Imagine telling a story, mostly fictional but with a sprinkling of facts, so plausible and compelling as to be taken as true and internalised by whole societies — societies proud of their preeminent science and enlightenment. Imagine telling a mostly fictional story that is adopted and championed even by professionals, academics and major societal institutions, including governments; a story in which millions of citizens are deemed to suffer from psychological conditions termed in the story as ‘mental illnesses’, which must, at the cost of billions of dollars, be medically diagnosed and remediated by doctors, ‘mental illness’ professionals, and drugs of questionable safety and even more questionable efficacy.

Well, as it turns out, this happens to describe the origin and reality of our present mental health system, beginning with a largely pseudo-scientific narrative followed by and necessitating a chain of responses and expenditures. This narrative and its resultant system have become the predominant and accepted response of Western societies to the distress and difficulties of common human experience; both narrative and system have been owned by medicine and health institutions as the preferred approach to ‘mental health’, and have been afforded the status and legitimacy of evidence-based science, purporting to benefit human psychological health and well-being.

This article explains why we should be deeply disturbed by this largely fictional narrative and its resultant system; why we should be suspicious of who actually benefits from the whole enterprise; why it is a largely unnecessary burdensome cost to our economy, and, most importantly, why we can no longer countenance the unconscionable toll it takes on the psychological health and well-being of ordinary citizens.

The ‘pandemic’ we didn’t need to have

The number of people in our community now being diagnosed with and medicated for a mental illness or disorder poses a major challenge for our already overburdened mental health services and the funding required to sustain them. Depression and anxiety (the predominant and highest prevalence diagnoses) have apparently reached record levels. We are told by the mass media and our major mental health institutions that these are one of the major health challenges of our generation. The question is: what is so badly amiss with Western society that should occasion such an historically unprecedented decline in people’s psychological well-being? One must begin to wonder why humanity has suddenly taken such a turn for the worse. Clearly, the psychiatric/medical remedy applied to this problem is a failed enterprise, with the reported prevalence of ‘mental illness’ being unremitting in its escalation, with Australia, Britain and the US reporting between 18–25% of their populations now afflicted with a mental disorder.12

Are we really succumbing to a pandemic of mental illness, or is there another explanation for what is happening? Well, what so many ordinary citizens (non-mental health professionals) have suspected for some time actually goes right to the heart of the matter: that perhaps there is a problem with the way we have come to define and respond to personal distress — including psychological and emotional difficulties which previously would not have been the domain of medical intervention and diagnosis, and would have been largely resolved with various forms of non-medical human support.

Augmenting this idea with some closer analysis of the mental health ‘industry’, what we discover, contrary to what we have been told so often, is not a crisis of mental ill-health at all, but the effects of a deeply flawed narrative of ‘mental illness’, directly related to the systematic medicalisation of common human experience. Put simply, a whole gamut of common, albeit sometimes very challenging and disconcerting human experience has been corralled by medicine (and in particular its specialty of psychiatry) and referred to as illness; and where there is illness, treatments and especially drugs are utilised to attempt to cure it. Had this been a sudden event or decision of governments it might have been seriously questioned, but unfortunately, it is a phenomenon which has crept up on Western societies over recent decades. To use the words of poet Francis de Quevedo, it is one where not only are things not what they seem, they are not even what they are called.

How medicine loses its way when it comes to mental health difficulties

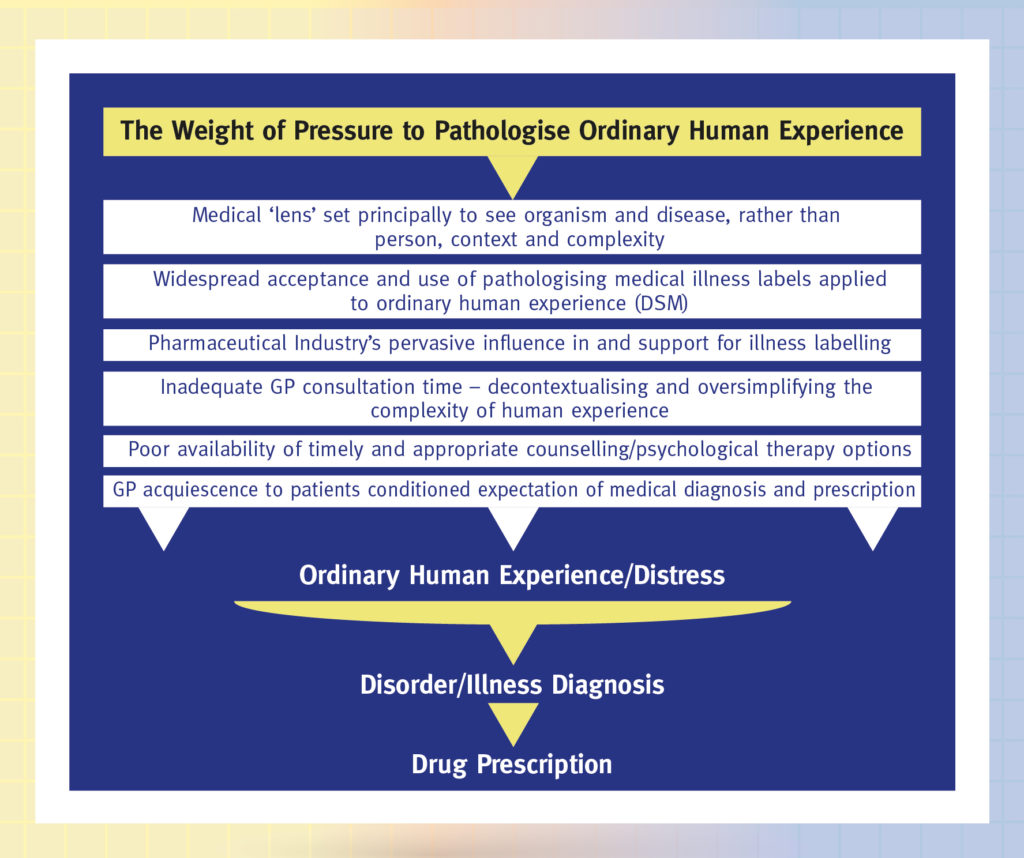

The endeavour of detecting, understanding, diagnosing and treating physical illness is the hallmark paradigm of modern medicine, and one that has shown itself in many ways to be of remarkable merit. However, this approach, though persistently applied to psychological difficulties (or ‘mental illnesses’ and ‘disorders’, as they have been termed), has shown itself at best to have quite limited benefits. When applied to the highly complex individuality of psychological experience, which reflects a changeable interplay of mind, emotions, behaviour, physical sensations, and factors of social and physical environments, it quickly finds itself out of its depth. Attempting to shoehorn this dynamic complexity into static psychopathological illness categories, it is forced to depart from science into untenable reductionism; some would go as far as to say, pseudoscience. This tendency of reductionism expresses itself in another disturbing way: medicine views an individual mostly as an organism to which a diagnosis and treatment is applied, rather than a person of unique complexity who is also a self-acting agent, living in a demanding world and environment which impact on and are integral to their daily life.

