In its May 25, 2021 issue, JAMA published a report on the comparative efficacy of two medications for treating preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD. Both methylphenidate and guanfacine were deemed to be beneficial, and in an accompanying editorial, JAMA told of how this retrospective review of patient charts added to the evidence base for this practice.

The editorial’s first paragraph, which was written by Tanya Froehlich, a professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, set forth a medical context for the study:

“Recognition of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the preschool age group is on the rise, with an increase in preschool ADHD rates in US nationally representative samples from 1.0% in 2007 to 2008 to 2.4% in 2016. Having a preschool-age child (i.e., 3-5 years) with ADHD is associated with numerous negative outcomes in the home (e.g., disordered parent-child relationships, elevated family stress), as well as out of-home settings (e.g., impaired preacademic skills, peer interaction difficulties, expulsion from preschool and childcare settings), underscoring the importance of identification and treatment. Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Society for Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics (SDBP) recommend behavioral interventions as first-line treatment for preschool-age children with ADHD. However, behavioral interventions alone do not sufficiently improve ADHD-related symptoms and impairment in a large percentage (>80%) of children.”

That opening paragraph makes a number of “evidence-based” assertions: that ADHD is a valid disorder; that it can be reliably diagnosed in preschoolers; that there is progress being made in recognizing this disorder in this age group; that untreated ADHD in preschoolers leads to bad outcomes in home and childcare settings; and that behavioral treatment fails to resolve ADHD symptoms in most preschoolers. There is scientific reason to conclude that there is a pressing need to study drugs being prescribed to preschoolers so diagnosed.

The editorial’s second paragraph asserts that clinical trials have already shown methylphenidate to be an effective treatment. The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline, Froehlich writes, recommends “stimulant methylphenidate as initial pharmacotherapy for preschool-age children with ADHD because it is the medication with the most evidence of efficacy and safety in this age group.”

The need for this effective drug to be compared to guanfacine is that “alternative medication options are sometimes needed given the diminished efficacy and higher rates of adverse effects associated with methylphenidate in preschool-age children compared with school-age children.” Organizations such as SDBP and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s Preschool Psychopharmacology Working Group recommend a2-adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine when a preschooler doesn’t tolerate methylphenidate well, even though the “evidence base is remarkably limited regarding management of ADHD” with these drugs in this age group.

In short, the editorial is promoting the notion that prescribing methylphenidate to preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD is an evidence-based practice, and now, with this retrospective review of charts for toddlers treated either with methylphenidate or guanfacine, there is evidence being gathered to support guanfacine’s use in this age group as well.

Yet, imagine this thought experiment. If the “evidence-based” assertions were removed from the discussion, what would most people think about giving a three-year-old who “talks excessively” or “who is easily distracted” a 5 mg dose of methylphenidate three times a day, which is a dosage deemed “optimal” in toddlers?

They would likely think it was a form of child abuse. Indeed, an adult who gives methylphenidate to a two-year old without a prescription is understood to have committed a federal crime.

That’s the power of an assertion that a practice is “evidence-based.” It flips that instinctual thinking. An act that seems to be a form of child abuse, doing evident harm to the child, is understood to be a helpful medical treatment.

Psychiatry’s Evidence Base for Preschool ADHD

Turn the clock back to 1979, and there would have been very few pediatricians or child psychiatrists who would have prescribed stimulants to preschool children. Psychiatry’s construction of an evidence-base for this practice, which began to take off in the 1990s, consists of three claims:

- ADHD is a neurological disorder characterized by genetic and brain volume abnormalities.

- ADHD can be reliably diagnosed.

- Methylphenidate is a safe and effective treatment for preschoolers “with ADHD.”

If there is good science behind these claims, then it could be argued that medicating preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD is a helpful treatment. If the claims are based on biased and misleading interpretations of research findings, then this is a practice without a scientific justification, and the specter of child abuse comes into view.

Genetic and Brain Volume Abnormalities in ADHD

The diagnosis of “attention deficit disorder” was created in 1980, when the American Psychiatric Association (APA) published the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III). There was no such diagnosis in the two prior editions of the DSM, and when the APA published DSM-III, it adopted a disease model for diagnosing and treating mental disorders. In her 1984 book The Broken Brain, Nancy Andreasen—the long-time editor in chief of the American Psychiatric Journal—set forth this new conception: “The major psychiatric illnesses are diseases. They should be considered medical illnesses just as diabetes, heart disease and cancer are.” The thought was that “each different illness has a different specific cause.”

This conception of psychiatric disorders meant that “attention deficit disorder,” from the outset, would be conceptualized—and treated—as a medical/biological problem, with the thought a line could be drawn that separated the ADD child from the normal child. That diagnosis soon morphed into Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

However, with the APA having adopted this disease model, research into the biology of ADHD was tainted from the start. Psychiatric researchers did not design their studies to assess whether those diagnosed with ADHD suffered from a brain illness (or abnormality). They sought to find such abnormalities to validate the disorder the APA had created. Researchers have focused on three such possibilities: chemical imbalances, genetic associations, and abnormalities in brain structures (or size).

In the 1980s and 1990s, the chemical imbalance theory of mental disorders was all the rage, a theory born from discoveries of how psychiatric drugs acted on the brain. Antipsychotics block dopamine receptors in the brain, and so researchers hypothesized that schizophrenia was due to too much dopamine in the brain. Antidepressants up serotonergic activity, and so researchers hypothesized depression was due to too little serotonin. Ritalin (methylphenidate) increases dopamine activity and so ADHD was hypothesized to be due to too little dopamine.

Today, the chemical imbalance theory of mental disorders has been mostly discarded. As Kenneth Kendler, co-editor in chief of Psychological Medicine wrote in 2005, “We have hunted for big simple neurochemical explanations for psychiatric disorders and not found them.” While advocacy organizations, such as CHADD, may still inform the public that “people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may have different levels of dopamine than neurotypical people,” this pathology is no longer posited as a primary feature of ADHD in the medical literature.

Although no specific gene (or genes) for ADHD have been found, ADHD experts now regularly tell of how there is a genetic element that contributes to its “heritability.” The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement, which was published in September 2021, asserted that there is a “polygenic cause for most cases of ADHD, meaning that many genetic variants, each having a very small effect, combine to increase risk for the disorder. The polygenic risk for ADHD is associated with general psychopathology and several psychiatric disorders.”

A 2010 study published in The Lancet is often cited as proof of this “polygenic” component. The study compared whole genome scans of 366 children diagnosed with ADHD with those of 1047 non-ADHD children. In a press release, the authors of the study stated “now we can say with confidence that ADHD is a genetic disease and the brains of children with this condition develop differently to those of other children.”

ADHD children, if the press release were to be believed, had been found to have genetic abnormalities that weren’t present in “normal” children. But as UK psychiatrist Sami Timimi wrote in his book Insane Medicine, which was serialized on Mad in America, the actual data didn’t support that conclusion.

The researchers reported that 15.7% of the ADHD group had “copy number variants”— abnormal bits of genetic code known as CNVs—in their genomes, compared to 7.5% of the control group. This meant that 84% of the ADHD group did not have this polygenic abnormality, which means that this abnormality, in fact, was not characteristic of those so diagnosed.

A 2017 article in Genome Medicine is an example of research that has led to the second part of the genetics claim, which is that there is a polygenic abnormality common to neuropsychiatric disorders. In the study, an international group of investigators reported that they had found CNVs on two genes (DOCK8/KANK1) significantly more often in those diagnosed with ADHD and four other psychiatric disorders than in healthy controls. This was evidence, they wrote, of a “common genetic component involved in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders.”

Here is the data for the ADHD group. Of the 1,241 youth in the ADHD cohort, four—0.32%—had CNVs in these two genes. That meant that 99.7% of the ADHD group didn’t have this genetic abnormality. However, since only 0.1% of the control group had this abnormality, the authors concluded that the ADHD patients were three times more likely to have it than healthy controls.

The data was similar for the other four psychiatric disorders. In total, only 32 of the 7,849 people with a psychiatric diagnosis had a CNV abnormality in their DOCK8/KANK1 genes (0.4%). There was an increased “odds ratio” that this abnormality occurred in those diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, but it occurred so rarely that this difference was meaningless. The “odds ratio” calculations were an example of science employed to mislead, rather than to inform.

The flaws with the brain volume research are much the same. The studies involve averaging volumes in an ADHD group compared to non-ADHD controls, and while the effect size differences in these composite comparisons are quite small, meaning that there is a great overlap in the distribution curves of volumes for both groups, the research is cited as evidence of brain differences in individuals with ADHD.

In 2017, Lancet published a “mega-analysis” of such studies. The 82 authors declared that theirs was the largest dataset of its kind. It was composed of MRI scans measuring brain volumes in 1,713 people diagnosed with ADHD and 1,529 controls, with this research having been conducted at 23 sites around the world. Theirs was a definitive study, and they declared it showed that individuals with ADHD had smaller brains than normal.

“The data from our highly powered analysis confirm that patients with ADHD do have altered brains and therefore that ADHD is a disorder of the brain,” they wrote. “This message is clear for clinicians to convey to parents and patients, which can help to reduce the stigma that ADHD is just a label for difficult children and caused by incompetent parenting.”

Headlines in CNN, Newsweek, WebMD and other media all echoed this claim. “Study finds brains of ADHD sufferers are smaller,” Newsweek wrote.

