Dear Mad in America,

In 2015, following the death of Freddie Gray, I posted a piece here on systemic racism and the hypocrisy of white supremacy including who has the power to define our words and actions. It was called “Baltimore is Burning.” In the comments section, I recall receiving pushback (some of it since moderated out) on whether or not the post “belonged here,” because it focused more on systemic racism than psychiatric oppression. Some felt it was out of place. A distraction.

In 2016, I co-authored a piece with Iden Campbell and Earl Miller called, “A Racist Movement Cannot Move.” It was one of only two posts for which I’ve had to ask that the comments section be turned off. (Incidentally, the other was, “Dear Man: Sexism, Misogyny, & Our Movement,” posted just the year before.) The comments had simply gotten too ugly and out of hand. They were coming faster than they could be moderated out.

It is now June of 2020, and so today, I come to you with this question: How much have we grown?

George Floyd & Our Community

George Floyd was murdered by the police in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25. As I sit here nearly two weeks later, I can find no mention of that on this site. At least at the time of this writing, neither is there much recent mention of the impact systemic racism and endless violence against black and brown bodies can have on one’s emotional well being as a non-white person. How many black people’s distress has been rooted primarily in the envelopment within so much relentless white supremacy, only to then be given a severe psychiatric diagnosis and told it’s all in their head? If I search on George Floyd’s name, the closest result is a 2018 comment that mentions Pink Floyd. I fear we haven’t grown much… or at least not nearly enough.

On May 28, I sent out a statement on behalf of my workplace, the Western Mass Recovery Learning Community, naming not only George Floyd, but also Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Rana Zoe Mungin. The last person named—Rana—did not die so directly at the hands of any other human. She died at the age of 30 years old of COVID-19, as so many black people are dying because she was ignored and discounted when seeking help. I could have just as easily also named the many black and brown people who’ve died during “wellness checks” or similar because they’d been pegged as “mentally ill.”

I think of Dontre Hamilton, the man who died in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 2014, also at the hands of the police, because he was sleeping outside near a Starbucks. Dontre—whose story is featured in “The Blood Is at the Doorstep”—experienced compounded oppressions because he was both black and diagnosed. For as much as so many of us have suffered at the hands of psychiatry, it’s critical to remember that non-white people are statistically more likely to be subjected to even harsher levels of diagnosis, dehumanization, coercion, and force within the mental health system than the rest of us. In fact, psychiatry is often used as a tool to reinforce the subjugation of black and brown people. Talila Lewis—among others—did an excellent job of beginning to paint the picture of racialized psychiatry at the Drug Policy Alliance’s Anti-coercion conference in 2019, sharing about Drapetomania and more.

Psychiatric oppression is largely unseen in this world. As I noted in another 2016 piece, “Dear Self-Proclaimed Progressive, Liberals, and Humanitarians: You’ve Really Messed This One Up,” far too many people fighting against systemic oppression get it wrong when it comes to us. They fight for our incarceration without even understanding that they’ve accidentally stepped to the other side of the line. This is important. I am thankful Mad in America exists for precisely this reason.

Yet, we lose our way when we think our liberation is not bound up in one another’s.

The Intertwinement Of Our Liberation

We limit our own strength when we do not reach across the bounds. This happens in multiple ways. First, as aforementioned, we fail to see how one form of oppression can compound another; how readily one can be used to reinforce the other. This is essential learning necessary to fully unpack what is happening, and develop the tools to undo it.

We limit our own strength when we do not reach across the bounds. This happens in multiple ways. First, as aforementioned, we fail to see how one form of oppression can compound another; how readily one can be used to reinforce the other. This is essential learning necessary to fully unpack what is happening, and develop the tools to undo it.

Second, we fail to practice what we are attempting to teach. If we intend to ask (or demand) of others that they effectively ally with (or become accomplices to) us, recognize their privilege as non-diagnosed people, and put some skin in the game to free us from violence, then we must be willing to do the same. Different forms of systemic oppression are not the same, and should not be compared. Yet, they all feature similar components including failure of those not directly in harm’s way to see what’s actually going on. There is no pride or benefit in being guilty of the same phenomena of which we accuse others.

Third, we become complicit in rendering invisible all those who experience both racism and psychiatric oppression and make our spaces inhospitable to them. In turn, we immeasurably shrink our own capacity to grow. I appreciate the many non-white people who have ventured into these MIA lands. Their numbers are growing. But I hear from many more (including some who have dropped in for a time) how unwelcoming it can feel.

Finally, we defeat ourselves by missing opportunities for collaboration and partnership across the lines of many movements. People fighting for the release of those being held in psychiatric facilities during these COVID times are sometimes fighting alongside those calling for the release of people from jails and prisons, too. Many from both groups are also joining with #BlackLivesMatter and other anti-police brutality protests.

Along the way to revolution (at least that’s where I hope we’re headed), we must continue to ask ourselves the tough questions. For example, if we know that black and brown people are disproportionately impacted by  psychiatry, then why are there so few black and brown voices here? And why do so many—even those who claim to know the sometimes disastrous effects of psychiatry and psychiatric oppression—still sometimes feel they are in any position to tell black people how to think, feel, or protest against an epidemic of racism? I’m struck by the similarities between current times and when I wrote “Baltimore is Burning,” particularly in our broader world where thousands of white people across the nation continue to attempt to criticize violence erupting in protest rather than focusing in on the many years of violence that led us to this point. (I write more about the protests and this phenomenon in a statement HERE.)

psychiatry, then why are there so few black and brown voices here? And why do so many—even those who claim to know the sometimes disastrous effects of psychiatry and psychiatric oppression—still sometimes feel they are in any position to tell black people how to think, feel, or protest against an epidemic of racism? I’m struck by the similarities between current times and when I wrote “Baltimore is Burning,” particularly in our broader world where thousands of white people across the nation continue to attempt to criticize violence erupting in protest rather than focusing in on the many years of violence that led us to this point. (I write more about the protests and this phenomenon in a statement HERE.)

We are stronger when we take the time to see. But truly seeing requires actually listening to those who’ve been there, wherever “there” may be. And once we’ve taken time to listen—with humility and without layering on our own beliefs about that which we do not know first hand—we can best begin to fight together. If all people from marginalized groups took the time to understand one another’s needs and fight, our numbers would grow so large that perhaps we really could change the world.

George Floyd died on May 25. Much like the rest of us, he was not a saint, and his murder was not more important or worthy of being named than Breonna Taylor’s, or the ever-growing list of other black people who’ve been killed by the police. But the nonchalance with which he was murdered while onlookers filmed and called out that he was dying… while he called out that he was dying… made even more blatant what so many have tried hard not to see.

Dear Mad in America community, let us now see. Dear everyone in every community… Please… let us see. Because once we can see, we enable ourselves to act.

Sera, I’m ✝️ I’m 41. I am destined to be alone. I already know.

Many whiteness men say they believe something but they do not do it.

HISTORY USA white men going to Church Sunday but then hurting peoples. OBVIOUSLY history shows hurt peoples very bad.

It is one thing to get the attitude in life roles like work and family. It is much more to get at Church the religion I am.

Sera, THIS IS MY POINT. I too am not accepted at Church though over years I keep going. Much worse to me then discriminate at work. Much worse with me than my family being hurting me. This is very hurtful pain.

The religion I choose to be is my life.

Report comment

Hi Pat,

I do want to keep racism centered in the comments section here, but I am sorry that you have been hurt and also experienced discrimination, especially within your spiritual community. Feeling ostracized and marginalized can be so painful.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

Thank you Sara for being the first at MIA to write about the historic rebellion and uprisings (worldwide) against the death of George Floyd and its’ direct connection to systemic racism.

