There has long been reason to think that antipsychotics, because of their many adverse effects on physical health, contribute to the early death of the “seriously mentally ill.” In 2006, this worry burst into the headlines with a report by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. It found that in public health settings, people diagnosed with schizophrenia and other “serious” psychiatric disorders were dying, on average, 25 years earlier than normal.

While suicide and accidental deaths account for 35% to 40% of this excess mortality, nearly two-thirds is attributable to somatic diseases: cardiovascular illnesses, diabetes, and respiratory ailments in particular—all of which can be seen as elevated risks due to the adverse effects of psychiatric drugs.

Yet, three years later, Lancet published a study by Finnish investigators that concluded antipsychotics reduce mortality. Since then, this group of investigators has continued to publish papers that draw this same conclusion, and at least two U.S. studies have supported their findings. This research has produced headlines that tout this newly discovered benefit of antipsychotics:

“Antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, SSRIs REDUCE, not worsen, risk of mortality in adults with mental illness.” Tweet from American Psychiatric Association President Jeffrey Lieberman, August 29, 2013

This new claim, in fact, has moved into a front-and-center-stage position in the evidence base that is cited for long-term use of antipsychotics. Other arguments for the long-term use of these drugs have weakened in the past decade, or crumbled altogether, and thus this new finding has come along at a fortuitous time for those promoting this practice.

Psychiatry has long promoted the long-term use of antipsychotics by stating that they reduce the risk of relapse. However, shortly after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its report on early death among the “seriously mentally ill,” Martin Harrow published his study of the long-term outcomes of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, announcing that recovery rates were eight times higher for the off-med patients and that the off-med group was less likely to be suffering psychotic symptoms at each follow-up. Researchers in other countries have since reported similar findings, with recovery rates higher for those off antipsychotics, all of which has led to a questioning of the significance of the relapse studies as “evidence” for the long-term use of these drugs.

The field also has been rocked by research showing antipsychotics cause a shrinkage of brain volumes, and that this shrinkage is associated with a decline in cognitive function and a worsening of negative symptoms (emotional disengagement).

But if this latest claim—that antipsychotics reduce mortality—is based on good science, it would provide a compelling argument for maintaining patients on these drugs. In medicine, a drug that reduces mortality rates for a disease is understood to be an “effective” treatment. That is a bottom-line outcome, and the very outcome that is used to assess the effectiveness of, for example, cancer treatments.

Conversely, if a drug increases mortality rates, then—by this same line of reasoning—it is doing harm. In that case, the goal would be to use the drugs cautiously and seek to limit their long-term use.

What follows is a review of the literature regarding the effects of antipsychotics on mortality rates. After a quick summary of the “mortality gap” between the “seriously mentally ill” and the general population, there is a review of research that supports a conclusion that antipsychotics contribute to early death. Next, there is a review of the studies now being cited as evidence that antipsychotics are protective against early death.

Readers can decide which line of research they find most convincing.

The Mortality Gap

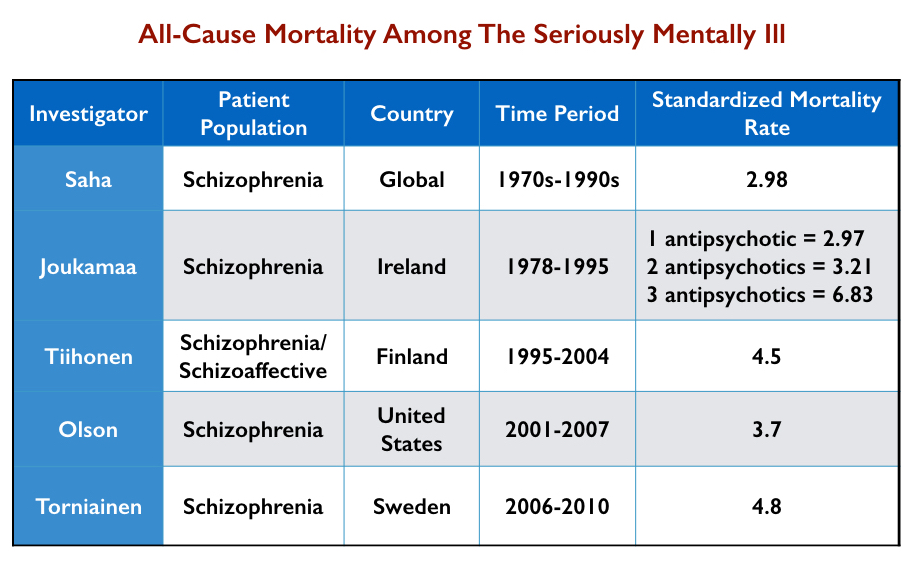

The metrics that researchers commonly use to assess early mortality are “standardized mortality rates.” For example, researchers may compare mortality among people diagnosed with schizophrenia to mortality in the general population over a 10-year period (with both groups matched by age and gender). If there are twice as many deaths in the schizophrenia group compared with the general population, the standardized mortality rate (SMR) is 2.0. If there are three times as many deaths, the SMR is 3.0, and so forth.

The higher the SMR, the greater the “mortality gap” in terms of years lost to a disease or disorder.

In 2006, when the National Health Association of State Mental Health Program Directors published its report, the “mortality gap” was understood to have widened in recent years. Indeed, the standardized mortality rate for the seriously mentally ill, compared with the general population, has worsened over the last 40 years.

- In 2007, Australian researchers conducted a systematic review of published reports of mortality rates of schizophrenia patients in 25 nations. They found that the SMRs for “all-cause mortality” rose from 1.84 in the 1970s to 2.98 in the 1980s to 3.20 in the 1990s.

- In 2017, UK investigators reported that the SMR for bipolar patients had risen steadily from 2000 to 2014, increasing by 0.14 per year, while the SMR for schizophrenia patients had increased gradually from 2000 to 2010 (0.11 per year) and then more rapidly from 2010 to 2014 (0.34 per year.) “The mortality gap between individuals with bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, and the general population, is widening,” they wrote.

These “all-cause” mortality data do not provide evidence, on their own, that antipsychotics are contributing to this mortality gap. However, it is noteworthy that SMR rates have steadily worsened during the antipsychotic era, with this worsening appearing to continue in the era of atypical antipsychotics. That is not what one would expect if antipsychotics protected against early death.

There is one other intriguing finding in the 2007 report by Australian researchers. They found that mortality rates for schizophrenia patients across the three decades were higher in developed countries (SMR 2.79) than in lesser-developed countries (SMR 2.02). This is of interest because a World Health Organization study had found that only a small percentage of schizophrenia patients in developing countries during this period were regularly maintained on antipsychotics, whereas in the U.S. and other developed countries, continual drug maintenance was the standard of care. There is an apparent correlation in these data: The mortality gap is greater in countries that rely more heavily on antipsychotics.

Part I: Evidence that Antipsychotics Lead to Early Death

The Adverse Effects of Antipsychotic Medications

The first-generation antipsychotics—chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and such—were known to cause a wide range of adverse effects. In particular, they regularly caused Parkinsonian symptoms (motor dysfunction), which over the long-term frequently led to tardive dyskinesia (TD). Researchers determined that TD was associated with an increased risk of death (SMR = 1.4).

In addition, the known adverse effects of these drugs included obesity, fatal blood clots, arrhythmia, heatstroke, hormonal abnormalities, seizures, and blood disorders. “They have adverse side effect profiles that can affect every physiologic system,” said George Aranas, a psychiatrist at the Medical University of South Carolina, in 1999.

The second-generation antipsychotics that came to market in the mid-1990s, described as “atypicals,” are also known to cause a wide range of adverse effects. These drugs may be less likely to cause Parkinsonian symptoms and tardive dyskinesia, but more likely to cause obesity, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension which, when clustered together, are described as “metabolic syndrome.”

