Ideas of mental illness carry a lot of presumption. Namely, that someone acting a particular way is sick—their mind has the flu. Plenty of thoughtful people have pointed out that what we call the mind is at best a metaphorical concept, and that metaphors cannot have health. I wholeheartedly agree.

Yet, clearly something unusual is happening somewhere if I start believing I am being poisoned despite evidence to the contrary, or—as in my own experience—I think people might be behind mirrors nefariously watching me. For a time, I believed that theorizing about “what’s happening” during these experiences was in itself a problem because theory often shuts down intuitive, heartfelt responses by others, and narrows meaning-making by oneself. If I see you as delusional, I’m not likely to connect; if I see myself as delusional, I’m not likely to investigate further.

So, I’m weary from the outset of the question: What is psychosis? Or: What is (insert preferred term for the aforementioned experiences)? It’s a minefield, and I’m convinced there is no unifying theory that applies to everyone—just as there’s no unifying theory of love, joy, fear… other mindsets. And in any case, I wouldn’t be in the best position to create such theory if it were possible.

But I am certain that what we call psychosis is not a disease. I am certain of this because there are plants on the planet—hundreds, everywhere, for a very long time—that produce states of psychosis in their neighboring fungi, plants, bacteria, and animals (all of whom have serotonin receptors); states that are beneficial for the health of that eco-range. As such, the physiological process of psychosis—that of amplified senses—is ecologically purposeful. Not good nor bad (which are always context-dependent), but part of what Nature does trying to grow.

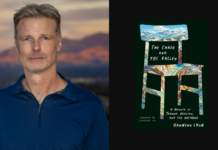

Last year, I wrote an essay called “To See an Atom” arguing these points, and earlier this year I gave the following talk in Boulder, Colorado exploring these themes.

In this talk, I explore how existing in an environment of dead things—as opposed to a living world who communicates—influences our current thinking about mind and mental health. Our houses are converted forests; our computers are converted mountains; our toilet water is a converted river. Much of the wild world is now a garden, and so a garden becomes the template in which modern people rap philosophic about the bounds of sanity. Because a garden is a rational, controlled space, any irrational, uncontrolled experience—including psychosis—will be cast from it. Yet if we step out of the garden and back into the old growth, I believe the process of psychosis belongs as part of Earth’s “will,” of her wild, and as such deserves a re-appraisal.

steven are there different causes of psychosis…

and are there different types of psychosis…

I thought we just didnt know the causes yet..

Report comment

The causes of psychosis are that we are psychological beings, there is just psychological necessity. The causues of normalcy is that apollonian ego called apollonian rational mind that way, the simplest antypsychological perception, out of touch with the reality of psyche means – normal. Everything which is PSYCHOLOGICALLY higher than simple apollonian RATIONAL ANTYPSYCHOLOGICAL perception they called ENEMY= mental illnesses. Mental illness means – we don’t wanna know what hides beneath our monicker because we are living from dehumanisation not phenomenology/empathy. The paid us not for empathy but for judgement and theological condemnation of evil in your brain. BU.

Everything which is beyond rational ego apollonian mind is Gypsy/Polish or Jew for authoritarians. What about pathological and psychopatic perception of the psyche -the psychopathy of apollonian rational ego – the advanced psychopathy/lack of wisdom of normal perception. THE PSYCHOPATHY OF NORMAL PEOPLE? James Hillman, RE- VISIONING PSYCHOLOGY.

If there was phenomenology of the psyche there would be no church, because church/theology condemned the death and the death is the psychological essence of the HUMAN psyche. Condemn the death by theology, call it evil and you could do hidden holocaust to those who symbolise it (psychiatry), and give death greater mening than the state/church. It is about give a meaning to psyche. And apollonian have stolen the psychic reality, the temple and build the prison for their own purposes -money.

This is inquisition, and psyche is the enemy of the theological state. Is psychosis normal? Nice question, especially when we ask in death camp for the psychological man.

Report comment

Hi,

The British Medical Journal published guidelines for Best Practice Assessment of psychosis as there are dozens of underlying medical conditions (including fatal diseases) and substances know to induce symptoms considered to be psychosis that can be misdiagnosed as a mental disorder.

Unfortunately, most medical professionals fail to test for underlying causes and instead rely on the rubberstamp labeling process of psychiatry.

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/bmj-best-practice-assessment-of-psychosis/

Susannah Cahalan, author of Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness is just one example of how individuals suffering from a very serious medical condition can be easily misdiagnosed by medical professionals

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/susannah-cahalans-revealing-tedxtalks-do-generic-psychiatric-labels-deprive-mental-health-patients-their-rights/

Report comment

While I don’t seek to deny your point – I believe that toxicity is very ofter masked by cover stories that include virological fears. So pesticides/herbicides and zika as a recent example. The stories that serve power will always dominate truths that dont.

While working within a framework of belief – one has to honour its experience as valid to the current definitions. But all frameworks of belief are stories by which we ‘make sense’ of our world and if they do not truly serve who we NOW accept ourselves to be, we have to question our presumptions and beliefs that before were invisibly running as acquired or induced habit.

Exposure to toxic influence links in with the undermining of the ability to heal and repair or regenerate. The synergy of co-factors in individuals may vary – not everyone accumulating aluminium via vaccines suffers arrested mental development of an ‘autistic diagnosis’ and incapacity.

To what degree are ‘diseases’ the result of the breakdown of health as a wholeness of being – and this must include the psychic-emotional and spiritual being.

Bringing in the realm of consciousness to the ‘physical’ condition is often associated with guilt, blame and punishment and part of the attempt to physicalize being is to ‘escape’ this. But we only reframe it in different forms of subjection that may mask over and protect the ‘disease’ from its cure.

Curiosity for truth is not a witch hunt for sins.

But the witch hunt of a blame culture does set the mind in wanting to believe what is not true so as to seem protected from feared outcomes or experience.

The attempt to escape a fear is what makes it real for us in the terms we set.

Many who have reclaimed a sense of their power to choose after having the experience of giving it away to ‘experts’ or beliefs that seemed authoritative, have lived through fears and shifted or grown by that willingness brought to adversity and conflict.

I see a toxic thinking and its toxic world as a call to wholeness or true presence – not as a struggle of powers, but as an alignment within the power of health – now and now.

Report comment

Yes “psychosis” can be natural, but it’s rarely psychosis.

Most of the people described as “psychotic” are not really psychotic but “bothered”, and anyone can find themselves in this type of situation. If a person were genuinely “psychotic” they wouldn’t be able to communicate with people that specialise in non drug recovery – would they?