Sara you have always led the way at MIA in writing on the difficult and necessary topics that often make people uncomfortable while living with much greater privilege in a wealthy class based capitalist society. Especially, since there would be no U.S. imperialist empire, and such enormous wealth, without the oppressive legacy of slavery, and the on-going exploitation of those sectors of society on the bottom rungs of the ladder (especially people of color) both here in the U.S. and in the Third World countries dominated by the U.S.

And I am so glad you did NOT mention the words “riot” or “looting” since they only serve to demean, denigrate, and distract from the truly historic nature of these uprisings. The police were “rioting,” and “looting” takes place on a daily basis in this country by the one percent who have a foot on all our necks in one form or another, including with their Disease/Drug Based Medical Model that is at the route of all psychiatric oppression.

And yes, just as with Covid 19, people of color are disproportionately harmed by today’s so-called “mental health” paradigm of “treatment.”

Systemic racism is intimately connected to the entire history of the U. S. capitalist/imperialist system,and we ALL must find ways in a post Covid 19 world to politically target a profit based capitalist system in ALL our struggles against all forms of oppression. In fact, this has now become a “moral imperative” for those who “know better,’ or should I say, “know more.” I will soon write a blog titled “Psychiatry and Capitalism in a Post Covid 19 World” where i delve deeply into this profoundly important “moral imperative.”

Sara, I was so glad to see you mention the word “revolution” in your blog as a direction we need to seek in our political struggles in the future. But once again, the enormous ELEPHANT (not mentioned) in the room, the fact that ALL of this oppression we are talking about, not only takes place in a CAPITALIST system, but is both given sustenance and powerfully generated by capitalism. And systemic racism, and all other forms of human oppression, cannot end unless humanity ultimately moves beyond a capitalist system.

Now back to the issue of ALL people engaging with Black people, and other people of color, about the way forward out of this systemic insanity. We could plainly see in these recent uprisings MANY different political viewpoints coming from ALL sectors of society and ALL sectors within the Black community. This includes Black politicians, mayors, police chiefs, spiritual leaders, political commentators, and others with various credentials who were sometimes seeking ways to limit the scope, intensity. and political targets for this historic uprising.

In the 60’s, we use to call these type of political interventionists (of all colors and political persuasions) as “firemen” or “fire extinguishers.” They are genuinely afraid of these rebellions going “too far” with too much revolutionary content. These are the same people who choose to focus on “looting,” “property destruction,” and “law breaking” to denigrate the political significance of the righteous rebellion taking place against systemic oppression. These are some of the same people afraid of the terms “dismantling” and “defunding” who now just want to see a few so-called cosmetic reforms to policing and other institutions within our society. All of which will do nothing of consequence to end racist oppression.

Of course, I (and others) should always listen extremely carefully to the political perspectives of all minority people’s, including those who are representing the current power structure and/or status quo. We must always engage in respectful struggle (being very mindful of the long legacy of historical racism in this society) when we have different ideas or views regarding making radical change in society.

But white privilege, and any other class or sexual identity privileges we were born into, should never lead us to hold back from any, and all, opportunities to make radical change in the coming period – the world demands it!

Nor should we engage in any kind of patronizing behavior towards minority people’s (which, in itself, is a form of racism), where we hold back our political perspectives for fear of challenging or “offending.” someone of a different race or ethnic background.

All of these struggles involving systemic racism, climate destruction, women’s liberation, sexual identity, psychiatric oppression, classism etc. must increasing find ways to increasingly come together with a singularity of purpose, with clear targets, and common strategic and tactical goals. This WILL NOT happen without very deep and intense struggle WITHIN, and AMONG, ALL the people fighting those at the top rungs of society. Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win!

Richard

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Richard. There are a number of things I would change about ‘Baltimore is Burning’ and other things I’ve written related to systemic racism and police brutality. That includes not using ‘rioting’ and ‘looting,’ and I believe you were one of the people that brought that to my attention five years ago, so thank you for that.

And yes, I did not mention the role of capitalism and economic justice. My main point here was to draw attention to the silence on the topic at all, and while I certainly could have worked that in… well, I didn’t. But I do not disagree that economic justice and the systems that perpetuate it are central to the problem, and need to be central to the conversation about what to do about it.

As far as the second half of your comment goes… I do not disagree with all of it exactly. However, there is a ton of nuance and tension wrapped up in what you are saying. It strikes me as absolutely essential that we make space to elevate, listen to, and follow the lead of those who’ve been most marginalized. That simply can’t happen when well-meaning allies are constantly telling those most directly impacted by systemic oppression what to do, even if they really, really feel they know better. It can’t happen when those who’ve had the privilege to study concepts and language in school (and similar) attempt to overrun and speak over those who’ve had to actually live and learn to survive that which the others have primarily only studied. It also can’t mean just following along without any critical thought, or deferring to any and everyone whether or not they’ve internalized oppression, learned to act in the image of oppressors for survival’s sake, or simply not been supported to unpack all the crap they’ve been fed along the way. Somewhere in there, there’s a way to at least try and hold both of those points, however messily and imperfectly.

And yes, there’s also the matter of compounded oppressions, or even – as you noted – the central role of money and capitalism in all forms of oppression. I watched a film recently (The Uncomfortable Truth) in which one of the central people (a black man) speaks to how black people and poor white people should have been great allies. There is indeed much as play here that serves to keep so many of us “under.”

So, yes… being born with privilege (white, male, etc.) shouldn’t totally silence people… And, no… sometimes knowing how much privilege we hold *should* lead us to take a step back, even if not permanently… Because otherwise we continue to monopolize the space that is there. When I facilitate trainings – actually when I and/or any of my co-workers facilitate trainings – we include in our meeting agreements the need to sometimes take a step back or count to ten before speaking if you are someone who knows that you often speak first. This is because so many others need a moment to gather their thoughts in order to step forward, and will sometimes remain silent if all that space keeps being filled. This may be because of how society has trained/socialized them to defer to others, how they’ve been slapped back when they have tried to speak up in the past, for lack of trust in the room, because they haven’t had access to the education that supports others to use all the ‘right’ words and speak in ways identified by society as ‘articulate,’ or even just because their way of thinking and pulling ideas together takes a bit more time. Regardless, it’s not about those of us with privilege silencing ourselves forever, or following along without any critical thought at all… But it is about us recognizing how much damn space we’ve taken up at times, about how many others have never even been afforded the space to stumble around a bit as they grow into leaders, and about how sometimes shutting up is actually an important act of revolution at times.

What you’ve said is complex and important, and I don’t know that I’ve responded to it all, but this is what I’ve got for the moment.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

Sara Thanks for your response. I may have more to say in the very near future. But I thought I would post a link to a very powerful post that is circulating on the internet.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLDmB0ve62s

Here is a black women (Kimberly Rice Jones) “speaking truth to power” where she actually DOES use the words “rioters” and “looters,” but she provides a powerful historical and political context. She also references the the Tulsa and Rosewood massacres of several hundred Black people that has largely been hidden in the history books. I believe that Robert Whitaker has written in the past about this topic.

Richard

Report comment

Thanks, Richard! I’m struggling to keep up with work at the moment, but really am interested to watch this, so will flag it for later!

-Sera

Report comment

Sara

I believe I “get” what you are talking about when it comes to finding ways of creating a better environment for “inclusion” and greater participation of marginalized people etc. Some of your suggestions about “listening” and at times “stepping back” so others can come forward and speak etc, are especially important when you have new people, and others who might feel “out of place.”

