one that often silences criticism of psychiatry, by hiding behind what seems to be both a scientific AND a personal statement about psychiatric drugs.

After all, when someone says these drugs saved their life, what decent person can “argue” that it’s not true? If someone were to say that psychiatric drugs destroyed their life, however, I’ve seen it’s generally well-accepted to argue against that statement.

Also interestingly, you bring up how street drugs can possibly be credited in saving lives this way. I feel this way about my own experience with non-psychiatric drugs, and I know others who do too. (Interestingly, none of us feel that they are a first or even second best option for dealing with distress; me and the people I know are all pained to remember how desperate we were when we turned to them.) That subject also seems foreign or irrelevant to some people when brought up in these contexts, but I deeply appreciate that you’ve mentioned it here!!! Hopefully in the future, people will generally be less skittish in discussing the nuance involved in the topic.

The movement for a (any) solid and established alternative to psychiatry is definitely still young, and articulate pieces like yours bring us all forward.

Thank you so much for this article; on a personal level, it’s soothing even to read it and know that there is understanding for this perspective.

Report comment

Great article Chaya,

Real reporting allows for opinion and experience.

No zine should do one sided reports.

In fact, when one is distressed and given drugs and the distress lessens,

some might believe it was due to the drug, yet we know that moods and thoughts

ebb and flow.

The spell binding happens when one’s mood naturally changed, and we give the drug credit.

Then the mood changes back once again, at which point, more meds are added.

In theory, if it was the first drug that caused a shift into better mood, there would be no need

to add more drugs.

People will keep having ebb and flow, wax and wane even while on drugs, so why bother at all?

Just to have numbing where numbing has a negative outcome?

Enough people have come to the realization that these chemicals are harmful, and do not “save lives”

Psych always has new clients, but with ALL, eventually they come to the truth, and the truth was not a “mental illness”. The truth was not the chemicals.

Report comment