I believe Dr E Fuller Torrey in contradiction to the Good Recovery Rates in Non Developed Countries, claimed that it was normal for people to have temporary resolvable “crises” in these countries. But, its normal everywhere.

Report comment

One more definition of “psychotic.” See why the term, in addition to being logically incorrect, is also essentially meaningless? Or, looking at it from another perspective, how it can mean anything you want it to?

Report comment

“..People hiding behind mirrors..”

A friend of mine was raised in a large 2nd generation Irish Family in the 1960s/70s in London, Uk. His father was having problems with work at the time, and my friend wanted to help his family, so he decided to steal some BREAD from the local bakery.

He got into the bakery but couldn’t find any bread, so he stole some CAKE – but he got caught on the way out, and was taken to the Police Station.

A social worker was called in, and the social worker wanted to find out why a child from a good family would break into a bakery to steal CAKE.

The Social worker put my friend into a room with lots of toys and a hobby horse and there was also a big MIRROR on the wall. My friend knew the Social Worker and a Psychologist were hiding behind the MIRROR, and he didn’t want to cooperate, but eventually his curiosity got the better of him and he jumped onto the hobby horse and started riding it.

Report comment

Poisoned – Its difficult for someone to seriously misbehave in normal society and get away with it. But there are plenty of people around, that could seriously misbehave if they could get away with it – this becomes evident in times of War or Society Breakdown.

Report comment

I can highly recommend ‘Breaking Down is Waking Up’ by Dr Russell Razzaque on this very subject.

Report comment

I attended a talk by Dr Russell a few years ago at Kingsley Hall. His message is one of Full Recovery.

https://www.rte.ie/news/dublin/2018/0616/971020-taoiseach-hiv-speech/

In the 1980s HIV was considered to be a “death sentence”. But people got together and followed what worked and now HIV is very treatable.

I think it’s unfortunate that a “Mental Health” Diagnosis can still be a “Death Sentence” even though there are plenty of Excellent Solutions Now available.

Report comment

It was better before the darned “treatments” existed. Before they came along 70% of all “schizophrenics” recovered. Now only 16% do. (My guess is the bar for recovery was lowered too.) Yet shrinks seem to think these odds warrant their so-called services.

Report comment

The reason the recovery level for “schizophrenics” is lower, since the “schizophrenia treatments,” the neuroleptics/antipsychotics, came along is because the “schizophrenia” treatments create both the negative and positive symptoms of “schizophrenia.”

Today’s “schizophrenia treatments” create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. And they create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” including psychosis, via antipsychotic and/or antidepressant induced anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

“Psychosis” may be natural, and is caused by natural things on this planet, as well as by the psych drugs, and their withdrawal. I absolutely agree, “what we call psychosis is not a disease.” I also agree, “the physiological process of psychosis—that of amplified senses—is ecologically purposeful.” Or at least can be. But only if the “powers that be” learn to listen to us “canaries in the coal mine” regarding the systemic problems within today’s systems.

Keep speaking out, Steven. Great video.

Report comment

By the way, I’d love to start a Soteria house in my area. Any good references or sources of information?

Report comment

Hi Someone Else,

Thanks for watching this video and for your encouragement!

When I was the project developer of Soteria-Vermont, I wrote a report that outlined the process we undertook to get one funded and started. It’s here: https://power2u.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Soteria-VT-Development-Report.pdf

Cheers,

Steven

Report comment

Hi Julian,

I got the book “Breaking Down is Waking Up” today, from Kindle for £5.03. I read through some pieces and the insights are brilliant:-

It looks Very Good!

Report comment

I just wanted to let you know that I enjoyed your talk. It was bonkers in a rather brilliant way and I wish you the best in your endeavours at Soteria. Standard approaches to madness are often stifling, mundane, and utterly lack elements of fun and frivolity: they try and take the madness out of madness. As you admit in the Q&A, there is no evidence-base for Soteria that persuasively indicates it matches or betters the traditional approaches, but I agree that people should be given a chance to make it through without kneejerk reactions to snuff it out. And there is something to be said for people that are willing and able to make some sense out of their experiences, and they should be given the opportunity to do so.

When you were talking about forest fires and their rejuvinative power I got to thinking about nuclear bombs. Nuclear bombs are also natural. Perhaps President Trump is right in his belief that it is pointless having nuclear bombs if they are never used. Perhaps the time will soon come when the rejuvinating fires of Armageddon will sweep through the world, offering it a new beginning.

Best wishes and please reconsider recreational fishing. It is torturing the poor little (and not so little) fishes.

Sincere best wishes and thanks for the stimulating talk. It was far more accessible than the essay you wrote and you make a lot of sense. I believe consciousness itself came about in large part because of hallucinogen consumption. And in some ways, a person describing a dream or an hallucinogen-induced vision or a psychotic vision or a religious revelrie would be indistinguishable from one another in the telling.

All in all, you’ve acquired a fan. Thanks for refreshing my mind a bit.

Report comment

Hi Rasselas.redux,

Thanks so much! And, “Standard approaches to madness are often stifling, mundane, and utterly lack elements of fun and frivolity…” Yes, yes, yes. Entirely sterile.

I’ll consider the request to re-consider fishing (though it will take a lot of empathy on my part to quit).

Cheers,

Steven

Report comment

Oh c. I thought the tv show perception was a really accurate way to look at psychosis. Umbdg

Although in the show my swt c dng he goes to hospital in crisis and this is not necessarily ideal each instance. M hdg be qit fk Everything to take care of self could be done at peer respite or also home. Sometimes a hospital stay may be what’s needed.

Report comment

But I am certain that what we call psychosis is not a disease

Sigh…who is this “we”? Different people use that word to mean a myriad of different things, mostly relating to what they consider wrong about someone else. “It” is a meaningless term describing a non-existent category, not a real thing which has simply been “misunderstood.”

As for what is “natural,” start with every feeling, thought and perception you have ever had.

Report comment

There isn’t a category for extreme pedanticism, but maybe there should be…

““It” is a meaningless term describing a non-existent category, not a real thing which has simply been “misunderstood.””

Clearly not a person that has ever experienced psychosis.

Report comment

No — but I’ve been so accused/labeled, and more than once. Not that this is in any way related to the point at hand.

Report comment

Anyway I’ll bite, I guess, i.e. try to rephrase/clarify: Whatever anyone experiences is their unique experience, with oodles of deep personal esoteric significance based on their life experiences, which are also unique. The fact that there are sometimes superficial outer similarities in two or more people’s style of expression, etc. does not mean that they are experiencing the same thing; they never are. So there is no true “category,” hence nothing to name.