But I am wondering if you are open to some criticism/feedback about some of your choices of language (at times) when you post “dictates” or “admonishments” to white people about what they can or cannot say, and/or do, in certain situations. And if someone were to disagree with some aspect of the “warning,” then the implication is that they must therefore most certainly be a “racist.”

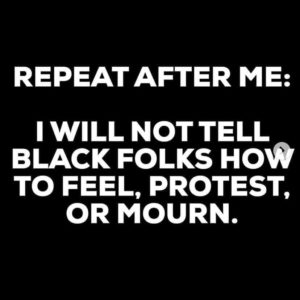

For example, in this blog you posted a big black box warning with the following admonishment:

“REPEAT AFTER ME: I WILL NOT TELL BLACK FOLKS HOW TO FEEL, PROTEST, OR MOURN.”

First off, I would not tell anyone how they should “feel” or “mourn.” Personal feelings are unique to the individual and generally flow from someone’s belief system and cultural influences. Mourning behavior and thoughts are also very much related to the the nature of a person’s “feelings.”

However, to say that people who are not minorities do not have the “right,” or even an “obligation,” to enter into a discussion and/or debate about the best ways to struggle (protest) against systemic racism, is just plain wrong.

As I mentioned in my above comment, there are many minority spokespeople (in this current uprising) from all sectors of society, representing many different class and racial viewpoints. Some of these people are acting (as I pointed out above) like “firemen” and “fire extinguishers” trying to stifle and limit the scope of the struggle within acceptable parameters for the “powers that be.” They must be challenged and struggled against.

We must ALL find ways to join with more radical elements within these minority movements and uprisings to oppose reformism and other dead end strategies. The fact that this is not easy to do correctly, and is filled with all kinds of potential minefields, should never preclude us from trying. History demands this of us.

And if the struggle against systemic racism does not ultimately link up with other struggles, such as ending climate destruction, women, psychiatric oppression, classism etc., we will never defeat the “powers that be” and their class based system of exploitation and oppression.

I believe you have made a few other bad choices of language (with several dictates and admonishments) in the past blog “A Racist Movement Cannot Move.” I do take issue with how you characterized that particular comment section as “too ugly and out of control.” Within that very long comment section there was some very respectable and legitimate feedback/criticism of some of your choices of language and particular admonishments to MIA readers and commenters.

Now that some time has past since that past struggle, do you see that there may be a similar problem connected to your black box warning (REPEAT AFTER ME…) in this current blog.

Again, you know I am a big supporter of your prolific writing here at MIA, and anyone writing several dozen blogs on any website is definitely increasing the odds that they might make a few mistakes here and there.

Respectfully, Richard

Report comment

Richard,

So, the meme that I posted is not my words. It is a meme circling the Internet, and that I have most explicitly seen posted by black people. They are not my words. I am supporting them.

While I think I get your point about – as a white person – not being beholden to ideas that may be coming from internalized oppression or are simply harmful… And while I *have* fallen into debates at times with – for example – black people who argue in favor of the existence of “reverse racism”… I nonetheless do not think we are going to come to a point of agreement on this. It is just too important right now that white people follow the lead of black people… That they make space for black leaders to fight out the best approaches… That space is made for people to move in a particular direction through their own process, and not be forced and pushed, even if someone is simply pushing them in what they think is the ‘right’ direction (and even if I would personally agree it is the ‘right’ direction).

I think white people *need* to have a place in the discussion, particularly when pushing back on other white people and using their privilege to push back on power in general. I think there is also space for us to ask questions that *could* support people to unpack and consider different ideas, or to share our own experiences at times. But systemic change has got to mean more black and brown leaders, not just more benevolent white people leading black and brown people in a different direction.

I know that’s not carrying all the nuance of what you are saying, but it’s how it boils down for me. I’m afraid we just won’t likely reach a point of agreement here.

As to the article you are referring to, I do not regret shutting that comments section down. Among the hundreds of comments remaining there, sure there’s some worthwhile stuff, and as we discussed earlier in this comments section, I have taken some commenter feedback to heart (e.g., not buying into the language of ‘loot’ and ‘riot’). However, that post was being flooded by horrible things, just like the Dear Man post was. Much of it has been moderated out, but it would not be fair to require me to have kept going with it and trying to keep up with the flood of awful, nor would it have been fair to others reading it.

Richard, I have now written over 70 pieces on Mad in America. Those are the *only* two pieces for which the comments section was shut down. I am generally fine with feedback or disagreement in comments sections of my articles. Even when I feel irritated by some of it, I do not request that it be erased, and as a moderator, Steve could tell you that – since Mad in America switched its approach to ‘moderate first’ – pretty much whenever he comes to me asking if I’m okay with a particular comment going through (if it’s on the line) I am typically in favor of letting it through and just responding to it. I am also one of the few authors on here who generally takes the time to response to each commenter on each piece at least once. That said, I also want to be clear that I – like all non-employee authors here – receive no compensation for my time spent writing pieces or responding to comments, and I have a limit to how much time I have given I also have a full-time job that consumes often 80 hours of my week, and two children. It would not be fair of people to expect me to be obligated to respond indefinitely to all comments on every article. The comments section for those two pieces went well beyond ‘okay,’ and I am glad they were closed. I’m not sure what to say beyond that.

-S

Report comment

Sera

Whether or not the meme (REPEAT AFTER ME…) you posted in your current blog were your specific words, is not the essential point I am making here. They were used in same manner, and used partially for the same purpose as some of your “dictates” and “admonishments” in prior blogs.

I’ll mention two prior such dictates:

“Stop Comparing Psychiatry to Slavery (or similar) and

“Stop Appropriating the words of Black People to Support System (or anti-system) Messages

While your intent here is to combat various forms of racism, and some of your particular examples you used (in the past blog) to highlight your intent were exactly that – crude forms of appropriation that do come off as racist, and just plain stupid.

However, your use of “absolutist” language in your “dictates” often totally lack CONTEXT AND POLITICAL PURPOSE by some of the radical activists using the language and analogies you decry and condemn.

For example, I applaud radical activists of ALL colors and nationalities who correctly use a famous quote by Frederich Douglas to expose the hypocrisy of U.S. patriotism and flag waving on July 4th in a country built on the backs of slavery, and the vicious exploitation of working class people (of all colors) here, and in many Third World countries. Once again, it’s all about “context” and “political purpose.” when evaluating someone’s particular use of a famous Black person’s words.

And some white political activists (anti-psychiatry and anti-capitalist) here in the MIA comment section, have correctly used the words of the Black revolutionary, Mumia Abu-Jamal (and other Black revolutionary leaders) to make important political points on numerous topics, including fighting psychiatric oppression.

And Sera, I have seen the video (and read the accounts) of a Black city official in Ferguson (in the rebellion related to Michael brown’s killing) tackle and assault a white revolutionary giving a revolutionary speech in the streets supporting the uprising. This same Black official (“fire extinguisher”) attempted to incite the police and other Black people against the “white outside agitators destroying our community.”

Bear in mind that this same white revolutionary is part of a larger group that also has Black members in the organization fighting for a socialist future in this country and around the world. That particular Black official needed to be condemned and called out for his attempts to suppress (and limit) multi-racial and multi-national unity fighting a common enemy. And yes, I am aware that there are some right wing elements acting as provocateurs in these situations. But this was definitely not the case, and this official knew that.

Sara YES, some more backward and ignorant white people need to be justly put on the defensive, and yes, they need to listen to, and follow the lead of Black people in some of these struggles.