How doctors and mental health professionals choose to view or ‘frame’ the person in front of them determines what they ask, what they see, and suggests their options for responding. As psychiatrist R. D. Laing (well known for his critical analysis of conventional psychiatry) emphasised, our relationship to an organism is different from our relationship to a person. How we view and respond to an organism compared to a person reveals different aspects of reality and a very different set of information.3

No person exists or experiences apart from his or her world and others with whom they relate. Consequently, we can never dispense with context or wider determining factors as if they are appendices of questionable value or a mere curiosity in the enterprise of responding to mental health difficulty. When a person seeks out a doctor or a therapist because they are in distress or are encountering a mental health difficulty, they do so with a known sense of their personal history, their whole being-in-the-world, and every aspect of this is interrelated in some way.

There is a common illusion that we somehow increase our understanding of a person if we can translate a personal understanding of him or her into the impersonal terms of an organism or system comprising of a sequence of processes. This is an erroneous perspective. The medical approach is inadequate in dealing with the person in this regard and exhibits an inveterate tendency to depersonalise them and render a reductionist account of them: an isolated set of symptoms to be treated, rather than seeing them as a resourceful self-acting agent.

Interestingly, empirical trans-theoretical common factors research, which aimed to identify key contributors to positive and effective outcomes in psychotherapy, discovered that extra-therapeutic variables (a person’s own personal, interpersonal, and environmental capacities) contribute a huge 40% to these outcomes, with therapeutic rapport coming in second at 30%, and therapeutic method and placebo each being last, individually contributing 15%.4 5

This all begs the question: how did we ever arrive at the point at which we now find ourselves, in a mental health enterprise that seeks to remedy the broad complexity of human distress merely with medication and therapy methods, when neither are usually what are most beneficial?

Why mental illness labelling is depressing

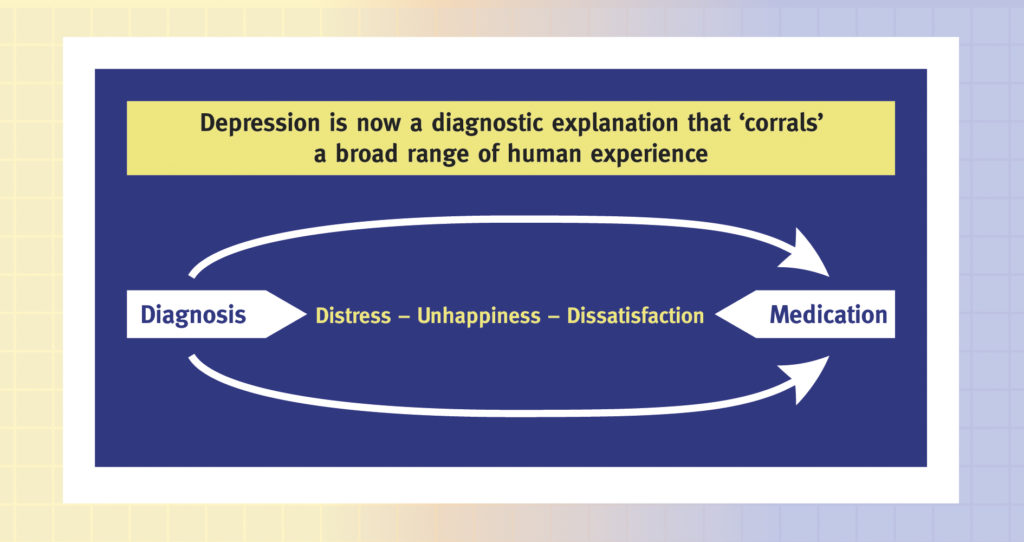

For a prime example to illustrate the problem of turning common human experience into illness, one need look no further than that of depression, which has been deemed by the ‘mental health’ commentariat to be an ‘epidemic’ and a ‘serious social issue’. Major or intense depression can certainly be profoundly challenging and debilitating. The problem is, depression is now a diagnostic explanation applied to a broad range of human distress that does not warrant an illness diagnosis or medication in most cases, even though it might be sufficiently intense to warrant referral for counselling or psychological support. Nevertheless, depression has been popularised in such a way as to dominate contemporary thinking about the experience of distress, unhappiness, and dissatisfaction.6

Depression is now diagnosed with greater frequency than throughout most of the twentieth century: its ‘prevalence’ has attracted an enormous cost associated with its ‘cure’, being the main condition for which antidepressant medication is prescribed.7 8 In Australia, where I live, antidepressant utilisation nearly trebled between 1990 and 1998, and has continued to increase.9 10 11 It is interesting to note that, of OECD nations, Australia is currently the second-highest prescriber of antidepressant drugs.12 Vastly more people are now being diagnosed with depression, and prescribed antidepressants, than several decades ago. Again, these developments have profound social, economic, and public health implications.

Does depression have an adaptive purpose?

If the answer to this question happens to be yes, what do we gain for a person by merely medicating them? Some emotions can create an intense state of self-absorption; we can become fused to our experience, so that all we can think to do is escape it or sublimate it somehow. Unfortunately, avoidance may only perpetuate the experience and will likely intensify it.

According to psychiatrist Carl Jung (a contemporary of Sigmund Freud), depression is a compelling voice urging us not to run away, or to cover over, but to bring content of our unconscious into consciousness; that is, bringing what is sitting at the back of our minds muddying our emotions and diminishing our outward-bound energy into conscious awareness. Depression intentionally narrows our attention, and curbs our ability to engage in pleasure sublimation, in order to get our attention. We are being summoned to engage with and integrate more effectively, past memories and experience, and to bring into perspective ideas and beliefs that may be self-limiting.13

Jung believed that depression foreshadows a potential renewal of personality or the readiness of a new page to be turned. How does it help to medicate a person in a way that merely dulls their senses and little else? To do so can be a form of collusion with avoidance, ensuring a worsening condition rather than remediation of one.

Depression means literally ‘being forced downwards’, Jung would say, because we have become cut off from some things of importance within ourselves; and of course, what people often need to confront are their own corrosive, emotionally and physiologically debilitating fears. It has been said that if we do not exercise the power we have, it will slip imperceptibly into the hands of others; in can also fall into the ‘hands’ of our worst fears, which are then empowered to tyrannise us.