Report comment

Which holds true for pretty much all subjective experience and thus, I expect, you are against any nouns which categorise a diverse range of human experiences which share common factors…

Let’s start with one, that neatly fits that description.

Dreams.

I take it you are opposed to “dreams” and “dreaming” for the reasons you have given?

I could go on but really you’re so determined to censor the language that your logic is often falling over the cliff.

Oops, I used a metaphor. I hope that isn’t triggering 😉

Report comment

While I get your gist with regard to classifications of symptoms I felt to write into the idea. The belief that ‘there is nothing true’ is the rise of social engineering or mind control ‘systems’ in place of true communication.

There are recognisable distortions of love (true) that may take any or many forms. In fact the attempt to deny, hide and coerce ‘negative’ or rejecting and conflicting thought and feeling into compliance or conformity is the presentation of or persona (masking/armouring) over love. So fear can and often does elicit fear, rejection can and often does induce rejection. That is – there is a vibrational or energetic undercurrent to the form of any reaction or communication that is both highly active and yet largely running unconscious to rules or conditional loves and hates that identify in manipulating or avoiding experience as associated with past conditioning.

Is most everyone having the same ‘human experience’ of thought-defined division, conflict, limitation, suffering and the movement to overcome, evade or mitigate suffering? But of course all in patterns of mutual shadow play – because we are all in a sense triggering and being triggered by each other rather? The negative communication of judgements, rejections, denials masked over with personal or social codes of mutual agreements, mores and rules is the human ‘doing’ of a mind attempting to be what I/we/you are not. Is this not because love believes itself attacked, unseen, and unsafe to be?

While we cannot have the same ‘experience’ we can be moved as one and in that sense the ‘separateness’ of a sense of control over a private reality is replaced by synchronicity in shared purpose – that is one mind and not many.

This is more like tuning into the same wavelength and not a unifying in the same forms as if to repeat or persist and protect a sense of fulfilment from loss or change.

When we are ‘out-of-true’ with ourselves we experience negative synchronicity. That is – synchronicity is the nature of the communication of a living Universe – but when we create or attract conflicting reality out from a sense of lack seeking to be filled, we do not recognize our own part and react as if it is all happening to us or being done to us which is a subjection or sense of victim.

While mind at the persona level seeks to manipulate form, the mind beneath of above that is operating as symbols and meanings of the natural unconscious spontaneity of the impulse of life – which is pure communication or the nature of life to ‘know thyself’.

In this view a true appreciation is uncover-able from mis-identified self-in-reaction, but in a sense the ‘treasure’ is guarded by perils or guardians – because the misplaced fear of and substitution for true cannot ‘do’ the uncovering of its own lack of true foundation in you.

The fear of ‘chaos’ is associated with loss of self-identity or exposure (and penalty) under an imposition or accusation of a false and hateful or invalid identity. This state is vulnerable to promise of protection by the power to limit and designate a socially valid identity that does mitigate a deeper fear by removing it from the realm of choice. If we are not ready to enter the territory of such choice it is not wrong to retreat to grow in the capacities that we can accept some responsibility in. However if the suppression of life as conflict is fed and suckled as a new identity, it will protect itself against healing – whether as the ‘patient’ or the ‘institutional therapy’. And so if life is felt as a call to joy and not just survival under fear, such identity has to be recognized and released or ‘walked out of’ in alignment with a true sense of self-appreciation.

When we let life or love in – we naturally find its extension to others. When we seek to possess or manipulate life, we meet the dissonance of a negative appreciation as a ‘chaos’ that drives an attempt to escape or overcome the effect or symptom – seen as ’cause’.

WANTING the ’cause’ outside ourself is fear of blame/avoidance of guilt penalty. But if that ’cause’ is in truth a MISTAKE that can be simply corrected – then all the layers of defences piled upon it are effectively a great diversionary tactic – charged with intensity and projected ‘meanings’ rising from giving power (energy and attention) to fear.

After writing this I shared a reading that included:

“The whole danger of defenses lies in their propensity to hold misperceptions rigidly in place. This is why rigidity is regarded AS stability by those who are off the mark”. (ACIM)

Report comment

I don’t see how this is related to my rather basic point about “psychosis” and other psychiatric labels. It may be in there somewhere but your posts are so long it’s hard to tell; you might consider condensing them.

Report comment

I take it you are opposed to “dreams” and “dreaming” for the reasons you have given?

Every dream is also unique. But dreaming is not considered a disease to be eradicated (though if you dream at inappropriate times it might be labeled “psychosis”).

The issue at hand, however, is whether any of these states of thought/feeling/behavior are “natural.” I would say they all are.

Report comment

RR, I guess dreaming is a “mental illness” the wonder drug Anafranil cured me of. 21 days of NO REM I recall. Maybe 8 hours of light dozing altogether during this period of time.

I became loonier than Minnesota in the spring.

But I mustn’t #pillshame by saying SSRIs ever do anything negative. 😛 Far better to punish and shame those who have reactions to these miraculous life-saving “medications.” Let’s #patientshame instead!

Report comment

Yes!

Report comment

CJ

. If somone in india is walking barefoot and speaking to god and the demi-gods,they are seen as holy men,

The same person seen in western states would be taken to be Psychotic and….

Report comment

Exactly.

Report comment

Either that, or a techy with some kind of a cell-phone hook-up.

Report comment

Also in India, there is a sect called the Aghori who believe that things which normally repulse are also of God’s world, and so they regularly cover their bodies in human and animal faeces, are often to be seen eating human and animal faeces, and are not unknown for fishing out a floating human corpse from the Ganges and eating it.

O those enlightened Aghori!

Report comment

Are psyches natural? That’s the real conundrum of psychiatry.

Report comment

If someone talks to God its called praying,If god answers its called schzophenia by psychiatric bull,

CJ

Report comment

What about a shrink who thinks he’s god? Society believes his claims. He’s “sane.”

If you don’t worship this self-styled deity you have anosognosia.

Report comment

It isn’t so much what he thinks as that it is supported by power given by many to a set of ideas that allow him to use that power in support of a personal sense of superiority.

Society isn’t really a single narrative ‘thinking’ entity and so it is the established and influential institutions that effect ‘power’ to change or maintain a core narrative AND in some sense enforce it.

So in psychiatric realms you have laws drafted, and educational curriculums imposed, services employed and ‘medications’ manufactured – all seeking a tool through which to operate.