However, there is far more nuance to be considered here when you print and repeat various absolutist “dictates” and “admonishments” to white radical political activists. It all boils down to CONTEXT AND POLITICAL PURPOSE when evaluating the role of white people in multi-racial political struggles.

Sera, I would never expect you or anyone else to defer to someone merely because of their age or political experience in political movements. But there are some people writing in this comment section with literally decades of radical activism, and some have been in the forefront with other Black radicals in some of the most significant struggles in this country’s history against systemic racial oppression. I’m in my fifth decade, and I know of others who equal that experience ,or come close.

So once again, Sera I ask you to reconsider the “absolutist” type language in some of your “dictates” and “admonishments” that have, at times, lacked NUANCE and CONTEXT, and result in potentially tarnishing very good radical activists with a tag of “racism.” And it can also have the effect of shutting down much needed debate and discussion.

Don’t get me wrong here, I am ALL FOR provocative political commentary and slogans, IF,they appropriately leave room for both political nuance and political context.

Richard

Report comment

Richard,

“Sera, I would never expect you or anyone else to defer to someone merely because of their age or political experience in political movements. But there are some people writing in this comment section with literally decades of radical activism, and some have been in the forefront with other Black radicals in some of the most significant struggles in this country’s history against systemic racial oppression. I’m in my fifth decade, and I know of others who equal that experience ,or come close.”

You basically just did. You’re just not going to convince me here. And while I think there are things to be learned from the elders in any movement, they do not hold all the truths.

“While your intent here is to combat various forms of racism, and some of your particular examples you used (in the past blog) to highlight your intent were exactly that – crude forms of appropriation that do come off as racist, and just plain stupid.”

Richard, Can we be done with this? You are still at me over an article from no less than *four* years ago. Although, in fairness to you, I would absolutely still stand by the idea that white people have no business using terms like “psychiatric slavery,” but I have *zero* interest or willingness in continue to volley that discussion back and forth.

Rather, in fairness to me, I will offer to you a hope that you might consider why you have spent so much time holding on to that four-year-old conversation. There are many aspects of what I know of you and your work that I have respect for, but I’m not obligated to respond to every comment at length nor work out these differences in perspective. At some point, you may just need to accept we see some of these pieces differently.

-Sera

Report comment

Sara

You completely misinterpreted my meaning in the following quote:

“While your intent here is to combat various forms of racism, and some of your particular examples you used (in the past blog) to highlight your intent were exactly that – crude forms of appropriation that do come off as racist, and just plain stupid.”

Here I was actually AGREEING with you that some of the particular examples you had used in that past blog were CORRECTLY pointing out examples of racism and political stupidity.

My essential point was (and still is) that in some of the OTHER situations, and examples I presented, there is a definite need to carefully examine the political context and political purpose of how white activists are using certain words and taking certain actions, before declaring them *out of bounds*, or possibly labeling them “racist.”

While I did mention the struggle over the “psychiatric slavery” analogy, I deliberately chose NOT to use that issue in my main example of where you failed to take into consideration “context” and “political purpose” when examining how white activists can correctly use significant quotes from past Black activists.

I don’t know if your misinterpretation of my above quote has now created a level of emotion, and a resulting atmosphere where dialogue can no longer continue.

I do believe that my Frederich Douglas example (in the above comment) was both important, and helpful, feedback about when “absolutist” language and certain types of “dictates” to white activists (that ignores certain contextual information), will NOT help us in our fight against racist thinking and behavior.

Sara, I am not sure WHAT you overall think my motivation is in raising some of these criticisms of a very FEW aspects of your many writings here at MIA.

Even as an older and very seasoned revolutionary activist, it is not easy (and frankly,very uncomfortable at times) raising these issues with you. I take no pleasure in pursuing these types of discussions. I do it because I feel some sort of moral and historical responsibility to seek the truth and a path to human liberation from oppression.

In past MIA dialogues over your blogs, other critics of your writing, either dismiss you outright, or just argue with you about how you are wrong. Very few people, if ever, actually try to offer you constructive feedback by carefully analyzing where you are right and suggesting where your logic and/or political pronouncements may have drifted off course.

I make the effort (and tolerate the discomfort) with you, precisely because I see you as a gifted and very consequential writer on the internet, around the issue of psychiatric oppression and other important political struggles. I am not sorry I made these efforts to dialogue with you and attempt to give you constructive feedback, but I am saddened and disappointed that this discussion may end on such a negative vibe.

Richard

Report comment

Okay, Richard. I hear you on my misunderstanding. I gotta be honest, it is *really* hard to have lengthy dialogues in this manner. I work *a lot* of hours, and even more hours right now during this ‘COVID’ mess. I feel a responsibility and obligation to respond to each commenter at least once whether they right something supportive or in disagreement, but you and oldhead in particular write very lengthy posts with a lot of complex ideas in them, and usually not just one of them per article. I am trying to keep up here, but the reality is that I am reading very quickly a lot of the time in an effort to keep up with my obligation to things I write and not just be so arrogant as to write and run… but it is really, really hard to pull the full meaning from every long post I receive when so pressed from time and pulled in multiple directions. If I listed out all the things that have been going on in the last 24 hours in my work world (never mind my kid world) while also trying to answer comments here… well, it would be a long list.

I’m not sure it’s helpful – or at least I’m not sure I’m *capable* logistically speaking of continuing to go back and forth here, but if you want to e-mail me to talk about things further, I am willing to do that.

-Sera

Report comment

To Richard D. Lewis & Sera:

Richard D. Lewis said:

“I see you as a gifted and very consequential writer on the internet, around the issue of psychiatric oppression and other important political struggles.”

I COMPLETELY AGREE! We do appreciate you, Sera!

Without the forum pages (I do remember the viral attack), it is impossible for those of us to write under pseudonyms and effectively carry on threads of important conversations–much less follow each other’s links or organize.

Cite hopping with references in reel time.

And MIA MUST survive so the general public can have access to the compendium of articles on toxic psychiatry.

I just want to say it again. We do appreciate you!

Report comment

Sara

Fair enough for now. Carry on!

Richard

Report comment

(Since I may have some people bristling in this thread anyway I might as well make it a perfect storm.)

I wasn’t going to bring this up again, but since Richard did I will back him up, even though we have some serious disagreements about other things, because I know he must still harbor some remaining anger. I’m sorry that you haven’t yet realized that the “Racist Movement” blog was a colossal mistake, replete with some liberal racism of your own, and was very insulting to some longtime “ugly” commenters, including Richard, whom you basically dismissed as an old racist white guy who doesn’t get it. It was pretty ageist. I don’t understand why, as a fairly well off white woman you presume to lecture others about their “privilege,” as you seem to see the concept of privilege not as a way of understaanding social inequities but as a a battering ram to demonstrate your own “wokeness.” You do not understand the feelings and perceptions of Black people (other than perhaps those in your immediate circle) well enough to be putting yourself in this role. By your own logic such columns should be written by politically aware Black people (and I don’t mean people with Black faces who somehow have been introduced to the MIA milieu).

I encourage Richard to re-post the final comment he tried to slip under the wire before you closed that comments section, which you refused to accept. I still have a copy if Richard doesn’t, if he doesn’t mind me posting it. It would maybe help shed light on some of the confusion and damaged feelings that resulted from that article. (In fact if the article is still to be archived on MIA it might be a good idea to re-publish it and examine it paragraph by paragraph.) It’s important for white people to understand racism, both what it is and what it isn’t.

Anyway it would have been dishonest to not say this. I would encourage you to consider removing the “Racist Movement” blog from MIA, rather than it be a source of continuing tension. Not the sort of tension which results from hearing uncomfortable truths, but that which results from being talked down to.