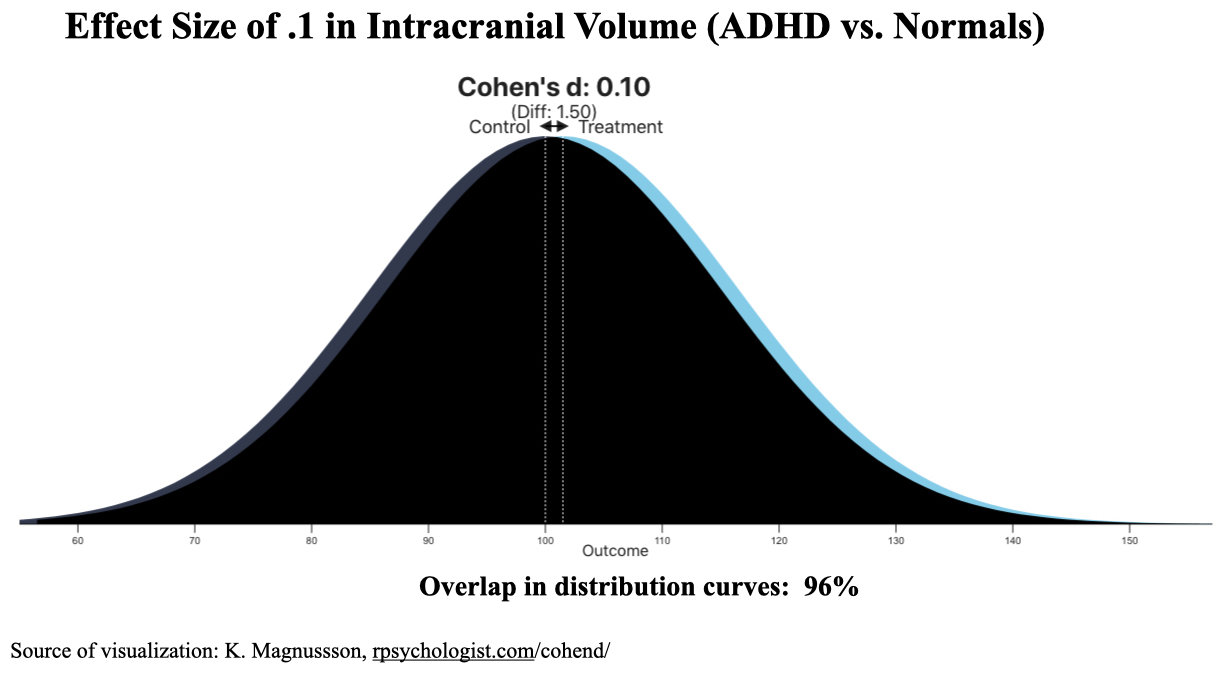

However, this conclusion was belied by the effect sizes that the researchers reported for the various brain volume comparisons. The Cohen’s D effect sizes ranged from 0.01 to 0.19, meaning that the distribution of brain volumes in the two groups, in comparison after comparison, were nearly identical. The effect size for “intracranial volume” was 0.1, which is depicted in the graphic below:

With an effect size of 0.1, there is a 96% overlap between the two groups. Pick a random individual diagnosed with ADHD in the study, and there would be a 47% chance that he or she would have a bigger brain than the median of the control group (and a 53% chance to have a smaller brain than the median.)

While such research is easily deconstructed, it is the conclusion drawn by the authors that gets entered into the ADHD evidence base. These findings are then incorporated into consensus statements, medical textbooks, clinical guidelines, and information provided to the lay public.

Here is a sampling of this process:

The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: “Findings from genetics or brain imaging . . . indicate a consistent set of causes for the disorder.”

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: “ADHD is a brain disorder. Scientists have shown that there are differences in the brains of children with ADHD . . . Research has shown that some structures in the brain in children with ADHD can be smaller than those areas of the brain in children without ADHD.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “Although the exact causes of ADHD are not known, research shows that genes play a role.”

WebMD: “Experts aren’t sure what causes ADHD. Several things may lead to it, including . . . genes, chemicals, brain changes” (and more).

The root cause of this misinformation is that ever since DSM-III was published, psychiatric researchers have been searching to identify biological causes for ADHD, and with that impulse in play, they have regularly misrepresented their own data. Very small group differences compared to controls are represented as abnormalities found in individuals diagnosed with ADHD, even though the study data, when properly parsed, show that not to be true.

Indeed, once the data are reviewed, here is the finding that comes clear: Decades of research into the “biology” of ADHD failed to find any pathology that was characteristic of individual children so diagnosed. The search for chemical imbalances, ADHD genes, and brain volume abnormalities all turned up negative. Any reported group differences in the genetic and brain volume studies were quite small and showed that most ADHD children fell within “normal” limits.

ADHD Can Be Reliably Diagnosed

Psychiatry’s declaration that ADHD has genetic and biological underpinnings leads to the conclusion that it is a discrete disorder that can exist in preschool children (or is a disorder present at birth that will become manifest as the child develops.) However, for the prescribing of methylphenidate to be considered “evidence-based,” a second conclusion must be drawn, which is that this discrete illness can be reliably diagnosed in preschoolers. Otherwise, such prescribing practices would lack a medical justification and treating toddlers who might not have this condition with a stimulant could be seen as doing great harm.

The National Drug Intelligence Center even makes this point: methylphenidate is safe only when prescribed “for a legitimate medical condition.” Otherwise, it should be considered a drug of abuse, one that can cause “psychotic episodes, cardiovascular complications, and severe psychological addiction.”

As is well known, there is no biological marker for diagnosing ADHD. From its inception, the diagnosis has been made on an assessment of behaviors—inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity—said to be symptoms of the disorder. The specific criteria for the diagnosis have changed with each iteration of the DSM, with each updated volume making it easier to make the diagnosis. Prevalence studies reflect this expansion, with the percentage of youth said to have ADHD increasing from 3% in the early 1980s to 5% after DSM-IV was published in 1994, and to 10% in the DSM-5 era.

While the changing criteria and prevalence studies tell of a diagnosis that is a construct, as opposed to an illness found in nature, the ADHD professional community has steadfastly maintained that it is a “real” disorder that can be reliably diagnosed. The field has created an evidence base for this belief, in large part through its use of rating scales to measure the symptoms set forth in the DSM.

Psychiatry, of course, has created rating scales for all of its major disorders, which quantify symptom scores and thus lend an aura of scientific objectivity to the diagnoses. The rating scales may also be used to draw a theoretical line separating those who meet the criteria for the disorder and those who do not, which is how the ADHD rating scales are used.

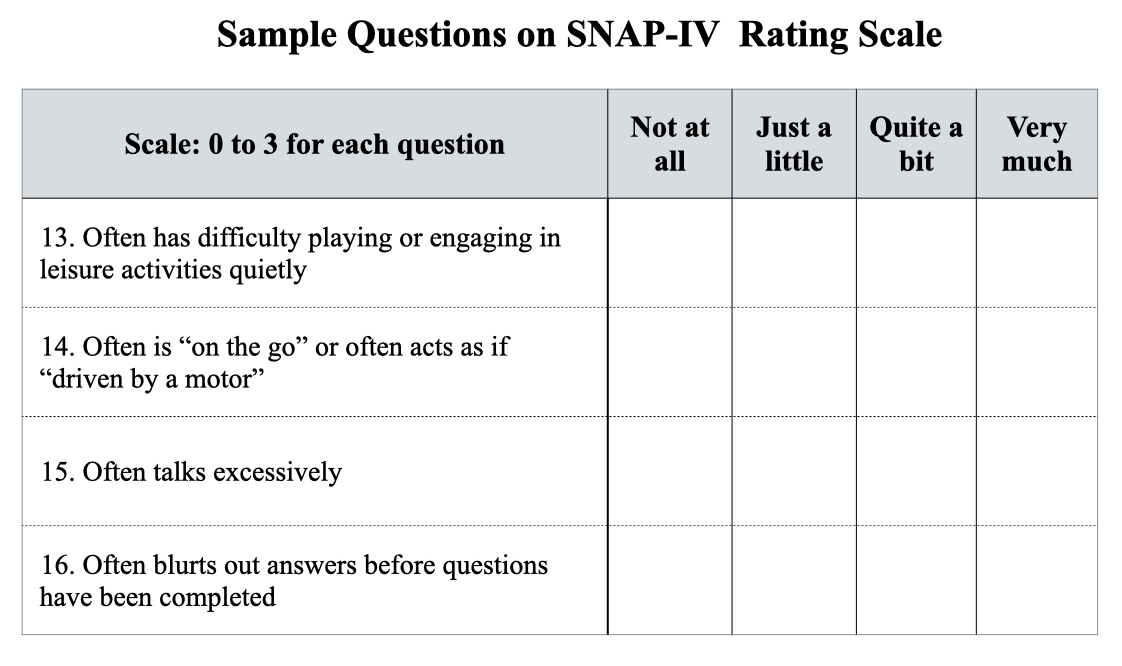

One such tool is the SNAP-IV Teacher and Parent Rating Scale, which was created after DSM-IV was published. The ADHD questionnaire lists nine behaviors related to the “inattention” domain and nine behaviors related to the “hyperactivity impulsive” domain, with the parent or teacher rating the presence of the behavior on a scale of 0 to 3 (0 = not at all, 1 = just a little, 2 = quite a bit, 3 = very much).