Jung suggested engaging with our experience of depression: learning from it not getting rid of it; thus freeing us from the impossible expectation that things should be easy, that life should be always happy, and that we can just run away from things rather having to listen, learn, and work them through.

The psychiatric catalogue that has a disorder to suit almost everyone

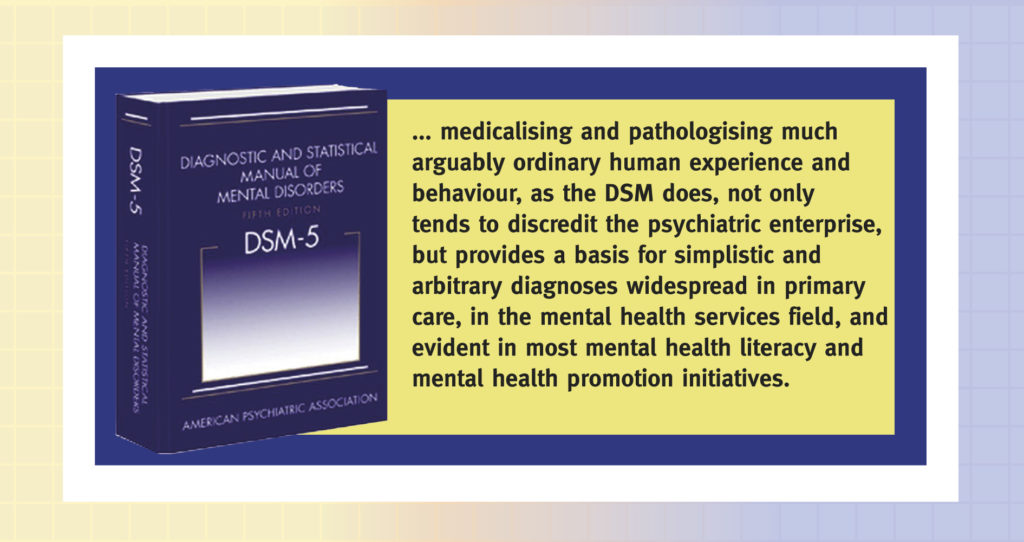

The transformation in the way we have come to understand human experience as ‘illness’ perhaps gained its greatest momentum with the introduction of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Statistical Manual (which is now in its 5th edition: the DSM V), an attempt to provide psychiatrists and other mental health professionals with a comprehensive catalogue of all ‘recognised’ mental illnesses and disorders, including their symptoms. Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals dealing with people’s mental health difficulties do need some common language and conceptual basis for collaboration and advancing research. However, medicalising and pathologising much arguably common human experience and behaviour, as the DSM does, not only tends to discredit the psychiatric enterprise, but provides a basis for the simplistic and arbitrary diagnoses widespread in primary care, in the mental health services field, and evident in most mental health literacy and mental health promotion initiatives.14

Editions of the DSM have always attracted controversy and criticism, including from many psychiatrists and doctors themselves; the most recent version (DSM V) is no exception. Criticisms include: lack of empirical support, a revision process and content influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, and an irrepressible tendency to medicalise and pathologise human distress — patterns of behaviour, mood, and experience for which a person may well need professional support, yet which do not constitute illness or disorder.

Labelling human distress as ‘illness’ or ‘disorder’ is not a mere linguistic trifle, it can have quite negative consequences for patients. As someone once quipped: labels should be applied to jars not to people. There is also the ethical issue of science and medicine betraying the trust of consumers (whose trust they cultivate) by allowing it to be thought that the mental illness narrative (informed by the DSM) is actually evidence-based science, when so little of it actually is.15 16

If we took a snapshot of a significantly difficult time in almost any individual’s life, one affecting their emotions, mood, physiology, and behaviour, we would very likely discover that what characterised their experience corresponded with a disorder profile listed in the DSM.17

If we took this same snapshot and presented it in a busy General Medical Practice appointment, it would be even more likely to be identified as representing a DSM illness or disorder because of the lowering of diagnostic thresholds often characteristic of these contexts of consultation, due to so-called “10-minute medicine.” There simply isn’t time even within a 20-minute session to adequately listen to, contextualise, or appreciate the complexity of patients’ psychological distress or difficulties, let alone offer a useful diagnosis or treatment suggestions.18

In the United States, a 1993 study by the Rand Corporation showed that over half the physicians wrote prescriptions after discussing depression with patients for three minutes or less.19

Whilst many GP’s do try and refer patients to psychological services (rather than just prescribing drugs), to be eligible for subsidised services, patients require a diagnosis that fits with the criteria of a recognised disorder or illness. The demand for such services is already overwhelming in many parts of Australia (which means some consumers must wait months for appointments); a dilemma now being targeted by short-term stopgap measures such as online resources and IAPT programs (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies), which are themselves problematic, and simply perpetuate an ailing model of mental health care.

Not medicalising common human experience actually encourages taking it more seriously

It is important not to be seen as trivialising in any way the human suffering caused by psychological distress or mental health difficulties; in fact, though it may seem somewhat counterintuitive, my purpose (consonant with what I call The Situational Approach, which I will explore in future blogs) is to reconceptualise human experience in a way that demands a greater regard for it and more appropriate and helpful supportive responses. And it needs to be said, there are cases of mental health difficulty that do warrant some medical intervention and perhaps the limited and evidence-based use of psychotropic medication — such as when people are put at risk or severely depleted in capacity because they have persistent, debilitating, and increasingly isolating mental health difficulties. However, by far the majority of psychological or mental health difficulties presently categorised within psychiatry and medicine as mental illness or disorder do not warrant this kind of pathological insinuation, and exhibit little positive response (if any) to medical or pharmacological interventions, and need to be addressed in quite different ways.

When we approach a person with the purpose of detecting a disorder or illness in need of diagnosis and perhaps treatment, and we use the language which corresponds with this intent (that of disorder and illness), we keep the person at a distance from us: we isolate, simplify and circumscribe the meaning of their life, reducing it to a clinical entity, a psycho-pathological category. Not bothering with their history, the critical factors of their immediate environment, or the complexity of their experience in relation to these, we squeeze them into a depersonalising and reductionistic diagnostic mould that does not serve their best interests but those of presumed economy and convenience.

When we unnecessarily intervene medically or pharmacologically, thinking we are being humane or helpful, we are in fact doing neither, and are more likely to be doing harm.