Otherwise I’ll repeat the usual: a) what is the “system” you refer to which drives “systemic” racism; and b) how can you not include capitalism as being inextricably intertwined with racism?

Report comment

Oh, oldhead. I want you to know that I keep being asked if your and a few other people’s comments should be moderated out. I have said no, but my energy is really waning for this.

Several things:

1. Your comment led me to go back and read ‘A Racist Movement’ again. There is a lot of good stuff in there. I do not regret it. There *was* a piece I did regret. A reference to Tourettes Syndrome that was less than respectful. A moderator helped me remove it once I realized our error, so it is no longer there. There is also another racism article that I *do* regret for its appropriative nature. It is this one: https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/01/cant-breathe/ I am embarrassed that I used “Can’t Breathe’ for anything, and centered so much of my own story. If I could take *anything* down, it would be that one. However, Mad in America has a policy against removing past articles, and so I’ve never asked. Additionally, living with the embarrassment of my own mistakes is okay. Necessary in some ways. I recently decided that I would go through some of my old pieces on racism and offer some corrections and apology for the things I see as wrong in them now. I do not see doing that on ‘A Racist Movement Cannot Move,’ for several reasons including that I co-wrote it with two black people.

2. I am wondering about your definition of ‘reasonably well off.’ Certainly, I was born into some wealth as a kid. And I’ve benefited from that somewhat as an adult to when I had parents to fall back on to help me – say when I got very unexpectedly pregnant in my 20s. I was lucky and have privilege in that regard, and I mention that every single time I share my story publicly. However, I haven’t had access to any “family” money in a very long time. I am severely in debt, and go further in debt every single month because my single-income household does not have enough to cover basic expenses. I’m hardly living in poverty, but we will struggle to figure out how to pay for the least inexpensive Community College for my son when he leaves highschool next year. I guess I do not define that as “reasonably well off,” but it is better than many people who don’t have enough to cover their basic expenses and also don’t have access to the credit that I have to survive for a while longer, so interpret it how you will, I guess. This is irrelevant to most things here, but it’s hard – when I am struggling so much with money – to read such assumptions.

3. I cycled through the comments on the other article (Racist Movement). I keep thinking it is funny that people say the comments section hadn’t gotten out of control, when they have no idea how many comments were being moderated out (i.e., that are no longer visible now), or how much labor it was requiring on my part and moderators’ parts to try and keep up.

4. In flipping through old comments, I looked for where you are getting this idea that I called Richard a “racist old white man.” It doesn’t sound like something I say, and I didn’t remember saying it. And, as best as I can tell, I didn’t say it. I did, however, find a comment where I referred to the “mostly older white men” group that was responding to my comments. What I guess I was trying to get at is that I find that you, Richard, and some others do have what I receive as a very – at times – condescending way of speaking to me, replete with periodic references to how much longer you all have been at this and how much more you all know than me. It may not be intentional, and you/others may find me equally condescending. Fine, but it does get tiresome. The comments are so long, and I’ve actually been chastised at times for not writing a long enough comment representative of enough of what was said back. As if this is my job, and I’m being paid to do it. As if I owe endless amounts of my emotional labor. All this even in spite of the fact that I’m one of the few authors who actually takes the time to consistently respond at all. So, when I said that, that is what I had in mind. But I could have phrased it better, and without using the word “older,” so I am sorry for that. Regardless of my intent or what I was trying to say, I can understand why it landed as ageist, and I could have done better.

5. a) I’m pretty sure I’ve said at various points that when it comes to systemic racism I am talking about *all* the systems.

6. b) I *have* said that capitalism and economic justice are inextricably intertwined with racism. Multiple times in multiple places. Just because I don’t want to don the labels that you deem most appropriate for me to don in order to pledge my allegiance to your philosophy (aka “anti-capitalism,” and “anti-psychiatry”) doesn’t mean I have not acknowledged this point. I have.

oldhead, I do not see a point in continuing to go back and forth here. Maybe you still have an axe to grind with me, but for my part, I am doing my best to create change. Sometimes that looks like words on a page. Other times it looks like direct action. And still other times it looks like a zillion other things. And, I am really, really tired. I do not feel any differently about what I wrote here than when I started, so if that was your goal, you haven’t been successful. I just feel more tired. It’d be nice if you’d direct your energies elsewhere for a while. I hope you can find something else to do with your time here. I don’t know that I’m giong to keep responding.

-Sera

Report comment

Sara, Oldhead, and ALL

To break INTO the tension here, I just want to say that I LOVE both Sara Davidow and Oldhead!

That form of LOVE is often referred to within political movements fighting oppression, with the affectionate name or greeting of “COMRADE.”

Wikipedia says: ” ,,,Political use of the term was inspired by the French Revolution, after which it grew into a form of address between socialists and workers…

When the socialist movement gained momentum in the mid-19th century, socialists elsewhere began to look for a similar egalitarian alternative to terms like “Mister”, “Miss”, or “Missus”. In German, the word Kamerad had long been used as an affectionate form of address among people linked by some strong common interest, such as a sport, a college, a profession (notably as a soldier), or simply friendship.[5] The term was often used with political overtones in the revolutions of 1848…’

I have spent precious time wrangling (criticism/self-criticism) with both of these “comrades” because they are brilliant writers and such deeply passionate fighters against human oppression.

I have learned from them both, AND ,at times, taken the risk (cause it sure ain’t easy) to struggled with them to help make them be BETTER at what they already do WELL.

Damned it, don’t we ALL have to get better at fighting this incredibly powerful system of capitalism/imperialism that simply has such infinite ways to crush the human spirit.

Oldhead, I would NEVER EVER want the past blog “A Racist Movement Cannot Move” to be removed from the archive. Everyone here should most definitely read and reflect on that blog and comment section, because it is so deeply rich with political lessons.

To quote Oldhead from above:

“It’s important for white people to understand racism, both what it is and what it isn’t.”

Reading that particular blog and comment section (and this one) provides many deep lessons that can help us in future battles against systemic racism.

Now back to the work at hand: trying to find ways to build off of the tremendous opportunities provided all radical activists by the powerful uprising in America and around the world over the brutal murder of George Floyd.

Our ENEMY has been weakened and exposed in these tumultuous times. We must seek to advance AND link all these struggles against systemic racism, psychiatric oppression, climate destruction, sexism. classism etc.

Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win!.

Comradely, Richard

Report comment

Thank you, Richard! LOVELY post!

Report comment

Nope, no grudge Sera. You know I give you props sometimes as well as criticism (which is not of you but what you write, which is the point of discourse).

And no I don’t expect you to change in the immediate future, just adding to the perspectives of meremortal, anomie, Richard & others.

Report comment

Oldhead, I would NEVER EVER want the past blog “A Racist Movement Cannot Move” to be removed from the archive. Everyone here should most definitely read and reflect on that blog and comment section, because it is so deeply rich with political lessons.

My other suggestion was to republish it and examine it paragraph by paragraph, like we’re in a giant classroom.

Report comment

Richard, I’m too tired to say much more than “thank you” for your last post, so… thank you. Our enemies have been exposed, indeed. Onward in the fight. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I’m grateful for Sera’s blog and Richard’s replies.

Report comment

Thanks, Berta! Glad to see you here. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

YES! I am very thankful for Richard’s points, as well. So well put, Richard!

Report comment

Sera,

Here’s hopes for a spirited and reasonably intelligent discussion, I guess you knew what you were getting into.