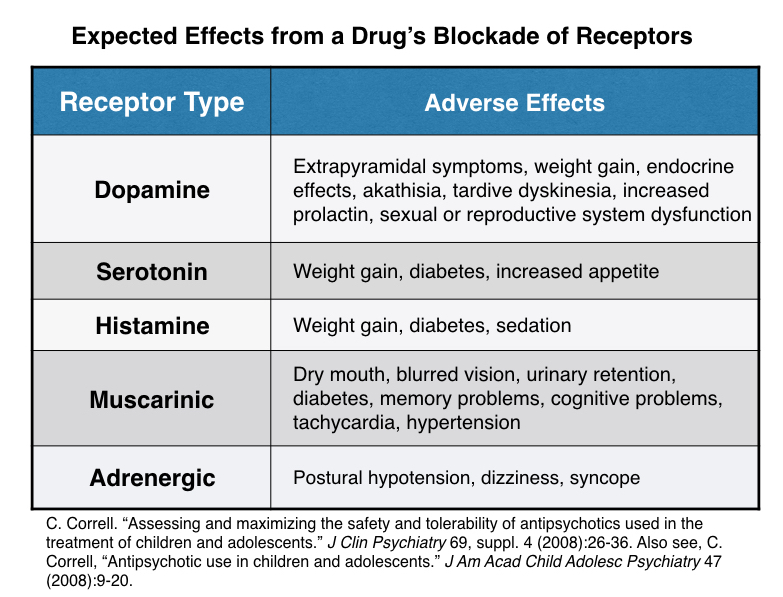

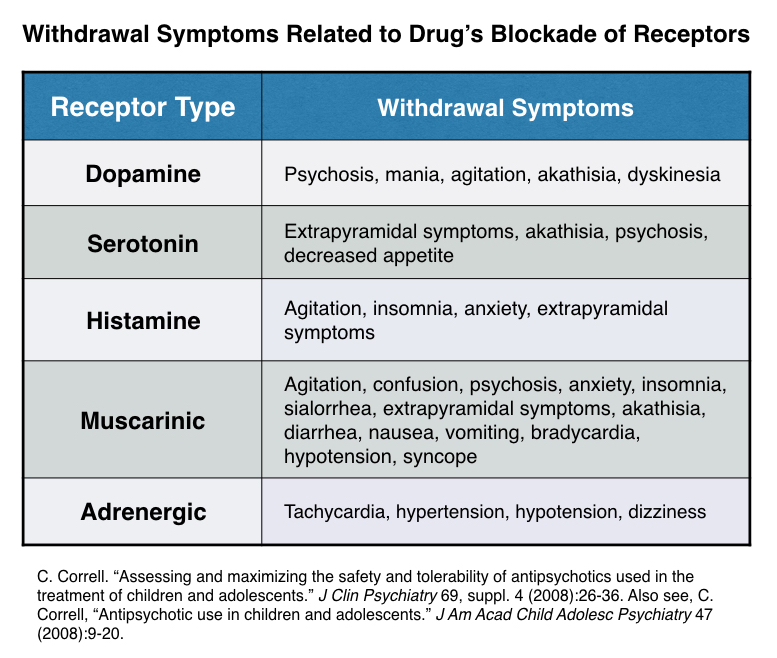

However, it can be a bit misleading to lump antipsychotics together as either first-generation or second-generation drugs, as the adverse-event profiles of individual drugs vary greatly, depending on which neurotransmitter systems they disrupt and their potency. This chart tells of the adverse effects associated with the disruption of different neurotransmitters in the brain.

These drugs, Christopher Correll and others wrote in a 2015 paper published in World Psychiatry, increase the risk for “cardiovascular, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal, haemetological, musculoskeletal and renal diseases.”

Thus, both typical and atypical antipsychotics cause adverse effects that could be expected to increase the risk that their users will die from somatic ailments, and in particular from cardiovascular, respiratory, and endocrine diseases. If so, this increased risk of death should show up in studies that calculate SMR rates for these illnesses among users of these drugs.

There are three types of mortality studies to review:

- The first are studies that utilize large patient databases to assess SMR rates among the seriously mentally ill due to somatic illnesses.

- The second are studies that utilize large patient databases to assess the impact of antipsychotics on mortality rates among patients without a psychiatric diagnosis.

- The third are a handful of studies of smaller cohorts of psychotic patients that assess whether variations in their use of antipsychotics affected their risk of dying.

Excess Death Among the Seriously Mentally Ill Due to Somatic Illnesses

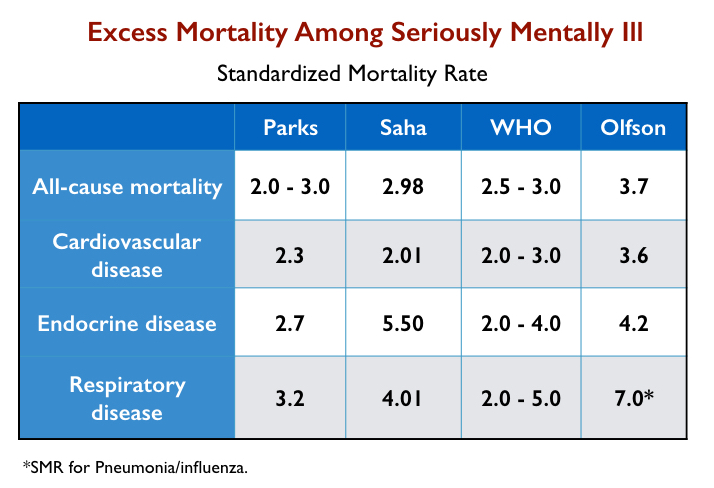

In their studies, researchers have published varying SMR rates for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (or the serious mentally ill) for all-cause mortality and for specific diseases. The chart below details SMR findings from the following:

- The 2006 report by the National Health Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (Parks).

- The 2007 meta-analysis by Australian investigators of mortality among schizophrenia patients in 25 countries (Saha).

- A 2015 summary report by the World Health Organization on “excess mortality” in the severely mentally ill (WHO).

- A 2015 article that assessed mortality rates for 1.13 million Medicaid recipients diagnosed with schizophrenia, ages 20 to 64, from 2001 through 2007 (Olfson).

Two of these studies (Parks and Olfson) charted SMR rates among those with schizophrenia and the seriously mentally ill in the United States. Two others charted global SMR rates for these diagnostic groups. All four found that seriously mentally ill patients, a large percentage of whom are prescribed antipsychotics, die from somatic illnesses at rates two to five times that of the general population.

The excess mortality due to somatic illnesses among the seriously mentally ill is often attributed to the “disease,” or to their unhealthy behaviors, as opposed to the adverse effects of antipsychotics. Yet, even if the seriously mentally ill—quite apart from any treatment effects—often suffer from poor physical health, the adverse effects of antipsychotics could still be expected to contribute to this excess mortality.

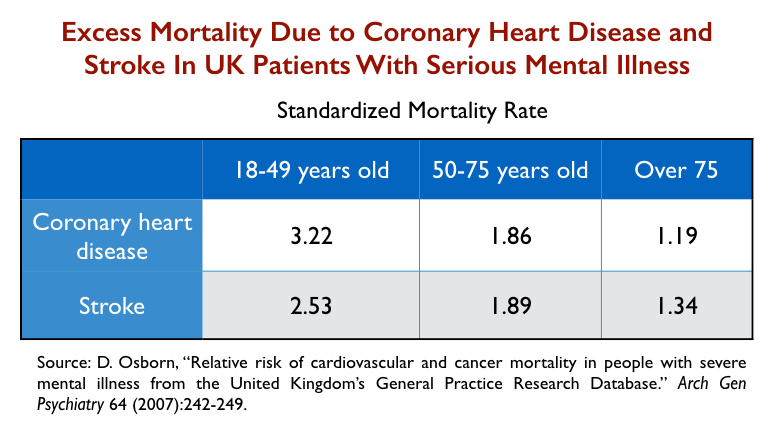

There is one other study that provides insight into excess mortality among the seriously mentally ill due to somatic illnesses.

In a 2007 report, David Osborn and colleagues assessed SMR rates for coronary heart disease and stroke among the seriously mentally ill in the UK, compared with the general population. The excess mortality declined with age, meaning that the excess risk was particularly pronounced for younger patients.

Excess Death Among All Users of Antipsychotics

In the studies cited above, which tell of early death among those diagnosed with schizophrenia and the seriously mentally ill, there was no assessment of antipsychotic usage among these groups. The studies simply calculated SMR rates for a diagnostic group without regard to their treatment.

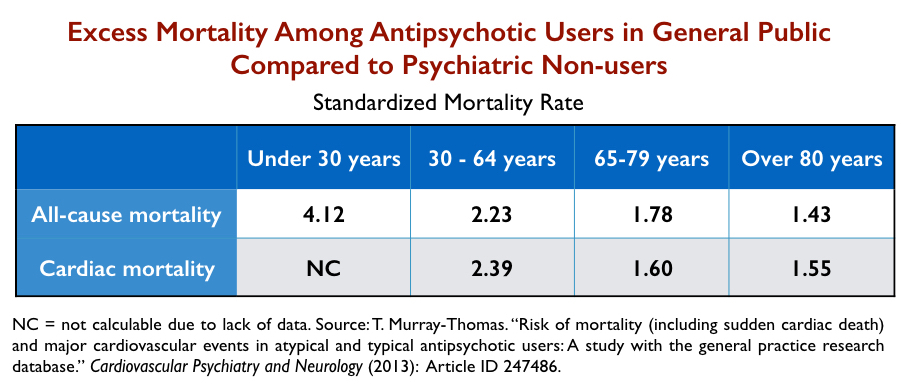

In 2013, UK investigators conducted a large study designed to assess “mortality among antipsychotic users relative to nonusers.” They utilized a database of computerized records of nearly 11 million patients treated in primary care from 1995 to 2010 to identify three cohorts of patients:

- All users of antipsychotics, regardless of whether they had a psychiatric diagnosis (N = 183,392)

- Non-users of antipsychotics from the general population (N = 544,726)

- Non-users of antipsychotics who had a psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression (N =193,920)

First, they determined that people diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who didn’t use antipsychotics still died at a higher rate than non-users in the general population. (SMR for schizophrenia =1.99; SMR for bipolar = 1.40.) However, the SMRs for these unmedicated patients were notably lower than in studies of all patients in these diagnostic categories (e.g. studies that included those who were taking antipsychotics.)

Second, they reported that users of antipsychotics in the general population were almost three times as likely to die as non-users in the general population. The researchers published “fully adjusted” SMRs, which means they sought to equalize all the risk factors in the two groups, other than their usage of antipsychotics.

All-cause mortality: SMR = 2.72

Cardiac mortality: SMR = 1.83

Sudden cardiac death: SMR = 4.03

Third, the investigators compared non-users with a psychiatric diagnosis to users in the general population. This is a comparison between two unequal groups at baseline: Those with a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to die. Yet, it was the users of antipsychotics in the general population that had higher mortality rates.

All-cause mortality: SMR = 1.75

Cardiac mortality: SMR = 1.72

Sudden cardiac death: SMR = 5.76

As part of this third comparison, they also reported the mortality rates for the users in the general population, compared to psychiatric non-users, by age. This revealed that the elevated mortality for antipsychotic users is most pronounced among those under 30 years of age, and declines after that.