The possible range of scores is 0 to 27 for each of the two subtypes. SNAP guidelines define scores less than 13 as “not clinically significant,” and scores above that line of demarcation are categorized as mild, moderate, or severe symptoms of ADHD. Here is the SNAP scoring table:

Not clinically significant: < 13

Mild symptoms: 13 – 17

Moderate symptoms: 18 – 22

Severe symptoms: 23 – 27

Another such tool is the Vanderbilt assessment scale. Today, a parent or teacher can go online, answer questions related to the frequency of a child’s symptoms and performance in school, push the “calculate” button, and immediately learn whether the child “meets criteria” for the disorder and its various subtypes. It’s a yes or no bottom line.

When SNAP, the Vanderbilt, and other ADHD rating scales were introduced, other researchers then assessed their “reliability” and “validity.” These assessments are difficult to understand, but methodologies are discussed, numbers are crunched, tables of statistics are published, and a conclusion is drawn about the scales’ merits. A 2003 review published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry gave them all excellent grades: ADHD “rating scales can reliably, validly, and efficiently measure DSM-IV-based ADHD symptoms in youths,” the authors wrote. “They have great utility in research and clinical work.”

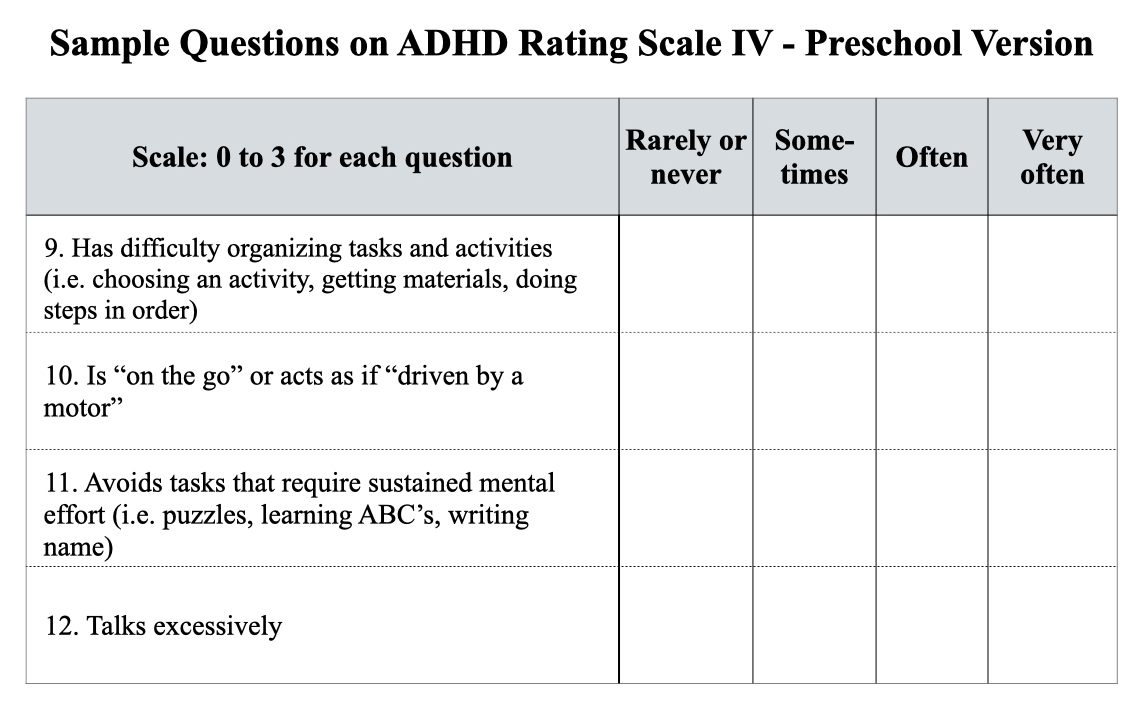

The rating scales developed after DSM-IV was published in 1994 were deemed useful for measuring symptoms in school-age children. The thought at that time—the late 1990s, early 2000s—was that ADHD couldn’t be reliably diagnosed in preschool children, as even “normal” three-year-olds were often inattentive, impulsive, and ran about like they had motors inside them. But then physicians began prescribing stimulant medications to toddlers with behavioral problems, and that led to the release of the ADHD Rating Scale IV, Preschool Version.

This scale is similar in kind to the SNAP-IV, with 18 questions scored on a scale of 0 to 3. Scores are tallied compiled for inattention subtype, hyperactivity/impulsivity subtype, and composite type. The cutoff for symptoms “suggestive” of ADHD is the 93% percentile mark, i.e. scores in the top 7% are seen as meeting criteria for a diagnosis.

Although the rating scales are not supposed to be used to make a diagnosis, they are said to identify children who need to be referred to a psychiatrist for a diagnostic evaluation. The numerical scores promote an understanding, which permeates the medical literature, that there are children “with ADHD,” and children “without ADHD,” a description that signals there is no in-between space. A child either has the “neurological” disorder or doesn’t.

In 2002, Russell Barkley and other prominent figures in the ADHD world published an “International Consensus Statement on ADHD” that made this point clear. Evidence that ADHD was a “real medical condition,” they wrote, was so abundant that to question its validity was “tantamount to declaring the earth flat, the laws of gravity debatable, and the periodic table in chemistry a fraud.”

The recently published World Federation International Consensus Statement made a similar claim, albeit in more moderate language. ADHD was a “valid disorder” and the fact that it could be reliably diagnosed was an essential part of the evidence establishing its validity. “Well-trained professionals in a variety of settings and cultures agree on its presence or absence using well-defined criteria,” they wrote.

However, just as the genetics and brain volume research can be easily deconstructed, so too can this assertion that ADHD is a distinct disease that can be reliably diagnosed. The pretense is self-evident.

While scales may spit out a bottom-line score, the assessing of symptoms is a subjective exercise. When does a toddler’s “difficulty organizing tasks and activities” fall into the “often” category, as opposed to the “very often” category? When does “talks excessively” move from the “sometimes” category into the “often” category? The scores change depending on which box the parent or teacher checks.

Even more to the point, the scores fall on a spectrum, and then cutoff numbers are arbitrarily drawn to distinguish those who “have” symptoms suggestive of ADHD and those who do not. Should the cutoff be one standard deviation above the mean? If so, this will mean that 16% of all children will have scores at the far end of the spectrum, and thus have symptoms suggestive of ADHD. Or should the cutoff be 1.5 standard deviations above the mean? If so, this will result in 6.5% of all children “meeting the criteria” for ADHD. The cutoff lines used in ADHD rating scales vary, with most drawing a cutoff within this range of 1 to 1.5 standard deviations above the mean.

None of this tells of a disease found in nature. The assessing of symptoms is a subjective exercise, symptom scores fall on distribution curve, and then a line—somewhere along that distribution curve—is arbitrarily set to identify those who meet criteria for the disorder.

Yet, it is the pretense—that ADHD is a discrete neurological disorder that can be reliably diagnosed—that rules in the medical literature and in the public mind. Articles in medical journals regularly tell of “children with ADHD” and children “without ADHD.”

This mindset is on display in the JAMA editorial. The title is “Comparison of Medication Treatments for Preschool Children With ADHD.” The first word in the editorial then reifies that understanding. The writer does not tell of an increase in the in the diagnosis of ADHD in preschoolers, but rather of how recognition of ADHD in preschoolers has increased.

That is a difference in word choice that reveals all. And it sets the table for the field to declare that prescribing stimulants to preschool children is a helpful thing to do.

The Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS)

The science reviewed above, if interpreted in an unbiased manner, tells of how ADHD is a diagnostic construct that groups together children with certain behaviors that impair their ability to function in certain environments (at least in the eyes of teachers and parents). The biology that may be associated with such behaviors is unknown, and no specific biology—genetic or brain abnormality—has been found that is common to all those so diagnosed. There is a distribution curve in the ratings of behaviors said to be characteristic of ADHD, and those so diagnosed fall at the far end of that curve.

With that conception, arising from forty years of research, one possible societal response would be to see if changing the child’s environment could be helpful, which could include society creating more nurturing environments for all children. The problem doesn’t necessarily lie within the child, but rather arises from the child’s response to his or her environment. Society could see the “prevalence” of the disorder as a marker of distress in society. However, the understanding that ADHD is a distinct disorder, characterized by genetic and brain abnormalities, and that this disorder can be reliably diagnosed, leads to the conclusion that a medical intervention is warranted.

While behavioral treatment may be the initial intervention offered to preschoolers, when a disorder is said to lie within the individual, drug treatment quickly becomes a go-to intervention, particularly once a drug has been deemed to be “safe and effective.” The NIMH’s Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS), which was conducted in the early 2000s, is cited as providing evidence for prescribing methylphenidate to this age group.

The inclusion criteria required the toddlers to score above the 93rd percentile on the Conners Parent and Teaching rating scales for ADHD (1.5 standard deviations above the mean). There were 303 preschoolers enrolled into the study, which had a complicated multi-phase design.

Here are the results from each phase of the study:

1. Parent-training: Before the 303 children were exposed to methylphenidate, the parents were given a 10-week parent training course, and if a child significantly improved during this period, the child did not continue to the next step of the study. Many parents also dropped out during this period. This left 183 preschoolers who entered the drug-testing phases of the study.

2. Tolerability test: The 183 children went through four weeks of open-label treatment to see if they could tolerate the drug, and those who could not, as evidenced by their experiencing adverse effects, were removed from the study. Fourteen children were discontinued during this phase.