Taking on the power in the world because it is ‘wrong’ is almost certainly unwise, but that does not mean we give it worth-ship. When we judge another wrong we take a superior position. So the energetic underneath the forms of a false or distorted sense of relationship is in a sense ‘contagious’.

I don’t mind what others think of me but I mind what I think about myself and them, because I find they go together. A degraded sense of self seeks ‘superiority’ or domination and control over its own projections. So I watch my own ‘projections’ because I love loving – and its a drag to get caught up in hating myself.

Society is perhaps shaped by what we give worth and power to. Most are running on a sort of default autopilot of ‘presumed’ or given reality. I feel that responsibility (not blame) is regaining the freedom to give love and attention to what is truly worthy and let go of focussing in what isn’t – and what I don’t want to keep recycling in my own experience.

I can believe others think all sorts of things, act as if they do and get reactions that seem to prove I was right. The mistaken idea of god is lording it over anyone or anything as a power trip. Power rests in its wholeness. So the word power as we use it is already corrupt – and that ‘power’ then corrupts – never mind absolutely.

But anyway you can if you wish psycho analyse the shrink.

No one IS their role. But when we are on a roll, we don’t want truth to get in the way of a good story. His story is then a denial of truth of himself others and a wholeness of being that is felt and shared in a living love.

Did you ever read of the ‘Thud’ experiment that revealed psychiatry to be anything but a science? This may have been part of what shifted them to a behavioural and ‘medical’ (sic) model.

Report comment

No. Where can we read about the Thud experiment?

Report comment

Rather than put a link I haven’t checked just put “Thud experiment” into a search.

I think I first heard of it in Adam Curtis’s Century of the Self documentary series.

“The Rosenhan experiment or Thud experiment was an experiment conducted to determine the validity of psychiatric diagnosis. The experimenters feigned hallucinations to enter psychiatric hospitals, and acted normally afterwards. They were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders and were given antipsychotic drugs. The study was conducted by psychologist David Rosenhan, a Stanford University professor, and published by the journal Science in 1973 under the title “On being sane in insane places”.

Report comment

A state of ease is not conflicted – but it may be unconflicted in dealing with something that presents itself as conflicted.

An original sense of dis-ease is nothing to do with diagnosis as given worship today – but of a loss of peace, a conflicted sense that persists or disturbs such as to interfere with or undermine our sense of self and life.

Nature is a term used for that which we live in and of. A divine nature or an original nature or a fallen or human or suppressed and denied nature – all invoke different facets of self-definition.

Often natural is equated with normal, naturally following from certain precepts could mean logical or inevitable. Nature can be blamed for our unwillingness to grow and thus attacked, suppressed and replaced by rules that rule us out of nature. Guilt can assign a holiness to nature by casting human as the murderer or despoiler.

Our development of consciousness is always relational and yet a sense of self is grown to some sense of independence within learned rules and roles by which to learn and participate in the human society – which is an inner modelling that augments a physical experience with meanings that support the world and the self that is its adaptation – for they are both grown together. When the learned self and world are interrupted and in some sense deconstructed to a sense of disconnected or conflicting reality, previously unconscious experience rises into consciousness or is triggered so as in a sense to replace it.

As part of the awakening from exclusive identification in the personality to a direct connection , communication or awareness of being, some chaotic and conflicted experience is ‘natural’ – but the judging of it as a distantiating from and suppression of disturbance by those who seek to rule out and escape their own, will tend to compound or reinforce the fears and guilt feelings of those labelled ‘sick’ or ‘mental’ even or especially when operating a mask of kindness. The discovery of our true nature is from the recognition and release of the false. Not from suppressing or seeking to invalidate the false nor seeking to force presumed good outcomes upon an unreadiness or unwillingness.

There are levels to our experience and within them we may accept certain premises for practical purposes.

If enough people are stuck at a certain place they call it reality. the human conditioning is generally suffered and accepted as the human condition.

Recognizing our true nature is not a thinking process nor an image or symbolic perception. Perhaps its singular feature is that it is not coercive upon you and in that sense not in or of the world that a love learned in fear at cost of simply loving.

The acquired rules for forms of loving and against forms of hate are a coercion upon the freedom to know and move as part of opening ‘otherness’ or relational balance. A world of otherness is part of the physical experience of separated or segregated ‘self’ or thought and experience as a private sense. There is terror beneath the fear of the pain and loss of such a self. Its revealing may be overwhelming to the capacity to maintain a world made to hide it. A sense of broken self reality undermines the movement to open in relationship. The thinking of the self cannot reinstate a sense of solidity and control without denying itself, and attracting or aligning in self-denying experience. But from a sense of consciousness in which there is awareness of choice, and some sense of causes and consequences to guide choosing, habits of thought and behaviour can b brought into awareness and find more alignment in a conscious desire rather than embodying acquired and conditional learnings that were part of the strategy of adaptation and survival at a time of needs that were incapable of articulation or reflection in consciousness.

I did not choose to accept psychosis as pertaining to me but I recognize that it would have been projected and assigned me. I hung in with the intuition of life and kept away from ‘authority structures’ that i did not have any sense of any capacity to understand – being predicated upon the self that rules out true knowing.

I may add that the opening of such a knowing – while in itself simply ‘Is’ – generated a sense of loss of self that became a desire to ‘regain or reassert my life and born identity. This precipitated a ‘descent into terror’ – to a world that became ‘solid’ again by some sense of a lie or deceit that I could not blame or project away from myself – and yet nor could I accept revealed truth. In simplest terms I was terrified of true intimacy of being and all my life to that point had been ‘running away’ but presenting as being or becoming a ‘someone’.

The quality of being that stirred could not be altogether lost – yet its prompt was always to look within at what I had run from. I look back at that period as a nine year phase of unlearning or growing willingness to both feel fear and abide through it to a willingness to move or act or relate in ways that grew a sense of self responsibility in place of self indulging thought and feeling. I could never ‘live up to’ targets that set me up to fail and I learned not to do that. Letting love in was the healing or shifting from a fear that opened the need to know to a supported and guided sense of being that of course is the true of me whatever experiences may come and go. I see it that the movement for healing and awakening from fear’s conflict and distorted filtering perceptions uses what is in our mind(world) to prompt and guide us to accept unified direction in place of ‘cancelling ourselves out’ in conflicting purposes. Feeling what we feel is a way to discern or open deeper understandings that are beneath the experience – but indulging feelings as self-reinforcement is a way to deny or block the influx of a greater or more integrated perspective. Perhaps we simply do not open to who we truly are until we know our own willingness, and whatever methods keep the borders, walls or lid in place are simply the means that was to hand in our own unfolding.