The UK study, with its various comparisons, provides evidence that antipsychotics elevate mortality in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients. The risk is so great that users in the general public die at higher rates than non-users with a psychiatric diagnosis.

There are numerous other studies that have assessed the impact of antipsychotics on mortality rates in non-psychiatric patients—the elderly; those with dementia, Parkinson’s, and COPD; general hospital patients, Medicaid recipients, adolescents, and children. With great regularity, researchers report that antipsychotics elevate SMRs for “all-cause” mortality and cardiac diseases.

Here is a summary of the most notable findings:

- According to a 2018 meta-analysis, antipsychotics double the risk of dying among dementia patients.

- In a 2016 study of 15,000 veterans treated for Parkinson’s, those who were treated with antipsychotics were more than twice as likely to die within six months (SMR=2.35).

- A 2009 study of 275,000 Medicaid enrollees in Tennessee found that users of antipsychotics who had no history of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, compared with a matched group of non-users, were twice as likely to die from sudden cardiac death.

- A 2019 study of 190,000 children and youth in Tennessee, ages 5 to 24, determined that all-cause mortality for those treated with antipsychotics was nearly twice that of a matched group who didn’t use antipsychotics (SMR = 1.80).

In a 2018 review of the literature, Australian investigators summed up the bottom line. Antipsychotics raise mortality rates in all patient groups. The “all-cause mortality of patients prescribed antipsychotic drugs is close to two,” they wrote, adding that the “elevated risk of mortality is highest” in the first 180 days of use, and is dose-related. This finding led the researchers to issue this recommendation:

“This is the first meta-analysis to include evidence from general mental health studies showing that antipsychotic drugs precipitate excessive mortality across the spectrum. Prescribing of antipsychotic drugs for dementia or for other mental health care should be avoided and alternative means sought for handling behavioral disorders of such patients.”

Excess Mortality in Cohorts of Psychotic Patients

The studies above relied on large databases of medical records, which could be utilized to calculate SMRs in patients grouped according to diagnosis or antipsychotic use. There have been a handful of studies of small cohorts of psychotic patients that have assessed whether variations in antipsychotic use affected their risk of dying.

In a prospective study of 88 chronic schizophrenia patients in Ireland, average age 62, John Waddington and colleagues reported that 44% died within the next 10 years. Two-thirds died from either cardiovascular or respiratory illness. The Irish researchers concluded that “the greater the number of antipsychotics given concurrently, the shorter was patient survival.”

In 1978, Finnish investigators led by Matti Joukamaa began following a group of 99 schizophrenia patients who were, at that time, all 30 years or older. At entry into the study, 20 of the 99 were not taking antipsychotics, 31 were taking one antipsychotic, 34 were taking two antipsychotics, and 14 were taking three or more.

Over the next 17 years, 39 of the 99 died. The mortality rates for the patients increased with each step up the antipsychotic ladder. The SMRs for these patient groups, compared with mortality rates in the general population (matched for age and gender), were as follows:

No antipsychotics: SMR = 1.29

One antipsychotic: SMR = 2.97

Two antipsychotics: SMR = 3.21

Three or more antipsychotics: SMR = 6.83

Joukamaa wrote:

“The present study demonstrated a graded relationship between the number of neuroleptic drugs prescribed and mortality of those with schizophrenia. This relationship and the excess mortality among people with schizophrenia could not be explained by coexistent somatic diseases or other known risk factors for premature death.”

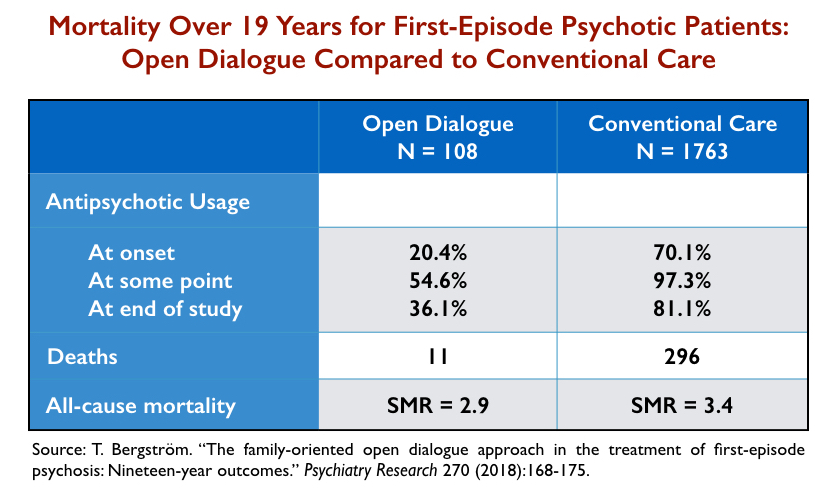

A third cohort study provides a comparison of mortality rates for first-episode psychotic patients treated either with Open Dialogue therapy in Western Lapland or conventional treatment elsewhere in Finland. Open Dialogue limits both the immediate and long-term use of antipsychotics and thus this study provides a comparison between two different paradigms of care.

At the end of 19 years, only 55% of the 113 Open Dialogue group had ever been exposed to antipsychotics and only 36% were on antipsychotics. In contrast, 97% of the 1,763 patients in the comparison group had been exposed to antipsychotics, and 81% were on the drugs at the end of the study period. Eleven of the Open Dialogue cohort died (10%) during the lengthy follow-up, while 296 in the conventionally treated cohort died (17%).

The sample sizes in this comparison were too small for these mortality rates to be statistically significant. However, as can be seen in the chart below, mortality rates were lower in the group with less exposure to antipsychotic drugs.

Suicide in the Antipsychotic Era

Suicide and accidents account for up to 40% of the early-death mortality among the seriously mentally ill (and a higher percentage of all deaths in the first year after initial diagnosis). For the purposes of this review, the first fact to note is this: Suicide rates among the seriously mentally ill rose sharply after the arrival of antipsychotics in asylum medicine in the mid-1950s.

Although it is commonly stated that the lifetime suicide rate for schizophrenia patients today is 10%, with some sources stating that it has long been that way, Irish psychiatrist David Healy, in a review of the literature, came to a somewhat different conclusion. The best evidence shows that it is closer to 4%, which is still four times higher than it was prior to 1955. “The best estimate for the lifetime suicide rate of patients with schizophrenia in the pre-community era is of the order of 1% or less,” he wrote.

A 2002 Australian report by SANE similarly concluded that “the suicide rate has risen markedly since deinstitutionalization began—it is at least four times higher today than in studies from the period 1913-1960.”

A large study of U.S. veterans hospitalized between 1950 and 1975 found that this rise in suicide happened in concert with the introduction of antipsychotics. From 1950 to 1955, the suicide rate for those with “neuropsychiatric” conditions was comparable to the rate for those with general medical conditions. However, in the next two decades, there was “an 8-fold increase in suicide among neuropsychiatric patients compared with general medical patients,” Healy wrote in his 2006 review.

The reasons for this increase in suicide are understood to be multi-factorial (and not just due to the possible direct effects of antipsychotics). One thought is that asylum care was protective against suicide, and that the higher suicide rate today is a consequence of deinstitutionalization, with the seriously mentally ill poorly served by whatever community care is available.

Yet, Healy and others have pointed at antipsychotics as a possible contributing factor. Their use presents three types of suicide-related risks: adverse drug effects that may induce suicidal behavior; drug-withdrawal symptoms that arise when people stop taking an antipsychotic; and, for many, the despair that comes with this paradigm of care.

Drug-Induced Akathisia

It is well known that antipsychotics can induce akathisia, an intense inner agitation associated with an increased risk of suicide and violence. The fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published in 1994, stated that drug-induced akathisia was a common adverse effect of the drugs, which could lead to suicide:

“The subjective distress resulting from akathisia is significant and can lead to noncompliance with neuroleptic treatment. Akathisia may be associated with dysphoria, irritability, aggression, or suicide attempts . . . The reported prevalence of akathisia among individuals receiving neuroleptic medication has varied widely (20%-75%).”

More recently, a German study of 289 first-episode psychotic patients treated with haloperidol or risperidone found that “suicidal ideation was significantly associated with clinician observed akathisia, depressed mood, younger age, and use of propranolol,” with this latter drug prescribed to treat akathisia.

While the first-generation antipsychotics were known to regularly induce akathisia, the second generation, while thought to be less problematic in this regard, still induce akathisia in 15% to 35% of patients.

Withdrawal Risks

Many psychotic patients treated with antipsychotics in the hospital—and this is particularly true for first-episode patients—quit taking their drugs once they are discharged. Others may stay on the drugs for a time and then abruptly stop taking them. Within a couple of years following initial diagnosis, the majority of patients have tried to withdraw from the antipsychotic they have been prescribed.

This pattern of “discontinuation” exposes psychotic patients to the rigors of withdrawal, which is a risk that is not natural to the “disease.” The list of possible withdrawal symptoms is a long one, including a risk of severe psychotic relapse and newly emergent akathisia that may persist for long periods of time.