3. Assessment of a “best dose” response: 165 children entered into a five-week “titration” study. Each week, a child would be prescribed a different dose of methylphenidate administered three times a day (1.25 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg, and 7.5 mg), with the fifth week a placebo dose. At the end of each week, parents and teachers assessed the children’s symptoms on two rating scales to ascertain how they had fared during the seven days on that particular treatment.

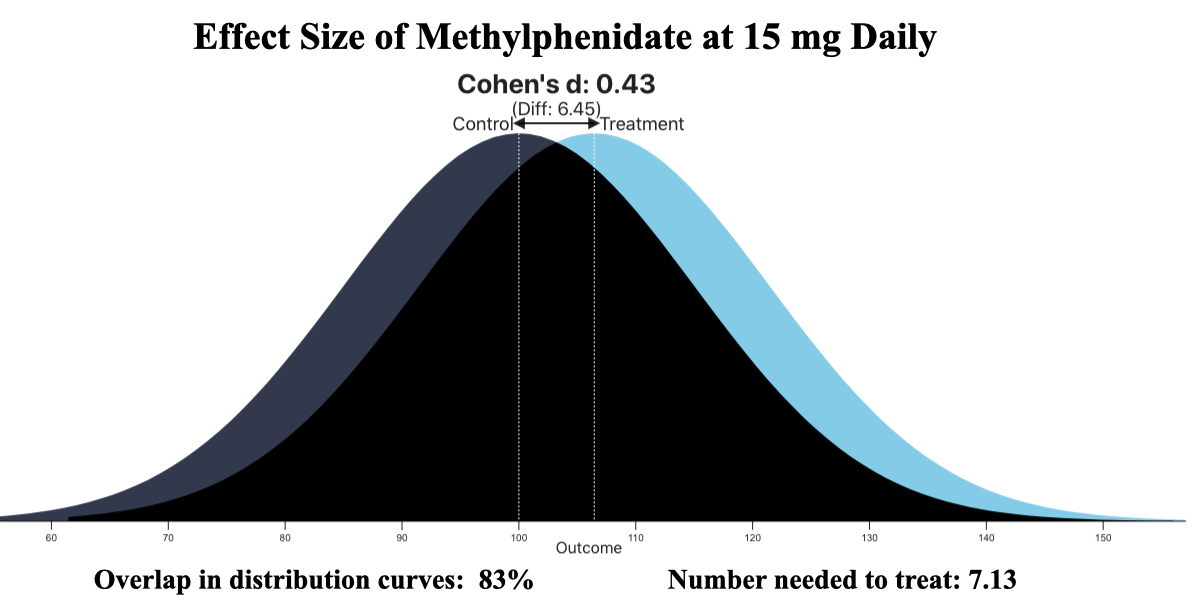

The researchers reported that there were significant decreases in ADHD symptoms during the weeks the toddlers were on a 2.5 mg, 5 mg, or 7.5 mg dose of methylphenidate compared to their week on placebo. Only the 1.25 dose failed to provide this benefit. The effect sizes for the three “effective” doses were small, with an effect size of 0.43 for the 15 mg daily dose deemed the “optimal dose” of methylphenidate for this age group.

During the five weeks, the top five adverse events spontaneously reported by parents were decreased appetite, emotional outbursts, difficulty falling asleep, irritability, and repetitive behaviors or thoughts. These adverse events occurred more frequently during the weeks they were on methylphenidate than during their week on placebo.

4. Randomization phase: After the titration trial, the blind was broken to identify the specific dose of methylphenidate the child had done best on (or whether a child had markedly improved during the week of placebo treatment). Then, following a 24-hour washout, the 114 toddlers still in the trial were randomized to their “best dose” of methylphenidate or to placebo. The primary outcome was “excellent response” at the end of four weeks as measured on the SNAP scale. Twenty-one percent of the methylphenidate cohort achieved that response compared to 13% of the placebo group, a difference that was not statistically significant. Only 77 of the 114 finished the four weeks of treatment.

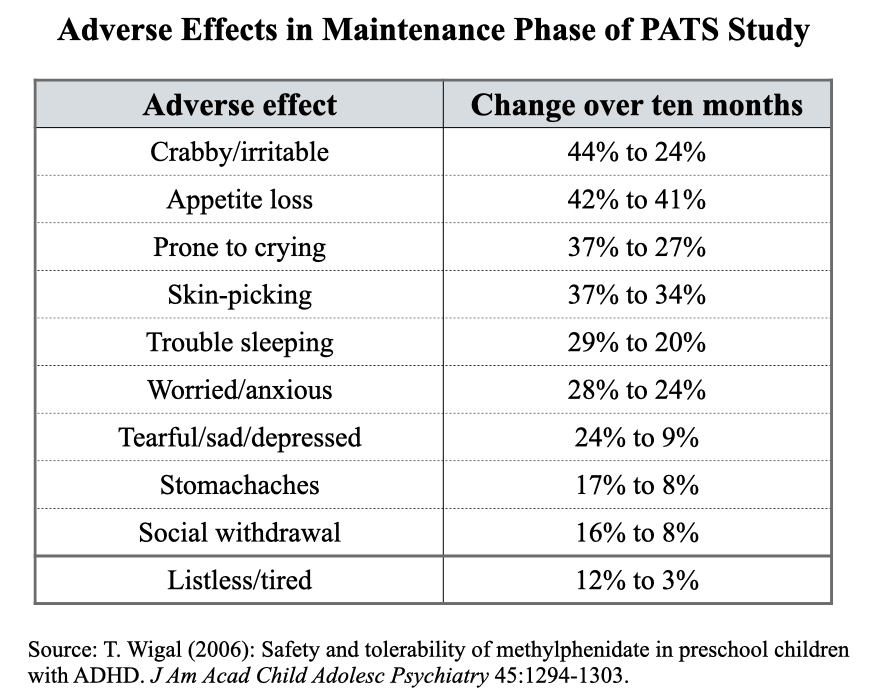

5. Open label maintenance: All of the children enrolled into the methylphenidate phases of the study were eligible for 10 months of open-label treatment, with this phase designed to assess the longer term “safety and tolerability” of methylphenidate. One hundred forty children entered this study, with the percentage suffering various adverse events charted at the start of the 10 months and again at the end, with the thought that the percentage would decline as the preschoolers became more accustomed to the drug. The table below details the findings:

In addition, of the 95 children who remained on methylphenidate for the 10 months, annual growth rates were 20% less than expected, and weight gain was 52% less than expected.

In addition, of the 95 children who remained on methylphenidate for the 10 months, annual growth rates were 20% less than expected, and weight gain was 52% less than expected.

Deconstructing PATS

Once the PATS trial is detailed in this way, what conclusions can be drawn? The first is that parents of 120 of the 303 preschoolers enrolled into the trial decided—after the parent training phase—not to expose their child to methylphenidate. That’s 40% of all parents.

The second is that the efficacy of methylphenidate, on a primary outcome measure, only appears during the five-week titration trial, which involved comparing reduction of ADHD symptoms during the weeks they were on methylphenidate to the week they were switched to placebo.

The third is that the titration trial was biased by design against placebo. The placebo period began with the toddlers being abruptly withdrawn from whatever dose of methylphenidate they had been on, and given that discontinuation studies of methylphenidate have found that behavioral symptoms often rapidly worsen following abrupt withdrawal, it could be expected that the behavior of many of the toddlers would deteriorate during their seven days on placebo.

Yet, even with this biased design, at the 15 mg daily dose that was deemed optimal, the “effect size” was only 0.43. With this effect size, the number needed to treat is 7. You would need to treat seven preschoolers with methylphenidate to produce one additional favorable outcome (in terms of reduction of symptoms.) The other six are exposed to the hazards of the drug without any benefit beyond placebo.

The fourth is that there is no evidence anywhere in this trial of the preschoolers treated with methylphenidate functioning better. In the parallel phase study, the primary outcome was achieving an “excellent response,” which presumably would lead to better functioning, but there was no statistically significant difference between “best dose” of the drug and placebo. Indeed, of the 183 toddlers who were exposed to methylphenidate, there were only 13 ever described as having an “excellent response” while on the drug.

Meanwhile, the toddlers put on methylphenidate frequently suffered moderate to severe adverse events, and the 10-month maintenance phase told of toddlers that, while being treated with methylphenidate, were often crabby, prone to crying, picking at their skin, having trouble sleeping, worried, and without much of an appetite. At the end of 10 months, they were notably shorter and lighter in weight than they normally would have been.

The Flaw in Evidence-based Medicine

The bottom line-conclusion drawn from this study—that methylphenidate is a safe and effective treatment for preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD—reveals a flaw that is baked into “evidence-based” prescribing of medications. If a trial finds that a drug produces a greater reduction of symptoms than placebo, with the difference “statistically significant,” then it is deemed to be an effective treatment for the related disease, and regularly prescribed to all those so diagnosed. But that endpoint—reduction of symptoms better than placebo—is just one data point among many produced in a trial of a drug, and an examination of this broader collection of data is needed to assess its likely overall impact on a diagnostic group.

What you find in the PATS trial is the following:

- Many toddlers apparently got better with parent training as a first intervention.

- Of the 183 children exposed to methylphenidate at some point during the study, 21 “discontinued treatment because of intolerable methylphenidate adverse events.”