I could have chosen to feel psychically raped or violated – but I preferred to accept it a natural but somewhat premature – hence a crash course in the nature of being because I was in no way prepared.

Challenging the thought and beliefs of the world so as to reclaim responsibility for choice instead of giving power away may include psychiatry – but if you make an identity out of victimhood and grievance – you entangle yourself with what you hate. You cannot live anyone else’s life and projecting into them is really yours, not theirs anyway. To ‘not know is a condition open to receiving new light. To be certain in any negative or self-limting thought is to WANT it true. If you knew this was your choice, would you want it?

Certainty of being is felt and known in the wordless heart. Listen there by finding whatever works to release of calm the thinking mind. It isn’t really somewhere else – but that the mind is the seeming power to focus outside yourself and forget to check in.

I speak for an order that awakens within what seemed chaos rather than order set over feared or hated chaos. I may have grown in capacity to love (be with) but I am always a beginner – because those who think to know don’t listen. Without some stability we cannot focus – and so perhaps we go back to advance because to rush ahead of ourselves is to override parts of us that need a genuine acceptance in order to not seem to sabotage us in our desire or relationship. Not rushing – especially in an emergency is allowing a genuine connection to guide what otherwise is as likely to bark up the wrong tree.

Report comment

Maybe you could also mention that it didn’t take long for the real patients to find out about Rosenhan’s faux patients. They were aware of the difference, though they didn’t know why the fakes were hanging out on their ward- but they offered reasonable conjectures.

Report comment

My theory is that the patients saw each other as human individuals. The professionals mentally lumped them into the “Different Other” category.

Report comment

A Coda on the Churchill trechery .

The Congress on Eugenics led to renewed public pressure for Britain to adopt eugenics laws. In October 1912, Churchill discussed the proposed laws with Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who wrote in his diary: “Winston is also a strong eugenist. He told us he had himself drafted the Bill which is to give power of shutting up people of weak intellect and so prevent their breeding. He thought it might be arranged to sterilise them. It was possible by the use of Roentgen rays, both for men and women, though for women some operation might also be necessary. He thought that if shut up with no prospect of release without it many would ask to be sterilised as a condition of having their liberty restored. He went on to say that the mentally deficient were as much more prolific than those normally constituted as eight to five. Without something of the sort the race must decay. It was rapidly decaying, but could be stopped by such means.”[12] and now we have the mental capacity Act in UK,one HELL of a legacy.

Report comment

A psychotic state should be taken very seriously.

In 2013, Senator Creigh Deeds was stabbed by his son who was said to be in a psychotic state. His son then committed suicide.

Jared Loughner was considered to be in a psychotic state when he shot Representative Gabrielle Giffords in the head.

And sadly, Michael McEvoy was charged with killing Mozelle Nalan at Soteria House Alaska when he experienced a psychotic state.

Unlike any other condition, individuals who experience what can be considered a psychotic state can be a danger to not only themselves, but a danger to the health, safety and welfare of the public, which is why states sanction involuntary treatment.

What is being overlooked is the fact a wide variety of medical conditions, including fatal diseases, and exposure to numerous substances, including medications, can induce a psychotic state.

Something as common as the routine use of over-the-counter cold medicine can induce a psychotic state that is clinically indistinguishable from paranoid schizophrenia.

Anytime a commercial for a pharmaceutical product states the side effect of “abnormal behavior”, means the drug can cause the user to experience a psychotic state.

The British Medical Journal published guidelines for Best Practice Assessment of psychosis.

Because is is a natural response, no one is immune from experiencing a psychotic state.

If an individual is experiencing a psychotic state, and they appear to be a danger to themselves or others, they should be entitled to best practice standards of care and not just coercive psychiatry.

In order to fix our broken mental health care system, a unified advocacy agenda that will advance best practice standards of care is critically needed.

I would like to ask Robert Whitaker and every Mad in America writer one very simple multiple choice question,

If you experienced an extreme psychotic state, would you:

a) seek help through Open Dialogue or a Soteria House?

b) seek help through psychiatry?

c) seek help through medical professionals who will test for underlying medical conditions?

d) other, please explain

If you selected “c” for your answer, then start advocating for others to get the same treatment you would want for yourself

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/bmj-best-practice-assessment-of-psychosis/

Report comment

This is a joke, right? I think I get it, I’ll laugh just in case. 🙂

Report comment

Hello, and thank you for taking the time to read my comment, which is not a joke.

Please take the time and listen to Susannah Cahalan’s TEDxTalk

But for her parents being strong advocates for her health care, she would have ended up wasting away in a psych ward.

It was a neurologist who figured out the underlying condition of anti–NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis was causing her psychotic state.

For Susannah, it took only a relatively simple combination of steroids and immune therapies for her to recover from symptoms that were considered a severe mental illness.

Her doctor stated 90% of people suffering from the same disease are rotting away in psych wards and nursing homes.

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/susannah-cahalans-revealing-tedxtalks-do-generic-psychiatric-labels-deprive-mental-health-patients-their-rights/

Also, please take the time to listen to Robert Whitaker’s talk where he repeatedly refers to individuals suffering from psychosis as “crazy people” (starting at 23:00)

As a long-time advocate, my goal is to help all individuals considered to be society’s “crazy people” to be helped by recognizing the fact viruses, bacteria, brain tumors, dehydration, lead poisoning, an abscessed tooth, high levels of copper, etc. are known to make people appear “crazy” and get them help by treating the underlying condition, not drugging them with psych meds.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAy8IVvS_wA

Would you be willing to answer my question?

If you experienced an extreme psychotic state, would you:

a) seek help through Open Dialogue or a Soteria House?

b) seek help through psychiatry?

c) seek help through medical professionals who will test for underlying medical conditions?

d) other, please explain

Report comment

I hardly imagine that violence directed against innocent people, you’re “medical help” for people who haven’t been proven to have “medical conditions”, is the way to go. You are, aren’t you, in this case, calling drugs that cause serious bodily injury on top of abduction and false imprisonment, “medical help”?

Report comment

Hi Frank,

Thank you for taking the time to read my comment.

Have you ever listened to Susannah Cahalan’s TEDxTalk?

But for her parents being strong advocates for her health care, she would have ended up labeled with schizophrenia and wasting away in a psych ward.

It was a neurologist who figured out the underlying condition of anti–NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis was causing her psychotic state.