A Depressing Therapeutic Environment

First-episode psychotic patients enter into a therapeutic environment that, for many, is profoundly depressing and isolating. People are regularly told they have chronic illnesses and that they may have to forever take a drug—an antipsychotic—that they find robs them of their ability to feel and emotionally interact with the world. Yet, those who refuse to take an antipsychotic will likely find themselves in conflict with family and societal demands. They are damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

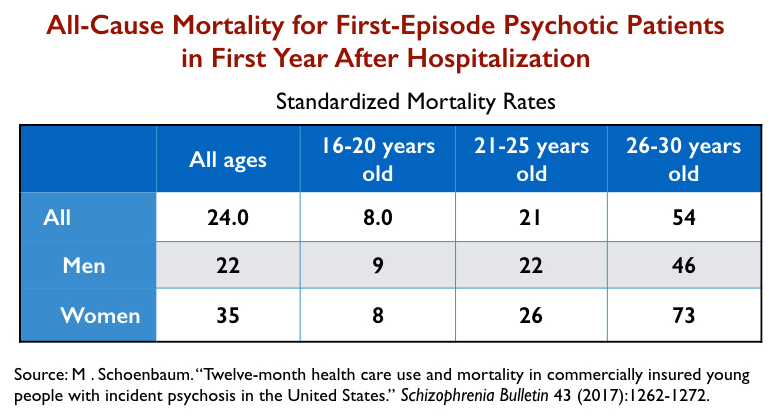

These are the three suicide-related risks posed by an antipsychotic-based paradigm of care. And studies of first-episode patients regularly report that their risk of mortality and dying by suicide soars in the 12 months following a first hospitalization.

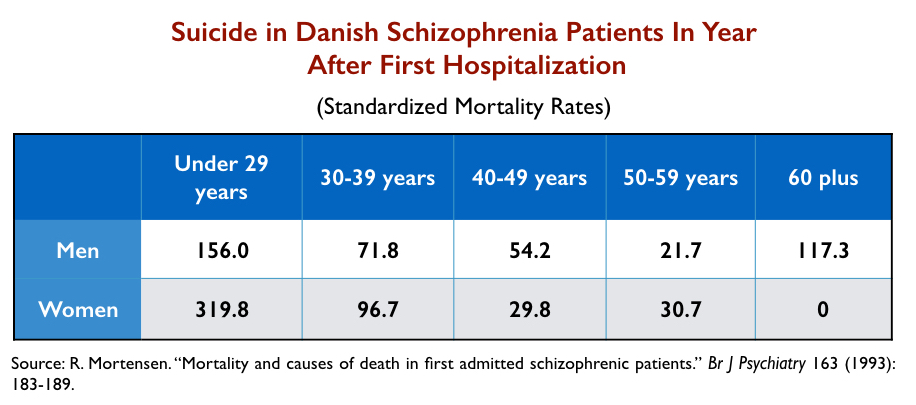

For instance, in a Danish study of 9,156 schizophrenia patients hospitalized for a first episode of psychosis between 1970 and 1987, the suicide rate among those under 30 years old was more than 200 times higher than among the general public.

Similarly, a large U.S. study of 5,488 commercially insured first-episode patients found that their all-cause mortality during the first year was 24 times the rate for the general population, with nearly 2% dying during that period. More than 60% of this first-episode group never filled a prescription for an antipsychotic following their discharge from the hospital, and thus the majority experienced the risks that come with abrupt withdrawal from an antipsychotic.

It is easy to see that the impact of antipsychotics on suicide rates for first-episode psychosis patients could be interpreted in two different ways.

One common method is this: Researchers may compare suicide rates among first-episode patients who stay on their antipsychotics to those who stop taking them, and if the suicide rate is higher in the latter group, the researchers may conclude that drugs are protective against suicide.

A second method is to look at the suicide rate for the entire cohort of first-episode patients during the year following discharge. This approach provides information about the risk of suicide within a drug-based paradigm of care, and the research reviewed here reveals two relevant facts:

- Suicide rates for those diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are much higher today than in the pre-antipsychotic era.

- Suicide rates soar to extreme heights for young adults who suffer a first episode of psychosis and enter into this world of antipsychotic-centered treatment.

Summing Up the Evidence That Antipsychotics Contribute to Early Death

As can be seen in the research summarized to this point, there are compelling reasons to conclude that these drugs contribute to early death. To wit:

- Both first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics cause adverse effects that are known to increase the risk of dying from cardiac, respiratory, and endocrine diseases.

- Psychiatric users of antipsychotics die at high rates from these somatic illnesses.

- Non-psychiatric patients who use these drugs also die at elevated rates from these illnesses.

- In both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients, the use of antipsychotics doubles the risk of death in comparison to matched cohorts of patients who do not take the medications.

- Studies of smaller cohorts of schizophrenia patients have found that antipsychotic use is associated with elevated rates of death, with this risk rising with higher doses and polypharmacy.

- Suicide rates for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are dramatically higher in the antipsychotic era than in the pre-antipsychotic era, and this risk soars during the first year after initial treatment with an antipsychotic in the hospital.

With that evidence in mind, we can now examine the research that is being cited today as evidence that these drugs reduce mortality and lengthen lives.

Part II: The Evidence That Antipsychotics Reduce Mortality

The research most often cited as evidence that antipsychotics reduce mortality has come from a group of Finnish researchers led by Jari Tiihonen. Since 2006, he and his collaborators have published at least seven studies of various cohorts of patients with conclusions to that effect.

While this research has been funded by non-pharmaceutical sources, Tiihonen has ties to numerous pharmaceutical companies and manufacturers of antipsychotics. In a 2015 paper, he disclosed that he had “served as a consultant, advisor, or speaker for Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-La Roche, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, and Pfizer.”

The Finnish research relies on extracting information from three databases. The first is a national registry of hospitalized patients in Finland dating back to 1965, which provides a diagnosis given to all patients. The second is a national record of all outpatient drug prescriptions since January 1, 1996, with each prescription linked to a specific individual by an ID number. The third is a national death registry.

These three databases enable Tiihonen and colleagues to identify all Finnish residents who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia or some other psychotic condition since 1965, track the antipsychotic prescriptions they purchased since 1996 while living in the community, and assess whether they are still alive, and if not, the date and listed cause of death.

In their studies, the outpatient prescriptions serve as a proxy for medication use. If a discharged patient fills a prescription for an antipsychotic during a month (or period during which a drug must be refilled), then that person is deemed to be “on medication” for that time. If a discharged patient fails to fill a prescription for any 30-day period, then the person is deemed to be off medication for that time.

With this information, Tiihonen’s group is able to design retrospective studies that calculate mortality risks in a select group of patients related to their medication status. Are patients more likely to die during months they are off medication, or during the months they have filled a prescription (and thus are deemed on medication)? How do mortality rates vary according to patients’ cumulative use of antipsychotics over longer periods of time?

There are several methodological issues with this research that need to be understood in order to assess its merits.

Medication Usage

The Finnish research uses “outpatient prescriptions” as a proxy for antipsychotic usage. However, since this database didn’t exist before 1996, there is no assessment of antipsychotic usage prior to that date. For example, a person diagnosed in 1965 could have taken antipsychotics for up to 30 years and suffered their many adverse health effects, and yet, if that person stopped taking the drugs prior to 1996, he or she would be counted as a “non-user” of antipsychotics in these studies. The usage of antipsychotics during hospitalizations is also not recorded, and given that the majority of deaths occur in such settings, this is a second black hole in this research.

Survivorship Bias

In one of the studies examined below, Tiihonen followed people diagnosed with schizophrenia for up to 11 years, starting in 1996. However, the average age of this cohort at entry into this study was 51 years. Given this average age, this is a study of mortality in a group that has “survived” treatment for a number of years, and thus is not representative of the larger population of patients so diagnosed and treated prior to 1996.

For instance, imagine that there were 100 people born in Finland in 1945 who were subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia, and that 50 in that group of 100 had died prior to 1996. The 50 still living are a subgroup who apparently tolerated the treatment fairly well. In the Finnish studies that include individuals diagnosed prior to 1996, none of that early mortality is accounted for. Instead, the researchers are studying mortality rates in a subgroup of “survivors,” which could be expected to bias the results.

In their more recent publications, the Finnish investigators state they made adjustments to account for this survivorship bias, although they don’t describe what information they used to do so.

Person-Year Mortality Rates

In their papers, Tiihonen and colleagues often report mortality rates based on “person-years” of the collective time that patients spent either on or off medication. In non-randomized studies, this is a method known to often cause distorted results, particularly if one group can be expected to rack up many more “person-years” than the other.

For example, imagine an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia who for the first five years of a study is on antipsychotic medication and alive at the end of that time. That is five “person-years” of survival on the antipsychotic. Now that same person goes off the drug and dies one year later. That is one death in “one person-year” off medication. Thus, that person provides five “person-years” of survival on the drug (to the total “person-years” equation) and adds one death per year to the off-antipsychotics group. Now imagine a second person who is on antipsychotics for six years, and dies at the end of that sixth year on antipsychotics. When you tally up the person-year mortality rates for these two people, you end up with this:

1 death per 11 “person-years” on drug

1 death per 1 “person-year” off drug

Thus, in this person-years calculation, the mortality rate is 11 times higher for the off-drug group, even though, during the study, one person died off medication and one person died while taking an antipsychotic.

The use of person-years is particularly inappropriate for assessing mortality rates in first-episode psychosis patients. Nearly all psychotic patients are treated with antipsychotics in the hospital, and thus the person-years meter for the on-drug group starts running the instant the patients are discharged from the hospital. In contrast, the person-years meter for the off-drug group starts running at a much slower pace, as it only begins when people stop taking the drugs. The fact that the prevailing paradigm of care emphasizes continual use of the drugs will also help the on-drug meter keep running at a much faster rate than the off-drug meter.

A mortality rate is calculated by dividing the number of deaths into the number of person-years, and thus the larger the number of person-years, the lower the mortality rate.

In addition, first-episode patients who are discharged from the hospital and stop taking their medication are then thrust into a withdrawal state, which is known to put them at high risk for suicide and accidents. This will likely inflate the number of deaths in the off-med group, and thus produces a mortality rate calculation for the off-med group that consists of an elevated number of deaths due to drug-withdrawal hazards and a low number of person-years due to prescribing practices. It’s a method bound to produce a mortality rate that is unfavorable to first-episode patients who stop taking their antipsychotic medication during the first year.