- The effect size in reduction of symptoms during the titration phase was small, such that at an optimal daily dose of 15 mg, six of seven toddlers treated with methylphenidate will suffer the adverse effects of the drug without any additional benefit beyond placebo in reduction of ADHD symptoms.

- In the randomized four-week trial, only 21% had an excellent response to the drug, compared to 13% in the placebo group. This means that if you medicated 100 preschoolers with methylphenidate, there would only be eight additional “excellent responders” than there would have been otherwise.

- Adverse effects on methylphenidate were frequent and told of behavioral deterioration, particularly in the 10-month maintenance phase.

- At the end of 10 months, the toddlers were shorter and weighed less than normal.

That is the picture that emerges from a recap of all the data. If you do the math, there is only a small percentage of preschoolers—10% to 15%—that could be said to enjoy a benefit from the treatment in terms of reduction of symptoms over the short term. That means that 85% or so of all toddlers treated with methylphenidate will experience the adverse effects of that drug without receiving any additional benefit, a net result that tells of harm done.

Yet, in evidence-based medicine, there is a hyper focus on symptom reduction, with even a small effect size deemed proof of efficacy, and that is how the PATS trial led to a conclusion that methylphenidate is a safe and effective treatment for toddlers diagnosed “with ADHD.” As the JAMA editorial states, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends methylphenidate as “initial pharmacotherapy for preschool-age children because it is the medication with the most evidence of efficacy and safety in this age group.”

One final note on the PATS trial: in the published report of the safety and efficacy results, the authors collectively disclosed 72 “relationships” with pharmaceutical companies, with the manufacturers of ADHD drugs prominent on the list of disclosures.

The PATS Follow-up: A Childhood on Drugs

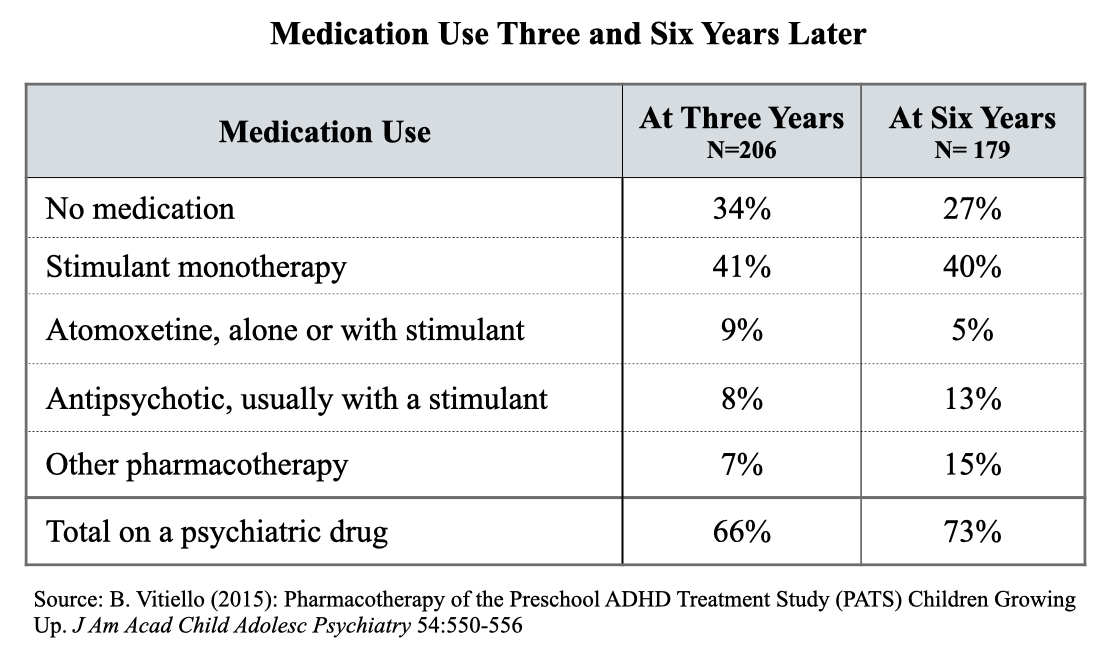

Even with the 10-month maintenance phase, the PATS trial didn’t provide insight into how the lives of these toddlers unfolded over the longer term once they had been diagnosed as “having ADHD.” However, PATS investigators did conduct two follow-up assessments of their ongoing medication use, at three and six years, and the results are heartbreaking.

Here are the results:

The findings tell of stolen childhoods. These children were diagnosed with ADHD as preschoolers and that turned two-thirds of them into persistent mental patients who grew up constantly on psychiatric drugs. At their tenth birthdays, this group would have no memory of being alive without the mind-altering effects of psychiatric drugs.

The findings tell of stolen childhoods. These children were diagnosed with ADHD as preschoolers and that turned two-thirds of them into persistent mental patients who grew up constantly on psychiatric drugs. At their tenth birthdays, this group would have no memory of being alive without the mind-altering effects of psychiatric drugs.

Which begs the next question: What fate awaits as they move into their teenage years and into adulthood? While there are long lists of adverse effects associated with longer-term use of stimulants and other psychiatric drugs, which collectively tell of impaired physical health and social development, there is an absence of good research on how such drugs may fundamentally alter brain development over time. However, there have been animal studies studying the effects and those studies have sounded an alarm.

For example, repeated exposure to stimulants was found to cause rhesus monkeys to exhibit “aberrant behaviors” long after the drug exposure had stopped. Preadolescent rats treated with stimulants moved around less as adults, were less responsive to novel environments, and showed a “deficit in sexual behavior.” Such findings have led at least a few investigators to conclude that stimulants may damage the brain’s “reward system,” and thus to a concern that medicating a child may produce an adult with a “reduced ability to experience pleasure.”

Aberrant behaviors, a deficit in sexual behavior, a reduced ability to experience pleasure . . . if these animal studies are any guide, preschoolers prescribed stimulants for ADHD, who then stay on this medication as they grow up, will have sharply diminished lives as adults because of this “medical intervention.”

The Bottom Line

The JAMA editorial was occasioned by a report, based on a retrospective review of pediatric health records, that compared the risks and benefits of guanfacine to methylphenidate when prescribed to preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD. The authors reported that both drugs led to improvements in the majority of children “with differing adverse effect profiles.”

The accompanying editorial told of how this was a “first step toward addressing a critical gap” in the evidence base for treating preschool ADHD. Both drugs are now being routinely prescribed to toddlers, and, the editorial argued, it was important to ascertain which class of drugs should be the preferred drug treatment for this age group. Randomized clinical trials comparing guanfacine to methylphenidate would be a vital next step in the evidence base supporting such prescribing.

The editorial stirred a different question investigated in this Mad in America report: How is it that the medical community came to think that prescribing stimulants to preschoolers on a daily basis was a helpful thing to do? What was the makeup of the “evidence base” that could lead to such a practice? While one can be skeptical of the motivations of those who construct the evidence base, the motivation of pediatricians who follow it, prescribing methylphenidate in ways recommended by clinical care guidelines, is not subject to such skepticism. Pediatricians pick that specialty because they want to be promoters of health in newborns and the young.

Thus, the focus of this MIA report is how “evidence-based” medicine, particularly when constructed in the squishy scientific realm of psychiatry, can do harm. In this case, you find a story of researchers seeking to find evidence of a disease, which could then be used to validate a diagnostic construction drawn up by a medical guild, drawing conclusions that weren’t supported by the data. Pretense snuck into the “evidence base,” and then came the fatal flaw regularly cooked into conclusions drawn from clinical trials, which is that a slight reduction of symptoms translates into evidence of a “safe and effective” drug, even though most patients may be receiving no benefit. In that way, you end up with an “evidence base” for prescribing stimulants daily to a three-year-old.

There is one other way that “evidence-based” medicine fails in this instance. There is never any consideration of a fundamental question: What rights does the child have? Preschoolers are in the first stage of their journey into the mysterious world of life, and if there is a core existential aspect to growing up, it is the experience of struggling to know one’s own mind, of one’s own essential makeup, and as part of that struggle, of gaining some control over one’s behavior. As the saying goes, you want to see what you can make of yourself. The medicating of preschoolers, with that medicating becoming a constant and often evolving into polypharmacy by the time they are in elementary school, robs them of that future.

That is a story of a great tragedy, of existential loss, and yet in American medicine today, it is recommended as an evidence-based treatment for the 2.6% of preschoolers—that’s one in every 38—said to “have ADHD.” Readers can decide whether this is a story of “evidence-based” medicine enabling a practice that, without that sheen of science, could rightfully be described as child abuse.

***

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

“ADHD was a “valid disorder” and the fact that it could be reliably diagnosed was an essential part of the evidence establishing its validity. ”

Validity, reliability and objectivity are not the same. This mistake is okay to make for first year students. Not so much for MDs and profs.

Let me make up Pizza Eating Disorder PED for this. The only question to assesss for PED is “do you like pizza?” “Yes” implies PED.

Obvioisly that is a reliable and objective diagnosis. Does that make it a valid mental illness? Uhm … no.

Note that PED could most likely be treated with stimulants aswell, as they reduce appetite.

‐—–‐——

“Evidence that ADHD was a “real medical condition,” they wrote, was so abundant that to question its validity was “tantamount to declaring the earth flat, the laws of gravity debatable, and the periodic table in chemistry a fraud.”

The shape of the earth, laws of gravity, and periodic tables are tested billions or even trillions of times per day, whenever you use any device reliant on them. Like the GPS on your phone.

The validity of ADHD is NEVER tested. There isn’t even a test.