For Susannah, it took only a relatively simple combination of steroids and immune therapies for her to recover from symptoms that were considered a severe mental illness.

Her doctor stated 90% of people suffering from the same disease are rotting away in psych wards and nursing homes.

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/susannah-cahalans-revealing-tedxtalks-do-generic-psychiatric-labels-deprive-mental-health-patients-their-rights/

Also, please take the time to listen to Robert Whitaker’s talk where he repeatedly refers to individuals suffering from what is probably psychosis as “crazy people” (starting at 23:00)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAy8IVvS_wA

As a long-time advocate, my goal is to help all individuals considered to be society’s “crazy people” to be helped by recognizing the fact viruses, bacteria, brain tumors, dehydration, lead poisoning, an abscessed tooth, high levels of copper, etc. are known to make people appear to others as “crazy” and offer them help by treating the underlying condition, not drugging them with psych meds.

In the decision of Wyatt v. Stickney 325 F.Supp. 781 (M.D.Ala. 1971), a key issue was that patients have a “constitutional right to receive such individual treatment as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition.”

Because there are a diverse array of medical conditions and substances known to induce psychotic states, “medical help” must be individualized.

So people who appear “crazy” and test positive for dehydration, should be offered fluids.

People who appear “crazy” and have an abscessed tooth, should be offered appropriate dental care.

People who appear “crazy” and have lead poisoning, should be offered Chelation Therapy.

People who appear “crazy” because of a brain tumor, should be offered treatment.

People who appear “crazy” and have high Ferritin levels, should be offered phlebotomy.

People who appear “crazy” after taking a prescribed medication (not just psych meds cause a person to go “crazy”), should be told the truth and not be given more drugs to stop the side effects of the first drug.

People who appear “crazy” because of Creutzfeld-Jacob Disease, should be offered sympathy and prayers.

Do you agree?

Would you be willing to answer my question?

If you experienced an extreme psychotic state, would you:

a) seek help through Open Dialogue or a Soteria House?

b) seek help through psychiatry?

c) seek help through medical professionals who will test for underlying medical conditions?

d) other, please explain

Report comment

You say, “But for her parents being strong advocates for her health care, she would have ended up labeled with schizophrenia and wasting away in a psych ward.”

I was “labeled with schizophrenia and wasting away in a psych ward” as you put it.

Yes, there are medical conditions that are confused with “schizophrenia”. Then the question becomes a matter of prevalence, and whether that, a medical condition, is the individual’s affliction or not.

I have no problem with the word “crazy”. Etymologically it means “cracked”. There was once a magazine by the same name, “cracked”.

Here also you’re talking about “seeking help”, and that doesn’t respond to the complaints of people who have had unwanted “help”, which they didn’t acknowledge as “help” or “helping”, thrust upon them against their will and wishes. I’m saying that even if the person did have a medical condition, treatment should be that person’s choice, and not forcibly imposed upon him or her.

So here we go, I’m not speaking for people who are “seeking help”, as you put it. I’m speaking for people who were not “seeking help” in the first place, but found themselves locked up on a psych-ward anyway.

I could answer the question with d., but d. is so vague, and you begin your initial comment by attributing violence to so-called psychosis. By doing so, I assume that you approve of the “schizophrenia” label, and of incarceration/detention of innocent people given that label. To my way of thinking, doing so is a violation of due process of law.

Report comment

Frank,

I agree with you wholeheartedly and personally, I don’t have a problem with the word crazy either.

I do not approve of the schizophrenia label and I feel it should be abandoned.

Psychiatric labels are nothing more than descriptions of a broad range of thoughts, moods, behaviors, emotions, etc. perceived to be “abnormal”.

The state of psychosis is very real, and as we saw with Jason Russell, can be very extreme, happen very quickly and require intervention.

https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/video/kony-2012-creators-meltdown-caused-directors-outburst-15977342

I am also speaking for individuals who were not seeking help in the first place, but found themselves locked up on psych wards anyways.

It is the state that sanctions forced treatment, not me.

Therefore, the state has a duty of care to ensure doctors providing forced treatment do so using best practice assessment standards.

Instead, the states have empowered psychiatry to advance a one-size-fits-all medication management monopoly.

This is what I am advocating against.

Report comment

If there is anything we can agree on, there is still much we disagree on.

First, I think you’re stretching the meaning of “very real” a great deal if psychosis, as it often is, is seen as a “break with reality”.

Second, “requiring intervention”? Using those words I think you have just cancelled what you were starting to say at the beginning of your reply. I can’t stomach depriving people of liberty even after it has taken place.

Third, you say,” I am also speaking for individuals who were not seeking help in the first place, but found themselves locked up on psych wards anyways.” If so, you are certainly not speaking for me, and I’ve found myself on locked wards on multiple occasions.

Fourth, excusing the state for sanctioning forced treatment (i.e. deprivation of liberty) is as good as supporting it. I can’t humor such a viewpoint for ethical reasons, that is, I think people should play an active role in opposing such abuses of power.

The state should have a duty to protect people’s rights as citizens to freedom and independence from medical malpractice (false imprisonment, etc.), and that freedom should also include the right not to take neurotoxins if a person really doesn’t want to take them. Any neurological damage that should come of doing so aside.

Report comment

I have a real problem with anyone wasting away in a psych ward. Odd how many realize it’s wrong for Suzannah who had a real brain disorder. A physical illness not the metaphorical “mental illness.” Yet they’re okay with “schizophrenics” like Frank and countless other human beings rotting away in wards or being segregated/marginalized/etc. should they be released. I guess the “mentally ill” don’t feel pain like Real People. If they claim they suffer they must have Borderline Personality Disorder since pretending to hurt is an obvious attempt at manipulation. 😛

Report comment

Judging from your above statement, E. Causes you are not one of those “many” I mention. I want to be just. Still, there are those who think the “severely mentally ill” don’t feel pain or bleed red like Normal People.

Report comment

Encophalopathy,

I see that there is no other option so of course I pick C.

But I do so, realizing that just because medicine testing

does not come up with a cause, does not mean there is no cause.

Even to say the cause is “trauma”, is simply guesswork.

To advocate, lobby for more thorough healthcare is grand, yet then what?

If nothing physical is found, it is same old?

And what prevents psychiatry from NOT following a new and improved

model of identification?

What prevents them from labeling any deviation from “reality” a psychosis? One psychosis is like all psychosis? What prevents the same treatment plan being used for the tested positive/negative for some pathogen?

What prevents psychiatry from making up lies in the case where someone experiences psychosis from the very drugs they received for psychosis?