I don’t yet have a comment specific to this article, but would like to pick up where we left off in your “Roseanne” article regarding what “systemic racism” is and isn’t. And, when we are talking about systemic racism, how to identify exactly what that system is (hint: it is almost invariably capitalism).

As for “what’s happening out there,” for many at MIA it’s not really “out there” at all. I’m not going to get overly personal or specific regarding the whole “Floyd protest” scene; suffice it to say I see many agendas, some of them competing, some of them illusory, some of them opportunistic. Maybe even a couple that might be hopeful and worth looking at. I salute BLM at least so far for not allowing its name & slogan to be expropriated.

But back to systemic racism. Then I have a proposal.

Here’s what longtime MIA reader/poster meremortal had to say about systemic racism following the Roseanne article. I hope she won’t mind me resurrecting it as I think it’s pretty eloquent:

Liberals constantly make the mistake of thinking that racism is about the personal attitudes & likes/dislikes of individuals. Those things are part of the landscape of living in a profoundly racist society, but they aren’t what systemic and institutional racism is.

Those with political views further to the left have identified this misplaced focus on changing individuals’ personal views and attitudes. We call it “idealism.” Larger structures than individuals create, shape, and reinforce racist attitudes in individuals as they go about their primary objective: to build and maintain a system that extracts material resources from some (POC) and directs them to others (whites).

Trying to change this root problem, which is material, by going nuts over the attitudes and random twatter that comes out of individuals’ mouths is simply an exercise in futility…a lesson white liberals desperately need to learn right now is that not everyone with great intentions and deeply-held values about equality and anti-racism shares their political views. There is diversity and complexity here, among people who are all staunchly anti-racist.

I would like to segue here. (Btw I think everything I’m posting here is relevant to a George Floyd/systemic racism/systemic psychiatry discussion, and should not be seen as a diversion in any sense.)

A group of survivors (including a number of MIA’s “usual suspects”), has just completed a set of anti-psychiatry principles, which we are starting to promulgate here & elsewhere. At least three are relevant to this discussion, which include one of our demands:

— Psychiatry is not a legitimate field of medicine.

— Psychiatry is a tool of social control which enforces conformity to the prevailing social order;

One of out two immediate demands/goals is:

We demand an end to all state support for psychiatry, including but not limited to the use of psychiatric testimony in legal proceedings; psychiatric screenings in schools, prisons, and workplaces; licensing; and the use of public monies to support psychiatric programs or research.

In others words — as it just dawned on me recently — DEFUND PSYCHIATRY!

We hear so-called “community activists” yelling about taking $ from the police and giving it to “mental health.” However if you accept our evidence-based analysis, psychiatry/”mental health” IS the police in a more convoluted form. To be consistent those of us who believe we should be “defunding the police” should as a matter of course include psychiatry as part of this “defunding,” whatever form it ends up taking.

Do I hear support for this? Why or why not?

Report comment

Oldhead,

My time is really limited at the moment, but what I will say is this: Yes, absolutely systemic racism and capitalism/the need for economic justice are deeply intertwined, and have been since the beginning. And I would fully support the ‘defund psychiatry’ initiative, and it is not the first time I have heard that phrase over the last few months. Psychiatry has been used as a tool of oppression with many forms of systemic oppression, and certainly racism.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

And as been noted since the 1984 Toronto Principles and actually as far back as 1976, psychiatry constitutes a “parallel police force.”

The only difference is — read my words carefully here — there is an actual need being addressed by the existence of police, however poorly it is being done — i.e. the need to physically protect the people from criminal aggression. In the case of psychiatry, the goal is to mold and “adjust” the citizenry to the needs of the system, or the prevailing culture, not to protect them from anything.

Report comment

Me love it.

Report comment

Well. I think many would say that psychiatry is also addressing a need to physically protect people from aggression, some of it criminal. And I would at least argue that *both* have roots in the effort “to mold and “adjust” the citizenry to the needs of the system, or the prevailing culture.”

Report comment

Protecting people from criminality is not the purpose or function of psychiatry, I don’t know what you mean. (It may happen occasionally, more in spite of than because of anything specific to psychiatry; maybe you could be more specific yourself.)

I think I remember that Murphy used to keep a photo of Sandy Hook victims on his desk to inspire him as he pushed the infamous Murphy Bill. Its purpose was to “protect” people from us, and this is the mentalist root concern of most “mental health” legislation.

Both police forces and psychiatry are extensions of slavery: Police forces originated for the purpose of rounding up escaped slaves, and this function was augmented by psychiatry with its “diagnoses” of drapetomania (to be cured by severe beatings).

So yes, BOTH police and psychiatry are charged with pounding round pegs into square holes. Practically speaking, for many of us psychiatry IS the police, which needs to be taken into account in these “defunding” discussions.

Report comment

Well said.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/fifth-estate-d-andre-campbell-police-shooting-family-1.5602503

https://www.halifaxtoday.ca/national-news/nb-police-shooting-of-indigenous-woman-leads-to-questions-on-wellness-checks-2413104

https://torontosun.com/news/local-news/siu-probing-death-of-woman-from-toronto-balcony

Hi Sera.

The above articles from Canada, just recently.

I don’t live in the US. I however have seen the racism since I live in one of the few cities that has a high first nations community. We have the largest, per capita cop presence. Often our crime rate is up there.

I myself have experienced snotty cops, who like to egg people on.

I have seen them “egg” people on.

But for some reason, they only pick on women and the meek/poor.

So since Floyd died, Canadians became opportunists. Not as if we didn’t have this crap before.

But, it was on video. Makes so much difference and I don’t understand, why only videos matter to people. I was actually turned off by all the lighter skinned colonialists walking around with their signs. Especially when it called for “defunding police” and “funding “mental health”. Opportunists.

Using some poor guy who died in front of millions, for their own purpose.

Psychiatry AND police are salivating how the do gooders are making every cop crime and every incident a “mental health” issue.

There IS systemic racism. Yet I cannot look at that in isolation. Black and indigenous have never been seen as real people, but neither have the poor, the vulnerable.

I was so happy that everyone went out and meant it. I felt if they were heard, so would indigenous and possibly the incarcerated in psych, and the children who are drugged.

I felt if we ALL banded together, not out of some flaky sentiments, because it seems to be the IN thing…but if only all the affected banded together for discrimination and oppression.

I overheard a guy being supportive about the protests and relaying his sentiments to a black guy. The black guy was clearly not impressed and said “ALL lives matter”.

He understood, that the real systemic issues are about discrimination and oppression which he has most likely happen to his “white” buddies.

I was thrilled when they stood up for Floyd. Because racism is real. It never left. The only thing that changed was we are supposed to say politically correct things.

I am probably the only one that thinks peaceful protests don’t work. At least not the begging kind.

I realize I was not supposed to drag other issues into colour discrimination. It makes me look as if I don’t understand. I DO understand. And yet I’m not black or black and poor, so how could I ever truly understand, right? I don’t know.

I think I understood all of the people on here. I don’t know their colour, only the ones with pictures up. I won’t know in totality their pain.

Report comment

“Protests” are in at least in one sense demonstrations of powerlessness since you are “protesting” to whomever is in charge, rather than being in charge yourself.

All violent expressions at this point pretty much play into the hands of the system, since violence is what they’re best at, it’s their turf.. If people think they defeated the police they should get some better weed; in many cities the cops totally stood down. (Not that this isn’t a fairly significant development in itself.) However, as usual, too many people, some with unsolicited assistance, are still targeting their own communities and ignoring that, without a pre- organized democratic revolutionary government to replace it with, if the system falls it will fall on us.