Reporting Outcomes as “Relative Risks”

The Finnish investigators regularly report “relative risk” of death as their primary outcome (instead of absolute number of deaths). For example, they may report that patients with no use of antipsychotics over some period of time died at 1.5 times the rate of those who continually took such drugs. However, for “relative risks” to be meaningful, it is necessary to compare outcomes in like populations (age, severity of illness, and so forth), and given that these are not randomized studies, there may be notable differences between the off-med and on-med groups.

In their published articles, Tiihonen and his colleagues do state that they made any number of statistical adjustments to account for inequalities in the groups that are being compared, but they don’t provide information about what the baseline inequalities are. As such, readers are left with a “trust us” result. There is no way to know if the “relative risk” outcomes are comparing mortality in “like groups,” and often Tiihonen and colleagues don’t even provide the actual number of deaths in each group. Readers are simply informed that one group was more likely to die than the other.

Mortality Within a Drug-Centered Paradigm of Care

The biggest problem with the database studies—a fatal flaw, one could argue—is that all of these data come from patients treated within a drug-centered paradigm of care.

To truly assess the impact of antipsychotics on mortality rates, it would require comparing death rates for first-episode psychotic patients treated under differing paradigms of care: one that emphasized antipsychotic usage right from the outset, and one that avoided initial use of the drug and minimized their long-term use. The Open Dialogue study above provides the first hint of such a comparison.

However, except in the Lapland area, Finnish psychiatrists regularly prescribe antipsychotics to their psychotic patients. Ninety-seven percent of all Finnish patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis are exposed to antipsychotics, and the usual practice is to maintain patients so diagnosed on the drugs. This paradigm of care presents antipsychotic-related risks for both those who stay on the drugs long-term and those who come off.

Those who stay on may suffer from the many adverse effects of antipsychotics, as was detailed in the first half of this report. But those who stop taking antipsychotics continue to suffer a multitude of drug-related risks:

- They may continue to suffer from cardiovascular and other health problems that arose from their exposure to the drugs. Obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic abnormalities don’t disappear upon cessation of the drug.

- They likely will suffer withdrawal symptoms—physical, emotional, and psychiatric—that increase the risk of suicide. Emergent akathisia may persist for months, and even indefinitely.

- They may experience the social reproach—and lack of social support—that regularly come with stopping antipsychotics for anyone who has a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Yet, with the methodology employed in the Finnish research (and similar database research conducted by a handful of others), all of these mortality risks, which arise within a drug-centered paradigm of care, are chalked up as risks due to being “off medication.” The entire exercise rests on a make-believe foundation, which is that the minute a person doesn’t fill a prescription, the risks due to prior exposure to the drugs magically vanish.

With those caveats in mind, here are summaries of their most influential reports.

General Population Studies

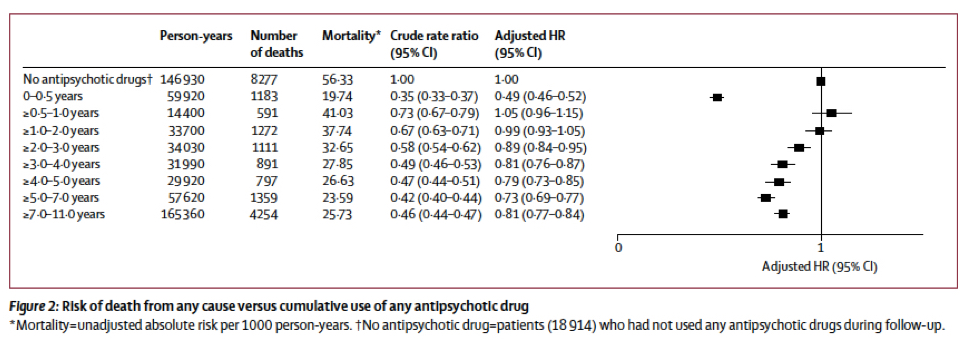

This study, more than any other, led to the now-common claim that antipsychotics reduce mortality. The researchers identified 66,881 people who were admitted to a hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia from 1973 to 2004 and assessed their medication use—starting in 1996 based on the outpatient prescription register—for up to 11 years. They concluded that “long-term exposure to any antipsychotic treatment was associated with lower mortality than no drug use.”

Their findings were summed up in this graphic, which shows that those who took antipsychotics for two years or more were less likely to die than those who didn’t fill any prescriptions during the study.

The methodological issues discussed earlier are on display here. There is no information about medication usage prior to 1996 or in the hospital, even though the average age of the patients was 51. There is no information about medication usage in the hospital, even though 64% of all deaths occurred in the hospital. With a population this old (on average), there is an obvious survivorship bias.

Person-years are used to calculate mortality rates. Outcomes are presented as relative risks. There is very little data about the number of patients in each of the usage groups, and nothing about how the groups might have differed. And so on.

All that readers can really know is that the investigators sorted through the information in their three databases, performed any number of statistical adjustments, and voila, out popped results that told of how patients who used drugs for most of the 11 years were less likely to die than those who didn’t use the drugs at all.

Now, given that antipsychotics are regularly prescribed to schizophrenia patients, the first question that arises is this: What is the makeup of this large group of patients who didn’t use any antipsychotics during the 11-year follow-up and yet died at high rates? If you read the study closely, you’ll find that there were 18,914 individuals in that “no-use” group, 8,277 of whom died in the 11 years.

Tiihonen and colleagues speculate that the non-user cohort was composed of two types: the 20% of schizophrenia patients said to do well without antipsychotics, and chronic patients who relapse frequently and have repeated hospital admissions but won’t take drugs after discharge.

However, that speculation doesn’t add up to a large population of “non-users” who could be expected to die at elevated rates. The “20%” who do well off antipsychotics are a group with lower disability rates than the norm for schizophrenia patients, and studies regularly find lower mortality rates among those not on disability. As for chronic patients with frequent hospitalizations, they would be exposed to antipsychotics in the hospital, and so they shouldn’t be classified as “non-users.”

There is a clue to be found in the “adjustments” to the “crude rate ratio” that produce the bottom-line “adjusted hazard ratios.” The adjustments reveal that the non-users, at the start of the study, were at higher risk of dying than the other groups, which is almost certainly due to this cohort being a much older population than the others.

The authors of this study, in the interest of transparency, should have provided readers with that information about age differences. But it is missing.

There is another, more egregious, aspect to this study. In their discussion, Tiihonen wrote that our findings “indicate that long-term use is associated with lower mortality than is no use or short-term use.”

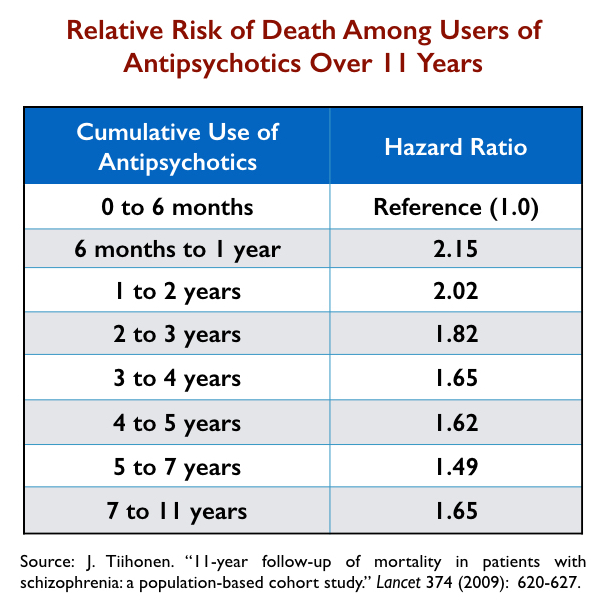

Their own data show this isn’t true. The lowest mortality rate in this study was actually among those who had zero to six months of exposure to antipsychotics over an 11-year period, i.e., a group that hardly used the drugs at all. That is evident in their own graphic of outcomes (above).

Indeed, if they had decided to use this low-exposure group—0 to 6 months of usage—as the reference group, rather than the “no-usage” cohort, they would have reported that those with 7 to 11 years of cumulative exposure to antipsychotics had a 65% greater mortality rate.

The table below details the relative risk of dying for all groups with six months or more exposure to antipsychotics, compared to the group that used the drugs less than six months.

With the data presented in this way, there is no clear-cut conclusion to be drawn about the impact of antipsychotics on mortality. Death rates are indeed high for those with only six months to two years of exposure. Why might that be? At the same time, why would exposure of 0 to six months—hardly any exposure over an 11-year period—produce the lowest mortality rate?

Those are the sort of questions raised by this study. And given that the standard of care is to keep schizophrenia patients on antipsychotics, here is the paradigm-challenging conclusion that Tiihonen and his colleagues could have written: “We found that the lowest mortality was in schizophrenia patients who, over an 11-year period, used antipsychotics for a very short time—six months or less.”

This study, in many ways, is an update to the 2009 study. But rather than report mortality rates based on cumulative antipsychotic usage over a longer period, it focuses on mortality related to on-off use of antipsychotics.

Tiihonen and colleagues looked at antipsychotic usage from 1996 through 2015 for all Finnish adults diagnosed with schizophrenia and treated in a hospital between 1972 and 2014 (N = 62,250). They reported that their “all-cause” risk of dying more than doubled during off-antipsychotic periods and that cardiovascular mortality also increased when they weren’t filling their antipsychotic prescriptions.