I know medicine itself is pretty limited and is one reason psychiatry and medicine became bed partners.

But the absence of not finding a pathogen does not mean it’s not there.

Report comment

And yet the overwhelming majority of people who are killed by someone else are killed by people who are not experiencing a “psychotic state,” and the overwhelming majority of people in a “psychotic state” never attack or harm anyone at all. People who use drugs and alcohol to excess, domestic violence perpetrators, sex offenders, gang members and wannabes, all of these categories statistically are MUCH more dangerous than “psychotic” people. Not to mention the professional business CEOs (like pharmaceutical companies) who murder millions indirectly and get off with no consequences. Raising the “dangerous psychotic” meme here doesn’t really hold a lot of water, because we know better.

I do respect, however, your statement that psych drugs and even non-psych drugs do cause violence at times, just like street drugs do. Unfortunately, the “treatment” for “psychotic states” is giving more mind-altering drugs to the people who are so diagnosed, which as I think you are intimating can actually increase the odds that they’ll do something dangerous. And when they do, lo and behold, it’s all blamed on their “psychotic state.”

Report comment

Hi Steve,

Thank you for reading my comment and taking the time to reply.

What you state is true.

Unfortunately, states sanction forced “treatment” or medication management for individuals labeled with psychosis.

If our states sanction treatment, it should be under best practice guidelines.

Please read my comment above and if you are willing to answer my question, I would appreciate it.

Report comment

I would probably start by researching myself and asking when this started and what set it off. The answer might be in the realm of the physiological (it started right after I took X, which can cause “psychiatric” symptoms), or psychological (it started just after an ugly confrontation with my mother in law) or a combination (I haven’t slept well for four days due to worrying about Z). It could be something altogether different that I am unable to imagine now. But I’d look for the source before I decided what to do.

Report comment

If it was a severe psychosis it would more often than not overcome you so intensely and rapidly you would be negotiating it with an impaired ability to rationalise, as you would be now rationalising within a severe psychosis.

A lot of the time it is concerned others who sound the alarm and seek help. In that instance a thorough physical assessment would be the best first approach at nailing things down.

But you have never suffered a severe psychosis so a little bit of naivete is inevitable.

Report comment

You are probably quite correct, and I did have that consideration that it’s possible I might not notice or might not have time to respond before I’d lost all touch with reality. Just for the record, I have never had any objection to people being offered genuine help in a respectful way. It’s just that most of the time, “mental health clients” receive neither the help nor the respect they deserve.

Report comment

Thank you Steve for your answer.

If there was the possibility the cause was from a brain tumor, would you want an MRI?

Below are two cases

The first is that of a 15-year-old girl who went 2 years of her life labeled and treated for a “mental illness” before it was discovered she had lupus. Once the underlying cause was discovered and treated, she no longer needed psychiatric drugs.

The second is a 45-year-old woman who was dx with bipolar disorder but actually had Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

Unlike other conditions, most individuals who enter into an extreme state, or a psychotic state, loose touch with reality and don’t have the ability to practice mindful introspection.

They end up depending on others, who become the “enablers” and in turn depend on psychiatry. And psychiatry has created a medication management monopoly.

What I advocate for, and I would think others who have integrity would do, is to ensure best practice assessment standards are used to determine underlying medical conditions, or exposure to substances.

While there are no tests to determine a person has a “mental disorder”, there are many tests that prove a person does not have a “mental disorder” but are experiencing psychosis/mania due to an underlying medical condition.

If an advocate does not support best practices, then they are not working in the best interest of the individuals they claim to represent.

1. OBJECTIVE:

The authors describe a 15-year-old African American young woman with a family history positive for bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia, who presented with symptoms consistent with an affective disorder.

METHOD:

The patient was diagnosed with Bipolar I disorder with catatonic features and required multiple hospitalizations for mood disturbance. Two years after her initial presentation, the patient was noted to have a malar rash and subsequently underwent a full rheumatologic work-up, which revealed cerebral vasculitis.

RESULTS:

NPSLE was diagnosed and, after treatment with steroids, the patient improved substantially and no longer required further psychiatric medication or therapy.

CONCLUSION:

Given the especially high prevalence of NPSLE in pediatric patients with lupus, it is important for clinicians to recognize that neuropsychiatric symptoms in an adolescent patient may indeed be the initial manifestations of SLE, as opposed to a primary affective disorder.

2 Case Report

The patient, a 45-year-old, married mother of two, was in her usual state of health, working as a secretary until about 8 weeks before admission to a short-term psychiatric inpatient facility. At that time, the patient began to have pressured, incoherent speech, with thoughtracing, and abrupt shifts of thoughts. She went on spending sprees and built up considerable credit card debt, buying unnecessary things. She had severe insomnia, sleeping only a few hours each night. She also complained of blurred vision and gait difficulty, the latter also noted by her family.

After evaluation of these complaints and a normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, she was given a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder, manic type.

Report comment

Of course, medical problems should always be the first place to look, particularly when there are other drugs (legal or illegal) involved. I think each person deserves a full workup, including checking any possible medical causes. The problem is, this almost never happens. So my answer reflects that I’d want to know what I was looking at BEFORE I saw the medical professionals, because I don’t trust them at all. Given that receiving medical care is the third leading cause of death annually in the USA, I don’t think my concern is unwarranted!

Report comment

I have experienced severe psychosis twice, RR. Not sure my episodes would count since they were induced by a “medicine” to cure my sadness and nerves. They felt pretty real though!

Report comment

Here, it can often seem like psychosis is only something which happens in fluffyland. But I support the thrust of your intention which is to have a thorough physical assessment for people experiencing severe psychosis as it can indicate a known and testable physical cause. Rather than, in the case of a functional psychosis, something as yet unknown and physically untestable.

But yes I do agree that severe psychosis should be taken seriously. I know from personal experience what it is like and there are definitely dangers which are best socially managed, rather than individualistically.

And it is sensible and humane to discount all known physical causes of psychosis before psychiatric diagnosing.

So, in an ideal world, I’d choose (c)

(just to add, in the talk linked to in Steve Morgan’s article, he explains that violence is prohibited by the Soteria model, so the most difficult and challenging individuals would be turned away and/or rejected)

Report comment

The framing of your post is a specific take that you accept and identify in.

The nature of trying to define or render Reality in fixed definitions is a judgement that both gives light specially to its focus but leaves dark or rejects all that does not fit or conform to its set of rules.

So there is a baby in the bathwater, but there is also the reaction that hides the problem in the new answer, because the ‘problem’ is an unfolding of relational being through filters and distortions of denial that manifest as conflicting realities.