—————-

Good job putting the effect sizes into a readily understood graph. Most psychiatric research is missing such graphs. Propably because it would show how BS said research is.

Report comment

lol, I love this response.. “The shape of the earth, laws of gravity, and periodic tables are tested billions or even trillions of times per day”

Report comment

Thanks.

The “stolen valour” and cheap rethorics by comparing psychiatrys “knowledge” to physics knowledge boggle my mind.

Psychiatry operates at 2 sigma significance. Physics at 7 sigma. That’s a difference of roughly 2000000 times less likelyhood of false findings.

Report comment

How probable is “two sigma” compared to random chance?

Report comment

2 Sigma means there’s a 5% chance to find a positive result even though there is no actual difference.

So if I did 20 studies on whether salt helps against cancer, on average one of them will find a statistically significant (to a 2-sigma or p=0.05 level of significance) difference between the group taking salt and the group taking placebo by pure coincidence.

Report comment

Thanks!

Report comment

Stole my fire. My first thought was that not putting “ADHD” in quotes in the title indicates an acceptance of the notion that “ADHD” is a thing in the first place, and that there are legitimate uses for people’s attention spans being artificially/chemically manipulated.

There are many things other people think I should be focused on which are meaningless to me, and I’m sure I speak for many children as well. Taking speed makes everything interesting, of course, but we’re talking about teaching disabilities just as much as learning disabilities — which one is the drug actually addressing?

Report comment

…and the bugbear (don’t talk about the war!) of parenting disabilities.

It’s hard for a kid to get his/her parent’s attention these days.

And that attention is essential for “treating” “ADHD.”

I like that they did parental interventions first, but still – the charts show that 66% are still drugged at 3 years, and 73% at 6 years. Egads. So this increase is interesting to me – I can see frustrated parents throwing their hands in the air, “just give him/her the drugs!”

Report comment

The approach used in Absurd MH Diagnosing reminds me a bit, of the how the medieval Witch Hunters operated.

(Witch Hunters Manual: Malleus Maleficarum)

Report comment

It is a crime that children with ADHD are ignored by those who profess expertise in this area. Interview adults randomly, if necessary, to discover from its victims what untreated, undiagnosed ADHD is like. Please. You may write 10,000,000 word essays on all the reasons it doesn’t exist and should not be treated with stimulants, and you still will not know the truth behind this nightmare.

Mine is a fair request, Robert, don’t you think? What could be the harm? Spend (invest) an hour of your busy schedule to talk with one of us to find out just what we experience first hand with and without meds. If you learn something, take more time to find out who we are and the pain we’ve known.

If anyone is truly interested in understanding ADHD, ask an adult who went through 12 years of schooling in hell; then 4 years of college in hell and 20 years in the “workforce” in hell.

Ask if she/he noticed any differences cognitively and in everyday living, once diagnosed and treated. Ask about schooling and work. I don’t believe you have the slightest notion what you are doing to those who died daily unable to pay attention.

Report comment

I am glad that you found stimulants helpful to you. But you continue to argue a point no one is making. And you are now getting insulting implying that those making these arguments don’t give a crap about the children involved. I can tell you that I spent over 30 years in the field of helping children and saw and talked to hundreds and hundreds of kids diagnosed with “ADHD,” as well as their parents, their teachers, their counselors, their siblings and others involved with them on a daily basis. So I am not basing my opinions on some intellectual exercise. They are informed by much direct experience, including with my own kids, and calling me “criminal” for drawing the conclusions I have made after decades of research and direct personal experience is most definitely beneath you.

Additionally, your personal experience is important, but does not mean that your own experiences are “average” or “expected” from all or most “ADHD” diagnosed people. In fact, decades of evidence show that there are no reliable improvements in ANY long term outcome areas for long-term stimulant use, including academic test scores, high school graduation rates, college enrollment, delinquency scores, social skills, employer satisfaction, or even self-esteem. However YOU may feel about YOUR treatment, or others you know, you can’t claim that children are being cheated out of this special advantage that science says does NOT happen for the large majority of recipients.

I’d really appreciate it if you can constrain yourself to presenting your personal experiences and such scientific data as you feel you’d like to share, as well as directly addressing the science and experiential data that has been presented to you in good faith, and leave off on the disparaging comments on individuals who happen to disagree with you, especially when those objecting have presented their own data to which you could choose to directly respond.

Bottom line, you have your experiences, others have their experiences, they aren’t going to be the same, and all such experiences are welcome to be shared. Please be respectful that not everyone is going to see things your way, and that disagreeing on science is not a personal thing.

Report comment

I thank you for your reply. I do understand that each person has different responses to even medication and each person has a different idea of the value of psychiatric diagnosis. It can be very heated at times. The issue is that many people who go this site have been harmed by psychiatry in some manner; either the drugs, ECT, the therapies, and even other treatments; some of the above, some or all of the above. I actually that many people are diagnosed improperly with alleged psychiatric illnesses when what they may have is a learning disorder or difficulty that is impacting their lives in some way. There are also those who do receive alleged psychiatric diagnoses when they are just going through a normal life change. Either way, most likely the drugs, the therapies and other treatments can force them onto a dark road which causes unneeded damage to the brain and body. Sometimes, many do not realize they are being damaged until they come to a crossroads in their life and their brain/bodies start rejecting the treatments. Children, as young as toddlers, are definitely too young to be subjected to this possibility. Sometimes, many of us forget the terror caused by the psychiatric drugs themselves which is usually augmented by some form of therapy. Thank you.

Report comment

PLEASE don’t refer to psychiatric toxins as “medications”!

Report comment

Or at least call them by their street names.

“Let’s give these kids speed.”

Report comment

JanCarol, You are right. Let’s call them by their “street names.” But would that not make them illegal and the ones who gave them these drugs, just your ordinary neighborhood drug pusher? I don’t know. Just a thought. Thank you.

Report comment

Thanks Bob

What the real evidence says – is that people that take Psychiatric drugs, have a tendency to end up “Psychiatric’.

Report comment

What an excellent article – once again Robert Whitaker lays out a comprehensive analysis of a complex problem in a way that all of us can understand. “That is a story of a great tragedy, of existential loss, and yet in American medicine today, it is recommended as an evidence-based treatment…” which leads us to accept treating many, many more than can benefit while simply ignoring the obvious physical side affects and absolutely NO IDEA what the side effects IN THE MIND might be. Staggering to me that a profession accepts this as a good outcome and seems incapable of seeing the problem. To pick out two ideas: “The number to treat” = 7 and an ‘observed’ = known side effect of 20% less growth than expected” do not seem like a good result. All this collateral damage for symptom reduction that isn’t even significant. All the symptoms in ADHD models are behavioral, rather than ‘mental’. The effect in the mind is neither understood nor considered.

The other obvious problem is how drug ‘safety’ is narrowly measured without any concept of ‘whole person’ pharmacovigilance. Robert – this may be an aspect you might look at in future?

In the same vein that the fact people who hear voices treated with antipsychotics experience emotional dulling that affects ALL experiences is simply ignored by psychiatry (THEIR opinion is it is an acceptable problem)… clearly the possibility of similar problems in the mind experiences of toddlers is simply not considered. And can’t be studied.

Abuse is too kind a word to summarize with.

I think we are dealing with criminal negligence.

Report comment

Did the author of the JAMA editorial state whether or not she received money from big Pharma?

I wonder, given my experience working with adults in community college, in terms of reading readiness and reading willingness (as well as the ability to find this article by Robert Whitaker on the Mad in America website) what percentage of parents of toddlers would or could read and digest this article?

The terrain just keeps getting scarier.

Reminds me of recent coverage that looked at preschool care and outcomes, which suggests playing may be better for poor preschool children than academics. Academic preschool programs for poor kids in Tennessee may be encouraging an anti-school attitude (like I believe old school one size fits all reading instruction turns many off from reading).

This isn’t the coverage I read, but NPR covered the study’s release.

https://www.npr.org/2022/02/10/1079406041/researcher-says-rethink-prek-preschool-prekindergarten

NPR: “But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.”

How many preschoolers studied for preschool effectiveness in the study I referenced were diagnosed and drugged? Maybe not many, given class dynamics, but still, for any academic discipline alone, especially psychiatry, to assume they have the right answers and willingly misrepresent? It’s heartbreaking for sure.

The wave of problems caused by psychiatry rolling back and aimed at American society is only getting bigger.

Report comment

I also think that “investigating” what should be clearly recognized as a crime against humanity, as though there could ever be a legitimate or “scientifically sound” justification for such child drugging, serves to confer an undeserved legitimacy on such practices, by deeming them worthy of “debate.”

Report comment

Thanks to people like Robert Whitaker there is growing awareness that psychiatry is the biggest and most damaging lie perpetrated on us ever

Report comment

Billions of dollars spent on neuroimaging studies of ADHD and other “mental illnesses” and not one patient in any clinic anywhere in the world has benefited.

Billions of dollars spent on genome-wide association studies studies of ADHD and other “mental illnesses” and not one patient in any clinic anywhere in the world has benefited.

Is this the modern-day equivalent of medieval scholastics debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

It’s time the taxpayers stopped pouring money down this particular black hole. Let’s take the money we spend on this research, along with the money we spend on drugging kids, and use it to hire more teachers and more teachers’ aides, and pay them more.

Report comment

It’s more like alchemy than anything else to me. Just keep experimenting and eventually you WILL find a way to turn lead into gold. Just because it hasn’t worked 100,000 times before is no reason to think it won’t work in the future!