We need to provide appropriate support to people, not paternalistically rescue them

Individuals have multiple potentialities, are resourceful, and have their own innate capacity for healing and transformation. Accepting a person as a whole means paying attention to their freedom, responsibility, and competence, and not rescuing them from their experience, but finding a way to supportively accompany them through it. This opens up possibilities instead of closing them off, which tends to occur if the person is not encouraged to maintain responsibility for their experience and to respond to their experience, which can reveal meaning and options hitherto unrecognised. This is true even in unalterably difficult circumstances. As holocaust survivor Dr. Viktor Frankl once said: we may have little or no control over some things that happen to us, but one freedom can never be taken away from us is the freedom to choose how we respond.20 Exercising such a choice is an act of power, one that can be a potent antidote to powerlessness which so commonly diminishes people’s mental health. Powerlessness can generate highly corrosive emotions, and is well known for cultivating chronic stress, insomnia, depression, anxiety, and patterns of suicidal thinking.

Professor of psychology Miles Groth makes an important point when he suggests that we need to try and be careful to distinguish between what is developmentally appropriate and inevitable for a person, and what is genuinely threatening them with isolation and compromised function in everyday life.21 This is a vital distinction: in relation to the former we may need to humanely companion them through their experience, riding out their suffering with them, without trying to rescue them from it or helping them avoid it. In the case of the latter, we may have to intervene and offer an alternate route for them to try out.

In discussing the content of this article with a psychiatrist recently, she offered the following rule of thumb for any professional assisting others with mental health difficulties: “Whatever a patient brings to me of their experience, I assume to be normal, and I continue to assume so unless there are compelling reasons to think otherwise.” Intrinsic to this normality is a capacity and expectation of self-responsibility, competence, self-discipline, restraint, and the dignity of causality.

We need to be careful that in our desire to help, we don’t presume to rescue a person from the very experience that might otherwise give rise to an adaptive and helpful shift in their thinking and experience, depriving them of quality of life rather than enhancing it.

Even in severe difficulty, people rarely need to be rescued from their experience, but may need to be supported and companioned through it so that they can be kept safe and respond to it adaptively.

Diagnosing mental illness, in many cases, risks consigning people to psychological sedentariness and dependence on psychotropic medication. Given the near absence of efficacy of such medication (except in some cases of severe mental health difficulty), patients are unwittingly surrendered to the whims of their ‘condition’ and a revised self-narrative and self-identity coupled with a trajectory of undeserved dependence and frailty; they are encouraged to exchange an internal locus of control and autonomy for an external one; and we call this promoting mental health?

The role of complexity in making life difficult and sometimes overwhelming

Another way of conceptualising acutely challenging, difficult, and sometimes debilitating human experience is to recognise the role of complexity. If a person is overwhelmed with stressors (apparent causes of stress) and challenges beyond their adaptive capacity to keep everything under some sort of control and to maintain an internal equilibrium, and if they are severely decompensated by their experience, their weakest point of physical or psychological susceptibility is what will break down under the pressure; they will likely succumb in the direction of their greatest weakness, whether that means an undesirable gene is switched on, mood becomes disturbed, anxiety sets in as an intolerable burden, or a compromised immune response leads to sickness.

This idea of complexity that overwhelms is useful to consider alongside the mental-health-diminishing effects of powerlessness; both cause much suffering. Both likewise respond well to companioned problem solving, purposive acts of power, and being able to achieve order, perspective, and a sense of feeling back in control.

Exposed to yet assisted through such an experience, people may learn new skills and develop a greater capacity of resilience. It takes little imagination to understand why a 10-minute or even a series of 10-minute medical consultations will be an inadequate response to such complexity, or to understand why pharmacologic sublimation of symptoms will achieve little except to prolong a condition that is neither extraordinary, insurmountable, nor necessarily chronic in potential, given time, patience, and appropriate support.

Side-lining crucial lifestyle changes with the offer of medication

In Australia, as with other western societies, an emphasis on illness and drug treatment have eclipsed considerations of lifestyle change, self-help and psychotherapy, despite these being almost always more beneficial. For example, approaches such as light exposure therapy, structured daily physical activity, reduced alcohol consumption, a balanced diet, and measures to improve sleep.22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Too often, even when such measures are recommended to patients they are not a first-line approach but an adjunct to medication and are thus perceived as recommended but non-essential alongside the more medically definitive drug prescription. Since they also require more time and effort, they come a poor second to the presumed (and marketed) efficacy of a purpose-designed antidepressant drug.

Professor Peter Gotzsche argues that the current usage of psychotropic drugs could be reduced by 98% and at the same time improve people’s mental health outcomes and survival. In relation to antidepressants (amongst the most widely and frequently prescribed drugs), he further argues that such medications turn many self-limiting episodes into chronic ones.30 In relation to the most popular antidepressants, the SSRI group of drugs, he forthrightly cites the little known meta-analytical data of six research trials (718 patients) which suggest that:

…selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were ineffective for both mild, moderate and severe depression, and even for patients with very severe depression, the effect corresponded to only 3.5 on the Hamilton scale, which is well below what is a minimal clinically relevant effect.31

The high cost to tax payers and industry of mental illness labelling

The medicalisation of human distress, promoted by high-profile and heavily funded mental health literacy initiatives and mental health services, not only has profoundly negative implications for unwitting consumers caught in its web (and deemed ‘mentally ill’), but as well for the functionality and economy of our mental health system. The estimated cost of mental ill-health to Australia is around four percent of GDP or about $4,000 for every tax payer.32 That this system is overwhelmed by demand and not serving consumers well is a much-discussed issue amongst the general public and in the media. Unsurprisingly, the present mental illness paradigm appears to have led our mental health system into economic and service delivery crisis. Things are little different in the UK which foots the bill for a similarly dysfunctional approach to ‘mental health’ to the tune of between £70 to £100 billion a year.33

The big losers in all of this are of course unwitting consumers, tax-payers, and corporate insurance industry providers who carry a huge financial burden due to the present mental health system. All are bearing the brunt of an indefensible narrative of mental illness and a flawed model of mental health that show little regard for standards of evidence or ethical human service practice.

Suicide prevention efforts bedevilled by the mental illness narrative

A significant consequence of an eagerness to diagnose mental illness in people experiencing psychological distress unfortunately turns up in the field of suicide prevention, and may well be putting people at greater risk of suicide. This is because suicide prevention initiatives, preoccupied with detection of ‘mental illness’ such as depression, often overlook and fail to address forms of distress that don’t constitute any kind of illness or disorder, and yet which can result in suicidal ideation (thoughts preoccupied with suicide) and suicide.

The current mental illness narrative evident in mental health literacy messaging and commentary on suicide prevention has tended to reinforce the idea that suicide should, in most cases, be considered to be the result of mental illness or disorder. However, evidence does not support this claim. Whilst conditions like major depression may sometimes be implicated in cases of suicidal ideation and death by suicide, and are an important consideration in the design of appropriate preventative measures, this should not be considered license to assume an association between the two that is simply unsupported.34 Limiting preventive strategies to those built upon the unfounded presumption of mental illness or disorder will simply not help many, perhaps the majority, of those at risk of suicide.