The same methodological problems are present in this study as in the 2009 one. There is the lack of knowledge about antipsychotic usage prior to 1996 and in the hospital, person-years are used to calculate mortality rates, and relative risk outcomes are reported. The researchers state they made adjustments to account for “survivorship” bias, but they don’t explain how they did so.

However, if you closely read the report, you can find the numbers that the researchers used to present their “relative risk” findings. And then you can do a second round of calculations that fully reveals the statistical sleight-of-hand present in this study.

At entry into the study, the average age of the patients was 46. During a median follow-up of 14.1 years, 13,899 of the 62,250 patients died (22%). There were 8,264 who died while “on” antipsychotics and 5,635 while “off” antipsychotics.

Thus, 59% of the deaths occurred in people who were filling their prescriptions. Yet, the researchers concluded that the “all-cause” risk of dying for patients while on medication was 0.48—less than half—that of the risk when patients were off medication.

So where did this 0.48 figure come from?

If you do the math, you find that it was made possible by the use of “person-years” to calculate mortality rates for each group.

On medication: 577,417 person-years divided by 8,264 deaths = 1 death for every 70 person-years.

Off medication: 187,773 person-years divided by 5,635 deaths = 1 death for every 33 person-years.

The reader has to do his or her own quick division of the raw mortality data to see this ratio. It shows how with “person-year” calculations, the researchers turned data that showed more deaths while people were taking an antipsychotic into a “relative risk” finding that told of antipsychotics protecting against early death.

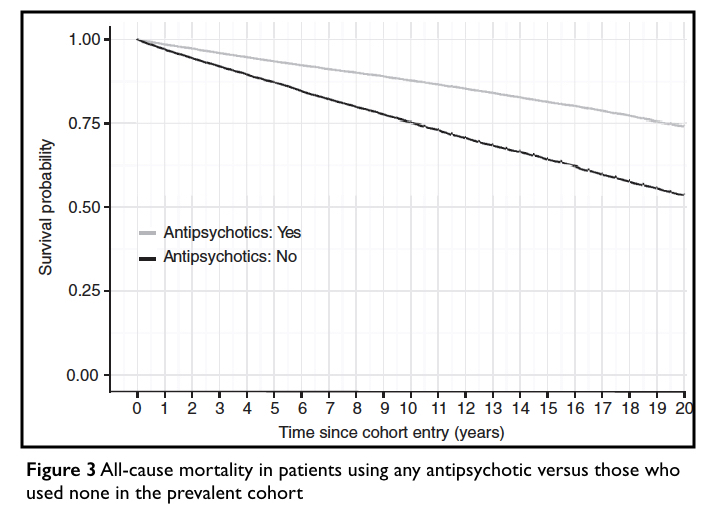

Then comes their “bottom-line” graphic, which spins the person-year calculations into a visual that powerfully tells of how antipsychotics help schizophrenia patients live longer lives. The chart shows that antipsychotics improve survival rates at a steady pace, year after year.

The graphic states that it depicts the survival rate of those who used antipsychotics in this study versus those who “used none.” As such, readers could be expected to assume that there was a group in this study who never used antipsychotics for the 20 years, and that 46% of these “non-users” died.

Nothing like that happened in the study.

Here is how Tiihonen’s group created this graphic. If the mortality rate during off-antipsychotic periods was 1 in every 33 person-years, then, theoretically, if there were 100 patients at baseline who weren’t using antipsychotics, there would be 97 from this group alive at the end of one year. If you keep applying that 1-in-33 annual mortality rate for the next 19 years, only 54 of the 100 would be alive at the end of 20 years (and 46 would be dead).

At the same time, if the mortality rate during on-antipsychotic periods was one in every 70 person-years, then if there were 100 patients at baseline who were using antipsychotics, there would be 98.5 alive at the end of one year, and with that rate of annual mortality, 74 of the 100 would be alive at the end of 20 years (and 26 would be dead).

The researchers don’t describe any of these calculations. And, of course, there is no group in the study identified as having been on antipsychotics continuously for 20 years. Nor is there any group identified as never having taken antipsychotics during that period.

The chart is best described as a statistical mirage. But it is a powerful one. You see the graphic and you see that antipsychotics steadily improved survival rates for schizophrenia patients over two decades of use. It’s a chart that, to the eye and mind, immediately tells of drug treatment that “works” over the long term.

The researchers also reported that antipsychotics reduced “cardiovascular” mortality, with a relative risk of 0.62 compared to “non-use” periods. If this study is to be believed, the very drugs that in the general population double the risk of cardiovascular mortality are protective against that risk in people diagnosed with schizophrenia.

First Episode Study

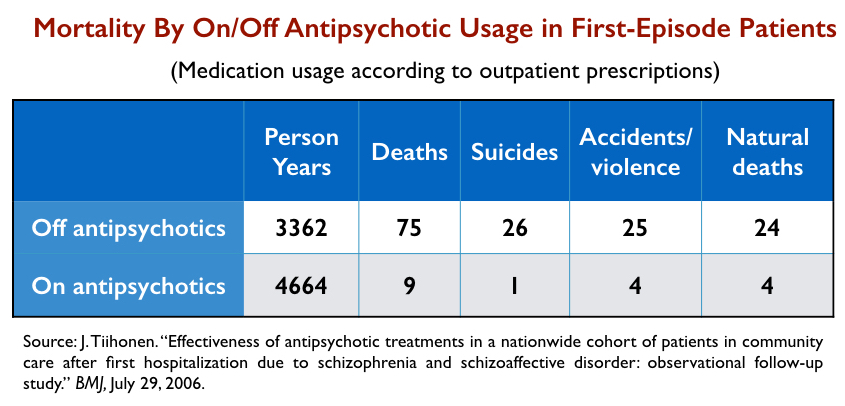

This was a study of 2,230 adults hospitalized for a first episode of schizophrenia from 1995 through 2001, with their prescription use—according to the investigators—charted from the moment of their initial discharge.

The first problem with this study is a subtle one. While Tiihonen’s group states that it has charted the filling of prescriptions for all of the patients from the moment they were discharged, that can’t be true for those diagnosed in 1995. As they state in their other studies, that outpatient prescription database dated back to 1996, and thus medication usage in 1995—the first year for those diagnosed in 1995—would be unknown. But that detail, that the prescription database only went back to 1996, isn’t revealed in this publication.

In this paper, Tiihonen and colleagues, rather than focus on relative risks of dying, reported the actual number of deaths during periods when people were in “off-medication status” and during periods when they were filling their prescriptions.

The average age of the first-episode patients was 30.7 years, and they were followed for an average of 3.6 years. As a cohort, these patients were “off medication” 42% of the time. Seventy-five patients died while in “off-medication” status, versus nine while in “on-medication” status.

As noted earlier, suicide rates for people diagnosed with schizophrenia increased with the introduction of antipsychotics. One possible cause for that is that initial use of antipsychotics in the hospital sets up a period of high risk for those who don’t like the medications and stop taking them after discharge. In this study, 36% of the discharged patients didn’t fill a prescription within the first 30 days, and as can be seen, death by suicide and accident was very high for those who entered this drug-withdrawal risk pool.

The mystery data in this study, of course, are those showing that there were six times as many deaths due to natural causes—cardiovascular mortality and such—during “off-antipsychotic” periods than in “on-antipsychotic” periods. Why would that be? This is a fairly young cohort, and so why would patients who stopped taking antipsychotics die so frequently from diseases that are known to be elevated by use of the drugs?

This is a mystery worth investigating, but it would appear to be a finding that tells of how risks from antipsychotic usage, in this on-medication/off-medication binary design, get transferred to the “off-medication” column in one way or another.

Although Tiihonen didn’t calculate the standardized mortality rate in this first-episode study, a subsequent Finnish report on the five-year outcomes of first-episode patients, which included this cohort, calculated an SMR of 4.5. Thus, the rate of death for first-episode patients treated within this antipsychotic-centered paradigm of care was quite high, even though the study attributed it to patients being off the drugs.

A Failed Paradigm of Care

There have been a small number of other studies that utilized prescription databases to report on mortality hazards related to antipsychotic use, and their findings mostly echo those cited above. They tell of lower all-cause mortality associated with regular antipsychotic use, and yet, at the same time, if they report on SMR rates for the entire cohort, they tell of high mortality for the entire cohort.

In other words, antipsychotics are hailed as lifesavers, even as the paradigm of care is failing.

One of these studies assessed outpatient prescriptions from 2006 to 2010 in a population of 21,492 Swedish patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis. The researchers reported the following SMR rates:

No exposure in five years: SMR=6.3

Low exposure: SMR = 4.1

Moderate exposure: 4.0

High exposure: 5.7

Total cohort: 4.8

This SMR of 4.8, like the 4.5 SMR in the first-episode Finnish patients, is notably higher than the mortality rates reported by Saha and colleagues in their 2007 report. They had warned in that publication that mortality rates would likely continue to rise in the era of second-generation antipsychotics because of their adverse metabolic effects and, at least in the case of these two studies, that is the case.

The two U.S. studies that weighed in on the impact of antipsychotics on mortality rates don’t add much new to the studies conducted in Finland and Sweden.

In a study of 2,132 Medicaid beneficiaries with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, those who used antipsychotics more than 90% of the time had a lower mortality rate than those who used the drugs less than 10% of the time. A primary reason for that difference was that suicide in the low-usage group was six times more common than in the high-usage group. There is no information about how many suicides may have occurred during a period of withdrawal from the drugs.

The second U.S. study, by Arif Khan, led to headlines announcing that “Psychotropics Lower, Don’t Raise, Mortality in Psych Patients.” It illustrates how person-year data can be used to tell a false story.