Report comment

Sam,

I am not 100% sure I followed all the ins and outs of your comment, but to be clear, I am for sure not saying that racism is our only problem, or the only form of systemic oppression. Nor do I support those who are calling for social workers to replace police, as social workers/the mental health system are – as others have pointed out – is just another form of policing in so many instances and is quick to call in the actual police, too. I regard many of the people saying such things as well-intended, and harmfully ignorant. It is far too common that those who get topics like systemic racism simply have no clue about psychiatric oppression, and think the best answer is to incarcerate people in psychiatric facilities (aka “give them access to treatment”).

I have heard non-white people say “All lives matter.” It’s not my job or place to figure out why, though I will say that the majority of times I’ve heard that it’s been to largely white groups, and it’s hard not to wonder how some non-white people have been trained, and pushed, and punished into finding ways to signal that they are not a threat, and support white people. But, while I *have* heard *some* black and brown people utter that phrase, I have heard *far more* black and brown people be hurt by it. For so many reasons. Including that it represents an absolutely fundamental misunderstanding of what it means.

Here is a brief segment of what I wrote in a comment on Mad in America’s Facebook page post for this article. (Side note: One commenter noted that the comments section was like a “dumpster fire,” and I would not disagree.)

In reality, Black Lives Matter is not the same as saying ONLY Black Lives Matter. Rather, it is a way of saying:

* We must focus on those lives being treated as invisible or disposable *in order for* all lives to actually matter.

* We must focus on those being routinely harmed in order to lift them up…. no, not above us, but no longer below.

* We must recognize that – until we are able to find a place of equality, equity, and inclusion – it is essential that we keep naming that Black Lives Matter because that is not the message being sent or received at this time.

In any case, there’s much more I could be responding to or better understanding here I suspect, but I’ll leave it at this for now.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

It is far too common that those who get topics like systemic racism simply have no clue about psychiatric oppression, and think the best answer is to incarcerate people in psychiatric facilities.

It’s more than far too common, it’s the norm. Even more disgusting, yet necessary to recognize, is that most of these people consider themselves “leftists” (though I don’t). In the late 70’s local leftist groups in San Francisco, L.A., New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other cities supported us and endorsed our demonstrations. Getting them to do that today is going to take an enormous amount of struggle since currently (always with exceptions) young people, while highly motivated to do the right thing, are politically clueless and in the grip of a “woke” mentality which is mistaken for consciousness and strategy.

It is also necessary to recognize that capitalism and racism exist in tandem, and to demand the end of racism without taking simultaneous measures to defeat capitalism is pretty much a way for white people to wash their hands of the situation and say “oh well, we tried.” As meremortal described in her quote above, defeating systemic racism is not primarily a matter of “feelings,” but of dismantling the material structures which allow white supremacist thought and practice to flourish.

Report comment

On the CBS news tonight it was reveled the police officer Derek Chauvin knew George Floyd , so that changes the murder from blind racism to something else. IMO obviously all officers should pass some kind of psychology test to indicate that they are not racist. That this test does not exist, or that the existing test let police officer Derek Chauvin become an officer is wrong.

Report comment

markps2,

I am not sure it changes too much, though I’ve also heard they worked for the same business over the course of several years. I do not know that means it is any less an issue of racism and white supremacy… not only what Derek did, but the complicity of the other cops, and so on.

I worry about your recommendation for a psychology test for a number of reasons including:

1. We have all been socialized in a white supremacist culture. All of us. That means that pretty much all white people will sometimes do or say things rooted in systemic racism. That doesn’t necessarily mean we are doomed. But it does mean that we need to *all* stop with the defensiveness, and intentionally pay attention to that so that we can recognize it when it happens in ourselves and others around us and attempt to mitigate it, correct it, and apologize to those we’ve harmed along the way. (Etc.)

2. Even “good cops” are embedded in a criminal (in)justice system that is fundamentally rooted in that white supremacist culture. Weeding out those cops (or prospective cops) who are invested in actively *maintaining* that seems valuable, but ignoring that the system will generally force even the “good cops” to become complicit in awful things is necessary to make real change.

3. I am not interested in giving any more power or trust to the mental health system. Do we really believe that they’d be any more capable of psychologically evaluating for beliefs rooted in racism than much of anything else? Do we want to give them that power?

Although I’m in disagreement with your proposal, I nonetheless appreciate your posting your thoughts here.

Thank you,

Sera

Report comment

And who would devise and administer the “psychology test”?

Report comment

UPDATE CBS News has retracted their story that they knew each other. IF they had known each other and had grievances between them, those grievances could have been a factor for motivation. I’m sorry I trusted CBS news.

Who judges who? I don’t know. In the past it was whoever had the best gun and army to enforce the King/Queens law. http://www.laborarts.org/collections/item.cfm?itemid=428

If precious metals are no longer precious metals, as in, they have no value or power , then the pyramid has no top, no way to pay or motivate those under them.

Report comment

It could also be that

(1) White people’s ‘mental health’–as judged by the psychiatric paradigm–is poorer than black people’s in general. In 2014, Whites’ suicide rate was three times that of Blacks and white Americans are twice as likely to take psychiatric drugs as other races.

(2) because MiA is not abolitionist, it might be disproportionately alienating to black survivors. Black people are overrepresented in inpatient settings compared to white people, and studies show that they are more fearful of psychiatry, and less likely than white people to comply with outpatient referrals after hospitalization.

In other words, black people who encounter psychiatry get the hell away from it as soon as they are able, and try to avoid it, which demonstrates that they see little to no value there. White people, on the other hand, are more likely to take on the illness label as an identity, continue on with drugs and therapy, and in general continue to demonstrate that they see something worth “reforming” in psychiatry at higher rates than black people do.

Report comment

(2) because MiA is not abolitionist, it might be disproportionately alienating to black survivors.

Wow. You’re going against the official line here meremortal — good to see you showing up!

Report comment

Posting as moderator: I do want to point out here that MIA is not taking any specific point of view regarding reform vs. abolition. MIA was created as an alternative news source to put out any and all information that questions the validity of the current paradigm of care. It is not intended to take a political position on an antipsychiatry vs. critical psychiatry viewpoint. It is intended to encourage discussion of a range of viewpoints that are not normally made visible, and to allow voices that are normally silenced to be heard. As such, MIA is not taking any particular viewpoint supporting or opposing the abolition of psychiatry. That is up to the readers to determine for themselves.

Report comment

This is not true Steve. RW has taken explicit positions against anti-psychiatry. His position is essentially that since “people” see the notion of anti-psychiatry as unscientific and conflate it with Scientology we should reject it. (If I had permission to quote his personal emails to me I could document this.) A review of RW’s public MIA comments on the topic would likely also bear this out.

Report comment

This is NOT me as moderator. I will let Bob answer for himself on this, but my view is that this is a misperception of what he has said. For sure, he wants to be seen as scientific and objective, and I think the pursuit of disseminating information and letting people draw their own conclusions from it is the most effective way to make that happen. And I certainly see that his work AND MIA has had a huge impact on causing people to question the dominant paradigm, more than any other person I can think of. I think his impact speaks for itself and I have certainly not accomplished 1/100th of what he has, so whatever approach he is taking, my hat is off to him.

Report comment

I have a right to not be misrepresented. If I had the freedom to quote official MIA communications sent to me by RW (which he might not mind at all for all I know) I could dispel any confusion, instead of being cast as throwing around baseless accusations.

Report comment

And once again this is being portrayed as me casting aspersions on RW when I am simply repeating his own words. It’s not the first time, and it pisses me off. It feels tantamount to being accused of lying.