The experience of being human can sometimes be acutely distressing, even overwhelming and debilitating. Nevertheless, even when such experience tests the limits of endurance and adaptive capacity of the individual, it does not constitute a diagnosable illness but more a condition demanding the individual’s assiduous attention, acknowledgment of the imperatives of change and adaptation, use of self-help strategies, learning new insights and skills, a willingness to procure social support, and, when necessary, utilising the knowledge and skills of a professional counsellor or psychotherapist. By far the majority of mental health difficulties benefit most from these measures, not from medical intervention or psychotropic medication.

It is not at all simplistic to suggest that much of our mental health system apparatus could be dismantled, and prescribing drugs especially for high-prevalence mental health difficulties could almost cease, if instead we opted for an evidence-based approach to dealing with human distress and psychological difficulty; an approach that acknowledges the innate capacity of each individual to recover from their distress and difficulty, if accompanied by timely and appropriate social and, if necessary, professional support. Madness is least of all to be found in individuals, but alas, it does characterise our present cultural and institutional approach to mental health.

Thanks for the great article, John. If I had a suicidal friend or acquaintance I’d be hard put knowing what to do. I’m no fan of the bio model since it almost ruined my life.

I would prefer to set up a “watch” with a couple other people to give comfort and hope to the sufferer. Kind of like they did for President Lincoln when his “blue pills” made of mercury didn’t cure his sadness.

Medicalizing human distress makes people take it less seriously. One of those counter intuitive truths we seldom acknowledge. Instead of saying “Joe is sad because he lost his job,” folks say, “Joe’s depressed because he’s nuts and has a screwed up brain.” Depression and anxiety are real. But by brushing them off as brain diseases we teach Joe he doesn’t need to find a new job. Unemployment isn’t the problem. He is. Then marvel when Joe’s depression worsens.

Be forewarned some here may object to your terminology and lack of quotes bracketing terms like “Mental Illness.”

Report comment

Thank you.

I found this summary really valuable.

You mention the way that the pathologising approach actually prevents severe human distress being treated with the seriousness it deserves. I’d like to add that it also prevents the causes of severe distress from being taken seriously.

This is another feature of psychiatry. If distress proves that the distressed are ‘defective’, it also proves that nothing much is psychologically distressing and damaging. It means that both cause and effect are located within ‘defective’ individuals. It is effectively a not guilty verdict for every form of oppression and abuse and sympathy and solidarity with harm doers, and with the harm itself. It enables the punishing approach to those who are most hurt from onlookers both inside and outside of psychiatry and encourages everyone to harden and turn away from suffering, inside and outside of themselves. No wonder the number of those showing ‘symptoms’ is growing exponentially.

It is a marketers paradise.

Report comment

A psychiatrist is like a man who takes a crowbar to another person’s shins. “If your bones weren’t defective they wouldn’t have splintered.”

The legal system punishes crimes. Psychiatry punishes weakness.

Report comment

A good analogy! “Your bones broke because you have ‘brittle bone syndrome,’ a genetic disorder. Most people are able to take that kind of hit without their bones breaking, so really, it’s your body that is deficient. It has nothing to do with the crowbar.”

Report comment

Assuming the person actually had that syndrome that still wouldn’t justify the “treatment” with a crowbar.

Report comment

Well said, indeed!

Report comment

this deserves repeating:

“This is another feature of psychiatry. If distress proves that the distressed are ‘defective’, it also proves that nothing much is psychologically distressing and damaging. It means that both cause and effect are located within ‘defective’ individuals. It is effectively a not guilty verdict for every form of oppression and abuse and sympathy and solidarity with harm doers, and with the harm itself.”

Report comment

Good point. Wittingly or unwittingly bio-psychiatrists enable abusers.

Report comment

Well said, Out and LavenderSage.

Report comment

I agree wholeheartedly. This is in my view the most serious damage psychiatry has done to our society. It has removed context from our suffering and made it a trivial matter, as well as making it an entirely individual problem, as if any upset or disagreement with our social system is proof of personal malfunction, and the system itself is flawless.

Report comment

When, in reality, if one studies our society’s current systems (be it the medical / pharmaceutical industrial complex, the banking system, the military industrial complex, etc.), one does find that all our society’s current systems are satanic.

Report comment

I am having a problem here…psychiatry is not the only problem..

all of us that are suffering want a quick fix…I want a quick fix…

but I have not found anything to fix me…

Report comment

No, everybody does not want a quick fix. Some of us recognize that there is simply no such thing.

Report comment

I agree, LavenderSage, everybody does not want a quick fix. We want truth instead.

Report comment

I am afraid there are no “quick fixes.” A quote from “The Princess Bride” movie applies here: “Life IS pain, highness. Anyone who tells you otherwise is selling something.” Psychiatry promises a magical no-effort solution to “mental illness” where no one needs to change anything and no one needs to take responsibility for everything and we can continue to pretend that life’s a lark and anyone who doesn’t feel that way needs to be “fixed.” Have you ever read “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley? That’s the direction the psychiatric industry is taking us. “A Gramme is better than a Damn!”

Report comment

Get rid of forced treatment, and you’ve quickly fixed much of what is wrong with the “mental health” system. The question remains, why imprison innocent people in the first place. In the name of health? You’ve got to be kidding. I’m imprisoning you to protect you from yourself and/or other people. Really? Not if I have anything to do with it.

Life is a risk people should be allowed to take.

Report comment

There are no genuine quick fixes. There are stop gap measures–which psychiatry can offer many.

Then there are slow fixes that actually work.

Report comment

Oh, “littleturtle”! I really do think I know what you mean, when you say that you want a quick fix, but that you can’t seem to find that fix.Please let me suggest that you are NOT BROKEN. I’d say that you’re entirely normal, given everything that’s happened to you! What worked for me, was being told that within myself, there is a whole, healthy, and happy person. Then, I had to look long and hard at that, and realize the TRUTH, that I really AM a whole healthy happy person. And hey, maybe I’m wrong about this, but I really do truly believe that YOU TOO, are a whole, healthy, and happy person. And reading some simple books by the Dalai Lama helped me to understand that I could let go of my “conditional happiness”, and have UNCONDITIONAL HAPPINESS. I can decide to be happy just because, for no real reason, other than my own deciding to be happy anyway. Today, I’m a happy man. Even when I’m unhappy for a while. Because I believe in the whole, healthy, happy person inside myself. Does that make sense? I’m always happy to see your short, simple, honest comments here.

Report comment

They can put as much money as they like in but they can only make matters worse (with the bio approach).

If I was in desperate circumstances I might need help – but I’m not. Otherwise I seem to be quite happy!