Report comment

Yet since the definition of insanity is “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Wouldn’t that imply that it is the psychiatrists who are the insane people after all?

Report comment

Quite so!

Report comment

I just have to step in here. I know everyone says this but can anyone show me ONE dictionary with that definition of insanity?

Report comment

You actually could turn lead into gold with a particle accelerator. It would be insanely expensive and absolutely not worthwhile to do so, but it has been done with bismuth.

Because physics is an actual science that produces actual results.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/fact-or-fiction-lead-can-be-turned-into-gold/

Report comment

what about quantum science?

Report comment

Where is the Like button @Patrick Hahn!? This is an A+ comment

Billions of dollars – and who HAS been helped?

Report comment

This is an excellent article Bob! I appreciate your gift to be able to break down the scientific research and demonstrate that it is relatively hollow. Indeed, we live in an age where “science” has become a rather meaningless statement. Science can be an amazing investigative tool. However, it can also be used as a sort of “smoke screen” to deflect the attention of the public away from the malfeasance of certain stakeholders.

There is science and then there is “scientism” Science is the investigative tool and it is without question one of the most valuable tools we have. Scientism is the dominant secularized global religion. It uses the legitimacy of the tool of science to acquire power. I believe that Scientism is an achievement of modern civilization. It is probably the largest and most powerful religion that has ever existed on the face of the Earth. However this is not a good thing as it obstructs the valuable tool that is science from doing what it was originally intended to do: discover reality while minimizing inherent human bias so that the findings are as objective as possible.

I refer to Scientism as a religion for the fact that too many research studies, in any field but especially mental health, can be deconstructed like what you did here. This shows that a significant amount of faith and belief is required in order to accept shoddy research as “scientific fact.” Faith and belief is the domain of religion, not science.

Report comment

Thank you Robert Whitaker for yet another generous offering of top shelf investigative journalism. (Where is the Murrow, Polk, or Pulitzer committee?).

The question begs, however: “How evidence based psychiatry has led to a tragic end”. To what end? If any of the several scientific organizations you meticulously cited had penned this analysis, then, perhaps, an actual End would be close at hand (rather than a precursor to the next institutional iteration. At some point, Orwellian terms like “evidence based” will no longer fool, and they’ll just have to say plainly what lies at the root of this gratuitous fundamentalist nonsense: “Take these pills kid or your parents get it in the head”. (Sorry…its laugh or cry)

A paragraph from the essay: “Yet, imagine this thought experiment. If the “evidence-based” assertions were removed from the discussion, what would most people think about giving a three-year-old who “talks excessively” or “who is easily distracted” a 5 mg dose of methylphenidate three times a day, which is a dosage deemed “optimal” in toddlers?”

So many chilling implications here. How could such ‘mildly different’ behaviors from a 3 year old compel powerful drugs? What, exactly, needs to be crushed here? Human spirit? Individuality? Difference itself? What is this compulsion in our societies to standardize everything down to the last nano-thingness? Make no mistake about the macro-implications of Mr. Whitakers essay: this essay says more about our institutions and society-or peon-propped-up psychiatry, than it does any child saddled with a ADD label, and their drugged persons in the never ending project of validating and propagating psychiatric and scientific virtue.

As a 64 year old man who was forced (albeit willingly at 9 years old) to take Ritalin to correct my “abnormal brain”-because the brain was so well understood in 1967, I’m not the least bit hopeful the ADD lever-lie is going away for decades to come. Its an institution now, and that fact alone is a house of cards.

Report comment

I struggled with the title, but the Tragic End was meant to mean, led to a tragic end where medicating three year olds is seen as a good thing to do. Even as the ADHD craze rose for school-age children, there was a sense that medicating preschoolers was a step too far. But now psychiatry has reached the “end point” of recommending it as a practice. And so the diagnosing and prescribing of stimulants to toddlers is rising fast.

Report comment

Thank you Bob for this totally damning article. For over 40 years I’ve practiced as a licensed therapist serving children and families. I’ve never diagnosed a child, teen or adult with ADHD, or referred them for meds. 28 of those years I worked full time in a large public sector mental health system. The question your article begs is- if ADHD isn’t what psychiatry says it is, then what is it? Bob, you know that is the same question I’ve been posing about extreme states for decades. In every instance children( including pre-schoolers) that have seen me who were subjectively experiencing and expressing emotional distress that could have been labeled ADHD and drugged, were clearly causalities of what John Read has proven are adverse childhood experiences.

Since for pre-schoolers that means those adverse experiences occurred almost exclusively in the family home, then the answer to what gets labeled ADHD is a psycho-social impact that extends out to the toxic social matrix that houses all our families and crushes many families into super stressful, traumatic environments for young children.

Both academic and practicing psychiatrists have failed both the scientific rigor and moral test of discovering what is in full view.

Children, teens, adults and seniors all are causualties of our loveless and morally bankrupt society. Because Bob, as old NIMH chief Thomas Insel proclaimed a few years ago that got him excoriated by his fellow psychiatrists- when ANYONE comes in for treatment there will be no medical diagnostic tests done to verify the label given to them- no blood test, no X-ray, no brain scan, no genetic test- no just a pathetic somber search through the pages of the bogus DSM for a label- And this “best practice” done even to toddlers by a failed medical specialty where patients die 25 years earlier that the average.

Report comment

There are cases of infants under one year old being prescribed stimulants for “ADHD.” It is very disturbing that anyone could even CONSIDER such an option! Frankly, I’d rather see them use laudanum – at least they were being honest about their intentions!

Report comment

Ah, Steve. I’m here in Australia wishing that laudanum were an option in today’s world. It would be so much more gentle than the options we are given, like Lyrica or Seroquel – or for those of us in chronic pain = Cymbalta or Amitryptaline.

My great great grandfather was a doctor who created his own patent medicines. While I’m sure there was a lot of snake oil around before regulation – I’m also sure that so many of these “patent medicines” were far less harmful than today’s drugs.

Report comment

I agree – since most of psych drugs’ effects appear to be placebo effects, a little “snake oil” might not do any harm to try out. Worst that happens is nothing, and your body still is allowed to grow and develop.

Report comment

Thank you for your post. You make so many interesting points, from the personal to the systemic. Your schizophrenia journey is inspiring; I have always thought that such a recovery was possible and I enjoy hearing when people have shifted from being beset by symptoms to doing well.

Report comment

Thanks! If you’re interested in learning more about the history of schizophrenia and psychiatry, you may enjoy “How The Brain Lost It’s Mind – Sex, Hysteria and the Riddle of Mental Illness” and “Bleuler, Jung, and the Creation of the Schizophrenias.” I was absolutely dismayed that my education at Ohio State and in the community college system in California (dev psych, etc), excluded any mention of syphilis. When the realities of syphilis are included, the works of Freud and other scions make a lot more sense. The idea that sex could cause the development of neurosyphilis could have driven me hysterical. My takeaway is in alignment with the author, a neurologist at Yale. He posits that neurosyphilis gave birth to psychiatry because it was absolutely reductionist. Now, the world signs on to bio-reductionism with the mind. In my opinion, marketing types are most guilty, but everyone plays a role in this mass delusion. Cheers!

Report comment

Really excellent article. Thanks so much, as always, for your determination to find out the truth and lay it out so meticulously.

Report comment

Of course ADHD is a made up diagnosis that is highly profitable for drug companies. It also lets parents off the hook for not spending quality time with their children. Just drug them and send them on their way.

Notice that some of the protesters in Moscow, who are against Russian invasion in Ukraine, are being packed off to psych hospitals. Psychiatry has always been a political invention that is used to suppress free speech and self expression.

Report comment

Thank you for this much-needed ammunition in the fight to stop psychiatry from poisoning the brains of children and the worldview of those who care for them.

Report comment

Thank you, Robert Whitaker, for pointing out this systemic “mental health” industry abuse of children. But I do agree with Greg Shankland, that the psychiatrists should be charged with criminal negligence, or even criminal intent.

Especially given the fact that every doctor is taught in med school that both the antidepressants and antipsychotics can create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. And many of these ADHD stigmatized children have already ended up misdiagnosed as “bipolar.” At which point the children are forced to take the antipsychotics and/or antidepressants, as well.

Indeed, it appears to be criminal, intentional, systemic, psychiatric abuse of children – and all of psychiatry’s clients. And since creating “mental illnesses” in children – or adults – for profit is the opposite of the psychiatrists’ promise to “first and foremost, do no harm.” This systemic psychiatric iatrogenesis needs to end.

Report comment

This very thorough article is obviously really valuable. I can certainly follow it, but even with my Phi Beta Kappa key, it is difficult for me. Although my health is near collapse now, I will soon be trying to start yet another group to fight psychiatric abuse, with a working title of “Protect Our Children from Psychiatry.” As many know, I spent almost my entire childhood in psychiatric institutions, though I am now a lawyer, and I have a special interest in psychiatry’s abuse of children. I also think that the public would be much more willing to question the psychiatric cult and its destructive practices when children are involved.

The sophisticated critiques of psychiatry in MIA will be very helpful for this, but I think most people will have trouble following them. May I suggest that articles like this include some kind of easy-to-follow summary at the end? I know if this group really happens, we will be asked what our basis is for our refusal to obey the lies of psychiatry, since after all, psychiatrists are “doctors” and “scientists”, not subhuman mental cases like us. Easy to read summaries of great articles like this one would be very helpful. And thank you again, Bob, for writing this.