Report comment

I’m not saying at all that he didn’t say that, just that I am not sure it means what you think it means. I don’t think you are casting aspersions, either. I just see the logic in the decisions he’s made, and the effect it has had.

I did check the mission statement, and it is a “reimagining” statement. So it may be you are right. But I’ll leave it to Bob to say.

Report comment

Oldhead

When you said about RW:

“His position is essentially that since “people” see the notion of anti-psychiatry as unscientific and conflate it with Scientology we should reject it.”

By itself, this description of RW’s views does not exactly imply that he is against the concept and meaning of “anti-psychiatry.” It only means that he possibly believes that to be public about such a position at this time in history, especially for a journalist, would undercut his role (and that of MIA) in the struggle against psychiatric oppression and the entire Medical Model.

I applaud the spectacular forum RW has created at MIA for us all to learn, debate, discuss, and organize against psychiatric oppression.

Oldhead, it is up to US to do a better job in the coming years of exposing and attacking psychiatry for its oppressive and criminal role in the world today.

We must create favorable conditions in our anti-psychiatry political work to make it possible for many people, including RW, to grasp the necessity and importance of taking a clear and public stand for the abolition of psychiatry.

Of course, Oldhead you know that I believe the destiny of psychiatry is intimately connected and dependent upon the future of the entire capitalist system. So we need to do a better job in our anti-capitalist work, as well, in making these links to social control and all other forms of psychiatric oppression.

Richard

Report comment

Hey Steve!

I am hoping this will be my last series of posts on here for a short time. Going to take a rest for a month before I move sideways or back into the TI community–my handlers are doing a lot of damage with psychiatry disinfo. in that community.

And then, it’s back onto here. I have some specific topics I want to cover. But, firstly, I need a break (and I won’t make it five years this time, PROMISE!)

From my last post on another page about the Targeted Individual Program. (or technological trafficking, as Rai Jo correctly pointed out)

“When I am not being poisoned, gang-stalked, hit with DEW’s (they think so little of my intellect, yet they are trying to form a brain tumor with the neuro-weapons), harassed, insulted, shocked, (all my friends, but one, and my biological family have turned against me using the “mental illness” smear), (my neighbors do psyops on me, have listening devices pointed at my house, follow me in the neighborhood, have trained their dogs to attack me), and when I am not being run off the road……

On the next post, I will post my hard evidence on here. The listening devices pointed DIRECTLY AT THE WINDOWS OF MY HOUSE, and other abuses.”

As Promised, I will post the pictures I have below. I’m not sure if the link is going to work, but if NOT, I will find another way…

*The tech listening devices are state-of-the-art listening devices circa 1988 (or sooner), meaning they are *not* state of the art. They have gone down in price to about $300 so that my neighbors can afford it—they have three (at least). What you can’t see in the picture, but what I could see with the naked eye, was the attached cylinder to the end of the beam…it would have made for better evidence, but I am new at collecting evidence.

(when you speak in your house, the sound vibrations hit the window & are decoded on the other side of the window by the laser, sound vibrations into audible & understandable language translated on the other side, don’t ask me to explain the physics of it)

I believe there may be (possibly) three other neighbors doing this to my house…I am not sure.

*The directed energy weapon post isn’t a good picture, and my neighbors are more careful that I do not get better pictures now that I have hard evidence. They leased a screen sized one off of the dark web, aided by one of my handlers (who posts on MIA, btw, all four of my handlers post on MIA!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!)

I will just let that sink in for a minute…

I cannot even imagine what damage a screen-sized weapon is doing to me & my husband. It is not up right now, but my neighbors are going to make me pay for THIS post.

YOU CAN BE SURE OF THAT!!!!

*The picture of the EMF, microwave damage, is hard evidence proof that a TI staying with me got from an app. on his smart phone.

He was being hit so hard in the chest, he couldn’t walk & laid on the floor for hours, this went on for days & days & days. He tested it on me & I WAS RECEIVING EVEN MORE EMF DAMAGE than he was!!!

I have to meditate for 2 hours a day to block it & manage the pain.

*And finally, the message “Sold AT” on the license plate pulled up in the OTHER neighbor’s driveway means I have been “Sold” to another handler in cyberspace. As a technologically trafficked victim.

This is a trafficking program…if you remember the articles on psychiatric drugs embedded with sensor chips, well then you can imagine the amount of money tech companies make off of selling us to tech companies, military subcontractors, Big Pharma, medical guilds & hospitals, organ harvesting & human trafficking criminal cartels.

It is a trafficking program. And the money these criminals make off of us in the multi-multi-billions of dollars, if not more. Not just for psychiatry, but also cancer “research,” autism “research,” Alzheimer’s “research.”

Not to develop cures, but to make new drugs for Big Pharma.

O.K., I can’t get it to load. I will try again, offline, first.

Meanwhile:

And once you are a targeted, or technologically trafficked individual. This short & Excellent 5 minute video will explain how we are tracked, gang-stalked, harassed & subject to Street Theater (an East German Stasi technique)

within the existing AI/tech infrastructure:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2x_-XpCHM8M

(many on this site may be included in this technologically trafficked program, in fact, I would be surprised if it were otherwise. I am now looking for shorter videos since it is very difficult to connect with my fellow AP survivor/activists)

Report comment

This is unnecessary Richard. Whether I agree with RW or not isn’t the issue, nor is how many good things he has done, so I won’t be repeatedly diverted or cornered into being defensive. I’m disappointed to see you playing into this emotionalism. No one is attacking RW so he needs no defense.

RW’s inner calculations and personal strategies are not my concern or my business. I mentioned the MIA “line” in passing, in response to a previous point made by meremortal, a reference which Steve inaccurately “corrected,” and that’s what I was responding to, and how this all started. RW personally had nothing to do with it.

Since you force the issue, a) regardless of its strategic underpinnings the editorial line of MIA IS objectively reformist, as reflected by the slogan “A Community for Remaking Mental Heallth.” (“Remaking” is basically synonymous with “reforming.”); and b) regardless of the real or purported strategic rationale which may underlie it, the MIA editorial line DOES reject Anti-psychiatry based upon the reasoning that being openly AP is outmoded, inconvenient or whatever.

I’m not criticizing or objecting to MIA’S/RW’s positions. I’m simply establishing what they are, so that we can have a discussion based on mutually agreed upon definitions.

I hope no one is trying to drag RW into this personally, as none of this weird back & forth is based on anything new he has said or done, but on people’s projections and assumptions.

Report comment

Anyway I’m sorry I even brought this up, as I don’t consider MIA’s editorial standards a direct or immediate concern of survivors, or advocate trying to dictate what they should be. I doubt that I ever have. I’m here to educate, analyze, strategize, and sometimes organize.

Report comment

Oldhead

Perhaps you are correct to point out the “reformist line” within the MIA mission statement.

It is fair to say that most people who post blogs and comments at MIA do ultimately slip into some sort of “reformism” most of the time.

This occurs, both when they discuss what’s wrong with psychiatry and their Medical Model and then they propose *alternatives,* AND when they discuss making changes to the system of capitalism which both advances and sustains psychiatry and the Medical Model.

I am extremely gratified that MIA leaves so much space for anti-psychiatry perspectives.

All of this just makes it even clearer how much work we (those who are abolitionists and anti-capitalists) must do to move humanity closer to the point where both psychiatry and capitalism will only be featured in museums and history books.

Historically, most people in any given societal upheaval will cling on to reformist tendencies right up to the last minute prior to when a revolutionary transformation occurs.

Richard

Report comment