Report comment

Mental illness is a myth. It always has been. Karl Kraus understood the charlatanry inherent in psychiatry before any of us were born. But no one reads Kraus, or Szasz. Hence, pervasive ignorance reigns, and the myth of mental illness dominates the collective consciousness. These aren’t new insights. It’s just that, like most truth, the insights are perpetually ignored, rejected, or ridiculed. Psychiatry is a pseudo-scientific system of slavery. The sooner it is abolished, the better.

Report comment

Hello again Dragon, Its a dead end!

Report comment

thanks, slaying the dragon. I mean that.

Now…

as much as I could easily do without Szasz’s elitist, conervative outlook, I -do- acknowledge his absolute brilliance in debunking psychiatry and the rest of the “helping professions.” and so..

As a Christian, I find the latest Epidemic of Psychiatry aboslutely horrifying. The Huge Lies that Mental Health, Inc. tells us…from the LPC counselors on up to the MD psychiatrists…are, from my Christian perspective, lies straight from the pits of Hell. When tragedy strikes, counselors are mobilized to help people “process their trauma” or whatever. Not only do they seem to make things worse for the individuals affected, but..

they–the enforcers of Mental Health, Inc.–are spewing useless, often (usually?) damaging lies that are confusing everyone. They’ve colonized the (post)modern mind. I seem to recall Szasz writing that one very good reason to abolish psychiatry is to improve “clarity of thought” or something to that effect. I must say…I agree, wholeheartedly.

Its slavery for most “mental patients,” an overpriced waste of time for the more privileged people/”patients.” And Mental Health, Inc. has grown ever more powerful, ever more devious, since the days of Szasz, Laing, etc. My -personal solution- has been to pray for restoration (its been granted, Praise God) and now for a graceful, easy, quiet exit (still working on that…). It isn’t enough to taper off the psych drugs; one must be set free from the lies and bondage that are the core and foundation of

Mental Health, Inc.

Report comment

Good luck in your “quiet exit,” yeah_i_survived. Personally, when I left, I called it “The Great Escape.” Although, I had to escape both the church, as well as their “mental health” minion at the same time, since those industries are in bed with one another (the atheistic DSM is currently being taught in the seminary schools). Some lyrics that describe my “great escape.” But I, too, escaped with God’s assistance.

“We can make it right, Throw it away. Forget yesterday, We’ll make the great escape. We won’t hear a word they say, They don’t know us anyway. Watch it burn (a local church roof did burn during my ‘great escape’), Let it die” (my childhood religion is committing “suicide,” according to others).

“‘Cause we are finally free tonight, Tonight will change our lives. It’s so good to be by your side, But we’ll cry. We won’t give up the fight! We’ll scream loud at the top of our lungs, And they’ll think it’s just ’cause we’re young. And we’ll feel so alive. Throw it away, Forget yesterday. We’ll make the great escape….”

I share your belief that God is the answer, but do be forewarned that the paternalistic religions and their atheistic “mental health” partners in crime are not. It is a shame the mainstream religions bought into the psychiatrists’ material world believing only, Holy Spirit blaspheming, multibillion dollar, iatrogenic illness creating, primarily child abuse covering up, “dirty little secret of the two original educated professions,” faustian deal.

Report comment

Hello. I’ll be praying for you.

Off the drugs for well over a year, but struggling with weird physical problems. Occasionally I break down and see a doctor but they’re baffled. Plus my records read my “mental” history so I’m scared they’ll discover I’m a naughty runaway.

Can’t absorb micro nutrients very well. Now I have spells of horrible itching and break out in welts.

Hoping an alkalized diet will offer relief. My system is undoubtedly inflamed and out of balance.

Report comment

Weirdly enough this modern fake bio-model leaves out some other possible bio models as well. It’s like treating pain by sewing someone’s mouth shut so they don’t scream. At least the doctors don’t hear any crazy talk. People can become very miserable from physical illnesses and things like poor sleep. I saw one story about a woman who cured her son’s ADD by fixing his sinuses so he could sleep. It took a lot of detective work to find an underlying cause for his angst. But there was one. He was in constant pain and thought it was normal. This model is super lazy. It’s 14 years of med school for matching symptom A with drug B. I saw an article about a possible relationship between the immume system and shizophrenia symptoms. Someone got a bone-marrow transplant and it cured his hallucinations. The opposite happened as well. There is totally human distress from abuse and interesting ways people develop to cope with it which may not work forever. We don’t give people enough credit for interesting ways to heal or be.

I enjoyed hearing about Carl Jung’s depression theory. It would make sense that some who experienced a psychotic episode would understand how to come out of darkness.

I like complex chemistry and biology. I came to the conclusion tonight that anyone who even understands pharmacology on a hobbyist level would think many psych drugs are immoral and not even appropriate treatments in many cases. ( Why give someone with complex issues something that shrinks the organ which is capable of fixing it? Why does someone with emotional problems need all of their nervous system slowed down?)

I don’t understand how we got here but I hope we can leave someday and move on to Western medicine as a whole. The symptom A drug/surgery B model is many places.

Report comment

“MPs to investigate the scandal of youngsters with autism and learning disabilities being locked up like criminals in psychiatric units”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6475141/MPs-probe-NHS-prisons-scandal.html

Can someone (BBC researcher maybe) give this to Harriet Harmon please. It is one of the ways people in these situations and circumstance need to be engaged and the appauling drug ‘treatments’ stopped:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1844561

Pyridoxine (B6) probably works because the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase requires B6 to function. Glutamate decarboxylase is what converts glutamate to GABA and calms people down.

Reference:

http://www.worthington-biochem.com:8080/enzyme-manual/GLDP/

The importance of Magnesium is that it regulates the transmission of the glutamate neurotransmitter (major excitatory neurotransmitter) by blocking the NMDA receptor.

Reference:

https://youtu.be/-mHgPfXHzJE?t=46

It will take a long time – many months into years – to get these victims of psychiatry okish due to the drugs, they should be very very slowly brought off them and all of them… I do not know ANY psychiatrist who really knows how to do this. It is only psych survivors who have been throught it who really know how to do it.

Report comment

The psychiatrically drugged “should be very very slowly brought off [the psychiatric drugs] and all of them… I do not know ANY psychiatrist who really knows how to do this. It is only psych survivors who have been through it who really know how to do it.”

Words of wisdom, streetphotobeing. And this is particularly true, since most of the psychiatrically drugged today are misdiagnosed/ stigmatized/ defamed/ discredited child abuse survivors, according to the medical literature.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

Why all this misdiagnosis of child abuse survivors by our “mental health professionals” today? Because no “mental health professional” may ever bill any insurance company for ever helping any child abuse survivor, unless they first misdiagnose them.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

It’s a shame our “mental health professionals” are not intelligent enough to understand that aiding, abetting, and empowering the child abusers/traffickers/rapists is not just illegal, but unwise. Since profiteering off of covering up child abuse crimes, on the massive scale at which today’s “mental health professionals” are doing this, will eventually destroy humanity.