Khan looked at the trial data for all antipsychotics approved by the FDA between 1990 and 2011, and reported that 9 of 3,419 volunteers randomized to placebo died (1 in 379), compared with 115 of 26,648 randomized to an antipsychotic (1 in 231).

Although a higher percentage of those on antipsychotics died, the patients randomized to placebo were a group abruptly withdrawn from antipsychotics, and in these six-week trials they regularly dropped out before the end of six weeks, which means they contributed very little time to the “person-years” total for the placebo group. Furthermore, even if a placebo patient stayed through to the end of a six-week trial, the maximum “person-years” that a single patient could account for was 6/52 of a year. In total, the 3,419 placebo patients only rang up a total of 313 person-years, or little more than a month per patient.

In contrast, those randomized to an antipsychotic who stayed in the study to the end of six weeks were then entered into extension trials, and thus the “antipsychotic” group now chalked up many more person-years. In total, the 26,648 patients in the antipsychotic category racked up 9,618 person-years, or roughly four months per individual.

Thanks to that person-year differential, the death rate for placebo became one per 34 person-years, compared with 1 per 83 person-years for the medicated group, and voila, you have a calculation that produces headlines that in clinical trials antipsychotics were proven to reduce mortality.

Such is the database research that tells of how antipsychotics reduce mortality. The research is beset by methodological flaws, invisible “statistical” adjustments to the raw data, opaque reporting of findings, conclusions that are not consistent with the data, use of “person-year” data to produce misleading findings and, in the case of the Finnish 20-year study, the publication of a graphic that, to put it charitably, was certain to create a false impression.

And yet, even in these reports, when the investigators calculated SMRs for the entire cohort, they tell of mortality rates that have remained high, or have even climbed, since the 1990s.

Psychiatry’s Latest Delusion

The history of psychiatry is replete with claims about the efficacy of treatments that didn’t stand the test of time. Today, there are more questions than ever about the merits of antipsychotics.

A number of longer-term studies have found higher recovery rates for those off medication. Add in research findings that antipsychotics shrink brain volumes, with this shrinkage associated with cognitive decline and a worsening of negative symptoms, and psychiatry is confronted with an “evidence-based” crisis.

The “antipsychotics lengthen lives” research gave the field a new claim to hang onto and to promote. A treatment for a disease that increases survival, and does so to the extent pictured in the 20-year graphic, can lay claim to being effective. During a time of doubt, that is a conclusion that provides a sigh of relief—and comfort—for the field.

But as can be seen in this review, that belief arises from research that is flawed in so many ways. There is evidence, time and again, of a process that was designed to justify the long-term use of antipsychotics, rather than honestly assess their impact on mortality. Think of the graphic that told of better survival rates for those who used antipsychotics over a 20-year period compared with those who used none, and you can now see, quite clearly, the “science” that is helping to create this new belief.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

I no longer pay attention to studies, since they are laced with lies.

If “relapse” prevention means simply cutting out a function by cutting out overall function with chemicals, it is not a solution, nor is that good science.

And I’m still not sure how a long life benefits a person if the “disease” renders them a subject of discrimination in legal and regular medical care.

I do not HAVE to have my diabetes or cancer treated if I don’t want to. Even if so doing “shortens” my life.

Report comment

Studies, depending on the qualities and focus of the study are also laced with truths. Is the knowledge created changing so fast, that to find and realize a particular platform to rest our weary fingers (as extensions of thinking) creating answers? Seems to me that one would need to understand the nature of research, which to generate theory or to create tests against the null hypothesis is difficult. When I would ask Dr. Deming at a conference on continuous improvement, “Had he worked with a mental hospital?” he took a moment and then replied to the audience of over 400 attendees in his wonderful insightful way to teaching. He replied “You either mark them or – once a day as to how they are they are feeling”, that is improvement. And then as I sat down I realized he was right and yet the amount of variation which I didn’t quite understand at that time as it relates to systems and layers of an organization, such as a public and private hospitals I had experienced, is an incredible entity to manage with improvements. Understanding the potential for improvement for the customer, he would later refer me to a woman in Nashville who at that time worked with HCA and Vanderbilt, later to transfer to the MD Anderson Clinic.

Report comment

Oops – the idea is to mark + or – in the observation from the outside of the patient, or what level of the system is being analyzed. Then by totaling up the daily reports, one realizes a particular pattern or range of highs and lows . There is a norm, within the stats of being inside the upper control limit and lower in terms of reading the data with the deviance from the norm (understand all being language of Statistical Analysis). One does not tamper with the system, which having experienced the altered state and labelled that required my own research and learning, there seems to be a certain way the mind establishes a better integration of its clock. The circadian rhythm is important. And then there seems to be some sort of clock or tempo of the operation on the floor or different areas of a treating facility, a doctor’s office. But how can we share and teach/learn about life so that we can create the revenues and enjoy seeing improvements from our efforts? Is there a way to realize some collaborative efforts and teams?

Report comment

Tiihonen has a long track record of promoting the new drugs over years and decades in Finland. Latest is of course promotion of long lasting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), for which the pharmacies have a new patent for. This work wasn’t mentioned in this article, but it’s there, at least in the Finnish media. Some examples are here. They’re in Finnish, but maybe you can make sense of them with Google translate.

I’ll give some quick translations:

“A Finnish professor would change the the treatment of schizophrenia: Injection medicine could lower mortality

According to the results, injections were related to 20-30 % smaller risk of getting to a hospital treatment.

In addition the injection drugs lowered mortality of schizophrenia patients by 30%

..

– Almost all of the National treatment guidelines say that there are certain special instances, where you should consider using LAI.

– In my opinion the recommendation should be backwards, so that in only special conditions you should consider using an oral formulation.

”

https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10027843

“If Tiihonen had his say, the national guidelines should be something else.

– There are some special cases, where you should consider using oral [instead of LAI]

LAIs are expensive, but the price should be considered against cost of staying in hospital.”

https://www.mediuutiset.fi/uutiset/pitkavaikutteiset-injektiolaakkeet-vahensivat-skitsofreniapotilaiden-kuolleisuutta-hengissa-pysyminen-on-seikka-johon-kannattaisi-kiinnittaa-huomiota/e47286e9-49e7-3eac-89a4-8838fc1f07bc

“I was expecting only 30 % difference. I was surprised to see a 60% difference. It’s very rare to see this big a difference in medicine.

He can think of only a single group of patients where the oral form is preferable over LAI.

“It’s the patient group considering pregnancy.”

https://www.mediuutiset.fi/uutiset/42-prosenttia-skitsofreniaan-sairastuneista-ei-hae-laakkeitaan-apteekista/163e8e8d-940a-316e-9e16-ccdc2523e4bb

Report comment

Also one more note. Many of these Tiihonen registry studies are not just nationally funded, but funded by the pharmaceutic industry. At least the ones promoting LAIs.

Report comment

Another argument from Tiihonen, around 5:00:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MkrsTmcCpq0

Is there a safe place to stop antipsychotic medication? According to Tiihonen studies, there’s no safe point of stopping antipsychotic medication.

“It seems to me that during the first eight years of the illness, it is not safe to say it would be safe to stop the antipsychotic medication”

Then he goes on to LIA injections.

The to clozapine. I’ve been updating this message while watching the video. It’s a very good English review of his views on the treatment.

Results: “I would say it is the lack of antipsychotic treatment that is associated with the associated mortiality .. associated LAI most with reduced mortality .. no safe point in 8 years to stop the antipsychotic medication”

Report comment

What kind of kills me is that he has these two parallel arguments based on his statistical studies.

1. LAIs should be the first line treatment for psychosis/schizophrenia. (Except perhaps for pregnant women.)

2. There’s no safe window to stop antipsychotics, at least in an eight year timeframe.

=> Once you get psychosis, it’s lifetime LAI for you.

Also the comment that nurses get reward when they act according to guidelines.

Report comment

Thank you, Robert, for pointing out how statistics are being manipulated to provide an untrue story about the antipsychotics/neuroleptics. And I will once again point out that the antipsychotics can actually create psychosis and hallucinations (positive symptoms of “schizophrenia”), via anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

And the antipsychotics/neuroleptics can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

But since both these antipsychotic/neuroleptic induced toxidrome/syndrome are missing from the DSM, they are always misdiagnosed as one, or more, of the “invalid” DSM disorders.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

And as to morbidity and all the DSM “mental illnesses,” it’s a shameful story – given that “8 million people die each year due to mental illness.”

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mortality-and-mental-disorders.shtml

Report comment

Thank you so much for this article. It would be interesting to know who and by what measure people are labeled with schizophrenia and other “serious mental illnesses.” So often, a diagnosis of mental illness is made because of someone’s perceived social ineptitude, which is so often bound up with a lower socioeconomic status. I have read articles that state that there is a much higher incidence of “mental illness” among the poor. Greater poverty=greater mortality. So, there may be factors other than “mental illness” that account for the increase in all-cause mortality among the “seriously mentally ill,” even if they never took medication. But as you point out, it is highly unlikely to find anyone with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who has never been exposed to antipsychotics.

Report comment

Mr. Whitaker, Many thanks & kudos for this essay. It’s comprehensive and digestible form is helpful to me as I continue to research and write.

It’s also personally familiar and articulates the health disaster, body & soul, that was my experience embedded in the industry.

Thx again for this valuable presentation.