Report comment

Ted, this is always a challenge. he JAMA article asserted there was an “evidence base” for prescribing stimulants to three-year olds. The purpose of an article like this is to say to those who would believe this, let’s look at your evidence base, and does it justify that conclusion. That means examining such items as “effect sizes” and “number needed to treat.” That is the language of “evidence-based” medicine, and I know it can be off-putting. But here is a simpler summary:

a) One justification given for prescribing stimulants to toddlers is that ADHD is a neurological disorder characterized by genetic and brain development abnormalities. The relevant research actually finds the opposite, which is that the overwhelming majority of those diagnosed with ADHD show no such abnormalities.

b) The second relevant claim is that there are children “with ADHD” and children “without ADHD”, and that experienced clinicians can distinguish between the two. A child either has ADHD or doesn’t have ADHD. The relevant research shows that there is no such line, it’s all a construct. So that’s a second falsehood.

c) The third claim is that the PATS trial showed stimulants to be a safe and effective treatment for toddlers diagnosed with ADHD. That too isn’t true; at least 85% of those so treated–even by the standards of the trial–didn’t receive a short-term benefit in terms of “symptom reduction,” and long-term, what you see is an intervention that turns toddlers into permanent mental patients.

So, it’s a practice, said to be evidence-based, that in facts robs toddlers of their childhood and almost certainly will diminish their lives as adults, should they continue to take psychiatric drugs as they grow up (which two-thirds do.)

That’s the bottom line. And that’s what our society is doing in the name of “evidence-based” medicine.

Report comment

Great article, as usual. The one thing I might have included is the multiple studies on “ADHD” diagnosis and admission to school, showing that a one-year delay in school entry leads to a 30% reduction in “ADHD” diagnoses. This both undermines the idea that “ADHD” is something objectively diagnosable, and also extrapolates to say that if you just leave these poor kids alone, a third of them will most likely “grow out of it” in a given year. Probably even a higher percentage of preschoolers. Which anyone with “common sense” would expect. Though I guess it isn’t as “common” as it used to be!

Report comment

I have always been troubled that they prescribe the same drugs to children, even toddlers and infants that they give to adults. And we do know the damage these drugs to adults. And of course, lest we forget Childrens’ brains are developing. Children are in the most important learning stage of their lives—-learning to be adults. I could say that this is “unconscionable” but that is an understatement. It must be that these psychiatrists and others, even educators, are wishing for a drugged society from birth until death. But all I can say, “Be careful what you wish for…” Thank you.

Report comment

Drugging children makes me want to cry.

Report comment

That’s not scientific!

Report comment

Which part?

Report comment

This is pure insanity…

Report comment

Robert Whitaker, please review Tom Insel’s new book as well as the NYT review of the book (behind a pay wall I refuse to breach).

Report comment

I don’t think we can add much through a review. On the one hand, judging from the NY Times review, he is acknowledging that there have been no advances in treating “mental illness” in the past 40 years, and that the field has been selling us hype for four decades. So there is a sense of acknowledgement that the critics are right. But at the same time, he is maintaining a belief that there are effective drug treatments for mental disorders, and that the field is in fact learning a lot about the biology of mental disorders –it’s just that the knowledge is not getting translated into new treatments. And then he talks about our social failure, without acknowledging that this social failure has all taken place during the 40 years we have had “biological psychiatry.” Maybe we’ll have someone write a blog about this–that is what is really needed, rather than a review of the book.

Report comment

thanks

Report comment

Bob, thank you for yet another excellent article. Thank you for what you do. Nobody does it better.

I’ve thought about this a lot. I’ve drafted Word documents. My first thoughts turned to the validity of DSM diagnoses, the critiques of the science and the conclusions from it. Low hanging fruit.

But those are not the most important points and would result in arguments about minutae that would miss the point. The biggest issue, in my opinion, is philosophical. Thank you for calling this out. Our contemporary science is devoid of it. And psychiatry is entirely unequipped to address it.

Should we work to identify and pharmacologically treat anxiety/depression/tempers/ passivity_irritibility/etc in newborns/infants/toddlers? Is doing so us engaging in preventive medicine, catching diseases early before they fully manifest? Or is it medicalizing life?

Yes or no. Yes if such psychological experiences are understood as biologically-based medical illnesses, no different than catching a virus or tumor. No if they are understood as experiences that are a product of the person’s history and context.

What does it mean to be human? Is it part of life to be sad, mad, afraid, bored, lonely, paranoid, guilty, angry, and so on? Are these experiences that can be understood in the context of a person and their history and environment? Are they part of life, understandable via analysis of what we’ve been through and the meaning we’ve made of it, and part of life’s journey? Or are any deviations from happiness and contentment and behaving in societally ideal ways indicative of medical pathology, by definition?

Or are these various forms of unhappiness/imperfection medical illnesses, pathological deviations from the normal state of being a human which is to have no “symptoms,” to be perfectly and happy and content and always behave according to societal normal, of one’s history and environment?

It all comes down to this. This is the “third rail” psychiatry cannot touch. Happily avoiding the third rail means not ignoring the morality of giving a 3-year-old a psychiatric drug, chalking it up to science and evidence and such. Ditto with giving a presumably fidgety infant. After all, science, prevention of mental illness, benefits of treatment. But this approach has no philosophy of what it means to be human, no understanding of how life can be difficult and make people struggle.

Report comment

Don’t worry, they will soon have a gene therapy to correct those poor distressed toddler’s mood. They can do this in the womb to make sure women give birth to a healthy, well-adjusted, genetically modified toddler.

In “The Matrix,” it was found that humans didn’t thrive if they were given a perfect world, though. They needed regular stressors to ensure their fulfillment.

Report comment

Bob, thank you for yet another excellent article. Thank you for what you do. Nobody does it better.

I’ve thought about this a lot. I’ve drafted Word documents. My first thoughts turned to the validity of DSM diagnoses, the critiques of the science and the conclusions from it. Low hanging fruit.

But those are not the most important points and would result in arguments about minutae that would miss the point. The biggest issue, in my opinion, is philosophical. Thank you for calling this out. Our contemporary science is devoid of it. And psychiatry is entirely unequipped to address it.

Should we work to identify and pharmacologically treat anxiety/depression/tempers/ passivity/irritibility/etc in newborns/infants/toddlers? Is doing so us engaging in preventive medicine, catching diseases early before they fully manifest? Or is it medicalizing human diversity, the ups and downs of life, toxic experiences and environments, and so on?

Yes or no. Yes if such psychological experiences are understood as biologically-based medical illnesses, no different than catching a virus or tumor. No if they are understood as experiences that are a product of a person’s history and context. Yes or no.

What does it mean to be human? Is it part of life to be sad, mad, afraid, bored, lonely, paranoid, guilty, angry, and so on? Are these experiences that can be understood in the context of a person and their history and environment? Are they part of life, understandable via analysis of what we’ve been through and the meaning we’ve made of it, and part of life’s journey? Or are any deviations from happiness and contentment and behaving in societally ideal ways indicative of medical pathology, no different from asthma or diabetes or cancer?

It m comes down to this. It is an issue of philosophy. What is the nature of being a person living in today’s world? Does it matter a lot? Or not at all. THIS is the question.

Report comment

Any way you cut, philosophy it, relativize it, deny it, ignore it, define it or justify it, it is child abuse. And let’s get real- the pills are purchased and dispensed by parents. But they, the pharmacist, the drug store, the prescriber, the wholesaler, the manufacturer and every politician that voted for laws protecting all of the above are complicit- as are the citizens of our society that voted for those politicians who make the laws that allow and make possible the child abuse. The horror show fact is that our society wants everyone, toddlers included to stop expressing anger, fear, sadness or any emotion beyond a proscribed intensity. Because if the emotions you or the toddler feels are expressed in ways that make people too uncomfortable, a DSM diagnosis and some emotion numbing and silencing drugs are going to be required.

Report comment

Ritalin and Adderall are classified as schedule 2 dangerous drugs with high risk of addiction. Cocaine, Meth, OxyContin and Fentanyl are also class 2 schedule drugs.

Report comment

Funnily enough when I was prescribed adderall at age 23 to treat my ‘ADHD’, I expressed concern that I would become addicted to it because I have a family history of addiction. These concerns were dismissed by my psychiatrist. I did become addicted to adderall after about two years. I’ve been sober for 2 and a half years, now. 2 and a half years later, I still can’t feel anything good. Sex doesn’t feel good, eating doesn’t feel good, breathing doesn’t feel good. Still, sobering up was the best decision I’ve ever made.

I think ADHD is a real condition, just not a medical condition. It describes a person who has difficulty navigating this rat maze we’ve developed. As wages drop and rent rises and living becomes more difficult and less rewarding, more and more people will feel as though a stimulant would help them cope. But there’s nothing about having ‘ADHD’ that makes you immune to the grisly long term effects of a stimulant habit, which have been known for many decades.

I live out of the hope that I will some day be able to feel normal again.

Report comment

Well said!

Report comment

Still this all comes down to “criticizing” psychiatry, rather than demanding its abolition. Since the basic premise of “mental illness” upon which psychiatry is based is an invalid construct from the start, focusing on this or that aspect of psychiatry as “in need of change” — rather than addressing the need to eliminate the entire system of fraud and pseudo-science it represents — ensures that these atrocities won’t be going away any time soon.

Report comment