Report comment

Thanks for those links. Yes, sure confirms the view that MH life long labeling/drug destruction is now financially incentivised. In the UK we have the facade of a National Health Service in that you do not pay at the point of ‘care’ In reality GP’s are pretty much all in business. And the so called regulation… GMC, PHSO, CQC is there to protect the doctors, unless they are drunk and sexually assult someone they can drug the hell out of people, lie about the drugs enforced and nothing happens. Then if the abuse is so outrageous, it is covered up for decades and comes out in the news for a day or so:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5992719/Doctor-used-paralysing-truth-drug-rape-abuse-children.html

It seems even after death they are still screwing us over:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6098431/Scandal-3-6million-NHS-ghost-patients.html

Report comment

Turning lots of kids into brain damaged drug addicts is also unwise. But evil tends to be short sighted.

Report comment

i have a problem with this anti-psychiatry talk…

I like critical psychiatry…and critical psychology…

I have a very good psychiatrist….he has helped me..

why trash everything about psychiatry….

how about bio/psy/soc/econ/pol…..model of cause..

Report comment

I had a better psychiatrist recently but I’ve had many bad ones. My fiance sat in on one where I told the doctor I was feeling well and he suggested I take more drugs. Specifically one that’s on my chart that I’m allergic to. When I pointed it out he still tried to convince me it was the right idea. This psychiatrist is recognized as the best in the area. I think if there were more Kelly Brognans out there who were willing to put in a lot of effort into actually helping people things might be better. That hasn’t been my experience though. Perhaps if there was an easy guide like the DSM that was actually informative towards recovery and not “treatment” we might get somewhere. A lot of us have given up on subtlety though because people are dying and suffering. There’s a sense of urgency. I once wanted to be a psychiatrist to help unhappy kids like me…but I’ve never met a professional who would know a gentle enough intervention. I really…really just needed a friend, maybe more freedom. Somewhere to belong. But what I didn’t need was someone to tell me something was deeply irreversibly wrong with me. This was all I heard from both psychiatry and psychology. I was malnourished of love and pressured to succeed, but there must be something wrong with my DNA? Why do this to a person?

Report comment

TO “littleturtle”: I think your experience is valid. But I also think your experience is the exception, not the rule.

Of course I don’t REALLY know you or your situation, but I take you at your word. Your psychiatrist may be one of the exceptions to psychiatrists in general. And, maybe you have a good relationship with your psychiatrist IN SPITE OF the fact they’re a psychiatrist, and NOT BECAUSE they’re a psychiatrist. See what I mean? Just because you have a good experience with your psychiatrist, DOES NOT mean psychiatry as a whole is any good. I’m glad you’re here, and I hope you keep coming back and commenting here. You always get right to the point, and say what you want to say in simple short words. With lots of us here, when WE comment, it’s like we’re writing a chapter for a book! Personally, I think so-called “mental illness” is something that we ALL have, just that *some* of us end up taking drugs from psychiatrists! We’re the UNLUCKY ones! 😉

Report comment

“Madness is least of all to be found in individuals, but alas, it does characterise our present cultural and institutional approach to mental health.” Thank you, John, for pointing out the insanity of today’s psychiatric system.

Report comment

“If a person is overwhelmed with stressors (apparent causes of stress) and challenges beyond their adaptive capacity to keep everything under some sort of control and to maintain an internal equilibrium, and if they are severely decompensated by their experience, their weakest point of physical or psychological susceptibility is what will break down under the pressure; they will likely succumb in the direction of their greatest weakness, whether that means an undesirable gene is switched on, mood becomes disturbed, anxiety sets in as an intolerable burden, or a compromised immune response leads to sickness.”

John, I liked your article and look forward to future contributions, but I wondered how the above, if I understood it correctly, can be applied to children who are subjected to abuse and trauma. Surely we don’t think of children under these circumstances as having experiences beyond their adaptive capacities, weak points, succumbing, susceptible or decompensating, but merely as children who are abused or traumatised. Furthermore, are we blaming these kids for not being resilient enough to deal with these experiences and that they should develop a greater capacity for it?

Report comment

A valuable article. Not much to add, though maybe a re-read will spark some sort of minor disagreement.

All I would add is that the obvious reason for defining people as “ill” rather than suffering from the concrete realities of society is that (capitalist) “society” gets a pass, while the individual reacting to it is deemed the problem. Any question as to who benefits from that?

Report comment

Don’t forget those abused by partners or guardians. If a wife or teen looks stressed and out of it while the abuser is well dressed and knows what to say the shrink will blame everything on the abuse victim.

“Nobody’s fault. Just the crazy with the messed up brain. Their fault always. But we’re not ‘blaming’ cause we write them off as hopeless so they can let us take care of them like five year olds till they die. See how nice we are!” 😛

Report comment

True; don’t know if you’re distinguishing that from “society” (I don’t) or just making the point for good measure.

Report comment

Both. Your view of society was much broader. Social models differ according to size much like physical designs which cannot always be directly scaled.

Report comment

Thank you for this excellent article. It’s exactly what I experienced when steroids (taken with chemo) caused me to have insomnia. My only “symptoms” were insomnia and some anxiety (due to the horrible side effects of chemo) that nearly every person in cancer treatment experiences. Yet a psychiatrist ruled that being a cancer patient in the midst of grueling treatments was irrelevant and not a ‘situation’ or reason for insomnia or anxiety. Instead the insomnia was ruled a brain disorder and flawed character. It was stunning to realize psychiatry is exactly as you say, history, context and complexity of a person’s situation or environment are completely ignored.

From what I read/ learned the last few months it is appalling that psychiatric patients are treated far worse than hardened criminals. As more professionals speak out, and psychiatric survivors report the harm they suffered and word keeps spreading to more people who were previously unaware of what goes on, hopefully governments and others in power will no longer ignore the injustices of the authoritarian regime psychiatry has become.

I look forward to your future blogs in which you explore what you have termed “The Situational Approach”.

Report comment

I’m surprised that Dr. Ashfield made the tiny, but significant error, and NOBODY else noticed it! There’s no such thing as a “DSM-V”. It’s “DSM-5”. The APA dropped Roman numerals in favor of Arabic. Look at the picture above, DSM-5! And, the DSM is really a catalog of billing codes. ALL of the so-called “diagnoses” in it were INVENTED, and NONE of them were discovered. If so-called “mental illnesses” really were as “real” as the psychs want us to believe, than they would have been discovered, not invented. So-called “mental illnesses” are exactly as real as presents from Santa Claus, but not more real. They are “STD’s”, – socially transmitted disorders. The DSM is just an excuse to $ELL DRUG$. More different diagnoses, more drugs to sell. A diagnosis and a drug for everybody! And PhRMA is laughing all the way to the bank!