Report comment

As a health psychologist, currently doing some continuing education work for the American Diabetes Association, I have always been stunned by psychiatrist’s response to the adverse side effects of their medications. With anti-psychotics, its generally a shrug, as the patient gains weight and progresses into Type II diabetes, or a suggestion that we refer the patient onto another specialist (endocrinology or weight loss clinic) to manage the side effects of the psychiatric prescription. On one hand the psychiatrists love to wrap themselves in the white coat, and declare themselves to be the ‘real doctor’ and at the same time often refuse to manage the whole health of their patients. Doug Tynan Ph.D.

Report comment

I’ve seen kids put on a diet and told they need to exercise more as a response to “antipsychotic” weight gain. Of course, they almost never told the kids there was any relationship with the drugs. I saw one girl’s diabetes disappear within a week or two of discontinuing Seroquel. Crickets from the psychiatrists, of course. I saw one kind graduate from a year-plus long eating disorder program, only to be put on Adderall for “ADHD”. Strangely enough, she stopped eating again. If my CASA volunteer hadn’t intervened, no one would have noticed that the “treatment” for “ADHD” was eliminating her appetite, and would have said her “eating disorder” is “coming out of remission.”

Not much real medicine being practiced by psychiatrists, at least for the kids in the foster care system.

Report comment

Remember when these people said the brain damage was caused by schizophrenia when it was really caused by the “antipsychotic” drugs?

They are doing the exact same thing when they claim “behaviors” are responsible for the high death rates. These drugs cause the unhealthy “behaviors”. It’s harder to work out or cook healthy meals when you’re sedated and demotivated by a drug. It’s harder to be at a healthy weight when you’re taking a drug that makes you want to eat all day.

Studies also find that these drugs increase recreational drug consumption. When smoking a cigarette reduces your antipsychotic side effects you’re going to smoke more.

When they blame “behaviors” for the high death rates they are missing the fact that the “antipsychotic” drugs are the cause of the behaviors. Though maybe they know they are lying.

Report comment

Thanks so much for this article! I’ve been needing something to refer people to who have heard the claims about antipsychotics prolonging lives: now there is something to point them towards.

Report comment

Yes thank you Robert, it is an incredible amount of work.

I am glad it is of real use to you Ron, although I don’t know why so many people still wait for something truthful to come out of psychiatry…. the record of psychiatry, who have made up stories and illnesses and stood by harmful chemicals, and are constantly exposed for their lies? The paradigm was all wrong, anything that follows will be wrong.

There will NEVER be some good things that come from psychiatry, unless they leave their cult.

Report comment

Robert, What Might An Alternative To “Antipsychotics” Be?

From Dr Terry Lynchs Book “SelfHood”

Below:-

“Paranoid Schizophrenia” Recovery through Practical Psychotherapy Explained

“…I referred briefly to Stephen’s story in the chapter on self-generated security. Prior to attending me in his late thirties, Stephen had been diagnosed five years previously as having paranoid schizophrenia.

The level of loss of the components of selfhood, including the ability to make oneself feel safe, is at the extreme end of the scale in people diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia.

He attended me to explore possible avenues of recovery. I could see how Stephen was diagnosed as having paranoid schizophrenia.

He saw threat and danger everywhere, when objectively there was none. Stephen’s level of selfhood was at rock bottom, and this was a fundamental underlying reason for his problems. His paranoia was entirely understandable as seen from his perspective, given that one of his main experiences was that he constantly felt unsafe, unprotected and unable to generate any personal security for himself. This was borne out in his second session with me.

As I mentioned briefly in the section on self-generated security, ten minutes into the session, Stephen looked terrified, and I asked him why. He replied ‘I’m not sure I can get out of this place alive’.

There were only the two of us in my office, and nobody in the waiting room. Objectively, there was no threat to Stephen, but he genuinely felt terrified for his life. He described the raw terror he felt almost constantly. I focused on enabling Stephen to progressively raise his level of selfhood. In particular, I worked with him on self-protection and self-generated security, because his lack of these dominated his life, the reason for his fear-filled thinking. I reassured him many times that in general he was much safer than he thought he was. We explored the various experiences of terror and paranoia in detail.

Stephen gradually comprehended that he was indeed much safer within these situations than he had thought. I explained to him that his terror-filled, paranoid thoughts were an outward projection of his inner fear and self-doubt. In public places, he would often have thoughts such as ‘they’re talking about me. I can tell by the way they are laughing that they are laughing at me’. Now, he realized that what he was feeling was more accurately expressed as ‘I feel extremely unsafe, insecure and unprotected right now. I feel terrified, and I’m scared that there could be threats to me here in this crowded place’.

This change in his understanding brought about a considerable shift. Previously, his thinking was preoccupied by the supposed threat that could lie around every corner. Now he was bringing his attention back to himself and what he was actually experiencing. Stephen was now aware of his own terror and inability to make himself feel safe, whereas previously he was not aware of this and instead was entirely focused on the dangers that lay waiting relentlessly for him everywhere. As Stephen was now truly aware of the role he played in his paranoid thinking, we had something substantial to work on. I used every possible opportunity to discuss self-protection and self-generated security with him.

We explored his experiences of paranoia in great detail as they occurred. Our work became firmly grounded on what had actually happened within himself and his personal space in a given situation, rather than focusing on his projections into, and his assumptions about, others and the outside world. People experiencing paranoia also experience their thinking speeding up, reflecting their terror.

Thoughts keep coming, in an ever-more-frantic cascading sequence. The person creates an entire scenario in their minds based on their initial first thoughts. The initial thought may be somewhat based on reality.

For example, a person across the bar happens to look in their direction. The person runs with this, creating a complicated sequence of events in their minds, a fantasy created under the influence of immense terror and great lack of inner safety. In a matter of minutes, sometimes seconds, they become convinced that there is a sinister plot to harm them in some way.

I used these experiences to get Stephen thinking about the accuracy of his interpretations of these episodes. I explained the futility and the dangers of attempting to read people’s minds, a habit that generally results in erroneous conclusions. He began to experiment with these ideas in areas where it really mattered, in the real world. In public places, Stephen would remember our conversations, notice how he was feeling, and whether or not he was attempting to read the minds of others.

For example, when in a bar and a paranoid thought sequence was beginning to gather pace, he was able to stop for a minute, bring his attention back to himself. He could now connect with what was going on for him, look around him, and reassure himself that at this moment, he was not in any danger. In contrast, like a rabbit caught in headlights, Stephen would previously have become increasingly transfixed by an unfolding scenario outside of himself, that he was actually creating through outward projection of his feeling unsafe.

I had encouraged Stephen to see things as they were, to resist the temptation to read into people’s actions and gestures and create his own fictional version of events. His previous pattern of projection had being going on constantly for him, but at an unaware level. He did not realize that he was doing this himself. For example, if a person looked at him and then looked left, he often concluded that this meant he was in trouble. If they turned their face to the right, it meant he would probably be okay, for now at least. Stephen believed that he was just tuning in to what was really out there in the world, but he was in fact creating this scenario himself. I suggested to Stephen that he needed to separate out the other person’s action from the meaning that he (and not the other person) was placing on this action.

I explained that he was relinquishing his power over himself to other people, most of whom neither wanted this power nor were aware that they were being dragged into this situation.

Stephen grasped these ideas and applied them in real-life situations, and in time he was able to extricate himself from his previous pattern of terror-based paranoid thinking.

We explored methods of raising his level of self-protection and self-generated security. These included repeatedly reminding himself that he lived within his personal space and boundary, that this was his space, that he was safe within this space, and that there was much he could do in any given situation to make himself safe.

When feeling unsafe, he would appraise the situation, see things and people as they were and be aware that any meaning he attached to them was entirely his creation and had little or nothing to do with other people or the situation. He reassured himself repeatedly every day that he was safe, that he could make himself safe and protect himself in any situation. When he experienced an episode of extreme fear or paranoia, he practised what we had done together many times in my office.

He separated what was really there from the story he had created, and then reassured himself several times that what he feared would happen had not actually come to pass.

This practise had the desired effect. His level of self-protection and self-generated security began to increase, slowly at first, then gathering pace. Stephen made considerable progress in raising his level of selfhood, of which, for him, self-protection and self-generated security were key factors.

Because he was doing well, his psychiatrist agreed to reduce his medication slightly, and I subsequently continued the process of gradually reducing Stephen’s medication.

Stephen has been off all schizophrenia medication for over three years. He lives a full life, goes where he likes, thrives in social situations, and has a level of selfhood higher that at any previous time in his life…”

Report comment

“HIGH ANXIETY”

The reason a lot of people find it difficult to withdraw from “antipsychotics” is because of “Antipsychotic” Withdrawal symptoms of overwhelming “High Anxiety”.

When I suffered from .my own “Withdrawal High Anxiety” I was eventually able to to see that if I didn’t engage with the Anxiety at the time; it eventually ran out of steam; and I was able to intuitively deal with whatever the problem was.

Report comment

Thank you so much for your words of wisdom. In addition to currently withdrawing from antipsychotics, I am also taking Klonopin. I notice that when I miss a dose, I sometimes experience withdrawal anxiety. I think coming off Klonopin may be more difficult that coming off Risperdal. Time will tell.

Report comment

Thanks Caroline,

You’ll get there in the end!

Report comment

“Antipsychotics” Cause Suicide and “Mental Illness”

According (I believe) to Dr David Healy “antipsychotics” are 20 times more likely (than not) to cause suicide in “Schizophrenia”

I attempted suicide several times on “Antipsychotics” 1980 to 1984. I never attempted suicide before taking “antipsychotics” 1960 to 1980 or after successfully stopping “Antipsychotics” 1984 to 2020.

I recovered as a result of successfully stopping “antipsychotics” in 1984, and have remained well since.

Report comment