Dislocation, dissociation and displacement of self/reality are also the nature of society. The underbelly of society runs a masked psychosis. The recognition of NEED for healing is a key without which some form of sacrifice is enacted or demanded. The set mind in its ‘problem’ sees in terms of the framing of the problem and so yes open the relational awareness to be open to a,b,c,d,e. Relational awareness is both the recognition of the need for healing and the channel or nature of its embodiment.

Dissociated relationships are fixed in terms of a past that is not here and are a normalisation of lack of love.

The nature of split mind as assertion OF a masking reality is to frame it as an expression of prediction and control within a perception of order and chaos, as struggle of powers or survival of the personal sense (as framed) and thus of the thought system that is operating beneath the personal sense.

The complexity of defences in play against exposure to fear cannot be understated. Defences DO the thing they are designed to defend against.

“The whole danger of defenses lies in their propensity to hold misperceptions rigidly in place. This is why rigidity is regarded AS stability by those who are off the mark”. ~(ACIM)

Life does not arise as a multi choice format, nor fit the framework of your ‘what if?’.

Your view may help break a rigidity for some and reinforce it in others.

Discernment, rather than rulebound thinking is what is needed in whatever course of action proceeds from whatever framing of definition gives rise to.

A set identification for or against a,b,c,d,e is likely to operate blindly – that is – without a true relational awareness of the need for healing of the situation for everyone involved.

One can only work with the willingness present – and yet our own can draw forth willingness in others and alignments or synchronicities to the situation that simply cannot fit in the consensus reality.

Negative synchronicities – such as you describe and associate with ‘psychosis’ are not recognized as such when ’cause’ is dissociated from and assigned to symptoms and denied or attacked there.

Where there is harming of self and other, there is also a call for restraint as an extension of love. Not as an act of self-righteous moral or ‘scientific’ superiority.

Our fears are not isolated personal problems in self or others – so much as an interlocking entanglement in conflict-thinking over millennia that has and does ‘physicalize’ or dump or displace unresolved conflict to the body (and world). This is of course a subjection to our own (personal and collective) denied or hidden conflict – but in forms we not only do not recognize – but which our minds are predicated NOT to see.

No one can force another to see truly – nor does that make sense if seeing is the result of an undistorted and therefore un-coerced apprehension. But we can become aware or serve the awareness of choices we are making as conditioned or triggered habit – and so awaken to choices we did not know we had as a result of the framing of a past made in error – and perhaps in terror.

The breakdown of the masking structures is the resurfacing of denied experience that re-enacts a past that is not here upon a living that is thus unseen and mis-identified. This is as much in our ‘body’ as in our ‘mind’ and if Mind is to fearful to open, then working through the physical symbol opens life at a level it can be accepted and shared and grown as the courage to move through fear rather than embody its dictate.

I chose d, but e found me. If I had not had an inner quality of support for being – fear would have made the ‘choice’. Open dialogue is one of the most inspiring approaches I have come across. Retreat is no shame as a temporary move in a larger movement. My sense is that there are better ways to effect restoring boundary for retreat than neurotoxins.

We cannot ‘afford’ any true solution to the reality of our needs under a negative economy of feeding upon and pharming them for profit that piles up debt in more ways than fiscal.

The precondition to the ‘Fall’ or Separation to split mindedness is self-inflation of self-image.

But the recognition of an unconflicted being is ruled out by “All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

trying to put Humpty together again”.

If something matters to you, it shows that you mind or operate upon decisions of focus in value. If what is found to be running is out of true with who you now know and feel yourself to be – then release what does not work/serve or belong to you now. Of course one can make conflict and drama out of this and sometimes that has such tragic or shocking consequence as to call forth a deeper humility/honesty of being or indeed ‘regress’ in attempt to resist feared change or loss of self as currently clung to.

Report comment

And to clarify, I’d choose (c), and if no known physical cause could be found, I’d choose (a), and if they were unable to help, or I found their approach unhelpful, I’d choose (b) but only if it opened the doors to (d) other, which would be ongoing psychosocial support in the community.

Report comment

Great answer, and mine would be the same 🙂

Extreme states of mind, or psychotic states are very unpredictable.

Thank you for recognizing that it is sensible and humane to discount all physical causes of psychosis before labeling an individual with a mental disorder.

It is also important to recognize individuals in our mental health care system, on average, have a life expectancy 25 years less than others. In combination with the over use of harmful psych drugs, we must consider underlying medical conditions that are overlooked as a contributing factor to premature death.

The same underlying conditions that manifest as what is considered a psychiatric disorder in one person, can manifest as a physical/neurological condition in another.

Following best practice standards will create an overall healthier population.

Unfortunately, when it comes to advancing best practice standards, we are on the slow boat to China because one man’s prolonged suffering, is another man’s gain.

Report comment

And to clarify the clarification, I’m imagining myself into a first onset of psychosis scenario.

Report comment

Got me thinking. I did push to have a brain scan. Got all the way to sitting in a room with a neurologist and a nurse and gently they took turns pricking my conscience: “We have long waiting lists”; “There are very sick children.”; “Even if you are brain damaged there isn’t anything we can do about it.”

So I gave in.

I mentioned it again to a new psychiatric nurse I got allocated. He was a top bloke, was open to progressive ideas. But I kept missing appointments, unintentionally. And so a lost opportunity as he said he would back me up for a brain scan.

But now I see the everyone was half-right. It’s not a brain scan looking for brain damage I need; it’s a thorough neurological examination. But like you say, even a neurologist can miss things. It takes a lot of work. I just can’t see the NHS Trust approving such an investigation. Especially as it could conclude with no known condition found.

But that list you make of the many factors that can cause psychosis and mania. There must be many more unknowns.

Thanks again for boosting my thinking around all this. I suppose your perspective is Is Psychosis a Natural Neurological Disorder?

It would be quite devastating to discover I had a treatable neurological disorder this late in my life. But I wouldn’t be complaining if it was treatable!

Report comment

interesting word psych-osis as psychiatrists dont believe in the soul anyway.

But what the hell, he who controls speech controls thought right?

CJ

Report comment

Psychspeak is the language of today. Denying “mental illness” as a brain disease caused by chemical imbalances is double-plus-ungood.

Anosognosia is the ultimate thought crime.

Remember:

SICKNESS IS HEALTH

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS SANITY

“But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.”

Thank goodness Winston Smith developed insight into his condition. Who says 1984 does not have a happy ending? 😀

Report comment