There’s another glaring perceptual and cognitive error on Dr. Ashfield’s part. Despite the plaintive cry of the politicians and the media, there is in fact NO concern on the part of “BigGOV” and industry to “cut costs”, or “save money”. Given the Central Banks that all countries have, it’s FUNNY MONEY, or fiat currency. No, they really do NOT care how much money it costs. Dr. Ashfield ignores (due to economic anosognosia, no doubt!), asking the question of WHO GETS all that tax money? Almost NONE of that money is going to the poor “mental patient” on government “benefits”, but the salaries of those employed in the system only rise, and PhRMA’s profits only ever grow. If the motive was truly to help people, wouldn’t pharmaceuticals be required to be only on a “non-profit” basis? Like ANY business in our current late-stage capitalism, it is designed to ONLY GROW. More mental patients, more drugs, more drugs, more mental patients….

With all due respect, what I’m saying here makes Dr. Ashfield’s words here sound kinda like psychobabble and gobbledygook to me. Nothing personal intended, Dr. Ashfield, I really do think you’re at least facing in the correct direction! 😉

Report comment

“If the motive was truly to help people, wouldn’t pharmaceuticals be required to be only on a ‘non-profit’ basis?” Interesting theory, Bradford. However, it likely wouldn’t work, since many of the religious owned hospitals, profiteering off of the doctors handing out these neurotoxins, are “non-profit.”

And I know, from contacting the head of my former religion, and from checking out a seminary where they are teaching the atheistic material world believing only DSM, that the religions are in bed with the “mental health professionals.” And neither the religious organizations nor the “mental health professionals” want to get out of the business of creating “mental illnesses” in people with the psychiatric drugs. Because “it’s just too profitable,” according to one pediatrician I asked to stop psychiatrically drugging our children.

But you’re right, what the doctors and religious leaders don’t seem to understand is that the war mongering and profiteering, bailout needing, fiscally irresponsible, “too big to fail” globalist bankers’ have destroyed the value of our currency. Or, as I mentally ‘screamed’ at the Chicago Federal Reserve, during a drug withdrawal induced “manic” walk down Chicago’s Mag Mile. “Greenspan spanned the green to the point it’s ‘irrelevant to reality.'” Everyone’s name has meaning, as the God fearing Jewish people know. You can take the ethical banking families out of the banking business, but you can’t take the knowledge of the banking industry out of the ethical banking families.

Report comment

This is a valuable and comprehensive article, but lacking in important ways.

I am glad to hear that a series is forthcoming, and look forward to hearing more about political aspects like intersectionality, and action steps to take to remedy the system, both by professionals and those with lived experience.

The intersectionality is crucial to a basic understanding of emotional distress and was considered very little here. For me, one of the biggest problems with modern mainstream psychiatry is that it is a distraction from real societal causes of distress and trauma, on both individual and systemic levels. Failure to address this in the article is a major omission, in my opinion.

If one outlines a system to raise consciousness of the issues without providing valid alternatives in detail, what’s the point?

Report comment

“Intersectionality” is a term that primarily is used by liberals/neoliberals and does not truly address capitalism. Various forms of oppression do not just happen to “intersect,” in this day and age they all serve the same interests, i.e. the accumulation of obscene wealth by a tiny few.

I do agree with you in general of course, the source of people’s misery is to be found in the political/social structure and that is what we must correct, not people’s natural responses to its exploitation.

If one outlines a system to raise consciousness of the issues without providing valid alternatives in detail, what’s the point?

The alternative to oppression is no oppression, not an “alternative” form of oppression. What would would be “valid alternatives” to concentration camps or slavery, other than total abolition? I think you harbor a residual belief, maybe unconscious, in the idea of psychiatry as a “failed” system of support, when it is primarily a police force.

Report comment

After being in contempt of Parliament a few days ago Theresa May has abscoded with 39 billions worth of crown jewels to the EU, and is actively trying to flog our country. Clearly she has committed treason and needs to be arrested and placed in the Tower of London as soon as she sets foot back in the UK and until John Bercow can restore order. Now where are those 48 letters Captain Mainwaring ?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVqg3Oz0KbI

Report comment

Wow! That looks like a Monty Python sketch without punchlines or songs.

Report comment

Oh dear! I’m the loud American who married a Brit. This is literally my house every day.

Report comment

Really nice article, thanks for sharing this.

Report comment

I disagree that this is simply the psychiatric system doing this. Medicine pathologizes everything it doesn’t understand as psychiatric/psychosomatic. And society (politicians, media, art, experts, etc) reinforce this narrative constantly.

https://www.lymedisease.org/members/lyme-times/2018-fall-advocacy/netflix-afflicted-me-cfs/

Report comment

No KS, not just the psych system. But this pseudo-science invented solely to destroy/sterilize “criminal types” has infected all the legitimate medical branches as well.

Psychiatry is the cancer of medicine.

Report comment

People are not “more MI”. There is not more people ‘affected’.

What we do have is an overpopulated world that is racing ahead, each to his own. The community is gone. The need to be in a community for birthing, child rearing, movement, has all been replaced by something artificial that does not gel with our instinctive drives. Anxiety is what we are born with. People in cavemen days I’m sure became “depressed” if faced with food shortages. Even criminal.

There is no “mental illness”. There is no rise in “mental illness”. There is a rise with psychiatry naming every adaptive function as an “MI”.

How can there be a “mental illness” without psychiatry?

And how could psychiatry be the answer to it’s own confused view of natural phenomena, when they beat up on this phenomena and try to silence it, in fact call evolution a disease, and have created a cesspool of division between people?

A society that starts seeing adaptive behaviour as illness, risks something much greater than stigma.

And psychiatry getting their hands on children, to reform, to make conform is a descent into further darkness.

They will indeed reap the havoc they created. It is a given.

Report comment

John, I generally applaud your article.

I do find the that phrases such as,”responsibility of the person”, and the touting of “support” simplistic.

We know that people do not know how to be certain things and spend a lifetime trying to fit in.

The “support” which everyone speaks of, well they want someone else to give that support.

So possibly we don’t need people to be more than they can be.

Of course we can say that it sounds like a defeatist attitude, but we have to be careful that our views of how people should be is not a replacement for psychiatry.

I can use all the empowering talk I want on someone, and they might just not be at that place and not through what we see as “choice”. We judge “choice”, only from our ability to make choices. “choice” is a debatable word.

Report comment